Abstract

Abrupt relief increases at the blunt base are common in aerospace because a recirculation zone decreases pressure and increases drag. This study investigates the control of base pressure at Mach 1.0 by using quarter-ribs placed at various points within an axisymmetric duct. CFD simulations with ANSYS Fluent identified the optimal rib size, position, and nozzle pressure ratio (NPR) for either maximizing or minimizing base pressure. Air flows from a converging nozzle into a 16 mm diameter duct, with lengths ranging from L/D = 1 to 6, rib radii from 1 mm to 2.5 mm, and placements from L/D = 0.5 to 2.0. Results demonstrate that ribs significantly impact base pressure by interacting with the shear layer and duct wall. This interaction affects flow reattachment and pressure differences, which depend on the size and location of the ribs. Ribs at 0.5D and 1D slightly increase base pressure, while those at 1.5D and 2D are more effective. Larger rib radii enhance shear layer reattachment, further boosting pressure. Temperature analysis reveals a rise immediately behind the rib, attributed to the increased flow area, followed by a subsequent drop. These findings enable the optimization of passive control strategies in high-speed aerodynamics, thereby improving system reliability, reducing costs, increasing fuel efficiency, and supporting environmental goals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction and background

The study of turbulent base flows is a captivating area due to its wide-ranging applications in industry, defense, and space exploration. It primarily investigates the intricate behavior of blunt-based projectiles, fuselages, and shells, which frequently operate under low or sub-atmospheric pressures. The turbulent boundary layer continues to grow downstream as the base flows merge at the duct wall, causing the shear layer to separate from the backward-facing step1.

At the Mach number where the flow reaches sonic conditions, the flow behavior around the base becomes complex and chaotic2. For a blunt base, the flow involves separation and reattachment zones, forming a shear layer that generates strong vortices in the wake. These vortices help decrease overall drag. The total drag on an aerodynamic object includes base drag, wave drag, and skin friction. At subsonic speeds, base drag and skin friction are the primary factors, while at sonic and supersonic speeds, wave drag becomes more significant.

Base pressure plays a crucial role in the aerodynamic stability and efficiency of rockets, missiles, and supersonic vehicles. Raising the base pressure in the separated flow region can improve performance by decreasing overall drag. However, viscous effects contribute to skin friction drag, and shock waves generate wave drag—both inherent challenges of these missions that are hard to eliminate3. Over time, researchers have developed active and passive control techniques to address these issues. Active control involves stationary actuators that modify airflow by adding or removing air from components, such as slats or flaps. This process requires energy for base pressure management and enables real-time adjustments4,5. A significant disadvantage is high energy consumption, which can impact the vehicle’s weight and overall performance. Conversely, passive control modifies the flow through geometric changes—such as cavities, ribs, spikes, boat tails, and splitter plates5—offering a more straightforward and more reliable solution by altering the geometry within the duct. These methods are especially beneficial for aerospace vehicles, such as rockets, missiles, and bombs, as they can improve performance without requiring additional energy input.

Passive strategies, such as ribs, offer a more straightforward and more cost-effective approach to increasing base pressure without requiring active feedback; however, active control methods, like jet injection, can further enhance pressure recovery. Vermeersch and Bouteiller (2014) note that base drag accounts for approximately 60% to 70% of total drag at transonic speeds, yet the physical mechanisms underlying base drag remain poorly understood6,7.

The study uses computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulations to analyze internal flow control systems that enable passive flow regulation. These internal configurations eliminate the need for external support structures, allowing the precise measurement of static pressure and surface temperature at the expansion entry and wake zone5. This method improves the control and optimization of base pressure. Additionally, conducting CFD analysis before wind tunnel tests helps to limit the number of testing options. Since wind tunnel experiments are costly, CFD effectively identifies critical cases, reducing the overall number of tests needed for validation.

This study examines the effect of passive control using quarter-circular ribs on base pressure at an area ratio of 2.56 and sonic Mach numbers. These ribs modify the flow near the base, effectively influencing base pressure. Optimizing their geometry is crucial, as raising the base pressure and lowering base drag can significantly enhance aerodynamic performance.

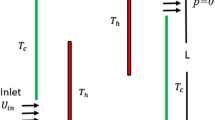

Before analyzing the data, it is essential to thoroughly understand the mechanisms underlying the sudden rise in the flow field. The complex axisymmetric expansion flow includes phenomena such as flow separation, recirculation, and reattachment. As shown in Fig. 1(a), a dividing streamline and surface separate the flow into a central zone and a recirculation region. The reattachment point is where the dividing streamline contacts the wall. Passive control techniques are employed to disrupt this flow, leading to increased base pressure and decreased base drag8.

Sudden expansion flows are widely examined in external ballistics and aerodynamics. The shear layer forms at the nozzle lip, initially separates, and then reattaches to the duct wall at some downstream point, as illustrated in Fig. 1(b). The reattachment length is the distance from the nozzle exit to where this reattachment occurs.

The Nozzle Pressure Ratio (NPR) is the ratio of the stagnation pressure in the settling chamber to the exit pressure. It influences how much the flow expands at the nozzle exit9. As the NPR increases, the flow leaving the nozzle expands to different extents. At first, it encounters both adverse and favorable pressure gradients.

The flow past a projectile illustrates external flow, where surfaces do not confine the fluid. Conversely, internal flow happens inside fully enclosed pipes. Wick (1953) observed that internal flow from a nozzle into a duct with a sudden area increase faces obstacles. Notably, at the entry point—particularly for sonic or supersonic flow—the entrance significantly influences the flow due to shock wave formation and boundary layer separation10,11.

Subsonic flow, in contrast, is influenced by inlet conditions such as pressure gradients and flow separation at the duct entrance12,13. When the inlet flow is supersonic or sonic, upstream conditions determine the corner pressure, which in turn affects the overall pressure distribution and flow stability within the duct14,15. These principles illustrate the intricate relationships between surface roughness, flow conditions, and drag components in high-speed aerodynamics16,17. Understanding these interactions is crucial for optimizing the design and performance of aerodynamic bodies across various applications. It aids in developing strategies to reduce drag, improve fuel efficiency, and enhance overall aerodynamic performance18,19.

Bashir et al.20 conducted a numerical study of turbulence models, focusing on turbulent strength at low Reynolds numbers. Their work contributed to selecting the appropriate turbulence models for accurate flow simulations. Baig et al.21 investigated the regulation of base flows using small jets, demonstrating the effectiveness of dynamic control methods in managing base pressure and reducing drag. Rehman and Khan22 examined the control of base pressure with small jets, providing insights into designing and implementing active flow control techniques. Faheem et al.23 studied the mean flow features of a supersonic triple-jet setup, thereby advancing understanding of complex jet interactions in high-speed flows. Sajali et al.24 conducted a numerical study of the flow around a non-circular cylinder, providing data relevant to flow control around bluff bodies. Khan et al.25 investigated the passive control of base drag in compressible subsonic flow using multiple cavities, emphasizing the effectiveness of cavity configurations in reducing drag. Bellary et al.26 performed numerical models of base pressure regulation in a rapid growth in the relief of the tube at M = 1.6 with 1/4th -circular ribs. Their findings helped optimize rib designs for better flow control.

In another study, Bellary et al.27 examined the computational aspects of thrust produced by converging-diverging nozzles at various diverging angles. Their findings provided valuable insights into optimizing nozzle designs for high-speed applications. Makwana et al.28 performed a study on the passive flow control at Mach unity from a converging nozzle using a D-shaped rib. They presumed that the base pressure is a definitive factor in determining the NPR, as well as the relief to the flow, tube size, rib spot, and rib shape.Rathakrishnan29 experimentally examined flow from a converging nozzle with a sudden expansion at different primary pressure ratios, involving three rectangular ribs with aspect ratios of 3:1, 3:2, and 3:3. He placed five rectangular ribs along the duct at 1D intervals. Results showed that a lower aspect ratio of 3:1 decreases the base pressure, while a higher aspect ratio of 3:3 increases it. These experimental results initially served as benchmarks, and CFD was used to replicate similar findings. After validating the CFD results, the author suggested that five ribs are unnecessary; instead, a single rib can produce similar effects without impacting the base pressure. Consequently, the researchers concluded that similar outcomes could be achieved by placing a single rib of different sizes at various locations. Later, a quarter rib was used to regulate the base pressure and, in turn, the base drag. This study presents the passive control of base pressure for a 16 mm diameter tube at sonic Mach M = 1.0, using quarter ribs.

Methodology: finite volume method

Governing equations

The ensuing theories are taken into deliberation:

-

i.

Turbulent flow is studied in the context of turbulent viscous degeneracy.

-

ii.

The fluid’s viscosity fluctuates with temperature, and air density also varies with the Mach number.

-

iii.

At the exit of the duct, ambient pressure exists.

-

iv.

The numerical method used in the study was Reynolds-Averaged Navier-Stokes (RANS) with the k-ε turbulence model to simulate the internal flow; thus, applying it to this situation, Sutherland’s 3-coefficient viscosity model is given below:

The reference viscosity value in kg/m·s is denoted by, where indicates viscosity. Ta stands for still temperature, K is the temperature of a standard position, and ′ is the temperature-dependent Sutherland constant. The three-dimensional continuity equation for compressible flow is as follows:

The steady continuity equation is as follows:

Where the flow velocity is represented by V.

The expression for momentum conservation is:

Where \(\:{\left(\underset{\_}{\nabla\:}\underset{\_}{V}\right)}_{o}^{s}={\left(\underset{\_}{\nabla\:}\underset{\_}{V}\right)}^{s}-\frac{1}{3}\left(\underset{\_}{\nabla\:}\cdot\:\underset{\_}{V}\right)\underset{\_}{I}\), \(\:{\left(\underset{\_}{\nabla\:}\underset{\_}{V}\right)}^{s}=\frac{\underset{\_}{\nabla\:}\underset{\_}{V}+\underset{\_}{\nabla\:}{\underset{\_}{V}}^{T}}{2}\), and \(\:{\tau\:}_{=Re}\) is the turbulent stress tensor.

The general expression for overall energy is as follows:

Where \(\:{u}_{int}\) is the internal energy, and λ is the thermal conductivity.

The k-epsilon turbulence model is suitable for internal flow due to its affordability, resilience, and sufficient accuracy. The Ansys Fluent module within the Ansys Workbench 2024/R2 software suite incorporates the k-epsilon () turbulence model used in the present study. The K-equation permits us to compute the turbulent kinetic energy.

The turbulent KE degeneracy rate is denoted by, the turbulent Prandtl number is -, and Mx is the turbulence creation. Indeed, the degeneracy is managed by,

where \(\:{\mu\:}_{t}=\rho\:{f}_{\mu\:}{C}_{\mu\:}{k}^{2}/\epsilon\:\) denotes turbulent viscosity, and the random constants are denoted as\(\:\stackrel{-}{{C}_{\mu\:}}=0.09\), \(\:\stackrel{-}{{C}_{1}}=1.44\), \(\:\stackrel{-}{{C}_{2}}=1.92\), \(\:\stackrel{-}{{f}_{\mu\:}}=1\), \(\:{\sigma\:}_{k}=1.0\), and \(\:{\sigma\:}_{{\upepsilon\:}}=1.3\).

Geometry and modelling

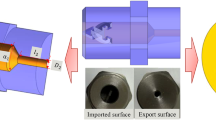

The simulation used a finite volume method with Workbench 2024/R2 software to explicitly analyze the flow in the nozzle. The model, shown in Fig. 2(a), has geometries detailed in Table 1 and was created using a Design Modeler for two orientations, as shown in Figs. 1 and 2. 1 and 2. 2(b) and 2(c), with specified boundary conditions.

Meshing and boundary conditions

A high-quality mesh—characterized by good aspect ratios, smooth cell transitions, and the absence of skewed or distorted elements—is essential for accurate and efficient simulations. In this case, using the free-face mesh type results in a structured 2D model. CFD meshing involves dividing the computational domain into discrete cells or elements. Proper, refined face meshing was implemented, as illustrated in Fig. 3, with a grid size carefully chosen to ensure convergence and reliable results. The mesh density was set to effectively capture key flow features, such as boundary layers, shock waves, and vortices, while minimizing excessive computational costs. A mesh independence study confirmed grid independence and mesh quality. The 2D model utilized a rectangular structured mesh, with element sizes determined by edge lengths due to the free-face mesh Table 2.

Assumptions and fluid properties

Assumptions help replicate flow activities accurately in a specific physical setup. Appropriate mathematical and numerical models are selected to simplify the governing equations.

Numerical modeling involves solving the governing equations simultaneously, which requires selecting appropriate mathematical models and accounting for factors such as boundary conditions, mesh quality, and the choice of numerical methods. While these methods have limitations in accurately capturing physical phenomena, they have proven reliable over decades and offer valuable insights into flow behavior. Therefore, choosing elements that closely mimic flow dynamics is crucial. This study highlights assumptions that could undermine the accuracy of the physical representation, including the specific assumptions and features discussed here.

-

i.

The flow is considered steady and two-dimensional due to the system’s symmetric geometry.

-

ii.

Air density varies.

-

iii.

Because turbulent flow significantly affects viscous dissipation at a specific flow velocity, it is included in the analysis.

-

iv.

The fluid’s viscosity varies with temperature.

-

v.

Under standard atmospheric conditions, the flows exit the duct. Likewise, at typical ambient pressure, the flows also leave the duct.

Since the nozzle flow is considered turbulent, the compressible flow is modeled using the standard k-epsilon model. The equations provided below accurately depict this turbulent behavior.

Numerical and experimental results validation

The study started by replicating Rathakrishnan’s experiment, which involved five evenly spaced ribs within a duct, as shown in Fig. 4, to validate the approach. This also helped deepen the understanding of the flow physics inside the duct. Rathakrishnan’s observations on how base pressure varies with different NPR and L/D ratios, detailed in Table 3, provided a benchmark for comparison. Both flow setups—one with ribs (controlled) and one without (uncontrolled)—were simulated to confirm the accuracy of the numerical results.

A comparison between the CFD results and Rathakrishnan’s (29) earlier experimental results was conducted using a controlled model with ribs having an aspect ratio of 3:1. It was observed that a duct with five ribs of this aspect ratio showed good agreement, as illustrated in Figs. 5(a) to (d). The error percentage was under 5%, demonstrating the method’s reliability. Although isentropic flow theory suggests that sonic conditions should occur at a primary pressure ratio of 1.89 at the nozzle exit, real flows are inherently viscous and non-isentropic, causing slight deviations that are considered acceptable. Moreover, the complex behavior of compressible flows at sonic Mach numbers—characterized by shock waves and nonlinear effects—may result in minor variations in base pressure. Factors such as backflow and boundary layer interactions at different L/D ratios can also influence these variations.

Mesh independence study

The Mesh Independence Study (MIS) aims to determine the optimal mesh size for achieving accurate numerical simulations while maintaining computational efficiency. It examined various mesh configurations, from coarse to fine, with increasing numbers of nodes and elements, as shown in Table 4. The coarsest mesh had the fewest nodes and elements, which reduced computational costs but introduced numerical diffusion and less precise base pressure predictions. This resulted in an inadequate capture of flow separation and recirculation regions, impacting the accuracy of the passive control analysis.

As the mesh was refined to a medium level, the number of nodes and elements increased, enhancing the resolution of flow structures. Base pressure predictions stabilized, exhibiting less variation than on the coarser mesh. Flow separation and reattachment areas became clearer, offering a better understanding of the passive control mechanism while maintaining manageable computational costs.

Further refinement led to a fine and finer mesh, where velocity and pressure gradients were more accurately resolved. Base pressure predictions approached converged values with minimal variation compared to the medium mesh, ensuring reliable results. Flow structures, shock interactions, and turbulence effects were well captured, contributing to improved simulation accuracy.

The finest mesh had the most nodes and elements, yet its results were nearly identical to the fine mesh, confirming mesh independence. No significant.

Improvement in accuracy was observed, but the computational cost increased drastically.

The MIS results indicated that after a specific level of mesh refinement, the base pressure stabilized, meaning that further refinement did not significantly alter the results. The optimal mesh was selected to balance accuracy and computational expense, typically favoring the finer mesh, as illustrated in Fig. 6.

Results and discussion

Before analyzing the data, it is crucial to understand the cause of the sudden increase in the flow field. In subsonic flows, the nozzle exit boundary layer develops as a free shear layer and eventually contacts the duct wall downstream. The reattachment point is where the flow reattaches, and the reattachment length is the distance from the base to this point. One or more vortices form between the reattachment point, the base, and the edge of the free shear layer. The primary vortex, which is the strongest, is located closest to the base and draws fluid from the base into the main flow on the other side of the shear layer. This process creates low pressure at the base. Since vortex shedding occurs periodically, the pumping also becomes periodic, causing fluctuations in base pressure. These fluctuations are usually small and can be approximated by a mean value. The periodic vortex motion causes the flow inside the duct to oscillate, sometimes quite severely, depending on the geometry and flow conditions.

The flow Mach number and reattachment affect the strength of the primary vortex, significantly influencing suction at the base and causing flow oscillations within the duct. As a result, waves significantly impact vortex strength in any case, since the base pressure and oscillations are closely linked to the primary vortex. If the duct features annular grooves, more vortices are shed at the rib, and these smaller vortices can boost the base pressure by enhancing mixing. Passive control techniques disrupt this flow, resulting in increased base pressure and a decrease in base drag.

Analysis for rib orientation 1

Figure 7 shows the setup of the converging nozzle in orientation one, along with the duct. The quarter rib is positioned so its curved face faces the flow from the converging nozzle. After passing through the nozzle, the shear layer enters a circular duct with a diameter of 16 mm. The following section presents the study’s results, focusing on how control placement at various locations and duct lengths—ranging from L = 1D to 6D—affects performance. The expansion level varies from over-expanded to correctly expanded and under-expanded. The aim is to assess the impact of the control mechanism on base pressure and the effectiveness of the rib under different conditions.

Base pressure analysis for L/D = 1, orientation 1

Figure 8 presents the base pressure outcomes from this study when the rib is placed 8 mm or more on or after the base, as a function of NPR for various rib sizes. It shows that without control, the downward trend is reversed at NPR = 3, indicating that the nozzle is under-expanded. There is a minor rise in the base pressure for NPRs greater than 3. This trend is expected due to small duct diameters, where the reattachment length is shorter than in larger ducts. When control, by quarter rib circle, is applied to a rib with a 1 mm radius, the decreasing tendency in base pressure reverses at NPR = 2. Increasing the NPR further causes a steady rise in the base pressure, and at the highest NPR tested, the base pressure nearly equals ambient pressure. Therefore, if the goal is to match the base pressure to atmospheric pressure, this rib size is sufficient for the mission. Increasing the radius of the rib from 1.5 mm to 2 mm and 2.5 mm results in a significant rise in base pressure. Ultimately, the decision can be made based on the specific requirements of the user.

Base pressure analysis for L/D = 2, orientation 1

Figure 9 presents the results of this study, illustrating the effects of different rib sizes and positions. In the no-control scenario, the base pressure drops until NPR = 3, then rises again for higher NPR values. The data set includes two rib sizes: 1.5 mm and 2.5 mm radii, positioned at L/D values of 0.5, 1.0, and 1.5. As expected, the 1.5 mm radius ribs at these positions yield base pressure ratios of 1.3, 1.49, and 1.5. For the larger 2.5 mm ribs, the ratios are 2.5, 2.8, and 2.8. Results indicate that at L/D = 1 and 1.5, the base pressure ratios are nearly identical. These findings suggest that the reattachment point occurs around L/D = 1; therefore, placing the control near this location is most effective, as secondary vortices from the rib edges interact with the dividing streamline and base vortices. This interaction helps redirect some mass toward the base region, thereby increasing the base pressure.

Base pressure analysis for L/D = 3, orientation1

Figure 10 presents the results of this study for NPRs from 1.5 to 5, with rib radii of 1.5 mm and 2.5 mm at L/D ratios of 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, and 2.0. It shows that when the rib is at L/D = 0.5, the base pressure ratio is about 1.4. For all other rib positions, there is little change in the base pressure, and the ratio stays around 1.5. These findings confirm that placing the rib beyond L/D = 1 does not affect the base pressure in this duct diameter. It is known that passive flow management using a rib placed beyond the reattachment point can significantly alter the base pressure. Any change in base pressure involves the interface between the vortices from the rib’s edges, the base vortex, and the dividing streamline.

Base pressure analysis for L/D = 4, orientation 1

Figure 11 presents the base pressure results versus NPR for duct L/D = 4, examining three rib positions at L/D = 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, and 2.0, with rib radii of 1.5 mm and 2.5 mm. The outcomes are similar to those for the previous duct length of L/D = 3. It is evident that for shorter duct lengths, especially those with L/D ratios of 1, 2, and 3, atmospheric pressure has a noticeable effect. However, when the duct span increases sufficiently, the impact of atmospheric pressure becomes negligible. As previously mentioned, rib positions beyond L/D = 1 have little to no effect on the base pressure.

Base pressure analysis for L/D = 5, orientation 1

Figure 12 illustrates the relationship between the base pressure and the nozzle pressure ratio (NPR), which ranges from 1.5 to 5, for an extended duct length (L/D = 5) and rib radii of 1.5 and 2.5. The ribs are placed at L/D = 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, and 2.0. In both scenarios, only the duct length has been increased from L/D = 4 to 5. At this length, the base pressure ratios at rib positions L/D = 1, 1.5, and 2.0 are the same for both rib radii of 1.5 mm and 2.0 mm. This similarity is primarily due to the longer duct length, which reduces the impact of rib positions.

Base pressure analysis for L/D = 6, orientation 1

Similar results are observed at a duct length of L/D = 6, as illustrated in Fig. 13. As previously discussed, the duct length significantly influences the outcomes. Once a specific length is reached, the system attains a steady state, and changes beyond that do not affect the base pressure outcomes. For a 16 mm duct diameter, a small rib radius r = 1.5 mm is adequate to fulfill user needs.

Pressure contours at 1D Location, orientation 1

(a) Pressure contour for L/D = 2, 2.5 mm rib, at 1D location and NPR = 3. (b) Pressure contour for L/D = 2, 2.5 mm rib, at 1D location and NPR = 5. (c) Pressure contour for L/D = 3, 2.5 mm rib, at 1D location and NPR = 3. Figure 14.

Figure 14(a) illustrates the pressure contour for a duct length L/D = 2, with the rib positioned at L/D = 1 and a nozzle pressure ratio of 3. The nozzle is under-expanded at this NPR. The pressure drops in the duct and behind the rib as the wall pressure declines due to the development of a recirculation zone.

Figure 14(b) illustrates the pressure contour for a duct with an L/D ratio of 2, featuring a rib at L/D = 1 and a nozzle pressure ratio of 5. As the NPR increases, under-expansion intensifies, leading to a further decrease in pressure both inside the duct and past the rib. That occurs because wall pressure drops as a recirculation zone develops.

Figure 14(c) illustrates the pressure contour for a duct with a length-to-diameter ratio (L/D) of 3, featuring a rib at L/D = 1 and a nozzle pressure ratio of 3. Since the nozzle is under-expanded, pressure assumptions lead to lower pressure values within the duct and downstream of the rib, as the wall pressure drops due to the formation of a recirculation zone.

Figure 14(d) illustrates the pressure contour at a duct length L/D = 3, with the rib positioned at L/D = 1 and a nozzle pressure ratio of 5. As the NPR increases further, the under-expansion intensifies. Consequently, the pressure drops even further within the duct and beyond the rib, driven by the reduction in wall pressure caused by the establishment of a recirculation region downstream of the rib.

Velocity contours at 1D Location, orientation 1

Figure 15(a) displays the velocity contour for L/D = 2, rib radius 2.5 mm, and rib position at L/D = 1, with a nozzle pressure ratio (NPR) of 3. From the figure, it is clear that the velocity increases downstream of the rib and then decreases further downstream.

Figure 15(b) presents the velocity contour for L/D = 2, with a rib radius of 2.5 mm and positioned at L/D = 1, at NPR = 5. The figure clearly shows an increase in velocity downstream of the rib. Additionally, a Mach disk forms near the rib at this NPR, while the velocity decreases further downstream.

Figure 15(c) presents the velocity contour at L/D = 3, with a rib radius of 2.5 mm and positioned at L/D = 1, for a nozzle pressure ratio (NPR) of 3. The figure clearly shows an increase in velocity downstream of the rib. The longer duct length causes a Mach disk to form just beyond the rib. Further downstream, the velocity decreases.

Figure 15(d) displays the velocity contour for L/D = 3, rib radius of 2.5 mm, and rib location at L/D = 1 under a nozzle pressure ratio (NPR) of 5. The figure clearly shows an increase in velocity downstream of the rib, driven by the longer duct length and the NPR increase from 3 to 5, with a Mach disk forming just beyond this rib location. Further downstream, the velocity slightly decreases.

Streamline contours at 1D Location, orientation 1

(a) Streamline contour for L/D = 2, 2.5 mm rib, at 1D location and NPR = 3. (b) Streamline contour for L/D = 2, 2.5 mm rib, at 1D location and NPR = 5. (c) Streamline contour for L/D = 3, 2.5 mm rib, at 1D location and NPR = 3. (d) Streamline contour for L/D = 3, 2.5 mm rib, at 1D location and NPR = 5.

Figure 16(a) illustrates a streamline contour with a duct length-to-diameter ratio of 2, a rib radius of 2.5 mm, and the rib positioned at L/D = 1. The diagram clearly shows two recirculation zones: one just after the exit and another near the rib. However, these recirculation zones are smaller compared to the area where the flow exits the nozzle.

Figure 16(b) displays a streamline contour with a duct length-to-diameter ratio of 2, a rib radius of 2.5 mm, and the rib positioned at L/D = 1. From the figure, it’s evident that immediately after the exit and near the rib, two recirculation zones exist. However, the recirculation zone immediately following the rib is smaller than at the nozzle exit. This size reduction is due to the increase in NPR, which causes the flow to expand over a longer distance.

Figure 16(c) presents the streamline contours for a duct slightly longer than in the previous case. The figure shows that the recirculation zone is almost entirely gone, primarily due to the increased duct length. However, the circulation bubble in the base region remains unchanged.

Figure 16(d) illustrates the streamline contours for a duct length of L/D = 3 and NPR = 5. The figure indicates that the recirculation zone is nearly eliminated here, primarily due to the influence of duct length. The circulation bubble remains typical in the base region. As NPR increases, the recirculation bubble diminishes further, leading to reductions in the recirculation zone in that area. That may be ascribed to the extent of under-expansion.

Temperature contours at 1D Location, orientation 1

(a) Temperature contour for L/D = 2, 2.5 mm rib, at 1D location and NPR = 3. (b) Temperature contour for L/D = 2, 2.5 mm rib, at 1D location and NPR = 5. (c) Temperature contour for L/D = 3, 2.5 mm rib, at 1D location and NPR = 3. (d) Temperature contour for L/D = 3, 2.5 mm rib, at 1D location and NPR = 5. (e) Temperature contour for L/D = 4, 2.5 mm rib, at 1D location and NPR = 3. (f) Temperature contour for L/D = 4, 2.5 mm rib, at 1D location and NPR = 5. (g) Temperature contour for L/D = 5, 2.5 mm rib, at 1D location and NPR = 3 (h) Temperature contour for L/D = 5, 2.5 mm rib, at 1D location and NPR = 5. (i) Temperature contour for L/D = 6, 2.5 mm rib, at 1D location and NPR = 3. (j)Temperature contour for L/D = 6, 2.5 mm rib, at 1D location and NPR = 5.

Figure 17(a) displays the temperature contour for duct length L/D = 2, NPR = 3, with the rib located at L/D = 1. The figure shows that the main jet diffuses over a short distance and then undergoes temperature recovery. Additionally, a low-temperature region appears near the rib due to the abrupt flow relief downstream.

Figure 17(b) shows similar results, with all parameters unchanged except for the nozzle pressure ratio (NPR), which has risen from 3 to 5. This increase in NPR is evident in the contour, particularly downstream of the rib.

Figure 17(c) displays the temperature contour for a duct size L/D = 3, a rib radius r = 2.5 mm, and rib placement at L/D = 1 under a nozzle pressure ratio of NPR = 3. Initially, the temperature drops in the main jet. At the rib’s position, a D-shaped recirculation zone develops as the rib initially obstructs the flow, leading to an increase in flow area downstream.

Figure 17(d) illustrates the temperature contour for a duct with L/D = 3, a rib radius r = 2.5 mm, and the rib positioned at L/D = 1 when the nozzle pressure ratio (NPR) is 5. As the NPR increases initially, the main jet’s temperature drops. At the rib’s location, a D-shaped recirculation zone develops and grows larger due to increased expansion, since the rib initially obstructs the flow and causes the downstream flow to expand.

Figure 17(e) displays the temperature contour for a duct with an L/D ratio of 4, a rib radius r = 2.5 mm, and the rib positioned at L/D = 1, under a nozzle pressure ratio of 3 (NPR = 3). At first, the main jet’s temperature decreases. At the rib’s position, a moon-shaped recirculation zone develops as the rib initially obstructs the flow, causing the downstream region to experience an increase in cross-sectional area.

Figure 17(f) displays the temperature contour for a duct with L/D = 4, a rib radius of 2.5 mm, positioned at L/D = 1, under a nozzle pressure ratio of five (NPR = 5). Initially, the temperature decreases in the main jet. At the rib location, a D-shaped recirculation zone forms as the rib initially obstructs the flow, causing the downstream flow to expand in area and resulting in a temperature drop.

Figure 17(g) shows the temperature distribution for a duct with an L/D ratio of 5, a rib radius r = 2.5 mm, and the control positioned at L/D = 1 at a nozzle pressure ratio of 3 (NPR = 3). Initially, the temperature of the main jet decreases. A moon-shaped recirculation zone forms near the rib, initially blocking the flow and leading to an increase in the flow area downstream.

Figure 17(h) displays the temperature contour for a duct length-to-diameter ratio (L/D) of 5, with a rib radius of 2.5 mm placed at L/D = 1, at a nozzle pressure ratio (NPR) of 5. The main jet first experiences a temperature decrease. At the rib position, a moon-shaped recirculation zone develops as the rib obstructs the flow initially, causing an increase in flow area downstream.

Figure 17(i) displays the temperature contour for a duct with an L/D ratio of 6, a rib radius of r = 2.5 mm, and a control located at L/D = 1, under a nozzle pressure ratio of 3 (NPR = 3). Initially, the main jet’s temperature decreases. At the rib’s location, a moon-shaped recirculation zone develops because the rib initially obstructs the flow, causing an increase in the downstream flow area and leading to a lower temperature.

Figure 17(j) displays the temperature contour for a duct with L/D = 6, a rib radius r = 2.5 mm, and the control positioned at L/D = 1, at a nozzle pressure ratio of 5 (NPR = 5). Initially, the main jet’s temperature decreases. A moon-shaped recirculation zone develops at the rib location as the rib initially obstructs the flow. Downstream, the flow area increases, and with the higher NPR, the temperature decreases even more.

Turbulence kinetic energy contours at 1D Location, orientation 1

(a) Turbulence Kinetic Energy contour for L/D = 2, 2.5 mm rib, at 1D location &. NPR = 3. (b) Turbulence Kinetic Energy contour for L/D = 2, 2.5 mm rib, at 1D location and NPR = 5. (c)Turbulence Kinetic Energy contour for L/D = 3, 2.5 mm rib, at 1D location and NPR = 3. (d)Turbulence Kinetic Energy contour for L/D = 3, 2.5 mm rib, at 1D location and NPR = 5. (e) Turbulence Kinetic Energy contour for L/D = 4, 2.5 mm rib, at 1D location and NPR = 3. (f) Turbulence Kinetic Energy contour for L/D = 4, 2.5 mm rib, at 1D location and NPR = 5. (g) Turbulence Kinetic Energy contour for L/D = 5, 2.5 mm rib, at L/D = 1, NPR = 3. (h) Turbulence Kinetic Energy contour for L/D = 5, 2.5 mm rib, L/D = 1.0, NPR = 5. (i) Turbulence Kinetic Energy contour for L/D = 6, 2.5 mm rib, at 1D location and NPR = 3. (j) Turbulence Kinetic Energy for L/D = 6, 2.5 mm rib, at 1D location and NPR = 5.

Figure 18(a) presents the turbulence kinetic energy contours for a duct with a length L/D of 2, featuring a rib radius of 2.5 mm positioned at L/D = 1, operating at a nozzle pressure ratio of 3 (NPR = 3). When the flow exits the nozzle and enters the enlarged duct at the corner, turbulence energy levels are at their lowest; however, the energy increases and peaks just downstream of the rib, forming a moon-shaped concentration.

Figure 18(b) illustrates the turbulence kinetic energy contour within a duct of length L/D = 2, featuring a rib radius of 2.5 mm positioned at L/D = 1, at a nozzle pressure ratio of five (NPR = 5). Upon exiting the nozzle and entering the widened duct at the corner, the turbulence kinetic energy levels are at their lowest. Subsequently, the energy levels increase, reaching a peak immediately downstream of the rib. This concentrated turbulence forms a moon-shaped pattern, which continues to expand as the NPR increases from 3 to 5.

Figure 18(c) illustrates the turbulence kinetic energy contour for a duct with a length-to-diameter ratio (L/D) of 3 and a rib radius of 2.5 mm, positioned at L/D = 1 under a nozzle pressure ratio of 3 (NPR = 3). The turbulence levels are lowest as the flow exits the nozzle and enters the enlarged duct at the corner. Subsequently, the energy increases and peaks just downstream of the rib, forming a moon-shaped concentration. This shape evolves as the duct length increases.

Figure 18(d) displays the turbulence kinetic energy contours for a duct with length L/D = 3 and a rib radius of 2.5 mm, positioned at L/D = 1 at a nozzle pressure ratio of five (NPR = 5). As the flow enters the enlarged duct at the corner after exiting the nozzle, the turbulence kinetic energy levels are at their lowest. Subsequently, the energy increases, reaching its peak immediately downstream of the rib. This high-energy area forms a moon-shaped zone, which expands as the NPR increases from 3 to 5.

Figure 18(e) illustrates the turbulence kinetic energy contours for a duct with a length-to-diameter ratio (L/D) of 4 and a rib radius of 2.5 mm. The rib is positioned at L/D = 1, under a nozzle pressure ratio (NPR) of 3. When the flow exits the nozzle and enters the duct at the corner, the turbulence levels are at their lowest. As the flow progresses, the energy increases, peaking just downstream of the rib and forming a moon-shaped concentration. The duct length causes a detectable change in the shape of these turbulence structures.

Figure 18(f) displays the turbulence kinetic energy contour for a duct length of L/D = 2 with a rib radius of 2.5 mm, positioned at L/D = 1, at a nozzle pressure ratio of five (NPR = 5). When the flow exits the nozzle and enters the enlarged duct at the corner, it exhibits the lowest levels of turbulence kinetic energy. Subsequently, the energy level rises and peaks just downstream of the rib. It concentrates into a moon-shaped form, which continues to expand as NPR increases from 3 to 5 and as the duct length grows.

Figure 18(g) shows the turbulence kinetic energy contour for a duct length L/D = 5, with a rib radius of 2.5 mm, when the rib is placed at L/D = 1 at a nozzle pressure ratio of three (i.e., NPR = 3). When the flow nozzle enters the enlarged duct after exiting at the corner, it initially has the lowest levels of turbulence kinetic energy. This is followed by a subsequent increase in energy that peaks immediately after the rib in the downstream direction. The formation of the moon-shaped object is visible, and downstream, there is a decrease in energy levels. Here, the duct length plays a crucial role.

Figure 18(h) shows the turbulence kinetic energy contour for a duct length L/D = 5, with a rib radius of 2.5 mm, when the rib is located at L/D = 1 at a nozzle pressure ratio of five (i.e., NPR = 5). When the flow exits the nozzle and enters the enlarged duct at the corner, it has the lowest values of turbulence kinetic energy levels. Later, the energy level increases and reaches its highest point just after the rib in the downstream direction. It becomes concentrated into a moon-shaped object, which continues to expand as the NPR increases from 3 to 5. The formation of the moon-shaped object is fading as the duct length increases. Here, the duct length plays a crucial role.

Figure 18(i) presents the turbulence kinetic energy contour for a duct length of L/D = 5, with a rib radius of 2.5 mm, positioned at L/D = 1 at a nozzle pressure ratio of 3 (NPR = 3). When the flow exits the nozzle and reaches the corner of the enlarged duct, it exhibits the lowest levels of turbulence kinetic energy. Subsequently, the energy increases, peaking just after the rib in the downstream direction. The formation of a moon-shaped pattern is evident, followed by a decrease in energy levels downstream. In this context, the length of the duct has a significant influence on the results.

Figure 18(j) displays the turbulence kinetic energy contour for a duct length L/D = 5, with a rib radius of 2.5 mm, positioned at L/D = 1 under a nozzle pressure ratio of five (NPR = 5). When the flow enters the enlarged duct after exiting the nozzle at the corner, the turbulence energy levels are at their lowest. As the flow progresses, the energy increases, reaching its peak immediately after the rib downstream. This energy concentrates into a moon-shaped form, which expands as the NPR increases from 3 to 5. The prominence of this moon-shaped formation diminishes with increasing duct length, highlighting its significant influence on the flow behavior.

Analysis for rib orientation 2

Figure 19 shows the rib’s orientation, with the flow exiting the nozzle striking the flat side of the rib. In contrast, the previous scenario involved the shear layer interacting with the rib’s curved surface. Consequently, the base pressure is likely higher than in the last case. This section focuses on orientation 2 of the rib, and all results will be presented based on this orientation.

Base pressure analysis for L/D = 1, orientation 2

Figure 20 displays the base pressure outcomes for orientation 2, where the flat face of the rib is oriented to face the shear layer. This data covers NPRs from 1.5 to 5 and includes rib radii of 1 mm, 1.5 mm, 2 mm, and 2.5 mm within a 16 mm duct. Overall, the data shows a downward trend; however, from NPR = 3 onward, this decline halts, and the base pressure ratio starts to increase, reaching 0.5 even without control measures. For quarter-rib radii of 1 mm, 1.5 mm, 2 mm, and 2.5 mm, the pattern closely resembles the uncontrolled case; however, the maximum base pressure ratios are 1.0, 1.45, 1.95, and 2.55, respectively. These findings imply that a rib with a 1 mm radius is enough to elevate the base pressure to atmospheric levels. Ultimately, these results serve as a technological demonstration, enabling users to make informed decisions based on their specific mission needs.

Base pressure analysis for L/D = 2, orientation 2

The results of this investigation for an enlarged duct length of 32 mm are shown in Fig. 21. It covers NPRs from 1.5 to 5, with rib radii of 1.5 mm and 2.5 mm, and the control positioned at L/D ratios of 0.5, 1.0, and 1.5. The control-free results align with earlier findings. Regarding the base pressure ratio, the data can be grouped into two categories based on rib radius, regardless of rib placement. The figure shows that for a 2.5 mm radius, the base pressure ratios at L/D ratios 0.5, 1.0, and 1.5 are 2.5, 2.95, and 3.09, respectively. For a 1.5 mm radius, placement at L/D = 0.5, 1, and 1.5 yields ratios of 1.4, 1.6, and 1.7, respectively. These results are for academic use, with final choices depending on the user’s specific mission needs.

Figure 22 shows the results for a 48 mm duct diameter, analyzing different expansion levels and rib radii of 1.5 mm and 2.5 mm. The ribs are positioned at L/D ratios of 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, and 2.0. The observed patterns resemble those from earlier base pressure results. For a 2.5 mm rib radius at various L/D ratios, the base pressure ratios are 2.5, 2.9, 3.0, and 3.0, respectively. In contrast, with the smaller 1.5 mm radius, the ratios are 1.4, 1.6, 1.7, and 1.7. That indicates that the smallest rib radius effectively reduces both base suction and base drag. Furthermore, the shorter reattachment length in smaller ducts reduces the control efficacy of the ribs, explaining this trend.

Base pressure analysis for L/D = 3, orientation 2

Base pressure analysis for L/D = 4, orientation 2

Figure 23 shows results similar to those with a smaller duct size, specifically the base pressure ratio at a duct length of 64 m while keeping all other parameters constant. Extending the duct improves flow stability, decreasing the small oscillations seen at shorter lengths, which disappear as the duct length grows.

Base pressure analysis for L/D = 5, orientation 2

Figure 24 shows the results of this study, where the duct length increases from 64 mm to 80 mm. All other parameters stay the same, except for the longer duct. This extension slightly raises the base pressure ratio. The longer duct affects the internal flow and the base pressure ratios, especially at lower nozzle pressure ratios. For shorter ducts, ambient pressure greatly influences both the base pressure ratio and the flow inside. When the L/D ratio reaches three or more, the oscillations seen in shorter ducts disappear. This pattern occurs because the reattachment point typically appears at an L/D ratio of approximately 1.

Base pressure analysis for L/D = 6, orientation 2

Figure 25 presents the base pressure consequences for the longest duct segment (L/D = 6). Because all inertial and geometric parameters are maintained, prolonging the duct influences the flow development inside it. That can lead to a smoother flow pattern and fewer oscillations during the flow formation process.

Pressure contours at 1D Location, orientation 2

Figure 26(a) depicts the pressure contour for a 32 mm duct with a rib radius of 2.5 mm at NPR = 3, employing passive control at L/D = 1. The figure highlights the flow expansion after exiting into the enlarged duct. Additionally, a low-pressure recirculation zone forms immediately downstream of the rib, resulting from the abrupt change in flow.

Figure 26(b) illustrates the pressure contour as the nozzle pressure ratio rises from 3 to 5, signifying a greater degree of under-expansion. This higher NPR causes the flow within the duct to expand further, as depicted in the figure.

Figure 26(c) illustrates the pressure contour with an increased duct length from 32 mm to 48 mm, while maintaining NPR at 3, a rib radius of r = 2.5 mm, and positioning the rib at L/D = 1. This figure illustrates the effect of the longer duct, which allows the flow to expand for a longer duration, resulting in lower pressure values.

Figure 26(d) displays the pressure contour at a higher NPR value of 5. Since all other parameters remain unchanged except for the increased NPR, the flow downstream of the rib can expand freely, as illustrated in the figure.

Velocity contours at 1D Location, orientation 2

Figure 27(a) shows the velocity contour for a 32 mm duct with a 2.5 mm rib radius, with control applied at L/D = 1. There is a sharp increase in velocity near the rib, leading to the formation of a Mach disk. Further downstream, the velocity decreases as the flow expands.

Figure 27(b) displays the velocity contours for a similar case to that in Fig. 27(a), where the NPR was three. In this instance, the NPR has increased from 3 to 5. As a result of the higher NPR, a larger Mach disk forms and persists over a longer distance.

Figure 27(c) shows similar results, with all parameters unchanged except for the duct length. The increased duct length causes the flow to expand over a more extended portion of the duct.

Figure 27(d) presents results similar to those in Fig. 27(b), with all variables unchanged except for a longer duct length. This increased length causes the flow inside the duct to expand further, reducing the velocity.

Streamline contours at 1D Location, orientation 2

(a) Streamline contour for L/D = 2, 2.5 mm rib, at 1D location and NPR = 3. (b) Streamline contour for L/D = 2, 2.5 mm rib, at 1D location and NPR = 5. (c) Streamline contour for L/D = 3, 2.5 mm rib, at 1D location and NPR = 3. (d) Streamline contour for L/D = 3, 2.5 mm rib, at 1D location and NPR = 5.

Figure 28(a) illustrates the streamline for a duct with a diameter of 32 mm, a rib radius r = 2.5 mm, and positioned at L/D = 1, which corresponds to the nozzle pressure ratio. The figure shows that just after exiting the converging nozzle, the streamlines begin to expand and form a compression front near the rib. Additionally, recirculation zones appear at the two corners, where the flow circulates and generates suction.

Figure 28(b) displays results similar to those in the previous figure’s streamline contour. As the nozzle pressure ratio rises and inertia levels increase, the Mach disc formation near the rib becomes more pronounced.

Figure 28(c) displays the streamline contour for a longer duct length, from L/D = 2 to 3. With all other parameters held constant, increasing the duct length helps the flow sustain itself and expand more within the duct.

Figure 28(d) illustrates the streamline contour results with a longer duct length and a higher nozzle pressure ratio. The increased flow inertia causes the Mach disk to become stronger, and its effects extend further downstream.

Temperature contours at 1D Location, orientation 2

(a)Temperature contour for L/D = 2, 2.5 mm rib, at 1D location and NPR = 3. (b) Temperature contour for L/D = 2, 2.5 mm rib, at 1D location and NPR = 5. (c) Temperature contour for L/D = 3, 2.5 mm rib, at 1D location and NPR = 3. (d) Temperature contour for L/D = 3, 2.5 mm rib, at 1D location and NPR = 5.

Figure 29(a) illustrates the temperature distribution for a duct length of 32 mm and a rib radius of 2.5 mm, maintained at L/D = 1 with a nozzle pressure ratio (NPR) of 3. It shows that after exiting the nozzle, the flow expands into a larger area, leading to lower temperatures near the duct wall. Just beyond the rib, a D-shaped low-temperature zone appears, which was anticipated due to the favorable pressure conditions affecting the nozzle.

Figure 29(b) displays results similar to those in Fig. 29(a). The main difference is that NPR has risen from 3 to 5, indicating a higher degree of under-expansion at the nozzle. This under-expansion is clearly evident in the more pronounced low-temperature formation that occurs downstream of the rib.

Figure 29(c) shows similar results to those seen in Fig. 29(a), except that the duct length is increased from L/D = 2 to 3. This increased length of the rib will allow for further reduction in the temperature.

Figure 29(d) displays the temperature contour for a longer duct length of 48 mm. With the higher NPR of 2.5, the level of expansion has increased. Consequently, the NPR in the low-temperature region has risen as expected.

Turbulence kinetic energy contours at 1D Location, orientation 2

(a) Turbulence Kinetic Energycontour for L/D = 2, 2.5 mm rib, at L/D = 1, NPR = 3. (b) Turbulence Kinetic Energy for L/D = 2, 2.5 mm rib, at 1D location and NPR = 5. (c) Turbulence Kinetic Energyfor L/D = 3, 2.5 mm rib, at 1D location and NPR = 3. (d) Turbulence Kinetic Energy for L/D = 3, 2.5 mm rib, at 1D location and NPR = 5.

Figure 30(a) displays the turbulence kinetic energy contour for a 32 mm long duct with a 2.5 mm rib radius, positioned at L/D = 1, at a nozzle pressure ratio (NPR) of 3. From the image, it is clear that turbulence kinetic energy remains low within the converging nozzle. As the flow exits, small pockets of low turbulence energy appear at the two corners of the exit. Further downstream, turbulence kinetic energy gradually increases. Just after the rib, a ring of turbulence kinetic energy forms, which then disperses as it moves further along.

Figure 30(b) presents results similar to those in Fig. 30(a). The main difference is that in this case, the nozzle pressure ratio (NPR) increases from 3 to 5. This higher NPR causes further flow expansion, resulting in greater diffusion of turbulent kinetic energy, which is consistent with the expected behavior.

Figure 30(c) depicts the turbulence kinetic energy contour for a duct length of 48 mm, with a rib radius of 2.5 mm positioned at L/D = 1, at a nozzle pressure ratio NPR = 3. The figure clearly shows that increasing the duct length causes further diffusion of the turbulent kinetic energy, although the size of the turbulent energy ring remains the same.

Figure 30(d) displays the turbulent kinetic energy results for a longer duct length and an increased nozzle pressure ratio from NPR = 3 to 5. The figure shows that the initially minor ring of turbulence kinetic energy has expanded further as the NPR has increased.

Conclusions

This study examines the passive technique of monitoring base pressure at sonic Mach numbers with an area ratio of 2.56, using quarter ribs. It analyzes how rib size, placement, nozzle pressure ratio (NPR), and rib orientation affect the outcomes. Results show that adding ribs significantly impacts shear layer interactions, leading to changes in base pressure depending on rib size, location, and angle. A rib with a 1 mm radius can boost base pressure by 120%, matching the back pressure. A 2 mm rib can raise it by 140%, making it suitable for applications needing a base pressure 65% higher than ambient. Furthermore, passive control is highly effective in decreasing suction in the recirculation zone when a 2.5 mm rib is placed at 1.5D or 2D.

Analysis of pressure, velocity, temperature, streamlines, and turbulent kinetic energy indicates that longer ducts and higher nozzle pressure cause the flow to expand more, leading to greater energy diffusion.

Additionally, the position of the rib significantly impacts how the base pressure recovers. A notable increase in base pressure occurs at 1D for both orientations; however, the maximum recovery is observed at 1.5D in orientation two, with the recovery remaining nearly unchanged at 2D. Orientation 2 significantly enhances pressure recovery by adjusting the rib orientation to allow flow to interact with the flat surface, resulting in a marked change in base pressure. This adjustment results in a base pressure increase of 12.7% for the 2.5 mm rib, 7.7% for the 2 mm rib, 16% for the 1.5 mm rib, and 9.1% for the 1 mm rib.

The study further confirms that changing the duct length doesn’t significantly affect base pressure trends, emphasizing that the key factors influencing flow behavior are the rib’s geometry and its interaction with the shear layer. Nevertheless, at L = 0.5D, flow oscillations occur because of its proximity to the nozzle exit, where the shear layer transitions before reattaching stably. Ultimately, these findings underscore the importance of selecting the optimal parameter combination to achieve specific mission objectives.

Future studies can focus on enhancing accuracy by implementing advanced turbulence models to more accurately predict flow separation and vortex dynamics. Moreover, exploring hybrid control strategies that combine passive methods with active techniques, such as micro-jets or plasma actuators, could further enhance pressure recovery and reduce drag, leading to more efficient aerodynamic systems. Machine learning techniques can be utilized to optimize rib configurations and predict base pressure variations under different conditions.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Khan, A., Rajendran, P., Sidhu, J. S. S. & Sharifpur, M. Experimental investigation of suddenly expanded flow at Sonic and supersonic Mach numbers using semi-circular ribs: a comparative study between experimental, single-layer, deep neural network (SLNN and DNN) models. Eur. Phys. J. Plus. 138 (4), 314. https://doi.org/10.1140/epjp/s13360-023-03853-1 (2023).

Aabid, A., Khan, S. A. & Baig, M. A critical review of supersonic flow control for high-speed applications. In Applied Sciences (Switzerland) 11 (15) MDPI AG. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11156899 (2021).

Khan, A., Aabid, A., Khan, S. A., Akhtar, M. N. & Baig, M. Comprehensive CFD analysis of base pressure control using quarter ribs in a sudden expansion duct at Sonic Mach numbers. Int. J. Thermofluids. 24, 100908. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.IJFT.2024.100908 (2024).

Khan, A., Khan, S. A., Akhtar, M. N., Aabid, A. & Baig, M. Base pressure control with Semi-Circular ribs at critical Mach number. Fluid Dynamics Mater. Process. 20 (9), 2007–2028. https://doi.org/10.32604/FDMP.2024.049368 (2024).

Khan, A., Khan, S. A., Raja, V., Aabid, A. & Baig, M. Effect of ribs in a suddenly expanded flow at Sonic Mach number. Heliyon 10 (9), e30313. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.HELIYON.2024.E30313 (2024).

Vermeersch, O. & Bouteiller, X. Numerical study of laminar nacelles: natural and hybrid laminar flow designs. Int. J. Eng. Syst. Modelling Simul. 48 (3–4), 191–204 (2014).

Mariotti, A., Buresti, G. & Salvetti, M. V. Connection between base drag, separating boundary layer characteristics, and wake mean recirculation length of an axisymmetric blunt-based body. J. Fluids Struct. 55, 191–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JFLUIDSTRUCTS.2015.02.012 (2015).

Sethuraman, V. & Khan, S. A. Effect of sudden expansion for varied area ratios at subsonic and Sonic flow regimes. Int. J. Energy Environ. Econ. 24 (1), 99 (2016).

Khan, A., Musfirah Mazlan, N. & Azmi Ismail, M. Analysis of flow through A convergent nozzle at Sonic Mach number for area ratio 4. J. Adv. Res. Fluid Mech. Therm. Sci. J. Homepage. 62, 66–79 (2019). www.akademiabaru.com/arfmts.html

Thakur, M., Asadullah, S., Khan & Asrar, W. Low-Cost base drag reduction technique. Int. J. Mech. Eng. Rob. Res. 7 https://doi.org/10.18178/ijmerr.7.4.428-432 (2018).

Sethuraman, V., Rajendran, P. & Khan, S. A. Base and wall pressure control using cavities and ribs in suddenly expanded flows: an overview. J. Adv. Res. Fluid Mech. Therm. Sci. J. Homepage. 66, 120–134 (2020). www.akademiabaru.com/arfmts.html

Nur Aqilah, K. A., Pathan & Sher Afghan Khan Passive control of base flow at supersonic Mach number for area ratio 4. Lecture Notes Mech. Eng. 37–50. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-7213-5_4 (2024).

Fiqri, M. I., Pathan, K. A. & Sher Afghan Khan Control of Suddenly Expanded Flow with Cavity at Sonic Mach Number. In Lecture Notes in Mechanical Engineering, 3–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-7213-5_1 (2024).

Pathan, K. A., Dabeer, P. & Khan, S. A. Enlarge duct length optimization for suddenly expanded flows. Adv. Aircr. Spacecr. Spacecr. Sci. 7 (3), 203–214. https://doi.org/10.12989/aas.2020.7.3.203 (2020).

Pathan, K., Ahmed, P. S., Dabeer & Sher Afghan Khan Influence of expansion level on base pressure and reattachment length. CFD Lett. 11 (5), 22–36 (2019).

Azami, M., Faheem, M., Aabid, A., Mokashi, I. & Sher Khan Inspection of supersonic flows in a CD nozzle using experimental method. Int. J. Recent. Technol. Eng. 8, 996–999. https://doi.org/10.35940/ijrte.B1186.0782S319 (2019).

Pathan, K. A., Prakash, S., Dabeer & Sher Afghan Khan Optimization of nozzle design for weight reduction using variable wall thickness. J. Adv. Res. Fluid Mech. Therm. Sci. 112 (2), 86–101. https://doi.org/10.37934/arfmts.112.2.86101 (2023).

Azami, M., Faheem, M., Aabid, A., Mokashi, I. & Sher Khan Experimental research of wall pressure distribution and effect of micro jet at Mach 1.5. Int. J. Recent. Technol. Eng. 8, 1000–1003. https://doi.org/10.35940/ijrte.B1187.0782S319 (2019).

Khan, S., Aabid, A. & Ahamed, S. C. Influence of micro jets on the flow development in the enlarged duct at supersonic Mach number. Int. J. Mech. Mechatronics Eng. 19, 70–82 (2019).

Bashir, M., Rajendran, P., Khan, A., Raja, V. & Khan, S. A. Numerical investigation of turbulence models with emphasis on turbulent intensity at low Reynolds number flows. Adv. Aircr. Spacecr. Sci. 10 (4), 303–315. https://doi.org/10.12989/aas.2023.10.4.303 (2023).

Baig, M. A. A., Khan, S. A., Al-Mufadi, F. & Rathakrishnan, E. Control of base flows with micro jets. Int. J. Turbo Jet. Engines. 28 (1), 59–69. https://doi.org/10.1515/tjj.2011.009 (2011).

Rehman, S. & Khan, S. A. Control of base pressure with micro-jets: part I. Aircr. Eng. Aerosp. Technol. 80 (2), 158–164. https://doi.org/10.1108/00022660810859373 (2008).

Faheem, M., Afghan Khan, S., Asrar, W., Khan, A. & Kumar, R. Experimental study on the mean flow characteristics of a supersonic multiple jet configuration. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 108, 106377. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ast.2020.106377 (2021).

Sajali, M. F. M., Aabid, A., Khan, S. A., Sulaeman, E. & Mehaboobali, F. A. G. Numerical investigation of the flow field of a non-circular cylinder. CFD Lett. 11 (5), 37–49 (2019). https://www.akademiabaru.com/submit/index.php/cfdl/article/view/3161

Khan, S. A., Asadullah, M., Fharukh Ahmed, G. M., Jalaluddeen, A. & Ali Baig, M. A. Passive control of base drag in compressible subsonic flow using multiple cavities. Int. J. Mech. Prod. Eng. Res. Dev. 8 (4), 39–44. https://doi.org/10.24247/ijmperdaug20185 (2018).

Bellary, S. A. I., Khan, A., Akhtar, M. N., Khan, S. A. & Pathan, K. A. Numerical simulations of base pressure and its control in a suddenly expanded duct at Mach 1.6 using quarter circular ribs. J. Adv. Res. Fluid Mech. Therm. Sci. 127 (2), 203–233. https://doi.org/10.37934/arfmts.127.2.203233 (2025).

Bellary, S. A. I., Dabir, S. A., Shaikh, J. H., Tamhane, T. & Khan, S. A. Computational analysis of thrust generated by a converging-diverging nozzle at different diverging angles. J. Adv. Res. Numer. Heat. Transf. 29 (1), 102–128. https://doi.org/10.37934/arnht.29.1.102128 (2025).

Makwana, M. B., Bellary, S. A. I., Khan, S. A., Aabid, A. & Baig, M. Passive control of Sonic flow from Converging nozzle with D-shaped Rib Results in Engineering Volume 26, June 2025, 105061. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rineng.2025.105061 (2025).

Rathakrishnan, E. Effect of ribs on suddenly expanded flows, AIAA Journal 39 (7), 1402–1404, 2001. https://doi.org/10.2514/2.1461 (2001).

Funding

Open access funding provided by Symbiosis International (Deemed University).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Shahid Tamboli: Writing – Review, Investigation & SupervisionSayed Ahmed Imran Bellary: Writing, Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis & InvestigationRoslinda Abdullah: Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draftRenita Sharon Monis: Writing – review, Investigation & SupervisionSher Afghan Khan: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis & SupervisionVijaykumar S Jatti: Conceptualization & MethodologyAjit Madhukarrao Kate: Writing – review, Investigation & SupervisionYogesh Ramesh Ingole: Writing – review, editing & SupervisionShaikh Sarfaraj Jilani: Writing – review, editing & Supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tamboli, S., Bellary, S.A.I., Abdullah, R. et al. Passive control of suddenly expanded flow and temperature distribution along the duct at critical Mach number. Sci Rep 16, 712 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30273-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30273-1