Abstract

To reveal the mechanisms governing the temperature-dependent electrical behavior of coal-bearing surrounding rocks, a multi-physics coupling model was established and combined with experimental data to systematically analyze the evolution of resistivity and dielectric properties with temperature. The results show that resistivity undergoes a three-stage transformation: it first increases due to microcrack development and pore-water evaporation, then decreases sharply as carriers are thermally activated, and further declines at higher temperatures. Dielectric properties are markedly enhanced beyond a critical threshold, accompanied by a relaxation peak that indicates interfacial and ionic polarization dominate under thermal activation. A pronounced frequency dispersion is also observed, with polarization processes being suppressed at higher frequencies. These findings demonstrate that temperature strongly regulates carrier mobility and polarization capacity, thereby exerting a fundamental influence on the resistivity and dielectric response of rocks. This work provides theoretical support and practical reference for temperature correction in deep resource geophysical exploration, real-time monitoring of thermal damage in mines, and stability assessment of rocks under high-temperature conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With rising global energy demand and the depletion of shallow resources, developing deep coal resources and exploring dry-hot rock geothermal energy have become strategic priorities. As a key component of the mine host rock system, the temperature-induced variation in overburden electrical properties (resistivity and dielectric constant) directly affects EM exploration accuracy and rock thermal-damage assessment1,2. These properties are further controlled by water content, porosity, and mineralogy3. Overburden resistivity is typically high but sensitive to moisture and mineral composition, whereas the dielectric constant increases with water saturation and certain mineral constituents4. For dry-hot rocks in deep geothermal applications, elucidating the temperature dependence and mechanisms of electrical responses is therefore essential5. However, prior work has largely emphasized ambient, static characterization and lacks a systematic understanding under multi-physics coupling.

In studying temperature effects on rock resistivity, Ren6 developed a temperature-coupled resistivity test system and found that temperature-induced resistivity changes are more pronounced at low pressure. Hersir7 analyzed rock resistivity structures and high-temperature geothermal systems, verifying that when pore-fluid resistivity is < 2Ω·m the pore fluid dominates bulk conductivity; resistivity also correlates with temperature. Zhu8 showed that resistivity first increases and then decreases with temperature using heat-treated coal specimens. Du et al.9 reported that heating alters pore topology and structure. Alonso et al.10 showed that higher temperatures accelerate nuclide migration via enhanced thermal motion, whereas pressure modifies pore structure and permeability, indirectly affecting transport. Chen et al.11 considered temperature magnitude and lattice-bound water. However, many models assume a constant carrier concentration, ignoring high-temperature, lattice-vibration-induced surges, which can cause up to two orders of magnitude error in resistivity prediction.

Recent studies indicate strong frequency dependence in the temperature response of dielectric properties; revealing frequency-temperature coupling during polarization relaxation is a current focus in dielectric physics. Belyanchikov et al.12 studied the dielectric ordering of water molecules in mineral lattices and found that the arrangement of water molecules in the lattice significantly influences the dielectric response. Furthermore, Zheng et al.13 used terahertz time-domain spectroscopy (THz-TDS) to investigate the impact of crystal water content on the dielectric properties of gypsum, and proposed a dielectric constant model based on crystal water content. These studies provide new perspectives on the dielectric behavior of water in minerals. Breeze14 proposed a density functional perturbation theory-based model for predicting the dielectric constant of metal oxides, revealing the impact of lattice vibrations on dielectric losses. Shu and co-authors15 reported that YIG’s dielectric constant and loss tangent exhibit characteristic frequency-dependent patterns linked to crystal structure and electromagnetic properties. Lambert16 showed that lattice geometry (shape, size, porosity) can tune the effective dielectric constant while maintaining a low loss tangent. However, most studies are limited to single-frequency or narrow-temperature tests, leaving a gap in full-temperature (room temperature to ~ 700 °C), multi-band datasets needed to resolve temperature–frequency–polarization coupling. Suman et al.17 reported lower losses with higher room-temperature permittivity and magnetic-field-induced changes in dielectric properties, evidencing magneto-electric coupling. Wang et al.18 showed that strengthened chemical bonding suppresses lattice changes, thereby reducing impacts on dielectric and electrical properties.

Here we construct a resistivity-temperature multi-field coupling model by integrating Archie’s pore-fluid conductivity framework19 with the Arrhenius activation-energy formalism20 and apply it to ten overburden rock types from the Shanxi coalfields. We establish a temperature-dependent polarizability model for the dielectric constant and compile full-temperature-range resistivity and dielectric spectra datasets. By comparing electrical evolution across mineralogies, we clarify how temperature affects electrical parameters via a thermal-stress → microcracking → polarization pathway, and we propose electrical criteria for thermal damage in coal-bearing rocks21. These results provide a theoretical basis for temperature correction in deep-resource electrical exploration and technical parameters for developing real-time mine thermal-damage monitoring systems.

Theoretical study of rock resistivity

Definitions and models of rock resistivity

Resistivity quantifies a material’s opposition to electric current. It depends on intrinsic factors (mineralogy, porosity, saturation) and extrinsic conditions (temperature, pressure).

For a homogeneous, isotropic specimen, resistance follows Ohm’s law: R = ρ · L/A, and σ = 1/ρ, where L is length and A is cross-sectional area.

Archie’s law relates the resistivity of a fluid-saturated rock to the pore-fluid resistivity and porosity and is widely used in petroleum geophysics:

where ρrock is rock resistivity (Ω·m); ρfluid is pore-fluid resistivity (Ω·m); φ is porosity; a is the tortuosity factor; m is the cementation exponent.

The derivation assumes a connected pore network, negligible surface conduction in the matrix, and conductive pore fluid. In this framework, the resistivity ratio primarily reflects tortuosity and pore connectivity.

Temperature effects on rock resistivity

Temperature is a key control on resistivity. Heating changes carrier concentration, mobility, and microstructure (e.g., water evaporation and microcracking), producing non-monotonic trends.

Over broad ranges, temperature dependence can be captured with an Arrhenius-type relation. The Arrhenius equation was originally used to characterize the dependence of chemical reaction rates on temperature, but is also widely used to characterize how the resistivity of a substance changes with temperature.

The Arrhenius relation for resistivity is:

where ρ(T) is the resistivity at a temperature T; ρ0 is resistivity at the reference temperature T0; Ea is the activation energy, which represents the energy required for an electron (ion) to cross the barrier; and kB is the Boltzmann constant, with a value of about 8.617 × 10− 5 eV/K.

Modeling resistivity as a function of temperature

It is assumed that the resistivity is mainly caused by the distribution as well as the recombination of the charge carriers during the warming process. This process can be described using the activation energy (Ea), i.e., the charge carriers need to overcome certain obstacles in order to move. The resistivity ρ(T) and conductivity σ(T) are inversely related to each other, i.e. ρ(T) = 1/σ(T). And the conductivity is related to the concentration of carriers inside the carrier as well as the mobility law, the expression is.

where n(T) is the carrier concentration; q, he elementary charge; and µ(T) the mobility. Typically, the response of µ(T) to temperature is characterized as:

Here Eµ is the activation energy for carrier migration (J or eV).

By combining the Arrhenius equation and assuming that the carrier concentration does not vary with temperature, n(T) = n0, the conductivity can be transformed into:

The resistivity can be expressed as:

Let ρ0 = 1/n0qµ0 at the reference (room) temperature T0; substituting yields a practical form for fitting:

Here E0 denotes activation energy at T0, and Eµ captures temperature-induced changes in activation barriers.

At the macroscopic level, the resistivity of rock minerals is directly related to the movement of carriers at the microscopic level. At the microscopic scale, particles within the rock are subjected to specific forces, and these particles must accumulate sufficient energy to overcome energy barriers in order to transform into free-moving charge carriers. As temperature increases, the energy acquired by the particles also increases, allowing more of them to cross these energy barriers and become free charge carriers, which in turn reduces the resistivity of the rock.

In addition, at high temperatures, the thermal behavior of different mineral particles within the rock becomes inconsistent (e.g., due to the inhomogeneity and anisotropy of thermal expansion). This variability leads to mutual constraints between different parts of the rock, restricting free deformation in certain directions and thereby generating thermal stresses. When these stresses exceed the rock’s tolerance limit, microscopic cracks may form, eventually developing into larger cracks. The presence of such cracks increases the rock’s porosity, which ultimately leads to an increase in resistivity.

Theoretical study of rock dielectric properties

Theoretical basis for dielectric properties

Rocks can generally be regarded as special dielectric materials because they are composed primarily of non-metallic minerals. When subjected to an external electric field, a dielectric exhibits polarization and relaxation phenomena. Polarization refers to the rearrangement of internal charges, producing a macroscopic charge distribution, while relaxation describes the process by which charges attempt to return to equilibrium after removal of the external field.

The dielectric properties of materials vary with temperature and microwave frequency, and are usually expressed by the complex dielectric constant ε2,3:

where ε′ is the relative permittivity (or relative capacitance), ε″ is the dielectric loss factor, ε₀ is the permittivity of free space, and j is the imaginary unit.

In practical applications, since the absolute values of the dielectric constant of most materials are small, the complex relative permittivity is commonly used to quantitatively characterize the dielectric response. It can be observed that the complex relative permittivity consists of two components: the relative permittivity (ε′), which reflects the ability of the dielectric material to store electrical energy, and the relative dielectric loss factor (ε″), which represents the energy dissipation in the material.

The dielectric loss tangent (tanδ) is a parameter that simultaneously evaluates changes in both the dielectric constant and the dielectric loss factor, and it is defined as the ratio of the relative dielectric loss factor to the relative permittivity22,23:

Polarization mechanisms in dielectrics

The dielectric response of materials under different conditions is mainly governed by several polarization mechanisms, including orientational polarization (dipolar polarization), induced polarization (atomic and electronic polarization), and interfacial polarization24,25,26. Under an alternating electric field, the displacement of charges inside the dielectric is not instantaneous; instead, a certain delay occurs, reflecting the lag in the polarization response.

-

(1)

Orientational polarization.

In the absence of an external electric field, molecular dipoles are randomly oriented due to thermal motion, resulting in an overall macroscopic dipole moment close to zero. When an external electric field is applied, dipoles align along the field direction, leading to macroscopic polarization. The stronger the electric field, the more pronounced the orientational polarization. Conversely, as the temperature increases, molecular thermal motion disrupts the ordered alignment, thereby weakening the polarization effect. The establishment of orientational polarization is relatively slow (10−10–10−2 s), and its polarizability is usually several orders of magnitude higher than that of electronic polarization. The polarizability can be expressed using the Boltzmann distribution27:

where,\(\chi (0)\)is the electric field polarizability, a dimensionless number; k represents Boltzmann’s constant and T is the temperature. µ is the dipole moment, expressed as:

where q is the charge (C); l is the spacing between anisotropic charge centers.

-

(2)

Induced polarization.

Induced polarization consists of electronic and ionic polarization:

Electronic polarization: The electron cloud shifts slightly relative to the nucleus under the electric field, forming a transient dipole. The response is extremely fast (10−15–10−14 s), but the strength is relatively weak.

Ionic polarization: Positive and negative ions in the crystal lattice are displaced relative to each other under the electric field. This process is slower (10−13–10−12 s), but the polarization strength is greater than that of electronic polarization.

Overall, the total polarizability of a molecule can be considered as the sum of orientational polarizability and induced polarizability28. This effect occurs universally in atoms and molecules, regardless of whether the molecule has a permanent dipole or whether its structure is rigid or flexible. From first principles, the total molecular polarizability can thus be expressed as:

where Nd and Nm represent the number of dipoles and polarized molecules, respectively.

-

(3)

Interface polarization.

Interfacial polarization arises from charge accumulation at regions with different electrical properties, such as grain boundaries, phase interfaces, or material surfaces. As the temperature increases, carrier diffusion becomes stronger, leading to reduced interfacial charge density and polarization strength. This mechanism makes a significant contribution at low frequencies, substantially enhancing the dielectric constant, but is often accompanied by large energy losses. At high frequencies, however, because the polarization cannot keep up with the rapid changes of the electric field, its contribution diminishes, leading to a decrease in the dielectric constant.

Numerical modeling of dielectric properties and temperature

The dielectric properties of rocks are influenced by multiple factors, including mineral composition, water content, porosity, and temperature. Variations in these parameters affect the degree of polarization within the material, thereby altering its dielectric constant.

The effect of temperature is mainly manifested in the polarization process. Elevated temperatures enhance the mobility of polarized particles inside the material, thus influencing the dielectric constant. This relationship can be expressed as:

where ε0 is the dielectric constant at the reference temperature (usually room temperature), \(\chi (T)\)is the temperature-dependent change in polarization rate.

Polarizability \(\chi (T)\)Reflects how temperature affects the activity of polarized particles within a material, thereby changing the dielectric constant. Its derivation is based on the law of distribution in statistical physics, assuming that the activity of the polarized particles follows the Boltzmann distribution, and the derivation process is as follows: the energy distribution of the polarized particles at temperature T obeys the Boltzmann distribution, and its average energy is Ep. Assuming that the polarization rate at the base temperature is \({\chi _0}\), and that the activity of the polarized particles will change according to an exponential law for each unit change in temperature, we have:

Converting Celsius temperatures to absolute temperatures (K) can be expressed in the following form:

where \({\chi _0}\)is the base value of the polarizability; Ep is the activation energy associated with polarization, J/mol; and kB is the Boltzmann constant.

Bringing the \(\chi (T)\) above into the temperature dependence of the dielectric constant equation:

Thus, as temperature increases, the polarization rate decreases, leading to a lower dielectric constant. This theoretical result provides support for the experimental analysis in the following section.

Experimental study on temperature-dependent electrical properties of rocks

Specimen preparation and resistivity testing

This study selected 10 rock types from the overlying strata of coal seams in Shanxi Province as research objects. The sample preparation process is shown in Fig. 1. First, a sand-line cutting machine (a) was used to cut core samples (b) drilled from the mining area into circular thin sections with a diameter of 10 mm and a thickness of 3 mm (± 0.5 mm) (d). Subsequently, a grinding machine (c) was used to polish the upper and lower surfaces of the core slices to a smooth finish. A portion of the core samples had their upper and lower surfaces evenly coated with conductive silver paste to prepare specimens for electrical property testing.

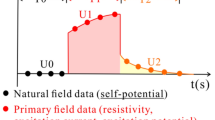

Characterization of resistivity anomalies in metamorphic rocks

Resistivity was measured in situ under variable-temperature conditions using a high-temperature insulation-resistance system, (as shown in Fig. 2), comprising an infrared reflective furnace, water cooler, vacuum pump, and insulation-resistance meter. The stated accuracy of the meter is: R < 10 GΩ: ±2%; 10 GΩ ≤ R < 1000 GΩ: ±5%; R ≥ 1000 GΩ: ±10%. A two-electrode configuration was adopted. Tests were performed from 30 °C to 700 °C at 3 °C min−1 under a vacuum of − 0.1 MPa (gauge); temperature stability over the full range was ± 1 °C.

Figure 3 shows the resistivity–temperature (ρ-T) curves of the ten rock samples, which exhibit similar overall trends. For clarity and analysis, the anomalous features of resistivity during heating are summarized by characteristic temperature points, as listed in Table 1.

The anomalous resistivity response of rocks under variable-temperature conditions can be divided into three stages:

Stage I (room temperature → Tρ,2): As the samples are heated, thermal stress causes the initiation and propagation of microcracks. At the same time, the absorption of heat and the evaporation of inherent pore water reduce carrier mobility and concentration. These effects cause resistivity to increase rapidly, reaching a peak value at Tρ,2.

Stage II (Tρ,2 → Tρ,3): With further heating, charge carriers are thermally activated and the microstructure undergoes significant changes. The effective energy barrier for carrier migration decreases, which enhances carrier concentration and electron transport. As a result, the resistivity of the rock decreases rapidly.

Stage III (Tρ,3→Tρ,4): At higher temperatures, thermal stress may lead to partial crack closure or even local melting, which facilitates electron migration. Although the ρ-T curve shows a less pronounced downward trend at the macroscopic scale, the data in Table 1 indicate that resistivity still decreases by 2–5 orders of magnitude in this stage.

To establish a reproducible quantitative correlation between the rapid decrease of resistivity in the second stage (Tρ,2 → Tρ,3) and the Arrhenius activation energy barrier model from “Theoretical study of rock dielectric properties”, we approximate the apparent activation energy Ea based on the characteristic points (Tρ,2, ρ2) and (Tρ,3, ρ3) of the various rock samples listed in Table 1 during the second stage.

In the equation, kB is the Boltzmann constant, approximately 8.617 × 10−5 eV/K.

Table 2 provides the two-point approximation of Ea for several representative samples (R1, R3, R6, R8, R10). Meanwhile, the steep decline in Stage II corresponds to an Ea in the range of approximately 0.2–1.0 eV, explaining the difference in the “rate of decrease” caused by variations in mineral composition and pore fracture differences, which aligns with the description of charge carrier migration and energy barriers in the previous section.

These results show that rocks exhibit different sensitivities to temperature under variable conditions. Variations in moisture content, carrier concentration, and microstructure jointly control the resistivity behavior at different temperature stages.

As seen from Table 1; Fig. 3, there are systematic differences in both the characteristic temperatures and amplitudes among samples. One group exhibits a resistivity peak at relatively low temperature (Tρ,2 ≲ 120 °C; e.g., R1, R3, R4, R6, R9), whereas another group reaches the peak only at higher temperature (Tρ,2 ≳ 250–300 °C e.g., R8), with some samples falling in between (e.g., R7, R10). These differences can be linked to (i) clay mineral content and the desorption windows of bound/interlayer water (from a few hundred to several hundred degrees Celsius), (ii) thermal expansion and structural strain dominated by quartz/SiO2, and (iii) initial moisture content and polarization pathways governed by porosity and connectivity. Specifically, a lower Tρ,2often indicates that free and weakly bound water escape substantially at lower temperature and that early thermally induced microcracking tends to occur—features commonly seen in rocks with lower clay content and/or lower initial moisture and higher compactness. By contrast, samples with higher Tρ,2 (e.g., R8) are more likely to contain larger amounts of clay phases or possess higher porosity/connectivity, so that bound water and interfacial polarization are not markedly disrupted until a higher temperature range, where carrier activation is triggered—delaying the turnover from resistivity rise to decline. This interpretation is also consistent with the group-wise difference in room-temperature resistivity: for instance, R8 already shows lower resistivity at room temperature, implying a stronger contribution of conductive phases/porosity/moisture to bulk conduction, which accords with its higher Tρ,2and the “delayed dewatering–delayed activation” behavior. The above links are qualitative and aim to anchor the electrical response to potential mineralogical/porous-structure attributes; cross-checks with dielectric spectra are provided below.

Characterization of dielectric anomalies in metamorphic rocks

In this study, a high-temperature dielectric spectrum test system (Fig. 4) was employed to characterize the dielectric response of ten overburden rock slices coated with conductive silver paste, as described previously. Measurements were carried out at different electric field frequencies during heating (Figs. 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 and 14).

The test system consisted of an infrared reflecting furnace, a water cooler, a vacuum pump, and a WK6500B precision impedance analyzer (basic accuracy: 0.05%, frequency range up to 1 MHz). The initial temperature was set to 30 °C, and the final temperature to 700 °C. A temperature step of 10 °C and a heating rate of 3 °C/min were adopted. The test chamber was maintained at a vacuum of − 0.1 MPa (gauge), with a temperature stability better than ± 1 °C across the full range. The dielectric parameters were measured at 50 kHz, 100 kHz, 500 kHz, and 1 MHz.

Through analysis of the experimental data, the dielectric response of rocks to temperature can be divided into three stages, and the corresponding characteristic parameters are summarized in Table 3.:

-

(1)

Room temperature → Tε,1: With increasing temperature, inherent water in the rock gradually evaporates, and thermal expansion initiates crack development. At this stage, the dielectric response is dominated by electronic polarization, and the dielectric parameters (ε′, ε″) decrease gradually.

-

(2)

Tε,1 → Tε,2In this temperature range, the dielectric constant and dielectric loss remain relatively stable, showing little sensitivity to further heating. This indicates that the rock exhibits good thermal stability, and that the contributions of space-charge, orientational, ionic, and electronic polarization are all weak29.

-

(3)

Tε,2 → 700 °C: At higher temperatures, the dielectric parameters (ε′, ε″) show a pronounced temperature dependence, i.e., both increase significantly with heating. This indicates that polarization processes are thermally activated, and various types of polarization are rapidly established, thereby enhancing the polarizability and charge storage capacity of the rock.

Furthermore, the dielectric loss–temperature curves reveal a relaxation peak near Tε,3. This peak reflects the inability of dipoles to follow the rapid changes of the external field at elevated temperature, leading to a sudden change in dielectric properties. This phenomenon is closely related to the mechanisms of microstructural evolution in rock samples. As the temperature increases, pores and microcracks within the rock undergo significant changes: on the one hand, thermal stress promotes the extension of pre-existing microcracks and the formation of new cracks; on the other hand, fluids within the pores gradually evaporate and redistribute, thereby altering the electrical continuity and polarization environment of the rock. These structural modifications directly affect the migration pathways of charge carriers and the accumulation of interfacial charges.

When the number of cracks increases or the pore structure becomes more complex, the contributions of interfacial polarization and space-charge polarization are significantly enhanced, leading to nonlinear variations of the dielectric constant and loss factor during heating. In contrast, under high-frequency electric fields, these microstructure-induced polarization mechanisms often fail to respond in time to the rapid alternation of the applied field, resulting in dielectric relaxation phenomena characterized by relaxation peaks and frequency dispersion. Therefore, dielectric relaxation is not only a physical manifestation of electrical response but also a macroscopic reflection of microstructural processes in rocks, such as the expansion of crack networks, changes in porosity, and the redistribution of interfacial charges under high-temperature conditions.

For the dielectric parameters of rocks measured at different frequencies, frequency dispersion is reflected in the fact that both the dielectric constant and the dielectric loss factor decrease with increasing frequency. Specifically, the dielectric constant is higher at lower frequencies but decreases as frequency increases, because slower polarization mechanisms cannot keep pace with the rapid changes of the applied electric field. In addition, the dielectric loss tangent (tan δ), which characterizes the ratio of energy dissipation to energy storage within the material, is also strongly affected by frequency.

The dielectric constant and loss increase broadly in the high-temperature range (Tε,2→700 °C), with a loss peak emerging near 500–560 °C (i.e., Tε,3), indicative of strong interfacial polarization/conductivity enhancement and thermally activated processes. Regarding inter-sample differences, those with more pronounced low-frequency increases in ε′ and ε″ (e.g., R8) generally correspond to a more developed pore–interface system and higher clay content (since polarizable groups in clays and bound water facilitate low-frequency polarization). Samples showing a sharper relaxation peak near 700 °C may reflect enhanced dielectric mismatch driven by structural strain/transformations in a quartz/SiO2-rich framework (manifested macroscopically as the accumulation and release of interfacial charges). Conversely, weaker rises in ε′/ε″ and a blunter peak shape are more consistent with mineral assemblages that are denser and poorer in pores/clays. This frequency-dispersion behavior corroborates the group-wise differences of Tρ,2/ Tρ,3 in “Characterization of resistivity anomalies in metamorphicrocks”: samples enriched in pores and clays not only display a higher Tρ,2(i.e., a “delayed turnover”) but also exhibit stronger low-frequency polarization and loss at elevated temperature.

The temperature dependence of the dielectric loss tangent at four test frequencies (50 Hz, 100 kHz, 500 kHz, and 1 MHz) is shown in Fig. 15, considering the variation of both the dielectric constant and the loss factor. The dielectric constant, dielectric loss factor, and dielectric loss tangent of the rock samples decrease gradually with increasing frequency, because ionic and orientational polarization mechanisms cannot follow the rapid changes of the applied field at higher frequencies. This incomplete establishment of polarization processes at high frequencies results in lower dielectric parameter values.

The frequency dependence of the dielectric loss tangent is consistent with that of the dielectric loss factor, indicating that ε″ plays a dominant role in the dielectric response of rocks. In contrast, the dielectric loss tangent increases with increasing temperature, and a loss peak appears. This peak is attributed to polarization mechanisms such as thermally activated dipolar processes and conduction effects, indicating that the dielectric relaxation behavior of rocks is closely related to polarization theory in solid-state physics.

Since moisture, porosity, and mineralogy are key controlling factors for electrical properties, within the existing experimental framework, we establish a qualitative correlation between the R1–R10 samples and their potential mineralogical, moisture, and porosity attributes based on electrical surrogate parameters.

-

(1)

Constraints from the clay–water system. Inter-sample differences in Tρ,2 offer thermal-window clues for bound-water desorption and the breakdown of interfacial polarization. R1, R3, R4, R6, and R9 (Tρ,2≲120℃) indicate substantial low-temperature water loss and early microcrack extension; R8 (Tρ,2≈304℃) suggests stronger water–clay coupling and a more developed interfacial-polarization network.

-

(2)

Role of the SiO2/quartz framework. The accelerated increase of ε′ and ε″ in the high-temperature regime and the relaxation peak near 500–560℃ (Tε,3) imply that framework-mineral thermal strain and the reconstruction of conductive pathways modulate the dielectric spectra. The sharpness of the peak and the magnitude of the increase can serve as indirect indicators of a “rigid, SiO2-rich framework + interfacial stress accumulation.

-

(3)

Impact of porosity/connectivity. Room-temperature resistivity together with the low-frequency ε′ (and its temperature-driven increase) jointly reflect the initial conditions of bulk conduction and polarization pathways. For example, R8 exhibits the lowest room-temperature resistivity and the largest high-temperature, low-frequency ε′ increase—consistent with an end-member combining higher porosity (or connectivity) and higher clay content; by contrast, samples such as R1/R9, with higher room-temperature resistivity and lower characteristic temperatures at the early stage of heating, are closer to the “dense–low-clay” end-member.

Note: These are qualitative mineralogical inferences based on electrical observations, intended to place Tρ,2, Tρ,3, Tε,3, and the low-frequency responses of ε′/ε″ within a unified “clay–SiO2–porosity–water” interpretive framework. Independent mineralogical and pore-structure characterization (e.g., XRD/Rietveld, TG–DTA, MIP/NMR) would be needed in follow-up work to quantify and validate the proposed links.

Conclusion

This study shows that temperature not only changes the absolute values of resistivity and dielectric parameters, but also restructures the underlying mechanisms of carrier transport and polarization, offering a new perspective for geophysical exploration and engineering safety.

-

(1)

Experiments on ten coal-measure surrounding-rock samples (30–700 °C, 50 kHz–1 MHz) indicate that the apparent activation energy, Ea, of representative samples is about 0.29–1.01 eV, integrating the temperature responses of electrical resistivity and dielectric spectra into a unified physical framework that links microscopic carrier transport/polarization with macroscopic observables.

-

(2)

Resistivity exhibits a three-stage evolution with temperature—initial increase → rapid decrease → gentle change—with sample-specific peak temperature Tρ,2 ≈ 66–360 °C. As temperature rises to 700 °C, resistivity decreases by 2–5 orders of magnitude overall. Dielectric parameters increase markedly after Tε,2 and display a loss-relaxation peak at Tε,3; with increasing frequency (50 kHz → 1 MHz), ε′, ε″, and tan δ all decrease, exhibiting typical dispersion.

-

(3)

Based on the “three stages—two thresholds—one peak” electrical-response signature, Tρ,2 delineates the temperature window in which resistivity transitions from increasing to rapid collapse, and Tε,3 characterizes the window of strong polarization/reconfiguration of conduction pathways. This criterion can be directly used to set thresholds and tune warning parameters for temperature correction in deep-resource electrical methods and for online monitoring of thermal damage in mines.

-

(4)

Future work aimed at engineering applications (building on the present study) will focus on cross-scale transition from the laboratory to the field: subsequent efforts should integrate confining pressure and extend the analysis to higher frequency bands (from RF to THz), explicitly couple water content/saturation with real-time hydrodynamic processes, and establish coupled high-temperature–high-pressure–water experiments. In combination with XRD/Rietveld, TG–DTA, and MIP/NMR techniques, these studies will quantify the“mineral-pore-water”structural parameters, and implement inversion-experiment closed-loop validation in underground and surface electrical observations.

Data availability

Data and other information can be obtained by contacting e-mail address 19335854441@163.com.

References

Ya, A. A. B. V. A. D. A S. Changes in the specific electrical resistivity of rocks at different depths of the geoelectric section and their comparison with Seismicity. Izvestiya Atmos. Ocean. Phys. 58(Suppl 1), S125–S139 (2023).

Fu, R. et al. Study on the mechanism of rock damage under microwave and laser irradiation through multiscale and multiphysics numerical modelling. Rock Mech. Rock. 57(2), 1079–1102 (2023).

Li, Y. et al. Conductive characterization of shale reservoir induced by pore fluids: A case study of longmaxi formation in Southern Sichuan region. Fuel. 387, 134412–134412 (2025).

Wang, Q. et al. Permittivity-Based Microwave Absorption Characteristics of Dongsheng Lignite during Pyrolysis, vol. 26(5), 641–646 (Wiley, 2016).

V. V B. An integrated study of the electrical parameters of the samples of magnetite ores in relation to their genesis and mineral composition (on the example of the Goroblagodatskoe skarn-magnetite deposit). Proc. High. Educ. Establish. Geol. Explor. 6, 77–84 (2019).

Ren, J. et al. Development of multi-field rock resistivity test system for THMC. Solid Earth. 14 (3), 261–270 (2023).

Gylfi Páll Hersir. Knútur Árnason. Resistivity of rocks. Hersir Árnason. 9 (29), 9–29 (2017).

Zhu, H. et al. Study on electrical properties of coal at spontaneous combustion characteristic temperature. J. Appl. Geophys. 159 (32), 707–714 (2018).

Du, C. et al. Investigation of pore structure evolution and damage characteristics of high temperature rocks subjected to liquid nitrogen cooling shock. Int. J. Damage Mech. 33(8), 605–638 (2024).

Alonso, U. et al. Ion beam analyses of radionuclide migration in heterogeneous rocks. AIP Conf. Proc. 1530(1), 87 (2013).

Chen Ji & Yang, X. Progress of experimental research on the conductivity of crustal rock minerals. Adv. Geophys. 32 (06), 2281–2294 (2017).

Belyanchikov, M. A. et al. Dielectric ordering of water molecules arranged in a dipolar lattice. Nat. Commun. 11 (1), 3927 (2020).

Huang, R. et al. Effect of crystal-water on the optical and dielectric characteristics of calcium sulfate in the THz band. Opt. Express. 32 (8), 13552–13561 (2024).

Jonathan Breeze. Temperature and Frequency Dependence of Complex Permittivity in Metal Oxide Dielectrics: Theory, Modelling and Measurement (Springer).

Shu, C. N. M A. Fabry–Perot open resonator technique for dielectric permittivity and loss tangent measurements of yttrium iron Garnet. IEEE Trans. Magn. 43(6), 2734–2736 (2007).

Lambert, P. Estimating & measuring the dielectric constant and loss tangent of dielectric lattice structures for additive manufacturing (Part 2). Microw. J. 66 (10), 52–60 (2023).

Suman, K. S. et al. Correction: Room temperature magneto–dielectric coupling in the CaMnO3 modified NBT lead–free ceramics. Appl. Phys. A 129(6) (2023).

Wang, B. et al. Achieving simultaneously low loss tangent and high resistivity in MgO modified Sr0.979Y0.014TiO3 colossal-permittivity ceramics via inhibiting the diffusion of oxygen vacancies. Ceram. Int. 50(23PC), 51650–51660 (2024).

Science-Earth Science. Studies in the area of earth science reported from Science University of Malaysia (a new approach in calculating porosity of shallow unconsolidated soil based on Archie’s Law). Sci. Lett. (2020).

Yang, J. Application and examination of arrhenius formula. Second. School Students’ Sci. Exam. 01, 46–48 (2025).

Ren, L. I. B. et al. Coal rock damage evolution law and permeability modeling under force-heat coupling. J. Saf. Environ. 20(05), 1727–1735 (2020).

Tian, J., Tao, J. & Xu, P. On the nature of vacuum dielectric constant. Sci. Technol. Inform. 14 (22), 441 (2012).

Fan, W. et al. Dielectric properties of coals in the low-terahertz frequency region. Fuel 162 (2015), 294–304 (2015).

Xu, G. et al. Experimental study on effective microwave heating/fracturing of coal with various dielectric property and water saturation. Fuel Process. Technol. 20(2020), 106378 (2020).

Wang, Q. et al. Microwave absorption characteristics during pyrolysis of Dongsheng lignite and Yallourn lignite. J. Coal. 41 (06), 1540–1545 (2016).

Liu, H. et al. Effect of coal rank on structure and dielectric properties of chars. Fuel 153 (2015), 249–256 (2015).

Xu, L. et al. Structural order and dielectric properties of coal chars. Fuel 137 (8), 164–171 (2014).

Shaaban, M. et al. Compositional dependence of the structural and dielectric properties of Li2O–GeO2–ZnO–Bi2O3–Fe2O3 glasses. J. Mater. Sci. 46 (5), 1295–1304 (2011).

Hong, R., Zhang, T. & Li, J. High temperature magneto-dielectric response and dielectric relaxations in PrIG. Ferroelectrics 618 (3), 646–654 (2024).

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52064043), the 2023 Higher Education Institution Science and Technology Innovation Program of Shanxi Province (Grant No. 2023L285), and the 2025 Postgraduate Academic and Practical Innovation Program of Shanxi Datong University (Grant No. 25SJCX15).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.Z. was responsible for experimental preparation and theoretical analysis sections; J.G. is responsible for experiments, data recording and analysis and paper writing; A.Z., W.F. is responsible for data checking and validation; W.W., D.Y., Y.L. were responsible for the collation of articles and correction of errors. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, X., Ge, J., Zhang, A. et al. Theoretical and experimental study of thermo electrical coupling mechanisms in coal bearing rocks. Sci Rep 16, 1246 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30831-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30831-7