Abstract

Although plant-derived nitrates and nitrites are increasingly recognized for their potential metabolic advantages, current research presents mixed outcomes. This study explores the relationship between vegetable-sourced nitrate and nitrite consumption and key metabolic indicators in overweight and obese Iraqi adults. A total of 338 individuals participated in a cross-sectional analysis, completing a validated food frequency questionnaire to quantify their intake of nitrates and nitrites from vegetables. Blood pressure readings were obtained using standard sphygmomanometer, and biochemical markers—including fasting glucose, lipid profile, and insulin—were assessed via enzymatic assays. Participants with the highest intake of vegetable nitrates demonstrated significantly lower systolic blood pressure compared to those with the lowest intake (P < 0.05). Likewise, elevated dietary nitrite consumption was linked to lower fasting glucose and total cholesterol levels, alongside increased HDL cholesterol (P < 0.05), across both crude and adjusted statistical models. Elevated intake of nitrates and nitrites from vegetables appears to be associated with favorable cardiovascular and metabolic health markers in overweight and obese individuals. These results highlight the potential of vegetable-based nitrate and nitrite consumption as a dietary strategy for improving cardio-metabolic outcomes, meriting further investigation through longitudinal studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Inorganic nitrates and nitrites are naturally occurring compounds found in plant-based foods, with vegetables being the primary dietary source of exogenous nitrate intake1. Approximately 80–95% of dietary nitrates come from green leafy vegetables such as lettuce, spinach, cabbage, beetroot, radishes, and rocket2,3. The health benefits of dietary nitrates and nitrites have been demonstrated in various studies. Nitrates are recognized as a significant precursor to nitric oxide (NO), which exerts several protective effects against chronic diseases through the nitrate-nitrite-NO pathway4,5. Dietary nitrate enhances NO levels in the body via the entero-salivary nitrate-nitrite-NO pathway. Nitric oxide, originating from the endothelial system, plays a cardioprotective role by improving vascular function, reducing arterial stiffness, regulating blood pressure, and promoting vasodilation and overall vessel health6,7.

Several observational and interventional studies have investigated the potential health benefits of nitrate. In a randomized study, it was found that an acute injection of sodium nitroprusside, a nitric oxide donor, significantly increased glucose uptake independently of plasma insulin levels8. A short-term intervention (3 days) using high-dose nitrate-rich beetroot juice resulted in reduced blood pressure in a crossover trial involving healthy older adults9. Additional research in experimental models has demonstrated several health benefits, including anti-obesity effects, prevention of visceral fat accumulation, lowered serum triglycerides in eNOS-deficient mice, improved glucose tolerance10 and reduced weight gain11. In the study by Golzarand M et al.12, high intake of nitrate-rich vegetables was linked to lower odds of developing hypertension in a longitudinal study. Other studies have also shown reduced blood pressure with higher nitrate consumption13. However, some inconsistent findings exist, with reports suggesting that elevated plasma nitrate levels may be associated with increased arterial pressure14 as well as higher rates of hypertension and diabetes15.

The World Health Organization (WHO) sets the upper limits for nitrate and nitrite at 50 mg/L and 3 mg/L, respectively, with their combined total not exceeding a ratio of 116. Research investigating the health impacts of nitrates and nitrites varies widely in study design, settings, populations, and disease conditions. This variability warrants cautious interpretation. Additionally, many of these studies are conducted in vitro or on animal models, making it difficult to directly generalize these findings to humans. Given the recent evidence suggesting potential cardiovascular benefits of nitrates and nitrites, along with conflicting results in the field, there is a growing need for more human-based research, particularly focusing on identifying the primary dietary sources of nitrates. Only a few studies have explored the link between nitrate/nitrite intake from dietary sources and disease outcomes. For instance, one follow-up study reported an inverse relationship between the consumption of nitrate-rich vegetables and the risk of hypertension12. Conversely, a study by Mousavi M. et al.17, found no association between dietary nitrate and nitrite intake and general or abdominal obesity phenotypes. Moreover, the nitrate and nitrite content in vegetables varies depending on environmental factors such as soil type, cultivation practices, harvest timing, and geographic conditions, meaning that findings from one region may not be applicable to others18.

Nitrate has historically been viewed with caution due to its potential to form carcinogenic N-nitroso compounds. However, recent evidence reveals a paradox: dietary nitrate—particularly from vegetables—is associated with beneficial cardiometabolic effects via the nitrate–nitrite–nitric oxide pathway19. In contrast, nitrate exposure from non-dietary sources such as contaminated drinking water may carry health risks, including elevated cancer and metabolic disorder incidence20. Notably, higher vegetable-based nitrate intake has been linked to lower incidence and mortality from cardiovascular diseases21. In contrast, nitrate from water or animal sources does not appear to confer these protective effects and may be associated with adverse outcomes22.

Few studies have examined the relationship between dietary nitrate and nitrite intake and metabolic parameters, and none have been conducted in Iraq. Therefore, this study aimed to explore the association between nitrate and nitrite intake from commonly consumed vegetables and metabolic profiles. Specifically, we investigated the associations between dietary nitrate and nitrite intake and serum glycemic markers, lipid levels, and blood pressure in a population-based study in Iraq.

Method & materials

Study population

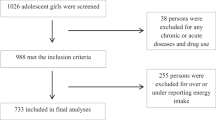

This cross-sectional study involved 338 individuals aged 20 to 50 years, all of whom were overweight or obese. Overweight and obesity were defined according to the World Health Organization (WHO) criteria. Overweight was defined as body mass index (BMI) between 25.0 and 29.9 kg/m2, and obesity as BMI ≥ 30.0 kg/m2. Participants were randomly selected using written invitations and pamphlets distributed in local community centers and fitness clubs. This approach ensured a diverse representation from both urban and suburban populations. To maintain sample consistency, individuals were excluded based on specific criteria. These included: women who were pregnant, breastfeeding, or postmenopausal; individuals with a history of gastric bypass or other weight-loss surgeries; those diagnosed with cancer, liver or kidney diseases, cardiovascular conditions, or diabetes mellitus; and individuals taking medications or dietary supplements that could influence body weight, metabolism, or serum lipid levels. The study flowchart is represented in (Fig. 1).

Anthropometric and physical activity measurements

Body weight and height were measured using a Seca scale and stadiometer (Seca Co., Hamburg, Germany) with accuracies of 0.1 kg and 0.5 cm, respectively. Participants wore light clothing and removed their shoes during measurements. BMI was calculated as weight (kg) divided by height squared (m2). Waist circumference (WC) was measured at the midpoint between the lower edge of the last palpable rib and the top of the iliac crest using a non-stretchable tape. Hip circumference was measured at the widest part of the buttocks, and the waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) was calculated by dividing WC by hip circumference. All anthropometric measurements were performed in triplicate, and the averages were used for analysis. Physical activity (PA) was assessed using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) and expressed as metabolic equivalent of task (MET) scores. The validity and reliability of this questionnaire have been previously confirmed23.

Dietary assessments and dietary nitrate/ nitrite intake calculation

A valid and reliable semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) was used to assess dietary intake. This self-administered questionnaire included 105 food items and was originally developed for Iraqi adults24. Its validity was evaluated by comparison with four-day weighed food records from the same population, demonstrating both accuracy and reproducibility. The FFQ was culturally adapted to reflect local dietary habits, incorporating commonly consumed foods, typical portion sizes, and preparation methods in Iraq. Correlation coefficients between the FFQ and the weighed records were 0.829 for energy, 0.583 for fat, 0.323 for carbohydrate, and 0.547 for protein. The questionnaire also showed acceptable internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.70.

Participants were instructed to follow the portion sizes, cooking yields, and dietary amount recommendations outlined in the Iraq household manual when documenting all foods and beverages consumed. The intake of each food item was recorded in grams. The estimation of dietary nitrates and nitrites from vegetables followed the method previously established by Roshna Akram Ali et al.18. In summary, the nitrate content of various common vegetables was determined using a spectrophotometer. These vegetables included: green leafy greens (including Swiss chard, garden cress, leek, celery); fruiting vegetables (including Aubergine, Pepper, cucumber, tomato, squash), herbs and tubers (including Mint, Tarragon, green onions, radish, turnip). Measurements were performed using a UV/VIS double beam spectrophotometer at a wavelength of 538 nm as described previously18. The total nitrate and nitrite intake was calculated based on all nitrate-containing vegetables consumed.

Measurement of blood biomarkers and blood pressure assessments

A trained physician measured the participants’ systolic and diastolic blood pressure using a standard mercury sphygmomanometer on the right arm. Measurements were taken after participants had rested in a seated position for 10–15 min. The average of the two readings was recorded for each individual. Each participant provided a 10 ml venous blood sample for analysis. Serum lipid levels and fasting blood glucose were determined using a Cobas® 6000 auto-analyzer from Roche Diagnostics. Serum insulin concentrations were assessed using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (Mercodia Insulin ELISA Kit). The homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) was calculated using the formula: fasting insulin (IU/mL) × fasting glucose (mmol/L) / 22.5. The quantitative insulin sensitivity check index (QUICKI) was calculated as: 1 / [log (fasting insulin (U/mL)) + log (fasting glucose (mmol/L))].

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS software (version 21.0; SPSS Inc, Chicago IL). The normality of data was checked using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Discrete variables were presented as frequency and percentage, while continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Differences in discrete and continuous variables across groups were assessed using Chi-square tests and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), respectively. Comparisons between tertiles were performed using Tukey’s post-hoc test. To adjust for confounders, two analyses were performed. First, analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used to estimate differences between continuous variables while adjusting for confounders (e.g., age, gender, BMI, physical activity, and dietary energy intake). Second, multinomial logistic regression was conducted to examine potential associations between cardio-metabolic risk factors and dietary vegetable nitrate and nitrite intake. Three models were applied: Model I, crude; Model II, adjusted for age and sex; and Model III, adjusted for age, BMI, sex, physical activity, and dietary energy intake. The sample size was determined based on previous studies evaluating dietary nitrate and nitrite intake in relation to cardiometabolic markers among overweight and obese adults25,26,27. Considering an expected moderate effect size (Cohen’s f = 0.25), a statistical power of 80%, and a significance level of 0.05, the minimum required sample size was calculated to be approximately 90 participants per tertile group (270 in total). To account for possible non-response and missing data (estimated at 20%), the required sample size was increased using the standard attrition-adjustment formula to 338 participants.

Results

The general characteristics of participants across nitrate and nitrite intake tertiles are shown in (Table 1). No significant differences were observed in demographic or anthropometric variables. Higher dietary nitrate intake was associated with significantly lower systolic (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) in the highest tertile compared to lower tertiles, in both crude and adjusted models (P < 0.05). Similarly, higher dietary nitrite intake was linked to lower fasting blood sugar (FBS) and higher serum insulin and HDL levels in the highest tertile. Total cholesterol was lower in the highest nitrite tertile in crude and age- and sex-adjusted models (P = 0.004 and P = 0.01, respectively). Table 2 summarizes the nitrate and nitrite content of vegetables. Green leafy vegetables contributed most nitrate, followed by fruiting vegetables, while herbs and tubers were the primary sources of nitrite. Table 3 presents dietary intake of energy, macronutrients, and food groups by tertiles. Protein intake differed significantly across nitrite tertiles (P = 0.01), whereas other macronutrients did not. Intake of fruits, vegetables, grains and cereals, dairy, meat/fish/poultry, legumes and nuts, and sweets/snacks increased across higher tertiles, except for fats and oils in nitrite tertiles (P = 0.121). Table 4 displays odds ratios for biochemical markers across tertiles. Participants in the highest nitrate tertile had greater odds of lower SBP and DBP across all models (P < 0.05). For nitrite, the highest tertile was associated with lower FBS, higher insulin, and elevated HDL compared to the lowest tertile. Overall, these findings suggest that higher vegetable-derived nitrate and nitrite intake is linked to improved cardio-metabolic risk factors in overweight and obese individuals.

Discussion

In this study, higher dietary nitrate intake from vegetables was associated with lower blood pressure, while greater vegetable-derived nitrite consumption was linked to improved glycemic and lipid profiles, including lower FBS, reduced insulin resistance, higher insulin, lower TC, and higher HDL levels. Endogenous nitrate and nitrite originate mainly from two sources: the oxidation of NO via the L-arginine–eNOS pathway, which contributes about 70% of plasma nitrite28,29 and dietary intake, which serves as the major source. Average dietary nitrite and nitrate intakes range from 0–20 mg/day and 53–300 mg/day, respectively, with 80–95% of nitrate derived from plant sources, while most nitrite comes from food additives in processed meats and baked goods30,31. Additionally, nitrate reduction by oral and gut bacteria or nitrate reductase enzymes contributes to systemic nitrite levels32,33. Additionally, nitrate reduction by oral and gut bacteria or nitrate reductase enzymes contributes to systemic nitrite levels12 Consistent with our findings, previous research reported an inverse association between nitrate-rich vegetable intake and hypertension risk (OR = 0.63; 95% CI: 0.41–0.98; p for trend = 0.05) 4.

Dietary nitrite and its precursor, nitrate, are important for cardiovascular health due to their role in enhancing NO bioavailability. As nitrate is reduced to nitrite and then to NO, both compounds act synergistically in improving vascular function and lipid metabolism32,33,34. In our study, higher dietary nitrite intake was associated with lower TC and higher HDL-C levels. Similarly, previous studies have shown beneficial effects of nitrate and nitrite on lipid profiles, including improved serum lipids in diabetic rats35 In our study, higher dietary nitrite intake was associated with lower TC and higher HDL-C levels. Similarly, previous studies have shown beneficial effects of nitrate and nitrite on lipid profiles, including improved serum lipids in diabetic rats36.

Our findings highlight the importance of dietary diversity—especially a greater variety of vegetable subtypes—in determining nitrate exposure. As shown in Table 2, green leafy and fruiting vegetables were the main contributors to nitrate intake in the highest tertile. A diverse vegetable intake may therefore enhance total nitrate exposure and its cardio-metabolic benefits. Consistent with our results, a large Danish cohort reported that moderate vegetable nitrate intake (~ 60 mg/day) was associated with a 15% lower risk of cardiovascular disease and its subtypes25 and a systematic review confirmed similar inverse associations21. and a systematic review confirmed similar inverse associations37.

The health benefits of dietary nitrite also include a reductions in blood glucose levels, particularly among individuals with the highest intake, which may be linked to the anti-diabetic effects of nitrate and nitrite. Considerable evidence supports the positive impact of these compounds on glycemic control in both animal and human studies. For instance, research by Mattias C et al.10, demonstrated that dietary inorganic nitrate supplementation improved glucose tolerance and alleviated symptoms of metabolic syndrome in eNOS-deficient mice. The underlying mechanism by which dietary nitrate and nitrite may protect against type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) involves the restoration of the disrupted NO pathway, which is often compromised in diabetic patients due to chronic hyperglycemia, oxidative stress, increased NF-κB activity, accumulation of advanced glycation end-products (AGEs), elevated levels of asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA), and decreased NOS activity, all leading to impaired insulin secretion38. Other potential mechanisms identified in experimental and human studies include enhanced blood flow to pancreatic islets and increased plasma insulin levels38, as well as improved insulin signaling through the restoration of NO-dependent nitrosation of glucose transporter 4 (GLUT-4), which is directly influenced by nitrite10. Likewise, we observed lower HOMA-IR and fasting blood sugar levels in individuals with the highest dietary nitrite intake among the overweight and obese population. Some of these mechanistic pathways are depicted in (Fig. 2).

The health benefits of dietary nitrite also include a reductions in blood glucose levels, particularly among individuals with the highest intake, which may be linked to the anti-diabetic effects of nitrate and nitrite. Considerable evidence supports the positive impact of these compounds on glycemic control in both animal and human studies. For instance, research by Mattias C et al.10, demonstrated that dietary inorganic nitrate supplementation improved glucose tolerance and alleviated symptoms of metabolic syndrome in eNOS-deficient mice. The underlying mechanism by which dietary nitrate and nitrite may protect against T2DM involves the restoration of the disrupted NO pathway, which is often compromised in diabetic patients due to chronic hyperglycemia, oxidative stress, increased NF-κB activity, accumulation of AGEs, elevated levels of asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA), and decreased NOS activity, all leading to impaired insulin secretion38. Other potential mechanisms identified in experimental and human studies include enhanced blood flow to pancreatic islets and increased plasma insulin levels38, as well as improved insulin signaling through the restoration of NO-dependent nitrosation of glucose transporter 4 (GLUT-4), which is directly influenced by nitrite10. Likewise, we observed lower HOMA-IR and fasting blood sugar levels in individuals with the highest dietary nitrite intake among the overweight and obese population. Some of these mechanistic pathways are depicted in (Fig. 2).

The health benefits of dietary nitrite also include improved glycemic control, particularly among individuals with higher intake. Consistent with our findings, Mattias C et al.10, reported that inorganic nitrate supplementation improved glucose tolerance and alleviated metabolic syndrome in eNOS-deficient mice. These effects are mainly mediated through the restoration of the disrupted NO pathway, commonly impaired in diabetes due to oxidative stress, inflammation, AGEs accumulation, and reduced NOS activity, all of which impair insulin secretion38. Additional mechanisms include enhanced pancreatic blood flow, increased plasma insulin levels38, Additional mechanisms include enhanced pancreatic blood flow, increased plasma insulin levels10. Similarly, in our study, higher dietary nitrite intake was associated with lower fasting glucose and HOMA-IR values among overweight and obese participants.

This study has several strengths and limitations. It is the first to investigate the potential effects of dietary nitrate and nitrite derived from vegetables on metabolic features among overweight and obese individuals. A validated FFQ was employed, and the estimation of dietary nitrate and nitrite intake was based on a locally conducted Iraqi study that precisely quantified these compounds in commonly consumed vegetables18, Therefore, the results are directly applicable to the overweight and obese Iraqi population. In the present study, the intake of vegetable-derived nitrate and nitrite was estimated using a validated food frequency questionnaire, in which the consumption of each food item was recorded in grams. To enhance accuracy of estimation, the nitrate and nitrite content of vegetables was derived from locally analyzed data based on the method reported by Roshna Akram Ali et al.3,18, where the nitrate content of commonly consumed vegetables was quantified using a UV/VIS double beam spectrophotometer which is based on the Griess reaction—a well-established, internationally recognized colorimetric method for nitrate and nitrite analysis in food and biological matrices. This procedure complies with official standards, including ISO 6635:198439 and the AOAC Official Method 973.3140.

Assessment of multiple cardiometabolic markers provides a comprehensive evaluation of the relationship between dietary nitrate and health outcomes. Also, adjustment for key potential confounders strengthens the validity of the observed associations. However, the study has some limitations; first, the cross-sectional design prevents the establishment of causal relationships between dietary nitrate intake and cardiometabolic parameters. Second, although the FFQ used was validated, self-reported dietary intake remains prone to recall bias and measurement errors and third, the study population was restricted to adults from a specific geographical region, which may limit the generalizability of findings to other populations. Third, nitrate and nitrite content can differ substantially depending on cooking methods (e.g., boiling, steaming, frying) and preparation techniques, which may alter bioavailability. Finally, we did not assess other potentially beneficial nutrients found in vegetables, such as potassium, polyphenols, and carotenoids, which may also contribute to favorable effects on blood pressure and glucose homeostasis.

This study adds new evidence by being the first to examine the relationship between vegetable-derived nitrate and nitrite intake and metabolic markers in overweight and obese individuals. Our findings highlight the importance of consuming diverse, nitrate-rich vegetables such as green leafy and fruiting types. These results provide region-specific data relevant to Iraq and similar Middle Eastern populations, where obesity and metabolic disorders are highly prevalent. Integrating these findings into national dietary guidelines could support strategies to reduce the burden of non-communicable diseases41,42,43,44,45.

Although direct measurement of the nitrate and nitrite content in each participant’s actual food intake would provide higher precision, this approach is rarely feasible in large-scale epidemiological studies; using a validated FFQ together with region-specific food composition data represents an accepted and practical method34,35. Importantly, efforts have been made to develop and calibrate dietary nitrate and nitrite databases for use with FFQs in large cohorts, which supports the validity of our approach. In particular, Inoue-Choi et al. described the development of a nitrate–nitrite composition database for the NCI Diet History Questionnaire and calibrated FFQ-based estimates against two 24 h recalls in the NIH–AARP Diet and Health Study, reporting moderate correlations and attenuation factors—evidence that FFQ estimates can reasonably reflect habitual nitrate and nitrite intakes in large epidemiologic studies46. Additionally, larger reference compilations of vegetable nitrate content have been assembled to improve quantification across diverse vegetables, further supporting the use of literature-based composition values when direct chemical analysis of every consumed dish is not feasible47.

In conclusion, higher intake of vegetable-derived nitrates and nitrites was linked to better cardio-metabolic profiles, including lower blood pressure, fasting glucose, and improved lipid levels in overweight and obese adults. Further prospective and interventional studies are needed to confirm causality and elucidate underlying mechanisms across diverse populations.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during this study are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical concerns. However, they can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Bahadoran, Z. et al. Nitrate and nitrite content of vegetables, fruits, grains, legumes, dairy products, meats and processed meats. J. Food Compos. Anal. 51, 93–105 (2016).

Hord, N. G., Tang, Y. & Bryan, N. S. Food sources of nitrates and nitrites: the physiologic context for potential health benefits. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 90 (1), 1–10 (2009).

Reinik, M., Tamme, T. & Roasto, M. Naturally occurring nitrates and nitrites in foods. Bioactive Compd. Foods 10, 9781444302288 (2008).

Gilchrist, M. et al. Effect of dietary nitrate on blood pressure, endothelial function, and insulin sensitivity in type 2 diabetes. Free Radical Biol. Med. 60, 89–97 (2013).

Larsen, F. J. et al. Dietary nitrate reduces resting metabolic rate: a randomized, crossover study in humans. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 99 (4), 843–850 (2014).

Bondonno, C. P. et al. Short-term effects of nitrate-rich green leafy vegetables on blood pressure and arterial stiffness in individuals with high-normal blood pressure. Free Radical Biol. Med. 77, 353–362 (2014).

Habermeyer, M. et al. Nitrate and nitrite in the diet: how to assess their benefit and risk for human health. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 59 (1), 106–128 (2015).

Henstridge, D. et al. Effects of the nitric oxide donor, sodium nitroprusside, on resting leg glucose uptake in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 48, 2602–2608 (2005).

Kelly, J. et al. Effects of short-term dietary nitrate supplementation on blood pressure, O2 uptake kinetics, and muscle and cognitive function in older adults. Am. J. Physiol. Regulat. Integr. Comparat. Physiol. 304 (2), R73–R83 (2013).

Carlström, M. et al. Dietary inorganic nitrate reverses features of metabolic syndrome in endothelial nitric oxide synthase-deficient mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 107 (41), 17716–17720 (2010).

El-Wakf, A. M., Hassan, H. A., El-said, F. G. & El-Said, A. Hypothyroidism in male rats of different ages exposed to nitrate polluted drinking water. Res. J. Med. Med. Sci. 4 (2), 160–164 (2009).

Golzarand, M., Bahadoran, Z., Mirmiran, P., Zadeh-Vakili, A. & Azizi, F. Consumption of nitrate-containing vegetables is inversely associated with hypertension in adults: a prospective investigation from the Tehran lipid and glucose study. J. Nephrol. 29, 377–384 (2016).

Larsen, F. J., Ekblom, B., Sahlin, K., Lundberg, J. O. & Weitzberg, E. Effects of dietary nitrate on blood pressure in healthy volunteers. N. Engl. J. Med. 355 (26), 2792–2793 (2006).

Zeballos, G. A. et al. Pharmacodynamics of plasma nitrate/nitrite as an indication of nitric oxide formation in conscious dogs. Circulation 91 (12), 2982–2988 (1995).

Powlson, D. S. et al. When does nitrate become a risk for humans?. J. Environ. Qual. 37 (2), 291–295 (2008).

Organization, W. H. Guidelines for drinking-water quality: second addendum Vol. 1 (World Health Organization, 2008).

Mousavi, M., Bahadoran, Z., Saeedirad, Z., Mirmiran, P. & Azizi, F. The relation between dietary nitrate and nitrite intake and obesity phenotypes: Tehran lipid and glucose study. J. Mazandaran Univ. Med. Sci. 29 (181), 39–52 (2020).

Ali, R. A, Muhammad, K. A. & Qadir, O. K. A survey of nitrate and nitrite contents in vegetables to assess the potential health risks in Kurdistan, Iraq. In: IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science (IOP Publishing, 2021).

Bowles E, Burleigh M, Mira A, Van Breda S, Weitzberg E, Rosier B. Nitrate: “the source makes the poison”. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 1–27 (2024).

Vogiatzi, G., Liontos, M., Kostakis, M., Maragou, N. & Thomaidis, N. S. An updated review on nitrate exposure from drinking water and dietary sources and effects on human health. Glob. Nest J. 27 (2). (2025).

Tan, L., Stagg, L. & Hanlon, E. Associations between vegetable nitrate intake and cardiovascular disease risk and mortality: a systematic review. Nutrients 16, 1511 (2024).

Na, J. et al. The health effects of dietary nitrate on sarcopenia development: prospective evidence from the UK biobank. Foods 14 (1), 43 (2024).

Craig, C. L. et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12- country reliability and validity. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 35 (8), 1381–1395 (2003).

Majid, M. et al. Developing a relatively validated and reproducible food frequency questionnaire in Baghdad, Iraq. Glob. J. Public Health Med. 4 (1), 510–522 (2022).

Bondonno, C. P. et al. Vegetable nitrate intake, blood pressure and incident cardiovascular disease: Danish diet, cancer, and health study. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 36 (8), 813–825 (2021).

Bahadoran, Z. et al. Association between dietary intakes of nitrate and nitrite and the risk of hypertension and chronic kidney disease: Tehran lipid and glucose study. Nutrients 8 (12), 811 (2016).

Mirmiran, P., Teymoori, F., Farhadnejad, H., Mokhtari, E. & Salehi-Sahlabadi, A. Nitrate containing vegetables and dietary nitrate and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a case control study. Nutr. J. 22 (1), 3 (2023).

Dejam, A. et al. Erythrocytes are the major intravascular storage sites of nitrite in human blood. Blood 106 (2), 734–739 (2005).

Kleinbongard, P. et al. Plasma nitrite reflects constitutive nitric oxide synthase activity in mammals. Free Radical Biol. Med. 35 (7), 790–796 (2003).

Pennington, J. A. Dietary exposure models for nitrates and nitrites. Food Control 9 (6), 385–395 (1998).

Bryan, N. S. Cardioprotective actions of nitrite therapy and dietary considerations. Front. Biosci. Landmark 14 (12), 4793–4808 (2009).

Duncan, C. et al. Chemical generation of nitric oxide in the mouth from the enterosalivary circulation of dietary nitrate. Nat. Med. 1 (6), 546–551 (1995).

Jansson, E. Å. et al. A mammalian functional nitrate reductase that regulates nitrite and nitric oxide homeostasis. Nat. Chem. Biol. 4 (7), 411–417 (2008).

Cines, D. B. et al. Endothelial cells in physiology and in the pathophysiology of vascular disorders. Blood, J. Am. Soc. Hematol. 91 (10), 3527–3561 (1998).

Khalifi, S. et al. Dietary nitrate improves glucose tolerance and lipid profile in an animal model of hyperglycemia. Nitric Oxide 44, 24–30 (2015).

Stokes, K. Y. et al. Dietary nitrite prevents hypercholesterolemic microvascular inflammation and reverses endothelial dysfunction. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circulat. Physiol. 296 (5), H1281–H1288 (2009).

Conrad, Z., Raatz, S. & Jahns, L. Greater vegetable variety and amount are associated with lower prevalence of coronary heart disease: National health and nutrition examination survey, 1999–2014. Nutr. J. 17 (1), 67 (2018).

Bahadoran, Z., Ghasemi, A., Mirmiran, P., Azizi, F. & Hadaegh, F. Beneficial effects of inorganic nitrate/nitrite in type 2 diabetes and its complications. Nutr. Metab. 12 (1), 1–9 (2015).

Iso, F. Vegetables and derived products-determination of nitrite and nitrate content-Molecular absorption spectrometric method. Int. Org. Standard. Geneva (Switzerland), ISO 6635, 1984 (1984).

Mohamed, A. A., Mubarak, A. T., Fawy, K. F. & El-Shahat, M. F. Modification of AOAC method 973.31 for determination of nitrite in cured meats. J. AOAC Int. 91 (4), 820–827 (2008).

Okati-Aliabad, H., Ansari-Moghaddam, A., Kargar, S. & Jabbari, N. Prevalence of obesity and overweight among adults in the Middle East countries from 2000 to 2020: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Obesity 2022 (1), 8074837 (2022).

Murray, C. J. et al. Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet 396 (10258), 1223–1249 (2020).

Tseng, E. et al. Effects of the dietary approaches to stop hypertension diet and sodium reduction on blood pressure in persons with diabetes. Hypertension 77 (2), 265–274 (2021).

Afshin, A. et al. Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet 393 (10184), 1958–1972 (2019).

Aune, D. et al. Fruit and vegetable intake and the risk of cardiovascular disease, total cancer and all-cause mortality—a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Int. J. Epidemiol. 46 (3), 1029–1056 (2017).

Inoue-Choi, M. et al. Development and calibration of a dietary nitrate and nitrite database in the NIH–AARP Diet and Health Study. Public Health Nutr. 19 (11), 1934–1943 (2015).

Blekkenhorst, L. C. et al. Development of a reference database for assessing dietary nitrate in vegetables. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 61 (8), 1600982 (2017).

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to express their gratitude to the Tishk International University for providing financial support for this research under grant number RC/ TIU/ SU/ 2025/4052025.

Funding

Current work was funded by Tishk International University under grant number RC/ TIU/ SU/ 2025/4052025.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AH and FJ were responsible for the study design, oversight, hypothesis development, and execution of the study. AAMAE and EFO contributed to writing the initial manuscript and conducting the statistical analysis. SO managed data collection and participant recruitment. EFO, JB, and HP also participated in statistical analysis, along with data visualization and validation. MPK and ASC were involved in manuscript writing, statistical work, and editing. FJ and AN performed the revision of the article. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the article for submission.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All participants provided written informed consent prior to their involvement in the study. The study protocol received approval from the Tishk International University under grant number RC/ TIU/ SU/ 2025/4052025. We affirm that the methods were conducted in accordance with the guidelines and regulations outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Additionally, written informed consent was obtained from the legal guardians of participants who were illiterate.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

El-Sehrawy, A.A.M.A., Hjazi, A., Nourmohammad, A. et al. The association between vegetable-derived nitrate and nitrite intake, cardiovascular risk factors and glycemic markers in obese individuals. Sci Rep 16, 707 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30239-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30239-3