Abstract

Despite the widespread availability of sphygmomanometers, hypertension remains underdiagnosed and poorly controlled globally—largely due to its asymptomatic onset, low screening adherence, and measurement biases such as white-coat hypertension. Current methods fail to enable scalable, passive, and early detection in real-world settings. To develop a non-invasive, camera-based screening approach using deep learning that overcomes these barriers by enabling early, accessible, and interpretable hypertension detection through facial image analysis. We analyzed facial images from 375 hypertensive patients and 131 normotensive controls. An improved U-Net model was employed to segment the face into six anatomically defined regions. Subsequently, ResNet-based classifiers were trained to predict hypertension using either the whole face or individual facial regions as input. The segmentation achieved a high mIoU of 98.43%. The whole-face model achieved 83% accuracy. Notably, models using only the zygomatic and cheek regions achieved 82% accuracy each—performing on par with the full-face model. This suggests these regions contain concentrated physiological signals associated with hypertension, potentially linked to microvascular or perfusion changes. This study demonstrates that deep learning analysis based on facial images can serve as a scalable, passive, non-invasive initial screening tool, operable in everyday environments using only standard cameras. Notably, the zygomatic and buccal regions exhibit specificity in identifying hypertension.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hypertension is one of the most prevalent chronic non-communicable diseases worldwide and may result in long-term cardiac overload1, substantially increasing the risk of myocardial infarction, coronary artery disease, and heart failure, thereby posing a serious threat to human health2. However, most patients remain asymptomatic in the early stages, hindering timely detection. As a result, many individuals seek medical care only after disease progression, by which point damage to the heart, kidneys, or brain may already have occurred, leading to severe outcomes such as stroke, disability, or death3. Thus, early identification and intervention are essential for preventing or delaying target organ complications, reducing morbidity and mortality, and improving long-term prognosis.

Currently, the diagnosis of hypertension relies primarily on blood pressure measurement. Although this method is clinically validated and widely implemented, its effectiveness in real-world practice remains limited. Epidemiological data indicate that the early detection rate of hypertension is still below 50%4. Multiple factors contribute to this gap. In clinical settings, some patients experience “white-coat hypertension,” in which blood pressure rises abnormally during medical visits but remains normal in daily life, increasing the risk of misdiagnosis. At home, elderly individuals often face difficulties operating electronic sphygmomanometers, while younger adults frequently neglect routine self-monitoring. Other non-invasive techniques such as photoplethysmography (PPG) can estimate blood-pressure trends, but they still require contact sensors and are susceptible to motion artifacts and ambient light interference. These limitations highlight a critical public health challenge: despite the widespread availability of blood pressure devices, a substantial proportion of hypertension cases remain undiagnosed. Key reasons include low screening adherence, the asymptomatic onset of the disease, and measurement biases. Consequently, there is an urgent need for a low-cost, highly accessible, and passive screening approach capable of proactively identifying high-risk individuals during the “silent” phase of hypertension, thereby addressing the “first-mile” gap in the current diagnostic and management pathway.

According to Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) theory, the facial appearance reflects internal physiological and pathological states, with different facial regions corresponding to distinct visceral organs. Recent studies have demonstrated associations between facial features and cardiovascular diseases5,6. Facial image analysis, as a non-invasive and convenient approach, therefore holds considerable promise5. With the rapid development of deep learning, computer vision techniques now enable highly precise identification and analysis of facial characteristics, offering an efficient tool for health monitoring. Deep learning, as a core branch of artificial intelligence, has advanced significantly in medical image analysis7,8. By constructing and training deep neural networks, it is possible to automatically extract and interpret image features, thereby enhancing both diagnostic accuracy and efficiency. In facial analysis, such models can detect subtle changes imperceptible to the human eye, facilitating early disease identification.

Prior work in facial image analysis has explored various methods for health and non-health applications. For instance, HOG-based feature extraction has been applied to facial expression recognition, demonstrating that handcrafted features can capture basic facial patterns but often lack robustness in complex or noisy environments9. Similarly, Haar cascade classifiers have been used for face mask detection during the COVID-19 pandemic, offering an efficient solution for binary classification tasks10. However, as highlighted by studies such as A Framework for Recognition of Facial Expression Using HOG Features11 and Face Mask Detection Using Haar Cascades Classifier To Reduce The Risk Of Coved-1912, these traditional computer vision approaches rely on handcrafted features and rigid templates, which are limited in representational capacity and generalizability—especially in medical contexts where subtle, morphologically complex patterns must be identified.

These limitations underscore a critical research gap: prior approaches largely rely on handcrafted features or global facial representations, while the diagnostic value of region-specific facial characteristics remains underexplored. Although existing deep learning-based research supports the feasibility of facial image analysis for cardiovascular disease detection, many studies treat the face as a holistic input without incorporating region-aware processing13. This strategy may overlook localized yet clinically meaningful facial cues—consistent with TCM theory—and often reduces the interpretability of model predictions.

To address this gap, we propose a deep learning framework that integrates anatomical region segmentation with region-specific classification, aiming to establish a novel paradigm for hypertension screening that is device-free, non-invasive, and independent of clinical settings. The framework first employs an improved U-Net model to segment facial images into six anatomically defined regions (e.g., forehead, periorbital, nasal, zygomatic, cheek, and mandibular). Subsequently, ResNet-based classifiers are trained independently for each region to evaluate its individual capability in predicting hypertension. Unlike conventional approaches that treat the face as a holistic input, our method emphasizes a systematic comparison of the diagnostic performance across distinct facial subregions. This “divide-and-analyze” strategy enables not only the identification of the most discriminative facial zones, but also the exploration of localized visual biomarkers—such as microcirculatory changes, pigmentation, or subtle edema—that may be associated with hypertensive pathophysiology.

Notably, this approach can help mitigate measurement biases such as “white-coat hypertension,” enabling passive, frequent, and scalable screening in real-world settings. It provides a valuable complement to existing diagnostic methods such as sphygmomanometry and PPG, thereby addressing practical challenges including low screening adherence and insufficient monitoring frequency.

The main contributions of this study are summarized as follows:

① We conduct the first systematic evaluation of six anatomical facial regions in hypertension recognition, revealing that the zygomatic and cheek regions achieve classification accuracies of 82%—comparable to the whole-face model (83%). This finding suggests that specific facial subregions may contain concentrated visual biomarkers of hypertension, paving the way for privacy-preserving, region-focused mobile health applications.

② By integrating TCM facial diagnosis principles with model interpretability analysis, we observe a strong alignment between the high-contribution regions (e.g., cheek, periorbital) and TCM’s face-organ correspondence (e.g., cheek for heart/lung, periorbital for kidney). This physiologically interpretable insight enhances clinical trust and provides data-driven support for the modernization of TCM theories.

③ Experimental results demonstrate that lightweight models (e.g., ResNet-18) outperform deeper architectures (e.g., ResNet-50) in region-specific tasks, indicating superior efficiency and generalization under limited medical data. This supports the deployment of our framework on mobile or edge devices, enabling low-cost, large-scale community-based hypertension screening.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section “Method” describes the data sources, diagnostic criteria, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and model training methods, including the improved U-Net segmentation model, the ResNet-based classification model, the experimental environment, and interpretability analysis. Section “Workflow overview” presents the experimental results on multi-region facial segmentation, hypertension classification performance, and interpretability analysis. Section “Data sources” discusses the implications of our findings and their relevance to clinical practice. Section “Diagnostic criteria” concludes the paper. Finally, the manuscript ends with the ethics statement, author contributions, and references.

Method

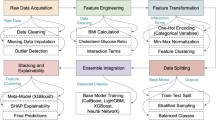

Workflow overview

This study followed a five-stage pipeline. First, high-resolution facial images were acquired under standardized lighting conditions using professional equipment, and low-quality images were excluded. Pixel-level manual annotations were then performed to generate ground-truth masks. Second, an improved U-Net model with a VGG-16 encoder was employed to segment six facial regions: forehead, zygoma, cheeks, nose, lips, and jaw. Third, the segmented regional images as well as whole-face images were fed into ResNet models for hypertension classification. To address class imbalance (375 hypertensive vs. 131 healthy controls), we applied weighted binary cross-entropy (weights: 0.64 and 1.91), label smoothing (α = 0.3), and data augmentation (random cropping and horizontal flipping). Finally, model performance was evaluated using metrics such as accuracy, AUC, and mIoU, and Grad-CAM visualization was applied to highlight the facial regions most influential in the predictions.

Data sources

This study was conducted as part of the National Key Research and Development Program project ‘Key Technologies and Equipment for Intelligent Acquisition and Analysis of Head Facial Inspection and Complexion Information’ (2022YFC3502301). Data were collected from both outpatient and inpatient of Cardiovascular Medicine at Dongzhimen Hospital, Beijing University of Chinese Medicine. A total of 375 hypertensive patients diagnosed between August and December 2023 were included. The healthy control group comprised 131 participants, primarily recruited from university students, hospital staff, and patients’ relatives. This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Dongzhimen Hospital, (approval number: 2023DZMEC-228-03).

Diagnostic criteria

Diagnostic criteria for hypertension were based on internationally recognized guidelines, including NICE, 2013 ESH/ESC, and JNC714,15. Hypertension is diagnosed if multiple measurements obtained on different days show a systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mmHg and/or a diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mmHg, in the absence of antihypertensive therapy, with secondary hypertension is excluded.

Healthy controls were defined according to the World Health Organization’s ten health standards (2000), which include physical vitality, emotional stability, adequate sleep, strong adaptability, balanced physique, good mobility, preserved vision and reflexes, healthy dentition, and normal skin, hair, and musculature. Individuals meeting these standards and lacking significant family histories of hereditary or chronic disease were considered healthy16.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Eligible hypertensive participants were required to meet established diagnostic criteria for hypertension and provide complete data. Healthy participants were required to meet World Health Organization (WHO) criteria for normal health status, including normotension and absence of major chronic diseases, and to provide complete data. Additional criteria included: (1) confirmed hypertension without medication, or hypertension uncontrolled by medication; (2) age between 18 and 80 years; (3) provision of informed consent by the participant or a close relative.

Exclusion criteria included: secondary hypertension; stable hypertension controlled for more than one year; recent use (within one month) of medications affecting facial complexion (e.g., beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers, diuretics); facial skin defects, dermatological conditions, or significant pigmentation; major cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, hepatic, renal, or psychiatric disorders; recent infections, trauma, surgery, or fever; pregnancy or lactation; inability to cooperate during data collection; incomplete clinical or demographic data; or any condition deemed unsuitable by investigators.

Information collection

Participants who met the inclusion criteria were recruited after being provided with detailed information about the study objectives, procedures, and potential discomforts. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Data were collected on demographic characteristics, lifestyle factors, medical history, and family history.

Blood pressure was measured after participants rested for 3–5 min in a seated position, using a calibrated upper-arm electronic sphygmomanometer. Three measurements were taken at one-minute intervals, and the average of the final two readings was recorded.

Facial images were captured under standardized artificial lighting using the DS01-B Tongue and Facial Diagnostic Information Collection System and the M3 TCM Smart Screen All-in-One System. Equipment was calibrated prior to use. Participants sat upright with neutral facial expressions and standard posture, under stable lighting conditions (Fig. 1).

Image processing and model development

Preprocessing and annotation

Images with obstructions, poor illumination, or improper posture were excluded. Facial regions (whole face, forehead, zygoma, cheek, nose, lips, jaw) were manually annotated by trained staff using Labelme software following TCM diagnostic regions. Masks were stored in JSON format as ground truth for segmentation.

Segmentation model

Data were randomly split into training and testing sets at a 9:1 ratio. U-Net, a deep learning architecture proposed by Ronneberger, was adopted for medical image segmentation17. Its encoder–decoder structure enables efficient feature extraction and restoration of spatial details, making it particularly suitable for small-sample biomedical datasets. To improve performance, a VGG network was integrated into the encoder, enhancing generalization and feature extraction from subtle local variations (e.g., between cheeks and zygoma)18.

Segmentation performance was quantitatively assessed using mean Intersection over Union (mIoU), mean Pixel Accuracy (mPA), and overall Accuracy (ACC), in addition to visual inspection. Model parameters are summarized in Table 1, and the architecture is illustrated in Fig. 2.

Classification model

Prior to classification, categorical labels were numerically encoded: hypertensive patients as (1) and healthy controls as (0). The dataset was randomly split into training and test sets in an 8:2 ratio, with a fixed random seed (2024) to ensure reproducibility. Given the limited dataset size and class imbalance (375 hypertensive vs. 131 healthy controls), data augmentation was applied to enhance generalization. Augmentations included random cropping and horizontal flipping. Training images were resized to 224 × 224 pixels, converted to tensors, and normalized using ImageNet mean and standard deviation ([0.485, 0.456, 0.406], [0.229, 0.224, 0.225]); validation images underwent center cropping with identical normalization. ResNet was selected due to its residual learning framework19, which alleviates vanishing gradients and degradation in deep networks17. Its hierarchical architecture is well-suited for capturing subtle facial phenotypic differences associated with hypertension. We evaluated ResNet-18, ResNet-34, and ResNet-50 to investigate the impact of network depth on performance (current results based on ResNet-18).

All models were initialized with ImageNet pre-trained weights and fine-tuned using the Adam optimizer with OneCycleLR learning rate scheduling (maximum learning rate = 2 × 10⁻⁴). The batch size was set to 32, and training was conducted for 100 epochs. Model weights were saved at the epoch with the highest validation accuracy.

To address class imbalance, class weights were computed as:

where \(\:N\) =506 is the total number of samples and \(\:{N}_{c}\) is the number of samples in class.

\(\:C\). This yielded weights of 0.64 for the hypertensive group and 1.91 for healthy controls. These weights were incorporated into a custom weighted binary cross-entropy loss (WeightedBCEWithLogitsLoss) to increase the contribution of the minority class during training. Additionally, label smoothing (α = 0.3) was applied by softening one-hot encoded labels, which helps prevent overfitting and improves model calibration. Although focal loss(γ = 2.0,α = 0.25)was implemented during preliminary experiments, it did not outperform the weighted BCE with label smoothing in terms of accuracy and training stability, and was therefore not used in the final model.

The final strategy combined class-weighted loss, label smoothing, and data augmentation to effectively mitigate class imbalance and ensure stable training.

In this study, the model’s performance was comprehensively evaluated using standard image classification metrics, including ACC, Precision, Recall, F1 score, AUC, and confusion matrices. Additionally, five-fold cross-validation was used to validate the robustness of the model.

Interpretability analysis

To improve interpretability, we applied Grad-CAM to visualize the regions most influential in model predictions. Saliency maps were generated for correctly classified hypertensive and control samples. This allowed us to identify discriminative facial regions while ensuring alignment with clinical and TCM perspectives.

Experimental environment

Experiments were conducted on a server configured with an Intel 6230 CPU, NVIDIA Tesla V100S (32 GB) GPU, and Ubuntu 20.04.5 operating system. The models were implemented in Python 3.10 using PyTorch 1.8.

Results

Segmentation of multiple facial regions

The primary objective of this experiment was to evaluate whether the proposed U-Net model with VGG backbone and transfer learning could accurately and robustly segment hypertension-relevant facial regions, providing a reliable foundation for subsequent classification. Accurate delineation of anatomically meaningful zones—such as the forehead, nose, zygomatic area, and jaw—is critical, as these regions are hypothesized to exhibit subtle color and texture changes associated with cardiovascular status, particularly in the context of TCM.

As shown in Table 2 and visualized in Fig. 3, the model achieved excellent performance in segmenting the entire face, with an mIoU of 98.35%, mean Pixel Accuracy (mPA) of 99.22%, and overall accuracy of 99.34%. The predicted masks exhibit smooth boundaries and high fidelity to ground truth, demonstrating strong robustness to variations in facial shape, pose, and illumination. This indicates that the model effectively captures global facial structure, which is essential for consistent region localization across diverse subjects.

At the regional level, the model also performed well. The forehead was segmented with an mIoU of 94.31% and accuracy of 99.37%; the nose with 92.88% mIoU and 99.59% accuracy; and the lips with 93.51% mIoU and 99.86% accuracy. These results suggest that the model can reliably isolate regions with relatively clear boundaries and distinct color contrasts.

However, segmentation performance was moderately lower in more anatomically complex regions: the zygomatic area achieved an mIoU of 85.07%, and the jaw reached 88.02%. This performance gap is likely attributable to greater contour variability, subtler texture transitions, and shading effects under non-uniform lighting, which make precise boundary definition more challenging. Despite this, the segmentation remained visually coherent and functionally sufficient for downstream classification, as misclassified pixels were typically confined to marginal areas with minimal diagnostic impact.

Notably, the model converged within 20 epochs using transfer learning, significantly reducing training time and computational cost. This rapid convergence underscores the effectiveness of pretraining on natural image data (ImageNet) for initializing facial segmentation tasks, even with a relatively small medical dataset.

In summary, these results validate that our U-Net–based framework can accurately isolate key facial zones relevant to hypertension analysis. While performance in complex regions suggests room for improvement, the current segmentation quality is robust and sufficient to support region-specific feature extraction in the classification stage.

Hypertension classification and diagnosis model

ResNet models were fine-tuned for hypertension classification using both whole-face and region-specific facial inputs, with training conducted over 100 epochs and early stopping applied to prevent overfitting. In the whole-face analysis, ResNet-18 achieved the highest accuracy of 83% with stable convergence (loss reduced to 0.33), demonstrating that global facial features contain discriminative information sufficient for hypertension screening (Table 2; Figs. 4A and 5A). This model was therefore established as the performance benchmark for subsequent regional comparisons.

When evaluating individual facial regions, several areas showed strong diagnostic potential. The zygomatic region achieved 82% accuracy using ResNet-34, a result comparable to the whole-face model (Table 2; Figs. 4C and 5C), suggesting that this anatomically distinct zone may capture hypertension-related physiological signals—such as microvascular changes or localized blood flow patterns—highly relevant to cardiovascular status. Similarly, the cheek region reached 82% accuracy with ResNet-18 (Table 2; Figs. 4D and 5D), further supporting the value of lateral facial zones in non-invasive screening. These findings indicate that specific facial subregions may independently contribute meaningful information, beyond what is captured by global averaging.

For the forehead, ResNet-18 achieved 78% accuracy, outperforming ResNet-34 and ResNet-50 (both 76%) (Table 2; Figs. 4B and 5B). However, ResNet-50 exhibited more consistent performance across cross-validation folds, highlighting a trade-off between peak accuracy and model stability—important considerations for real-world deployment. In the nose region, ResNet-50 achieved the highest accuracy at 77% (Table 2; Figs. 4E and 5E), potentially due to its rich vascular network and stable texture, which may benefit deeper architectures in extracting subtle physiological cues. The jaw region also performed relatively better with ResNet-34 (77% accuracy) (Table 2; Figs. 4G and 5G), likely because medium-depth networks better handle its complex contour and shading variations. In contrast, the lip region achieved 73% accuracy with ResNet-18 (Table 2; Figs. 4F and 5F)—the lowest among all regions—possibly due to external factors such as lipstick, dryness, or color variation, though the model showed stable generalization across test sets.

These results collectively demonstrate that while whole-face analysis with ResNet-18 remains optimal, certain localized regions—particularly the zygoma and cheek—achieve performance close to the global model, reinforcing their potential as targets for region-focused, interpretable hypertension screening tools.

When comparing the best-performing models across regions (Table 3; Fig. 6), whole-face analysis with ResNet-18 remained optimal. However, the zygoma (ResNet-34) and cheek (ResNet-18) models demonstrated comparable accuracy, emphasizing their clinical potential for regional diagnostics.

Confusion matrix analysis (Fig. 7) provided an intuitive assessment of each model’s classification performance. The Overall Facial Area ResNet-18 model achieved a high number of true positives (TP = 270) with a moderate number of false positives (FP = 63), indicating a balanced trade-off between sensitivity and specificity. The Forehead Area ResNet-50 model achieved a comparable TP (263) but with substantially more FP (118), reflecting lower specificity. The Zygomatic Area ResNet-34 and Cheek Area ResNet-18 models exhibited low FP rates (76 and 7, respectively); however, the Cheek model had a high number of false negatives (FN = 202), resulting in reduced recall. The Nose Area ResNet-50 model produced almost no FP (0) but a very low TP (14), while the Jaw Area ResNet-34 model maintained low FP (7) but only moderate TP (101). The Lip Area ResNet-18 model identified the highest TP (323) but at the cost of a relatively high FP (84).

In summary, the confusion matrix analysis further confirms the superior and well-balanced performance of the whole-face model. It also suggests that, in addition to global facial features, the zygomatic and cheek regions may contain valuable physiological signals associated with hypertension, warranting further investigation into their underlying mechanisms for clinical screening applications.

To further contextualize the effectiveness of our proposed approach, we compared its diagnostic performance with representative state-of-the-art non-invasive methods, as summarized in Table 4. Specifically, traditional statistical models based on facial complexion (CIELAB color space) achieved AUC values around 0.82–0.83, while contact-based PPG morphology classification methods reported an accuracy of approximately 0.73. Our framework, which integrates U-Net–based facial region segmentation with ResNet-18 classification, achieved an accuracy of 0.83, F1-score of 0.75, and AUC of 0.84 on 506 images. These results demonstrate that our non-contact, deep learning–based model performs on par with or better than existing non-invasive techniques. Moreover, compared with contact-dependent approaches such as PPG, our method offers the advantage of convenience and broader applicability in real-world clinical or community settings, highlighting its potential as a promising tool for large-scale hypertension screening.

Interpretability analysis

Grad-CAM visualizations revealed that the model primarily focused on the zygomatic and cheek regions when distinguishing hypertensive patients from controls. Importantly, these areas are clinically relevant, as they correspond to facial manifestations commonly emphasized in TCM, such as zygomatic discoloration and cheek redness. This finding indicates that the model is not only learning abstract image patterns but also capturing physiologically meaningful features that align with both biomedical knowledge and TCM diagnostic principles, thereby enhancing the credibility and interpretability of its decision-making process.

Moreover, this observation suggests that interpretability analysis can serve as a valuable tool for clinicians to assess the rationality of AI-assisted diagnosis, thereby strengthening trust in such systems. It also provides a pathway for future interdisciplinary research—linking model attention maps with traditional diagnostic experience to further explore underlying pathophysiological mechanisms. This dual alignment enhances the clinical applicability of the model and lays a foundation for deeper integration between artificial intelligence and TCM diagnostic practices.

Discussion

This study validated the feasibility of deep learning–based facial image analysis for non-invasive hypertension screening. By combining an improved U-Net for segmentation with ResNet classifiers, we systematically evaluated six anatomically defined facial regions. The results demonstrated that the zygomatic and cheek regions achieved diagnostic accuracies (82%) comparable to the whole-face model (83%), suggesting that these local regions may contain concentrated visual biomarkers associated with hypertension. This not only supports the clinical utility of region-specific models but also aligns with the TCM theory of “inspection,” in which facial zones correspond to internal organs, thereby enhancing both interpretability and clinical trust20,21.

Compared with conventional diagnostic approaches22, the proposed method offers multiple advantages. The sphygmomanometer remains the gold standard for hypertension diagnosis, yet its dependence on physical contact, trained personnel, and standardized procedures limits its scalability for population-level or opportunistic screening. PPG is another non-invasive alternative, but it still requires contact sensors and is prone to motion artifacts and ambient light interference23. In contrast, our framework relies solely on facial images to achieve fully contactless, rapid, and convenient hypertension screening. While not intended to replace established clinical measurements, this approach can serve as a valuable complementary tool to address real-world challenges such as low screening adherence and insufficient monitoring frequency. Its scalability further highlights potential applications in telemedicine and community health contexts.

In segmentation tasks, the improved U-Net achieved overall excellent performance (mIoU > 98%)24, particularly in the forehead, lips, and nose regions. However, accuracy was relatively lower in anatomically complex regions such as the zygoma (85%) and jaw (88%), likely due to intricate contours, greater inter-individual variation, and sensitivity to illumination24. Future work should consider advanced strategies such as attention mechanisms or hybrid architectures integrating convolutional and transformer layers to better capture both global and local features.

In classification, the ResNet-18 whole-face model yielded the best performance (83%), confirming the diagnostic value of global facial features. Interestingly, localized models based on the zygoma and cheeks also achieved 82% accuracy, comparable to the full-face model. This finding resonates with TCM diagnostic theory and aligns with modern evidence linking regional vascular changes to systemic conditions20,21. In contrast, models trained on the nose and lips performed less well (77% and 73%), likely due to weaker or less consistent hypertensive manifestations in these regions, as well as greater susceptibility to environmental and emotional factors25. These results suggest that combining multiple facial regions may be necessary for reliable clinical application.

Interpretability analysis further enhanced clinical relevance. Grad-CAM visualizations revealed that the models primarily attended to the zygomatic and cheek regions, which are richly vascularized and highly sensitive to hemodynamic alterations in hypertension26. Subtle changes in skin tone and texture in these areas may provide discriminative cues—consistent with findings from optical imaging studies. From a TCM perspective, these regions are also diagnostically important; for example, expert consensus identifies zygomatic vascular engorgement or stasis as a hallmark of blood stasis constitution27. This convergence across model attention, physiological evidence, and traditional diagnostic knowledge strengthens clinical plausibility and fosters trust in AI-assisted approaches. Interestingly, deeper models (e.g., ResNet-50) did not consistently outperform shallower ones. While ResNet-50 produced more stable cross-validation results, ResNet-18 occasionally achieved superior accuracy in smaller or localized regions. This suggests a trade-off between model complexity and dataset size, where lightweight architectures may generalize better under limited data. Future research should investigate larger and more diverse datasets and explore optimized architectures to balance performance and efficiency28,29.

Despite these promising findings, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, although the sample size is comparable to other medical imaging studies constrained by clinical recruitment and ethical approvals, it remains relatively small for deep learning applications, potentially limiting the generalizability of our models. Second, while segmentation accuracy was high overall, performance in complex regions such as the zygoma and jaw was less robust, highlighting the need for more advanced segmentation strategies. Third, although this study included preliminary comparisons with conventional diagnostic approaches and non-invasive methods, systematic benchmarking remains insufficient and should be addressed in future work. To overcome these limitations, future research should incorporate larger, multi-center, and more diverse cohorts, and explore attention-based or hybrid CNN-transformer architectures to enhance robustness and fairness, ensuring applicability across different ethnicities, genders, and age groups.

Overall, this study provides preliminary yet compelling evidence that deep learning–based facial image analysis can serve as a valuable complement to existing hypertension diagnostic pathways. By bridging modern AI techniques with TCM diagnostic principles, our framework lays the foundation for scalable, interpretable, and clinically meaningful non-contact screening, offering new opportunities for early identification and intervention in hypertension.

Conclusion

Hypertension often goes undetected due to limited access to screening tools and low patient compliance. This study explores a non-invasive, AI-driven approach for early hypertension detection using facial features, inspired by TCM face diagnosis. We found that deep learning models can effectively classify hypertension from facial images, with the zygomatic and cheek regions achieving accuracy (82%) close to that of whole-face analysis (83%). This supports the TCM concept that specific facial zones reflect systemic health and suggests that region-based assessment may enable simpler, more interpretable screening.

By combining modern AI with TCM knowledge, our method offers a convenient and scalable tool for preliminary risk assessment—particularly valuable in primary care and resource-limited settings. While promising, further validation on larger, diverse populations is needed before clinical deployment.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- mIoU:

-

mean Intersection over Union

- mPA:

-

mean Pixel Accuracy

- ACC:

-

Accuracy

References

NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC). Worldwide trends in hypertension prevalence and progress in treatment and control from 1990 to 2019: a pooled analysis of 1201 population-representative studies with 104 million participants. Lancet 398, 957–980 (2021).

Zhou, B., Perel, P., Mensah, G. A. & Ezzati, M. Global epidemiology, health burden and effective interventions for elevated blood pressure and hypertension. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 18, 785–802 (2021).

Selvetella, G. et al. Left ventricular hypertrophy is associated with asymptomatic cerebral damage in hypertensive patients. Stroke 34, 1766–1770 (2003).

Zhou, B. et al. Worldwide trends in hypertension prevalence and progress in treatment and control from 1990 to 2019: a pooled analysis of 1201 population-representative studies with 104 million participants. Lancet 398, 957–980 (2021).

Lin, S. et al. Feasibility of using deep learning to detect coronary artery disease based on facial photo. Eur. Heart J. 41, 4400–4411 (2020).

Xing, W., Shi, Y., Wu, C., Wang, Y. & Wang, X. Predicting blood pressure from face videos using face diagnosis theory and deep neural networks technique. Comput. Biol. Med. 164, 107112 (2023).

Dong, W., Sun, S. & Yin, M. A multi-view deep learning model for pathology image diagnosis. Appl. Intell. 53, 7186–7200 (2023).

Jin, B., Cruz, L. & Gonçalves, N. Deep facial diagnosis: deep transfer learning from face recognition to facial diagnosis. IEEE Access. 8, 123649–123661 (2020).

A Framework for Recognition of Facial Expression. Using HOG features. Int. J. Math. Stat. Comput. Sci. 2, 1–8 (2024).

Face Mask Detection Using Haar Cascades Classifier To Reduce The Risk Of Coved-19. Int. J. Math. Stat. Comput. Sci. 2, 19–27 (2023).

Saeed, V. A. A framework for recognition of facial expression using HOG features. Int. J. Math. Stat. Comp. Sci. 2, 1–8 (2024).

Kareem, O. S. Face mask detection using Haar cascades classifier to reduce the risk of Coved-19. Int. J. Math. Stat. Comp. Sci. 2, 19–27 (2024).

Wang, X. & Zhu, H. Artificial Intelligence in Image-Based Cardiovascular Disease Analysis: A Comprehensive Survey and Future Outlook. arXiv 2402.03394 (2024).

James, P. A. et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the eighth joint National committee (JNC 8). JAMA 311, 507–520 (2014).

Liakos, C. I., Grassos, C. A. & Babalis, D. K. 2013 ESH/ESC guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: what has changed in daily clinical practice? High. Blood Press. Cardiovasc. Prev. 22, 43–53 (2015).

Wang, Y. Clinical Targeted Efficacy Study of Ejiao on Thin Endometrium (Deficiency of Essence and Blood Syndrome). Chengdu University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (2018).

Ibtehaz, N., Rahman, M. S. & MultiResUNet Rethinking the U-Net architecture for multimodal biomedical image segmentation. Neural Netw. 121, 74–87 (2020).

Simonyan, K. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv preprint arXiv:1409.1556 (2014).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. Proc. IEEE Conf. Comput. Vis. Pattern Recognit. (CVPR), 770–778 (2016).

Guan, X., Xu, Y., Yang, S., Guo, Y. & Li, F. Exploration of the relationship between facial diagnostic features in traditional Chinese medicine and diseases. China J. Traditional Chin. Med. Pharm. 37, 902–905 (2022).

Iqbal, N. et al. Determination of blood flow in superficial arteries of human face using doppler ultrasonography in young adults. Int J. Front. Sci. 5 (1), (2021).

Huang, Z. et al. A novel tongue segmentation method based on improved U-Net. Neurocomputing 500, 73–89 (2022).

Evdochim, L. et al. Hypertension detection based on photoplethysmography signal morphology and machine learning techniques. Appl. Sci. 12, 8380 (2022).

Morita, D. et al. Deep-learning-based automatic facial bone segmentation using a two-dimensional U-Net. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 52, 787–792 (2023).

Oiwa, K. & Nozawa, A. Feature extraction of blood pressure from facial skin temperature distribution using deep learning. IEEJ Trans. Electron. Inf. Syst. 139, 759–765 (2019).

Liu, J., Luo, H., Zheng, P. P., Wu, S. J. & Lee, K. Transdermal optical imaging revealed different Spatiotemporal patterns of facial cardiovascular activities. Sci. Rep. 8, 10588 (2018).

Meng, Y. et al. Traditional Chinese medicine constitution identification based on objective facial and tongue features: A Delphi study and a diagnostic nomogram for blood stasis constitution. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 6950529 (2022). (2022).

Yang, Y., Zhang, H., Gichoya, J. W., Katabi, D. & Ghassemi, M. The limits of fair medical imaging AI in real-world generalization. Nat. Med. 30, 2838–2848 (2024).

Guo, L. L. et al. Evaluation of domain generalization and adaptation on improving model robustness to Temporal dataset shift in clinical medicine. Sci. Rep. 12, 2726 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We extend our sincere appreciation to every individual who committed their time and energy to participate in this research.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No.2022YFC3502301. No. 2022YFC3502300), and by the NATCM’s Project of High-level Construction of Key TCM Disciplines at Beijing University of Chinese Medicine (No. zyyzdxk-2023263).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.J. Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Z.M. Data curation, Formal analysis, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft. Z.HY. Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. LM: Data curation, Formal analysis, Software. Z.ML. Data curation, Formal analysis, Software. Z.XQ.Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics statement

The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Dongzhimen Hospital, Beijing University of Chinese Medicine, with approval number: 2023DZMEC-228-03. All procedures followed the appropriate guidelines and regulations outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Prior to participation, written informed consent was obtained from all individuals involved. The research methods employed in the study were conducted in accordance with the applicable guidelines and regulations.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, J., Zhao, M., Zhou, H. et al. Application and accuracy analysis of different facial regions based on deep learning in the diagnosis of hypertension. Sci Rep 16, 1218 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30936-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30936-z