Abstract

This study investigated the effects of cognitively engaging running on inhibitory control and prefrontal brain activation in children with ADHD, and whether physical self-efficacy moderates these effects. Thirty-six children with ADHD participated in three randomized sessions: cognitively engaging running, traditional running, and sedentary activity. Each exercise lasted 30 min at moderate intensity. Inhibitory control was assessed using the Go/No-Go task, and prefrontal activation was measured via functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) before and after each intervention. Results showed that both running types improved reaction time, but only cognitively engaging running significantly enhanced No-Go accuracy and increased oxygenated hemoglobin levels in the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. Moreover, improvements in inhibitory control were positively correlated with changes in prefrontal activation. Notably, physical self-efficacy moderated the cognitive outcomes of exercise; children with higher self-efficacy showed greater improvements following cognitively engaging running, while those with lower self-efficacy did not. These findings suggest that integrating cognitive challenges into physical activity and considering individual psychological traits can optimize executive function interventions for children with ADHD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is one of the most common neurodevelopmental disorders among children. Its core features include attention deficits, hyperactivity, and impulsivity. However, recent studies indicate that ADHD is not limited to these core symptoms; it also involves extensive executive function deficits, particularly in inhibitory control1. Research shows that children with ADHD exhibit significantly higher error rates and longer or shorter reaction times in tasks requiring inhibition of impulsive responses compared to typically developing children. These deficits in inhibitory control are a major reason why children with ADHD display hyperactive and impulsive behaviors2,3.

Evidence suggests that aerobic exercise can enhance inhibitory control abilities in both typically developing children4,5 and children with ADHD6,7. Improvements in reaction time and accuracy in tasks such as the Stroop task and the Flanker task have been observed with children who have lower inhibitory control abilities.

In their review, Tan et al. summarized that the effects of exercise interventions on cognitive tasks in children with ADHD may be influenced by exercise intensity, duration, and type8. Studies have shown that exercises involving more cognitive engagement have a greater impact on children’s cognitive functions compared to repetitive exercises with low cognitive load9,10,11. This is because cognitively engaging exercises require more comprehensive motor skills, varied movement skills, and diverse exercise contexts12, demanding more attentional resources and cognitive effort13. Running is the most common exercise that children engage in. Current research on running and ADHD is limited to repetitive treadmill running in laboratory settings14,15. It is worth exploring whether incorporating cognitive components into running in real-world settings can have additional effects on improving inhibitory control in children with ADHD.

Recent work by Chueh et al. provides a theoretical basis for this approach, demonstrating that acute exercise with higher cognitive load can produce greater improvements in executive function—particularly inhibitory control—than exercise with lower cognitive load16. Drawing on the cognitive-energetic and neurotrophic perspectives, simultaneous motor and cognitive demands are thought to elicit greater prefrontal activation, optimize attentional resource allocation, and promote synaptic plasticity, thereby producing enhanced cognitive benefits. The cognitive-energetic view emphasizes the role of arousal and effort in executive performance17, while the neurotrophic view highlights exercise-induced increases in brain-derived neurotrophic factor that support neural growth18. Although most evidence comes from young adults, these mechanisms may be particularly relevant for children with ADHD, who often show deficits in attentional control and neural efficiency.

With technological advancements, the mechanisms by which exercise impacts executive functions are continuously being explored. Functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) can detect hemodynamic responses in the cerebral cortex19. It indirectly assesses neuronal activity by measuring changes in oxyhemoglobin (oxy-Hb) and deoxyhemoglobin (deoxy-Hb) within tissues20. ADHD children’s cerebral blood flow and neural network activation efficiency differ from typically developing children21, and exercise interventions can help improve hemodynamic responses and oxyhemoglobin concentrations in the prefrontal cortex during cognitive tasks22. In this study, fNIRS measurement was limited to the frontal region, particularly the prefrontal cortex, because of its well-established role in inhibitory control and other core executive functions, which are often impaired in ADHD. The prefrontal cortex is also a primary site where exercise-induced neural activation has been observed, making it a critical target for understanding how cognitively engaging exercise influences brain function in this population6. However, there is a lack of research data on changes in brain activity measured by near-infrared spectroscopy following different cognitively engaging exercise interventions. Understanding how neuronal activity may be modified after different exercise types is meaningful for children with ADHD, as it can help predict which exercise is most beneficial for brain activation before engaging in academic tasks.

The impact of exercise on cognitive function is also shaped by psychological factors, notably physical self-efficacy. Physical self-efficacy refers to an individual’s perception and evaluation of their physical capabilities, reflecting confidence in successfully performing physical tasks23. Variations in physical self-efficacy may lead children to engage with the same activity at different levels of motivation and effort, potentially resulting in different degrees of physiological arousal. Arousal, in turn, directly affects cognitive performance suggesting that physical self-efficacy may moderate the effects of exercise on executive functions21, thus physical self-efficacy may be a moderating factor in the impact of exercise on children’s executive functions. For individuals with ADHD, Newark et al. found that they have lower levels of self-esteem and self-efficacy compared to control groups22. Exercise enhances positive mood and self-efficacy in children with ADHD24. Self-efficacy is a core variable in successful training for children with ADHD, and a valid training should ensure maximal self-efficacy in the participants25,26.

Despite growing interest in exercise-cognition research, there remains a lack of studies directly comparing high- and low-cognitive-load exercise in children with ADHD, especially those combining neuroimaging techniques with psychological moderators such as physical self-efficacy. This study aimed to: (1) investigate the single-session effects of different cognitively engaging running activities on inhibitory control in children with ADHD using fNIRS; (2) examine whether physical self-efficacy moderates the relationship between exercise type and inhibitory control improvements.

By integrating behavioral, neural, and psychological measures, this study seeks to clarify both the mechanisms and boundary conditions under which acute exercise enhances executive function in ADHD.We hypothesized that cognitively engaging running with higher cognitive load would elicit greater improvements in inhibitory control than running with lower cognitive load, consistent with the cognitive-energetic and neurotrophic frameworks supported by Chueh et al. (2023), and that these effects would be more pronounced in children with higher physical self-efficacy.

Methods

Participants

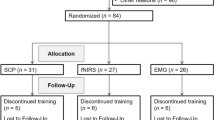

36 right-handed children with ADHD (28 male, M = 9.65 ± 0.80 years) we recruited from local clinics and schools. The participants were drug-naive and did not receive any behavioral intervention for ADHD. Informing them about study protocol details, and obtaining written informed consent from their parents.The demographic and clinical characteristics of the participants are summarized in Table 1.

The diagnosis of ADHD was confirmed by an experienced psychiatrist using the ADHD Rating Scale (ADHD-RS) and the Conners ’Rating Scales for Children (parent-report version). Twenty participants were diagnosed with the combined subtype, seven with the inattentive subtype, and nine with the hyperactive-impulsive subtype.

The study was approved by the ethical committee of China Institute of Sport Science(20212203) and conforms to the Declaration of Helsinki. This trial was registered with Beijing Children Hospital (2024-Y-259D) on 21/10/2024.

Experimental procedure

Each participant took part in three experimental sessions in random order. Each session was separated by at least one week to avoid carry-over effects. Each session consisted of the following procedures (Fig. 1): 5 min inhibitory control assessment (Go-nogo), collecting fNIRS data simultaneously, and a 30 min exercise intervention (high or low cognitive engagement exercises) or control intervention(sit) followed by repetition of inhibitory control and cortical hemodynamic responses assessments. Questionnaires of physical self-efficiency was conducted after each exercise intervention. All experiments were conducted from 8 am to 10am. The entire experimental process used a portable heart rate recorder to monitor children’s heart rate. Children are required not to engage in high-intensity physical activities within 24 h before the experiment.

Exercise protocol

This study incorporated two types of exercise interventions. The first was cognitively engaging running, in which cognitive tasks and coordination exercises were embedded into the running activity to simultaneously activate motor and cognitive neural networks. These included adjusting running speed or direction based on instructor cues, navigating obstacles, catching and throwing a ball while running, and answering cognitive questions during the activity. The exercise intensity was set at a moderate level (60–70% of maximum heart rate), with a total duration of 30 min. The second intervention was traditional running, conducted on a treadmill without any additional cognitive tasks. To ensure comparability, the exercise intensity (60–70% of maximum heart rate) and duration (30 min) were matched to those of the cognitively engaging running condition.

Measurement of inhibitory control

The Go/No-Go task is a classic neuropsychological task widely used in clinical settings to assess response inhibition27. In this study, the Go/No-Go cognitive task design includes 6 block sets, each consisting of one “go” block and one “go/no-go” block (Fig. 2). Each block contains 24 trials, lasting for a duration of 24 s. At the beginning of each task, participants receive a 3-second instruction period28.

During the “go” block, participants are required to quickly press a button when they see images of “cats” and “dogs.” During the “go/no-go” block, participants must press a button when an image of a “chicken” appears but must refrain from responding when an image of a “duck” appears. Each trial is presented in a random order, with an equal number of images of both animals. Participants’ performance is recorded in terms of reaction time for “go” trials and accuracy for both “go” and “no-go” trials. To minimize potential practice effects, all participants completed at least one practice session before the formal test.

Measurement of physical self-efficacy

Physical self-efficacy was assessed using a child-adapted Chinese version of the Physical Self-Efficacy Scale (PSES)23. Consistent with the original structure, the instrument comprises two subscales—Perceived Physical Ability and Physical Self-Presentation Confidence29. We followed a forward–back translation procedure, simplified wording for primary-school readability by a panel of three pediatric exercise psychologists30. The complete adapted item set, scoring scheme (including reverse-coded items), and item-level adaptation rationale are provided in Supplementary Appendix A. In the present sample, internal consistency was acceptable (overall Cronbach’s ɑ= 0.83).

Functional NIRS

A multi-channel functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) device (NirSmart, DanYang Huichuang Medical Equipment Co., Ltd.) was used to collect data on changes in the concentration of oxygenated hemoglobin (Oxy-Hb), deoxygenated hemoglobin (Deoxy-Hb), and total hemoglobin (Total-Hb) while children performed the Go/No-Go task. The system operates with two wavelengths (760 nm and 850 nm) and has a sampling rate of 11 Hz. A total of 15 sources and 16 detectors were used to form 48 channels, covering the prefrontal cortex (PFC). These 48 channels were assigned to six specific regions of interest (ROIs) associated with attentional cognitive tasks (Fig. 3).

fNIRS data were preprocessed using NirSpark V1.5.20. Motion artifacts and environmental noise were corrected with a threshold standard deviation of 6.0 and amplitude of 0.5. A low-pass filter with a frequency of 0.2 Hz was used to correct physiological and environmental noise, and a high-pass filter with a frequency of 0.01 Hz was employed to remove baseline drift. The modified Beer–Lambert law31 was applied to calculate relative concentration changes of Oxy-Hb, Deoxy-Hb, and Total-Hb.

During data collection, head movement can easily introduce motion artifacts in pediatric participants. To minimize this, real-time feedback from the device was monitored, and children were reminded to maintain a stable head position when necessary. For quality control, several criteria were applied during preprocessing: (1) channels with a signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) lower than 2.0 were excluded; (2) channels showing a coefficient of variation > 50% of the baseline period were considered unstable and removed; (3) segments with motion artifacts exceeding ± 6 standard deviations from the mean optical density were corrected using a wavelet-based filter; and (4) participants were included only if at least 80% of channels remained valid after preprocessing. All 36 ADHD participants met these criteria, and thus no dataset was excluded from subsequent analyses.

In this study, the Oxy-Hb signal was selected for further statistical analysis due to its higher sensitivity to cerebral blood flow changes, as well as better signal-to-noise ratio and test-retest reliability32. The average concentration of Oxy-Hb for each channel was determined by calculating the difference between the target period (4–24 s after the start of the “go/no-go” block) and the baseline period (14–24 s after the start of the “go” block)33.

Statistical analysis

Data for HR and inhibitor control measurements in different conditions were described in mean and standard deviation. A multifactor repeated measures ANOVA was conducted to examine the effects of different types of running on executive function in children with ADHD. Pearson correlation analysis was used to assess the relationship between children’s physical self-efficacy and changes in executive function before and after the exercise intervention. The moderating effect of self-efficacy on the outcomes of different types of running interventions was analyzed using linear mixed models. A significance level of ɑ = 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Changes in inhibitory control function

In the ADHD group, No-Go accuracy improved and reaction time decreased following both running interventions, while Go accuracy showed a slight decline. In the control group, the improvement in No-Go accuracy was greater than that observed in the ADHD group, with the cognitively engaging running showing more pronounced effects (see Table 2).

A mixed-design ANOVA was conducted to examine the effects of time (pre- vs. post-intervention) and exercise type (cognitively engaging running vs. traditional running) on No-Go accuracy and reaction time. The results are shown in Table 3.

For No-Go accuracy, there was a significant main effect of time, F(1,34) = 5.42, p = 0.026, partial η2 = 0.137, indicating that accuracy improved from pre- to post-test across both exercise types. The main effect of exercise type was not significant, F(1,34) = 1.18, p = 0.285, partial η2 = 0.034.There was a significant time × exercise type interaction, F(1,34) = 4.85, p = 0.035, partial η2 = 0.125, indicating that the improvement from pre- to post-test was greater for cognitively engaging running compared with traditional running. Post-hoc comparisons showed that No-Go accuracy significantly increased after cognitively engaging running (t(17) = 3.02, p = 0.007, Cohen’s d = 0.71) and after traditional running (t(17) = 2.14, p = 0.046, Cohen’s d = 0.50).

For reaction time, the main effect of time was also significant, F(1,34) = 6.21, p = 0.018, partial η2 = 0.154, showing faster responses after the intervention in both exercise conditions. No significant main effect of exercise type, F(1,34) = 0.84, p = 0.366, partial η2 = 0.024, and no significant interaction, F(1,34) = 1.07, p = 0.309, partial η2 = 0.030, were observed.

The effects of running interventions on children’s brain function

Figure 4 shows the changes in Oxy-Hb concentrations in each channel of the prefrontal cortex during the Go/No-Go task before and after different interventions. Multiple comparisons between groups at different time points revealed that, at pre-test, there were no significant differences in Oxy-Hb signals in the frontal pole and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex channels among the three groups (P > 0.05). At post-test, the Oxy-Hb concentrations in the frontal pole and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex channels were higher in the cognitively engaging running group compared to the control group (t = 2.33, P < 0.05, Cohen’s d = 0.69), and the Oxy-Hb concentrations in channels 14 and 17 were higher than those in the traditional running group.

Changes in Oxy-Hb concentration in prefrontal cortex before and after different intervention conditions (mmol/L mm). The color of the right bar represents the degree of activation, and the redder the color, the stronger the activation; The bluer the color, the weaker the activation. Post-intervention, the cognitively engaging running group (n = 36) showed increased Post-intervention, the cognitively engaging running group exhibited higher Oxy-Hb concentrations in the frontal pole and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (0.42 ± 0.13 µmol/L in channel 14 and 0.38 ± 0.11 µmol/L in channel 27 compared to the control condition (0.26 ± 0.10 and 0.24 ± 0.09 µmol/L, respectively) and the traditional running group (n = 36;0 .29 ± 0.11 and 0.27 ± 0.10 µmol/L; t = 2.33, p < 0.05, Cohen’s d = 0.69). No significant group differences were found in baseline Oxy-Hb levels (p > 0.05).

Pearson correlation and linear regression analyses were conducted between the change in center-of-activation values of the dorsolateral and medial prefrontal cortex (pre- to post-test) and the change in reaction time on Go trials (pre- to post-test). Data from the two intervention groups were pooled for analysis, as the association patterns were consistent across groups.The results revealed a significant positive correlation (R2 = 0.256), as shown in Fig. 5.

Physical self-efficacy and inhibitory control improvement

The Table 4 indicates that in the ADHD group, males (n = 28) had slightly higher scores in Perceived Physical Ability (PPA) compared to females (n = 8), while females scored slightly higher in Physical Self-Presentation Confidence (PSPC) than males. However, the overall Physical Self-Efficacy (PSE) scores were nearly identical between the two groups, with males scoring 72.06 ± 8.50 and females scoring 72.03 ± 8.65.

After controlling for age and gender, the change in inhibitory control (pre-post test) following cognitively engaging running was found to be correlated with physical self-efficacy for ADHD (r = 036, P < 0.05). Meanwhile, the correlation coefficient for traditional running was 0.11 (P > 0.05). The results are shown in Fig. 6.

To examine the moderating effect of self-efficacy on the relationship between exercise and executive function, a mix line regression analysis was conducted. First, the independent variable (exercise) and the moderating variable (self-efficacy) were entered into the regression model separately, followed by the interaction term (exercise × self-efficacy). Table 5 shows the results of the regression analysis. The initial model included only the independent and moderating variables, and the results indicated that exercise (β = 0.40, p < 0.01) and self-efficacy (β = 0.25, p < 0.05) had significant main effects on inhibitory control. When the interaction term was added, the results showed that the interaction effect of exercise × self-efficacy was significant ((β = 0.35, p < 0.01), indicating that self-efficacy significantly moderated the relationship between exercise and inhibitory control.

To further clarify the moderating effect of physical self-efficacy (PSE), children were divided into high- and low-PSE groups using a cutoff of mean ± one standard deviation (72.05 ± 8.51). The Shapiro–Wilk test indicated that the PSE scores were normally distributed (W = 0.981, p = 0.465). The high-PSE group comprised 7 children (80.56 ± 8.49), and the low-PSE group comprised 8 children (63.54 ± 8.31).

Linear mixed models (LMMs) were applied to examine the interaction between intervention type and PSE group, with degrees of freedom estimated using the Satterthwaite method. To address concerns related to small group sizes, we report effect sizes and 95% confidence intervals alongside model estimates. For children with high levels of PSE, cognitively engaging running led to a significantly greater improvement in executive function compared with traditional running (β = 0.42, 95% CI [0.11, 0.73], p = 0.012, Cohen’s d = 0.85). In contrast, for children with low levels of PSE, the difference between the two interventions was small and non-significant (β = 0.08, 95% CI [− 0.19, 0.35], p = 0.51, Cohen’s d = 0.21), as shown in Fig. 7.

Changes in response time of different levels of physical self-efficacy after two types of running. Cognitively engaging running led to greater improvements in inhibitory control for children with high self-efficacy, whereas no significant difference was observed between running types in children with low self-efficacy.

Discussion

This study examined the acute effects of different cognitively engaging running interventions on inhibitory control in children with ADHD, integrating behavioral performance, neural activation, and psychological factors. The main findings were as follows: (1) both traditional running and cognitively engaging running improved reaction times in the Go–Nogo task; (2) cognitively engaging running led to greater improvements in inhibitory control accuracy compared to traditional running; (3) fNIRS results showed that cognitively engaging running induced higher Oxy-Hb concentrations in the frontal pole and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex; and (4) physical self-efficacy significantly moderated the relationship between exercise type and improvements in inhibitory control, with stronger effects observed in children with higher physical self-efficacy.

This study focused on children with ADHD and investigated the effects of different cognitively engaging running interventions on children’s inhibitory control. The results showed that both traditional running and cognitively engaging running had significant positive effects on improving reaction times in the Go-nogo task. Some studies have indicated that acute aerobic exercise promotes processing speed in children’s cognitive tasks34,35. The running exercise increases peripheral and central blood circulation, which facilitates the increase in cerebral blood flow and enhances regional activity levels36. Additionally, research indicates that moderate-duration aerobic exercise (30 min or more) significantly increases the secretion of neurotransmitters such as dopamine and norepinephrine, optimizing mood and cognitive functions37. The physiological changes experienced during acute exercise improve children’s attention allocation, thereby enhancing cognitive processing speed38.

Compared to traditional running, cognitively engaging running showed better performance in improving inhibitory control accuracy. These results are consistent with several studies that have found cognitively engaging physical activities to have greater benefits for executive functions in children39,40. As highlighted by Chueh (2023), higher cognitive load in exercise can promote greater cognitive gains because such activities require simultaneous motor control, attentional regulation, and decision-making, thereby engaging overlapping neural networks with executive function tasks. In this study, cognitively engaging running involved cognitive elements such as the inhibition process, requiring children to execute running or non-running strategies based on the instructions. Therefore, the cognitive elements involved in running are similar to those required in subsequent cognitive tasks. Cognitively engaging running activates neural circuits related to inhibitory control, increasing activation levels in the prefrontal cortex, which is necessary for completing inhibitory control tasks. This leads to improved cognitive abilities in children. In cognitive psychology, previously acquired knowledge and skills can transfer from one cognitive context to another41. The theory of learning transfer has been applied in physical education academic interventions, where exercise is combined with specific learning contexts, resulting in improved cognitive abilities and academic performance in children42,43. In this study, by incorporating cognitive components while maintaining the same exercise modality as the traditional running, the inhibitory control ability of children was better promoted. This suggests that constantly challenging relevant cognitive abilities in varied ways during exercise is a crucial factor in enhancing children’s cognitive performance.

Our fNIRS results further clarify these behavioral effects providing neural evidence for the benefits of cognitively engaging running. The changes in Oxy-Hb concentrations in the frontal pole and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex provide further insights into the neural mechanisms underlying the effects of exercise on inhibitory control. Our results show that cognitively engaging running significantly increased Oxy-Hb concentrations in these regions compared to traditional running and the control group. These findings are consistent with previous studies indicating that exercise can enhance prefrontal cortex function, which is crucial for executive control44. Suwabe et al. also found in their study on adults that increased activation of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) following a single session of acute aerobic exercise was associated with enhanced positive emotions and shorter reaction times45. Since the DLPFC is a central node in the prefrontal emotion regulation network46 and is also responsible for inhibitory control functions47, there is a link between exercise-induced emotional and cognitive responses. This aligns with the idea that emotional and motivational factors—enhanced by engaging, competence-building activities—can amplify the cognitive benefits of exercise48. Therefore, cognitively engaging running may enhance children’s inhibitory control functions by activating prefrontal sub-regions associated with emotional regulation, thereby also increasing arousal levels.

Moreover, the significant correlation between the change in Oxy-Hb concentrations and the change in reaction time (r = 0.26, P < 0.01) suggests that increased cerebral oxygenation and blood flow are associated with faster cognitive processing and improved inhibitory control. This relationship highlights the potential of using near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) as a non-invasive method to monitor brain function changes in response to different types of exercise interventions16.

Not every child with ADHD experiences improved inhibitory control after engaging in cognitively engaging running or traditional running. Our study shows that 35% of the children did not show any improvement in their post-exercise assessment scores. This variation underscores the moderating role of physical self-efficacy.

An important contribution of this study lies in the identification of physical self-efficacy as a moderator of the exercise–cognition relationship. Self-efficacy emerged as a significant moderator in the relationship between exercise and improvements in inhibitory control. Children with high levels of physical self-efficacy showed greater improvements in inhibitory control following cognitively engaging running compared to traditional running. This suggests that the belief in one’s ability to successfully perform physical tasks enhances the benefits of cognitively engaging exercise on executive function49. The significant interaction effect observed in our regression analysis (β = 0.35, p < 0.01) highlights the importance of individual psychological factors in moderating the effectiveness of exercise interventions. Consistent with Bandura’s social cognitive theory and previous research emphasizing motivational and emotional pathways50,51, children with high self-efficacy may be more positive and engaged during exercise. Qualitative observations during the intervention support this interpretation: children with high self-efficacy often displayed confidence in their agility and speed, eagerly attempting cognitively challenging movement tasks, which led to repeated successes and a positive feedback loop between confidence and performance. In contrast, children with low self-efficacy sometimes hesitated or avoided complex tasks, limiting physical engagement and potentially reducing prefrontal activation, thereby constraining the cognitive benefits of exercise22. These patterns underscore that the cognitive effects of exercise are not solely determined by the task design, but also by the child’s perceived competence and willingness to engage fully.

Physical self-efficacy in this study reflects a child’s confidence in their ability to perform physical tasks successfully, which can influence motivation, persistence, and willingness to engage in challenging, cognitively demanding activities52.The practical implication is that intervention design should match the child’s psychological readiness. For children with low self-efficacy, beginning with simpler, success-oriented activities and gradually increasing cognitive load can prevent frustration and optimize learning. For those with high self-efficacy, complex, cognitively engaging exercises can be introduced earlier to maximize cognitive gains. This tailoring approach could improve both adherence and effectiveness in real-world ADHD interventions.

Importantly, this study addresses a key research gap: while prior work has examined exercise effects in ADHD, few studies have directly compared high vs. low cognitive load activities within the same exercise modality, and even fewer have explored psychological moderators such as physical self-efficacy. Our intervention design—maintaining the same physical modality but systematically varying cognitive load—offers a controlled approach to isolate the cognitive engagement effect, which is a methodological strength of this study.

Although this study yielded significant findings, several limitations should be noted. First, the relatively small sample size may limit generalizability. Second, the short-term design cannot capture long-term cognitive or neural changes. Third, limited fNIRS channel coverage reduced spatial resolution. Future studies should address these issues to further validate and extend our findings.Fourth, physical self-efficacy was assessed only after the intervention, and the absence of baseline data limited our ability to examine within-subject changes over time; therefore, including pre-test self-efficacy assessments in future studies would provide a more complete evaluation.

Conclusion

This study provides evidence that cognitively engaging running yields greater improvements in inhibitory control and prefrontal cortex activation in children with ADHD compared to traditional running. Importantly, these benefits are influenced by individual differences in physical self-efficacy, which moderates the magnitude of cognitive gain. These findings highlight the importance of combining cognitive demands with physical activity and tailoring interventions based on children’s psychological profiles.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its information files. The data set supporting the findings of this study is also available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Waschbusch, D. A. et al. Inhibitory control, conduct problems, and callous-unemotional traits in children with ADHD and typically developing children. Dev. Neuropsychol. 47, 42–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/87565641.2021.1981900 (2022).

Johnson, K. A., White, M., Wong, P. S. & Murrihy, C. Aspects of attention and inhibitory control are associated with on-task classroom behaviour and behavioural assessments in children with high and low ADHD symptoms. Child Neuropsychol. 26, 219–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/09297049.2019.1650575 (2020).

Miller, N. V. et al. Investigation of a developmental pathway from infant anger reactivity to childhood inhibitory control and ADHD symptoms: interactive effects of early maternal caregiving. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry. 60, 762–772. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13047 (2019).

Liu, S. et al. Effects of acute and chronic exercises on executive function in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Psychol. 11, 554915. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.554915 (2020).

Amatriain-Fernández, S., García-Noblejas, E., Budde, H. & M. & Effects of chronic exercise on inhibitory control in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports. 31, 1196–1208. https://doi.org/10.1111/sms.13931 (2021).

Yanagisawa, H. et al. Acute moderate exercise elicits increased dorsolateral prefrontal activation and improves cognitive performance with Stroop test. NeuroImage 50, 1702–1710. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.12.023 (2010).

Chueh, T. Y. et al. Effects of a single bout of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity on executive functions in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 65, 102097. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2023.102097 (2023).

Tan, B. W. Z., Pooley, J. A. & Speelman, C. P. Efficacy of physical exercise interventions on cognition in ASD and ADHD: A meta-analysis. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 46, 3126–3143. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-016-2854-x (2016).

Moreau, D., Morrison, A. B. & Conway, A. R. A. An ecological approach to cognitive enhancement: complex motor training. Acta. Psychol. 157, 44–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2015.02.007 (2015).

Diamond, A. & Ling, D. S. Aerobic-exercise and resistance-training interventions among least effective for executive function enhancement. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 37, 100572. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcn.2018.05.001 (2019).

Vazou, S. et al. More than one road leads to rome: physical activity intervention effects on cognition in youth. Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 17, 153–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2016.1223423 (2019).

Xing, S. et al. Effects of exercise on children’s executive function: A review. J. Capital Univ. Phys. Educ. Sports. 28, 566–571 (2016).

Best, J. R. Effects of physical activity on children’s executive function: contributions of aerobic exercise research. Dev. Rev. 30, 331–351. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2010.08.001 (2010).

Tsai, Y. J. et al. Dose-response effects of acute aerobic exercise intensity on inhibitory control in ADHD children. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 15, 617596. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2021.617596 (2021).

Nejati, V. & Derakhshan, Z. Physical activity with/without cognitive demand on executive functions and ADHD symptoms. Expert Rev. Neurother. 21, 607–614. https://doi.org/10.1080/14737175.2021.1911648 (2021).

Chueh, T. Y. et al. Effects of cognitive demand during acute exercise on inhibitory control and its electrophysiological indices: A randomized crossover study. Physiol. Behav. 257, 114148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2023.114148 (2023).

Sergeant, J. A. The cognitive-energetic model: an empirical approach to attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 24 (1), 7–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0149-7634(99)00060-3 (2000).

Hillman, C. H., Erickson, K. I. & Kramer, A. F. Be smart, exercise your heart: exercise effects on brain and cognition. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 9, 58–65. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2298 (2008).

Herold, F. et al. fNIRS in exercise–cognition science: A methodology-focused review. J. Clin. Med. 7, 466. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm7120466 (2018).

Kim, H. Y. et al. fNIRS applications in human and animal brain function studies. Mol. Cells. 40, 523–532. https://doi.org/10.14348/molcells.2017.0153 (2017).

Van Rinsveld, S. M. et al. Aerobic exercise, cognition, and brain activity in adolescents with ADHD. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 55, 1445–1455. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000003169 (2023).

Hacker, S. et al. Acute effects of aerobic exercise on cognitive attention and memory: Duration-based dose-response and arousal effects. J. Clin. Med. 9, 1380. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9051380 (2020).

Ryckman, R. M. et al. Development and validation of a physical self-efficacy scale. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 42, 891–900. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.42.5.891 (1982).

Newark, P. E., Elsässer, M. & Stieglitz, R. D. Self-esteem, self-efficacy, and resources in adults with ADHD. J. Atten. Disord. 20, 279–290. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054713483235 (2016).

Bigelow, H. et al. Differential impact of acute exercise vs. mindfulness meditation on executive functioning and well-being in ADHD youth. Front. Psychol. 12, 660845. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.660845 (2021).

Sun, W., Yu, M. & Zhou, X. Effects of physical exercise on attention deficit and other major symptoms in children with ADHD: A meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 311, 114509. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2022.114509 (2022).

Diamond, A. Effects of physical exercise on executive functions: beyond movement. Annals Sports Med. Res. 2, 1011 (2015).

Monden, Y. et al. fNIRS-based classification of ADHD children using prefrontal hemodynamics during go/no-go task. NeuroImage: Clin. 9, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nicl.2015.06.011 (2015).

Peers, C. et al. Movement competence: association with physical self-efficacy and physical activity. Hum. Mov. Sci. 70, 102582. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.humov.2020.102582 (2020).

Schwarzer, R. Optimistic self-beliefs: assessment of general self-efficacy across cultures. World Psychol. 3, 177–190 (1997).

Cope, M. et al. Quantitation methods for cerebral near-infrared spectroscopy data. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 222, 183–189. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4615-9510-6_21 (1988).

Strangman, G. et al. Quantitative comparison of BOLD fMRI and NIRS during brain activation. NeuroImage 17, 719–731. https://doi.org/10.1006/nimg.2002.1227 (2002).

Miao, S. et al. Reduced prefrontal activation in ADHD children during go/no-go task: an fNIRS study. Front. NeuroSci. 11, 367. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2017.00367 (2017).

Lambrick, D. et al. Continuous vs. intermittent exercise effects on executive function in children. Psychophysiology 53, 1335–1342. https://doi.org/10.1111/psyp.12688 (2016).

Huang, C. C. J. et al. Mindfulness, executive function, social-emotional skills, and quality of life in Hispanic children. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 17, 7796. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17217796 (2020).

Querido, J. S. & Sheel, A. W. Regulation of cerebral blood flow during exercise. Sports Med. 37, 765–782. https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-200737090-00002 (2007).

Loprinzi, P. D. & Frith, E. Exercise protects against stress-induced memory impairment. J. Physiol. Sci. 69, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12576-018-0638-0 (2018).

Audiffren, M. et al. Acute aerobic exercise modulates executive control in random number generation. Acta. Psychol. 132, 85–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2009.06.008 (2009).

Tomporowski, P. D. et al. Exercise and children’s cognition: exercise characteristics and metacognition. J. Sport Health Sci. 4, 47–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2014.09.003 (2015).

Diamond, A. & Ling, D. S. Conclusions on justified vs. unjustified executive function interventions. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 18, 34–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcn.2015.11.005 (2016).

Haskell, R. E. Transfer of Learning: Cognition, Instruction, and Reasoning (Academic Press, 2001).

Daly-Smith, A. J. et al. Systematic review of physically active learning on children’s physical activity, cognition, and behavior. BMJ Open. Sport Exerc. Med. 4, e000341. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjsem-2018-000341 (2018).

Heemskerk, C. H. M. et al. Physical education intensity and cognitive demand on subsequent learning behaviour. J. Sci. Med. Sport. 23, 586–590. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2019.12.012 (2020).

Hillman, C. H. et al. Exercise effects on brain and cognition. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 9, 58–65. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2298 (2008).

Suwabe, K. et al. Positive mood during exercise enhances prefrontal executive function benefits: an fNIRS study. Neuroscience 454, 61–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2020.05.001 (2021).

Morawetz, C. et al. Prefrontal connectivity changes moderate emotion regulation. Cereb. Cortex. 26, 1923–1937. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhw005 (2016).

Ardila, A. Executive functions as a brain system. In Dysexecutive Syndromes, 29–41 (Springer, 2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-98857-0_3

Stevens, C. J. et al. Affective determinants of physical activity: A framework and review. Front. Psychol. 11, 568331. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.568331 (2020).

Lubans, D. et al. Physical activity for cognitive and mental health in youth: mechanisms review. Pediatrics 138, e20161642. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-1642 (2016).

Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol. Rev. 84, 191–215. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191 (1977).

Cronin-Golomb, L. M. & Bauer, P. J. Self-motivated and directed learning across the lifespan. Acta. Psychol. 232, 103816. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2022.103816 (2023).

Caprara, G. V. et al. The contribution of personality traits and self-efficacy beliefs to academic achievement: A longitudinal study. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 81, 78–96. https://doi.org/10.1348/2044-8279.002004 (2011).

Funding

This work is supported by funding from Fundamental Research Funds for China Institute of Sport Science(24–58).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.H. and C.Y.J. contributed to conceptualization, study design, manuscript drafting, and revision. C.Y.J. participated in subject recruitment and questionnaire collection. X.L.L. and S.H.H. contributed to table and figure preparation. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by China Institute of Sport Science.The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, H., Chen, Y., Xu, L. et al. Cognitively engaging running enhances inhibitory control and prefrontal activation in children with ADHD: the moderating role of physical self-efficacy. Sci Rep 15, 44313 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30981-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30981-8