Abstract

This study investigated the comparative effects of small-sided games (SSG) and Hoff circuit (HC) training on physical, technical, and psychophysiological parameters in highly trained youth soccer players. Twenty-six youth players from a professional team were randomly allocated to either an SSG group (n = 13, age = 17.53 ± 0.49 years) or an HC group (n = 13, age = 17.54 ± 0.5 years). The six-week intervention comprised two additional training sessions per week alongside regular team training. Pre- and post-program assessments evaluated physical performance (Vameval test, 5-Jump Test, 10 m and 30 m sprints, and Illinois agility test), technical skills (passing accuracy, possession, interceptions, tackling, and heading). Perceptual responses (RPE and PACES) were evaluated after each session. The HC protocol involved a 290 m dribbling circuit performed at 90–95% HRmax, whereas the SSG emphasized ball possession and tactical gameplay under game-like conditions. The results showed that both training modalities significantly improved maximum aerobic speed (MAS) (p < 0.05). However, the SSG group demonstrated superior improvements in sprint performance (10 m and 30 m; p < 0.01) and agility (Illinois test; p < 0.01) compared to the HC group. SSG training was also more effective in enhancing technical skills, particularly passing accuracy (p < 0.05) and interceptions (p < 0.05). No significant between-group differences were observed in heart rate responses (p > 0.05) or RPE (p > 0.05). Notably, SSG participants reported significantly higher enjoyment levels (p < 0.05), suggesting enhanced motivation and training adherence. SSG training offers superior benefits for sprint performance, agility, technical skill development, and player enjoyment compared to circuit-based training in youth soccer players. These findings support the integration of SSG as a primary training methodology for coaches seeking to optimize athletic performance, technical proficiency, and player engagement in youth soccer development programs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Soccer is a high-intensity sport that requires players to perform a complex combination of sprints, rapid directional changes, and jumps, imposing significant physiological, technical, and cognitive demands on athletes1. Given the intermittent nature of soccer, players must develop a well-rounded athletic profile that encompasses endurance, agility, speed, strength, and technical mastery. The ability to sustain high-intensity efforts while maintaining technical precision and tactical awareness is crucial for optimizing the performance. Consequently, structured training programs that replicate the physical and cognitive challenges of competitive matches are essential for enhancing players’ capabilities2.

Recognizing this necessity, coaches and sports scientists have increasingly focused on developing training methodologies that closely simulate real game conditions3,4. Traditionally, conditioning programs in soccer have emphasized on broad physical fitness, such as strength, sprint capacity, and aerobic endurance, frequently through interval work, resistance training, or running drills, with little focus on technical or tactical aspects2. However, this physically oriented approach often fails to reflect the complex and multifaceted demands of real match play. Indeed, match performance requires continuous interaction between physical execution, tactical decision-making, and technical precision, which traditional methods do not fully reproduce. In response to these limitations, Modern training approaches aim to integrate technical, tactical, and physiological components to maximize match-specific performance5. Among these approaches, Small-sided games (SSGs) and Hoff circuit (HC) training have gained recognition for their ability to develop soccer-specific skills through match-like, high-intensity activities5,6. HC training uses systematic circuit-based exercises that combine aerobic and anaerobic efforts with ball-handling drills, simultaneously improving cardiovascular fitness, muscular endurance, and technical abilities6,7,8. Through the integration of sport-specific exercises into an endurance-based program, HC training enhances muscular endurance and cardiovascular fitness, potentially improving performance during games6. Additionally, its intensity-driven structure produces heart rate responses that are similar to those of competition, indicating that it can successfully mimic some of the physiological demands of competitive settings8. Research on young players (13–16 years old) shows that HC interventions, such as a 6-week program, elicit heart rates (HR) comparable to competitive matches while enhancing repeated sprint ability, technical execution, and VO₂max7,8. Coaches can adjust technical complexity, volume, and intensity within this structured framework, allowing quantifiable monitoring of player progress.

Similarly, SSGs create game-like scenarios that integrate tactical, technical, and physical development9,11. By modifying pitch size, player numbers, or rules, SSGs generate repeated high-intensity efforts and frequent technical actions, closely mirroring match demands10,11. Studies indicate that SSGs significantly improve agility, horizontal jump, aerobic and anaerobic capacity, as well as engagement and motivation, promoting adherence and long-term skill acquisition12. For instance, 4v4 SSGs have been shown to markedly increase high-intensity running and technical involvement in U15 players10. Moreover, SSGs are associated with increased player enjoyment and intrinsic motivation owing to their engaging and competitive format, which can promote long-term adherence and skill development9. The psychological benefits of SSGs, particularly in terms of motivation and player engagement, make them an attractive option for youth training programs2. However, the effectiveness of small-sided games can be influenced by inappropriate task design, inadequate coach supervision, or differences in player fitness13. Excessive use may also limit exposure to full-pitch tactical situations14. Therefore, careful and balanced integration within the training program is essential to maximize benefits and minimize potential drawbacks13.

Although both training methods are widely used in soccer preparation, limited research has directly compared their effects on young players’ physical performance, physiological responses, and psychological engagement. Understanding how these training modalities influence fitness, motivation, and enjoyment is important for optimizing training strategies. As enjoyment is a key factor in long-term athletic development, assessing the psychological impact of these training methods is essential for designing effective youth training programs. This study aimed to evaluate and compare the effects of SSG and HC training on the physical capacities, technical performance, and psychophysiological responses of highly trained youth soccer players, providing valuable insights for coaches seeking to implement the most effective training programs. By analyzing their respective contributions to physical conditioning, skill development, and psychological engagement, this study offers a comprehensive perspective on best practices for fostering young soccer talent.

Materials and methods

Participants

Twenty-six youth players from a professional soccer club competing in national youth leagues in Algeria participated in the study. All participants had over 6 years of competitive soccer experience and typically trained 6 to 7 times per week, with an average training duration of 9.5 ± 1.54 h per week. The players were divided into two groups: the SSG group (SSG-G), which engaged in SSG training (n = 13, age: 17.53 ± 0.49 years, height: 177.5 ± 3.27 cm, weight: 72.76 ± 3.27 kg, body fat %11 ± 1.03), and the HC training group (HC-G), which followed an HC training program (n = 13, age: 17.54 ± 0.5 years, height: 176.84 ± 3.43 cm, weight: 71.92 ± 3.97 kg, body fat %11.23 ± 1.12). Goalkeepers were not included in the study because of their different physical training regimens. Prior to initiating the recruitment process, a sample size calculation was performed using G*Power software (version 3.1.9.4; University of Kiel, Kiel, Germany). The calculation showed that 26 players were necessary to achieve an 81.5% likelihood of correctly rejecting the null hypothesis and identifying significant differences. The players were familiar with the testing protocols, which were part of their performance assessments, and were advised to maintain consistent dietary and hydration practices throughout the testing period. Written informed consent was obtained from all players. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the High Institute of Sports and Physical Education of Kef (approval number: 013/2023; approval date: April 18, 2023) and was conducted in compliance with the ethical standards for human research as outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Study design

The study was conducted during the 2023–2024 soccer season lasting six weeks. It followed a controlled experimental design in which participants were assigned to two training interventions: Hoff Circuit (HC) and small-sided games (SSG). The study took place on the same synthetic grass training field and at the same time each day to minimize circadian effects on physiological variables. Before the start of the six-week training program, participants underwent anthropometric measurements (weight and height) and completed a progressive maximal test (Vameval) to estimate their maximal aerobic speed (MAS) and determine their maximum heart rate (HRmax), which was subsequently used to individualize training intensities. The intervention consisted of two training sessions per week, implemented alongside regular team training. Physical performance (Vameval test, 5-jump test, 10 m and 30 m sprints, Illinois agility test), technical performance (5 vs. 5 SSG metrics including passing, possession, interception, tackling, and heading), and psychological responses (rating of perceived exertion [RPE] and physical enjoyment [PACES]) were assessed before and after the program. Participants were instructed to avoid intense activity within 48 h prior to assessments, refrain from eating within 3 h of testing, and abstain from caffeine for 8 h before evaluations. To minimize potential learning effects, all participants were familiarized with the RPE, PACES, and POMS questionnaires prior to the study, and all test sessions were conducted by the same coaching staff (two physical coaches and one assistant coach) to ensure consistency.

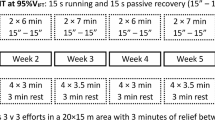

Training intervention descriptions

Both training protocols began with a standardized 15-min warm-up designed to prepare the participants for the upcoming physical demands. The warm-up included light jogging to gradually elevate heart rate, coordination drills to enhance motor skills, and dynamic stretching to increase flexibility and range of motion. The session concluded with four 10-m sprints to stimulate anaerobic performance. Static stretching was intentionally excluded from the warm-up to maintain muscle elasticity and readiness for high intensity activity. After the warm-up, a 3-min recovery period allowed the participants to hydrate and prepare mentally for the training. Each training method lasted 28 min, consisting of four intervals of 4 min each, followed by 3 min of passive recovery between intervals. This structure ensured that the participants could maintain high intensity throughout the training while providing adequate recovery to optimize performance gains.

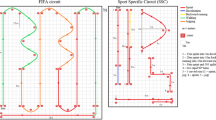

For the Hoff circuit (HC) exercise, all players performed the protocol simultaneously, although they did not start from the same position; each player began at a different point on the circuit because the circuit was too long. Players navigated a dribbling circuit while the Polar Team Sport System ensured their HR stayed between 80 and 90% of HRmax in real time. The circuit has a total length of 51.5 m on the left side and 55 m on the right, with a width of 35 m. Players perform backward dribbling between cone 7 and the goal at Gate 8. The circuit was equipped with three hurdles (30–35 cm in height) and 22 cones, two of which marked the starting line and two served as gates for the backward running. Each lap covered a distance of 290 m. The distance from hurdle 3 to cone 1 was set at 30.5 m, with the spacing between cones (1–2, 2–3, 3–4, 4–5, 5–6, and 6–7) consistently set at 25.5 m (Fig. 1). If a player did not reach the target intensity, the evaluator verbally instructed them to increase their speed. The circuit’s length prevented any collisions or interferences between players, as faster players could overtake slower ones and continue their effort uninterrupted. The 5 vs. 5 SSG exercises were held outdoors on a field measuring 36 by 24 m, strictly following the dimensions and time constraints established in prior studies12,15. Coaches played an active role in motivating players to sustain a high level of intensity throughout the sessions, providing additional balls as necessary to ensure an uninterrupted play. The primary objective of the SSG was to maximize ball possession, encouraging players to develop tactical awareness and decision-making skills while maintaining control of the game. The coaches actively moved around the training area, offering support and motivation to the participants throughout the exercise.

Anthropometric measurements

Height and body mass were measured following standardized protocols, with measurement errors of ≤ 0.2 kg and 5 mm, respectively. A digital scale (OHAUS, Florham Park, NJ, USA) was used to record height and body mass to the nearest 0.1 cm and 0.1 kg, respectively. Body fat percentage was estimated using the four-site skinfold thickness (biceps, triceps, subscapular, and supraspinal), measured with a calibrated Harpenden caliper (Holtain Instruments, UK).

Physical performance assessments

Physical performance evaluations included the 5-Jump Test (5JT), Vameval test, 10 m and 30 m sprint tests, and Illinois agility test. These assessments were conducted prior to the start of the study and again after a 6-week training period. Testing was organized over two consecutive days: the first day included the sprint tests, the Illinois agility test, and the 5JT, while the second day focused on the Vameval test. The 5JT was conducted outdoors on synthetic grass in line with the methodology established by Chamari et al.8. The participants performed five consecutive jumps, and the total distance covered was measured in meters using a measuring tape. Two maximal 30-m sprints were performed on a synthetic turf surface, with a split time taken at the 10-m mark. Each sprint was separated by a 3-min recovery period16. The starting position was standardized to a stationary split stance, with the toe of the dominant foot positioned 0.5 m behind the start line. Times were measured using photoelectric cells (Brower Timing System; Salt Lake City, UT, USA). to ensure precise timing. The fastest times at both the 10-m and 30-m marks were used for analysis. The Illinois agility test was used to assess the participants’ agility17. The course, marked by two lines 10 m apart, had participants start lying flat with their hands by their shoulders. After a verbal cue, they sprinted to the touch line (point A), returned to the starting line (point B), and navigated the cones. They sprinted to the touch line (point C) before completing the task. Participants aimed to complete the course quickly, with errors such as knocking cones or deviating from the path, resulting in trial cancellation. Time was recorded using a photoelectric timing system (Brower Timing System; Salt Lake City, UT, USA). To assess individual maximal aerobic speed (MAS) and maximum heart rate (HRmax), the participants performed the Vameval test on a 200-m outdoor track15. The players ran between ten cones positioned 20 m apart, following an auditory cue. The test began at a speed of 8 km h-1 and increased by 0.5 km h-1 every minute until the players reached exhaustion. The speed achieved during the final one-minute stage was recorded as the player’s MAS. Throughout the test, HR was monitored using a Polar Team Sport System, and the highest average heart rate over a 5-s interval was noted as HRmax.

Technical performance

The technical performance metrics analyzed during 5 vs. 5 SSG before and after each training period included the following: the percentage of successful individual passes, number of lost balls, frequency of individual duels, ball possession counts, interceptions, tackles, and headers. The SSGs were recorded using Sony Handycam DVD 850 video cameras positioned at an elevated vantage point along the halfway line, approximately 10 m behind the sideline. A hand notation system aligned with the technical definitions outlined in Table 1 was used to document these metrics. This approach has been validated as a reliable means of evaluating technical actions in soccer18,19. The selected technical actions were specifically relevant to the game, frequently occurring during SSGs and matches, and well-defined in the existing soccer literature20,21. An experienced researcher reviewed all SSG recordings, and each recording was analyzed twice to establish intrarater reliability using the kappa coefficient15,22. The kappa values for the assessed variables ranged from 0.86 to 0.94, indicating a high level of consistency in evaluations.

Measurements of exercise intensity

Heart rate (HR) was continuously monitored at 5-s intervals during all training sessions using the Polar Team2 Pro System (Polar Electro OY), providing an objective measure of exercise intensity. HR data were expressed as a percentage of the maximum heart rate (%HRmax), which allowed for a thorough assessment of the physiological load. For each session, the average heart rate (HRmean) was computed for both HC and SSG training modalities. The %HRmax for each session was calculated using the following formula: %HRmax = (HRmean/HRmax) × 100. The internal training load was assessed immediately after each HC and SSG intervention using the Borg CR-10 scale (RPE)23, a widely recognized tool for measuring perceived exertion. This scale allows athletes to subjectively evaluate the intensity of their efforts, providing valuable insights into their psychophysiological responses to training. Previous research has validated its reliability and effectiveness in assessing exercise intensity across various sports contexts24. To ensure accurate and consistent responses, the participants were familiarized with the RPE scale. This familiarization phase included detailed explanations of the scale’s numerical values and verbal descriptors, along with practical applications to help athletes associate their perceived exertion with the corresponding RPE.

Physical enjoyment

To evaluate positive affect during physical activity, the Physical Activity Enjoyment Scale (PACES) was employed, consisting of eight items, as described by Selmi et al.15. Following each training session (5 min), participants responded to the question: “How did you feel during the exercise?” Enjoyment levels were measured on a 7-point scale, where 1 indicated a highly enjoyable experience and 7 indicated a lack of enjoyment. The total PACES score ranged from 8 to 56, with higher scores reflecting greater perceived enjoyment.

Statistical procedures

Statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, version 26.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Data are presented as mean (M) ± standard deviation (SD). Prior to applying parametric tests, the normality assumption was verified using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. The study employed a mixed design with repeated measures, including a between-subjects factor (group: SSG-G vs. HC-G) and a within-subjects factor (time: pre- vs. post-intervention). Accordingly, a two-way repeated-measures ANOVA (group × time) was conducted to examine the main and interaction effects on all physical performance (MAS, 10 m and 30 m sprint, five-jump test, Illinois agility test) and technical performance variables (duel, successful pass, lost ball, possession, interception, tackle, and heading). For the physiological variables HR (HRmean, %HRmax), RPE) and PACES score recorded during all training sessions were averaged per participant across the six-week intervention period, and group comparisons were performed using independent-samples Student’s t-tests, with effect sizes reported as Cohen’s d, with effect sizes classified as trivial (< 0.2), small (0.2–0.5), moderate (0.5–0.8), or large (> 0.8)25. Bonferroni-adjusted pairwise comparisons were applied as post hoc tests for significant ANOVA effects. Partial eta squared (η2p) was used to report effect sizes for ANOVA results. A significance level of p ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Physical performance

Both training methods resulted in improvements in physical performance. Significant group × time interactions for sprint and agility measurements were found in the two-way repeated-measures ANOVA, along with significant main effects of time for MAS, 10 m and 30 m sprints, the 5-jump test, and the Illinois agility test. While both groups increased MAS and 5-jump performance, post-hoc comparisons revealed that SSG-G improved sprint times and agility more than HG (Table 2, Fig. 2).

Physical performance measurements for both training programs (SSG and HC) before (T1) and after (T2) the 6-week intervention. MAS: Maximal Aerobic Speed; 10-m sprint time; 30 m: 30-m sprint time; 5JT: cumulative distance of five consecutive jumps; Illinois agility: time to complete the Illinois agility test; m: meters; km h-1: kilometers per hour; m s-1: meters per second. *Indicates a significant difference between pre- and post-intervention. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Technical performances

Duels, successful passes, lost balls, and interceptions all showed notable increases with time, with significant group × time interactions, suggesting superior gains in SSG-G (Table 3). Only SSG-G showed significant improvements, according to post-hoc comparisons; HC-G showed no discernible changes. There were no discernible main or interaction effects for variables like possession, tackles, or headers (Fig. 3).

Technical aspect measurements for both training programs (SSG and HC) were taken before (T1) and after (T2) each intervention. SSG-G: small-sided games group; HC: Hoff circuit training group. Duel : number of duels won, %Successful pass : percentage of successful passes (%), Lost ball : number of balls lost, Possession : ball possession (%), Interception : number of interceptions, Tackle = number of tackles, Heading : number of successful headers. *Indicates a significant difference between pre- and post-intervention for both the SSG and HC training. ***p < 0.001.

The exercise intensity

No statistically significant differences were observed between SSG-G and HC-G in terms of RPE, HRmean, or %HRmax (p > 0.05) (Table 4).

Perceived enjoyment

Perceived enjoyment as measured by PACES, was significantly higher in the SSG-G (48.89 ± 2.45) than in the HC-G (43.37 ± 2.66; p < 0.001, ES = 2.55, large) (Fig. 4).

Discussion

This study assessed the effects of SSG and HC training on the physical condition, technical aspects, physiological responses, and enjoyment of young soccer players. Both methods improved certain aspects of physical condition (e.g., MAS and 5-jump performance). However, only SSG training led to significant improvements in sprint times (10 m and 30 m), agility, explosive power, and technical skills (passing accuracy and interceptions). Additionally, the higher enjoyment associated with SSG suggests that it may lead to better long-term motivation and adherence than HC training.

Concerning the physical performance Our findings provide substantial evidence of improvements in multiple physical performance variables after both training programs. However, SSG-G demonstrated more pronounced improvements than HC-G, particularly in the 10 m and 30 m sprints, the Illinois agility test, and the 5-jump test.

The significant main effect of time observed for all physical performance measures, including the MAS, 10 m sprint, 30 m sprint, 5-jump test, and Illinois agility test, highlights the efficacy of both SSG and HC in enhancing physical performance. Notably, both training programs resulted in a significant increase in MAS (SSG: + 1.8 km h⁻1; HC: + 1.5 km h⁻1), indicating that both SSG and HC effectively improved aerobic capacity. These MAS gains are comparable to those documented in earlier research, which found that short high-intensity mesocycles resulted in MAS or VO₂/field-test improvements of a comparable size2,8,26. This supports the interpretation that over the course of six weeks, both procedures provided an aerobic stimulation strong enough to elicit central and peripheral adaptations. This is consistent with previous studies that have shown the benefits of high-intensity exercises like SSG27,28,29 and circuit training6,7,8 on aerobic fitness. The significant increase in MAS suggests that these programs can enhance the endurance capacity of soccer players, which is crucial for sustaining performance during match play7,30.

In terms of sprint performance, the 10 m and 30 m sprint times showed significant improvements in both groups, with the SSG-G exhibiting a more substantial reduction in sprint times. These results reflect the well-established benefits of SSG training in improving sprint performance, likely due to enhanced neuromuscular efficiency and sprinting mechanics31,32. The SSG-G demonstrated greater improvements in sprinting and explosive capabilities compared to the HC-G30. This finding is supported by the significant interaction effect between group and time observed in the 10 and 30 m sprint tests, which showed that the SSG-G group achieved greater improvements (10 m: F = 9.84, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.29; 30 m: F = 4.53, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.16). These results emphasize the potential of SSG in enhancing short-distance sprinting, which is a key component of soccer performance31,33. These findings are consistent with studies30,31, who found that game-based or match-profiled training produced better short-sprint and acceleration increases than more linear running or isolated conditioning. Moreover, the 5-jump test, which assesses explosive strength and lower-body power, also showed a significant increase in performance in both groups, with the SSG-G demonstrating a greater improvement2. This finding aligns with prior research suggesting that explosive strength can be enhanced through high-intensity interval training and sport-specific drills34. This result reinforces the notion that SSG, by incorporating repeated bouts of high-intensity activity, is particularly effective in enhancing power output and muscular endurance2. The Illinois agility test, which measures agility and quick directional changes, also exhibited significant improvements in both groups. However, as with the sprint and jump tests, the SSG-G showed superior results, particularly in terms of the time required to complete the test. This is consistent with the nature of SSG, which inherently involve frequent changes in direction, thus improving an athlete’s agility and ability to maneuver under pressure31,35. This result suggests that SSG plays a role in enhancing agility, which is an essential component of soccer performance, particularly in defensive and offensive maneuvers36. These results are in line with the experimental study33 and the meta-analysis by34, which showed that SSGs, as opposed to running-based HIIT or continuous conditioning, promote greater sport-specific adaptations, particularly in agility and explosive performance. Therefore, our results support the conclusion that SSGs provide a more efficient approach for developing neuromuscular and functional capacities that are directly relevant to the demands of team sport performance.

The results of this study highlight significant improvements in several key technical aspects of soccer performance following both SSG and HC training, with SSG showing greater effectiveness. higher gains in interceptions (+ 5.4% vs. + 1.8%) and passing accuracy (+ 7.3% in SSG-G vs. + 2.1% in HC-G) following SSG. These quantitative differences highlight how contextualised, high-pressure practice helps transfer technical skills to match-like situations36. For duels, a significant main effect of time was observed (F = 16.85, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.41), indicating overall improvement in players’ ability to win one-on-one challenges across the training period. Additionally, a significant interaction effect (group × time; F = 13.79, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.36) was found, suggesting that the magnitude of improvement differed between groups, with the SSG program leading to greater gains compared with the HC program. This improvement is likely due to the high intensity of both training programs, which simulate match conditions and emphasize physical confrontations for possession4. The most significant improvements were observed in the percentages of successful passes, lost balls, and interceptions. The SSG-G showed significant improvements in passing accuracy, likely due to the pressure-filled passing scenarios in SSGs, which replicate match situations and improve decision-making and technical skills27. Similarly, the SSG-G exhibited a significant reduction in the number of lost balls, reflecting better ball control and decision-making under pressure27. In addition, significant improvements in interceptions were observed in the SSG-G, suggesting that SSGs foster better defensive awareness and anticipation, which are key skills for intercepting passes11.

The psychophysiological responses to the SSG and HC training programs did not show any significant differences between the two groups in terms of RPE, mean HRmean, or %HRmax. These findings suggest that both training programs induced similar levels of exertion and physiological responses, as evidenced by the trivial effect sizes (ES) for these variables (RPE: 0.18, HRmean: 0.05, %HRmax: 0.10), with no statistically significant differences (p > 0.05). Both programs likely provided comparable intensity levels; therefore, they may be considered similar in terms of the physical demands placed on participants9. However, the perception of enjoyment was notably higher in the SSG-G than in the HC-G. This result indicates a strong preference for SSGs in terms of perceived enjoyment, confirming prior work by 9 showing that SSGs are perceived as more engaging, interactive, and motivating than structured conditioning. In line with 15, indicating that SSG might improve long-term engagement and training adherence. This suggests that the participants found the SSG to be more engaging and enjoyable than HC training, possibly because of the more interactive and game-like nature of SSGs, which may be perceived as more dynamic and fun9. This higher enjoyment may have important implications for participant adherence to training programs, as enjoyment is a key factor influencing long-term engagement and motivation2,9,28.

Limitations

There may have been a number of limitations to this study because it was carried out during the competitive season. The results of physical, technical, and psychophysiological performance could have been affected by a number of factors, including the coach’s training regimen, match preparation, tactical plans, player rotation, and individual motivation. These factors should be taken into account when interpreting the results because they might have added variability beyond the training interventions themselves. By employing standardized team schedules or off-season interventions, future research could account for these variables.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated that HC and SSG both successfully enhanced important facets of young soccer players’ physical performance. But when it came to improving sprint ability, agility, technical execution, and enjoyment, SSG training was more advantageous. SSG offers a more comprehensive and captivating method of player development by incorporating technical and physical challenges into realistic game environments. In contrast, on the other hand, HC is still useful for focusing on particular physical abilities in a regulated setting. All things considered, adding SSG to training regimens may maximize motivation, technical development, and athletic performance. Future studies should examine how both approaches might be integrated over time into periodized regimens and evaluate how player profiles affect their efficacy.

Practical contribution

The results of this study suggest that incorporating SSG into training programs can provide significant benefits in terms of physical and technical performance for young soccer players. It is recommended that coaches prioritize SSGs due to their ability to enhance key skills such as speed, agility, explosive power, and passing accuracy, while creating a dynamic and engaging training environment. Furthermore, SSGs appear to offer a higher level of enjoyment, which could enhance long-term adherence to training. In addition, HC training can be used to target specific physical and technical attributes in a more controlled setting, such as aerobic endurance, repeated sprint capacity, and individual ball-handling skills. Therefore, designing training sessions that include SSGs for holistic, match-like development and HC for focused, isolated conditioning can optimize training effectiveness while maintaining player motivation and ensuring well-rounded athlete development.

Data availability

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available for further publication because of restrictions related to the ongoing work.

References

Filter, A. et al. High-intensity actions in elite soccer: Current status and future perspectives. Int. J. Sports Med. 44, 535–544 (2023).

Ouertatani, Z. et al. Comparison of the physical, physiological, and psychological responses of high-intensity interval (HIIT) and small-sided games (SSG) training programs in young elite soccer players. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19, 13807 (2022).

Lupo, C., Ungureanu, A. N., Varalda, M. & Brustio, P. R. Running technique is more effective than soccer-specific training for improving the sprint and agility performances with ball possession of prepubescent soccer players. Biol. Sport 36, 249–255 (2019).

Dellal, A., Wong, D. P., Moalla, W. & Chamari, K. Physical and technical activity of soccer players in the French First League—With special reference to their playing position. Int. SportMed J. 11, 278–290 (2010).

Mandorino, M., Tessitore, A., Coustou, S., Riboli, A. & Lacome, M. A new approach to comparing the demands of small-sided games and soccer matches. Biol. Sport 41, 15–28 (2023).

Hoff, J., Wisløff, U., Engen, L. C., Kemi, O. J. & Helgerud, J. Soccer-specific aerobic endurance training. Br. J. Sports Med. 36, 218–221 (2002).

Zagatto, A. M. et al. The Hoff circuit test is more specific than an incremental treadmill test to assess endurance with the ball in youth soccer players. Biol. Sport 33, 263–268 (2016).

Chamari, K. et al. Endurance training and testing with the ball in young elite soccer players. Br. J. Sports Med. 39, 24–28 (2005).

Selmi, O. et al. Small-sided games are more enjoyable than high-intensity interval training of similar exercise intensity in soccer. Open Access J. Sports Med. 11, 77–84 (2020).

Trecroci, A., Boccolini, G., Duca, M., Formenti, D. & Alberti, G. Mental fatigue impairs physical activity, technical and decision-making performance during small-sided games. PLoS ONE 15, e0238461 (2020).

Sgrò, F., Bracco, S., Pignato, S. & Lipoma, M. Small-sided games and technical skills in soccer training: Systematic review and implications for sport and physical education practitioners. J. Sports Sci. 6, 9–19 (2018).

Rampinini, E. et al. Factors influencing physiological responses to small-sided soccer games. J. Sports Sci. 25, 659–666 (2007).

Clemente, F. M., Afonso, J. & Sarmento, H. Small-sided games: An umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. PLoS ONE 16(2), e0247067 (2021).

Sarmento, H. et al. Small sided games in soccer–A systematic review. Int. J. Perform. Anal. Sport 18(5), 693–749 (2018).

Selmi, O., Levitt, D. E., Aydi, B., Ferhi, W. & Bouassida, A. Verbal encouragement improves game intensity, technical aspects, and psychological responses during soccer-specific training. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 18, 758–764 (2023).

Martins, P. C. et al. Phase angle is related to 10 m and 30 m sprint time and repeated-sprint ability in young male soccer players. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18, 4405 (2021).

Vescovi, J. D. & McGuigan, M. R. Relationships between sprinting, agility, and jump ability in female athletes. J. Sports Sci. 26, 97–107 (2008).

Dellal, A. et al. Technical and physical demands of small versus large-sided games in relation to playing position in elite soccer. Hum. Mov. Sci. 31, 957–969 (2012).

Owen, A. L., Wong, D. P., McKenna, M. & Dellal, A. Heart rate responses and technical comparison between small- vs. large-sided games in elite professional soccer. J. Strength Cond. Res. 25, 2104–2110 (2011).

Selmi, O., Marzouki, H., Ouergui, I., Ben Khalifa, W. & Bouassida, A. Influence of intense training cycle and psychometric status on technical and physiological aspects performed during small-sided games in soccer players. Res. Sports Med. 26, 401–412 (2018).

Selmi, O. et al. Influence of well-being indices and recovery state on the technical and physiological aspects of play during small-sided games. J. Strength Cond. Res. 35, 2802–2809 (2021).

Kelly, D. M. & Drust, B. The effect of pitch dimensions on heart rate responses and technical demands of small-sided soccer games in elite players. J. Sci. Med. Sport 12(4), 475–479 (2009).

Foster, C. et al. A new approach to monitoring exercise training. J. Strength Cond. Res. 15, 109–115 (2001).

Fanchini, M. et al. Use of the CR100 scale for session rating of perceived exertion in soccer and its interchangeability with the CR10. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 11, 388–392 (2016).

Hopkins, W., Marshall, S., Batterham, A. & Hanin, J. Progressive statistics for studies in sports medicine and exercise science. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 41, 3. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e31818cb27819092709 (2009).

Michał, T. B. et al. Effects of two low-volume high-intensity interval training protocols in professional soccer: Sprint interval training versus small-sided games. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 63, 23–33 (2023).

Clemente, F. M., Ramirez-Campillo, R., Afonso, J. & Sarmento, H. Effects of small-sided games vs running-based high-intensity interval training on physical performance in soccer players: A meta-analytical comparison. Front. Physiol. 12, 642703 (2021).

Los Arcos, A. et al. Effects of small-sided games versus interval training in aerobic fitness and physical enjoyment in young elite soccer players. PLoS ONE 10, e0137224 (2015).

Salazar-Martinez, J., Valencia-Sanchez, W. G. & Clemente, F. M. Comparative impact of small-sided games and high-intensity interval training on physical performance in youth soccer players. J. Phys. Educ. Sport 23, 2769–2785 (2023).

Theocharis, K. et al. The effect of a four-week mesocycle with small-sided games on the agility and sprinting ability of professional soccer players during in-season. J. Phys. Educ. Sport 23, 1449–1455 (2023).

Paprancová, A., Šimonek, J., Paška, L. U. & Krčmár, M. Impact of small-sided games and running-based high-intensity interval training on physical performance in female football players. J. Phys. Educ. Sport 24, 113–122 (2024).

Iacono, A. D., Beato, M. & Unnithan, V. Comparative effects of game profile–based training and small-sided games on physical performance of elite young soccer players. J. Strength Cond. Res. 35, 2810–2817 (2021).

Hammami, A., Gabbett, T. J., Slimani, M. & Bouhlel, E. Does small-sided games training improve physical fitness and specific skills for team sports? A systematic review with meta-analysis. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fitness 58, 1446–1455 (2018).

Faude, O., Roth, R., Di Giovine, D., Zahner, L. & Donath, L. Combined strength and power training in high-level amateur football during the competitive season: A randomised-controlled trial. J. Sports Sci. 31(13), 1460–1467 (2013).

Daryanoosh, F. et al. Effect of interval and continuous small-sided games training on the bio-motor abilities of young soccer players: A comparative study. BMC Sports Sci. Med. Rehabil. 15, 51 (2023).

Clemente, F. M. et al. Effects of small-sided game interventions on the technical execution and tactical behaviors of young and youth team sports players: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Psychol. 12, 667041 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We extend our gratitude to the participants for their invaluable contributions to this study. Special thanks to the Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2026R286), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Funding

This research was funded by Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2026R286), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MAR, OS, AB, and DIA contributed to the conception of the study. MIA, SB, AMC, MȘ, CIA contributed to the data curation. Formal analysis was made by MAR, OS, DIA and MȘ. MAR, AB and SB carried out the investigation. MAR, DIA, AB, OS and AMC aimed at complying with the methodology, while the project administration was carried out by DIA and MIA. MȘ and AMC took care of securing the resources, for software activity OS, DIA, MȘ, AMC and CIA were involved, while supervision was the objective of AB, MAR and DIA. Writing - original draft was the task of MAR, AB, OS and DIA, while for writing - review & editing and for validation MAR, AB, MIA, AMC, MȘ and CIA were involved. Funding acquisition was made by MIA. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, manuscript writing, or decision to publish the results.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

All procedures and research protocols in this study involving human participants were approved by the ethical standards of the Research Ethics Committee of the High Institute of Sports and Physical Education of Kef (approval number: 013/2023; approval date: April 18, 2023). Written Informed consent was obtained from each participant, which was a condition for enrolment in the study, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Clinical trial registration

Clinical trial number is not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rahmoune, M.A., Selmi, O., Bouali, S. et al. Effects of small-sided games and dribbling circuit training on physical and technical skills in youth soccer players. Sci Rep 16, 1731 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31382-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31382-7