Abstract

This paper investigates wave propagation in microstretch thermoelastic solids incorporating the two-temperature theory, which models heat conduction using two distinct temperature fields to better capture microtemperature effects. We identify and analyze seven distinct wave types: longitudinal displacement (LD), thermal (T), microstretch (LM), longitudinal microtemperature (LT), coupled transverse displacement (CD-I), transverse microrotational (CD-II), and transverse microtemperature (CD-III) waves. For each wave type, we derive explicit expressions for phase velocity, attenuation coefficient, penetration depth, and specific loss, highlighting how these parameters vary with the two-temperature effects. Our results demonstrate that incorporating microstretch and microtemperature fields leads to significant changes in wave characteristics, including the emergence of new wave modes and modified attenuation behavior compared to classical models. Graphical presentations illustrate these effects quantitatively, with phase velocity and attenuation variations changes under varying two-temperature parameter regimes. Additionally, special limiting cases of practical interest are discussed. The findings offer new insights for advanced material design and non-destructive evaluation in microstructured thermoelastic solids.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Eringen1 introduced the theory of microstretch elastic solids, where material points can undergo independent stretching and contraction in addition to translations and rotations. In this theory, each material point is endowed with three deformable directors, constrained to exhibit only breathing-type microdeformations. The theory of thermo-microstretch elastic solids was further developed by Eringen2. Examples of microstretch solids include composite materials reinforced with chopped elastic fibers, porous media saturated with gas or inviscid liquids, asphalt, and solid–liquid crystals.

The concept of microtemperatures in elastic solids originated from the works of Eringen 3, Grot4, Wozniak5,6, Ieşan7,8, and Ieşan and Quintanilla9,10. Classical continuum theories often fail to adequately describe size-dependent phenomena and nanoscale effects observed experimentally. The microtemperature theory addresses these limitations by introducing additional thermal variables that depend on the microcoordinates of microelements within the material. This approach allows for the study of size effects and complex thermomechanical coupling relevant to applications in nanotechnology, engineering, and geophysics. The thermodynamics of microstructured materials with microtemperatures was formulated by Grot4, who extended classical balance laws and the Clausius–Duhem inequality to include microtemperature effects.

Riha11 studied heat conduction in materials with microtemperatures, demonstrating close agreement between theoretical predictions and experimental data on materials like silicone rubber with aluminum particles and human blood. Subsequent works by Iesan and Quintanilla10, Magaña and Quintanilla12, Noelia et al.13, Liu and Quintanilla14, and Ahmima and Fareh15 have further developed thermoelastic models incorporating microtemperature fields. Recent studies by Kaushal and Singh16 and Kaushal et al.17 have advanced thermoelastic wave theories by examining refracted waves in microstretch media with two-temperature coupling and analyzing wave propagation effects in micropolar elastic media with voids and non-free surfaces.

Thermoelasticity with two temperatures is a notable non-classical theory of thermodynamics in elastic solids, distinguishing between two distinct temperature fields: the conductive temperature (\(\Phi\)) arising from thermal processes, and the thermodynamic temperature (T) related to mechanical processes18. Chen et al.19 formulated a thermoelastic theory involving these two temperatures, incorporating a material parameter a that characterizes their coupling. This two-temperature model has been widely used to predict electron and phonon temperature distributions in ultrashort laser processing of metals and other advanced applications. More recently, Abouelregal20 and other researchers have extended this model to include higher-order time derivatives and phase-lag effects.

Several researchers have investigated wave propagation in thermoelastic media incorporating two-temperature and microstretch effects. Youssef21 developed wave propagation theory in generalized porothermoelasticity with two-temperature effects, while Hou et al.22 studied reflection and transmission of inhomogeneous plane waves in thermoporoelastic media using two-temperature heat conduction equations. Our study distinguishes itself by integrating the microstretch continuum theory with microtemperature fields and the two-temperature model, enabling the analysis of new wave modes and complex thermomechanical couplings that previous models did not consider.

Wave phenomena have been widely studied by researchers such as Vlase et al.23,24, Marin et al.25,26, Sharma and Khator27,28, Kaushal et al.29,30, Yadav et al.31, Kumar et al.32,33,34, Ahmed and Ali35, Debnath and Singh36, and Lotfy et al.37 who have explored wave propagation under various generalized thermoelastic, micropolar, and non-local theories. Achenbach38 investigated wave reflection and refraction behavior under three different thermoelastic theories, focusing on bidirectional coupling between longitudinal elastic waves and thermal fields in advanced materials. They examined the thermomechanical model effects on wave amplitudes and transmission characteristics39,40.

The applications of microtemperature and microstretch theories span across microelectronics, biomechanics, aerospace, geomechanics, and wave propagation in materials where classical thermoelastic models fail. These theories enable realistic modeling of finite thermal wave speeds, microscale heat transfer, and thermomechanical coupling, with practical implications in smart actuators, energy harvesting devices, geothermal systems, seismic response prediction, aerospace structures, and biomedical tissues41,42.

In this paper, we investigate the propagation of plane waves in microstretch thermoelastic solids incorporating microtemperatures and two-temperature effects. We analyze the influence of these effects on the phase velocity, attenuation coefficient, specific loss, and penetration depth of longitudinal displacement (LD), thermal (T), microstretch (LM), longitudinal microtemperature (LT), and coupled transverse waves (CD-I, CD-II, CD-III). The results are presented graphically over frequency ranges, highlighting novel wave modes and coupling effects arising from the integrated microstretch and two-temperature framework. Particular cases of interest are also discussed.

Basic equations

Following Eringen3 and Iesan7, the field equations for a homogeneous, isotropic microstretch thermoelastic solid with microtemperatures and two temperatures without body forces, body couples, stretch force, heat sources, and first heat source moment are given as:

where

where \(K\), \(\alpha\), \(\beta\),\(\gamma\),\(\lambda\),\(\mu ,\,\alpha_{0} ,\,\lambda_{0} ,\,\lambda_{1} ,\,\mu_{1} ,\,\mu_{2} ,\,j_{0} ,\,k_{i} (i = 1,...........,6)\) are constitutive coefficients. \({\varvec{u}}\) is the displacement vector, \(\;{\mathbf{\varphi }}\) is the microrotation vector, \({\varvec{w}}\) is the microtemperature vector and \(\varphi^{*}\) is the microstretch scalar, \(\rho\) is the density,\(\;j\) is the microinertia, \(\;c^{*} \;\) is the specific heat at constant strain, \(K^{*}\) is the thermal conductivity, \(T\) is the thermodynamic temperature, \(\Phi\) is the conductive temperature, \(T_{0}\) is the reference temperature, \(a\) is a two temperature parameter,\(\;\nu = \left( {3\lambda + 2\mu + K} \right)\alpha_{{T_{1} \;}} ,\,\,\nu_{1} = \left( {3\lambda + 2\mu + K} \right)\alpha_{{T_{2} \;}} ,\) where \(\alpha_{{T_{1} }} ,\,\,\,\alpha_{{T_{2} }}\) are the coefficients of linear thermal expansion. The main coefficients, constants, and parameters used in this study are summarized in Appendix I (Table A1 (Nomenclature)), along with their physical meanings and roles in wave propagation.

Formulation of the problem

A homogeneous, isotropic microstretch thermoelastic solid with microtemperatures and two temperatures is considered.

The displacement vector, microtemperature vector, and microrotation vector for the two-dimensional case are taken as

For convenience, the following dimensionless quantities have been considered

The displacement components and microtemperature components are related to the potential functions in dimensionless form as43,44

Making use of dimensionless quantities defined by Eq. (8) in Eqs. (1)–(5) and with the aid of Eqs. (6), (7) and (9), the following equations are obtained

where the values of \(a_{i}\) are defined in Appendix II.

In all the above relations and equations, the primes have been suppressed.

Solution of the problem

The solution of Eqs. (10)–(16) is assumed of the form

where \(\mathop \varphi \limits^{\_} ,\mathop {\varphi^{*} }\limits^{\_} ,\mathop \Phi \limits^{\_} ,\mathop \psi \limits^{\_} ,\mathop {\varphi_{2} }\limits^{\_} ,\mathop {\psi_{1} }\limits^{\_} ,\mathop {\varphi_{1} }\limits^{\_}\) are undetermined amplitudes that are independent of time \(t\) and coordinates \({x}_{m}(m=1,\text{\hspace{0.17em}}3),\)\(\omega\) is the frequency and \(\xi\) is the wave number. \(l_{i} ,\,\,\,i = 1,\,3\) are the direction cosines of the wave normal to the \(x_{1} x_{3} -\) plane satisfying the relation \(l_{1}^{2} + l_{3}^{2} = 1\).

Making use of Eq. (17) in Eqs. (10), (13), (14) and (15), we obtain,

The above equations will have a non-trivial solution if and only if the following determinant vanishes

By solving Eq. (22), we obtain the following polynomial equation in \(\xi\)

where the values of \(F_{i}\) are given in Appendix III.

Solving Eq. (23), the eight roots of \(\xi\) are obtained, in which four roots \(\xi_{1} ,\,\xi_{2} ,\,\xi_{3}\) and \(\xi_{4}\) correspond to positive \(x_{3} -\) direction and other four roots \(- \xi_{1} ,\, - \xi_{2} ,\, - \xi_{3}\) and \(- \xi_{4}\) correspond to negative \(x_{3} -\) direction. The roots \(\xi_{1} ,\,\xi_{2} ,\,\xi_{3}\) and \(\xi_{4}\) corresponds to four waves in descending order of their velocities i.e. LD-wave, T-wave, LM-wave and LT-wave.

Making use of Eq. (17) in Eqs. (11), (12) and (16), the following equations are obtained

The above equations will have a non-trivial solution if and only if the following determinant vanishes.

The Eq. (26) gives the following polynomial equation in \(\xi\)

where

Solving Eq. (28), we obtain six roots of \(\xi\), in which three roots \(\xi_{1} ,\,\,\xi_{2}\) and \(\xi_{3}\) correspond to positive \(x_{3} -\) direction and other four roots \(- \xi_{1} ,\, - \xi_{2}\) and \(- \xi_{3}\) correspond to negative \(x_{3} -\) direction. Corresponding to roots \(\xi_{1} ,\,\,\xi_{2}\) and \(\xi_{3}\) there exist three waves in descending order of their velocities, namely CD-I wave, CD-II wave and CD-III wave.

The numerical computations required for solving the characteristic equations and evaluating wave parameters such as phase velocity, attenuation coefficient, specific loss, and penetration depth were carried out using MATLAB. Root-finding routines were employed to determine complex wave numbers for different modes45.

Phase velocity

The phase velocity of a wave describes the speed at which a particular phase of the wave (e.g., a crest) propagates through the medium. It is a fundamental parameter characterizing wave propagation in thermoelastic solids and directly influences energy transport and signal timing.

Mathematically, the phase velocities of the different wave modes are defined as

where.

\(V_{1} ,\,V_{2} ,\,V_{3} ,\,V_{4} ,\,V_{5} ,\,V_{6} ,\,V_{7}\) are the phase velocities of LD, T, LM, LT, CD-I, CD-II and CD-III waves respectively.

The detailed understanding of phase velocity is crucial as it governs wave dispersion and energy propagation in complex media. Classic references such as38 and39 provide foundational insights into elastic wave mechanics and thermoelastic wave propagation, which serve as theoretical underpinnings for this study.

Attenuation coefficient:

Attenuation coefficients quantify the exponential decay of wave amplitude due to material damping and scattering mechanisms. For each wave type, the attenuation coefficient is given by the imaginary part of the complex wave number:

where.

\(Q_{1} ,\,Q_{2} ,\,Q_{3} ,\,Q_{4} ,\,Q_{5} ,\,Q_{6} ,\,Q_{7}\) are the attenuation coefficients of LD, T, LM, LT, CD-I, CD-II and CD-III waves respectively.

Accurate estimation of attenuation is essential for understanding energy loss and signal weakening in materials.

Specific loss

The ratio of energy (\(\overline{W}\)) dissipated in taking a specimen through a stress cycle, to the elastic energy (W) stored in the specimen when the strain is maximum, is defined as specific loss. It is the most direct method of defining internal friction for a material. For a sinusoidal plane wave of small amplitude, Kolsky44, shows that the specific loss \((\overline{W} /W)\) equals 4π times the absolute value of the ratios of imaginary part of \(\xi\) to the real part of \(\xi\), i.e.

This parameter is widely used in material characterization, nondestructive testing, and seismic wave analysis.

Penetration depth

The penetration depth indicates how far a wave can travel before its amplitude decays to 1/e of its original magnitude due to attenuation. It is defined as

This parameter is significant in applications involving thermal and mechanical wave propagation where energy localization and dissipation play critical roles.

Particular cases

-

(i)

If the two-temperature effect is neglected in Eq. (22), we obtain the phase velocity, attenuation coefficient, penetration depth, and specific loss for a microstretch thermoelastic solid with microtemperatures, and the results will be the same as obtained by Kumar et al.43

-

(ii)

If the microtemperature effect is neglected in Eq. (22), we obtain phase velocity, attenuation coefficient, penetration depth, and specific loss for a microstretch thermoelastic solid with two temperatures, and the results will be the same as obtained by Kumar et al.45.

-

(iii)

When the effect of microstretch is removed in Eq. (22), the phase velocity, attenuation coefficient, penetration depth, and specific loss for a thermoelastic solid with two temperatures and microtemperatures are obtained.

Numerical results and discussion

For numerical computations, the material constants were taken from previously established sources: micropolar constants from Eringen2, thermal parameters from46, microstretch parameters from47, and microtemperature parameters from48,49. All calculations were carried out using MATLAB routines. The values of micropolar constants are taken from Eringen2:

and thermal parameters are taken from46:

Microstretch parameters are taken as47

and microtemperatures parameters are taken as48,49

The graphical representation of results, including 3-D plots, was prepared using OriginPro for clear visualization of the variation of these parameters with frequency and material constants.

To illustrate the influence of the two-temperature parameter, the results are presented for both cases in Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20: (i) microstretch thermoelastic solids with microtemperatures and two temperatures (MST) and (ii) microstretch thermoelastic solids with microtemperatures but without the two-temperature effect (WST).

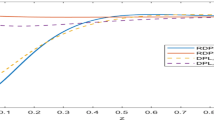

Phase velocity (Figures 1, 2, 3, 4, 5)

The variations of phase velocity with frequency are illustrated in Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5. Collectively, these results reveal that the inclusion of two-temperature effects consistently enhances the propagation speed of different wave modes. In the MST case, the phase velocity curves often exhibit oscillatory behavior, while the corresponding WST curves display more monotonic trends. This difference highlights the role of two-temperature coupling in introducing additional dispersion into the system. For example, the LD, LM, and LT wave velocities increase more rapidly with frequency under MST compared to WST, reflecting the stronger thermo-mechanical interaction. Moreover, the relative ordering of wave speeds is preserved, but the magnitude of separation between modes becomes more pronounced in the presence of two temperatures. Overall, the figures collectively demonstrate that the two-temperature effect accelerates the transmission of energy through the medium and modifies the dispersion characteristics. The increase in phase velocity under MST conditions is not just a numerical observation but a direct consequence of the enhanced thermo-mechanical coupling introduced by the two-temperature theory. In this framework, conductive and thermodynamic temperatures interact differently with the lattice vibrations, effectively stiffening the medium and reducing thermal relaxation delays. As a result, elastic waves propagate faster because the material responds more coherently to applied oscillations. Oscillatory patterns in phase velocity further indicate resonance-like interactions between mechanical waves and internal microtemperature fields, which are absent in the WST case.

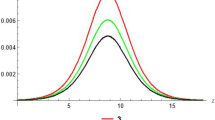

Attenuation coefficient (Figures 6, 7, 8, 9, 10)

The attenuation coefficients for the different wave modes are shown in Figs. 6, 7, 8, 9, 10. Taken together, these results demonstrate that the MST case generally exhibits higher attenuation compared to WST, confirming that two-temperature effects amplify dissipative processes. While some modes (e.g., LD and T waves) show a monotonic increase in attenuation with frequency, others display oscillatory or non-monotonic trends. This behavior indicates the presence of competing mechanisms: energy dissipation through microtemperature fields and dispersion effects due to microstretch coupling. The MST case shows stronger fluctuations, particularly at intermediate frequencies, which may be attributed to resonant interactions between thermal and microstructural modes. These results underscore the fact that two-temperature coupling does not simply increase attenuation uniformly but also modifies the qualitative frequency dependence of energy dissipation. The higher attenuation observed in MST arises from additional pathways for energy dissipation. Two-temperature theory introduces a nonequilibrium between thermodynamic and conductive temperatures, causing repeated energy exchange between lattice vibrations and thermal carriers. This mismatch acts as a damping mechanism, increasing wave energy absorption. Oscillatory attenuation curves reflect frequency ranges where this energy exchange is especially strong, suggesting possible resonances between the thermal relaxation time and wave frequency. Thus, the MST case reveals more complex damping phenomena than WST, where only a single thermal field governs attenuation.

Specific loss (Figures 11, 12, 13, 14, 15)

The behavior of specific loss with frequency is summarized in Figs. 11, 12, 13, 14, 15. Unlike phase velocity and attenuation, which generally increase with frequency, specific loss exhibits both decreasing and oscillatory patterns depending on the wave mode. The MST case typically produces higher values of specific loss than WST, especially in the low-to-intermediate frequency range. This reflects the fact that two-temperature coupling enhances internal friction, leading to greater energy dissipation per cycle. At higher frequencies, both MST and WST cases show decreasing specific loss for most modes, indicating that dissipation becomes less significant relative to stored elastic energy. Oscillatory patterns, observed in certain modes, suggest mode coupling effects where microtemperature and microstretch interactions modulate the balance between energy storage and dissipation. Together, the figures highlight that the two-temperature theory enriches the complexity of loss behavior beyond the predictions of classical microstretch models. Specific loss represents the fraction of stored elastic energy dissipated per cycle. Its enhancement under MST conditions highlights how two-temperature interactions intensify internal friction within the medium. When conductive and thermodynamic temperatures diverge, the resulting microscopic thermal stress relaxations introduce irreversible energy dissipation. This effect is strongest at lower frequencies, where the system has more time per cycle to exchange energy between the two temperatures. At higher frequencies, the time available per cycle is too short for full energy transfer, leading to reduced specific loss. This explains the overall decreasing trend in both MST and WST, while MST consistently exhibits higher values due to stronger coupling.

Penetration depth (Figures 16, 17, 18, 19, 20)

The penetration depth results, presented in Figs. 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, show an overall decreasing trend with frequency, consistent with the expected inverse relationship between attenuation and penetration. The MST case consistently demonstrates larger penetration depths than WST, especially at higher frequencies, which indicates that two-temperature effects allow waves to travel farther before significant amplitude decay. Oscillatory penetration depth behavior is observed for certain modes under MST, again emphasizing the role of additional thermal coupling in modifying energy transport. In some frequency ranges, MST penetration depth exceeds WST by an order of magnitude, highlighting the profound influence of two-temperature interactions on wave propagation distance. Penetration depth depends inversely on attenuation. The greater penetration depth observed in MST is physically linked to the modified balance between dispersion and damping. While MST enhances attenuation at some frequencies, it simultaneously increases phase velocity, allowing waves to carry energy deeper before amplitude decay dominates. In addition, the two-temperature coupling improves the efficiency of thermal energy redistribution within the lattice, delaying complete wave damping. Oscillatory penetration depth in MST reflects alternating regimes of enhanced and suppressed thermal energy transfer, producing localized windows where waves can travel significantly farther than in the WST case.

General observations

By considering the results as a whole, rather than as isolated figures, a coherent picture emerges: two-temperature effects systematically increase phase velocity, enhance attenuation coefficients, amplify specific loss in the low-frequency regime, and extend penetration depths at higher frequencies. These trends collectively confirm that the introduction of two-temperature coupling enriches the dynamical response of microstretch thermoelastic solids with microtemperatures. The findings suggest that tailoring the two-temperature parameter could provide a powerful tool for engineering materials with desired wave propagation characteristics, such as increased dispersion for signal control, enhanced damping for vibration isolation, or extended penetration depth for energy transmission applications.

Conclusion

-

A microstretch thermoelastic solid model with microtemperatures and two-temperature theory is developed.

-

Propagation of plane waves—LD, T, LM, LT, CD-I, CD-II, and CD-III—is analyzed within this framework.

-

The two-temperature effect significantly influences wave characteristics: phase velocity, attenuation coefficient, specific loss, and penetration depth across frequencies.

-

Numerical results reveal that the two-temperature model yields higher phase velocities and attenuation coefficients than the classical single-temperature model.

-

This reflects enhanced wave dispersion and increased energy dissipation due to stronger thermo-mechanical coupling.

-

Phase velocities of LD, LM, and LT waves increase noticeably with the inclusion of two-temperature effects.

-

Attenuation coefficients for LD and T waves and penetration depths for LD, T, and LM waves also increase compared to models without two-temperature effects.

-

Certain complex interactions and extended phenomena related to the two-temperature microstretch thermoelastic model have not been addressed in this study and remain beyond its current scope. These aspects will be explored in detail in future research.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Eringen, A. C. Microcontinuum Field Theories: I (Springer, 1999).

Eringen, A. C. Theory of micropolar elasticity. J. Math. Mech. 16(1), 1–18 (1971).

Eringen, A. C. Theory of thermo-microstretch elastic solids. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 28(12), 1291–1301 (1990).

Grot, R. A. Thermodynamics of elastic materials with microstructure and microtemperatures. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 7(8), 801–814 (1969).

Wozniak, C. Thermodynamic processes in continua with microstructure. Bull. Pol. Acad. Sci. Tech. Sci. 15(10), 701–708 (1967).

Wozniak, C. Heat conduction in microstructured materials. Arch. Mech. 19(4), 551–565 (1967).

Ieşan, D. Thermoelasticity with microtemperatures: Basic theory and applications. Int. J. Solids Struct. 38(43–44), 7721–7744 (2001).

Ieşan, D. On a theory of thermoelasticity with microtemperatures. J. Thermal Stresses 30(9), 857–873 (2007).

Ieşan, D. & Quintanilla, R. Thermoelasticity with microtemperatures. J. Thermal Stresses 23(1), 1–17 (2000).

Ieşan, D. & Quintanilla, R. On thermoelastic bodies with microtemperatures. Int. J. Solids Struct. 46(16), 2993–3005 (2009).

Riha, A. Heat conduction in materials with microtemperatures. J. Heat Transf. 98(2), 258–263 (1976).

Magaña, A. & Quintanilla, R. Exponential stability in type III thermoelasticity with microtemperatures. J. Thermal Stresses 41(1), 1–16 (2018).

Noelia, et al. “Lord–Shulman thermoelasticity with microtemperatures. J. Therm. Stresses 44(8), 927–946 (2021).

Liu, Y. & Quintanilla, R. Dual-phase-lag one-dimensional thermo-porous-elasticity with microtemperatures. Appl. Math. Modelling 96, 502–516 (2021).

Ahmima, H. & Fareh, A. Decay of a porous thermoelastic system with microtemperature. Math. Methods Appl. Sci. 46(4), 3132–3150 (2023).

Kaushal, A. & Singh, B. Thermoelastic theories on the refracted waves in microstretch thermoelastic media with two-temperature coupling. J. Therm. Stresses 48(2), 123–140 (2025).

Kaushal, S., Kumar, D. & Sharma, P. Wave propagation under the influence of voids and non-free surfaces in a micropolar elastic medium. Acta Mech. 233(8), 3331–3348 (2022).

Chen, P. J., Gurtin, M. E. & Williams, W. O. A theory of heat conduction involving two temperatures. Z. Angew. Math. Phys. 19(4), 614–627 (1968).

Chen, P. J., Gurtin, M. E. & Williams, W. O. On the theory of heat conduction involving two temperatures. Z. Angew. Math. Phys. 20(1), 107–112 (1969).

Abouelregal, A. Two-temperature thermoelastic model without energy dissipation including higher order time-derivatives and two phase-lags. Appl. Math. Mech. 40(3), 345–360 (2019).

Youssef, H. M. Theory of generalized porothermoelasticity. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 44(2), 222–227 (2007).

Hou, W., Fu, L. Y. & Carcione, J. M. Reflection, transmission, and AVO response of inhomogeneous plane waves in thermoporoelastic media with two-temperature equations of heat conduction. Geophysics 89(5), MR297–MR307 (2024).

Vlase, S. et al. A method for the study of vibration of mechanical bar systems with symmetries. Appl. Math. Modelling 48, 689–705 (2017).

Vlase, S. et al. Wave vibrations in a mechanical system with two identical beams. Mech. Res. Commun. 80, 34–40 (2017).

Marin, M. et al. Some results in Moore-Gibson-Thompson thermoelasticity of dipolar bodies. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 482(2), 123567 (2020).

Marin, M. et al. Mixed problem in thermoelasticity of type III for Cosserat media. Mathematics 10(5), 765 (2022).

Sharma, P. & Khator, R. Renewable energy-based wave models in microstructured media. Renew. Energy 165, 1204–1215 (2021).

Sharma, P. & Khator, R. Renewable energy waves and thermoelastic systems. Energy Rep. 8, 456–469 (2022).

Kaushal, S., Sharma, P. & Kumar, D. Impact of non-local, two temperature and impedance parameters on propagation of waves in generalized thermoelastic medium under modified Green-Lindsay model. Math. Mech. Solids 29(6), 933–960 (2024).

Kaushal, S., Sharma, P. & Kumar, D. Wave propagation at free surface in thermoelastic medium under modified Green-Lindsay model with non-local and two temperature. Appl. Math. Modelling 123, 1–22 (2024).

Yadav, V. et al. Effect of memory response and impedance barrier on reflection of plane waves in a nonlocal micropolar porous thermo-diffusive medium. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 182, 104726 (2023).

Kumar, A. & Kumar, D. Wave propagation in a two-temperature microstretch thermoelastic solid. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 142, 103–119 (2019).

Kumar, A., Kumar, D. & Sharma, P. Wave propagation in microstretch thermoelastic solid with microtemperatures. Appl. Math. Mech. 40(6), 735–752 (2019).

Kumar, A., Sharma, P. & Kaushal, S. Thermal shock and wave effects in a nonlocal microstructured solid. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 119, 45–61 (2017).

Ahmed, M. & Ali, M. Propagation and reflection of thermoelastic waves through diffusive porous non-local semiconductor with higher-order fractional derivative. J. Thermal Stresses 47(5), 678–698 (2024).

Debnath, S. & Singh, S. S. Propagation of lamb wave in the plate of microstretch thermoelastic diffusion materials. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng 46, 218 (2024).

Lotfy, Kh. et al. Piezo-photothermal wave dynamics in an orthotropic hygrothermal semiconductor exposed to heat and moisture flux. J. Appl. Phys. 137(10), 105102 (2025).

Achenbach, J. D. Wave Propagation in Elastic Solids (North-Holland, 1973).

Dhaliwal, B. S. & Singh, H. Dynamics of Elastic Bodies (Springer, 1980).

Othman, M. et al. Studies on wave propagation in microstretch thermoelastic solids. Mech. Adv. Mater. Struct. 30(7), 1301–1315 (2023).

Gurtin, M. E. & Williams, W. O. On the theory of heat conduction involving two temperatures. J. Rational Mech. Anal. 14(5), 687–708 (1966).

Gurtin, M. E. & Williams, W. O. On the theory of heat conduction involving two temperatures II. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 18(1), 109–127 (1967).

Kumar, R. et al. Analysis of wave motion in micropolar thermoelastic medium based on Moore–Gibson–Thompson heat equation under non-local and hyperbolic two temperature. Int. J. Non-Linear Mech. 152, 104150 (2024).

Kolsky, H. Stress Waves in Solids (Clarendon Press, 1963).

Kumar, R. et al. Thermoelastic medium with swelling porous structure and impedance boundary under dual-phase lag. J. Thermal Stresses 48(2), 215–240 (2025).

Landau, L. D. & Lifshitz, E. M. Theory of Elasticity 3rd edn. (Pergamon Press, 1984).

Li, X. et al. Reflection and transmission of thermoelastic waves under an external magnetic field based on GN-II heat conduction and dipolar gradient elasticity. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 190, 104751 (2025).

Lotfy, Kh. Two temperature generalized magneto-thermoelastic interactions in an elastic medium under three theories. Appl. Math. Comput. 227, 871–888 (2014).

Othman, M., Lotfy, Kh. & Farouk, R. Transient Disturbance in a Half Space under Generalized Magneto Thermoelasticity with Internal Heat Source. Acta Phys. Pol. A 116(2), 185 (2009).

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University for funding this research under Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R899) Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors have equally participated in the preparation of the manuscript during the implementation of ideas, findings results, and writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Use of AI tools declaration

The authors declare they have not used Artificial Intelligence (AI) tools in the creation of this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kaur, M., Kumar, R., Sharma, S. et al. Two temperatures effect on wave propagation in microstretch thermoelastic medium with microtemperatures. Sci Rep 15, 43816 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31454-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31454-8