Abstract

Diabetic retinopathy (DR) stands as a leading cause of global blindness. Early identification and prompt treatment are essential to prevent vision impairment caused by DR. Manual screening of retinal fundus images is challenging and time-consuming. Additionally, in low-income countries, there is a significant gap between the number of DR patients and ophthalmologists. Currently, machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) are becoming a viable alternative to traditional DR screening techniques. However, DL suffers a major limitation in resource-constrained devices because of its large model size and substantial computational demands. Knowledge distillation is a prominent technique for creating lightweight models, effectively transferring knowledge from a larger, complex model to a smaller, more efficient one without significant loss in performance. Therefore, in this research, a lightweight student model is proposed, which follows the MobileNet architectural design by utilizing depthwise separable convolutions. This design ensures efficient performance suitable for edge device deployment. For binary classification, our proposed model achieved an accuracy, precision, and recall of 98.38% on the APTOS 2019 dataset, whereas the proposed model achieved an accuracy of 93.03% for ternary classification on APTOS 2019.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Diabetic Retinopathy (DR), a microvascular complication of diabetes mellitus, has emerged as a leading cause of blindness among working-age adults (20–74 years) worldwide1,2. According to the International Diabetes Federation (IDF), 451 million adults (18–99 years old) have diabetes worldwide, and by 2045, that number is expected to reach 693 million3,4. Approximately half (49.7%) of people living with diabetes remain undiagnosed, significantly delaying critical ophthalmologist interventions5. Among diagnosed patients, global estimates indicate that 34.6% develop DR, with 10.2% progressing to vision-threatening stages1.

The epidemiological situation in Ethiopia reflects concerning trends, with diabetes prevalence ranging from 2.0% to 6.5% across regions6. Recent studies report DR prevalence of 19.48% among Ethiopian diabetic patients, with 10.7% having vision-threatening DR (VTDR)7,8. This poses substantial public health challenges given Ethiopia’s severe ophthalmologist shortage (1:1,200,000 ratio) and limited eye care access (available to only 26% of the population)9.

Current clinical guidelines recommend that type 1 diabetics undergo initial retinal examination 5 years post-diagnosis, while type 2 diabetics require immediate screening at diagnosis10,11. However, poor compliance persists due to multifactorial barriers including limited health literacy, inadequate infrastructure, and insufficient insurance coverage12,13. The diagnostic process itself remains labor-intensive, requiring ophthalmologists to manually screen fundus images for characteristic findings, including microaneurysms, intra-retinal hemorrhages, venous beading, exudates, and neovascularization14. With only 232,866 ophthalmologists globally serving millions of potential DR cases, this manual approach creates critical bottlenecks15.

Lesions are symptoms of the severity level of DR14. Lesions can be broadly classified into four categories: soft and hard exudates (EX), hemorrhages (HM), and microaneurysms (MA). Due to the weakening of the vessel walls, MA, an early stage of DR, is identified by the appearance of tiny, round red spots on the retina. These dots have clear boundaries and are usually less than 125 micrometers in size16. On the other hand, unlike MA, HMs are recognized by the presence of large patches on the retina that have irregular edges and diameters greater than 125 micrometers. There are two forms of HM: flame and blot17. Flame refers to superficial areas, while blot indicates deeper ones. Hard EX are caused by blood leakage and appear as yellow patches on the retina. They have clear borders and span the outer layers of the retina18. Soft EX’s are observable white ovals in the retina that result from swelling of nerve fibers16. Hemorrhages and MA frequently appear as red lesions, whereas both types of EX are usually seen in white lesions. The DR lesion details are shown in Fig. 1. These lesions are critical for ML models, as they serve as the primary features from which the models learn.

Visualization of unhealthy retina with their respective lesion19: (a) Macula, (b) Fovea, (c) Hard Exudate, (d) Hemorrhages, (e) Optic Disc, (f) Abnormal Blood Vessels Growth, (g) Aneurysms, (h) Soft Exudate.

AI-enabled systems, particularly leveraging ML and DL, have become useful in automating DR screening by analyzing retinal fundus images for key lesions such as microaneurysms, hemorrhages, and exudates20. Among these, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) have demonstrated remarkable success, offering superior diagnostic accuracy, faster processing, and greater consistency compared to traditional manual screening methods, thereby reducing dependency on specialized ophthalmologists21,22. These advancements facilitate large-scale, cost-effective screening programs, making them especially valuable in resource-limited settings like Ethiopia, where infrastructure and personnel constraints hinder traditional approaches23.

However, despite their transformative potential, existing AI models face significant challenges, including large model sizes, high computational demands, and excessive memory footprints. These limitations hinder real-time usability, particularly on edge devices such as portable fundus cameras, mobile health platforms, or tele-ophthalmology setups, resulting in high energy consumption20. While tele-ophthalmology initiatives in Africa have provided partial solutions, delays persist due to the need for centralized professional interpretation of images24. Overcoming these barriers is critical for deploying AI-enabled DR screening in remote, low-resource environments.

This study addresses these challenges by developing a lightweight model for DR screening. By bridging the gap between AI advancements and practical deployment constraints, this research contributes to clinical practice in diabetes related vision care. To address these limitations, our research leverages knowledge distillation to develop a lightweight student model that achieves good diagnostic performance while significantly reducing computational requirements and model complexity. This makes the proposed solution well-suited for deployment in real-world, resource-constrained environments, thereby facilitating accessible and scalable DR screening.

The remaining sections of this paper are organized as follows. Section 2 provides an exploration of the related works. Section 3 discusses the methodology employed in our research. Section 4 presents the experimental setup, result analysis, and performance comparison. In Section 5, highlights the contributions of the proposed models. Finally, Section 6 summarizes the key findings and challenges and outlines future directions for further research.

Related work

DR screening is an active research area focused on finding better techniques to assist physicians in diagnosing DR. As a result, several research papers have been published on DR screening, particularly in the context of binary and multi-class classification.

Anoop et al.25 and Ishtiaq et al.26 employed custom-designed CNN models for DR classification, which involve a large number of trainable parameters25,26. Ishtiaq et al.27 designed a custom CNN model to extract complex patterns of retinal lesions and used a classical ML classifier for classification. This combination of CNNs and ML classifiers improves overall performance by leveraging CNNs for feature extraction and ML classifiers for classification, despite the model’s computational intensity. The CNN models proposed by Anoop et al.25 and Ishtiaq et al.26 are resource-intensive. In contrast, Bala et al.28 developed a computationally efficient model resembling existing architectures29, using four dense convolutional blocks and employing shortcut connections, which help maintain gradients during back-propagation. This model has 1.1 million parameters, making it lighter28.

Pre-trained CNN models have also been used for binary classification of DR30,31,32,33. These models, including EfficientNet32, ResNet33, Inception-V330, and DenseNet31, are not architecturally identical but use the same fundamental CNN operations. While pre-trained models offer a substantial number of trainable parameters, training them with a relatively small number of samples raises concerns, particularly due to their high computational demands30,31,32,33. Beghriche et al.34 compared the performance of pre-trained models on DR classification, finding that fine-tuned XCeption outperformed DenseNet121 and MobileNetV234.

The integration of custom-designed CNN models with techniques like active deep learning35 and Siamese networks36 offers a robust solution for image classification, especially when data is limited. Qureshi et al.37 demonstrated active deep learning for DR classification, allowing the algorithm to select informative image patches, thereby optimizing model performance. Additionally, integrating Siamese networks with custom CNNs, along with hierarchical clustering of image patches for feature extraction, further enhances performance38. This combined approach has proven effective in overcoming data limitations and improving classification outcomes37.

Islam et al.39 employed knowledge distillation to transfer knowledge from a teacher model, a fusion of ResNet152V2 and the Swin Transformer, to a student model, XCeption, enhanced with a Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM). Despite using knowledge distillation, the teacher model remains resource-intensive, with 145.8 million parameters and 84.4 MB of memory, while the student model, although reduced, still retains 21.4 million parameters and 82 MB39.

Some studies40,41 have addressed the complexities of DR classification by re-categorizing inseparable classes, which simplifies the model design and handling of data features, improving DR grading accuracy.

The VGG model, known for its hierarchical architecture, has been extensively applied to DR classification42,43,44. Khan et al.44 enhanced VGG with stacked spatial pyramid pooling and network-in-network (NiN) layers, which improves scale invariance and non-linearity, important for identifying DR at varying image scales. However, VGG’s computational demands can cause gradient vanishing during training, prompting the use of genetic algorithms (GA) as an optimization tool, though GA is also resource-intensive45.

MobileNet and DenseNet offer computationally efficient alternatives for DR classification, especially in resource-constrained devices. MobileNet, designed for mobile and embedded applications, provides a lightweight option46, while DenseNet’s dense connectivity enhances supervision and reduces model complexity29,47. According to Ayala et al.48, DenseNet excels in parametric efficiency, while MobileNet’s lighter structure makes it more suitable for mobile DR screening applications. InceptionV3, with its inception modules for multi-scale lesion detection, has demonstrated efficacy in DR grading by capturing features at varying scales. Although segmentation into smaller patches improves feature extraction, it can be suboptimal due to the convolutional operations’ ability to capture localized information49,50. Advanced models such as InceptionResNetV2 and graph neural networks (GNNs) further expand DR classification capabilities51.

A novel semi-local centrality to identify influential nodes in complex networks by integrating multidimensional factors (SLCMF)52. Unlike traditional metrics, SLCMF integrates structural, social, and semantic factors, enhancing both accuracy and scalability. It employs distributed local subgraphs, redefines centrality using the average shortest path, and captures latent relationships through semantic graph embedding. On the other hand, augmentation of the binary grey wolf optimization through quantum computing methodology was used for vision-threatening DR53.

Study54 identified Lipocalin-2 (LCN2) as a key mediator of neuroinflammation in retinal ischemia-reperfusion injury, suggesting its potential as a biomarker for glaucoma. Additionally, study55 linked endocrine disruptors to diabetes through mitochondrial dysfunction, highlighting disruptions in oxidative phosphorylation and ROS generation. Technological advances include a CRDS-based breath analyzer56 for non-invasive metabolic monitoring and deep learning methods like CS-Net57 and AM-Net58for real-time ultrasound super-resolution imaging. In metabolic regulation59, emphasized the role of selenoproteins, while60 characterized pembrolizumab-induced uveitis as a treatable immune-related adverse event. Generally, these works54,55,56,57,58,59,60 underscore interdisciplinary progress in pathophysiology and precision diagnostics.

Furthermore, ML techniques offer promising accuracy for automated glaucoma detection by analyzing retinal images through preprocessing, feature extraction, and classification, providing valuable clinical support in identifying glaucomatous symptoms61. A hybrid model, ML and Nature-Inspired Model for Coronavirus (MLNI-COVID-19), combines ML and nature-inspired algorithms to enhance the classification and optimization of brain Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) scans in COVID-19 patients, demonstrating improved diagnostic accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity62. However, computational complexity remains challenging in a resource-constrained environment. Soft-computing-based gravitational search optimization is used for feature selection, to eliminate unnecessary features, enhance performance, and reduce computational complexity for glaucoma predictions63. On the other hand, a genetic algorithm-based differential evolution-based multi-objective feature selection approach is used to extract only important features64.

Methodology

Dataset

DL algorithms rely heavily on large datasets to understand image patterns that depict infections or lesions, as well as normal conditions. Training ML or DL models with substantial and high-quality datasets enhances model performance.

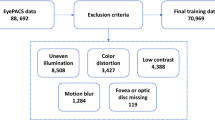

The Asian Pacific Tele-Ophthalmology Society (APTOS 2019)65 is one of the most widely used publicly available retinal fundus image datasets, published on Kaggle. It contains 3662 retinal fundus images with varying resolutions, collected from Aravind Eye Hospital in India. The dataset was specifically designed for DR screening, making it highly suitable for training and evaluating DR detection models. The class distribution of the dataset is shown in Fig. 2, providing insights into the prevalence of different DR severity levels within the dataset.

In addition to the APTOS 2019, the primary dataset was collected from local eye clinic centers, including WAGA Ophthalmology Center, Biruh Vision Specialized Eye Care Center, and KENESER Specialized Eye Clinic. 3D OCT-1 Maestro 2 and DRI OCT Triton of the Topcon funduscopic machine are used to capture retinal fundus from the eye care center. The collected images first underwent an expert-based filtering process to remove low-quality or noisy data. In the second stage, the remaining images were independently annotated by two experienced ophthalmologists. The dataset is categorized into three classes: No DR (normal retinal fundus), NPDR (non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy), and PDR (proliferative diabetic retinopathy). The class distribution is presented in Fig. 2.

The samples of retinal fundus images for each class are shown in Fig. 3, highlighting the lesions or features that distinguish one class from another.

Severity level of diabetic retinopathy65: (a) No DR; (b) NPDR; (c) PDR.

Data preprocessing

The image pre-processing steps involve noise removal, quality enhancement, and preparation of retinal fundus images to be suitable for the model.

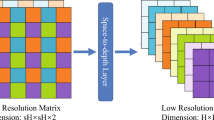

Retinal fundus images often contain black borders around the actual retina, which do not contribute useful features for class differentiation. To address this, the cropping process converts the image to grayscale, applies a threshold (set to 7) to create a binary mask, and retains only the areas with pixel values above the threshold, effectively removing irrelevant dark regions66. Additionally, a bi-linear interpolation down-scaling algorithm is used to reduce computational load and memory requirements, while adjusting the image size to fit the model’s input size. Since fundus images are typically in RGB format, all channels are retained to capture comprehensive features, although the green channel is often most useful for highlighting blood vessels. Furthermore, contrast-limited adaptive histogram equalization (CLAHE) with a clipLimit of 2.0 and tileGridSize of (8, 8) is applied channel-wise to enhance the contrast of the image. CLAHE improves primary contrast, making features in the retinal image more visible and easier for the model to analyze. The pre-processing techniques are illustrated in Fig. 4 and Algorithm 1

The dataset was initially split into two subsets: 85% of the pre-processed data as the training dataset and 15% as the testing dataset. The training dataset was then further divided into 85% as the training set and 15% as the validation set. Following the data splitting steps, data augmentation was applied on the training set to enhance dataset diversity, thereby improving model generalization and performance. This process was consistently applied to the primary dataset and the APTOS 2019 datasets for model training.

Model

MobileNet is a family of lightweight CNN architectures optimized for efficient deployment on mobile and embedded devices46. In this study, a MobileNet-like structure is chosen due to its ability to significantly reduce computational complexity and memory footprint through the use of depthwise separable convolutions. This design makes the model highly suitable for resource-constrained devices such as smartphones or portable fundus cameras. Moreover, MobileNet has demonstrated competitive performance in various computer vision tasks, including medical imaging, while maintaining an architecture. These characteristics align with the goal of developing a lightweight, reliable DR screening model deployable in remote or low-resource settings. To further reduce the model’s computational complexity, knowledge distillation (KD) is used to transfer knowledge from a larger, pre-trained “Teacher” model to a smaller “Student” model. This process ensures that the smaller model achieves comparable performance while significantly reducing computational requirements, making it ideal for resource-constrained devices6768. Figure 5 shows the architecture of the “Teacher” model and “Student” model.

A lightweight student model was developed from MobileNet, by the principle of simplifying the teacher network by reducing the number of network layers and the sizes of filters, as outlined by Gou et al.67. This alignment also minimizes the “model capacity gap”, where a significant difference can hinder the Student model’s ability to effectively gain knowledge from the Teacher67. Then deeper blocks were systematically trimmed, filter sizes adjusted, stride patterns modified, and a custom fully connected classification head was used to achieve an optimal balance between computational complexity and predictive performance. These choices were specifically tailored for high-resolution (512\(\times\)512) medical images and resource-constrained deployment scenarios. Reducing the deeper layers in a Student model can help maintain important feature extraction ability while balancing computational efficiency and performance. The deeper layer frequently contains complicated, high-level information; yet, these layers can be computationally intensive. Therefore, by removing deep layers and building the shallower layers, which capture the core structural and low-level elements, the Student model achieves a good balance between maintaining useful information and minimizing the model’s overall size and latency. Our approach aligns with Wang et al.69, who explained that simplified models focus on retaining the main features while offloading complex, task-specific details to improve interpretability and performance on resource-constrained devices. The detailed Student model architecture is shown in Fig. 6 and Table 1.

The distillation of knowledge on MobileNet involves key components and steps as mentioned in Algorithm 2. The distillation process employs a composite loss function combining the standard task-specific loss with a distillation loss that encourages the Student to mimic the Teacher’s output distribution. The task-specific loss is computed using Categorical Cross-Entropy, while the distillation loss is calculated using the Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence applied to softened probability distributions from both models.

The Teacher model is a robust, pre-trained neural network that serves as the source of knowledge. It generates “soft labels” which are logits, probability distributions over classes, providing richer and more information than hard labels. On the other hand, the Student model is a smaller, lightweight network designed to replicate the performance of the Teacher model. The distillation loss is based on a composite loss function that integrates both soft and hard losses. Figure 7 shows the distillation process and how losses are calculated.

The predictions of the Teacher and Student models are softened using a temperature parameter \(T\), as described in Eqs. (1) and (2). The application of the SoftMax function with \(T\) smooths the probability distributions of the Teacher, making them less sharp (peaky) and more informative. This softened output allows the Student model to better capture important patterns during training.

To quantify how well the Student’s prediction distribution approximates the Teacher’s softened prediction distribution, the Kullback-Leibler (KL) Divergence is used. Therefore, the distillation loss is computed by applying KL Divergence to the softened labels (Eq. 1) and softened predictions (Eq. 2):

Here, x represents the output logit for each class. The KL divergence quantifies how closely the Student’s softened probability distribution approximates that of the Teacher.

The total loss for training the Student model combines the task-specific loss (student_loss), which uses CategoricalCrossentropy, and the distillation loss. The total loss is defined in Eq. (4):

Here, \(\alpha\) is a hyperparameter that controls the trade-off between learning from the ground truth labels (student_loss) and learning from the Teacher’s knowledge (distillation_loss). When \(\alpha \rightarrow 1\), the Student model relies more heavily on the task-specific loss; when \(\alpha \rightarrow 0\), the Student model relies predominantly on the Teacher’s softened knowledge.

While the Distiller class allows flexibility in selecting \(\alpha\) and temperature \(T\), systematic hyperparameter tuning was conducted using Keras-Tuner’s Hyperband algorithm to identify optimal values. The search space for \(\alpha\) was set to [0.1, 0.9] with increments of 0.1, and for temperature T to [0, 50] with increments of 5, optimizing for validation accuracy. The best-performing configuration was found to be \(\ alpha=0.5\) and \(T = 10\), and used for the knowledge distillation from the Teacher model, leading to improved Student model performance.

Experiment and result analysis

Experimental setup

The proposed model was trained and tested on a machine equipped with hardware specifications of 13th Gen Intel(R) Core(TM) i7-13700H, 2400 MHz, and 8GB NVIDIA-SMI 546.12 GPU, CUDA 12.3. The proposed model was implemented using the Keras API on the TensorFlow framework version 2.10.0.

Performance evaluation metrics

Performance metrics are quantitative measures used to evaluate our model’s effectiveness on the dataset. The metrics formula used in our study is shown as follows;

Result analysis

Teacher model selection

This research utilizes MobileNet, a family of lightweight CNNs optimized for efficient use on mobile and embedded devices. Both MobileNet and MobileNetV2 are evaluated to find the best Teacher’s model that can effectively lead to the development of a lightweight, accurate Student model. During the Teacher model selection phase, the models are evaluated on ternary classification: No-DR, Non-proliferative DR, and Proliferative DR. The detail of model configuration is shown in Table 2 and various values of \(\alpha\), which determine the width multiplier. Our experiments showed that MobileNet with \(\alpha\) value of 0.25 achieved the optimal combination of performance and efficiency, making it the ideal Teacher model for our research. Table 4 and Fig. 8 show the results of MobileNet with MobileNetV2 at various \(\alpha\) values. These visualizations provide a clear overview of each model’s strengths and help us to identify a high-performing Teacher model, which will later be refined into an even lighter Student model suitable for real-time application in a computational constraint device.

Furthermore, the model training setup and configuration were thoughtfully designed to ensure smooth convergence and optimal generalization of the proposed student model enhanced through knowledge distillation. To support effective learning and systematically monitor the model’s performance, several callback mechanisms were integrated during training. Specifically, a ReduceLROnPlateau callback was employed to dynamically adjust the learning rate by a factor of 0.2 when the validation loss failed to improve for three consecutive epochs, with the minimum learning rate capped at \(1 \times 10^{-12}\). To mitigate overfitting, EarlyStopping was applied with a patience of 13 epochs, ensuring that the model reverted to the best-performing weights observed during training. The complete details of these configurations are summarized in Table 3.

Binary classification

In binary classification, our objective is to evaluate the performance of the model in classifying retinal fundus images into two groups: ’No_DR’ and ’DR’. The model performed well in the binary classification task, indicating that it is capable of accurately distinguishing the two classes. This high degree of separability demonstrates the model’s ability to efficiently differentiate normal retinal fundus images from those containing DR features. The Teacher model demonstrates superior performance on APTOS 2019 and primary datasets compared to the Student models, including both the Student with KD and without KD. Notably, the Student model with KD achieves comparable performance to the Teacher model across these datasets. This outcome shows the effectiveness of KD techniques in successfully transferring insights from the Teacher model to the Student model. Additionally, training the model on the primary dataset begins with initializing the model with the weights gained from the APTOS 2019 dataset. This approach adopts the model’s generalization capacity from the APTOS 2019 dataset to a primary dataset, assuring its robustness and effectiveness in deployment for a local eye clinic.

Table 5 presents the performance of the Teacher and Student models, with and without knowledge distillation, on the APTOS 2019 dataset. Similarly, Table 6 shows primary datasets. The Student model trained with KD consistently outperformed students without KD, achieving an accuracy of 98.36% on APTOS 2019 and 93.20% on the primary dataset. These results demonstrate the effectiveness of KD in enhancing model generalization and accuracy, especially under limited data conditions. While all models performed best on APTOS 2019, the performance drop on the primary dataset is likely due to the small dataset and variability. Nonetheless, KD proved beneficial in transferring knowledge from the Teacher to the Student model. Additionally, the model’s performance is shown in detail in Fig. 9.

Cross-validation is a resampling technique used to assess the performance of a machine learning model by partitioning the dataset into multiple subsets. This method ensures that the model is evaluated on unseen data, reducing the risk of overfitting and providing a more reliable estimate of its generalization performance.

Furthermore, cross-validation is employed to evaluate the robustness of the proposed model as shown in Table 7. Given the high class imbalance in the dataset, the StratifiedKFold method is utilized to maintain the original class distribution across training and validation splits, ensuring a fair evaluation.

The model’s learning curve gives useful information about the pattern of the Teacher model and Student model with KD and without KD in the training stage, indicating if the model has reached the optimal performance. It also helps in detecting signs of over-fitting or under-fitting. Additionally, it indicates the model’s learning pattern, indicating whether it is failing to learn or progressively improving over time. Therefore, the learning curve of our models demonstrates strong performance and convergence to an optimal performance. Additionally, the curve does not show any signs of under-fitting or over-fitting, indicating a well-fitted model. However, the learning curve of the models on the primary dataset shows slight fluctuations, indicating difficulty in understanding the unique aspects of the primary data, particularly for the Student model without KD. Despite these fluctuations, the curve gradually converges, indicating that the model has been successfully trained to identify DR from normal retinal fundus images. Figures 10, 11 shows the learning curve of student model with KD, where as Figs. 17, 18 shows the learning curves of the Teacher and Student models without knowledge distillation, on the APTOS 2019 and primary datasets, respectively.

A confusion matrix provides a clearer picture of class-wise model performance, especially on imbalanced datasets, making it essential for targeted model improvements. Therefore, our model’s confusion matrix in binary classification shows that our model is good at identifying the class of samples without confusion in APTOS 2019 and the primary datasets. The model predicts True Positives and True Negatives well, while False Positives and False Negatives occur more rarely. This shows that the model’s predictions are very close to the actual labels. Figure 12 shows the confusion matrix of the teacher and student model with KD and without KD on each dataset.

Ternary classification

The main objective of ternary classification is to build a robust model for automated grading of retinal fundus images, in which images are classified based on DR categories. This classification is crucial for the early detection and treatment of DR. The three categories considered for ternary classifications are listed as follows70:

-

1.

No DR: The retina is free of detectable signs of DR, indicating a healthy retinal condition.

-

2.

Non-proliferative DR (NPDR): This category represents the blood or liquid leakage at the back of the eye, the so-called retina. This category includes a grade of mild, moderate, and severe diabetic retinopathy.

-

3.

Proliferative DR (PDR): This category identifies advanced DR, characterized by the growth of abnormal blood vessels. PDR poses a high risk of vision impairment if left untreated, which requires timely ophthalmologist intervention.

In our experiment, the proposed model achieves good performance across all datasets, demonstrating its robustness in ternary classification. The results are presented in Table 8 and 9 for the APTOS 2019 and Primary datasets, respectively. The performance of the model on the Primary datasets is slightly lower than on the APTOS 2019 dataset, as the Primary datasets are smaller. However, the performance of our proposed model shows comparable results to the teacher model. The proposed model achieves up to 93.09% accuracy on the APTOS 2019 dataset, whereas the proposed model achieved 85.51% accuracy on the primary dataset. The scores, particularly in recall (the ability to correctly identify all relevant cases) and F1-score (which balances precision and recall), indicate reliable classification and strong generalization capability. Additionally, the model’s performance is shown in detail in Fig. 13. Despite a 74% reduction in trainable parameters and floating point operations per second (FLOPS), the model maintains strong performance. As our main objective is to build a model with less computational intensity while maintaining comparable performance to the Teacher model (pre-trained), a lightweight Student model is successfully developed with strong performance in ternary classification as well (Table 10).

Furthermore, cross-validation is also employed for the ternary class to evaluate the class-wise performance and robustness of the proposed model as shown in Figure 10.

The learning curves illustrate the training patterns of our models, showing a smooth convergence for each model. Additionally, it depicts the learning behavior of the teacher model and the student models, both with and without KD. Figures 14 and 15 show the learning curves of the student model with KD, whereas Figs. 19 and 20 shows the Teacher and Student models without KD on the APTOS 2019 and Primary datasets, respectively.

On the other hand, the confusion matrices illustrate the classification performance of the models. The Student model without knowledge distillation (KD) on the APTOS 2019 dataset shows significant confusion, indicating difficulty in distinguishing between classes. The confusion matrices for each model across all datasets are presented in Fig. 16. Overall, the results demonstrate that the models have effectively learned and extracted essential features and lesion patterns during training.

Performance comparision

Binary classification

The performance comparison of the proposed model with various state-of-the-art techniques is shown in Table 11. While many of the reviewed models demonstrate competitive accuracy, our proposed Student model with knowledge distillation (KD) achieves a superior balance between classification performance and computational efficiency.

Chetoui et al.32 employed the EfficientNet-B7 architecture, achieving a recall of 98.1%. However, its large model size, approximately 66.7 million trainable parameters, renders it impractical for deployment on resource-constrained devices. In contrast, our Student model with KD achieves a nearly equivalent recall of 98.18% while using only 71,362 parameters, offering a drastic reduction in complexity.

Similarly, BK Anoop et al.25 achieved 94.6% accuracy and 86% recall using a CNN model with an enormous 184 million parameters. Despite its high accuracy, the substantial parameter count poses limitations for scalability. Our Student model with KD not only surpasses this model in accuracy (98.18%) and recall (98.18%) but does so with a model that is more than 2,500 times smaller.

Bala et al.28 proposed a CNN model with 1.1 million parameters, reporting 97.54% accuracy and an F1-score of 0.97. While their model is relatively lightweight compared to others, our KD-enabled Student model achieves comparable or better performance with less than 7% of the parameters, further emphasizing its efficiency.

In another notable work, Islam et al.39 utilized a hybrid ResNet152V2 + Vision Transformer (ViT) as a Teacher model, comprising 145.8 million parameters and yielding 95.15% accuracy. Our Teacher model, based on MobileNet, achieves a higher accuracy of 98.55% using only 279,378 parameters, underscoring our model’s efficiency without compromising accuracy. Furthermore, their corresponding Student model, built using XCeption with CBAM, achieved 99% accuracy with 21.4 million parameters. In comparison, our KD-based Student model achieves a competitive 98.18% accuracy with just 71,362 parameters.

Ternary classification

The performance comparison of the proposed model with state-of-the-art techniques for ternary classification is shown in Table 12. The results demonstrate that our proposed models consistently maintain good classification performance across APTOS 2019 datasets, while significantly reducing computational requirements. Although existing studies have achieved good results, many of them involve models with a large number of trainable parameters, limiting their practicality in resource-constrained environments.

Athira et al.40 utilized a ResNet50 model to achieve 94% accuracy, precision, and recall, using 25.6 million parameters. In comparison, our Student model with KD achieves a closely matching performance of 93% across all metrics, while requiring only 71,491 parameters, demonstrating a substantial reduction in model size.

Rao et al.73 proposed an InceptionResNet model and reported 88% accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score with 55.9 million parameters. Our Student model with KD outperforms this model in all metrics, with nearly 780 times fewer parameters.

Kobat et al.74 used a DenseNet architecture combined with a Cubic SVM classifier, achieving 93.85% accuracy and strong precision. Butt et al.41 introduced a hybrid model combining GoogleNet, ResNet-18, and SVM, reporting 89% across metrics. Although effective, these models likely carry higher computational loads compared to our student model with KD.

Our Teacher model, based on MobileNet, achieves 94% across all metrics on the APTOS dataset with only 279,378 parameters. Meanwhile, the Student model without KD shows a notable performance drop (70% accuracy and recall), highlighting the effectiveness of knowledge distillation in enhancing lightweight models. The KD-based Student model demonstrates strong performance (93%) while remaining highly efficient.

These results show that our proposed KD-based Student model provides a good performance and efficiency. Its lightweight architecture makes it particularly well-suited for real-time and mobile applications, where memory and processing power are often limited.

Discussion

One of the limitations of ML models is that they are heavyweight. In this regard, our proposed model is a lightweight model with comparable performance to the heavy and highly computational-intensive model proposed by researchers. Furthermore, knowledge distillation has significantly impacted the transfer of knowledge from the teacher model to the student model. There is a huge difference between the student model built from scratch and the student model built with knowledge distillation; this shows a significant role of knowledge distillation techniques in transferring knowledge from the teacher model. Additionally, the proposed model has been evaluated on APTOS 2019, and primary datasets collected from local eye clinic centers. The performance of the model on primary datasets shows the robustness of the model on different datasets.

After a thorough experiment on the separability of NPDR severity levels, the distinction in NPDR severity levels often leads to overlaps in key image features called lesions. Furthermore, the case study presented at the TensorFlow Dev Summit 201775 demonstrated that even domain experts (ophthalmologists), may provide varying gradings for the same retinal images. These grading inconsistencies are particularly challenging in cases of NPDR. Therefore, for better alignment with clinical practice, clarity, and appropriateness of medication and treatment for each category, ternary classification is chosen to be our experiment for multi-class classification.

On the other hand, t-SNE was employed to demonstrate the model’s ability to cluster the test dataset effectively. We visualized the feature representations extracted from the Global Average Pooling (GAP) layer and the Output layer to assess how well the models are clustering the data. In the binary classification task, the models show a clear ability to group the test dataset according to their respective classes, demonstrated on the APTOS 2019 and primary dataset in Figs. 21, 22, 23, and 24. However, in the ternary classification task, the models exhibit slight confusion when distinguishing between the three classes, particularly the Student model without KD. This indicates that while the model performs well in binary classification, it faces more challenges when dealing with ternary classes.

To further validate these observations, the Silhouette Score and Davies–Bouldin Index (DBI) for both binary and ternary classification on the primary dataset, and APTOS 2019 dataset dataset are shown in Tables 14, 15, 16, and 17. These metrics quantitatively assess the quality of grouping in the extracted features from GAP and the output layer of each model. The Output layer consistently achieves good feature separability compared to the GAP layer and the test dataset. Furthermore, the Student model with KD generally demonstrates superior clustering behavior compared to the Student model without KD, supporting the effectiveness of KD in improving the model’s performance of feature representations. While in the binary classification, the model demonstrated better feature separability for classifying No DR and DR cases, its performance notably decreased for ternary classification, indicating the model’s a little confusion in capturing lesion variations between categories like PDR and NPDR.

Knowledge distillation is a technique that enables a smaller Student model to learn from a larger, more complex Teacher model. Through this process, the Student model captures essential knowledge and approximates the performance of the Teacher model, even with reduced computational complexity. As a result, knowledge distillation produces a highly efficient Student model that is compact enough for deployment on resource-constrained devices. Table 13 shows the detailed model computational complexity of the teacher model and the proposed student model on the primary dataset.

Generally, the main strengths and contributions of the study presented in this article include:

-

A lightweight student model was developed from MobileNet, by the principle of simplifying the teacher network by reducing the number of network layers and the sizes of filters, as outlined by Gou et al.67.

-

The significance of knowledge distillation in building lightweight models with performance comparable to Teacher model.

-

The robustness of the proposed model, demonstrated by evaluating its performance on the APTOS 2019 dataset and the primary dataset for both binary and ternary classification.

Conclusion and future work

This study presented a knowledge distillation technique to transfer knowledge from the Teacher model to the proposed Student model. The Student model comprises only five Depthwise Convolutional Blocks, followed by two fully connected layers for classification. With knowledge distillation, the proposed model demonstrated promising results, whereas the Student model without knowledge distillation struggled to perform effectively.

The models were evaluated on APTOS 2019 and primary datasets, demonstrating robustness across diverse datasets. A comparison with state-of-the-art techniques revealed that the proposed model achieves comparable performance while being significantly less resource-intensive. For binary classification, our proposed model achieved an accuracy of 98.38% on the APTOS 2019 dataset. Furthermore, the student model with knowledge distillation achieved an accuracy of 93.03% for ternary classification on APTOS 2019.

Additionally, the proposed model demonstrates strong class separability in feature space, as visualized using t-SNE on test data. To further assess separability, features extracted from the Global Average Pooling (GAP) and Output layers were visualized using t-SNE

The findings of this study show that the proposed lightweight model with knowledge distillation achieves good performance and is suitable for deployment in resource-constrained devices. Future work will focus on enhancing the model’s performance using alternative knowledge distillation techniques like FitNets, Hint-based KD, self-distillation, and using Neural Architecture Search or pruning for selecting important nodes, an algorithmic solution for inseparable classes, and employing interpretability techniques to enhance the understanding and clarity of the model’s predictions.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Yau, J. W. et al. Global prevalence and major risk factors of diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes care 35(3), 556–564 (2012).

Antonetti, D. A., Klein, R. & Gardner, T. W. Mechanisms of disease diabetic retinopathy. New England Journal of Medicine 366(13), 1227–1239 (2012).

Atlas, D., et al.: International diabetes federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas, 7th edn. Brussels, Belgium: International Diabetes Federation 33(2) (2015)

Cho, N. H. et al. Idf diabetes atlas: Global estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2017 and projections for 2045. Diabetes research and clinical practice 138, 271–281 (2018).

Graham-Rowe, E. et al. Barriers to and enablers of diabetic retinopathy screening attendance: a systematic review of published and grey literature. Diabetic Medicine 35(10), 1308–1319 (2018).

Bishu, K. G. et al. Diabetes in ethiopia: a systematic review of prevalence, risk factors, complications, and cost. Obesity Medicine 15, 100132 (2019).

Fite, R. O., Lake, E. A. & Hanfore, L. K. Diabetic retinopathy in ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews 13(3), 1885–1891 (2019).

Ejigu, T. & Tsegaw, A. Prevalence of diabetic retinopathy and risk factors among diabetic patients at university of gondar tertiary eye care and training center, north-west ethiopia. Middle East African Journal of Ophthalmology 28(2), 71 (2021).

Kifle, M., Mbarika, V. W. & Datta, P. Telemedicine in sub-saharan africa: The case of teleophthalmology and eye care in ethiopia. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 57(10), 1383–1393 (2006).

Wong, T. Y. et al. Guidelines on diabetic eye care: the international council of ophthalmology recommendations for screening, follow-up, referral, and treatment based on resource settings. Ophthalmology 125(10), 1608–1622 (2018).

Wang, S. Y. et al. Ophthalmic screening patterns among youths with diabetes enrolled in a large us managed care network. JAMA ophthalmology 135(5), 432–438 (2017).

Eppley, S. E., Mansberger, S. L., Ramanathan, S. & Lowry, E. A. Characteristics associated with adherence to annual dilated eye examinations among us patients with diagnosed diabetes. Ophthalmology 126(11), 1492–1499 (2019).

Alwazae, M., et al.: Barriers for adherence to diabetic retinopathy screening among saudi adults. Cureus. 11(12), (2019)

Feder, R. S. et al. Comprehensive adult medical eye evaluation preferred practice pattern® guidelines. Ophthalmology 123(1), 209–236 (2016).

Resnikoff, S. et al. Estimated number of ophthalmologists worldwide (international council of ophthalmology update): will we meet the needs?. British Journal of Ophthalmology 104(4), 588–592 (2020).

Dubow, M. et al. Classification of human retinal microaneurysms using adaptive optics scanning light ophthalmoscope fluorescein angiography. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science 55(3), 1299–1309 (2014).

Murugesan, N., Üstunkaya, T. & Feener, E.P.: Thrombosis and hemorrhage in diabetic retinopathy: a perspective from an inflammatory standpoint. In: Seminars in Thrombosis and Hemostasis, 659–664 (Thieme Medical Publishers, 2015).

Amin, J., et al.: A review on recent developments for detection of diabetic retinopathy. Scientifica 2016 (2016)

Mateen, M., Wen, J., Nasrullah, N., Sun, S. & Hayat, S. Exudate detection for diabetic retinopathy using pretrained convolutional neural networks. Complexity 2020(1), 5801870 (2020).

Senapati, A., Tripathy, H.K., Sharma, V. & Gandomi, A.H.: Artificial intelligence for diabetic retinopathy detection: a systematic review. Informatics in Medicine Unlocked, 101445 (2024)

Shah, A. et al. Validation of automated screening for referable diabetic retinopathy with an autonomous diagnostic artificial intelligence system in a spanish population. Journal of diabetes science and technology 15(3), 655–663 (2021).

Xie, Y. et al. Artificial intelligence for teleophthalmology-based diabetic retinopathy screening in a national programme: an economic analysis modelling study. The Lancet Digital Health 2(5), 240–249 (2020).

Poore, S., Foster, A., Zondervan, M. & Blanchet, K. Planning and developing services for diabetic retinopathy in sub-saharan africa. International journal of health policy and management 4(1), 19 (2015).

Matimba, A. et al. Tele-ophthalmology: opportunities for improving diabetes eye care in resource-and specialist-limited sub-saharan african countries. Journal of telemedicine and telecare 22(5), 311–316 (2016).

Anoop, B. Binary classification of dr-diabetic retinopathy using cnn with fundus colour images. Materials Today: Proceedings 58, 212–216 (2022).

Ishtiaq, U., Abdullah, E. R. M. F. & Ishtiaque, Z. A hybrid technique for diabetic retinopathy detection based on ensemble-optimized cnn and texture features. Diagnostics 13(10), 1816 (2023).

Ishtiaq, U., et al.: Diabetic retinopathy detection through artificial intelligent techniques: a review and open issues. Multimedia Tools and Applications 79, 15209–15252 (2020)

Bala, R., Sharma, A. & Goel, N.: A novel convolutional neural network architecture for diabetic retinopathy screening. In: 2022 4th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Speech Technology (AIST), 1–6 (IEEE, 2022).

Huang, G., Liu, Z., Van Der Maaten, L. & Weinberger, K.Q.: Densely connected convolutional networks. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 4700–4708 (2017)

Rêgo, S., Dutra-Medeiros, M., Soares, F. & Monteiro-Soares, M. Screening for diabetic retinopathy using an automated diagnostic system based on deep learning: diagnostic accuracy assessment. Ophthalmologica 244(3), 250–257 (2021).

Nandakumar, R., Saranya, P., Ponnusamy, V., Hazra, S. & Gupta, A.: Detection of diabetic retinopathy from retinal images using densenet models. Computer Systems Science & Engineering. 45(1) (2023)

Chetoui, M. & Akhloufi, M.A.: Explainable diabetic retinopathy using efficientnet. In: 2020 42nd Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC), 1966–1969 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1109/EMBC44109.2020.9175664

Jiang, H., et al.: A multi-label deep learning model with interpretable grad-cam for diabetic retinopathy classification. In: 2020 42nd Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC), 1560–1563 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1109/EMBC44109.2020.9175884

Beghriche, T., Attallah, B., Brik, Y. & Djerioui, M. A multi-level fine-tuned deep learning based approach for binary classification of diabetic retinopathy. Chemometrics and Intelligent Laboratory Systems 237, 104820 (2023).

Liu, P., Wang, L., Ranjan, R., He, G. & Zhao, L. A survey on active deep learning: from model driven to data driven. ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR) 54(10s), 1–34 (2022).

Koch, G., Zemel, R. & Salakhutdinov, R., : Siamese neural networks for one-shot image recognition. In: ICML Deep Learning Workshop, Lille, 2, (2015).

Qureshi, I., Ma, J. & Abbas, Q. Diabetic retinopathy detection and stage classification in eye fundus images using active deep learning. Multimedia Tools and Applications 80, 11691–11721 (2021).

Deepa, V., Sathish Kumar, C. & Cherian, T. Automated grading of diabetic retinopathy using cnn with hierarchical clustering of image patches by siamese network. Physical and Engineering Sciences in Medicine 45(2), 623–635 (2022).

Islam, N. et al. Toward lightweight diabetic retinopathy classification: A knowledge distillation approach for resource-constrained settings. Applied Sciences 13(22), 12397 (2023).

Athira, T. & Nair, J. J. Diabetic retinopathy grading from color fundus images: An autotuned deep learning approach. Procedia Computer Science 218, 1055–1066 (2023).

Butt, M. M., Iskandar, D. A., Abdelhamid, S. E., Latif, G. & Alghazo, R. Diabetic retinopathy detection from fundus images of the eye using hybrid deep learning features. Diagnostics 12(7), 1607 (2022).

Barhate, N., Bhave, S., Bhise, R., Sutar, R.G. & Karia, D.C.: Reducing overfitting in diabetic retinopathy detection using transfer learning. In: 2020 IEEE 5th International Conference on Computing Communication and Automation (ICCCA), 298–301 (IEEE, 2020).

Khaled, O., et al.: Cascaded architecture for classifying the preliminary stages of diabetic retinopathy. In: Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Software and Information Engineering, 108–112 (2020)

Khan, Z. et al. Diabetic retinopathy detection using vgg-nin a deep learning architecture. IEEE Access 9, 61408–61416 (2021).

Sudarmadji, P.W., Pakan, P.D. & Dillak, R.Y.: Diabetic retinopathy stages classification using improved deep learning. In: 2020 International Conference on Informatics, Multimedia, Cyber and Information System (ICIMCIS), 104–109 (IEEE, 2020).

Howard, A.G., et al.: Mobilenets: Efficient convolutional neural networks for mobile vision applications. arXiv preprint arXiv:1704.04861 (2017)

Riaz, H., Park, J., Choi, H., Kim, H. & Kim, J. Deep and densely connected networks for classification of diabetic retinopathy. Diagnostics 10(1), 24 (2020).

Ayala, A., Ortiz Figueroa, T., Fernandes, B. & Cruz, F. Diabetic retinopathy improved detection using deep learning. Applied Sciences 11(24), 11970 (2021).

Doshi, N., Oza, U. & Kumar, P.: Diabetic retinopathy classification using downscaling algorithms and deep learning. In: 2020 7th International Conference on Signal Processing and Integrated Networks (SPIN), 950–955 (IEEE, 2020).

Bhardwaj, C., Jain, S. & Sood, M. Diabetic retinopathy severity grading employing quadrant-based inception-v3 convolution neural network architecture. International Journal of Imaging Systems and Technology 31(2), 592–608 (2021).

Salam, A. A., Mahadevappa, M., Das, A. & Nair, M. S. Drg-net: A graph neural network for computer-aided grading of diabetic retinopathy. Signal, Image and Video Processing 16(7), 1869–1875 (2022).

Zhang, K., Pu, Z., Jin, C., Zhou, Y. & Wang, Z. A novel semi-local centrality to identify influential nodes in complex networks by integrating multidimensional factors. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence 145, 110177 (2025).

Bilal, A., Liu, X., Shafiq, M., Ahmed, Z. & Long, H. Nimeq-sacnet: A novel self-attention precision medicine model for vision-threatening diabetic retinopathy using image data. Computers in biology and medicine 171, 108099 (2024).

Hu, T. et al. Lcn2 deficiency mitigates the neuroinflammatory damage following acute glaucoma. Theranostics 15(7), 2967 (2025).

He, K. et al. Environmental endocrine disruptor-induced mitochondrial dysfunction: a potential mechanism underlying diabetes and its complications. Frontiers in Endocrinology 15, 1422752 (2024).

Sun, J., et al.: Real-time accurate detection and analysis of breath acetone using crds: Toward metabolic dynamic monitoring and potential application. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 433, 137422 (2025) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.snb.2025.137422

Yu, X. et al. Deep learning for fast denoising filtering in ultrasound localization microscopy. Physics in Medicine & Biology 68(20), 205002 (2023).

Luan, S. et al. Deep learning for fast super-resolution ultrasound microvessel imaging. Physics in medicine & biology 68(24), 245023 (2023).

Liang, J. et al. The regulation of selenoproteins in diabetes: A new way to treat diabetes. Current Pharmaceutical Design 30(20), 1541–1547 (2024).

Wu, Z., Sun, W., & Wang, C.: Clinical characteristics, treatment, and outcomes of pembrolizumab-induced uveitis. Investigational New Drugs, 1–8 (2024)

Singh, L.K., Garg, H., & Pooja: Automated glaucoma type identification using machine learning or deep learning techniques. Advancement of machine intelligence in interactive medical image analysis, 241–263 (2020)

Qureshi, K. N., Alhudhaif, A., Qureshi, M. A. & Jeon, G. Nature-inspired solution for coronavirus disease detection and its impact on existing healthcare systems. Computers and Electrical Engineering 95, 107411 (2021).

Singh, L. K., Khanna, M., Garg, H. & Singh, R. Efficient feature selection based novel clinical decision support system for glaucoma prediction from retinal fundus images. Medical Engineering & Physics 123, 104077 (2024).

Singh, L. K. & Garg, H. Detection of glaucoma in retinal images based on multiobjective approach. International Journal of Applied Evolutionary Computation (IJAEC) 11(2), 15–27 (2020).

Karthik, S.D. Maggie: APTOS 2019 Blindness Detection. Kaggle. Accessed: 2025/11/28 07:42:19(2019). https://kaggle.com/competitions/aptos2019-blindness-detection

Graham, B.: Kaggle diabetic retinopathy detection competition report. University of Warwick 22(9), (2015)

Gou, J., Yu, B., Maybank, S. J. & Tao, D. Knowledge distillation: A survey. International Journal of Computer Vision 129(6), 1789–1819 (2021).

Debelee, T.G., & Ayano, Y.M.: Deep learning models for audio processing applications under resource-constrained devices: A survey. In: Pan African Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 209–232 (Springer, 2022).

Wang, J., Gou, L., Zhang, W., Yang, H. & Shen, H.-W. Deepvid: Deep visual interpretation and diagnosis for image classifiers via knowledge distillation. IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics 25(6), 2168–2180. https://doi.org/10.1109/TVCG.2019.2903943 (2019).

Memon, W.R., Lal, B. & Sahto, A.A.: Diabetic retinopathy;: Frequency at level of hba1c greater than 6.5%. The Professional Medical Journal. 24(02), 234–238 (2017)

Tuncel, M. & Uçar, M. Classification of diabetic retinopathy disease with deep learning methods. Artificial Intelligence Theory and Applications 5(1), 1–17 (2025).

Naveen, K., Anoop, B., Siju, K., Kar, M.K., & Venugopal, V.: Effnet-svm: A hybrid model for diabetic retinopathy classification using retinal fundus images. (IEEE Access, 2025)

Rao, M., Zhu, M., Wang, T.: Conversion and implementation of state-of-the-art deep learning algorithms for the classification of diabetic retinopathy. arXiv preprint arXiv:2010.11692 (2020)

Kobat, S. G. et al. Automated diabetic retinopathy detection using horizontal and vertical patch division-based pre-trained densenet with digital fundus images. Diagnostics 12(8), 1975 (2022).

Peng, L.: Case study: Tensorflow in medicine - retinal imaging. In: TensorFlow Dev Summit 2017 (2017). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oOeZ7IgEN4o

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Fitsum Mesfin Dejene: Conceptualization, methodology, experimentation, and writing; Yehualashet Megersa Ayano: Conceptualization, methodology, validating experiments, and writing-editing; Degaga Wolde Feyisa: Conceptualization, methodology, and validating experiments; Taye Girma Debelee: Methodology, validating experiments, and writing-editing; Hiwot Taye Mekonnen: Data collection and supervised the data annotation process; Girum Woldegebreal Gessesse: Data collection, data annotation, trained model validation; Zelalem Chimdesa Merga: Conceptualization and data collection; Hasset Tamirat Molla: Conceptualization and data collection; Destaw Mulie: Data collection, data annotation, trained model validation

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical guidelines established by the National Ethical Review Board (NERB). Ethical approval was granted by the Institutional Review Board of the Addis Ababa Health Bureau, with official letter reference number/A/H/6009/227, issued on 17/03/2016 (Ethiopian Calendar), corresponding to 27/11/2023 (Gregorian Calendar). Informed consent was obtained from all adult participants prior to undergoing fundoscopic imaging.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix A: Learning curves

Appendix B: Supplemental figures

Appendix C: Supplemental tables

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dejene, F.M., Ayano, Y.M., Feyisa, D.W. et al. Knowledge distillation-based lightweight MobileNet model for diabetic retinopathy classification. Sci Rep 16, 1181 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30893-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30893-7