Abstract

Deep learning (DL) reconstruction is increasingly applied in clinical magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to improve image quality and reduce scan time, but its impact on dental metal artifacts remains unclear. This pilot phantom study evaluated DL reconstruction compared with conventional reconstruction for various implant crowns. Acrylic phantoms containing titanium implants with four crown types—zirconia, PMMA, gold, and Ni–Cr metal—were scanned on a 3.0-T MRI system. Axial T1- and T2-weighted sequences were acquired using identical imaging parameters. Image quality (noise and signal-to-noise ratio [SNR]) and metal artifacts (visual scores and artifact ratio) were evaluated in the slice showing the largest crown area. DL reconstruction consistently reduced noise and improved SNR across all crown types and sequences. Metal artifact severity followed the material-dependent order: zirconia < PMMA < gold < Ni–Cr metal, in both sequences. Visual assessment showed no difference in artifact severity between DL and conventional images. DL reduced artifacts only in zirconia crowns on T2-weighted sequence (10.38% vs. 9.31%). These findings indicate that although DL reconstruction enhances overall image quality, its effectiveness in reducing dental metal artifacts remains limited. As this is a pilot study using phantoms, further in vivo validation is necessary.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a technique for acquiring images of the body using a strong magnetic field and radiofrequency energy. Unlike other imaging modalities, it does not use ionizing radiation and offers significant advantages in the evaluation of soft tissues.1 In the dental field, MRI is used for the evaluation of oral cancers, salivary gland diseases, and temporomandibular joint disorders, with ongoing research expanding its applications to complex periapical lesions, periodontal disease, and nerve damage.2

As the population ages, the prevalence of intraoral prostheses—including dental implants—continues to rise. Various prosthetic materials produce metal artifacts due to differences in magnetic susceptibility between the prosthetic material and the surrounding tissues.3,4 Magnetic susceptibility refers to the property of a material to become magnetized when exposed to a magnetic field. While human tissues exhibit weak diamagnetic properties, metals typically have paramagnetic or ferromagnetic characteristics.3,4 When metal is placed within the main magnetic field of MRI, it generates an additional magnetic field in its vicinity, making the main field inhomogeneous and leading to the occurrence of metal artifacts. Metal artifacts are defined as signal intensity distortions and signal loss surrounding a prosthesis and differ in appearance from the metal artifacts observed in computed tomography (CT) or cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) (Fig. 1).1 These artifacts hinder the accurate assessment of lesion signal intensity and, in severe cases, obscure critical anatomical regions, making diagnosis difficult (Fig. 2). Previous studies have investigated MRI artifacts associated with various types of metallic dental prostheses and materials.5,6 Metal crowns and orthodontic stainless steel wires have been shown to produce more pronounced artifacts, while zirconia and resin materials are associated with less severe artifacts.

A patient with multiple dental prostheses and implants. (A) Panoramic radiograph. (B) Axial CBCT image showing metal artifacts: cupping artifacts (distortion of metallic structure), beam hardening (dark bands), and scatter (white streaks). (C) Axial MR image. Metal artifacts (dashed circle) appear as a dark and bright area adjacent to the prosthesis.

Unlike CT, where a single exposure can yield multiple reconstructions, MRI requires separate acquisitions for each sequence (e.g., T1-weighted, T2-weighted) in most cases, and artifact severity can vary between sequences. Several sequences have been developed to reduce these artifacts, including slice-encoding for metal artifact correction (SEMAC) and multi-acquisition with variable resonance image combination (MAVRIC).7,8,9,10 However, these techniques involve longer acquisition times and may not be widely available in routine MRI.

Recently, artificial intelligence (AI), particularly deep learning (DL) reconstruction, has been introduced to improve MRI efficiency and image quality. Commercially available and vendor-supplied DL reconstruction algorithms are increasingly being used routinely in clinical settings. DL reconstruction algorithms have demonstrated significant reductions in noise and scan time, and have been validated for clinical use in multiple anatomical regions.11,12,13,14,15,16,17 Despite these advancements, no studies to date have evaluated the image quality and metal artifacts of DL reconstructed images for various implant prostheses.

This pilot phantom study aimed to evaluate the image quality and metal artifacts in DL reconstructed MR images of four types of dental implant crowns and compare them with conventional images.

Methods

Phantom preparation for dental implant crowns

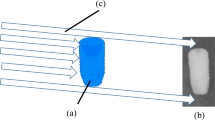

Four types of crowns were used in the fabrication of the phantom: zirconia, polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA), gold, and nickel-chrome (Ni–Cr) metal, which are widely used in implant prostheses (Table 1, Fig. 3A). Because metal artifacts vary depending on the size and shape of the metal, crowns of identical dimensions and shapes were fabricated using a CAD-CAM system on titanium implant fixtures (diameter × length: 4.5 × 12 mm) and abutments (diameter × length: 4.5 × 5.5 mm) (Dentium, Seoul, Korea).

Schematic representation of the study. (A) Fabrication of the four crown types using a CAD-CAM system. (B) Phantom preparation containing the implant and crown embedded in a 1.5% agar solution. The crown margin is positioned at the center ( +). (C) Post-MRI acquisition image analysis on the axial slice showing the largest crown area. Image quality (noise and SNR) and visual score of metal artifact were assessed using across the entire image, and metal artifacts were analyzed within the central 5 × 5 cm square ROI (red box). Signal intensity for binarization was measured in four 1 × 1 cm ROIs (blue boxes) placed immediately outside the four corners of the central ROI. After binarization, metal artifacts appeared as black areas, and their area was automatically calculated as a percentage of the total ROI. PMMA, polymethyl methacrylate; Ni–Cr, nickel-chrome; SNR, signal-to-noise ratio; ROI, region of interest.

After each crown was attached to its corresponding implant using temporary cement, the crown was positioned so that its margin was centered within a cube-shaped acrylic container measuring 10 × 10 × 10 cm. A 1.5% agar solution was prepared by mixing Select Agar powder (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) with distilled water, autoclaved at 121 °C for 15 min, poured into the container, and left to harden at room temperature (Fig. 3B).

MRI acquisition

Axial MRI scans of the four phantoms were obtained using a 3.0-T scanner (Pioneer; GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI, USA) with a 16-channel large flex coil. All phantoms were placed in the same marked position on the imaging table and conventional and DL images of T1- and T2-weighted sequences were acquired using the same imaging parameters (Table 2). DL images were generated with AIR Recon DL (GE Healthcare), a vendor-provided algorithm. Instead of relying solely on Fourier transform-based reconstruction, conventional reconstruction, AIR Recon DL uses DL to fill in missing data points in under sampled k-space data. Leveraging DL models trained on high-resolution images, the software is able to reconstruct fine details that may be lost with traditional under sampling imaging techniques, meaning higher resolution images can be generated using less data. It also removes noise and ringing from raw images, ensuring clear scans at all times. This can reduce scan times by up to 50%, streamlining workflow and improving patient experience.18 It is increasingly being used in clinical practice.

Image analysis

Axial slices displaying the largest crown area in each sequence were exported as Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM) files to a personal computer. Image quality and metal artifacts were analyzed on the corresponding slices (Fig. 3C). The analysis results were compared between DL and conventional images for the T1- and T2-weighted sequences, respectively.

Image quality was quantitatively evaluated using measurements of noise and signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). In MRI, signals are generated from the target of interest, but unwanted noise is also produced. The ratio of signal to noise is referred to as the SNR. A high SNR indicates that the signal is clear and readily detectable, whereas a low SNR suggests that the signal is obscured by noise and difficult to distinguish. Lower noise levels and higher SNR values correspond to better image quality.

Since noise and SNR may vary depending on the region of interest (ROI) settings, we analyzed the entire image using the NumPy, pydicom, cv2, and pywt packages in Python (version 3.7.9) used in previous studies.19 Noise estimation was performed using a method based on hybrid discrete wavelet transform combined with edge information removal-based algorithm. This approach assumes that noise energy is evenly distributed across all wavelet sub-bands, whereas image signal energy is primarily concentrated in the low-low, low–high, and high-low sub-bands.20 SNR was then calculated by dividing the mean signal of the slice by the estimated noise levels given in the standard deviation (SD).

Metal artifacts were evaluated both qualitatively and quantitatively. For visual assessment, two radiologists with 15 and 25 years of experience, respectively, independently rated artifact severity using a 5-point ordinal scale (1 = severe artifacts, 5 = minimal artifacts). To assess inter-observer agreement for the 5-point ordinal visual scores, Cohen’s kappa was used. The average score from the two readers was used for subsequent analysis. Quantitative evaluation was performed using binarization methods described in previous studies21,22,23 and was performed by an oral radiologist with 25 years of experience using ImageJ software (version 1.54 g; NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA; available at https://imagej.net/ij/download.html). A 5 × 5 cm square ROI encompassing the crown was placed at the center of each image, and four 1 × 1 cm square ROIs were positioned immediately outside the corners of the central ROI. The mean and SD of the signal intensity within the four small ROIs were calculated. The maximum (max) threshold and minimum (min) threshold were defined as the mean plus three SD and the mean minus three SD, respectively. Binarization was then performed using these calculated thresholds. Following binarization, the black areas including the crown were defined as metal artifacts, and these black regions were automatically calculated as a percentage of the total ROI (Supplementary Fig. 1). All images were independently analyzed twice with a washout interval of one month, and the average of the two measurements was used for all reported results. The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) was used to evaluate the intraobserver agreement.

Results

Conventional and DL axial T1- and T2-weighted images of the four crowns are presented in Fig. 4. For image quality, DL images demonstrated reduced noise and increased SNR compared to conventional images for all four crowns in both the T1- and T2-weighted sequences (Fig. 5).

For metal artifacts, visual assessment revealed no difference in artifact severity between conventional and DL images across all crown types and sequences. The average visual scores were identical for both methods (e.g., zirconia: 4.5/4.5; PMMA: 4.5/4.5; gold: 4.0/4.0; Ni–Cr: 1.0/1.0). The Cohen’s kappa value of the qualitative evaluation by two people was 0.429 (moderate). These findings suggest that DL reconstruction does not increase the visual extent of metal artifacts compared to conventional reconstruction (Table 3).

Figure 6 shows the binarized images, in which the black areas represent metal artifacts. Quantitative results are summarized in Table 3. Intra-observer reproducibility was excellent, with an ICC of 1.0 (95% CI 0.999–1.000; p < 0.001).

In DL images, metal artifacts increased in the following order: zirconia, PMMA, gold, and Ni–Cr metal across all T1- and T2-weighted sequences. In both the conventional and DL images, Ni–Cr metal exhibited the most extensive metal artifacts, accounting for 47.36% and 59.41% in the T1-weighted sequence and 69.16% and 78.89% in the T2-weighted sequence, respectively. Only in the T2-weighted sequence of the zirconia crown did the DL images reduce metal artifacts compared to the conventional images, decreasing from 10.38% to 9.31%.

Discussion

In this phantom pilot study, DL reconstruction in MRI of various implant crowns improved overall image quality but did not consistently reduce metal artifacts. Across all crown types, DL images demonstrated higher SNR compared to conventional images. Both conventional and DL reconstructions showed a similar material-dependent pattern, with zirconia and PMMA exhibiting fewer artifacts and Ni–Cr metal crowns producing the most pronounced artifacts. However, no consistent reduction in metal artifacts was observed in the DL images.

MRI is increasingly used in the head and neck region and is expanding its applications in dentistry. Recently, the concept of a dedicated dental MRI system utilizing a 0.55 T MRI scanner has been introduced.2 Studies have reported the use of MRI to detect inflammation in the periodontal tissues,24 as well as attempts to quantitatively assess temporomandibular joint disorders using the IDEAL-IQ sequence.25,26 MRI has been shown to have similar or higher accuracy compared to CBCT for evaluating tooth and root canal anatomy, pulp vitality, and periapical lesions, suggesting its potential utility in endodontics.27 However, as the average human lifespan increases and the population ages, the number and types of prostheses, including implants, present in the oral cavity are also rising. This trend contributes to increased metal artifacts and decreased image quality on MRI, and ultimately reduced diagnostic capabilities.

To reduce metal artifacts in MRI, several imaging parameters can be optimized, such as increasing the matrix size and decreasing the slice thickness.28 Additionally, positioning the long axis of the metal object parallel to the main magnetic field can help minimize distortion. Because metal artifacts typically appear along the frequency-encoding direction, swapping the frequency- and phase-encoding direction may also reduce artifact severity.28 Specialized sequences, such as SEMAC and MAVRIC, have been developed to further address this issue. SEMAC reduces artifacts by adding additional phase-encoding steps along the Z-axis to a conventional 2D spin-echo sequence, and incorporates view angle tilting (VAT) to correct in-plane distortions. MAVRIC, which is based on 3D imaging, divides the frequency spectrum into multiple narrow bands, acquires separate images at different frequency offsets, and combines them into a single composite image.7,8,9,10 However, these techniques have the disadvantages of prolonging acquisition time and potentially degrading overall image quality.

Recently, DL techniques that enhance image quality by denoising and reconstructing undersampled k-space data using neural networks trained on high-resolution images have been increasingly adopted in clinical practice.11,12,13,14,15,16,17 These methods effectively improve overall image sharpness and reduce scan time. However, as they are not specifically designed for metal artifact correction, their effectiveness in reducing such artifacts remains unclear. DL reconstruction is now being extended beyond conventional T1- and T2-weighted sequences to a broader range of MRI protocols. Nonetheless, it is not yet applicable to dedicated metal artifact reduction techniques such as SEMAC and MAVRIC.

To our knowledge, this pilot phantom study is the first to quantitatively evaluate not only image quality but also metal artifacts in DL-reconstructed MRI of dental implant crowns using conventional T1- and T2-weighted sequences.

Regarding image quality, DL images demonstrated improvements irrespective of crown type in both T1- and T2-weighted sequences. As expected based on the principles of DL reconstruction, DL techniques have been shown to reduce noise and increase SNR compared to conventional methods. Among the four crown types, Ni–Cr metal crowns exhibited the highest noise and the lowest SNR. As noise increases, the image becomes more inhomogeneous, the SNR decreases, and overall image quality deteriorates, making it more difficult to assess the true signal intensity of lesions. Shimamoto et al.29 evaluated image uniformity in T1-weighted sequences by embedding six metallic materials (Au, Ag, Al, Au–Ag–Pd alloy, titanium, and Co–Cr alloy) in phantoms. They reported that Co–Cr alloy and titanium produced image inhomogeneity. Although this inhomogeneity had little impact on assessing the presence of tumors in the oral and maxillofacial region, it did affect the evaluation of inflammatory disease progression, such as osteomyelitis, in which signal intensity plays a critical role as a diagnostic indicator. Therefore, we believe that the improved image quality achieved through noise reduction and increased SNR in DL images, regardless of crown type, will be valuable for signal assessment of lesions, including inflammatory diseases.

Regarding metal artifacts, visual assessment appeared to be no difference in the extent of metal artifacts between conventional and DL images. In DL images, metal artifacts increased in the order of zirconia, PMMA, gold, and Ni–Cr metals in both T1- and T2-weighted sequences, showing the same trend reported in previous studies using conventional images.23 Quantitatively, DL images showed a slight reduction only for zirconia crowns in the T2-weighted sequence (conventional: 10.38% vs. DL: 9.31%), whereas all other crown types exhibited higher values. DL reconstruction methods are post-processing denoising techniques developed primarily to improve image quality and reduce scan time, unlike SEMAC and MAVRIC, which are sequence-based techniques specifically designed to reduce metal artifacts,. Therefore, DL reconstruction is not expected to produce significant improvements in metal artifact reduction. Also, increases of most artifact ratio may reflect bias inherent to the binarization method employed for artifact measurement. Because DL reconstruction reduces image noise through denoising, the SD of signal intensity decreases, resulting in narrower threshold ranges for binarization compared with conventional images. This methodological limitation may have affected the measured artifact values. Although the quantitative approach may introduce a bias that disadvantages DL images, visual assessment indicates that DL reconstruction does not increase metal artifacts. Direct comparisons of metal artifacts between DL and conventional reconstructions using this approach should be interpreted with caution, underscoring the need to develop new quantification methods specifically optimized for DL reconstructed images. Although limited in scope, this study is the first to quantitatively assess metal artifacts in DL reconstructed dental MRI. It serves as a pilot investigation that lays a methodological foundation for future studies incorporating more advanced analytical techniques and clinical validation.

This study has several limitations. First, crown-related artifacts may vary depending on MRI equipment and magnetic field strength (e.g., 1.5 T vs. 3 T), so evaluation under different configurations is warranted. Second, only axial images were analyzed, and further assessment of coronal and sagittal images is needed. Third, as the current analysis was performed using phantoms, validation in clinical settings is essential. In vivo conditions—such as complex anatomical structures, tissue–air interfaces, patient motion, and magnetic field inhomogeneity—may further influence artifact behavior and DL reconstruction performance. These factors highlight the need for future clinical studies.

Conclusions

This pilot phantom study evaluated DL reconstruction applied to MRI of dental implant crowns. DL reconstruction improved image quality across crown types but did not consistently reduce metal artifacts. These findings highlight both the potential and the current limitations of DL reconstruction in dental MRI. Moving forward, DL techniques should be further developed not only to enhance image quality but also to effectively reduce metal artifacts.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

References

Lam, E., Mallya, S. White and pharoah’s oral radiology: principles and interpretation. (Elsevier Health Sciences, 2025).

Greiser, A. et al. Dental-dedicated MRI, a novel approach for dentomaxillofacial diagnostic imaging: Technical specifications and feasibility. Dentomaxillofac. Radiol. 53(1), 74–85 (2024).

Schenck, J. F. The role of magnetic susceptibility in magnetic resonance imaging: MRI magnetic compatibility of the first and second kinds. Med. Phys. 23(6), 815–850 (1996).

Koch, K. M. et al. Magnetic resonance imaging near metal implants. J. Magn. Reson. Imag. 32(4), 773–787 (2010).

Johannsen, K. M., Christensen, J., Matzen, L. H., Hansen, B. & Spin-Neto, R. Interference of titanium and zirconia implants on dental-dedicated MR image quality: ex vivo and in vivo assessment. Dentomaxillofac. Radiol. 54(2), 132–139 (2025).

Li, W. et al. Performance of PROPELLER FSE T2WI in reducing metal artifacts of material porcelain fused to metal crown: a clinical preliminary study. Sci Rep. 12(1), 8442. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-12402-2 (2022).

Hilgenfeld, T. et al. MSVAT-SPACE-STIR and SEMAC-STIR for reduction of metallic artifacts in 3T head and neck MRI. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 39(7), 1322–1329 (2018).

Lee, Y. H. et al. Usefulness of slice encoding for metal artifact correction (SEMAC) for reducing metallic artifacts in 3-T MRI. Magn. Reson. Imag. 31(5), 703–706 (2013).

Koch, K. M. et al. Imaging near metal with a MAVRIC-SEMAC hybrid. Magn. Reson. Med. 65(1), 71–82 (2011).

Lu, W., Pauly, K. B., Gold, G. E., Pauly, J. M. & Hargreaves, B. SEMAC: slice encoding for metal artifact correction in MRI. Magn. Reson. Med. 62(1), 66–76 (2009).

Kiryu, S. et al. Clinical impact of deep learning reconstruction in MRI. Radiographics 43(6), e220133. https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.220133 (2023).

Almansour, H. et al. Deep learning reconstruction for accelerated spine MRI: prospective analysis of interchangeability. Radiology 306(3), e212922. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.212922 (2022).

Dratsch, T. et al. Reconstruction of shoulder MRI using deep learning and compressed sensing: a validation study on healthy volunteers. Eur. Radiol. Exp. 7(1), 66. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41747-023-00377-2 (2023).

Johnson, P. M. et al. Deep learning reconstruction enables prospectively accelerated clinical knee MRI. Radiology 307(2), e220425. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.220425 (2023).

Kaniewska, M. et al. Application of deep learning–based image reconstruction in MR imaging of the shoulder joint to improve image quality and reduce scan time. Eur. Radiol. 33(3), 1513–1525 (2023).

Yoo, H. et al. Deep learning–based reconstruction for acceleration of lumbar spine MRI: a prospective comparison with standard MRI. Eur. Radiol. 33(12), 8656–8668 (2023).

Lee, S. et al. Comparative analysis of image quality and interchangeability between standard and deep learning-reconstructed T2-weighted spine MRI. Magn. Reson. Imag. 109, 211–220 (2024).

Jo, G. D., Jeon, K. J., Choi, Y.J., Lee, C.& Han, S. S. Deep learning reconstruction for temporomandibular joint MRI: diagnostic interchangeability, image quality, and scan time reduction. Eur. Radiol. 25, (2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-025-12029-7 (Online ahead of print).

Son, J. H. et al. LAVA HyperSense and deep-learning reconstruction for near-isotropic (3D) enhanced magnetic resonance enterography in patients with Crohn’s disease: Utility in noise reduction and image quality improvement. Diagn. Interv. Radiol. 29(3), 437–449 (2023).

Pimpalkhute, V. A., Page, R., Kothari, A., Bhurchandi, K. M. & Kamble, V. M. Digital image noise estimation using DWT coefficients. IEEE Trans. Imag. Process. 30, 1962–1972 (2021).

Cortes, A. R., Abdala-Junior, R., Weber, M., Arita, E. S. & Ackerman, J. L. Influence of pulse sequence parameters at 1.5 T and 3.0 T on MRI artefacts produced by metal–ceramic restorations. Dentomaxillofac. Radiol. 44(8), 20150136. https://doi.org/10.1259/dmfr.20150136 (2015).

Klinke, T. et al. Artifacts in magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography caused by dental materials. PLoS ONE 7(2), e31766. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0031766 (2012).

Gao, X., Wan, Q. & Gao, Q. Susceptibility artifacts induced by crowns of different materials with prepared teeth and titanium implants in magnetic resonance imaging. Sci Rep. 12(1), 428. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-03962-w (2022).

Probst, M. et al. Magnetic resonance imaging as a diagnostic tool for periodontal disease: a prospective study with correlation to standard clinical findings-Is there added value?. J. Clin. Periodontol. 48(7), 929–948 (2021).

Jeon, K. J., Lee, C., Choi, Y. J. & Han, S. S. Assessment of bone marrow fat fractions in the mandibular condyle head using the iterative decomposition of water and fat with echo asymmetry and least-squares estimation (IDEAL-IQ) method. PLoS ONE 16(2), e0246596. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0246596 (2021).

Jeon, K. J., Choi, Y. J., Lee, C., Kim, H. S. & Han, S. S. Evaluation of masticatory muscles in temporomandibular joint disorder patients using quantitative MRI fat fraction analysis—Could it be a biomarker?. PLoS ONE 19(1), e0296769. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0296769 (2024).

Candemil, A. P. et al. Accuracy of magnetic resonance imaging in clinical endodontic applications: a systematic review. J. Endod. 50(4), 434–449 (2024).

Jungmann, P. M., Agten, C. A., Pfirrmann, C. W. & Sutter, R. Advances in MRI around metal. J. Magn. Reson. Imag. 46(4), 972–991 (2017).

Shimamoto, H. et al. Effect of metallic materials on magnetic resonance image uniformity: a quantitative experimental study. Oral. Radiol. 41(1), 78–87 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Yonsei University College of Dentistry Fund (6-2023-0005).

Funding

Yonsei University College of Dentistry, 6-2023-0005.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors gave their final approval and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work. S.H. proposed the ideas; K.J. and H.J. collected data; K.J., C.L. and J.L. analyzed and interpreted data; K.J., H.J., C.L., J.L. and S.H. drafted and critically revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jeon, K.J., Jeong, H., Lee, C. et al. Evaluation of deep learning MRI reconstruction for dental implant crowns in a phantom study. Sci Rep 16, 1172 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30934-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30934-1