Abstract

Although the relatively unchanging consequences of age and genetic factors significantly contribute to the development and progression of Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (BPH), numerous modifiable factors play a role in preventing progression or alleviating symptoms. Identifying predictors of symptom severity and objective biomarkers is beneficial for effective management. This study aimed to determine the predictors of BPH symptom severity and assess the predictive performance of hematologically derived inflammatory markers in patients attending Dessie Comprehensive Specialized Hospital in Ethiopia. A cross-sectional study was conducted from August to October 2024. Data was collected through face-to-face interviews performed by well-trained health professionals using the KoboCollect application. STATA version 17 was utilized for statistical data analysis. Bivariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses were employed to identify predictors of BPH severity, with a p-value of < 0.05 considered statistically significant in the multivariable logistic regression. The predictive performance of immune-inflammatory index levels for the severity of BPH was evaluated using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis, and pairwise comparisons of Area Under the Curve (AUC) were conducted using DeLong’s test. Ethical clearance was obtained from the Ethics Review Committee of Wollo University. A total of 232 BPH patients were included in this study, of whom 84 (36.21%) presented with severe symptoms. Age ≥ 65 years (AOR = 2.55, 95% CI: 1.19, 5.45), low physical activity (AOR = 2.56, 95% CI: 1.22–5.35), central obesity (AOR = 2.79, 95% CI: 1.07–7.25), and elevated immune-inflammatory markers [SII > 564.92 × 10³ (AOR = 2.97, 95% CI: 1.10–7.98), PII > 273.3 × 10⁶ (AOR = 2.46, 95% CI: 1.04–5.86), and NLR ≥ 1.368 (AOR = 2.87, 95% CI: 1.01–8.14)] were significantly associated with severe BPH symptoms (p-value < 0.05). In ROC analysis, SII exhibited the highest predictive performance for severe symptoms with an AUC of 0.736 (95% CI: 0.67, 0.801); optimal cut-off: 564.92 × 10³; specificity − 72%, sensitivity − 69%; PII demonstrated similar performance with an AUC of 0.729 (95% CI: 0.66, 0.796); optimal cut-off: 273.3 × 10⁶; specificity and sensitivity of 69%. Although it was not significantly associated with severe BPH, PLR also demonstrated moderate predictive performance (AUC = 0.67, specificity 66%, sensitivity 68%), while LMR exhibited poor predictive ability (AUC = 0.403; 95% CI: 0.328, 0.477). Pairwise DeLong’s tests confirmed that SII had significantly higher accuracy than NLR (p-value = 0.0003) and PLR (p-value 0.044), but not PII (p-value = 0.769). The LOESS curve further revealed a non-linear, monotonically positive association between SII and the probability of severe BPH, with a marked rise in risk at higher SII levels. Advanced age, adverse lifestyle factors, and elevated systemic inflammatory markers (SII, PII, NLR) were significant predictors of BPH severity. SII and PII, derived from routine blood tests, showed moderate predictive value for identifying patients with severe BPH, with SII showing superior discriminative accuracy, and may serve as accessible, non-invasive adjunct biomarkers. LMR was not identified as a useful predictor in this context. These findings highlighted the role of inflammation in BPH severity and suggest markers for clinical assessment. Further studies are recommended to validate these findings and explore their implications in therapeutic decision-making.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) is an enlargement of the prostate gland from the progressive hyperplasia of stromal and glandular prostatic cells1,2. It is a histologic diagnosis, and the proliferation is in smooth muscle and epithelial cells, more within the transition zone3. The prostatic transition zone comprises approximately 5% of the prostate and surrounds the proximal urethra. This zone is the site of continual growth throughout life4. Even though there are differences in the reported prevalence of BPH among countries, it has been stated that more than 20% of men between the ages of 30 and 79 years, equivalent to 15 million, and approximately 80% of men by 70 years of age would be estimated to have the problem5.

The disease is clinically manifested in the form of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) associated with benign prostatic enlargement6. The LUTS encompass a range of symptoms, broadly categorized into bladder storage issues like urinary frequency, urgency7, and voiding difficulties such as dysuria, hesitancy, intermittent stream, poor flow, post-micturition dribbling, and incomplete voiding5,7. Although prostatic tissue proliferation is classified as benign and may not be life-threatening, if left untreated, it can lead to LUTS and significantly decrease the quality of life of those affected8,9, as well as an increased risk of acute urinary retention9. The number of men diagnosed with BPH and LUTS has steadily increased over the last decade, driven by longer life expectancies, greater disease awareness, and improved diagnoses7,9. The prevalence of LUTS associated with BPH parallels that of pathologic BPH; more than 50% of men over 50 are believed to experience LUTS secondary to an enlarged prostate gland10.

While age and genetics are well-established risk factors, recent studies highlight the crucial role of modifiable lifestyle and metabolic factors in the progression of LUTS in BPH patients. Obesity has been strongly linked to BPH-related LUTS, with higher body mass index (BMI) correlating with greater prostate volume and more severe urinary symptoms11,12. Behavioral factors like physical inactivity, smoking also contribute significantly, as sedentary individuals and smokers show a higher prevalence of LUTS13,14, and poor dietary habits, particularly inadequate fruit and vegetable intake, increase LUTS risk15. Metabolic disorders, particularly diabetes mellitus, have been implicated in the pathophysiology of LUTS, with diabetic individuals being at significantly higher risk of developing severe symptoms.

In addition, chronic inflammation has been implicated in the pathogenesis and symptom progression of BPH, as inflammatory processes within the prostate foster tissue remodeling, stromal expansion, and symptom development16. The presence of inflammatory infiltrates in prostate tissue has been associated with an increased risk of acute urinary retention and worsening LUTS17. Furthermore, a number of hematological-derived biomarkers that are indicative of systemic immune-inflammatory responses have been confirmed in recent decades for their correlation with the diagnosis and progression of BPH. Markers such as the platelet-lymphocyte ratio (PLR), neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), and systemic immune-inflammation index (SII) have been evaluated for their diagnostic and prognostic use for BPH18,19. Additionally, these inflammatory markers have demonstrated powerful diagnostic and prognostic value in various metabolic risks related to BPH and various tumors, including prostate cancer20,21. Elevated levels of these markers correlate with increased disease severity, poorer treatment response, and a higher likelihood of requiring invasive intervention22,23. Specifically, higher SII values have been associated with the progression of LUTS in men with BPH19.

However, the value of those hematological-derived inflammatory markers in predicting symptom severity of BPH remains obscure. On top of that, controversial results have been conveyed in several studies regarding other predictors of severe BPH24,25,26. For example, some studies26,27 found a lower prevalence of severe BPH among alcohol consumers, while other studies28 reported a positive correlation. Similar contradictions exist for smoking and physical activity, with some studies26,28 finding no association, while others suggest smokers and ex-smokers face a higher BPH risk. Likewise, while some studies26,27 have shown no relationship between dyslipidemia, diabetes, and BPH; others29,30,31 have found strong links. Most importantly, to the best of our knowledge, no documented study has assessed the severity of BPH symptoms in Ethiopia, particularly in the study area. Therefore, this study aimed to identify predictors of symptom severity and evaluate the predictive performance of immune-inflammation indices in BPH patients at Dessie Comprehensive Specialized Hospital. This would aid in implementing appropriate interventions or targeted approaches. Since most risk factors are modifiable, prevention and control strategies would be proposed to alleviate symptoms, prevent disease progression, and preserve quality of life. Furthermore, this study will encourage additional research into biomarkers that could help stratify patients based on their risk of developing severe symptoms of BPH.

Methods and materials

Study setting and period

The study was conducted at Dessie Comprehensive Specialized Hospital in Northeast Ethiopia from August to October 2024. The hospital is situated in Dessie town, part of the Amhara Regional State, which is 401 km northeast of the capital, Addis Ababa. It serves as a referral center for South Wollo and surrounding zones, catering to approximately 7 million people, including those from neighboring regions. The hospital includes units such as internal medicine, surgery, gynecology and obstetrics, pediatrics, oncology, psychiatry, laboratory, orthopedics, pharmacy, and neurology. The surgery unit has both inpatient and outpatient services, catering to new patients as well as follow-up cases. According to hospital data, an average of 170 to 200 patients with BPH visited the hospital per month between February and June 2024. A hospital-based cross-sectional study took place from August to October 2024.

Study population and eligibility criteria

The study targeted BPH patients attending Dessie Comprehensive Specialized Hospital. The source population comprised all BPH patients visiting the hospital, while the study population included those who attended during the data collection period. The diagnosis of BPH was established through comprehensive clinical evaluation, digital rectal examination (DRE), and transabdominal ultrasound findings.

Eligible participants were male patients aged 40 years and above with a confirmed physician diagnosis of BPH. Patients were excluded if they were critically ill, had severe physical disabilities, or presented with symptomatic co-infections, sepsis, or uropathologic conditions such as urinary stones and urogenital cancer. Those with a history of prostate or urethral surgery were also excluded. Additionally, individuals taking medications that could alter or control bladder symptoms, including anticholinergics, 5α-reductase inhibitors, phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors, and hormone replacement therapy, were not eligible for the study.

Sample size and sampling procedures

The sample size was determined using OpenEpi (Version 3.01) based on the odds ratio (OR) method using the following assumptions: Considering a 95% CI, 80% power. The sample size was obtained by taking hypertension as a risk factor from a previous study, where the proportion of hypertension among non-severe prostatic symptoms was 19.4%, and an odds ratio of 2.529. Accordingly, the total sample size becomes 2014. When the 10% non-response rate was added, the final sample size became 235.

Each BPH patient who fulfilled the inclusion criteria was selected as a study participant through a consecutive sampling technique. When the subject did not meet the inclusion criteria, the next client was approached until the recommended sample size was reached. The participants were assigned based on the IPSS urological scores30. According to the criteria, participants were categorized as mildly to moderately symptomatic (IPSS: 0–19) or as severely symptomatic (IPSS: 20–35).

Study variables

The outcome variable in this study was BPH severity, categorized as severely symptomatic (IPSS: 20–35) and asymptomatic to moderately symptomatic (IPSS: 0–19). Independent variables included sociodemographic factors such as age, occupation, educational status, and residence. Comorbidities, including a history of coronary heart disease, diabetes, and hypertension, were also considered. Physical measurements such as blood pressure (BP), body mass index (BMI), and waist circumference (WC) were included. Behavioral factors such as alcohol consumption, cigarette smoking, khat chewing, physical exercise, and fruit and vegetable intake were also assessed. Additionally, fasting blood sugar levels and immune-inflammatory indices, including the systemic immune-inflammation index (SII), pan immuno-inflammatory index (PII), neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), platelet-lymphocyte ratio (PLR), and lymphocyte to monocyte ratio (LMR), were analyzed. Prostate-related factors, such as prostate size and the duration since BPH diagnosis, were also setting and period.

Operational definitions

Alcohol drinking status: Alcohol drinker

Defined as the intake of any type of alcoholic beverage, such as beer, wine, or locally prepared alcoholic beverages, more than once per week in the past one year, regardless of the amount; non-drinkers who drink less than once per week for the last one year or never drink alcoholic products31.

Diabetes

Was considered if a diagnosis is recorded by a physician, or the participant is under treatment, or FBS ≥ 126 mg/dl during the time of data collection32.

Hypertension

was considered if a diagnosis is recorded by a physician, or the patient is under treatment, or has resting BP measurements of SBP ≥ 130 mmHg and/or DBP ≥ 85 mmHg33.

Khat chewer

Participants who have been chewing khat in any amount during the past year, otherwise non-chewers34.

Low fruit and vegetable intake

It was defined as consuming less than five servings (400 grams) of fruit and vegetables per day. For raw green leafy vegetables, 1 serving = one cup; for cooked or chopped vegetables, 1 serving = ½ cup; for fruit (apple, banana, orange etc…), 1 serving = 1 medium size piece; for chopped, cooked and canned fruit, 1 serving = ½ cup; and for juice from fruit, 1 serving = ½ cup35.

Low–level physical activity

A person not meeting any of the criteria for the moderate- or high-level categories36.

Moderate-physical activity

Any activity that causes a small increase in breathing or heart rate (brisk walking or carrying light loads) that continues for at least 30 min with a minimum of 3 days per week or 5 or more days of these activities for at least 20 min per day or ≥ 3 days of vigorous-intensity activity per week of at least 20 min per day36.

Severity of BPH

The severity of BPH was quantified by the American Urological Association or International Prostate Symptom Scoring (IPSS) system, recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO, 1991) as the preferred instrument to measure BPH symptoms. It consists of seven symptoms: intermittency, urgency, weak stream, incomplete emptying, straining, frequency, and nocturia. Each participant was asked to rate the severity of their symptoms on a six-point sub-scale, from a minimum score of 0 to a maximum score of 5, with the lowest score reflecting ‘no symptoms. The sum of all the answers made up an IPSS total score (score range 0–35 points), which was grouped into asymptomatic to moderately symptomatic(< 19) and severe (≥ 20)30.

Smoking status

Smoker:-those who have a cigarette smoking practice within the last one year, irrespective of the amount, Non-smokers:- who never smoked in their lifetime or smokers before one year34.

High–level physical activity

Any activity that causes a large increase in breathing or heart rate if continued for at least 30 min (e.g., running, carrying or lifting heavy loads, digging or construction work) for a minimum of three days per week36.

Weight classifications by BMI

Underweight (BMI < 18.5), normal weight (BMI 18.5–24.9), overweight (BMI 25–29.9.9), and obese (BMI ≥ 30)36.

Immune-inflammatory indices

SII was calculated as platelet × neutrophil/lymphocyte37.

PII was calculated as neutrophil count× platelet count (× monocyte count/lymphocyte count38.

NLR was calculated as the ratio of neutrophils to lymphocytes in peripheral blood39.

PLR: was calculated as the ratio of platelets to lymphocytes in peripheral blood39.

Data and blood sample collection procedure

Trained data collectors conducted interviews using an Amharic version questionnaire to gather relevant information. Blood samples (approximately 5 mL) were collected using a sterile technique after participants had undergone overnight fasting or a minimum of 8 h of fasting. Informed consent was obtained before collecting samples for fasting blood sugar (FBS) and complete blood count (CBC) analysis. A well-trained laboratory technician performed the tests using a calibrated chemistry analyzer, adhering strictly to standard operating procedures. Participants with abnormal test results were referred to the follow-up unit for further evaluation. The data collection process, including anthropometric, clinical, and biochemical measurements, was supervised by the principal investigator and a designated supervisor to ensure accuracy and quality control.

Questionnaire tool

Data was collected using a structured questionnaire via the KoboCollect application on Android phones. The questionnaire was designed and uploaded into the KoboCollect platform, which allowed for efficient data entry and real-time data monitoring. Behavioral factors such as smoking, khat chewing, alcohol consumption, physical activity, and fruit and vegetable intake were also assessed. The International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) was applied to evaluate BPH symptom severity30. Data collection was conducted through face-to-face interviews.

Physical measurements, including weight, height, waist circumference, and blood pressure, were taken using the WHO stepwise approach36, with calibrated equipment operated by trained health professionals. Height was measured with participants standing upright, and weight was recorded without shoes or heavy items. Waist circumference was measured midway between the lower ribs and iliac crest using a non-stretch tape. Height and weight were approximated to the nearest 0.1 cm and 0.1 kg, respectively, and BMI was calculated as weight (kg) divided by height squared (m²). A physician performed a digital rectal examination to estimate prostate size.

Laboratory analysis

Determination of hematological parameters/or immuno–inflammatory indices

A complete blood count (CBC) was performed using an automated hematology analyzer. The machine automatically measured white blood cells (e.g., lymphocytes, neutrophils, monocytes) and platelets. Additional immune-inflammatory indices were calculated, including the SII, PII, PLR, and NLR.

Determination of fasting serum glucose

Fasting serum glucose was measured using the enzymatic glucose oxidase method with a commercial reagent kit40. As a principle, the glucose in the sample could be oxidized to D-gluconic acid and hydrogen peroxide in the presence of glucose oxidase (GOD). Hydrogen peroxide then reacted with phenol and 4-aminoantipyrine, catalyzed by peroxidase (POD), forming a pink-colored quinoneimine compound. The intensity of the color, measured at 520 nm, is directly proportional to the glucose concentration in the sample.

Data quality control

Data quality was ensured through the proper design and pretesting of the questionnaire. The questionnaire was initially prepared in English, translated into Amharic, and then back-translated into English. A pretest was conducted on 10% of the total sample (22 participants) at Boru Meda General Hospital to assess the reliability of the items, and necessary modifications were made accordingly.

Before data collection, training was provided to data collectors on the study objectives, methodology, relevance, and on using the KoboCollect platform. Data quality was further ensured by strictly adhering to the manufacturer’s instructions and standard operating procedures during the laboratory testing processes. Special attention was given to biochemical analyses, and reagent expiration dates were checked. After data collection, each questionnaire was reviewed daily for completeness, clarity, and consistency.

Data processing and analysis

The data collected using the KoboCollect application on Android phones were imported into STATA 17 for processing and analysis. After data collection, the responses were synchronized from the mobile devices and exported in a format compatible with STATA for further analysis. The data were first cleaned to ensure accuracy, completeness, and consistency. Any inconsistencies, missing values, or outliers were checked. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the sociodemographic, behavioral, and clinical characteristics of the participants. For analysis, categorical variables were coded numerically, and continuous variables were checked for normality. The associations between the outcome variable and potential predictors were investigated using the bivariable and multivariable binary logistic regression model. Variables with a p-value < 0.25 in the bivariable logistic regression were fitted into the multivariable logistic regression model for final analysis. Adjusted odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were used for the interpretation of the strength of prediction of the independent variables to the outcome. A P-value of < 0.05 at 95% in multivariable logistic regression was considered as statistically significant. The goodness of fit of the model was tested by the Hosmer-Lemeshow test. The predictive performance of immune-inflammation indices levels for the symptom severity of BPH was evaluated using a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis. The sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of the immune-inflammation indices test were calculated using a cut-off value that was selected from the ROC curve, and the Youden Index was used to identify the optimal cut-off values. Pairwise comparisons of AUCs were conducted using DeLong’s test to evaluate whether differences in discriminative ability between indices were statistically significant. In addition, the relationship between immune-inflammation indices such as systemic immune-inflammation index (SII) and severe BPH was explored using Locally Estimated Scatterplot Smoothing (LOESS). LOESS is a non-parametric method that fits a smooth curve through scatterplot data, allowing visualization of potential non-linear associations between predictor and outcome.

Ethical approval and participants’ consent

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Before the study began, ethical clearance was obtained from the ethical review committee of the College of Medicine and Health Science, Wollo University [Ref. No- CMHS1119/20/2024]. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before the interview. Privacy, anonymity, and confidentiality were ensured throughout the study process. Participants were informed that refusing consent or withdrawing from the study would not negatively affect their access to healthcare.

Results

Background characteristics of the study participants

A total of 232 patients diagnosed with benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) were included in the study, with a response rate of 98.72%. The mean age of the participants was 66.92 years (range: 40 to 90 years). The majority of participants, 157 (67.67%), were from rural areas, and 106 (45.7%) did not receive formal education. The most common comorbid condition observed was hypertension (21.98%). Additionally, 131 (56.47%) and 148 (63.79%) of the participants were non-drinkers of alcohol and non-chewers of khat, respectively (Table 1).

Anthropometric and laboratory findings

The study revealed that the median systolic blood pressure (SBP) was 130 mmHg, with an interquartile range (IQR) of 120 to 140 mmHg. Central obesity was noted among 45 participants, representing 19.4% of the sample. The average prostate size was 52.29 ± 33.17 cubic centimeters. The median fasting blood sugar (FBS) level was 98 mg/dL, with an IQR of 89.25 to 108 mg/dL. The mean lymphocyte count was 1.71 × 10³ cells/µL, with a range from 1.37 to 2.43 × 10³ cells/µL. Furthermore, the Systemic Inflammation Index (SII) had a median value of 474.12 × 103, with an IQR ranging from 215.85 to 949.59 × 103 (Table 2).

Symptom scores of benign prostatic hyperplasia

The analysis of the prostatic symptom score of the participants revealed varying levels in both storage and voiding symptoms. Among storage symptoms, nocturia had a mean score of 2.09 ± 1.695, while urgency was reported with a higher mean score of 2.76 ± 1.721. Voiding symptoms were also notable, with weak stream averaging 2.23 ± 1.651 and straining at 2.21 ± 1.601. Regarding overall BPH symptom severity, as measured by the International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS), the majority of participants (148, 63.79%) experienced mild to moderate symptoms (Table 3). Further stratification by age revealed that patients over 65 years of age exhibited a higher prevalence of severe symptoms (42.5%), Fig. 1.

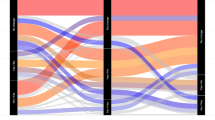

Predictive value of immune–inflammatory indices in predicting severe symptoms of benign prostatic hyperplasia

The predictive value and optimal cut-off values of hematological-derived immune-inflammatory indices, SII, PII, NLR, and LMR, were evaluated in assessing severe symptoms of BPH. Accordingly, the SII exhibited the highest area under the curve (AUC) at 0.736 (95% CI: 0.67–0.80), with an optimal cut-off value of 564.92 × 10³, achieving 72% specificity and 69% sensitivity. Similarly, the Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Index (PII) had an AUC of 0.729 (95% CI: 0.66–0.796), with a cut-off of 273.3 × 106 specificity of 69%, and sensitivity of 69% (Fig. 2), (Table 4).

Conversely, the LMR had the lowest predictive performance, with an AUC of 0.403 (95% CI: 0.328–0.477) (Fig. 3).

Pairwise comparisons using DeLong’s test indicated that SII was significantly superior to NLR (χ² = 13.08, p = 0.0003) and PLR (χ² = 4.06, p = 0.044), but not significantly different from PII (χ² = 0.09, p = 0.769) (Table 5).

The relationship between the SII and Severe BPH was further explored using a LOESS plot (Fig. 4). The curve demonstrates a positive, non-linear association. At low SII values (≈ 0–500 × 103), the estimated probability of severe BPH was near zero but rises rapidly with small increases in SII. In the mid-range (≈ 500 × 103 − 2000 × 103), the probability shows minor fluctuations but generally increases to around 0.2–0.4. At higher SII levels (> 2000 × 103), the probability rises steadily toward 1.0, indicating that very high SII values are associated with a substantially increased likelihood of severe symptoms. Overall, these results suggest a threshold-dependent relationship, supporting SII as a potential predictive marker for Severe BPH.

Symptom severity predictors of Benign prostatic hyperplasia

The associations between the severity of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) symptoms and potential predictors were analyzed using bivariable and multivariable binary logistic regression models. In the bivariable analysis, age, residence, physical activity, number of servings of FEV int6ake, khat chewing, duration of BPH, prostate size, BMI, central obesity, DM, hypertension, SII, PII, and NLR, had a p-value < 0.25 and were fitted into the multivariable binary logistic regression model for final analysis. Findings of multivariable analysis indicated that age, level of physical activity, central obesity, SII, PII, and NLR were significantly associated with the symptom severity of BPH.

The odds of experiencing severe BPH symptoms among individuals aged 65 years and older were 2.55 times higher compared to those aged < 65 (AOR = 2.55, 95% CI: 1.19, 5.45, p = 0.016), assuming that the effect of other covariates is constant. Similarly, individuals with low physical activity had 2.56 times higher odds of severe symptoms compared to those with adequate physical activity (AOR = 2.56, 95% CI: 1.22–5.35, p-value = 0.013). Furthermore, the odds of experiencing severe BPH symptoms among individuals with central obesity were 2.79 times higher than those without central obesity (AOR = 2.79, 95% CI: 1.07–7.25, P = 0.035), assuming that the effect of other covariates is constant. Regarding inflammatory markers, individuals with elevated SII values (≥ 564.92 × 103) had 2.97 times greater odds of severe BPH symptoms than those with lower SII values (AOR = 2.97, 95% CI: 1.10–7.98, p-value = 0.031). Likewise, individuals with PII values ≥ 273.3 × 106 were 2.46 times more likely to experience severe symptoms than those with lower PII values (AOR = 2.46, 95% CI: 1.04–5.86, p-value = 0.042), assuming other factors remain constant. Moreover, for patients with NLR values ≥ 1.368, the odds of severe BPH symptoms were 2.87 times higher compared to those with lower NLR values (AOR = 2.87, 95% CI: 1.01–8.14, p-value = 0.048), provided that the effect of other covariates is controlled (Table 6).

Discussion

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) is a common age-related condition that significantly impacts the quality of life of older men2. Characterized by the non-malignant enlargement of the prostate gland, BPH leads to LUTS, including frequency, urgency, nocturia, and weak urinary stream7. The severity of these symptoms varies widely, and identifying predictors of severe BPH is crucial for timely intervention and management. This study investigated the predictors of symptom severity and the predictive performance of immune-inflammatory markers in BPH patients attending Dessie Comprehensive Specialized Hospital. The findings revealed that 84 (36.21%) of the study population exhibited severe BPH symptoms, indicating the significant clinical burden of this condition within the studied setting. Furthermore, several factors, including age ≥ 65 years, low physical activity, central obesity, elevated Prostate Inflammation Index (PII), increased Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio (NLR), and elevated Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratio (PLR), demonstrate a statistically significant association with the severity of BPH symptoms.

The observation that advanced age (≥ 65 years) is significantly associated with severe BPH symptoms aligns with established literature7,14,41. Age-related hormonal changes, particularly the decline in testosterone and the relative increase in estrogen, are believed to play a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of BPH42. Moreover, the progressive structural and functional changes in the prostate gland with advancing age contribute to the development and exacerbation of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS)43. The present study’s finding reinforces the understanding that age remains a crucial independent predictor of BPH; hence, regular screening and early intervention in older individuals are essential to prevent disease progression.

Low physical activity was also significantly associated with severe BPH symptoms. This finding aligns with growing evidence highlighting the protective role of exercise against BPH progression and its severity14,44. Reduced physical activity can lead to metabolic disturbances, increased systemic inflammation, and hormonal imbalances, all of which may promote prostatic hyperplasia and worsen symptom severity45. Encouraging lifestyle modifications, including increased physical activity, could be a crucial strategy for modifying BPH severity. The observed association between central obesity and severe BPH symptoms agrees with previous studies46,47,48, where waist circumference and metabolic syndrome components were linked to increased BPH severity. The possible explanation is that visceral fat contributes to systemic inflammation, insulin resistance, and altered hormone metabolism, which can accelerate prostatic growth and worsen urinary symptoms49.

Another main finding was the association between derived immune-inflammatory markers and severe BPH symptoms. The results demonstrated that higher levels of SII, PII, and NLR were independent predictors of severe symptoms, reinforcing the role of systemic inflammation in BPH progression. Patients with elevated SII values ≥ 564.92 × 103 had a higher likelihood of experiencing severe symptoms compared to those with lower SII values. Pairwise DeLong tests confirmed that SII significantly outperformed NLR and PLR, although it was comparable to PII. The LOESS analysis further demonstrated a positive, non-linear relationship between SII and the probability of severe BPH, with the risk increasing sharply at higher SII levels. This threshold-dependent pattern suggests that markedly elevated systemic inflammation disproportionately contributes to symptom severity. These results reinforce the role of systemic inflammation in BPH progression and support the potential use of SII as a complementary biomarker for risk stratification and patient monitoring. SII reflects the systemic inflammatory response, and while SII has been primarily studied in oncology, emerging evidence, including our study, suggests its relevance in the context of BPH and LUTS progression, aligning with previous reports22,23. Other studies have also explored the association of SII in the context of LUTS and found that elevated SII levels were significantly correlated with the clinical progression of LUTS in older men22.

Similarly, individuals with a PII value of ≥ 273.3 × 106 also face greater odds of severe symptoms. These findings align with previous research indicating that inflammatory pathways, particularly neutrophil activation and platelet aggregation, play a role in prostate tissue remodeling and disease severity50. This also supports the growing evidence highlighting chronic inflammation as a critical driver of BPH progression51.

The observed association of NLR with severe BPH symptoms also supports existing research that highlights the involvement of neutrophils and lymphocytes in prostatic inflammatory processes52. NLR, a widely recognized marker of systemic inflammation, reflects the dynamic balance between pro-inflammatory (neutrophils) and anti-inflammatory (lymphocytes) components of the immune response. This association between high NLR and severe BPH symptoms is in line with previous studies, which found that increased NLR levels were linked to worse prostatic symptoms53. Some studies have consistently demonstrated that elevated NLR levels were significantly associated with an increased risk of LUTS and symptom progression in BPH54. Further supporting this association, other studies proposed that higher NLR levels could serve as an indicator of severe LUTS and BPH progression18,53.

Beyond identifying associations, this research evaluated the capacity of readily available, hematology-derived inflammatory indices to predict the presence of severe BPH symptoms. The results indicate that SII exhibited the highest area under the curve (AUC) at 0.736 with an optimal cut-off value of 564.92 × 10³. This suggests that a fair-to-moderate ability of SII to discriminate between patients with and without severe BPH symptoms55. SII is a composite marker that reflects the balance between systemic inflammation and immune response. While this study identified an optimal cut-off value of 564.92 × 103, it is important to note that other studies may have identified different optimal cut-off values for SII in the context of BPH. For example, one study reported a very high AUC of 1.0 for SII in diagnosing BPH and its progression19.

The PII showed similar predictive performance, with an AUC of 0.729. The comparable performance of SII and PII suggests that integrating platelet counts (as done in both SII and PII) alongside neutrophil and lymphocyte counts may provide valuable information for predicting BPH severity in this study. Both markers represent composite indices reflecting systemic inflammation and immune cell balance, potentially capturing different facets of the inflammatory situation contributing to severe symptoms54. While NLR was identified as a significant predictor in the association analysis, its specific predictive performance (AUC) was seemingly lower than SII and PII. However, their established association may support their relevance in the context of BPH inflammation.

Although PLR had a moderate predictive performance (AUC = 0.67), it was not significantly associated with severe BPH in the multivariable analysis. This indicates that while PLR reflects systemic inflammatory status, it may have less discriminatory power for identifying severe BPH compared to SII and PII in this setting. Previous studies have reported mixed findings regarding PLR, with some showing a significant association with LUTS severity19,56,57 and others finding no strong correlation58. Elevated PLR suggests that platelet-mediated inflammation contributes to BPH severity, possibly through vascular dysfunction and the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines that exacerbate prostatic hyperplasia and lower urinary tract symptoms59. However, the lack of significance in our study might be due to the overlap of PLR values between mild/moderate and severe cases, a smaller sample size, or population-specific inflammatory responses. Nevertheless, PLR’s moderate predictive value suggests it could still serve as a supportive marker in combination with other indices, even if it is not independently predictive in this cohort.

Strengths and limitations of the study

This study highlights significant factors associated with severe BPH symptoms, contributing to the understanding of BPH severity risk factors. It also provides valuable insights into the predictive performance of easily accessible immune-inflammatory markers in assessing BPH symptom severity, which can aid in early symptom stratification. However, this study has some limitations. First, it was conducted at a single center, which may limit the generalizability of the results to broader populations. Second, unmeasured confounders that may influence both inflammation and BPH severity were not extensively explored. Third, the absence of prostatic tissue analysis means we could not directly assess local inflammatory processes within the prostate. Finally, the optimal cut-off values for the inflammatory markers, derived from this specific population, require external validation before wider clinical application. Therefore, while this study provides valuable preliminary insights, future research should focus on prospective, multicenter studies with detailed assessments to confirm these findings and explore the underlying mechanisms linking systemic inflammation to BPH symptom severity.

Implications and future directions

The findings suggest that easily derivable immuno-inflammatory indices, particularly SII and PII, reflect underlying inflammatory processes related to BPH severity and hold moderate potential as predictive markers. DeLong’s test further confirmed that SII demonstrated superior discriminative accuracy compared to other indices, supporting its clinical relevance in identifying patients at higher risk of severe symptoms. Clinicians in similar settings could consider these markers, calculated from routine complete blood counts, as supplementary information to standard clinical assessment tools for patient evaluation and stratification. Elevated SII or PII values may indicate a higher likelihood of severe symptoms, prompting clinicians to prioritize these patients for closer monitoring, early interventions, or consideration of anti-inflammatory therapeutic strategies. Specifically, these markers could be incorporated into routine laboratory assessments for patients presenting with BPH symptoms to help identify individuals at higher risk of severe symptoms. Early recognition of high-risk patients using these indices may allow for timely intervention, closer monitoring, and informed personalized treatment strategies. Nonetheless, further prospective studies are needed to validate their predictive performance, establish standardized cut-off values, and develop practical protocols for integrating them into routine patient management.

Future research should focus on validating these findings in larger, prospective, multi-center studies to affirm the predictive performance of SII and PII and their respective cut-off values across diverse populations. Longitudinal studies are essential to establish causality and understand how changes in these markers over time correlate with disease progression or response to treatment. Investigating the specific inflammatory pathways linking elevated SII, PII, and NLR to prostatic inflammation and LUTS development would also be valuable. Furthermore, exploring the combined predictive value of these markers with established clinical parameters could lead to more robust prediction models for severe BPH.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study identified that age, central obesity, physical inactivity, and high inflammatory markers (SII, PII, NL) were found to be independent predictors of severe BPH symptoms. Additionally, the predictive performance of hematological-derived immune-inflammatory indices was evaluated with severe BPH symptoms, and SII and PII demonstrated the highest predictive capabilities, with SII showing superior discriminative accuracy. These findings underscore the role of systemic inflammation in BPH progression and suggest that hematological inflammatory indices may serve as practical, cost-effective tools for early identification and management of patients at risk for symptom stratification. Future research should focus on validating these markers across diverse populations and exploring targeted interventions to mitigate inflammation-related BPH progression.

Data availability

The datasets used or analyzed in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- BPH:

-

Benign prostatic hyperplasia

- BOO:

-

Bladder outlet obstruction

- BP:

-

Blood pressure

- BPE:

-

Benign prostatic enlargement

- CVDs:

-

Cardiovascular diseases

- CBC:

-

Complete blood count

- FBS:

-

Fasting blood sugar

- IPSS:

-

International prostate symptom score

- LOESS:

-

Locally estimated scatterplot smoothing

- LUTS:

-

Lower urinary tract symptoms

- NLR:

-

Neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio

- PII:

-

Pan immuno-inflammatory index

- PL:

-

Platelet–lymphocyte ratio

- SII:

-

Systemic immune-inflammation index

- WBC:

-

White blood cells

- WC:

-

Waist circumference

References

Chughtai, B., Lee, R., Te, A. & Kaplan, S. Role of inflammation in benign prostatic hyperplasia. Rev. Urol. 13 (3), 147 (2011).

Untergasser, G., Madersbacher, S. & Berger, P. Benign prostatic hyperplasia: age-related tissue-remodeling. Exp. Gerontol. 40 (3), 121–128 (2005).

Kim, E. H., Larson, J. A. & Andriole, G. L. Management of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Annu. Rev. Med. 67 (1), 137–151 (2016).

McNeal, J. E. The zonal anatomy of the Prostate. Prostate 2 (1), 35–49 (1981).

Egan, K. B. The epidemiology of benign prostatic hyperplasia associated with lower urinary tract symptoms: prevalence and incident rates. Urologic Clin. 43 (3), 289–297 (2016).

Nickel, J. C. Inflammation and benign prostatic hyperplasia. Urol. Clin. North Am. 35 (1), 109–115 (2008).

Park, H. J., Won, J. E. J., Sorsaburu, S., Rivera, P. D. & Lee, S. W. Urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) secondary to benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) and LUTS/BPH with erectile dysfunction in Asian men: a systematic review focusing on Tadalafil. World J. Men’s Health. 31 (3), 193–207 (2013).

Chughtai, B. et al. Benign prostatic hyperplasia. Nat. Reviews Disease Primers. 2 (1), 1–15 (2016).

Speakman, M., Kirby, R., Doyle, S. & Ioannou, C. Burden of male lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) suggestive of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH)–focus on the UK. BJU Int. 115 (4), 508–519 (2015).

Nickel, J. C. Inflammation and benign prostatic hyperplasia. Urol. Clin. North Am. 35, 109–115 (2008).

Parsons, J. K., Sarma, A. V., McVary, K. & Wei, J. T. Obesity and benign prostatic hyperplasia: clinical connections, emerging etiological paradigms and future directions. J. Urol. 182, S27-31 (2009).

Parsons, J. K. Modifiable risk factors for benign prostatic hyperplasia and lower urinary tract symptoms: new approaches to old problems. J. Urol. 178 (2), 395–401 (2007).

Tiruneh, T., Getachew, T., Getahun, F., Gebreyesus, T. & Meskele, S. Magnitude and factors associated with benign prostatic hyperplasia among adult male patients visiting Wolaita Sodo university comprehensive specialized hospital Southern Ethiopia. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 31556 (2024).

Smith, D. P. et al. Relationship between lifestyle and health factors and severe lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) in 106,435 middle-aged and older Australian men: population-based study. PloS One. 9 (10), e109278 (2014).

Kaplan, S. A. & Re Relationship among diet habit and lower urinary tract symptoms and sexual function in Outpatient-Based males with LUTS/BPH: A multiregional and Cross-Sectional study in China. J. Urol. 200 (3), 472 (2018).

Bostanci, Y., Kazzazi, A., Momtahen, S., Laze, J. & Djavan, B. Correlation between benign prostatic hyperplasia and inflammation. Curr. Opin. Urol. 23 (1), 5–10 (2013).

Torkko, K. C. et al. Prostate biopsy markers of inflammation are associated with risk of clinical progression of benign prostatic hyperplasia: findings from the MTOPS study. J. Urol. 194 (2), 454–461 (2015).

Tanik, S. et al. Is the neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio an indicator of progression in patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia? Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prevention: APJCP. 15 (15), 6375–6379 (2014).

Ahmed, R., Hamdy, O. & Awad, R. M. Diagnostic efficacy of systemic immune-inflammation biomarkers in benign prostatic hyperplasia using receiver operating characteristic and artificial neural network. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 14801 (2023).

Wang, S. et al. The values of systemic immune-inflammation index and neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio in the localized prostate cancer and benign prostate hyperplasia: a retrospective clinical study. Frontiers Oncol. 11, 812319 (2022).

Man, Y. & Chen, Y. Systemic immune-inflammation index, serum albumin, and fibrinogen impact prognosis in castration-resistant prostate cancer patients treated with first-line docetaxel. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 51 (12), 2189–2199 (2019).

Horsanali, M. O., Dil, E., Caglayan, A., Ekren, F. & Ozsagir, Y. O. The predictive value of the systemic Immune-Inflammation index for the progression of lower urinary tract symptoms in men. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prevention: APJCP. 24 (11), 3845–3850 (2023).

Wang, S. et al. The values of systemic Immune-Inflammation index and Neutrophil-Lymphocyte ratio in the localized prostate cancer and benign prostate hyperplasia: A retrospective clinical study. Front. Oncol. 11, 812319 (2021).

Joseph, M. A. et al. Risk factors for lower urinary tract symptoms in a population-based sample of African-American men. Am. J. Epidemiol. 157 (10), 906–914 (2003).

Hong, J. et al. Risk factors for benign prostatic hyperplasia in South Korean men. Urol. Int. 76 (1), 11–19 (2006).

Misnadin, I. W., Adu, A. A. & Hinga, I. A. T. Risk factors associated with prostate hyperplasia at Prof. Dr. WZ Johannes hospital. Indonesian J. Med. 1 (1), 50–57 (2016).

Amalia, R. Risk Factors in occurrence of Benign Prostate Enlargement (Case Study on RS Kariadi, RSI Sultan Agung, Semarang Roemani RS). Semarang: Diponegoro University School of Medicine (2010).

Xiong, Y., Zhang, Y., Li, X., Qin, F. & Yuan, J. The prevalence and associated factors of lower urinary tract symptoms suggestive of benign prostatic hyperplasia in aging males. Aging Male. 23 (5), 1432–1439 (2020).

El-Gilany, A-H., Alam, R. R. & Elhameed, S. H. A. (eds) Severe Symptoms of Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia: Prevalence, Associated Factors and Effects on Quality Of Life of Rural Dwelling Elderly 2016.

Barry, M. J. & O’Leary, M. P. The development and clinical utility of symptom scores. Urol. Clin. North Am. 22 (2), 299–307 (1995).

Association, E. P. H. 22nd Annual Conference of EPHA. On Alcohol, Substance, Khat and Tobacco. April (2012).

Alberti, K. G., Zimmet, P. & Shaw, J. Metabolic syndrome–a new world-wide definition. A consensus statement from the international diabetes federation. Diabet. Medicine: J. Br. Diabet. Association. 23 (5), 469–480 (2006).

Detection & NCEPEPo Adults ToHBCi. Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on detection, evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) (The Program, 2002).

Tesfaye, F., Byass, P., Wall, S., Berhane, Y. & Bonita, R. Association of smoking and Khat (Catha Edulis Forsk) use with high blood pressure among adults in addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2006. Prev. Chronic Dis. 5 (3), A89 (2008).

Gelibo, T. et al. Low fruit and vegetable intake and its associated factors in ethiopia: A community based cross sectional NCD steps survey. Ethiop. J. Health Dev. 31 (1), 355–361 (2017).

WHO. The WHO STEPwise approach to noncommunicabledisease risk factor surveillance manual. 26 January (2017).

Hu, B. et al. Systemic immune-inflammation index predicts prognosis of patients after curative resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 20 (23), 6212–6222 (2014).

Fucà, G. et al. The pan-immune-inflammation value is a new prognostic biomarker in metastatic colorectal cancer: results from a pooled-analysis of the Valentino and TRIBE first-line trials. Br. J. Cancer 123(3), 403–409 (2020).

Guo, J. et al. Prognostic role of neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio and platelet to lymphocyte ratio in prostate cancer: a meta-analysis of results from multivariate analysis. Int. J. Surg. 60, 216–223 (2018).

Kumar, V. & Gill, K. D. Estimation of Blood Glucose Levels by Glucose Oxidase Method. Basic Concepts in Clinical Biochemistry: A Practical Guide 57–60 (Springer, 2018).

Adegun, P. T., Adebayo, P. B. & Areo, P. O. Severity of lower urinary tract symptoms among middle aged and elderly Nigerian men: impact on quality of life. Adv. Urol. 2016(1), 1015796 (2016).

Adejumo, B. I. G. et al. Serum levels of reproductive hormones and their relationship with age in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia in Benin City, Edo State. Health 12, 1121–1131 (2020).

Umar, M. et al. Age-Related anatomical variations in the prostate Gland, implications for urological health and disease progression. Pakistan J. Med. Health Sci. 17 (10), 61 (2023).

Calogero, A. E., Burgio, G., Condorelli, R. A., Cannarella, R. & La Vignera, S. Epidemiology and risk factors of lower urinary tract symptoms/benign prostatic hyperplasia and erectile dysfunction. Aging Male. 22 (1), 12–19 (2019).

Mondul, A. M., Giovannucci, E. & Platz, E. A. A prospective study of physical activity, sedentary behavior, and incidence and progression of lower urinary tract symptoms. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 35, 2281–2288 (2020).

Lee, S. H. et al. Effects of obesity on lower urinary tract symptoms in Korean BPH patients. Asian J. Androl. 11 (6), 663 (2009).

Lee, J. et al. Lowering the percent body fat in the obese population might reduce male lower urinary tract symptoms. World J. Urol. 41 (6), 1621–1627 (2023).

Gacci, M. et al. Central obesity is predictive of persistent storage lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) after surgery for benign prostatic enlargement: results of a multicentre prospective study. BJU Int. 116 (2), 271–277 (2015).

He, Q. et al. Metabolic syndrome, inflammation and lower urinary tract symptoms: possible translational links. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 19 (1), 7–13 (2016).

Mugisha Emmanuel, K. Pathophysiology of Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms).

De Nunzio, C., Presicce, F. & Tubaro, A. Inflammatory mediators in the development and progression of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Nat. Reviews Urol. 13 (10), 613–626 (2016).

Samarinas, M., Gacci, M., De La Taille, A. & Gravas, S. Prostatic inflammation: a potential treatment target for male LUTS due to benign prostatic obstruction. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 21 (2), 161–167 (2018).

Ozer, K., Horsanali, M. O., Gorgel, S. N., Horsanali, B. O. & Ozbek, E. Association between benign prostatic hyperplasia and neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio, an indicator of inflammation and metabolic syndrome. Urol. Int. 98 (4), 466–471 (2017).

Zhang, Q., Pang, S., Zhang, Y., Jiang, K. & Guo, X. Association between inflammation and lower urinary tract symptoms of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Urol. J. 17 (5), 505–511 (2020).

Mandrekar, J. N. Receiver operating characteristic curve in diagnostic test assessment. J. Thorac. Oncology: Official Publication Int. Association Study Lung Cancer. 5 (9), 1315–1316 (2010).

Chen, G. & Feng, L. Analysis of platelet and monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio and diabetes mellitus with benign prostatic enlargement. Front. Immunol. 14, 1166265 (2023).

Shi, C., Cao, H., Zeng, G., Yang, L. & Wang, Y. The relationship between complete blood cell count-derived inflammatory biomarkers and benign prostatic hyperplasia in middle-aged and elderly individuals in the united states: evidence from NHANES 2001–2008. Plos One. 19 (7), e0306860 (2024).

Kang, J. Y. et al. Association of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio, and lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio with benign prostatic hyperplasia: a propensity score-matched analysis. Urol. Int. 105 (9–10), 811–816 (2021).

Lin, P-A. et al. Prostate Tissue-Induced platelet activation and platelet–Neutrophil aggregation following transurethral resection of the prostate surgery: an in vitro study. Biomedicines 13 (4), 1006 (2025).

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to Wollo University for providing the necessary materials and support that made this research possible. Our heartfelt thanks also go to the study participants, whose willingness to contribute their time and insights was invaluable. We are equally grateful to the data collectors for their dedication and effort in ensuring the accuracy and completeness of the data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. GA led conceptualization, methodology, and project administration. ABK was responsible for data curation and formal analysis. ABK and SMA contributed to the writing, original draft preparation, as well as reviewing and editing the manuscript. All authors read and approved of the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kassaw, A.B., Abdu, S.M. & Abebe, . Predictors and predictive performance of immune–inflammation indices for symptom severity in benign prostatic hyperplasia. Sci Rep 16, 1202 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30765-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30765-0