Abstract

Diet may influence early biological processes involved in colorectal carcinogenesis. Red and processed meat intake has been associated to increased colorectal cancer (CRC) risk, potentially through heme-driven oxidative and genotoxic mechanisms. This 12-week behavioral, free-living, randomized, open-label study evaluated how three different diets impact CRC risk markers: a meat-based diet (MBD: high risk), a meat-based diet with α-tocopherol supplementation (MBD-T: medium risk, hypothesized to attenuate heme-induced oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation), and a pesco-vegetarian diet (PVD: low risk). A total of 113 healthy adults (18–50 years) were randomized, and 103 completed the study. The primary outcome was fecal water (FW) genotoxicity at baseline and after 12 weeks; secondary outcomes included FW cytotoxicity, lipoperoxidation, fecal short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) and bile acids, and blood biomarkers related to iron metabolism and inflammation, also measured pre- and post-intervention. Mixed-effects linear models (time × diet), adjusted for age, sex, and BMI, were applied. FW genotoxicity increased significantly after MBD (+ 15.97%DNA damage; 95% CI 4.61 to 27.32; p = 0.006), with no significant within-group changes in MBD-T or PVD. Between-diet differences in change indicated greater increases in fecal TBARS following MBD (p = 0.010) and MBD-T (p = 0.037) compared with PVD, and a significantly greater increase in 4-HNE after MBD compared with PVD (p = 0.019). The FW Viability Index decreased significantly after MBD (p = 0.021). Differences in change between diets were also significant for circulating ferritin and inflammatory markers, which increased more after MBD compared with PVD (ferritin, IL-6, TNF-α), whereas MBD-T reduced TNF-α and PVD decreased IL-8, TNF-α, and ICAM. No significant between-diet differences in change were observed for fecal SCFAs or bile acids. In summary, over 12 weeks in a free-living setting, a MBD increased several mechanistic biomarkers associated with CRC, while α-tocopherol supplementation attenuated some adverse diet-related effects. In contrast, a PVD was associated with a more favorable biochemical and inflammatory profile. These findings reflect short-term modulation of mechanistic biomarkers rather than CRC outcomes.

Trial Registration: ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03416777. Registered 03/05/2018.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths in Europe, with a rising incidence among young adults1. This trend highlights the urgent need for preventive strategies. Environmental factors, particularly dietary habits, are substantial contributors to CRC incidence, with evidence associating increased risk to red and processed meat consumption and decreased risk to dietary fibre intake2,3,4.

The mechanisms linking meat to CRC remain unclear. Processed meats contain sodium, nitrites, and nitrates5, while high-temperature cooking of red meat produces harmful compounds such as N-nitroso compounds, heterocyclic amines, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, and advanced glycation-end products6. Additionally, heme iron may promote the formation of lipid peroxidation products and N-nitroso compounds in the colon7,8,9. The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) classifies processed meat as carcinogenic (Group 1) and red meat as probably carcinogenic (Group 2A) to humans. Given this established evidence, the rationale for the present study was not to re-evaluate the carcinogenic potential of meat, but to investigate whether specific dietary interventions can modulate mechanistic pathways involved in colorectal carcinogenesis. In fact, although observational findings on meat intake and CRC risk vary in magnitude10,11,12,13,14,15, human dietary intervention studies examining mechanistic biomarkers in vivo remain scarce, underscoring the need for experimental research to clarify underlying biological mechanisms13,16,17.

This randomized behavioral intervention assessed three diets associated with differing levels of CRC risk in healthy adults: a high-risk meat-based diet (MBD; high heme exposure), a medium-risk meat-based diet supplemented with α-tocopherol (MBD-T), and a low-risk pesco-vegetarian diet (PVD). α-Tocopherol was included in MBD-T as a lipid-phase antioxidant to counteract heme-induced lipid peroxidation18,19,20, whereas PVD was selected for its established health benefits and the potential protective effects of fish against CRC21,22. We investigated whether these dietary patterns differentially modulate biomarkers linked to CRC risk, focusing on fecal water (FW) genotoxicity, lipid peroxidation, and inflammatory signaling.

Materials and methods

Study design and population

The study protocol has been published elsewhere23. Briefly, clinically healthy participants were recruited and randomized to a 12-week behavioral, free-living, open-label parallel dietary intervention trial through advertisements on local and social media, newspapers, and official websites from the Unit of Clinical Nutrition of Careggi University Hospital, Florence, Italy, from September 2019 to December 2021, with a temporary interruption during Italy’s first Covid-19 wave (March–September 2020). Given that the risk of CRC significantly increases after age 50, and our aim was CRC prevention, the study targeted adults aged 18 to 50, focusing on a population before the typical onset age of CRC. Exclusion criteria included the presence of serious or unstable health conditions, food allergies, recent use of antibiotics or probiotics (within the last 2 months), pregnancy or breastfeeding, smoking, and adherence to any diet that restricted meat, poultry, or fish consumption in the preceding 3 months.

Trial findings were reported using the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guideline and statement and International Committee of Medical Journal Editors recommendations. The trial was approved by the Ethics Committee (12390_spe; 01/03/2018) of the Tuscany Region, Careggi University Hospital, which is equivalent to the Institutional Review Board. It was registered on 03/05/2018 on Clinicaltrials.gov (identifier: NCT03416777) and adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and the Data Protection Act. Informed consent was obtained from the participants. They received no financial support.

Dietary interventions

This was a free-living, behavioral dietary intervention in which participants prepared their own meals according to individualized menus and received structured nutritional counseling. A 2-week run-in period was implemented to assess motivation and collect baseline dietary intake.

Following the 2-week run-in period, participants were randomly assigned using a 1:1:1 ratio to a 12-week dietary intervention with MBD, MBD-T, or PVD through a web-based randomization procedure. The random allocation sequence was generated and managed by a scientist who was not involved in participant recruitment. The sequence was concealed from investigators enrolling participants or assigning interventions. Group assignments were revealed using folded papers in sealed envelopes. During the run-in period, each participant was asked to complete a 3-day (2 weekdays and 1 weekend day) weighted dietary record. Data were entered in the Metadieta software application (Me.Te.Da., San Benedetto del Tronto, Italy) by trained personnel, carefully checked for errors, and then analyzed to obtain energy and nutrient (e.g., carbohydrates, fat, protein) intake at baseline for each participant. During the study, 2 clinical assessments were performed: at baseline (T0) and 3 months after the start of the dietary interventions (T1). Participants were instructed to alter only their diet in line with the intervention guidelines, while maintaining their usual lifestyle and exercise habits throughout the study. To ensure that potential lifestyle or health changes did not confound the results, physical activity, alcohol consumption, illnesses, and medication use were also monitored throughout the study through structured questionnaires administered at both time points.

Dietary interventions were delivered through individual face-to-face counselling sessions at the Clinical Nutrition Unit, Careggi University Hospital, Florence, Italy. Each participant received a menu plan for one week at the beginning of the intervention, as well as detailed instructions and examples of permitted and excluded food groups. A follow-up call was conducted during the study as part of the compliance assessment to reinforce adherence and address potential challenges. Participants were also encouraged to contact the study personnel at any time for clarification or support regarding their dietary plan. Participants were provided with a detailed menu plan for one week, as well as advice and information on the food groups that could be included and those that could not. The diets were isocaloric with respect to the energy needs of the participants and consisted of about 30% of energy from total fat, 15–20% from protein, and 50–55% from carbohydrates (mainly complex). The MBD included 4 weekly servings of red meat (1 serving = 150 g), 3 weekly servings of processed meat (1 serving = 50 g), and 1 weekly serving of poultry (1 serving = 150 g), for a total of 900 g per week of meat. The MBD-T was like the MBD but supplemented with 100 mg/day of α-tocopherol. All participants in the MBD-T group received blister packs with α-tocopherol capsules (EVION, Bracco S.p.A., 100 mg) for the entire intervention period, totaling 90 tablets over 3 months. The PVD excluded fresh and processed meat and poultry but included 3 servings per week of fish (1 serving = 150 g), excluding shellfish, for a total amount of 450 g per week. The diets contained other sources of proteins (e.g., eggs, dairy products, legumes/beans) and were calculated based on the Italian Recommended Dietary Allowances servings24 (Supplementary Table 1). Alcoholic beverages were not included in the diets administered. For subjects that requested to drink alcoholic beverages, the amounts were limited to one unit of alcohol (12 g of ethanol) per day for women and two per day for men, according to the Italian Recommended Dietary Allowances servings24. There were no substantial differences among diets in the frequency of weekly servings of cereals, vegetables, potatoes, fruit, sweets, and olive oil. However, there was a higher frequency of weekly consumption of legumes (4 servings vs. 2 servings) and dairy products (7 servings vs. 5 servings) in PVD than in MBD and MBD-T.

Data collection

Data collection and follow-up assessments were carried out at the Unit of Clinical Nutrition, Careggi University Hospital, Florence, Italy, by study staff. All participants were examined between 6.30 am and 9.30 am after an overnight fast. They were asked not to engage in strenuous physical activity the day before the examination. The baseline assessment included a standardized questionnaire on demographic information and risk factors. Additionally, the Medi-Lite adherence score was used to measure diet quality at baseline, quantifying adherence to the Mediterranean diet (MD)25. All participants were asked to report the frequency (times per week), duration (months), and intensity of recreational and physical activities performed during the preceding year. Based on these variables, a physical activity grade was derived for each participant and described in terms such as “absent” or “light” (i.e., inactive, or either occasional walking or recreational activity only), and “moderate” (i.e., frequent recreational activity, regular walking for 30 min 3–5 times per week, or sporting exercise at least once a week). The grade was a qualitative measure of how much physical activity was undertaken.

Body weight and body composition were measured both at the beginning and end of the dietary interventions. Weight and height were measured with a stadiometer. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters. Participants were classified as overweight if their BMI was ≥ 25 kg/m2 but < 30 kg/m2 and obese if their BMI was ≥ 30 kg/m226. Body composition was determined by a bioelectrical impedance analysis device (AKERN, model SE 101) at baseline and follow-up visits. Blood, stool (four or five scoops totaling 4 g), and urine samples were collected before and after each intervention phase.

Compliance

Compliance to the dietary interventions was assessed through unannounced phone calls, during which a 24-h diet recall interview was conducted, and through a medium-length Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) validated in the Italian population27, with the aim of confirming the frequency of meat and fish consumption. These tools were used to verify adherence to the prescribed dietary patterns, with particular attention to the inclusion or exclusion of meat and fish. Compliance with the MBD was defined as the consumption of at least 7 servings per week of red and processed meat and the complete exclusion of fish, as reported in both the 24-h recalls and the FFQ. Compliance with the PVD was defined as the consumption of at least 3 servings per week of fish combined with the exclusion of red and processed meat. For the MDB-T group, adherence to the therapeutic regimen was assessed by collecting the empty blister packs returned by the participants. Total energy intake and macronutrient distribution, as well as sugar and alcohol intakes, were also monitored to evaluate adherence to the prescribed dietary plans via the same recalls. Moreover, physical activity, illnesses, and medication use were checked through questionnaires at both time points and through two phone contacts to detect any relevant changes during the intervention period.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was fecal water (FW) genotoxicity, i.e. changes in DNA damage (strand breaks) induced in vitro in human colon cancer cells (HT-29 line) exposed to subjects’ FW, sampled before (baseline) and after the nutritional intervention. FW genotoxicity reflects DNA strand breaks induced by the colonic milieu and is used in human dietary intervention studies, being responsive in preclinical models linked to colorectal tumor modulation28,29,30,31. The metric used was changes in means from Time 0 to Time 1. Secondary outcomes were changes in means of the following parameters from the baseline: a) cytotoxicity of FW; b) markers of global peroxidation and specific peroxidation of omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids in FW; c) markers of lipid peroxidation in urine samples; d) short chain fatty acids (SCFAs) and bile acids production; e) biochemical profile including lipid and glucose profiles, renal function, iron metabolism, vitamin levels, and inflammatory markers in blood samples. Secondary markers capture complementary pathways: lipid peroxidation as indices of heme-driven oxidative injury32,33; SCFAs and bile acids for microbial/epithelial homeostasis and oxidative stress/DNA damage34,35,36,37; and iron/inflammatory indices relevant to red-meat exposure and carcinogenesis8,38,39,40. These biomarkers are interpreted as mechanistic risk-related markers, not validated clinical surrogates of CRC incidence. Potential harms were defined and assessed non-systematically.

Experimental analyses

Detailed methodologies for assessing the genotoxic and cytotoxic activity of FW, lipid peroxidation, fecal SCFA and bile acid analysis, as well as the biochemical profile, iron metabolism, and inflammatory markers, are provided in the Supplemental Material. In brief, FW genotoxicity and cytotoxicity were evaluated in HT-29 colon cells using the Comet assay and Trypan Blue exclusion test, respectively, with PBS-treated and NQO-treated controls for quality assurance. Markers of lipid peroxidation were quantified in fecal water and urine samples by UHPLC-MS/MS (4-HNE) and enzyme immunoassays (urinary DHN-MA and 8-isoprostane), each including internal standards and QC samples. SCFAs and bile acids were measured in fecal samples using GC–MS and HPLC–MS/MS, respectively, identified by retention times and mass reference standards. Blood biomarkers, including biochemical, iron, and inflammatory parameters, were analyzed following standardized protocols, with cytokines quantified by Bio-Plex multiplex immunoassay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, USA).

Statistical analysis

The study was originally designed to have a statistical power of 80% (beta) and α = 0.05 to detect a 25% change in fecal genotoxicity, the predefined primary outcome of the study23. This value was determined based on a study previously conducted to test the effect of a dietary intervention on FW-induced DNA damage assessed by the Comet assay41.

Data were summarized as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median (range: minimum–maximum), as appropriate. Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages. The normality of distributions and homogeneity of variances were assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk and Levene tests, respectively. Variables showing markedly skewed distributions were log-transformed prior to analysis to approximate normality and back-transformed values are reported for interpretability. Prior to the main analyses, the level, pattern, and likely causes of the missingness in the baseline variables and outcomes were investigated by forming appropriate tables. This information was used to determine whether the level and type of missing data have the potential to introduce bias into the analysis results or substantially reduce the precision of estimates for the proposed statistical methods. Differences between completers and non-completers were analyzed using independent samples t-tests for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables. Changes in dietary intake across intervention groups were evaluated using one-way ANOVA.

Mixed-effects linear models were used to evaluate both within-group changes (pre–post) and between-group differences in change across the three dietary interventions. Each outcome variable was modeled separately, with Time (pre-intervention; post-intervention) specified as a within-subject fixed effect and Intervention (PVD; MBD; MBD-T) as a between-subject fixed effect. The Time × Intervention interaction term was included to assess differential changes among diets (difference-in-change). A random intercept for participant was specified to account for repeated measures within individuals. All models were adjusted for age, sex, and baseline BMI as covariates, selected a priori based on previous evidence41. Physical activity, alcohol intake, illnesses, and medication were monitored throughout the study, but as no relevant between-group differences were observed, these variables were not included as covariates. Parameters were estimated using restricted maximum likelihood (REML) with an unstructured covariance matrix for random effects. Estimated marginal means (EMMEANS) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were computed for each diet × time combination. Pairwise contrasts were performed to obtain within-group changes and between-diet differences in change. To control for multiple comparisons across secondary outcomes, p-values from the between-diet difference-in-change contrasts were adjusted using the Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) correction. However, reported p-values for secondary outcomes should be interpreted descriptively, in conjunction with effect sizes and consistency across biomarkers. Analyses followed a per-protocol approach (n = 103). For SCFAs and bile acids, within-diet effects were tested with the Wilcoxon signed-rank test and between-group differences with the Mann–Whitney test. Potential correlations between changes in FW genotoxicity and changes in iron levels in diet, biochemical, inflammatory, and global and specific peroxidation parameters were examined using Pearson coefficients. All analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics for Macintosh, version 30.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and Python (statsmodels v0.14). Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05 (two-sided).

Results

Characteristics of study population at baseline

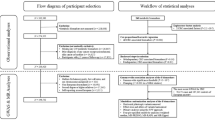

Figure 1 shows the enrollment of participants in the study. Initially, 134 subjects were screened for eligibility, among whom 113 (33 males, 80 females; median age: 39 years) were included and randomized into the three dietary intervention groups. Of these, 103 successfully completed the study, with 33 participants completing the MBD and MBD-T interventions each, and 37 completing the PVD intervention. The overall participation rate was 91%. All participants who completed the study were included in the analysis. The baseline characteristics of the population are shown in Table 1. The analysis of subjects who dropped out of the study during the intervention showed no significant differences in terms of baseline characteristics compared to subjects who completed the study (Supplementary Table 2).

Changes in dietary intakes

Changes in dietary intake were assessed using 3-day weighted dietary records, which showed no significant differences in total daily energy intake among groups and no significant between-group differences in macronutrient composition (Supplementary Table 3). All three interventions resulted in a reduction in the percentage of energy derived from fat and an increase in fibre intake. Significant between-group differences were detected for total cholesterol (p = 0.009), saturated fat (p < 0.001), and iron intake (p < 0.001). No unintended effects have been reported.

Changes in FW genotoxicity

Changes in FW genotoxicity parameters from baseline to week 12 for each diet, and the between-diet differences in these changes, are shown in Fig. 2. Compared with baseline, DNA damage significantly increased in participants following the MBD (+ 15.97%DNA damage, 95% CI 4.61 to 27.33; p = 0.006), whereas no significant within-group changes were detected in the MBD-T or PVD groups. Between-group comparisons indicated a trend toward greater increases in DNA damage (i.e., larger differences in change) with MBD compared with both PVD and MBD-T, although these differences did not reach statistical significance.

Within-group changes (Panel A) and between-group difference in change (Panel B) in FW genotoxicity, expressed as percentage of DNA in tail (% DNA damage) as determined by the Comet Assay, after 12 weeks on each diet. Diamonds represent estimated marginal means with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), derived from mixed-effects linear models adjusted for age, sex, and baseline BMI, including a diet × time interaction term and a random intercept for participant. Reported p-values refer to within-group (pre–post) changes (Panel A) and between-group (difference-in-change) contrasts (Panel B). MBD, meat-based diet; MBD-T, meat-based diet supplemented with α-tocopherol; PVD, pesco-vegetarian diet.

Changes in markers of colorectal cancer, SCFAs, and bile acids

Changes in FW cytotoxicity and oxidative stress markers are presented in Fig. 3. Between-diet comparisons revealed significant differences in TBARS levels, which increased more markedly following the MBD (+ 23.03 µM, 95% CI 5.45 to 40.60; p = 0.010) and MBD-T (+ 20.06 µM, 95% CI 1.17 to 38.95; p = 0.037) compared with PVD. Similarly, the increase in 4-HNE concentrations (difference in change) was significantly greater after MBD compared with PVD (+ 6.13 pg/µl, 95% CI 1.01 to 11.26; p = 0.019). Heme iron showed an opposite, albeit non-significant, direction of change, increasing in the MBD and MBD-T groups but decreasing in the PVD group. Within-group analyses showed that the FW Viability Index decreased significantly after the MBD intervention (p = 0.021). No significant pre-post changes were observed in total or individual fecal SCFAs or bile acids (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Within-group and between-group changes in cytotoxic activity of FW and markers of global and specific peroxidation measured in FW (TBARS, 4-HNE, heme iron) or in urine (DHN-MA and isoprostanes) after 12 weeks on each diet. Estimated marginal means and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) derived from mixed-effects linear models adjusted for age, sex, and baseline BMI, including a diet × time interaction term and a random intercept for participant. Reported p-values refer to between-group (difference-in-change) contrasts and were corrected for multiple testing using the Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) procedure. Asterisks (*) indicate significant within-group (pre–post) changes at p < 0.05. MBD denotes meat-based diet, MBD-T meat-based diet supplemented with α-tocopherol, PVD pesco-vegetarian diet, TBARS thiobarbituric acid reactive substances, 4-HNE 4-Hydroxynonenal, DHN-MA dihydroxynonane mercapturic acid.

Changes in biochemical and inflammatory profile

Changes in biochemical and inflammatory parameters from baseline to week 12 for each diet, and the corresponding between-diet differences in change, are reported in Table 2. Between-diet differences in change were significant for ferritin, which increased to a greater extent in both the MBD (+ 16.18 ng/ml, 95% CI 6.66 to 25.69; p = 0.027) and MBD-T (+ 16.78 ng/ml, 95% CI 7.27 to 26.30; p = 0.025) groups compared with PVD. Differences in change were also significant for IL-6 (+ 1.36 pg/ml, 95% CI 0.35 to 2.36; p = 0.008) and TNF-α (+ 1.33 pg/ml, 95% CI 0.67 to 1.98; p = 0.007), both of which increased more after MBD compared with PVD. Within-group analyses indicated significant increases in plasma triglycerides following MBD (p = 0.04) and MBD-T (p = 0.008), and in circulating iron after MBD (p = 0.029) and MBD-T (p = 0.019). Conversely, PVD led to a significant reduction in ferritin (p < 0.001) and an increase in folic acid levels (p = 0.020). Regarding inflammatory markers, MBD was associated with increased VEGF (p = 0.038) and IL-6 (p = 0.052). MBD-T, on the other hand, resulted in a reduction in TNF-α (p = 0.016), while PVD led to significant decreases in IL-8 (p < 0.001), TNF-α (p < 0.001), and ICAM (p = 0.037).

Correlation analysis

Correlation analyses between changes in FW genotoxicity and changes in iron levels in diet, blood and feces showed a small but significant correlation with iron (R = 0.29, p = 0.006) and ferritin (R = 0.39, p < 0.001) levels in blood (Supplementary Fig. 2). No significant correlations were observed for all other biochemical, inflammatory, and global and specific peroxidation parameters evaluated. No adverse or unexpected events were observed in either group.

Discussion

This study explored how dietary patterns differing in red meat content affect biomarkers linked to CRC risk. After 3 months, the increase in FW genotoxicity was significantly greater in MBD compared with PVD, accompanied by higher plasma and fecal iron and lipid peroxidation markers. Compared with MBD, α-tocopherol supplementation in MBD-T attenuated these changes, and PVD showed lower TBARS and inflammatory markers (IL-8, VEGF), indicating more favorable modulation of risk-related biomarkers. These results align with our previous preclinical study in rat models showing the carcinogenic potential of red meat and the protective effects of fish- and plant-based diets against CRC42.

Epidemiological data have linked red and processed meat consumption to increased CRC risk43,44,45, potentially through enhanced genotoxic stress in the colon28,29. However, clinical evidence remains limited. Our results support a red meat-related increase in FW genotoxicity, in contrast to Joosen et al.30, who reported no significant genotoxicity differences between diets varying in meat and fish, likely due to their short (8-day) intervention and small sample size (n = 14). In contrast, other short-term studies with similar sample sizes (n = 12) and red meat exposure (7 days) did observe increased FW genotoxicity31, without changes in fecal N-nitroso compounds (NOCs). Similarly, a crossover study with 20 healthy males consuming 240 g/day of red and processed meat for 2 weeks showed a significant increase in FW genotoxicity compared to a mycoprotein diet46.

Between-diet contrasts confirmed greater increases in fecal TBARS following both meat-based diets compared with PVD, consistent with higher fecal heme iron exposure in the MBD. Heme iron catalyzes lipid peroxidation, generating aldehydes such as malondialdehyde (MDA), which can be detected as TBARS33,47. Elevated heme iron can also promote reactive oxygen species, lipid peroxidation end-products, and NOCs – agents implicated in CRC development by inducing DNA damage, colonic hyperproliferation, outgrowth of (pre)neoplastic cells, immune modulation, and gut dysbiosis38,39. A meta-analysis by Bastide et al.40 involving over 566,000 individuals found a relative risk of 1.18 (95% CI: 1.06–1.32) for CRC in those with the highest heme iron intake. Furthermore, experimental models show that dietary hemoglobin and red meat promote preneoplastic lesions40. Our correlation analysis indicated a small but significant link between iron biomarkers (serum iron, ferritin) and FW genotoxicity, warranting further investigation.

Regarding peroxidation markers, 4-HNE concentrations increased more after the MBD compared with PVD, whereas urinary DHN-MA levels remained unchanged. Although DHN-MA has been proposed as a non-invasive biomarker of preneoplastic risk associated with heme iron intake32, its specificity is limited because its precursor, 4-HNE, is present in various foods such as fish, oils, and fried items48. The concurrent increase in iron accumulation, lipid peroxidation, and inflammation, partially attenuated by α-tocopherol, may reflect ferroptosis-related oxidative injury mechanisms, an emerging process characterized by iron-dependent lipid peroxidation and increasingly recognized as a potential pathway in colorectal carcinogenesis, providing a unifying framework for our observations49.

SCFA levels did not significantly change across interventions. Although red meat-rich diets have been linked to reduced SCFA production due to lower fiber intake34,50, our study design maintained consistent fruit and vegetable consumption across groups, potentially explaining the stable SCFA levels. Similarly, bile acid levels remained unchanged, suggesting they may not be primary contributors to fecal genotoxic load. Previous studies show conflicting results: some indicate bile acids can induce oxidative stress and DNA damage35,36,37, while others found no association or even a reduction following high meat intake46,51.

Finally, given the alterations in cholesterol, unsaturated, and saturated fatty acids intake resulting from the inclusion or exclusion of meat and fish in the diet, we extended our analysis to assess the biochemical profile, including lipid profile, and inflammatory parameters. Between-diet comparisons showed that ferritin, IL-6, and TNF-α increased more after the MBD compared with the PVD, indicating higher iron storage and inflammatory activation with greater meat intake. α-Tocopherol supplementation in MBD-T partially attenuated these responses, while PVD was associated with reductions in ferritin and several inflammatory markers, including IL-8 and ICAM, consistent with a more favorable anti-inflammatory profile. While red meat consumption has been linked to inflammation in populations at cardiometabolic risk52, its association with lipid profiles is debated. Meta-analyses suggest red meat may not consistently raise serum lipids compared to poultry or fish53,54. Similarly, while some studies have reported that high fish intake reduces triacylglycerol levels and increases HDL-cholesterol serum concentrations55, others found no significant effects51. These discrepancies may stem from differences in participant profiles and comparison diets. Moreover, while LDL-cholesterol is causally linked to cardiovascular risk, dietary impacts are complex and extend beyond traditional lipid markers. As such, patient-oriented outcomes should be prioritized.

Several limitations must be acknowledged. Firstly, the temporary interruption of the study during the Covid-19 pandemic led to recruitment challenges, resulting in an incomplete total number of planned subjects. Secondly, the study’s short intervention (12 weeks) and age-restricted cohort (18–50 years) may limit generalizability, particularly to older populations at higher CRC risk. Nonetheless, targeting younger adults aligns with prevention goals. Thirdly, this was a free-living study without controlled feeding, and although compliance was high, exposure variability is unavoidable. Reliance on self-reported dietary data, despite efforts to ensure compliance, introduces the potential for recall bias. Future studies should incorporate objective dietary biomarkers to improve accuracy. In addition, although FW genotoxicity is a well-established surrogate in dietary CRC studies28,41,56,57, human validation remains limited. Its predictive value in rodent models58 and biological plausibility, given DNA damage’s role in carcinogenesis59, support its relevance as a CRC risk marker. Indeed, DNA strand breaks detected through FW genotoxicity are biologically meaningful as early indicators of genomic instability, a key event in colorectal carcinogenesis. Nevertheless, these biomarkers have not been validated as surrogate endpoints for CRC, and the findings should therefore be interpreted as reflecting modulation of mechanistic, risk-related biomarkers rather than evidence of reduced cancer risk. Finally, secondary outcomes were exploratory and should be interpreted as such. Despite these limitations, the study’s strengths include its randomized design, the largest participant cohort and follow-up to date for this type of clinical study, and a comprehensive analysis of genotoxicity, peroxidation, biochemical, and inflammatory outcomes. The inclusion of a PVD arm allowed clear comparisons between high- and low-risk dietary patterns.

In conclusion, the findings of this study suggest that a MBD may exert a detrimental effect on mechanistic biomarkers associated with CRC risk within a relatively short time frame. These adverse effects appear to be attenuated by concurrent intake of α-tocopherol, while the PVD diet demonstrated more favorable modulation of oxidative and inflammatory markers. However, these outcomes represent short-term changes in mechanistic biomarkers rather than validated clinical endpoints, and should not be interpreted as evidence of altered cancer risk. These findings lay the groundwork for future research aimed at elucidating the molecular pathways linking diet to colorectal carcinogenesis and assessing whether sustained biomarker modulation translates into reduced disease risk.

Data availability

The datasets analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Sung, H. et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 71, 209–249. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21660 (2021).

Demeyer, D., Mertens, B., De Smet, S. & Ulens, M. Mechanisms linking colorectal cancer to the consumption of (processed) red meat: A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 56, 2747–2766. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2013.873886 (2016).

World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. Continuous update project expert report 2018. Recommendations and public health and policy implications. https://www.wcrf.org/diet-and-cancer/ (2018)

Di, Y., Ding, L., Gao, L. & Huang, H. Association of meat consumption with the risk of gastrointestinal cancers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cancer 23, 782. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-023-11218-1 (2023).

Crowe, W., Elliott, C. T. & Green, B. D. A review of the in vivo evidence investigating the role of nitrite exposure from processed meat consumption in the development of colorectal cancer. Nutrients 11, 2673. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11112673 (2019).

Martínez Góngora, V., Matthes, K. L., Castaño, P. R., Linseisen, J. & Rohrmann, S. Dietary heterocyclic amine intake and colorectal adenoma risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 28(1), 99–109. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-17-1017 (2019).

Bouvard, V. et al. International agency for research on cancer monograph working group. Carcinogenicity of consumption of red and processed meat. Lancet Oncol. 16, 1599–1600. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00444-1 (2015).

Bastide, N. M. et al. A central role for heme iron in colon carcinogenesis associated with red meat intake. Cancer Res. 75, 870–879. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-2554 (2015).

Sasso, A. & Latella, G. Role of heme iron in the association between red meat consumption and colorectal cancer. Nutr. Cancer. 70, 1173–1183. https://doi.org/10.1080/01635581.2018.1521441 (2018).

Stern, M. C. et al. Genome-wide gene-environment interaction analyses to understand the relationship between red meat and processed meat intake and colorectal cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 33, 400–410. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-23-0717 (2024).

Turner, N. D. & Lloyd, S. K. Association between red meat consumption and colon cancer: A systematic review of experimental results. Exp. Biol. Med. (Maywood). 242, 813–839. https://doi.org/10.1177/1535370217693117 (2017).

Zeraatkar, D. et al. Effect of lower versus higher red meat intake on cardiometabolic and cancer outcomes: A systematic review of randomized trials. Ann. Intern. Med. 171, 721–731. https://doi.org/10.7326/M19-0622 (2019).

Lescinsky, H. et al. Health effects associated with consumption of unprocessed red meat: A burden of proof study. Nat. Med https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-022-01968-z (2022).

Cheung, H. S. et al. Association of red meat intake and colorectal cancer among east-Asians: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies performed between 2011–2021. J Gastrointestin. Liver Dis. 32, 377–383. https://doi.org/10.15403/jgld-4778 (2023).

Van Blarigan, E. L. et al. Associations between unprocessed red meat and processed meat with risk of recurrence and mortality in patients with stage III colon cancer. JAMA Netw. Open. 5, e220145. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.0145 (2022).

Stanton, A. V. et al. 36-fold higher estimate of deaths attributable to red meat intake in GBD 2019: Is this reliable?. Lancet 399, e23–e26. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00311-7 (2022).

Gordon-Dseagu, V. L. Z., Wiseman, M. J., Allen, K., Buttriss, J. & Williams, C. Troubling assumptions behind GBD 2019 on the health risks of red meat. Lancet 400, 427–428. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01283-1 (2022).

Pierre, F. H. et al. Calcium and α-tocopherol suppress cured-meat promotion of chemically induced colon carcinogenesis in rats and reduce associated biomarkers in human volunteers. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 98, 1255–1262. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.113.061069 (2013).

Bastide, N. M. et al. Red wine and pomegranate extracts suppress cured meat promotion of colonic mucin-depleted foci in carcinogen-induced rats. Nutr. Cancer. 69, 289–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/01635581.2017.1263745 (2017).

Diallo, A. et al. Dietary iron intake and breast cancer risk: Modulation by an antioxidant supplementation. Oncotarget 7, 79008–79016. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.12592 (2016).

Caini, S. et al. Fish consumption and colorectal cancer risk: Meta-analysis of prospective epidemiological studies and review of evidence from animal studies. Cancers 14, 640. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14030640 (2022).

Poorolajal, J., Mohammadi, Y., Fattahi-Darghlou, M. & Almasi-Moghadam, F. The association between major gastrointestinal cancers and red and processed meat and fish consumption: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the observational studies. PLoS ONE 19, e0305994. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0305994 (2024).

Sofi, F. et al. Fecal microbiome as determinant of the effect of diet on colorectal cancer risk: Comparison of meat-based versus pesco-vegetarian diets (the MeaTIc study). Trials 20, 688. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-019-3801-x (2019).

Livelli di Assunzione di Riferimento di Nutrienti e Energia per la popolazione Italiana (LARN). Società Italiana di Nutrizione Umana (SINU). IV revisione.

Sofi, F., Dinu, M., Pagliai, G., Marcucci, R. & Casini, A. Validation of a literature-based adherence score to Mediterranean diet: the MEDI-LITE score. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 68, 757–762. https://doi.org/10.1080/09637486.2017.1287884 (2017).

Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults: executive summary. Expert Panel on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight in Adults. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1998; 68: 899–917. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/68.4.899. PMID: 9771869.

Buscemi, S. et al. Validation of a food frequency questionnaire for use in Italian adults living in Sicily. Int. J. Food Sci Nutr. 66, 426–438. https://doi.org/10.3109/09637486.2015.1025718 (2015).

Hughes, R., Pollock, J. R. & Bingham, S. Effect of vegetables, tea, and soy on endogenous N-nitrosation, fecal ammonia, and fecal water genotoxicity during a high red meat diet in humans. Nutr. Cancer. 42, 70–77. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327914NC421_10 (2002).

Pearson, J. R., Gill, C. I. & Rowland, I. R. Diet, fecal water, and colon cancer–development of a biomarker. Nutr. Rev. 67, 509–526. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1753-4887.2009.00224.x (2009).

Joosen, A. M. et al. Effect of dietary meat and fish on endogenous nitrosation, inflammation and genotoxicity of fecal water. Mutagenesis 25, 243–247. https://doi.org/10.1093/mutage/gep070.27914nc421_10 (2010).

Hebels, D. G. et al. Red meat intake-induced increases in fecal water genotoxicity correlate with pro-carcinogenic gene expression changes in the human colon. Food Chem. Toxicol. 50, 95–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fct.2011.10.038 (2012).

Pierre, F. et al. New marker of colon cancer risk associated with heme intake: 1,4-dihydroxynonane mercapturic acid. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 15, 2274–2279. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0085 (2006).

Martin, O. C. et al. Antibiotic suppression of intestinal microbiota reduces heme-induced lipoperoxidation associated with colon carcinogenesis in rats. Nutr. Cancer. 67, 119–125. https://doi.org/10.1080/01635581.2015.976317 (2015).

Ríos-Covián, D. et al. Intestinal short chain fatty acids and their link with diet and human health. Front. Microbiol. 7, 185. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2016.00185 (2016).

Dvorak, K. et al. Bile acids in combination with low pH induce oxidative stress and oxidative DNA damage: Relevance to the pathogenesis of Barrett’s oesophagus. Gut 56, 763–771. https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.2006.103697 (2007).

Lechner, S. et al. Bile acids mimic oxidative stress induced upregulation of thioredoxin reductase in colon cancer cell lines. Carcinogenesis 23, 1281–1288. https://doi.org/10.1093/carcin/23.8.1281 (2002).

Ocvirk, S. & O’Keefe, S. J. Influence of bile acids on colorectal cancer risk: Potential mechanisms mediated by Diet-Gut microbiota interactions. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 6, 315–322. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13668-017-0219-5 (2017).

Gamage, S. M. K., Lee, K. T. W., Dissabandara, D. L. O., Lam, A. K. & Gopalan, V. Dual role of heme iron in cancer; promotor of carcinogenesis and an inducer of tumour suppression. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 120, 104642. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yexmp.2021.104642 (2021).

Seiwert, N., Heylmann, D., Hasselwander, S. & Fahrer, J. Mechanism of colorectal carcinogenesis triggered by heme iron from red meat. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Cancer. 1873, 188334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbcan.2019.188334 (2020).

Bastide, N. M., Pierre, F. H. & Corpet, D. E. Heme iron from meat and risk of colorectal cancer: A meta-analysis and a review of the mechanisms involved. Cancer Prev. Res. (Phila). 4, 177–184. https://doi.org/10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-10-0113 (2011).

Rafter, J. et al. Dietary synbiotics reduce cancer risk factors in polypectomized and colon cancer patients. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 85, 488–496. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/85.2.488 (2007).

De Filippo, C. et al. Gut microbiota drives colon cancer risk associated with diet: A comparative analysis of meat-based and pesco-vegetarian diets. Microbiome. 12, 180. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-024-01900-2 (2024).

Bernstein, A. M. et al. Processed and unprocessed red meat and risk of colorectal cancer: Analysis by tumor location and modification by time. PLoS ONE 10, e0135959. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0135959 (2015).

Carr, P. R., Holleczek, B., Stegmaier, C., Brenner, H. & Hoffmeister, M. Meat intake and risk of colorectal polyps: Results from a large population-based screening study in Germany. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 105, 1453–1461. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.116.148304 (2017).

Bradbury, K. E., Murphy, N. & Key, T. J. Diet and colorectal cancer in UK Biobank: A prospective study. Int. J. Epidemiol. 49, 246–258. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyz064 (2020).

Farsi, D. N. et al. Substituting meat for mycoprotein reduces genotoxicity and increases the abundance of beneficial microbes in the gut: Mycomeat, a randomised crossover control trial. Eur. J. Nutr. 62, 1479–1492. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-023-03088-x (2023).

Corpet, D. E. Red meat and colon cancer: Should we become vegetarians, or can we make meat safer?. Meat Sci. 89, 310–316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meatsci.2011.04.009 (2011).

Cuparencu, C. et al. Biomarkers of meat and seafood intake: An extensive literature review. Genes Nutr. 14, 35. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12263-019-0656-4 (2019).

Yang, L., Zhang, Y., Zhang, Y. & Fan, Z. Mechanism and application of ferroptosis in colorectal cancer. Biomed. Pharmacother. 158, 114102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2022.114102 (2023).

Gao, J. et al. The association of fried meat consumption with the gut microbiota and fecal metabolites and its impact on glucose homoeostasis, intestinal endotoxin levels, and systemic inflammation: A randomized controlled-feeding trial. Diabetes Care 44, 1970–1979. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc21-0099 (2021).

Bratlie, M. et al. Effects of high intake of cod or salmon on gut microbiota profile, fecal output and serum concentrations of lipids and bile acids in overweight adults: a randomised clinical trial. Eur. J. Nutr. 60, 2231–2248. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-020-02417-8 (2021).

O’Connor, L. E., Kim, J. E., Clark, C. M., Zhu, W. & Campbell, W. W. Effects of total red meat intake on glycemic control and inflammatory biomarkers: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Adv. Nutr. 12, 115–127. https://doi.org/10.1093/advances/nmaa096 (2021).

Guasch-Ferré, M. et al. Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of red meat consumption in comparison with various comparison diets on cardiovascular risk factors. Circulation 139, 1828–1845. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.035225 (2019).

Sun, L. et al. Red meat consumption and risk for dyslipidaemia and inflammation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 9, 996467. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2022.996467 (2022).

Hagen, I. V. et al. High intake of fatty fish, but not of lean fish, affects serum concentrations of TAG and HDL-cholesterol in healthy, normal-weight adults: A randomised trial. Br. J. Nutr. 116, 648–657. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114516002555 (2016).

Costabile, A. et al. Impact of polydextrose on the fecal microbiota: A double-blind, crossover, placebo-controlled feeding study in healthy human subjects. Br. J. Nutr. 108, 471–481. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114511005782 (2012).

Eid, N. et al. Impact of palm date consumption on microbiota growth and large intestinal health: A randomised, controlled, cross-over, human intervention study. Br. J. Nutr. 114, 1226–1236. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114515002780 (2015).

Klinder, A., Forster, A., Caderni, G., Femia, A. P. & Pool-Zobel, B. L. Fecal water genotoxicity is predictive of tumor-preventive activities by inulin-like oligofructoses, Probiotics (Lactobacillus rhamnosus and Bifidobacterium lactis), and their synbiotic combination. Nutr. Cancer. 49, 144–155. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327914nc4902_5 (2004).

Alhmoud, J. F., Woolley, J. F., Al Moustafa, A.-E. & Malki, M. I. DNA damage/repair management in cancers. Cancers 12, 1050. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12041050 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the entire staff of the Nutrition Unit at Careggi University Hospital for their invaluable contributions. We also extend our thanks to the participants for their cooperation and commitment throughout the study.

Funding

This study is cofunded by the JPI HDHL-INTIMIC Call for Joint Transnational Research Proposals on “Interrelation of the Intestinal Microbiome, Diet and Health” (Reference Number: JTC-2017-7) and by the Ministry of Education, University and Research of Italy. For the list of the project funded please see https://www.healthydietforhealthylife.eu/index.php/joint-actions/hdhl-intimic (accessed August 8, 2019). The funders had no input into the design and conduct of the project; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Monica Dinu contributed to the study design, coordinated recruitment, developed dietary plans, participated in clinical evaluations, performed statistical analyses, and drafted the manuscript. Sara Ristori conducted FW geno-cytotoxicity experiments and performed statistical analyses. Sofia Lotti participated in clinical evaluations, conducted laboratory analyses, and critically revised the manuscript. Niccolò Meriggi contributed to the critical intellectual revision of the manuscript. Alice Nerini conducted FW geno-cytotoxicity experiments and performed statistical analyses. Giuditta Pagliai contributed to the study design, assisted with recruitment and clinical evaluations, and critically revised the manuscript. Sylvie Chevolleau provided critical intellectual revisions to the manuscript. Jildau Bowman was responsible for SCFA and bile acid analysis and contributed to the critical intellectual revision of the manuscript. Giovanna Caderni contributed to the study design, conducted statistical analyses, and provided critical intellectual revisions to the manuscript. Barbara Colombini participated in clinical evaluations and provided critical intellectual revisions to the manuscript. Philippe Gerard provided critical intellectual revisions to the manuscript. Lisa Giovannelli contributed to the study design, was responsible for the FW geno-cytotoxicity experiments, conducted statistical analyses, drafted the manuscript and critically revised it. Francoise Gueraud was responsible for peroxidation analyses and provided critical intellectual revisions to the manuscript. Rossella Marcucci was responsible for biochemical analyses and provided critical intellectual revisions to the manuscript. Fabrice Pierre contributed to the critical intellectual revision of the manuscript. Carlotta De Filippo contributed to the study design, performed statistical analyses, and critically revised the manuscript. Francesco Sofi contributed to the study design, coordinated recruitment, conducted clinical evaluations, performed statistical analyses, drafted the manuscript, and critically revised it.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dinu, M., Ristori, S., Pagliai, G. et al. Effects of meat-based, meat-based with α-tocopherol, and pesco-vegetarian diets on biomarkers associated with colorectal cancer risk: a randomized behavioral intervention trial. Sci Rep 16, 1502 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31410-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31410-6