Abstract

The WHO warns that over 1.1 billion young people are at risk of hearing loss due to unsafe listening practices, particularly in recreational settings. While traditional studies have focused on changes in hearing sensitivity, typically assessed through standard audiometry, emerging research reveals that noise exposure can also damage cochlear synapses without affecting outer hair cells (OHCs). This “hidden” damage, known as cochlear synaptopathy (CS), impairs the reliable processing of audible sound in complex listening environments while having little or no effect on the traditional measure of hearing sensitivity such as the audiogram. This study offers a unique longitudinal investigation of the relationship between recreational noise exposure and both audiometric and hidden hearing changes, combining personal dosimetry with standard audiometry and physiological markers including otoacoustic emissions and auditory-evoked potentials (AEPs). Forty-two young adults were monitored before and after large-scale music events, with average sound exposure reaching 100 ± 4 dBA over 10.3 ± 4.8 h. Only one participant showed a clinically significant decline in hearing sensitivity, yet five showed acute reductions in AEP markers of synaptic damage within 24 h post-exposure. Two of these cases persisted for 14 days, despite normal audiometric thresholds. No correlation was found between exposure levels and damage, suggesting that individual susceptibility is important. These findings emphasize the limitations of standard hearing sensitivity measures and highlight the need for early diagnostic tests that can detect subclinical, or hidden damage. They call for protective strategies and revised monitoring practices that account for real-life variability in personal exposure and auditory vulnerability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Exposure to high-level amplified music at recreational events has become a growing public health concern1, with attendees often exposed to sound pressure levels averaging 90 dBA or more for prolonged periods2,3,4. These exposure levels are known to cause noise induced hearing loss (NIHL)1,5,6,7,8,9,10,11, a risk now widely acknowledged by public health authorities12. Despite these well-established risks, awareness among young people remains limited 13,14,15,16, and the majority of attendees at such events do not use hearing protection17. Consequently, a substantial proportion of young adults (36–86%) report experiencing acute auditory symptoms such as aural dullness or tinnitus following exposure17,18,19,20,21.

Traditionally, NIHL has been attributed to damage within the cochlea, including the outer hair cells (OHCs), supporting cells, and metabolic changes that can lead to cellular degeneration and cell death22,23,24,25. Such damage impairs hearing sensitivity, typically resulting in either temporary hearing threshold shifts (TTSs) or permanent threshold shifts (PTSs), as measured using pure-tone audiometry22. While TTS by definition resolves within minutes to weeks26,27,28, PTS reflects irreversible sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL). Hearing sensitivity is typically assessed behaviorally using (extended-high-frequency) pure-tone audiometry. Additionally, distortion-product otoacoustic emissions (DPOAEs) provide a physiological measure of OHC integrity: DPOAEs are low-level sounds generated by the OHCs in the cochlea in response to pairs of pure tones. They are recorded in the ear canal using a sensitive microphone and their presence and size reflect the health of OHCs in the frequency region corresponding to the evoking tones. However, growing evidence suggests that noise exposure can also lead to a more subtle form of auditory damage that occurs while hearing sensitivity or outer hair cell integrity remains unaffected29. This condition, referred to as cochlear synaptopathy (CS), involves the loss or dysfunction of synapses connecting the inner hair cells (IHCs) to auditory nerve fibers (ANFs), and occurs earlier than OHC or IHC damage in the progression of noise-or age-related SNHL30,31. Unlike OHC damage, CS does not affect hearing thresholds unless it is extreme and is therefore undetectable using standard audiometry and DPOAEs32,33,34. Instead, CS disrupts the robust neural transmission of sound, leading to difficulties in auditory processing, particularly in noisy or complex acoustic environments, hence the term “hidden hearing disorder”35. Current hearing protection guidelines and legislation predominantly focus on preventing OHC-related threshold shifts, thereby overlooking the risk of CS as an early and potentially irreversible marker of noise-induced SNHL. Given that CS has been observed following noise exposure even in the absence of OHC damage30,36, it is critical to examine whether recreational noise exposure in humans affects auditory evoked potential (AEP) markers of CS. This raises an important question for public health policy: should existing legislation be revised to include the prevention of CS as the earliest sign of permanent SNHL?

While CS can be identified post-mortem through histological examinations in rodents and humans37, indirect markers, such as the wave I amplitude of the Auditory Brainstem Response (ABR) and the magnitude of the Envelope Following Response (EFR), are used to assess CS in living humans38,39. These AEP markers were first validated in animal models, where reductions in ABR wave I amplitudes and EFR magnitudes showed strong correlations with histologically confirmed synaptic loss30,32. Although several research groups have explored the relationship between risk factors for CS and these AEP markers in humans40,41,42,43,44,45,46, findings remain inconclusive regarding the presence and significance of CS following noise exposure. Methodological challenges, including the sensitivity of AEP markers, the confounding effects of coexisting forms of SNHL, and the lack of carefully monitored sound exposure measurements, contribute to these inconsistencies47.

To address these gaps, this study investigates the contribution of recreational noise exposure to CS through a novel, multi-disciplinary approach. We combined conventional clinical assessments of hearing sensitivity with the latest AEP-based measures of CS to monitor hearing health in the days surrounding the music events. The voluntary noise exposure of 42 participants was monitored individually during extended large-scale music festivals (mean exposure of 10.3 h) while their hearing health was evaluated one day before and minimally twice after the event. Our methodology integrated standard clinical evaluations with physiological markers sensitive to early signs of OHC-damage (otoacoustic emissions) and CS (AEP), complemented by questions related to auditory symptoms, and attitudes towards noise and hearing protection. The investigation specifically assessed whether attendance at large-scale music events was associated with measurable changes in auditory function, including early indicators of CS, and further examined the relationship of such changes with individual exposure metrics. By integrating objective noise-exposure data with self-reported auditory symptoms, baseline hearing status, and attitudes toward hearing protection, the study provides a comprehensive and rigorous characterization of the auditory risks associated with high-level recreational noise exposure.

Results

Pre-exposure participant characteristics

Among the 42 participants, 50% had previously experienced temporary tinnitus following noise exposure at music events, although none reported symptoms of hyperacusis, a condition where moderately intense sounds are aversive and painful. Subjective hearing loss following exposure was reported by 10 participants (24%), while 16 participants (38%) experienced auditory dullness. In terms of hearing protection device (HPD) usage, 6 participants (14%) used custom earplugs, 5 (12%) universal party plugs, and 10 (24%) foam earplugs. Notably, 21 participants (50%) reported not using any form of hearing protection during music events.

Audiological assessments at baseline revealed a clear pattern of reduced auditory function among participants who did not use hearing protection (Fig. 1).

Baseline Audiological and Electrophysiological Measures. (A) Pure-tone audiograms showing mean thresholds with 95%CIs across octave frequencies for participants with (white symbols) and without (grey symbols) hearing protection. Those without protection exhibited elevated thresholds across the tested range. (B) DPOAE amplitudes with 95%CIs at primary frequencies from 0.5 to 11 kHz, with the unprotected group showing reduced emission levels. (C) Electrophysiological responses: Auditory Brainstem Response (ABR) wave I and V amplitudes elicited by 80 µs clicks, and Envelope Following Response (EFR) magnitudes evoked by 6 kHz rectangular amplitude-modulated stimuli (110 Hz modulation, 2 Hz rate, 25% duty). Participants without hearing protection exhibited smaller ABR wave V amplitudes and lower EFR magnitudes.

This group showed higher PTA thresholds, lower DPOAE amplitudes, and reduced ABR and EFR sizes. Independent t-tests confirmed that pure-tone thresholds were significantly higher for the unprotected group at several frequencies: 1 kHz [t(40 = 2.373, p = 0.011)], 2 kHz [t(40 = 2.559, p = 0.007)], 3 kHz [t(40 = 1.808, p = 0.039)], and 4 kHz [t(37 = 1.796, p = 0.040)] (Fig. 1A). Consistent with these findings, DPOAE amplitudes were significantly lower at 1.5 kHz [t(40 = − 1.784, p = 0.041)], 2 kHz [t(40 = − 2.926, p = 0.003)], 3 kHz [t(40 = − 2.529, p = 0.008)], and 4 kHz [t(37 = 1.796, p = 0.040)] (Fig. 1A). Significant group differences were also evident in ABR and EFR measures. The unprotected group showed significantly smaller peak V amplitudes in response to 70 dBpeSPL click stimuli [t(40) = − 2.022, p = 0.025)], along with prolonged peak V latencies at both 70 [t(40 = 3.093, p = 0.002) and 80 dBpeSPL [t(40 = 2.803, p = 0.004)]. EFR magnitudes for the unprotected group were significantly lower at 6 kHz [t(28) = − 1.887, p = 0.035)] (Fig. 1C). Collectively, these findings indicate that young individuals who do not use hearing protection in high-noise environments are more likely to exhibit early indicators of auditory dysfunction than those who do use hearing protection, as evidenced by both behavioral thresholds shifts and objective physiological measures of hearing health.

The mean total score was 2.70 (SD = 0.46, range: 1.89–3.68) for the Youth Attitudes to Noise Scale (YANS), which measures attitudes toward noise, and 2.49 (SD = 0.44, range: 1.46–3.25) for the Beliefs About Hearing Protection and Hearing Loss (BAHPHL), which assesses beliefs about hearing protection and hearing loss. Both instruments use 5-point Likert scales, with higher scores reflecting more positive attitudes and beliefs toward noise. In this context ‘higher’ scores reflect reduced concerns about hearing damage and lower perceived need for hearing protection, whereas ‘lower’ scores (in terms of health behavior) reflect greater alignment with preventive attitudes and behaviors. Independent-samples t-tests revealed significant differences in total YANS scores between the HPD-protected and non-protected groups [t(40) = 3.835, p < 0.001], with HPD users showing more favorable attitudes toward noise exposure management. Significant differences were also observed across YANS subdomains, including ‘youth culture’ (reflecting attitudes shaped by social and recreational norms) [t(40) = 5.128, p < 0.001] and ‘influence noise’ (perceptions of the impact of environmental noise) [t(40) = 2.806, p = 0.004], indicating better scores among HPD users. Similarly, the protected group had significantly higher scores on the total BAHPHL measure [t(40) = 3.349, p < 0.001)], as well as higher scores on several subdomains, including ‘barriers’ (perceived obstacles to using hearing protection) [t(30) = 2.483, p = 0.009)], ‘susceptibility of hearing loss’ (perceived personal risk) [t(40) = 2.908, p = 0.003)], ‘severity of hearing loss’ (perceived seriousness of potential damage) [t(37) = 1.808, p = 0.039)], ‘benefits of preventive actions’ (perceived effectiveness of protective measures) [t(40) = 2.646, p = 0.006)], and ‘behavioral’ (actual use and consistency of protective behaviors) [t(40) = 3.751, p < 0.001)]. Together, the results underscore how personal attitudes and beliefs about noise exposure and hearing protection need to be considered when implementing preventive health practices.

Noise exposure characteristics

Figure 2 presents boxplots of uncompensated LAeq and LCeq sound pressure levels recorded across six monitored music festivals (F1-F6), illustrating the personal noise-exposure distribution across the music events. These measurements represent personal exposure levels and may differ substantially from those recorded at the public address (PA) system, which is typically centrally located within the audience area. While PA system levels are commonly used as reference points for regulatory compliance, they do not capture the variability in individual exposure influenced by factors such as location within the venue and attendee behavior. For reference, the dashed lines in Fig. 2 denote two key regulatory benchmarks: the Belgian maximum permissible exposure limit of 102 dBA,15 min, and the WHO recommended safe listening limit of 100 dBA,15 min (WHO, lim) (ISO 1999). Although sound levels varied across events due to differences in music programming and attendee behavior (e.g., quieter musical segments, stage proximity), overall exposure levels were consistently high. To remain within the WHO’s safe listening guidelines, most participants would have required the use of hearing protection; however, only half reported using it.

Boxplots representing the distribution of LAeq (dark blue), LCeq (light blue), and LZeq, 63Hz (dark green) across 42 participants, covering the full exposure period at six festivals (F1-F6). The dashed lines represent the Belgian regulatory limit of 102 dBA (15 min) and the WHO safe listening limit of 100 dBA (15 min) (WHOlim).

Table 1 summarizes the mean and standard deviation values across events of LAeq (reported both with and without allowing for the effect of the HPD), LCeq, and LZeq, 63 Hz, together with the frequency with which the Belgian or WHO noise exposure limits were exceeded. Across events, average LAeq values ranged from 85 to 105 dBA (non-compensated) and 74 to 105 dBA (compensated, i.e., adjusted for the frequency-specific attenuation provided by the worn HPDs), while mean LCeq varied between 97 and 118 dBC. Low-frequency LZeq, 63 Hz levels, a parameter typically excluded from safe-listening guidelines, ranged from 95 to 120 dBZ2. LC-peak values were particularly elevated, ranging from 134 to 144 dBC, often reaching the saturation threshold of the recording devices (144 dBC).

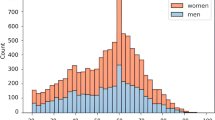

As shown in Fig. 3, participants spent 40% of their total event time in environments where noise levels exceeded the WHO’s 15-min threshold of 100 dBA. When adjusted for equivalent continuous exposure, 56% of attendees were exposed to an LAeq above 100 dBA. Additionally, the distribution of exposure levels was clearly skewed, indicating a non-normal distribution close to a general extreme value (GEV) distribution. Independent-sample t-tests revealed that male participants experienced significantly longer exposure durations [t(24) = − 3.46, p < 0.001] and higher LAeq levels [t(37) = − 3.25, p = 0.001] than female participants, and exceeded the WHO guideline more frequently [t(25) = − 3.09, p = 0.002].

Distribution of sound exposure levels among participants. (a) 15-min equivalent continuous sound levels (LAeq,15 min) presented in 1-dB bins. (b) Full-duration equivalent continuous sound levels (LAeq) for the entire festival exposure, also in 1-dB bins. Red shading denotes values exceeding the WHO recommended exposure limit of 100 dBA, while green bars indicate values at or below this threshold. Percentages in the legend (≤ WHO 60% in a; ≤ WHO 44% in b) represent the proportion of measurements that remained below the WHO guideline. Dashed black lines depict a Generalized Extreme Value (GEV) fit to the distributions, and the dotted red line marks the WHO threshold.

Sound exposure characteristics for event F3 were atypical due to substantial rainfall, which shortened the duration of exposure as participants sought shelter. Additionally, thin plastic bags (0.03 mm thickness) were used to protect the microphones of the dosimeters from water damage during rainfall at that event. An acoustic evaluation indicated that this led to a 5-dB attenuation in the highest frequency bands, corresponding to a maximal underestimation of 0.35 dBA in LAeq. Due to technical malfunctions with the dosimeters, one recording from events F3, F5, and F6 was excluded from the final analyses.

The effect of noise exposure on hearing health parameters

Hearing-related symptoms

One day after the music events, 25 out of 41 participants (61%) reported hearing-related symptoms, including sensation of aural dullness (11 males, 24%, and 4 females, 10%), subjective hearing loss (5 males, 12%, and 3 females, 7%), and/or tinnitus (10 males, 24%, and 5 females, 12%). By day 3 post-exposure, all symptoms had resolved.

Group-level changes in hearing parameters following noise exposure

Measures of hearing sensitivity

At baseline, the mean pure-tone average threshold was 4.5 dB HL (SD = 4.1, range: − 5.0 to 15.0) for the average across 3, 4, 6 and 8 kHz (PTA3-8 kHz) and 10.2 dB HL (SD = 10.7, range: − 13.8 to 31.4) for the average across 10, 12, 14 and 16 kHz (PTA10-16 kHz). Figure 4A–C present boxplots of hearing thresholds and DPOAE amplitudes before and at various times after exposure. They reveal no clear group-level changes in hearing threshold. This was supported by a one-way repeated-measures ANOVA, which showed no effect of measurement session on PTAs, individual pure-tone thresholds, or DPOAE amplitudes. However, when stratified by individual music event (Fig. 5A–C), there were trends suggesting differential effects of noise exposure depending on the event.

Boxplots illustrating various auditory metrics across four time points: Pre-exposure, 1 day post-exposure, 3 days post-exposure, and 14 days post-exposure. Panels (A) and (B) represent OSHA-defined pure-tone averages and 6-kHz auditory thresholds, respectively. Panel (C) shows DPOAE amplitudes at 8 kHz, while panel (D) presents ABR wave I amplitudes in response to an 80 dB peSPL click stimulus. Panels (E) and (F) display EFR strengths at 4 kHz and 6 kHz, respectively. The data reveal individual- and group-level trends, illustrating changes in auditory function over time across participants.

Boxplots showing values of a range of auditory metrics across six festival events (F1–F6), measured prior to exposure (dark blue) and on the first day post-exposure (light blue). Panels (A) and (B) show pure-tone averages and 6-kHz auditory thresholds, respectively. Panel (C) shows DPOAE amplitudes at 8 kHz, while panel (D) presents ABR wave I amplitudes in response to an 80 dB peSPL click stimulus. Panels (E) and (F) display EFR strengths at 4 kHz and 6 kHz, respectively. These data allow group-level assessment of temporal changes in auditory function associated with festival exposure.

AEP-based measures of cochlear synaptopathy

Figures 4D–F show group-level changes in ABR and EFR magnitudes before and after exposure. In line with the behavioral and otoacoustic findings, repeated-measures ANOVA showed no significant effect of measurement session on suprathreshold ABR amplitudes, latencies, or EFR magnitudes. Again, however, when analyzed for each music festival separately (Fig. 5D–F), subtle trends were observed, suggesting that the effects of noise exposure may vary across events.

Detailed F-statistics and descriptive data are provided in Appendix 1 (Supplementary material).

Individual changes in hearing parameters following noise exposure

For a subset of participants, an additional evaluation was conducted on day 14 if the audiologist observed clear reductions in any of the measurements—most often evident in the EFR marker—indicating possible persistent hearing effects. Results for these participants are shown for each session in Fig. 6A–F. It is important to note that not all participants with significant reductions were willing to return for the 14-day follow-up.

Individual data points from participants who underwent an additional measurement on day 14, showing various auditory metrics across four time points: Pre-exposure, 1 day post-exposure, 3 days post-exposure, and 14 days post-exposure. Gray and white symbols denote non-protected and protected festival attendees, respectively. Panels (A) and (B) represent OSHA-defined pure-tone averages and 6-kHz auditory thresholds. Panel (C) shows DPOAE amplitudes at 8 kHz, while panel (D) presents ABR wave I amplitudes in response to an 80 dB peSPL click stimulus. Panels (E) and (F) display EFR strengths at 4 kHz and 6 kHz, respectively. The data show individual auditory function trajectories over time for these participants.

Although measures of hearing sensitivity and suprathreshold ABR amplitudes did not exhibit consistent changes, panels 6E and 6F revealed a clear trend of reduced EFR markers following the noise exposure, suggesting that temporary or permanent synaptopathy may have occurred as a result of the event.

To further explore individual variability in hearing outcomes following noise exposure, the effects of exposure level and HPD use were assessed. Figure 7A–F present individual outcomes for several hearing measures on day 1 post-exposure. Grey markers represent participants who did not use hearing protection and white markers indicating those who did. The x-axis shows average noise exposure levels (dBAeq), adjusted for the use of HPDs. Figure 7A represents temporary threshold shifts (TTSs) at 2–4 kHz as defined by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), which sets regulatory standards for workplace noise exposure. A clinically significant TTS is defined as a threshold shift ≥ 10 dB, as indicated by the red line. Only one individual exhibited an OSHA-defined TTS on day 1 post-exposure. That individual fell within the highest exposure range and did not use HPDs. Figure 7B shows more pronounced individual TTS values at higher frequencies (> 6 kHz), with clinically significant TTSs (≥ 10 dB) for multiple participants: two at 1 kHz, two at 2 kHz, two at 4 kHz, six at 6 kHz, three at 8 kHz, two at 10 kHz, three at 12.5 kHz, three at 14 kHz, four at 16 kHz, and two at 20 kHz.

Individual auditory changes on day 1 post-exposure for various hearing parameters, plotted as a function of hearing protection device-compensated total exposure level (LAeq, comp). Gray and white symbols denote non-protected and protected festival attendees, respectively. Panels A and B illustrate temporary threshold shifts (TTS) at OSHA-defined frequencies (2–4 kHz) and 6 kHz, the red line indicating a clinically significant TTS of 10 dB. Panels C, D, E, and F depict the deterioration in DPOAE 8 kHz amplitudes, click-ABR (80 dB peSPL) wave I amplitudes, and EFR magnitudes at 4 kHz and 6 kHz, respectively. The shaded areas represent mean 95% confidence intervals (CIs) from a test–retest study with 15 participants50, while in D, E and F, additional dashed lines delineate the overall CI, capturing the average range alongside the 95%CI at each individual data point, derived from individual standard deviations obtained through a resampling bootstrapping method49.

DPOAE amplitudes (Fig. 7C), which reflect OHC function, did not show consistent deterioration. The grey-shaded area in the figure represents the 95% confidence interval (CI) for the general test–retest variability of DPOAE amplitudes, based on a longitudinal study of 15 participants assessed three times over a 1–5 day period without noise exposure48.

Similarly, Fig. 7D presents ABR wave I amplitude changes before and after the event and reveals no consistent post-exposure trend. For each participant, 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated using a bootstrap resampling procedure to account for within-subject variability49 (Fig. 9). Changes were considered significant if the individual CI did not overlap with the zero line. To further assess the significance of observed changes, the grey dashed lines represent the 95% CI of test–retest variability derived from a separate reference cohort (n = 15) who completed three measurement sessions using the same protocol but without noise exposure between session one and two50. This reference CI provides an empirical benchmark for expected measurement variability in the absence of auditory change. Combining the bootstrapped-based individual CIs with this test–retest reference framework allows for a rigorous evaluation of whether observed amplitude shifts exceed typical measurement variability. However, no participant exhibited post-exposure ABR wave I amplitude changes beyond these bounds. The apparent variability across participants primarily reflects the wide individual CIs, indicating substantial within-subject variability, rather than poor test–retest reliability.

Figure 7E and F present individual changes in EFR magnitude at 4 kHz and 6 kHz, respectively. Because both the individual variability and test–retest reliability of EFRs are better than ABR wave I amplitudes, consistent with previous findings50, the significance of EFR changes post-exposure becomes more relevant. On day 1 post-exposure, five participants exhibited significant reductions in 4 kHz EFR magnitude, two of them also showing significant reductions at 6 kHz. Importantly, these changes were not confined to participants with the highest exposures or those who did not use HPDs. The reduction in 4 kHz EFR magnitude persisted for three individuals on day 3 post-exposure, and two participants continued to show significant reductions at day 14. Similarly, the 6 kHz EFR response showed sustained reductions for two individuals at both follow-up time points. This persistent reduction suggests that EFR measures of synaptic damage may reflect long-lasting, or potentially irreversible, auditory damage.

Determinants of individual hearing health reductions following noise exposure

To further characterize factors underlying individual variability in early and clinical markers of hearing damage following noise exposure, we evaluated a broader set of exposure metrics beyond the compensated LAeq values. While LAeq was retained to maintain comparability with WHO exposure guidelines, we additionally report unweighted LZeq values and peak SPL levels to provide a more comprehensive representation of the actual sound energy experienced by participants. Unlike LAeq, which is A-weighted to approximate human auditory sensitivity, LZeq and peak measurements capture the full frequency spectrum and short-duration impulse peaks, emphasizing that A-weighted values alone may underestimate true exposure—particularly at low frequencies or during high-intensity events. Figure 8A plots individual 95% CIs of EFR magnitudes against uncompensated LAeq levels, acknowledging the limitations in estimating HPD attenuation due to reliance on manufacturer-reported values and uncertainty in individual usage. Notably, all participants with significant EFR reductions were exposed to levels near to or above 100 dBA, as recorded by the personal dosimeters. A similar trend is visible in Fig. 8B, which examines LZeq at 63 Hz, reaffirming the association between high exposure and EFR decline. Additional analysis of low-frequency energy, including LZ levels at 31 Hz and 125 Hz obtained by summing across frequency bands, showed patterns consistent with those in Fig. 7B. Figure 8C presents LC-peak levels across participants, demonstrating that all participants experienced extremely high impulse noise peaks, though interpretation is constrained by dosimeter saturation at 144 dBC.

Individual changes in 4-kHz EFR strength on day 1 post-exposure, presented as a function of total exposure level: non-HPD-compenstated LAeq (A), LZeq,63 Hz (B), and LCpeak (C). Gray and white symbols denote non-protected and protected festival attendees, respectively. The shaded area represents the 95% confidence intervals (CIs) from a test–retest study50, while dashed lines delineate the overall CI, capturing the average range alongside the 95% CI at each individual data point, derived from individual standard deviations obtained through a resampling bootstrapping method49.

These findings indicate that noise exposure levels were extremely high, representing a potential risk for all participants. Despite broadly similar exposure levels, substantial inter-individual variability in hearing outcomes was observed: while some participants exhibited clear auditory deterioration, others remained relatively unaffected, suggesting that additional factors modulate susceptibility to noise-induced changes.

Discussion

To investigate potential causal links between acute recreational noise exposure and sensorineural hearing damage, we conducted a targeted assessment of SNHL indicators, including measures of both hearing sensitivity (OHC-loss) and synaptic integrity. The relationship of these metrics to individual noise exposure data collected via real-time dosimetry at large-scale music events was assessed. Although CS has been well established in animal models as an early, often hidden marker of noise-induced damage30, human evidence, particularly under real-world recreational conditions, remains limited. By combining objective auditory measures with real-world acoustic exposure data, this study aimed to bridge the current knowledge gap and advance understanding of the early effects of high-intensity recreational sound exposure on the human auditory system.

First, our baseline analyses showed that consistent use of hearing protection is associated with better baseline hearing, as reflected in both behavioral and physiological indicators of hearing integrity. These findings are consistent with previous studies showing that young adults with unfavorable attitudes toward noise, hearing loss, and hearing protection tend to have poorer hearing outcomes51. Moreover, we found that individuals who consistently used ear protection scored significantly better on both the YANS and BAHPHL scales, underscoring the crucial role of attitudes and beliefs toward noise in determining hearing health. These outcomes highlight the importance of proactive preventive efforts among young people. Given the well-documented lack of awareness and persistent misconceptions among adolescents regarding the risks of noise exposure14,15,52, these findings reinforce the importance of targeted education on recreational noise risks to encourage safer listening habits53. In addition, self-reported symptoms such as tinnitus can serve as powerful personal motivators, prompting more consistent use of hearing protection54,55. Incorporating firsthand accounts from individuals affected by hearing-related symptoms into preventive campaigns may enhance their relevance and effectiveness, ultimately fostering more widespread adoption of protective behaviors among young people.

The average equivalent continuous sound level (LAeq) recorded across all participants at the music events was 100 ± 4 dBA, with individual exposures ranging from 85 to 105 dBA. These values are both higher and more variable than those reported for music festivals in Norway2, where LAeq values were 93 ± 1 dBA, assessed using dosimeters, for two events. However, the Norwegian data were based on a notably smaller sample size, comprising only eight participants across two music events. The exclusion of Festival 3 (F3) from the noise exposure analysis, due to significant rainfall and limited sound exposure, reduced the overall standard deviation to 2 dBA, and the mean exposure for the remainder was 101 dBA (range 96–105 dBA). Comparable findings were reported in Switzerland19, where individual exposures ranged from 87 to 104 dBA, with an average exposure of 95 ± 3 dBA. Other investigations of rock concerts and similar events have consistently documented mean levels near 100 dBA3,56. In this study, participants were exposed to sound levels above 94 dBA for 90% of the event duration, above 100 dBA for 50% of the time, and above 103 dBA for 10% of the time. These values have a similar pattern but are higher than those reported in2, where L90, L50, and L10 values of 88 dBA, 97 dBA, and 104 dBA were observed. Given that dosimeters recorded the entire duration of each event, including periods of relative quiet and rest, the data provide compelling evidence that attendees at large-scale music events consistently expose themselves to excessive sound levels. As detailed in Table 1, participants spent approximately 40% of their time exposed to sound levels exceeding the WHO’s recommended maximum of 100 dBA, representing a substantial risk to auditory health. Consistent with this, 25 out of 41 participants (61%) reported hearing-related symptoms on day one post exposure, a higher incidence than previously reported by57 (42%) and19 (36%). Notably, the majority of symptomatic participants either did not use HPD (16 of 25) or used it inconsistently (9 of 25). Only three individuals who reported symptoms had worn HPDs for more than 60% of the event duration, supporting earlier findings that consistent HPD use mitigates such symptoms58.

Despite the high sound levels recorded, no group-level changes were observed in pure-tone thresholds or DPOAE amplitudes, both of which serve as indicators of OHC integrity. This appears to be inconsistent with studies that reported TTS following music events3,56,59,60. However, most of those studies did not include participants who used hearing protection, or found TTS predominantly for unprotected participants. Also, the assessments were typically conducted immediately after exposure, whereas our follow-up measurements occurred no earlier than the following morning1. Since most recovery from TTS occurs within 2–5 h post-exposure26,58,59,61, our study likely captured largely recovered auditory thresholds. This aligns with previous findings57,61, which reported no significant correlation between self-reported noise exposure and changes in audiometric threshold one day after music events of a similar nature than ours. Our findings on DPOAE amplitudes are also consistent with prior studies34,61 which found no significant change one day post-exposure.

A key innovation of this study was the inclusion of electrophysiological markers of synaptic damage, a form of hearing damage that most likely precedes measurable OHC loss. While animal research has shown high sensitivity of AEPs to CS30, applying these markers in humans presents challenges due to high inter-individual variability and potential confounds, such as OHC dysfunction47,62,63. In spite of these challenges, researchers have persisted in studying the relationship between noise exposure history and AEP markers of CS. Investigations involving normal-hearing young veterans46, and college music students64, suggest that individuals with high reported noise exposure and acute recreational noise exposure34 may show a reduction in ABR wave I amplitude. However, other investigations, including the present study, did not observe significant reductions in wave I amplitude following recreational noise exposure41,42,61. These discrepancies may stem from differences in exposure duration. For example, studies such as46 and65 divided participants into low-risk and high-risk groups based on their self-reported noise exposure history, capturing the impact of chronic noise exposure rather than acute noise exposure. Additionally, the inherent variability in ABR amplitudes may limit the reliability of this measure. Factors such as head size, biological sex, high-frequency OHC status, electrode placement, and ambient electrical noise are known contributors to this variability62,66,67. As a result, ABR may lack the sensitivity needed to detect subtle synaptic damage in human populations50. This limitation is reflected in our data, which show considerable inter-individual variation and wide CIs. Additionally, at baseline, we found no significant relationship between ABR measures and participants’ noise exposure histories.

The grey-shaded areas in the individual data plots, representing the test–retest variability among non-noise exposed young individuals, appear rather small compared to the variability observed in the current study. This can be attributed to several factors, including the larger sample size (42 participants vs. 15 in the test–retest study), the context of a music festival visit, which may have led to increased fatigue and restlessness among participants on the first day post-exposure, and the absence of COVID-19 restrictions for the present study. The test–retest data were collected during the COVID-19 pandemic, when environmental and social exposure was more controlled. All of these factors might have led to greater variability between measurement sessions in our study. These findings underscore that test–retest variability should always be interpreted with caution in studies investigating potential effects over time, as additional uncontrolled variables may influence the outcomes.

Since noise-induced CS is believed to preferentially affect low-SR ANFs68, at least in some species, and phase locking to temporal envelopes is particularly strong in these fibers, EFRs have emerged as a potentially more robust marker of CS69,70. Relative to ABR amplitude measures, phase information extracted from EFRs is probably less influenced by individual anatomical differences71, leading to higher test–retest reliability. This hypothesis is supported by findings from previous studies50,72, which show superior test–retest reliability of frequency following responses and EFRs than their ABR counterparts. Moreover, recent work has optimized EFR stimulus design to improve its sensitivity in detecting individual CS differences through a combination of computational and experimental methods70,73. Using this optimized RAM-EFR stimulus, we observed significant amplitude reductions in five participants following noise exposure, providing evidence of a causal link between acute recreational noise exposure and a subclinical human AEP-marker. These results support the idea that synaptic damage precedes outer hair cell loss and often remains undetected by conventional audiometry34,74,75. In two participants, the reduction persisted through day 14 post-exposure, suggesting potentially irreversible cochlear synaptopathy. In the remaining participants, the transient reductions may reflect temporary excitotoxicity or synaptic swelling, reversible phenomena documented in animal studies in which noise exposure temporarily reduces auditory nerve output without causing permanent synapse loss76,77.

Although we found significant reductions in EFR amplitudes, no consistent association was established between these changes and the accumulated LAeq-compensated levels recorded at the events. To account for possible inaccuracies in the calculated LAeq, comp values and self-reported HPD usage, we also examined uncompensated exposure levels. Notably, all individuals who exhibited pronounced EFR reductions, including the two participants whose compensated values suggested markedly lower exposure, had average uncompensated exposure levels at or above approximately 100 dBA. This pattern suggests that participants with lower compensated exposures may have either failed to use HPDs consistently or worn them improperly, thereby undermining their efficacy. Importantly, not all individuals exposed to similarly high sound levels exhibited significant EFR changes, highlighting the limitation of relying solely on exposure level to predict auditory outcomes. This variability reflects substantial inter-individual differences in vulnerability to NIHL78. Factors previously associated with increased vulnerability include age, pre-existing sensorineural hearing loss, smoking, use of ototoxic medications, type 2 diabetes, and hypertension. However, the mechanisms underlying variability in susceptibility remain poorly understood, and existing research has produced inconsistent findings. This highlights the need for further studies investigating the influence of underlying ear and hearing conditions (e.g., chronic otitis media), genetic predispositions, and lifestyle-related comorbidities. Elucidating these factors is essential for identifying at-risk subgroups and developing targeted interventions to mitigate NIHL. A comprehensive, holistic approach that considers an individual’s cumulative noise exposure, genetics, and pathology could substantially advance our understanding of the multifactorial nature of NIHL and inform prevention strategies. Beyond individual susceptibility, cumulative noise exposure itself appears to play a critical role. Our baseline data show that participants who used HPDs consistently over the years maintained significantly better hearing than those without protection. These results underscore that repeated or sequential noise exposures, rather than isolated events, are likely the primary drivers of auditory damage, as observed in rodents36, emphasizing that consistent and long-term use of hearing protection is essential to preserve hearing health.

Conclusions

Prior research on NIHL has often been hampered by retrospective designs and a lack of individualized noise exposure data, leading to inconclusive and conflicting outcomes. This study addressed these limitations through a longitudinal study design using personal dosimetry, enabling accurate, real-time monitoring of individual noise exposure during recreational music events. There are four key implications of the findings: First, baseline assessments revealed that young individuals who fail to use hearing protection consistently show early signs of auditory dysfunction, both behaviorally and physiologically. This underscores the urgency of promoting protective listening behaviors in high-noise recreational settings. Second, the study highlights a critical limitation in current monitoring practices. While public address (PA) system levels are often used as proxies for regulatory compliance, they fail to reflect the highly variable, individualized noise exposure experienced by attendees, determined by factors such as proximity to loudspeakers, crowd behavior, and movement within the venue. In our data, the exposure of 56% of participants exceeded the WHO’s recommended LAeq of 100 dBA, with 40% of event time spent above safe limits, figures that would likely go undetected if relying solely on centralized PA measurements. Third, while only one participant showed an OSHA-defined clinically significant shift in hearing sensitivity, five participants exhibited reductions in AEP markers of CS within 24 h post-exposure. Additional temporary threshold shifts were observed at individual frequencies; however, despite the full recovery of these frequency-specific TTSs, the EFRs remained significantly reduced, with two individuals showing persistent reductions up to 14 days post-exposure. These subtle yet persistent changes, undetected by conventional audiometry, underscore the hidden nature of early auditory damage and the limitations of current clinical diagnostic methods. Fourth, the lack of a direct correlation between exposure level and degree of damage confirms the importance of individual susceptibility, shaped by genetic predisposition, prior noise exposure, and potentially other unknown variables. This finding reinforces the need for personalized hearing health strategies. Looking towards the future of NIHL monitoring, the use of non-invasive early biomarkers for OHC and synaptic damage presents both promise and challenges. A key area for development lies in optimizing auditory evoked potential (AEP) measurements, specifically through detailed examination of the effects of stimulus parameters and presentation rates, to enhance sensitivity and reliability. More diverse cohorts are needed to characterize individual differences in vulnerability to noise-induced injury. Evaluating noise exposure history adds another layer of complexity, but also offers the opportunity to identify correlations between AEP markers and the cumulative effects of repeated or prolonged exposure. In specific settings, such as music festivals, multiple variables must be considered, including recent exposure dose, hearing protection use, spectral and temporal noise characteristics, and the presence of hearing related symptoms. These factors interact in nuanced ways to influence auditory processing and AEP outcomes. Studying them within well-characterized, heterogeneous populations is essential for disentangling their respective contributions. Additionally, immediate post-event evaluations can provide valuable insight into the short-term dynamics of auditory recovery or damage, while future investigations into genetic predisposition may reveal why some individuals are more susceptible to noise than others. Together, these avenues represent critical steps toward a more precise, personalized, and comprehensive understanding of how recreational noise exposure affects human hearing health.

Methods

Forty-two normal-hearing young adults underwent evaluations 1–3 days prior to the music event and on days 1 and 3 following the event, with an additional assessment on day 14 for cases of persistent hearing damage. Ethical approval was obtained from the local ethical committee (BC-05214) and the study adhered to the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Participants provided informed consent after receiving a detailed briefing on study procedures. Hearing status was assessed using standard and extended-high-frequency audiometry, distortion-product otoacoustic emissions (DPOAEs), and AEPs, including Auditory Brainstem Responses (ABRs) and Envelope Following Responses (EFRs). ABRs, evoked by auditory click trains, reflect synchronized firing of ANFs and brainstem neurons79, while EFRs, elicited by amplitude-modulated pure tones, assess the temporal coding accuracy of subcortical neurons69,80. In rodent models, reductions in ABR wave I amplitude and EFR strength have been consistently associated with age-related81,82 and noise-induced hearing loss83, confirmed through histological evidence of synaptic damage.

Additionally, attendees completed questionnaires on their noise exposure history, attitudes towards noise and hearing protection, and perceived hearing difficulties after the event.

Music event selection

We conducted measurements at six large-scale music festivals across Europe, each located within approximately 150 km of the university hospital and lasting a minimum of eight hours. Approval was obtained from the security personnel of the respective organizations to conduct on-site sound level measurements. The number of participants attending each of these events, denoted as F1 to F6, was as follows: seven at F1, with four attending the festival for two subsequent days, seven at F2, six at F3, seven at F4, seven at F5, and eight at F6. These music festivals, with attendance ranging from 4000 to 60,000 people, took place in tented or open-air venues.

Participants and study design

Forty-two young adults (19 women and 23 men) aged between 18 and 25 years (mean age 23.1 years ± 1.2 standard deviation; SD), were recruited. At the beginning of each festival, Casella dBadge2 dosimeters were secured to the participants’ clothing using clips. These dosimeters were positioned at shoulder height as close to the ear as possible to accurately measure ear exposure. Regular checks were conducted throughout each music event to ensure that the dosimeters were recording properly and mounted correctly. Half of the participants chose to wear HPDs during some portion of the exposure, while the others did not use any HPD. Participants were instructed to log the start and end times of their HPD-usage on their mobile phone, as this information was essential for adjusting individual exposure doses captured by the dosimeters, taking into account the factory specifications of the respective HPDs.

A screening questionnaire was administered, followed by pure tone audiometry and tympanometry during the pre-measurement. Individuals with documented hearing disorders, a history of ear surgery, or tinnitus were excluded from participation. To assess participants’ hearing before and after the festival, there were three measurement sessions: Pre, post 1, and post 2. These sessions took place 1–2 days before the music event, and on day 1 and day 3 after the event. If participants showed indications of persistent hearing damage, an additional session was conducted 14 days after the event (post 3). One participant did not undergo post-exposure measurements, and seven underwent an additional measurement at day 14. Participants were instructed to avoid exposure to loud activities before and after the music event, to minimize potential confounding factors. During the pre-measurement, the ear with better hearing sensitivity at conventional audiogram frequencies (0.25 to 8 kHz) was selected as the test ear for the subsequent hearing tests. Half of the 42 participants were tested using the right ear, and the other half using their left ear. Each session included a comprehensive test battery of hearing assessments presented in a fixed sequence, with a total maximum duration of one hour and forty-five minutes. These assessments included tympanometry, audiometry (including extended high frequencies, EHF), DPOAEs and AEP measurements.

Assessment of middle ear function

Otoscopy and tympanometry

The ear canal and tympanic membrane were examined using a BETA 200 LED otoscope. Normal otoscopic findings were observed for both ears of all participants. Middle-ear admittance was measured using a GSI TympStar (Grason-Stadler) tympanometer with a 226 Hz, 85 dB SPL probe tone. Bilateral measurements were conducted. According to the Liden-Jerger classification84,85, all tympanograms were classified as type-A.

Assessment of hearing sensitivity

Pure tone audiometry

Audiometric thresholds were measured for both ears. The conventional frequencies tested were 0.125, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, and 8 kHz. The EHFs tested were 10, 12.5, 14, 16, and 20 kHz. Thresholds were determined using an Equinox Interacoustics audiometer inside a sound-attenuating booth. TDH-39 headphones were used for conventional frequencies, while Sennheiser HDA-200 headphones were used for EHF testing. Air-conduction thresholds were measured following the modified Hughson-Westlake technique. All participants were classified as having normal hearing according to the WHO guidelines, which define normal hearing as a better-ear audiometric threshold averaged over 0.5, 1, 2, and 4 kHz equal or below 20 dB HL86.

Distortion product otoacoustic emissions

DPOAEs provide a valuable tool for early and objective assessments of OHC integrity. They reflect responses with frequency 2f1-f2 generated by the cochlea in response to two simultaneous tones with frequencies f1 and f2.

DPOAEs were recorded from the test ear using a Universal Smart Box (Intelligent Hearing Systems) in a sound-attenuating booth. 10D OAE-probes were inserted into the ear canal, and ear calibration with level adjustment was performed using the Smart DPOAE software. DPOAE responses and noise amplitudes were measured by simultaneously presenting two primary tones with a frequency ratio of f2/f1 = 1.22. The noise artifact rejection was set at 10 dB SPL, and 32 sweeps were obtained for each frequency. DP-grams were generated using primary tone levels L1/L2 = 65/55 dB SPL, with f2 frequencies ranging from 553 to 8837 Hz at two points per octave and from 8837 to 11,459 Hz at eight points per octave. This resulted in twelve frequency bands with center frequencies of 0.5, 0.7, 1.0, 1.4, 2.0, 2.8, 4.0, 5.7, 8.0, 8.7, 9.5, and 10.3 kHz.

A signal-to-noise (SNR) criterion of SNR > 0 was used to assess the quality of individual DPOAE measurements. If the response amplitude was found to be smaller than the noise amplitude, the response amplitude was adjusted to match the noise amplitude50. In some instances, DPOAEs were present during pre-exposure measurements but fell below the noise floor after exposure. To maximize data retention, when this occurred we substituted post-exposure emission amplitudes with corresponding post-exposure noise floor amplitudes when they were smaller than the pre-exposure response amplitudes87,88. Conversely, if the post-exposure noise floor exceeded the pre-exposure emission amplitude, the noise amplitude was treated as missing data.

Measures of CS using suprathreshold AEPS

Auditory evoked potentials

EFR strengths and ABR wave-I amplitudes in response to suprathreshold stimulation serve as physiological markers of CS. The EFR reflects the phase-locking activity of auditory neurons to the envelope of sound stimuli, offering insights into the integrity of cochlear synapses and neural encoding of sound, while ABR wave-I reflects the synchronized firing of auditory nerve and brainstem fibers in response to sound stimuli.

EFRs and ABRs were measured for the test ear using the IHS Universal Smart Box and SEPCAM software. Recordings took place in a sound-attenuating booth, with participants seated comfortably and their heads supported by a soft pillow. Participants watched a muted video and were instructed to remain still during the recordings and avoid falling asleep. Prior to electrode placement, the skin was prepared with NuPrep gel, and disposable Ambu Neuroline electrodes were positioned on the vertex (inverting electrode), the nasal flank of the non-test ear (ground electrode), and bilateral mastoids (non-inverting electrodes) (Fig. 1). The impedance of the electrodes never exceeded 3 kΩ. Shielded Etymotic ER-2 ear-probes were used to deliver all stimuli.

To evoke EFRs, two Rectangularly Amplitude-Modulated (RAM)-stimuli were used, based on recent findings suggesting that stimuli with rectangular envelopes and deep modulation depths are more sensitive to individual EFR differences compared to conventional sinusoidally amplitude-modulated (SAM) stimuli. RAM stimuli are believed to enhance the EFR’s specificity to CS by minimizing the relative impact of OHC damage, owing to their sharply rising envelope70.

The RAM stimuli, with carrier frequencies of 4 and 6 kHz and a duty cycle of 25%, were presented with alternating polarity for 1000 trials. The stimuli had a modulation frequency of 110 Hz, a modulation depth of 100%, and a stimulus onset asynchrony (SOA) of 500 ms, and were presented at a rate of 2 Hz. Calibrated RAM stimuli were presented at 68.2 dB SPL to give the same peak-to-peak amplitude as a 70 dB SPL SAM tone.

Matlab R2018b was used for EFR processing. Initially, the raw recordings were filtered using an 800th-order finite-impulse-response bandpass filter with cutoff frequencies of 30 Hz and 1500 Hz. Following this, epoching, baseline correction, and a bootstrapping method were employed to estimate the EFR signal, variability, and noise-floor in the frequency domain89. The EFR strength was quantified as the sum of the signal-to-noise spectral magnitude at the frequencies of the first four harmonics (110, 220, 330, and 440 Hz)70.

ABRs were evoked using 4000 alternating-polarity sweeps comprising four stimulus types: two broadband clicks and two narrowband tone burst (TB) stimuli. The clicks had durations of 80 µs and were presented at levels of 70 and 80 dBpeSPL. The TB stimuli, with frequencies of 0.5 kHz and 4 kHz and durations of 5 ms and 2 ms, respectively, were presented at a level of 70 dBpeSPL. Click stimuli were presented at a rate of 11 Hz, while the TB stimuli were presented at a rate of 20 Hz. Matlab R2020b was used for ABR data processing. ABR recordings were bandpass filtered offline between 100 and 1500 Hz using a zero-phase filter. Subsequently, epoching, baseline correction, and averaging of the epochs were performed to derive the mean ABR waveform. Audiologists manually peak picked ABR waves I, III, and V to estimate their amplitudes and latencies. ABR amplitudes were determined as peak-to-baseline values.

EFR and ABR measures were omitted for one participant in post 1 and another participant in post 3 due to the presence of a post-auricular muscle artifact in the ABR response. Such artifacts are particularly common for tense participants, and manifest as a sharp spike in the range 13 to 15 ms90, along with a peak with a higher amplitude than that of wave V, making EEG responses unreliable91.

Questionnaires

The initial questionnaire, conducted at baseline, began with inquiries regarding noise exposure history, hearing related symptoms, general use of hearing protection, and recent noise exposure. Additionally, two scales were included: the Youth Attitude to Noise Scale (YANS) (Widen et al.54) and Beliefs about Hearing Protection and Hearing Loss (BAHPHL)92, as modified by Keppler et al.93. Both scales employ a five-point Likert scale, ranging from ‘totally agree’ to ‘totally disagree’, to evaluate attitudes and beliefs regarding noise, hearing protection, and hearing loss. A higher score indicates more positive attitudes and beliefs towards noise, suggesting reduced concerns about hearing damage and less confidence in the efficacy of hearing protections devices. Subsequent sessions delved more deeply into the experience of hearing related symptoms by administering structured questionnaires.

Sound level measurements during the events

The Casella dBadge2 dosimeters have a 1/2" diameter microphone covered by a foam windscreen. To shield against heavy rainfall during F3, thin plastic bags were employed to protect the dosimeters. The recording device provided global exposure markers (LAeq, LCeq) according to ISO 9612 for the entire exposure duration, as well as at 1-s and 1-min intervals. Additionally, A-weighted sound levels measured with Fast Time Weighting (LAFmax) and peak C-weighted sound levels (LCpeak) were recorded to capture peak exposures. The recordings encompassed the entire event duration from participants’ arrival until departure. On average, the exposure duration was 10.3 h (SD: 4.8), with recordings spanning two days for four participants. Values from the two-day recordings were recalculated to represent single-day exposures for each event. The time-averaged values from the two days were combined using time-weighted energy-based averages. Maximum peak exposure values from both days were considered, and the counts of regulation exceedances were summed for the two days (Table 1). Ear protection was factored in by calculating compensated sound pressure levels. The compensation used one of four levels of reduction (0 dB, 19 dB, 22 dB, 28 dB), depending on the ear protection brand and type. For unknown foam earplugs, a 28 dB reduction was assumed. Compensated 1-s sound pressure levels (A and C-weighted) were calculated based on the reductions and wear time. Equivalent sound pressure levels for longer time windows, such as 15-min, were derived from the compensated 1-s intervals.

Statisical analyses

All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS (IBM) version 29.0. Initially, the results from the pre measurement were assessed to examine differences in hearing status and YANS- and BAHPHL-scores between participants who used ear protection and those who did not. Independent sample t-tests were used for this comparison, preceded by a comprehensive examination of descriptive parameters and tests of normality (Shapiro–wilk, QQ-plots, and homogeneity of variances, Levene’s test) to check that the assumptions for subsequent t-test analysis were met. Subsequently, noise exposure characteristics were explored, and exposure levels were compared between men and women using independent sample t-tests. Thirdly, group level analyses were carried out using one-way repeated measures ANOVA, with verification of the assumptions for these analyses. Post hoc tests with Bonferroni correction were applied to identify inter-session differences in hearing-health parameters. To further assess individual variability and potential post-exposure changes, we performed additional analyses of inter-session data for each subject. Descriptive charts were generated for hearing health parameters, with upper and lower bounds representing global 95% confidence intervals (CIs) based on a test–retest study conducted within our research group, which included three repeated measurements across 15 subjects using the same protocol but without the noise exposure between session one and session two50. These visualizations provided reference for normal test–retest variability and facilitated contextualized observed changes in relation to exposure levels. For auditory evoked potential (AEP) data, pointwise CIs were calculated for each datapoint using a resampling bootstrap method, as shown in Fig. 9A and B49. Individual changes were considered statistically significant if the bootstrap CI did not overlap with the zero line, providing a rigorous basis for identifying subject-specific deviations from baseline and potential trends in response to noise exposure. Together, these analyses integrate cohort-level test–retest variability (global CIs) and intra-individual variability (bootstrap CIs for AEPs), enabling a comprehensive assessment of hearing health changes attributable to the music event.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Elmazoska, I., Mäki-Torkko, E., Granberg, S. & Widén, S. Associations between recreational noise exposure and hearing function in adolescents and young adults: A systematic review. J. Speech. Lang. Hear. Res. 67(2), 688–710 (2024).

Tronstad, T. V. & Gelderblom, F. B. Sound exposure during outdoor music festivals. Noise Health 18(83), 220–228. https://doi.org/10.4103/1463-1741.189245 (2016) (in English).

Ramakers, G. G., Kraaijenga, V. J., Cattani, G., van Zanten, G. A. & Grolman, W. Effectiveness of earplugs in preventing recreational noise-induced hearing loss: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 142(6), 551–558. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoto.2016.0225 (2016).

Van Ransbeeck, W., De Poortere, N., Kok, M. & Verhulst, S. Characteristics of personal sound and noise exposure at large-scale music events. J. Audio Eng. Soc. 72(12), 901–912 (2024).

Clark, W. W. Recent studies of temporary threshold shift (TTS) and permanent threshold shift (PTS) in animals. J. Acoust. Soci. Am. 90(1), 155–163. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.401309 (1991).

Jokitulppo, J. S., Björki, E. A. & Akaan-Penttiä, E. Estimated leisure noise exposure and hearing symptoms in Finnish teenagers. Scand. Audiol. 26(4), 257–262 (1997).

Meyer-Bisch, C. Epidemiological evaluation of hearing damage related to strongly amplified music (personal cassette players, discotheques, rock concerts)-high-definition audiometric survey on 1364 subjects. Audiology 35(3), 121–142 (1996).

Tin, L. L. & Lim, O. P. A study on the effects of discotheque noise on the hearing of young patrons. Asia Pacific J. Public Health 12(1), 37–40 (2000).

Dalton, D. S. et al. Association of leisure-time noise exposure and hearing loss: Asociación entre exposición a ruido durante el tiempo libre e hipoacusia. Audiology 40(1), 1–9 (2001).

Zhao, F., Manchaiah, V. K., French, D. & Price, S. M. Music exposure and hearing disorders: An overview. Int. J. Audiol. 49(1), 54–64. https://doi.org/10.3109/14992020903202520 (2010).

Carter, L., Williams, W., Black, D. & Bundy, A. The leisure-noise dilemma: hearing loss or hearsay? What does the literature tell us?. Ear Hear. 35(5), 491–505. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.aud.0000451498.92871.20 (2014) (in English).

WHO, Burden of disease from environmental noise: Quantification of healthy life years lost in Europe. World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe, 2011.

Weichbold, V. & Zorowka, P. Can a hearing education campaign for adolescents change their music listening behavior? ¿ Puede una campaña de educación auditiva para adolescentes cambiar sus conductas para escuchar música?. Int. J. Audiol. 46(3), 128–133 (2007).

Rawool, V. W. & Colligon-Wayne, L. A. Auditory lifestyles and beliefs related to hearing loss among college students in the USA. Noise Health 10(38), 1 (2008).

Shah, S., Gopal, B., Reis, J. & Novak, M. Hear today, gone tomorrow: An assessment of portable entertainment player use and hearing acuity in a community sample. J. Am. Board Family Med. 22(1), 17–23 (2009).

Vogel, I., Brug, J., Hosli, E. J., Van Der Ploeg, C. P. & Raat, H. MP3 players and hearing loss: Adolescents’ perceptions of loud music and hearing conservation. J. Pediatr. 152(3), 400-404.e1 (2008).

Degeest, S., Keppler, H., Corthals, P. & Clays, E. Epidemiology and risk factors for tinnitus after leisure noise exposure in Flemish young adults. Int. J. Audiol. 56(2), 121–129. https://doi.org/10.1080/14992027.2016.1236416 (2017).

Keppler, H., Ingeborg, D., Sofie, D. & Bart, V. The effects of a hearing education program on recreational noise exposure, attitudes and beliefs toward noise, hearing loss, and hearing protector devices in young adults. Noise Health 17(78), 253 (2015).

V. Mercier, D. Luy, and B. W. Hohmann, The sound exposure of the audience at a music festival, (in eng), Noise & health, vol. 5, no. 19, pp. 51–8, Apr-Jun 2003. [Online]. Available: http://www.noiseandhealth.org/article.asp?issn=1463-1741;year=2003;volume=5;issue=19;spage=51;epage=58;aulast=Mercier.

Smith, P. A., Davis, A., Ferguson, M. & Lutman, M. E. The prevalence and type of social noise exposure in young adults in England. Noise Health 2(6), 41–56 (2000) (in English).

Pienkowski, M. Loud music and leisure noise is a common cause of chronic hearing loss, tinnitus and hyperacusis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18(8), 4236 (2021).

Wang, Y., Hirose, K. & Liberman, M. C. Dynamics of noise-induced cellular injury and repair in the mouse cochlea. J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 3, 248–268 (2002).

Yamane, H. et al. Appearance of free radicals in the guinea pig inner ear after noise-induced acoustic trauma. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 252, 504–508 (1995).

N. Hakuba, K. Koga, K. Gyo, S. I. Usami, and K. Tanaka, Exacerbation of noise-induced hearing loss in mice lacking the glutamate transporter GLAST, J. Neurosci.: The Off. J. Soci. Neurosci., vol. 20, no. 23, pp. 8750–3, Dec 1 2000. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11102482.

Puel, J. L., Ruel, J., Gervais d’Aldin, C. & Pujol, R. Excitotoxicity and repair of cochlear synapses after noise-trauma induced hearing loss. NeuroReport 9(9), 2109–2014. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001756-199806220-00037 (1998).

Le Prell, C. G. et al. Digital music exposure reliably induces temporary threshold shift in normal-hearing human subjects. Ear Hear. 33(6), e44–e58. https://doi.org/10.1097/AUD.0b013e31825f9d89 (2012) (in English).

Ryan, A. F., Kujawa, S. G., Hammill, T., Le Prell, C. & Kil, J. temporary and permanent noise-induced threshold shifts: A review of basic and clinical observations. Otol. Neurotol.: Off. Publ. Am. Otol. Soci., Am. Neurotol. Soci. Eur. Acad. Otol. Neurotol. 37(8), 12715. https://doi.org/10.1097/mao.0000000000001071 (2016) (in English).

Trzaskowski, B., Jędrzejczak, W. W., Piłka, E., Cieślicka, M. & Skarżyński, H. Otoacoustic emissions before and after listening to music on a personal player. Med. Sci. Monitor: Int. Med. J. Exp. Clin. Res. 20, 1426–1431. https://doi.org/10.12659/MSM.890747 (2014) (in English).

Diuba, A. et al. Phenotypic changes of auditory nerve fibers after excitotoxicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 122(14), e2412332122 (2025).

Kujawa, S. G. & Librman, M. C. Adding insult to injury: Cochlear nerve degeneration after temporary noise-induced hearing loss. J. Neurosci.: Off. J. Soci. Neurosci. 29(45), 14077–14085. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2845-09.2009 (2009).

Sergeyenko, Y., Lall, K., Liberman, M. C. & Kujawa, S. G. Age-related cochlear synaptopathy: An early-onset contributor to auditory functional decline. J. Neurosci. 33(34), 13686–13694. https://doi.org/10.1523/jneurosci.1783-13.2013 (2013) (in English).

Furman, A. C., Kujawa, S. G. & Liberman, M. C. Noise-induced cochlear neuropathy is selective for fibers with low spontaneous rates. J. Neurophysiol. 110(3), 577–586 (2013).

Lobarinas, E., Salvi, R. & Ding, D. Insensitivity of the audiogram to carboplatin induced inner hair cell loss in chinchillas. Hear. Res. 302, 113–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heares.2013.03.012 (2013).

Wang, Q. et al. Acute recreational noise-induced cochlear synaptic dysfunction in humans with normal hearing: A prospective cohort study. Front. Neurosci. 15, 659011 (2021).

Schaette, R. & McAlpine, D. Tinnitus with a normal audiogram: physiological evidence for hidden hearing loss and computational model. J. Neurosci.: Off. J.. Soci. Neurosci. 31(38), 13452–13457. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2156-11.2011 (2011).

Fernandez, K. A., Jeffers, P. W., Lall, K., Liberman, M. C. & Kujawa, S. G. Aging after noise exposure: acceleration of cochlear synaptopathy in “recovered” ears. J. Neurosci.: Off. J. Soci. Neurosci. 35(19), 7509–7520. https://doi.org/10.1523/jneurosci.5138-14.2015 (2015) (in English).

Wu, P.-Z., O’Malley, J. T., de Gruttola, V. & Liberman, M. C. Primary neural degeneration in noise-exposed human cochleas: Correlations with outer hair cell loss and word-discrimination scores. J. Neurosci. 41(20), 4439–4447 (2021).

Bramhall, N. F. Use of the auditory brainstem response for assessment of cochlear synaptopathy in humans. J. Acoust. Soci. Am. 150(6), 4440–4451 (2021).

Bharadwaj, H. M. et al. Non-invasive assays of cochlear synaptopathy–candidates and considerations. Neuroscience 407, 53–66 (2019).

Fulbright, A. N. C., Le Prell, C. G., Griffiths, S. K. & Lobarinas, E. Effects of recreational noise on threshold and suprathreshold measures of auditory function. Semin. Hear. 38(4), 298–318. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0037-1606325 (2017).

Guest, H., Munro, K. J., Prendergast, G., Millman, R. E. & Plack, C. J. "Impaired speech perception in noise with a normal audiogram: No evidence for cochlear synaptopathy and no relation to lifetime noise exposure. Hear. Res. 364, 142–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heares.2018.03.008 (2018) (in English).

Prendergast, G. et al. Effects of noise exposure on young adults with normal audiograms I: Electrophysiology. Hear. Res. 344, 68–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heares.2016.10.028 (2017) (in English).

Grose, J. H., Buss, E. & Hall, J. W. Loud music exposure and cochlear synaptopathy in young adults: Isolated auditory brainstem response effects but no perceptual consequences. Trends in hearing, Article 21, 2331216517737417. https://doi.org/10.1177/2331216517737417 (2017) (in English).

Paul, B. T., Bruce, I. C. & Roberts, L. E. Evidence that hidden hearing loss underlies amplitude modulation encoding deficits in individuals with and without tinnitus. Hear. Res. 344, 170–182 (2017).

Skoe, E. & Tufts, J. Evidence of noise-induced subclinical hearing loss using auditory brainstem responses and objective measures of noise exposure in humans. Hear Res 361, 80–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heares.2018.01.0053 (2018).

Bramhall, N. F., Konrad-Martin, D., McMillan, G. P. & Griest, S. E. Auditory brainstem response altered in humans with noise exposure despite normal outer hair cell function. Ear Hear 38(1), e1 (2017).

Bharadwaj, D. et al. Non-invasive assays of cochlear synaptopathy – candidates and considerations. Neuroscience https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2019.02.031 (2019).

N. De Poortere, S. Verhulst, S. Degeest, S. Keshishzadeh, I. Dhooge, and H. Keppler, Evaluation of Lifetime Noise Exposure History Reporting, J. Speech. Lang. Hear. Res., pp. 1–23, 2023.

Zhu, L., Bharadwaj, H., Xia, J. & Shinn-Cunningham, B. A comparison of spectral magnitude and phase-locking value analyses of the frequency-following response to complex tones. J. Acoust. Soci. Am. 134(1), 384–395 (2013).

N. De Poortere, S. Keshishzadeh, H. Keppler, I. Dhooge, and S. Verhulst, Intrasubject variability in Potential Early Markers of Sensorineural Hearing Damage, medRxiv, p. 2024.01. 18.24301474, 2024.

Keppler, H., Dhooge, I., Degeest, S. & Vynck, B. The effects of a hearing education program on recreational noise exposure, attitudes and beliefs toward noise, hearing loss, and hearing protector devices in young adults. Noise Health 17(78), 253–262. https://doi.org/10.4103/1463-1741.165028 (2015).

Weichbold, V. & Zorowka, P. Effect of information about hearing damage caused by loud music. For adolescents the music in discoteques is too loud despite loudness limits. HNO 50(6), 560–564 (2002).

Widen, S. E., Holmes, A. E. & Erlandsson, S. I. Reported hearing protection use in young adults from Sweden and the USA: effects of attitude and gender. Int. J. Audiol. 45(5), 273–280. https://doi.org/10.1080/14992020500485676 (2006).

Widen, S. E., Holmes, A., Johnson, T., Bohlin, M. & Erlandsson, S. Hearing, use of hearing protection, and attitudes towards noise among young American adults. Int. J. Audiol. 48(8), 537–545 (2009).

Widén, S. O. & Erlandsson, S. The influence of socio-economic status on adolescent attitude to social noise and hearing protection. Noise Health 7(25), 59–70 (2004).

Opperman, D. A., Reifman, W., Schlauch, R. & Levine, S. Incidence of spontaneous hearing threshold shifts during modern concert performances. Otolaryngol. head Neck Surg. Off. J. Am. Acad. Otolaryngol. Head. Neck Surg. 134(4), 667–673. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.otohns.2005.11.039 (2006) (in English).

Vande Maele, T. V. et al. The variability in potential biomarkers for cochlear synaptopathy after recreational noise exposure. J. Speech. Lang. Hear. Res. 64(12), 4964–4981 (2021).

Kraaijenga, V. J. C., van Munster, J. & van Zanten, G. A. Association of behavior with noise-induced hearing loss among attendees of an outdoor music festival: A secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 144(6), 490–497. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoto.2018.0272 (2018) (in English).

Emmerich, E. et al. Effects of discotheque music on audiometric results and central acoustic evoked neuromagnetic responses. Int. Tinnitus J. 8(1), 13–19 (2002) (in English).

Le Prell, C. G. Effects of noise exposure on auditory brainstem response and speech-in-noise tasks: A review of the literature. Int. J. Audiol. 58(sup1), S3–S32. https://doi.org/10.1080/14992027.2018.1534010 (2019).

Grinn, S. K., Wiseman, K. B., Baker, J. A. & Le Prell, C. G. Hidden hearing loss? No effect of common recreational noise exposure on cochlear nerve response amplitude in humans. Front. Neurosci. 11, 465 (2017).

S. Verhulst, A. Jagadeesh, M. Mauermann, and F. Ernst, Individual Differences in Auditory Brainstem Response Wave Characteristics: Relations to Different Aspects of Peripheral Hearing Loss, Trends in hearing, Article vol. 20, 2016. (in English) http://www.embase.com/search/results?subaction=viewrecord&from=export&id=L621372574.

Bramhall, N. et al. The search for noise-induced cochlear synaptopathy in humans: Mission impossible?. Hear. Res. 377, 88–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heares.2019.02.016 (2019).

Liberman, M. C., Epstein, M. J., Cleveland, S. S., Wang, H. B. & Maison, S. F. Toward a differential diagnosis of hidden hearing loss in humans. PLoS ONE 11(9), e0162726 (2016).

Liberman, M. C., Epstein, M. J., Cleveland, S. S., Wang, H. & Maison, S. F. Toward a differential diagnosis of hidden hearing loss in humans. PLoS ONE https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0162726 (2016) (in English).

Mitchell, C., Phillips, D. S. & Trune, D. R. Variables affecting the auditory brainstem response: Audiogram, age, gender and head size. Hear. Res. 40(1–2), 75–85 (1989).

Plack, C. J. et al. Toward a diagnostic test for hidden hearing loss. Trends Hear 20(9), 2331216516657466. https://doi.org/10.1177/2331216516657466 (2016) (in English).

Bharadwaj, H. M., Verhulst, S., Shaheen, L., Liberman, M. C. & Shinn-Cunningham, B. G. Cochlear neuropathy and the coding of supra-threshold sound. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 8, 26. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnsys.2014.00026 (2014).

Shaheen, L. A., Valero, M. D. & Liberman, M. C. Towards a diagnosis of cochlear neuropathy with envelope following responses. J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 16(6), 727–745. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10162-015-0539-3 (2015).

Vasilkov, V., Garrett, M., Mauermann, M. & Verhulst, S. Enhancing the sensitivity of the envelope-following response for cochlear synaptopathy screening in humans: The role of stimulus envelope. Hear. Res. 400, 108132 (2021).

Gorga, M. P., Kaminski, J. R., Beauchaine, K. A. & Jesteadt, W. Auditory brainstem responses to tone bursts in normally hearing subjects. J. Speech Hear. Res. 31(1), 87–97. https://doi.org/10.1044/jshr.3101.87 (1988) (in English).

Bidelman, G. M., Pousson, M., Dugas, C. & Fehrenbach, A. Test–retest reliability of dual-recorded brainstem versus cortical auditory-evoked potentials to speech. J. Am. Acad. Audiol. 29(02), 164–174 (2018).

Van Der Biest, H., Keshishzadeh, S., Keppler, H., Dhooge, I. & Verhulst, S. Envelope following responses for hearing diagnosis: Robustness and methodological considerations. J. Acoust. Soci. Am. 153(1), 191–208 (2023).

Furman, A. C. et al. Noise-induced cochlear neuropathy is selective for fibers with low spontaneous rates. J. Neurophysiol. 110(3), 577–586 (2013).

Lobarinas, E., Spankovich, C. & Le Prell, C. G. Evidence of “hidden hearing loss” following noise exposures that produce robust TTS and ABR wave-I amplitude reductions. Hear. Res. 349, 155–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heares.2016.12.009 (2017).

Liberman, L. D. & Liberman, M. C. Dynamics of cochlear synaptopathy after acoustic overexposure. J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 16(2), 205–219 (2015).

Liberman, M. C. & Kujawa, S. G. Cochlear synaptopathy in acquired sensorineural hearing loss: Manifestations and mechanisms. Hear. Res. 349, 138–147 (2017).

Davis, R., Kozel, P. & Erway, L. Genetic influences in individual susceptibility to noise: A review. Noise Health 5(20), 19 (2003).

J. W. Hall, New handbook of auditory evoked responses, (No Title), 2007.

L. Gonzales, J. Wilson, S. Verhulst, and K. S. Henry, Detecting cochlear synaptopathy using envelope following responses in de budgerigar, in 46th Annual MidWinter Meeting (ARO 2023), 2023.