Abstract

Problematic soils pose challenges to light infrastructure, such as pavements, due to their swelling and collapse characteristics. Traditional soil stabilizers like cement and lime, while successful, have limits in cost, environmental impact, and energy use. This study explores agricultural and industrial byproducts as alternative stabilizers. It aims to determine the California Bearing Ratio (CBR) of stabilized soils using modern Machine and Deep Learning (MDL) techniques. MDL models used are Multivariate Adaptive Regression Splines (MARS), Artificial Neural Networks (ANN), M5P Model Trees (M5P-MT), Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), Locally Weighted Polynomials (LWP), and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks. Two modeling approaches were created: approach I with 12 input variables and approach II with 7. Key input variables were Atterberg limits, Ordinary Portland Cement (OPC), Optimum Moisture Content (OMC), Maximum Dry Density (MDD), dust, and ashes. Feature importance was assessed using Sklearn permutation importance and SHapley Additive Explanation (SHAP). Six statistical measures were used to assess model effectiveness: Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), RMSE-to-Standard Deviation Ratio (RSD), Variance Accounted For (VAF), 95% Uncertainty (U95), and Correlation Coefficient (R). All models had high prediction accuracy (R > 0.95), with method II being more straightforward. The LSTM model achieved the highest performance (R = 0.98; RMSE = 3.12), with XGBoost producing comparable results. The most influential variables, according to SHAP analysis, were OPC, additive type, and plasticity index. This study demonstrates the potential of Agricultural and Industrial Wastes (AIWs) in soil stabilization and the usefulness of MDL models, notably LSTM, in accurately predicting CBR levels.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Problematic soils, which include expansive, loose, and soft soils, pose considerable issues in infrastructure design and construction due to their unwanted engineering features, such as excessive settlement, swelling, and shrinking during moisture changes1. These soils, which frequently contain fine-grained clay minerals or other unstable compositions, can cause significant infrastructure damage if not properly stabilized2,3. Addressing these challenges necessitates soil stabilizing techniques that improve soil qualities and reduce the influence of moisture-induced volume changes, making them appropriate for construction purposes4,5.

To increase soil strength and stability, both traditional and new methods of soil stabilization have been investigated. These techniques range from mechanical stabilization, which raises soil density, to chemical stabilization, which uses additives to improve soil qualities. Mechanical stabilization involves the expulsion of air from soil cavities, resulting in densification, whereas chemical stabilization entails the insertion of chemicals to improve soil properties6,7. While traditional stabilizers such as cement and lime are widely utilized, concerns about their environmental impact, cost, and energy use during manufacture have fueled the hunt for sustainable alternatives8,9,10,11,12,13. Agricultural and industrial byproducts including rice husk ash, fly ash, and cement kiln dust are gaining popularity as ecologically benign and cost-effective soil stabilization solutions8,10,11,14,15,16. These materials can improve the engineering features of many soil types, providing viable alternatives for addressing the issues associated with problematic soils8,10,11,17.

Analysis or prediction of critical characteristics such as the California Bearing Ratio (CBR) is necessary for the design of sustainable pavement constructions, which are characterized by durability, strength, and stiffness18. The thickness of the pavement design directly correlates with the CBR value18,19,20,21. In the CBR test, a standard diameter plunger is placed into a compacted soil sample at a regulated rate, while the soil is at its Optimum Moisture Content (OMC)18,21,22. However, in order to reach the required OMC, it is necessary to immerse soil samples for a duration of four days, which makes the determination of soil CBR a time-consuming procedure18,19,20,21,23,24,25. Relying on samples obtained from a small number of sites may not provide a comprehensive representation of the whole road path, as soil engineering characteristics can change among various regions. Consequently, a substantial quantity of specimens is sometimes necessary, which increases the expenses of equipment and labor19,21. Hence, there is an urgent requirement for methods that allow the prediction of CBR using readily simple input parameters acquired from straightforward laboratory experiments19,20,21.

Machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) approaches are being used by academics in a variety of domains, including civil and geotechnical engineering, to predict desired parameters23,26,27,28,29,30. AI-based models have emerged as powerful tools for predicting CBR. These models employ a variety of techniques, including Artificial Neural Networks (ANN), Support Vector Machines (SVM), Multiple Linear Regression (MLR), Gene Expression Programming (GEP), Random Forest (RF), Gaussian Process Regression (GPR), Generalized Regression Neural Networks (GRNN), Multi-Layer Perceptron Neural Networks (MLPN), and Group Method of Data Handling (GMDH). Taskiran24 utilized both ANN and GEP models to build correlations between CBR values for fine-grained soils, reaching impressive accuracies of over 90% (R2 > 0.90) using 151 CBR test data points. Similarly, researchers have employed experimental data to build predictive models based on ANN, which have consistently shown significant accuracies (R2 values ranging from 0.76 to 0.99)22,23,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39. Sabat40 conducted an analysis of 49 CBR test data from stabilized soils and found that the SVM model performed satisfactorily, with an R2 value of 0.96. Taha et al.41 leveraged 218 experimental datasets to create a predictive model for CBR based on ANNs, achieving an impressive prediction accuracy of nearly 88% (R2 = 0.88). Tenpe and Patel25 developed SVM and GEP models using 389 soil test data, achieving peak accuracies of around 90% and 83%, respectively, as shown by R2 values. Table 1 presents a concise overview of the referenced literature, depicting the investigations together with the models employed and the number of datasets used to predict the CBR of geo-materials.

Previous research has primarily concentrated on estimating soil CBR using limited information and conventional modelling techniques. However, precisely predicting CBR values for soils stabilized with composite binder combinations continues to be a significant challenge, as exact mix design in practical applications is essential. While few research have examined CBR predictions for stabilized soils with different stabilizers, the complexities of numerous stabilizer combinations remain largely unexplored20. Moreover, many existing models suffer from overfitting due to small datasets, limiting their generalizability21.

To address practical engineering needs and bridge these gaps, this study utilizes a comprehensive dataset of 335 samples to evaluate several ML models (ANN, MARS, M5P-MT, LWP, XGBoost, and LSTM), using two approaches with 12 and 7 input variables, respectively. These models are selected for their unique advantages, including their ability to handle sequential dependencies, generate interpretable predictive formulas, or demonstrate strong regression performance in geotechnical applications. Specifically, ANN and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) were chosen for their proven efficacy in capturing non-linear relationships in soil mechanics data43; Multivariate adaptive regression splines (MARS) and M5P Model Tree (M5P-MT) for providing explicit, interpretable equations suitable for engineering design21,44; Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) for its robust ensemble learning and handling of multicollinearity in multivariate datasets45; and Locally Weighted Polynomials (LWP) for localized polynomial fitting to address variability in soil properties46. Input factors include Atterberg limits, Ordinary Portland Cement (OPC), Optimum Moisture Content (OMC), Maximum Dry Density (MDD), and various agricultural and industrial waste (AIW) materials used as stabilizers (e.g., dusts and ashes). Primary analyses quantify model accuracy using six statistical measures (R, RMSE, MAE, RSD, VAF, and U95) and use SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) to determine feature importance and to clarify the positive and negative effects of inputs on CBR predictions. This paper also proposes explicit, parsimonious, and accurate formulas using ML techniques (MARS and M5P-MT models) and compares them with previously published formulas using several evaluation criteria. The novelty of this work lies not in any single algorithm but in the dual-scheme framework and its practical validation: leveraging a relatively large, heterogeneous database we explicitly model full mix heterogeneity (approach I, 12 inputs) and provide a field-friendly parsimonious alternative (approach II, 7 inputs) that substantially reduces measurement burden while retaining near-equivalent predictive power. By combining high predictive performance, interpretable closed-form equations, and SHAP-based explanations, the proposed approach improves understanding of feature interactions, reduces overfitting risk associated with smaller/narrower datasets, and delivers immediately usable tools for engineers engaged in soil-stabilization design and decision making.

Theoretical overview

This section describes the specific approaches used in this study to apply machine and deep learning (MDL) models and evaluation matrices to predict the CBR of stabilized soil that contains AIWs. Figure 1 graphically illustrates the consecutive procedures carried out in this study to predict CBR, ending with the assessment and comparison of findings with previous studies. An extensive literature review was conducted to collect relevant data for this purpose. Finally, the gathered data underwent thorough cleaning and preprocessing to guarantee the development of an appropriate dataset for subsequent analysis. After calculating statistical measures such as mean, maximum, minimum, and standard deviation, and then visualizing the data graphically, the independent variables were classified into two groups to evaluate their individual effects on CBR prediction. The process of categorization enabled the accurate identification of key variables and the creation of a simplified model to improve the prediction accuracy. Initially, the dataset was partitioned into training and testing sets for each category using a 75/25 ratio. The K-fold cross-validation method was then employed only for the training set, which was divided into two subsets: one for training and the other for testing. The parameters of each MDL model were subsequently optimized through iterative procedures, depending on prior knowledge to attain the optimal results. These refined MDL models were evaluated using test data, with the prediction outcomes compared and assessed using various performance metrics.

Artificial neural networks (ANN)

ANN are flexible, data-driven function approximators that model complex, nonlinear relationships between predictor variables and target responses; they are therefore well suited to predicting soil properties and stability parameters in geotechnical problems47. In this study we employ feedforward networks comprising an input layer, one hidden layer with nonlinear activations, and an output layer. Networks are trained by optimizing connection weights and biases to minimize a loss function using back-propagation or equivalent optimizers.

Multivariate adaptive regression splines (MARS)

MARS is a non-parametric, data-adaptive regression method that represents the target as a sum of weighted piecewise linear basis functions (BFs). By partitioning the input space with knots and fitting local linear terms, MARS captures both nonlinear effects and interactions while remaining directly interpretable. Model construction proceeds in two stages: a greedy forward phase that introduces candidate BFs, and a backward pruning phase that removes terms to control complexity. Pruning is guided by generalized cross-validation (GCV), which balances lack-of-fit against model complexity by penalizing the number of BFs; the resulting coefficients are estimated by ordinary least squares. In practice we allow interactions up to the second order and tune the maximum number of BFs and the GCV penalty during cross-validation21,48.

M5P model tree (M5P-MT)

M5P-MT extends Quinlan’s M5 framework49 to combine decision-tree partitioning with local linear regression at the leaves, making it particularly suitable for heterogeneous engineering datasets. The tree is grown by selecting splits that maximise Standard Deviation Reduction (SDR) in the target variable; splitting continues until further SDR is negligible or node sample sizes fall below a threshold. Each terminal node is associated with a linear regression model fitted to that node’s subspace — the piecewise linear leaf models produce an overall nonlinear predictor through hierarchical segmentation. M5P-MT therefore offers a compact, interpretable compromise between global nonlinear models and purely local regressions, which is useful for capturing complex patterns while preserving some interpretability and computational efficiency50.

Locally weighted polynomials (LWP)

Locally Weighted Polynomial (LWP) regression is a nonparametric, local-fitting method for modeling complex, nonlinear relationships. Rather than estimating a single global function, LWP fits low-order polynomials to observations in a neighbourhood around each query point and weights those observations by proximity, which improves local prediction fidelity while limiting the influence of distant, potentially irrelevant samples. The locality is governed by a kernel and an associated bandwidth parameter that trade off adaptivity and sensitivity to noise; the polynomial order controls the degree of local curvature captured51.

Extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost)

XGBoost is used here as a scalable, regularized gradient-boosting tree ensemble that efficiently models complex, nonlinear relationships in tabular geotechnical data. Its objective combines a differentiable loss with explicit regularization on tree structure and leaf weights, and training uses an additive boosting procedure with second-order Taylor approximations to accelerate and stabilize optimization52. These properties—regularization, tree-based feature interactions, and computational optimizations—make XGBoost robust to overfitting and well suited to large, heterogeneous datasets encountered in engineering applications.

Long short-term memory network (LSTM)

Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) is a recurrent architecture originally developed to capture short- and long-range temporal dependencies in sequential data by controlling information flow through gated memory cells (input, forget, output). These gating mechanisms mitigate vanishing/exploding gradient problems encountered in simple Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) and improve learning over long sequences53. In this study we adopt an LSTM encoder composed of stacked LSTM cells, but we do not treat the dataset as a true temporal sequence; rather, each sample’s static predictors are presented to the network as a consistently ordered, index-ordered pseudo-sequence. Presenting features in this way lets the LSTM gates adaptively weight and combine feature contributions along the pseudo-sequence, enabling the network to learn hierarchical and cross-feature dependencies and nonlinear interactions that can be difficult for simple feedforward units to capture. For this reason, we frame the LSTM here as a flexible, gated feature extractor (a high-capacity nonlinear encoder) rather than as a literal temporal forecaster; this use of recurrent cells as surrogate encoders has precedent in recent studies54,55,56,57.

K-fold cross validation

The K-fold cross-validation technique is commonly used to evaluate the effectiveness of a model by measuring the accuracy of predictions25. During K-fold cross-validation the training set was divided into ten equal subsets (folds). In each iteration one fold served as the validation (hold-out) subset while the remaining nine folds were used to train the model; this was repeated ten times and the average validation error was used to compare candidate configurations. Importantly, all data preprocessing (scaling, encoding), feature selection steps and hyperparameter tuning/model fitting were performed strictly within the training folds during each iteration; the validation fold remained entirely hold-out at that iteration to prevent information leakage58,59,60. The final, selected model (the configuration with the lowest mean validation error) was evaluated once on the completely independent external test set (the reserved 25% that was never used for tuning or selection). The procedural stages required in K-fold cross-validation are illustrated in Fig. 2.

Step 1. Subset Extraction: The training dataset is partitioned into 10 equal subgroups. Each subset acts as a testing group once, while the remaining nine subsets are used for training.

Step 2. Model Training and Validation: The model is iteratively trained on nine folds and evaluated on the remaining (hold-out) fold in each cycle. All preprocessing steps, hyperparameter tuning, and model fitting were conducted strictly within the training folds; the validation fold was kept entirely hold-out to prevent data leakage.

Step 3. Error Calculation: The error is estimated in every iteration, and the average error is identified by cycling through all subgroups.

Step 4. Model Selection and Final Evaluation: After completing all ten iterations, the average validation error is computed, and the configuration with the lowest mean error is selected as the optimal model.

This systematic methodology guarantees the precise verification of the model, resulting in the determination of the most efficient model for subsequent analysis and implementation.

Software and reproducibility

The Python 3.6 programming language is employed in the present study for data processing. The code has been verified to produce identical results under Python versions ≥ 3.8. The study uses the Numpy61, Pandas, and Scikit-Learn packages (together referred to as the “Python science stack”), which provide a complete range of tools for data manipulation and analysis. The following key library versions were used:

NumPy: 1.19.5

Pandas: 1.1.5

Matplotlib: 3.3.4

Seaborn: 0.11.1

Scikit-Learn: 0.24.2

TensorFlow: 2.6.0

Keras: 2.6.0

XGBoost: 1.5.0

SHAP: 0.39.0

Variables are mostly expressed as percentages or in g·cm⁻³ and were inspected for scale compatibility (Table 2); therefore, no global rescaling was applied for tree-based models. To ensure fully reproducible splits and model initialization, we fixed a single random seed (SEED = 42) and applied it consistently: dataset shuffling and 75/25 split (random state = 42), K-fold (n splits = 10, shuffle = True, random state = 42) during cross-validation, and random state/seed or explicit RNG seeding for each model implementation (scikit-learn, XGBoost, TensorFlow/Keras). The minimal example in the Supplementary file (Supplementary code) demonstrates the exact seed-setting lines and commands needed to reproduce the results.

Performance evaluation of machine learning models

Evaluating our prediction models’ accuracy is essential for ensuring their dependability and efficacy. Researchers primarily utilized the correlation coefficient (R) and other error measures such as R-squared (R2), Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), and Mean Absolute Error (MAE) to assess the model’s effectiveness. However, depending exclusively on R² might be deceptive, as a perfect R² value (R² = 1) does not always indicate zero RMSE or MAE. Furthermore, the notion of a perfect predictive model (R2 = 1 and RMSE = MAE = 0) is an idealistic one. In this study, in addition to the generally used statistical metrics such as MAE, RMSE, and R, additional parameters were utilized to estimate the models’ prediction accuracy, providing a more thorough assessment of their performance. These parameters include:

1. Ratio of RMSE to Standard Deviation (RSD): RSD is the RMSE normalized by the variability of the observed target and measures model error relative to the scatter of observations. It is computed as:

where\(\:{T}_{exp,i}\) and \(\:{T}_{sim,i}\) are the ith observed and predicted CBR values respectively, \(\:{\stackrel{-}{T}}_{exp}\) is the mean of the observed CBR values, and N is the number of samples in the relevant split (test or validation). A lower RSD indicates better predictive accuracy; RSD < 1 means RMSE is smaller than the standard deviation of the observed data.

2. Uncertainty at 95% (U95): This metric signifies a 95% degree of confidence in predicting the uncertainty of a certain value or outcome. The estimate is derived as follows by calculating the standard deviation and RMSE of the data:

where \(\:\text{S}\text{T}\text{D}\text{E}\text{V}\) is the standard deviation of the residuals (the differences between the observed and predicted CBR values) and RMSE is as defined above. The factor 1.96 corresponds to the 95% coverage for a Gaussian error distribution; this formulation has been used widely in ML/regression model evaluation62,63.

3. Variance Accounted For (VAF): VAF is the percentage of variance in the observed data explained by the model. It is defined as:

This equation simplifies to VAF = 100% when the model predictions perfectly match the observations. A higher VAF (closer to 100%) indicates that the model explains more of the variance in the data.

In summary, RSD and VAF are scaled relative to the observed data’s variability, and U95 provides a confidence interval measure of predictive uncertainty.

Database analysis

The accuracy of predicting models in MDL applications is significantly affected by the extent and precision of the dataset used for training. The present investigation involved the compilation of a thorough dataset consisting of 335 records of CBR tests obtained from applicable literature into a structured database20,64,65,66. While these sources provide a geotechnically consistent dataset in terms of clay/clay–silt composition, the original papers do not always report identical location granularity, soil-classification codes, or complete test-protocol metadata (for example, soaked versus unsoaked CBR, exact curing periods, and specific specimen preparation details). To make provenance transparent we have compiled a short provenance table (Supplementary Table S3) that lists for each record: the original reference, reported location (city/state/country when available), basic soil description/class (when reported), and the key test-protocol flags (soaked/unsoaked, curing days, specimen notes). Fields not reported in the source are flagged as “NA”. These records were derived from studies focusing on problematic soils, predominantly composed of clay or clay-silt mixtures with moderate plasticity. For example, Rajakumar and Ready Babu66 sourced soil from Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu, Yadav et al. 53 obtained samples from Patna, Bihar, and Adhikary et al.65 collected soil adjacent to Jadavpur University. These studies were deliberately selected for their consistent use of base soils with similar geotechnical properties and for employing AIWs as stabilizers, thereby providing a robust foundation for evaluating their effects on CBR values.

To provide a detailed breakdown of the dataset for assessing model generalizability, the 335 CBR records include 30 unstabilized control samples (9.0%, with no AIWs or OPC added) and 305 stabilized samples (91.0%). Among the stabilized samples, AIW type distribution (noting overlaps due to combinations in 60 samples, or 17.9%) is as follows: Saw Dust Ash (SDA) in 89 samples (26.6% of total dataset), Quarry Dust (QD) in 76 (22.7%), Rice Husk Ash (RHA) in 16 (4.8%), Granulated Ash (GA) in 60 (17.9%), Bagasse Ash (BA) in 60 (17.9%), and Calcium Ash (CA) in 60 (17.9%), reflecting a focus on abundant agricultural wastes like SDA and QD while incorporating synergistic mixes.

The CBR of stabilized soils is affected by several elements, such as Atterberg limits (Liquid Limit (LL), Plastic Limit (PL), and Plasticity Index (PI)), as well as indices associated with compaction characteristics (OMC and MDD). Moreover, the existence and amount of soil stabilizing substances, such as Ordinary Portland Cement (OPC) and other AIWs, are essential factors in determining the strength properties of the soil. Table 2 presents comprehensive data on the input variables, together with the output variable of CBR.

The visualization of the dataset through a hex contour graph (Fig. 3) depicts how CBR values are distributed with respect to input variables. CBR values predominantly fall within the range of 2% to 67%, with and without the incorporation of AIWs. Notably, LL values primarily range from 20% to 60%, with a concentration between 30% and 50%, while PL values generally range from 15% to 30%, with a smaller subset around 35%. The PI varies widely, typically ranging from 5% to 30%, with a notable concentration observed around 10%. Similarly, OMC values exhibit considerable variability ranging from 10% to 30%, while MDD values range from 1.4 to 1.8 g/cm³, with a peak occurrence at 1.5 g/cm³. Cement content ranges from 2 to 8%, across three different percentages of incorporation, while AIW materials such as CA, BA, GA, SDA, QD, and RHA vary in content from 0 to 60%, 0–12%, 0–12%, 0–20%, 0–20%, and 0–35%, respectively.

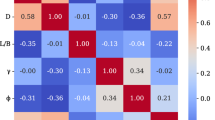

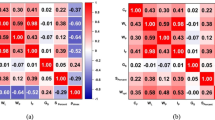

Figure 4 presents the correlation matrices illustrating the relationships between input and output variables in the dataset. The chart shows significant correlations between PI, SDA, OPC, OMC, and the CBR value. Soils with high PI typically have greater clay content, which influences their compaction behavior and response to stabilization. PL and OMC are critical indicators of the soil’s moisture characteristics, with proper moisture levels facilitating optimal interactions between soil and stabilizers, thereby improving CBR. Among the input variables, OPC shows a stronger correlation with CBR, followed by SDA and then QD. This is attributed to the hydraulic cementing properties of OPC and the pozzolanic activity of SDA, which together contribute to the formation of a denser and more cohesive soil matrix, enhancing strength under loading conditions. Several stabilizer variables in the database are strongly zero-inflated; for example, OPC has Q25 = Q50 = 0 (Table 2), indicating that many samples contain no cement. To account for this distributional feature, rank-based (Spearman) correlations—which are less sensitive to ties and the heavy mass at zero—were also computed to assess robustness. The results confirm that the relationship remains strong even after accounting for zero inflation (Spearman R ≈ 0.8), consistent with the Pearson estimate (≈ 0.9). These findings suggest that the overall OPC–CBR relationship reflects both a presence/absence (binary) component and a dosage-dependent effect. Accordingly, we interpret OPC–CBR correlations with caution and note that, where possible, models should include an OPC-presence indicator (OPC > 0) or explicitly address zero-inflation and heteroscedasticity to distinguish binary from continuous dosage effects. While moderate correlations are observed between OMC and various stabilizing agents, the overall interrelations among input variables remain modest, highlighting the importance of incorporating all variables in the modeling process to achieve higher predictive accuracy.

Two separate modeling strategies, referred to as approach I and approach II, have been developed, taking into account the specific characteristics and quantities of soil stabilization materials. While both models integrate Atterberg limits and compaction characteristics, approach I treats specific volumes of AIWs as independent input variables, resulting in 12 input variables (as shown in Table 2; Fig. 4). In contrast, method II combines the categories of AIWs and their total volume percentages, resulting in 7 input variables (ToA, MDD, PI, OMC, PL, LL, and SM). The motivation of establishing method II, despite its potentially poorer accuracy compared to approach I, comes in valuing parsimony. A simplified model not only assists in explaining the physical rules controlling the situation but also promotes interpretability and generalizability. Moreover, selecting for a less sophisticated model mitigates the danger of overfitting, rendering the model more resilient to noise and disturbances while permitting simpler maintenance and analysis67. This parsimony is quantified in the accompanying parameter-count table (Table 3), which shows that approach II reduces effective parameter counts by 32–68% across the top models (32% for MARS, 39% for XGBoost, 45% for M5P-MT and 68% for LSTM); the table also lists the counting rule used for each model to ensure transparency. Through a systematic examination of the interaction between different input factors and their influence on CBR values, this study improves understanding of soil stabilization processes and enables the development of reasonable prediction models for engineering applications.

Approach II was developed as a deliberately parsimonious, field-friendly alternative to the full 12-variable model. The reduced set was chosen to preserve the dominant physical controls on CBR (compaction state, soil plasticity, and the presence/amount of stabilizer) while (a) collapsing strongly zero-inflated and overlapping additive variables into a single, low-dimensional additive indicator (ToA) to avoid sparsity, and (b) removing empirical redundancy that inflates variance and harms generalization. Empirically, approach II effectively reduces parameter counts (see Table 3) and markedly lowers multicollinearity (VIF diagnostics, Table 6), while producing comparable test-set performance (Table 5) and improved residual stability (tighter model cluster in the Taylor diagram and reduced heteroscedasticity). Furthermore, SHAP analysis confirms that the reduced predictor set retains the key causal drivers (ToA, PI, MDD, OMC) identified by the full model, which explains why prediction accuracy remains high despite the smaller input set. For practical use, we also supply explicit algebraic formulas for the simplified models (MARS and M5P–MT) in the Supplementary Material so engineers can apply approach II without extensive laboratory measurement.

Results and discussion

This section presents an evaluation of the performance of several MDL models (ANN, MARS, M5P-MT, LWP, XGBoost, and LSTM) in predicting CBR of stabilized soils with AIWs. The statistical metrics R and RMSE are given for each model in both approaches (I and II), enabling a comparative analysis of their strengths and weaknesses. Furthermore, the results are contextualized within prior research to emphasize the novelty and significance of this work. Moreover, SHAP analysis ranks input variables according to their impact on CBR, providing more profound understanding of the factors influencing model predictions.

Selection of the number of folds

The number of folds in K-fold cross-validation has significant impact on model precision and reliability. Figure 5 depicts the significant effect of different k values (k = 2, k = 5, and k = 10) on model performance metrics, with a special focus on reliability and accuracy. The figure compares different k values to highlight the impact on two critical performance indicators of R and RMSE. As the value of k increases, model accuracy improves considerably, as seen by higher R and lower RMSE values, with k = 10 showing highest improvements. Notably, at k = 10, the LSTM model outperforms, reaching a R value of 0.99, a considerable increase over k = 2. These findings emphasize the efficacy of k = 10 in robust model evaluation, offering excellent precision as well as reliability across the six models examined in the study.

Performance evaluation of machine learning models

This section provides a comprehensive analysis of six different MDL models (ANN, MARS, M5p-MT, LWP, XGBoost, and LSTM) against two different approaches, examining their performance in predicting CBR. Approach I and approach II vary in hyperparameters, which affect model complexity and fit to the data. Generally, approach I demonstrates a superior fit across most models, while approach II excels in simplicity and generalizability, enhancing interpretability and robustness in model performance. Based on test-set results, LSTM is marginally best while XGBoost shows comparable performance.

Table 4 presents a detailed comparison of six CBR models (ANN, MARS, M5p-MT, LWP, XGBoost, and LSTM) across two approaches, elucidating their efficacy in CBR prediction. Approach I utilizes distinct hyperparameters, including variations in hidden layers and neurons, in contrast to approach II, suggesting possible differences in model complexity. Although approach I often demonstrates a lower GCV score, indicating superior data fit, approach II highlights simplicity and improved generalizability. Key variations in hyperparameters encompass the quantity of BFs, tree depth, polynomial degree, and dropout rate in both approaches, affecting the model’s complexity and efficacy. Despite these variations, common strategies include using the Adam optimizer and maintaining a uniform batch size to enhance training efficiency and generalization. Overall, while approach I often shows superior fit across models, the simplicity and interpretability of approach II improve resilience in model performance.

Table 5 provides a comprehensive comparison of six modeling methods (ANN, MARS, XGBoost, LWP, M5P-MT, LSTM) during the training and testing stages in both approaches I and II. Key metrics such as R, RMSE, MAE, RSD, U95, and VAF are analysed to evaluate the performance of each model. In the training phase, XGBoost demonstrates the highest performance (R = 0.99) with exceptional precision and credibility, especially in approach I. In approach II, XGBoost and LSTM exhibit dominance, although other models provide comparable performance. In evaluations, LSTM is marginally best while XGBoost shows comparable performance; differences are small and lie within expected uncertainty. In contrast, LWP models demonstrate the poorest performance, especially in approach I. In approach II, this gap is minimal, with outcomes closely converging. XGBoost, M5P-MT, MARS, and ANN models showed reasonable performance in testing, signifying successful learning and appropriate application capacities. The results indicate a slight preference for the LSTM, yet the proximity of performance metrics means XGBoost remains a comparable modelling choice.

Figures 6 and 7 show scatter plots of the predicted CBR values obtained by six models (ANN, MARS, M5P-MT, LWP, XGBoost, and LSTM) versus observed CBR values for approaches I and II, respectively. These visual representations conform to the statistical metrics (R, RMSE, MAE, RSD, U95, VAF) shown in Table 5. Each figure has a regression line written as y = Ax + B, where the A and B constants represent model accuracy68,69. A perfect match between predicted and measured CBR values would result in A and R values of 1 and a B value of 0. Across both the training and testing phases, the slopes of the plots for all models nearly align with the target value of one, indicating that there are few instances of misaligned CBR estimates. However, the constant B varies across approaches I and II, with higher values being recorded in the latter. Furthermore, whilst most models obtain A values near to one, the LWP model in approach I deviates with a value of 0.88. The disparity of estimated results is more evident in approach II than in approach I, with the LSTM model showing the least variation. Despite these discrepancies, the statistical indices together demonstrate that all forecast outcomes are remarkably similar to the observed data. The LSTM produced accurate estimates, showing strong correlations and low RMSE values, indicating it is a competitive, high-capacity nonlinear predictor for these data; however, differences against other top performers (notably XGBoost) are modest, so LSTM should be interpreted as one effective modelling choice for CBR prediction.

Comparison of observed and predicted CBR outputs during training (blue color) and testing (orange color) phases for approach I. Solid black line = 1:1 identity (perfect prediction); dashed line in each panel = ordinary least-squares fit (y = Ax + B). Fitted parameters (training-phase) are: ANN (A = 0.90, B = + 1.76), MARS (A = 0.98, B = + 0.35), M5p-MT (A = 0.96, B = + 0.65), LWP (A = 0.89, B = + 0.99), XGBoost (A = 0.97, B = + 0.39), LSTM (A = 1.02, B = − 0.49).

Comparison of observed and predicted CBR outputs during training (blue color) and testing (orange color) phases for approach II. Solid black line = 1:1 identity (perfect prediction); dashed line in each panel = ordinary least-squares fit (y = Ax + B). Fitted parameters (training-phase) are: ANN (A = 0.96, B = + 3.7), MARS (A = 0.96, B = + 0.67), M5p-MT (A = 0.92, B = + 1.26), LWP (A = 0.94, B = + 1.02), XGBoost (A = 0.96, B = + 0.53), LSTM (A = 0.95, B = + 2.11).

Figures 8 and 9 demonstrate a comparison between the observed CBR dataset (represented by the black line) and the estimated values from the six proposed models in both techniques (indicated by the blue line) during the testing phase. The Relative Absolute Error (RAE) is likewise depicted in green. The LSTM and XGBoost models demonstrate the most accurate alignment between predicted and measured CBR values, showing the lowest computed error in both approaches. In contrast, the ANN model exhibits the most disparities in CBR prediction, with errors constantly surpassing those of other models at all data points, especially in approach II.

Figure 10 illustrates a Taylor diagram, which provides a graphical representation of RMSE, R, and model standard deviation for the comparison of multiple models. The model standard deviation is depicted along the x- and y-axes, with R values indicated by black dashed lines and RMSE values by dotted purple lines. Each model is represented as a point on the diagram, with the corresponding CBR value indicated along the x-axis. The model nearest to the x-axis, reflecting the lowest standard deviation and RMSE, is deemed optimal. Both approaches demonstrate that all models possess strong predictive capability, with R values consistently exceeding 0.95. The LSTM model demonstrates a higher correlation and lower standard deviation relative to other models (ANN, MARS, M5P-MT, LWP, XGBoost), emphasizing its enhanced predictive accuracy. Numerically, the test-set results show that the mean ± standard deviation of RMSE across models is 3.68 ± 0.67 for approach I and 4.14 ± 0.49 for approach II, while mean R is 0.973 ± 0.009 and 0.970 ± 0.006 for approaches I and II, respectively (computed from Table 5). The Taylor diagram reveals that approach II produces a noticeably tighter cluster of model points (lower dispersion in R, model standard deviation, and RMSE), indicating that the different modelling families agree more closely in their variability and error. This convergence is consistent with the deliberately parsimonious predictor set in approach II (7 inputs) and the substantially reduced multicollinearity (lower VIFs reported in Table 6), which together reduce between-model variance and improve robustness to new data70. By contrast, approach I (12 inputs) permits some individual models (for example LSTM and XGBoost) to achieve lower best-case RMSE but also shows larger between-model scatter; this pattern reflects higher sensitivity to redundant predictors and therefore an increased risk of overfitting unless additional regularization or external validation is applied. In practical engineering terms, the tight cluster observed for approach II supports using its models for initial screening or field-level estimates (fewer inputs, more consistent outputs), whereas approach I models—trained with rigorous cross-validation—are better suited to laboratory or case-specific applications where the lowest possible error is required and the full predictor set can be measured reliably.

Residual diagnostics and uncertainty

To further evaluate model assumptions, residual diagnostics, and predictive uncertainty, residuals versus predicted CBR values were plotted for all MDL models on the test sets under both approaches (Fig. 11). In approach I (top row), models such as LSTM and XGBoost display mild heteroscedasticity (non-constant variance), characterized by increasing residual variance at higher predicted CBR values, which may indicate elevated uncertainty in upper CBR ranges and contribute to slightly higher RMSE in upper CBR ranges. In contrast, approach II (bottom row) exhibits improved residual distributions overall, with the LSTM model showing particularly stable variance across the CBR range (Lagrange Multiplier (LM) statistic ≈ 30, p = 0.002), suggesting enhanced robustness and reduced sensitivity to CBR magnitude. Outliers are minimal and non-systematic across all models, bolstering prediction reliability within the observed CBR range (2% to 67%). This analysis complements the 95% uncertainty (U95) metric by elucidating patterns in residual structure, thereby reinforcing that approach II achieves a favourable balance of accuracy, interpretability, and parsimony.

Model parsimony and collinearity analysis

To quantify the trade-off between model complexity and generalizability we performed collinearity diagnostics and information-criterion comparisons for the two approaches. Pairwise correlation heatmaps (Fig. 12) and Variance Inflation Factors (VIF) (Table 6) show pronounced multicollinearity among several raw predictors in approach I (notably PI, LL and PL; several VIFs > 40 and PL ≈ ∞ because of algebraic dependence), whereas the reduced predictor set of approach II substantially lowers redundant information. Information-criterion comparisons computed from the fitted models further indicate that approach I attains better in-sample fit (Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) = 2096.05, Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) = 2141.82, R² = 0.85) but approach II achieves comparable explanatory power given its simplicity (AIC = 2210.24, BIC = 2236.93, R² = 0.79). Taken together, these diagnostics justify presenting both approaches: approach I for maximal predictive accuracy when all inputs are available, and approach II as a robust, interpretable alternative with modest loss in performance and reduced measurement burden.

MARS and M5P-MT models explicit formulas

Figure 13 shows a comparison of MARS model performance in predicting CBR using approaches I and II. Using half as many effective parameters as approach I and around half as much time for computation and execution, approach II clearly is the simpler and more efficient method, even if it achieves somewhat lower accuracy than approach I. The GCV for approach II is marginally higher than that of approach I. It is remarkable that approach II requires much less time and effort while maintaining such a high degree of accuracy. While both approaches show comparable accuracy (albeit somewhat lower in approach II), approach I is less successful due to its time-intensive nature and reliance on additional parameters.

The explicit formulations derived from the MARS model for approaches I and II are provided in a supplementary file (Table S1). Approach I uses 27 BFs with designated coefficients for CBR prediction, while approach II employs a simplified formula with 18 BFs, reducing computational complexity. Similarly, the explicit formulas obtained from the M5P-MT model for both approaches are presented in the supplementary file (Table S2). For clarity and practical use, a representative, compact example and a short-worked demonstration are presented herein. MARS models are additive combinations of hinge (spline) BFs and an intercept:

where each basis function \(\:{BF}_{i}\) is a hinge/spline term of the form max (0;\(\:\:{x}_{j}\) – t) or max (0;\(\:\:{\text{t}-x}_{j}\)). A representative MARS expression (approach II) is:

The M5P-MT output is a set of piecewise linear models (one linear model per tree leaf); for example, one representative leaf model (approach II, LM1) is:

And the full set of leaf equations is provided in Table S2. Both forms are algebraic and directly usable by practitioners (only substitution of measured input values into simple arithmetic expressions is required). For a concrete demonstration using the MARS basis functions from approach II, \(\:{x}_{1}\)= 5 and \(\:{x}_{3}\) = 8. are assumed. From Table S1 it is found that:\(BF_{1} = \max \left( {0,~x_{3} - 4} \right) = \max ~\left( {0,~8 - 4} \right) = 4~and~BF_{2} = \max ~\left( {0,~7.2 - x_{1} } \right) = \max ~\left( {0,~7.2 - 5} \right) = 2.2.\) Substitution of these values into the approach II MARS intercept and BF coefficients yields:

If all other BFs are evaluated as zero (as is common in sparse MARS models), CBR ≈ 335.02 is predicted; when other BFs are nonzero they are computed in the same way and are added using their coefficients — i.e., the full prediction is obtained by straightforward arithmetic. These computations can be implemented trivially in a calculator, spreadsheet, or simple script, which renders both the MARS and M5P-MT outputs directly feasible for routine engineering use. The full lists necessary for reproducible, operational use are provided in the Supplementary Tables.

Figure 14 illustrates the decision tree structure of the model, delineating the requirements at each leaf node that determine CBR. The equations for each leaf node express the correlation between input characteristics and the forecasted CBR. Notably, discrepancies in criteria and coefficients between the two approaches lead to divergent formulae for CBR prediction. In summary, approach II offers a streamlined and more efficient model structure while maintaining high predictive performance.

Feature importance analysis for CBR prediction using SHAP method

The present study evaluates the impact of individual input parameters on the CBR of stabilized soil through the utilization of feature importance analysis, particularly the SHAP method. By evaluating feasible feature combinations, SHAP, which is based on the well-established game theory, assesses the unique contribution of individual input parameters. The average impact of each input variable is represented by SHAP values, with higher SHAP values indicating more influence on the model’s predictions. The general feature impact is determined by calculating the mean of SHAP values across all data points and subsequently sorting these values in descending order71. The arranged SHAP values are represented on the horizontal axis of the importance diagram, while the respective input variables are indicated on the vertical axis.

Figure 15 presents the SHAP values and feature importance associated with the XGBoost model employed for predicting the CBR of stabilized soil. The mean-SHAP ranking for approach I shows that OPC and PI are the most influential predictors, consistent with previous research42,72. This ordering is consistent with fundamental geotechnical mechanisms: OPC acts as a hydraulic binder whose hydration produces portlandite (Ca(OH)₂) and subsequently calcium-silicate-hydrate and calcium-aluminate-hydrate phases (C–S–H and C–A–H), which cement soil particles into a stiffer, higher-strength matrix and therefore markedly increase CBR73. In contrast, a higher PI denotes a larger fraction of clay-sized, water-sensitive fines that raise water demand, reduce achievable dry density and interparticle friction, and hence tend to lower bearing capacity and CBR74. MDD and OMC influence compaction-driven contact and shear resistance—higher MDD and appropriately matched OMC generally yield positive effects on CBR—while QD primarily acts as a granular filler that increases packing and dry density. Other stabilizers (RHA, BA, GA, SDA, CA) can contribute via two pathways depending on dosage, curing and alkalinity: (i) as fine fillers that reduce voids and PI and/or (ii) as reactive pozzolans that, when enough Ca(OH)₂ (from OPC or Ca-rich additives) and curing moisture are present, form secondary C–S–H/C–A-H phases and locally boost strength1. These mechanistic interactions, together with differences between soaked and unsoaked responses (where soaking can reduce apparent cementation and highlight fines-sensitivity), explain why OPC and PI dominate the global SHAP importance while many additives show smaller average SHAP values yet produce strong local effects in specific mixtures and curing states.

The summary plot (right) in approach I visually represents SHAP values for each dataset instance, with the colour scale denoting feature values (red for high and blue for low). The horizontal axis represents the SHAP values, and the distribution of points (red and blue) illustrates the direction of influence. The presence of additional red points on the right side for stabilizers such as RHA, CA, GA, QD, SDA, and BA indicates that increased values of these materials have a positive effect on CBR predictions. The blue points on the left side for OPC suggest that decreased OPC values lead to a reduction in the predicted CBR. Denser red points on the right side for OPC indicate that higher OPC values typically correlate with increased CBR, although some exceptions are noted. Increased OMC values enhance soil compaction, resulting in elevated CBR, whereas higher PI values signify greater soil plasticity, which typically reduces CBR.

The SHAP force graphic (middle and bottom) offers insight on individual estimations by demonstrating the influence of each variable. In this scenario, f(x) represents the estimated CBR values, which are 5.29 for approach I and 5.92 for approach II. Red arrows reflect variables that increase CBR, with larger arrows suggesting a higher influence, while blue arrows represent variables that reduce CBR. In approach I, OPC and PI had the largest blue arrows, indicating the most substantial lowering impact with mean SHAP values of −10.66 and − 0.95, respectively. MDD and BA have the largest red arrows, suggesting a significant positive influence. In approach II, ToA (Type of Additives) and PI are the most influential in reduction of CBR, whereas MDD and OMC have a beneficial influence. ToA and PI have mean SHAP values of −9.35 and − 0.88 when ToA is 4 and PI is 9.5.

To provide deeper insight into feature effects, we show two SHAP dependence plots for key compaction-related predictors (Fig. 16a,b) and the complete mean-absolute SHAP interaction matrix (Table 7), which together quantify directionality and conditional effects. The MDD dependence plot (Fig. 16a; coloured by PI) reveals a generally monotonic positive relationship: higher MDD increases the SHAP contribution to predicted CBR, indicating that denser packing and higher contact stresses systematically raise bearing capacity. Colour stratification shows this positive MDD effect is moderated by PI — higher PI values tend to reduce the magnitude of MDD’s positive contribution — suggesting a physical interaction in which high-plasticity fines limit the benefit of improved dry density.

The OMC dependence plot (Fig. 16b; coloured by PL) shows SHAP contributions becoming more positive at moderate-to-high OMC (consistent with compaction toward an optimum), while PL shifts the local response and helps explain some scatter at the upper end of OMC. These visual findings are supported quantitatively by the mean-absolute SHAP interaction matrix (Table 7): ToA has the largest interaction magnitude (16.047) and a notable interaction with PI (1.974), indicating strong conditional effects of additive type on other predictors. By contrast, MDD and OMC show relatively small off-diagonal interaction magnitudes and modest self-terms (MDD = 0.255, OMC = 0.222), consistent with largely additive main effects that are nonetheless subtly modulated by plasticity and additive type. Overall, the dependence plots and interaction matrix indicate model predictions are driven mainly by strong main effects (OMC, MDD, PL/PI) with only limited pairwise coupling. Because the final XGBoost model can learn nonlinear and higher-order interactions, the absence of widespread, strong SHAP interactions suggests these patterns reflect underlying physical relationships in the dataset rather than a model deficiency.

In summary, approach I reveals that OPC and PI exert the most influence on CBR predictions, whereas CA, GA, QD, SDA, and BA have lesser effects. Conversely, approach II indicates that ToA and PI have more influence, whereas other stabilizing additives and characteristics such as MDD and OMC are of smaller significance in this study. This extensive SHAP study offers insights into the contributions of several variables in CBR prediction, facilitating the identification of key elements and their impacts on soil stabilization results.

Comparison with previous studies

This study leverages an extensive database and advanced MDL methods to estimate CBR for soils stabilized by AIWs. It provides explicit prediction formulae and exhibits higher precision and resilience over previous techniques by employing models such as ANN, MARS, M5P-MT, LWP, XGBoost, and LSTM, as well as studying feature importance using SHAP analysis. While the comparisons presented highlight the advancements of the current study, it is acknowledged that differences in datasets and preprocessing methods across prior research may introduce variability, and a direct comparison using re-trained models on a unified dataset remains a potential avenue for future work to ensure a fair and uniform benchmark evaluation. The following compares the findings of this study to those of previous ones, underlining the advances and contributions made.

Table 8 presents a summary of the performance of different ML models applied in prior research and the current study for predicting the CBR, an essential parameter in pavement design. The primary metrics include the reference study, employed ML model, dataset size, input variables, presence of explicit prediction formulas, R and RMSE values, and the CBR range within the dataset. To enable a fairer comparison across studies, two additional metrics were calculated for all studies in Table 8: the dimensionless unexplained-variance fraction \(\:U=\:\sqrt{1-{R}^{2}}\) and a normalized RMSE expressed as a percentage,

The U statistic facilitates comparison of explained variance independent of data scale, while NRMSE minimizes the influence of differing CBR ranges that can make absolute RMSE values misleading. When a prior study reports RMSE on a normalized output scale (e.g., scaled to [0, 1]), NRMSE cannot be computed on the absolute CBR scale and is therefore indicated as ‘–’ in Table 8. These normalized parameters provide a more meaningful basis for comparing model accuracy and predictive error across heterogeneous datasets. They yield a fairer and more interpretable benchmark because a low absolute RMSE in a study with a narrow CBR range may not represent superior model performance compared with a higher RMSE obtained from a study spanning a much wider range. Normalization therefore “levels the playing field” by representing the relative error rather than the absolute one.

Most studies reported RMSE on the original (absolute) CBR scale, with no indication of output normalization except in one case. Notably, Bardhan et al.21 reported an RMSE of 0.074 on normalized outputs, which prevents direct computation of NRMSE on the absolute scale. Their low RMSE value reflects the [0, 1] scaling rather than smaller absolute prediction errors relative to their CBR range (5.2–10.2). As shown in Table 8, our M5P–MT model achieved U = 0.199 and NRMSE = 2.96%, outperforming most previous models (e.g., U = 0.493 and NRMSE = 11.30% for Ikeagwuani20, U = 0.415 and NRMSE = 11.08% for Khasawneh76 and remaining competitive with the best reported cases (e.g., U = 0.141 and NRMSE = 1.42% for Ahmad et al.18), despite the larger and more diverse dataset used in this study.

Several prior research did not include explicit formulae for CBR prediction. Bardhan et al.21 employed 312 datasets from India to obtain a U of 0.312 and an RMSE of 0.074 (on a normalized dataset scaled [0,1]) using MARS method. The study’s limited geographical distribution and narrow CBR range (5.2 to 10.2) compromised its application even with its high accuracy and the straightforward formula with just eight input variables. Similarly, Katte et al.19 used 33 datasets from Central Africa for developing an explicit formula with seven input variables and a U value of 0.415. However, the study lacked error metrics beyond R and was confined by a small, geographically specialized dataset and a limited CBR range (14–50). Our study sourced data from different regions characterized by problematic soils (predominantly clay or clay-silt), and a wider CBR range, thereby ensuring a more diverse yet geotechnically consistent dataset.

Khasawneh et al.76 utilized 110 data samples along with eight input variables, resulting in a U value of 0.415 and an NRMSE of 11.08% across an extensive CBR range (2 to 98). However, this investigation expanded soil characteristics artificially by incorporating sand into a restricted number of samples, which may undermine the representativeness of the natural soil. Our study addresses all these limitations by utilizing a broad dataset and examining the significance of input features through SHAP analysis, employing MARS and M5P-MT models. The M5P-MT model exhibited exceptional accuracy, achieving a U of 0.199 and an NRMSE of 2.96%.

The prior studies utilizing models such as LSTM, RF, GPR, MARS, MLR, and ANN demonstrated different levels of accuracy, with U values ranging from 0.141 to 0.493 and NRMSE values varying from 1.14% to 15.22%. Ho and Tran42, leveraging 290 datasets and an RF model, achieved remarkable accuracy (U = 0.141, NRMSE = 3.69%). This study emphasized the importance of PI and cement as key input variables, aligning with the presented findings. Ahmad et al.18, using 121 datasets and seven input variables, attained a notable accuracy (U = 0.141, NRMSE = 1.42%), highlighting RHA as a key predictor, which contrasts with the findings of the current study. Khatti and Grover75 employed LSTM across 283 datasets, attaining a U of 0.199 and an NRMSE of 1.14% over a wide CBR range (1.1 to 81.3), but did not offer a CBR formula. Ikeagwuani20 used 109 datasets with an RF model, achieving a U of 0.493 and NRMSE of 11.29%, without offering an explicit formula or input ranking. Rajakumar and Reddy66 employed ANN with 210 samples, achieving a U of 0.341 and NRMSE of 15.22%, but did not identify predominant input variables or provide a simple prediction formula.

Using 335 samples and employing two modeling approaches (one incorporating 12 input variables and the other utilizing seven), this study demonstrated superior accuracy compared to numerous prior ones. This research presents a thorough and precise approach for predicting CBR across diverse soil conditions. It addresses the shortcomings of earlier research by utilizing extensive datasets, providing explicit formulas, and applying SHAP analysis to clarify the importance of input variables. This improves the model’s usefulness and reliability for different soil stabilization situations.

Limitations and future directions

This study demonstrated impressive predictive accuracy for CBR through the application of advanced MDL models; however, there remain numerous opportunities for enhancement and deeper investigation. The existing dataset comprises 335 records was derived from studies on problematic soils, primarily clay or clay–silt mixtures with moderate plasticity, collected from regions such as Coimbatore, Patna, and areas near Jadavpur University. While comprehensive, this dataset needs to be expanded to include a wider range of soil types and additional geographic regions. Doing so will improve the models’ generalization capability and robustness under varying soil conditions. We acknowledge the limited geographic and soil-type diversity, as well as variability in CBR testing protocols across the source studies (see Supplementary Table S3). Full harmonization was not possible when source reports lacked complete protocol details; these missing items are explicitly flagged in Supplementary Table S3. To mitigate potential bias arising from between-study heterogeneity, we applied 10-fold cross-validation and two independent modeling approaches to evaluate model robustness. We also recommend future targeted data collection with harmonized protocols (curing, compaction, soaked/unsoaked) and protocol-level sensitivity analyses.

Despite strong overall performance, several limitations warrant attention. Prediction errors increase at the tails of the CBR distribution: very low CBR (≲ 5%) and very high CBR (≳ 40%) exhibit larger residuals than mid-range values, likely reflecting sparse representation in these ranges and stronger nonlinear behaviour at the extremes. Likewise, samples with very high plasticity indices or atypical particle-size gradations produced larger errors, suggesting the models generalize better to typical clay–silt behaviours than to highly plastic or unusually graded soils. The dataset is also mildly skewed toward mid-range CBR values, which may bias model performance toward the most common cases and reduce accuracy on outliers. Finally, heterogeneity in laboratory CBR procedures and sample preparation across source studies (Supplementary Table S3) introduces additional uncertainty that can limit transferability to external datasets and field conditions. We also acknowledge that applying LSTM architectures to index-ordered (non-temporal) data presents interpretability challenges, as recurrent activations are less intuitive to analyse than in true time-series contexts. Accordingly, the LSTM model in this study is treated primarily as a high-capacity nonlinear feature extractor, with its outputs interpreted alongside the transparent MARS and M5P formulations rather than as evidence of temporal causality.

To guarantee practical applicability, it is essential to validate the predictive models using real-world field data. This step is essential to validate their performance across different environmental conditions. Moreover, the models rely on parameters assessed in controlled environments, which might not entirely reflect the variability present in real-world scenarios. An in-depth evaluation of the environmental implications and economic viability of employing AIWs is essential to address practical concerns. Further studies should explore how curing time and conditions impact the CBR of stabilized soil, as these elements play a crucial role in determining long-term performance. Investigating a wider range of AIWs and their combinations is crucial, as this may reveal the most effective stabilizing mixtures for enhancing soil quality. Furthermore, assessing the longevity of stabilized soils through AIWs across prolonged durations and varying loading and harsh climatic scenarios (consecutive wet-dry and freeze-thaw cycles) will yield significant insights for the design and maintenance of infrastructure. Ultimately, the creation of hybrid models through the integration of various MDL techniques could improve predictive accuracy and robustness, which may result in reliable CBR estimations. By tackling these limitations and broadening the research scope, we will enhance our comprehension of soil stabilization through AIWs and encourage the use of advanced MDL techniques, thereby making a substantial contribution to sustainable infrastructure development and the optimization of soil stabilization practices.

Conclusions

The study primarily aimed to improve the predicted accuracy of the California Bearing Ratio (CBR) for expansive soils stabilized with Agricultural and Industrial Wastes (AIWs) by utilizing sophisticated machine and deep learning (MDL) models. Key findings are:

-

High Predictive Accuracy: All MDL models attained strong test performance (R > 0.95). For the 12-input scheme (approach I) LSTM performed best on held-out data (R = 0.99, RMSE = 2.82, MAE = 1.51, U95 ≈ 31.06), with XGBoost close behind (R = 0.98, RMSE = 3.17, MAE = 1.70, U95 ≈ 31.23). For the 7-input scheme (approach II) LSTM remained competitive (R = 0.98, RMSE = 3.38, MAE = 2.11); occasional higher training R for XGBoost (up to 0.99) indicates small empirical margins rather than categorical superiority.

-

Modeling trade-off: Approach I (12 inputs) yields marginally better accuracy; approach II (7 inputs) delivers nearly equivalent performance with lower measurement burden and reduced multicollinearity, a practical complexity–interpretability compromise for field application.

-

Explicit Prediction Formulas: MARS and M5P-MT produced closed-form CBR approximations; M5P-MT provided the more accurate, engineering-useful formulae.

-

Key predictors: SHAP analysis consistently identified Ordinary Portland Cement (OPC), Type of Additive (ToA), and Plasticity Index (PI) as the strongest drivers; other AIWs (RHA, CA, GA, QD, SDA, BA) generally increased predicted CBR.

Study limitations

-

Data heterogeneity: variations in curing time, compaction energy, specimen preparation and soaked/unsoaked flags introduce uncertainty and limit transferability.

-

Data scope: 335 records with narrow geographic and lithologic coverage constrain external validity.

-

Distributional issues: zero-inflation and presence/absence (e.g., OPC) distort correlations and interpretation.

-

Edge-case performance: larger errors at CBR ≤ 5% or ≥ 40%, and for extreme PI/atypical gradations due to sparse data and nonlinearities.

-

Model semantics: the dataset is non-temporal; sequence models (LSTM) were therefore used as flexible function approximators rather than as temporal predictors — this should be made explicit when justifying architectural choices.

Future research directions

-

Validate models with independent field and lab datasets with harmonized protocols (curing, compaction, soaked).

-

Incorporate presence/absence indicators, zero-inflated models, heteroscedastic error models or Bayesian approaches to improve calibration and interpretability for sparse stabilizers.

-

Explore hybrid and ensemble MDL architectures and uncertainty quantification methods to enhance robustness and provide actionable prediction intervals.

-

Assess curing effects, long-term durability (wet–dry, freeze–thaw) and life-cycle impacts of AIWs stabilizers.

These adjustments moderate claims, clarify empirical differences among top methods, and outline steps needed to move from accurate predictive models to robust, field-ready tools.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CBR:

-

California bearing ratio

- AIWs:

-

Agricultural and industrial wastes

- ML:

-

Machine learning

- AI:

-

Artificial intelligence

- MDL:

-

Machine and deep learning

- ANN:

-

Artificial neural networks

- MARS:

-

Multivariate adaptive regression splines

- LWP:

-

Locally weighted polynomials

- XGBoost:

-

Extreme gradient boosting

- LSTM:

-

Long short-term memory

- GCV:

-

Generalized cross-validation

- LM:

-

Lagrange multiplier

- BF:

-

Basis function

- SHAP:

-

SHapley additive exPlanation

- RAE:

-

Relative absolute error

- ToA:

-

Type of additives

- SM:

-

Stabilizer materials

- RF:

-

Random forest

- OPC:

-

Ordinary Portland cement

- OMC:

-

Optimum moisture content

- MDD:

-

Maximum dry density

- MAE:

-

Mean absolute error

- RMSE:

-

Root mean square error

- RSD:

-

Ratio of RMSE to standard deviation

- VAF:

-

Variance accounted for

- VIF:

-

Variance inflation factors

- U95:

-

Uncertainty at 95%

- PI:

-

Plasticity index

- PL:

-

Plastic limit

- LL:

-

Liquid limit

- SDA:

-

Saw dust ash

- RHA:

-

Rice husk ash

- BA:

-

Bagasse ash

- CA:

-

Calcium ash

- GA:

-

Granulated ash

- QD:

-

Quarry dust

References

Almuaythir, S., Zaini, M. S. I., Hasan, M. & Hoque, M. I. Stabilization of expansive clay soil using shells based agricultural waste Ash. Sci. Rep. 15, 10186. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94980-5 (2025).

Sahoo, S. & Prasad Singh, S. Strength and durability properties of expansive soil treated with geopolymer and conventional stabilizers. Constr. Build. Mater. 328, 127078. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.127078 (2022).

Tanyildizi, M., GÖKalp, İ., Zeybek, A. & Uz, V. E. Comparative analysis of volume change behavior of expansive road subgrades stabilized with waste paper sludge. Sci. Rep. 14, 28906. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80135-5 (2024).

Paul, S., Sikder, T. & Mim, M. Stabilization of expansive soil through MICP and jute fiber reinforcement: strength and shrink-swell analysis. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 84, 135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10064-025-04159-5 (2025).

Altaf, S., Sharma, A. & Singh, K. A sustainable utilization of waste foundry sand in soil stabilization: a review. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 83, 143. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10064-024-03638-5 (2024).

Joel, M. & Agbede, I. O. Mechanical-Cement stabilization of laterite for use as flexible pavement material. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 23, 146–152. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)MT.1943-5533.0000148 (2011).

Parihar, N. S. & Gupta, A. K. Improvement of engineering properties of expansive soil using liming leather waste Ash. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 80, 2509–2522. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10064-020-02051-y (2021).

Salimi, M., Payan, M., Hosseinpour, I., Arabani, M., Ranjbar, P. Z. Effect of glass fiber (GF) on the mechanical properties and freeze-thaw (F-T) durability of lime-nanoclay (NC)-stabilized marl clayey soil. Construct. Building Materials. 416, 135227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.135227 (2024).

Khajeh, A., Chenari, R. J., Payan, M. A simple review of cemented non-conventional materials: Soil composites. Geotechn. Geological Eng. 38(2), 1019–1040. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10706-019-01090-x (2020).

Payan, M., Sangdeh, M. K., Salimi, M., Ranjbar, P. Z., Arabani, M., Hosseinpour, I. (2024) A comprehensive review on the application of microbially induced calcite precipitation (MICP) technique in soil erosion mitigation as a sustainable and environmentally friendly approach. Results Eng. 24, 103235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rineng.2024.103235

Payan, M., Shafahi, Z., Salimi, M., Hosseinpour, I., Salimzadehshooiili, M. Mechanical properties and microstructure of highly expansive clay treated with waste glass powder (WGP) and waste tire textile fiber (WTTF). Phys. Chem. Earth Parts A/B/C. 140, 104043. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pce.2025.104043 (2025).

Maheepala, M. M. A. L. N., Nasvi, M. C. M., Robert, D. J., Gunasekara, C. & Kurukulasuriya, L. C. Mix design development for geopolymer treated expansive subgrades using artificial neural network. Comput. Geotech. 161, 105534. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compgeo.2023.105534 (2023).

Julphunthong, P. et al. Evaluation of calcium carbide residue and fly Ash as sustainable binders for environmentally friendly loess soil stabilization. Sci. Rep. 14, 671. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-51326-x (2024).

Lal Mohammadi, E., Khaksar Najafi, E., Zanganeh Ranjbar, P., Payan, M., Jamshidi Chenari, R., Behzad, Fatahi, B. Recycling industrial alkaline solutions for soil stabilization by low-concentrated fly ash-based alkali cements. Construct. Building Materials. 393, 132083. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.132083 (2023).

Jamaldar, A., Asadi, P., Salimi, M., Payan, M., Ranjbar, P. Z., Arabani, M., Ahmadi, H. Application of natural and synthetic fibers in bio-based earthen composites: A state-of-the-art review. Results Eng. 25, 103732. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rineng.2024.103732 (2025).

Bahmed, I. T., Khatti, J. & Grover, K. S. Hybrid soft computing models for predicting unconfined compressive strength of lime stabilized soil using strength property of Virgin cohesive soil. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 83, 46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10064-023-03537-1 (2024).

Miraki, H. et al. Clayey soil stabilization using alkali-activated volcanic Ash and slag. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 14, 576–591. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrmge.2021.08.012 (2022).

Ahmad, M. et al. Predicting California bearing ratio of HARHA-treated expansive soils using Gaussian process regression. Sci. Rep. 13, 13593. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-40903-1 (2023).

Katte, V. Y., Mfoyet, S. M., Manefouet, B., Wouatong, A. S. L. & Bezeng, L. A. Correlation of California bearing ratio (CBR) value with soil properties of road subgrade soil. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 37, 217–234. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10706-018-0604-x (2019).

Ikeagwuani, C. C. Estimation of modified expansive soil CBR with multivariate adaptive regression splines, random forest and gradient boosting machine. Innovative Infrastructure Solutions. 6, 199. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41062-021-00568-z (2021).

Bardhan, A., Gokceoglu, C., Burman, A., Samui, P. & Asteris, P. G. Efficient computational techniques for predicting the California bearing ratio of soil in soaked conditions. Eng. Geol. 291, 106239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2021.106239 (2021).

Yildirim, B. & Gunaydin, O. Estimation of California bearing ratio by using soft computing systems. Expert Syst. Appl. 38, 6381–6391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2010.12.054 (2011).

Ghorbani, A. & Hasanzadehshooiili, H. Prediction of UCS and CBR of microsilica-lime stabilized sulfate silty sand using ANN and EPR models; application to the deep soil mixing. Soils Found. 58, 34–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sandf.2017.11.002 (2018).

Taskiran, T. Prediction of California bearing ratio (CBR) of fine grained soils by AI methods. Adv. Eng. Softw. 41, 886–892. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.advengsoft.2010.01.003 (2010).

Tenpe, A. R. & Patel, A. Utilization of support vector models and gene expression programming for soil strength modeling. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 45, 4301–4319. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13369-020-04441-6 (2020).

Payan, M., Asadi, P., Jamaldar, A., Salimi, M., Zanganeh, P., Danial, R., Armaghani, J., He, X., Daichao, Sheng, D. Artificial intelligence-based predictive models for shear wave velocity of soils: A comprehensive review. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 17, 111095. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engappai.2025.111095 (2025).

Khodkari, N., Hamidian, P., Khodkari, H., Payan, M., Behnood, A. Predicting the small strain shear modulus of sands and sand-fines binary mixtures using machine learning algorithms. Transport. Geotechnics. 44, 101172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trgeo.2023.101172 (2024).

Ngamkhanong, C., Keawsawasvong, S., Jearsiripongkul, T., Cabangon, L. T., Payan, M., Sangjinda, K., Rungkhun Banyong, R., Thongchom, C. Data-driven prediction of stability of rock tunnel heading: An application of machine learning models. Infrastructures. 7(11), 148. https://doi.org/10.3390/infrastructures7110148 (2022).

Khoshdel Sangdeh, Salimi, M., Hakimi Khansar, H., Dokaneh, M., Zanganeh Ranjbar, P., Payan, M., Arabani, M. Predicting the precipitated calcium carbonate and unconfined compressive strength of bio-mediated sands through robust hybrid optimization algorithms. Transport.Geotechnics. 46, 101235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trgeo.2024.101235 (2024).

Payan, M., Khoshghalb, A., Senetakis, K., Khalili, N. Effect of particle shape and validity of G max models for sand: A critical review and a new expression. Comput. Geotechnics. 72, 28–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compgeo.2015.11.003 (2016).

Bhatt, S., Jain, P. K. & Pradesh, M. Prediction of California bearing ratio of soils using artificial neural network. Am. Int. J. Res. Sci. Technol. Eng. Math. 8, 156–161 (2014).

Erzin, Y. & Turkoz, D. Use of neural networks for the prediction of the CBR value of some Aegean sands. Neural Comput. Appl. 27, 1415–1426. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00521-015-1943-7 (2016).

Suthar, M., Aggarwal, P. & Predicting, C. B. R. Value of stabilized pond Ash with lime and lime sludge using ANN and MR models. Int. J. Geosynthetics Ground Eng. 4, 6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40891-017-0125-3 (2018).

González Farias, I., Araujo, W. & Ruiz, G. Prediction of California bearing ratio from index properties of soils using parametric and Non-parametric models. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 36, 3485–3498. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10706-018-0548-1 (2018).

Fikret Kurnaz, T. & Kaya, Y. Prediction of the California bearing ratio (CBR) of compacted soils by using GMDH-type neural network. Eur. Phys. J. Plus. 134, 326. https://doi.org/10.1140/epjp/i2019-12692-0 (2019).

Alam, S. K., Mondal, A. & Shiuly, A. Prediction of CBR value of fine grained soils of Bengal basin by genetic expression Programming, artificial neural network and krigging method. J. Geol. Soc. India. 95, 190–196. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12594-020-1409-0 (2020).

Md. Rafizul, I. & Animesh Chandra, R. Prediction of California bearing ratio of fine-grained soil stabilized with admixtures using soft computing systems. J. Civil Eng. Sci. Technol. https://doi.org/10.33736/jcest.2035.2020 (2020).

Kumar, S. A., Kumar, J. P. & Rajeev, J. Application of machine learning techniques to predict soaked CBR of remolded soils. IJERT 2, 3019–3024 (2013).

Varghese, V. K., Babu, S. S., Bijukumar, R., Cyrus, S. & Abraham, B. M. Artificial neural networks: A solution to the ambiguity in prediction of engineering properties of Fine-Grained soils. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 31, 1187–1205. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10706-013-9643-5 (2013).