Abstract

Angiomyolipoma is the prototype of the perivascular epithelioid cells (PEC) lesions whose pathogenesis is usually determined by mutations of the TSC1/2 genes, with eventual deregulation of the mTOR pathway, whereas a small subset of PEComas is driven by rearrangements of the TFE3 gene. It is well known that the mTOR complex protein is involved in autophagy, and the role of STING has recently been demonstrated in this process. As relevant STING immunolabelling in the PEC lesions of the kidney has already been reported, we sought to further investigate the immunohistochemical expression of this marker in a series of extrarenal PEComas. Thirty-nine PEComas from different sites (17 uterus, 5 lungs, 4 pancreas, 4 retroperitoneum, 3 soft tissues, 3 liver, 1 lymph node, 1 bowel, and 1 urinary bladder) were collected from 36 patients, including 35 primary tumors and 4 distant metastases. The cohort encompassed 27 epithelioid PEComas, 8 clear cell sugar tumors, and 4 lymphangioleiomyomatoses. Immunostaining for STING was carried out. Strong and diffuse immunolabeling of STING was documented in 90% of PEComas (35/39), with concordant expression in primary and metastatic samples (4/4, 100%). No TFE3 gene rearrangement was documented by FISH, although one STING-negative case showed minimally split fluorescent signals separated by a signal diameter. Our findings support the hypothesis of a STING-mediated alteration of the autophagic process in the PEComas and suggest a potential biological and therapeutic role for this marker and its related pathway.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Perivascular epithelioid cell (PEC) tumors, also known as “PEComas,” encompass a broad group of neoplasms characterized by the presence of distinctive progenitor PEC defined by clear granular cytoplasm and immunohistochemical staining for melanogenic and muscular markers1. The PEC cell was initially described in angiomyolipoma and clear cell sugar tumor of the lung2,3,4, and later identified in virtually all anatomical sites, including the pancreas, the uterus, and the soft tissues, among others5,6,7, leading to these tumors being called PEComas. PEComas may occur sporadically or in a hereditary syndrome named Tuberous Sclerosis Complex (TSC)8,9. In both scenarios, these neoplasms are typically driven by TSC1 or TSC2 gene mutations, which upregulate the mTOR downstream pathway10, whereas in the less frequent TFE3-rearranged PEComa, this does not occur11. The MTORC1 complex, in particular, plays a key inhibitory role in autophagy, a degradative cellular process activated under stress or starvation conditions12. Although autophagy should ideally be repressed in PEComas, experimental data indicate low basal autophagy levels in angiomyolipomas, including the overexpression of microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3B (LC3B), a crucial molecule involved in autophagosome formation13. The mechanism underlying this observation remains incompletely understood. In 2021, Alesi and colleagues demonstrated TFEB, a protein codified by a master gene for lysosomal biogenesis and involved in autophagy, in TSC1/2-deficient cells. We would assume TFEB to be phosphorylated in the cells with mTOR pathway activation, while the finding of unphosphorylated TFEB able to enter the nucleus was unexpected14. Recently, Lv et al. and Xu et al. discovered that the cGAS-STING pathway seems to induce the nuclear translocation of TFEB15,16. Triggered by double-strand DNA fragments, the cGAS-STING pathway has been associated with an inflammatory signature due to the upregulation of type I interferons and related genes17. Additionally, it has been demonstrated that STING can modulate the autophagic process by promoting the lipidation of the LC3B molecule18.

In recent years, the role of STING in cancer pathogenesis has been extensively studied, particularly in the kidney19,20,21, including in PEC lesions such as classic and epithelioid angiomyolipoma, intraglomerular PEC lesions, and angiomyolipomas with epithelial cysts22. However, no data regarding STING’s expression in PEComas outside the kidney is currently available. Therefore, in the present study, we aimed to investigate the immunohistochemical expression of STING in a series of extrarenal PEComas, analyzing its potential biological, diagnostic, and therapeutic implications.

Results

Patients and samples

Twenty-six patients were females, while 7 were males (F: M ratio 3.7:1). Gender information was missing in three patients. Age at diagnosis spanned from 6 to 84 years (mean 50, median 52). Two patients had TSC (patients 7 and 18). Tumors ranged in size from 0.4 to 23 cm (mean 6.7 cm, median 5.5 cm). As for the specific morphological subtypes, the cohort accounted for 39 tumors from 36 patients, including 14 uterine epithelioid PEComas, two of which with histologically documented metastases to the liver, the bowel, and the retroperitoneum (patients 1 and 2), 8 clear cell sugar tumors (4 from the lung and 4 from the pancreas), 4 lymphangioleiomyomatoses (2 from pelvic nodes, 1 from the lung, and 1 from the uterus), 2 hepatic epithelioid PEComas (one which representing a metastasis from a primary urinary bladder tumor, patient 35), and epithelioid PEComas from various sites (3 from the soft tissues, 2 from the retroperitoneum, 1 from the uterine cervix, and 1 from the urinary bladder).

Immunohistochemistry and FISH

Immunohistochemical analysis was performed in all but one case, namely the primary uterine neoplasm from patient 2, as no material was available for testing, while FISH was not carried out in four of the thirty-nine samples. STING was positive in 90% of the PEComas of the whole series (35/39), with consistent expression between primary and metastatic tumors (4/4, 100%). All the positive samples showed intense marker expression (3+), so that the overall H-score ranged from 0 to 300 (mean 237, median 150). Regarding mTOR-related factors, positive cytoplasmic p-4EBP1 and p-S6K1 staining was observed in 75% (15/20) epithelioid PEComas (Fig. 1), 67% (2/3) LAMs, 67% (2/3) clear cell sugar tumors of the lung, and 50% (2/4) clear cell sugar tumors of the pancreas. To note, all STING-negative PEComas revealed no p-4EBP1 and p-S6K1 labeling.

Epithelioid PEComa

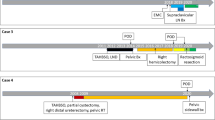

Of the 39 cases considered, 27 were found to be epithelioid PEComas, composed of large, densely packed cells ranging from spindle elements with moderate nuclear atypia to strongly atypical polygonal cells with a variable number of multinucleated cells. Eighteen out of twenty-seven epithelioid PEComas (67%) showed strong and diffuse expression of STING, ranging from 40% to 80% of neoplastic cells (H-score 120–300) (Fig. 2). In five cases, STING staining was confined to the periphery of the section, likely due to a fixation issue. Notably, one of the STING-negative cases was a small biopsy from a large 18-cm retroperitoneal mass (patient 36). Twenty-three epithelioid PEComas were tested by FISH, and none of them demonstrated TFE3 gene rearrangement. However, one case (patient 29) showed minimally split fluorescent signals in which a signal diameter separated the fluorescent signals. To note, this tumor failed to stain for STING, p-4EBP1, and p-S6K1 by immunohistochemistry (Fig. 3).

Epithelioid PEComa. Hematoxylin and eosin pictures from a uterine neoplasm, composed of eosinophilic cells admixed with thick-walled vessels [a], and a urinary bladder tumor, made up of large cells with prevalent clear cytoplasm [c and inset]. Both samples diffusely labeled for STING [b and d] (original magnifications 50X inset, 100X a, b, and d).

Lymphangioleiomyomatosis

The four lymphangioleiomyomatoses were strongly and diffusely positive for STING, virtually staining all tumor cells (H-score 300) (Fig. 4). FISH analysis was performed in three samples, failing to reveal TFE3 gene rearrangements.

Clear cell sugar tumor

All clear cell “sugar” tumors immunolabelled for STING, with most of them showing significant expression, spanning from 40% to 100% neoplastic elements (H-score 120–300) (Fig. 5), and only one pancreatic tumor (patient 31) staining just focally for such a marker (10% of the cells). None of the six samples tested showed any TFE3 gene alteration by FISH.

The clinical, pathological, immunohistochemical, and FISH findings of the PEComas of the present series are summarized in Table 1.

Discussion

PEC lesions encompass a broad group of pathological processes, including classic angiomyolipoma, epithelioid angiomyolipoma (so-called “pure” epithelioid PEComa), clear cell sugar tumor, and lymphangioleiomyomatosis, morphologically sharing a sort of perivascular distribution of neoplastic cells. Most PEC lesions are driven by inactivating mutations of the TSC1/TSC2 genes, which cause the MTORC1 complex to trigger downstream pathways, such as melanogenesis and autophagy10. Historically, MTORC1 has been considered an autophagy inhibitor; however, published evidence supports low basal autophagy levels in angiomyolipomas despite poorly understood molecular mechanisms13. Like renal PEComas22, in the present study, we have demonstrated high STING immunohistochemical expression in a broad spectrum of extrarenal PEComas (90% of the tumors), supporting a possible role for such a molecule and its related pathway in regulating autophagic status with biological and therapeutic implications.

Firstly, in our series, we found common and often diffuse STING labeling in primary tumors and their corresponding distant metastases (4/4, 100%). Unlike other instances where its expression was correlated with aggressive histological features and the development of metastases, such as clear cell19 and fumarate hydratase (FH)-deficient renal cell carcinoma21, our data suggest a critical role for STING in the tumorigenesis of conventional PEComas. Indeed, the underlying molecular bases of STING activation in PEC lesions have not yet been discovered. However, crosstalk between STING and MTORC1 has been documented in experimental models23. Specifically, mTOR inhibitors may cause STING-mediated interferon-α production downregulation in monocytes from lupus erythematosus patients24. Conversely, in preclinical obesity models, STING and its downstream effector TBK1 may inhibit MTORC1 and reduce fat storage25. As STING can trigger the autophagy process through LC3B lipidation, this activation may be responsible for both reducing obesity in such models and maintaining low autophagy levels in angiomyolipoma and other PEComas, despite MTORC1 activation. Similarly, it is widely acknowledged that TFEB, a transcriptional factor of the MiTF family working as a master of regulation of key cellular processes like lysosome and endosome homeostasis, is constantly active and moved to the nucleus in PEComas26. However, the mechanisms underlying TFEB activation in these tumors have remained unknown for decades, as constitutive MTORC1 stimulation should ideally lead to TFEB downstream phosphorylation and, then, ubiquitin-mediated degradation14. It has been recently shown that non-canonical STING-induced autophagy depends on the recruitment and lipidation of molecules like LC3B and GABARAPs, which sequester the FNIP/FLCN complex from MTORC127. While this interaction does not inhibit the general kinase activity of MTORC1, it sterically keeps this enzymatic complex from phosphorylating MiTF/TFE3/TFEB27. Thus, these latter factors may translocate to the nucleus where they can prompt the transcription of key genes for lysosome and phagosome biogenesis (Fig. 6). In this context, electron microscopy studies have revealed small granules and crystalloids in renal28 and extrarenal PEComa cells6,29 that could represent autolysosomes/autophagosomes, as they are also enriched with lysosomal molecules like cathepsin K and CD6830,31,32. Theoretically, mitochondrial dysfunction could also play a role in enhancing the cGAS-STING signaling pathway in PEComas. As demonstrated in FH-deficient renal cell carcinoma, the cytoplasmic extrusion of mtDNA can trigger this pathway33,34. In this view, functional alterations of key mitochondrial proteins have been documented in lymphangioleiomyomatosis35, and the first case of a uterine PEComa displaying FH loss has been reported36. Furthermore, experimental models have also shown that dephosphorylated TFEB may also move to the mitochondrial matrix, where it can interact with electron transport chain complex I and other proteins to regulate reactive oxygen production and the inflammatory response37.

Schematic illustration of the biological mechanisms underlying STING activation, autophagy, and TFEB nuclear localization in conventional PEComas. Still partially unknown stimuli, such as mitochondrial damage and/or crosstalk with the MTORC1 signaling (dotted arrows), cause dsDNA cytoplasmic accumulation and cGAMP formation via cGAS, triggering STING. Among its various downstream pathways, STING prompts the autophagy process through the lipidation of key phagosome proteins, such as LC3B and those of the GABARAPs family. Once modified, these latter can sequester the FNIP/FLCN molecules from the MTORC1 complex, hyper-activated due to TSC1/TSC2 mutations, preventing it from phosphorylating the TFEB and MITF transcriptional factors but without altering its kinase activity. Thus, rescued from ubiquitin-dependent proteasome degradation, TFEB/MITF may move to the nucleus, where they can enhance the transcription of key genes involved in autophagosome and lysosome biogenesis. mtDNA: mitochondrial DNA, dsDNA: double-stranded DNA.

These considerations notwithstanding, regardless of the peculiar molecular bases, relying on our data of high concordance in both primary and metastatic tumors, it is tempting to speculate that the activation of the STING pathway represents a relatively early mechanism in the pathogenesis of PEComas driven by TSC1/TSC2 mutations. These latter constitute a critical pathogenic event in most lesions within the PEComa spectrum, both for syndromic and sporadic tumors. Specifically, as far as extrarenal PEComas are concerned, alterations of the TSC1/TSC2 genes as well as 16p losses (mapping TSC2) have been documented in up to 80–90% uterine PEComas38,39. Similarly, TSC2 mutations have been identified in the vast majority of LAM patients40,41,42. Based on these findings, our data strongly support a pivotal role for STING in the pathogenesis of PEComas. This is especially compelling given the striking correlation between STING immunohistochemical expression and p-4EBP1 and p-S6K1 labeling, which indicate hyperactivation of the TSC-mTOR axis. Notably, among the four STING-negative tumors of our series, one was a biopsy of an 18 cm retroperitoneal mass (patient 36), which could not represent the whole tumor. Another one showed minimally split fluorescent signals of the TFE3 gene by FISH (case 29). In spite of not reaching the required threshold, such a finding may be related to other driving molecular mechanisms than conventional TSC1/TSC2 neoplasms, possibly closer to the rearrangements of the TFE3 gene described in a rarer PEComa subset11, therefore explaining the lack of STING, p-4EBP1, and p-S6K1 staining in this specific case. In this view, our results could reflect some slight differences in pathogenesis between renal and extrarenal PEComa. Namely, both groups are generally driven by mutations of the genes involved in the TSC/MTORC1 pathway, although malignant extrarenal PEComa have been more frequently accustomed to TP53, ATRX, or RB1 mutations than their renal counterparts38. Nevertheless, PEComas carrying pathogenic TFE3 translocations have been more frequently described in the kidney rather than other organs43. Thus, STING immunohistochemical staining could also be employed as a surrogate for identifying TSC1/2-mutated tumors and further act as a predictive marker because these latter are much more likely to respond to specific anti-mTOR targeted therapies than TFE3 translocated PEComas.

Moreover, our results also carry other relevant implications. From a diagnostic standpoint, our data suggest the inclusion of STING in the immunoistochemical panel employed for identifying extrarenal PEComas, along with other useful markers such as melanocytic markers (i.e., Melan-A, HMB45), cathepsin K44, and GPMNB36. Finally, regarding therapy, angiomyolipoma patients are nowadays given mTOR inhibitors to achieve tumor shrinkage. However, once these drugs are withdrawn, PEC lesions resume growth45. Molecules targeting the cGAS-STING signaling have been extensively studied in cancer46,47. Although evidence in extrarenal PEComa is currently missing and specifically designed studies are warranted, our result could open novel insights concerning the investigation and employment of STING modulators, alongside mTOR inhibitors, for the clinical management of such complex tumors.

Conclusions

In conclusion, in the present study, we have demonstrated strong and diffuse STING immunohistochemical expression in the broad majority of extrarenal PEComa from a wide range of anatomic sites. Our data advocates a critical role for the STING-mediated autophagy process in these neoplasms, opening insights into novel therapeutic strategies modulating the STING pathway in PEComas.

Methods

Patients and samples

Thirty-nine tumors from 36 patients, including samples from both primary neoplasms and distant metastases when available, were retrieved from the files of the participating institutions. In decreased order of frequency, the tumors arose from the uterus (17 cases), the lung (5 cases), the pancreas (4 cases), the retroperitoneum (4 cases), the soft tissues (3 cases), the liver (3 cases), the lymph nodes (1 case), the bowel (1 case), and the urinary bladder (1 case). The slides were reviewed by two experienced pathologists with a strong background in PEComas (A.C. and G.M.) and diagnosed as follows: 27 epithelioid PEComas, 8 clear cell sugar tumors, and 4 lymphangioleiomyomatoses. Material from one primary uterine tumor was not available (patient 2). Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) blocks were available from 20 epithelioid PEComas, 3 LAMs, 3 clear cell tumors of the lung, and 4 clear cell tumors of the pancreas. For the remaining cases, unstained slides from provided by the referring laboratories. Clinical data on a previous personal or familial history of TSC was also recorded. All procedures performed in our study involving human participants received approval (Prog. 4136CESC) and were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all the subjects.

Immunohistochemistry and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH)

Sections from tissue blocks of all tumors with available material, including four metastases from two patients, as well as unstained sections for the remaining cases, were immunohistochemically stained with STING (anti-TMEM173; clone SP338, dilution 1:150; Abcam, UK). As for p-4EBP1 (clone 236B4, dilution 1:400; Cell Signaling), and p-S6K1 (clone 49D7, dilution 1:1000; Cell Signaling) testing, it was carried out in all cases with retrieved FFPE blocks. Heat-induced antigen retrieval for STING was performed using a microwave oven and 0.01 mol/L of citrate buffer, pH 8.0, for 30 min. All samples were processed using a sensitive ‘Bond Polymer Refine’ detection system in an automated Bond immunohistochemistry instrument (Leica Biosystems, Germany). Sections incubated without the primary antibody served as a negative control. Cytoplasmic and membranous labeling for the STING was recorded by combining the percentage of positive cells (0-100%) multiplied by staining intensity (0, 1+, 2+, and 3+) to obtain an overall H-score (0-300).

FISH was carried out in all primary tumors and metastases with available material using a dual color break-apart TFE3 probe (Cytotest, USA) as previously described48.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Martignoni, G., Pea, M., Reghellin, D., Zamboni, G. & Bonetti, F. PEComas: the past, the present and the future. Virchows Arch. 452, 119–132 (2008).

Bonetti, F. et al. Clear cell (sugar) tumor of the lung is a lesion strictly related to angiomyolipoma–the concept of a family of lesions characterized by the presence of the perivascular epithelioid cells (PEC). Pathology 26, 230–236 (1994).

Stone, C. H. et al. Renal angiomyolipoma: further immunophenotypic characterization of an expanding morphologic spectrum. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 125, 751–758 (2001).

Pea, M. et al. Clear cell tumor and Angiomyolipoma. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 15, 199–202 (1991).

Tsui, W. M. et al. Hepatic angiomyolipoma: a clinicopathologic study of 30 cases and delineation of unusual morphologic variants. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 23, 34–48 (1999).

Bonetti, F. et al. Transbronchial biopsy in lymphangiomyomatosis of the lung. HMB45 for diagnosis. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 17, 1092–1102 (1993).

Pea, M., Martignoni, G., Zamboni, G. & Bonetti, F. Perivascular epithelioid cell. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 20, 1149–1153 (1996).

van Slegtenhorst, M. et al. Identification of the tuberous sclerosis gene TSC1 on chromosome 9q34. Science 277, 805–808 (1997).

Identification Characterization of the tuberous sclerosis gene on chromosome 16. Cell 75, 1305–1315 (1993).

Qin, W. et al. Angiomyolipoma have common mutations in TSC2 but no other common genetic events. PLoS One. 6, e24919 (2011).

Caliò, A. et al. TFE3-Rearranged tumors of the kidney: an emerging conundrum. Cancers (Basel) 16(19), 3396 (2024).

Rabanal-Ruiz, Y. & Otten, E. G. Korolchuk, V. I. mTORC1 as the main gateway to autophagy. Essays Biochem. 61, 565–584 (2017).

Fiorini, C. et al. LC3B and ph-S6K are both expressed in epithelioid and classic renal angiomyolipoma: A rationale tissue-based evidence for combining use of autophagic and mTOR targeted drugs. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 9, 7020–7029 (2016).

Alesi, N. et al. TSC2 regulates lysosome biogenesis via a non-canonical RAGC and TFEB-dependent mechanism. Nat. Commun. 12, 4245 (2021).

Xu, Y. et al. The cGAS-STING pathway activates transcription factor TFEB to stimulate lysosome biogenesis and pathogen clearance. Immunity 58, 309–325e6 (2025).

Lv, B. et al. A TBK1-independent primordial function of STING in lysosomal biogenesis. Mol. Cell. 84, 3979–3996e9 (2024).

Motwani, M., Pesiridis, S. & Fitzgerald, K. A. DNA sensing by the cGAS-STING pathway in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 20, 657–674 (2019).

Gui, X. et al. Autophagy induction via STING trafficking is a primordial function of the cGAS pathway. Nature 567, 262–266 (2019).

Marletta, S. et al. STING is a prognostic factor related to tumor necrosis, sarcomatoid dedifferentiation, and distant metastasis in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Virchows Arch. 483, 87–96 (2023).

Msaouel, P. et al. Comprehensive molecular characterization identifies distinct genomic and immune hallmarks of renal medullary carcinoma. Cancer Cell. 37, 720–734e13 (2020).

Marletta, S. et al. Stimulator of interferon genes (STING) immunohistochemical expression in fumarate hydratase-deficient renal cell carcinoma: biological and potential predictive implications. Virchows Arch. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00428-025-04041-5 (2025).

Caliò, A. et al. Stimulator of interferon genes (STING) immunohistochemical expression in the spectrum of perivascular epithelioid cell (PEC) lesions of the kidney. Pathology https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pathol.2020.09.025 (2021).

Gong, J. et al. The role of cGAS-STING signalling in metabolic diseases: from signalling networks to targeted intervention. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 20, 152–174 (2024).

Murayama, G. et al. Inhibition of mTOR suppresses IFNα production and the STING pathway in monocytes from systemic lupus erythematosus patients. Rheumatol. (Oxford). 59, 2992–3002 (2020).

Hasan, M. et al. Chronic innate immune activation of TBK1 suppresses mTORC1 activity and dysregulates cellular metabolism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 114, 746–751 (2017).

Alesi, N. et al. TFEB drives mTORC1 hyperactivation and kidney disease in tuberous sclerosis complex. Nat. Commun. 15, 406 (2024).

Huang, T., Sun, C., Du, F. & Chen, Z. J. STING-induced noncanonical autophagy regulates endolysosomal homeostasis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 122, e2415422122 (2025).

Mukai, M. et al. Crystalloids in Angiomyolipoma. 1. A previously unnoticed phenomenon of renal Angiomyolipoma occurring at a high frequency. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 16, 1–10 (1992).

Weeks, D. A. et al. Hepatic Angiomyolipoma with striated granules and positivity with melanoma–specific antibody (HMB-45): a report of two cases. Ultrastruct Pathol. 15, 563–571 (1991).

Chilosi, M. et al. Cathepsin-k expression in pulmonary Lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Mod. Pathol. 22, 161–166 (2009).

Caliò, A. et al. Cathepsin K expression in clear cell sugar tumor (PEComa) of the lung. Virchows Arch. 473, 55–59 (2018).

Martignoni, G. et al. Cathepsin K expression in the spectrum of perivascular epithelioid cell (PEC) lesions of the kidney. Mod. Pathol. 25, 100–111 (2012).

Zecchini, V. et al. Fumarate induces vesicular release of MtDNA to drive innate immunity. Nature 615, 499–506 (2023).

Hooftman, A. et al. Macrophage fumarate hydratase restrains mtRNA-mediated interferon production. Nature 615, 490–498 (2023).

Abdelwahab, E. M. M. et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction is a key determinant of the rare disease Lymphangioleiomyomatosis and provides a novel therapeutic target. Oncogene 38, 3093–3101 (2019).

Katsakhyan, L. et al. Uterine leiomyosarcoma associated with perivascular epithelioid cell tumor: A phenomenon of Differentiation/Dedifferentiation and evidence suggesting cell-of-Origin. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 48, 761–772 (2024).

Calabrese, C. et al. Mitochondrial translocation of TFEB regulates complex I and inflammation. EMBO Rep. 25, 704–724 (2024).

Bennett, J. A. et al. Uterine pecomas: correlation between melanocytic marker expression and TSC alterations/TFE3 fusions. Mod. Pathol. 35, 515–523 (2022).

Bennett, J. A. & Oliva, E. Perivascular epithelioid cell tumors (PEComa) of the gynecologic tract. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 60, 168–179 (2021).

Bouanzoul, M. A., Rosen, Y. & Lymphangioleiomyomatosis A review. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 149, 775–788 (2025).

Carsillo, T., Astrinidis, A. & Henske, E. Mutations in the tuberous sclerosis complex gene TSC2 are a cause of sporadic pulmonary Lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 97, 6085–6090 (2000).

Sato, T. et al. Mutation analysis of the TSC1 and TSC2 genes in Japanese patients with pulmonary Lymphangioleiomyomatosis. J. Hum. Genet. 47, 20–28 (2002).

Marletta, S. et al. SFPQ::TFE3-rearranged pecoma: differences and analogies with renal cell carcinoma carrying the same translocation. Pathol. Res. Pract. 270, 155963 (2025).

Schoolmeester, J. K. et al. Perivascular epithelioid cell neoplasm (PEComa) of the gynecologic tract: clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical characterization of 16 cases. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 38, 176–188 (2014).

Bissler, J. J. et al. Sirolimus for Angiomyolipoma in tuberous sclerosis complex or Lymphangioleiomyomatosis. N Engl. J. Med. 358, 140–151 (2008).

Woo, S. R. et al. STING-dependent cytosolic DNA sensing mediates innate immune recognition of Immunogenic tumors. Immunity 41, 830–842 (2014).

Bakhoum, S. F. et al. Chromosomal instability drives metastasis through a cytosolic DNA response. Nature 553, 467–472 (2018).

Caliò, A. et al. Comprehensive analysis of 34 MiT family translocation renal cell carcinomas and review of the literature: investigating prognostic markers and therapy targets. Pathology 52, 297–309 (2020).

Funding

This study was funded by: “Bando di ricerca finalizzata 2021 (PC: GR-2021-12374462)”.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.C, S.M., and G.M. wrote the main manuscript text. A.C. and S.M. prepared figures. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Informed consent

informed consent was obtained.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Caliò, A., Marletta, S., Pedron, S. et al. Stimulator of interferon genes immunohistochemical expression in the spectrum of extrarenal perivascular epithelioid cell lesions. Sci Rep 16, 1629 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31106-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31106-x