Abstract

Periodontitis is a prevalent inflammatory disease characterized by immune dysregulation and tissue destruction, yet the molecular mechanisms linking metabolic epigenetic modifications and immune responses remain insufficiently understood. Recent evidence suggests protein lactylation plays a pivotal role in shaping immune landscapes in chronic inflammation, but its relevance in periodontitis is largely unexplored. We systematically analyzed microarray-based bulk gene expression datasets from gingival tissues and single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) data derived from peripheral blood mononuclear cells of periodontitis patients and healthy controls. Differentially expressed lactylation-associated genes (DE-LACRGs) were identified using established bioinformatics workflows. Immune infiltration was assessed by single-sample gene set enrichment analysis, while unsupervised subtyping was conducted using nonnegative matrix factorization. Machine learning algorithms, including least absolute shrinkage and selection operator regression, random forest, and extreme gradient boosting, prioritized key diagnostic LACRGs. Single-cell analyses mapped immune cell heterogeneity and pathway activity, with a focus on natural killer (NK) cell subpopulations. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) validated target gene expression in clinical gingival samples. Twelve DE-LACRGs were identified as differentially expressed in periodontitis. Integrative machine learning approaches robustly prioritized ELL-associated factor 1 (EAF1), neurofilament light chain (NEFL), and vimentin (VIM) as the core diagnostic markers. The composite gene signature demonstrated strong diagnostic performance, with area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) values of 0.919 in the GSE10334 cohort and 0.891 in the GSE16134 cohort. IHC analysis of gingival specimens confirmed elevated VIM expression and reduced EAF1 and NEFL in periodontitis compared to healthy controls, supporting transcriptome-level findings. Molecular subtyping based on LACRG expression separated patients into clusters with distinct immune activation profiles. Immune infiltration analysis revealed significantly increased proportions of NK cells, CD8 + T cells, and other pro-inflammatory subsets in diseased tissues, while regulatory T cells were notably decreased, underscoring a shift toward heightened immune activation in periodontitis. scRNA-seq further demonstrated increased NK cell heterogeneity and identified cell type–specific expression patterns for the diagnostic gene signature. LACRGs are integrally involved in immune remodeling and inflammation in periodontitis. Multi-level integrative analyses highlight their diagnostic value and illuminate new targets for understanding and potentially modulating the metabolic-epigenetic-immune axis in periodontal disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Periodontitis is a prevalent and complex inflammatory disease that leads to the progressive destruction of gingival tissue and alveolar bone, often culminating in tooth loss if left untreated1. Its pathogenesis is primarily orchestrated by a dysregulated host immune response to pathogenic microorganisms, resulting in chronic inflammation and tissue breakdown2. Despite significant progress in elucidating the microbial and immunological underpinnings of periodontitis, reliable molecular biomarkers for early diagnosis and precise patient stratification remain lacking, thus posing challenges for timely intervention and personalized therapy3,4,5.

A growing body of evidence highlights the pivotal role of post-translational modifications (PTMs) in regulating gene expression, cellular signaling, and immune homeostasis in the context of inflammatory diseases6,7. Among these, protein lactylation-a recently discovered acylation modification involving the addition of a lactyl group to lysine residues-has emerged as a critical metabolic-epigenetic nexus8,9. It has been demonstrated that lactylation can dynamically modulate histone and non-histone protein function, thereby influencing gene transcription, immune cell plasticity, and inflammation resolution10.

Importantly, recent studies suggest an intimate relationship between lactylation and immune cell regulation11,12. Lactylation has been implicated in controlling macrophage polarization, with increased lactate availability driving the lactylation of key transcriptional regulators and thereby promoting the switch between pro-inflammatory M1 and anti-inflammatory M2 phenotypes13,14. Additionally, lactylation is increasingly recognized as a mediator of adaptive immune responses, as it can fine-tune the activity and differentiation of various lymphocyte subsets, modulate cytokine production, and orchestrate immune-metabolic crosstalk during inflammation and tissue repair15,16. These findings collectively indicate that aberrant lactylation may contribute to the immune dysfunction and chronicity of inflammatory diseases such as periodontitis, although its specific roles and mechanisms in periodontal pathology remain to be elucidated.

The advent of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized our ability to resolve the cellular heterogeneity and molecular complexity of chronic inflammatory diseases, enabling the identification of previously unrecognized immune cell subsets and disease-associated functional states17,18. Moreover, integrative bioinformatics analyses combining bulk gene expression microarray datasets and scRNA-seq, immune profiling, and machine learning have emerged as powerful strategies to uncover disease-driving regulatory genes, infer immune landscape dynamics, and discover robust molecular biomarkers with translational potential.

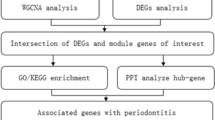

In this study, we undertook a comprehensive investigation of lactylation-associated genes (LACAGs) in periodontitis by integrating bulk gene expression microarray datasets and scRNA-seq data, immune cell infiltration analyses, machine learning-driven biomarker identification, and clinical sample validation. By delineating the interplay between lactylation, immune regulation, and disease heterogeneity, our findings provide new insights into the epigenetic mechanisms underlying periodontitis and establish a foundation for the development of precise diagnostic and therapeutic strategies targeting lactylation-mediated immune pathways.

Methods

Study design and data collection

We systematically evaluated lactylation-related genes in periodontitis using public Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) datasets and our clinical samples. The discovery cohort GSE16134 comprised non‑smoker gingival tissue bulk gene expression microarray profiles from 241 periodontitis samples and 69 healthy samples19. The validation cohort GSE10334 included non‑smoker gingival tissue bulk gene expression microarray profiles from 183 periodontitis and 64 control samples using the same criteria20. For cell‑type–resolved analyses, we analyzed the scRNA‑seq dataset GSE244515 of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from 21 donors (10 periodontitis, 11 controls)21. Full dataset characteristics are summarized in Table S1.

Differentially expressed lactylation-related genes identification

A comprehensive list of LACAGs was curated from published literature and relevant databases22. Differential expression analysis between periodontitis patients and healthy controls was performed on the GSE16134 microarray dataset using the “limma” R package. Genes with an adjusted p-value < 0.05 and |log2(fold change) | > 1 were considered differentially expressed genes (DEGs). The intersection of DEGs and LACAGs defined differentially expressed lactylation-associated genes (DE-LACAGs), which were prioritized for downstream analyses. Volcano plots and heatmaps were generated using the “ggplot2” and “pheatmap” packages, respectively, to visualize gene expression patterns.

Functional enrichment analysis and molecular subtype identification

Functional annotation of DE-LACAGs was conducted using Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analyses23,24, implemented via the “clusterProfiler” R package25. GO categories included biological process, cellular component, and molecular function. Enriched terms with a false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05 were considered significant. Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was performed using the “clusterProfiler” and “fgsea” packages to evaluate pathway activation between molecular subtypes.

Unsupervised molecular subtyping of periodontitis patients based on expression profiles of DE-LACAGs was performed using the Non-negative Matrix Factorization (NMF) algorithm implemented in the “NMF” R package26. The optimal number of clusters (k) was determined by evaluating cophenetic correlation coefficient, dispersion, and silhouette width, alongside visual inspection of the consensus heatmap. Sample assignment to molecular subtypes was based on the maximum NMF basis vector coefficient.

Key lactylation-related genes identification by machine learning framework

To identify key lactylation-related genes with diagnostic potential, three machine learning algorithms were employed: least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) regression, random forest (RF), and extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost). LASSO regression was performed using the “glmnet” package, with ten-fold cross-validation to select the optimal λ. RF and XGBoost models were constructed using the “randomForest” and “xgboost” packages, respectively, with feature importance scores extracted for gene ranking. Genes consistently identified by multiple algorithms were considered key diagnostic markers and subjected to further validation. Venn diagrams were generated using the “VennDiagram” package to show overlap among selected genes.

Immune cell infiltration analysis

Immune cell infiltration and immune function activity were estimated by single-sample gene set enrichment analysis (ssGSEA) using the “GSVA” package27. Complex heatmaps were generated with the “ComplexHeatmap” package to visualize the abundance and activity differences between periodontitis and healthy groups. Pairwise Pearson correlation analysis was performed to examine relationships among immune cell populations and immune functions across disease states. GSEA was also used to compare immune pathway activation between clusters.

Single-Cell RNA sequencing analysis

Single-cell RNA sequencing analysis was performed using the GSE244515 dataset21. Quality control, normalization, principal component analysis (PCA), and clustering were conducted with the “Seurat“(version 4.3.0) R package. Uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) was used for dimensionality reduction and visualization. Marker genes for each cluster were identified using the “FindAllMarkers” function. Cell type annotation was performed by integrating canonical marker expression and using the “SingleR” package28. For NK cell subpopulations, reclustering was conducted, and clusters were annotated based on the expression of top marker genes. Pseudotime trajectory analysis was performed using the “Monocle” package29 to infer dynamic differentiation states of NK cells. Immune-related gene set enrichment analysis at the single-cell level (irGSEA) was performed using the “irGSEA” package. Gene set variation analysis (GSVA) was further used to evaluate pathway activity among NK cell subpopulations.

Tissue sample collection and immunohistochemistry staining

We collected gingival tissue specimens from eight periodontitis patients and eight periodontally healthy controls for immunohistochemical (IHC) validation at the Department of Stomatology, First Hospital of Northwest University. All participants provided written informed consent prior to sample acquisition. The study was approved by the hospital’s Ethics Committee (Ethics Approval No.: 2024KY‑04) and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Periodontitis was diagnosed according to the 2017 World Workshop consensus30. Specifically, periodontitis was defined by either (i) interdental CAL detectable at ≥ 2 non‑adjacent teeth, or (ii) buccal/oral CAL ≥ 3 mm with probing PD > 3 mm at ≥ 2 teeth, and the observed CAL could not be attributed to non‑periodontal causes (including traumatic gingival recession, cervical caries, distal CAL at second molars related to third molar malposition/extraction, endodontic lesions draining through the marginal periodontium, or vertical root fractures). Periodontally healthy status required probing PD ≤ 3 mm, no CAL, and no bleeding on probing (BOP) at sampled sites; at the whole‑mouth level, gingival health (BOP < 10% and no sites with PD > 3 mm) was required.

All participants underwent a full‑mouth periodontal examination by a calibrated periodontist. PD and CAL were recorded at six sites per tooth using a UNC‑15 periodontal probe; BOP and a plaque index were assessed at the same sites. Radiographic evaluation of alveolar bone levels was performed as available to support staging and grading. Periodontitis stage and grade were assigned following the 2017 classification framework; staging considered severity/complexity (interdental CAL, radiographic bone loss, tooth loss due to periodontitis), and grading reflected progression risk and impact of risk factors (e.g., smoking, diabetes). Baseline characteristics were recorded for all participants and are summarized in Table S2. Gingival tissue samples, including both oral and sulcular epithelium with underlying connective tissue, were obtained from the mesiobuccal aspect of the maxillary premolar region. For the periodontitis group, samples were collected from the pocket wall at diseased sites to ensure site‑specific relevance. For the healthy group, gingival tissues were obtained from clinically healthy sites during procedures unrelated to periodontal disease (e.g., flap reflection for impacted third molar surgery or orthodontic extraction), and all sampled healthy sites fulfilled the criteria above. Exclusion criteria included children, pregnant or lactating women, individuals with cognitive impairment or dementia, and patients with systemic comorbidities.

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues were sectioned and processed using standard protocols for deparaffinization, rehydration, and antigen retrieval. Sections were incubated with primary antibodies against ELL-associated factor 1 (EAF1, Cat No. #PJH736546S, Abmart), neurofilament light chain (NEFL, Cat No. #GB115734, Servicebio), and vimentin (VIM, Cat No. #GB11192, Servicebio), and immunoreactivity was visualized using a chromogenic detection system. Whole-slide images were acquired by scanning the stained sections with a 3DHISTECH digital slide scanner. Immunohistochemistry images were subsequently captured and exported at both low (100 μm) and high (50 μm) magnification using the CaseViewer software (3DHISTECH, Budapest, Hungary).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using R (version 4.2.0) unless otherwise specified. Differences between groups were assessed by Student’s t-test or Wilcoxon rank-sum test, as appropriate. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves and area under the curve (AUC) values were calculated using the “pROC” package to evaluate diagnostic performance (Robin et al., 2011). Correlation analyses were performed by Pearson’s correlation coefficient. For multi-group comparisons, one-way ANOVA or Kruskal-Wallis test was used as appropriate. All p-values were two-sided, and p-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Identification of differentially expressed Lactylation-Related genes in periodontitis

To explore the role of lactylation in the pathogenesis of periodontitis, we first curated a comprehensive list of 327 LACAGs from current literature and public databases, as detailed in Table S3. We then evaluated their expression profiles in the GSE16134 microarray dataset. Differential expression analysis between periodontitis patients and healthy controls identified a total of 722 DEGs, among which 458 genes were significantly upregulated and 264 genes were downregulated in periodontitis (adjusted p-value < 0.05, |log2FC| > 1) (Fig. 1A). Subsequently, we intersected these DEGs with our lactylation-related gene set, resulting in the identification of 12 DE-LACAGs (Fig. 1B). To visualize the expression patterns of these 12 DE-LACAGs, we performed hierarchical clustering and generated a heatmap (Fig. 1C). The results revealed distinct expression profiles that clearly separated periodontitis patients from healthy subjects, underscoring the potential of these genes as molecular indicators.

Expression patterns, enrichment analysis, and molecular subtypes of differentially expressed lactylation-related genes in periodontitis. (A) Volcano plot depicting the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between periodontitis patients and healthy controls. (B) Venn diagram showing the overlap of DEGs and lactylation-associated genes (LACAGs). Twelve genes were identified as both DEGs and LACAGs and defined as differentially expressed lactylation-associated genes (DE-LACAGs) for subsequent analysis. (C) Heatmap displaying the expression profiles of the 12 DE-LACAGs across individual samples. (D-G) Gene Ontology (GO) biological process enrichment (D), cellular component enrichment (E), molecular function enrichment (F), and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment (G) analyses for DE-LACAGs. (H) Cophenetic coefficient plot for consensus clustering, indicating the optimal number of clusters (k = 2) for subtype identification based on DE-LACAG expression. (I) Consensus matrix heatmap of the unsupervised consensus clustering results, illustrating the stability and separation of the two identified molecular subtypes (Cluster1 and Cluster2). (J) Stacked bar plot showing the proportion of periodontitis and healthy samples within each NMF‑derived subtype.

Functional enrichment and molecular subtype identification

To investigate the functional implications of these DE-LACAGs, GO enrichment analysis was conducted. We found that these genes were significantly enriched in biological processes and functions related to filament organization, T cell activation, glial cell differentiation, and the structural constituents of the cytoskeleton (Fig. 1D-F). This suggests their close involvement in immune regulation and tissue structural changes associated with periodontitis. KEGG pathway enrichment further highlighted the association of these lactylation-related DEGs with critical signaling pathways, including the C-type lectin receptor signaling pathway, estrogen signaling pathway, and cytoskeleton regulation in muscle cells (Fig. 1G). These pathways may play important roles in modulating immune responses and maintaining tissue integrity in the context of chronic periodontal inflammation. To further illustrate the clinical relevance of these DE-LACAGs, we performed molecular subtype identification of periodontitis patients based on the expression patterns of these genes using NMF clustering. This analysis stratified the patient cohort into two distinct clusters (Fig. 1H). Notably, the majority of Cluster 1 samples corresponded to periodontitis patients, whereas Cluster 2 consisted primarily of healthy individuals (Fig. 1I), indicating that these DE-LACAGs can effectively distinguish between diseased and healthy states. Together, these findings suggest that dysregulated lactylation may contribute to pathogenic processes in periodontitis and hold promise as molecular biomarkers for patient classification.

Machine Learning-Based identification and validation of key diagnostic genes

To further dissect the molecular subtypes identified via NMF clustering, we performed GSEA to compare the biological processes activated in Cluster 1 and Cluster 2. The results revealed that Cluster 1 exhibited significant activation of multiple immune-related pathways, including inflammatory response, chemokine signaling, IL6/JAK/STAT3 signaling, JAK/STAT pathway, interferon gamma response, T cell mediated immunity, T cell differentiation, antigen presentation, and NK cell mediated cytotoxicity (Fig. 2A). Conversely, biological processes associated with periodontal tissue development, such as keratinocyte differentiation and cornified envelope formation, were markedly suppressed in Cluster 1 compared to Cluster 2, highlighting a pronounced shift from tissue homeostasis to immune-driven pathology in periodontitis.

Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) between clusters and key differential lactylation-related gene selection using machine learning. (A) GSEA plots comparing the enrichment of hallmark pathways between the two molecular clusters identified based on lactylation-related genes. (B) Least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) regression coefficient profiles depicting the trajectory of each gene as a function of log(λ). (C) Ten-fold cross-validation for LASSO regression showing the relationship between mean cross-validated error and log(λ). (D) Bar plot of key variables selected by LASSO model. (E) Random forest classifier error plot illustrating the relationship between the number of trees and the out-of-bag (OOB) error rate for model optimization and stability assessment. (F) Top five important genes in the random forest (RF) model identified based on variable importance scores. (G) Top five important genes in the extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost) model identified according to their importance in the model. (H) Venn diagram displaying the overlap of key lactylation-related genes identified by the LASSO, random forest (RF), and XGBoost machine learning algorithms.

To identify the most relevant lactylation-related genes with diagnostic potential, we applied three complementary machine learning algorithms-LASSO regression, random forest, and XGBoost-using the bulk expression profiles of lactylation-associated genes. LASSO regression analysis narrowed down the candidate list to eight key genes (Fig. 2B, C), among which VIM, AT-rich interaction domain 3 A (ARID3A), myeloid cell nuclear differentiation antigen (MNDA), and lymphocyte cytosolic protein 1 (LCP1) showed a positive correlation with periodontitis, while calmodulin-like 5 (CALML5), cysteine and glycine rich protein 2 (CSRP2), NEFL, and EAF1 demonstrated a negative association (Fig. 2D). Random forest analysis further prioritized gene importance, with NEFL, EAF1, ARID3A, lymphocyte-specific protein 1 (LSP1), and VIM ranking as the top five predictors (Fig. 2E, F). Similarly, XGBoost identified NEFL, EAF1, LCP1, VIM, and LSP1 as crucial diagnostic genes (Fig. 2G). By intersecting the results of all three algorithms, three robust lactylation-related genes-EAF1, NEFL, and VIM-emerged as consensus biomarkers for periodontitis (Fig. 2H).

The diagnostic validity of these candidate genes was then systematically evaluated in the GSE16134 and GSE10334 microarray datasets, as well as in gingival tissue samples collected from clinical subjects. Both NEFL and EAF1 were expressed at higher levels in the gingival tissue of healthy individuals, whereas VIM was markedly upregulated in periodontitis patients (Fig. 3A, B). Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis confirmed excellent diagnostic performance for all three markers, with area under the curve (AUC) values for NEFL (GSE10334: 0.875 [0.825–0.925]; GSE16134: 0.854 [0.797–0.910]), EAF1 (GSE10334: 0.821 [0.759–0.883]; GSE16134: 0.845 [0.785–0.906]), and VIM (GSE10334: 0.786 [0.724–0.847]; GSE16134: 0.734 [0.661–0.807]) (Fig. 3C, D). Validation using immunohistochemistry further demonstrated that VIM protein levels were significantly elevated in gingival tissue from periodontitis patients, whereas EAF1 and NEFL were predominantly expressed in healthy controls (Fig. 3E-G).

Validation of three key lactylation-related genes identified by machine learning in external datasets and clinical samples. (A, B) Violin plots illustrating the mRNA expression levels of EAF1, NEFL, and VIM in healthy controls and periodontitis patients from the GSE16134 (A) and GSE10334 (B) microarray-based cohorts. (C, D) Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves assessing the diagnostic performance of EAF1, NEFL, and VIM for distinguishing periodontitis from healthy samples in the GSE16134 (C) and GSE10334 (D) microarray-based cohorts. (E-G) Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining of EAF1 (E), NEFL (F), and VIM (G) proteins in gingival tissues from healthy subjects and periodontitis patients. (H, I) Left: violin plots showing comparison of lactylation-related gene scores (LACGs score) between healthy and periodontitis groups in the GSE16134 (H) and GSE10334 (I) microarray-based cohorts. Right: ROC curves evaluating the discriminatory power of the LACGs score for periodontitis diagnosis in each cohort.

To integrate these markers into a practical diagnostic tool, we constructed an aggregated LACRGs score. This score was calculated as the sum of the normalized gene expression values of EAF1, NEFL, and VIM, each weighted by their respective regression coefficients from logistic regression modeling. After z-score normalization, patients were classified as high LACRGs score (score ≥ 0) or low LACRGs score (score < 0). Notably, periodontitis patients exhibited significantly higher LACRGs scores than healthy controls, and the composite score outperformed individual genes in distinguishing periodontitis, as demonstrated by AUC values of 0.919 [0.876–0.963] in GSE10334 and 0.891 [0.836–0.947] in GSE16134 (Fig. 3H, I). Collectively, these findings highlight the diagnostic and stratification potential of the EAF1, NEFL, and VIM gene signature, offering new molecular biomarkers for precision periodontitis management.

Altered immune cell infiltration in periodontitis and immune function correlation

GSEA initially indicated aberrant immune activation in periodontitis samples compared to healthy controls. To gain further insight into the immune microenvironment, we applied ssGSEA to microarray-based bulk gene expression data from both the GSE16134 and GSE10334 cohorts, quantifying the abundance of various immune cell types and evaluating immune function activity. The results demonstrated a significant increase in the infiltration of several pro-inflammatory immune cells in the gingival tissue of periodontitis patients. Specifically, there was a marked elevation in the abundance of dendritic cells (DCs), B cells, CD8 + T cells, natural killer (NK) cells, and macrophages relative to normal controls (Fig. 4A, C). Conversely, the infiltration of regulatory T cells (Tregs)-which are typically associated with the suppression of inflammatory responses-was significantly reduced in periodontitis samples (Fig. 4A, C). This shift in immune cell composition points toward a robustly activated, inflammation-promoting microenvironment characteristic of periodontitis. Further analysis of immune function pathways via ssGSEA corroborated these findings, revealing widespread upregulation of immune-related processes in periodontitis tissues, including enhanced cytokine signaling, antigen presentation, and cell-mediated cytotoxicity (Fig. 4B, D). Pairwise correlation analyses between immune cell subsets and between immune functional signatures illustrated a more intricate network of interactions in periodontitis patients compared to healthy controls. In particular, pro-inflammatory immune cell populations such as macrophages, activated T cells, and DCs displayed closer inter-relationships, whereas regulatory cell populations were less prominent. These complex cellular interactions may reflect dysregulated immune homeostasis and perpetuation of chronic inflammation in periodontitis (Fig. 4B, D). Taken together, these results suggest that the abnormal activation and infiltration of specific immune cell types, along with altered immune function, play a central role in the immunopathogenesis of periodontitis. Moreover, the observed immune landscape alterations may be linked to the dysregulation of lactylation-related genes, further shaping the chronic inflammatory milieu of the disease.

Immune infiltration analysis in periodontitis and healthy individuals. (A) Complex heatmap of immune cell infiltration and immune function scores calculated by single-sample gene set enrichment analysis (ssGSEA) in the GSE16134 microarray dataset, comparing periodontitis patients and healthy controls. (B) Correlation heatmap displaying pairwise Pearson correlation coefficients among different immune cells and immune functions in the GSE16134 microarray dataset. Correlations for periodontitis patients are shown in the upper triangle, and for healthy controls in the lower triangle. (C) Complex heatmap of immune cell infiltration and immune function scores by ssGSEA in the GSE10334 microarray dataset, comparing periodontitis and healthy groups. (D) Correlation heatmap of immune cells and immune functions in the GSE10334 microarray dataset, with the upper triangle showing correlations in periodontitis patients and the lower triangle for healthy controls.

Single-cell transcriptomic profiling reveals cellular heterogeneity and validates key genes

To gain a finer resolution of the immune landscape in periodontitis, we performed scRNA-seq analysis on PBMCs from 10 periodontitis patients and 11 healthy controls (GSE244515). Following strict quality control filtering to remove low-quality cells and potential doublets (Fig. 5A, B), dimensionality reduction using principal component analysis (PCA) (Fig. 5C, D), and subsequent unsupervised clustering, the scRNA-seq data revealed a total of 16 distinct clusters (Fig. 5E-G). Marker gene expression analysis was conducted for each cluster, identifying the top five markers per cluster (Fig. 5H). Using the SingleR annotation method, these clusters were reliably classified into six major immune cell subpopulations: naïve B cells, CD4 + T cells, CD8 + central memory T cells (CD8 + TCM), monocytes, NK cells, and CD8 + effector memory T cells (TeM) (Fig. 5I). Comparison between periodontitis patients and healthy controls revealed marked differences in immune cell composition. Specifically, the proportions of NK cells and CD8 + TCM were significantly elevated in periodontitis patients, suggesting enhanced cytotoxic and memory T cell responses in disease conditions (Fig. 5J). To validate the translation of bulk transcriptomic microarrays findings at single-cell resolution, we analyzed the expression patterns of the three key diagnostic lactylation-related genes-EAF1, NEFL, and VIM-across annotated immune cell populations (Fig. 5K). The results revealed that VIM was broadly expressed in nearly all immune cell types, EAF1 was predominantly found in monocytes and CD8 + TeM, whereas NEFL expression was mainly restricted to CD4 + T cells. These findings not only confirm the robustness of our bulk transcriptomic analysis but also highlight the cell-type-specific expression of lactylation-related markers in peripheral immune cells of periodontitis patients. Together, these single-cell analyses underscore the intricate cellular heterogeneity and dynamic immune shifts in periodontitis, while solidifying EAF1, NEFL, and VIM as promising biomarkers with translational potential for the diagnosis and mechanistic dissection of periodontitis.

Single-cell transcriptomic profiling of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) in periodontitis and validation of key bulk-identified genes at single-cell resolution. (A, B) Violin plots showing quality control metrics for each identified cell type in healthy controls (A) and periodontitis patients (B), respectively. (C) Principal component analysis (PCA) plot of all single-cell samples, depicting the distribution of cells from healthy donors and periodontitis patients. (D) Elbow plot displaying the standard deviation of each principal component. (E) Uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) plot by cluster showing unsupervised clustering results for the integrated PBMC dataset. (F) UMAP plot by group illustrating the distribution of cells from healthy controls and periodontitis patients. (G) UMAP plot by sample, highlighting cells originating from each individual sample within the dataset. (H) Dot plot showing expression patterns of the top five marker genes for each cluster. (I) UMAP visualization of annotated cell types, demonstrating clusters corresponding to naive B cells, CD4 + T cells, CD8 + effector memory T cells (CD8 + Tem), CD8 + central memory T cells (CD8 + Tcm), monocytes, and natural killer (NK) cells. (J) Bar plot showing the proportion of each major immune cell type in healthy controls and periodontitis patients. (K) UMAP feature plots for the validation of three key lactylation-related genes (EAF1, NEFL, and VIM) identified by bulk RNA sequencing (RNA-seq), depicting their expression distribution across all PBMCs at single-cell resolution.

Single-cell GSEA enrichment and NK cell subpopulation characterization

To further elucidate the functional alterations of immune cells in periodontitis, we performed single-cell GSEA across distinct immune cell subsets. The analysis revealed that hallmark pathways such as interferon alpha response, complement activation, and interferon gamma response were significantly upregulated in NK cells and monocytes from periodontitis patients (Fig. 6A-C). These findings indicate a heightened antiviral and inflammatory state within these cell populations, consistent with the immune activation observed in bulk transcriptomic data. Given the marked increase in NK cell infiltration in periodontitis, we focused subsequent analyses on this population. NK cells were extracted from the single-cell dataset and subjected to reclustering, which identified seven transcriptionally distinct NK cell subclusters (Fig. 6D). Marker gene expression patterns for each cluster were determined (Fig. 6E, F), enabling functional annotation: cluster 0 and 1 were characterized as AES + NK cells, cluster 2 as MRTNR2L8 + NK, cluster 3 as HLR-DRB5 + NK, cluster 4 as CD8A + NK, and clusters 5 and 6 as AREG + NK cells (Fig. 6G). To investigate the developmental dynamics of these NK cell subpopulations, pseudotime trajectory analysis was performed. The results suggested that MRTNR2L8 + NK and HLR-DRB5 + NK cells represented the earliest differentiation states, whereas AES + NK cells corresponded to the terminally differentiated state (Fig. 6H, I). This trajectory highlights the functional plasticity and potential maturation pathways of NK cells in periodontitis. Finally, GSVA was used to compare immune functional pathway activation across NK cell subtypes. The results indicated that, compared to other NK subpopulations, MRTNR2L8 + NK cells exhibited markedly lower activation levels of multiple immune-related pathways (Fig. 6J). This suggests functional heterogeneity among NK cell subsets, with specific subpopulations potentially playing distinct roles in the immunopathology of periodontitis. Collectively, these single-cell analyses provide novel insights into the functional diversity and dynamic state transitions of NK cells in periodontitis, revealing complex immune dysregulation that may contribute to disease progression.

Single-cell gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) enrichment analysis and natural killer (NK) cell subpopulation characterization in periodontitis peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs). (A–C) Ridge plots illustrating the distribution of immune-related gene set enrichment analysis (irGSEA)-derived enrichment scores (area under the curve, AUC values) for three key Hallmark pathways-(A) interferon alpha response, (B) complement, and (C) interferon gamma response-across major PBMC cell types. (D) Uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) plot of NK cell subpopulations after reclustering, with each color representing a unique NK cell subcluster. (E) Dot plot highlighting the top five marker genes for each NK cell subcluster. (F) Violin plots showing the expression levels of representative marker genes across NK subclusters. (G) UMAP plot with annotated NK subclusters (AES + NK, MTRNR2L8 + NK, HLA-DRB5 + NK, CD8A + NK, AREG + NK), showing the transcriptional heterogeneity among NK cells. (H, I) Monocle pseudotime trajectory analysis of NK cells: (H) pseudotime states for NK cells, with each color denoting a different functional trajectory state; (I) cells colored according to calculated pseudotime value, highlighting dynamic transitions among subclusters. (J) Heatmap displaying gene set variation analysis (GSVA) scores for hallmark pathway signatures across the identified NK cell subclusters.

Discussion

In this study, we systematically characterized the expression patterns and functional significance of lactylation-related genes (LACRGs) in periodontitis by integrating microarray-based bulk transcriptomics, single-cell transcriptomics derived from PBMCs, immune cell infiltration profiling, machine learning-based biomarker selection, and IHC validation in clinical tissue samples. A central objective was to link systemic immune alterations, captured in peripheral blood, with local biomarker changes in diseased gingival tissues. Our findings offer novel insights into the epigenetic regulation of the immune microenvironment in periodontitis and establish a robust framework for the identification of clinically relevant diagnostic biomarkers in complex inflammatory diseases. A key highlight of our research is the identification of three diagnostic LACRGs—EAF1, NEFL, and VIM—which demonstrated strong discriminatory power between periodontitis and healthy controls across independent cohorts. These genes not only showed robust differential expression in bulk transcriptomic datasets, but their combined diagnostic score, derived through logistic regression, exhibited superior accuracy compared to individual markers, as confirmed by ROC analysis. This underscores the clinical potential of multi-gene signatures for early detection, risk stratification, and personalized intervention in periodontitis, a disease characterized by considerable heterogeneity and variable clinical outcomes.

Our data reinforce emerging evidence that protein lactylation, as a metabolic post-translational modification, plays a pivotal role in orchestrating immune responses in chronic inflammatory conditions13,31. Through unsupervised molecular subtyping using NMF, we identified distinct transcriptomic clusters that were closely associated with immune activation states. Notably, periodontitis subtypes with elevated LACRG expression were significantly enriched in pro-inflammatory pathways, including JAK-STAT signaling, chemokine production, interferon responses, and T cell-mediated immunity. These findings suggest that aberrant lactylation may drive chronic immune activation and disease persistence, aligning with the current understanding that metabolic and epigenetic reprogramming collectively shape the trajectory of inflammatory immune responses16. Our immune cell infiltration analyses further revealed pronounced increases in dendritic cells, B lymphocytes, CD8 + T cells, NK cells, and macrophages in periodontitis tissues, alongside a marked reduction in regulatory T cell populations. This shift reflects a transition from immune homeostasis toward a pro-inflammatory state, consistent with previous reports emphasizing the importance of immune balance in periodontal health and disease32. Moreover, pairwise correlation and pathway activation analyses suggested that LACRG expression is intimately linked to the interplay between innate and adaptive immune compartments, underscoring the potential role of lactylation in modulating the inflammatory milieu of periodontitis33.

Linking systemic immune alterations to local biomarker changes was an explicit focus of our integrative design. PBMC scRNA-seq revealed distinct shifts in the composition and activation states of peripheral immune cells in patients, including increased frequencies of NK cells and CD8 + central memory T cells. Functionally, single-cell GSEA/GSVA uncovered discrete NK subpopulations with divergent pathway activities and differentiation trajectories. These systemic alterations paralleled the ssGSEA-inferred increases in NK and CD8 + signatures in gingival tissues, suggesting cross-compartment concordance in immune activation. At the gene level, the diagnostic LACRGs exhibited cell type–specific expression in PBMCs—VIM broadly across immune lineages, EAF1 enriched in monocytes and effector T cells, and NEFL predominant in CD4 + T cells—providing a mechanistic context for the tissue-level IHC observations. These findings highlight both the robustness of our biomarker discovery approach and the translational potential of these genes for future diagnostic and therapeutic applications22,34,35. Together, the gingival microarrays, PBMC scRNA-seq, and gingival IHC triangulate a coherent narrative: systemic immune remodeling in periodontitis is mirrored by and likely contributes to local biomarker changes within the periodontal microenvironment. Importantly, our single-cell analyses not only validate the relevance of the diagnostic signature in the peripheral immune compartment but also deepen mechanistic understanding. By delineating NK cell heterogeneity and transcriptional programs associated with activation and suppression, these findings nominate candidate pathways and cell states that may interface with lactylation-dependent regulation and influence disease persistence. This framework offers testable hypotheses for how metabolic–epigenetic cues integrate with immune cell dynamics to sustain chronic inflammation and tissue damage.

This study draws strength from two large gingival tissue cohorts (GSE16134 and GSE10334) profiled on a consistent microarray platform with harmonized diagnostic criteria, enabling a robust discovery–validation design that minimizes technical and clinical heterogeneity. To complement tissue-level findings with cellular resolution, we integrated GSE244515, a PBMC scRNA-seq dataset that captures systemic immune variation linked to periodontitis. While this cross-compartment integration strengthens internal validity and supports the linkage between systemic immune alterations and local biomarkers, several caveats warrant consideration. While this integrated approach strengthens internal validity, it also introduces certain limitations. These include potential selection bias and a lack of detailed clinical annotations regarding disease stage, grade, and subtype (chronic/aggressive) in the analyzed datasets. The absence of gingival single-cell data further constrains tissue-specific interpretation. Future studies utilizing cohorts with detailed clinical annotations are warranted to validate and refine our signatures for precise staging and risk stratification. Furthermore, incorporation of single-cell or spatial transcriptomic data from gingival tissues could provide more tissue-specific insights into the cellular dynamics of lactylation in the periodontal microenvironment.

Overall, our study bridges a critical gap in periodontitis research by linking metabolic-epigenetic regulation to immune cell heterogeneity and chronic tissue inflammation. These insights are consistent with the growing recognition of immunometabolism and histone modification as central regulators of host-microbe interactions, tissue repair, and the outcomes of chronic inflammatory diseases36,37. However, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, although multiple public datasets were leveraged, the single-cell sample size was modest and restricted to PBMCs, which may not fully capture tissue-resident immune niches within the periodontium. Meanwhile, although IHC has verified expression of EAF1, NEFL, and VIM, orthogonal spatial validation using multiplex IHC to resolve their subcellular distribution and lineage‑marker co‑expression in the gingiva is still needed to strengthen the single‑cell results. Second, both bulk transcriptomic microarrays and scRNA-seq dataset were based on cross-sectional data; longitudinal studies are needed to delineate dynamic changes in lactylation and immune phenotypes throughout disease progression and in response to therapy. Third, all bioinformatic analyses inherently depend on the accuracy of genome annotation, deconvolution algorithms, and cell marker definitions, which may introduce bias. Finally, as periodontitis is a multifactorial disease involving environmental, microbial, genetic, and systemic influences, our study focused primarily on the immune-epigenetic axis, and future integration with additional omics layers (such as proteomics, microbiomics, and metabolomics) will be essential for a more comprehensive understanding.

Conclusions

In summary, our integrative study provides compelling evidence that lactylation-related gene dysregulation is closely associated with immune cell remodeling and pro-inflammatory activation in periodontitis. We demonstrate that LACRG-based molecular signatures have significant diagnostic and stratification value, and that single-cell approaches can unravel the heterogeneity of immune cell states and their epigenetic regulation in disease. These findings advance current understanding of the interplay between metabolism, epigenetics, and immunity in periodontal pathology and identify robust candidate biomarkers for early detection and targeted therapy. Future research extending these findings through experimental validation and multi-omics integration will be instrumental in translating lactylation and immune-centric strategies into clinical practice for the management of periodontitis and related chronic inflammatory disorders.

Data availability

The data used in this study were obtained from the GEO (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/, GSE16134, GSE10334, and GSE244515).

Abbreviations

- AES:

-

Amino-terminal enhancer of split

- ARID3A:

-

AT-Rich Interaction Domain 3 A

- AUC:

-

Area Under the Curve

- CALML5:

-

Calmodulin-Like 5

- CSRP2:

-

Cysteine and Glycine Rich Protein 2

- DCs:

-

Dendritic Cells

- DE-LACAGs:

-

Differentially Expressed Lactylation-Associated Genes

- DEGs:

-

Differentially Expressed Genes

- EAF1:

-

ELL-Associated Factor 1

- FDR:

-

False Discovery Rate

- FC:

-

Fold Change

- GEO:

-

Gene Expression Omnibus

- GO:

-

Gene Ontology

- GSVA:

-

Gene Set Variation Analysis

- GSEA:

-

Gene Set Enrichment Analysis

- IHC:

-

Immunohistochemistry

- KEGG:

-

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- LACAGs:

-

Lactylation-Associated Genes

- LACRGs:

-

Lactylation-Related Genes

- LASSO:

-

Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator

- LCP1:

-

Lymphocyte Cytosolic Protein 1

- MNDA:

-

Myeloid Cell Nuclear Differentiation Antigen

- NEFL:

-

Neurofilament Light Chain

- NMF:

-

Non-negative Matrix Factorization

- NK:

-

Natural Killer cell

- PBMCs:

-

Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells

- PCA:

-

Principal Component Analysis

- PTMs:

-

Post-Translational Modifications

- RF:

-

Random Forest

- ROC:

-

Receiver Operating Characteristic

- RNA-seq:

-

RNA Sequencing

- scRNA-seq:

-

Single-Cell RNA Sequencing

- ssGSEA:

-

Single-Sample Gene Set Enrichment Analysis

- TeM:

-

Effector Memory T Cell

- TCM:

-

Central Memory T Cell

- Tregs:

-

Regulatory T Cells

- UMAP:

-

Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection

- VIM:

-

Vimentin

- XGBoost:

-

Extreme Gradient Boosting

References

Eke, P. I. et al. Periodontitis in US adults: National health and nutrition examination survey 2009–2014. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 149 (7), 576–88e6 (2018).

Hajishengallis, G. Periodontitis: from microbial immune subversion to systemic inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 15 (1), 30–44 (2015).

Baima, G. et al. Shared Microbiological and immunological patterns in periodontitis and IBD: A scoping review. Oral Dis. 28 (4), 1029–1041 (2022).

He, J., Liu, Y., Xu, H., Wei, X. & Chen, M. Insights into the variations in microbial community structure during the development of periodontitis and its pathogenesis. Clin. Oral Investig. 28 (12), 675 (2024).

Cai, Z., Lin, S., Hu, S. & Zhao, L. Structure and function of oral microbial community in periodontitis based on integrated data. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 11, 663756 (2021).

Zeltz, C. & Gullberg, D. Post-translational modifications of integrin ligands as pathogenic mechanisms in disease. Matrix Biol. 40, 5–9 (2014).

He, M., Zhou, X. & Wang, X. Glycosylation: mechanisms, biological functions and clinical implications. Signal. Transduct. Target. Ther. 9 (1), 194 (2024).

Gaffney, D. O. et al. Non-enzymatic lysine lactoylation of glycolytic enzymes. Cell. Chem. Biol. 27 (2), 206– (2020). – 13.e6.

Van den Bossche, J. No (innate immune) training without lactate. Mol. Cell. 85 (11), 2065–2067 (2025).

Ziogas, A. et al. Long-term histone lactylation connects metabolic and epigenetic rewiring in innate immune memory. Cell 188 (11), 2992–3012e16 (2025).

Zhang, C. et al. H3K18 lactylation potentiates immune escape of Non-Small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 84 (21), 3589–3601 (2024).

Xiong, J. et al. Lactylation-driven METTL3-mediated RNA m(6)A modification promotes immunosuppression of tumor-infiltrating myeloid cells. Mol. Cell. 82 (9), 1660–77e10 (2022).

Zhang, D. et al. Metabolic regulation of gene expression by histone lactylation. Nature 574 (7779), 575–580 (2019).

Chen, L. et al. Methyl-CpG-binding 2 K271 lactylation-mediated M2 macrophage polarization inhibits atherosclerosis. Theranostics 14 (11), 4256–4277 (2024).

Newman, D. M., Voss, A. K., Thomas, T. & Allan, R. S. Essential role for the histone acetyltransferase KAT7 in T cell development, fitness, and survival. J. Leukoc. Biol. 101 (4), 887–892 (2017).

Ye, L., Jiang, Y. & Zhang, M. Crosstalk between glucose metabolism, lactate production and immune response modulation. Cytokine Growth Factor. Rev. 68, 81–92 (2022).

Papalexi, E. & Satija, R. Single-cell RNA sequencing to explore immune cell heterogeneity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 18 (1), 35–45 (2018).

Mitsialis, V. et al. Single-Cell analyses of colon and blood reveal distinct immune cell signatures of ulcerative colitis and crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology 159 (2), 591–608e10 (2020).

Papapanou, P. N. et al. Subgingival bacterial colonization profiles correlate with gingival tissue gene expression. BMC Microbiol. 9, 221 (2009).

Demmer, R. T. et al. Transcriptomes in healthy and diseased gingival tissues. J. Periodontol. 79 (11), 2112–2124 (2008).

Lee, H. et al. Immunological link between periodontitis and type 2 diabetes Deciphered by single-cell RNA analysis. Clin. Transl Med. 13 (12), e1503 (2023).

Cheng, Z. et al. Lactylation-Related gene signature effectively predicts prognosis and treatment responsiveness in hepatocellular carcinoma. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) ;16(5). (2023).

Kanehisa, M., Sato, Y., Kawashima, M., Furumichi, M. & Tanabe, M. KEGG as a reference resource for gene and protein annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 44 (D1), D457–D462 (2016).

Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28 (1), 27–30 (2000).

Wu, T. et al. ClusterProfiler 4.0: A universal enrichment tool for interpreting omics data. Innov. ;2(3). (2021).

Gaujoux, R. & Seoighe, C. A flexible R package for nonnegative matrix factorization. BMC Bioinform. 11 (1), 367 (2010).

Hänzelmann, S., Castelo, R. & Guinney, J. GSVA: gene set variation analysis for microarray and RNA-Seq data. BMC Bioinform. 14 (1), 7 (2013).

Aran, D. et al. Reference-based analysis of lung single-cell sequencing reveals a transitional profibrotic macrophage. Nat. Immunol. 20 (2), 163–172 (2019).

Trapnell, C. et al. The dynamics and regulators of cell fate decisions are revealed by pseudotemporal ordering of single cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 32 (4), 381–386 (2014).

Papapanou, P. N. et al. Periodontitis: consensus report of workgroup 2 of the 2017 world workshop on the classification of periodontal and Peri-Implant diseases and conditions. J. Periodontol. 89 (Suppl 1), S173–s82 (2018).

Chen, L. et al. Lactate-Lactylation hands between metabolic reprogramming and immunosuppression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 19 (2022).

Slots, J. Periodontitis: facts, fallacies and the future. Periodontol 2000. 75 (1), 7–23 (2017).

Wu, Y. et al. Proanthocyanidins ameliorate LPS-Inhibited osteogenesis of PDLSCs by restoring lysine lactylation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. ;25(5). (2024).

Wu, J. et al. Immunological profile of lactylation-related genes in crohn’s disease: a comprehensive analysis based on bulk and single-cell RNA sequencing data. J. Transl Med. 22 (1), 300 (2024).

Zhu, M. et al. Predicting lymphoma prognosis using machine learning-based genes associated with lactylation. Transl Oncol. 49, 102102 (2024).

Pan, X., Zhu, Q., Pan, L. L. & Sun, J. Macrophage immunometabolism in inflammatory bowel diseases: from pathogenesis to therapy. Pharmacol. Ther. 238, 108176 (2022).

Wang, J., Wang, Z., Wang, Q., Li, X. & Guo, Y. Ubiquitous protein lactylation in health and diseases. Cell. Mol. Biol. Lett. 29 (1), 23 (2024).

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception/design: XZ and YZ; Collection and/or assembly of data: YZ, XZ, LW, TW, YG; Data analysis and interpretation: YZ, MC, YB, and SJ; Manuscript writing: YZ; Final approval of manuscript: YZ and YZ. All authors read and approved the final manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the research in ensuring that the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work is appropriately investigated and resolved.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The research was approved by the Ethics Committee of Northwest University First Hospital (Approval No.: 2024KY-04). All participants provided written informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu, Y., Zhang, X., Wei, L. et al. Lactylation-related gene signatures define immune heterogeneity and provide diagnostic biomarkers for periodontitis. Sci Rep 15, 45516 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30213-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30213-z