Abstract

University students may experience high levels of anxiety and depression, which can adversely affect their daily lives and academic performance and represent significant mental health conditions. Music therapy has been proposed as a promising noninvasive approach, but the role of specific acoustic features and their neural underpinnings remain unclear. In this study, we investigated the effects of tonality (major vs. minor) and timbre (piano vs. violin) on state anxiety. Seventy-four students were assigned to one of four intervention groups and passively listened to excerpts from Bach’s works. Anxiety was assessed with the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI-S), and neural responses were recorded with EEG. Analyses included power spectral density of beta and gamma bands, EEG-based brain source localization analyses with standardized low resolution brain electromagnetic tomography (sLORETA), and Granger causality of directional connectivity. Results showed that major-key violin music elicited the strongest anxiety reduction among anxious participants. This effect was accompanied by gamma-band alterations, with Granger causality indicating that enhanced central-to-DLPFC connectivity predicted reductions in STAI-S scores, while dACC activation appeared as a concomitant effect. Beta and gamma oscillations further exhibited complementary properties, with gamma being more sensitive to music intervention and beta reflecting inter-individual stability. These findings will provide preliminary mechanistic insights into how elemental musical features can modulate anxiety.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

State anxiety is a prevalent emotional state that, when left unmanaged, can develop into anxiety disorders. Such disorders not only impair cognitive functions such as attention and memory but also increase vulnerability to somatic conditions, including cardiovascular and immune dysfunction1,2. The economic impact of anxiety is substantial, with annual healthcare costs and productivity losses estimated to surpass $4 billion3. Therefore, early intervention for individuals experiencing anxiety is imperative to prevent its progression into a disorder. University students, with their heightened awareness of personal, interpersonal, and sociocultural differences, coupled with their openness to change, are particularly susceptible to psychological issues that can significantly impair cognitive functions such as thinking, perception, and learning4,5. Addressing anxiety among university students is thus crucial for their academic success and overall well-being.

Pharmacotherapy (PT) and cognitive–behavioral therapy (CBT) remain the most widely used and evidence-based approaches for the treatment of anxiety disorders6,7,8,9. Both modalities have demonstrated substantial clinical benefits across different populations. Nonetheless, certain challenges persist: pharmacological treatments may be accompanied by side effects, particularly with long-term use, while CBT can show limited response in some individuals and relapse rates after discontinuation are not uncommon10,11,12. These limitations do not diminish the importance of PT and CBT, but they highlight the value of exploring complementary strategies that might provide additional options for specific groups of patients.

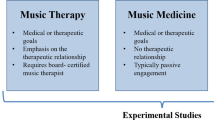

Music therapy (MT) is typically delivered by credentialed professionals within a therapeutic relationship in clinical practice, either in one-to-one or group settings over multiple sessions13. Such interventions often employ familiar or specially designed music and have shown efficacy in reducing anxiety, depression, and pain14,15. However, few studies have focused on younger populations, and the specific acoustic features and neural mechanisms underlying these effects remain insufficiently explored16,17. These gaps highlight the need for experimental studies that systematically examine how specific musical features influence anxiety, particularly in younger populations.

A wide range of musical features have been studied in various research contexts. Bach’s classical music is often used because of its consistent style and therapeutic effectiveness18. Tonality plays a pivotal role in conveying emotions, with major and minor modes typically associated with feelings of happiness and sadness, respectively, due to their characteristic intervals19,20. The distinct timbres of the piano and violin also contribute to their differential effects on anxiety. The piano offers a balanced and wide harmonic spectrum, whereas the violin produces rich higher harmonics through bow friction21. On the basis of these findings, we have hypothesized that a specific musical element may be more effective in influencing anxiety states.

Emotion regulation of anxiety is supported by a distributed cortical network, including the prefrontal cortex (PFC), anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), insula, and orbitofrontal cortex (OFC). Within this network, the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) is critically involved in cognitive control of emotion22,23, the ventrolateral and dorsomedial PFC (VLPFC, dmPFC) contribute to emotion inhibition and conflict processing24,25, the dorsal ACC (dACC) monitors affective conflict and anxiety26,27,28, while the insula and OFC are central to interoception and affective evaluation29,30,31. Although these regions collectively shape emotional responses, the specific cortical substrates through which music exerts anxiolytic effects remain poorly understood.

The present study investigated how different musical instruments (piano vs. violin) and tonalities (major vs. minor) influence anxiety relief in university students. Participants listened passively to pre-selected excerpts from Bach Werke Verzeichnis (BWV), while subjective anxiety was assessed using the STAI-S and neural responses were recorded with EEG. Analyses included spectral power of beta and gamma bands, brain source localization using standardized low resolution brain electromagnetic tomography (sLORETA), and acoustic characterization of the music. To further probe mechanisms, we applied Granger causality and ANCOVA, providing an integrated evaluation of how specific musical elements modulate anxiety at both behavioral and neural levels. Taken together, these approaches offer an initial, controlled characterization of associations between specific musical features and anxiety-related measures in young adults and delineate hypotheses for future confirmatory studies.

Methods and materials

Participants

All participants provided written informed consent, which was approved by the Ethics Committee of Biology and Medicine at Northwestern Polytechnical University in China. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. A total of 74 undergraduate and graduate students from Northwestern Polytechnical University in China were recruited through advertisements that invited students who perceived themselves as recently experiencing anxiety symptoms. All volunteers completed the Self-Rating Anxiety Scale32 to provide a standardized assessment of anxiety severity, with scores ≥ 50 were classified into the “anxiety group,” while those scoring < 50 were assigned to the “control group. Additional inclusion criteria were the absence of any other psychiatric disorders or familial psychiatric history, and no prior professional musical training. All the participants were subsequently randomly assigned to one of four groups (PA, PI, VA, VI), where "P" represents the piano group, "V" signifies the violin group, "A" denotes the major key, and "I" indicates the minor key, to receive various musical interventions. In total, the anxiety group included 26 females and 12 males (with a sample size: PA: 9, PI: 11, VA: 11 VI: 8), and the control group included 18 females and 12 males (PA: 8, PI: 8, VA: 9, VI: 9) (Table 1).

Stimuli

The musical intervention materials utilized in the experiment included meticulously selected and edited instrumental music excerpts sourced from Bach’s Works (BWV). As illustrated in Fig. 1a, the entire selection and processing procedure encompassed six distinct stages: the establishment of a comprehensive music database, the categorization of musical materials, selection on the basis of tempo, the editing of segments, splicing and transitions, and final completion.

To minimize subjective emotional fluctuations and isolate the effects of specific musical elements (timbre: piano vs. violin; tonality: major vs. minor), we constructed a music database from Bach’s works (BWV 772–994, 1001–1040), which are characterized by relatively uniform structures and limited dramatic progressions. The pieces were first categorized into four groups (PA, PI, VA, VI) and filtered to tempos of 60–120 beats per minute (BPM). From each group, five excerpts of approximately 1–2 min were chosen according to three criteria: (i) comparable phrase length, (ii) smooth stylistic continuity when concatenated, and (iii) avoidance of highly familiar pieces. Instead of using complete compositions, short phrases encompassing cadences were extracted and spliced in random order, producing final tracks that preserved tonal and timbral properties while reducing the influence of large-scale emotional trajectories (Table 2). The volume of all experimental tracks will be fixed to the same level.

Experimental design

STAI-S

In this study, the State Anxiety Subscale of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI-S) was employed to explore the participants’ subjective feelings and anxious state. Specifically, the STAI-S was utilized exclusively to assess and compare short-term anxiety states, without addressing the more enduring concept of "trait anxiety."

The subscale uses a 4-point Likert scale, where participants are required to rate the intensity of their feelings on a scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 4 (very much so). The total score on the subscale can range from 20 to 80, with higher scores indicating a greater level of state anxiety. A score of 40 or above is generally considered indicative of high anxiety levels.

Experimental process

During the state anxiety intervention phase, including PA, PI, VA, and VI, participants were instructed to keep their phones on silent mode throughout the experiment to ensure a comfortable and uninterrupted experience. Furthermore, the experiment was conducted in a quiet, well-lit, and temperature-controlled (20–22 °C) music therapy room with the use of headphones.

The entire experiment comprised five phases: an initial 5-min resting period with eyes closed, an 8-min state anxiety intervention, and a subsequent 5-min resting period with eyes closed. Participants completed the State Anxiety Subscale of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI-S) before (BF) and after (AF) the experiment, as illustrated in Fig. 1b. Resting-state EEG segments from the BF and AF periods were collected for further analysis. Thus, each participant served as his/her own baseline control, with comparisons made between pre- and post-intervention resting states.

EEG data acquisition

EEG data were recorded from the subjects during both the resting state and the intervention state, with instructions to remain still throughout the recording process. The experimental data were collected via a 32-channel EEG system, model 8102, manufactured by Delica Medical Equipment Co., Ltd. in Shenzhen, China (Shenzhen Delica). Wet electrodes were utilized for the recording, with FCz serving as the reference electrode for online recording. The electrode cap layout adhered strictly to the international 10–20 system standard, and the sampling rate was set at 1000 Hz. Throughout the experiment, the impedance of all electrodes was maintained below 5 kΩ to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the collected data.

Data analysis

Experimental tracks

To ascertain the distinctions in spectral distribution between the timbre of a piano and a violin, the experimental audio was analyzed spectrographically via the fast Fourier transform (FFT) method, which specifically targeted the harmonic waveforms (Eq. 1):

where \(X\left[t\right]\) is the discrete audio signal at time point \(t\), N is the total number of sampled points, \(f\) denotes the frequency index, and \(X\left[f\right]\) is the complex spectral coefficient at frequency \(f\). The fundamental frequency was identified as the \(f\) at which \(\left|X\left[f\right]\right|\) reached its maximum, and the corresponding harmonic magnitudes were subsequently calculated. For clarity, spectral magnitudes were averaged in 10 Hz bins and expressed in decibels (dB) for comparison. These spectral representations allowed us to compare the distribution of energy across frequencies between piano and violin tracks. Ultimately, the spectral graphs were generated via Matplotlib.

The roughness of each experimental audio piece was determined via MATLAB 9.13.0, where the audio signal was segmented into frames. The formula for calculating roughness, which is based on a psychoacoustic model proposed by Daniel and Weber33, is provided below (Eq. 2):

In this formula, R represents the perceived roughness of the entire audio signal (unit: asper); \({z}_{i}\) denotes the Bark-scale position of the i-th frequency band; \(g({z}_{i})\) is the corresponding weighting function related to the bark scale34,\({ m}_{i}^{*}\) is the effective modulation depth of band I; \({k}_{i}\) and \({k}_{i-2}\) represent specific loudness values used to capture inter-band interactions. The product term captures how modulation depth and loudness interact across adjacent bands, while the square ensures that contributions grow with energy. By summing across all critical bands, the model approximates how beating and fast amplitude fluctuations in the spectrum are integrated into the global percept of roughness.

Preprocessing EEG data

EEG data were preprocessed using the EEGLAB toolbox35 implemented in MATLAB 9.13.0. A common average reference (CAR) method was applied, and a finite impulse response (FIR) filter was used to perform bandpass filtering between 0.5 and 80 Hz and notch filtering between 48 and 52 Hz. Additionally, the data were down-sampled from 1000 to 500 Hz to improve computational efficiency and reduce data size. Artifact rejection was performed with the ICLabel plugin36, which employs a pre-trained neural network classifier to assign probability values across seven categories (Brain, Muscle, Eye, Heart, Line noise, Channel noise, and Other). Independent components (ICs) with ≥ 80% probability of being Eye or Muscle artifacts were removed from the dataset. On average, approximately 0–3 ICs were rejected per participant (≈8–12% of total components), while the majority of the data (> 85%) was retained after preprocessing (Fig. 1c).

EEG data—spectral density value analysis

Analyses focused on beta (14–30 Hz) and gamma (30–80 Hz) activity at prefrontal (F3/F4) and central (C3/C4) electrodes, as these sites are commonly employed in studies of emotion regulation and anxiety-related brain activity. The continuous wavelet transform (CWT) was employed to derive the absolute power spectral values across all channels for all the subjects (Fig. 1d). The wavelet basis function can be mathematically expressed as follows (Eq. 3):

where \(a\) is the scaling factor controlling frequency resolution, \(b\) is the translation parameter determining time localization, and \(t\) is the time variable. However, defining the wavelet basis alone does not yet describe how the EEG signal is analyzed. Therefore, the actual CWT is obtained by projecting the signal \(x(t\)) onto this family of basis functions (Eq. 4):

This step extends the simple definition in (3) into a full transformation, enabling us to track how spectral power evolves across time. In this study, we applied the CWT to extract absolute power during the S1, T, and S2 periods, focusing on beta (14–30 Hz), and gamma (30–80 Hz) bands (Fig. 1d).

EEG data—brain source localization analysis

sLORETA-KEY is a commonly used algorithm for estimating cortical sources from low-density EEG, providing standardized solutions that reduce localization bias though with limited spatial resolution37. In this study, we applied sLORETA to resting-state EEG recordings before and after each intervention to examine beta- and gamma-band activity. Signals were truncated to a 1-s epoch (150–151 s) from the middle of each resting period to avoid transitional artifacts and reduce computational load. After down-sampling to 500 Hz, the central 250–350 sampling points were analyzed. Pre–post differences were tested using paired-sample t-tests with permutation-derived thresholds, where voxels exceeding the permutation-derived critical t threshold were considered significant. Significant voxels were mapped to MNI coordinates and reported by Brodmann areas (BA).

Granger causality analysis

To assess the directional interactions between cortical regions, we applied Granger Causality (GC) analysis38 to pre- and post-intervention EEG data. Directed functional connectivity was estimated in both the beta (12–30 Hz) and gamma (30–80 Hz) frequency bands. Specifically, GC analysis was performed at the electrode level, focusing on prefrontal (F3/F4; approximating DLPFC) and central (C3/C4) sites. Due to the medial location of the dACC and the limited spatial resolution of the 32/64-channel EEG montage, dACC signals could not be directly isolated for GC. From these estimates, three composite metrics were derived at the subject level: (i) DLPFC-to-Central, reflecting top-down prefrontal influences; (ii) Central-to-DLPFC, reflecting bottom-up cortical inputs to the DLPFC; and (iii) a Direction Index (DI), defined as the normalized difference between the two directions.

To examine the relationship with behavioral outcomes, GC indices were correlated with post-intervention STAI scores using both Spearman and Pearson correlation tests. In addition, multiple regression models (Y ~ X + STAIpre + group + music) were fitted to predict post-intervention STAI from GC metrics while controlling baseline anxiety, experimental group, and music condition. False discovery rate (FDR) correction was applied across tests to control for multiple comparisons.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses included both within-subject and between-group comparisons. Within-subject changes (baseline vs. post-intervention resting) were assessed using paired t-tests on STAI scores and EEG power spectral values. Between-group effects of Group (Anxiety vs. Control), Condition (PA, PI, VA, VI), and their interaction were tested using two-way ANOVA on percentage decreases (Δ%). When the interaction was significant, simple-effects analyses were conducted; when normality or homogeneity assumptions were violated, Welch’s ANOVA or non-parametric tests (Kruskal–Wallis with Dunn’s post hoc = 6) were used. Assumptions were checked using Shapiro–Wilk and Levene’s tests, complemented by visual inspection of residual distributions.

For source localization, sLORETA results were analyzed with paired t-tests and 5,000-permutation nonparametric tests, providing family-wise error rate (FWER) correction across 6239 voxels. Outliers were defined as observations with absolute z-scores > 3. To account for gender imbalance, an ANCOVA was performed with post-intervention scores as the dependent variable, music condition as the independent variable, and gender together with pre-intervention scores as covariates. All analyses were performed in GraphPad Prism (version 10.1.2). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Effects of music interventions on state anxiety and EEG power spectra

To provide a preliminary reference for the subjective effectiveness of the interventions, STAI-S scores were collected before and after each session (Fig. 2a, b). Across both anxiety (PI: t(10) = 5.34, p = 0.0003, Cohen’s dz = 1.61; VA: t(10) = 3.91, p = 0.0029, Cohen’s dz = 1.18; VI: t(6) = 5.00, p = 0.0025, Cohen’s dz = 1.89) and nonanxiety participants (PA: t(6) = 4.68, p = 0.0034, Cohen’s dz = 1.77; PI: t(6) = 4.12, p = 0.0062, Cohen’s dz = 1.56; VA: t(6) = 6.25, p = 0.0008, Cohen’s dz = 2.36; VI: t(8) = 7.21, p < 0.0001, Cohen’s dz = 2.40), the scores showed a general downward trend .

Effects of Music Interventions on STAI-S Scores and Brain Wave Power Density in Anxiety and Control Groups. (a, b) Changes in the STAI-S scores before and after the intervention in the anxiety group (a) and control group (b). (c, d) Power density of gamma waves in the anxiety group (c) and control group (d). (e, f) Power density of beta waves in the anxiety group (e) and control group (f). * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001, **** P < 0.0001. Abbreviations: PA, piano major; PI, piano minor; VA, violin major; VI, violin minor; P, piano; V, violin; A, major; I, minor; BF, before; AF, after. (n = 8–11).

To complement the questionnaire data, we further examined EEG spectral power of beta and gamma waves (Fig. 2c–f). In the anxiety group, one-way ANOVA revealed a marginal main effect of music condition on beta power (F(3,93) = 2.72, P = 0.049, R2 = 0.081), with post hoc tests indicating decreases in the PA, VA, and VI conditions. Gamma power showed a more robust effect (F(3,140) = 2.59, P = 0.0003, R2 = 0.12), with the VA condition producing the most pronounced reduction compared with the other groups. In the control group, significant main effects were also observed for both beta (F(3,93) = 2.72, P = 0.049, R2 = 0.081) and gamma power (F(3,124) = 2.41, P < 0.02, R2 = 0.076). Post hoc analyses indicated that PI and VI conditions were associated with significant gamma reductions relative to the other conditions (Fig. 2c–f). Importantly, after adjusting for gender and pre-intervention scores in ANCOVA, the main effects of music condition remained unchanged, and no significant effect of gender was observed (F(1,35) = 3.38, p = 0.075, partial η2 = 0.001).

Differential effects of instrument and tonality on anxiety-related measures

To delve deeper into whether a single factor was responsible for the significant changes observed in the two-factor (timbre and tonality) groups, we isolated the four elements P, V, A, and I (where P = PA + PI, V = VA + VI, A = PA + VA, and I = PI + VI) and conducted a two-way ANOVA of EEG beta- and gamma-band percentage decreases (Δ%) (Fig. 3a, b). A significant Group × Condition interaction was reported (F = 4.343 and P = 0.00488, η2 = 0.25), with no significant main effects. Notably, in the Anxiety group, there was a significant anxiety-reduction effect caused by major music (t(147) = 2.19, P = 0.030, Cohen’s d = 0.36) and violin music (t(130) = 2.92, P = 0.0041, Cohen’s d = 0.51). Conversely, in the control group, minor music (A: P = 0.0055; B: P = 0.0041) and piano music (t(141) = 2.25, P = 0.026, Cohen’s d = 0.38) led to a significant reduction in gamma waves (Table 3 & Fig. 3). These findings suggest that major key violin music significantly reduces anxiety in individuals with high anxiety levels.

Changes in the spectral density of separated factors P, V, A, and I before and after music intervention in beta-brain waves (a) and gamma-brain waves (b). * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001, **** P < 0.0001. P = PA + PI; V = VA + VI; A = PA + VA; I = PI + VI. PA, piano major; PI, piano minor; VA, violin major; VI, violin minor; P, piano; V, violin; A, major; I, minor.

Acoustic characteristics of violin and piano music: frequency density and roughness

To gain a deeper understanding of how different musical elements influence anxiety levels, we employed the fast Fourier transform (FFT) to analyze the harmonic spectrum of each experimental track. Distinct waveform differences between the piano group (Fig. 4a and b) and the violin group (Fig. 4c and d) were evident in the highlighted squares based on the frequency density of high-frequency harmonics. To emphasize the significance of these differences, we conducted a statistical analysis of the roughness and power density of frequency on the experimental tracks. Notably, the violin group presented significantly greater roughness (P < 0.0001, Hedges’ g = 1.17, 95% CI [0.68, 1.65]) and greater frequency power density (P < 0.0001, Hedges’ g = 0.96, 95% CI [0.50, 1.41]) than did the piano group, suggesting that the acoustic characteristics of these two instruments in the high-frequency range are markedly distinct (Fig. 4e and f).

Spectral characteristics of experimental tracks. (a–d) Spectrograms of the PA (a), PI (b), VA (c), and VI (d) experimental tracks averaged every 10 Hz. (e–f) Raincloud plots depicting power density of frequency (e) and roughness (f) between piano and violin pieces in the 4000–5000 Hz range. Each plot shows the distribution, boxplot, and all individual data points. Violin music exhibited significantly greater power density (Hedges’ g = 0.96) and roughness (Hedges’ g = 1.17) than piano music. Negative values occasionally observed in kernel density estimation were artifacts of smoothing; raw data points confirmed all measurements were non-negative.

Cortical activity patterns associated with major violin music

Given the anxiety-reducing effects of major violin music, we next examined pre–post resting-state changes in cortical current density using sLORETA. Permutation-corrected analyses (SnPM, 5,000 randomizations, family-wise error corrected) demonstrated that only the Major (A) and Violin (V) intervention in the gamma band in Anxiety group yielded significant pre–post changes (A: t = 3.40, P = 0.036; V: t = 2.92, P = 0.045). Significant clusters were localized to the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, and dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (BA 9, 32) intervened by Violin factor, and similarly, to the anterior cingulate cortex (BA32) intervened by the Major factor (Table 4 and Fig. 5a and b). Nevertheless, to provide a complete overview of the data, the regions showing the strongest uncorrected changes are reported descriptively in Table 4. These included, for example, the ventral and dorsal posterior cingulate cortices and anterior prefrontal cortex (BA 23, 31, 10) in the control group, the insular cortex, inferior frontal gyrus, and temporal pole (BA 13, 47, 38) following piano interventions in the anxiety group, and the supramarginal gyrus and primary somatosensory cortex (BA 40, 2) under minor-key interventions in the anxiety group.

sLORETA and Granger causality results. (a-b) XYZ sLORETA slices of the average change in gamma waves in the anxiety group following intervention with VA music (a) and PI music (b); red voxels indicate regions with greater activation. Coordinates correspond to the most prominently activated locations. (c) Scatter plot showing the relationship between Central-to-DLPFC connectivity (GC values) and post-intervention STAI scores in the gamma band (ρ = –0.26, p = 0.029). (d) Bar plot illustrating multiple regression results, where Central-to-DLPFC connectivity in the gamma band significantly predicted post-intervention STAI scores after controlling for baseline STAI, group, and music condition (R2 ≈ 0.41). * p < 0.05. Abbreviations: PI, piano minor; VA, violin major; DLPFC, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex; STAI, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory.

Granger causality between central cortex and DLPFC predicts anxiety reduction

GC analysis was conducted to examine directional connectivity between central cortical sites and the DLPFC in the beta and gamma frequency bands. Central-to-DLPFC connectivity showed a significant negative correlation with post-intervention STAI scores in the gamma band (ρ = –0.26, p = 0.029; Fig. 5c). Multiple regression models further confirmed that Central-to-DLPFC connectivity was a significant predictor of post-intervention STAI scores after controlling for baseline STAI, group, and music condition (β < 0, p < 0.05, R2 ≈ 0.41; Fig. 5d).

Discussion

Music therapy has been increasingly recognized as a promising noninvasive approach for anxiety relief, yet the diversity of musical attributes and the complexity of neural mechanisms present challenges for systematic investigation. In this study, we investigated the independent effects of tonality (major v.s. minor) and timbre (piano v.s violin) on state anxiety, integrating behavioral outcomes with EEG spectral and source localization analyses. Among anxious individuals, major-key violin music showed the most pronounced anxiolytic effect, which was accompanied by gamma-band alterations and engagement of prefrontal circuits. While the observed dACC activation may represent a concomitant effect of anxiety reduction, Granger causality analysis provided stronger evidence that enhanced central-to-DLPFC connectivity in the gamma band was functionally linked to reductions in post-intervention STAI scores. Together, these results provide preliminary evidence that specific acoustic properties of music can engage prefrontal regulatory pathways, offering a cautious step toward clarifying how elemental musical features may influence anxiety.

To ensure that the effects of specific musical elements could be examined under controlled conditions, we carefully standardized the music materials used in this study. We selected music by Bach, as Baroque compositions are known for their relatively uniform style and are less subject to the expressive fluctuations seen in other musical periods18. Additionally, we constructed the experimental track by splicing together several ordinary musical phrases rather than using complete pieces, which was done to avoid the emotional progression, climax, and structural development that a full composition typically contains39. Finally, the tempos to a specific BPM were constrained within the spontaneous tempo of human physiological rhythms (e.g., heart rate, locomotion) to minimize the physiological effects of rhythm on participants40.

Music therapy has shown promise across various clinical settings14. To validate its anxiety-reducing effects, this study recorded participants’ STAI-S score data and EEG data before and after music interventions. On average, participants showed a significant reduction in STAI-S scores after the intervention. (Fig. 2), indicating that the selected music database, which is characterized by its classical style and physiological-fitting rhythm, can generally possess anxiety-reducing properties, which aligns with prior research41,42. However, since each condition (e.g., PA, VI) inherently combines two musical features, the current analysis cannot disentangle whether the observed changes are primarily attributable to timbre, tonality, or their interaction. To clarify the contribution of these individual elements, we therefore decomposed the conditions into their constitutive factors (P, V, A, I) and reanalyzed the data using percentage decreases as the outcome measure. This approach allows a more precise evaluation of how timbre and tonality independently and jointly shape neural responses associated with anxiety.

Tonality, a fundamental aspect of music, plays a pivotal role in emotional communication19, with major and minor keys often associated with happiness and sadness, respectively. Therefore, we compared Major (A) element and Minor (I) element to assess the impact of musical emotions on anxiety. Our analysis revealed that, in the control group, minor key music led to a greater reduction in anxiety than major key music. Conversely, anxious individuals showed greater anxiety reduction with major key music, experiencing a more pronounced anxiety-relieving effect (Fig. 3a). This finding is consistent with the Mood Congruence Hypothesis43, which posits that individuals tend to preferentially select external stimuli congruent with their current emotional state. In terms of the psychological mechanism of this framework, Yoon et al.44 further discussed the motivational basis of the Mood Congruence Hypothesis, suggesting that the essence of this phenomenon lies in emotion regulation needs guiding stimulus selection. For example, individuals experiencing sadness may choose low-energy music (i.e., sad music) to alleviate sadness and seek calmness, thereby achieving emotional soothing. This introduces the concept of the energy dimension, which refers to the arousal level of music. Anxiety is a high-energy emotion and major key music is considered high-energy because of its capacity to evoke heightened arousal45,46,47. We speculate that the normal group showed greater anxiety reduction when listening to minor key music, possibly because its relatively low-energy characteristics induce calmness. In contrast, anxious individuals, with their high-energy emotional state, may have been more easily engaged or distracted by high-energy music such as major key pieces, which could partly explain their anxiety reduction. Besides distraction, another plausible mechanism is the induction of positive mood by music, which has been well documented in previous research45,48,49. Such mood induction effects could have contributed to the anxiety reduction observed in our study.

Timbre stands as a pivotal characteristic in the realm of music. To further examine how different timbres influence emotions, the impact of Piano (P) and Violin (V) music on anxiety relief was investigated. Intriguingly, the results revealed a discernible difference in the effects of instrument type between the anxious cohort and the normal control group. Specifically, violin music had a more potent anxiety-alleviating effect on the anxious group, whereas piano music was more efficacious for the control group, as illustrated in Fig. 3b. The soothing effect of piano music on emotions and its stress-relieving capabilities have been widely reported50,51,52,53,54. Conversely, the stronger anxiety-reducing effect of violin music among anxious individuals presents an unexpected twist.

To better understand the factors driving these divergent outcomes, we conducted a spectral analysis of the experimental tracks. The findings revealed that violin music exhibited higher frequency density and greater roughness as shown in Fig. 4. Notably, higher spectral density increases the likelihood of closely spaced partials, which interact through beating and thereby give rise to auditory roughness55,56. This provides a mechanistic link between the observed spectral properties of violin music and its elevated roughness levels. Interestingly, many studies have reported that auditory roughness is closely associated with aversive perception57,58,59,60,61,62. However, it should be noted that, instruments have complex time–frequency structures, but their primary design is not intended to trigger threat-related responses. As a result, string instruments with higher levels of roughness do not elicit strong aversive reactions57. Therefore, the music used in this study can disregard the “unpleasantness” typically associated with roughness and instead focus on the direct impact of “roughness” itself. From a cognitive perspective, Taffou et al.63 demonstrated that auditory roughness triggers defensive responses by enlarging the peripersonal space and priming the organism for threat-related behaviors. The so-called “defensive” responses to rough sounds can essentially be interpreted as heightened attentional allocation to these stimuli, which are biologically encoded as salient threat cues and exert strong attentional capture effects57. We therefore propose that auditory roughness may serve as a mechanism of distraction and attentional redirection, thereby contributing to the alleviation of anxiety symptoms.

To deeply explore the neurobehavioral relevance of rough music, we conducted source localization analyses on the EEG S1 and S2 data. The sLORETA results in gamma wave emphasized that interventions involving major keys and violin timbre produced significant cortical activation in the anxiety group, specifically engaging Brodmann areas 9 and 32 (Table 4 and Fig. 5a and b). This finding extends the anxiolytic effect of major violin music to the level of neural responses. BA 9 and 32 are located in the frontal lobe, where the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC, BA 32) has been implicated in monitoring affective conflict and anxiety26,27, and the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC, BA 9) plays a central role in top-down emotion regulation by inhibiting limbic overactivation and reallocating attention toward external cues64,65. From a broader neural perspective on auditory roughness, Arnal et al.57 demonstrated that rough sounds strongly engage the amygdala, while subsequent work showed a cascade of responses—initial startle activity in the auditory cortex (high-gamma synchronization), followed by limbic activation (insula, amygdala), and finally recruitment of parietal and prefrontal cortices responsible for regulation and attentional control58. Taken together, the observed dACC and DLPFC activation in our sLORETA analyses aligns with established roughness-related cortical pathways, suggesting that the distinctive roughness of major violin music may recruit prefrontal circuits to support its anxiolytic effects.

To further verify whether the activation of the dACC and DLPFC was driven by music intervention rather than representing a concomitant phenomenon, we performed Granger causality (GC) analysis. Because the dACC is an intermediate structure that cannot be directly isolated with 32-channel EEG, its results were considered only as supportive evidence of prefrontal involvement based on source localization. Focusing on the central cortical sites and the DLPFC, the GC analysis revealed that in the gamma band, the Central-to-DLPFC directional connectivity was significantly negatively correlated with post-intervention STAI scores and significantly predicted anxiety reduction in regression models (Fig. 5C). To further verify the robustness of this relationship, multiple regression analyses were conducted controlling for baseline STAI, group, and music condition, which confirmed that Central → DLPFC connectivity significantly predicted anxiety reduction (Fig. 5D). These findings strengthen the interpretation that DLPFC engagement during VA intervention is not merely epiphenomenal but functionally linked to anxiety relief through enhanced bottom-up input. This aligns with classical models highlighting the role of the ACC–PFC circuit in emotion regulation66, and with more recent reviews emphasizing the critical involvement of DLPFC in controlling anxious states via its executive and attention-control functions67.

Both beta and gamma bands obtained a comprehensive picture of oscillatory responses to music intervention (Fig. 2 to Fig. 5) but two rhythms exhibited distinct patterns: beta activity showed only marginal modulation by music condition, whereas gamma activity displayed more robust changes, particularly in the anxiety group. Granger causality analysis further suggested that gamma-band connectivity was more strongly associated with anxiety reduction, while beta effects were weaker and nonsignificant. This is consistent with previous evidence that gamma oscillations provide a sensitive index of emotion-cognition interactions68 and may reflect rapid information transfer within the anterior cingulate-prefrontal circuit (Amit26,27). By contrast, beta activity appeared to capture more general arousal- and attention-related processes. Interestingly, when baseline covariates were considered in ANCOVA, beta effects became more pronounced, suggesting that beta oscillations may provide a stable marker of inter-individual variability. Taken together, our findings indicate that gamma oscillations are more sensitive to music-induced modulation, whereas beta oscillations contribute complementary stability, highlighting the value of considering both bands for a more complete understanding of neural mechanisms underlying music-based anxiety relief.

Our paradigm differs from conventional clinical music therapy, where therapists typically use complete pieces with intact emotional trajectories to guide clients. In contrast, we intentionally minimized expressive elements to isolate the effects of specific acoustic features such as tonality and timbre under controlled conditions. Although this reductionist design cannot reproduce the ecological richness of therapist–client interactions, it provides useful preliminary insights. Understanding how isolated musical elements modulate neural activity may help refine therapeutic music selection and, in the future, contribute to AI-assisting tools that complement therapist-guided interventions with a deeper mechanistic basis.

Limitations

To isolate the effects of specific acoustic features, we constrained tempo and selected short Baroque phrases for splicing, thereby minimizing large-scale emotional trajectories. While this design provided a controlled framework, it may also have weakened the ecological validity of the music, and the emotional valence of the final tracks was not independently validated. Moreover, subtle tempo differences and the lack of perfect key matching across groups could have introduced additional bias, and all excerpts were performed by only three musicians, leaving open the possibility of performer-specific effects. Future studies should therefore consider larger and standardized music libraries, as well as objective validation of musical features, to enhance reproducibility.

Another limitation concerns both the EEG data acquisition and sample size. Source localization was performed with a 32-channel EEG system, which inherently provides lower spatial resolution than high-density arrays; hence, the reported cortical activations should be interpreted with caution. Similarly, our Granger causality analyses were limited to electrode-level data and behavioral correlations, rather than allowing mechanistic inference about interregional connectivity. In addition, the relatively small sample size within each intervention subgroup reduced statistical power and may limit generalizability. Future work should aim to replicate these findings with larger samples, high-density or multimodal neuroimaging (e.g., fMRI–EEG), and more advanced causal modeling approaches such as dynamic causal modeling (DCM).

Conclusion

In summary, this study systematically examined how tonality and timbre shape the anxiolytic effects of music in university students. Major-key violin music emerged as particularly effective in reducing state anxiety, accompanied by gamma-band modulation and engagement of prefrontal circuits. While dACC activation may represent a concomitant effect, Granger causality analyses indicated that enhanced central-to-DLPFC connectivity was functionally linked to anxiety relief. Moreover, gamma brain wave provided a more sensitive marker of music-induced modulation, whereas beta offered complementary stability when individual variability was accounted for. Though using decontextualized stimuli, this approach decodes hierarchical music-emotion circuitry interactions, advancing targeted acoustic therapy development.

Data availability

The datasets utilized and examined in this study can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Reiche, E. M. V., Nunes, S. O. V. & Morimoto, H. K. Stress, depression, the immune system, and cancer. Lancet Oncol. 5(10), 617–625 (2004).

Szuhany, K. L. & Simon, N. M. Anxiety disorders: A review. JAMA 328(24), 2431–2445. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2022.22744 (2022).

Harder, H. G., Wagner, S., & Rash, J. Mental Illness in the Workplace: Psychological Disability Management. (Routledge, 2016).

Endler, N. S. & Kocovski, N. L. State and trait anxiety revisited. J. Anxiety Disord. 15(3), 231–245 (2001).

Kocsis, R. N. Book review: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: Fifth edition (DSM-5). Int. J. Offender Ther. Comp. Criminol. 57(12), 1546–1548. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624x13511040(2013).

Agarwal, S. D. & Landon, B. E. Patterns in outpatient benzodiazepine prescribing in the United States. JAMA Netw. Open 2(1), e187399–e187399 (2019).

Chessick, C. A., Allen, M. H., Thase, M. E., Batista Miralha da Cunha, A. A., Kapczinski, F., Silva de Lima, M., dos Santos Souza, J. J., & Group, C. C. M. D. Azapirones for generalized anxiety disorder. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015(6) (1996).

Hans, E. & Hiller, W. A meta-analysis of nonrandomized effectiveness studies on outpatient cognitive behavioral therapy for adult anxiety disorders. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 33(8), 954–964 (2013).

Watts, S. E., Turnell, A., Kladnitski, N., Newby, J. M. & Andrews, G. Treatment-as-usual (TAU) is anything but usual: A meta-analysis of CBT versus TAU for anxiety and depression. J. Affect. Disord. 175, 152–167 (2015).

Ginsburg, G. S. et al. Naturalistic follow-up of youths treated for pediatric anxiety disorders. JAMA Psychiat. 71(3), 310–318 (2014).

Swain, J., Hancock, K., Hainsworth, C. & Bowman, J. Acceptance and commitment therapy in the treatment of anxiety: A systematic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 33(8), 965–978 (2013).

Weich, S., Pearce, H. L., Croft, P., Singh, S., Crome, I., Bashford, J., & Frisher, M. Effect of anxiolytic and hypnotic drug prescriptions on mortality hazards: Retrospective cohort study. Bmj 348 (2014).

Bradt, J., Dileo, C., Magill, L., & Teague, A. Music interventions for improving psychological and physical outcomes in cancer patients. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 8 (2016).

Tang, H. et al. The efficacy of music therapy to relieve pain, anxiety, and promote sleep quality, in patients with small cell lung cancer receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Support. Care Cancer 29(12), 7299–7306 (2021).

Zhu, X. et al. Resting state connectivity predictors of symptom change during gaze-contingent music reward therapy of social anxiety disorder. Psychol. Med. 53(7), 3115–3123 (2023).

Lu, G. et al. Effects of music therapy on anxiety: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Psychiatry Res. 304, 114137 (2021).

Nilsson, U. The anxiety-and pain-reducing effects of music interventions: A systematic review. AORN J. 87(4), 780–807 (2008).

Sharda, N. et al. Bach to the basics: Implementation and impact of a postoperative, inpatient personalized music program for older adults. J. Perianesth. Nurs. 34(2), 347–353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jopan.2018.05.006 (2019).

Balkwill, L.-L. & Thompson, W. F. A cross-cultural investigation of the perception of emotion in music: Psychophysical and cultural cues. Music. Percept. 17(1), 43–64 (1999).

Nieminen, S., Istók, E., Brattico, E. & Tervaniemi, M. The development of the aesthetic experience of music: Preference, emotions, and beauty. Music Sci. 16(3), 372–391 (2012).

Sethares, W. A. Tuning, Timbre, Spectrum, Scale. (Springer, 2005).

Buhle, J. T. et al. Cognitive reappraisal of emotion: a meta-analysis of human neuroimaging studies. Cereb. Cortex 24(11), 2981–2990 (2014).

Ochsner, K. N., Silvers, J. A. & Buhle, J. T. Functional imaging studies of emotion regulation: A synthetic review and evolving model of the cognitive control of emotion. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1251(1), E1–E24 (2012).

Kohn, N. et al. Neural network of cognitive emotion regulation—An ALE meta-analysis and MACM analysis. Neuroimage 87, 345–355 (2014).

Kuzmanovic, B., Rigoux, L. & Tittgemeyer, M. Influence of vmPFC on dmPFC predicts valence-guided belief formation. J. Neurosci. 38(37), 7996–8010 (2018).

Etkin, A., Egner, T. & Kalisch, R. Emotional processing in anterior cingulate and medial prefrontal cortex. Trends Cogn. Sci. 15(2), 85–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2010.11.004 (2011).

Etkin, A., Egner, T. & Kalisch, R. Emotional processing in anterior cingulate and medial prefrontal cortex. Trends Cogn. Sci. 15(2), 85–93 (2011).

Fox, M. D., Buckner, R. L., White, M. P., Greicius, M. D. & Pascual-Leone, A. Efficacy of transcranial magnetic stimulation targets for depression is related to intrinsic functional connectivity with the subgenual cingulate. Biol. Psychiatry 72(7), 595–603. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.04.028 (2012).

Craig, A. D. How do you feel—now? The anterior insula and human awareness. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 10(1), 59–70 (2009).

Rudebeck, P. H. & Rich, E. L. Orbitofrontal cortex. Curr. Biol. 28(18), R1083–R1088 (2018).

Uddin, L. Q., Nomi, J. S., Hébert-Seropian, B., Ghaziri, J. & Boucher, O. Structure and function of the human insula. J. Clin. Neurophysiol. 34(4), 300–306 (2017).

Zung, W. W. A rating instrument for anxiety disorders. Psychosom. J. Consult. Liaison Psychiatry (1971).

Daniel, P. & Weber, R. Psychoacoustical roughness: Implementation of an optimized model. Acta Acust. Acust. 83(1), 113–123 (1997).

Aures, W. Berechnungsverfahren für den sensorischen Wohlklang beliebiger Schallsignale. Acta Acust. Acust. 59(2), 130–141 (1985).

Delorme, A. & Makeig, S. EEGLAB: an open source toolbox for analysis of single-trial EEG dynamics including independent component analysis. J Neurosci Methods 134(1), 9–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneumeth.2003.10.009 (2004).

Pion-Tonachini, L., Kreutz-Delgado, K. & Makeig, S. ICLabel: An automated electroencephalographic independent component classifier, dataset, and website. Neuroimage 198, 181–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.05.026 (2019).

Pascual-Marqui, R. D., Faber, P., Kinoshita, T., Kochi, K., Milz, P., Keiichiro, N., & Yoshimura, M. A comparison of bivariate frequency domain measures of electrophysiological connectivity. bioRxiv 459503 (2018).

Granger, C. W. Investigating causal relations by econometric models and cross-spectral methods. Econ. J. Econ. Soc. 424–438 (1969).

Fedorenko, E., McDermott, J. H., Norman-Haignere, S. & Kanwisher, N. Sensitivity to musical structure in the human brain. J. Neurophysiol. 108(12), 3289–3300 (2012).

MacDougall, H. G. & Moore, S. T. Marching to the beat of the same drummer: the spontaneous tempo of human locomotion. J. Appl. Physiol. 99(3), 1164–1173 (2005).

Barlas, T., Sodan, H. N., Avci, S., Cerit, E. T. & Yalcin, M. M. The impact of classical music on anxiety and pain perception during a thyroid fine needle aspiration biopsy. Hormones (Athens) 22(4), 581–585. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42000-023-00473-3 (2023).

Weineck, K., Wen, O. X., & Henry, M. J. Neural synchronization is strongest to the spectral flux of slow music and depends on familiarity and beat salience. Elife 11. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.75515(2022).

Millgram, Y., Joormann, J., Huppert, J. D. & Tamir, M. Sad as a matter of choice? Emotion-regulation goals in depression. Psychol. Sci. 26(8), 1216–1228 (2015).

Yoon, S., Verona, E., Schlauch, R., Schneider, S. & Rottenberg, J. Why do depressed people prefer sad music?. Emotion 20(4), 613 (2020).

Juslin, P. N. & Laukka, P. Expression, perception, and induction of musical emotions: A review and a questionnaire study of everyday listening. J. New Music Res. 33(3), 217–238 (2004).

Punkanen, M., Eerola, T., & Erkkilä, J. Biased emotional preferences in depression: Decreased liking of angry and energetic music by depressed patients. Music Med. (2011).

Ramirez, R., & Vamvakousis, Z. Detecting emotion from EEG signals using the emotive epoc device. In International Conference on Brain Informatics (2012).

Koelsch, S. Towards a neural basis of music-evoked emotions. Trends Cogn. Sci. 14(3), 131–137 (2010).

Salimpoor, V. N., Benovoy, M., Larcher, K., Dagher, A. & Zatorre, R. J. Anatomically distinct dopamine release during anticipation and experience of peak emotion to music. Nat. Neurosci. 14(2), 257–262 (2011).

Moreno-Gutiérrez, J. Á., de Rojas Leal, C., López-González, M. V., Chao-Écija, A. & Dawid-Milner, M. S. Impact of music performance anxiety on cardiovascular blood pressure responses, autonomic tone and baroreceptor sensitivity to a western classical music piano-concert. Front. Neurosci. 17, 1213117 (2023).

Musa, A., Ng, Q. X., Wai, Y. Z. & Iqbal, T. Effect of slow tempo music on markers of anxiety during cataract surgery: Randomized control trial. Taiwan J. Ophthalmol. 12(1), 74–81. https://doi.org/10.4103/tjo.tjo_10_21 (2022).

Toyoshima, K., Fukui, H. & Kuda, K. Piano playing reduces stress more than other creative art activities. Int. J. Music. Educ. 29(3), 257–263 (2011).

Yang, L. 35 Piano melody combined with physical training intervention on students’ anxiety disorders. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry (2025).

Yoshie, M., Shigemasu, K., Kudo, K. & Ohtsuki, T. Effects of state anxiety on music performance: Relationship between the Revised Competitive State Anxiety Inventory-2 subscales and piano performance. Music. Sci. 13(1), 55–84 (2009).

Vassilakis, P. N. Perceptual and Physical Properties of Amplitude Fluctuation and Their Musical Significance (University of California, 2001).

Zwicker, E., & Fastl, H. Psychoacoustics: Facts and models. Vol. 22. (Springer, 2013).

Arnal, L. H., Flinker, A., Kleinschmidt, A., Giraud, A.-L. & Poeppel, D. Human screams occupy a privileged niche in the communication soundscape. Curr. Biol. 25(15), 2051–2056 (2015).

Arnal, L. H., Kleinschmidt, A., Spinelli, L., Giraud, A.-L. & Mégevand, P. The rough sound of salience enhances aversion through neural synchronisation. Nat. Commun. 10(1), 3671 (2019).

Björk, E. The perceived quality of natural sounds. Acta Acust. Acust. 57(3), 185–190 (1985).

Bodner, E., Gilboa, A. & Amir, D. The unexpected side-effects of dissonance. Psychol. Music 35(2), 286–305 (2007).

Koutseff, A. et al. The acoustic space of pain: Cries as indicators of distress recovering dynamics in pre-verbal infants. Bioacoustics 27(4), 313–325 (2018).

Štillová, K. et al. Mozart effect in epilepsy: Why is Mozart better than Haydn? Acoustic qualities-based analysis of stereoelectroencephalography. Eur. J. Neurol. 28(5), 1463–1469. https://doi.org/10.1111/ene.14758 (2021).

Taffou, M., Suied, C. & Viaud-Delmon, I. Auditory roughness elicits defense reactions. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 956 (2021).

Bishop, S. J. Trait anxiety and impoverished prefrontal control of attention. Nat. Neurosci. 12(1), 92–98 (2009).

Ochsner, K. N. & Gross, J. J. The cognitive control of emotion. Trends Cogn. Sci. 9(5), 242–249 (2005).

Etkin, A., Büchel, C. & Gross, J. J. The neural bases of emotion regulation. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 16(11), 693–700 (2015).

White, L. K., Makhoul, W., Teferi, M., Sheline, Y. I. & Balderston, N. L. The role of dlPFC laterality in the expression and regulation of anxiety. Neuropharmacology 224, 109355 (2023).

Yang, K. et al. High gamma band EEG closely related to emotion: Evidence from functional network. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 14, 89 (2020).

Funding

This publication was supported by Hong Kong Polytechnic University through the Undergraduate Research and Innovation Scheme (Project ID: P0047931) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant No. D5000230188).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q. LUO was involved in conceptualization, methodology, software, formal analysis, investigation, writing, writing-review & editing, visualization, and funding acquisition. Y. WANG contributed to the experimental design, data processing, and manuscript preparation and revision. K. YANG contributed to data analysis, result visualization, and interpretation. W. ZHANG, M. XI, A. QIAN, and P. NIE provided resources. A. QIAN also participated in writing-review & editing and funding acquisition. G. CHEN was responsible for supervision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval statement

This study received approval from the Ethics Committee of Biology and Medicine at Northwestern Polytechnical University. (Approval No: 202302054).

Patient consent statement

All participants provided written informed consent and were given detailed information regarding the study. Appropriate compensation was provided, and the confidentiality of personal data was strictly maintained.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Luo, Q., Wang, Y., Yang, K. et al. Acoustic features of music differentially modulate anxiety through EEG gamma oscillations and prefrontal connectivity. Sci Rep 16, 1455 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31161-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31161-4