Abstract

Previous studies have proposed multiple diagnostic criteria based on cholesterol and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels to differentiate pleural exudates from transudates. However, these criteria have not been widely validated, and no study has compared their diagnostic accuracies within the same population. This study recruited patients from retrospective (BUFF) and prospective (SIMPLE) cohorts. Pleural biopsy, microbiological culture, and effusion cytology were used to verify the causes of exudates or transudates. The diagnostic accuracy of pleural cholesterol and LDH levels in identifying exudates was evaluated using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves. Subsequently, the accuracies of seven previously reported cholesterol- and LDH-based classification criteria were compared with those of Light’s criteria. Pleural fluid cholesterol levels and LDH activity were significantly higher in exudates than in transudates. The area under the ROC curve (AUC) for pleural fluid cholesterol and LDH levels was 0.90 (95% CI: 0.86–0.94) and 0.87 (95% CI: 0.82–0.92) in combined cohort, respectively. We found that the diagnostic accuracy of the combination of pleural fluid cholesterol > 1.04 mmol/L (40 mg/dL) or pleural LDH > 0.6 upper limit of serum LDH reference interval was comparable to that of Light’s criteria, whereas the other criteria were less accurate. Combining pleural fluid cholesterol and LDH levels using the preceding thresholds has comparable accuracy to Light’s criteria for separating exudates from transudates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pleural effusions can be classified as exudates or transudates, based on their pathophysiological mechanisms1. Exudative pleural effusions result from increased pleural membrane permeability due to inflammation, whereas transudative pleural effusions arise from elevated hydrostatic pressure or decreased oncotic pressure2,3. Common causes of exudates include malignancy, pneumonia, and tuberculosis, whereas congestive heart failure is the leading cause of transudates4,5. Accurate differentiation between exudates and transudates is the first step in the etiological diagnosis of pleural effusions6. Patients with transudative effusions typically do not require further diagnostic workup and can be managed with systemic therapy alone, whereas exudative effusions necessitate invasive procedures to establish the underlying cause3. Light’s criteria are the most widely used method for distinguishing exudates from transudates, with a sensitivity approaching 100% for identifying exudates, but with a specificity of approximately 70%7,8,9. Up to one-third of transudates may be misclassified as exudates, particularly in patients receiving diuretic therapy10,11,12. Therefore, improved methods for distinguishing between exudative and transudative pleural effusions are needed8,13.

Previous studies have suggested that pleural cholesterol can aid in differentiating exudates from transudates14,15. Several diagnostic criteria have been proposed based on pleural fluid cholesterol and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels16,17,18,19,20,21,22. However, these criteria have not been validated widely. Moreover, no previous study has simultaneously compared these criteria in the same patient cohort. In this study, we systematically evaluated and compared the diagnostic accuracies of various cholesterol- and LDH-based classification criteria for pleural effusion differentiation within the same cohort. This study followed the Standards for Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (STARD) guidelines23.

Results

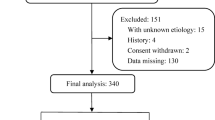

A total of 156 patients with undiagnosed pleural effusions were included in the BUFF cohort, and 145 patients in the SIMPLE cohort. In the BUFF cohort, 122 exudates and 34 transudates were observed. The SIMPLE cohort comprised 120 exudates and 25 transudates. In the two combined cohorts, 242 exudates were included, with the following causes: 74 cases of parapneumonic effusion, 97 cases of malignant pleural effusion, 61 cases of tuberculous pleuritis, 4 cases of pulmonary embolism, and 6 cases of other diseases (2 interstitial lung diseases, 1 pneumothorax, 2 mixed connective tissue diseases, and 1 idiopathic pleural effusion). The 59 transudate cases included 54 cases of congestive heart failure, 4 cases of hypoproteinemia, and 1 case of cirrhosis (Table 1).

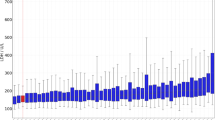

Pleural fluid cholesterol and LDH levels in transudates and exudates

As shown in Fig. 1, the median pleural fluid cholesterol level in patients with exudative pleural effusions from the BUFF cohort was 1.76 (1.11–2.25) mmol/L [68 (43–87) mg/dL], whereas in patients with transudative pleural effusions, it was 0.68 (0.43–0.79) mmol/L [26 (17–31) mg/dL], and the difference was statistically significant (P < 0.001). In the SIMPLE cohort, the median pleural fluid cholesterol level for exudates was 1.69 (1.21–2.23) mmol/L [65 (47–86) mg/dL], and for transudates, it was 0.53 (0.41–0.81) mmol/L [20 (16–31) mg/dL], with a statistically significant difference (P < 0.001). Similar results were observed in the combined cohort (p < 0.001). The median pleural fluid LDH level in patients with exudative pleural effusion was significantly higher than that in patients with transudative pleural effusion in both the BUFF and SIMPLE cohorts (both p < 0.05). Specifically, in the BUFF cohort, the median LDH levels were 370 IU/L (174–820 IU/L) for exudates and 112 IU/L (77–151 IU/L) for transudates. In the SIMPLE cohort, the median LDH levels were 246 IU/L (169–471 IU/L) for exudates and 84 IU/L (62–103 IU/L) for transudates. Similar results were observed in the combined cohort (p < 0.001).

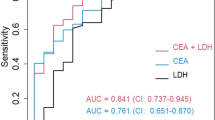

Figure 2 shows the ROC curves for pleural fluid cholesterol and LDH levels in the differentiation of exudates and transudates across cohorts. In the BUFF cohort, the AUC for pleural cholesterol was 0.88 (95% CI: 0.81–0.94). In the SIMPLE cohort, the AUC for pleural cholesterol was 0.93 (95% CI: 0.86–0.97). In the combined cohort, the AUC for pleural cholesterol was 0.90 (95% CI: 0.86–0.94). For LDH, the AUC in the SIMPLE cohort was 0.90 (95% CI: 0.83–0.97), 0.85 (95% CI: 0.78–0.91) in the BUFF cohort, and 0.87 (95% CI: 0.82–0.92) in the combined cohort.

When the two cohorts were combined and the pleural cholesterol cutoff value was set at 1.04 mmol/L (40 mg/dL), according to Lépine’s study16, the diagnostic sensitivity for cholesterol was 0.81 (95% CI: 0.75–0.85) and specificity was 0.86 (95% CI: 0.75–0.93). Similarly, when the LDH cutoff was set at 144 IU/L (60% of the upper limit of the serum reference range), the diagnostic sensitivity and specificity for LDH were 0.82 (95% CI: 0.77–0.86) and 0.78 (95% CI: 0.68–0.88), respectively. The sensitivity of the combined determination of pleural fluid cholesterol and LDH, with an “or” rule, was 0.91 (95% CI:0.87–0.94), and the specificity was 0.73 (95% CI:0.60–0.83).

Comparison of light’s criteria and other cholesterol- and LDH-based criteria

Table 2 presents the diagnostic performance of the previously reported cholesterol- and LDH-based classification criteria for differentiating exudates from transudates in our combined cohort. Among the existing criteria, only Lépine’s criteria showed a diagnostic sensitivity and specificity comparable to those of Light’s criteria. The overall diagnostic accuracy of the other criteria was generally lower than that of Light’s criteria, particularly with respect to the sensitivity.

Discussion

Light’s criteria are the preferred method for differentiating exudates from transudates8. However, this method requires the simultaneous collection of serum and pleural fluid from patients, followed by biochemical analysis, making the process relatively cumbersome. Consequently, many studies have attempted to develop improved alternatives using fewer parameters to differentiate between exudates and transudates. The criteria based on effusion chemistry (e.g., albumin and protein) are valuable because serum collection was avoided. Pleural cholesterol level is a potential diagnostic marker for this differentiation. According to a meta-analysis, the sensitivity and specificity of cholesterol for differentiating exudates and transudates were 0.88 and 0.96, respectively24, indicating that cholesterol has a high value for distinguishing between effusion types.

Differentiating between exudates and transudates is crucial for managing pleural effusions. Transudates do not require further investigation and can be managed with diuretic therapy, whereas exudates may require invasive procedures, such as pleural biopsy, to identify the underlying cause. Therefore, the most critical aspect in the differentiation of exudates and transudates is minimizing the misdiagnosis of exudates, while avoiding unnecessary invasive procedures in transudate patients. Consequently, sensitivity is more significant than specificity in the diagnostic process of differentiating exudates from transudates, which explains why Light’s criteria employ disjunctive (“or ”) rather than conjunctive (“and ”) rather than conjunctive rules in their composite tests.

The AUC for pleural fluid cholesterol was 0.90 in our combined cohort. When used alone, the specificity is inevitably lower to maintain high sensitivity. Therefore, cholesterol levels should be combined with other parameters, such as protein and LDH levels, to preserve a reasonable specificity. Currently, seven cholesterol- and LDH-based diagnostic criteria have been described for differentiating exudates from transudates, with cholesterol cutoff values typically ranging from 40 mg/dL (1.04 mmol/L) to 60 mg/dL (1.55 mmol/L)16–22. In diagnostic tests, there is a trade-off between the sensitivity and specificity25. Lower cholesterol or LDH cut-off values can improve sensitivity. If only LDH and cholesterol are combined, the joint sensitivity when selecting a cutoff can be calculated as:

Sen = 1 - (1 - Sencho) × (1 - SenLDH),

where Sencho and SenLDH represent the sensitivity of cholesterol and LDH, respectively. When the sensitivities of both parameters are 0.80, the combined sensitivity can reach 0.96, which is roughly equivalent to Light’s criteria. In our study, when the cutoff for cholesterol was set at 40 mg/dL, the sensitivity and specificity for differentiating exudates were 0.81 and 0.86, respectively. When the cutoff for serum LDH was set at 60% of the upper limit of the reference range (144 IU/L), the diagnostic sensitivity and specificity were 0.82 and 0.78, respectively. The combination of pleural cholesterol and LDH provided a high diagnostic sensitivity of 0.97. The low sensitivities of the criteria proposed by Kummerfeldt et al.17, Gonlugur et al.18, Gázquez et al.19, Garcia-Pachón et al.21, Heffner et al.20, and Costa et al.22 are primarily attributable to the elevated cholesterol cutoff values, despite the achievement of higher specificity. The reason why Lépine’s criteria16 achieved a sensitivity of 0.91, comparable to Light’s criteria, is primarily because the cholesterol cutoff was set at approximately 40 mg/dL, and the LDH cutoff was set at 0.6 of the normal serum LDH reference range upper limit. Therefore, we believe that these cutoff values have the potential to be applied in clinical settings.

Although this study is the first to directly compare the accuracy of seven cholesterol- and LDH-based diagnostic criteria for differentiating exudates and we ultimately found that only Lépine’s criteria were comparable to Light’s criteria, there are some limitations to our study. First, it was a single-center study. In particular, the reliability of our proposed cutoff values, with cholesterol at 40 mg/dL and LDH at 0.6 of the serum reference range upper limit, needs to be validated by other centers. Second, in our study, the sensitivity of Light’s criteria was only 0.91, which was somewhat lower than that reported in previous studies. We speculate that this discrepancy may be attributed to differences in the study population (e.g., ethnicity and age), which could explain why our findings diverge from those of prior studies. Furthermore, a formal statistical comparison among the various cholesterol and LDH criteria was not conducted because of the requirement for an exceptionally large sample size, which would have been impractical to obtain26.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that pleural cholesterol levels have high diagnostic accuracy for exudative pleural effusions. Cholesterol- and LDH-based diagnostic criteria for differentiating exudates can serve as alternatives to Light’s criteria. Among these, Lépine’s criteria are the most reliable.

Methods

Participants

This study included patients from the BUFF and SIMPLE cohorts. The BUFF cohort was a retrospective cohort of patients who presented to the Affiliated Hospital of Inner Mongolia Medical University (AHIMMU) between July 2017 and July 201827. The SIMPLE cohort was a prospective cohort of patients who visited AHIMMU between September 2018 and July 202128. The inclusion criteria for both cohorts were as follows: (i) undiagnosed pleural effusions and (ii) patients who underwent diagnostic thoracentesis. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (i) age < 18 years, (ii) pleural effusions caused by trauma, (iii) undetermined diagnosis at discharge, (iv) incomplete pleural fluid or serum biochemical data, and (v) pregnancy.

Both cohorts were approved by the Ethics Committee of Inner Mongolia Medical University (Approval Numbers 2021014 and 2018011). Given the retrospective nature of the BUFF cohort study, the need for informed consent was waived. All participants in the SIMPLE cohort provided informed consent. The study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Diagnostic criteria

All enrolled patients underwent etiological diagnosis, which included a detailed clinical history, physical examination, and ancillary investigations. These investigations comprised hematological, biochemical, radiological, histological, and microbiological assessments29. The final diagnosis was independently determined by two senior clinicians (Zhi-De Hu and Li Yan). In cases of disagreement, a consensus was reached through discussion.

Pleural fluid and serum biochemical analysis

Pleural fluid and serum biochemical results at the time of hospital presentation were extracted from electronic medical records. Biochemical analyses of pleural fluid and serum were performed using AU5800 or Roche C8000 analyzers, which demonstrated a high intersystem consistency. The upper reference limit for serum LDH level in our laboratory was 240 IU/L. The clinical data of the participants were blinded to the laboratory technician responsible for the measurement.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are expressed as medians and interquartile ranges (IQR). The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to determine the normality of the data distribution. We used t-test or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to compare data with a normal distribution. For skewed distributed data, we used the Mann-Whitney or Kruskal-Wallis tests for comparison. Categorical data were compared using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact probability test. The diagnostic accuracy of pleural fluid cholesterol and LDH for differentiating exudates from transudates was evaluated using a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. All statistical analyses and graphical presentations were performed using R software. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to ethical restrictions but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Light, R. W. Clinical practice. Pleural effusion. N Engl. J. Med. 346, 1971–1977. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMcp010731 (2002).

DeBiasi, E. M. & Feller-Kopman, D. Anatomy and applied physiology of the pleural space. Clin. Chest Med. 42, 567–576. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccm.2021.08.005 (2021).

Heffner, J. E. Discriminating between transudates and exudates. Clin. Chest Med. 27, 241–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccm.2005.12.008 (2006).

Tian, P. et al. Prevalence, Causes, and health care burden of pleural effusions among hospitalized adults in China. JAMA Netw. Open. 4, e2120306. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.20306 (2021).

Porcel, J. M., Esquerda, A., Vives, M. & Bielsa, S. Etiology of pleural effusions: analysis of more than 3,000 consecutive Thoracenteses. Arch. Bronconeumol. 50, 161–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arbres.2013.11.007 (2014).

Light, R. W. The undiagnosed pleural effusion. Clin. Chest Med. 27, 309–319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccm.2005.12.002 (2006).

Light, R. W., Macgregor, M. I., Luchsinger, P. C. & Ball, W. C. Jr. Pleural effusions: the diagnostic separation of transudates and exudates. Ann. Intern. Med. 77, 507–513. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-77-4-507 (1972).

Porcel, J. M. & Light, R. W. Pleural fluid analysis: are light’s criteria still relevant after half a century? Clin. Chest Med. 42, 599–609. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccm.2021.07.003 (2021).

Light, R. W. The light criteria: the beginning and why they are useful 40 years later. Clin. Chest Med. 34, 21–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccm.2012.11.006 (2013).

Block, D. R. & Algeciras-Schimnich, A. Body fluid analysis: clinical utility and applicability of published studies to guide interpretation of today’s laboratory testing in serous fluids. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 50, 107–124. https://doi.org/10.3109/10408363.2013.844679 (2013).

Porcel, J. M. Biomarkers in the diagnosis of pleural diseases: a 2018 update. Ther. Adv. Respir Dis. 12, 1753466618808660. https://doi.org/10.1177/1753466618808660 (2018).

Porcel, J. M. Identifying transudates misclassified by light’s criteria. Curr. Opin. Pulm Med. 19, 362–367. https://doi.org/10.1097/MCP.0b013e32836022dc (2013).

Zheng, W. Q. & Hu, Z. D. Pleural fluid biochemical analysis: the past, present and future. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 61, 921–934. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2022-0844 (2023).

Valdés, L. et al. Cholesterol: a useful parameter for distinguishing between pleural exudates and transudates. Chest 99, 1097–1102. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.99.5.1097 (1991).

Hamal, A. B., Yogi, K. N., Bam, N., Das, S. K. & Karn, R. Pleural fluid cholesterol in differentiating exudative and transudative pleural effusion. Pulm Med. 2013 (135036). https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/135036 (2013).

Lépine, P. A. et al. Simplified criteria using pleural fluid cholesterol and lactate dehydrogenase to distinguish between exudative and transudative pleural effusions. Respiration 98, 48–54. https://doi.org/10.1159/000496396 (2019).

Kummerfeldt, C. E. et al. Improving the predictive accuracy of identifying exudative effusions. Chest 145, 586–592. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.13-1142 (2014).

Gonlugur, U. & Gonlugur, T. E. The distinction between transudates and exudates. J. Biomed. Sci. 12, 985–990. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11373-005-9014-1 (2005).

Gázquez, I. et al. Comparative analysis of light’s criteria and other biochemical parameters for distinguishing transudates from exudates. Respir Med. 92, 762–765. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0954-6111(98)90009-9 (1998).

Heffner, J. E., Brown, L. K. & Barbieri, C. A. Diagnostic value of tests that discriminate between exudative and transudative pleural effusions. Prim. Study Investigators Chest. 111, 970–980. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.111.4.970 (1997).

Garcia-Pachon, E. & Padilla-Navas, I. Pleural fluid cholesterol and lactate dehydrogenase for separating exudates from transudates. Chest 110, 1375–1376. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.110.5.1375-b (1996).

Costa, M., Quiroga, T. & Cruz, E. Measurement of pleural fluid cholesterol and lactate dehydrogenase. A simple and accurate set of indicators for separating exudates from transudates. Chest 108, 1260–1263. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.108.5.1260 (1995).

Bossuyt, P. M. et al. STARD 2015: an updated list of essential items for reporting diagnostic accuracy studies. Clin. Chem. 61, 1446–1452. https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2015.246280 (2015).

Shen, Y. et al. Can cholesterol be used to distinguish pleural exudates from transudates? Evidence from a bivariate meta-analysis. BMC Pulm Med. 14 https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2466-14-61 (2014).

Linnet, K., Bossuyt, P. M., Moons, K. G. & Reitsma, J. B. Quantifying the accuracy of a diagnostic test or marker. Clin. Chem. 58, 1292–1301. https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2012.182543 (2012).

Lee, Y. C. G., Davies, R. J. O. & Light, R. W. Diagnosing pleural effusion: moving beyond transudate-exudate separation. Chest 131, 942–943. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.06-2847 (2007).

Jiang, M. P. et al. Diagnostic accuracy of pleural fluid to serum carcinoembryonic antigen ratio and delta value for malignant pleural effusion: findings from two cohorts. Ther. Adv. Respir Dis. 17, 17534666231155745. https://doi.org/10.1177/17534666231155745 (2023).

Han, Y. Q. et al. A study investigating markers in pleural effusion (SIMPLE): a prospective and double-blind diagnostic study. BMJ Open. 9, e027287. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-027287 (2019).

Roberts, M. E. et al. British thoracic society guideline for pleural disease. Thorax 78, s1–s42. https://doi.org/10.1136/thorax-2022-219784 (2023).

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by the Program of Inner Mongolia Medical University (NO: YKD2023MS042, by Wen JX).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Su-Na Cha collected data, performed the experiments, analyzed data, and drafted the manuscript. Yan Niu, Jian-Xun Wen, Cheng Yan, Li Yan, Lei Zhang, Mei-Ying Wang, Wei Jiao, Wen-Qi Zheng, provided technical assistance. Li Yan and Zhi-De Hu enrolled the participants in Hohhot and made their diagnoses. Wen-Qi Zheng and José M. Porcel edited the manuscript and added intellectual contributions. Zhi-De Hu designed the experiments, supervised the study, edited the paper, and confirmed the final version. All authors approved the submission of this manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Research ethics

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Inner Mongolia Medical University (Approval Numbers 2021014 and 2018011). Informed consent was obtained from all participants and/or their legal guardians.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cha, SN., Niu, Y., Wen, JX. et al. Accuracy of seven criteria based on cholesterol and lactate dehydrogenase for differentiating exudative and transudative pleural effusions. Sci Rep 16, 749 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30258-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30258-0