Abstract

Ge1−xSnx and Si1−x−yGeySnx alloys are promising materials for future nanoelectronic applications owing to their high carrier mobilities and CMOS compatibility. However, ternary Si1−x−yGeySnx transistors have only theoretically been discussed, and there are only a few reports on lateral n-type Ge1−xSnx transistors to benchmark their material performance. The low equilibrium solid solubility of Sn in Si1−xGex (less than 1 at%) requires device fabrication processes at temperatures below the growth temperature of Si1−x−yGeySnx (x > equilibrium solubility) or at non-equilibrium conditions. Therefore, Si-based processes need to be adjusted according to the materials requirements. A relatively easy-to-fabricate device concept are junctionless field effect transistors, which operate as a gated resistor. In this work, we use Ge0.94Sn0.06 and Si0.14Ge0.80Sn0.06 grown on silicon-on-insulator substrates to fabricate and characterize lateral n-type Ge1−xSnx and SiyGe1−x−ySnx junctionless field effect transistors. The transistors were structurally characterized by top-view scanning electron microscopy and cross-sectional transmission electron microscopy. Electrical characterizations by transfer characteristics show the first working n-type Ge1−xSnx and Si1−x−yGeySnx hetero-nanowire transistors, achieving on/off-current ratios of up to eight orders of magnitude.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Germanium-tin (Ge1−xSnx) and silicon–germanium–tin (Si1−x−yGeySnx) alloys are promising CMOS-compatible future materials to overcome material-related limits in the silicon-based transistor technology. The incorporation of Sn into the Ge or Si1−yGey lattice allows an effective band gap engineering. Hence, the Sn-containing group-IV alloys have promised superior mobilities of up to 6000 cm2/Vs for electrons and 4500 cm2/Vs for holes1,2,3,4,5 if the materials can be fabricated in high quality. Transistors based on high carrier mobility channel materials are desired to outperform conventional group-IV transistors in terms of: (i) higher drain-source currents by using the same gate potential, (ii) higher cut-off and operating frequencies, (iii) lower supply voltages, and (iv) reduced power consumption. Ge1−xSnx and Si1−x−yGeySnx alloys are typically grown in the same epitaxy reactors as Si and Si1−yGey by chemical vapor deposition6,7 or molecular beam epitaxy (MBE)8,9. The vertical growth of high-quality Ge1−xSnx on Ge-buffered Si substrates in combination with optimized process steps recently allowed the fabrication of well-performing vertical gate-all-around n-type Ge0.95Sn0.05 field effect transistors (FETs) with small subthreshold swings (SS) of 76 mV dec−1 and Ion/Ioff-ratios of about 7.5 × 10310. This shows the feasibility of fabricating fast Sn-containing transistors and the existence of suitable process windows. On the other hand, most of the integrated circuits in industrial applications are still in a planar or lateral configuration and use p-n junctions or insulating substrates to isolate the devices from the substrates. The invention of insulating substrates such as silicon-on-insulator (SOI) improved the transistor performance significantly11,12. Unfortunately, the fabrication of Ge1−xSnxOI is technologically challenging11,13,14,15, and Si1−x−yGeySnxOI has not been reported yet. A cheaper approach would be the direct growth of Ge1−xSnx and Si1−x−yGeySnx on SOI substrates. However, the growth can suffer from the large lattice mismatch between the Sn-containing alloy and Si. The general feasibility of growing single-crystalline Ge1−xSnx directly on Si substrates has been demonstrated16,17,18, and defect densities of about ~ 107 cm−218 were estimated. Furthermore, increasing the Si concentration in Si1−x−yGeySnx can reduce the lattice mismatch, and post-growth pulsed laser annealing can improve the material quality, as recently shown in reference19. To verify the material quality and processing technology of Ge1−xSnx or Si1−x−yGeySnx on SOI, transistors can be used as suitable electrical devices. One relatively simple device concept is the junctionless field effect transistor (JLFET), which requires a uniform doping concentration in the source, channel, and drain regions. The absence of junctions simplifies the fabrication process, avoids dopant-diffusion-related issues, and allows excellent short-channel characteristics20,21,22. The operation of a JLFET is based on the depletion and accumulation of conducting charge carriers within the highly doped (~ 1019 cm−3) channel region, which is fundamentally different from the well-known inversion-mode MOSFETs23. An explanation of the general JLFET functionality can be found in the supplementary materials, part A, and and its related illustration in Supplementary Figure S1. Based on the channel geometry and gate configuration, many different depletion-based JLFET concepts were proposed 24. JLFETs based on nanowires (NW) allow efficient device control by the gate with subthreshold swings as low as 70 mV dec−122.

In this paper, a fully CMOS-compatible top-down fabrication approach for lateral n-type Ge1−xSnx and Si1−x−yGeySnx on SOI hetero-nanowire junctionless transistors (JNT) is shown. The channel region of a JNT has the shape of a nanowire, allowing better gate control than for thin-film JLFETs. Top-view scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and cross-sectional transmission electron microscopy (TEM) are used to characterize the JNTs structurally. The electrical JNT performance is investigated by the transfer characteristics with applied potentials from the top gate (TG), back gate (BG), and a combination of both gates.

Experimental part

Fabrication of n-type JNTs

The process flow for the fabrication of lateral n-type Ge1−xSnx and Si1−x−yGeySnx on SOI JNTs using a top-down gate-last approach is depicted in Fig. 1, and a processed JNT is shown in Fig. 2. A 20 nm-thick Ge0.94Sn0.06 or Si0.14Ge0.80Sn0.06 layer, in situ doped with antimony (Sb) in the range of 5 × 1019 cm−3, was epitaxially grown by MBE on SOI substrates having a 20 nm top Si layer (step 1). Details about the growth and a comprehensive characterization of the as-grown materials can be found in reference19.

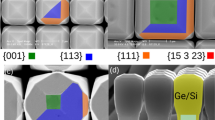

Overview (a) top-view SEM image of the Ge1−xSnx on SOI JNT after top gate fabrication and the magnified image section around the NW (b). The layer stack at selected positions and the distance between the source and drain contact LSD, NW width WNW, NW length LNW, and the top gate (TG) width WTG are allocated.

Afterwards, [110]-oriented single NWs with a length LNW of 0.5 µm and a width WNW of 90 nm (Ge1−xSnx) or 219 nm (Si1−x−yGeySnx) were fabricated by GeOx etching25, spin coating of the negative resist hydrogen silsesquioxane (HSQ), electron beam lithography (EBL), 25% tetramethyl-ammonium hydroxide (TMAH) and MF-319-based development (step 2)26, and inductively-coupled plasma reactive ion etching (ICP-RIE) with chlorine-based chemistry (step 3).

After stripping the HSQ resist by wet etching with 1% hydrofluoric acid (HF) deionized water (DI) solution, the NW dimensions were measured using top-view SEM imaging. The source/drain contacts were fabricated by spin coating the positive EBL resist ZEP520A27,28, EBL exposure, opening of the exposed windows by development, 1% HF:DI native oxide etching, thermal evaporation of 50 nm-thick Ni contacts, and lift-off. The fabricated source/drain Ni contacts have a distance of LDS ≈ 9 µm and cover the Ge1−xSnx or Si1−x−yGeySnx NW contact zones, as visible in Fig. 2a). Afterwards, the low-quality native GeSnOx or SiGeSnOx on the NW structures were etched with the acetic acid:DI etching approach25, and 7 nm aluminum oxide (Al2O3) (equivalent oxide thickness EOT ≈ 3 nm) were deposited by atomic layer deposition (ALD) using Trimethylaluminium (TMA) and water (H2O) as precursors to passivate the NW surface (step 4). In step 5, the TG was fabricated by PMMA spin coating, opening windows for the TG with EBL exposure and structure development, followed by a deposition of 25 nm-thick Pt and 5 nm-thick Au and lift-off. Pt was selected as the TG metal because of the inherent low resistivity and high work function of 5.6–6.4 eV29, which allows an effective depletion of e− in the n-type NW channel. Au was used as a ductile metal to ensure an entire electrical contact around the NW.

Characterization of n-type JNTs

The fabricated JNTs were structurally analyzed by cross-sectional TEM and electrically by measuring the transfer characteristics. An image-Cs-corrected Titan 80–300 microscope (FEI) operated at an accelerating voltage of 300 kV was used for recording high-resolution TEM images. High-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM) imaging and spectrum imaging analysis based on energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDXS) were performed at 200 kV with a Talos F200X microscope equipped with a Super-X EDX detector system (FEI). Before (S)TEM analysis, the specimen mounted in a high-visibility low-background holder was placed for 10 s into a Model 1020 Plasma Cleaner (Fischione) to remove potential contamination. TEM lamellae preparation was done by in situ lift-out using a Helios 5 CX focused ion beam (FIB) device (Thermo Fisher) along the Pt TG, along the NW, and at the Ni source/drain contact. The probe system PA200 from Süss Microtec equipped with a semiconductor characterization system SCS-4200 and a switching matrix with Model 7174A 8 × 12 low-current matrix card from Keithley Instruments was used for electrical measurements. The measurements were carried out in a grey room environment (class 100000). The temperature was kept at 25 °C with a temperature control ATT low temp system C200-60 from Advanced Temperature Test Systems GmbH (ATT). The presented transfer characteristics were performed with a double hysteresis sweep of the gate, and the presented curves belong to the second sweep. In particular, the TG was swept between − 4 V and + 4 V and the BG between − 40 V and + 40 V. For the transfer characteristics, the supply voltage VDS was limited to 0.5 V, since the alloys are metastable and the SOI substrate can suffer from localized self-heating effects during device operation because of the limited heat dissipation through the underlying insulator30,31. Details about the extraction of the JNT figures of merit can be found in the supplementary materials, part B, and and its related illustration Supplementary Figure S2.

Results and discussion

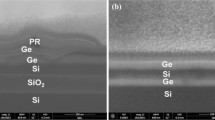

A cross-sectional TEM-based analysis of the fabricated JNTs is shown in Fig. 3. The TEM images in Fig. 3a) and d) as well as the corresponding element distribution maps in Fig. 3b) and e) taken from the TG confirm the general layer stack. However, note that the Ge1−xSnx layer in Fig. 3a) and b) as well as the Si1−x−yGeySnx layer Fig. 3d) and e) are only below 4 nm thick and do not appear fully continous along the TG cross-section. This significantly reduces the n-type conducting cross-section of the hetero-NW, but allows the depletion of the conducting cross-section more efficiently. Furthermore, detecting Sn within these ultrathin layers appears to be difficult, as discussed in Supplementary Materials, Part C, and its related illustration Supplementary Figure S3. An approximately 7 nm-thick Al2O3 layer separates the entire hetero-NW structure from the Pt/Au TG. Areas without Ge1−xSnx or Si1−x−yGeySnx have an additional native SiO2 layer underneath the Al2O3, since the GeOx etching using acetic acid:DI solution is not capable of removing SiO2. The polycrystalline Pt/Au TG appears homogeneous on top of the NW. Figure 3c) and f) show the Ni contact zones: in the center of the contact area for Ge1−xSnx in c) and at the edge of the contact zone for Si1−x−yGeySnx in f). Even without any contact formation annealing, local diffusion of Ni into Ge1−xSnx, Si1−x−yGeySnx, and the upper part of the underlying Si is observed at the contacts; it most likely occurred during the metal deposition process. The Ni-Ge1−xSnx and Ni-Si1−x−yGeySnx contacts are between 10 and 20 nm thick. The presence of a much thicker Ge1−xSnx and Si1−x−yGeySnx layer at the contacts compared to the NW indicates that the acetic acid:DI etching is capable of etching of the defect-rich parts of the alloys. Furthermore, the horizontal distance between the top-Si of the SOI and the Si1−x−yGeySnx, highlighted by the “L” in Fig. 3f), indicates a lateral underetching during the RIE process of about 21 nm in for Si1−x−yGeySnx and 18 nm for Ge1−xSnx. A similar underetching was also observed at the NW structures after fabrication step 3 (see Fig. 1) by using top-view SEM imaging.

Cross-sectional TEM-based analyses of the Ge1−xSnx (a–c) and Si1−x−yGeySnx (d–f) JNTs for the center of the Pt/Au top gate (a, b, d, e), and at the Ni source/drain contact (c and f). The EDXS-based element distribution analyses in (b and c) show superimposed maps for Si (green), Ge (blue), Pt (magenta), Au (light blue), Al (orange), and Ni (cyan).

The back-gated transfer characteristics of the n-type Ge1−xSnx and Si1−x−yGeySnx on SOI JNTs are shown in Fig. 4. Both devices have an n-branch towards positive VBG and a p-branch towards negative VBG. Between both branches, the devices turn off at the IDS minimum (Ioff). The n-branch originates from the highly n-type-doped Ge1−xSnx and Si1−x−yGeySnx thin films. The p-branch likely originates from the contribution of the wider and thicker p-Si layer of the SOI substrate. This is in line with the presence of both branches in the transfer characteristics of p/n-stacked poly-Si junctionless FETs reported in ref.32. For JNTs, the on-current (Ion) is the current in flat band condition and Imax the current in the accumulation mode, as explained in Supplementary materials part A) more in detail. The Ion/Ioff-, Imax/Ioff–ratio, and the subthreshold swing (SS) of the back-gated characteristics are 7.7 × 107, 8.3 × 108, and 3050 mV/dec. (Ge1−xSnx), and 2.5 × 107, 5.5 × 107, and 2370 mV/dec. (Si1−x−yGeySnx), respectively. The SS are relatively large due to the 100 nm-thick buried SiO2 and the defect containing Ge1−xSnx or Si1−x−yGeySnx layers 19.

Back-gated (BG) and top-gated (TG) transfer characteristics of the fabricated n-type Ge1−xSnx (a) and n-type Si1−x−yGeySnx (b) JNT. Solid lines indicate the forward-sweep, and the backward-sweeps are presented as dashed lines. The open symbols highlight the off-current Ioff (circle), on-current Ion (triangle pointing right), and maximum current in accumulation mode Imax (triangle pointing left). Furthermore, the grey symbols are related to the BG, and the purple symbols belong to the TG device parameters. Note: The back-gated and top-gated characteristics share the same common axis.

Controlling the JNTs only by the TG shows clear n-type behavior and a much faster device switching. However, the on-currents (Ion) are significantly lower than the back-gated result. The general difference between the TG and BG cases can be understood by the different active device architectures. In the back-gated case, the BG potential affects the whole JNT structure, including the source/drain contacts. This lowers the total alloy resistance and improves the Schottky-like contacts due to enhanced band bending33, which increases Ion. In the case of the top-gated JNT, the gate width covers only a fraction of the NW, which allows the control of the JNT but does not allow carrier injection away from the TG.

In order to benefit from the higher IDS–ratios in the back-gated case and the steeper switching in the top-gated case, a constant VBG was applied and the TG was used to control the JNT, as shown in Fig. 5. This device configuration simulates a kind of gate-all-around structure and allows one to judge the entire performance of these first reported n-type Ge1−xSnx and Si1−x−yGeySnx JNTs. The IDS-VTG characteristics of Ge1−xSnx in Fig. 5a) show a relatively constant Ioff of around 10 fA, nearly independent of VBG. On the other hand, Ion and Imax increase significantly with increasing VBG, as discussed in more detail below. For Si1−x−yGeySnx in Fig. 5b), Ion and Imax increase with increasing VBG. Unfortunately, Ioff also increases, since the much wider NW cannot be fully depleted using only the TG.

The JNTs in Fig. 5 were analyzed in terms of their SS, Ion/Ioff, and Imax/Ioff, and the results are summarized in Fig. 6. In the case of the Ge1−xSnx JNT, the SS decreases for small VBG, most likely due to the gate-all-around like device structure. However, for higher BG potentials (VBG > 4 V), the electrical fields of the gates seem to interact with each other. This can be the reason for the slight increase of the SS for VBG > 4 V in Fig. 6a). On the other hand, the IDS-ratios increase significantly with increasing VBG from Ion/Ioff = 5.3 × 102 and Imax/Ioff = 2.9 × 103 at VBG = 0 V to Ion/Ioff = 7.2 × 107 and Imax/Ioff = 1.4 × 108 at VBG = 17 V, which is close to the excellent IDS-ratios of the back-gated results. The SS of Si1−x−yGeySnx in Fig. 6b) are generally higher, since the large WNW prevents steep switching by the TG, and the additional BG potential cannot improve the SS. This result suggests that shrinking the device dimensions will lead to significantly smaller SS. In the past, SS of 70 mV/dec. were reported for n-type Si junctionless transistors with a NW diameter of about 10 nm22, which is close to the physical limit. Owing to the inability to turn off the Si1−x−yGeySnx JNT completely, the IDS-ratios can be only slightly boosted by applying the additional VBG from Ion/Ioff = 7.3 × 104 and Imax/Ioff = 1.1 × 105 at VBG = 0 V to Ion/Ioff = 2.4 × 105 and Imax/Ioff = 5.2 × 105 at VBG = 6 V. A brief benchmark of n-type Ge1−xSnx and Si1−x−yGeySnx transistors and some future prospects of these devices are summarized in Supplementary materials part D) as well as in the related illustrations Supplementary Figure S4 and Supplementary Table S1.

Extracted minimum subthreshold swing SS and drain-source current IDS-ratios of the JNTs shown in Fig. 5a) for Ge1–xSnx and b) for Si1–x–yGeySnx in dependence on a constant applied VBG.

Conclusion

Lateral n-type Ge1−xSnx and Si1−x−yGeySnx on SOI transistors were fabricated using a top-down gate-last JNT approach. The fabrication process requires further improvements, but back-gated single-nanowire JNTs have large Ion/Ioff-ratios of about 1 × 108. The top-gated JNTs have smaller Ion/Ioff-ratios of about 1 × 103 (Ge1−xSnx) and 1 × 105 (Si1−x−yGeySnx) respectively. The combined application of VBG and VTG potentials simulates a kind of gate-all-around JNT architecture, which allows one to drive the JNT to an operating point by using a constant VBG and then modulating the current by the VTG sweep. By this measure, the large Ion/Ioff-ratios from the back-gated JNT can be achieved with a much steeper JNT switching by the top gate.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Liu, Y. et al. Mobility enhancement in undoped Ge0.92Sn0.08 quantum well p-channel metal-oxide-semiconductor field-effect transistor fabricated on (111)-oriented substrate. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 29, 115027. https://doi.org/10.1088/0268-1242/29/11/115027 (2014).

Gupta, S., Magyari-Köpe, B., Nishi, Y. & Saraswat, K. C. Achieving direct band gap in germanium through integration of Sn alloying and external strain. J. Appl. Phys. 113, 073707. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4792649 (2013).

Sau, J. D. & Cohen, M. L. Possibility of increased mobility in Ge-Sn alloy system. Phys. Rev. B 75, 045208. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.75.045208 (2007).

Mukhopadhyay, B., Sen, G., Basu, R., Mukhopadhyay, S. & Basu, P. K. Prediction of large enhancement of electron mobility in direct gap Ge1−xSnx alloy. Phys. Status Solidi B 254, 1700244. https://doi.org/10.1002/pssb.201700244 (2017).

Kaur, J., Basu, R. & Sharma, A. K. Design and analysis of Si1−xyGeySnx-Si1−xGex alloy based solar cell emphasizing on Ge composition 15%. SILICON 15, 397–404. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12633-022-02025-7 (2022).

Lei, D. et al. Germanium-tin (GeSn) P-channel fin field-effect transistor fabricated on a novel GeSn-on-insulator substrate. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 65, 3754–3761. https://doi.org/10.1109/TED.2018.2856738 (2018).

Wirths, S., Buca, D. & Mantl, S. Si–Ge–Sn alloys: From growth to applications. Prog. Cryst. Growth Charact. Mater. 62, 1–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcrysgrow.2015.11.001 (2016).

Schwarz, D., Funk, H. S., Oehme, M. & Schulze, J. Alloy stability of Ge1−xSnx with Sn concentrations up to 17% utilizing low-temperature molecular beam epitaxy. J. Electron. Mater. 49, 5154–5160. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11664-020-08188-6 (2020).

Zaima, S. et al. Growth and applications of GeSn-related group-IV semiconductor materials. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 16, 043502. https://doi.org/10.1088/1468-6996/16/4/043502 (2015).

Liu, M. et al. Vertical GeSn nanowire MOSFETs for CMOS beyond silicon. Commun. Eng. 2, 7. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44172-023-00059-2 (2023).

Han, K., et al. First demonstration of complementary FinFETs and tunneling FinFETs co-integrated on a 200 mm GeSnOI substrate: A pathway towards future hybrid nano-electronics systems. In 2019 Symposium on VLSI Technology. pp T182–T183. https://doi.org/10.23919/vlsit.2019.8776539 (2019).

Wu, H., et al. First experimental demonstration of Ge 3D FinFET CMOS circuits. In 2015 Symposium on VLSI Technology (VLSI Technology). pp T58–T59. https://doi.org/10.1109/vlsit.2015.7223702 (2015).

Lei, D. et al. GeSn-on-insulator substrate formed by direct wafer bonding. Appl. Phys. Lett. 109, 022106. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4958844 (2016).

Maeda, T. et al. Ultra-thin germanium-tin on insulator structure through direct bonding technique. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 33, 124002. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6641/aae620 (2018).

Lin, G. et al. Fabrication of germanium tin microstructures through inductively coupled plasma dry etching. IEEE Trans. Nanotechnol. 20, 846–851. https://doi.org/10.1109/TNANO.2021.3115509 (2021).

Wanitzek, M., et al. GeSn-on-Si Avalanche photodiodes for short-wave infrared detection. In ESSCIRC 2022—IEEE 48th European Solid State Circuits Conference (ESSCIRC). pp 169–172. https://doi.org/10.1109/esscirc55480.2022.9911363 (2022).

Roucka, R. et al. Versatile buffer layer architectures based on Ge1−xSnx alloys. Appl. Phys. Lett. 86, 191912. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1922078 (2005).

Bauer, M. et al. Ge–Sn semiconductors for band-gap and lattice engineering. Appl. Phys. Lett. 81, 2992–2994. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1515133 (2002).

Steuer, O. et al. Structural changes in Ge1−xSnx and Si1−xyGeySnx thin films on SOI substrates treated by pulse laser annealing. J. Appl. Phys. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0218703 (2024).

Lee, C.-W. et al. Performance estimation of junctionless multigate transistors. Solid-State Electron. 54, 97–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sse.2009.12.003 (2010).

Lee, I.F. C. W. et al. Shortchannel junctionless nanowire transistors, International Conference on Solid State Devices and Materials SSDM. pp 1044–1045. https://confit.atlas.jp/guide/event-img/ssdm2010/C-9-5L/public/pdf_archive?type=in (2010).

Barraud, S. et al. Scaling of trigate junctionless nanowire MOSFET with gate length down to 13 nm. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 33, 1225–1227. https://doi.org/10.1109/LED.2012.2203091 (2012).

Colinge, J. P. et al. Nanowire transistors without junctions. Nat. Nanotechnol. 5, 225–229. https://doi.org/10.1038/nnano.2010.15 (2010).

Nowbahari, A., Roy, A. & Marchetti, L. Junctionless transistors: State-of-the-art. Electronics 9, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics9071174 (2020).

Gangnaik, A. S., Georgiev, Y. M., Collins, G. & Holmes, J. D. Novel germanium surface modification for sub-10 nm patterning with electron beam lithography and hydrogen silsesquioxane resist. J. Vac. Sci. Technol., B: Nanotechnol. Microelectron. Mater., Process., Meas., Phenom. 34, 041603. https://doi.org/10.1116/1.4948916 (2016).

Henschel, W., Georgiev, Y. M. & Kurz, H. Study of a high contrast process for hydrogen silsesquioxane as a negative tone electron beam resist. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. B: Microelectron. Nanometer Struct. Process. Meas. Phenom. 21, 2018–2025. https://doi.org/10.1116/1.1603284 (2003).

Nishida, T., Notomi, M., Ryuzo Iga, R. I. & Toshiaki Tamamura, T. T. Quantum wire fabrication by E-beam elithography using high-resolution and high-sensitivity e-beam resist ZEP-520. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 31, 4508–4514. https://doi.org/10.1143/JJAP.31.4508 (1992).

Kurihara, K. et al. An electron beam nanolithography system and its application to Si nanofabrication. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 34, 6940–6949. https://doi.org/10.1143/JJAP.34.6940 (1995).

Derry, G. N. & Ji-Zhong, Z. Work function of Pt(111). Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter. 39, 1940–1941. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.39.1940 (1989).

Singh, R. K., Saxena, A. & Rastogi, M. Silicon on insulator technology review. Int. J. Eng. Sci. Emerg. Technol. 1(1), 1–16 (2011).

Claeys, C., Mercha, A. & Simoen, E. Low-frequency noise assessment for deep submicrometer CMOS technology nodes. J. Electrochem. Soc. 151, G307–G317. https://doi.org/10.1149/1.1683633 (2004).

Cheng, Y.-C., et al. A highly scalable poly-Si junctionless FETs featuring a novel multi-stacking hybrid P/N layer and vertical gate with very high Ion/Ioff for 3D stacked ICs. In 2016 IEEE Symposium on VLSI Technology. pp 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1109/VLSIT.2016.7573429 (2016).

Mikolajick, T., Heinzig, A., Trommer, J., Baldauf, T. & Weber, W. M. The RFET—A reconfigurable nanowire transistor and its application to novel electronic circuits and systems. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 32, 043001. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6641/aa5581 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This work was partially supported by the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (BMBF) under the project “ForMikro”: Group-IV heterostructures for high-performance nanoelectronic devices (SiGeSn NanoFETs) (Project-ID: 16ES1075). The authors thank Annette Kunz and Andreas Worbs for TEM specimen preparation. Furthermore, the use of the HZDR Ion Beam Center TEM facilities and the funding of TEM Talos by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF), Grant No. 03SF0451, in the framework of HEMCP are acknowledged. Additionally, we acknowledge the help of Muhammad Moazzam Khan, Claudia Neisser, Tommy Schönherr, Philipp Weinreich, Bernd Scheumann, Christiane Kranz, Dr. Libo Ma, and Dr. Min Tang for sharing their process capabilities at HZDR and Leibniz Institute of Solid State and Materials Research Dresden.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Oliver Steuer wrote the main manuscript text, analyzed the data and prepared figures. All authors reviewed the manuscript and supported in the fabrication or characterization of the devices.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Steuer, O., Ghosh, S., Schwarz, D. et al. Fabrication and characterization of n-type Ge1−xSnx- and Si1–x–yGeySnx-on-SOI junctionless transistors. Sci Rep 15, 44659 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31272-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31272-y