Abstract

Bile reflux, resulting from pancreaticobiliary reflux (PBR), not only alters the chemical of bile but also constitutes a significant risk factor for the occurrence and development of gallbladder cancer. In previous studies, the authors identified a marked elevation of palmitic acid (PA) levels in the bile of patients with PBR. This study seeks to elucidate the mechanisms of promoting the migration of gallbladder cancer cells, with the objective of contributing novel strategies and theoretical foundations for the treatment of gallbladder cancer. We performed a cytotoxicity screening on the NOZ and GBC-SD human gallbladder cancer cell line using varying concentrations of palmitic acid. These following methodologies were employed to investigate the mechanism of PA in NOZ and GBC-SD cells. Intracellular lipid droplet accumulation was assessed using Oil red O staining, while cell migration capability was evaluated through the Transwell migration assay. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels were quantified using the superoxide anion fluorescent probe, Dihydroethidium (DHE), in conjunction with a ROS detection kit. The expression levels of relevant genes and proteins were analyzed using Western blot (WB), quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR), and immunofluorescence (IF) techniques. In NOZ and GBC-SD cells, it was observed that palmitic acid facilitates the accumulation of intracellular lipid droplets and diminishes cellular activity while augmenting the cells’ migratory capacity. Furthermore, elevated concentrations of PA have been shown to increase ROS levels in NOZ and GBC-SD cells. This elevation also activates the Nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) and the Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (NRF2)/Antioxidant Response Element (ARE) signaling pathways. The addition of the ROS inhibitor N-acetylcysteine (NAC) to NOZ and GBC-SD cells treated with high concentrations of PA effectively inhibits the enhancement of cell migration and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) induced by PA. PA promotes EMT in human gallbladder cancer cells by overproducing ROS and activating the NF-κB and NRF2/ARE signaling pathways, thereby facilitating increased migration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Gallbladder cancer represents one of the most prevalent forms of bile duct malignancies (BTC), ranking as the sixth most common malignant tumor within the digestive system and accounting for 80% to 90% of BTC cases1,2. Several risk factors are associated with the development of gallbladder cancer, including gallstones, gallbladder polyps, gallbladder adenomyosis, porcelain gallbladder, primary sclerosing cholangitis, and pancreaticobiliary reflux (PBR). Notably, PBR is identified as a significant risk factor for gallbladder cancer3, with numerous studies of varying levels of evidence indicating a strong correlation between PBR at both normal and abnormal bile duct junctions and the incidence of gallbladder cancer4,5,6.

In patients diagnosed with gallbladder cancer, the prevalence of Pancreaticobiliary Maljunction (PBM) varies between 8.7% and 16.7%7. A comprehensive national study conducted in Japan revealed that gallbladder cancer was present in 14.4% of individuals with PBM accompanied by biliary dilation and 39.2% of those without biliary dilation8. Furthermore, other studies have reported that the incidence of gallbladder cancer can be as high as 40.9% (9 out of 22 cases) in patients with PBR, whereas no cases of gallbladder cancer were observed in patients without PBR5.

PBR plays a significant role in the pathogenesis of gallbladder cancer. The reflux of pancreatic fluid into the biliary tract is activated by bile, leading to the production of carcinogenic substances, including activated pancreatic enzymes and secondary bile acids. These substances alter the internal environment of the biliary tract, causing direct or indirect damage to the gallbladder mucosa and bile duct epithelium. This damage initiates a cycle of repeated injury and repair of the epithelial cells in the gallbladder and bile ducts, resulting in mutations in associated oncogenes. Consequently, this process induces epithelial hyperplasia, epitheliosis, and epithelial dysplasia, ultimately culminating in the development of gallbladder cancer3,9. Numerous researchers have endeavored to elucidate the carcinogenic process from various perspectives; however, the intricate carcinogenic mechanisms underlying gallbladder cancer in patients with PBR remain inadequately understood.

Previous studies have indicated a positive correlation between free fatty acids (FFAs) in gallbladder bile and the PBR group, with elevated FFA levels identified as an independent risk factor for gallbladder wall thickenin10. Notably, the author’s prior investigations employed non-targeted metabolomics to identify differential metabolites in the bile of PBR patients, revealing a significant elevation of PA in this cohort11. The predominant constituent of FFAs is PA, which we hypothesize plays a significant role in the pathogenesis and progression of gallbladder cancer. PA, a saturated fatty acid, is known to mediate oxidative stress and the secretion of inflammatory cytokines by inducing the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in cells. Notably, elevated PA levels have been strongly correlated with increased aggressiveness in pancreatic, prostate, and breast cancers12,13,14, and PA has been shown to enhance the metastatic potential of cancer cells15. In this study, we investigated the impact of PA on the migratory capacity of NOZ gallbladder cancer cells.

Materials and methods

Reagents

Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) with high glucose, RPMI-1640 and fetal bovine serum were procured from GIBCO/Invitrogen (Waltham, MA). The Transwell inserts, featuring an 8 mm pore size, were sourced from Corning Incorporated. PA, fatty acid-free bovine serum albumin (BSA), ROS inhibitor N-acetylcysteine (NAC, A7250) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Antibodies against N-cadherin (22018-1-AP) and E-cadherin (20874-1-AP) were acquired from Proteintech, while the vimentin antibody (5471) was sourced from Cell Signaling Technology. Antibodies for GAPDH (AC054), NF-κB(A19653) and NRF2 (A21729) were procured from ABclonal Technology. Antibodies for HO1 (sc-136960) and NQO1(sc-32793) were procured from Santa Cruz Biotechnology.

The PA was initially dissolved in deionized water and subsequently saponified in a water bath maintained at 70 °C until complete dissolution was achieved. Following this, the resulting transparent PA solution was complexed with 20% BSA. The composite PA solution was then incorporated into the cell culture medium, with the optimal PA concentration determined via the CCK-8 assay for use in subsequent experiments. To control for potential interference, a BSA control group was established in the follow-up experiments.

Cell culture

This study utilized the human gallbladder cancer cell line NOZ, which was sourced from the Health Science Center of Japan.And the other human gallbladder cancer cell line GBC-SD was from the Shanghai Institue of Chinese Academy of Sciences. Following resuscitation, NOZ and GBC-SD cells were respectively cultured in DMEM/1640 complete medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum and incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Cell status is monitored daily. The culture medium is replaced with complete DMEM/1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum on the third day.The complete culture medium was supplemented with 1% penicillin-streptomycin. When cell proliferation covers more than 85% of the flask surface area, the cells are passaged at an appropriate ratio.

The CCK-8 assay

The cells were then seeded into a 96-well plate, and subsequent experiments were conducted once the cells reached approximately 70–80% confluence, as observed under a microscope.Three technical repeat holes were set in each independent repetition of the experiment. PA was administered at concentration gradients of 0, 0.1, 0.4, and 0.8 mM, and the cells were cultured for an additional 12 h. Subsequently, the CCK-8 solution was added, and absorbance was measured at a wavelength of 450 nm to assess the impact of palmitic acid on NOZ and GBC-SD cell viability.

Oil red O staining

The cells were inoculated into a 12-well plate and allowed to proliferate until reaching 70–80% confluence. Three technical repeat holes were set in each independent repetition of the experiment. Subsequently, the reagent was administered and incubated for 12 h in accordance with the experimental protocol. Following this treatment, the cells were fixed using paraformaldehyde and subsequently rinsed with isopropyl alcohol for 15 s. A volume of 0.5 mL of Oil red O dye was then applied and incubated for 30 min at room temperature. After discarding the dye solution, the cells were thoroughly washed, and the nuclei were counterstained with hematoxylin dye solution for 1–2 min, followed by three rinses with deionized water. The stained cells were then examined microscopically to assess Oil red O staining.

The transwell experiment

When the cells reached 70% to 80% confluence, they were subjected to serum starvation for 12 h using a serum-free medium, followed by enzymatic digestion with pancreatic enzymes. Subsequently, 1.0 × 10^5 cells were seeded into the upper chamber of a Transwell apparatus. The lower chamber was supplemented with varying concentrations of PA (0, 0.1, 0.4, and 0.8 mM). After a 12-hour incubation period, the cells on the upper surface of the membrane were carefully removed using a cotton swab. The remaining cells were fixed and stained with 1% crystal violet. The stained cells were then examined under an inverted microscope at 100x magnification, and cell migration was quantified. The migratory capacity of cells across different experimental groups was subsequently compared. All experiments were performed independently at least three times.

The quantification of intracellular ROS and superoxide anion free radical (O2•−) production

The induction of cellular ROS by PA was assessed using the fluorescent dye 2,7-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA). Cells were cultured in 12-well plates and allowed to reach 70–80% confluence before the addition of PA, which was administered for 12 h in accordance with the experimental protocol. Following this treatment, the cells were incubated with 10 µM DCFH-DA for 30 min and subsequently washed three times. Fluorescence was observed using a Leica fluorescence microscope (Germany). Quantification of the results was performed by flow cytometry, and the data were expressed as the mean DCF fluorescence intensity. Dihydroethidium (DHE) fluorescent dye was used to assess PA-induced O2•− generation in cells. The treatment protocol mirrored that employed in the cell ROS assay. Specifically, treated cells were incubated with 2 µM DHE at 37 °C for 30 min, subsequently washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and then examined using a fluorescence microscope.

Immunofluorescence and histological analysis

NOZ and GBC-SD cells were seeded into a 24-well cell culture plate at a density of 1 × 10^5 cells per well and maintained in a cell incubator for 24 h. Following a 12-hour intervention as per the experimental protocol, fixation was conducted. A PBS solution containing 0.1% Triton X-100 was utilized for infiltration over a period of 10 min, followed by sealing for 90 min. Antibody diluent was used to dilute antibody NF-κB and NRF2 antibody at a ratio of 1:400, HO1 and NQO1 antibodies at a ratio of 1:300. The primary antibody was incubated at 4 °C overnight. Subsequently, the fluorescent secondary antibody was added and incubated on a shaker for 1 h, protected from light exposure. The nuclei were stained using DAPI. All experiments were performed independently at least three times. Olympus Fluorescence microscopy was employed to capture images.The acquired images were analyzed using ImageJ software to determine the mean fluorescence intensity.

qRT-PCR

Total RNA from cells or tissues was extracted from cells or tissues using the RNAiso Plus reagent (TaKaRa, Japan). The PrimeScript™ RT reagent kit with gDNA Eraser (Perfect Real Time) (TaKaRa) was employed for the reverse transcription of RNA into cDNA which was then utilized for qRT-PCR analysis with SYBR Mix (Yeasen, Shanghai, China), specific primers (Table S1) and a LightCycler System (Roche, Switzerland). The gene expression levels were calculated and normalized using the 2−ΔΔCt method relative to GAPDH.

Statistical analysis

The data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS 22.0 software. Depending on the data type, statistical analyses were performed using t-tests, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), and the least significant difference (LSD) test for multiple post hoc comparisons. In this study, we employed a statistical significance threshold where a p-value less than 0.05 is denoted by # and *, a p-value less than 0.01 by ## and **, and a p-value less than 0.001 by ### and ***.

Results

PA enhanced the migration of human gallbladder cancer cells

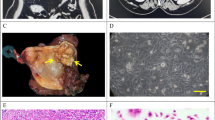

Initially, NOZ and GBC-SD cells were treated with varying concentrations of PA (0, 0.05, 0.1, 0.4, and 0.8 mM) for a duration of 12 h. As illustrated in Fig. 1A and Figure S1A (Additional file 1), the cytotoxic effects of PA at these concentrations were assessed. The results indicated that PA exhibited significant cytotoxicity in NOZ and GBC-SD cells compared to the control group, with cell viability reduced to 52.56% and 47.25% at a concentration of 0.4 mM and further decreased to 22% and 21.92% at 0.8 mM. Subsequently, the NOZ (Fig. 1B) and GBC-SD (Additional file 1:Figure S1B) cells were stained with Oil red O. The findings indicated that lipid accumulation was not significantly observed in cells treated with low concentrations (0 and 0.1 mM) of PA, whereas substantial lipid accumulation was evident in cells exposed to higher concentrations (0.4 and 0.8 mM) of PA. Oil red O staining confirmed that lipid droplet accumulation intensified with increasing PA concentrations. The impact of PA on the migratory capacity of NOZ cells was further investigated using a Transwell assay. The results demonstrated that elevated concentrations of PA significantly enhanced the migratory ability of NOZ cells, with the most pronounced effect observed at a concentration of 0.4 mM (Fig. 1C, D). These findings suggest that PA is absorbed by gallbladder cancer cells, and a concentration of 0.4 mM notably influences cell activity and significantly enhances the migratory capacity of NOZ cells. Consequently, a PA concentration of 0.4 mM was selected for lipotoxic exposure in subsequent experiments.

The effect of different concentrations of PA or carriers as controls on the activity and migration ability of NOZ cells after 12 h of stimulation: A Statistical results of CCK8 experiment (n = 3). B Cell images stained with Oil Red 0, Scale bar 50 μm. C, D Quantitative analysis and statistical results of Transwell test images (n = 3). Scale bar 100 μm. All results are presented as the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

PA stimulation led to an up-regulation of ROS levels and activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway in NOZ and GBC-SD cells

Excess ROS function as potent oxidizing agents, inflicting considerable damage on cellular components, including lipids, proteins, and DNA. Previous research has demonstrated that PA can induce cellular lipotoxicity through the generation of excess ROS. Our study demonstrated that treatment of NOZ and GBC-SD cells with 0.1 and 0.4 mM PA for 12 h induces oxidative stress in gallbladder cancer cells. Utilizing the DCFH-DA probe, we observed that 0.4 mM PA significantly increased ROS production in NOZ cells, reaching levels 2.5 times greater than those in the control group (Fig. 2A, C). Concurrently, fluorescence microscopy revealed that 0.4 mM PA markedly enhanced the fluorescence intensity of DHE in NOZ cells (Fig. 2B). Similarly, it can be observed that 0.4 mM PA significantly enhances the fluorescence intensity of DCFH-DA and DHE in GBC-SD cells (Additional file 1:Figure S2A-B).

Furthermore, the transcription factor NF-κB was identified as a key signal transduction molecule activated in response to oxidative stress. Consequently, we investigated the activation of NF-κB (p65) in NOZ (Fig. 2D-E) and GBC-SD cells (Additional file 1:Figure S2C-D). The experimental results show that, the nucleation effect of p65 was notably pronounced in the 0.4 mM PA stimulation group, with a significant increase in basal NF-κB activity (NOZ and GBC-SD cells increased of 1.92-fold and 1.82-fold, respectively) compared to the control group.

The effect of different concentrations of PA on ROS/NF kB (p65) in NOZ cells treated for 12 h. A Intracellular ROS levels under fluorescence microscopy, B Intracellular O2•− levels under fluorescence microscopy, C Statistical results of flow cytometry after DCFH-DA fluorescent probe treatment (n = 3), D NF-κB (p65) into the nucleus under fluorescence microscope image (The white arrows mean an increase in nuclear translocation.). E NF-κB (p65) fluorescence quantitative analysis and statistical results (n = 3, AOD means average optical density). Scale bar 50 μm. All results are presented as the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

NAC inhibited the PA-induced up-regulation of ROS levels and the activation of the NRF2/ARE signaling pathway

In tumor cells, excessive production of ROS frequently induces the upregulation of various intracellular antioxidant mechanisms to mitigate the deleterious effects of ROS, thereby preserving cellular viability and proliferative capacity. This response is particularly evident in the activation of the NRF2/ARE signaling pathway. To investigate the impact of ROS upregulation on PA-induced oxidative stress in NOZ and GBC-SD cells, we employed the ROS inhibitor NAC as an experimental intervention. Specifically, we treated gallbladder cancer cells with 0.4 mM PA for a duration of 12 h, concurrently administering 10 mM NAC. The experimental results showed that NAC was observed to effectively inhibit the increase of ROS and O2•− in NOZ (Fig. 3.A-C) and GBC-SD cells (Additional file 1:Figure S3A-B) following the intervention with 0.4 mM PA.

Furthermore, immunofluorescence analysis demonstrated that 0.4 mM PA significantly enhances the fluorescence intensity of NRF2 and its downstream targets—NAD(P)H: quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1) and Heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1). This suggests activation of the NRF2/ARE signaling pathway. When NAC was introduced as an intervention, there was a marked inhibition of NRF2 translocation to the nucleus, accompanied by a downregulation in the expression levels of NQO1 and HO-1 (Fig. 3D-I; Additional file 1:Figure S3C-H). Collectively, these findings indicate that PA may facilitate NOZ and GBC-SD cells migration by elevating ROS levels and activating the NRF2/ARE signaling pathways.

Effects of NAC on ROS upregulation and NRF2/ARE in NOZ cells induced by 0.4mM PA. A Intracellular ROS levels under different experimental conditions under a fluorescence microscope. B Intracellular O2•− levels under a fluorescence microscope. C Flow cytometry statistical results after DCFH-DA fluorescent probe treatment (n = 3). D, F, H NRF2, HO1, NQO1 immunofluorescence images, E, G, I NRF2, HO1, NQO1 fluorescence quantitative analysis and statistical results (n = 3, AOD means average optical density). Scale bar 50 μm. All results are presented as the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

The downregulation of ROS resulted in the inhibition of NF-κB activation and migration in NOZ and GBC-SD cell

To elucidate the specific role of ROS upregulation in the PA-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) process in NOZ and GBC-SD cells, we treated NOZ and GBC-SD cells with 0.4 mM PA while concurrently administering 10 mM NAC for 12 h. As illustrated in Fig. 4A, B and a comparative analysis of mRNA levels of interleukin-1 (IL-1) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) in NOZ cells between the PA-treated group and the control group revealed that PA stimulation led to a significant upregulation in the expression levels of IL-1 and TNF-α, with increases of 1.88-fold and 1.7-fold, respectively. Pretreatment with NAC effectively counteracted the PA-induced elevation of IL-1 and TNF-α levels and further inhibited the activation of NF-κB in NOZ (Fig. 4C-D) and GBC-SD (Additional file 1:Figure S4A-B) cells.To enhance the reliability of the conclusion on NF-κB pathway activation, we detected the protein level of phosphorylated p65. Western blot results showed that the phosphorylation level of p65 was significantly upregulated in NOZ cells (Additional file 1:Figure S5A) and GBC-SD cells (Additional file 1:Figure S4C) after PA treatment; At the same time, subcellular separation experiments further demonstrated that PA promoted nuclear translocation of P65 cells in NOZ (Additional file 1:Figure S5B-C) and GBC-SD (Additional file 1:Figure S4D-E). Moreover, at protein levels, NAC significantly reduced the expression levels of PA-induced EMT marker proteins, N-cadherin and Vimentin, while upregulating the expression of E-cadherin (Fig. 4E). Meanwhile, at RNA levels, NAC significantly reduced the expression levels of PA-induced EMT marker proteins, N-cadherin and Vimentin in NOZ (Fig. 4F-H) and GBC-SD (Additional file 1:Figure S4F-H) cells induced by PA, while upregulating the expression of E-cadherin. As anticipated, the findings from the Transwell migration assay corroborated that NAC significantly inhibited PA-induced migration of NOZ cells (Fig. 4I-J). To confirm that the same concentration of PA could enhance the migration of both NOZ and GBC-SD cells, we performed a wound healing assay. The results showed that treatment with 0.4 mM PA significantly increased the migratory capacity of NOZ (Additional file 1:Figure S5D-E) and GBC-SD (Additional file 1:Figure S4I-J) cells. Notably, this PA-induced cell migration was markedly suppressed by NAC.These results imply that the up-regulation of ROS induced by PA is a crucial factor in facilitating NOZ and GBC-SD cell migration.

Effects of NAC on 0.4mM PA-induced NF-kB (p65) activation and EMT in NOZ cells. Under the intervention of different samples, intracellular A IL-1β expression level (n = 3). B TNF-α expression level (n = 3). C NF-κB (p65) intracellular nuclear image under fluorescence microscope, D NF-κB (p65) fluorescence quantitative analysis and statistical results (n = 3), E Western blot of imaging results demonstrating the presence of NAC significantly reduced the expression levels of PA-induced N-cadherin and Vimentin, upregulating the expression of E-cadherin in NOZ cells, F–H Levels of E-cadherin, N-cadherin and Vimentin mRNA were assessed by RT-PCR (n = 3). I Transwell test image, J Transwell test statistical results (n = 3). (AOD means average optical density). Scale bar 50 μm. All results are presented as the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Discussion

Building upon previous research and the established role of PA in promoting migration and invasion in various tumors, including prostate, pancreatic, and liver cancers12,13,16, this study examined the impact of elevated bile metabolite PA in PBR on the migratory capacity of gallbladder cancer cells. We hypothesized that the ROS/inflammatory cascade reaction serves as the primary mechanism facilitating this process. Exposure to PA results in the excessive production of intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS)17,18,19, as evidenced by DCFH-DA and DHE staining. ROS, acting as a central activator, subsequently triggers two critical downstream pathways.

Firstly, ROS is a significant activator of the NF-κB signaling pathway. Following PA treatment, we observed marked nuclear translocation of the p65 subunit, indicative of NF-κB activation. The activated NF-κB then transcribes and upregulates pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β and TNF-α, creating an inflammatory microenvironment that supports tumor progression20. Notably, the ROS inhibitor NAC effectively inhibited the PA-induced nuclear translocation of p65 and the expression of associated cytokines, indicating that NF-κB activation is highly contingent upon ROS. Subsequently, the NF-κB-mediated inflammatory response prompted epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), characterized by the downregulation of E-cadherin expression and the upregulation of N-cadherin and vimentin, ultimately enhancing the migratory capacity of NOZ cells21,22,23,24. Treatment with N-acetylcysteine (NAC) was able to reverse the expression of EMT markers and inhibit cell migration, thereby further substantiating that ROS serve as the primary upstream trigger for the pro-migratory effect induced by PA.

Concurrently, the ROS surge induced by PA also activated the cellular defense mechanism, namely the NRF2/ARE signaling pathway. This activation resulted in the accumulation of NRF2 in the nucleus and the upregulation of its downstream target genes, HO-1 and NQO1. Such a response represents a typical cellular adaptation to oxidative stress, aiding in the mitigation of ROS-induced damage and enhancing cellular survival25,26. Although existing literature suggests that NF-κB may play a role in regulating NRF2 transcription27, this study only confirmed their concurrent activation in response to PA, without elucidating a causal relationship. The inhibition of NRF2 activation by NAC further suggests that the activation of this pathway is a secondary response to ROS production. We propose that the antioxidant response facilitated by NRF2 may enable cancer cells to withstand the detrimental effects of a high ROS environment, thereby promoting the survival of cells undergoing EMT and migration28,29,30,31. The survival-promoting effect of NRF2 may act synergistically with the pro-migration influence of the NF-κB/EMT axis to collectively enhance the metastatic potential of gallbladder cancer cells.

In conclusion, this study elucidates the potential association between PBR and the pathogenesis and progression of gallbladder cancer from a metabolic perspective, and clarifies the mechanism by which PA serves as a risk factor for early metastasis of gallbladder cancer. These findings not only advance the understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying PBR-related gallbladder diseases but also provide a crucial scientific foundation for the development of novel therapeutic strategies targeting this pathway.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

References

Sung, H. et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin 71(3), 209–249. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21660 (2021).

Bray, F. et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin 74(3), 229–263. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21834 (2024).

Funabiki, T., Matsubara, T., Miyakawa, S. & Ishihara, S. Pancreaticobiliary maljunction and carcinogenesis to biliary and pancreatic malignancy. Langenbecks Arch. Surg 394(1), 159–169. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-008-0336-0 (2009).

Kimura, K. et al. Association of gallbladder carcinoma and anomalous pancreaticobiliary ductal union. Gastroenterology 89(6), 1258–1265. https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-5085(85)90641-9 (1985).

Fujimoto, T. et al. Elevated bile amylase level without pancreaticobiliary maljunction is a risk factor for gallbladder carcinoma. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Sci 24(2), 103–108. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhbp.421 (2017).

Sai, J. K., Suyama, M., Kubokawa, Y. & Nobukawa, B. Gallbladder carcinoma associated with pancreatobiliary reflux. World J. Gastroenterol. 28(40), 6527–6530. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v12.i40.6527 (2006).

Beltran, M. A. Pancreaticobiliary reflux in patients with a normal pancreaticobiliary junction: pathologic implications. World J. Gastroenterol. 28(8), 953–962. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v17.i8.953 (2011).

Morine, Y. et al. Clinical features of pancreaticobiliary maljunction: update analysis of 2nd Japan-nationwide survey. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Sci. 20(5), 472–480. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00534-013-0606-2 (2013).

Tsuchida, A., Itoi, T., Aoki, T. & Koyanagi, Y. Carcinogenetic process in gallbladder mucosa with pancreaticobiliary maljunction (Review). Oncol Rep. 10(6), 1693–1699. https://doi.org/10.3892/or.10.6.1693 (2003).

Xiang, Y. et al. Free fatty acids and triglyceride change in the gallbladder bile of gallstone patients with pancreaticobiliary reflux. Lipids Health Dis. 31(1), 97. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12944-021-01527-4 (2021).

Da, X. et al. Identification of changes in bile composition in pancreaticobiliary reflux based on liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry metabolomics. BMC Gastroenterol. 2(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-023-03097-4 (2024).

Binker-Cosen, M. J. et al. Palmitic acid increases invasiveness of pancreatic cancer cells AsPC-1 through TLR4/ROS/NF-kappaB/MMP-9 signaling pathway. Biochem Biophys. Res. Commun. 26(1), 152–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.01.051 (2017).

Laurent, V. et al. Periprostatic adipocytes act as a driving force for prostate cancer progression in obesity. Nat Commun. 12, 10230. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms10230 (2016).

Dirat, B. et al. Cancer-associated adipocytes exhibit an activated phenotype and contribute to breast cancer invasion. Cancer Res. 1(7), 2455–2465. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3323 (2011).

Pascual, G. et al. Targeting metastasis-initiating cells through the fatty acid receptor CD36. Nature 5(7635), 41–45. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature20791 (2017).

Xu, W. et al. O-GlcNAc transferase promotes fatty liver-associated liver cancer through inducing palmitic acid and activating Endoplasmic reticulum stress. J Hepatol. 67(2), 310–320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2017.03.017 (2017).

Su, H. et al. Procyanidin B2 ameliorates free fatty acids-induced hepatic steatosis through regulating TFEB-mediated lysosomal pathway and redox state. Free Radic Biol. Med. 126, 269–286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2018.08.024 (2018).

Chen, Q. et al. Astragalosides IV protected the renal tubular epithelial cells from free fatty acids-induced injury by reducing oxidative stress and apoptosis. Biomed Pharmacother. 108, 679–686. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2018.09.049 (2018).

Sun, Y. et al. Berberine attenuates hepatic steatosis and enhances energy expenditure in mice by inducing autophagy and fibroblast growth factor 21. Br J. Pharmacol. 175(2), 374–387. https://doi.org/10.1111/bph.14079 (2018).

Nakada, S. et al. Roles of Pin1 as a key molecule for EMT induction by activation of STAT3 and NF-kappaB in human gallbladder cancer. Ann Surg. Oncol. 26(3), 907–917. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-018-07132-7 (2019).

Prieto-Garcia, E., Diaz-Garcia, C. V., Garcia-Ruiz, I. & Agullo-Ortuno, M. T. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in tumor progression. Med Oncol. 34(7), 122. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12032-017-0980-8 (2017).

Shen, H. et al. PLEK2 promotes gallbladder cancer invasion and metastasis through EGFR/CCL2 pathway. J Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 10(1), 247. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13046-019-1250-8 (2019).

Chen, W. et al. M2-like tumor-associated macrophage-secreted CCL2 facilitates gallbladder cancer stemness and metastasis. Exp Hematol. Oncol. 13(1), 83. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40164-024-00550-2 (2024).

Xu, S., Zhan, M. & Wang, J. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in gallbladder cancer: from clinical evidence to cellular regulatory networks. Cell. Death Discov. 3, 17069. https://doi.org/10.1038/cddiscovery.2017.69 (2017).

Ahmed, S. M., Luo, L., Namani, A., Wang, X. J. & Tang, X. Nrf2 signaling pathway: pivotal roles in inflammation. Biochim Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 1863(2), 585–597. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbadis.2016.11.005 (2017).

Chung, J. et al. Correlation between oxidative stress and transforming growth factor-beta in cancers. Int J. Mol. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms222413181 (2021).

Marra, F. Nuclear factor-kappaB Inhibition and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: inflammation as a target for therapy. Gut 57(5), 570–572. https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.2007.141986 (2008).

Wang, J. et al. Correlation of Nrf2, HO-1, and MRP3 in gallbladder cancer and their relationships to clinicopathologic features and survival. J Surg. Res. 164(1), e99-105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2010.05.058 (2010).

Lin, L. et al. Nrf2 signaling pathway: current status and potential therapeutic targetable role in human cancers. Front. Oncol. 13, 1184079. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2023.1184079 (2023).

Zhang, L. et al. Propofol induces proliferation and invasion of gallbladder cancer cells through activation of Nrf2. J Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 19(1), 66. https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-9966-31-66 (2012).

Tian, L. et al. aPKCiota promotes gallbladder cancer tumorigenesis and gemcitabine resistance by competing with Nrf2 for binding to Keap1. Redox Biol. 22, 101149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redox.2019.101149 (2019).

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from Shaanxi key research and development program Project (grant no. 2023-YBSF-549) and Shaanxi key research and development program Project (grant no. 2020-SF058).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

In this study, HWL and HS helped to develop the research idea. XBD and QYG completed main experiments, supervised data analysis and drafted the manuscript. YXL and JJH conceptualized the research idea and design. JTM and LL revised the manuscript, and interpreted the data. MF 、XJZ 、TZG and ZLQ helped clean the data. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Da, X., Guo, Q., Lu, Y. et al. Bile metabolite palmitic acid augments the migration of gallbladder cancer cells through the ROS/NF-кB signaling pathway. Sci Rep 16, 1262 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31035-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31035-9