Abstract

Neuroinflammation is a key pathological hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Investigational and FDA approved drugs targeting inflammation already exist, thus drug repurposing for AD is a suitable approach. BT-11 is an investigational drug that reduces inflammation in the gut and improves cognitive function. BT-11 is orally active and binds to lanthionine synthetase C-like 2 (LANCL2), a glutathione-s-transferase, thus potentially reducing oxidative stress. We investigated the effects of BT-11 long-term treatment on the TgF344-AD rat model of AD. BT-11 (1) reduced spatial memory deficits, and hippocampal Abeta plaque load, and increased neuronal levels in males, and reduced microglia numbers in females, and (2) induced transcriptomic changes in signaling receptor, including G-protein coupled receptor pathways in both males and females, with changes in neurotrophic factors only in males. We detected LANCL2 in hippocampal nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions with potentially different post-translational modifications, suggesting distinct functions based on its subcellular localization. LANCL2 was present in oligodendrocytes, indicating a role in oligodendrocyte function. To our knowledge, these last two findings have not been reported. Overall, our data support that targeting LANCL2 with BT-11 improves cognition and reduces AD-like pathology potentially by modulating G-protein signaling. LANCL2’s localization in oligodendrocytes suggest a possible role oligodendrocyte function that warrants further investigation. Our studies contribute to the field of new immunomodulatory AD therapeutics and establish LANCL2 as a promising therapeutic target meriting further mechanistic investigation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chronic neuroinflammation is a key factor in AD progression1. Focusing on regulators of neuroinflammation for treatment of AD is an important avenue of current research. Lanthionine synthetase C-like 2 (LANCL2) is a novel regulator of inflammation, and BT-11 is a LANCL2 activator. BT-11 was selected based on a computational drug repurposing approach for AD candidates, and on its immunomodulatory effects knowing that inflammation plays a critical role in AD. BT-11 is currently in clinical trials for Irritable Bowel Disease (IBD)2,3. BT-11 [N,N-bis(benzimadzolylpicolinoyl)piperazine] is a synthetic organic compound derived from the dried root extract of the Polygala tenuifolia wildenow plant4,5. BT-11 was originally developed by designing analogs of abscisic acid (ABA), the endogenous ligand for LANCL2. Molecular docking and binding assays to LANCL2 revealed that BT-11 was the top lead compound4.

Multiple studies showed beneficial effects of BT-11 on cognitive deficits and in the context of aging but none, to our knowledge, in the context of AD. One study used an amnesia model in both male and female pregnant Sprague–Dawley rats and found that a 10 mg/kg intra-peritoneal (i.p.) injection of BT-11 recovered performance on passive avoidance and water maze tasks. 5. Another group looked at the effect of BT-11 on elderly humans6. This randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled comparison study used the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD) and the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE). Total CERAD scores were significantly improved in the BT-11 treatment group as compared to placebo, demonstrating that BT-11 enhances cognitive functions in aged adults6. These studies merit further investigation of BT-11 in cognition as it occurs in AD. To our knowledge, our studies address for the first time the impact of BT-11 on AD-relevant spatial memory deficits and hippocampal pathology.

At the diagnostic stage, AD patients already show significant cognitive deficits, and substantial accumulation of brain pathology. This makes developing and investigating therapeutics very difficult and suggests a need for examining the neuropathology of AD in transgenic animal models7. We used the TgF344-AD rat model that develops AD pathology including amyloid plaques, tauopathy, gliosis, neuronal loss, and cognitive deficits in a progressive age-dependent manner, an aspect of AD that is difficult to reproduce in animal models8,9. TgF344-AD rats express the human Swedish amyloid precursor protein (APPsw) and ∆ exon 9 presenilin-1 (PS1-∆E9) genes, driven by the prion promoter8. BT-11 was administered orally and daily (8 mg/kg bw/day) for a period of 6 months to transgenic and wild type male and female rats, and its effects were assessed on hippocampal-dependent spatial memory and AD-pathology.

In summary, our studies established that: (1) long-term oral treatment of TgF344-AD rats with BT-11 improved spatial memory and reduced Aβ plaque load and increased neuronal levels in males, and reduced microgliosis in females; (2) hippocampal LANCL2 is localized in the nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions with possible localization-specific post-translational modifications, such as myristoylation, phosphorylation and/or ubiquitination; (3) LANCL2 is specifically located in hippocampal oligodendrocytes, and not in neurons, astrocytes or microglia. Together, our results strongly support the potential of BT-11 to treat AD, and the need to continue investigating the role of the novel LANCL2 pathway in AD.

Results

BT-11 treatment improved spatial learning in 11-month male TgF344-AD rats

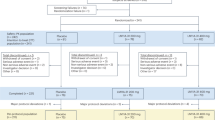

Our studies included four groups of rats for each sex: WTNT—Wild-type not treated; TGNT—transgenic not treated; WTTR—Wild-type BT-11 treated; TGTR—transgenic BT-11 treated. After six consecutive months of drug treatment, all rats were assessed for cognitive behavior at 11 months of age (Fig. 1a), as previously described by our group10. For this study, three different cohorts of rats were included, and males and females were analyzed separately. Across these cohorts there were WTNT (n = 14), TGNT (n = 17), WTTR (n = 13), and TGTR (n = 13) males, as well as WTNT (n = 28), TGNT (n = 16), WTTR (n = 12), and TGTR (n = 11) females. To show that any differences in behavior were due to cognitive abilities and not movement or motivation, we analyzed the total path length of all rats in their habituation trial. During this trial, all rats should be freely exploring the arena. There were no significant differences in path length across all male groups and across all female groups (Supplemental Table 1, Supplemental Fig. 1). We also assessed another parameter, which is latency to first entrance that measures the time the rats take to enter the shock zone, thus does not stand for their performance over the rest of the trial. Because all rats are naive to the shock in the first trial, latency to first entrance was not statistically different between groups (Supplemental Fig. 2).

BT-11 improved spatial learning in TgF344-AD males. (a) Experimental design. All rats were exposed to the aPAT at 11 months of age. Rats were tasked with avoiding the shock zone over a course of six trials. The measure used to analyze this data was percent (%) time in the target zone during a 600 s trial. Following behavioral analysis, the rats were sacrificed (details under methods). (b) a significant difference was seen during the first three trials (early acquisition) in which the WTNT rats outperform the TGNT rats. (c) there was no genotype difference between WTTR and TGTR rats. (d) TGTR rats outperformed the TGNT rats. (e) there was no treatment difference between WTTR and WTNT rats. (f) Representative track tracings of a WTNT and a TGNT male performance for trial 3. Red lines represent the bounds of the shock zone and red circles represent each shock that was given. Two-way ANOVAs with Tukey’s post hoc test with GraphPad Prism 9 software were used, *P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, **** P < 0.0001. EA, early acquisition; AP, asymptotic performance; WTNT—wild-type not treated; TGNT—transgenic not treated; WTTR—wild-type BT-11-treated; TGTR—transgenic BT-11-treated; t = training effect, g = genotype effect, d = drug effect; aPAT, active place avoidance test; RNAseq, RNA sequencing; IHC, immunohistochemistry.

BT-11 did not improve spatial learning in TgF344-AD females. All females showed learning across six trials with a significant trial effect. The measure used to analyze this data was percent (%) time in the target zone during a 600 s trial. There were no significant genotype differences between (a) WTNT and TGNT, (b) WTTR and TGTR, nor treatment differences between (c) TGNT and TGTR, (d) WTNT and WTTR. (e) Representative track tracings of a WTNT and a TGNT female performance for trial 3. Red lines represent the bounds of the shock zone and red circles represent each shock that was given. Two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test with GraphPad Prism 9 software were used, **** P < 0.0001. EA—early acquisition; AP—asymptotic performance; WTNT—wild-type not treated; TGNT—transgenic not treated; WTTR— wild-type BT-11-treated; TGTR—transgenic BT-11-treated; t = training effect.

All male rats were able to learn across the six trials as showed by a significant training effect [Fig. 1b to Fig. 1e, [F (3.367, 178.5) = 47.52, p < 0.0001]. There was a significant deficit in spatial learning in the TGNT male rats as compared to the WTNT male rats in the measure of percent time in the target zone with significant post-hoc effects in the first two trials [Fig. 1b, genotype effect, F (1, 29) = 9.492, p < 0.01]. This deficit was mitigated by BT-11 treatment, with TGTR male rats performing significantly better than TGNT male rats [Fig. 1d, drug effect, F (1, 28) = 6.308, p < 0.05]. There were no significant differences between WTTR and TGTR (Fig. 1c) or WTNT and WTTR males (Fig. 1e). Representative traces from trial three in a WTNT and TGNT male rats are shown in Fig. 1f.

All female rats were able to learn across the six trials as shown by significant training effect [Fig. 2a to d, F (1.903, 119.9) = 24.83, p < 0.0001]. However, there were no significant genotype or behavior differences across all female groups (Fig. 2, Supplemental Table 2). Representative traces from trial three in a WTNT and TGNT female rats are shown in Fig. 2e.

BT-11 treatment reduced Aβ plaque load in 11-month old male TgF344-AD rats

We assessed Aβ plaque burden in TGNT and TGTR rats by IHC analyses (mouse monoclonal antibody 4G8) of the dorsal hippocampus as well as across each of its four subregions: CA1, CA3, DG and SB (Fig. 3). In each group, 8 or 9 rats were analyzed. Earlier studies reported that there are no Aβ plaques in WT rats of this AD model, as they do not express the transgenes8 Images of dorsal hippocampi from a TGNT and a TGTR male are shown in Fig. 3a and b, respectively. Aβ plaque load was quantified as % area, which is the % area of the dorsal hippocampus that has Aβ signal. TgF344-AD males treated with BT-11 (n = 8) showed reduced plaque load as compared to TGNT males (n = 8) in the dorsal hippocampus [Fig. 3c, t = 1.981, df = 14, p < 0.05,]. There were no significant differences for each of the hippocampal subregions: CA1 (p = 0.535, t = 0.637), CA3 (p = 0.714, t = 0.375), DG (p = 0.289, t = 0.570), SB (p = 0.734, t = 0.347). Females were also assessed for Aβ plaque load and there was no significant difference between TGNT (n = 9) and TGTR (n = 8) rats in the dorsal hippocampus (Fig. 3d, Supplemental Table 3, p = 0.201, t = 0.863), or in each of its subregions: CA1 (p = 0.736, t = 0.343), CA3 (p = 0.781, t = 0.283), DG (p = 0.991, t = 0.012), SB (p = 0.178, t = 1.413). There was no treatment difference in plaque size distribution across TG groups (Supplemental Fig. 3).

BT-11 treatment reduced Aβ plaque load in 11-month old male TgF344-AD rats. Immunohistochemical analyses for Aβ plaque load (red, 4G8 antibody) and DAPI (blue) in (a) TGNT and (b) TGTR males. White arrows point to Aβ plaques. Scale bar = 1000 µm. (c) Plaque load was reduced in the hippocampus of TGTR (n = 8) compared to TGNT (n = 8) males. BT-11 treatment reduced percent (%) area of Aβ signal in the dorsal hippocampus of TGTR male rats. (d) There was no significant different in Aβ plaque load in the hippocampus of TGTR (n = 9) compared to TGNT (n = 8) female rats. Unpaired one-tail t-tests with Welch’s corrections were used for quantification, *P < 0.05. For simplicity, error bars are shown in one direction only. TGNT—transgenic not treated; TGTR—transgenic BT-11 treated. CA = cornu ammonis, DG = dentate gyrus, SB = subiculum.

BT-11 treatment reduced total and ramified microglia levels in female TgF344-AD rats

The three morphological states of microglia (Fig. 4a) were quantified in WTNT (males n = 8; females n = 7), TGNT (males n = 8; females n = 9), WTTR (males n = 8; females n = 6), and TGTR (males n = 7; females n = 8) rats by IHC with the rabbit antibody Iba1. Microglia levels were quantified as % area, standing for the % of the total area with positive signal. Levels of all and each subtype of microglia were analyzed in dorsal hippocampi as well as across their four subregions: CA1, CA3, DG and SB. Representative IHC images for females and males are shown in Fig. 4b, b′–g, g′. Statistical analyses graphs are shown in Fig. 4h–k for males and Fig. 4l–o for females.

BT-11 treatment reduced total and ramified microglia levels in female TgF344-AD rats. (a) Microglia immunohistochemical analyses with the Iba1 antibody (green) showed three distinct types of microglia morphology expressed by specific form factor ranges for circularity: ramified, reactive and amoeboid (standard schematic reused with permission)18. Iba1 staining is shown for TGNT (b, b′) and TGTR (c, c′) females and males, respectively. Co-localization staining for Iba1 (green) Aβ plaques (red) and nuclei (DAPI, blue), is shown for TGNT (d, d′) and TGTR (e, e′) females and males, respectively. White arrows point to Aβ plaques. Bottom panels (f, f′) and (g, g′) represent the magnification of the respective small white boxes depicted in (d, d′) and (e, e′). Scale bar = 1000 µm (b, b′–e,e′), and 10 µm (f, f′, g, g′). There was no significant differences in male rats in all four groups for % area of total (h) or ramified microglia (I), in male rats. Male TgF344-AD rats had increased % area of reactive (j) and amoeboid (k) microglia in the dorsal hippocampus as compared to WT rats. Female TGNT rats had increased % area of Iba1 positive signal across the dorsal hippocampus for total (l), reactive (n), and amoeboid (o) microglia as compared to WTNT rats. BT-11 treatment reduced total (l) and ramified (m) microglia levels in female TGTR rats. Ordinary two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc tests were used for quantification. For simplicity, error bars are shown in one direction only. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. TGNT—transgenic not treated; TGTR—transgenic BT-11 treated. CA = cornu ammonis, DG = dentate gyrus, SB = subiculum. t = treatment effect, g = genotype effect.

Male TgF344-AD rats had increased % area of reactive [F (1, 27) = 12.47, p = 0.002] and amoeboid [F (1, 26) = 9.682, p = 0.005] microglia in the dorsal hippocampus as compared to WT rats (Fig. 4j and k). There were also significant genotype differences across multiple subregions with TgF344-AD rats having increased microglia % area as compared to WT rats: CA1 reactive [F (1, 25) = 5.577, p = 0.026], CA3 amoeboid [F (1, 25) = 4.858, p = 0.037], DG reactive [F (1, 26) = 9.603, p = 0.005], DG amoeboid [F (1, 26) = 4.189, p = 0.051], with no changes in the subiculum (Supplemental Table 4). There were no significant differences induced by BT-11 treatment across all male groups (Supplemental Table 4).

Female TGNT rats had increased % area of Iba1 positive signal across the dorsal hippocampus for total microglia [F (1, 26) = 4.603, p = 0.041], reactive [F (1, 26) = 6.840, p = 0.015], and amoeboid [F (1, 26) = 4.665, p = 0.041] as compared to WTNT rats (Fig. 4l, n–o, Supplemental Table 4). Significant genotype differences were also detected in the CA1, CA3, DG, and SB subregions (Supplemental Table 4). Additionally, BT-11 treated TgF344-AD females showed significantly reduced total microglia [F (1, 26) = 4.168, p = 0.052] and ramified microglia [F (1, 26) = 5.402, p = 0.028] levels in the dorsal hippocampus compared to TGNT female rats. Significant BT-11 treatment differences were also observed for CA1 ramified [F (1, 26) = 5.489, p = 0.027], CA3 total [F (1, 26) = 4.455, p = 0.045] and ramified [F (1, 26) = 5.216, p = 0.031], and SB ramified microglia levels [F (1, 26) = 6.373, p = 0.018], (Supplemental Table 4).

Mature neurons are more abundant in the DG of TGTR than in TGNT male rats

To assess hippocampal neuronal numbers in male and female WTNT (males n = 7; females n = 7), TGNT (males n = 7; females n = 7), WTTR (males n = 8; females n = 6), and TGTR (males n = 7; females n = 7) rats, we used the NeuN antibody, which detects post-mitotic mature neurons (Fig. 5a and b, Supplemental Fig. 4). In Fig. 5, the images on the right represent the NeuN positive signal for quantification from immunofluorescent images. There was no significant genotype (g) or treatment (t) effects on neuronal counts/nm2 in the dorsal hippocampus of male rats [F (1,25) = 0.880, p = 0.357] (g), and [F (1, 25) = 2.887, p = 0.102] (t). However, BT-11 treated TgF344-AD male rats had increased neuronal counts/nm2 in the DG hippocampal subregion as compared to TGNT males [F (1, 25) = 6.262), p = 0.019] (Fig. 5c). We analyzed NeuN counts across all hippocampal subregions, including the hilar region and the granule cell layer and are detailed in Supplemental Table 5.

The number of mature neurons in the hippocampal dentate gyrus (DG) of TGTR males is higher than in TGNT males. NeuN staining (green) is shown for TGNT (a, n = 7) and TGTR (b, n = 7) males. Images on the right represent positive NeuN signal derived for quantification. Scale bars = 1000 μm. TGTR males had increased NeuN counts/nm2 in the DG hippocampal subregion than TGNT males (c). There was no significant difference in NeuN count/nm2 in the DG region in female rats (d). Ordinary two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc tests were used for quantification. For simplicity, error bars are shown in one direction only. Hippocampi were also stained for phosphoTau (red, AT8 antibody). There were no significant differences of hyperphosphorylated tau levels in male rats across genotypes and treatments. TGNT—transgenic not treated; TGTR—transgenic BT-11 treated. DG = dentate gyrus; t = treatment effect.

There were no significant genotype or treatment effects on neuronal counts/nm2 in the dorsal hippocampus of female rats [F(1, 23) = 0.916, p = 0.349] (g) and [F (1, 23) = 0.579, p = 0.454] (t). Additionally, there were no significant genotype or treatment effects across all hippocampal subregions, including the DG hippocampal subregion (Fig. 5d and Supplemental Table 5).

Hyperphosphorylated tau levels were equivalent in all groups of rats

We assessed hyperphosphorylated tau levels with the mouse monoclonal AT8 antibody (Supplemental Fig. 5). There were no significant treatment (t) or genotype (g) differences of hyperphosphorylated tau levels in male rats (p = 0.158 (g), p = 0.996 (t)) or female rats (p = 0.512 (g), p = 0.203 (t)) of the four groups WTNT (males n = 7; females n = 7), TGNT (males n = 7; females n = 7), WTTR (males n = 8; females n = 6), and TGTR (males n = 7; females n = 7) (Supplemental Table 6a). Additionally, there were no significant treatment differences in hyperphosphorylated tau levels in male or female TgF344-AD rats across multiple subregions: CA1, CA3, DG, SB, HL, and GCL (Supplemental Table 6bh).

BT-11 induced changes in gene expression profiles and enriched pathways in TGTR vs TGNT rats

To gain initial mechanistic insights, we performed transcriptomic analysis. The differential expression profiles and enriched pathways in the dorsal hippocampi of TGTR vs TGNT male and female rats were assessed. Gene analysis generated a list of 11,671 genes for males and 12,561 genes for females. There were 195 genes in males and 77 genes in females that were differentially expressed in TGTR vs TGNT rats, considering the following parameters: P < 0.05, and a fold-change \(\ge\) 1.5 or \(\le\)-1.5. There were 12 overlapping genes between males and females (Fig. 6a). In males, 123 genes were downregulated while 75 were upregulated, and three overlapping likely represented splice variants. In females, 56 genes were downregulated while 21 were upregulated (Fig. 6a–c).

BT-11 treatment alters the transcriptome of male and female TgF344-AD rats. We used RNA sequencing (RNAseq) to analyze the transcriptomes of BT-11 treated and untreated TgF344-AD males and females separately. Five biological replicates for TGNT and TGTR males as well as females were analyzed. (a) Venn diagram of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) shows a total of 195 genes for TGTR males (lavender), and 77 genes for TGTR females (yellow), with 12 genes overlapping between males and females (brown). (b) Male and (c) female volcano plots depicting significant (red) and non-significant (blue) DEGs from treated vs untreated TgF344-AD rats. Each point represents one gene. Y-axis, P values, x-axis, fold change. (d) Male upregulated enriched neurotrophin receptor binding STRING network, the color of edges represents the source of evidence (e), Male and (f), female enriched pathway analysis of TGTR vs TGNT rats with the Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) for transcriptional data. The size of circles represents the count of genes in the pathway differentially regulated. Color represents the P adjusted value of the pathway. Red boxes show relevant pathways relating to transporter and receptor activity. TGNT—transgenic not treated; TGTR—transgenic BT-11 treated, BDNF—brain derived neurotrophic factor, Ntf3—neurotrophin 3, Ntrk1—neurotrophic receptor tyrosine kinase 1 , Nradd—neurotrophin receptor alike death domain protein.

Enriched pathways in males and females were determined by gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA, Fig. 6e–f). Some enriched pathways for males included salt transmembrane transporter activity, signaling receptor regulator activity, receptor ligand activity, signaling receptor activator activity, and transmembrane transporter activity. Some enriched pathways for females included passive transmembrane transporter activity, G protein-coupled receptor activity, G protein-coupled peptide receptor activity. Further STRING analysis demonstrated an enriched neurotrophin receptor binding network, including brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), Neurotrophin-3 (Ntf3), and high-affinity nerve growth factor receptor (Ntrk1) in the male data, but not the female data (Fig. 6d, strength 1.88, signal 0.83, FDR 0.0023).

LANCL2 total, cytoplasmic and nuclear levels in TgF344-AD male and female rats

Depending on post-translational modifications, LANCL2 is found in multiple locations of the cell, and this likely affects its function. We determined LANCL2 total, nuclear, and cytoplasmic fraction levels in dorsal hippocampi of male and female rats, by subcellular fractionation across each of the four groups WTNT, WTTR, TGNT, and TGTR, three rats per group (Fig. 7). LANCL2 levels associated with the plasma membrane were not detectable.

LANCL2 total, cytoplasmic and nuclear levels in TgF344-AD untreated and BT-11 treated male and female rats. Male and female rat dorsal hippocampal tissue homogenates were used to assess BT-11 treatment effects on the subcellular localization and levels of (a) total, (b) cytoplasmic and (c) nuclear LANCL2 by western blot analysis. The percentage of the pixel ratio for LANCL2 over the respective loading controls, GAPDH for cytoplasmic fractions (d, f) and lamin B1 for the nuclear fraction (e, g). Analysis was performed for the four groups WTNT, WTTR, TGNT, TGTR at 11 months of age, three rats per group. Signal was quantified using relative density measurement on ImageJ. Male data is shown in (d, e). Female data is shown in (f, g). Values are means + SEM. Significance (asterisks shown on graphs) represent post-hoc effects following an ordinary two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc tests. *P < 0.05. WTNT, wild-type not treated, TGNT, transgenic not treated, WTTR, wild-type BT-11 treated, TGTR, transgenic BT-11 treated; H = high molecular weight LANCL2; L = low molecular weight LANCL2.

Interestingly, besides the ~ 51 kDa band corresponding to the reported LANCL2 molecular mass, an additional band was detected in the total lysate at ~ 79 kDa (Fig. 7a). An increase of 28 kDa in LANCL2 suggests a post-translational modification. While this is a relatively high shift, there is the potential for ubiquitination or hyperphosphorylation to be involved.

In the cytoplasmic fraction of both males and females, a LANCL2 double band was detected at ~ 51 kDa (Fig. 7b). This could represent myristoylation, which is a known modification of LANCL2 that localizes the protein to the plasma or intracellular membranes. The addition of a myristol group would add ~ 0.2 kDa per group to the protein. The molecular mass shift seen in the doublet could also be due to phosphorylation, which adds ~ 0.8 kDa per phosphate group to a protein. There is also a ~ 36 kDa band detected in the cytoplasmic fraction that could be a product of cleavage or degradation. In the cytoplasmic fraction, TgF344-AD females have significantly higher levels of LANCL2 than WT females regardless of treatment [F (1, 8) = 9.442, p = 0.015] (Fig. 7f). There are no significant differences in LANCL2 levels in the male cytoplasmic fraction (Fig. 7d, Supplemental Table 7b).

The nuclear fraction (Fig. 7c) shows the ~ 51 kDa LANCL2 band, and the ~ 79 kDa band that is not detected in the cytoplasmic fraction (Fig. 7a). It is possible that different post-translational modifications, such as ubiquitination, phosphorylation and myristoylation, occur on LANCL2 in different intracellular compartments. Female TgF344-AD rats have higher LANCL2 levels in the nuclear fraction than WT females [F (1,8) = 12.25, p = 0.008] (Fig. 7g). This is not seen in males (Fig. 7e, Supplemental Table 7C). The whole western blots with the LANCL2 signal are shown in Supplemental Fig. 6–11.

LANCL2 is detected in oligodendrocytes in dorsal hippocampi of TgF344-AD and WT rats.

The cell type localization of LANCL2 in the dorsal hippocampus is only predicted by high throughput transcriptomic analyses

(www.proteinatlas.org/)11. To further investigate this question, IHC was performed on dorsal hippocampal sections including the surrounding corpus callosum. Sections were co-immunostained with the LANCL2 antibody together with each of the cell type specific antibodies: NeuN for neurons, Iba1 for microglia, GFAP for astrocytes, or Olig2 for oligodendrocytes (Supplemental Table 8). WTNT and TGNT male rats (three rats per group) were included in the analysis. LANCL2 cell type localization was similar across each group.

LANCL2 signal was predominantly detected in oligodendrocytes, with weaker labeling observed in proximity to astrocytes, neurons, and microglia, suggesting potential spatial interactions rather than direct expression in these cell types (Fig. 8a-p). Olig2 is a transcription factor, and its signal is mainly localized in the nucleus while LANCL2 stain is found mostly in the cytoplasm leading to the signal appearing as red LANCL2 wrapped around the green Olig2 of the same cell (Fig. 8h and p)11,12 IHC images of the dorsal hippocampus stained with the same antibodies are shown in Supplemental Figs. 12 and 13.

LANCL2 is localized in oligodendrocytes in the dorsal hippocampus of WT and TgF344-AD male rats. LANCL2 is detected in oligodendrocytes found in the dorsal hippocampus and neighboring corpus callosum of WTNT (a–h) and TGNT (i–p) male rats. Co-localization of LANCL2 (red) with different cell specific markers (green): (a, i) GFAP for astrocytes, (b, j), NeuN for neurons, (c, k), Iba1 for microglia, and (d, l) Olig2 for oligodendrocytes. Bottom panels (e–h) represent the magnification of the respective small white boxes depicted in (a–d). Bottom panels (m–p) represent the magnification of the respective small white boxes depicted in (i–l). Scale bar = 1000 µm (a–d, i–l), and 10 µm (e–h, m–o). LANCL2 red staining is wrapped around the green Olig2 nuclear stain, clearly shown in (h) and (p). White arrows point to the cell type staining shown in green, yellow arrows point to LANCL2 staining shown in red. WTNT, wild type not treated, TGNT, transgenic not treated.

Discussion

Overall, our studies investigated the effects of long-term oral treatment with the LANCL2 activator BT-11, on cognitive performance and AD pathology in male and female TgF344-AD rats and WT controls. The findings indicate that BT-11 shows sex-specific effects on neurodegeneration and cognition. In males, it improves spatial memory, reduces hippocampal Aβ plaques, and increases neuronal levels, suggesting direct neuroprotective effects. In contrast, females show reduced microglial activation without cognitive improvement at the tested timepoint, indicating an immunomodulatory mechanism. Moreover, we characterized LANCL2 cellular and subcellular localization in the hippocampus.

Hippocampal-dependent spatial learning was assessed with the active place avoidance task (aPAT)13. As previously described, rats learn to avoid a shock zone by associating it with cues placed around the behavior testing room. This makes the task hippocampal-dependent, given that the hippocampus plays a key role in remembering past locations14. The 11-month TgF344-AD male rats showed a significant deficit in performance as compared to WT controls. Interestingly, the same deficit was absent in the female rats. The initial report of this model found no significant behavioral sex differences9,15. However, more recent studies looking at a range of behavioral tasks demonstrated significant differences in cognitive performance between male and female TgF344-AD rats, such as females showed no deficit in a buried food task at 12 months of age, while males exhibited a significant deficit9. Additionally, our previous studies demonstrated that female TgF344-AD rats outperform males in the aPAT with no significant behavior changes in either group at 9 months of age16. There are conflicting results on the behavioral characterization of the TgF344-AD rats that seem to relate to the task being evaluated. For example, in a study that focused on females, TgF344-AD rats showed spatial memory impairment in a Morris water maze at 12 months, however showed no significant deficits at 12 months during the acquisition phase of a radial arm water maze task17. These studies suggest that the behavior task chosen to assess spatial learning influences the behavior performance. Thus, in future studies it will be important to use a variety of behavioral tasks to show changes in spatial learning.

While the male TgF344-AD rats performed worse on the aPAT than WT rats, the TGTR rats performed significantly better than the TGNT rats. These results show that BT-11 treatment starting early at 5 months of age, mitigated the spatial learning deficits showed in male TGNT rats. Many AD patients maintain cognitive function demonstrating a potential ‘resilience’ to AD pathology, and our previous study showed improved behavior performance in Tg-F344AD females despite increased pathology as compared to males18,19.

Significantly, a key factor limits the drug translatability of female rats as compared to male rats for both behavior and pathology effects. Female rats, unlike humans, undergo estropause instead of menopause. Estropause occurs around 9–12 months of age, corresponding to when our rats were evaluated. Unlike menopause where there is a significant loss of estrogen signaling, estropause is characterized by moderate to high levels of estrogen20. Importantly, estrogen is neuroprotective, increasing cognitive performance and reducing oxidative stress21. This creates a potential source of protection against neurodegeneration in the TgF344-AD females, not present in males and not recapitulated in humans. As such, the lack of BT-11 cognitive effect in females may not indicate a lack of efficacy, but rather the presence of a ceiling effect in behavior performance at this stage of disease. In contrast, male transgenic rats demonstrated clear spatial learning deficits, providing a window in which BT-11 could exert measurable benefits. Since we are focused on the effect of drugs with an eventual goal of translation, future studies could include models to induce menopause such as ovariectomy or drug induced menopause20. However, these methods can introduce additional variables to the study. For the sake of translatability, it is still important to evaluate both male and female rats despite this key difference. The sex-dependent effects of BT-11 may be explained by sex-specific mechanisms mediated by BT-11, as well as possible differences in drug metabolism by males and females. In our study we showed distinct differential gene expression in males and females that may point to different mechanisms to be further explored. While sex differences in pharmacokinetics in general has been well documented, to our knowledge, sex differences in BT-11 metabolism have not been defined22.

There was a significant reduction of hippocampal Aβ plaque load in TGTR compared to TGNT males. In addition, the number of mature neurons in the hippocampal dentate gyrus (DG) of TGTR males was higher than in TGNT males, supporting a relationship between neuronal numbers and improved spatial memory. This shows that BT-11 treatment likely ameliorates cognitive deficits by reducing classical AD pathology in male TGTR rats. It is also possible that BT-11 modulates adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Future studies could assess markers such as doublecortin in the context of BT-11 treatment to distinguish between neuroprotection and enhanced neurogenesis. There was no BT-11 treatment effect on Aβ plaque load or neuronal levels in female transgenic rats, corresponding to no effect of the drug on spatial memory.

Microglia analysis showed an increase in reactive and amoeboid microglia in males in the dorsal hippocampus of TgF344-AD rats compared to WT rats. BT-11 treatment had no effect on microglia in males. However, female TgF344-AD rats showed an increase in total, reactive and amoeboid microglia in the dorsal hippocampus as compared to WT rats, as well as a reduction in total and ramified microglia with BT-11 treatment. BT-11 treatment in female TgF344-AD rats also caused a reduction in ramified microglia in the CA1, CA3 and subiculum. Ramified microglia are commonly associated with surveillance23. There were no significant treatment effects on reactive or amoeboid microglia, which are known to be involved in phagocytic activity and associated with disease24. There are many ways to analyze microglia and microglial signaling including presence of inflammatory markers such as CD68 as well as utilizing single cell sequencing to assess the transcriptomic nature of different types of microglia24,25,26. Future studies focusing on more detailed and multiple ways of assessing microglial activity and function should provide additional support and explanations for our studies. Moreover, as previously mentioned, BT-11 reduces inflammation in the gut27. It is possible that BT-11 influences inflammation in TgF344-AD rats in ways that may not be demonstrated by analyzing microglial levels. It may relate to an overall reduction in systemic inflammation, or presence of other immune cells, such as T cells, and other signaling pathways. Peripheral cytokines can reach the brain and regulate microglial activation via established humoral relay routes28. Thus, BT-11 may remodel microglia indirectly via LANCL2-dependent systemic cytokine and redox signaling axes. Additionally, LANCL2 activation in other brain cell types, such as oligodendrocytes may lead to the local release of factors that modulate microglial phenotype29.

There were no genotype or treatment changes detectable in hyperphosphorylated tau in male or female rats. Previous studies on this TgF344-AD rat model suggest that the 11-month timepoint is too early to demonstrate tau pathology, proposed in the initial report to be detected at 16 months of age15. A more recent study showed increased levels of hyperphosphorylated tau in rats aged 18–21 months and no change in rats 6–8 months of age15,30.

So far, we have shown that oral treatment with BT-11 improved cognitive deficits and reduced some of the pathological hallmarks of AD in the TgF344-AD rat model. These observations raise several possibilities. It is plausible that BT-11’s cognitive benefits in males stem primarily from its impact on classical AD pathology, while in females, the drug may be altering the neuroimmune environment in ways that are protective or preventive, with potential benefits that emerge later in disease progression. Alternatively, the lack of cognitive improvement in females could indicate that microglial modulation alone is insufficient to produce behavioral changes at the tested timepoint, or that a longer duration may be required to observe downstream cognitive effects due to a possible ceiling effect in behavior at this disease stage.

Taken together, these data highlight that BT-11’s mechanisms of action and therapeutic efficacy are sex-specific, with males exhibiting greater benefit in terms of conventional cognitive and pathological outcomes, and females demonstrating distinct immunomodulatory responses. These findings underscore the critical need to consider sex as a biological variable in the development and evaluation of therapeutic strategies for neurodegenerative diseases.

Based on these findings, we investigated the molecular and cellular mechanisms potentially mediating the effects of BT-11 treatment on the dorsal hippocampus of WT and TgF344-AD rats. Specifically, we focused on the dorsal hippocampal expression as well as the intracellular and cell type localization of the BT-11 target LANCL2, to gain a better understanding of its role in AD.

Firstly, we investigated potential central nervous system (CNS) effects of BT-11, by comparing mRNA expression in the dorsal hippocampus of TGTR vs TGNT rats. Treating TgF344-AD rats orally with BT-11 led to enrichment in G protein-coupled receptor and other signaling receptor pathways. This suggests that activating LANCL2 with BT-11 likely works through these signaling mechanisms in the brain in addition to systemic effects.

Notably, the neurotrophin receptor binding network was enriched in male treated rats but not in the females. This may point to a possible mechanism by which males specifically show improved behavior and increased neuronal levels. Of this network, Bdnf was modestly up-regulated, aligning with work demonstrating that elevating BDNF (via neural stem cell–derived BDNF or direct BDNF delivery) restores synaptic density and rescues memory in AD models31. Additionally of this network, Ntf3, which is also upregulated, has shown improvement in cognition in APP/PS1 mice32. Outside of neurotrophic factors, Wnt3a (wingless-type MMTV integration site family, member 3A) and Wnt16 (wingless-type MMTV integration site family, member 16) were up-regulated, concordant with evidence that activating Wnt (wingless) signaling preserves synapses and reverses cognitive deficits in amyloid models33,34. Together, these shifts identify mechanistic axes with precedent for producing functional benefit, and provide a plausible transcriptional correlate of the male-restricted phenotype. It is possible that BT-11 affects other LANCL2-independent pathways. Future work will investigate neurotrophic and Wnt signaling as suggested by our RNA sequencing data and key enzymes involved in Aβ turnover (BACE1, neprilysin, IDE) as it relates to our amyloid plaque load findings in male rats. Moreover, LANCL2-associated signaling pathways, such as Akt/mTOR, glutathione, should be considered to further elucidate the molecular basis of BT-11’s neuroprotective actions.

Secondly, we explored LANCL2 protein expression in the brain at the subcellular level. In the dorsal hippocampal tissue, as expected, LANCL2 was detected as a 51 kDa protein band in both the nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions. Interestingly, an ~ 51 kDa doublet was found in the cytoplasmic fraction, and an additional ~ 79 kDa band was visible in the nuclear fraction. These other bands could hint at post-translational modifications.

The cytoplasmic ~ 51 kDa doublet could correspond to LANCL2 myristoylation35. LANCL2 myristoylation adds a hydrophobic handle to the protein and induces its localization to cellular membranes, leading to it being identified as a non-transmembrane G protein-coupled receptor36,37. Additionally, when localized to a cellular membrane and activated by its endogenous ligand, ABA, LANCL2 stimulates adenylyl cyclase activity, thus increasing cAMP levels38,39. This was demonstrated in human red blood cells and granulocytes, but to our knowledge, has not been previously shown in the brain.

In the nuclear fraction, the ~ 79 kDa LANCL2 upper band could be the result of multiple phosphorylation and/or polyubiquitination translational modifications. Treatment of glioblastoma cells with ABA, the endogenous LANCL2 ligand, triggered its translocation to the nucleus40. Phosphoproteomic profiling of glioblastoma cells showed that ABA-induced LANCL2 phosphorylation at Tyr295 drives its activation and nuclear localization40. Using the PhosphoSitePlus tool (https://www.phosphosite.org) as in, 40. we identified potential LANCL2 phosphorylation, acetylation, and ubiquitination sites based on broad mass spectrometry studies of heart, brain tissue and multiple cell lines. It is possible that some of the other bands detected in our western blot experiments represent known or yet to be determined post-translational modifications. Future studies looking at LANCL2 post-translation modifications in conjunction with subcellular localizations in the context of AD, could lead to the clarification of the role of LANCL2 in the disease. Additionally, the observed increase in LANCL2 expression in TgF344-AD female rats as compared to WT in the cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions, suggests that the LANCL2 pathway may be differentially regulated by sex and disease status.

Thirdly, we demonstrated for the first time to our knowledge that LANCL2 is present in dorsal hippocampal oligodendrocytes, which form myelin sheaths and support axons. While oligodendrocyte loss is associated with AD, its mechanisms remain poorly understood41. The presence of LANCL2 in these cells suggests a potential brain-specific role. Notably, a recent study linked a glutathione-s-transferase pathway to oxidative stress regulation in premyelinating oligodendrocytes42. Single-cell RNA sequencing further shows elevated LANCL2 expression in CA1, CA3, and DG oligodendrocytes and precursors11,43. Since LANCL2 functions as a glutathione-s-transferase, it may contribute to oligodendrocyte resilience and function44. Our cell-type localization analysis of LANCL2 was limited to male WTNT and TGNT rats and was qualitative. While this established that LANCL2 is expressed in hippocampal oligodendrocytes, comprehensive analysis including all treatment groups, both sexes, and quantitative assessment would be necessary to determine whether BT-11 treatment or disease status affects LANCL2 expression in oligodendrocytes or other cell types. Similarly, functional studies are needed to establish whether LANCL2 activation in oligodendrocytes contributes to the therapeutic effects observed. These findings merit future studies such as elucidating at what stages of oligodendrocyte development LANCL2 is present, if there are changes in expression of LANCL2 on oligodendrocytes in ageing or AD conditions, and assess the role of activating LANCL2 in oxidative stress in the context of AD.

BT-11 was predicted to cross the blood-brain barrier suggesting that it can act locally, as it seems to have been detected in rat brain5. Thus, BT-11 may be working both at the CNS and systemically, as BT-11 treatment reduced inflammation in the gut2,27,45. It is well known that gut inflammation affects brain pathology50. The brain is not immune-privileged, and systemic inflammation influences AD pathology28,46. It is possible that after treatment with BT-11, the vagus nerve senses a reduced inflammatory state in the gut and transmits signals to the brain that ultimately lead to modulation of neuroinflammation. To address this potential mechanism, future studies should look at levels of inflammatory markers in the brain, gut, and blood after oral treatment with BT-11.

In conclusion, our studies highlight the therapeutic potential of targeting LANCL2 to improve cognitive behavior and reduce Aβ plaques and neuronal loss, especially in male AD patients. Our data suggest multiple mechanisms by which LANCL2 activation by BT-11 could ameliorate cognition and reduce AD pathology (Fig. 9):

-

(1)

BT-11 treatment enriches G-protein signaling pathways, pointing to the possibility of a previously identified mechanism involving cAMP in human blood cells and granulocytes, being present in the hippocampus. While the BT-11 treatment did not change LANCL2 expression, it likely changed its activity levels, leading to changes in downstream effectors. LANCL2 activation has been shown to enhance cAMP/PKA/pCREB signaling and IL-10 production pathways known to support neuronal differentiation, survival, and neurogenesis in the hippocampus4,47,48,49. While CREB activation has been a primary focus in understanding LANCL2-mediated signaling, alternative mechanisms have been suggested to contribute to its regulatory functions. LANCL2 could interact with kinases like MAPKs or Akt, influencing metabolism, immune regulation, and cell survival. It may also modulate transcription factors beyond CREB, such as NF-κB or Fbxo7, which regulate inflammation and oxidative stress40,49,50. Future studies should explore these pathways to uncover LANCL2’s broader functional and therapeutic potential.

-

(2)

In the hippocampus, LANCL2 is present in both the nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions with potential subcellular-specific post-translational modifications that could influence its role in different subcellular compartments.

-

(3)

Finding that LANCL2 is present in oligodendrocytes of the dorsal hippocampus of WT and TgF344-AD male rats suggests it may play a role in supporting oligodendrocyte function in both normal and disease contexts, though this requires further investigation. As LANCL2 is a glutathione-s-transferase, its activation could reduce oxidative stress in oligodendrocytes.

LANCL2 activation by BT-11 couples anti-inflammatory and detoxification mechanisms with relevance to Alzheimer’s disease (created with BioRender.com). (1) Inflammation Reduction: BT-11 or ABA activation of LANCL2 stimulates AC → cAMP → PKA → pCREB signaling leading to reduced inflammation (↑IL-10, ↓TNFα) as has been shown in human granulocytes, rat β-cells, and mouse T cells. 4,27,74. LANCL2 may also regulate alternative pathways as shown in computational model of macrophage differentiation based in response to H. pylori, including MAPKs, Akt, NF-κB, and Fbxo7, which are engaged in metabolic, immune and oxidative-stress processes, as shown in mouse macrophages and T cells49. (2) Detoxification: LANCL2’s glutathione S-transferase activity facilitates detoxification via glutathione conjugation in HEK293 and MEF cells 44, and potentially MRP1-mediated removal of toxic cargo as shown in human cancer cell lines75. LANCL2 localization to membrane, cytoplasm or nucleus, as shown in cancer cell lines40, likely determines its anti-inflammatory and detoxification effects. Because chronic neuroinflammation and redox stress are key drivers of AD pathology, these LANCL2-modulated mechanisms provide a rationale for testing BT-11 in AD. AC, adenylyl cyclase; Akt, protein kinase B; Fbxo7, F-box only protein 7; HEK, human embryonic kidney; IL-10, interleukin 10; LANCL2, lanthionine synthetase C-like 2; MAPK, Mitogen-activated protein kinase; MEF, mouse embryonic fibroblasts; MRP1, multidrug resistance protein 1; NF-κB, Nuclear factor-kappa B; pCREB, phosphorylated cAMP response element-binding protein; PKA, protein kinase A; TNFα, tumor necrosis factor α.

Taken together, our findings highlight the translational promise of LANCL2 as a multifaceted therapeutic target for AD. While mechanistic dissection represents important future work, our study provides proof-of-concept that targeting LANCL2 produces therapeutic benefits, establishing rationale for further mechanistic follow-up and clinical translation. By engaging diverse pathological pathways, activation of LANCL2—particularly via the novel small molecule BT-11—emerges as a compelling strategy with the potential to significantly alter the course of AD.

Materials and methods

TgF344-AD rat model

TgF344-AD transgenic rats express the human APP Swedish (APPswe) and Δ exon 9 presenelin-1 (PS1ΔE9) mutations driven by the prion promoter, at 2.6- and 6.2-fold higher levels than the respective endogenous rat proteins15. These rats exhibit AD-like pathology and navigational deficits similar to those found in pre-clinical AD, and in an age-dependent progressive manner51. TgF344-AD rats were purchased from the Rat Resource and Research Center (Columbia, MO). TgF344-AD and WT rats of both sexes were housed in pairs and maintained on a 12-h light/dark cycle with food and water available ad libitum. All animal procedures were performed in compliance with the relevant guidelines and regulations of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at Hunter College. All experimental protocols were approved by the IACUC and were conducted in accordance with the ARRIVE Essential 10 guidelines and the AVMA Guidelines for the Euthanasia of Animals52.

Experimental design

Our aim was to figure out if BT-11 could mitigate, prevent, or delay AD symptoms. BT-11 treatment started at 5 months of age to target an early pathological/behavioral window in TgF344-AD rats: spatial/cognitive changes begin to emerge across mid-adulthood with variability by task and sex51,53,54. Treatment was continued for 6 months until 11 months of age, when the TgF344-AD rats show moderate AD-pathology (Fig. 1a, experimental design). A total of 124 rats across multiple cohorts were included in these studies. Males: WTNT n = 14, WTTR n = 13, TGNT n = 17, TGTR n = 13, and Females: WTNT n = 28, WTTR n = 12, TGNT n = 16, TGTR n = 11.

Rats were treated with 8 mg/kg bw/day of BT-11 (Supplemental Figs. 14 and 15), based on efficacy studies at 8 mg/kg bw/day in multiple mouse models of IBD, and safety at higher exposures in Sprague Dawley rats4,55,56. BT-11 was delivered orally through ad libitum 5001 Purina rodent chow from Research Diets, Inc. Efficacy assessment included treatment with 2 types of chow: BT-11 and BT-11-free (control) chow × 2 genotypes (WT and TgF344-AD) × 2 sexes (males and females).

At 11 months of age, all rats were evaluated for hippocampal-dependent spatial memory. Following cognitive behavior assessment, rats were anesthetized intraperitoneally with ketamine (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg), and euthanasia was performed via transcardial perfusion with cold RNAse-free 1X PBS57. Brains were then isolated, bisected, and prepared for IHC, RNA sequencing (RNA-seq), and Western blot analyses as described57.

Spatial memory assessment

All rats were tested at 11 months of age with the active place avoidance test (aPAT), as previously described13,58. The aPAT is a spatial memory task that assesses hippocampal-dependent 24-h retention memory and learning relevant to AD13. The hippocampus plays a role in spatial memory, and it is one of the first brain regions affected by AD. The aPAT is active, meaning that the rodent must participate. The arena has a rotating platform that operates at one revolution per minute (rpm), with visual cues at each wall of the room. The arena is divided into four quadrants, one of which is designated as a shock zone. If a rat enters the shock zone and remains there for at least 1.5 s, it will receive a 0.2 A shock. A shock is administered every 1.5 s until the rat leaves the shock zone. An overhead camera above the arena tracks the location of the rat throughout the task.

Rats are given a 30 min resting period separated from their cage-mate in a paper bedding cage before habituation. Next, there is a 10 min habituation trial in which rats explore the arena while the shock zone is off. After this trial, the shock zone is turned on and the training consists of six 10 min trials. There is a 10-min rest time between each of the six 10 min trials. 24 h later, rats are given a 10 min test trial with the shock turned off.

Performance in the behavior test was analyzed based on the following measures: percent time spent in shock zone, latency to first entrance of shock zone, number of entrances, number of shocks administered, and maximum time spent avoiding the shock zone. A well-performing rat, indicative of increased learning and spatial memory, will spend less time in the shock zone over the course of 6 trials. As in our previous studies, rats generally learned during the first 3 trials (early acquisition, trials 1–3) and then reached an asymptote at which their performance levels off during trials 4–6 (asymptotic performance, trials 4–6)10,18,58.

Immunohistochemistry

Tissue collection, preparation, and left hippocampal immunohistochemistry (IHC) were performed in 11-month-old rats, as previously described58. Hippocampal sections chosen for IHC analysis corresponded to bregma—3.36 through—4.44 in the rat brain atlas bregma—3.36 through—4.4459. Sections were viewed under a wide-field fluorescence microscope (Zeiss AxioImager M2) using a Zeiss AxioCam MRm Rev. 3 camera connected to a motorized stage. The software AxioVision 4 module MosaiX was used to capture whole hippocampal region mosaics (5x, 10 × and 20 × magnifications). Each channel was analyzed to an antibody specific threshold. DSRed set was used for Aβ imaging, GFP spectrum filter set was used for Iba1 imaging, DAPI set was used for DAPI imaging. Exposure time for each channel was kept consistent among sections. For each captured image, ZVI files were loaded onto FIJI (Fiji Is Just ImageJ, NIH, Bethesda, MD) and converted to .tif files for future use in optical density and co-localization analyses.

Hippocampal subregions (CA1, CA3, DG and subiculum) were isolated, cropped, and saved as .tif files for use in pixel‐intensity area analyses as described in60. Three tissue sections per treatment/genotype group were used for quantification. Nonspecific background density was corrected using ImageJ rolling-ball method61. Primary and secondary antibodies are listed in Supplemental Table 8. We performed western blot analysis to confirm the specificity of the LANCL2 antibody (Supplemental Fig. 16).

Images were analyzed to extract the positive signal from each image with custom batch‐processing macroscripts created for each channel/marker. Pixel‐intensity statistics were calculated from the images at 16‐bit intensity bins62. Positive signal areas were measured, and masks were created and merged when co-localization analyses were required. Co-localization measurements were achieved by measuring the overlap of two merged masks from an analyzed image crop. Aβ plaque load was quantified as % area, representing the percentage of the hippocampal area with positive 4G8 immunosignal above a fixed threshold. This method provides a measure of total plaque burden that is widely used in AD research63.

Ramified, reactive, and amoeboid microglia were analyzed by circularity based on the ImageJ form factor as previously described57,58. Microglia exhibit a remarkable variety of morphologies that can be associated with their functions57. Using binary images of individual microglia silhouettes, activated microglia were distributed into three different groups according to their form factor (FF) value, which was defined as 4π X area/perimeter2: ramified, FF: 0 to 0.499; reactive, FF: > 0.5 to 0.699, and amoeboid, FF > 0.70 to 1. Images stained with the Iba1 antibody were used for morphological analyses, to characterize microglia into the three distinct shape classes. Particles within 50–300 μm2 were chosen for FF analyses. Quantities of each microglia class were collected and analyzed independently and in ratios of amoeboid normalized to ramified and then compared across treatment/genotype.

RNA sequencing analyses

Right hippocampi from the same rats used for IHC, were analyzed for gene expression by RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) at the UCLA Technology Center for Genomics and Bioinformatics (Los Angeles, CA). Samples from five male TGNT and five TGTR were compared, and the same was done for female rats. Libraries for RNAseq were prepared with the KAPA mRNA-Seq Hyper Prep Kit. cDNA was prepared and amplified, and sequencing was performed on Illumina NovaSeq6000 for a PE 2 × 50 run. Data quality was checked using Illumina SAV and demultiplexing was performed with Illumina Bcl2fast1 v2.19.1.403 software. Reads were mapped by STAR 2.7.9a and read counts per gene were quantified using the rat genome rn6. Read counts were normalized by median ratio. Differentially expressed genes between TGNT and TGTR for each sex were determined using the DESeq2 program on R64,65. Normalized read counts were analyzed for fold-change, p values, and p adjusted values (based on false discovery rate) for each gene. Gene set enrichment analysis including genes with p value < 0.05 and fold change > 1.5 or < -1.5 was used to generate enriched pathways. The protein–protein interaction network for neurotrophin receptor binding was retrieved from the STRING database66. The images in Fig. 6 were created using: a67, b and c68, d66, e and f69,70,71.

Subcellular fractionation

Approximately 50 mg of frozen right hippocampal tissue were added to 4 μl of homogenizing buffer (0.5% 10X protein inhibitor cocktail in TEE buffer) per mg of tissue. The tissue was homogenized using 20 pumps on the Cole Palmer homogenizer at 40 rpm at room temperature. Approximately half of the total homogenate was aliquoted into an Eppendorf tube, labeled total lysate, and stored at − 80 °C. The other half of the homogenate was placed in an Eppendorf tube labeled ‘nuclear’ and centrifuged for 5 min at 3,000 g at 4 °C. The supernatant was transferred to an ultracentrifuge tube and spun at 100,000 g for 30 min at 4 °C in the ultracentrifuge. While the ultracentrifuge was running, 100 µl of homogenizing buffer was added to the nuclear Eppendorf tube and it centrifuged again at 3,000 g for 10 min to remove debris. The supernatant was discarded, and the pellet resuspended in 100 µl of homogenizing buffer, labeled nuclear fraction and stored at − 80 °C. The supernatant from the ultracentrifuge tubes were transferred to an Eppendorf tube, labeled cytoplasmic fraction, and stored at -80 °C.

This procedure was performed for three female and three male rats of the following four groups: WTNT, WTTR, TGNT, and TGTR. This procedure yielded three cellular fractions, total lysate, nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions all used for western blot analyses.

Western blotting

Each Western blot lane represents tissue from a distinct animal (n = 3 per group, 8 groups: WTNT, WTTR, TGNT, and TGTR for both males and females), reflecting biological replication. This number aligns with prior in vivo studies72,73. and reflects tissue constraints inherent to AD rat models, including prioritizing tissue for RNAseq, immunohistochemistry, and western blotting. Protein concentrations for total, nuclear, and cytoplasmic fractions were determined with the BCA assay. 30 μg of sample were loaded on a Novex Tris–Glycine 4–12% gel, ran for approximately one hour and 50 min, and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes with the iBlot® dry blotting system (Life Technologies) for 6.5 min. Membranes were washed with TBS/Triton and blocked with 5% BSA. Membranes were then probed overnight at 4 °C with primary antibody solutions in 1% BSA, followed by secondary antibodies for one hour, prior to developing with an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) substrate (SuperSignalTM West Pico PLUS, ThermoFisher #34,580), and detected by autoradiography (film from Midwest Scientific, cat# XC6A2). Primary and secondary antibodies are listed in Supplemental Table 8. ImageJ software was used for semi quantification of protein bands by densitometry. Loading controls used were GAPDH for total and cytoplasmic fractions and lamin B1 for nuclear fractions.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with GraphPad Prism versions 9 and 10 for macOS, GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA, (www.graphpad.com). All p values and relevant statistics are shown on graphs and supplemental tables. Data are the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) with n being the number of rats. Three-way ANOVAs were used to determine significant effects across independent variables for behavior prior to two-way repeated measures ANOVAs across all four groups for both males and female separately (WTNT, TGNT, WTTR, TGTR), as well as for WTNT vs. TGNT, TGNT vs. TGTR, WTNT vs. WTTR, and WTTR vs. TGTR, followed by Tukey or Sidak post-hoc tests to assess differences across individual trials (Supplemental Tables 2a and b).

For IHC analyses unpaired two-tailed t-tests were used to assess Aβ % area between TGNT and TGTR rats (Supplemental Table 3). Additionally, two-way ANOVAs were used to assess tau count/nm2 for WTNT, TGNT, WTTR, and TGTR rats for the dorsal hippocampus (Supplemental Table 6a). Unpaired t-tests were used to assess tau count/nm2 between TGNT and TGTR rats across multiple subregions (Supplemental Tables 6b-h). For all microglia analyses two-way ANOVAs with Tukey multiple comparisons tests were performed (Supplemental Tables 4a-t). For NeuN IHC analyses two-way ANOVAs with Tukey multiple comparisons were performed for WTNT, TGNT, WTTR, and TGTR rats (Supplemental Tables 5a-g).

For western blotting two-way ANOVAs followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison tests were used to compare normalized densities of proteins across four groups for both males and females (WTNT, WTTR, TGNT, TGTR), (Supplemental Tables 7a-c).

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the NIH GEO repository, ACCESSION NUMBERS: GSE280023 and GSE280024.

References

Heneka, M. T. et al. Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet. Neurol. 14, 388–405. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(15)70016-5 (2015).

Landos Biopharma Announces Positive Results from a Phase 2 Trial of Oral BT-11 for Patients with Ulcerative Colitis (2021).

Leber, A., Hontecillas, R., Juni, N. T. & Bassaganya-Riera, J. S1077 efficacy and safety of omilancor in a phase 2 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of patients with ulcerative colitis. Off. J. Am. Coll. Gastroenterol. ACG 118, S821 (2023).

Carbo, A. et al. An N,N-bis(benzimidazolylpicolinoyl)piperazine (BT-11): A novel lanthionine synthetase C-Like 2-based therapeutic for inflammatory bowel disease. J. Med. Chem. 59, 10113–10126. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b00412 (2016).

Park, C. H. et al. Novel cognitive improving and neuroprotective activities of Polygala tenuifolia Willdenow extract, BT-11. J. Neurosci. Res. 70, 484–492. https://doi.org/10.1002/jnr.10429 (2002).

Shin, K. Y. et al. BT-11 is effective for enhancing cognitive functions in the elderly humans. Neurosci. Lett. 465, 157–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2009.08.033 (2009).

Do Carmo, S. & Cuello, A. C. Modeling Alzheimer’s disease in transgenic rats. Mol. Neurodegen. 8, 37–37. https://doi.org/10.1186/1750-1326-8-37 (2013).

Cohen, R. M. et al. A transgenic Alzheimer rat with plaques, tau pathology, behavioral impairment, oligomeric abeta, and frank neuronal loss. J. Neurosci 33, 6245–6256 (2013).

Saré, R. M. et al. Behavioral phenotype in the TgF344-AD rat model of Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Neurosci. 14, 601–601. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2020.00601 (2020).

Wallace, C. H. et al. Potential Alzheimer’s early biomarkers in a transgenic rat model and benefits of diazoxide/dibenzoylmethane co-treatment on spatial memory and AD-pathology. Sci. Rep. 14, 3730–3730. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-54156-z (2024).

Uhlen, M. et al. Towards a knowledge-based Human Protein Atlas. Nat Biotechnol 28, 1248–1250. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt1210-1248 (2010).

Tsigelny, I. F., Kouznetsova, V. L., Lian, N. & Kesari, S. Molecular mechanisms of OLIG2 transcription factor in brain cancer. Oncotarget 7, 53074–53101. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.10628 (2016).

Lesburguères, E., Sparks, F. T., O’Reilly, K. C. & Fenton, A. A. Active place avoidance is no more stressful than unreinforced exploration of a familiar environment. Hippocampus 26, 1481–1485. https://doi.org/10.1002/hipo.22666 (2016).

Eichenbaum, H. The role of the hippocampus in navigation is memory. J. Neurophysiol. 117, 1785–1796. https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.00005.2017 (2017).

Cohen, R. M. et al. A transgenic Alzheimer rat with plaques, tau pathology, behavioral impairment, oligomeric abeta, and frank neuronal loss. J. Neurosci.: Off. J. Soc. Neurosci. 33, 6245–6256. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3672-12.2013 (2013).

Chaudry, O. et al. Females exhibit higher GluA2 levels and outperform males in active place avoidance despite increased amyloid plaques in TgF344-Alzheimer’s rats. Sci. Rep. 12, 19129. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-23801-w (2022).

Bernaud, V. E. et al. Task-dependent learning and memory deficits in the TgF344-AD rat model of Alzheimer’s disease: Three key timepoints through middle-age in females. Sci. Rep. 12, 14596–14596. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-18415-1 (2022).

Chaudry, O. et al. Females exhibit higher GluA2 levels and outperform males in active place avoidance despite increased amyloid plaques in TgF344-Alzheimer’s rats. Sci. Rep. 12, 19129. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-23801-w (2022).

de Vries, L. E., Huitinga, I., Kessels, H. W., Swaab, D. F. & Verhaagen, J. The concept of resilience to Alzheimer’s Disease: Current definitions and cellular and molecular mechanisms. Mol. Neurodegener. 19, 33–33. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13024-024-00719-7 (2024).

Koebele, S. V. & Bimonte-Nelson, H. A. Modeling menopause: The utility of rodents in translational behavioral endocrinology research. Maturitas 87, 5–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2016.01.015 (2016).

Zárate, S., Stevnsner, T. & Gredilla, R. Role of estrogen and other sex hormones in brain aging. Neuroprotection and DNA repair. Front. Aging Neurosci. 9, 430–430. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2017.00430 (2017).

Campesi, I. & Franconi, F. Sex-gender differences in pharmacokinetics. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 21, 491–493. https://doi.org/10.1080/17425255.2025.2479115 (2025).

Paolicelli, R. C. et al. Microglia states and nomenclature: A field at its crossroads. Neuron 110, 3458–3483. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2022.10.020 (2022).

Leng, F. & Edison, P. Neuroinflammation and microglial activation in Alzheimer disease: where do we go from here?. Nat. Rev. Neurol. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41582-020-00435-y (2020).

Olah, M. et al. Single cell RNA sequencing of human microglia uncovers a subset associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Commun. 11, 6129–6129. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-19737-2 (2020).

Bennett, M. L. et al. New tools for studying microglia in the mouse and human CNS. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, E1738-1746. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1525528113 (2016).

Leber, A., Hontecillas, R., Zoccoli-Rodriguez, V. & Bassaganya-Riera, J. Activation of LANCL2 by BT-11 ameliorates IBD by supporting regulatory T cell stability through immunometabolic mechanisms. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 24, 1978–1991. https://doi.org/10.1093/ibd/izy167 (2018).

Walker, K. A., Ficek, B. N. & Westbrook, R. Vol. 10 3340–3342 (ACS Publications, 2019).

Peferoen, L., Kipp, M., van der Valk, P., van Noort, J. M. & Amor, S. Oligodendrocyte-microglia cross-talk in the central nervous system. Immunology 141, 302–313. https://doi.org/10.1111/imm.12163 (2014).

Bac, B. et al. The TgF344-AD rat: behavioral and proteomic changes associated with aging and protein expression in a transgenic rat model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 123, 98–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2022.12.015 (2023).

Gao, L., Zhang, Y., Sterling, K. & Song, W. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor in Alzheimer’s disease and its pharmaceutical potential. Transl. Neurodegen. 11, 4. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40035-022-00279-0 (2022).

Ding, X. et al. Recombinant neurotrophin-3 with the ability to penetrate the blood-brain barrier: A new strategy against Alzheimer’s disease. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 293, 139359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.139359 (2025).

Jia, L., Piña-Crespo, J. & Li, Y. Restoring Wnt/β-catenin signaling is a promising therapeutic strategy for Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Brain 12, 104. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13041-019-0525-5 (2019).

Marzo, A. et al. Reversal of Synapse Degeneration by Restoring Wnt Signaling in the Adult Hippocampus. Curr Biol 26, 2551–2561. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2016.07.024 (2016).

Hayashi, N. & Titani, K. N-myristoylated proteins, key components in intracellular signal transduction systems enabling rapid and flexible cell responses. Proc. Jpn. Acad. Ser. B, Phys. Biol. Sci. 86, 494–508. https://doi.org/10.2183/pjab.86.494 (2010).

Landlinger, C., Salzer, U. & Prohaska, R. Myristoylation of human LanC-like protein 2 (LANCL2) is essential for the interaction with the plasma membrane and the increase in cellular sensitivity to adriamycin. Biochem. Biophys. Acta. 1758, 1759–1767. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.07.018 (2006).

Fresia, C. et al. G-protein coupling and nuclear translocation of the human abscisic acid receptor LANCL2. Sci. Rep. 6, 26658–26658. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep26658 (2016).

Bruzzone, S. et al. Abscisic acid: A new mammalian hormone regulating glucose homeostasis. Messenger 1, 141–149. https://doi.org/10.1166/msr.2012.1012 (2012).

Vigliarolo, T. et al. Abscisic acid transport in human erythrocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 13042–13052. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M114.629501 (2015).

Zhao, H. F. et al. Nuclear transport of phosphorylated LanCL2 promotes invadopodia formation and tumor progression of glioblastoma by activating STAT3/Cortactin signaling. J. Adv. Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jare.2024.03.007 (2024).

DeFlitch, L., Gonzalez-Fernandez, E., Crawley, I. & Kang, S. H. Age and Alzheimer’s Disease-Related Oligodendrocyte Changes in Hippocampal Subregions. Front Cell Neurosci 16, 847097. https://doi.org/10.3389/fncel.2022.847097 (2022).

Hughes, E. G. & Stockton, M. E. Premyelinating Oligodendrocytes: Mechanisms Underlying Cell Survival and Integration. Frontiers in cell and developmental biology 9, 714169–714169. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2021.714169 (2021).

Karlsson, M. et al. A single–cell type transcriptomics map of human tissues. Sci Adv 7, eabh2169. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abh2169 (2021).

Lai, K.-Y. et al. LanCLs add glutathione to dehydroamino acids generated at phosphorylated sites in the proteome. Cell 184, 2680-2695.e2626. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2021.04.001 (2021).

Leber, A., Hontecillas, R., Zoccoli-Rodriguez, V., Chauhan, J. & Bassaganya-Riera, J. Oral treatment with BT-11 ameliorates inflammatory bowel disease by enhancing regulatory T cell responses in the gut. J. Immunol. ji1801446-ji1801446 (2019). https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.1801446.

Xie, J., Van Hoecke, L. & Vandenbroucke, R. E. The impact of systemic inflammation on alzheimer’s disease pathology. Front. Immunol. 12, 796867 (2022).

Nakagawa, S. et al. Regulation of neurogenesis in adult mouse hippocampus by cAMP and the cAMP response element-binding protein. J Neurosci 22, 3673–3682. https://doi.org/10.1523/jneurosci.22-09-03673.2002 (2002).

Pereira, L. et al. IL-10 regulates adult neurogenesis by modulating ERK and STAT3 activity. Front. Cell Neurosci. 9, 57. https://doi.org/10.3389/fncel.2015.00057 (2015).

Leber, A. et al. Modeling the Role of Lanthionine Synthetase C-Like 2 (LANCL2) in the Modulation of Immune Responses to Helicobacter pylori Infection. PLoS ONE 11, e0167440–e0167440. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0167440 (2016).

Lou, Y. et al. Akt kinase LANCL2 functions as a key driver in EGFR-mutant lung adenocarcinoma tumorigenesis. Cell Death Dis. 12, 170. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-021-03439-8 (2021).

Berkowitz, L. E., Harvey, R. E., Drake, E., Thompson, S. M. & Clark, B. J. Progressive impairment of directional and spatially precise trajectories by TgF344-Alzheimer’s disease rats in the Morris Water Task. Sci. Rep. 8, 16153–16153. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-34368-w (2018).

Percie du Sert, N. et al. The ARRIVE guidelines 2.0: Updated guidelines for reporting animal research. PLoS Biol 18, e3000410. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3000410 (2020).

Proskauer Pena, S. L. et al. Early Spatial Memory Impairment in a Double Transgenic Model of Alzheimer’s Disease TgF-344 AD. Brain Sci 11 (2021). https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci11101300

Nataraj, A., Blahna, K. & Ježek, K. Insights from TgF344-AD, a double transgenic rat model in alzheimer’s disease research. Physiol. Res. 74, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.33549/physiolres.935464 (2025).

Leber, A. et al. Nonclinical toxicology and toxicokinetic profile of an oral lanthionine synthetase C-like 2 (LANCL2) agonist, BT-11. Int. J. Toxicol. 38, 96–109. https://doi.org/10.1177/1091581819827509 (2019).

Leber, A. et al. The safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics profile of BT-11, an oral, gut-restricted lanthionine synthetase C-like 2 agonist investigational new drug for inflammatory bowel disease: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase I clinical trial. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 26, 643–652. https://doi.org/10.1093/ibd/izz094 (2020).

Oliveros, G. et al. Repurposing ibudilast to mitigate Alzheimer’s disease by targeting inflammation. Brain 146, 898–911. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awac136 (2023).

Wallace, C. H. et al. Timapiprant, a prostaglandin D2 receptor antagonist, ameliorates pathology in a rat Alzheimer’s model. Life Sci Alliance 5 (2022). https://doi.org/10.26508/lsa.202201555.

Nie, B. et al. A rat brain MRI template with digital stereotaxic atlas of fine anatomical delineations in paxinos space and its automated application in voxel-wise analysis. Hum. Brain Mapp. 34, 1306–1318. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.21511 (2013).

Avila, J. A. et al. PACAP27 mitigates an age-dependent hippocampal vulnerability to PGJ2-induced spatial learning deficits and neuroinflammation in mice. Brain and behavior 10, e01465–e01465. https://doi.org/10.1002/brb3.1465 (2020).

Braune, S., Alagoz, G., Seifert, B., Lendlein, A. & Jung, F. Automated image-based analysis of adherent thrombocytes on polymer surfaces. Clin. Hemorheol. Microcirc. 52, 349–355 (2012).

Hartig, S. M. Basic Image Analysis and Manipulation in ImageJ. Curr. Protocols Mol. Biol. 102, 14.15.11–14.15.12 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1002/0471142727.mb1415s102

Christensen, A. & Pike, C. J. Staining and quantification of β-amyloid pathology in transgenic mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease. Methods Mol. Biol. 2144, 211–221. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-0716-0592-9_19 (2020).

Love, M. I., Huber, W. & Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15, 550. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8 (2014).

Team, R. C. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, https://www.R-project.org/ (2023).

Szklarczyk, D. et al. The STRING database in 2023: protein-protein association networks and functional enrichment analyses for any sequenced genome of interest. Nucleic Acids Res 51, D638-d646. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkac1000 (2023).

Oliveros, J. C. Venny. An interactive tool for comparing lists with Venn’s diagrams, <https://bioinfogp.cnb.csic.es/tools/venny/index.html> (2007–2025).

Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis, <https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org> (2016).

Yu, G. enrichplot: Visualization of Functional Enrichment Result, <https://doi.org/10.18129/B9.bioc.enrichplot; https://bioconductor.org/packages/enrichplot> (2023).

Wu, T. et al. clusterProfiler 4.0: A universal enrichment tool for interpreting omics data. Innovation (Camb) 2, 100141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xinn.2021.100141 (2021).

Yu, G., Wang, L. G., Yan, G. R. & He, Q. Y. DOSE: an R/Bioconductor package for disease ontology semantic and enrichment analysis. Bioinformatics 31, 608–609. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btu684 (2015).

Heneka, M. T. et al. NLRP3 is activated in Alzheimer’s disease and contributes to pathology in APP/PS1 mice. Nature 493, 674–678. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11729 (2013).

Sriram, D. et al. Expression of a novel brain specific isoform of C3G is regulated during development. Sci. Rep. 10, 18838. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-75813-z (2020).

Sturla, L. et al. LANCL2 is necessary for abscisic acid binding and signaling in human granulocytes and in rat insulinoma cells. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 28045–28057. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M109.035329 (2009).

de Bittencourt Júnior, P. I., Curi, R. & Williams, J. F. Glutathione metabolism and glutathione S-conjugate export ATPase (MRP1/GS-X pump) activity in cancer. I. Differential expression in human cancer cell lines. Biochem. Mol. Biol. Int. 45, 1227–1241. https://doi.org/10.1080/15216549800203452 (1998).

Funding

The funding was provided by NIH NIA (Grant No. R01AG057555), NIH Weill Cornell CTSC (Grant No. TL1-TR0002386), and the City University of NY (CNC program).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.B., P.S., P.R., and M.F.P., conceived the project and designed the experiments. L.X. performed the computational analysis supporting BT-11 treatment for AD. E.B. performed all experiments and analyzed the data. E.B. and M.F.P wrote the manuscript. P.S. and P.R edited the manuscript. All authors approved the manuscript for submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions