Abstract

This study aims to investigate gut microbiota and metabolomes of fecal, cecum, serum, and ovarian tissues in a DHEA-induced rat polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) model and explore the gut–ovary axis in PCOS pathogenesis. Rats were treated with DHEA or sesame oil to create PCOS and Control groups. The PCOS model was confirmed by ovarian morphology, estrous cycle, and serum hormone levels (FSH, LH, and E2). Stool, serum, cecum, and ovarian tissues underwent untargeted metabolomic analysis, and gut microbiota were assessed using 16S rRNA sequencing. Differentially expressed metabolites (DEMs) were analyzed using KEGG function and pathway enrichment analyses. Pearson’s correlation analysis between DEMs and gut microbiota was performed. RT-PCR and Western blotting analyses determined intestinal integrity markers. Western blotting validated key pathways. DHEA treatment induced PCOS in rats as indicated by hormonal imbalances, ovarian histopathological changes, and estrous cycle disruption. PCOS rats exhibited increased alpha diversity and beta-diversity in gut microbiota and gut microbial community compositions, indicating dysbiosis. PCOS group fecal, cecal, serum, and ovarian metabolic phenotypes differed significantly from those of the control group. KEGG function and pathway enrichment analysis of DEMs indicated that all PCOS group sample types exhibited steroid hormone and lipid metabolism disturbances. DEMs in fecal, cecal, serum, and ovarian samples were closely correlated with differential gut microbiota and serum hormones relevant to PCOS. Expression levels of CLDN3 and Occludin that are involved in intestinal integrity were altered, and protein expression levels of Cyp4b1 and 3B-HSD that are involved in ovarian steroid hormone metabolism were disordered. DHEA-induced PCOS rats exhibited significant microbiota and metabolomes disruptions, particularly in the steroid, lipid, and amino acid pathways. Key metabolites (17α-Hydroxyprogesterone, Ethyltestosterone, and Pregnenolone) were closely linked to PCOS-related hormones and altered microbiota such as Bacillus and Akkermansia. These findings suggest the potential involvement of the gut–ovary axis in PCOS development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a common gynecological and endocrine disorder characterized by excessive blood androgen levels, ovulation dysfunction, irregular menses, multiple ovarian cysts, and metabolic disturbance1,2,3,4,5. With an incidence of approximately 5–10% among women of childbearing age, PCOS affects a huge patient population and is one of the main causes of infertility6. In recent decades, the incidence of ovulatory dysfunction infertility caused by PCOS has increased, causing serious physical, psychological, and economic burdens to patients and affecting their quality of life7,8. Though numerous previous studies have indicated that PCOS results from complex gene environment interactions and hyperandrogenism and that the subsequent multi-system metabolic disturbances are considered pivotal factors in the pathogenesis of PCOS9, the definitive mechanisms remain elusive10.

In recent years, numerous studies have focused on the gut microbiota, an indispensable component of the human and animal body that profoundly influences host metabolism and may play an important role in PCOS pathogenesis11. Guo et al. reported an imbalanced gut microbiota in a rat model of PCOS that was characterized by a decreased abundance of Lactobacillus, Ruminococcus, and Clostridium and an increased abundance of Prevotella12. Similarly, clinical studies have indicated that patients with PCOS exhibit lower gut microbiota richness and diversity than that of healthy controls13. In contrast, Qi observed a significant upregulation of B. vulgatus in patients with PCOS, and the treatment of wild-type mice with B. vulgatus led to ovarian dysfunction and exacerbated PCOS, indicating that the disrupted gut microbiota could also shape the phenotype of the host14. However, the underlying mechanisms by which these alterations in the intestine influence the ovaries and lead to changes in ovarian function and subsequently contribute to the development of polycystic ovaries remain unclear.

Metabolomics allows for the qualitative and quantitative assessment of thousands of metabolites across various biological samples. This aided in the identification of novel differentially expressed metabolites (DEMs). Emerging evidence has revealed that metabolically bioactive molecules produced by microbes inhabiting the gut may play an intermediary role in the pathogenesis of various endocrine-metabolic diseases15,16,17,18,19,20. This discovery inspired our investigation into whether and how the gut microbiota is involved in the metabolic and endocrinological disturbances associated with PCOS. Inspired by the established concepts of the gut microbiota-brain and gut microbiota-immunity axes14,15,21,22, we postulated that analogous interactions between the gut microbiota and ovaries (the gut–ovary axis) may also exist and significantly contribute to the development of PCOS.

Hence, to investigate the role of gut microbiota in PCOS pathogenesis and the metabolomic disturbance of PCOS in other organs, we established rat PCOS models through subcutaneous DHEA injection, a widely employed method for recapitulating PCOS-like phenotypes and metabolic alterations in rats and mice20,23. We subsequently conducted comprehensive metabolomic analyses of multiple tissue types and sequenced the gut microbiota. As one of the first studies to report the metabolomic changes in multiple organs in a PCOS rat model and its correlation with gut microbiota and to introduce the concept of the gut-ovary axis, we aimed to unravel the complex interplay between the gut microbiota and the metabolomes of PCOS hosts and identify novel biomarkers and potential therapeutic targets for this complicated endocrine-metabolic syndrome.

Material and methods

Study design

The present study was conducted according to the flowchart presented in Fig. 1. Initially, PCOS rat models were established through subcutaneous DHEA injection, and the validity of the PCOS model was assessed by examining ovarian morphology, estrous cycles, and serum concentrations of relevant hormones. Upon successful confirmation of the established PCOS model, the metabolomes of four sample types, including stool, serum, cecum, and ovarian tissues from rats in both the PCOS and Control groups, were analyzed. Additionally, the gut microbiota was sampled and subjected to 16S RNA sequencing and ovarian transcriptome analysis. Bioinformatics analysis was subsequently conducted to elucidate the disturbance in multiple metabolomes and gut microbiota resulting from DHEA treatment as well as to identify the correlations between the differential metabolites in these four types of tissues and the differential gut microbiota. Specifically, 15 rats were initially purchased for each group, of which 2 were excluded at baseline due to body weight differences compared to the rest. Thus, 14 rats per group underwent DHEA/sesame oil administration, and following exclusion of 3 additional control rats with abnormal weight gain, 11 rats in the control group and 14 rats in the PCOS group proceeded to planned sample collection. After multi-omics quality control, 16S rRNA microbiome analysis included all collected samples (11 in Control, 14 in PCOS), whereas subsequent metabolomic and transcriptomic assays excluded 2 control and 4 PCOS samples that failed quality standards, leading to final sample sizes of 9 controls and 10 PCOS for these analyses.

The schematic diagram showing the workflow of the current study. The flowchart depicts the five primary procedures of present study: which include model establishment, model validation, sample collection, microbial diversity, and multi-omics analysis, and result verification. In the model establishment phase, subcutaneous injections of DHEA-containing oil and an equal volume of pure sesame oil were administered to rats for consecutive weeks. The two groups were hence designated as PCOS group (n = 14) and Control group (n = 11), respectively. Then the stool, serum, cecum, and ovary were sampled. The ovary morphology, menstrual cycles, and the concentration of reproductive hormones in the serum of the rats from both groups were investigated to verify the establishment of PCOS model. Comprehensive analysis of metabolomes in stool, serum, cecum, and ovarian tissues, as well as the gut microbiota of both groups, were carried out. Finally, the expression of mRNAs and proteins involved in intestinal integrity and the ovarian steroid hormone metabolism were verified through real time PCR or WB.

Animal experiments and model establishment

All rats were purchased from the Ensiweier Company (Chongqing, China) and possessed similar body weights and birth dates. After arrival, they were numbered from 1 to 25. Using a random number table, rats were randomly assigned to either the control group (n = 14) or the DHEA group (n = 11). PCOS rat models were established according to a method described in previous publications23. Three-week-old female Sprague–Dawley rats were housed at three to five per cage under standard laboratory conditions (12 h light:12 h darkness cycle) with food and water available ad libitum. This study is reported in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines. All animal experimental procedures were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Chongqing Traditional Chinese Medicine Hospital (No.2022-DWSY-CZ) and conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All animal experiments were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

The DHEA group was administrated DHEA s.c. at 6 mg/100 g body weight on a daily basis (dissolved in 0.2 ml of sesame oil) from day 21 to day 42 to establish PCOS model. The Control group was treated with an equivalent volume of sesame oil in the same manner. After 21 days of treatment, all animals were subjected to estrous cycle investigation, serum collection, and sacrifice, after which ovarian and intestinal tissues were collected, and ovarian pathological structures were examined24. The rats were 6 weeks old (42 days) and weighed 202.12 ± 14.12 g in the control group and 198.51 ± 8.18 g in the PCOS group at the time of anesthesia and euthanasia (Fig. S1). Inhalational anesthesia with isoflurane was administered by placing the animal in the induction chamber connected to an anesthesia machine. Oxygen flow rate was adjusted, and the isoflurane concentration was set to 5% for induction, which typically took approximately 1–2 min. Following induction, the isoflurane concentration was reduced to 2%, and anesthesia was maintained via a face mask. The anesthesia machine and isoflurane reagent were provided by RWD Life Science Co., Ltd. (Shenzhen, China). After isoflurane-induced anesthesia, euthanasia was performed using cervical dislocation. The cessation of respiration and heartbeat is regarded as an indication of death of the rats.

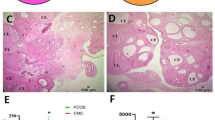

Ovarian morphological investigation

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining was performed to investigate ovarian morphology. The ovaries were fixed overnight in 4% formaldehyde at room temperature, soaked in 70% ethanol, dehydrated, and embedded in paraffin. Next, samples were sectioned to 4 μm thickness, deparaffinized, and rehydrated using alcohol at gradient concentrations. Sections were subsequently stained with hematoxylin and eosin (Servicebio Technology CO., LTD Company, Wuhan, China). Stained sections were observed under a light microscope (NIKON DS-U3, Nikon, Japan) for histomorphological examination. Simultaneously, the ovarian area, the thickness of the follicular wall, and the granulosa cell layer were analyzed using ImageJ 1.50i software. The detailed staining and measurement protocols used in this study were based on previous studies25,26.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Blood samples were collected after enucleation of the eyeball from rats anesthetized with isoflurane. The serum was centrifuged at 3000g for 15 min at room temperature. Serum samples were analyzed for follicle stimulating hormone (FSH), luteinizing hormone (LH), testosterone (T), estrogen (E2), and insulin (INS) by commercial enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay kits (Elabscience, Biotechnology Co., Ltd, Wuhan, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The kit product numbers included FSH (E-EL-R0391c), LH (E-EL-R0026c), E2 (E-EL-0152c), INS (E-EL-R3034), and T (E-EL-0155c). Briefly, serum samples (50 μl) were added to each well, and biotinylated antibody working fluid (50 μl) was then immediately added. The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 45 min., and the samples were then removed. After washing with wash buffer (350 μl), 100 µl of working solution conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP) was applied, and this was followed by the application of substrate reagent. The microplate was then incubated for 30 min. If an apparent gradient of color in standard wells appeared, the stop solution (50 µl) was applied. Optical density (OD) was detected at 450 nm. Data were collected and analyzed using Prism (version 9.0, GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA).

Estrus cycle determination

From days 32 to 39 after DHEA treatment, when the PCOS phenotype was likely to be stably established, the estrous cycle was continuously monitored for approximately two complete cycles by daily assessment of vaginal smears under light microscopy. The estrous cycle of each rat was analyzed based on the presence or absence of different cell types, where proestrus included nucleated epithelial cells, the estrus stage included cornified squamous epithelial cells, metestrus included cornified epithelial cells and a predominance of leukocytes, and diestrus included primarily leukocytes27,28.

Metabolomic analysis

The metabolite extraction and quality control methods used in the present study were similar to those described in previous publications29. After the extraction, LC–MS/MS analysis was conducted using an ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 column30,31.

The initial data were analyzed using Progenesis QI 2.3 software (Nonlinear Dynamics, Waters, USA) for peak detection and alignment. Metabolic characteristics with a relative standard deviation of QC of greater than 30% were excluded. Mass spectra of these metabolic features were identified using the accurate mass, MS/MS fragment spectra, and isotope ratio differences from the Human Metabolome Database (http://www.hmdb.ca/) and the Metlin database (https://metlin.scripps.edu/). A mass tolerance of ± 10 ppm was maintained between the observed m/z values and the exact masses of the target compounds.

Multivariate statistical analysis was performed using the R package ropls (Version1.6.2). Principal component analysis (PCA) and orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analyses (OPLS-DA) were used for group separation. Model validity was assessed based on R2 and Q2 that reflect interpretability and predictability, respectively. p Values and variable importance in the projection were calculated using the OPLS-DA model to determine DEMs between groups. Metabolites with VIP > 1.0 and p < 0.05 were recognized as DEMs. Metabolic enrichment and pathway analyses were performed using the summarized DEMs and the KEGG database32,33,34. All raw metabolomic data were uploaded to MetaboLights (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/metabolights) with the following IDs: feces, MTBLS10234; ovary, MTBLS10265; serum, MTBLS10260; intestine, MTBLS10251.

Microbial diversity analysis

Sample collection, DNA extraction, and illumina MiSeq sequencing

Fresh fecal samples of all rats were placed into 2 ml sterile EP tubes, rapidly snap-frozen using liquid nitrogen, and stored at − 80 °C until further use. Total DNA was extracted from fecal samples using the E.Z.N.A.® soil DNA Kit (Omega Bio-Tek, Norcross, GA, U.S.) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The DNA concentration and purity were assessed using a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA). The V3–V4 regions of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene were amplified from the extracted DNA using primers 338F (5′-ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCAG-3′) and 806R (5′-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3′)35. PCR was performed to amplify bacterial 16S rRNA genes. Agarose gel electrophoresis was performed to verify the amplicon size. Amplicons were subjected to paired-end sequencing on an Illumina MiSeq sequencing platform using PE300 at Majorbio Bio-Pharm Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). The data have been deposited in the NCBI database and are publicly available under the BioProject accession number PRJNA880729 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA880729).

Amplicon sequence processing and analysis

The demultiplexed sequences were processed using FLASH software (version 1.2.7) and filtered using Fastp software (version 0.19.6) to improve quality (version 0.19.6)36,37. Denoising was then performed using the DADA2 plugin in Qiime238,39. The DADA2 denoised sequences were Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs). To reduce the effects of sequencing depth on microbial diversity, including alpha and beta diversities, the number of sequences in each sample was rarefied to 42,053. Taxonomic assignment of ASVs was conducted using the naive Bayes consensus taxonomy classifier implemented in Qiime2 and the SILVA 16S rRNA database (version 138). Subsequent analyses of the 16S rRNA microbiome were performed using the free online Majorbio Cloud Platform (cloud.majorbio.com).

Western blotting

Ovarian tissues were lysed in RIPA buffer (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) containing PMSF, homogenized on ice, and centrifuged at 13,000g for 10 min at 4 °C. Protein concentrations were measured using the BCA assay (Beyotime). Equal amounts of protein (20 µg) were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes. After blocking, membranes were incubated overnight at 4 °C with 1:1000 diluted primary antibodies against STAR, CYP4B1, CYP19A1, HSD3B2, and Actin (all from Proteintech, Wuhan, Hubei, China), followed by HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (ZSGB-Bio, 1:10,000) for 1 h at room temperature. Protein bands were visualized using WesternBright ECL HRP substrate (Advansta, San Jose, California, USA) and a Vilber Fusion image system (Fusion FX5 Spectra, France).

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

Total RNA from cecum and ovarian tissues was extracted with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, USA) and quantified using a NanoDrop2000 (Thermo, USA). cDNA was synthesized from 1 µg RNA using a reverse transcription kit (Roche, Germany). Gene-specific primers (TaKaRa, Dalian, China) are listed in Table S1.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using Prism (version 9.0, GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). Most of the continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) with the exception of chao1 that was expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Statistical data were analyzed using the Mann–Whitney U test and Student’s t-test. Spearman’s rho correlation test was performed on the differential gut microbiota and DEMs in the fecal, cecum, serum, and ovarian metabolomes to investigate their correlation. The statistical significance level was set at p < 0.05. Moreover, correlation analysis between the key hormones that reflect the severity of PCOS and the differential metabolites of the four sample types was performed using Pearson correlation analysis.

Results

The PCOS rat model was successfully established through DHEA subcutaneous injection

After 21 d of DHEA or sesame oil treatment, no significant differences in weight were observed between the two groups (Fig. S1). First, the validity of the PCOS model was assessed. Histopathological structures of the ovaries in both groups were examined. The results revealed that ovaries from the control group exhibited normal morphology, with follicles at different stages of development, normal thickness of the theca and granulosa cells, and a normal corpus lutea count. In contrast, the PCOS group displayed a significant reduction in the number of corpora lutea (9.86 ± 1.58 vs. 1.50 ± 0.71 p < 0.001), a thinner granulosa layer (87.97 ± 0.40 vs. 52.33 ± 0.60, p = 0.003), less antral follicles (5.43 ± 0.78 vs. 2.88 ± 0.58 p = 0.016), and significantly higher counts of follicles (1.14 ± 0.40 vs. 4.67 ± 0.60 p < 0.001). The counts of secondary and atretic follicles in both groups were comparable. These observations indicated that DHEA treatment successfully prevented ovulation and follicular dysplasia (Fig. S2A). Moreover, we also noticed the obviously disturbed estrous cycles in the PCOS group, as daily examination of vaginal smears from days 32 to 39 indicated that rats from the Control group possessed a normal estrus cycle, while rats from the PCOS group remained entirely acyclic and consistently in metestrus/diestrus cycles (Fig. S2B). The endocrine function of both groups was confirmed by measuring serum levels of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), luteinizing hormone (LH), testosterone (T), estradiol (E2), and insulin (INS) in serum samples. In comparison to the Control group, DHEA injection led to a significant increase in the levels of serum testosterone in the PCOS group (1.48 ± 0.09 vs. 17.35 ± 1.54 p < 0.001). However, there were no significant changes in the FSH or LH insulin levels. Notably, the level of serum E2 decreased significantly in the PCOS group (61.10 ± 4.23 vs. 44.71 ± 3.88, p = 0.009) (Fig. S2C). Collectively, these findings indicated the successful establishment of a DHEA-induced rat model of PCOS characterized by abnormal ovarian morphology, disrupted estrous cycles, and severe endocrine dysfunction.

The DHEA-induced PCOS model rats exhibit significant alterations in their gut microbiomes

Subsequently, we sought to determine if PCOS rats displayed disturbances in the gut microbiome. Stool samples from 11 control rats and 14 PCOS rats were collected for 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequencing to compare gut microbial communities between the groups. We identified 2,381,592 high-quality reads in 25 fecal samples, with an average length of 421 bp. These reads were clustered into 2920 ASVs at 97% sequence similarity. The Venn diagram indicated that 1181 ASVs were common to the PCOS and control groups, whereas 607 and 1132 genera were unique to the control subjects and PCOS rats, respectively (Fig. S3).

Next, the within-sample α-phylogenetic diversity indexes, including microbial community richness (Ace, Sobs and Chao1) and phylogenetic diversity (PD), were compared (Fig. 2A). We observed that both microbial richness and phylogenetic diversity were significantly increased in the PCOS group. Furthermore, the β-diversity was used to determine the degree by which the gut microbiota within PCOS subjects differed from those within controls. Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) of unweighted UniFrac indicated an obvious difference in the gut microbial community composition between the PCOS and control groups (Fig. 2B). Based on the community abundance data, the Wilcoxon rank-sum test of the species between the two groups of sample microbial communities was performed, the significance level of the microbial abundance at the genus level was evaluated, and the difference between the two groups was determined (Fig. 2C,D). Among the top 10 genera with significant differences, Bacillus and Staphylococcus exhibited significantly lower abundance in the PCOS group compared to that in the control group, and Allobaculum and Corynebacterium were significantly higher in abundance in the PCOS group compared to that in the control group (Fig. 2D). Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) demonstrated that Allobaculum, Corynebacterium, and Jeotgalicoccus were the most important characteristic genera in the PCOS group compared to those in the control group (Fig. 2E). In summary, we observed that the stool of rats with PCOS was associated with a disturbance in the gut microbiome characterized by alterations in specific genera, including Bacillus, Staphylococcus, Allobaculum, and Corynebacterium.

Characteristics of gut microbiota between the two groups. (A) Microbial community richness indicated by the within-sample α-phylogenetic diversity indexes including Ace, Sobs and Chao1 and Phylogenetic diversity (Pd). (B) The principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) of unweighted UniFrac analysis on the gut microbial community compositions of PCOS and control groups. (C) The proportion of community abundances of gut microbiota composition at the genus level in the PCOS and control groups. (D) The column chart of top 10 species with significant difference at genus level. The left Y-axis represents the name of gut flora, the X-axis represents the relative abundance of the genus in different groups, and the right Y-axis represents the confidence interval and p value. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01. (E) Linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe) pinpointing the top 30 key gut microbiota (Genus) which contribute significantly to the discrimination between the PCOS and control groups. The linear discriminant analysis (LDA) score, displayed on the X-axis, represents the effect size and ranking of each differential microbiota at genus level.

General characteristics of differentially expressed metabolites in stool, cecum, serum, and ovaries from PCOS and control rats

Large-scale metabolomic analysis was performed on the metabolites of fecal, cecum, serum, and ovary samples from both groups. Heat maps depicting the Spearman’s correlation between metabolites in the fecal (Fig. S4A), cecum (Fig. S4B), serum (Fig. S4C), and ovarian (Fig. S4D) metabolomes indicated that the samples in each group were significantly correlated with each other. Principal component analysis (PCA) was used to compare changes in fecal metabolites and to identify significant differences in metabolites between the Control and PCOS groups. PCA results demonstrated that the overall microbial composition was significantly different between the two groups. Furthermore, the resulting orthogonal projections to the latent structure-discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) score plot also indicated a significant separation between the two groups. Each sample was within a 95% confidence interval. The results of the permutation tests confirmed that the OPLS-DA model was reliable and did not overestimate (Fig. S5A). Similar results were observed for the cecal (Fig. S5B), serum (Fig. S5C), and ovary metabolomes (Fig. S5D). In summary, the above results indicated that the fecal, cecum, serum, and ovarian metabolic phenotypes of the PCOS group were significantly different from those of the control group.

Next, the differential metabolites in the fecal, cecum, serum, and ovary samples were identified between the two groups. Volcano plots of the DEMs detected in the four tissues are presented (Fig. 3A–D). We identified 202 fecal DEMs (75 upregulated and 127 downregulated) considered as being responsible for discriminating the Control and PCOS groups with the parameters including FC < 1 and p < 0.05 (Fig. 3A). With the same parameters, a total of 211 serum DEMs (100 upregulated and 111 downregulated, Fig. 3B), 198 cecum DEMs (118 upregulated and 80 downregulated, Fig. 3C), and 254 ovary DEMs (106 upregulated and 48 downregulated, Fig. 3D) were identified. We also depicted the heatmaps of these DEMs identified with Variable Importance Plot (VIP) values of greater than 1.0 and p values of less than 0.05 (Fig. 3E–H) that exhibited distinct expression patterns of DEMs between PCOS and Control group in all four types of samples. Noticeably, a remarkable percentage of these DEMs were predominantly related to sex hormone metabolism such as 17α-Hydroxyprogesterone, Ethyltestosterone, Androsterone sulfate, Pregnanetriolone, trans-Dehydroandrosterone, and Pregnenolone.

General characteristics of differential metabolites in stool, cecum, serum and ovarian metabolomes in the PCOS and control groups. (A–D) Volcano plots of DEMs in the stool, serum, cecum, and ovary metabolomes. The blue and red dots indicate upregulated and downregulated DEMs in these four types of samples, respectively. (Control, n = 9; PCOS, n = 10). (E–H) Heatmap of DEMs (VIP > 1, p < 0.05) between both groups in the stool, serum, cecum, and ovary metabolomes. The rows represents the metabolites, and the columns indicate the samples of each group. The color represents the relative abundance of the DEMs in samples. The VIP bar graph of DEMs is listed on the right. The size of the VIP value represents the contribution value of the metabolite to the difference between the groups. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

The key pathway in which the fecal, cecum, serum, and ovarian DEMs are involved

To investigate the functional implications of the identified DEMs across the four sample types, we conducted functional pathway analysis using the KEGG database (Fig. 4). As expected, the pathways involving DEMs in the four distinct samples exhibited many similarities that were centered on lipid metabolism. KEGG enrichment analysis of DEMS in these four metabolomes demonstrated that the enriched pathways of these metabolomes were primarily centered on ovarian steroid hormone biosynthesis, ovarian steroidogenesis, cortisol synthesis and secretion, cholesterol metabolism, and bile secretion (Fig. 5). These findings suggest that subcutaneous injections of DHEA into rats exert a notably similar effect on the metabolism of these four samples, thus highlighting their association with ovarian steroid hormone metabolism.

Correlations of fecal, cecum, serum, and ovarian DEMs with gut differential bacteria

Pearson correlation analysis was performed on the top 20 differential bacteria (at the genus level) of the gut microbiota and the ovarian, serum, cecum, and fecal DEMs (top 20) (Fig. 6) to identify their correlations. Surprisingly, we noticed that there was a close correlation between the bacteria of the gut microbiota and the top DEMs in the fecal, cecum, serum, and ovarian metabolomes, with similar fecal bacteria such as Bacccillus, Akkermansia, Jeotgalicoccus, and corynebacterium exhibiting the most significant associations with the top DEMS in these four different types of tissues. There were also multiple differential gut microbiota such as Bacillus, Faecalibaculum, Coriobacteriaceae, and Adlercreutzia, that exhibited statistically significant associations with serum PCOS-correlated hormones such as estrogen, luteinizing hormone, and testosterone (Fig. 7). Moreover, we were surprised to observe that the majority of top 20 DEMs in ovarian, serum, and cecum metabolomes exhibited statistically significant close correlations with E2, despite anatomical distance between the ovaries and the gut (Fig. S6), while insulin and testosterone exhibited significant correlations with 10 of the top DEMs in the cecum and feces metabolomes, respectively. These findings suggest that in the PCOS rat model, there is a close interplay between the gut microbiota and the host fecal, cecum, serum, and ovarian metabolomes. Additionally, the types of bacteria significantly associated with the DEMs in these four metabolome categories were similar.

Association between differential bacteria (at genera level) and fecal, cecum, serum, and ovarian DEMs. Heatmaps illustrating the Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient of top 20 differential bacteria (at genera level) and top 20 ovary (A), serum (B), cecum (C), and feces (D) differential metabolites. Red blocks represent positive associations between these microbial species and metabolites, while blue blocks indicate negative associations. The blocks are marked with asterisk(s) to indicate statistical significance (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001).

Association between differential gut bacteria (at genera level) and serum hormones relevant to PCOS. Spearman correlation heatmap shows the top 40 differential gut bacteria’s (at genera level) association with serum hormones relevant to PCOS including follicle stimulating hormone (FSH); luteinizing hormone (LH); testosterone (T); estrogen (E2) and insulin (INS). Red blocks indicates positive associations between these microbial species and hormones, while blue blocks represents negative associations. The blocks are marked with asterisk(s) to show statistical significance (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001).

PCOS rat model exhibits impaired intestinal integrity and disturbed ovarian steroid hormone metabolism

We examined the expression levels of mRNAs involved in ovarian steroid hormone metabolism, including Cyp4f17, Cyp4b1, and 3B-HSD in ovarian tissues (Fig. 8A), as well as CLDN2, CLDN3, TJP-1, and Occludin mRNAs in the colonic tissues of both groups (Fig. 8B) to investigate the effects of DHEA treatment on intestinal integrity and ovarian steroid hormone metabolism. Significant differences were observed in the expression of the CYP4b1 and 3B-HSD genes. CYP4b1 expression was significantly upregulated in the PCOS group (2.792 ± 0.7390 vs. 1.000 ± 0.2440, p = 0.0439). Similarly, 3B-HSD gene expression was markedly higher in the PCOS group (5.130 ± 1.249 vs. 1.000 ± 0.1877, p = 0.0084). Other genes (CYP17a1, CYP4f17, and STAR) exhibited no significant differences. The expression of CLDN3 mRNA in colonic tissues of the PCOS group were significantly increased compared to levels in the Control group (1.00 ± 0.04 vs. 1.35 ± 0.04, p = 0.003). In comparison, the expression of Occludin mRNA decreased significantly in the PCOS group (1.00 ± 0.11 vs. 0.50 ± 0.11, p = 0.032).

DHEA treatment induce impaired intestinal integrity and disturbed ovarian steroid hormone metabolism in recipient rat’s ovary (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001). (A) The expression levels of mRNAs involved in ovarian steroid hormone metabolism (HSD3B2, CYP4B1, CYP17A, STAR) determined by real time PCR. (B) The expression levels of intercellular junction mRNA s (CLDN2, CLDN3, Occludin) in colonic tissues. (C) The expression levels of enzymes of ovarian steroid hormone metabolism (Cyp4f17, Cyp4b1, and 3B-HSD) determined by WB.

We performed WB of the ovarian tissues of both groups to determine the key enzymes involved in ovarian steroid hormone metabolism (Fig. 8C). The ovarian Cyp4b1 levels were notably elevated (1.00 ± 0.50 vs. 1.89 ± 1.36, p = 0.030), and 3B-HSD levels were significantly increased compared to those of the control group (1.00 ± 0.39 vs. 2.23 ± 1.08, p = 0.026). These results suggested that DHEA treatment affected intestinal permeability and disrupted ovarian steroid hormone synthesis.

Discussion

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a common reproductive metabolic endocrinological disorder that significantly affects reproductive function in women of childbearing age. Genetic factors such as abnormal steroid hormone metabolism, disrupted lipid metabolism, insulin resistance, and chronic ovarian inflammation as well as environmental factors are believed to contribute to the development and pathogenesis of PCOS5,9. However, pathophysiological mechanisms underlying PCOS remain unclear. Subcutaneous injection of DHEA can replicate the key features of PCOS, including hyperandrogenemia, polycystic ovarian morphology, and steroid hormone metabolic disorders, and is a commonly used method for establishing animal models of PCOS. In this study, we used this method to construct a rat model of PCOS and observed that the metabolomes of the intestine, feces, serum, and ovaries of PCOS model rats exhibited similar disturbances, particularly in regard to lipid and ovarian steroid hormone metabolism. Moreover, differentially expressed metabolites were significantly correlated with differentially expressed gut microbiota.

Hyperandrogenism and subsequent multisystem metabolic disturbances are considered pivotal factors in the pathogenesis of PCOS9. Hyperandrogenism is a characteristic pathological feature of PCOS5. The 2003 Rotterdam Consensus listed clinical or biochemical hyperandrogenism as a diagnostic criterion for PCOS40. Previous studies have demonstrated that many PCOS-like manifestations such as polycystic ovaries and ovulatory dysfunction can be successfully induced in rats by subcutaneous administration of dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA)23. Furthermore, two-thirds of patients with PCOS exhibit ovarian functional hyperandrogenism. When cultured ex vivo for long periods, cells extracted from the ovaries of patients with classic PCOS exhibit overactive intrinsic steroid hormone synthesis and overexpression of cytochrome P450c179. Previous mass spectrometry-based metabolomic studies have revealed disturbed steroid, amino acid, carbohydrate, lipid, glycerophospholipid, sphingolipid, and fatty acid metabolism in the serum, urine, follicular fluid, and even feces of patients with PCOS11,41. Consistent with these findings in clinical samples, in our study, we observed a similar metabolomic disturbance in the feces, cecum, serum, and ovarian tissue of PCOS rat models, indicating that the disturbed steroid hormone metabolism subsequent to hyperandrogenism involves multiple organs and tissues.

In the current study, we successfully established a PCOS rat model through subcutaneous DHEA injection and investigated the untargeted metabolomes of the feces, cecum, serum, and ovarian tissue as well as the gut microbiota via 16S rRNA gene sequencing in the PCOS and Control groups. Our findings revealed that all four sample types in the PCOS group exhibited similar disturbances in steroid hormones and lipid metabolism, and these may be the most essential metabolic pathways involved in the regulation of PCOS pathogenesis. Furthermore, a substantial proportion of the DEMs exhibited a close association between the bacteria of the gut microbiota and DEMs in fecal, cecum, serum, and ovarian metabolomes, with similar fecal bacteria such as Bacillus, Akkermansia, and Corynebacterium exhibiting the most significant associations with the top DEMS in these four different types of tissues, suggesting a close correlation between gut dysbiosis and disturbed ovarian steroid hormone metabolism, particularly sex hormone metabolism. Several mechanisms may explain these associations: gut microbes influence hormone metabolism through metabolites such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs)42; for instance, Faecalibaculum produces butyrate, which supports intestinal barrier integrity and lipid metabolism, and its reduced abundance in PCOS may contribute to lipid disturbances43. Microbial metabolites also regulate host immunity, inflammation, and the gut–brain axis, indirectly affecting hormone synthesis43. Clinical studies similarly show altered microbial profiles in PCOS patients, including reduced Faecalibacterium, Bacteroides, and Lachnospira, and an increased Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio, consistent with our animal model44. Conversely, sex hormones themselves may shape gut microbial communities, with estrogen favoring Bacteroidetes via ERβ signaling, whereas lower estrogen promotes Firmicutes expansion45. Moreover, SCFAs can act on G-protein–coupled receptors (e.g., GPR43) to regulate endocrine activity43. Collectively, these bidirectional interactions between hormones and gut microbiota highlight novel mechanistic insights into PCOS and may inform strategies for early diagnosis and targeted interventions.

In 2017, Insenser observed that the diversity and composition of the gut microbiota in young adults was influenced by a combination of multiple factors, including sex, sex hormone concentrations, and obesity46. In a study conducted by Zhou Liu examining the gut microbiota and fecal metabolites in obese PCOS patients and non-PCOS obese women, there was a negative correlation between testosterone (T) levels and the abundance of Prevotella, a positive correlation between serum luteinizing hormone (LH) levels and the abundance of Bifidobacterium, and a negative correlation between serum estradiol (E2) levels and the abundance of Eubacterium hallii and Fusicatenibacter11, thus highlighting the impact of sex hormones on gut dysbiosis.

Previous studies have demonstrated that inflammatory and adipokine pathways are also altered in PCOS. In DHEA-induced PCOS models, serum TNF-α concentrations were significantly elevated compared with controls, accompanied by increased TNF-α mRNA and protein expression in local tissues such as the ovary, visceral adipose tissue, and skeletal muscle47. Similarly, animal models of PCOS, particularly those established through androgen exposure, exhibit elevated serum leptin levels and altered ovarian leptin expression, with both leptin and its receptor (Ob-R) showing dysregulation in ovarian tissue48. These findings are consistent with clinical observations in women with PCOS, where leptin levels correlate positively with obesity and insulin resistance49. Collectively, these data highlight the contribution of TNF-α and leptin to the inflammatory and metabolic disturbances characteristic of PCOS.

Conversely, mounting evidence has revealed the extensive influence of the disturbed gut microbiota on the functioning and metabolism of various systems or organs, including immunity, blood circulation, brain, and liver21,22,50,51. With respect to the ovary, Qi observed a significant upregulation of B. vulgatus in patients with PCOS, and treatment of wild-type mice with B. vulgatus led to ovarian dysfunction and exacerbated PCOS through alterations in bile acid metabolism and elevated interleukin-22 levels14. Additionally, Li reported that treatment with inulin-enriched synbiotic yogurt led to changes in the gut microbiota community and bile acid profiles in PCOS mice, resulting in amelioration of the PCOS phenotype and partial improvement in reproductive functions within the PCOS model. Their findings underscore the intricate interplay between sex hormone metabolism and the gut microbiota in the context of obesity and PCOS52.

Our evidence suggests that a significant portion of the DEMs in the fecal, serum, cecum, and ovarian metabolomes of the PCOS and Control groups were predominantly clustered within pathways related to steroid hormone and lipid metabolism. These DEMs are closely associated with the gut microbiota. Our combination of alpha and beta diversity analyses revealed an alteration in the intestinal flora of rats with a PCOS-like phenotype, consistent with a previous study that reported similar results in obese patients with PCOS11. One hypothesis has been reported that gut dysbiosis can compromise intercellular tight junctions, leading to impaired gut barrier integrity, increased intestinal permeability, and the release of excessive lipopolysaccharide (LPS) into the bloodstream. This, in turn, results in elevated levels of proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-alpha and INF-gamma in the serum50. The local gut microbiota themselves, their metabolic by-products, or the inflammatory factors they provoke may enter the bloodstream through damaged intestinal epithelial cell interconnections and eventually reach the ovaries, thereby influencing their metabolism and functionality53, and this, to some extent, is consistent with the abnormal expression of tight junction-correlated proteins in the intestine of PCOS rats.

However, previous literature indicates that the impact of gut microbiota on ovarian function and metabolism is mediated through the gut microbiota–hypothalamus–pituitary–ovary/adrenal axis. Notably, androgens in females are primarily synthesized in the ovaries and adrenal cortex, whereas both the adrenal glands and ovaries are subject to the regulation and control of the hypothalamus-pituitary axis54,55. Evidence suggests that dysbiosis of the gut microbiota can perturb homeostasis of the hypothalamus–pituitary–adrenal axis, particularly under stressful conditions. Furthermore, the hypothalamus can receive neuroendocrine signals from the gut microbiota, thereby influencing the metabolic balance of hormones such as gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) via the hypothalamus–pituitary–ovary axis, ultimately disrupting the homeostasis of sex hormone metabolism56. Our findings also revealed disruptions in arginine and several other amino acid metabolites in the serum and ovaries of the PCOS group mice. It has also been reported that l-arginine supplementation can alleviate hormonal imbalances in rodents. Notably, arginine also serves as a precursor of nitric oxide that participates in the neuroendocrinological regulation of sex hormone metabolism and manipulates GnRH neuronal function.

It is worth noting that the role of the gut microbiota in the development of PCOS is highly unlikely to be the initiating factor. A previous study demonstrated that though the temporal clearance of gut microbiota with antibiotics in DHEA-injected rats could not prevent the occurrence of PCOS, transplanting the gut microbiota from “PCOS” rats into pseudo-germ-free rats recapitulated the metabolomic disturbances observed in PCOS that encompass hepatic glucolipid metabolism and reproductive hormone regulation, indicating the pivotal role that gut microbiota may play in exacerbating PCOS rather than the initiating it20. Similarly, the gut microbiota has been implicated as a potential mediator in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes and obesity, rather than functioning solely as a causal factor or a consequence. Although the patterns of dysbiosis observed in PCOS differ from those in type 2 diabetes and obesity, chronic low-grade “metabolic” inflammation (metainflammation), both local and systemic, has been recognized as a key driver of insulin resistance and the progression of both conditions16,57,58,59. Zarrinpar et al. observed that depleting the gut microbiota through antibiotic administration led to a decrease in fasting blood glucose (FBG) levels and a glucose surge during the glucose tolerance test (GTT) in normal mice. In the DHEA + antibiotic group, the removal of the gut microbiome and antibiotics resulted in decreased levels of serum testosterone (T) and free androgen index (FAI). However, the DHEA and DHEA + antibiotic groups exhibited similarly high blood glucose curves. This implies that hyperandrogenism may contribute to glucose intolerance independently of the gut microbiome 60.

This study utilized a relatively large sample size and first examined multiple types of specimens, including feces, colon, blood, and ovaries, in a PCOS rat model, and we also sequenced the gut microbiota. This study provides preliminary evidence for the potential involvement of the gut microbiota, metabolites, and metabolic disturbances in the colon, blood, and ovaries in the pathogenesis of hyperandrogenism in PCOS. However, the detailed molecular mechanism by which the gut–ovary axis is involved in the pathogenesis of PCOS remains unclear, and our conclusions are solely based on correlational analyses, thus presenting only weak levels of evidence and necessitating subsequent experimental validation.

Conclusion

DHEA-induced PCOS-like phenotypes in rats led to significant disruptions in gut microbiota and metabolomes across the feces, cecum, serum, and ovary, particularly affecting steroid hormone, lipid, and amino acid metabolism. DEMs in these samples such as 17α-Hydroxyprogesterone, Ethyltestosterone, Androsterone sulfate, Pregnanetriolone, trans-Dehydroandrosterone, and Pregnenolone were predominantly related to sex hormone metabolism. These DEMs were strongly correlated with those in other samples, PCOS-related hormones, and differential gut microbiota, including Bacillus, Akkermansia, Corynebacterium, and Jeotgalicoccus, suggesting a role for the gut–ovary axis in the pathogenesis of PCOS.

Data availability

The metabolomic data have been deposited in the NCBI database and are publicly available under the BioProject accession number PRJNA880729 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA880729). All other data presented in the manuscript are available on reasonable request to the corresponding authors.

Abbreviations

- PCOS:

-

Polycystic ovary syndrome

- DHEA:

-

Dehydroepiandrosterone

- DEMs:

-

Differentially expressed metabolites

- H&E:

-

Hematoxylin and eosin staining

- FSH:

-

Follicle stimulating hormone

- LH:

-

Luteinizing hormone

- T:

-

Testosterone

- E2:

-

Estrogen

- INS:

-

Insulin

- OD:

-

Optical density

- QC:

-

Quality control

- LC–MS:

-

Liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry

- PCA:

-

Principle component analysis

- OPLS-DA:

-

Orthogonal partial least squares discriminate analysis

- PMSF:

-

Phenylmethyl-sulfonyl fluoride

- PVDF:

-

Polyvinylidene difluoride

- HRP:

-

Horseradish peroxidase

- PD:

-

Phylogenetic diversity

- VIP:

-

Variable importance plot

- LDA:

-

Linear discriminant analysis

- CLDN2:

-

Claudin 2

- CLDN3:

-

Claudin 3

- HSD3B2:

-

3-Beta-hydroxy-delta(5)-steroid dehydrogenase

- CYP4B1:

-

Cytochrome P450, family 4, subfamily B, polypeptide 1

- CYP17A:

-

Cytochrome P450, family 17, subfamily A, polypeptide 1

- STAR:

-

Steroidogenic acute regulatory protein

- Cyp4f17:

-

Cytochrome P450, family 4, subfamily F, polypeptide 17

- Cyp4b1:

-

Cytochrome P450, family 4, subfamily B, polypeptide 1

- 3B-HSD:

-

Hydroxy-delta-5-steroid dehydrogenase, 3 beta- and steroid delta-isomerase 2

References

Cena, H., Chiovato, L. & Nappi, R. E. Obesity, polycystic ovary syndrome, and infertility: A new avenue for GLP-1 receptor agonists. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 105(8), e2695–e2709 (2020).

Fauser, B. C. J. M. et al. Consensus on women’s health aspects of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): The Amsterdam ESHRE/ASRM-sponsored 3rd PCOS Consensus Workshop Group. Fertil. Steril. 97(1), 28–38 (2012).

Goodarzi, M. O., Dumesic, D. A., Chazenbalk, G. & Azziz, R. Polycystic ovary syndrome: Etiology, pathogenesis and diagnosis. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 7(4), 219–231 (2011).

Moran, L. J., Misso, M. L., Wild, R. A. & Norman, R. J. Impaired glucose tolerance, type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome in polycystic ovary syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum. Reprod. Update 16(4), 347–363 (2010).

Joham, A. E. et al. Polycystic ovary syndrome. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 10(9), 668–680 (2022).

Bordewijk, E. M. et al. Metformin during ovulation induction with gonadotrophins followed by timed intercourse or intrauterine insemination for subfertility associated with polycystic ovary syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 1(1), CD009090 (2017).

Choudhury, A. A. & Rajeswari, V. D. Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) increases the risk of subsequent gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM): A novel therapeutic perspective. Life Sci. 310, 121069 (2022).

Role of metformin for ovulation induction in infertile patients with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): A guideline. Fertil. Steril. 108(3), 426–41 (2017).

Rosenfield, R. L. & Ehrmann, D. A. The pathogenesis of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): The hypothesis of PCOS as functional ovarian hyperandrogenism revisited. Endocr. Rev. 37(5), 467–520 (2016).

Diamanti-Kandarakis, E., Kandarakis, H. & Legro, R. S. The role of genes and environment in the etiology of PCOS. Endocrine 30(1), 19–26 (2006).

Zhou, L. et al. Correlation between fecal metabolomics and gut microbiota in obesity and polycystic ovary syndrome. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 11, 628 (2020).

Guo, Y. et al. Association between polycystic ovary syndrome and gut microbiota. PLoS ONE 11(4), e0153196 (2016).

Lindheim, L. et al. Alterations in gut microbiome composition and barrier function are associated with reproductive and metabolic defects in women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): A pilot study. PLoS ONE 12(1), e0168390 (2017).

Qi, X. et al. Gut microbiota-bile acid-interleukin-22 axis orchestrates polycystic ovary syndrome. Nat. Med. 25(8), 1225–1233 (2019).

Farzi, A., Hassan, A. M., Zenz, G. & Holzer, P. Diabesity and mood disorders: Multiple links through the microbiota-gut-brain axis. Mol. Asp. Med. 66, 80–93 (2019).

Scheithauer, T. P. M. et al. Gut microbiota as a trigger for metabolic inflammation in obesity and type 2 diabetes. Front. Immunol. 11, 571731 (2020).

Gurung, M. et al. Role of gut microbiota in type 2 diabetes pathophysiology. EBioMedicine 51, 102590 (2020).

Agus, A., Clément, K. & Sokol, H. Gut microbiota-derived metabolites as central regulators in metabolic disorders. Gut 70(6), 1174–1182 (2021).

Fan, Y. & Pedersen, O. Gut microbiota in human metabolic health and disease. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 19(1), 55–71 (2021).

Han, Q., Wang, J., Li, W., Chen, Z.-J. & Du, Y. Androgen-induced gut dysbiosis disrupts glucolipid metabolism and endocrinal functions in polycystic ovary syndrome. Microbiome 9(1), 101 (2021).

Erttmann, S. F. et al. The gut microbiota prime systemic antiviral immunity via the cGAS-STING-IFN-I axis. Immunity 55(5), 847–861 (2022).

Liu, Y. et al. Proteomics analysis of the gut-brain axis in a gut microbiota-dysbiosis model of depression. Transl. Psychiatry 11(1), 568 (2021).

Zhang, H. et al. High-fat diets exaggerate endocrine and metabolic phenotypes in a rat model of DHEA-induced PCOS. Reproduction 151(4), 431–441 (2016).

Carmina, E. et al. Female pattern hair loss and androgen excess: A report from the multidisciplinary androgen excess and PCOS Committee. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 104(7), 2875–2891 (2019).

Caldwell, A. S. L. et al. Characterization of reproductive, metabolic, and endocrine features of polycystic ovary syndrome in female hyperandrogenic mouse models. Endocrinology 155(8), 3146–3159 (2014).

Ataabadi, M. S., Bahmanpour, S., Yousefinejad, S. & Alaee, S. Blood volatile organic compounds as potential biomarkers for poly cystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS): An animal study in the PCOS rat model. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 226, 106215 (2023).

Shorr, E. A new technic for staining vaginal smears: III, a single differential stain. Science 94(2449), 545–546 (1941).

Marcondes, F. K., Bianchi, F. J. & Tanno, A. P. Determination of the estrous cycle phases of rats: Some helpful considerations. Braz. J. Biol. 62(4A), 609–614 (2002).

Liu, T. et al. Comprehensive metabolomic profiling of cord blood and placental tissue in surviving monochorionic twins complicated by twin–twin transfusion syndrome with or without fetoscopic laser coagulation surgery: A retrospective cohort study. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 10, 786755 (2022).

Lin, F., Ma, Y., Pan, A., Ye, Y. & Liu, J. Quantification of usaramine and its N-oxide metabolite in rat plasma using liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry. J. Anal. Toxicol. 46(5), 512–518 (2022).

Ren, W., Yin, L., Zhang, G., Zhai, T. & Huang, J. Comparison of LC-MS(3) and LC-MRM method for quantifying voriconazole and its application in therapeutic drug monitoring of human plasma. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland) 27(17), 5609 (2022).

Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Sato, Y., Matsuura, Y. & Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG: Biological systems database as a model of the real world. Nucleic Acids Res. 53(D1), D672–D677 (2025).

Kanehisa, M. Toward understanding the origin and evolution of cellular organisms. Protein Sci. 28(11), 1947–1951 (2019).

Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28(1), 27–30 (2000).

Bukin, Y. S. et al. The effect of 16S rRNA region choice on bacterial community metabarcoding results. Sci. Data 6, 190007 (2019).

Chen, S., Zhou, Y., Chen, Y. & Gu, J. fastp: An ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 34(17), i884–i890 (2018).

Magoč, T. & Salzberg, S. L. FLASH: Fast length adjustment of short reads to improve genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 27(21), 2957–2963 (2011).

Callahan, B. J. et al. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 13(7), 581–583 (2016).

Bolyen, E. et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 37(8), 852–857 (2019).

Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil. Steril. 81(1), 19–25 (2004).

Rajska, A., Buszewska-Forajta, M., Rachoń, D. & Markuszewski, M. J. Metabolomic insight into polycystic ovary syndrome—An overview. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21(14), 4853 (2020).

Yang, T. et al. Characterization of the gut microbiota in polycystic ovary syndrome with dyslipidemia. BMC Microbiol. 24(1), 169 (2024).

He, S. et al. The gut microbiome and sex hormone-related diseases. Front. Microbiol. 12, 711137 (2021).

Siddiqui, R., Makhlouf, Z., Alharbi, A. M., Alfahemi, H. & Khan, N. A. The gut microbiome and female health. Biology 11(11), 1683 (2022).

Yoon, K. & Kim, N. Roles of sex hormones and gender in the gut microbiota. J. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 27(3), 314–325 (2021).

Insenser, M. et al. Gut microbiota and the polycystic ovary syndrome: Influence of sex, sex hormones, and obesity. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 103(7), 2552–2562 (2018).

Liu, K. et al. Short-chain fatty acid-butyric acid ameliorates granulosa cells inflammation through regulating METTL3-mediated N6-methyladenosine modification of FOSL2 in polycystic ovarian syndrome. Clin. Epigenet. 15(1), 86 (2023).

Prado Correia, L. E. et al. IGF-1R and leptin expression profile and the effects of metformin treatment on metabolic and endocrine parameters in PCOS mice. Biomed. Res. Int. 2017, 9058307 (2017).

Wang, J. et al. Correlation between leptin and IFN-γ involved in granulosa cell apoptosis in PCOS. Gynecol. Endocrinol. Off. J. Int. Soc. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 36(12), 1051–1056 (2020).

Stevens, B. R. et al. Increased human intestinal barrier permeability plasma biomarkers zonulin and FABP2 correlated with plasma LPS and altered gut microbiome in anxiety or depression. Gut 67(8), 1555–1557 (2018).

Wastyk, H. C. et al. Gut-microbiota-targeted diets modulate human immune status. Cell 184(16), 4137–4153 (2021).

Li, T. et al. Yogurt enriched with inulin ameliorated reproductive functions and regulated gut microbiota in dehydroepiandrosterone-induced polycystic ovary syndrome mice. Nutrients 14(2), 279 (2022).

Li, J.-Y. et al. Sex steroid deficiency-associated bone loss is microbiota dependent and prevented by probiotics. J. Clin. Investig. 126(6), 2049–2063 (2016).

Stuchbery, R., McCoy, P. J., Hovens, C. M. & Corcoran, N. M. Androgen synthesis in prostate cancer: Do all roads lead to Rome?. Nat. Rev. Urol. 14(1), 49–58 (2017).

Markle, J. G. M. et al. Sex differences in the gut microbiome drive hormone-dependent regulation of autoimmunity. Science (New York, NY) 339(6123), 1084–1088 (2013).

De Palma, G. et al. Microbiota and host determinants of behavioural phenotype in maternally separated mice. Nat. Commun. 6, 7735 (2015).

Qin, J. et al. A metagenome-wide association study of gut microbiota in type 2 diabetes. Nature 490(7418), 55–60 (2012).

Karlsson, F. H. et al. Gut metagenome in European women with normal, impaired and diabetic glucose control. Nature 498(7452), 99–103 (2013).

Le Chatelier, E. et al. Richness of human gut microbiome correlates with metabolic markers. Nature 500(7464), 541–546 (2013).

Zarrinpar, A. et al. Antibiotic-induced microbiome depletion alters metabolic homeostasis by affecting gut signaling and colonic metabolism. Nat. Commun. 9(1), 2872 (2018).

Funding

This study was financially supported by the National Natural Science Youth Fund (Grant No. 82205177), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (second class of general program, Grant No.2021M700624), Special Funding for Chinese Postdoctoral Research Projects (16th batch, Grant No.2023T160769), the Sasakawa Japan-China Medical Fellowship Program (Grant No.4408), Yingcai Scheme of Chengdu Women’s and Children’s Central Hospital (Grant No. 2023004), the Chongqing Natural Science Foundation Key Project (Grant No.CQYC201903089), and the program of Inheritance and Innovation of Traditional Chinese Medicine in Chongqing (Chongqing Traditional Chinese Medicine (2022)No.33).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Zhi Chen conceptualized the study and performed the experiments. Zhi Chen and Tianjiao Liu analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript. Aolei Lin, Meiao Tan, Qiongqiong Lu, Wei Li, Sisi Tang, Junyu Feng, Cong Hou, Yu Zhu, and Mengxue Xu processed the samples and collected the data. Ming Xia supervised the project and revised the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, Z., Lu, Q., Lin, A. et al. Gut–ovary axis and multiomic insights into PCOS in a DHEA-induced rat model. Sci Rep 16, 1191 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30862-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30862-0