Abstract

Skin-to-skin contact is known to help protect against traumatic birth experiences. However, it is sometimes not possible during cesarean sections, causing mother-infant separation. This pilot study explored a supportive alternative by streaming a live video of the newborn to the mother via a head-mounted display during the separation. Conducted in a Swiss hospital, this monocentric open-label non-randomized controlled pilot trial included 71 mothers. When separation occurred in the operating theatre, participants received either the head-mounted display intervention or standard care. Validated questionnaires were sent at one week and one month postpartum to assess maternal childbirth experience (primary outcome), birth satisfaction, childbirth-related post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms, anxiety and depression symptoms, mother-infant bonding and satisfaction with the procedure. Compared to the control group, mothers with the intervention reported a significantly enhanced childbirth experience at one week postpartum, greater birth satisfaction, reduced childbirth-related post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms, and diminished anxiety. Mothers unanimously expressed satisfaction with the intervention. These findings suggest using a head-mounted display to maintain visual contact with the newborn during early separation may be a valuable and well-accepted strategy to improve maternal childbirth experience. It also highlights the feasibility and acceptability of remote technologies in maternity care. Further research is warranted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

About one-third of mothers report experiencing childbirth as traumatic, which can lead to childbirth-related posttraumatic stress disorder (CB-PTSD)1. The overall estimated prevalence of CB-PTSD in community samples is 4.7%, and its prevalence among specific subgroups, such as women who have had an emergency cesarean section (CS) or premature birth can reach 21.1%1. In Switzerland, the cesarean section rate is approximately 33%, highlighting the relevance of addressing maternal experience during this type of birth2.

Skin-to-skin contact between mother and newborn immediately after birth seems to be an important protective factor against a traumatic birth experience3. However, this contact is more difficult to achieve during a CS, especially if unplanned, due to factors such as the relatively low room temperature in the operating theatre, the need to have a dedicated midwife to monitor the newborn, the mother’s uncomfortable position on the surgical table, anesthesiological constraints, or the emergency nature of the CS4. Despite efforts to facilitate skin-to-skin contact in the operating theatre, mothers and their newborns are sometimes separated at the end of the CS. The infant is taken to another room with the co-parent to receive the first care and to have a skin-to-skin contact with that person, while mothers remain in the operating theatre for the suturing. The separation may trigger negative emotions, including fear for one’s own and/or the baby’s life, feelings of failure, self-blame, and reduced self-esteem during and after birth. These emotions have been identified as risk factors for a negative birth experience6. Evidence on protective factors remains limited. Alternatives to facilitate early contact mother-newborn contact should be explored to provide options when skin-to-skin contact is impossible or interrupted, causing premature separation during the end of the CS.

Complementary methods, such as virtual reality (VR) headset or head-mounted displays (HMD) may offer potential solutions, though their effects on the mother-infant dyad have not yet been studied7.

The objective of this pilot trial was to evaluate the effect of an HMD showing a live video of the newborn to mothers who were separated from their baby immediately after birth during a CS. The primary outcome was maternal childbirth experience. Secondary outcomes included CB-PTSD symptoms, birth satisfaction, mother-infant bonding, perceived pain and stress during childbirth, maternal anxiety and depression symptoms, anesthesiological parameters, and acceptability of the intervention.

Materials and methods

Study design

e-motion-pilot, a monocentric open-label non-randomized controlled pilot trial, took place in the maternity ward of a Swiss University Hospital. The study was approved by the local ethics committee (approval number: 2022 − 00215) and prospectively registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (trial number: NCT05319665, registration date 08.04.2022); the study protocol was published8. Data collection occurred between April and November 2022. CONSORT guidelines were followed.

Study population, recruitment, group allocation

The study population included women who (1) were ≥ 18 years old, (2) underwent a CS, planned or not, (3) at ≥ 34 weeks gestation, (4) gave birth to a healthy baby according to pediatric evaluation, with an APGAR score of ≥ 7 at 5 min, (5) who could not maintain continued skin-to-skin contact in the operating room for any reason, (6) spoke French and (7) who gave oral and written informed consent. In the intervention group, (8) the partner/co-parent had to give oral informed consent to be filmed, and (9) an independent medical doctor had to confirm eligibility. The exclusion criteria were having (1) an established disability or psychotic illness, (2) photosensitive epilepsy, and (3) having a CS under general anesthesia.

In our center, skin-to-skin contact is the routine practice in the operative room and is continued until the end of the CS if possible. In the case of a continued skin-to-skin contact during the whole period of the CS, the mother was not included in the study, as skin-to-skin contact was the first and preferred option.

For ethical reasons this trial did not follow a randomized controlled trial design. This was decided in agreement with the ethics committee, aiming to avoid inducing frustration for mothers who were not selected for the intervention (see Corbaz et al., 2023 for details)8.

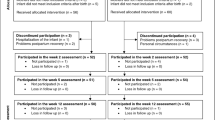

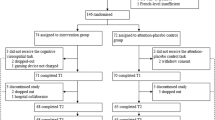

Participants were assigned to either the control or the intervention group depending on the trial phase. During the first phase, participating women were included in the control group. Once the target number of control participant was reached, the second phase began, and eligible women were included in the intervention group.

Recruitment encompassed several stages: Potential participants were informed about the ongoing trial, specifically women scheduled for a CS or attending their 36-week antenatal appointment. Participants then provided oral informed consent pre-CS or immediately post-procedure in the recovery room. Formal written informed consent was secured on the postpartum ward within 24 h of the CS (see Corbaz et al., 2023 for details)8.

The process entailed three supplementary steps for those in the intervention group, aligning with Swiss protocols for emergency interventional research. This included an affirmation from an impartial physician not associated with the study or the participant’s direct care, ensuring the participant’s best interests. Additionally, both the partner/co-parent and the midwife had to provide oral and written informed consent for filming (see Corbaz et al., 2023 for details)8.

Procedure

During unplanned newborn separation, participants in the intervention group used an HMD during the end of the CS. This device transmitted real-time visuals and sounds from a 2D 360° camera in an adjacent room, capturing the newborn, co-parent, and midwife. Mothers could observe their newborn’s initial care, weight and measurement procedures, and the skin-to-skin interaction with the co-parent. The 360° perspective allowed mothers to adjust their viewpoint with simple head movements. Figure 1 shows the intervention. As a precaution in case of a neonatal complications during the live HMD feed, a member of the medical staff was assigned to remain with the mother to provide real-time explanations and reassurance, ensuring maternal understanding and minimizing distress during critical moments.

Conversely, in case of mother-infant separation, control group participants received customary care during CS, which consisted of remaining in the operating room until the end of surgery without visual or auditory access to their newborn. Both groups completed online questionnaires at one and four weeks postpartum via REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture, a secure web application for building and managing online surveys and databases —projectredcap.org) (see Corbaz et al., 2023 for details)8.

Outcomes

Primary outcome measure

The primary outcome was a difference in childbirth experience using the Childbirth Experience Questionnaire 2 (CEQ-2)9 between the intervention and the control group at one week postpartum. CEQ-2 assesses women’s experiences during childbirth across multiple domains (own capacity, professional support, perceived safety, and participation); items are scored on a 4-point Likert scale (from totally agree to totally disagree), for example: ‘I felt capable during labor and birth’9. For details on the primary and secondary outcome measures and their psychometric properties, see Corbaz et al., 20238.

Secondary outcomes measures

The Birth Satisfaction Score Revised, along with the Mother-Infant Bonding Scale and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, were the tools used to assess birth satisfaction, mother-infant bonding, and depression or anxiety symptoms at one week postpartum. At one month postpartum, the presence of CB-PTSD symptoms was evaluated with the City-Birth Trauma Scale, and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale was used again to assess depression and anxiety symptoms. Details on the questionnaires are given in the published protocol (Corbaz et al., 2023)8.

For the intervention group only, twelve further questions were asked regarding their global satisfaction with the intervention, its utility, the comfort of the HMD, the quality of the images, sound, and camera-HMD connection, and the advantages and disadvantages of the HMD (Table 3).

Statistical analysis

Without previous research on this specific topic, the sample size calculation was based on standard conventions (35 participants per group) that apply to the context of a pilot trial10.

Differences between groups were assessed on sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of participants using Wilcoxon rank-sum tests, t-tests, Chi-square, and Fisher’s exact tests according to the nature of the variables. The internal consistency of the questionnaires was estimated using Cronbach’s alpha11. Items analysis was conducted when internal consistency of a questionnaire was low, but the results are not reported in this study11. To analyze the differences between groups on questionnaires’ scores, we first applied Shapiro-Wilk tests to determine whether the scores were normally distributed. For normally distributed scores, intervention and control group mean scores were compared using type III one-way ANOVA. For non-normally distributed scores we used Mann-Whitney U tests to compare the intervention and control groups’ median scores. Effect sizes were estimated using eta-squared for normally distributed scores and using r otherwise according to conventional guidelines12.

Analyses of the questionnaires were conducted in RStudio v1.3.1093 running R core v4.1.0 and analyses of the demographic data with Stata V17 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX, USA). P values of ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

We conducted a thematic content analysis13 of the responses to the open questions in the questionnaires. Data were analyzed using an inductive approach to identify patterns that emerged. As the responses were in French, a double translation was done to ensure the correct English. Two research team members (FC and DD) independently read the responses and generated themes. Responses were collectively sorted into different themes, and the frequency of the themes in the responses was analyzed.

Results

Recruitment and participant flow

Recruitment occurred at the Lausanne University Hospital between April and October 2022, with final data collection completed by November 2022. The inclusion of each group lasted 3 months. Figure 2 depicts the recruitment throughout the study. Out of the 325 women assessed, 253 were deemed ineligible. Consequently, 72 women were enrolled into two evenly distributed groups. Of these, 71 participants (n = 35 in the control and n = 36 in the intervention group), were included in the analyses. Remarkably, the acceptance rate to participate in the study was commendably high, with the control group registering 89.4% and the intervention group achieving 92.5%.

Sociodemographic and obstetrical data

Table 1 summarizes demographic and obstetric details. No significant disparities concerning demographic elements were observed between the intervention and control groups. However, significant variations emerged regarding gestational age during the CS and the CS’s indication (p < 0.05). The mean gestational age was slightly lower in the intervention group compared to the control group. Regarding CS indications, elective reasons such as maternal request and breech presentation were more common in the intervention group, while medical or urgent indications such as abnormal CTG or maternal pathology were more frequent in the control group.

Childbirth experience questionnaire 2 (primary outcome)

Regarding the main outcome, the Childbirth Experience Questionnaire 2 (CEQ-2) showed significant differences between groups in median scores. The intervention group scored significantly higher, with 3.44 points, than the control group with 3.29 points, on the total score (z=-2.07, p = 0.04), with a small effect size r = 0.25 [0.01, 0.46] and on the Perceived safety subscale (z=-2.61, p = 0.01), with a medium effect size r = 0.31 [0.09, 0.51] (see Fig. 3). This suggests that mothers in the intervention group experienced an overall improved childbirth experience and felt safer during birth. No significant group differences were found between groups for the Own Capacity, Professional Support, and Participation subscales. Full results from the validated questionnaire are reported in Table 2.

Participating mother using the head-mounted display and Camera filming the newborn. The picture on the left shows a mother wearing a head-mounted display in the operating room during the end of the cesarean section. The picture on the right shows the 2D 360° camera filming the first care of the newborn. This is what the mother can see through the head-mounted display. © Property of the Lausanne University Hospital.

Primary outcome. There is a significant difference for the childbirth experience total score and the “perceived safety” subscale between the intervention and the control group, indicating a better childbirth experience and a higher sense of safety in the intervention group. ctl: control group, intervention group, ns: non-significant, *: significant result with a small effect size, **: significant result with a medium effect size.

Birth satisfaction scale revised

For the Birth Satisfaction Scale Revised questionnaire, there were significant group mean differences for the total score (F(1, 69) = 5.04, p = 0.03) and the subscale “Quality of care provision” (z=-2.19, p = 0.03) between the intervention and control group, with the intervention group scoring higher than the control group, i.e. the intervention group had a greater satisfaction of the birth and had a feeling of better quality of care provision. The effect sizes were respectively considered medium (η2 = 0.07 [0, 1]) and small (r = 0.26 [0.04, 0.46]). No significant difference was observed for the subscales “Women’s personal attributes” and “Stress experienced during labor”. The internal consistency of the total and sub-scales was considered poor to acceptable.

City birth trauma scale

The results of the City Birth Trauma Scale questionnaire showed that the intervention group reported significantly fewer CB-PTSD symptoms than the control group (z=-2.03, p = 0.04). The effect size was considered small (r = 0.24 [0, 0.44]). Regarding the subscale “Negative cognitions and mood”, the intervention group scored marginally significantly lower than the control group (z=-1.92, p = 0.06). The effect size was considered small (r = 0.23 [0, 0.44]). No other significant group differences were found.

Hospital anxiety and depression scale

For the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, the results showed that at one-week postpartum, significant disparities were detected in psychological distress and depression symptoms (z=-2.63, p = 0.01 and z=-2.49, p = 0.01), with the control group manifesting elevated levels compared to the intervention group. Effect sizes were medium (r = 0.31 [0.09, 0.52], r = 0.3 [0.08, 0.5]). No significant variation was observed for the HADS anxiety sub-scale. At one-month postpartum, a notable difference emerged in anxiety scores (z=-2, p = 0.05), with the control group indicating heightened anxiety. The effect size was small (r = 0.24 [0.01, 0.46]). Elevated scores in psychological distress and depression symptoms persisted in the control group at one month, albeit non-significantly.

Mother-to-infant bonding scale

Regarding the Mother-to-Infant Bonding Scale, the control group scored higher than the intervention group, indicating more bonding problems, but not significantly. Of note, the internal consistency of the total scale (α = 0.26) was below the threshold of 0.70 considered acceptable, explained by a poor correlation between items.

Satisfaction with the intervention

In this study, most participants expressed high satisfaction with the intervention: the majority (79%) were very satisfied, and the remaining (21%) were satisfied. Almost all (91%) found the intervention very useful. The HMD was comfortable for 56% of participants, while the majority rated the sound (91%) and image (77%) quality as good. A stable connection was reported by most participants (91%). Importantly, all participants believed the intervention positively influenced their birth experience, with 71% describing the impact as very positive. Every participant would advocate for the intervention among peers. All questionnaire results on the satisfaction of the intervention can be found in Table 3.

Answers to open questions, listed on Table 4, revealed that the intervention provided participants with feelings of proximity to their baby or co-parent and a mental reprieve from the operative theatre. The HMD was proved to be beneficial by facilitating real-time visuals and sounds of the baby, which offered assurance and captured precious moments like initial baby care and skin-to-skin contact with the coparent. Many found it sped up their perceived duration of the cesarean section and minimized their perceived stress.

Among enhancements suggested, sixteen participants proposed upgrading sound or image quality. Three comments hoped for a feature enabling the mother to communicate with the co-parent, while two desired downloadable videos post-intervention. Although 14 comments identified no drawbacks, four pointed out the HMD’s sizable design, suggesting a more compact version.

Variables during the cesarean section

As delineated in Table 5, most women in the study experienced initial skin-to-skin contact. They were 42.8% in the control group and 63.8% in the intervention group (preceding the intervention). This disparity was statistically insignificant (p = 0.076). However, the duration of such contact exhibited significant variance (p = 0.046) – averaging 17.47 min in the control group and 12.52 min in the intervention group. On average, the head-mounted display (HMD) was utilized for 18.61 min. Notably, both groups displayed no differential prevalence in adverse symptoms like nausea, vomiting, or headaches. No mother was exposed to her baby being in a life-threatening situation when wearing the HMD.

Discussion

This open-label controlled pilot trial demonstrated that using an HMD significantly improved maternal childbirth experience at one week postpartum, particularly by increasing perceived safety during birth. Participants in the intervention group reported higher birth satisfaction, better perceived quality of care, fewer CB-PTSD symptoms, and lower depressive symptoms at one week postpartum than controls. Overall satisfaction with the intervention was overwhelmingly positive.

Prior research emphasizes the pivotal role of the medical and care team support during childbirth in mitigating traumatic experiences or CB-PTSD14. Crucial elements include effective communication, informed consent, and ensuring mothers feel acknowledged and in control15.

The results of the current study, especially of the CEQ-2 and BSS-R, show that women of the intervention group felt safer and perceived better quality of care, corroborating the previous studies. Evidence shows that continuous care from a known and trusted provider decreases the rate of negative childbirth experience16. Maintaining virtual contact with their baby while the midwife provided care may have contributed to a better overall childbirth experience. Importantly, this pilot trial tested the effect of HMD during childbirth, a novel approach with limited prior research, and aligns with another RCT using VR during childbirth that reported higher patient satisfaction17. In addition, in line with another study, no side effects were linked to using an HMD in our trial18. Although no complications occurred, developing formal protocols, co-designed with clinicians and parents, for managing the live HMD feed in case of neonatal emergencies will be essential for broader clinical implementation.

A larger RCT is the logical progression, with a reconsideration of the MIBS tool due to validity concerns.

This pilot trial had many strengths, including using validated questionnaires, a control group, a prospective trial registration, a rigorously trained clinical team and follow-up until one month postpartum. The analyses were conducted by an independent senior statistician. Nonetheless, several limitations need to be highlighted. Given the pilot nature of this study and the absence of a priori power calculation, statistical differences should be interpreted with caution. The primary aim was to assess feasibility and explore potential trends rather than to draw definitive conclusions. The groups were not randomized, which may have induced a possible selection bias. As both groups were not comparable on all variables of the obstetrical data, a confounding bias is a possibility. Furthermore, due to the small population, no sub-group analyses were conducted regarding parity or history of CB-PTSD. As this study was open-label, performance, detection and recall bias may have been generated.

Lastly, it is important to note that this study does not position HMD as an alternative to skin-to-skin contact.

Conclusion

The pilot suggests that HMD streaming of the newborn to the mother during the later stages of a cesarean section could positively transform the childbirth experience. This method was well-received and easily integrated into standard care without identified side effects.

Data availability

Data will be made available upon reasonable request by contacting the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- BSS-R:

-

Birth Satisfaction Scale Revised

- CB-PTSD:

-

Childbirth-related post-traumatic stress disorder

- CEQ-2:

-

Childbirth Experience Questionnaire 2

- CityBiTS:

-

City Birth Trauma Scale

- CS:

-

Caesarean section

- HADS:

-

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

- HMD:

-

Head-mounted display

- MIBS:

-

Mother-to-Infant Bonding Scale

- VR:

-

Virtual reality

References

Heyne, C. S., Kazmierczak, M. & Souday, R. Prevalence and risk factors of birth-related posttraumatic stress among parents: A comparative systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2022.102157 (2022).

Bischof, A. Y. & Geissler, A. Making the cut on caesarean section: a logistic regression analysis on factors favouring caesarean sections without medical indication in comparison to spontaneous vaginal birth. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 23, 759 (2023).

Hernández-Martínez, A. et al. Perinatal factors related to post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms 1–5 years following birth. Women Birth. 33, e129–e135 (2020).

Balatero, J. S., Spilker, A. F. & McNiesh, S. G. Barriers to skin-to-skin contact after cesarean birth. MCN Am. J. Matern Nurs. 44, 137–143 (2019).

Boyd, M. M. Implementing skin-to-skin contact for cesarean birth. AORN J. 105, 579–592 (2017).

Kahalon, R., Preis, H. & Benyamini, Y. Mother-infant contact after birth can reduce postpartum post-traumatic stress symptoms through a reduction in birth-related fear and guilt. J. Psychosom. Res. 154, 110716 (2022).

Boussac, É., Berna, P., Dias, C. & Pre Horsch, D. G. A. & Dr Desseauve, D. Apport de l’utilisation de la réalité virtuelle lors de l’accouchement. Rev Med. Suisse 17, 1779–1784. https://doi.org/10.53738/REVMED.2021.17.755.1779 (2021).

Corbaz, F. et al. ConnEcted caesarean section’: creating a virtual link between mothers and their infants to improve maternal childbirth experieNce – study protocol for a PILOT trial (e-motion-pilot). BMJ Open. 13, e065830 (2023).

Dencker, A., Taft, C., Bergqvist, L., Lilja, H. & Berg, M. Childbirth experience questionnaire (CEQ): development and evaluation of a multidimensional instrument. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 10, 81 (2010).

Whitehead, A. L., Julious, S. A., Cooper, C. L. & Campbell, M. J. Estimating the sample size for a pilot randomised trial to minimise the overall trial sample size for the external pilot and main trial for a continuous outcome variable. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 25, 1057–1073 (2016).

Cronbach, L. J. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 16, 297–334 (1951).

Cohen, P., Cohen, P., West, S. G. & Aiken, L. S. Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781410606266 (Psychology Press, 2014).

Braun, V. & Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101 (2006).

Kranenburg, L., Lambregtse-van den Berg, M. & Stramrood, C. Traumatic childbirth experience and childbirth-related post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD): A contemporary overview. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 20, 2775 (2023).

Hollander, M. H. et al. Preventing traumatic childbirth experiences: 2192 women’s perceptions and views. Arch. Womens Ment Health. 20, 515–523 (2017).

Bohren, M. A., Hofmeyr, G. J., Sakala, C., Fukuzawa, R. K. & Cuthbert, A. Continuous support for women during childbirth. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017 (2017).

Carus, E. G., Albayrak, N., Bildirici, H. M. & Ozmen, S. G. Immersive virtual reality on childbirth experience for women: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 22, 354 (2022).

Akin, B., Yilmaz Kocak, M., Küçükaydın, Z. & Güzel, K. The effect of showing images of the foetus with the virtual reality glass during labour process on labour pain, birth perception and anxiety. J. Clin. Nurs. jocn.15768. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15768 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We thank Dre Alexia Cuenoud, Ms. Julie Bourdin, Ms. Gabriela Dumitru, and Ms. Marion Lapalu for their support. We also appreciate the midwives and the obstetric team at Lausanne University Hospital. Special thanks to our study participants for their time and involvement.

Funding

Fiona Corbaz received a project grant from the Medicine Faculty of the University of Lausanne and the Solis Foundation with a matching fund from the Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics of the CHUV as salary. Antje Horsch is a member of the COST CA22114 management board.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.B. and D.D. conceptualized the use of the device, A.H. and D.D. designed the study with input from all coauthors and members of the consortium. S.M. developed technological solutions for the study. F.C., E.B., K.L., D.B. and D.G.D. participated in the design. Statistical analyses were conducted by A.L. A.H., D.D. and F.C. drafted the manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript and approved its final version. A.H. and D.D. contributed equally as last authors. An informed written consent from all subjects for publication of identifying images in an online open-access publication was obtained.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics and clinical trial registration

The study was approved by the local cantonal ethics committee (Commission cantonale d’éthique de la recherche sur l’être humain, approval number: 2022 − 00215). Study methods were performed in accordance with the ethics committee guidelines and regulations. The study was registered on clinicaltrial.gov on 08.04.2022 with an initial patient enrollment on 10.04.2022, number NCT05319665, https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05319665.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Corbaz, F., Boussac, E., Lepigeon, K. et al. Virtual link between mothers and infants to improve maternal c-section experience: a non-randomized controlled pilot trial. Sci Rep 16, 3493 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30837-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30837-1