Abstract

Objective assessment of balance during childhood is essential for supporting motor development, preventing falls, and identifying potential impairments. Traditional clinical tests, such as the Flamingo and balance beam, are widely used but remain limited by subjectivity and lack of precision. Accelerometry offers quantitative measures, and its integration with machine learning models provides an opportunity to explore predictive assessment in pediatric populations. This study evaluated the feasibility of predicting clinical balance test outcomes in schoolchildren using accelerometric data from both static and dynamic tasks. A cross-sectional study was conducted with 90 children aged 6 to 12 years. Accelerometric signals were recorded in three axes and magnitude during static tasks (eyes closed, eyes open, and unstable surface) and during gait. Outcomes included the number of supports in the Flamingo test and the distance covered in the balance beam test. Several machine learning models, including linear regression, penalized regression, k-nearest neighbors, support vector regression, and random forest, were applied using 5-fold cross-validation. Models showed modest but consistent predictive accuracy for the Flamingo test, particularly with static tasks, with random forest, support vector regression, and k-nearest neighbors performing best. Prediction of balance beam outcomes was poor across all models. These findings suggest that accelerometry-based machine learning is feasible for predicting balance performance in children, especially for the Flamingo test, supporting its potential as a digital tool for screening and educational health applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Postural balance in childhood is pivotal for proper motor development and the early identification of neurological or musculoskeletal impairments1,2. Impaired balance in schoolchildren has been linked to a higher risk of falls and injury, a leading cause of non-fatal harm in pediatric populations, and carries broader public-health implications through reduced physical activity and excess weight. This is supported by pediatric studies showing (i) the prominence of fall injuries and their circumstances in children, (ii) associations between poorer balance and injury risk in youth, (iii) the widespread use and reliability of field balance tests in school-aged cohorts, and (iv) the well-established ties between low activity and childhood obesity3,4,5,6,7 . Despite their widespread use in physical education and clinical screenings, traditional field balance tests such as the Flamingo single-leg stance and the balance beam test are inherently subjective, rely on visual observation, and often exhibit limited sensitivity to subtle postural control deficits8,9.

Traditional clinical field tests such as the Flamingo single-leg stance and the balance beam test remain popular in physical education settings and clinical screenings due to their simplicity, low cost, and ease of administration8,10. However, evidence of their reliability and validity in children is mixed. For instance, the Flamingo test has yielded inconsistent test–retest reliability, while the balance beam walking test demonstrates higher reproducibility as a dynamic balance measure8. Meta-analyses of pediatric balance assessment tools also highlight significant limitations in measurement consistency and sensitivity to subtle impairments10. Furthermore, several studies report only moderate correlations between Flamingo and beam tests, suggesting that each assesses distinct aspects of balance rather than a unified construct8. This raises concerns about relying on a single test to detect early or mild deficits in postural control among school-age children8,10.

Despite their potential, accelerometers are still underutilized in routine pediatric assessments of postural control. A recent systematic review found that accelerometry has a limited degree of implementation as a tool for evaluating postural control in children, primarily used in studies of static balance and gait, and highlights the need for standardized assessment protocols11. Experimental research demonstrates that trunk-mounted accelerometers can provide valid and sensitive measures of postural stability in children during both quiet standing and dynamic tasks12. Moreover, studies aiming to develop accelerometric tools for pediatric balance have shown moderate correlations between accelerometric metrics (e.g., root mean square, mediolateral acceleration) and traditional clinical tests, such as Flamingo and balance beam, suggesting the feasibility of quantitative signal-based assessment9. These findings indicate that accelerometry holds promise as an objective, quantitative, and practical alternative to subjective field tests in school-age populations–but further methodological development and validation are required.

Accelerometry produces high-dimensional time-series data that are often non-linear and difficult to interpret with conventional statistical approaches. Machine learning (ML) techniques are increasingly employed to analyze such data because they can model complex, multivariate relationships and identify subtle patterns relevant to clinical outcomes13,14. For example, supervised learning algorithms such as random forests, support vector regression, and k-nearest neighbors have been successfully applied to biomedical signal processing, including gait analysis and fall risk prediction in adults15,16. In pediatric populations, ML has been used to classify motor behaviors and assess physical activity levels from accelerometric signals, demonstrating strong predictive performance and practical applicability in real-world settings17,18. These findings suggest that ML could also enhance the interpretability of balance-related accelerometric data in children, offering a pathway to objective, scalable, and data-driven assessment tools. Although traditional field tests such as the Flamingo and balance beam are easy to administer, their interpretation depends on subjective observation and their reliability in children is often variable. Using accelerometric features to predict the outcomes of these tests provides two key advantages: first, it establishes a direct link between quantitative digital signals and widely recognized clinical measures, facilitating interpretability for practitioners; and second, it enables the development of automated, standardized, and potentially large-scale screening tools in school and preventive health contexts. In this way, the approach leverages accelerometry not to replace, but to enhance, the clinical utility of simple balance tests by making their assessment more objective and scalable.

Although accelerometry and machine learning have been increasingly applied in adult populations for rehabilitation, fall risk prediction, and neurological disorders, evidence in healthy children remains scarce. Most pediatric studies have focused on quantifying physical activity or classifying gross motor behaviors rather than predicting outcomes of standardized balance tests19,20. Existing research on balance assessment in school-aged children is limited to small pilot studies, often without rigorous cross-validation or direct comparison across multiple algorithms9,17. Furthermore, the few studies incorporating accelerometry into educational or preventive health contexts highlight the lack of validated protocols and raise concerns about reproducibility across settings11,18. This knowledge gap underscores the need for feasibility studies that evaluate the predictive value of accelerometric signals for clinical balance tests in schoolchildren, thereby bridging the fields of pediatric health, education, and medical informatics.

The present study addresses this gap by evaluating the feasibility of predicting outcomes of two widely used pediatric balance tests–the Flamingo single-leg stance and the balance beam walking test–using accelerometric signals in school-age children. Data were collected from static tasks (eyes open, eyes closed, and unstable surface) and dynamic gait, and several machine learning algorithms, including linear models, penalized regression, support vector regression, k-nearest neighbors, and random forest, were applied with five-fold cross-validation. By systematically comparing static versus dynamic tasks and multiple algorithms, this study provides novel evidence on the predictive value of accelerometry for pediatric balance assessment. The findings contribute to the fields of pediatric health and clinical informatics by highlighting the potential of accelerometer-based machine learning as a digital tool for objective screening, early identification of balance deficits, and integration into educational and preventive health settings.

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

A cross-sectional study was conducted to evaluate the feasibility of predicting balance performance in school-age children using accelerometric signals and machine learning models. Participants were recruited from primary schools through convenience sampling. Eligibility criteria included being between 6 and 12 years of age, absence of diagnosed neurological, musculoskeletal, or visual impairments, and ability to perform the balance tests safely. Children with recent injuries or medical conditions affecting balance were excluded. A total of 90 participants (approximately equal distribution by sex) were included in the final sample. Mean age, body mass index, and sex distribution were recorded to describe the study population.

The study protocol was approved by the institutional ethics committee in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki21. Written informed consent was obtained from parents or legal guardians, and verbal assent was provided by all participating children, consistent with recommendations for ethical research involving minors22,23. Data collection was carried out during school hours in familiar environments, which is known to increase compliance and ecological validity in pediatric balance research8,24.

Clinical balance tests (outcomes)

Two standardized field tests were used as outcome measures of balance performance. The Flamingo balance test, originally described by Eurofit protocols, assesses static balance by recording the number of times a participant loses stability while attempting to maintain a one-leg stance on a narrow support for 60 seconds25,26. A higher number of falls or corrective supports indicates poorer balance. This test is widely used in physical education and epidemiological studies because of its feasibility, though its reliability in children has shown variability8.

Dynamic balance was evaluated using the balance beam walking test, in which participants walk along a narrow beam (3 m in length, 4 cm in width, 5 cm in height), and the maximum distance covered without stepping off the beam is recorded25. This test requires continuous postural adjustments and is considered more sensitive to developmental differences in dynamic balance than static single-leg stance tests10. Both tests were administered following standardized protocols by trained examiners, ensuring consistency and comparability with prior studies of pediatric populations.

Accelerometric assessment (predictors)

Postural balance was assessed using a triaxial accelerometer (ActiGraph wGT3X-BT, ActiGraph LLC, Pensacola, FL, USA) positioned on the lower back at the level of the L4–L5 vertebrae, close to the body’s center of mass. This location has been shown to provide reliable signals for postural sway analysis in both static and dynamic tasks27. The device recorded raw accelerations on three orthogonal axes (anteroposterior, mediolateral, and vertical) at a sampling frequency of 100 Hz.

Each participant completed three static tasks of 30 seconds each: standing quietly with eyes open (EO), standing with eyes closed (EC), and standing on an unstable surface (foam pad) with eyes open (EO-foam). In addition, a dynamic walking task was performed on a 10-meter walkway at self-selected speed. These tasks were selected to capture a range of postural demands from simple to challenging, consistent with recommendations for pediatric balance assessment protocols8,11. Features from the three static conditions (EO, EC, EO-foam) were combined into a single predictor set and given jointly to the machine learning models, rather than being assessed separately. This design was chosen to maximize the amount of complementary information available from multiple static balance challenges.

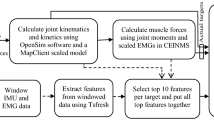

From the accelerometer signals, a comprehensive set of time- and frequency-domain features was computed for each axis (anteroposterior, mediolateral, and vertical) and for the signal vector magnitude (SVM). In the time domain, the extracted variables included mean acceleration, standard deviation, root mean square (RMS), range, skewness, kurtosis, and sway amplitude. In the frequency domain, we computed the dominant frequency, mean frequency, power spectral density (PSD) centroid, and total power within the 0.1–5 Hz band, which captures the main postural sway components in children28. Overall, 24 features (6 per axis plus 6 from the SVM signal) were obtained and used as input variables for model training.

Data preprocessing

Raw accelerometric signals were exported and processed in Python (version 3.9, Python Software Foundation). Prior to feature extraction, signals were visually inspected to ensure data quality and completeness. All accelerometric features were standardized using z-scores to account for differences in measurement units and inter-individual variability, a recommended practice in machine learning applications with biomechanical data29.

The dataset was randomly divided into training (75%) and testing (25%) sets. Model training was further evaluated using five-fold cross-validation to maximize reliability and prevent overfitting, following recommendations for small-to-moderate sample sizes in pediatric populations30. All preprocessing and model development steps were implemented using the scikit-learn library31.

Machine learning models

Several supervised machine learning algorithms were applied to predict balance test outcomes from accelerometric features. Linear regression was used as a baseline model because of its interpretability and historical use in biomedical prediction tasks32.

To capture potential nonlinearities, decision tree regression was implemented as a simple yet flexible model prone to overfitting in small datasets33. Random Forest regression, an ensemble of decision trees, was employed to improve predictive accuracy and robustness, as well as to provide insight into feature importance34.

Additional models were explored to broaden the analysis. k-Nearest Neighbors (kNN) regression was included as a non-parametric alternative that captures local similarities in the data35. Support Vector Regression (SVR) with a radial basis function kernel was tested given its effectiveness in handling nonlinear relationships in biomedical data36. Finally, Gradient Boosting regression, a sequential ensemble approach, was applied to evaluate whether boosting strategies could improve prediction stability37.

Hyperparameters for each model were tuned using grid search within the cross-validation framework. All models were implemented using the scikit-learn library (v.0.24) in Python.

Model evaluation

Model performance was assessed using two complementary metrics: the coefficient of determination (\(R^2\)) and mean squared error (MSE). The \(R^2\) statistic estimates the proportion of variance in the clinical balance tests explained by the models and is commonly reported in pediatric motor control research38. MSE quantifies prediction error in the same units as the outcomes squared and is widely recommended for evaluating regression models in biomedical informatics39.

Comparisons were performed across models and between static and dynamic accelerometric tasks. For the static conditions (eyes open, eyes closed, and eyes open on foam), all extracted accelerometric features from the three tasks were combined into a single predictor matrix and used jointly to predict both outcome variables: the number of falls in the Flamingo test and the distance walked on the balance beam. For the dynamic condition, only accelerometric features derived from the gait task were included as predictors.

Thus, the machine learning models were trained separately for each clinical outcome using the same predictor set within static or dynamic contexts. This design ensured consistency in feature input and allowed direct comparison of model performance between static and dynamic assessments.

All analyses were conducted within the five-fold cross-validation framework described previously. Performance metrics were averaged across folds to evaluate both accuracy and stability of the models.40.

Results

Participant characteristics

A total of 90 school-aged children participated in the study (47 boys, 52.2%; 43 girls, 47.8%). The mean age was 9.1 years (SD = 1.9, range 6–12). The mean body mass index (BMI) was 19.1 kg/m\(^2\) (SD = 3.6, range 14.0–28.0).

Regarding balance outcomes, the Flamingo test showed a mean of 3.6 falls (SD = 4.5, range 0–15) during the 60-second trial, while the balance beam test revealed a mean walking distance of 5.5 m (SD = 3.9, range 0.68–19.5). The descriptive characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1.

Model performance: overall results

The predictive performance of all six machine learning algorithms (Linear Regression, Decision Tree, Random Forest, k-Nearest Neighbors, Support Vector Regression, and Gradient Boosting) trained with static and dynamic accelerometric features is summarized in Tables 2 and 3.

Random Forest achieved the highest \(R^2\) values in both Flamingo (0.45) and balance beam (0.30) tests using static features, followed by Support Vector Regression and k-Nearest Neighbors. In contrast, models based on dynamic features showed weaker predictive power, with \(R^2\) values close to zero or negative, indicating that static balance tasks provided more informative accelerometric predictors of clinical performance than dynamic gait variables in this sample of school-aged children.

Detailed five-fold cross-validated performance metrics for all tested models, including Support Vector Regression, k-Nearest Neighbors, and Gradient Boosting, are presented in Tables 2 and 3. These results confirm that while Random Forest achieved the best overall accuracy, SVR and kNN obtained comparable yet slightly lower \(R^2\) values in the Flamingo test, and all models performed weakly for dynamic conditions.

Comparison between static and dynamic tasks

To assess the relative contribution of accelerometric features derived from static and dynamic tasks, separate models were trained for each condition. As summarized in Tables 2–3, static balance variables provided higher predictive accuracy than dynamic gait features across all models.

To complement the summary in Tables 2–3, Figure 1 shows participant-level scatter plots of predicted versus observed values for both outcomes and both task conditions using the Random Forest model. Each dot represents one participant and the dashed line indicates identity (\(y=x\)). This visualization makes the distribution of errors and the between-participant variability explicit, and it illustrates more clearly that static features outperform dynamic features.

Predicted vs. observed values for the 90 participants using the Random Forest model. Top-left: Static–Flamingo; top-right: Static–Balance beam; bottom-left: Dynamic–Flamingo; bottom-right: Dynamic–Balance beam. The dashed line indicates identity (\(y=x\)). Numerical performance (R\(^2\), MSE) for each condition is summarized in Tables 2–3.

Discussion

This study evaluated the feasibility of predicting outcomes of two widely used pediatric balance tests–the Flamingo and balance beam–using accelerometric features analyzed with supervised machine learning models. The main findings were that (i) static accelerometric variables were more informative than dynamic gait variables, and (ii) Random Forest regression achieved the highest predictive performance, particularly for the Flamingo test. However, prediction accuracy for the balance beam test was consistently weaker across all models.

The superior predictive value of static tasks is consistent with previous research showing that accelerometric sway metrics are sensitive indicators of postural control in children during quiet standing9,12. In contrast, dynamic gait variables showed limited association with balance outcomes, possibly due to the complexity and variability of gait strategies in school-aged populations, as well as the short walkway protocol employed. This may be due to the higher variability of gait strategies in school-aged children, as well as the relatively short walkway protocol used, which might not have captured enough variability to reflect individual balance capacities. These results suggest that static accelerometric assessments may better capture the fundamental postural control mechanisms that underlie performance in standardized balance tests.

Among the models tested, Random Forest consistently outperformed linear and single-tree approaches, highlighting the importance of ensemble methods in handling noisy biomedical data and capturing nonlinear relationships34. While Support Vector Regression and k-Nearest Neighbors have shown competitive results in prior pediatric studies17, in our dataset their performance was slightly below that of Random Forest in static conditions and consistently poor for dynamic tasks, as detailed in Tables 2–3. The modest \(R^2\) values (up to 0.45 for Flamingo and 0.30 for balance beam) indicate that although feasible, accelerometry-based machine learning should be considered as a complementary rather than standalone tool for balance assessment at this stage.

The clinical and educational implications of these findings are notable. Objective accelerometry-based predictions may provide a scalable digital tool for early screening of balance deficits in schools, reducing reliance on subjective observation alone. Integration into physical education or preventive health programs could support more individualized monitoring of motor development and targeted interventions in at-risk children. From a practical perspective, these findings suggest that accelerometry-informed predictions could support scalable, objective screening of balance deficits in schools or preventive health programs. For instance, such tools could enable longitudinal monitoring of motor development, early detection of children at risk, and integration with digital educational platforms. However, clinical decision-making should not rely exclusively on these models given their moderate accuracy.

Several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the sample size was modest (N = 90), which restricts generalizability and may have limited the stability of model estimates. Second, accelerometric features were extracted from a single sensor at the lumbar level; multi-sensor approaches or higher-frequency data may enhance predictive power. Third, only traditional machine learning algorithms were explored; deep learning methods such as convolutional or recurrent neural networks may further improve performance but require larger datasets14. Finally, clinical outcomes were limited to two field tests, and the predictive framework should be validated against broader functional and developmental measures (e.g., force platform assessments, developmental scales).

Another limitation is that accelerometric signals were not recorded during the Flamingo or balance beam tests themselves, but rather during independent static and gait tasks. While this design allowed us to explore the predictive value of separate accelerometric assessments, recording directly during the clinical tests could serve as an additional validation strategy and may yield higher predictive accuracy. Future work should investigate the added value of combining task-specific recordings with independent balance tasks.

Future research should focus on standardizing accelerometric protocols for pediatric balance assessment, expanding datasets across diverse populations, and integrating longitudinal monitoring to track developmental changes. Combining accelerometry with other modalities such as video analysis or force platforms may also yield richer predictive models.

Overall, this study provides novel evidence that accelerometric features from static tasks, analyzed with machine learning models, can modestly predict outcomes of the Flamingo and balance beam tests in school-aged children. While performance remains limited, these findings support the feasibility of accelerometry-based machine learning as a step toward more objective, data-driven approaches to balance screening in pediatric health and education.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated the feasibility of using accelerometric features and machine learning models to predict clinical balance test outcomes in school-aged children. Static accelerometric tasks provided more informative predictors than dynamic gait features, with Random Forest achieving the highest performance (\(R^2\) up to 0.45 for the Flamingo test and 0.30 for the balance beam).

Although predictive accuracy was modest, these findings highlight the potential of accelerometry-based machine learning as an objective, scalable complement to traditional field tests. In particular, the Flamingo test appeared more suitable for accelerometry-informed prediction than the balance beam.

Further research with larger and more diverse cohorts, standardized accelerometric protocols, and advanced modeling approaches is warranted to confirm these results and move toward practical implementation in pediatric health and educational settings.

Data availability

The code and dataset supporting this study are openly available on Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16888953

References

Kyvelidou, A., DeVeney, S. & Katsavelis, D. Development of infant sitting postural control in three groups of infants at various risk levels for autism spectrum disorder. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 20(2), 1234. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021234 (2023).

Azevedo, N., Ribeiro, J. C. & Machado, L. Balance and posture in children and adolescents: A cross-sectional study. Sensors 22(13), 4973. https://doi.org/10.3390/s22134973 (2022).

Omaki, E. et al. Understanding the circumstances of paediatric fall injuries: Machine learning analysis of neiss narratives. Injury Prevention 29(5), 384–388. https://doi.org/10.1136/ip-2023-044858 (2023).

Breen, E. O., Howell, D. R., Stracciolini, A., Dawkins, C. & Meehan, W. P. I. Examination of age-related differences on clinical tests of postural stability. Sports Health 8(3), 244–249. https://doi.org/10.1177/1941738116633437 (2016).

García-Liñeira, J., Leirós-Rodríguez, R., Romo-Pérez, V. & García-Soidán, J. L. Static and dynamic postural control assessment in schoolchildren: Reliability and reference values of the modified flamingo test and bar test. J. Bodywork Movement Therapies 36, 14–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbmt.2023.05.006 (2023).

Paniccia, M. et al. Postural stability in healthy child and youth athletes: The effect of age, sex, and concussion-related factors on performance. Sports Health 10(2), 175–182. https://doi.org/10.1177/1941738117741651 (2018).

Wyszyńska, J. et al. Physical activity in the prevention of childhood obesity: The position of the European childhood obesity group and the european academy of pediatrics. Front. Pediat. 8, 535705. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2020.535705 (2020).

Sember, V., Grošelj, J. & Pajek, M. Balance tests in pre-adolescent children: Retest reliability, construct validity, and relative ability. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17(15), 5474. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17155474 (2020).

García-Liñeira, J., Leirós-Rodríguez, R., Romo-Pérez, V. & García-Soidán, J. L. Validity and reliability of a tool for accelerometric assessment of balance in scholar children. J. Clin. Med. 10(1), 137. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10010137 (2021).

Westcott, S. L., Lowes, L. P. & Richardson, P. K. Evaluation of postural stability in children: Current theories and assessment tools. Phys. Therapy 77(6), 629–645. https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/77.6.629 (1997).

García-Soidán, J. L., Leirós-Rodríguez, R., Romo-Pérez, V. & García-Liñeira, J. Accelerometric assessment of postural balance in children: A systematic review. Diagnostics 11(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics11010008 (2021).

Valenciano, P. J. Use of accelerometry to investigate standing and dynamic body balance in people with cerebral palsy. Gait Posture 96, 357–364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaitpost.2022.06.017 (2022).

Shah, P. et al. Artificial intelligence and machine learning in clinical development: A translational perspective. NPJ Digit. Med. 2, 69. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-019-0148-3 (2019).

Rajpurkar, P., Chen, E., Banerjee, O. & Topol, E. J. AI in health and medicine. Nat. Med. 28, 31–38. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-021-01614-0 (2022).

Delahoz, Y. S. & Labrador, M. A. Survey on fall detection and fall prevention using wearable and external sensors. Sensors 14(10), 19806–19842. https://doi.org/10.3390/s141019806 (2014).

Gade, G. V. et al. Predicting falls in community-dwelling older adults: A systematic review of prognostic models. BMJ Open 11(5), 044170. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-044170 (2021).

Ahmadi, M. N., O’Neil, M. E., Worthen-Chaudhari, L. C., Spees, W. M. & Chae, J. Machine learning algorithms for classification of postural control in children with cerebral palsy using accelerometer data. Sensors 20(14), 3976. https://doi.org/10.3390/s20143976 (2020).

Cardinale, M. & Varley, M. C. Wearable training-monitoring technology: Applications, challenges, and opportunities. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 12(Suppl 2), 255–262. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijspp.2016-0423 (2017).

Kristoffersson, A. & Lindén, M. A systematic review of wearable sensors for monitoring physical activity. Sensors 22(2), 573. https://doi.org/10.3390/s22020573 (2022).

Steins, D., Dawes, H., Esser, P. & Collett, J. Wearable accelerometry-based technology capable of assessing functional activities in neurological populations in community settings: a systematic review. J. Neuro. Eng. Rehabilit. 11, 36. https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-0003-11-36 (2014).

World Medical Association. World medical association declaration of helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 310(20), 2191–2194. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.281053 (2013).

Barker, J. & Weller, S. Is it fun? developing children centred research methods. Int. J. Sociol. Social Policy 23(1/2), 33–58. https://doi.org/10.1108/01443330310790435 (2003).

Beauchamp, T. L. & Childress, J. F. Principles of Biomedical Ethics 8th edn. (Oxford University Press, Oxford, England, 2019).

Liu, W. Y. et al. Knowledge, attitude, and practice regarding falls and fall prevention among older people from Shanghai, China: A cross-sectional study. Front. Public Health 10, 848122. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.848122 (2022).

Council of Europe Committee for the Development of Sport: Eurofit: Handbook for the Eurofit Tests of Physical Fitness. Council of Europe, Committee for the Development of Sport, Rome (1988).

Ruiz, J. R. et al. Field-based fitness assessment in young people: the alpha health-related fitness test battery for children and adolescents. British J. Sports Med. 45(6), 518–524. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsm.2010.075341 (2011).

Leirós-Rodríguez, R., Arce, M.E., Míguez-Álvarez, C. & García-Soidán, J.L. Definition of the proper placement point for balance assessment with accelerometers in older women. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ramd.2016.09.001 . Accessed 2025-08-17.

Paillard, T. & Noé, F. Techniques and methods for testing the postural function in healthy and pathological subjects. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 891390. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/891390 (2015).

Jurić, T. et al. Daily activity recognition with accelerometer data using a random forest model. Sensors 20(20), 5893. https://doi.org/10.3390/s20205893 (2020).

Varoquaux, G. Cross-validation failure: Small sample sizes lead to large error bars. NeuroImage 180, 68–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.06.061 (2018).

Pedregosa, F. et al. Scikit-learn: Machine learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 12, 2825–2830 (2011).

Montgomery, D. C., Peck, E. A. & Vining, G. G. Introduction to linear regression analysis 6th edn. (Wiley, Weinheim, Germany, 2021).

Breiman, L., Friedman, J. H., Olshen, R. A. & Stone, C. J. Classification and regression trees (Chapman & Hall/CRC, New York, 1984). https://doi.org/10.1201/9781315139470.

Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 45(1), 5–32. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010933404324 (2001).

Altman, N. S. An introduction to kernel and nearest-neighbor nonparametric regression. Am. Stat. 46(3), 175–185. https://doi.org/10.1080/00031305.1992.10475879 (1992).

Smola, A. J. & Schölkopf, B. A tutorial on support vector regression. Stat. Comput. 14(3), 199–222. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:STCO.0000035301.49549.88 (2004).

Friedman, J. H. Greedy function approximation: A gradient boosting machine. Ann. Stat. 29(5), 1189–1232. https://doi.org/10.1214/aos/1013203451 (2001).

Carlson, A. G., Rowe, E. & Curby, T. W. Disentangling fine motor skills’ relations to academic achievement: The relative contributions of visual-spatial integration and visual-motor coordination. J. Genet. Psychol. 174(5–6), 514–533. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221325.2012.717122 (2013).

Chicco, D., Warrens, M. J. & Jurman, G. The coefficient of determination r-squared is more informative than SMAPE, MAE, MAPE, MSE and RMSE in regression analysis evaluation. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 7, 623. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.623 (2021).

Varoquaux, G. et al. Assessing and tuning brain decoders: Cross-validation, caveats, and guidelines. NeuroImage 145, 166–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.10.038 (2017).

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.A.B.-A., E.G.-M., and S.R.-M. conducted data preprocessing, coding, programming, and machine learning analyses. J.A.B.-A. wrote the main manuscript text, prepared tables and figures, and performed the literature review. E.G.-M. and S.R.-M. contributed to feature extraction, result generation, and manuscript revision. A.G.-C. assisted in data collection, clinical test administration, and manuscript preparation. R.L.-R. and C.P.-G. supervised the study design, provided critical feedback, and contributed to the interpretation of findings. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to this work. The people involved in the experiment have been informed and formally accepted.

Consent for publication

Not applicable. This manuscript does not contain personal data, images, or videos from any individual.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Benítez-Andrades, J.A., González-Castro, A., González-Marcos, E. et al. Feasibility of accelerometer-based prediction of postural balance in schoolchildren using machine learning models. Sci Rep 15, 45349 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30160-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30160-9