Abstract

Salinity is a major constraint on tomato production, increasingly intensified by climate change. This study aimed to develop superior salt-tolerant tomato cultivars by evaluating genetic variation in salt tolerance, identifying associated single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) markers through genome-wide association studies (GWAS), and applying genomic prediction (GP). A total of 265 tomato accessions from the USDA germplasm collection were evaluated at the seedling stage under controlled greenhouse conditions with saline stress (200 mM NaCl). Nineteen accessions were identified as salt-tolerant, exhibiting a leaf injury score (LIS) ≤ 3.0 (on a 1–7 scale) and less than 40% chlorophyll reduction compared to non-stressed controls. GWAS was conducted using 27,046 SNPs generated via genotyping-by-sequencing (GBS), utilizing five models in GAPIT3 (GLM, MLM, MLMM, FarmCPU, and BLINK), three models in TASSEL 5 (SMR, GLM, and MLM), and three models in rMVP (GLM, MLM, and FarmCPU). Eight SNPs with LOD scores > 5.73 were significantly associated with salt tolerance (RST_C), located on chromosomes 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7. One SNP (SL4.0CH05_60973295) was also associated with LIS. Candidate genes near these loci included Solyc05g051265 (encoding an alpha/beta-hydrolase superfamily protein and calmodulin-binding heat shock protein) on Chr 5, Solyc06g005680 (a homeodomain-like superfamily protein) on Chr 6, and Solyc06g005690 (a tetratricopeptide repeat [TPR]-like superfamily protein) on Chr 6. Genomic prediction models using GWAS-derived SNPs achieved prediction accuracies (r-values) up to 0.38 for salt tolerance in cross-population analyses. These findings provide insights into the genetic architecture of salt tolerance and valuable tools for molecular breeding of salt-tolerant tomato cultivars.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) is a major horticultural crop worldwide, valued not only for its culinary versatility but also for its nutritional content, including carotenoids, flavonoids, vitamins, and tocopherols that contribute to human health1. Consumption of tomato and its products has been associated with reduced risks of cardiovascular disease, respiratory disorders, and degenerative diseases2,3,4. Despite its global importance, tomato production is often constrained by soil salinity, an abiotic stress that impairs plant growth and yield.

Salinity causes osmotic stress and ion toxicity primarily due to excess sodium (Na⁺) and chloride (Cl⁻) ions, which disrupt water uptake, nutrient acquisition, and photosynthetic efficiency5,6,7. Tomato exhibits sensitivity to salt stress throughout its life cycle, with variable responses depending on developmental stage and tissue type8,9,10. At the molecular level, salt tolerance involves complex regulatory networks including calcium signaling, abscisic acid (ABA) pathways, and transcription factors5,11,12. Wild tomato relatives such as S. pimpinellifolium, S. habrochaites, and S. peruvianum serve as reservoirs of alleles conferring abiotic and biotic stress resistance13. While salt tolerance has been extensively studied at later developmental stages, less emphasis has been placed on the seedling stage, which is critical for successful establishment under saline conditions. Traits such as leaf injury score and chlorophyll content are effective early indicators of salt tolerance14,15,16.

Genetic dissection using quantitative trait loci (QTL) mapping has identified multiple loci associated with salt tolerance traits including plant height, ion concentrations, antioxidant activity, and survival across several chromosomes (1, 3, 5, 6, 7, 9, 11, and 12) (Foolad17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,. Notably, a major QTL cluster on chromosome 7 includes sodium transporter genes SlHKT1.1 and SlHKT1.2, with recent studies validating SlHKT1.2’s role in sodium exclusion17,25. Whole-genome resequencing has further refined the mapping of salt tolerance QTLs26. Despite these advances, the practical application of QTLs in marker-assisted selection (MAS) is limited by low resolution, genotype-by-environment interactions, and inadequate validation under field conditions27. The advent of next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies has dramatically increased marker density, enhancing QTL resolution and enabling more precise gene pyramiding28,29. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) offer superior resolution compared to traditional QTL mapping, allowing detection of multiple alleles within diverse populations and improved dissection of complex traits30,31. Recent GWAS in tomato have identified important genes associated with salt tolerance, such as SlHAK20, a potassium transporter involved in root Na⁺/K⁺ homeostasis (Wang et al.32,, and SlHKT1;2, associated with shoot sodium exclusion33. Additional candidates including SlMSRB1 and SlBRL1 have been linked to seedling salt tolerance34,35. High-throughput and accurate phenotyping integrated with GWAS and NGS genotyping is essential for advancing genetic studies of salt tolerance36. Moreover, genomic prediction (GP) methods, which use genome-wide marker information to predict breeding values, have emerged as powerful tools to accelerate breeding for complex traits like salt tolerance37.

Considering the complex genetic architecture of salt tolerance, a combined approach leveraging GWAS and GP is critical for identifying key loci and enhancing breeding efficiency. Therefore, this study aims to (1) evaluate genetic variation for salt tolerance at the seedling stage in a diverse tomato panel, (2) identify associated SNP markers through GWAS, and (3) estimate genomic breeding values using GP models. The outcomes will provide valuable insights to guide the development of salt-tolerant tomato cultivars suited for saline environments.

Materials and methods

Plant material

A total of 265 tomato accessions were obtained from the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Agricultural Research Service (ARS) Germplasm Resources Information Network (GRIN). These accessions represent a diverse genetic pool, originating from 35 different countries. Notably, a significant portion (59.2%, specifically 157 accessions) were originally from the United States, highlighting the domestic diversity in the collection. The remaining accessions were sourced from various other countries, providing a broad spectrum of genetic variation for salt tolerance evaluation (Supplementary Table S1a, b). In all supplementary materials, the letter “S” is used to denote Supplementary Tables and Figures (e.g., Table S1, Fig. S1). The word “Supplementary” appears only once—in the titles of the first Supplementary Table S1 and Supplementary Figure S1—while only the letter “S” is shown thereafter.

Growth conditions and experimental design

The evaluation of tomato accessions was conducted in a greenhouse at the Arkansas Agricultural Research and Extension Center in Fayetteville, AR (Supplementary Fig. S1A). The greenhouse environment was carefully controlled, maintaining a temperature of 21 °C during the day and 18 °C at night, along with a consistent humidity level of 73% throughout the 2023 and 2024 experiments. The experimental design and methodology for screening the tomato accessions closely followed the procedure outlined by Chiwina et al.38 for tomato drought evaluation, with minor modifications as same as our preliminary experiment39.

In this experiment, six seeds from each accession were sown in individual pots, which were then placed in larger trays as previously described39. The pots measured 8.5 cm in height, with a top diameter of 8.5 cm and a base diameter of 5.8 cm. Each tray, measuring 52 cm in length, 26 cm in width, and 6 cm in height, accommodated 12 pots. The pots were filled to a depth of 8 cm with a commercial compost mix (Berger, berger.ca, BM 6). At planting, each pot received 300 mL of water, while 2 L of water was added to each tray. After the initial irrigation, a regular watering schedule was followed, with 180 mL of water applied to each pot every three days for 35 days. Beginning 10 days after seeding, a liquid fertilizer was applied biweekly. The fertilizer used was Miracle-Gro Water-Soluble All-Purpose Plant Food 24-8-16, which contains ammoniacal nitrogen, urea nitrogen, available phosphate, soluble potash, and trace elements including boron, copper, iron, manganese, molybdenum, and zinc.

The experiment followed a completely randomized design (CRD) with three repetitions, arranged in a split-plot layout. Salt treatment served as the main plot and tomato accessions as subplots39,40,41. The study included two treatment groups: a salt-treated group and a non-treated control group. Thinning was performed 15 days after planting to ensure uniformity in plant vigor and height, maintaining three plants per pot per accession. Salt treatment began 35 days after seeding and continued until the most susceptible accessions had completely wilted—typically within 14 days of treatment initiation. Each day during this period, a 200 mM NaCl solution was applied to the salt-treated group. At the start of each treatment day, the saline solution was poured into the trays to saturate the pots, ensuring the solution reached the root zone via capillary action. The plants were exposed to the saline solution for a continuous 6-hour period to simulate prolonged salt stress, mimicking saline field conditions. After 6 h, the solution was drained or flushed out, and the pots were thoroughly rinsed with tap water to remove residual salts. This daily application and rinsing protocol helped to maintain consistent salt stress while preventing salt buildup that could cause severe osmotic or ionic toxicity. Control plants were irrigated normally without any salt treatment. This treatment phase enabled the evaluation of varying levels of salt tolerance among the different tomato accessions.

Measurements

Leaf injury score

The evaluation of salt tolerance in tomato seedlings has been effectively determined using leaf injury scoring (LIS) as a pivotal indicator: A quantitative assessment of damage from salt treatment, reflecting the severity of physiological impact14,39. This method offers an efficient alternative to more resource-intensive techniques, such as measuring the Na+/K + ratio and Cl- content in roots and leaves, especially in scenarios involving extensive accession analysis. The study by Ravelombola et al.41 further corroborates the validity of leaf injury scoring, which utilizes a graded scale ranging from 1 to 7 (1 representing healthy plants, sequentially increasing through signs of leaf chlorosis, extensive chlorosis, complete chlorosis, initial necrosis, widespread necrosis, to 7 indicating entirely deceased plants) (Fig. S1 B). This scale was applied to the point where susceptible specimens exhibited complete mortality. This approach not only streamlines the assessment process but also provides a cost-effective and accessible means for evaluating salt tolerance in tomato seedlings, particularly relevant in large-scale breeding programs.

Leaf chlorophyll measurements

The chlorophyll content in trifoliate leaves was quantified across three distinct regions for every plant in each accession, both under salt treatment and non-salt treatment. This was executed utilizing the SPAD-502 Plus Chlorophyll Meter from Spectrum Technologies, Inc., Plainfield, IL. Separate recordings were made for each region on the leaves. The data gathered were methodically documented and analyzed by five indexes as outlined in previous studies39; Ravelombola et al.41.

-

i.

C_S: leaf chlorophyll content under salt treatment, measured by the SPAD-502 Plus Chlorophyll Meter (Spectrum Technologies, Inc., Plainfield, IL).

-

ii.

C_NS: Leaf chlorophyll content under non-salt treatments.

-

iii.

AD_C: Absolute decrease in leaf chlorophyll content = leaf SPAD chlorophyll under non-salt treatment—leaf SPAD chlorophyll under salt treatment.

-

iv.

II_C: Inhibition index for chlorophyll content (%) = 100 *[(leaf SPAD chlorophyll under non-salt treatment —leaf SPAD chlorophyll under salt)/leaf SPAD chlorophyll under non-salt treatment)], where II_C = 100 * AD_C/C_NS.

-

v.

RST_C: Relative salt tolerance for chlorophyll content (%) = (100 * leaf SPAD chlorophyll under salt treatment/leaf SPAD chlorophyll under non-salt treatment), where RST_C = 100* C_S/C_NS = 100 – II_C.

Seedling height

The seedling height was measured for each accession under both salt-treated and non-salt-treated conditions, 14 days after initiating the salt treatment. Following the methodology of Dong et al.40, measurements were taken from the base of the shoot to the growing point, coinciding with the complete mortality of the susceptible control. Height data were recorded for each plant, and an average was calculated for each pot (Fig. S1 C). This streamlined approach allowed for a clear comparison between plants under salt and non-salt treatments, providing insights into their respective tolerance levels. The following indexes were collected and computed39,41,42.

-

i.

SH_S: Seedling height under salt treatment (cm).

-

ii.

SH_NS: Seedling height under non-salt treatment (cm).

-

iii.

AD_SH: Absolute decrease in seedling height (cm) = Seedling height under non-salt treatment - Seedling height under salt treatment.

-

iv.

II_SH: Inhibition index for seedling height (%) = 100*[(Seedling height under non-salt treatment - Seedling height under salt treatment)/Seedling height under non-salt treatment], where II_SH = 100* AD_SH/SH_NS.

-

v.

RST_SH: Relative salt tolerance for seedling height (%) = 100*(Seedling height under salt treatment/Seedling height under non salt treatment), where RST_SH = 100* SH_S/SH_NS = 100 – II_SH.

Phenotypic data analysis

The statistical model

In the statistical analysis of the experiment, an Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) model was meticulously applied to assess the impact of salt treatment across various accessions. The model is expressed as Yi(j)= µ + Gi + εij, where Yij represents the observed value for the ith tomato accession at the jth replication. This was implemented across a range of accessions (i = 1, 2, 3,…, 71) and replicated thrice (j = 1, 2, 3). In this equation µ denotes the overall population mean, Gi is the effect attributed to the ith accession (considered a fixed effect in this model), and εij signifies the experimental error associated with each observation. This statistical approach allowed for a rigorous evaluation of the genotypic responses to salt treatment, isolating the specific contribution of each accession while accounting for variability across replications.

ANOVA, distribution, descriptive statistics, pearson’s correlation, and broad-sense heritability

Data analysis was conducted using JMP PRO 17 software. This involved an Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) via the General Linear Model (GLM) procedure, and visualization of data distribution using the software’s ‘Distribution’ feature. Descriptive statistics were obtained using the ‘Tabulate’ function, while Pearson’s correlation coefficients and their p-values were calculated through the ‘Multivariate Methods’ option. Cluster analysis was also performed using JMP PRO 17. Additionally, broad-sense heritability (H2) was estimated following43 formula as:

Where σ2G represents the total genetic variance, σ2e is the residual variance, and r is the number of replications. The estimates for σ2G was obtained as [EMS(G) -Var (Residual)]/r, where EMS(G) and Var (Residual) were extracted from the ANOVA table.

The top accession performers across different traits

The 265 tomato accessions were ranked from 1 to 265 for each of the seven traits (LIS, AD_C, II_C, AD_SH, and II_SH), where 1 indicated the highest level of salt tolerance and 265 represented the most vulnerable accession. Since the value of RST is calculated as 100 minus the Inhibition index II value (RST = 100 - II), the ranking order of RST was the same as the ranking order of II. Consequently, RST_SH and RST_C were not explicitly listed.

The principal component analysis and phylogenetic analysis based on phenotypic data

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and dendrogram phylogenetic tree were constructed based on the five-salt tolerance-related traits (LIS, AD_C, II_C, AD_SH, and II_SH) among the 265 tomato accessions, utilizing ‘Multivariate Methods’ and the hierarchical cluster method in JMP Pro 17.

Genotyping

DNA extraction, genotyping by sequencing (GBS) and SNP discovery

DNA was extracted from fresh tomato leaves using the CTAB/SDS method. The extracted genomic DNA was then sequenced using the genotyping-by-sequencing (GBS) approach, following the protocol described by Elshire et al.44 employing pair-end sequencing. The sequencing libraries were processed on an Illumina NovaSeq platform at the University of Wisconsin-Madison Biotechnology Center (UWBC) (https://biotech.wisc.edu/ accessed on 26 May 2025). The obtained short-read sequences were aligned with the tomato genome reference Solanum lycopersicum ITAG_4.0 (https://phytozome-next.jgi.doe.gov/info/Slycopersicum_ITAG4_0 accessed on 26 May 2025). For single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) identification, a pipeline integrating TASSEL-GBS45 and Stacks 2 (https://catchenlab.life.illinois.edu/stacks/ accessed on 26 May 2025; Rochette et al.46, was utilized. This process identified a total of 392,496 SNP markers across 265 tomato accessions that had both phenotypic and genotypic data. These markers were distributed across 12 chromosomes, with the genotypic data provided by the University of Wisconsin Biotechnology Center (UWBC). After filtered, 27,046 SNPs distributed across 12 chromosomes (Fig. S2; Table S1b; https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28945952.v1) were selected and used in this study for genetic diversity analysis and GWAS. SNP markers were selected based on criteria including a minor allele frequency (MAF) of over 2.0%, less than 15% missing alleles, and a heterozygosity rate of 8% or lower.

Principal component analysis and genetic diversity based on genotypic data- SNPs

In this study, 27,046 SNPs were included in the principal component analysis (PCA) and genetic diversity analysis. PCA and genetic diversity were analyzed using GAPIT 347, with PCA components set from 2 to 10 and neighbor-joining (NJ) tree settings from 2 to 10. Phylogenetic trees were constructed using the NJ method in GAPIT 3. Genetic diversity was assessed for all 265 accessions using GAPIT 3. Additionally, genetic diversity for the salt-tolerant accessions was evaluated using MEGA 1148. Phylogenetic trees for these accessions were constructed based on the Maximum Likelihood method, with parameters described by Shi et al.49,50. This dual approach, integrating both phenotypic and genotypic data, enhanced the understanding of the genetic diversity present in the tomato accessions.

Genome-wide association study

GWAS were conducted using five models: the General Linear Model (GLM), Mixed Linear Model (MLM), Multiple Loci Mixed Model (MLMM), Fixed and Random Model Circulating Probability Unification (FarmCPU), and Bayesian-information and Linkage-disequilibrium Iteratively Nested Keyway (BLINK), implemented in R using the Genomic Association and Prediction Integrated Tool version 3 (GAPIT 3)47, https://zzlab.net/GAPIT/index.html; https://github.com/jiabowang/GAPIT3) and three models: GLM, MLM, and FarmCPU in rMVP51; https://github.com/xiaolei-lab/rMVP).

The analysis was performed on a panel of 265 accessions using 27,046 SNPs. Multiple models were employed to identify robust and consistent SNP markers associated with salt tolerance in tomato. The significance threshold for marker-trait associations was determined using the Bonferroni correction at α = 0.05, resulting in a LOD score threshold of 5.73 based on the total of 27,046 SNPs [(-log(0.05/27046)] used in the analysis52. Additionally, a t-test results for significant SNPs were obtained using Visual Basic for Applications (VBA) in Microsoft Excel 2016.

Candidate gene prediction

Candidate genes were identified based on peak significant SNPs and their surrounding linkage disequilibrium (LD) regions, defined as 50 kb upstream and downstream of each significant SNP53. Gene annotations within these regions were retrieved from the Solanum lycopersicum ITAG4.0 reference genome assembly (https://data.jgi.doe.gov/refine-download/phytozome?organism=Slycopersicum&expanded=691).

Genomic prediction

Genomic prediction using different randomly selected SNP sets

Prediction accuracy (PA) for RST_C and LIS of salt tolerant traits was assessed using seven genomic prediction (GP) models: Bayes A (BA), Bayes B (BB), Bayesian LASSO (BL), Bayesian Ridge Regression (BRR), Ridge Regression Best Linear Unbiased Prediction (rrBLUP), Random Forest (RF), and Support Vector Machine (SVM), analyzed using the R software environment49,50,54,55. Ten randomly selected SNP sets were evaluated, ranging in size from 8 to 15,000 SNPs. These sets were labeled as r8, r50, r100, r200, r500, r1000, r2000, r5000, r10000, and r15000. Each SNP set was used for GP through cross-population prediction using a 5-fold cross-validation approach, with four folds serving as the training population (TP) and one fold as the validation population (VP). Genomic estimated breeding values (GEBVs) were calculated for each of the ten SNP sets across all seven models. Each model-SNP set combination was run 100 times. Mean correlation coefficients (r-values) and standard errors (SE) were computed. Boxplots illustrating the performance of the GP models across the different SNP sets were generated using the ‘ggplot2’ package in R.

Genomic prediction using GAPIT3 for entire panel

The GAPIT3 software package was also used to estimate GEBVs using two models: genomic best linear unbiased prediction (gBLUP) and GWAS-assisted genome BLUP (GAGBLUP, previously referred to as maBLUP)47; https://zzlab.net/GAPIT/index.html). In this analysis, the entire panel of 265 tomato accessions was used as both TP and testing VP to predict GEBVs for RST_C and LIS of salt tolerant traits.

Genomic prediction using GWAS-derived SNP markers

(3 − 1). GWAS-derived SNP markers from the entire panel and self-prediction.

GWAS was first conducted using four models: MLM, MLMM, FarmCPU, and BLINK. SNP markers significantly associated with either RST_C or LIS of salt tolerant trait were identified from each model using the entire GWAS panel of 265 tomato accessions. Subsequently, GP was performed using these GWAS-derived SNP markers, with the entire panel serving as both TP and VP. The GP procedure followed the same approach described previously for GP using different SNP sets.

(3 − 2) GWAS-derived SNP markers using GAGBLUP in GAPIT3.

GP was performed using the GAGBLUP (BLINK) model—formerly known as MaBLUP—in the GAPIT3 package. The entire panel of 265 accessions was divided into two subsets: 80% as TP (212 accessions) and 20% (53 accessions) as VP. Within the full panel, the phenotypic values for individuals in the VP were set to ‘NA’. The prediction accuracy (r-value) was calculated as the correlation between the estimated GEBVs and the observed phenotypic values in the VP. This process was repeated five times, and the mean r-value was used to evaluate the efficiency of the GP model.

Two types of GP scenarios were tested: (1) Cross-population.prediction: SNP markers from the training set (80%) were used to predict the same training set. (2) Across-population.prediction: GWAS-derived SNP markers from the TP (80%; 212 accessions) were used to predict the VP (20%; 53 accessions).

(3–3) GWAS-derived SNP markers from 80% of the entire panel.

The entire panel of 265 tomato accessions was divided into two subsets: 80% as the TP (212 accessions) and 20% as the VP (53 accessions). GWAS was performed on the TP using the BLINK model in GAPIT3, and SNPs with a LOD score (− log₁₀(P)) > 3.0 were selected for use in GP models. GEBVs were calculated using six GP models: BA, BB, BL, BRR, RF, and SVM. For each GP model, both cross- and across-population predictions were conducted for RST_C of salt tolerant trait using the GWAS-derived SNP markers. Each GP model was run 100 times per replication, and the average correlation coefficient (r-value) between GEBVs and observed phenotypic values was calculated. This process was repeated five times, and the mean r-value across replications was used as the final prediction accuracy. Standard errors (SE) of the r-values were also computed. Two GP scenarios were tested: (1) Across.Prediction: GWAS-derived SNP markers from the TP (80%; 212 accessions) were used to predict the VP (20%; 53 accessions). (2) Cross.Prediction: GWAS-derived SNP markers from the TP were used to predict GEBVs within the same TP itself. Boxplots illustrating the performance of each GP model across the different SNP sets were generated using the ggplot2 package in R.

Results

Evaluation of phenotypic data

Leaf injury score

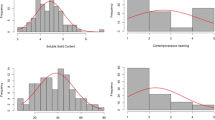

It was identified that leaf injury score (LIS) is among the most accurate parameters for evaluating salt accessions, ranging from 2.1 to 7.0, with an average of 5.7 and a standard deviation of 1.29 (Supplementary Table S2). The distribution of LIS was right-skewed (Fig. 1A; Fig. S3), showed there are more salt susceptible accessions.

Genotypic differences in LIS were evident (F = 9.32, P < 0.0001) (Supplementary Table S3), with lower LIS indicative of greater salt tolerance. The top five accessions, and PI 634,828 (2.4) (Supplementary Table S1), suggesting their salt-tolerant nature based on leaf injury scores. Conversely, the 21 accessions, PI 97,538, PI 647,447, PI 121,662, PI 128,586, PI 158,760, PI 286,426, PI 270,198, PI 647,533, PI 270,239, PI 645,390, PI 538,014, PI 270,236, PI 341,134, PI 270,234, PI 270,228, PI 547,074, PI 270,212, PI 647,518, PI 270,226, PI 647,184, and PI 344,103, exhibited the highest LIS, each with a rating of 7 (Table S1a), indicating their susceptibility to salt stress. The broad-sense heritability for LIS was estimated at 89.3% (Table S3).

Distribution of leaf injury scores (A) and RST_C (B) related to salt tolerance in 265 USDA tomato accessions. The y-axis represents accession density, while the x-axis shows leaf injury score (LIS) (1–9 scale) on the left and RST_C (Relative salt tolerance for chlorophyll content (%) = (100 * leaf SPAD chlorophyll under salt treatment/leaf SPAD chlorophyll under non-salt treatment) on the right.

Leaf chlorophyll measurement

A wide variation in leaf chlorophyll content under salt treatment (SPAD values) (C_S) was observed among the salt-treated plants. Chlorophyll content ranged from 11.2 to 23.7, with a mean of 15.1 and a standard deviation of 2.91 (Table S2). The distribution of chlorophyll content under salt treatment appeared to be right-skewed (Fig. S3). ANOVA revealed significant differences in chlorophyll content for plants subjected to salt treatment (F = 22.98, P-value < 0.0001) (Table S3). The broad-sense heritability for chlorophyll content under salt treatment was estimated at 95.6% (Table S3).

Under non-salt treatments, a range of chlorophyll content (C_NS) was observed, varying between 31.0 and 39.0, with a mean of 34.6 and a standard deviation of 1.37 (Table S2). The distribution of chlorophyll content under non-salt treatments appeared to be approximately normal (Fig. S3). Significant differences in chlorophyll content were found among the 265 tomato accessions (F = 3.17, P-value < 0.0001) (Table S3). The broad-sense heritability for chlorophyll content under non-salt treatments was estimated at 68.5% (Table S3).

The absolute decrease in leaf chlorophyll content (AD_C) was calculated by subtracting the leaf chlorophyll content under salt treatment from that under non-salt treatment. In this study, the absolute decrease in leaf chlorophyll content varied between 8.9 and 25.6 cm, with a mean of 19.5 cm and a standard deviation of 3.03 cm (Table S2). The distribution of absolute decrease values for the 265 tomato accessions appeared to be slightly right-skewed (Fig. S3). Significant differences in the absolute decrease in leaf chlorophyll content were identified among the accessions evaluated for salt tolerance (F = 24.58, P-value < 0.0001) (Table S3). The broad-sense heritability for the absolute decrease in leaf chlorophyll content was estimated at 95.9% (Table S3).

The inhibition index (II_C) represents the percentage by which leaf chlorophyll content was reduced after salt treatment compared to leaf chlorophyll content under non-salt treatment. In this study, the inhibition index for leaf chlorophyll content varied from 27.8 to 67.8, with a mean of 56.3 and a standard deviation of 8.31 (Table S2). The distribution of the inhibition index was right-skewed (Fig. S3). Statistical analysis revealed significant differences in the inhibition index of leaf chlorophyll content among the accessions evaluated for salt tolerance (F = 20.02, P-value < 0.0001) (Table S3). The top five accessions with the lowest inhibition index, including PI601098 (27.8), PI 547,076 (28.9), PI601629 (29.6), PI279815 (30.3), and PI 647,523 (31.1) (Table S1), showed the least effect of salinity, suggesting their salt tolerance. While PI 566,913 (66.8), PI 234,254 (66.9), PI 601,450 (67.5), PI 341,134 (67.7), and PI 196,297 (67.8) showed highest II_S, suggesting their highest salt susceptible (Table S1). The broad-sense heritability for the inhibition index was estimated at 95.5% (Table S3).

Relative salt tolerance for chlorophyll (RST_C) quantifies the relative change in chlorophyll content between salt-treated and non-treated plants, expressed as the ratio between chlorophyll content in plants under salt treatment and those under non-salt treatment. A relative salt tolerance greater than 0.60 for chlorophyll content indicates higher chlorophyll content in salt-treated plants compared to those under normal conditions. In this study, relative salt tolerance for chlorophyll ranged between 32.2 and 72.2, with a mean of 43.7 and a standard deviation of 8.31, indicating a wide range and variability in relative salt tolerance (Table S2). The distribution of chlorophyll content for relative salt tolerance was right-skewed (Fig. 1B). Significant differences in relative salt tolerance for chlorophyll content were observed among the accessions 14 days after the first salt treatment (F = 20.02, P-value < 0.0001) (Table S3). Because RST_C value = 100 – II_C value, the top five highest and lowest salt tolerant are same as those in II_C section. The broad-sense heritability for RST_C was also same as II_C estimated at 95.5% (Table S3).

Seedling height-related parameters

The seedling height for under salt treatment (SH_S) was in the range of 21.2 to 35.7, with a mean of 28.4 cm and a standard deviation of 3.41 cm (Table S2). The seedling height for under salt treatment had a near normal distribution (Fig. S3). ANOVA showed significant differences in seedling height among the tomato accessions under 200 mM NaCl (F = 5.08, P-value < 0.0001) (Table S3). The board-sense heritability for seedling height under salt treatment was 79.3% (Table S3).

For seedlings irrigated with deionized water (under non-salt treatment) (SH_NS), mean seedling height per accession varied from 30.6 to 55.1 cm, with a mean of 41.1 cm and a standard deviation of 4.3 cm (Table S2). Distribution of seedling height under non-salt condition was approximately normal (Fig. S3). ANOVA analysis showed significant differences in seedling height among the 265 tomato accessions under non salt treatment (F = 4.46, P-value < 0.0001) (Table S3). The broad-sense heritability for seedling height under non-salt treatment was 77.6% (Table S3).

The absolute decrease in seedling height (AD_SH) was obtained by subtracting the seedling height under salt treatment from that of under non-salt treatment. In this study, absolute decrease in seedling height ranged between 7.9 and 28.1 cm, with a mean of 12.6 cm and a standard deviation of 3.59 cm (Table S2). Distribution of absolute decrease values for the 265 tomato accessions was right-skewed (Fig. S3). Significant differences in absolute decrease in seedling height were identified among the 265 tomato accessions evaluated for salt tolerance (F = 5.82, P-value 0.0001) (Table S3). The board- sense heritability for absolute height decrease was 82.8% (Table S3).

Inhibition index referred to the percentage (II_SH) by which seedling height was reduced after salt treatment if compared to seedling height under non-salt treatment. In this study, the inhibition index for seedling height varied from 21.5 to 51.3%, with a mean of 30.5% and a standard deviation of 6.65%. The inhibition index was left-skewed distributed (Fig. S3). Statistical analysis revealed significant differences in inhibition index for seedling height among the accessions evaluated for salt treatment (F = 3.35, and P-value < 0.0001) (Table S3). PI 99,782 (46.9), PI 601,177 (47.2), PI 601,119 (47.6), PI 270,206 (51), and PI 270,236 (51.3) (Table S1) had the highest inhibition index, suggesting that these accessions were highly susceptible to salt treatment based on seedling height reduction. Seedling height was least affected by salinity for the accessions. PI 600,919 (21.5%), PI 406,952 (21.5%), PI 452,027 (21.6%), PI 143,524 (21.7%), and PI 309,669 (21.8%) (Table S1), which indicated that these accessions were salt-tolerant. The board-sense heritability for Inhibition index was 70.2% (Table S3).

Relative salt tolerance (RST_SH) was computed such that seedling height under salt treatment was divided by seedling height under non-salt treatment. The higher the relative salt tolerance was, the more likely the accessions were salt-tolerant. Relative salt tolerance ranged between 48.7 and 78.5%, with a mean of 69.5% and a standard deviation of 6.65% (Table S2). Results showed significant differences among accessions in terms of relative salt tolerance for seedling height (F = 3.35, P-value < 0.0001) (Table S3). Relative salt tolerance had a right-skewed distribution (Fig. S3). Because RST_SH value = 100 – II_SH value, the top five highest and lowest salt tolerant are same as those in II_SH section. The broad-sense heritability for RST_SH was also same as II_SH estimated at 70.2% (Table S3).

Pearson’s correlation analysis

A strong positive correlation was demonstrated between the inhibition index for chlorophyll content (II_C) and the absolute decrease in chlorophyll content (AD_C), with an r-value of 0.97 and a p-value of 5.37E-163, suggesting a sustained physiological response to salt stress between the two parameters (Fig. 2, Table S4). Similarly, a significant positive correlation was established between the inhibition index in seedling height (II_SH) and the absolute decrease in seedling height (AD_SH), as indicated by an r-value of 0.92 and a p-value of 7.74E-109 (Fig. 2, Table S4). This significant relationship highlights the predictive power of early seedling height under salt stress conditions. Significant highly positive correlations were revealed between the Leaf Injury Score (LIS) and AD_C (r = 0.81, p = 3.42E-64), and LIS and II_C (r = 0.88, p = 8.17E-89) (Fig. 2, Table S4), indicating shared physiological mechanisms between the parameters.

However, weaker correlations between seedling height and chlorophyll contents were noted. Marginal positive correlations were observed between LIS and AD_SH; LIS and II_SH (r-values of 0.09 and 0.05, respectively); AD_C and AD_SH; AD_C and II_SH (r-values of −0.01 and − 0.06, respectively); and II_C and AD_SH; and II_C and II_SH (r-values of 0.00 and − 0.03, respectively), as shown in Fig. 2 and Table S4. These weaker correlations, coupled with higher p-values, suggest less statistical significance, potentially influenced by extraneous factors, indicating that height is a less reliable predictor of salt tolerance, as showed in Table S4.

The correlation coefficients (r-values) and their corresponding probabilities (P-values) among 11 salt tolerance-related traits in 265 tomato accessions were estimated (Table S4). Notably, high correlations (|r| > 0.55, P < 0.0001), either positive or negative, were evident between.

LIS demonstrated a strong positive correlation with AD_C (r = 0.81, P = 3.42E-64) and II_C (r = 0.88, P = 8.17E-89), while showing a negative correlation with C_S (r = −0.91, P = 1.55E-103) and RST_C (r = −0.88, P = 8.17E-89). Similarly, C_S exhibited high correlations with AD_C (r = −0.89, P = 0.00), II_C (r = −0.97, P = 0.00), and RST_C (r = 0.97, P = 0.00). In addition, strong correlations were observed between AD_C and both II_C (r = 0.97, P = 0.00) and RST_C (r = −0.97, P = 0.00). Among seedling height-related traits, SH_S and SH_NS (r = 0.59, P = 0.00) demonstrated a notable correlation, as did AD_SH with II_SH (r = 0.92, P = 0.00) and RST_SH (r = −0.92, P = 0.00).

Moderately high correlations (|r| > 0.21, P < 0.05) were also observed between SH_NS and either II_SH (r = 0.30, P = 0.00) or RST_SH (r = −0.30, P = 0.00). These correlations suggest a significant degree of association between these pairs of traits. However, weaker correlations (|r| ≤ 0.09, P > 0.20) were found between other trait pairs, such as between C_NS and II_C (r = 0.08, P = 0.205) and SH_S and LIS (r = −0.06, P = 0.372), indicating no significant association between these traits.

Correlation coefficients (r-values) among five salt tolerance-related traits in 265 tomato accessions. The analysis reveals the strength and direction of relationships between traits: LIS, AD_C, II_C, AD_SH, and II_SH. LIS: Leaf Injury Score, Quantitative assessment of damage from salt treatment, reflecting the severity of physiological impact. AD_C: Absolute decrease in leaf chlorophyll content (cm). II_C: Inhibition index for chlorophyll content (%). AD_SH: Absolute decrease in seedling height (cm). II_SH: Inhibition index for seedling height (%).

Principal component analysis and phylogenetic analysis based on phenotypic data

The 265 tomato accessions were classified into three clusters (1, 2, and 3) based on five salt tolerance-related traits (LIS, AD_C, II_C, AD_SH, and II_SH) (Fig. 3 & S4, Table S1). All accessions with highest salt tolerance were placed in cluster 3, indicating similar salt tolerance characteristics. In contrast, clusters 2 and 3 grouped together less tolerant accessions, highlighting their susceptibility to salt stress.

For trait analysis, AD_SH and II_SH were grouped together, while AD_C, II_C, and LIS formed another cluster. Within this cluster, AD_C and II_C were further categorized together, while LIS formed a separate subgroup (Fig. S4). This division suggests a resemblance between leaf injury score (LIS) and leaf chlorophyll content in relation to salt tolerance, differing from the seedling height trait. The biplot (Fig. 3A) illustrated a consistent correlation among AD_C, II_C, and LIS, which merged together, while AD_SH and II_SH were closely associated with each other but distinct from the other three traits. The scree plot (Fig. 3B), PCA plot (Fig. 3C) and constellation plot (Fig. 3D) further supported the presence of three clusters among the 265 tomato accessions based on the five salt-tolerance-related traits.

Principal component analysis (PCA) of 265 tomato accessions performed using JMP Genomics based on five salt tolerance-related traits: LIS, AD_C, II_C, AD_SH, and II_SH. (A) Biplot of the first two principal components, (B) Scree plot showing the variance explained by each component, (C) PCA scatter plot of accessions into three clusters, and (D) Constellation plot illustrating clustering of accessions into three groups.

Genetic diversity and population structure analysis based on genetic data (SNPs)

Using GAPIT 3, the 265 tomato accessions were divided into three distinct clusters (subpopulations), labeled Q1, Q2, and Q3 (Fig. 4). This division was based on several analyses: (1) a 3D graphical plot of the principal component analysis (PCA) (Fig. 4A), (2) a PCA eigen value plot (Fig. 4B), and (3) phylogenetic trees constructed using the neighbor-joining (NJ) method (Fig. 4C, ring, and Fig. 4D, no-root). Additionally, the kinship plot confirmed the presence of these three groups among the 265 accessions (Fig. S5). Each of the 265 accessions was assigned to one of the three clusters (Q1, Q2, or Q3) (Table S1a), and the resulting Q-matrix with three clusters was applied to the GWAS analysis.

The Q1 sub-population, consisting of 246 accessions with 92.8% of the panel, including all tested 227 Solanum lycopersicon accessions plus 12 S. lycopersicum var. lycopersicum, 6 S. lycopersicum var. cerasiforme, and 2 S. subsect. lycopersicon hybr. accessions; the Q2 sub-population, comprising 11 accessions including 2 S. subsect. lycopersicon hybr and 9 all tested S. pimpinellifolium accessions; and the Q3 supopulation consisted of 8 accessions including 5 S. habrochaites, 1 S. pennellii, and 2 S. peruvianum accessions (Table S1, Fig. S6).

Population genetic diversity analysis of the association panel consisting of 265 USDA tomato germplasm accessions. (A) Three-dimensional principal component analysis (PCA) plot illustrating the distribution of genetic variation among accessions. (B) PCA eigenvalue plot generated by GAPIT 3, indicating the proportion of variation explained by each principal component. (C–D) Phylogenetic trees constructed using the neighbor-joining (NJ) method to visualize relationships among accessions, displayed as (C) fan-shaped and (D) unrooted trees, revealing three distinct sub-populations.

Genome-wide association study

Based on the analysis for RST_C of salt tolerance using the five models (GLM, MLM, MLMM, FarmCPU, and BLINK) in GAPIT3, the multiple QQ plot distribution showed significant deviation from the expected distribution, indicating the presence of SNPs associated with RST_C (Fig. 5 right). The symphysic Manhattan plot, covering all tested 27,046 SNPs, revealed several dots (SNPs) with LOD values greater than 5.73, primarily located on Chrs 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7, suggesting the presence of SNPs associated with salt tolerance in the panel (Fig. 5 left). Eight SNPs were observed with LOD values > 5.73 (threshold) in one or more models for RST_C of salt tolerance, distributed across Chrs 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7 (Table 1). Among these 8 SNPs, SL4.0CH01_56850777, located at 56,850,777 bp on chromosome 1, exhibited LOD values > 5.73 in FarmCPU and MLMM in GAPIT3; SL4.0CH03_18798341 and SL4.0CH03_65018441 at 18,798,341 bp and 65,018,441 bp on chromosome 3, respectively, showed LOD values > 5.73 in MLMM and FarmCPU models in GAPIT3, respectively; SL4.0CH04_61946640 located at 61,946,640 bp on chromosome 4, showed LOD values > 5.73 in FarmCPU in GAPIT 3; SL4.0CH05_60973295 at 60,973,295 bp on chromosome 5, showed LOD values > 5.73 in BLINK, GLM and MLM in GAPIT 3; SL4.0CH06_765365 and SL4.0CH06_765393 located at 765,365 bp and 765,393 bp, respectively on chromosome 6, demonstrated LOD values > 5.73 in 2 and 5 models in GAPIT3; SL4.0CH07_62312730 located at 62,312,730 bp on chromosome 7, had LOD values > 5.73 in FarmCPU (Table 1). These results suggests the existence of QTLs in the SNP regions on Chrs 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7 for RST_C of salt tolerance in the panel of 265 tomato accessions.

Notably, SL4.0CH05_60973295 also showed significant association with LIS (leaf injury score), with LOD values > 5.73 in BLINK, FarmCPU, and MLMM, and slightly below the threshold in GLM (5.50) and MLM (5.17) (Table 1; Fig. 6). This SNP was the only one consistently detected across all five GWAS models, indicating a robust QTL on chromosome 5 for salt-induced leaf injury in the tomato panel.

Based on t-tests, the SNP marker, SL4.0CH05_60973295 had LOD = 4.48 for RST_C and 4.65 for LIS, SL4.0CH07_62312730 showed LOD = 4.65 for RST_C, SL4.0CH01_56850777 had LOD = 2.23, indicating the two alleles of these SNP markers had significant different, but other five SNPs had LOD < 2.0, indicating there were no significant differences between their alleles (Table 1; Fig. 7 & S8).

Although eight SNP markers were detected to be associated with RST_C in GAPIT3, the three models, FarmCPU, GLM, and MLM in rMVP did not have LOD > 5.73 except SL4.0CH05_60973295, which had LOD = 6.19 in FarmCPU and GLM models (Table 1, Fig. S7), indicating that this SNP marker had stable association.

The multiple Manhattan plot (left) and Q-Q plot (right) compare the GLM, MLM, MLMM, FarmCPU, and BLINK models in GAPIT3 for the RST_C salt tolerance trait in 265 accessions. In the Manhattan plots, the x-axis represents the 12 tomato chromosomes, and the y-axis shows the LOD scores (− log₁₀(P-value)). In the Q-Q plots, the x-axis indicates the expected LOD scores (− log₁₀(P-value)), while the y-axis represents the observed LOD scores (− log₁₀(P-value)).

The multiple Manhattan plot (left) and Q-Q plot (right) compare the GLM, MLM, MLMM, FarmCPU, and BLINK models in GAPIT3 for leaf injury as a salt tolerance trait in 265 accessions. In the Manhattan plot, the x-axis represents the 12 tomato chromosomes, and the y-axis shows the LOD scores (− log₁₀(P-value)). In the Q-Q plot, the x-axis indicates the expected LOD scores (− log₁₀(P-value)), while the y-axis represents the observed LOD scores (− log₁₀(P-value)).

Candidate genes for salt tolerance

In this study, 11 candidate genes were identified within a 5 kb window flanking eight SNP markers associated with salt tolerance (Table 2).

Chromosome 1: The gene Solyc01g057760, located between 56,844,804 bp and 56,853,371 bp, lies within 3 kb of SNP SL4.0CH01_56850777. It encodes a DEAD-box RNA helicase family protein, also annotated as retrotransposon-related. DEAD-box RNA helicases are involved in diverse cellular processes, including stress responses. In Arabidopsis, the DEAD-box RNA helicase AtRH17 was reported to enhance salt stress tolerance when overexpressed56, suggesting a potential role for Solyc01g057760 in salt tolerance.

Chromosome 3: Solyc03g123870, spanning 65,013,784–65,022,219 bp, overlaps with SNP SL4.0CH03_65018441 and encodes an exocyst complex component 84B expressed protein. However, no literature evidence currently links this gene directly to salt tolerance.

Chromosome 4: Three genes—Solyc04g079530, Solyc04g079540, and Solyc04g079550—are located near SNP SL4.0CH04_61946640, at distances of < 2 kb, 0 kb, and < 3 kb, respectively.

Solyc04g079530 (61,942,086–61,944,699 bp) encodes a peptide transporter PTR2. In Oryza sativa, PTR2 genes have been implicated in salt stress responses57, suggesting a possible role for Solyc04g079530 in tomato salt tolerance.

Chromosome 5: The gene Solyc05g051280, located between 60,968,691 and 60,975,256 bp on chromosome 5, overlaps with the SNP SL4.0CH05_60973295 and encodes an alpha/beta-hydrolase superfamily protein that also contains calmodulin-binding and heat shock protein (HSP) domains. While no direct evidence currently links this gene to salt stress responses in tomato, its domain composition suggests potential involvement in abiotic stress signaling mechanisms. (i) Alpha/beta-hydrolases are involved in a variety of metabolic and signaling processes, including hormone regulation. In rice, an α/β-hydrolase family member was shown to negatively regulate salt tolerance, likely through interactions with the abscisic acid (ABA) signaling pathway58. (ii) Calmodulin-binding proteins play key roles in calcium signaling, a critical component of the plant response to salt stress. For instance, overexpression of GmCaM4 in soybean enhanced salt tolerance by activating stress-responsive genes59, while silencing HvCaM1 in barley led to improved salt tolerance through reduced sodium accumulation and enhanced reactive oxygen species (ROS) scavenging60. (iii) Heat shock proteins (HSPs), although traditionally associated with heat stress, also contribute to salt stress responses. In tomato, overexpression of an endoplasmic reticulum-localized small HSP improved salt tolerance by promoting root vigor and limiting Na⁺ accumulation61. Conversely, overexpression of ClHSP22.8 from watermelon in Arabidopsis decreased salt tolerance, indicating that some HSPs may act as negative regulators under salt stress conditions62. Given these domain-specific associations with stress response pathways, Solyc05g051280 may function in salt tolerance through regulation of hormone signaling, calcium-mediated pathways, and protein stabilization processes, although further functional validation is necessary.

Chromosome 6: Two genes—Solyc06g005680 and Solyc06g005690—are located near SNPs SL4.0CH06_765365 and SL4.0CH06_765393, respectively (within 4 kb). (i) Solyc06g005680 (763,142–764,228 bp): Encodes a homeodomain-like/MYB transcription factor. MYB proteins (e.g., MYB20, MYB42, MYB74) are key regulators of salt stress responses, mediating ABA signaling, SOS pathway activation, and proline biosynthesis. Overexpression of TtMYB1 from Tritipyrum has been shown to enhance salt tolerance in wheat63. (ii) Solyc06g005690 (768,728–770,467 bp): Encodes a TPR-like/PPR protein. TPR and PPR domains are often involved in protein-protein interactions and organelle RNA metabolism. In Arabidopsis, mutation of TTL1, a TPR-containing gene, reduces salt and osmotic stress tolerance by affecting root development and ABA sensitivity64.

Chromosome 7: Solyc07g053980 (62,309,298–62,318,227 bp), located near a salt tolerance-associated SNP, encodes a glucan synthase-like protein (GSL5/1,3-β-glucan synthase component). While this gene’s function is related to cell wall biosynthesis, no direct evidence currently links it to salt stress tolerance.

Genomic prediction of RST_C of salt tolerance

Genomic prediction using different randomly selected SNP sets

Prediction accuracy (PA), measured as the correlation coefficient (r-value), for RST_C and LIS of salt tolerance was evaluated using ten different randomly selected SNP sets ranging from 8 to 15,000 SNPs (labeled r8 to r15000). GP was performed using a cross-population approach with a 5-fold cross-validation scheme across seven GP models: BA, BB, BL, BRR, rrBLUP, RF and SVM (Table S5; Fig. 8).

Across all models, r-values generally increased with the number of SNPs used. The average r-values were less than 0.01 when r200 or less SNPs were used, and r-value was less than 0.22 when r500 or more SNPs, even 15,000 SNPs were used, showed the overall PA remained low for GP of salt tolerance (Table S5; Fig. 8). Among the models, SVM showed lowest r-value for GP of RST_C and rrBLUP showed lowest r-value for LIS with not exceeding 0.07 each, even 15,000 SNPs were used (Table S5, Fig. 8). These results showed that it will be not highly effective to select salt tolerant traits through GS by randomly selected SNP sets.

Prediction accuracy (PA) for RST_C (A) and LIS (leaf injury, B) of salt tolerance using 10 different SNP sets, ranging from 8 to 15,000 randomly selected SNPs (r8 to r15000), evaluated using genomic prediction (GP) models by cross-population prediction was performed with a 5-fold cross-validation scheme, where four subsets served as the training population and one subset as the validation population. PA is represented as the correlation coefficient (r-value) between predicted genomic estimated breeding values (GEBVs) and observed phenotypic values across seven GP models: Bayes A (BA), Bayes B (BB), Bayesian LASSO (BL), Bayesian Ridge Regression (BRR), ridge regression BLUP (rrBLUP), Random Forest (RF), and Support Vector Machine (SVM).

Genomic prediction using GAPIT3 for entire panel

GP was performed using the GAPIT3 software package with two models: genomic best linear unbiased prediction (gBLUP) using 27,046 SNPs and GWAS-assisted genome BLUP (GAGBLUP, aBLUP) using associated SNP markers. The entire panel of 265 tomato accessions was used simultaneously as both the training and validation population. The GAGBLUP (aBLUP) and gBLUP models achieved r-values of 0.52 and 0.82 for RST_C, respectively; 0.31 and 0.91 for LIS (leaf injury), respectively (Fig. 9), indicating moderate to high prediction accuracy. These results demonstrate the potential of GS to effectively identify tomato accessions with high levels of salt tolerance in tomato breeding.

Prediction accuracy (PA) for RST_C and leaf injury using two genomic prediction (GP) models—gBLUP and GWAS-assisted GBLUP (GAGBLUP, aBLUP)—implemented in GAPIT3. The entire panel of 265 tomato accessions was used as both the training and validation set. PA is represented by the correlation coefficient (r-value) between genomic estimated breeding values (GEBVs) and observed phenotypic values.

GP by GWAS-derived SNP markers

(3 − 1) GWAS-derived SNP markers from entire panel and self-prediction

GWAS was conducted on the entire panel of 265 tomato accessions to identify SNP markers significantly associated with RST_C of salt tolerance. The same panel was then used as both the training population (TP) and validation population (VP) for genomic GP, a process referred to as self-prediction.

Three GWAS-derived SNP marker sets—m3 (3 SNP markers) and m8 (8 SNP markers)—were evaluated. These sets yielded progressively higher prediction accuracies (r-values) of 0.32 and 0.38, respectively for RST_C, 0.32 and 0.34, respectively for LIS, averaged across seven GP models (Fig. 10, Table S5). The increasing r-values confirm their relevance to salt tolerance and the utility of these markers for GS.

Since the SNP markers were identified and tested within the same population, elevated r-values were observed under the self-prediction scenario. However, the prediction accuracy is expected to decline when these marker sets are used in across-population predictions, due to reduced genetic linkage and population structure differences. Subsequent sections will evaluate the performance of these GWAS-derived SNPs in both cross- and across-population prediction contexts.

Genomic prediction accuracy (r-value) for RST_C and LIS (leaf injury) of salt tolerance using two GWAS-derived SNP marker sets; 3 SNP markers (m3) and 8 SNP markers (m8) in 265 tomato accessions. Prediction was performed under a cross-prediction scenario using seven genomic prediction (GP) models: Bayesian A (BA), Bayesian B (BB), Bayesian LASSO (BL), Bayesian Ridge Regression (BRR), Random Forest (RF), ridge regression BLUP (rrBLUP), and Support Vector Machine (SVM).

(3 − 2) GWAS-derived SNP markers using GAGBLUP in GAPIT3

GP was conducted for RST_C and LIS (leaf injury) using the GAGBLUP model—previously referred to as MaBLUP (BLINK)—implemented in GAPIT3 (Fig. 11). Cross-population prediction and across-population prediction yielded r-values of 0.49 and 0.15, respectively for RST_C (Fig. 11A); 0.37 and 0.13 for LIS (leaf injury), respectively (Fig. 11B). The lower r-value of 0.15 or 0.13 in across-population prediction showed a substantial decline in prediction accuracy when SNP markers derived from one population were applied to an independent validation set. These findings suggest that the GAGBLUP approach, using only significant SNP markers, may have limited utility for across-population GP of salt tolerance in tomato.

Genomic prediction accuracy (r-value) for RST_C and leaf injury of salt tolerance using the GAGBLUP (= MaBLUP or BLINK) model in GAPIT3. Two prediction scenarios are shown: (1) Cross-population prediction: SNP markers from the training set were used to predict the same training set (265 accessions). (2) Across-population prediction: SNP markers derived from the training set (80%; 212 accessions, averaged from five GWAS runs) were used to predict the validation set (20%; 53 accessions).

(3–3) GWAS-derived SNP markers from 80% of the entire panel

GP was conducted using SNP markers identified from GWAS on 80% of the whole soybean panel (212 accessions), which served as the TP. These markers were used to predict RST_C of salt tolerance in both the training population (cross-prediction) and the independent 20% validation population (across-prediction).

Across the two prediction scenarios—Across.Prediction and Cross.Prediction—the GWAS-derived SNP markers consistently yielded r-values of ≥ 0.23 in cross-prediction and ≥ 0.28 in across-prediction (Table S6, Fig. 12). These results validate the association between the selected SNP markers and RST_C of salt tolerance and demonstrate the utility of incorporating GWAS-informed markers into GS strategies for improving salt tolerance in tomato breeding programs.

Genomic prediction (GP) accuracy (r-values) for RST_C of salt tolerance using GWAS-derived SNP markers from the training population (80%; 212 accessions). (A) Across Prediction: SNP markers from the training set were used to predict an independent validation set (20%; 53 accessions) (Left). (C) Cross Prediction: SNP markers from the training set were used to predict the same training set (212 accessions) (Right).

Genetic diversity analysis for salt tolerant tomato accessions

The top accession performers across different traits and genetic diversity analysis

To identify superior accessions, the 265 tomato accessions were ranked based on five salt tolerance–related traits: LIS, AD_C, II_C, AD_SH, and II_SH (Table S7). The top 10 accessions ranked by all five traits were: PI 279,815, PI 303,797, PI 542,390, NSL 164,223, PI 365,967, PI 600,921, PI 127,799, PI 109,837, PI 406,952, and PI 212,423.

When focusing on the three most indicative traits—LIS, AD_C, and II_C—the top 10 accessions included: PI 279,815, PI 548,827, PI 303,797, PI 547,076, PI 542,390, NSL 164,223, PI 365,967, PI 645,391, PI 601,098, and PI 601,629. Notably, five accessions—PI 279,815, PI 303,797, PI 542,390, NSL 164,223, and PI 365,967—were consistently ranked in the top 10 across both the five-trait and three-trait evaluations, indicating their strong overall salt tolerance and potential breeding value (Table S7). Each trait exhibited a unique ranking order, reflecting the multifactorial nature of salt tolerance., The five accessions consistently ranked high across multiple traits. PI 279,815 emerged as the most outstanding performer, ranking first based on the average of all five traits and also of the three core traits (LIS, AD_C, and II_C). Specifically, PI 279,815 ranked 4th for LIS, 4th for AD_C, 4th for II_C, 12th for AD_SH, and 7th for II_SH, demonstrating both physiological resilience and growth maintenance under salinity stress. Other accessions such as PI 303,797, PI 542,390, NSL 164,223, and PI 365,967 also showed consistent top-tier performance across multiple traits, making them strong candidates for breeding programs. Conversely, some accessions displayed strong performance in specific traits but weak performance in others, highlighting the complexity of salt stress responses. For example, PI 601,098 ranked 1 st in both AD_C and II_C but was ranked 30th in LIS, and much lower in AD_SH (251st) and II_SH (258th), indicating high photosynthetic tolerance but poor growth under salinity. Similarly, PI 639,215, which ranked 1 st in AD_SH, was ranked much lower in LIS (159), AD_C (163), II_C (229), and II_SH (74), further emphasizing the need for multi-trait evaluation when assessing salt tolerance.

Genetic diversity and population structure among salt-tolerant accessions

The top 19 accessions identified as salt-tolerant were all grouped into Cluster 3 based on phenotypic traits (LIS, AD_C, II_C, AD_SH, and II_SH) (Fig. 3 & S4; Table S1), supporting their consistent physiological performance under salt stress. Among these, 15 accessions were placed in the Q1 genetic subgroup, three in Q2, and one in Q3, based on SNP-derived population structure analysis (Table 3). This suggests that Q1 contains the highest number of salt-tolerant accessions, most of which are Solanum lycopersicum. Among the 15 accessions in Q1, 14 were S. lycopersicum, and one was a S. lycopersicum hybrid. The three Q2 accessions belonged to S. pimpinellifolium. The sole Q3 accession, PI 379,012, was identified as S. habrochaites, suggesting unique genetic divergence from the others.

Phylogenetic relationships among salt-tolerant accessions

Phylogenetic analysis using the Maximum Likelihood method (Fig. 13) revealed that PI 379,012 (S. habrochaites) formed a distinct cluster, clearly separated from the other 18 salt-tolerant accessions. This genetic isolation reflects its wild species origin and divergent evolutionary background. The remaining accessions were grouped into two additional clusters: one consisting of 15 accessions of S. lycopersicum, and another containing three accessions of S. pimpinellifolium.

These results confirm that salt-tolerant accessions are distributed across all three Solanum species, and they possess distinct genetic bases, offering a valuable resource for breeding programs. The genetic and phenotypic consistency of these tolerant accessions makes them ideal candidates for developing improved cultivars through traditional breeding and molecular approaches.

Discussion

Salt tolerance in tomato is a complex trait involving physiological, morphological, and genetic factors. Evaluating multiple traits is critical for accurately assessing salinity tolerance and identifying robust accessions for breeding. In this study, we evaluated 265 tomato accessions using LIS, chlorophyll content, and seedling height parameters, revealing significant genetic variation and heritability.

Leaf injury score

LIS proved to be a reliable indicator of salt stress, consistent with previous studies14,15. The broad phenotypic range (2.1 to 7.0) and high heritability (88.9%) observed in our study are comparable to those reported by Khaliluev et al.65, who found LIS to be a heritable and discriminative trait in evaluating salinity tolerance in tomatoes. Accessions such as PI 548,827, PI 645,391, and PI 647,556 showed low LIS and high tolerance, whereas PI 97,538 and PI 128,586 were highly susceptible (Table S1, S7). These results support the inclusion of LIS in early-stage selection for salt tolerance.

Chlorophyll-related traits

Salt stress is known to impair chlorophyll biosynthesis by disrupting ion homeostasis and increasing oxidative stress66,67. Our findings align with previous reports, where salinity led to significant declines in chlorophyll content (e.g., Amjad et al.68,. The strong genotypic differences and high heritability (95.6% and 95.9%) of chlorophyll content traits (AD_C and II_C) observed in this study (Table S3) are similar to those reported by da Silva Oliveira et al. and Fatima et al.69,70, supporting their reliability as selection indices.

Accessions such as PI 601098, PI 547076, and PI 601629 maintained high chlorophyll content under salt stress (higher RST_C%) and reduced less chlorophyll content comparison with under no salt stress less AD_C value and II_C %) (Table S1, S7), suggesting efficient ion exclusion or antioxidant mechanisms. This is in agreement with studies by Gong et al.71, which demonstrated that higher chlorophyll content is linked to reduced oxidative damage and better salt stress resilience.

Seedling height under salt stress

The variation in seedling height under stress conditions reflects differences in osmotic adjustment and ion regulation, similar to findings in tomato by Alam et al.72,73. Our data revealed high heritability for seedling height traits under salinity (82.8% for AD_SH, and 70.2% for II_SH) (Table S3), indicating strong genetic control, consistent with Wang et al.32, who identified key Na⁺/K⁺ transporter genes influencing salt tolerance. While some accessions such as PI 600,919 and PI 406,952 showed strong height maintenance, others were more adversely affected (Table S1 & S7). These differences underscore the importance of including height-related traits in screening protocols, despite their lower correlation with chlorophyll parameters.

Trait correlation and multivariate analysis

Correlation analysis revealed strong positive relationships among LIS, AD_C, and II_C (r > 0.8), AD_SH and II_SH (r = 0.92) (Fig. 2, Table S4), while seedling height traits showed weaker correlations with chlorophyll content, suggesting independent physiological pathways. Similar trait clustering was reported in previous PCA studies by Ali et al.73 and Kashyap et al.74, confirming that different genetic mechanisms govern leaf-level and shoot-level responses to salinity.

Genetic structure and diversity based on phenotypic data

The classification of 265 tomato accessions into three distinct phenotypic clusters (Clusters 1, 2, and 3) revealed substantial genetic variation associated with salt tolerance, particularly within Cluster 3 (Fig. 3 & S4). Five accessions—PI 279,815, PI 303,797, PI 542,390, NSL 164,223, and PI 365,967 (Table S1 & S7)—grouped within Cluster 3 exhibited superior salt tolerance, as indicated by their consistently favorable performance across multiple phenotypic traits.

The genetic diversity observed among the clusters, especially the higher susceptibility to salt stress in Clusters 1 and 2 (Fig. 3 & S4), underscores the complex nature of salt tolerance mechanisms in tomato. This variation highlights the need to dissect the underlying hormonal and signaling pathways involved in stress response, as emphasized by Kashyap et al.74. Such insights are valuable for breeding programs aiming to enhance salt tolerance by integrating diverse and complementary genetic mechanisms.

Trait-based analysis revealed a clear distinction between leaf-related traits—leaf injury score (LIS) and chlorophyll content (AD_C and II_C)—and seedling height traits (AD_SH and II_SH) (Fig. S4), suggesting that these traits are governed by different genetic factors. This separation is consistent with the findings of Ali et al.73, who reported that targeted trait selection can significantly enhance salt tolerance in tomato introgression lines. The differentiation between leaf-based and growth-based traits points to the potential for precise, trait-specific selection strategies in breeding programs.

The PCA biplot further supports these findings by showing strong correlations among LIS, AD_C, and II_C, while AD_SH and II_SH formed a separate cluster (Fig. 3). Notably, the accessions grouped in Cluster 3—PI 279,815, PI 303,797, PI 542,390, NSL 164,223, and PI 365,967 (Table S1 & S7)—consistently demonstrated superior salt tolerance across multiple traits, indicating shared adaptive mechanisms. These results mirror previous studies by Ali et al. and Kashyap et al.73,74, which found that salt-tolerant lines often clustered based on both phenotypic performance and genetic distance.

Moreover, the separation of leaf-related traits (LIS, AD_C, II_C) from growth-related traits (AD_SH, II_SH) observed in the PCA (Fig. S4) supports the hypothesis that distinct physiological responses contribute to salt stress adaptation. This is consistent with conclusions drawn by Fatima et al. and Loudari et al.66,70, who reported that different trait categories may reflect separate genetic and physiological pathways in response to salinity stress.

Overall, these clustering patterns underscore the importance of trait-specific selection strategies and suggest potential for identifying unique QTLs or candidate genes associated with specific aspects of salt tolerance. The phenotypic and genetic homogeneity observed among the most salt-tolerant accessions in Cluster 3 provides a strong foundation for future breeding strategies aimed at developing salt-resilient tomato cultivars—an increasingly important goal in light of rising soil salinity driven by climate change and environmental degradation.

Genetic diversity, principal component analysis, and GWAS findings

The classification of 265 tomato accessions into three genetic clusters (I, II, and III) based on principal component analysis (PCA), phylogenetic analysis, and kinship matrices revealed a well-structured and diverse population. This genetic structure aligns with known species taxonomy—S. lycopersicum (Cluster I/Q1), S. pimpinellifolium (Cluster II/Q2), and wild species such as S. habrochaites and S. pennellii (Cluster III/Q3) (Table S1 & S7; Fig. S6)—and is consistent with prior studies highlighting domestication divergence and reproductive isolation barriers20; Asins et al.17,75,76,.

Population structure analysis using GAPIT3 further confirmed the presence of three subpopulations (Q1–Q3) (Fig. 4, S5 & S6). Q1 included the majority of S. lycopersicum accessions (92.8%) (Table S1), while Q2 and Q3 encompassed broader diversity contributed by wild relatives. This wide genetic representation supports the robustness of this panel for GWAS and allele mining for complex traits such as salt tolerance. Accounting for population structure in GWAS analysis was critical to reduce false positives and enhance the resolution of marker-trait associations.

GWAS identified eight SNP markers significantly associated with salt tolerance traits. Among them, SL4.0CH05_60973295 on chromosome 5 emerged as a key locus, consistently detected across multiple statistical models (GLM, MLM, MLMM, FarmCPU, BLINK) and platforms (GAPIT3 and rMVP) (Table 1). This SNP was significantly associated with both relative salt tolerance for chlorophyll content (RST_C) and leaf injury score (LIS), suggesting potential pleiotropic effects. This locus coincides with qST5, as reported by Li et al.26, and overlaps with genomic regions previously linked to salt stress tolerance by Foolad20 and Villalta et al.24, reinforcing its functional relevance.

Other significant SNPs, such as SL4.0CH03_65018441 and SL4.0CH07_62312730, were located near previously reported QTLs qST3 and qST7 on chromosomes 3 and 7, respectively26. Notably, SL4.0CH07_62312730 is positioned near SlHKT1.2, a well-characterized sodium transporter gene17, providing strong biological support for its involvement in salt stress response. The convergence of GWAS signals with known QTLs highlights these regions as core genetic determinants of salt tolerance.

However, some SNP associations were not consistently detected across all GWAS models, reflecting the polygenic nature of salt tolerance and its sensitivity to environmental conditions. This underscores the need for integrating multiple GWAS models and leveraging existing QTL knowledge to identify robust and stable genetic markers27,30.

Genomic prediction

Genomic prediction (GP) is a powerful tool for accelerating genetic gain in plant breeding, especially for complex traits such as salt tolerance that are influenced by numerous small-effect loci and gene–environment interactions. In this study, we evaluated the prediction accuracy (PA) of two salt stress-related traits—relative salt tolerance for chlorophyll (RST_C) and leaf injury score (LIS)—using multiple GP strategies.

When using randomly selected SNP subsets ranging from 8 to 15,000 markers across seven models, prediction accuracy was generally low, with correlation coefficients (r-values) rarely exceeding 0.22. Models such as rrBLUP and SVM consistently showed the lowest accuracies (r < 0.07) (Fig. 8; Table S5). These results are consistent with findings in crops such as cowpea, rice, and maize, where randomly chosen markers without biological relevance often fail to capture the genetic variance of complex traits6,54,77. In contrast, whole-genome GP using all 27,046 SNPs and the full panel of 265 accessions significantly improved model performance. The gBLUP model achieved high r-values of 0.82 for RST_C and 0.91 for LIS, while the GAGBLUP (aBLUP) model using only associated SNPs also performed moderately well (r = 0.52 for RST_C and r = 0.31 for LIS) (Fig. 9). These elevated values reflect both the effectiveness of the models and the use of the same dataset for training and validation (self-prediction), which tends to overestimate accuracy but serves as a useful performance benchmark37.

Prediction accuracy was further enhanced by using GWAS-derived SNP subsets (e.g., m3 and m8), which are biologically informed. These subsets yielded self-prediction accuracies up to r = 0.38 for RST_C and r = 0.34 for LIS (Fig. 10; Table S5), demonstrating that trait-associated markers can improve model performance while reducing dimensionality. Similar improvements have been observed in other crops where GWAS-informed GP models outperform those using random markers49,50,55,78,79.

However, prediction accuracy declined substantially in across-population scenarios. For example, the GAGBLUP model’s accuracy dropped from 0.49 to 0.15 for RST_C and from 0.37 to 0.13 for LIS (Fig. 11), highlighting the reduced transferability of marker effects across genetically divergent subpopulations55,79,80. To assess model robustness, we performed cross- and across-population predictions using SNPs derived from 80% of the panel to predict the remaining 20%. Across five GP models (BA, BB, BL, BRR, RF) and using GWAS-based SNPs from the BLINK model, we observed moderate average accuracies of ≥ 0.33 (cross-population) and ≥ 0.26 (across-population) (Fig. 12; Table S6). These results underscore the value of biologically relevant SNPs in maintaining predictive power even when extrapolating to new genetic backgrounds.

We acknowledge several limitations in our GP analysis. While the self-prediction accuracies were relatively high, the markedly lower accuracies observed in cross- and across-population predictions can be attributed to several factors. These include the limited size of the training population, genetic heterogeneity between training and testing sets, underlying population structure, and potential SNP-by-environment interactions. These limitations underscore the challenges associated with model transferability and highlight the importance of designing training populations that are both genetically representative and sufficiently large. Furthermore, our findings emphasize that, for GP to be effectively implemented in practical breeding programs, particular attention must be given to optimizing training population composition and managing the effects of genetic and environmental diversity.

In conclusion, our results demonstrate that random marker-based GP models are insufficient for reliably predicting salt tolerance. However, models leveraging GWAS-informed SNPs and whole-genome data can significantly enhance predictive accuracy, particularly within structured populations. For breeding applications, integrating informative markers with optimized training sets can maximize genetic gain. Together with the identified loci and superior accessions, these findings provide a robust foundation for implementing marker-assisted selection (MAS) and genomic selection (GS) strategies aimed at developing salt-tolerant tomato cultivars. Future efforts should focus on fine-mapping these candidate regions and functionally validating nearby genes to translate genomic insights into practical breeding outcomes.

Conclusion

This study revealed substantial genetic variation in salt tolerance among diverse USDA tomato accessions and identified key SNP markers and candidate genes associated with stress-response traits through comprehensive genome-wide association studies (GWAS). Several significant loci, particularly those located on chromosomes 5 and 6, were linked to traits such as leaf injury score and relative chlorophyll content, and were associated with genes involved in stress signaling, ion transport, and cellular protection. Genomic prediction (GP) models using GWAS-derived SNPs demonstrated moderate accuracy, underscoring their potential for integration into breeding pipelines. These results collectively highlight the feasibility of employing marker-assisted selection (MAS) and genomic selection (GS) to accelerate the development of salt-tolerant tomato cultivars. Altogether, the findings provide critical genetic resources and tools for molecular breeding aimed at improving tomato resilience to salinity stress, contributing to sustainable crop production in the face of increasing soil salinization and climate change challenges.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the Supplementary Materials. The SNP data are available in [https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28945952.v1](https:/doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28945952.v1), accessed on 30 May 2025.

References

Tommonaro, G. et al. Evaluation of antioxidant properties, total phenolic content, and biological activities of new tomato hybrids of industrial interest. J. Med. Food. 15 (5), 483–489. https://doi.org/10.1089/jmf.2011.0118 (2012).

Agarwal, S. & Rao, A. V. Tomato lycopene and its role in human health and chronic diseases. CMAJ 163, 6 (2000).

Sesso, H. D., Buring, J. E., Norkus, E. P. & Gaziano, J. M. Plasma lycopene, other carotenoids, and retinol and the risk of cardiovascular disease in women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 79, 47. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/79.1.47 (2004).

Tan, H. L. et al. Tomato-based food products for prostate cancer prevention: what have we learned? Cancer Metastasis Rev. 29 (3), 553–568. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10555-010-9246-z (2010).

Yang, R. et al. Hormone profiling and transcription analysis reveal a major role of ABA in tomato salt tolerance. Plant. Physiol. Biochem. 77, 102–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plaphy.2014.01.015 (2014).

Zhang, P., Senge, M. & Dai, Y. Effects of salinity stress at different growth stages on tomato growth, yield, and water-use efficiency. Commun. Soil. Sci. Plant. Anal. 48 (6), 624–634. https://doi.org/10.1080/00103624.2016.1269803 (2017b).

Zörb, C., Geilfus, C. M. & Dietz, K. J. Salinity and crop Yeld. Plant. Biol. 21 (Suppl 1), 31–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/plb.12884 (2019).

de la Peña, R. & Hughes, J. Improving vegetable productivity in a variable and changing climate. SAT eJournal. 4, 1 (2007).

Leogrande, R., Lopedota, O., Montemurro, F., Vitti, C. & Ventrella, D. Effects of irrigation regime and salinity on soil characteristics and yield of tomato. Ital. J. Agron. 7, 1. https://doi.org/10.4081/ija.2012.e8 (2012).

Lunin, J., Gallatin, M. H. & Batchelder, A. R. Saline irrigation of several vegetable crops at various growth stages. I. Effect on yields. Agron. J. 55, 107–109. https://doi.org/10.2134/agronj1963.00021962005500020004x (1963).

León, J., Rojo, E. & Sánchez-Serrano, J. J. Wound signalling in plants. J. Exp. Bot. 52, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/52.354.1 (2001).

Xiong, L., Schumaker, K. S. & Zhu, J. K. Cell signaling during cold, drought, and salt stress. Plant. Cell. 14 (Suppl), S165–S183. https://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.000596 (2002).

Cuartero, J. & Fernández-Muñoz, R. Tomato and salinity. Sci. Hortic. 78, 83–125 (1998).