Abstract

Carrier-mediated drug delivery is one of the potential approaches employed to increase drug solubility and bioavailability. Atorvastatin (ATR), a HMG CoA reductase inhibitor, is a first-line medication prescribed for the treatment of hyperlipidemia and related cardiovascular diseases. The efficacy of ATR is highly limited due to its poor solubility and low oral bioavailability. In the present study, an injectable system of ATR-loaded polymeric nanoparticles was synthesized through the spray drying technique using chitosan polymer extracted in-house from a novel source of Portunus Sanguinolentus species shells. The effect of spray dryer nozzle diameter and polymer concentration on particle size, morphology, in vitro drug release, and ex vivo permeation was studied. The synthesized ATR-loaded chitosan particles were in the size range of 248.2 ± 17.58 nm to 329 ± 36.68 nm with homogeneous distribution. The average drug loading of all formulations was above 80%. The nozzle of 0.7 mm diameter produced smaller-sized particles with higher drug loading compared to the 1 mm diameter nozzle. Morphological analysis of the synthesized nanoparticles was performed using SEM, which revealed that particle size was increased linearly with increasing concentration of chitosan, with more flower-like structure deposition of polymer on the surface. The in vitro drug release and solubility study of the formulations on different bio-relevant media confirmed that the solubility of the drug was increased on all three different media as the concentration of chitosan increased. Also, the presence of chitosan improved the permeability of the drug through the membrane’s adhesive property. Characterization of selected formulation with analytical techniques like FT-IR, XRD, TG-DSC confirmed that the drug was functionally active in the polymeric systems without significant alterations. Therefore, the synthesized formulation was proven to be effective in improving in vitro dissolution without significant loss, which could improve the in vivo bioavailability of Atorvastatin by enhancing solubility, absorption, and permeation in the physiological system.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Atherosclerosis has remained as the major cause of cardiovascular diseases (CVD) for many decades. CVD comprises the complex disorders of the heart and blood vessels, with a global mortality rate of 32% as of 20191. The prime risk factors for CVD development involve higher alcohol consumption, fatty diet, obesity, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, reduced physical activity, and sleep deprivation. The reduced blood flow to the cardiomyocytes due to aortic stenosis is the mainly reported cause for the worldwide death (83%) associated with CVD1,2. The development of aortic stenosis is a multi-step process, wherein fat accumulation is the initial pivotal phase, followed by development of atherosclerosis until the destabilization of plaque leading to distal microvascular thrombosis formation3. Lipoproteins play a crucial role in regulation of lipids metabolism and in transporting fatty substances through the bloodstream. The Low-Density Lipoproteins (LDL) are derivatives of Very Low-Density Lipoproteins (VLDL) and Intermediate Density Lipoproteins (IDL)4, which are generally considered as bad cholesterol. Elevated LDL level is one of the prime attributable factors for the global cause of CVD-associated deaths (3.8 million in 2021)2. When this freely circulating LDL are attached to the atrial proteoglycans, the immune cells (monocytes) infiltrate into the lesion to engulf the fatty molecules by forming the fatty streak, which further develops into fibrous plaque5,6. Hence, to effectively treat atherosclerosis, the drug moiety must be able to regulate both the fat-driven inflammation and the elevated plasma LDL cholesterol at the same time7.

Statins are HMG-CoA reductase (HMGCR) inhibitors, commonly prescribed medications for treating CVD globally. It is a structural analogue of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl Coenzyme A (HMG-CoA), with high affinity towards the active site. The binding of statins reduces the free enzyme available for converting the HMG-CoA to mevalonate in the cholesterol biosynthesis pathway, which lowers the overall cholesterol production. The reduced cholesterol level in hepatocytes induces the expression of LDL receptors on the surface through translocating the sterol regulatory element binding proteins (SREBPs) from the endoplasmic reticulum to the nucleus. Excessive expression of LDL receptors on the hepatocyte membrane scavenges the circulating LDL along with its cargo, which reduces the total cholesterol and triglyceride contents in the blood8,9. In addition to this, Statins are known for their pleiotropic non-lipidomic effects, such as anti-inflammatory, anti-thrombogenic, plaque stability, adipokine regulation, restoring endothelial function, increasing HDL secretion, and reducing smooth muscle cell migration (SMC). The pleiotropic effects are due to the reduction of isoprenoids such as geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate (GGPP) and farnesyl pyrophosphate (FPP) in the mevalonate pathway, which are essential for the prenylation of proteins for their protein-protein and protein-membrane interactions10.

Atorvastatin (ATR) is a synthetic lipophilic second-generation Statin molecule, which falls under BCS Class II with low solubility and higher membrane permeability. According to the Medical Expenditure Panel survey (MEPS) of the United States (US), ATR is recognized as one of the most prescribed drugs among the other statins, and its usage linearly increased between 2008 and 201911,12. Among the Statin family, ATR shows a substantial reduction in LDL and triglyceride levels with IC50 values of 1.16 nM for HMG-CoA9,13. The presence of an additional hydrogen bond between the drug-enzyme complex could contribute to its enhanced lipidomic and non-lipidomic effects14,15,16. Although it is well known for lowering plasma cholesterol, its overall clinical success rate is limited due to its poor oral bioavailability (12%). Its limited aqueous solubility (0.1 mg/ml), crystalline nature, higher faecal excretion (70%), and extreme first pass metabolism by Cytochrome P40 enzyme (CYP3A4) result in reduced availability, thereby leading to high daily dose recommendations17,18. However, high-intense doses of Statins are associated with several adverse effects like rhabdomyolysis, myalgia, myositis, especially in old people with polypharmacy19,20.

Several formulation approaches, such as micronization, phase transition to amorphous21 solid dispersion22,23, and encapsulation in natural or synthetic polymeric24,25, have been reported over the last two decades to address conventional challenges by modulating the physicochemical properties of ATR. Biodegradable polymeric carrier-based delivery of active pharmaceutical ingredients (API) has garnered significant interest due to its benefits, including pre-programmed drug release, improved drug stability, reduced toxicity, and high biocompatibility26. Nevertheless, there is a need for the development of a biodegradable, hydrophilic carrier-based injectable system of Statins to achieve an immediate effect of the poorly soluble and low oral bioavailable drug for treating acute cardiovascular disease conditions27,28. Chitosan is a widely used natural cationic polysaccharide biopolymer for delivering drugs, due to its attractive properties, including biocompatibility, biodegradability, muco-adhesiveness, enhanced epithelial permeability, anti-inflammatory effects, and notably, anti-cholesterolemic properties29,30. It is commonly derived through the deacetylation of chitin, a major component in the exoskeleton of crustaceans (shrimp, lobsters, crabs)31,32, containing repeating units of N-acetyl-D-glucosamine and D-glucosamine with variable degrees of deacetylation (40–98%). Chitosan-based injectable formulations have been reported for enhancing solubility, dissolution, and site-specific action, for both acute and chronic treatments of several drugs33,34. In this present study, we attempt to synthesize Atorvastatin-loaded Chitosan particles through the spray drying technique, which is a single-step, scalable, and highly reproducible approach35. Previously, researchers have studied extensively the impact of chitosan on Atorvastatin solubility enhancement using the commercially available chitosan36,37,38,39. The majority of work focused on the conventional tripolyphosphate (TPP) ionic gelation method to synthesize ATR-loaded chitosan-based micro and nanoparticles, except for the work carried out by Mohammad Karim Haidar et al.39 where the authors utilized the spray drying technique. Ionic gelation with TPP as a cross-linking agent is a widely explored technique to synthesize drug-loaded chitosan nanoparticles. However, the characteristics of the particle are highly dependent on the concentration of crosslinking agent, homogenizing speed, pH of the solution, TPP addition rate, and availability of free amino groups, which all hinder the reproducibility, scalability, and potential market transition from the bench40,41. Besides, purification or drying of drug-loaded chitosan nanoparticles at the end of the conventional TPP method is challenging, and it often requires a cryoprotectant since the structural integrity of chitosan is sensitive to parameters associated with commonly employed drying techniques like the freeze-drying process42,43. In the present work, we have used a novel chitosan extracted and characterized previously in our laboratory from the shells of the spot crab Portunus Sanguinolentus (collected from the shores of the Bay of Bengal) with a degree of deacetylation of 98% through an optimized and validated protocol44. Further, the ATR-Chitosan particles were synthesized using the lab-scale spray dryer in a co-current mode with two different nozzles (0.7 mm and 1 mm) without any additional excipient. The particles synthesised using both nozzles were evaluated for physico-chemical properties, in vitro drug release, ex vivo permeation study, and analytical characterization by FTIR, TG-DSC, and XRD to compare the results and understand the effect of nozzle aperture diameter on particle properties. Additionally, the cytocompatibility of the selected formulation was studied on different cell lines to understand the safety and suitability of the system.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and reagents

The active pharmaceutical ingredient, Atorvastatin Calcium (ATR) was kindly gifted from MSN Laboratories, Hyderabad, India. Chitosan was extracted in-house using the optimized protocol from the three-spot crab shells species, Portunus Sanguinolentus44. Acetic Acid, Tetrahydrofuran, Potassium Dihydrogen Phosphate (KH2PO4), and Sodium Hydroxide (NaOH) were purchased from Merck, India. Dialysis membrane (12KDa–14KDa) and Methanol were purchased from HiMedia Laboratories, India. All the chemicals and reagents used in this study were of analytical grade.

Preparation of ATR-Chitosan nanoparticles

The lab-scale spray dryer (Spray Mate, JAY Instruments, Mumbai, India) with a pneumatic nozzle, co-current air flow heating chamber, and cyclone separator was used to prepare Atorvastatin-loaded chitosan nanoparticles. Two different nozzle diameters (0.75 mm & 1 mm) were utilized to synthesize different ratios (1:0.5, 1:1, 1:2) of ATR-Chitosan particles with a constant volume of 1% acetic acid and tetrahydrofuran (THF) as solvents. Briefly, a known amount of Chitosan (125 mg, 250 mg, 500 mg) was dissolved in 150 mL 1% acetic acid and sonicated for 1 h at 25 °C, followed by stirring overnight at 200 rpm and filtered with filter paper (Whatman 42, Cytiva). Atorvastatin solution was prepared freshly on the day of spray drying by adding 250 mg of pure drug in 50 mL THF and sonicated for 30 min at 25 °C. The specified amount of drug (250 mg) was fixed based on the preliminary trials performed to understand the maximum solubility of Atorvastatin at the fixed volume of 1% acetic acid solution and Tetrahydrofuran. Completely solubilized Atorvastatin was slowly added dropwise to the prepared Chitosan solution to obtain a homogenous mixture and then subjected to the spray drying process. The drug-polymer feed solution was stirred continuously at 300 rpm while spray drying to attain uniform spraying of drug and polymer. For comparative studies, pure drug alone (without any carrier) was spray dried using 50 mL THF as solvent to assess its physico-chemical properties. The spray drying process was carried out, based on the previously optimized process parameters in our laboratory by Priya Dharshini K et al.44, such as nozzle diameter: 0.75 mm & 1 mm, feed rate: 11 mL/min, inlet temperature: 140 °C, outlet temperature: 55 °C, and air flow pressure maintained at 2 bars. Tetrahydrofuran was utilized as the solvent to achieve required drug solubility and stability, during the process. The spray-dried particles were collected from the cyclone separator and stored in a desiccator for further analysis.

Estimation of drug content of Spray-dried ATR-Chitosan nanoparticles

The amount of drug loaded into the chitosan particles was measured by dissolving 10 mg of spray-dried particles in 15 mL of 1% acetic acid: methanol (1:0.5) solution and sonicated for 30 min at 25 °C and left undisturbed overnight to attain the complete release of drug from the particles. On the next day, the solution was filtered with filter paper (Whatman 42, Cytiva), and the amount of drug present was determined by measuring absorbance at 246 nm for the drug in UV spectrophotometry (UV 1800, Shimadzu, Japan) using 1% acetic acid: methanol (1:0.5) containing an appropriate amount of chitosan as a blank. The percentage of drug loaded into the chitosan particles was calculated using the following formula,

Determination of zeta potential of nanoparticles

Zeta potential of the spray-dried particles was measured by electrophoretic light scattering (ELS) using the Zeta Sizer (Nano ZS, Malvern, UK) equipped with a He-Ne laser with wavelength 633 nm. Around 2–5 mg of the freshly prepared particles were dispersed in 2 mL of double-distilled water and sonicated in a bath sonicator (Wensar, India) for 30 min to separate physically absorbed particles. The measurement was carried out at room temperature with 20 s of equilibration time. The dispersant refractive index and dielectric constant were kept as 1.33 and 78.5, since water was used as a dispersant. Each sample was tested three times and represented as the Mean value.

Measurement of particle size and morphology

The morphology of pure drug (ATR), spray dried drug (SPD-ATR), and polymeric particles (ATR-Chitosan) was assessed using Scanning Electron Microscope (JEOL, Japan). Samples were mounted into stubs using double-sided conductive carbon tape and subjected to gold coating for 90 s with a sputter coater (Quorum Technologies, England). Then the images were taken under a higher vacuum with an accelerated voltage of 10 kV at different magnifications. Image J software was used to calculate the size of the particles by using the scale bar as a known distance45. To understand the homogeneity of particles, the frequency of size distribution was measured using GraphPad software with a bin width of five and non-linear Gaussian fitting. The polydispersity index (PDI) was calculated by dividing the square of the standard deviation (SD) by the square of the mean particle size.

Solubility studies

Solubility study for pure ATR, SPD-ATR, and ATR-Chitosan particles was conducted using the shake flask method in different media (distilled water, phosphate buffer pH 7.4, and 0.1 N HCl pH 1.2) according to the method published by Sana Inam et al., 2022. with slight modifications46. Briefly, a known amount of pure drug and formulations was added into 5 mL of respective media. The tubes were gently vortexed for 2 min and subjected to shaking for 24 h at 37 ˚C with 100 rpm speed (ORBITEK, Scigenetics Biotech, India). After 24 h, the tubes were centrifuged at 19,915 g for 15 min (Lark espin, China), and the supernatant was carefully transferred to a new tube. The amount of solubilized drug in the supernatant was quantified using UV Spectroscopy (UV 1800, Shimadzu, Japan) at λmax 246 nm. Appropriate dilutions were made with respective media whenever required, and the measurements were done in triplicate. The percentage of ATR solubility was measured using the following formula

In vitro drug release studies

The in vitro drug release study was performed using a dialysis membrane (12–14 K Da) method in different media such as phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), distilled water (pH 5.5), and 0.1 N HCl (pH 1.2) to replicate different body fluids. The dialysis membrane was soaked for 15 min in the respective media before use. Briefly, 10 mg of pure ATR, SPD-ATR, and ATR-Chitosan particles were individually added to the one-end tied dialysis bag, and 0.5 mL of respective media was added inside the bag. The other end of the bag was tied tightly with cotton thread and placed into the glass vial containing 10 mL of the respective media. The vials were maintained at continuous stirring of 200 ± 10 rpm at 37 ± 2 ˚C. At pre-determined time points, the entire 10 mL was collected and replaced with fresh warm media to maintain the seamless sink conditions and to prevent the drug from reaching the saturation solubility level. The collected samples were analyzed using a UV Spectroscopy (UV 1800, Shimadzu, Japan) at λmax 246 nm to measure the amount of ATR released using the respective media as blanks.

Drug release kinetics studies

To understand the releasing mechanism of the drug from the chitosan particles, the in vitro drug release data were fitted to different kinetics models such as zero order, first order, Higuchi, Korsmeyer-Peppas, Hixson-Crowell, Hopfenberg, Baker-Lonsdale Model, Makoid-Banakar Model, Weibull Model, and Gompertz Model using DD solver software. The regression coefficient (R2) and residual error (SSR) values were calculated and compared to determine the releasing mechanism by finding the best-fitting model47,48.

Ex vivo permeation study

Ex vivo permeation study was performed for pure ATR, SPD-ATR, and selected spray-dried ATR-Chitosan formulations (ACS3 and ACO3) using the Franz diffusion cell (surface area 3.79 Cm2)49. From the slaughterhouse, freshly excised goat buccal tissue was collected, thoroughly cleaned under running water, and the hairs were removed. The skin was then soaked with phosphate buffer for 15 min. The acceptor region of the Franz diffusion cell was filled with 20 mL of phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), and the buccal membrane was fixed between the acceptor and donor compartments by facing the mucosal area upside. About 10 mg of the sample was added carefully to the donor compartment, and then 1 mL of phosphate buffer was added. The entire setup was maintained at 37 ± 2˚C under constant stirring of 200 ± 10 rpm. At pre-determined time points, 2 mL of media was collected through the collecting arm and replaced with an equal volume of fresh warm media. The collected samples were analyzed using a UV Spectroscopy (UV 1800, Shimadzu, Japan) at λmax 246 nm using the respective blank, to measure the amount of ATR permeated. The permeation data were analysed by plotting the amount of drug permeated per area (µg/cm2) vs. time (h) to estimate the steady state flux (Jss) from the slope of the curve. The permeation coefficient was measured by dividing the flux value by the initial concentration of drug loaded at the donor side.

In vitro cytotoxicity study

The cellular toxicity of pure Atorvastatin and a selected sample of ATR-loaded chitosan nanoparticles was studied in human adipose-derived stem cells (ASCs) and differentiated ASCs (self-isolated primary cells from human adipose tissue, provided by Robert Bosch Krankenhaus, Stuttgart, Germany). All research was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by Landesärztekammer Baden-Württemberg (F-2012-078; for normal skin from elective surgeries). The study aimed to assess the safety and suitability of the nanoparticles in primary stem cells and differentiated cells. Briefly, the cells were maintained in DMEM medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS, PAN Biotech) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (PAN Biotech). For differentiation, ASCs were incubated in differentiation medium for 14 days (DMEM, 10% FCS, 1% penicillin-streptomycin, differentiation cocktail (3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthin 500 µM, indomethacin 100 µM, dexamethasone 1 µM, insulin 1 µg/mL)). The cytotoxicity assay was performed in a 48-well plate with a starting cell density of 20,000 cells per well and incubated overnight. The next day, the cells were treated with pure atorvastatin and ATR-chitosan nanoparticles at various concentrations (0.1, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 10, 25 µg/mL) in triplicate for 24 and 48 h. After the treatment period, the metabolic activity of the cells was assessed using a WST-1 Kit (TaKaRa Bio Europe) by measuring optical density (OD) at 450 nm with a correction wavelength of 620 nm.

Analytical characterization of spray dried ATR-loaded Chitosan nanoparticles

Fourier transform infrared analysis (FTIR)

The FTIR Spectra of pure ATR, pure Chitosan, and ATR-Chitosan particles were recorded using the Spectrum 100 Spectroscopy (Perkin Elmer, USA) by the potassium bromide (KBr) pellet method. The powder samples were manually mixed with moisture-free KBr and compressed into a thin pellet using a hydraulic press (50–100 Kg/Cm3). Then the KBr disc was mounted into the sample holder, and samples were scanned in the range between 4000 cm− 1 to 400 cm− 1. Prior to scanning the sample, the baseline was adjusted using a standard KBr pellet as a reference material50,51.

Thermo-Gravimetric and differential scanning calorimetric (TG-DSC) analysis

The thermal behavior of pure ATR, SPD-ATR, pure chitosan, and ATR-Chitosan particles was studied by tandem analysis of Thermogravimetric (TG) and Differential Scanning Calorimeter (DSC) (Q100, TA Instruments, USA). About 5 to 15 mg of samples were taken in an aluminium pan and sealed with an aluminium lid. The aluminium pan and the lid were inserted into the sample holder and compressed using the crimping tool. Then, the sample pan was mounted into the front pedestal of the chamber and heated from 19 °C to 900 °C with a heating rate of 20 °C/min under inert nitrogen flow (100 mL/min flow rate). An empty aluminium pan was used as a reference50,51.

Powder X-Ray diffraction (PXRD) analysis

The X-ray diffraction pattern for the pure ATR, SPD-ATR, pure Chitosan, and ATR-Chitosan particles was examined with 2-θ geometry (X-Ray source remains stationary) using the powder X-ray diffractometer (Rigaku Ultima IV, Japan). Samples were placed in the sample holder and exposed to Cu-Kα radiation generated at 30 mA and 40 kV. Samples were scanned from 5 º to 70 º at a scan speed of 2º/min with a step size of 0.02º50,51.

Results and discussions

Drug loading in spray dried ATR-Chitosan nanoparticles

The percentage of drug loaded into particles was estimated by dividing the actual amount of drug present by the theoretical drug content, which was found to be higher than 85% in all the spray-dried samples. The formulations prepared with a 0.7 mm nozzle size showed higher drug loading than the 1 mm nozzle size spray-dried formulations. The higher entrapment associated with 0.7 mm diameter nozzle could be due to the formation of smaller droplets with high surface area, which promoted rapid solvent evaporation from the droplets and prevented the drug from diffusing out during the redistribution phase of the drying process52. Analogous phenomenon for the impact of nozzle diameter on drug loading was reported previously by Shilpa Mandpe et al., using the same model of spray dryer instrument (Spray Mate, JAY Instruments, Mumbai, India53. The average results of two trials were tabulated in Table 1 with the standard deviation. The drug loading was slightly reduced as the concentration of chitosan was increased, which is consistent with the trend observed by Mohammad Karim Haidar et al., 201939. The decrease in drug loading could be because of the lesser amount of drug available per unit of polymer, as the viscosity of the solution increases when polymer concentration increases54.

Effect of zeta potential on stability of spray dried ATR-Chitosan nanoparticles

Surface charge of the particles plays a critical role in particle stability and the particle-to-cell membrane interaction in the physiological systems. To assess the stability of the synthesized particles, the zeta potential was measured based on the electrophoretic mobility method and compared with pure ATR. Pure drug showed surface charge of -14.8 mV due to the presence of an ionizable carboxylic group upon dispersion in water, while the spray-dried ATR particles (Formulation code - SAS and SAO) developed using the 0.7 mm and 1 mm nozzle size showed enhanced surface charge of -17.8 mV and − 23 mV, respectively. The increased surface charge could be attributed to the increase in charge density on the particle’s surface due to the reduction in size upon on spray drying process. The surface charge significantly shifted towards positive charge from − 8.31 mV to -1.6 mV when ATR was spray dried with chitosan (Table 1). The reduction in the surface charge could be because of the shadowing of the negative charge of the carboxylic group in Atorvastatin by the amino group in chitosan. The reduction in surface charge showed a linear trend with the increase in concentration of chitosan, for the particles spray dried using both nozzles39,55,56.

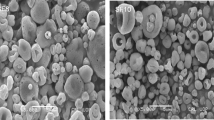

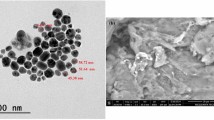

Modification of morphology and size of spray dried ATR-Chitosan nanoparticles

Surface morphology of the Pure ATR, SPD-ATR, and synthesized ATR-Chitosan particles was examined with a Scanning electron microscope at different magnifications and shown in Fig. 1 (A-I). The spray-dried ATR and polymeric formulations were uniformly spherical-shaped, while the pure ATR appeared as a rod-like structure. The powder morphology changed during the spray drying process, as the liquid was sprayed as the smallest droplets through the spherical nozzle. When chitosan and ATR are sprayed together, the particle’s surface morphology becomes rough or buckled, particularly when the chitosan concentration is higher.

The surface buckling can be described with respect to the high Peclet number, where the convection transport is faster than the diffusion transport of the solute. When the Peclet number was high, the solvent evaporation rate dominated over the solute movement, which led to rigid shell formation during droplet evaporation and resulted in particles with a shrunk or buckled morphology57,58,59. The particle size of the formulations was measured using the Image J software, specifically the measure plugin, for n = 50 particles46. This confirmed the size within the ranges of 248.2 ± 17.58 to 313.7 ± 27.76 for the 0.7 mm nozzle and 309.3 ± 26.75 to 329 ± 36.68 for the 1 mm nozzle spray dried particles (Table 1). To understand the particle homogeneity, the PDI was found to be below 0.1, which confirmed the distribution of uniform nano-sized particles formed during spray drying. It was clearly evident that particle size was highly dependent on nozzle diameter and the polymer concentration59,60,61. The increase in particle size was directly proportional and linearly correlated to the increase in polymer concentration, and a similar trend was observed in the nanoparticles developed using both nozzles. However, the mean size of the nanoparticles was smaller in the case of the 0.7 mm nozzle with lower PDI, compared to the 1 mm nozzle (Table 1)60,62. The Gaussian distribution pattern of the particle size was shown in Fig. 2 (A-F).

Solubility enhancement of spray dried ATR-Chitosan nanoparticles

The solubility studies showed very low solubility of ATR in 0.1 N HCl media (4.78 ± 0.17%) as reported earlier63, which was increased in water (20.4 ± 0.52%) and phosphate buffer (38.71 ± 2.65%) as the pH was shifted gradually from pH 5.5 towards basic condition pH 7.4, respectively (Table 2). The trend to analogous to the previously reported solubility data of pure Atorvastatin, which was noted to be highly dependent on the pH of the media, wherein the drug is insoluble at acidic media (pH ≤ 4) and very slightly soluble in the pH range of 6 to 7.464,65.

The solubility was significantly enhanced in all the media when the drug was spray dried, due to modification of the crystalline nature of the drug to an amorphous nature, which was confirmed with XRD results21. When the ATR was spray dried with different concentrations of chitosan using both nozzles, no significant changes were observed in the solubility of the drug in water and 0.1 N HCl media, which again aligned with the point of low solubility of the drug at lower pH, since ATR remained in the unionized state66. However, in the phosphate buffer pH 7.4 media, the spray dried (1 mm nozzle) ATR-Chitosan formulation showed about 1.5-fold enhancement of solubility, especially for increasing concentration of chitosan as 1:2 (50.52 ± 3.47%), as compared to pure drug (38.71 ± 2.65%). Surprisingly, this trend was not observed with the 0.7 mm nozzle-sprayed samples, which may be due to the formation of smaller droplets during spraying that aided the particles to dry more quickly, whereby the chitosan matrix was tightly packed, and the solvent had limited access to the bulk of the particles67.

Influence of spray drying & chitosan polymer on the in vitro drug release profile of the nanoparticles

The In vitro drug release was performed for a period of 10 h using the dialysis membrane method at different pH conditions, like phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) to represent blood environment, 0.1 N HCl (pH 1.2) to represent the gastric acidic site and distilled water (pH 5.5) to understand the exact solubility enhancement in aqueous condition. The pure drug release was observed to be higher in phosphate buffer, followed by water, and minimal at 0.1 N HCl media in all the samples (Fig. 3). Irrespective of the nozzle diameter, the cumulative release of ATR was enhanced in phosphate buffer and water media after spray drying. The improved drug release of spray-dried ATR was due to a change in solid-state arrangement from crystalline to amorphous nature, which could provide higher solvent penetration into the particles. However, this trend was not observed in 0.1 N HCl media, wherein the drug release behavior remained similar to pure ATR, since the drug was available in unionized form under acidic conditions, which reduced its solubility66. The poor drug release in 0.1 N HCl media was due to reduced saturation solubility of Atorvastatin at acidic conditions, which was also reflected in the solubility study. Atorvastatin is a weakly acidic compound with a pKa value of 4.4, which indicates that the drug will change into a unionized form under acidic conditions. At low pH, the carboxylic group in Atorvastatin accepts a proton from the surrounding media and becomes a unionized form62. However, when ATR was spray dried with chitosan, the drug releasing behavior was enhanced in 0.1 N HCl media, also, which was linear with the increase in the concentration of chitosan. This could be attributed to chitosan, as it is known to swell and dissolve at acidic pH through protonation of the amino group (NH2 to NH3+), which allows the diffusion of water molecules and subsequently enhances the dissolution of the drug68. Improved dissolution in gastric conditions prevents the drug from degradation during low gastric emptying time by enhancing the oral absorption of the drug69. A similar trend of drug release was observed in phosphate buffer media, with a higher rate, regardless of the nozzle diameter. Also, the faster drug release was clearly obvious with the higher ratio of chitosan (ACS3 and ACO3), which could be due to enhanced solubility of Atorvastatin at pH 6.5 to 7.570. The drug release pattern in water (pH 5.5) was higher than in 0.1 N HCl media and lower than in phosphate buffer media (pH 7.4). In distilled water media, an astonishing trend was noted. For instance, when the concentration of chitosan was increased, the drug release was reduced, which was also reflected in the solubility study. This slow drug release profile at a higher ratio of chitosan might be due to more loading of the drug in the polymer matrix and delayed solubility of the polymer in aqueous media71. When the ratio of chitosan to drug was increased, the presence of more polymer around the drug hampered the interaction of water molecules with the drug and retarded its dissolution. In a nutshell, the drug release was notably enhanced in pH conditions of 7.4 and 1.2, especially at a high ratio of chitosan spray dried with ATR (formulation code - ACS3 and ACO3), which would be favorable for enhanced absorption of the drug into the systemic circulation from the gastrointestinal tract.

Kinetic mechanisms involved in the drug release from nanoparticles

The in vitro drug release data as a function of time in different pH media conditions were fitted into various mathematical kinetics models using the DD solver plugin in Microsoft Excel. This mathematical modelling serves as a pioneer to understand the exact phenomena of drug release that would occur in the in vivo biological systems. The accuracy and best fitting of the model were assessed by considering parameters such as correlation coefficient (R2), Sum of square error (SSE), and ‘n’ value in the case of the Korsmeyer-Peppas, Makoid-Banakar, and Hopfenberg models, which represent the type of Fickian transport. The formulation was spray-dried using both nozzle sizes, followed by three main models, such as Weibull, Korsmeyer-Peppas, and Makoid-Banakar, with the highest R2 and the least SSE (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). Correlation with the Weibull and Korsmeyer-Peppas model confirmed that the synthesized nanoparticles are of a matrix type72 a standard type of carrier system typically produced by spray drying. Makoid Banakar is a similar model to Korsmeyer Peppas’ model, with an extra exponential factor in the equation, where these two models help to understand the type of Fickian transport taking place from the delivery system based on the n-value48. The n-value below 0.4 indicates that the system follows Fickian transport, and the n-value between 0.45 < n < 0.89 is assumed to be non-Fickian transport, where the drug release depends on matrix swelling and erosion. In our case, the values were between 0.45 < n < 0.78 in all the media, which confirmed that the release of ATR from the nanoparticles was not based on diffusion (non-Fickian), whereas it depends on polymer swelling and degradation47. Additionally, the Makoid Banakar model has been considered as a model-independent approach, which could explain the drug release phenomenon based on drug-polymer interactions.

Impact of Chitosan and spray nozzle size on ex vivo permeation of the nanoparticles

The Ex vivo permeation study was conducted for eight hours in phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) for selected formulations (ACS3 and ACO3) and compared to pure ATR, spray-dried ATR (SAS and SAO), in order to determine the impact of chitosan and spray nozzle size on ATR permeation through the biological membrane. The amount of drug permeated per unit area (µg/cm2) was plotted against the time (h), and the slope of the straight line was used to calculate the steady state flux (Fig. 4). The steady state flux is described as the rate of drug passing through a unit area of the membrane over a given time49. Pure ATR showed steady flux and permeation coefficient of 3.88 ± 0.4 µg/cm2/h and 0.00038 ± 0.00004 cm/h, respectively. Spray drying of pure drug alone did not enhance the permeation coefficient (for both nozzles sprayed samples), while the ATR-Chitosan nanoparticles formulation (ACS3 and ACO3) showed a higher permeation coefficient (0.00087 ± 0.00028 cm/h and 0.00130 ± 0.00008 cm/h, respectively), which clearly showed the impact of chitosan in permeation enhancement of ATR. Chitosan, a natural polymer with known mucoadhesive properties with a positively charged amino group in its backbone, interacts with the negatively charged cell membrane, which could enhance the permeation of the drug72.

In vitro cytotoxicity study

The cytocompatibility of pure ATR and ATR-loaded chitosan nanoparticles was examined in proliferating and differentiated ASCs over 24 and 48 h. The metabolic activity results are shown in Fig. 5 (A-D). For proliferating ASCs, pure Atorvastatin was toxic at concentrations of 10 µg/mL and 25 µg/mL after both 24 and 48 h. This toxicity was reduced when formulated with chitosan nanoparticles at 24 h. ASCs treated with nanoparticles exhibited significantly higher metabolic activity at concentrations of 10 and 25 µg/mL after 24 h, as well as at 0.5, 1, 10, and 25 µg/mL. Similarly, when stem cells differentiated into adipocytes, Atorvastatin exhibited minimal toxicity at 24 h and 48 h. Differentiated ASCs treated with the nanoparticles displayed significantly higher metabolic activity across all tested concentrations, indicating a beneficial effect of the nanoparticle formulation on metabolic activity.

In vitro cytotoxicity study of pure ATR and ATR-loaded chitosan nanoparticles on ASCs and differentiated ASCs for 24 h and 48 h. (A) Metabolic activity (by WST assay, normalized to untreated control) of ASCs treated with different concentrations of pure ATR and ATR-nanoparticles (NP-ATR) after 24 h. (B) Metabolic activity of ASCs treated with different concentrations of pure ATR and NP-ATR after 48 h. (C) Metabolic activity of differentiated ASCs treated with different concentrations of pure ATR and NP-ATR after 24 h. (D) Metabolic activity of differentiated ASCs treated with different concentrations of pure ATR and NP-ATR after 48 h. Mean values are displayed ± SD. Data are representative of three independent experiments with three different biological donors. Data were analyzed using two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by a post hoc test (Šídák). Statistics were conducted with GraphPad Prism 10.1.2. *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001.

Analytical characterization studies of the spray dried ATR-Chitosan nanoparticles

To understand the drug-polymer interactions after entrapping ATR into a chitosan matrix, the selected formulations were analyzed through various analytical techniques, such as Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, thermogravimetry differential scanning calorimetry (TG-DSC) analysis, and X-ray diffraction (XRD) studies.

Chemical interactions between ATR and Chitosan during spray drying process

The pure ATR, pure chitosan, and ATR-loaded chitosan nanoparticles were analyzed with FTIR to confirm the incorporation of the drug into a polymeric matrix, and the obtained spectrum is shown in Fig. 6. Pure ATR showed notable transmittance bands at 3365 cm− 1 corresponding to secondary -NH stretching and a broad band between 3200 cm− 1 and 3200 cm− 1corresponding to symmetric -OH stretching. The broadening of the -OH stretching was due to the strong intermolecular hydrogen bonding between the hydroxy groups. Peaks at 3056 cm− 1, 2942 cm− 1, and 2970 cm− 1 correspond to the symmetric and asymmetric stretching of the = C-H group. The higher intense peak at 1651 cm-1, 1552 cm− 1, 1469 cm− 1, 1213 cm− 1, 1154 cm− 1 represented the -C = O, -C = C, -C-H, -C-N, -C-F vibrations, respectively. The pure chitosan polymer showed peaks at 3447 cm− 1 (-OH stretching), 1637 cm− 1 (C = C stretching) and 1437 cm− 1(-C-H stretching). The ATR-loaded chitosan nanoparticles also showed similar transmittance peaks to the pure drug with a mild shift at 3404 cm− 1 (-N-H stretching), 2965 cm− 1 (= C-H stretching), 1652 cm− 1 (-C = O stretching), and 1565 cm− 1 (C = C stretching). The mild shift in peak might be because of drug-polymer interactions, which also favored the drug release mechanism. Also, the drug polymer interaction reduced the broadening of the -OH stretching peak in the case of ATR-Chitosan formulation. The presence of the ATR peak in the spray-dried sample confirmed the active loading of the drug into the polymeric matrix with negligible chemical modifications23,25,64.

Effect of spray drying technique and Chitosan polymer on solid state transition of ATR

Samples of pure ATR, spray-dried ATR, pure chitosan and ATR-loaded chitosan nanoparticles were subjected to powder XRD analysis to examine the change in crystalline state during spray drying, and the spectrum is shown in Fig. 7. Pure ATR showed multiple sharp intense peaks at 2θ (9.7, 10.9, 12.5, 17.5, 20.0, 22.1, 23.1, 24.1), which confirmed the crystalline arrangement of the drug in the native form I50. To assess the changes that occurred during the spray drying process, the spray-dried Atorvastatin (without polymer) was analyzed, which showed the complete disappearance of the sharp peaks due to the phase transition from crystalline to amorphous. The ATR-loaded chitosan nanoparticles showed a significant reduction in intensity of the peaks of ATR, suggesting that the drug molecules were transformed from native crystalline form to an amorphous state. Similar kind of phase transformation was also observed by Jaewook Kwon et al., when Atorvastatin was spray dried with hydroxyl propyl methyl cellulose (HPMC)22. The pattern observed in the spray-dried ATR (SPD-ATR) without chitosan polymer matrix also validated the similar phenomenon of change in crystallinity of the drug during the spray drying process.

Thermal stability analysis of spray dried ATR-Chitosan nanoparticles

TG analysis was carried out to study the thermal properties and physical state of ATR loaded in the chitosan matrix. Figure 8A shows the Thermogravimetric (TG) graph of pure ATR, pure chitosan, and ATR-loaded chitosan nanoparticles. The ATR used in the present study was Atorvastatin calcium trihydrate (Form I) with a ratio of 2:1:3 (Atorvastatin)2. (Ca2+)1. (H2O)3 (Molecular weight: 1209.39 g/mol), which is commonly available in the market73. The trihydrate salt of ATR follows a four-step degradation with initial water removal followed by decomposition. The degradation pattern was similar to the reports of Niels Peter Aae Christensen et al., with one water molecule removal at 40–68 °C, 85–101 °C, 101–131 °C, followed by complete degradation starting at 180 °C51,74. The trihydrate form of Atorvastatin calcium has one surface-bound water molecule and two water molecules bound to two calcium atoms. At first, the surface-bound water molecule lost between 40 and 68 °C with mass loss of 1.5%, followed by loss of calcium-interacted water molecules at 85–101 °C and 101–131 °C with mass loss of 1.43% and 1.39%, respectively. Chitosan alone showed a gradual degradation pattern starting from 70 °C, with complete degradation at 750 °C. In the case of ATR-loaded chitosan spray-dried nanoparticles, the degradation pattern was faster in two steps compared to the pure drug, which might be due to the phase transition of the drug to an amorphous state, wherein the heat transfer rate could be faster compared to the native crystalline form.

To further understand the phase transition of the drug during spray drying, differential scanning calorimeter analysis was carried out simultaneously for the pure drug, pure polymer, and drug-loaded polymeric nanoparticles (Fig. 8B). ATR showed a broad endothermic peak between 25 and 90 °C and a sharp peak at 144 °C, due to the removal of three water molecules and the glass transition temperature (Tg) of ATR, respectively. The observed pattern of heat flow was similar to that observed by Afreen Naqvi et al.75. However, the melting peak (Tm) was not observed in our results, which could be because of the faster heating rate (20 ˚C/min) in the analytical process performed. In case of ATR-loaded chitosan nanoparticles, the Tg peak of the drug was completely reduced, which confirmed the conversion of the drug to an amorphous form during the spray drying process, as evidenced by the XRD analysis.

Conclusion

In this study, improved solubility of Atorvastatin was achieved by loading Atorvastatin into a Chitosan matrix through the spray drying technique. We have assessed the effect of two important parameters, nozzle diameter and polymer concentration, on the characteristics of the synthesized nanoparticles. The polymer concentration and nozzle diameter determined the particle size, with the 0.7 mm nozzle size producing smaller particles with a highly homogeneous distribution. The concentration of chitosan dictated the stability of the nanoparticles, wherein an increase in solubility and dissolution of the drug was achieved by increasing the concentration in all three bio-relevant media, which confirmed the suitability of the developed product for parenteral administration. Additionally, the presence of chitosan enhanced the drug permeation by interacting with the cell membrane components. The nanoparticle formulation was also beneficial for the metabolic activity compared to the pure drug. The analytical characterization of pure drug and ATR-Chitosan nanoparticles confirmed that the drug was entrapped in an active form with changes in crystal arrangement to the amorphous phase. Hence, our findings showed that the formulation of Atorvastatin with chitosan would enhance the solubility to a higher extent in different biological environments, which could enhance the bioavailability of the drug in physiological conditions.

Data availability

The data generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available, but are available from the corresponding author at Pharmaceutical Technology Laboratory, School of Chemical & Biotechnology, SASTRA Deemed University, Thanjavur-613401, Tamil Nadu, India, Email - [ramya@scbt.sastra.edu](mailto: ramya@scbt.sastra.edu).

References

Libby, P. et al. Atherosclerosis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 5(1), 56 (2019).

Vaduganathan, M., Mensah, G. A., Turco, J. V., Fuster, V. & Roth, G. A. The Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases and Risk: A Compass for Future Health Vol. 80, p. 2361–2371 Journal of the American College of Cardiology (Elsevier Inc., 2022).

Jebari-Benslaiman, S. et al. Pathophysiology of Atherosclerosis. Vol. 23, International Journal of Molecular Sciences. (MDPI, 2022).

Yanai, H., Adachi, H., Hakoshima, M. & Katsuyama, H. Molecular Biological and Clinical Understanding of the Statin Residual Cardiovascular Disease Risk and Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Alpha Agonists and Ezetimibe for its Treatment. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 23. (MDPI, 2022).

Gimbrone, M. A. & García-Cardeña, G. Endothelial cell dysfunction and the pathobiology of atherosclerosis. Circ. Res. 118 (4), 620–636 (2016).

Dietschy, J. M. & Turley, S. D. Control of cholesterol turnover in the mouse. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 3801–3804 (2002).

Jiang, T et.al. Dual Targeted delivery of Statins and nucleic acids by chitosan-based nanoparticles for enhanced antiatherosclerotic efficacy. Biomaterials. 280, 121324, (2022).

Stancu, C., Sima, A. & Statins Mechanism of action and effects. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 5 (4), 378–387 (2001).

Sirtori, C. R. The Pharmacology of statins. Vol. 88, Pharmacological Research p. 3–11 (Academic, 2014).

Schönbeck, U., Libby, P. Inflammation Immunity, and HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors. Circulation 109(21 Suppl 1), II18–II26 (2004).

Matyori, A., Brown, C. P., Ali, A. & Sherbeny, F. Statins utilization trends and expenditures in the U.S. Before and after the implementation of the 2013 ACC/AHA guidelines. Saudi Pharm. J. 31 (6), 795–800 (2023).

Markowska, A., Antoszczak, M., Markowska, J., Huczyński, A. & Statins Hmg-coa Reductase Inhibitors as Potential Anticancer Agents against Malignant Neoplasms in Women Vol. 13, p. 1–13 (Pharmaceuticals. MDPI AG, 2020).

Tatham, L. M., Liptrott, N. J., Rannard, S. P. & Owen, A. Long-acting Injectable statins—is It time for a Paradigm shift? Vol. 24 (MDPI AG, 2019).

Yamada, Y. et al. Atorvastatin reduces cardiac and adipose tissue inflammation in rats with metabolic syndrome. Int. J. Cardiol. 240, 332–338 (2017).

Schachter, M. Chemical, pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties of statins: An update. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 19, 117–25. (2005).

Sasaki, J. et al. A 52-Week, Randomized, Open-Label, Parallel-Group comparison of the tolerability and effects of Pitavastatin and Atorvastatin on High-Density lipoprotein cholesterol levels and glucose metabolism in Japanese patients with elevated levels of Low-Density lipoprotein cholesterol and glucose intolerance. Clin. Ther. 30 (6), 1089–1101 (2008).

Ramkumar, S., Raghunath, A. & Raghunath, S. Statin Therapy: Review of Safety and Potential Side Effects Vol. 32, p. 631–639 (Republic of China Society of Cardiology, 2016). Acta Cardiologica Sinica.

Althanoon, Z., Faisal, I. M., Ahmad, A. A., Merkhan, M. M., & Merkhan, M. M. Pharmacological aspects of statins are relevant to their structural and physicochemical properties. Systematic Reviews in Pharmacy, 11(7), 167-171 (2020).

Jeeyavudeen, M. S., Pappachan, J. M. & Arunagirinathan, G. Statin-related muscle toxicity: an Evidence-based review. touchREVIEWS Endocrinol. 18, 89–95. (2022).

Muntean, D. M. et al. Statin-associated Myopathy and the Quest for Biomarkers: Can We Effectively Predict statin-associated Muscle symptoms? Vol. 22, p. 85–96 (Elsevier Ltd, 2017). Drug Discovery Today.

Kim, J. S. et al. Physicochemical properties and oral bioavailability of amorphous Atorvastatin hemi-calcium using spray-drying and SAS process. Int. J. Pharm. 359 (1–2), 211–219 (2008).

Kwon, J. et al. Spray-dried amorphous solid dispersions of Atorvastatin calcium for improved supersaturation and oral bioavailability. Pharmaceutics. 11(9), 461 (2019).

Shaker, M. A., Elbadawy, H. M. & Shaker, M. A. Improved solubility, dissolution, and oral bioavailability for atorvastatin-Pluronic® solid dispersions. Int. J. Pharm. 574, 118891 (2020).

Grune, C. et al. Sustainable Preparation of anti-inflammatory Atorvastatin PLGA nanoparticles. Int. J. Pharm. 599, 120404 (2021).

Abdelkader, D. H., Abosalha, A. K., Khattab, M. A., Aldosari, B. N. & Almurshedi, A. S. A novel sustained anti-inflammatory effect of atorvastatin— calcium Plga nanoparticles: in vitro optimization and in vivo evaluation. Pharmaceutics. 13(10), 1658 (2021).

Nenna, A. et al. Polymers and nanoparticles for Statin delivery: current use and future perspectives in cardiovascular disease. Polym. (Basel). 13 (5), 1–14 (2021).

Garrett, I. R. et al. Locally delivered Lovastatin nanoparticles enhance fracture healing in rats. J. Orthop. Res. 25 (10), 1351–1357 (2007).

Duivenvoorden, R. et al. A statin-loaded reconstituted high-density lipoprotein nanoparticle inhibits atherosclerotic plaque inflammation. Nat. Commun. 5(1), 3065 (2014).

Bernkop-Schnürch, A. & Dünnhaupt, S. Chitosan-based drug delivery systems. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 81, 463–469 (2012).

Estevinho, B. N., Rocha, F., Santos, L. & Alves, A. Microencapsulation with Chitosan by spray drying for industry applications - A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 31, 138–155 (2013).

Kumar Dutta, P., Dutta, J. & Tripathi, V. S. Chitin and Chitosan: Chemistry, Properties and Applications Vol. 63 (Journal of Scientific & Industrial Research, 2004).

Vicente, F. A. et al. Crustacean waste biorefinery as a sustainable cost-effective business model. Chem. Eng. J. 442, 135937 (2022).

Zaker, M. A. et al. Injectable Chitosan/Gelatin-based microparticles generated by microfluidic systems for synergic chemophotodynamic therapy against breast cancer. J. Drug Deliv Sci. Technol. 108, 106904 (2025).

Sultan, M. H. et al. Characterization of cisplatin-loaded Chitosan nanoparticles and rituximab-linked surfaces as target-specific injectable nano-formulations for combating cancer. Sci. Rep. 12(1), 468 (2022).

Malamatari, M., Charisi, A., Malamataris, S., Kachrimanis, K., & Nikolakakis, I. Spray drying for the preparation of nanoparticle-based drug formulations as dry powders for inhalation. Processes, 8(7), 788 (2020).

Ahmed, A. B., Konwar, R. & Sengupta, R. Atorvastatin calcium loaded Chitosan nanoparticles: in vitro evaluation and in vivo Pharmacokinetic studies in rabbits. Brazilian J. Pharm. Sci. 51 (2), 467–477 (2015).

Rohilla, R., Garg, T., Bariwal, J., Goyal, A. K. & Rath, G. Development, optimization and characterization of glycyrrhetinic acid–chitosan nanoparticles of Atorvastatin for liver targeting. Drug Deliv. 23 (7), 2290–2297 (2016).

Anwar, M. et al. Enhanced bioavailability of nano-sized chitosan-atorvastatin conjugate after oral administration to rats. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 44 (3), 241–249 (2011).

Haidar, M. K. et al. Atorvastatin-loaded nanosprayed Chitosan nanoparticles for peripheral nerve injury. Bioinspired Biomim. Nanobiomaterials. 9 (2), 74–84 (2020).

Algharib, S. A. et al. Preparation of Chitosan nanoparticles by ionotropic gelation technique: effects of formulation parameters and in vitro characterization. J. Mol. Struct. 1252, 132129 (2022).

Masarudin, M. J., Cutts, S. M., Evison, B. J., Phillips, D. R. & Pigram, P. J. Factors determining the stability, size distribution, and cellular accumulation of small, monodisperse Chitosan nanoparticles as candidate vectors for anticancer drug delivery: application to the passive encapsulation of [14 C]-doxorubicin. Nanotechnol Sci. Appl. 8, 67–80 (2015).

Costa, E. M., Silva, S. & Pintado, M. Chitosan nanoparticles production: optimization of physical Parameters, biochemical Characterization, and stability upon storage. Appl. Sci. (Switzerland). 13(3),1900 (2023).

Gutiérrez-Ruíz, S. C. et al. Optimize the parameters for the synthesis by the ionic gelation technique, purification, and freeze-drying of chitosan-sodium tripolyphosphate nanoparticles for biomedical purposes. J. Biol. Eng. 18(1), 12 (2024).

Priya Dharshini, K. et al. pH-sensitive Chitosan nanoparticles loaded with dolutegravir as milk and food admixture for paediatric anti-HIV therapy. Carbohydr. Polym. 256, 117440 (2021).

Narayanan, V. H. B. et al. Spray-dried Tenofovir alafenamide-chitosan nanoparticles loaded oleogels as a long-acting injectable depot system of anti-HIV drug. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 222, 473–486 (2022).

Inam, S. et al. Development and Characterization of Eudragit® EPO-Based Solid Dispersion of Rosuvastatin Calcium to Foresee the Impact on Solubility, Dissolution and Antihyperlipidemic Activity. Pharmaceuticals. 15(4), 492 (2022).

Ramteke, K. H., Dighe, P. A., Kharat, A. R., & Patil, S. V. Mathematical models of drug dissolution: A review. Sch. Acad. J. Pharm, 3(5), 388-396 (2014)

Ojsteršek, T., Vrečer, F. & Hudovornik, G. Comparative fitting of mathematical models to carvedilol release profiles obtained from hypromellose matrix tablets. Pharmaceutics 16(4), 498 (2024).

Ramyadevi, D., Rajan, K. S., Vedhahari, B. N., Ruckmani, K. & Subramanian, N. Heterogeneous polymer composite nanoparticles loaded in situ gel for controlled release intra-vaginal therapy of genital herpes. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces. 146, 260–270 (2016).

da Silva, K. M. A. et al. Characterization of solid dispersions of a powerful Statin using thermoanalytical techniques. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 138 (5), 3701–3714 (2019).

Meddeb, N., Elmhamdi, A., Aksit, M., Galai, H. & Nahdi, K. Constant Rate Thermal Analysis Study of a Trihydrate Calcium Atorvastatin and Effect of Grinding on its Thermal Stability. Journal of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry. 148, 11425–11433 (Springer Science and Business Media B.V., 2023).

Alhajj, N., O’Reilly, N. J. & Cathcart, H. Designing Enhanced Spray Dried Particles for Inhalation: A Review of the Impact of Excipients and Processing Parameters on Particle Properties. Powder Technology. 384, 313–331 (Elsevier B.V., 2021).

Mandpe, S. et al. Design, development, and evaluation of spray dried flurbiprofen loaded sustained release polymeric nanoparticles using QBD approach to manage inflammation. Drying Technol. 41 (15), 2418–2430 (2023).

Kumara, J. B. V., Ramakrishna, S. & Madhusudhan, B. Preparation and characterisation of Atorvastatin and curcumin-loaded Chitosan nanoformulations for oral delivery in atherosclerosis. In: IET Nanobiotechnology. Institution of Engineering and Technology 96–103. (2017).

Kurakula, M., El-Helw, A. M., Sobahi, T. R. & Abdelaal, M. Y. Chitosan based Atorvastatin nanocrystals: effect of cationic charge on particle size, formulation stability, and in-vivo efficacy. Int. J. Nanomed. 10, 321–334 (2015).

Wei, Y., Huang, Y. H., Cheng, K. C. & Song, Y. L. Investigations of the influences of processing conditions on the properties of spray dried Chitosan-Tripolyphosphate particles loaded with Theophylline. Sci. Rep. 10(1), 1155 (2020).

Santos, D., Maurício, A. C., Sencadas, V., Santos, J. D., Fernandes, M. H., & Gomes, P. S. Spray drying: an overview. Biomaterials-Physics and Chemistry-New Edition, 2, 9-35 (2018).

Vehring, R. Pharmaceutical particle engineering via spray drying. Pharm. Res. 25, 999–1022 (2008).

Rizi, K., Green, R. J., Donaldson, M. & Williams, A. C. Production of pH-responsive microparticles by spray drying: investigation of experimental parameter effects on morphological and release properties. J. Pharm. Sci. 100 (2), 566–579 (2011).

Beck-Broichsitter, M. et al. Characterization of novel spray-dried polymeric particles for controlled pulmonary drug delivery. J. Controlled Release. 158 (2), 329–335 (2012).

Elversson, J. & Millqvist-Fureby, A. Particle size and density in spray drying - Effects of carbohydrate properties. J. Pharm. Sci. 94 (9), 2049–2060 (2005).

Elversson, J. et al. Droplet and particle size relationship and shell thickness of inhalable Lactose particles during spray drying. J. Pharm. Sci. 92, 900-910 (2003).

Park, J. W. et al. Supersaturated Gel Formulation (SGF) of Atorvastatin at a Maximum Dose of 80 mg with Enhanced Solubility, Dissolution, and Physical Stability. Gels 10(12), 837 (2024).

Alsmadi, M. M., AL-Daoud, N. M., Obaidat, R. M. & Abu-Farsakh, N. A. Enhancing Atorvastatin in vivo oral bioavailability in the presence of inflammatory bowel disease and irritable bowel syndrome using supercritical fluid technology guided by WbPBPK modeling in rat and human. AAPS PharmSciTech 23(5), 148 (2022).

Zhang, H. X. et al. Micronization of Atorvastatin calcium by antisolvent precipitation process. Int. J. Pharm. 374 (1–2), 106–113 (2009).

Taha, D. A. et al. The role of acid-base imbalance in statin-induced myotoxicity. Translational Res. 174, 140–160e14 (2016).

Sosnik, A. & Seremeta, K. P. Advantages and Challenges of the spray-drying Technology for the Production of Pure Drug Particles and Drug-loaded Polymeric Carriers Vol. 223, p. 40–54 (Elsevier B.V., 2015). Advances in Colloid and Interface Science.

Abd El-Hady, M. M. & El-Sayed Saeed, S. Antibacterial properties and pH sensitive swelling of insitu formed silver-curcumin nanocomposite based Chitosan hydrogel. Polym. (Basel). 12 (11), 1–14 (2020).

Abuhelwa, A. Y., Williams, D. B., Upton, R. N. & Foster, D. J. R. Food, Gastrointestinal pH, and Models of Oral Drug Absorption Vol. 112, p. 234–248 (Elsevier B.V., 2017). European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics.

Lennernäs, H. Clin Pharmacokinet 42 (13), 1141–1160 (2003).

Sogias, I. A., Khutoryanskiy, V. V. & Williams, A. C. Exploring the factors affecting the solubility of Chitosan in water. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 211 (4), 426–433 (2010).

Gjoseva, S. et al. Design and biological response of Doxycycline loaded Chitosan microparticles for periodontal disease treatment. Carbohydr. Polym. 186, 260–272 (2018).

Tizaoui, C. et al. Does the trihydrate of Atorvastatin calcium possess a melting point? Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 148, 105334 (2020).

Christensen, N. P. A. et al. Rapid insight into heating-induced phase transformations in the solid state of the calcium salt of Atorvastatin using multivariate data analysis. Pharm. Res. 30 (3), 826–835 (2013).

Naqvi, A. et al. Preparation and evaluation of pharmaceutical co-crystals for solubility enhancement of Atorvastatin calcium. Polym. Bull. 77 (12), 6191–6211 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The corresponding author is thankful to IGSTC WISER 2023 Award for the funding support and the authors are thankful to SASTRA Deemed University, India and Reutlingen University, Germany for the laboratory infrastructure and online resources support.

Funding

Indo-German Science and Technology Centre (IGSTC) under the scheme of Women Involvement in Science Engineering and Research (WISER) Award 2023 (IGSTC/WISER2023/RDD/40/2023-24/773).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Corresponding author RD proposed the research and obtained funding. Authors RV, VHBN and RD are involved in the design and development of the formulation and its optimization studies. RV performed the experiments and generated the data, while AS assisted in the investigations. VHBN and RD aided in the analysis of raw data for all the experiments. Authors SN and SN was involved in the cytotoxicity studies and its interpretation, under the guidance of PK. Authors BK and MB supported to perform the analytical characterization studies. RV drafted the manuscript and all the other authors had critically revised and approved it.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Venkatraman, R., B. Narayanan, V.H., Nowakowski, S. et al. Engineered biodegradable polymeric nanoparticles injectable system of atorvastatin for improved therapeutic activity. Sci Rep 16, 1538 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31548-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31548-3