Abstract

The efficacy of three-dimensional (3D) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)-based registration techniques in femur models of osteoarthritis (OA) with respect to OA severity was investigated in this study. MRI data of 58 OA femurs (23 Kellgren–Lawrence grade 2, 20 grade 3, and 15 grade 4) and 31 normal femurs were analyzed. Distal femurs were segmented and converted into 3D reconstructed models. Several registration techniques (fiducial registration and automated landmarking using point-cloud alignment and correspondence analysis [ALPACA]), were applied to OA femur models. Fit quality and volume differences between the reference and OA models were assessed with respect to OA severity. Generalized Procrustes analysis (GPA) and principal component analysis (PCA) explored important bone-shape features of OA femurs. Deformable ALPACA registration exhibited the best fit. Significant differences were observed in the quality of fit of our techniques and volume differences between the reference and OA models in the OA severity groups. The mean OA model demonstrated bony enlargement at the edges of the cartilage plate in 3D statistical shape analysis (SSA). This shape variation was a major component associated with OA severity in the GPA-aligned PCA. This novel 3D MRI-based registration technique and SSA is useful to differentiate OA severity grades.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a debilitating disease affecting the knees of older adults. The prevalence of OA increases with age and often results from progressive wear and tear 1. Approximately 10% of individuals aged > 60 years have symptomatic OA, with the prevalence increasing to 40% in those > 70 years-of-age1,2. Although the pathogenesis of OA is not fully understood, emphasis has been placed on articular cartilage degeneration, bone remodeling, osteophyte formation, periarticular structural weakness, and synovitis3,4.

Radiological evaluation of OA is typically based on plain radiography or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The Kellgren–Lawrence (K–L) plain radiograph-based grading system has been the standard scoring system for several decades. The K–L system is based on the severity of radiographic features, such as joint space narrowing, subchondral sclerosis, cysts, and osteophytosis5. MRI is suitable for more detailed evaluations and surveying bone and surrounding tissue abnormalities6,7. Furthermore, the advent of MRI has increased the use of high-resolution imaging techniques7. At our institution, three-dimensional T2*-weighted fast field echo (3D T2* FFE) is routinely used in knee MRI studies. Although 3D T2* FFE is primarily aimed at the high-resolution evaluation of cartilage, it also clearly visualizes other tissues, including bone, providing volumetric data for 3D segmentation and shape model analysis.

Advances in high-resolution 3D imaging techniques have facilitated assessments of morphological changes in complex biological structures using methods that include statistical shape analysis (SSA)8,9,10. In 3D SSA, high-resolution images are acquired, after which the anatomical landmark information is obtained. These anatomical landmarks were subsequently used in the multivariate shape analyses. Manual registration by experts and automated approaches is commonly used to collect landmark datasets. Manual annotation of landmarks is laborious, time-consuming, and subject to inter-observer bias11. Automated approaches do not have such drawbacks but mostly rely on high-end hardware, specialized automated analysis platforms and software tools, and user knowledge11,12. Recently, the analysis of 3D morphological data has become easier due to the availability of 3D slicer image processing software13. This cutting-edge open-source software contains a set of modules including 3D automatic registration and SSA. For example, a fiducial registration module performs semiautomatic landmark point matching using rigid and deformable registration14. Furthermore, automated marking through point-cloud alignment and correspondence analysis (ALPACA) enables rapid and accurate automated landmarking using point-cloud-based deformable model registration15. In addition, a module for generalized Procrustes analysis (GPA) and principal component analysis (PCA) is a major tool for 3D SSA included in SlicerMorph on a 3D Slicer platform16.

The use of 3D SSA for knee OA has been studied previously. A landmark-based SSA study reported observable shape changes, including a slight expansion of the posterior and distal condylar surfaces, in patients with knee OA before symptom onset17. Other studies exploring the specific shape features of symptomatic knee OA revealed that widening and flattening of the femoral condyle, expansion around the cartilage plate, and narrowing of the intercondylar notch are important factors18,19. A recent study by Lynch et al.20 examined subchondral bone expansion, particularly in the knee condyles. Studies on the SSA in knee OA have mainly investigated the differentiation of OA and asymptomatic bone shape. In a unique attempt, one study evaluated radiography-based similarity metrics and correlated them with the severity of knee OA21. However, to the best of our knowledge, 3D SSA-based quantitative methods have not been fully studied with respect to OA severity grade.

The performance of 3D SSA depends on the accuracy of the initial model registration process. If this process is insufficient, the obtained geometric features may not accurately reflect the actual results. The degree of fit of these registration methods can be used as an indicator of the similarity between the two structures. Galván-Tejada et al.21 evaluated the bilateral knee asymmetry based on X-ray images using an SSA-based algorithm. These findings suggest a correlation between similarity metrics and OA severity grades. Furthermore, Morton et al.22 reported that the dissimilarity-excluding Procrustes registration technique can quantify osteophyte formation through Boolean subtraction of the reference bone model from the OA bone model. Osteophyte formation is an important radiographic feature of OA, with increased formation reflecting severity of disease progression. Therefore, SSA-based similarity and dissimilarity measurements can assist in radiological grading of OA severity.

This study aimed to evaluate the feasibility of several registration techniques for femoral OA models. We assessed the quality of fit of our techniques and the volume differences between the reference and OA models with respect to OA severity. GPA and PCA were performed to explore important bone-shape features of knees with OA.

Results

Application of 3D registration techniques

The results of the fiducial and ALPACA registration methods are listed in Table 1. The best fit quality was observed for the deformable type of ALPACA registration, with an average absolute distance of 0.30 ± 0.08 mm and Dice co-similarity coefficient of 0.980 ± 0.006. Statistical differences in the average surface distances and Dice co-similarity scores were observed between the OA severity groups for all registration methods except for the ALPACA rigid type.

Volume differences between OA and reference models

Table 2 summarizes volume differences between the OA and reference models for each registration method. The deformable ALPACA registration exhibited the smallest volume difference among all the registration methods. Statistical differences were observed between the OA severity groups for all registration methods except for the rigid ALPACA type.

Tables 3 and 4 summarize volume differences in the medial and lateral portions, respectively. In the medial portion, statistically significant differences between the OA severity groups were observed for the warping type of fiducial registration and the deformable type of ALPACA registration. In the lateral portion, the distinction between the OA severity groups was not as clear as that observed in the medial portion, and only the warping type of fiducial registration demonstrated a statistically significant difference.

3D SSA based on GPA and PCA

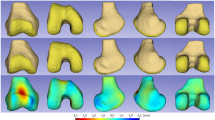

We observed the best fit quality for the deformable type of ALPACA registration, which was applied to the SSA analysis. Figure 1 presents the mean normal and OA surface models as well as the pointwise signed distances between them. The OA model displayed bony expansion (red area) at the edges of the femoral cartilage plate, which was 10 mm greater than that of the normal model. This bony enlargement along the anterior-to-posterior edge was particularly pronounced in the medial condyle. Furthermore, bony expansion (red area) was observed in the proximal part of the posterior medial condyle, which was up to 10 mm larger than that in the mean normal model. In contrast, the mean OA model displayed a slight space reduction (represented by a slightly blue area) in the intercondylar notch compared with the mean normal model.

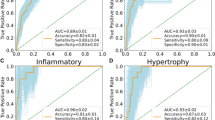

Figure 2 presents the results of the PCA of the distal femur of OA knees using the GPA-aligned coordinate system, along with the cumulative variance and variance per mode. The first three principal components accounted for 56.4% of the observed population variance. The figure also presents the 3D shape variations (corresponding to mean ± 2.5 standard deviation [SD]) in the first three principal components. The first principal component, accounting for 37.2% of the variation, was mainly related to the shape variation in the medial condyle and enlargement at the edges of the cartilage plate. The second principal component, accounting for 11.4% of the variation, was related to shape variation in the intercondylar notch. The + 2.5 SD shape exhibited a narrower and deeper intercondylar notch, whereas the − 2.5 SD shape exhibited the opposite. The third principal component, accounting for 7.8% of the variation, was related to the size and position of the lateral condyle (smaller and medialized in the − 2.5 SD shape) and the enlargement of medial condyle at the edges of the cartilage plate. Figure 2 shows the distribution of the PCA scores along the two main components (first and second principal components). The severe OA group exhibited higher scores for the first principal component (right side of the graph).

Shape variations (corresponding to mean ± 2.5 standard deviation [SD]) in the first three principal components of the knee osteoarthritis femur models: the first (a), the second (b), and the third (c). For each component, the front and bottom sides of the models are presented in order of + 2.5 SD, mean, and − 2.5 SD, from top to bottom. (d) Cumulative variance (line plot) and fraction of variance (bar plot) explained by principal components of the knee osteoarthritis femur models. (e) Distribution of principal component scores along the two main components (the first and second principal components).

Discussion

This study evaluated the applicability of several registration techniques to OA femur models according to OA severity grades. The best fit quality was observed for the deformable ALPACA registration, with significant differences in the fit quality scores between the OA severity groups. Furthermore, the volume differences between the reference and OA models varied depending on OA severity. In the 3D SSA, the mean OA model demonstrated bony enlargement at the edges of the cartilage plate and proximal part of the posterior medial condyle. In addition, the PCA findings demonstrated that the major components were related to shape variations in the medial condyle and enlargement of the cartilage plate edges. Specifically, the severe OA group exhibited higher scores on the first principal component.

The morphological features of knees with OA have long been known. Several radiographic characteristics, including joint space narrowing, osteophytosis, subchondral bone sclerosis, and cyst formation, are considered important20. However, these changes are highly variable and depend on the degree of remodeling, resulting in a unique appearance of each knee with OA. The K–L system is the best-known grading system and has been used for several decades to assess OA severity based on plain radiographs5. Plain radiographs are commonly used to evaluate OA because of their availability and low cost. However, they are insensitive to early OA changes and do not adequately assess soft tissue structures21. Instead, MRI is more suitable for accurate evaluation of both bone and soft tissue joint structures6,7. MRI can detect representative early OA changes in both the bone marrow and cartilage that are not visible on radiographs6,7. Several morphological MRI scoring systems have been proposed for evaluating knee OA6. However, both K–L and MRI-based OA grading systems exhibit inter-reader variability and insufficient reliability because they primarily rely on qualitative or quasi-quantitative morphological parameters. To overcome these shortcomings and understand bony structures more realistically, computer-aided morphological analyses using statistical shape models such as SSA could be valuable8,9,10.

The SSA can be performed using an effective registration framework. Most statistical shape models are constructed using landmark-based transformations. Therefore, the landmarks identified in the different shape models should be accurately aligned to construct a meaningful shape model. The two registration techniques used in this study, the fiducial registration method and the ALPACA algorithm, are both landmark-based iterative closest point (ICP) registrations14,15. ICP registration is the most classical and common registration approach, and can align one set of points with another to minimize the differences between them22. In general, the fit quality of the ICP registration improved with an increase in the number of landmark points. However, an increase in the number of landmark points may increase the computational load, necessitating additional processing time. Furthermore, manual configuration of many landmarks is laborious and requires an automated approach. The ALPACA algorithm used in this study is a fully automated approach that can set a large number of landmarks (> 500 points in this case), perform ICP registration, and complete the entire process within a few minutes per one model15. In contrast, the fiducial registration method is a semiautomatic approach that requires manual landmarking. Consequently, a limited number of landmarks can be set (only nine points in the present study)14. Accordingly, our results demonstrate the best-fit quality of ALPACA registration.

Most registration methods can be classified into rigid and non-rigid subtypes14. The rigid type enables the optimal rotation, translation, and scaling of a source model to match the target by implementing ICP (i.e., the rigid type of ALPACA and the similarity type of fiducial registration)14. The nonrigid type enables a nonlinear geometric transformation to deform one object into another in a common coordinate system (i.e., the deformable type of ALPACA and the warping type of fiducial registration)14. Correspondingly, our results revealed a better fit quality for the nonrigid registration type than for the rigid type because the nonlinear geometric transformation facilitated flexible alignment to the target models. The distinction in fit quality between the rigid and nonrigid types was not clear when using the fiducial registration method compared with the ALPACA method. This lack of clarity can be attributed to the limited number of reference landmarks in the fiducial registration, which was insufficient for the construction of deformable models.

Simultaneously, the “Pinocchio effect” must be considered when interpreting the results of our registration methods23,24. One limitation of the ICP algorithm is that it uses the entire surface in the registration process, and localized prominent changes in bone shape, including those due to osteophytes (e.g., Pinocchio), can skew the registration of unaffected portions of the bone models. Considering these registration errors (i.e., the Pinocchio effect) is crucial in studies aimed at constructing rugged structures such as our knee OA models23. This has also been highlighted in previous studies that applied the SSA to OA22. Notably, differences in fit between the OA severity groups may have occurred because of the Pinocchio effect; the registration error due to this effect increases with increasing severity, further worsening the fit quality.

SSA has been previously applied to knee OA but mainly to differentiate between OA and asymptomatic bone shape. Although one study correlated SSA with the severity of knee OA, it employed two-dimensional SSA based on OA knee radiographs to examine the relationship between bilateral knee asymmetry and K–L scores21. To the best of our knowledge, 3D SSA-based quantitative methods have not been fully studied with respect to OA severity grade. The present findings provide a new perspective for the quantitative evaluation of knee OA severity.

Galván-Tejada et al.21 evaluated bilateral knee asymmetry using X-ray images of OA knees by registering the left knee into the right knee using a deformable registration approach to deform an image by modifying a cloud of control points following the maximization of a similarity measure. Several quantitative metrics were calculated to correlate with the OA K–L score and reported higher mutual information and correlation (indicating structural similarity) in the early stages and a higher mean squared error (indicating structural dissimilarity) in the advanced stages. A correlation has been described between quantitative metrics of bilateral knee asymmetry and knee OA stage25. These findings are groundbreaking. Although the methods used in previous and present studies differ, our results share some similarities with prior findings. In this study, the fit quality scores of our registration methods differed between the OA severity groups, with higher scores in the early stages and lower scores in the advanced stages. Furthermore, volume differences between the reference and target OA models exhibit similar trends.

Comparing severity groups, the distinction between K–L grades 3 and 4 was clearer than that observed between K–L grades 2 and 3. This could be attributed to the more prominent structural dissimilarity (such as profound osteophytosis) in K–L grade 4 compared with the minor and difficult-to-distinguish structural dissimilarities in K–L grades 2 and 3. Determining the primary cause of this structural dissimilarity would be beneficial. Our findings showed that volume differences between the reference and target OA models were more prominent in the outer volume than in the inner volume, indicating a higher significance of bony protrusions (such as osteophytes) than bony depressions (such as bone defects).

The osteophyte volume (protruded volume) could be quantified simultaneously using this method. Feasible results using a similar approach were also obtained in a previous study26. In the present study, volume differences between the reference and target OA models were more conspicuous in the medial portion of the knee than in the lateral portion. This indicated that the present case group included a higher proportion of patients with medial OA.

Additionally, 3D SSA examined shape differences between the OA and normal models. Several femoral features that distinguish OA models from asymptomatic ones have been reported previously18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27. Bony protrusions extending throughout the edges of the femoral cartilage plate, previously reported as the main feature27, were also confirmed in our study. We observed that these protrusions were medially dominant, probably because of the high proportion of patients with medial OA. Furthermore, the mean OA model exhibited profound bony enlargement at the proximal part of the posterior medial condyle, which is consistent with previous findings27. We also observed reduced space within the intercondylar notch, consistent with previous observations27. The expansion of the medial and lateral condyles of the femur may have contributed to these changes.

Finally, we performed PCA to assess the shape variations in the OA group. Our findings revealed shape variations in the medial condyle and enlargement of the edges of the cartilaginous plate as the first principal components. These findings align with the main characteristics used to describe the OA shape model. In general, the first component of these analyses was size variation, which was not necessarily related to disease (OA in the present case), as described in previous studies27,28. However, in our analysis, the first component corresponded to the main OA features, because the GPA-aligned PCA algorithm could initially adjust the scaling and was less affected by size variations. The second principal component in this analysis was related to the shape variation in the intercondylar notch. Notably, the reduced space within the intercondylar notch represents a secondary effect of the bony enlargement of both femoral condyles, which may be reflected in the second PCA component. The third principal component described unique bony shape changes in the lateral condyle, which were smaller and medialized in the − 2.5 SD shape. Flattening of the posterior femoral condyles, particularly the lateral condyle, observed in knee OA models, indicates increased bone remodeling20. Therefore, the unique shape variation of the lateral condyle may be influenced by bone remodeling. The distribution of PCA scores along the two main components was examined in this study. The first component was associated with OA severity. Because the first component represents the main features of OA, it may be correlated with OA severity.

The present study had some limitations. First, the sample size was too small for adequate statistical evaluation. In addition, as we focused on the correlation between the SSA and OA severity, our cohort included patients with knee OA of K–L grades 2–4. The entire spectrum of OA and normal models in the same age group should be examined and categorized based on the OA severity grades. Second, we evaluated only the distal femur; other bones, including the proximal tibia, could not be evaluated. Future studies should evaluate these bones. Third, although we evaluated the subchondral bone structure, we could not evaluate the cartilage in the femur models. Fourth, this study used manual ROI selection to ensure careful initial characterization, because a validated automated segmentation tool for our conditions was not available at that time. Currently, automatic segmentation methods are preferred in the medical imaging research domain owing to their advantages in terms of time savings, reliability, and reproducibility. Therefore, future studies should implement and compare automated segmentation methods to reduce inter-reader variability and improve scalability. Finally, this was a pilot study and did not present novel data supporting the prediction of differences based on disease severity. Future studies should extend this pilot study to include prognostic analyses (e.g., outcome prediction and longitudinal follow-up) and larger cohorts to evaluate the clinical utility. Cartilage thickness may provide additional information for the optimal evaluation of OA.

Conclusions

The efficacies of several registration techniques for femur models were assessed with respect to OA severity. Our results reveal the best-fit quality of deformable ALPACA registration. Furthermore, the fit quality of our techniques and the volume differences between the reference and OA models varied depending on OA severity. In the 3D SSA, the mean OA model demonstrated bony enlargement at the edges of the cartilage plate, which was also identified as a major component associated with OA severity in our GPA-aligned PCA. Further studies are required to assess the feasibility of our registration method and SSA with respect to OA severity.

Materials and methods

Participants and image acquisitions

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Saitama Medical University Hospital (approval number 2023-085). The requirement for informed consent was waived by the Research Ethics Committee of Saitama Medical University Hospital due to the retrospective nature of the study. All experiments were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Following institutional review board approval, we identified patients who underwent knee MRI between January 2017 and December 2017, directed by the Department of Orthopedics at our hospital. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) > 40 years of age, (2) patients who underwent non-contrast non-arthrogram knee MRI and knee radiography, and (3) patients diagnosed with mild-to-severe knee OA (corresponding to K–L grades 2–4) at our institution. Patients with knee pain due to other etiologies, including fractures, infections, and posttraumatic or postoperative conditions, were excluded. Patients with suspected OA (corresponding to K–L grade 1) were also excluded. Finally, data of 58 MRI scans from 56 patients with OA femurs (11 males, 45 females; mean ± SD age, 69.9 ± 9.3 years; 24 right side femurs, 34 left side femurs, two both sides) were used in the study. These data were subsequently categorized into OA severity groups based on K–L grades (K–L grades 2–4). K–L scoring was performed by consensus between the two radiologists, who also delineated the distal femur bones. Finally, data were classified as grade 2 (23 patients), grade 3 (20 patients), or grade 4 (15 patients).

Participants aged 20–30 years with no abnormalities on MRI or clinical examination served as the control group. A normal bone model was constructed for these patients. Twenty MRI scans from 19 patients with normal femurs (eight males, one female; mean ± SD age, 23.1 ± 2.4 years; 10 right side femur, 10 left side, and one both sides) were used in the study.

All MRI scans were performed using an Ingenia Elition 3.0-T system (Philips Healthcare, Netherlands) with a vendor-specific 16-channel knee coil. In addition to a routine knee protocol that included axial, sagittal, and coronal proton density sequences, 3D T2* FFE was performed for all patients with a repetition time of 15 ms, echo time of 5 ms, flip angle of 30°, slice thickness of 1.5 mm; and a field of view of 15.0 cm.

Construction of the 3D surface models of OA femurs

Figure 3 illustrates the workflow of this study. The MRI data were loaded into the ITK-SNAP v.3.8.0 open-source software in the Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine format. The distal femur areas were manually delineated for each slice. Two radiologists with eight and seven years of experience, who were blinded to the clinical information, independently performed the delineation. Subsequently, a consensus was reached. From the delineated contours, a 3D model of each bone was reconstructed and saved as a standard 3D model in NIFTI file format (*. nii.gz). Thereafter, 3D surface models were loaded into the 3D Slicer v.5.0.3 open-source software package for further analysis.

Schematic of workflow including the construction of the reference bone model (left) and the knee osteoarthritis (OA) bone model (right). ALPACA, automated landmarking through point-cloud alignment and correspondence analysis; ICP, iterative closest point; PCA, principal component analysis; SSA, statistical shape analysis.

Construction of a normal control bone model as a reference

A mean normal femur model was constructed using GPA-based transformation. The SlicerMorph module on the 3D Slicer platform facilitated the entire process. A reference landmark set (automatic landmark placement on the surface model of the normal femur) was created using a pseudo-landmark generator. Automatic landmark registration is performed using the ALPACA algorithm. Finally, the mean model was calculated using landmarks and a GPA-based automatic transformation. The specific implementation procedure is similar to that described in the following sections (Automatic Landmark Registration using the ALPACA Algorithm and 3D SSA based on GPA and PCA).

Application of 3D registration techniques

The fiducial registration and ALPACA tool14,15 registration techniques were applied to all bone models of the OA knees, using the mean normal femur model as a standard reference. The fit quality for each method was validated using the Dice similarity score and average surface distance. This procedure was performed as previously described14,15.

Semi-automatic registration using fiducial registration tool

Landmarks were manually added to the surface of each model (Fig. 4). Nine points were marked at the metaphyseal level: anteromedial, posteromedial, anterolateral, and posterolateral positions (four points); medial and lateral epicondyles (two points); and anterior trochlear, inferior, and posterior positions in the intercondylar notch (three points). The fiducial registration wizard in the SlicerIGT module enables semiautomatic model fitting by computing the ICP-based transformation between the original and target landmark pairs (Fig. 4)14. The source model can be easily transformed into a target model by defining a set of landmark points (nine points in this case) on each surface. We tested two types of transformations for this registration tool: similarity (using translation, rotation, and scaling) and warping (using splines). Manual landmark placement was performed independently by two radiologists, who also delineated the distal femur bones. A consensus was reached.

Fiducial registration in the SlicerIGT module: a semi-automatic model fitting by computing iterative closest point-based transformation between original and target landmark pairs. Landmarks were first added manually to the surface of the reference model (mean normal femur) (a) and the knee osteoarthritis femur model (b). A total of nine points were marked: at the metaphyseal level, anteromedial, posteromedial, anterolateral, and posterolateral positions (four points); medial and lateral epicondyles (two points); and anterior trochlear, inferior, and posterior positions in the intercondylar notch (three points). We tested two types of transformation using this registration tool: similarity (using translation, rotation, and scaling) (top of c) and warping (using splines) (bottom of c).

Automatic landmark registration using the ALPACA algorithm

Reference landmark data were obtained using a pseudo-landmark generator module (Fig. 5). The pseudo-landmark generator module generated a set of landmarks at regular intervals on the external surface of the sample. Thus, we obtained a reference sample of the landmarks in the mean normal femur model.

Automated landmarking through point-cloud alignment and correspondence analysis (ALPACA) using the SlicerMorph module. A reference sample was prepared of the landmarks on the mean normal femur model (top of a) and a target model of knee osteoarthritis femur (bottom of a). Subsequently, the reference model was down-sampled into dense point clouds that were rigidly aligned (top of b) to corresponding point clouds of a target model (bottom of b) (rigid registration). Finally, the source model was further deformed to match the target model (deformable registration). Accordingly, we obtained two types of registration models: rigid (top of c) and deformable (bottom of c). The placement of landmarks in the source model was projected onto the target model using the point correspondence method.

Subsequently, we applied the ALPACA framework to the surface femur models of normal and OA knees and obtained the corresponding landmark datasets (Fig. 5)15. Specifically, point-cloud-based alignment and registration involved the following steps. First, the source (mean normal femur model) and target (each femur model of the OA knee) models were down-sampled into the corresponding dense point clouds, which were then rigidly aligned to each other (rigid registration). Subsequently, a deformable transformation was performed, wherein the source model was deformed to match the target model (deformable registration). Finally, the landmarks in the source model were projected onto the target model using the point correspondence method. Two types of registration method (rigid and deformable) were tested.

Calculation of volume differences between OA and reference models

Differences in volume were calculated by subtracting the OA models from the reference models using a 3D slicer logical operator tool (Fig. 6)13. This method is useful because the difference in volumes outside and inside the reference model, corresponding to protrusions such as osteophytes and depressions such as bone defects, can be calculated separately by changing the subtraction order. The outer and inner volumes were indicated by positive and negative values, respectively. The sum of the absolute values was calculated as the total volume difference. This analysis also calculated the medial and lateral portions of the volume difference, divided into components including the medial and lateral condyles, respectively, and excluding the intercondylar area. Furthermore, we determined and compared the averages for each severity group to determine the relationship between volume differences and OA severity.

Calculation of the volume difference between the OA and the reference models. An example of the calculated difference volumes is presented for each registration method, in the following order, from top to bottom: the similarity and warping types of fiducial registration and the rigid and deformable types of automated landmarking through point-cloud alignment and correspondence analysis. The superimposition of the OA and reference models is shown in the leftmost row (a). One model can be subtracted from another using the 3D Slicer logical operator tool. The difference in the volumes outside and inside the reference model (b and c, respectively) was calculated, and the sum of the two (d) was defined as the total volume difference. This analysis also calculated the medial and lateral portions of the volume difference, divided into components including medial and lateral condyles, respectively, excluding the intercondylar area (e).

3D SSA based on GPA and PCA

We employed a GPA-based transformation of the surface model and landmark coordinate system and compared the mean femur models of normal and OA knees to evaluate shape differences between normal and OA knees. The pointwise signed distances between the mean normal and OA surface models were calculated and projected onto the surface of the mean normal femoral model. PCA of the GPA-aligned coordinate system was applied to all OA femur models. Notably, the 3D shape variations of each principal component were visualized using the GPA and PCA modules in the SlicerMorph software. Next, we plotted the shape corresponding to mean ± 2.5 SD16. The distribution of the relevant principal components in each severity group was determined to explain the relationship between the shape variations and OA severity.

All procedures, including the statistical analyses, were performed using the SlicerMorph and SlicerIGT modules on the 3D Slicer platform. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.0514,16.

Data availability

The authors declare that all the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

References

Shane Anderson, A. & Loeser, R. F. Why is osteoarthritis an age-related disease? Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 24, 15–26 (2010).

Zhang, Y. & Jordan, J. M. Epidemiology of osteoarthritis. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 26, 355–369 (2010).

Chen, D. et al. Osteoarthritis: toward a comprehensive Understanding of pathological mechanism. Bone Res. 5, 16044 (2017).

Litwic, A., Edwards, M. H., Dennison, E. M. & Cooper, C. Epidemiology and burden of osteoarthritis. Br. Med. Bull. 105, 185–199 (2013).

Kellgren, J. H. & Lawrence, J. S. Radiological assessment of osteo-arthrosis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 16, 494–502 (1957).

Braun, H. J. & Gold, G. E. Diagnosis of osteoarthritis: imaging. Bone 51, 278–288 (2012).

Roemer, F. W., Eckstein, F., Hayashi, D. & Guermazi, A. The role of imaging in osteoarthritis. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 28, 31–60 (2014).

Ambellan, F., Lamecker, H., von Tycowicz, C. & Zachow, S. Statistical shape models: Understanding and mastering variation in anatomy. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1156, 67–84 (2019).

Diamond, K. M., Rolfe, S. M., Kwon, R. Y. & Maga, A. M. Computational anatomy and geometric shape analysis enables analysis of complex craniofacial phenotypes in zebrafish. Biol. Open. 11, bio058948 (2022).

Heutinck, P. et al. Statistical shape modelling for the analysis of head shape variations. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 49, 449–455 (2021).

Percival, C. J. et al. The effect of automated landmark identification on morphometric analyses. J. Anat. 234, 917–935 (2019).

Devine, J. et al. A registration and deep learning approach to automated landmark detection for geometric morphometrics. Evol. Biol. 47, 246–259 (2020).

Kikinis, R., Pieper, S. D. & Vosburgh, K. G. 3D Slicer: a platform for subject-specific image analysis, visualization, and clinical support. In: Intraoperative Imaging and Image-guided Therapy 277–289. (Springer, 2013).

Ungi, T., Lasso, A. & Fichtinger, G. Open-source platforms for navigated image-guided interventions. Med. Image Anal. 33, 181–186 (2016).

Porto, A., Rolfe, S. & Maga, A. M. ALPACA: a fast and accurate computer vision approach for automated landmarking of three-dimensional biological structures. Methods Ecol. Evol. 12, 2129–2144 (2021).

Rolfe, S. et al. SlicerMorph: an open and extensible platform to retrieve, visualize and analyse 3D morphology. Methods Ecol. Evol. 12, 1816–1825 (2021).

Bredbenner, T. L. et al. Statistical shape modeling describes variation in tibia and femur surface geometry between control and incidence groups from the osteoarthritis initiative database. J. Biomech. 43, 1780–1786 (2010).

Neogi, T. et al. Magnetic resonance imaging-based three-dimensional bone shape of the knee predicts onset of knee osteoarthritis: data from the osteoarthritis initiative. Arthritis Rheum. 65, 2048–2058 (2013).

Barr, A. J. et al. The relationship between three-dimensional knee MRI bone shape and total knee replacement-a case control study: data from the osteoarthritis initiative. Rheumatol. (Oxford). 55, 1585–1593 (2016).

Altman, R. D. & Gold, G. E. Atlas of individual radiographic features in osteoarthritis, revised. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 15 Suppl A, A1–A56 (2007).

Hayashi, D., Roemer, F. W. & Guermazi, A. Imaging for osteoarthritis. Ann. Phys. Rehabil Med. 59, 161–169 (2016).

Audette, M. A., Ferrie, F. P. & Peters, T. M. An algorithmic overview of surface registration techniques for medical imaging. Med. Image Anal. 4, 201–217 (2000).

Claes, P. et al. Dysmorphometrics: the modelling of morphological abnormalities. Theor. Biol. Med. Model. 9, 5 (2012).

Zelditch, M. et al. Geometric Morphometrics for biologists. A Primer (Elsevier Acad., 2004).

Galván-Tejada, J. I., Celaya-Padilla, J. M., Treviño, V. & Tamez-Peña, J. G. Knee osteoarthritis image registration: data from the osteoarthritis initiative. J. Med. Imaging. 9414, 817–823 (2015).

Morton, A. M., Akhbari, B., Moore, D. C. & Crisco, J. J. Osteophyte volume calculation using dissimilarity-excluding procrustes registration of archived bone models from healthy volunteers. J. Orthop. Res. 38, 1307–1315 (2020).

Lynch, J. T. et al. Statistical shape modelling reveals large and distinct subchondral bony differences in Osteoarthritic knees. J. Biomech. 93, 177–184 (2019).

Van Haver, A. et al. A statistical shape model of trochlear dysplasia of the knee. Knee 21, 518–523 (2014).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by JSPS KAKENHI (grant number 23K14902).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Substantial contributions to study conception: KN, YH, and EK. Study design: KN, YH, and EK. Acquisition of data: NS. Data analysis: KN, YH, SK, TS, AK, MK, and KI. Data interpretation: KN, YH, SK, TS, AK, MK, KI, and EK. Drafting of manuscript: KN, YH, and EK. Critical revision of manuscript: KN, NS, and EK.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nagawa, K., Hara, Y., Kakemoto, S. et al. Three-dimensional magnetic resonance imaging-based registration techniques and statistical shape analysis for knee osteoarthritis. Sci Rep 16, 1451 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31501-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31501-4