Abstract

Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) is a complex, age-related cardiovascular disease with limited treatment options, partly due to a poor understanding of underlying mechanisms, lack of robust preclinical models and diagnostic tools with limited specificity. Traditional cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) protocols and analysis in preclinical research are time-consuming, and manual analysis methods are prone to high inter-observer variability (correlation coefficient of 0.79 for left ventricular (LV) ejection fraction between observers). To accelerate and standardize phenotyping, we optimized a comprehensive non-contrast cardiac MRI protocol for high throughput, enabling acquisition of a stack of 12 short-axis slices in approximately seven minutes. This time-efficiency allowed us to add additional sequences, including cine-Arterial Spin Labeling (ASL) for myocardial perfusion mapping and dobutamine stress testing, allowing for a comprehensive cardiac exam. We developed a deep learning approach utilizing 3D Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) for fully automated segmentation and quantification of cardiac function. We validated this comprehensive pipeline in two multifactorial mouse models of HFpEF, combining diet-induced obesity (DIO) or high fat diet (HFD) and the hypertensive agent, deoxycorticosterone pivalate (DOCP). Our approach illustrated high technical sensitivity by detecting significant myocardial perfusion reduction in both the DIO (p = 0.02) and DIO + DOCP (p = 0.03) groups compared to control, along with subtle diastolic abnormalities, even in the absence of overt changes in ejection fraction. The CNN demonstrated high accuracy and reproducibility, achieving a mean Dice similarity coefficient greater than 0.9 for segmentation and Intraclass Correlation Coefficients (ICC) exceeding 0.95 for key left ventricular functional parameters (volumes and mass) compared to expert consensus reads. This optimized protocol and automated analysis pipeline provides a valuable tool for preclinical cardiovascular research, enabling efficient and reliable assessment of cardiac remodeling and contributing to a deeper understanding of HFpEF progression.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), a subtype of heart failure, poses a significant global health burden, affecting up to 32 million worldwide, including approximately 3 million in the United States. Patients face frequent hospitalizations (1.4 times per year) and a substantial risk of mortality (15%)1,2. HFpEF is characterized by normal left ventricular ejection fraction despite clinical signs of heart failure, making its diagnosis and treatment particularly difficult2. Understanding the pathophysiology of HFpEF presents several key challenges due to its complex and multifactorial nature. HFpEF encompasses a diverse range of clinical phenotypes, complicating the identification of specific pathophysiological mechanisms. The pathophysiology involves intricate interactions among comorbidities such as obesity, diabetes, and hypertension, alongside myocardial and systemic factors3. Key mechanisms include myocardial fibrosis, endothelial dysfunction, and ventricular-arterial coupling, which are not fully understood4. Currently, diagnosis relies on a combination of echocardiographic parameters and natriuretic peptide assays, often requiring additional cardiac stress tests5. The lack of standardized diagnostic criteria contributes to underdiagnosis and poor prognosis3,5.

The complexity of the syndrome continues to hinder the development of evidence-based treatments, highlighting the need for suitable animal models, which allow reductionist and multifactorial studies to model the pathophysiology and test interventions. Careful characterization of animal models is required to ensure they mimic relevant aspects of pathophysiology accurately. To comprehensively assess myocardial remodeling in clinically relevant HFpEF mouse models, we conducted longitudinal studies using non-invasive imaging techniques. This included ultrasound Doppler imaging to evaluate diastolic function and non-contrast cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) to assess functional, anatomical, and perfusion changes in the heart. Cardiac MRI enables non-invasive, longitudinal assessment of various cardiac parameters in rodents with good reproducibility6,7,8. Unlike traditional methods that focus primarily on the left ventricle (LV), cardiac MRI can assess function of both ventricles and atria in detail, providing a holistic view of cardiac function. This comprehensive approach enables robust assessment of key HFpEF phenotypes, including ejection fraction, ventricular mass, wall thickness, myocardial response to beta adrenergic stimulation, and diastolic function.

However, two major bottlenecks restrict the efficiency and consistency of small animal cardiac MRI in preclinical research. First, conventional cine MRI protocols, such as the fast low angle shot (FLASH) sequence9, can be slow, limiting available scan time required for a more comprehensive assessment (stress tests, perfusion imaging, …). To overcome this, we optimized our preclinical cardiac MRI protocol for faster acquisition, comparing four sequences—prospectively gated segmented FLASH without (SF) or with 40% partial Fourier acceleration (SF40), retrospectively in-slice navigator gated FLASH acquisitions (IntraGate, IG)7, and prospectively gated multiband FLASH (MB).

Second, the analysis and quantification of cardiac MRI images is often time-consuming using manual or semi-automated segmentation10,11,12. Although human readers can be very consistent with low intra-reader variability, the delineation of LV contours is significantly influenced by reader experience and results in inter-reader variability13. This variability is even more pronounced for the right ventricle (RV), particularly in measuring volumes (EDV, ESV) and mass, due to its complex trabeculations and geometry. These factors underscore the critical need for fully automated analysis tools that can standardize and accelerate the processing of rodent cardiac MRI data. While convolutional neural networks (CNNs) have shown promise in improving cardiac segmentation in human MRI14, their application to rodent datasets remains limited. Three recent studies demonstrated machine learning-based cardiac segmentation in mice. However, these studies used small numbers of animals (n = 6, n = 6, n = 21) relying on leave-one-out cross validation approaches, which limits the ability to assess their performance on new data15,16,17.

To overcome these limitations, we have developed a deep learning-based approach for fully automated segmentation and quantification of cardiac function in mice. Our method utilizes a CNN architecture to efficiently and reproducibly assess a comprehensive range of parameters, including LV volumes, ejection fraction, stroke volume, myocardial mass, wall thickness, and right ventricular (RV) volumes and ejection fraction and left atrial (LA) surface area. To enable fast and comprehensive cardiac exams, we optimized a contrast-agent-free preclinical cardiac MRI protocol for fast acquisition, incorporating dobutamine stress tests and cine-Arterial Spin Labeling (ASL) for myocardial perfusion assessment. Data acquisition and analysis approaches were validated in mouse models of HFpEF, demonstrating strong correlations between automated and manual analyses and highlighting the accuracy and robustness of our combined acquisition and analysis approach for detecting subtle alterations in cardiac function and myocardial perfusion.

Materials and methods

Animals

All experiments adhered to ARRIVE and AAALAC guidelines, complied with relevant state regulations, and received approval from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). The CNN training data included cardiac MRIs from a previous study (62 female and 73 male mice, average weights 28 ± 6 and 33 ± 5 g respectively)18. For the current study, male and female C57BL/6J mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory, including 21 months old healthy female controls (n = 5) with an average body weight of 30 ± 3 g, 25 weeks old diet-induced obese (DIO) male mice (n = 15) with an average body weight of 43 ± 3 g, 12 weeks old healthy control male mice (n = 18) with an average body weight of 32 ± 1 g, and 16 months old male mice (n = 8) with an average body weight of 35 ± 1 g and housed in our facility on a 12:12 light-dark cycle, controlled temperature, and free access to food and water. Mice were housed 3–5 animals per cage. Cages were randomly assigned to experimental groups. No animals were lost during the study or reached human endpoints (Figs. 1 and 2).

Automated cardiac data analysis pipeline based on 3D or 2D convolutional neural networks. (A) Schematic representation of the U-Net model architecture used for 3D short-axis (top) and 2D long-axis (bottom) cine MRI. The network consists of a down-sampling path (encoder) and an up-sampling path (decoder) with skip connections to preserve spatial information. The model was trained and validated on a dataset of 244 manually annotated short-axis stacks and 278 4-chamber view scans. The data was split into roughly 80% for training and 20% for validation. (B) Representative examples of CNN-based segmentation results for the left ventricle (LV), right ventricle (RV) and left atrium (LA) at LV end-diastole (ED) and end-systole (ES). Images showcase the range of segmentation accuracy achieved by the model, with examples of high, median and low Dice coefficients.

Automated versus manual segmentation of cardiac MRI data. (A) Scatterplots demonstrating the correlation between manual segmentations from two observers for various left ventricular (LV) and right ventricular (RV) functional parameters derived from mouse cardiac MRI (n = 26 data sets). Note the lower correlation for LV ejection fraction (EF) and RV EF, highlighting the variability inherent in manual segmentations. (B) and (C) Tables showing the Dice Similarity coefficient (DSC) for automated segmentation of the LV and RV using a convolutional neural network (CNN). The high DSC values (greater than 0.9) indicate excellent agreement between automated segmentation and the ground truth (n = 60 validation data sets). (D) Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) for LV and RV functional parameters, comparing the mean values obtained from two manual observers with those derived from the CNN-based segmentation. The high ICC values demonstrate strong agreement between the automated and manual methods (n = 54 validation data sets). (E) Scatterplots showing the correlation between automatically predicted values and manually annotated values for various cardiac parameters (n = 244/278 data sets). The strong correlations highlight the accuracy and reliability of the automated segmentation approach.

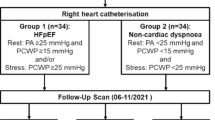

HFpEF models

To investigate the impact of obesity and hypertension on HFpEF development, we utilized two mouse models. A mild HFpEF-like model: diet-induced obesity (DIO, diet starting at 6 weeks of age for 6 months, n = 8) with DOCP-induced hypertension (75 mg/kg at 26 weeks of age, n = 8) (Fig. 3), and a stronger HFpEF-like model (n = 12): middle-aged mice with a high-fat diet (HFD, diet starting at 12 weeks of age for 13 months) and DOCP-induced hypertension (150 mg/kg at 15 months) (Fig. 4). Longitudinal cardiac MRI was performed before and after DOCP administration. Age-matched healthy mice served as controls for the DIO DOCP (12 weeks old mice, n = 6) and HFD DOCP (16 months old mice, n = 8 and 12 weeks old mice, n = 12) cohorts. Only male mice were used for these studies.

Cardiac phenotyping and vascular remodeling in the DIO + DOCP mouse model. (A) Schematic representation of the DIO + DOCP “two-hit” model. Mice were fed a high-fat diet to induce obesity starting at 6 weeks of age. At 26 weeks, they received a single intraperitoneal injection of deoxycorticosterone pivalate (DOCP, 75 mg/kg) to induce hypertension. Cardiac MRI and echocardiography were performed longitudinally at baseline (before DOCP), 7 days, 14 days, and 1 month after DOCP. (B) No significant difference was observed in arterial pressure and assessment of diastolic function using mitral valve (MV) inflow parameters (E/e’ ratio and deceleration velocity) showed no significant differences between the groups at any time point. (C) No significant differences were observed for LV volumes and LV and RV ejection fractions (EF) between the control, DIO, and DIO + DOCP groups at any time point. LV stroke volume (SV) was significantly increased at baseline in the DIO group compared to the control group (p = 0.05). LV mass was consistently elevated on average in the DIO groups before and after DOCP compared to the control group, although this difference did not reach statistical significance (ns, p = 0.25, ANOVA). Dobutamine injections caused a significant increase in heart rate in all groups. However, both LV end-diastolic and end-systolic volumes tended to decrease, resulting in no significant change in cardiac output compared to rest, suggesting a potential impairment in cardiac contractile reserve. (D) Mid-ventricular myocardial blood flow, measured by cine-ASL, was significantly reduced in both DIO and DIO + DOCP groups compared to controls. Histological analysis confirmed the cine-ASL findings. CD31 staining revealed significantly reduced vessel density in the DIO group. DIO + DOCP hearts also exhibited a trend towards reduced vessel density compared to controls (control group n = 6, DIO group n = 7, DIO + DOCP group n = 8 animals).

Cardiac phenotyping and functional assessment in the HFD + DOCP mouse model. (A) Schematic representation of the HFD + DOCP “two-hit” model in middle aged mice. Mice were fed a high-fat diet (60% fat calories) starting at 12 weeks of age for 13 months. At 12 months, they received a single intraperitoneal injection of deoxycorticosterone pivalate (DOCP, 150 mg/kg) to induce hypertension. Cardiac MRI and echocardiography were performed longitudinally at baseline (before DOCP) and 1 month after DOCP. (B) HFD and HFD + DOCP groups exhibited signs of diastolic dysfunction, with a significant increase in the E/e’ ratio and mitral valve deceleration velocity compared to controls, indicating impaired LV filling pressure. (C) Cardiac MRI revealed significant changes in HFD and HFD + DOCP groups compared to controls, including increased stroke volume (SV), reduced ejection fraction (EF), although it remained within the normal range (50–70%), and a significant decrease in mid-ventricular myocardial blood flow, indicating vascular remodeling. Dobutamine stress testing revealed a significant increase in heart rate. However, no changes were observed for both LV end-diastolic and end-systolic volumes. This resulted in no significant change in cardiac output in the HFD and HFD + DOCP groups. (D) Further analysis of myocardial perfusion using cine-ASL showed a significant reduction in the HFD + DOCP group (p = 0.05) and a potential reduction in the HFD group compared to the control group. Histological analysis using CD31 staining showed a trend towards reduced vessel density in HFD + DOCP group compared to the YOUNG, control and HFD groups (HFD group n = 6, HFD + DOCP group n = 12, age matched control n = 8, young control n = 12 mice).

Cardiac MRI setup and acquisition protocol

Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane (3–4% in medical air). Isoflurane concentrations were adjusted between 0.9 and 2% to maintain breathing rates of 100–120 brpm for cine-ASL and 50–80 brpm for cine-MRI. Body temperatures were maintained at 37 ± 0.5 °C inside the MRI bore using a water and air heating system. Imaging was performed with a preclinical 9.4 Tesla Bruker BioSpec (Ettlingen, Germany) using an 86 mm inner diameter transmit volume coil, and a 4-channel cardiac array receive coil. T1 weighted cine sequences in short-axis, 2-and 4-chamber views were acquired for myocardial anatomical and functional assessments.

Optimization of the cardiac MRI protocol

To optimize a fast and efficient cardiac MRI protocol suitable for high-throughput preclinical studies, we conducted pilot studies in five female C57BL/6J mice comparing four short-axis sequences: prospectively gated segmented FLASH without (SF) or with 40% partial Fourier acceleration (SF40), retrospectively in-slice navigator-gated FLASH acquisitions (IntraGate, IG), and prospectively gated multiband FLASH (MB) accelerated with Generalized Autocalibrating Partial Parallel Acquisition (GRAPPA) (Supplementary Fig. S1 and S2 and Supplementary Table 1).

Sequence performance was evaluated based on image quality and acquisition time. Signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), SNR efficiency, and contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR), were calculated offline using Fiji (ImageJ version 2.1.0/1.53c, Switzerland)19 at both end-systole and end-diastole in left ventricular apical and mid-ventricular slices. SNR was calculated as the ratio of the mean signal intensity in the region of interest (ROI; LV blood or myocardium) to the standard deviation of the signal in a background ROI (outside the mouse). SNR efficiency was calculated by normalizing SNR by the square root of the acquisition time to account for the difference in acquisition time. This allowed for a more direct comparison of the signal-generating capabilities of different sequences, independent of their scan length. CNR was calculated as the absolute difference between the mean signal intensities of two ROIs (LV blood vs. myocardium, or myocardium vs. surrounding organs such as lung, chest, or liver), divided by the standard deviation of the signal in the background ROI. CNR values were not corrected for total acquisition time.

The IG sequence, despite yielding the highest SNR efficiency and CNR, was rejected due to its significantly longer acquisition time (15 ± 0.7 min), which is impractical for anesthetized rodents in a multi-modality protocol. The MB and IG sequences were also suboptimal due to larger SNR variation and the presence of flow artifacts within the LV cavity (Supplementary Fig. S1 and S2). While SF showed a marginally better raw CNR than SF40, its scan time was 29% longer. Considering the balance between image quality sufficient for CNN segmentation and the necessity of minimizing anesthesia time for high-throughput studies, the SF40 sequence was selected for cine imaging (Supplementary Fig. S1). This sequence allowed for acquisition of a complete short-axis stack in approximately 7–8 min with the following parameters: TE = 1.8 ms, TR = 4.5-6 ms, flip angle = 15°, slice thickness = 0.8 mm, FOV = 24 × 24 mm2, matrix size = 192 × 192, 20 frames, 12 slices to cover the heart. The chosen in-plane resolution of approximately 125 × 125 μm represented a necessary compromise to acquire comprehensive cardiac coverage within an acceptable duration while maintaining sufficient image quality for reliable segmentation. Following baseline scans, dobutamine stress tests were performed. Five to eight minutes after 1.5 mg/kg bolus injections of dobutamine, short axis stacks were re-acquired (6–8 min) (Supplementary Table 1).

Cine-arterial spin labeling (cine-ASL)

Myocardial perfusion mapping was performed at the beginning of the imaging session after scout and long-axis views had been acquired. Cine-ASL scans were performed using a previously published sequence20 with the following parameters: TR/TE = 6.6/1.7 ms, FA = 8°, FOV = 25 × 25 mm, matrix size = 128 × 128, slice thickness = 1 mm, temporal resolution within one cardiac cycle = 6.6 ms, 25 averaged cine blocks for both tag and control images. Throughout the ASL measurements, a two-lead electrode was used to detect ECG signals from the mouse heart. The ECG trace was monitored with a dedicated module for small animals (SA Instruments Inc., New York). Image acquisition was gated upon detection of the ECG R-waves.

Manual segmentation for deep learning model development

Table 1 summarizes the eight cardiac MRI studies used for training, validation or testing our model. Left ventricle at rest and under dobutamine stress, right ventricle and left atrium were manually segmented using Segment (version 4.0 R12067b, Medviso AB, Sweden) and ITK-SNAP (version 4.2.0, University of Pennsylvania, US) respectively by three trained observers. Annotators were blinded to experimental group assignment. Manual segmentation involved contouring LV endocardial and epicardial borders, RV endocardial borders, and LV atrial blood pool at end-diastole (ED) and end-systole (ES) for all slices containing relevant structures, requiring 40 to 50 min per dataset (Fig. 1). 244 short-axis stacks were manually annotated by two observers, and 278 4-chamber view scans were annotated by a third observer (Table 1). Additionally, to quantify inter-observer variability for manual segmentations, two observers analyzed the same data set (27 short axis stacks). The resulting segmentations were then compared to assess the consistency between the two observers and automated segmentations (Fig. 2).

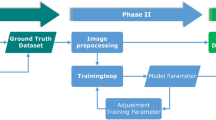

Deep learning based cardiac segmentation

A deep learning model was trained on manual annotations of two timeframes (ED and ES) from short-axis stacks or long-axis slices. Inference was performed on all frames of the input data. The annotated classes varied per modality as follows. Short axis: LV blood, LV myocardium and RV blood. LV wall thickness was estimated as a post-processing step based on the myocardial segmentation, with measurements taken in subregions defined by the 17-myocardial wall segments AHA model. To ensure accurate wall thickness measurements, LV apical slices were excluded from the analysis if the blood pool was not clearly discernible at end-systole (Supplementary Fig. S3). Long-axis 4-chamber: LV blood, LV myocardium, RV blood, LA blood. Long-axis 2-chamber: LV blood, LV myocardium, LA blood (Figs. 1 and 2). For each modality, we split the labeled scans into roughly 80% train and 20% validation sets (only including scans that were taken at rest, without dobutamine stress) (Table 1).

Model architecture

All segmentation models utilize a convolutional neural network (CNN) based U-Net architecture21 consisting of a series of down-sampling layers followed by up-sampling layers with skip connections (Fig. 1A). The short-axis model performs 3D volumetric segmentation of each timeframe and consists of 3 down-sample layers (with 32, 64, 128 output channels respectively), a bottleneck layer (256 channels), and 3 up-sample layers (128, 64, 32 channels). The long-axis models perform 2D segmentation of each timeframe and contain 4 down-sample layers (with 64, 128, 256, 512 output channels), a bottleneck (512 channels), and 4 up-sample layers (512, 256, 128, 64 channels). Each layer contains a pair of convolution-normalization-ReLU blocks. Additionally, down-sample layers are followed by max pooling, and up-sample layers are preceded by transposed convolution-normalization-ReLU blocks plus skip connections (channel-wise concatenation with the outputs of the corresponding down-sample layer). For the short-axis model, we use 3D convolutions and instance normalization (due to low batch size). For the long-axis models, we use 2D convolutions and batch normalization. All models have a final layer consisting of multiple “heads”, one per annotation class, with each head consisting of a 1 × 1 convolution + softmax to predict the probability of each voxel corresponding to the specified class. All models were trained using the Adam optimizer to minimize Dice loss. For the short axis model, we used a batch size of 4 and initial learning rate 0.001 which decayed by a factor of 0.96 per epoch. For the long axis models, we use a batch size of 16 and initial learning rate 0.004 which decays by a factor of 0.99 per epoch. All models were trained for 100 epochs. Data augmentation includes flips, rotations, and Gaussian noise. We selected the checkpoint with the lowest validation loss for subsequent evaluation. Figure 1B provides representative examples of the CNN-based segmentation results at LV end-diastole and end-systole. The images highlight the range of segmentation accuracy achieved by the CNN. The examples shown illustrate cases with high Dice coefficients, indicating accurate segmentation, and cases with low Dice coefficients, where the automated segmentation deviates from the manual annotations.

Myocardial perfusion quantification

Cine-arterial spin labeling (ASL) images were reconstructed and analyzed using custom Python-based software20,22. Quantitative myocardial perfusion maps were created, and myocardial blood flow (MBF) was reported as the average along a manually drawn polygon indicating the middle of the myocardial wall in the selected short axis slice. The reliability of the cine-ASL method was assessed by repeated measurements in healthy mice on different days and MBF quantification was performed blinded to experimental group assignment. This analysis demonstrated good technical reproducibility, showing a strong correlation (correlation coefficient, 0.86) and good agreement (bias of 10.4 ±1.6% and ICC 0.86) between repeated measures (Supplementary Fig. S4 and S5).

Ultrasound

All echocardiographic images were acquired using a high-frequency ultrasound system (Vevo 3100, Visualsonics, FujiFilm SonoSite, Bothell, WA, USA) equipped with an MX550D transducer, which provides a center frequency of 55 MHz and an axial resolution of 40 μm.

Animal preparation and gating

Mice were anesthetized via continuous inhalation of 2% isoflurane mixed with medical air, ensuring maintenance of a stable physiological heart rate (typically 400–500 beats per minute) to minimize anesthetic influence on cardiac function. Body temperature was continuously monitored via a rectal probe and maintained at 36 ± 0.6 °C using a heated platform. The chest hair was removed, and pre-warmed acoustic coupling gel was applied to ensure high-quality imaging.

Image acquisition and diastolic parameters

Echocardiography was performed at different experimental time points by a single, blinded observer, with diastolic function assessed from the apical 4-chamber view. Pulsed Wave (PW) Doppler was used by placing the sample gate into the inflow jet (visualized by color doppler) to record mitral valve inflow velocities. Key PW parameters measured included the E-wave (Peak early diastolic filling velocity), the A-wave (Peak late diastolic filling velocity corresponding to atrial contraction), the E/A ratio, and the Mitral Valve Deceleration peak velocity. Subsequently, Tissue Doppler Imaging was performed by placing the sample gate at the septal corner of the mitral annulus to measure the peak early diastolic mitral annular velocity (e’). These values were combined to calculate the E/e’ ratio, which serves as a non-invasive index of left ventricular filling pressure.

Data analysis

Doppler imaging-derived parameters were measured manually using VevoLab software (version 2) and averaged over three consecutive cardiac cycles. All measurements were performed by a single investigator who remained blinded to the experimental group assignment to minimize bias.

Blood pressure

Noninvasive blood pressure measurements using a tail-cuff technique were performed longitudinally prior to DOCP injection and after DOCP injection at different timepoints to assess blood pressure (MC4000, Hatteras Instruments, Grantsboro, NC, USA) during disease progression.

Sample preparation

Animals were euthanized by exsanguination while under terminal isoflurane anesthesia. A catheter was inserted into the left ventricle, and animals were perfused with a 0.1 mol/L potassium chloride (Sigma Aldrich) solution in PBS. Hearts were excised and fixed for 24 h in 10% formalin, then transferred to 70% EtOH and embedded in paraffin.

Hearts were cut into 4 μm thick axial sections using an automated rotary microtome (HistoCore Autocut, Leica, Germany). For each heart, sections were collected at two anatomic locations corresponding to the LV apical and basal regions.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

All the stainings were performed by a histopathology lab (Histowiz Inc. NY, USA), using the Leica Bond RX automated stainer (Leica Microsystems) using a Standard Operating Procedure and fully automated workflow. Slides were dewaxed using xylene and alcohol based dewaxing solutions. Epitope retrieval was performed by heat-induced epitope retrieval (HIER) of the formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue using citrate-based pH 6 solution (#AR9961, Leica Microsystems) for 20 min at 95 °C. Tissues were first incubated with peroxide block buffer (Leica Microsystems), followed by incubation with the rabbit anti-CD31 antibody (#CST77699, Cell Signaling Technology, MA, USA) at 1:100 dilution for 30 min, followed by DAB rabbit secondary reagents: polymer, DAB refine and hematoxylin (Bond Polymer Refine Detection Kit, Leica Microsystems) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Slides were dried, coverslipped (TissueTek-Prisma Coverslipper) and visualized using a Leica Aperio AT2 slide scanner (Leica Microsystems) at 40x magnification.

Staining quantification and analysis

The HALO Image Analysis Platform with HALO AI (version 4.1.5944 ; Indica Labs, Inc.) was used to quantify vessel density by training the HALO AI Membrane Segmentation architecture on CD31-immunostained tissue sections to identify and segment CD31-positive vascular objects. The number of segmented objects was then divided by the tissue surface area (mm2) of the left ventricle in each IHC section to calculate vessel density (Supplementary Fig. S9).

Statistical analysis

For each experimental series, data are presented as means ± standard deviation. For data from longitudinal follow-up of in vivo imaging, each animal is its own control. Statistical analysis was performed with GraphPad Prism (version 10.4.1, GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Statistical significance (p < 0.05) for each variable was estimated by one-way or two-way ANOVA when group variances were equal (Bartlett test); if not the non-parametric Kruskall-Wallis test, and the Holm multiple comparisons test were used to execute simultaneous group comparisons. To assess the performance of the CNN-based cardiac MRI segmentation, its output was compared against the manual annotation. Pearson’s correlation coefficient and Bland-Altman analysis were performed to evaluate the agreement and bias between the two methods and inter-observer variabilities. Finally, Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC, model 3, 1) was used to quantify the inter-method agreement and inter-observer variabilities. ICC (model 1, 1) was employed to assess intra-observer agreement for test-retest cine ASL analysis in the healthy cohort.

Results

Deep learning-based algorithms provide consistent and reliable cardiac function measurements

In our study, we observed good correlations and agreement between two experienced observers for LV functional parameters, such as end-diastolic and end-systolic volumes (correlation coefficients of 0.94 and 0.91, bias of − 5.1% and − 16%, respectively, and Intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.96 and 0.95, respectively) (Fig. 2A and Supplementary Fig. S4). However, the correlation was lower for LV ejection fraction (EF) (0.79, bias of 5.1% and ICC of 0.89), a key parameter for differentiating between heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) (Fig. 2A and Supplementary Fig. S4). This lower correlation highlights the potential for variability in this crucial measurement when using manual segmentation. The correlation was even weaker for RV EF (0.63 and bias of 1.3% and ICC of 0.62) (Fig. 2A and Supplementary Fig. S4). In contrast, our CNN-based automated segmentation demonstrated excellent performance, achieving a mean Dice coefficient greater than 0.9 for both short-axis and 4-chamber view scans (Fig. 2B, C). ICC analysis further confirmed the high agreement between the CNN-derived values and the mean values obtained from the two manual observers, with ICC values exceeding 0.95 for LV functional parameters and 0.82 for RV EF (Fig. 2D). Furthermore, we observed strong correlations between the automatically predicted and manually annotated values for scans at rest, with correlation coefficients greater than 0.96 for LV end-diastolic volume (EDV), LV end-systolic volume (ESV), LV stroke volume (SV), LV EF, and LV mass (Fig. 2E). Bland-Altman analysis showed minimal biases of -0.9%, -5.6%, 2% for LV EDV, LV ESV, LV EF and LV mass respectively (Supplementary Fig. S5). While the correlation for LA area segmented from 4-chamber views was slightly lower (0.79), it still indicated good agreement (Fig 2E).

Comprehensive cardiac assessment revealed diastolic and perfusion dysfunctions in HFpEF mouse models

In the DIO DOCP model (Fig. 3A), LV stroke volume was significantly increased at baseline before DOCP administration compared to age matched control (p = 0.05) (Fig. 3B and Supplementary Fig. S6). However, no significant changes were observed for mean blood pressure, mitral valve inflow-derived parameters (E/e’ ratio and deceleration velocity), or LV and RV ejection fractions between the groups and time points, suggesting relatively normal cardiac function overall (Fig. 3B and C). Dobutamine stress tests did not reveal any unexpected changes in LV function in response to increased workload (Fig. 3C). While no significant changes in LV mass were observed between the groups at different time points, it is important to highlight that LV mass was consistently elevated on average in the DIO groups before and after DOCP compared to age matched control (control: 109 ± 11 mg vs. DIO: 124 ± 10 mg at baseline, 123 ± 14 mg at 7 days post-DOCP, 124 ± 15 mg at 14 days post-DOCP, and 125 ± 14 mg at 1 month post-DOCP) (Fig. 3C). Furthermore, we observed significant impairment in myocardial perfusion in DIO mice. Mid-ventricular myocardial blood flow (MBF), as assessed by cine-ASL, was markedly reduced in both the DIO (p = 0.02) and DIO + DOCP (p = 0.03) groups compared to control. This reduction was independent of DOCP treatment, suggesting that diet-induced obesity alone leads to significant vascular remodeling and impaired perfusion. Histological analysis using CD31 staining corroborated these findings. Vessel density was reduced in both the DIO (-7.2%, p = 0.03) and DIO + DOCP (non-significant reduction of -5.4%, p = 0.10) groups compared to control (Fig. 3D). These results collectively indicate that obesity-related microvascular changes are a prominent feature in this preclinical HFpEF model. Our observations highlight the technical sensitivity of this approach for detecting early microvascular changes associated with obesity, even in the absence of overt changes in cardiac function. Inclusion of perfusion imaging may enable identifying subtle alterations preceding the development of HFpEF.

In the HFD DOCP model (Fig. 4A and Supplementary Fig. S7), we observed left ventricular functional impairments attributable to HFD (0 group), which was further exacerbated by DOCP treatment (1mo group), replicating some key HFpEF phenotypes. Specifically, a significant increase in the E/e’ ratio (p = 0.04) and mitral valve deceleration velocity (p = 0.04) was observed in the HFD + DOCP group compared to controls one month after DOCP administration, indicating LV diastolic dysfunction (Fig. 4B). This observation is consistent with a significant increase in left atrial (LA) area observed in both HFD (p = 0.01) and HFD + DOCP (p = 0.001) groups compared to controls. LA enlargement is a key marker for LV diastolic dysfunction (Fig. 4C). Although LV ejection fraction was significantly reduced in the HFD + DOCP group compared to control and HFD groups, it remained above 50%, within the non-pathological range (Fig. 4C). LV stroke volume was significantly increased in the HFD group compared to control (p = 0.04) and tended to remain elevated in the HFD + DOCP group (control: 37.6 ± 6.6 µl vs. HFD + DOCP: 45.5 ± 7.9 µl). Similarly, LV end-diastolic volume was significantly increased in the HFD + DOCP group (p = 0.01) and potentially increased in the HFD group compared to controls (control: 59 ± 8.9 µl vs. HFD: 71 ± 13.5 µl). LV mass was larger albeit not statistically significant in both HFD and HFD + DOCP groups compared to control (control: 120.4 ± 7.9 mg vs. HFD: 132.4 ± 15.7 mg, p = 0.07 and HFD + DOCP: 133.8 ± 9.5 mg, p = 0.06). However, further analysis (Supplementary Fig. S7) shows that these increases in LV volumes and mass correlated with higher body weight of obese mice. Dobutamine stress testing revealed a significant increase in heart rate and LV ejection fraction (Fig. 4C). However, no significant changes were observed for both LV end-diastolic and end-systolic volumes in HFD and HFD + DOCP groups compared to the control group under dobutamine stress. This resulted in non-significant changes in cardiac output (Fig. 4C). On the other hand, mid-ventricular MBF was significantly reduced in the HFD + DOCP group (p = 0.05) compared to the control group. The HFD group also showed a reduction in MBF compared to the control group (control: 5.0 ± 1.3 ml/g/min vs. HFD: 3.5 ± 1.2 ml/g/min, p = 0.15), although this reduction was not statistically significant. These findings suggest impaired myocardial perfusion in both HFD and HFD + DOCP groups (Fig. 4D). Histological analysis using CD31 staining revealed a trend towards reduced vessel density in the HFD + DOCP group compared to the young, control and HFD groups (non-significant reductions of 4.9% (p = 0.08), 3.7% (p = 0.37), and 2.6% (p = 0.73), respectively).

Discussion

Cardiac MRI in mice presents unique challenges due to their small heart size (5–6 mm LV diameter), high heart rates (500–700 bpm), and rapid breathing rates (60–160 brpm)9,23. These constraints can lead to motion artifacts, low signal to noise ratios, and partial volume effects, particularly in apical segments, affecting the accuracy of image analysis24. To counteract these limitations, major improvements in MRI methodology and instrumentation have been achieved, including rapidly switching high-performance gradient systems, high magnetic field strength (> 7 T), cardiac receive array coils, and fast acquisition sequences25,26. These improvements enable high resolution cardiac MRI in mice. However, cardiac imaging protocols tend to be slow typically requiring 15–25 min for a short axis cine stack limiting throughput and the ability to add additional sequences with different contrast mechanisms. We therefore optimized acquisition protocols for image quality and acquisition efficiency. A gradient echo sequence with flow compensation and 40% partial Fourier acceleration was selected, enabling a comprehensive short-axis assessment in approximately seven minutes. The optimization was executed using readily accessible methodology; however, alternative implementations utilizing sequences such as compressed sensing, out-of-slice navigators, or radial scanning with shortened echo times could potentially outperform our selected sequence. The practical adoption of these advanced sequences depends on their widespread system integration and verification of their efficacy in achieving optimal scan duration for full short-axis coverage of the ventricles. On the other hand, optimized protocols for cardiac MRI in rodents have been reported previously, but they often had lower spatial and temporal resolution and led to much longer acquisition times8,27,28. Reduced scan times allowed us to incorporate additional sequences for a more thorough assessment of heart function. These included a dobutamine stress test to evaluate cardiac reserve, and a cine-arterial spin labeling (cine-ASL) sequence to assess myocardial perfusion—a critical parameter in evaluating coronary microvascular function. This comprehensive approach, combining high-quality anatomical and functional imaging with perfusion mapping, provides a comprehensive characterization of cardiac physiology in mouse models of cardiovascular disease, such as HFpEF.

Analyzing mouse cardiac MRI images is challenging due to low signal to noise ratios, difficulties in accurate identification of papillary muscles and valve planes, and the presence of image artifacts29,30. Image analysis can be performed using manual, semi-automatic, or fully automated methods. While manual segmentation is often considered the gold standard, it is time-consuming (30–60 min per data set) and prone to inter-observer variability. This variability stems from differences in observer experience and expertise on how to how to identify valve planes, interpret artifacts and noisy images particularly where the heart is close to the chest muscles13. Consequently, we developed a convolutional neural network (CNN) based on a U-Net architecture for fully automated segmentation of mouse cardiac MRI data. This method was validated on hold-out data sets not used for model training. Sixty short-axis stacks and 54 4-chamber view scans were compared with manual segmentation and demonstrated high accuracy, achieving a mean Dice score of > 0.9. This represents a significant improvement compared to previously published models which reported Dice scores < 0.916,17. Our CNN-based segmentation approach provides fully automated segmentation with reliable delineation of the LV wall and RV cavity, even at LV end-systole, which is a challenging phase for segmentation and motion tracking31. The automated approach offers significant time savings and increased consistency32 enabling more robust and reproducible quantification of cardiac parameters, even under challenging conditions like dobutamine stress testing. This tool has the potential to accelerate preclinical research and enhance the translation of findings from animal models to human studies.

While histology remains the gold standard for assessing myocardial tissue remodeling, the comprehensive and longitudinal functional assessment provided by cardiac MRI is a crucial and complementary component. Although this specific study focused on functional MRI parameters and did not include advanced MRI-based tissue characterization techniques, it is critical to recognize that structural and functional assessments are interdependent. Interpreting the progressive functional changes captured by cardiac MRI and ultrasound-derived diastolic parameters alongside structural histological data allows for a more comprehensive understanding of early stages of the cardiac remodeling continuum during obesity and in two different HFpEF-like mouse models, DIO DOCP and HFD DOCP. Utilizing advanced cardiac MRI techniques, coupled with a novel CNN-based automated segmentation approach, we were able to detect subtle alterations in both cardiac function and myocardial perfusion that may precede overt HFpEF, especially in the DIO DOCP model. Indeed, in the DIO DOCP model, where diet-induced obesity for 6 months was combined with hypertension, we observed early signs of microvascular dysfunction, characterized by reduced myocardial blood flow and decreased vessel density. Changes in myocardial perfusion were evident even in the absence of significant alterations in cardiac function parameters, such as ejection fraction and diastolic function’s parameters (E/e’ ratio, MV deceleration peak velocity and LA maximum surface area). These results, particularly the observed reduction in myocardial perfusion, align with clinical findings in patients with obesity, diabetes, and/or metabolic syndrome33,34,35, highlighting the technical sensitivity of our approach in detecting early vascular abnormalities associated with obesity, a key risk factor for HFpEF36. In the HFD DOCP model, which combines long-term high-fat diet exposure with hypertension in middle-aged mice, we observed a pronounced HFpEF phenotype. This functional impairment included clear evidence of LV diastolic dysfunction, characterized by a significant increase in the E/e’ ratio and mitral valve deceleration velocities on Doppler imaging, along with consistent LA enlargement detected by cardiac MRI. These findings align with reports emphasizing diastolic dysfunction and LA remodeling as key features of HFpEF37. While LV volumes were notably increased in these groups, suggesting an increased preload, further analysis indicates that these changes are largely secondary to the higher body weight and blood volume associated with obesity rather than reflecting intrinsic LV mass alterations. Importantly, our study showed that these alterations were accompanied by significant microvascular changes, including HFD and DOCP-induced reduced myocardial perfusion, further supporting the role of obesity and hypertension in driving the early stages of HFpEF38. This finding was corroborated by histological analysis, which demonstrated a trend toward a decrease in myocardial vessel density in the HFD + DOCP group. Our results suggest a complex interplay of factors in HFpEF, where HFD and DOCP contribute to impaired myocardial perfusion, potentially induced by the age-related microvascular rarefaction.

Our findings emphasize the importance of comprehensive cardiac assessment, including perfusion imaging and automated image analysis in preclinical HFpEF research. By identifying subtle changes that may precede overt disease, this approach can contribute to a deeper understanding of disease mechanisms and facilitate the development of novel therapeutic strategies.

Study limitations

Our study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. While CNN-based segmentations demonstrated robust performance on internal data, deep learning models are inherently sensitive to variations in input. Specifically, the generalizability of our segmentation models may be limited by a lack of standardization in cardiac MRI protocols and imaging parameters across different institutions and various disease states. We acknowledge that our final choice of the SF40 sequence over the theoretically more SNR/CNR-efficient IntraGate (IG) sequence was a practical compromise driven by the stringent anesthesia time constraints required for comprehensive longitudinal assessment. This means that the chosen protocol is optimal for our specific high-throughput setup but may not represent a universal standard. Furthermore, to maintain accessibility and ease of transfer, we did not pursue advanced acceleration methods like Compressed Sensing (CS) reconstruction or radial k-space trajectories, which could mitigate the long scan time or flow artifacts of other sequences. While the inclusion of cine-Arterial Spin Labeling (ASL) for myocardial blood flow (MBF) was critical, the quantification of MBF was not integrated into the fully automated deep learning pipeline. Instead, MBF analysis relied on a manual step (averaging along a manually drawn polygon in the myocardial wall), which, while reproducible, requires user interaction and limits the complete end-to-end automation of the comprehensive exam. Future work will focus on developing a dedicated CNN tool for robust ASL quantification. Our cardiac MRI protocol did not include gadolinium-based contrast agent administration which is required for extracellular volume fraction (ECV) quantification. ECV is a good marker for intestinal fibrosis, a critical pathological aspect of many heart failure models. Future studies should incorporate these sequences for a more comprehensive understanding of tissue remodeling. Additionally, due to the distinctive anatomy of the rodent heart, we reported Left Atrial (LA) area as a useful proxy for atrial size, instead of the LA volume. The small dimensions and complex morphology of the rodent LA, characterized by a disproportionately large and convoluted LA appendage, present significant challenges for accurate volumetric tracing and calculation from standard cardiac MRI slices. While our mouse models recapitulate key features of HFpEF, they do not fully capture the complexity of the human disease. Furthermore, additional studies are required to clarify the relationship between myocardial vascular remodeling and impaired myocardial perfusion.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates the power of combining fast cardiac MRI protocols with CNN-based automated analysis pipelines for comprehensive assessment of cardiac function in preclinical HFpEF models. Our automated approach enables efficient and reproducible quantification of a wide range of cardiac parameters, including left and right ventricular function and left atrial cross-sectional area.

By incorporating advanced imaging methods like cine-ASL and dobutamine stress testing, we detected subtle cardiac changes, including microvascular changes and diastolic dysfunction, in two different HFpEF mouse models. These findings highlight the importance of comprehensive cardiac assessment in preclinical research and underscore the potential of this approach for advancing our understanding of cardiovascular disease mechanisms and phenotypes and facilitating the development of novel therapeutic strategies.

Data availability

CNN-based analysis pipelines are available on GitHub: https://github.com/calico/mouse_cardiac_mri_segmentation.

Datasets generated and utilized for this manuscript are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Tsao, C. W. et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2022 update: A report from the American heart association. Circulation 145, e153–e639 (2022).

Redfield, M. M. & Borlaug, B. A. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: A review. JAMA 329, 827–838 (2023).

Tah, S. et al. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: An evolving understanding. Cureus https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.46152 (2023).

Stoicescu, L., Crişan, D., Morgovan, C., Avram, L. & Ghibu, S. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: The pathophysiological mechanisms behind the clinical phenotypes and the therapeutic approach. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25, 794 (2024).

Logeart, D. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: New challenges and new hopes. Presse Médicale. 53, 104185 (2024).

Joubert, M. et al. Test-retest reproducibility of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in healthy mice at 7-Tesla: Effect of anesthetic procedures. Sci. Rep. 7, 6698 (2017).

Zuo, Z. et al. Assessment of longitudinal reproducibility of mice LV function parameters at 11.7 T derived from self-gated CINE MRI. BioMed Res. Int. 2017, 8392952 (2017).

Schneider, J. E., Wiesmann, F., Lygate, C. A. & Neubauer, S. How to perform an accurate assessment of cardiac function in mice using high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging. J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. Off J. Soc. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 8, 693–701 (2006).

Li, H. et al. Technical aspects of in vivo small animal CMR imaging. Front. Phys. 8, 183 (2020).

Beerbaum, P. et al. Cardiac function by MRI in congenital heart disease: Impact of consensus training on interinstitutional variance. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 30, 956–966 (2009).

Hautvast, G. L. T. F. et al. Accurate computer-aided quantification of left ventricular parameters: Experience in 1555 cardiac magnetic resonance studies from the Framingham heart study. Magn. Reson. Med. 67, 1478–1486 (2012).

Axel, L. & Sodickson, D. K. The need for speed: Accelerating CMR imaging assessment of cardiac Function∗. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging. 7, 893–895 (2014).

Petitjean, C. & Dacher, J. N. A review of segmentation methods in short axis cardiac MR images. Med. Image Anal. 15, 169–184 (2011).

Chen, C. et al. Deep learning for cardiac image segmentation: A review. Front Cardiovasc. Med 7, 25 (2020).

Hammouda, K. et al. A new framework for performing cardiac strain analysis from cine MRI imaging in mice. Sci. Rep. 10, 7725 (2020).

Zufiria, B. et al. Fully automatic cardiac segmentation and quantification for pulmonary hypertension analysis using mice cine Mr images. In 2021 IEEE 18th Int. Symp. Biomedical Imaging (ISBI). 1411–1415 https://doi.org/10.1109/ISBI48211.2021.9433855 (2021).

Xu, H., Schneider, J. E., Young, A. A., & Grau, V. Fully automated segmentation of the left ventricle in small animalcardiac mri. MIDL 2018 Conference. (2018).

Can, E. et al. Naked mole-rats maintain cardiac function and body composition well into their fourth decade of life. GeroScience 44, 731–746 (2022).

Schindelin, J. et al. Fiji: An open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods. 9, 676–682 (2012).

Troalen, T., Capron, T., Cozzone, P. J., Bernard, M. & Kober, F. Cine-ASL: A steady-pulsed arterial spin labeling method for myocardial perfusion mapping in mice. Part I. Experimental study. Magn. Reson. Med. 70, 1389–1398 (2013).

Ronneberger, O., Fischer, P. & Brox, T. U-Net Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. in Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention – MICCAI 2015 (eds Navab, N., Hornegger, J., Wells, W. M. & Frangi, A. F.) 234–241 (Springer, 2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-24574-4_28.

Kober, F. Rodent in vivo myocardial perfusion MRI package. (Aix Marseille Univ, CNRS, CRMBM-CEMEREM (UMR 7339), (2022)).

Wessels, A. & Sedmera, D. Developmental anatomy of the heart: A tale of mice and man. Physiol. Genomics. 15, 165–176 (2003).

Hamilton, J. I., Jiang, Y., Eck, B., Griswold, M. & Seiberlich, N. Cardiac cine magnetic resonance fingerprinting for combined ejection fraction, T1 and T2 quantification. NMR Biomed. 33, e4323 (2020).

Hiba, B., Richard, N., Thibault, H. & Janier, M. Cardiac and respiratory self-gated cine MRI in the mouse: Comparison between radial and rectilinear techniques at 7T. Magn. Reson. Med. 58, 745–753 (2007).

Chen, X., Salerno, M., Epstein, F. H., & Meyer, C. H. Accelerated multi-TI spiral MRI using compressed sensing withtemporal constraints. Proc. Intl. Soc. Mag. Reson. Med., 19, 4369, (2011).

Daal, M. R. R. et al. Quantification of mouse heart left ventricular function, myocardial strain, and hemodynamic forces by cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging. J. Vis. Exp. JoVE. https://doi.org/10.3791/62595 (2021).

van Nierop, B. J. et al. Phenotyping of left and right ventricular function in mouse models of compensated hypertrophy and heart failure with cardiac MRI. PLOS ONE. 8, e55424 (2013).

El-Taraboulsi, J., Cabrera, C. P., Roney, C. & Aung, N. Deep neural network architectures for cardiac image segmentation. Artif. Intell. Life Sci. 4, 100083 (2023).

Hassani, C., Saremi, F., Varghese, B. A. & Duddalwar, V. Myocardial radiomics in cardiac MRI. Am. J. Roentgenol. 214, 536–545 (2020).

Gondova, A. et al. Convolutional neural networks for automated CMR image segmentation in rats with myocardial infarcts. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.12.01.405969 (2020).

Chen, D. et al. Deep neural network for cardiac magnetic resonance image segmentation. J. Imaging. 8, 149 (2022).

Carli, M. F. D. et al. Coronary circulatory function in patients with the metabolic syndrome. J. Nucl. Med. 52, 1369–1377 (2011).

Murthy, V. L. et al. Association between coronary vascular dysfunction and cardiac mortality in patients with and without diabetes mellitus. Circulation 126, 1858–1868 (2012).

Bajaj, N. S. et al. Coronary microvascular dysfunction and cardiovascular risk in obese patients. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 72, 707–717 (2018).

Ramirez, M. F. et al. Obesity-Related biomarkers are associated with exercise intolerance and HFpEF. Circ. Heart Fail. 16, e010618 (2023).

Deng, Y. et al. Targeting mitochondria-inflammation circuit by β-hydroxybutyrate mitigates HFpEF. Circ. Res. 128, 232–245 (2021).

Borlaug, B. A. et al. Obesity and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: New insights and pathophysiological targets. Cardiovasc. Res. 118, 3434–3450 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the histology teams at Calico and HistoWiz for their support.

Funding

This study was funded by Calico Life Sciences LLC.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.Y: conception, study design, data acquisition and analysis, manuscript writing. M.S: machine learning model development, editing and reviewing. B.M.N: Conception, study design, editing and reviewing. J.L and A.L: histological data analysis, reviewing. F.S: MRI methods development, reviewing and editing. F.K: MRI methods development, perfusion data analysis methods development, editing and reviewing. J.R: supervision, conception, study design, reviewing and editing. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Thulaciga Yoganathan, Matt Sooknah, Baby Martin-McNulty, James Lee, Florian Schmid, Austin Lefebvre, and Johannes Riegler are employees of Calico Life Sciences LLC.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yoganathan, T., Sooknah, M., Martin-McNulty, B. et al. Automated cardiac MRI analysis for robust profiling of heart failure models in mice. Sci Rep 16, 1158 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30810-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30810-y