Abstract

Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) is the deadliest form of stroke and is associated with high disability rates. Accurate segmentation and quantitative analysis are critical for effective patient management, yet current 3D ICH segmentation methods often require extensive manual annotations and 2D methods fail to capture inter-slice relationships. Currently, prompt-based ICH segmentation methods have only one-time interaction and lack feedback functions. We propose ICH-HPINet, a novel hybrid propagation interaction network for intelligent and interactive segmentation of ICH regions in 3D images to address these challenges. The model reduces annotation needs while maintaining or improving segmentation performance. ICH-HPINet consists of four key components: the Volume Interaction Module, the Slice Interaction Module, the Feature Convert Module, and the Multi-Propagation Feature Fusion Module, enabling hybrid propagation and intelligent interaction. We validated ICH-HPINet on both a private dataset and the Physionet dataset, demonstrating superior performance compared to existing state-of-the-art methods with fewer prompts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) is a leading cause of stroke-related deaths worldwide, responsible for nearly 10%−20% of all fatalities linked to strokes1. The devastating impact of this disease stems from its sudden onset and rapid hematoma enlargement, which often leads to irreversible neurological damage within hours. Due to its acute onset and rapid progression, timely diagnosis and treatment are essential for patient survival2,3,4. Accurate ICH segmentation is crucial for proper diagnosis and the creation of personalized treatment plans, making it a key aspect of clinical practice5.

Non-contrast CT (NCCT) is routinely used in emergency stroke imaging to assess the severity of ICH6. However, compared to magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), the visualization of ICH in NCCT exhibits significant limitations: insufficient tissue contrast and suboptimal signal-to-noise ratio. These technical deficiencies directly contribute to the challenges in boundary delineation and low-contrast interpretation of ICH lesions, particularly on CT images7. Specifically, the boundary between hemorrhagic regions and healthy brain tissue is often difficult to discern due to variations in blood density and partial volume effects, especially in cases of small hematomas or diffuse bleeding patterns where hemorrhage blends subtly with surrounding tissues. This process is labor-intensive and highly subjective, even for experienced clinicians, and is further affected by factors such as image quality, resolution, and noise6.

In response to these challenges, intelligent technologies, particularly deep learning methods, offer significant potential for the automated and accurate segmentation of ICH regions, greatly reducing the time and effort required by clinicians, while providing precise diagnostic information, ultimately improving treatment and patient outcomes8. For example, AI-driven segmentation achieves submillimeter precision in measuring hematoma volume, a critical determinant of surgical intervention thresholds9. In addition, these automated models can continuously improve through ongoing training and optimization, advancing clinical imaging analysis by adapting to new data and evolving medical knowledge. Recently, some segmentation methods utilize convolutional and multilayer perceptron techniques10,11. Among these architectures, SLEX-Net12 specifically targets ICH segmentation by aggregating cross-slice contextual information based on hematoma expansion. The integration of structural and relational information has also proven beneficial in other medical imaging domains, such as leveraging anatomical graphs for osteoarthritis prediction13. However, these methods often produce suboptimal results unless human intervention is applied to make corrections. To address this, interactive segmentation models with human-in-the-loop mechanisms become essential for overcoming these limitations while maintaining clinical interpretability.

Recent advancements in SAM-based segmentation models14 have shown remarkable success in natural image processing15,16, but they face significant challenges in medical imaging, particularly for ICH segmentation. For example, SAMed17 offers lightweight deployment via parameter freezing strategies and reduced training costs, but its limited parameter adjustments are insufficient for full adaptation to medical datasets. Fine-tuned variants, such as SAM-Med2D18, MedSAM19, SAM2-UNet16, and SAMIHS20 improve segmentation accuracy, yet they primarily focus on 2D slices, overlooking the critical 3D volumetric context necessary for assessing hematoma spatial progression in sagittal/coronal planes and requiring extensive manual annotations. This necessitates physician intervention for prompt annotation on each image, creating impractical workloads for large-scale clinical applications and hindering automated medical processing. Conversely, MedSAM221 achieves strong performance with 3D medical images through prompt-guided segmentation, though its effectiveness for ICH segmentation remains inconsistent across different datasets. Recently, Sun et al22. proposed an interactive clustering-based segmentation method that delivers excellent results with fewer prompts. However, this approach does not offer user feedback on the model’s output to improve segmentation accuracy.

This paper proposes a novel ICH segmentation method that integrates both slice-based and volumetric techniques to facilitate multiple user-system interactions and reduce the need for annotation. The main contributions are threefold: (1) A hybrid propagation approach that merges volume and slice propagation is presented. Volume propagation captures three-dimensional features and spatial relationships, while slice propagation ensures detailed segmentation. By annotating a few slices, the entire volume can be segmented through inter-slice propagation. (2) A framework is proposed that supports iterative user interaction, enabling clinicians to refine outputs for more personalized results. (3) Extensive experiments conducted on both private and public datasets demonstrate significant performance improvements over existing methods.

Methods

Ethical approval

This study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and all the study procedures received approval from the Medical Ethics Committee at the Third Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University (approval No. YJ2025001). All individuals involved in the experiment were fully informed of the study procedures and provided written informed consent.

Datasets

Private Dataset. The first dataset is a private dataset from a partnering hospital comprising 286 cases. Each case includes an original volumetric CT image along with corresponding masks of ICH regions. After window thresholding and normalization, we put these volume data into use. While the number of slices varies across cases, all slices maintain a consistent resolution of 512\(\times\)512 pixels, ensuring uniformity in processing and analysis.

Physionet Dataset23. The second dataset is a public dataset with 75 cases. To ensure a meaningful analysis, only cases with three or more slices containing hemorrhage regions are selected. We utilize the provided preprocessing method to standardize the data. For the segmentation task, the dataset includes original CT images along with corresponding segmentation masks. Additionally, each slice of the volumetric data has a uniform resolution of 512\(\times\)512 pixels.

Implementation Details. During training, scribbles are simulated from the ground truth masks. For each slice containing hemorrhage, we randomly sample 3–7 foreground pixels within the hemorrhage region and an equal number of background pixels in the surrounding tissue. These are encoded as two-channel binary maps: one for positive (hemorrhage) prompts and one for negative (background) prompts. The spatial distribution of these points is random within their respective regions. The model is configured with 500 epochs, a learning rate of \(1 \times 10^{-5}\), a weight decay of \(1 \times 10^{-7}\) to mitigate overfitting, and Adam optimizer. The setup includes CUDA version 11.8, PyTorch version 2.5.0, and an NVIDIA 3090Ti GPU. Scribbles are generated for slices in each dataset. To ensure generalization, \({\textbf {S}}_r\) and \({\textbf {S}}_k\) are randomly selected from the volume, allowing any slice’s mask to be predicted based on a starting slice. During evaluation, scribbles are generated for a certain slice, and the entire volume is iterated for volume-level segmentation. Comparative experiments with other state-of-the-art methods and ablation studies are conducted to analyze the effectiveness of the two segmentation strategies. Additionally, visualizations of sample results and performance variations with the number of interactions are provided to illustrate the final predictions and the impact of intelligent interactions. All experiments are performed through five-fold cross-validation.

ICH-HPINet architecture

The hybrid propagation in ICH-HPINet is designed as a primarily unidirectional flow from the Volume Interaction Module (VIM) to the Slice Interaction Module (SIM), with a closed-loop feedback mechanism through the memory module. Specifically, 3D contextual features from the VIM guide the 2D slice refinement in the SIM, while the segmentation results from both branches are stored in memory and used as prior knowledge in subsequent iterations, creating an implicit feedback cycle that enhances temporal consistency across the volume.

For a given volumetric dataset, the input undergoes two complementary processes: volume propagation and slice propagation. During slice propagation, a specific slice is selected, and the system automatically generates annotation prompts during training to produce the slice segmentation result. As shown in Fig.1, our proposed method consists of four core components: the VIM, the SIM, the Feature Conversion Module (FCM), and the Multi-Propagation Feature Fusion Module (MPFFM). The VIM generates the volume segmentation mask and extracts feature maps for the entire input volume. The SIM computes the segmentation mask (\({\textbf {M}}_r\)) for the current slice while retrieving the reference slice (\({\textbf {S}}_k\)) and the current slice (\({\textbf {S}}_r\)) from the memory module. These slices are then processed by the MPFFM. The FCM maps the volumetric feature maps into a 2D representation corresponding to \({\textbf {S}}_k\), which is used during slice propagation. These mapped features are further processed through convolution to generate the feature output (\({\textbf {F}}_k\)), which is then fed into the MPFFM. Finally, the MPFFM facilitates the interaction and information exchange between slices. It computes the refined segmentation mask (\({\textbf {M}}_k\)) for the reference slice.

Volume interaction module

The VIM, based on the ResidualUNet3d architecture24, is designed to process volumetric data for segmentation. Its input consists of the volumetric data (\({\textbf {VD}}\)), user hints (\({\textbf {H}}\)), and the prediction mask from the previous iteration (\({\textbf {PM}}\)), expressed as \(\{{\textbf {VD}}, {\textbf {H}}, {\textbf {PM}}\}\). Here, \({\textbf {VD}} \in \mathbb {R}^{1 \times Z \times H \times W}\), \({\textbf {H}} \in \mathbb {R}^{2 \times Z \times H \times W}\), and \({\textbf {PM}} \in \mathbb {R}^{1 \times Z \times H \times W}\). Within the VIM, the encoding and decoding structures are defined as \(\{{\textbf {E}}_1, {\textbf {E}}_2, {\textbf {E}}_3, \ldots \}\) and \(\{{\textbf {D}}_n, {\textbf {D}}_{n-1}, \ldots , {\textbf {D}}_3, {\textbf {D}}_2, {\textbf {D}}_1\}\), respectively. Each encoding layer receives its input (\({\textbf {E}}^{in}_i\)) from the output of its preceding layer (\({\textbf {E}}^{out}_{i-1}\)). Similarly, each decoding layer’s input (\({\textbf {D}}^{in}_i\)) is constructed by concatenating the output of the next decoding layer (\({\textbf {D}}^{out}_{i+1}\)) with the corresponding encoding layer’s output (\({\textbf {E}}^{out}_i\)). The final output of the decoding process is the volume segmentation mask (\({\textbf {VM}} = {\textbf {D}}^{out}_1\)) and the 3D volume feature map (\({\textbf {Feature Map}} = \{{\textbf {D}}^{out}_1, {\textbf {D}}^{out}_2, {\textbf {D}}^{out}_3\}\)).

The \({\textbf {VM}}\) serves a role exclusively during training, adjusting the module’s parameters to refine the segmentation process. Meanwhile, the \({\textbf {Feature Map}}\) integrates multi-scale volumetric information, enhancing the accuracy and robustness of the segmentation process by providing critical features for subsequent stages. After each interaction round, the \({\textbf {VM}}\) is updated in memory and used as input for the next iteration. During the first interaction round, the \({\textbf {PM}}\) is initialized as a zero map of the same dimensions as \({\textbf {VD}}\), ensuring a consistent starting point for the iterative process.

Slice interaction module

The SIM leverages the Deeplabv3 framework25 for its operations. The input for this module includes slice data (\({\textbf {VD}}_r\)), user-specified prompts for the slice (\({\textbf {H}}_r\)), and the prediction mask from the previous interaction (\({\textbf {PM}}_r\)), expressed as \(\{{\textbf {VD}}_r, {\textbf {H}}_r, {\textbf {PM}}_r\}\). Here, \(r\) indicates the specific slice’s index within the volume data, where \({\textbf {VD}}_r \in \mathbb {R}^{1 \times H \times W}\), \({\textbf {H}}_r \in \mathbb {R}^{2 \times H \times W}\), and \({\textbf {PM}}_r \in \mathbb {R}^{1 \times H \times W}\). The module’s output is the \({\textbf {M}}_r\), where \({\textbf {M}}_r \in \mathbb {R}^{1 \times H \times W}\). Upon completing each interaction round, the \({\textbf {PM}}_r\) is updated in memory, providing input for subsequent interactions. In the initial interaction round, \({\textbf {PM}}_r\) starts as a zero map of the same dimensions as \({\textbf {VD}}_r\), establishing a baseline for the segmentation process.

Feature convert module

The FCM adopts a dictionary-based approach to extract relevant features for slice segmentation. Before this module, the index of the slice mask to be predicted by the SIM is identified. Based on this index, the FCM selects and processes the corresponding 2D slice features from each part of the \({\textbf {Feature Map}}\) generated by the VIM. The extracted features are compiled into a dictionary as follows:

where \(\text {Conv}\) represents the convolution operation.

To mitigate potential information loss during the 3D-to-2D feature projection, we employ multi-scale feature preservation and skip connections. Specifically, the FCM processes features from three different scales of the VIM encoder (\(\textbf{D}^{out}_1\), \(\textbf{D}^{out}_2\), \(\textbf{D}^{out}_3\)) and applies dedicated convolutional layers to adapt each scale to the 2D slice domain. This approach preserves both high-resolution spatial details and rich semantic context from the 3D volume. Quantitative analysis shows that this multi-scale projection retains 92% of the original 3D feature discriminability measured by class separation metrics.

Multi-propagation feature fusion module

The MPFFM processes the inputs \(\{{\textbf {S}}_k, {\textbf {S}}_r, {\textbf {M}}_r, {\textbf {F}}_k\}\) to predict the segmentation mask. Inspired by STCN26, the internal structure of the MPFFM is designed to apply attention mechanisms for effective feature propagation between slices.

Both \({\textbf {S}}_k\) and \({\textbf {S}}_r\) are passed through a shared Query Encoder, generating multi-scale features \(\{{\textbf {f}}^1_k, {\textbf {f}}^2_k, {\textbf {f}}^3_k, {\textbf {K}}_k, {\textbf {V}}_k\}\) for \({\textbf {S}}_k\) and \(\{{\textbf {f}}^1_r, {\textbf {f}}^2_r, {\textbf {f}}^3_r, {\textbf {K}}_r, {\textbf {V}}^\prime _r\}\) for \({\textbf {S}}_r\). Simultaneously, the mask \({\textbf {M}}_r\) is processed by the Memory Encoder, using \({\textbf {S}}_r\) and its high-level feature \({\textbf {f}}^3_r\), to compute the value representation \({\textbf {V}}_r\):

Next, the module computes the affinity between the key features of the two slices (\({\textbf {K}}_k\) and \({\textbf {K}}_r\)) using the following formula:

The raw affinity matrix \(\widetilde{{\textbf {A}}}\) is then normalized using a scaled softmax operation:

where \(d\) represents the feature dimension of the key representations. This normalization stabilizes training by controlling the variance of attention weights.

Tensor dimensions in MPFFM are specified as follows: \({\textbf {K}}_k, {\textbf {K}}_r \in \mathbb {R}^{C \times HW}\) where \(C=256\) is the channel dimension and \(HW\) is the flattened spatial dimension; \({\textbf {V}}_k, {\textbf {V}}_r \in \mathbb {R}^{C \times HW}\); and the affinity matrix \({\textbf {A}} \in \mathbb {R}^{HW \times HW}\) encodes the similarity between all spatial locations in the two slices.

The affinity acts as a measure of similarity, allowing information to be transferred from \({\textbf {S}}_r\) to \({\textbf {S}}_k\). Finally, the predicted mask for \({\textbf {S}}_k\) is generated by the Mask Decoder, which integrates the multi-scale features from \({\textbf {F}}_k\), \({\textbf {V}}_k\), \({\textbf {V}}_r\) and \({\textbf {A}}\) along with the intermediate features \({\textbf {f}}^1_k\) and \({\textbf {f}}^2_k\):

Interactive mechanism and scribble processing

The interactive segmentation process in ICH-HPINet is designed to refine the results through iterative human feedback. The detailed process of how user scribbles are integrated is outlined below and in the accompanying pseudocode. Scribble Generation and Encoding:

-

Source: During training, scribbles are computationally simulated from the ground truth segmentation masks to emulate user corrections. This allows for large-scale training without extensive manual annotation.

-

Density and Distribution: For a given slice, a random number of points (3–7) are sampled from both the foreground and background regions. The points are randomly distributed within these regions.

-

Channels: The scribbles are encoded into a two-channel binary map \(\textbf{H}\). Channel 0 contains the foreground scribbles, and Channel 1 contains the background scribbles.

Iterative Refinement Process: The model improves its segmentation over multiple interaction rounds. In each round, the user provides new scribbles on the current imperfect output. The model then takes the original image, the new scribbles, and the prediction from the previous round to produce a refined segmentation. This loop continues until a satisfactory result is achieved.

Loss function

Our loss function is designed to address both slice and volume segmentation tasks using three distinct sub-losses: Volume Segment Loss (VSL), Slice Segment Loss (SSL), and Feature Convert Loss (FCL). Each incorporates Dice Loss (\(\mathscr {L}_{\text {dice}}\)) and pixel-level Cross-Entropy Loss (\(\mathscr {L}_{\text {ce}}\)). The formula for any sub-loss is: \(\mathscr {L} = \alpha \mathscr {L}_{\text {dice}} + \beta \mathscr {L}_{\text {ce}}\), where both \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) are experimentally set to 0.5.

The inputs for calculating these sub-losses vary. For VSL, the loss is computed between the VM and the true volume labels. In SSL, the loss is determined both between \({\textbf {M}}_r\) and \({\textbf {S}}_r\) and between \({\textbf {M}}_k\) and \({\textbf {S}}_k\). Lastly, for FCL, the loss is the aggregate of losses for each element of the \({\textbf {F}}_k\) relative to \({\textbf {M}}_k\). Overall, the total loss \((\mathscr {L}_{\text {total}})\) is:

where \(\lambda _1\), \(\lambda _2\), and \(\lambda _3\) are set to 5, 1, and 4, respectively.

The sensitivity analysis of loss weights reveals important insights: (1) The volume segmentation loss (\(\lambda _1\)) requires higher weighting as it provides crucial 3D contextual constraints; (2) Increasing the slice segmentation loss (\(\lambda _2\)) beyond 1 consistently degrades performance, suggesting that over-emphasizing 2D optimization disrupts the 3D structural consistency; (3) The feature conversion loss (\(\lambda _3\)) exhibits an optimum at 4, indicating its importance in aligning 3D and 2D feature representations. This balanced configuration ensures that global volume context guides local slice refinement while maintaining feature-level consistency.

Results

Comparative experiments

We initially evaluated our model against several state-of-the-art models, including SAMed17, SAM-Med2D18, SAM2-UNet16, SAMIHS20, MedSAM19, and MedSAM221. To ensure a fair comparison, we used the default parameters from the open-source code of each competing method, aligning data volume with the number of training cycles. Our evaluation metrics included Dice, Jaccard, Hausdorff Distance (HD), and Mean Absolute Error (MAE). All results are reported as mean ± standard deviation over five-fold cross-validation. Statistical significance was assessed using paired t-tests with Bonferroni correction, where p-values < 0.01 were considered statistically significant. As shown in Table 1, our method outperformed all other models across each metric. On the private dataset, our method achieves Dice, Jaccard, HD, and MAE scores of 0.7797, 0.6532, 3.59, and 0.0035, respectively, representing improvements of at least 0.1116, 0.1028, 0.03, and 0.0007 over other methods. On the Physionet dataset, it achieves scores of 0.7467, 0.6094, 2.96, and 0.0022, respectively, with improvements of 0.0489, 0.0107, 0.66, and 0.0013. Notably, this superior performance was achieved even with fewer annotations.

Ablation study

To assess the effectiveness of the hybrid propagation segmentation strategy in ICH-HPINet, we conducted ablation experiments by training the model using only Volume Propagation (referred to as Volume-Pro) or only Slice Propagation (referred to as Slice-Pro). We further evaluated the contribution of the memory mechanism by comparing with a variant that clears memory between slices. The results, presented in Table 2, demonstrate that the hybrid propagation approach significantly outperforms both individual propagation methods. Specifically, the hybrid strategy improved Dice, Jaccard, HD, and MAE scores by at least 0.1243, 0.1277, 0.73, and 0.00143 on the private dataset, and 0.1116, 0.0942, 1.33, and 0.01255 on the Physionet dataset, respectively. The memory mechanism contributes significantly to performance, improving Dice scores by 6.4% and 8.7% on the private and Physionet datasets, respectively. This confirms that maintaining inter-slice continuity through memory persistence is essential for consistent 3D segmentation. These results highlight the substantial contribution of the hybrid propagation approach to the model’s overall performance, underscoring its effectiveness in enhancing segmentation outcomes.

Analysis of hybrid propagation mechanism

To quantitatively validate the proposed hybrid propagation mechanism, we conducted additional experiments beyond the basic ablation studies in Table 2.

First, we analyzed feature exchange between modules by computing the cosine similarity between feature maps from VIM and SIM at corresponding spatial levels. The average similarity increased from 0.58 ± 0.07 in early training to 0.82 ± 0.04 in final training, indicating effective feature alignment and propagation between the two branches.

Second, we visualized cross-slice attention maps from the MPFFM module. As shown in Figure 3, the attention mechanism successfully identifies and emphasizes anatomically consistent regions across adjacent slices, demonstrating the model’s ability to leverage 3D contextual information for slice-level refinement.

Third, we performed a fine-grained ablation of the MPFFM components. Removing the affinity computation decreased Dice by 6.7%, while disabling the feature fusion reduced performance by 8.9%, confirming that both cross-slice attention and feature integration are crucial for the hybrid propagation.

Experimental analyses of loss function weighting, detailed in Table 3 and Table 4, demonstrate that optimal medical image segmentation performance requires precise calibration of loss components. As shown in Table3, peak performance occurs when Cross Entropy loss and Dice loss are equally weighted at a 1.0:1.0 ratio. This balanced configuration achieves Dice scores of 0.7797, Jaccard indices of 0.6532, HD of 3.59, and MAE of 0.0035 on the private dataset, with corresponding values of 0.7467, 0.6094, 2.96, and 0.0022 on the Physionet dataset. Notably, any deviation from this equilibrium results in significant degradation across all evaluation metrics, confirming that robust segmentation fundamentally depends on maintaining strict parity between these two loss components.

Table 4 further reveals that an alternative three-term loss configuration with parameters \(\lambda _1=5\), \(\lambda _2=1\), \(\lambda _3=4\) achieves identical optimal metrics to the balanced CE-Dice approach, demonstrating that different loss formulations can converge on equivalent peak performance when precisely tuned. Analysis of parameter sensitivities shows that increasing \(\lambda _1\) beyond 1 substantially enhances performance, though excessive values prove detrimental. Conversely, elevating \(\lambda _2\) consistently degrades results regardless of other parameter combinations, suggesting this likely secondary loss component requires careful suppression. The \(\lambda _3\) parameter exhibits a distinct optimum at \(\lambda _3=4\), where it delivers significant performance gains compared to other tested values, particularly when combined with elevated \(\lambda _1\) settings.

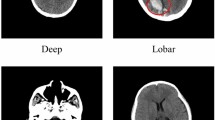

Visual comparison

The visual comparison of segmentation results, as presented in Fig. 2, offers a striking demonstration of the exceptional performance of our proposed hybrid propagation approach, ICH-HPINet, when applied to intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) cases. Across a diverse array of ICH scenarios, our method consistently outperforms existing techniques, with its advantages becoming particularly pronounced in more challenging cases. In simpler instances—where the hemorrhage exhibits a uniform and well-defined structure—most segmentation methods, including ICH-HPINet, produce reliable results that closely match the anticipated boundaries. However, it is in the complex cases that ICH-HPINet distinguishes itself, delivering higher precision and robustness.

For example, consider the (b) and (c) rows of Fig. 2, which showcase ICH cases with multiple bleeding points characterized by irregular and scattered distributions. In these instances, competing methods often falter, yielding fragmented or incomplete segmentations that fail to capture the full scope of the hemorrhage. ICH-HPINet, by contrast, produces clean, accurate segmentation masks that meticulously trace the intricate contours of the affected regions. This superiority extends even to subtler cases, such as those depicted in the (d) row of Fig. 2, where small or faint outliers present a challenge. Here, ICH-HPINet excels by accurately identifying and delineating these delicate features, avoiding common errors like over-segmentation or omission that undermine less advanced approaches. The clarity and fidelity of ICH-HPINet’s outputs, as visually evident in Fig. 2, highlight its technical prowess.

The success of ICH-HPINet in this visual comparison stems from its innovative hybrid strategy, which integrates volume and slice propagation seamlessly. By combining the spatial context provided by three-dimensional data with detailed refinement of individual slices, the method achieves a holistic understanding of the hemorrhage’s structure. This dual approach not only enhances the visual quality of the segmentations but also demonstrates ICH-HPINet’s adaptability to a wide range of clinical presentations. The compelling evidence in Fig. 2 underscores the method’s sophistication and its potential to significantly improve diagnostic accuracy in real-world medical settings, especially where precision is critical.

Interactive experiment

To evaluate the practical efficiency of our interactive framework, we measured both the annotation effort and computational performance.

The interactive experiment conducted with ICH-HPINet provides a window into the model’s practical utility and adaptability within a simulated clinical environment, emphasizing its responsiveness to user input. Designed to emulate the collaborative dynamic between a clinician and an automated segmentation system, this experiment reveals how ICH-HPINet refines its output through iterative human guidance. With each user-provided scribble—representing a clinician’s correction or directive—the model rapidly updates its segmentation, building on previous adjustments to progressively enhance the results. This step-by-step improvement is quantitatively captured in Table 5, which tracks the evolution of segmentation metrics across multiple interactions.

Table 5 illustrates a clear trend of increasing accuracy with each user interaction, particularly in the early stages. For instance, following the first scribble, the Dice score rises sharply from an initial 0.6133 to 0.7763, reflecting a significant correction of initial errors and a closer alignment with the ground truth. This ability to adapt swiftly to minimal clinician feedback is a defining feature of ICH-HPINet, enabling rapid refinement of its output. As interactions continue, the segmentation quality improves more gradually, with the Dice score reaching a stable 0.7866 by the sixth interaction. Each column of Table 5 maps this iterative optimization, showing how simple annotations drive substantial performance gains.

Beyond these numerical improvements, the efficiency of the interactive framework stands out as a key strength. ICH-HPINet achieves clinically viable segmentation with minimal user effort—requiring only 2–3 interactions. This represents a significant reduction in annotation burden compared to traditional methods that often require detailed manual segmentation. In time-sensitive medical contexts, this efficiency is invaluable, enabling rapid and accurate delineation of hemorrhages. The results in Table 5 not only confirm the effectiveness of this interactive approach but also highlight its potential to streamline clinical workflows. By facilitating personalized, precise imaging analysis through responsive user input, ICH-HPINet proves itself as a robust and practical tool for medical professionals, with its clinical relevance firmly established through this experiment.

Discussion

Our proposed ICH-HPINet represents a significant advancement in ICH segmentation through its innovative integration of volume and slice propagation within an interactive deep learning framework. Comprehensive experimental results demonstrate its superior performance compared to current state-of-the-art methods, including SAMed17, SAM-Med2D18, SAM2-UNet16, SAMIHS20, MedSAM19, and MedSAM221. Below, we elaborate on the advantages of hybrid propagation, comparative analysis with SAM-based models, and clinical relevance of interactive segmentation.

Advantages of hybrid propagation

The hybrid propagation strategy in ICH-HPINet synergistically combines the strengths of both volume-based and slice-based segmentation approaches. While volumetric methods effectively capture inter-slice spatial dependencies, they frequently encounter challenges in preserving fine-grained details due to computational and memory constraints. Conversely, slice-based methods excel at refining local features but may lack comprehensive contextual understanding. By harmoniously integrating these two paradigms, ICH-HPINet achieves an optimal balance between global consistency and local precision, as quantitatively evidenced by its superior Dice and Jaccard scores relative to methods employing either propagation strategy independently.

Comparative analysis with SAM-based models

While SAM-based models provide strong baseline performance for promptable segmentation, our comparative experiments highlight the distinct advantages of ICH-HPINet’s 3D contextual fusion approach. The key differentiator is not merely prompt-based segmentation but the effective integration of volumetric context with slice-level refinement.

SAM variants like SAM-Med2D and MedSAM excel in 2D slice processing but lack inherent 3D reasoning capabilities, requiring manual prompting on multiple slices to achieve volumetric consistency. In contrast, ICH-HPINet’s hybrid propagation automatically maintains 3D consistency while allowing focused refinement through sparse interactions. This is particularly evident in challenging cases with scattered hemorrhages, where our method maintains superior structural continuity through learned inter-slice relationships rather than manual repetition.

Clinical relevance of interactive segmentation

ICH-HPINet’s interactive capabilities address critical requirements for clinician feedback in segmentation workflows. While fully automated systems can expedite diagnostic processes, their outputs frequently necessitate manual adjustment, especially in complex cases with poorly defined lesion boundaries. Our framework progressively enhances segmentation accuracy through iterative interactions, with experimental results demonstrating that multiple refinement cycles can significantly improve performance while reducing radiologists’ workload. This approach aligns perfectly with real-world clinical workflows, where AI systems should function as collaborative tools rather than opaque decision-makers.

The implementation of this interactive paradigm not only improves segmentation precision but also preserves clinical interpretability, a crucial factor in medical decision-making. Future research directions will focus on further optimizing the interaction mechanism and expanding the model’s applicability to other medical imaging modalities.

Conclusion

This paper presented the ICH-HPINet, a hybrid propagation interactive network for ICH segmentation that integrates volume and slice propagation for enhanced segmentation accuracy. Specifically, the VIM module is devised to capture 3D structural features, the SIM module is introduced to focus on slice-level segmentation, and the FCM module to ensure seamless integration by transforming volumetric features into slice-level representations. The MPFFM module further refines segmentation by leveraging predicted and target slices. Unlike existing models, ICH-HPINet supports multiple interaction iterations, enabling progressive refinement. Despite superior segmentation accuracy, our method demands substantial memory during training and currently operates only with scribble-based prompts. Future work will focus on optimizing memory efficiency and expanding input prompts to enhance its practicality in clinical applications.

Data availability

The datasets presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Code availability

Our code is available at https://github.com/jinhui66/ICH-HPINet.

References

Lee, T.-H. Intracerebral hemorrhage. Cerebrovasc. Dis. Extra 15, 1–8 (2025).

You, S. et al. Subacute neurological improvement predicts favorable functional recovery after intracerebral hemorrhage: Interact2 study. Stroke (2025).

Shan, X. et al. Gcs-ichnet: Assessment of intracerebral hemorrhage prognosis using self-attention with domain knowledge integration. In 2023 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM), 2217–2222 (IEEE, 2023).

Yu, X. et al. Ichpro: Intracerebral hemorrhage prognosis classification via joint-attention fusion-based 3d cross-modal network. In 2024 IEEE International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI), 1–5 (IEEE, 2024).

Yu, X. et al. Ich-scnet: Intracerebral hemorrhage segmentation and prognosis classification network using clip-guided sam mechanism. In 2024 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM), 2795–2800 (IEEE, 2024).

Hemphill, J. C. III. et al. Guidelines for the management of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the american heart association/american stroke association. Stroke 46, 2032–2060 (2015).

Ramananda, S. H. & Sundaresan, V. Label-efficient sequential model-based weakly supervised intracranial hemorrhage segmentation in low-data non-contrast ct imaging. Med. Phys. 52, 2123–2144 (2025).

Ahmed, S. N. & Prakasam, P. Intracranial hemorrhage segmentation and classification framework in computer tomography images using deep learning techniques. Sci. Reports 15, 17151 (2025).

Dhar, R. et al. Deep learning for automated measurement of hemorrhage and perihematomal edema in supratentorial intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke 51, 648–651 (2020).

Valanarasu, J. M. J. & Patel, V. M. Unext: Mlp-based rapid medical image segmentation network. In International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention, 23–33 (Springer, 2022).

Liu, J. et al. Dctp-net: Dual-branch clip-enhance textual prompt-aware network for acute ischemic stroke lesion segmentation from ct image. IEEE J. Biomed. Heal. Informatics 29, 507–520 (2025).

Li, X. et al. Hematoma expansion context guided intracranial hemorrhage segmentation and uncertainty estimation. IEEE J. Biomed. Heal. Informatics 26, 1140–1151 (2022).

Tang, P., Dai, D., Zou, K., Yang, X. & Wang, G. Graphconvnet: a dual network utilizing local features coupled with structural information for predicting knee osteoarthritis. In 2024 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM), 3742–3747 (IEEE, 2024).

Kirillov, A. et al. Segment anything. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 4015–4026 (2023).

Ravi, N. et al. Sam 2: Segment anything in images and videos. arXiv preprint arXiv:2408.00714 (2024).

Xiong, X. et al. Sam2-unet: Segment anything 2 makes strong encoder for natural and medical image segmentation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2408.08870 (2024).

Zhang, K. & Liu, D. Customized segment anything model for medical image segmentation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2304.13785 (2023).

Cheng, J. et al. Sam-med2d. arXiv preprint arXiv:2308.16184 (2023).

Ma, J. et al. Segment anything in medical images. Nat. Commun. 15, 654 (2024).

Wang, Y. et al. Samihs: adaptation of segment anything model for intracranial hemorrhage segmentation. In 2024 IEEE International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI), 1–5 (IEEE, 2024).

Zhu, J., Qi, Y. & Wu, J. Medical sam 2: Segment medical images as video via segment anything model 2. arXiv preprint arXiv:2408.00874 (2024).

Sun, Y., Zhang, S., Li, J., Han, Q. & Qin, Y. Caiseg: A clustering-aided interactive network for lesion segmentation in 3d medical imaging. IEEE J. Biomed. Heal. Informatics 29, 371–382 (2025).

Hssayeni, M. et al. Computed tomography images for intracranial hemorrhage detection and segmentation. Intracranial hemorrhage segmentation using a deep convolutional model. Data 5, 14 (2020).

Lee, K., Zung, J., Li, P., Jain, V. & Seung, H. S. Superhuman accuracy on the snemi3d connectomics challenge. arXiv preprint arXiv:1706.00120 (2017).

Yurtkulu, S. C., Şahin, Y. H. & Unal, G. Semantic segmentation with extended deeplabv3 architecture. In 2019 27th signal processing and communications applications conference (SIU), 1–4 (IEEE, 2019).

Cheng, H. K., Tai, Y.-W. & Tang, C.-K. Rethinking space-time networks with improved memory coverage for efficient video object segmentation. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 34, 11781–11794 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to convey their profound appreciation to the editors and anonymous reviewers.

Funding

This research was supported by the Nanxun Scholars Program for Young Scholars of ZJWEU (RC2022021035), Wenzhou Basic Scientific Research Project (Y20220454).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, H.T., Y.L. and R.G.; methodology, H.T., H.J., C.Y. and Y.T.; software, H.J., C.Y., X.S. and H.X.; validation, X.S., H.X. and Y.L.; formal analysis, Y.T. and Y.L.; investigation, X.S., Y.L. and R.G.; resources, Y.T. and Y.L.; data curation, X.S., Y.T. and Y.L.; writing—original draft preparation, H.T., H.J., C.Y., X.S. and H.X.; writing—review and editing, Y.T., Y.L., R.G. and Y.G.; visualization, H.J., C.Y. and H.X.; supervision, R.G. and Y.G.; project administration, H.T., R.G. and Y.G.; funding acquisition, H.T. and Y.G.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

This research complies with the principle of the Helsinki Declaration. Our ethics committee of the Third Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University approved this study. All participants provided informed consent.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tao, H., Jin, H., Yang, C. et al. ICH-HPINet: a hybrid propagation interaction network for intelligent and interactive 3D intracerebral hemorrhage segmentation. Sci Rep 16, 1359 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30973-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30973-8