Abstract

School-aged children globally face declining physical fitness and postural health, yet evidence-based, scalable interventions within physical education (PE) curricula are limited. This school-based cluster intervention trial was conducted over a semester in Beijing, China. Two primary schools, matched for demographics and resources, were allocated to the intervention or control groups. The intervention group received functional training integrated into school PE, whereas the control group continued the usual PE. Improvements in physical fitness and postural health (including forward head posture [FHP] and uneven shoulders) were the primary outcomes of this study. In total, 1,286 participants were allocated to the intervention group (n = 601) and control group (n = 685). The baseline characteristics of the participants were similar. At 16 weeks, the intervention group demonstrated greater improvements in physical fitness (mean difference 0.77 [95% CI: 0.48–1.05], Cohen’s d = 0.28, P < 0.001). Postural health improved, with the FHP prevalence reduced by 12.6% (risk ratio [RR], 0.65 [95% CI: 0.54–0.78]; P < 0.001), and uneven shoulders prevalence decreased by 23.3% (RR, 0.51 [95% CI: 0.42–0.65]; P < 0.001). Integrating functional training into school PE significantly improved physical fitness and postural health. These findings support its use as a scalable public health intervention to address declining physical fitness and postural health in school-aged children.

Trial Registration: This trial was registered at the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (ChiCTR-2500104984, 26/06/2025).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Epidemiological evidence increasingly indicates that declining physical fitness contributes to a growing health burden in China1. Physical fitness, defined as a set of attributes that determine the ability to perform physical activity, encompasses two primary domains: health-related and skill-related fitness2. Health-related fitness includes cardiorespiratory fitness, musculoskeletal fitness (including muscular strength and endurance), body composition, and flexibility, all of which are directly associated with overall health3,4. Skill-related fitness, reflecting abilities relevant for sports or occupational performance, is associated with motor skills and includes components such as speed, power, coordination, agility, and balance5,6. Physical fitness in childhood is integral to a broad spectrum of health benefits, including cardiovascular, metabolic, skeletal, and psychological well-being7,8,9.

Abnormal physical posture, defined as a significant deviation from optimal body segment alignment, has become a major public health issue among children10,11. Evidence suggests a high prevalence of this condition, with some studies reporting that up to 68% of children exhibit at least one postural abnormality, such as forward head posture (FHP) or uneven shoulders12,13,14. Notably, cross-sectional studies have reported abnormal physical posture rates of 30–50% in primary school children in some countries12,15. Abnormal physical posture, often indicative of underlying sensorimotor dysfunction, can lead to negative outcomes including musculoskeletal pain, reduced cardiorespiratory function, and decreased physical endurance16,17.

Muscle-strengthening exercise (MSE) is fundamental for developing musculoskeletal fitness and addressing neuromuscular deficits underlying abnormal posture18,19,20,21. Functional training, an MSE variant emphasizing multi-joint, movement-pattern-based exercises, offers a theoretically promising approach for simultaneously improving physical fitness and postural health by enhancing core stability and movement efficiency22,23,24. Distinct from traditional resistance training, which isolates single muscle groups along fixed trajectories25, this approach closely replicates actual sports movements. Furthermore, it has been proven to offer unique advantages for improving athletic performance22,26,27,28. These characteristics position functional training as a viable and promising approach for improving overall physical fitness and postural health in school-aged children.

Although evidence suggests that MSE can improve physical fitness and postural health, the quality of this evidence is limited by small sample sizes26,29,30, reliance on specialized athletic training programs rather than integrated curricular approaches26,29,31,32, and a predominance of studies involving clinical populations or adolescents rather than children25,33,34,35,36. To our knowledge, no MSE intervention has yet developed exercise protocols that simultaneously target physical fitness and postural health using functional training among primary-school children.

Given the limited high-quality evidence and uncertainties regarding the effectiveness of functional training in school-based children, this study evaluated the impact of integrating functional training into school physical education (PE) on both physical fitness and postural health. It was hypothesized that functional training would simultaneously enhance these outcomes due to their biomechanical interdependence. These findings may inform the development of scalable, evidence-based public health policies to address the dual burden of declining physical fitness and postural health among school-aged children.

Methods

Study design and participants

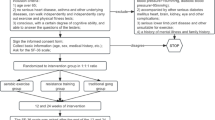

This intervention study was conducted among fifth-grade students (aged 9–11 years) from two demographically matched primary schools in Beijing, who were assigned to either the intervention or the control group (1:1 allocation). Inclusion criteria were: (1) age 9–11 years and enrolled in the 5th grade of elementary school, and (2) ability to complete baseline health assessment and questionnaires. Exclusion criteria included: (1) physical disabilities preventing participation in school PE, (2) planning to transfer schools within a year, and (3) severe mental health conditions impairing compliance with study procedures. Participants were recruited between April and June 2024, with the intervention implemented in September 2024 and the first follow-up conducted in December 2024, resulting in a total intervention duration of 16 weeks (see Fig. 1). This 16-week duration, corresponding to one academic semester, was selected based on previous school-based interventions demonstrating its sufficiency for inducing meaningful changes in children’s physical health outcomes25,37,38. The intervention was delivered by four in-service PE teachers, all of whom held a bachelor’s degree in physical education and were initially employed by the participating schools. Each teacher was responsible for teaching four to five classes of fifth-grade students. Due to the nature of the behavioral intervention, the PE teachers were aware of group allocation, while participants, their families, and the outcome assessors and statisticians remained blinded.

Sample size determination

The sample size was calculated to detect a clinically meaningful difference of 0.1 standard deviations in Physical Fitness Indicators (PFI) scores with 95% power at a two-sided alpha of 0.05. The initial sample size (n₁) for an individually randomized trial was estimated using G*Power. This initial estimate was then multiplied by the design effect (DE = 1 + (m − 1) * ICC), where m = 30 (average cluster size) and ICC = 0.02, to account for school-level clustering39. The resulting sample size was then increased by 20% to compensate for an anticipated attrition rate, which was assumed due to potential survey non-participation during the final exam week at the end of the semester, especially for the questionnaire investigation. This adjustment yielded a final target of 520 participants per group. Oversampling was used, yielding 601 participants in the intervention group and 685 in the control group. This approach provided sufficient power to detect the predefined clinically meaningful difference in physical fitness scores between the groups.

Intervention

The intervention protocol, detailed in Fig. 2 and the Appendix, was developed in January 2024 by a multidisciplinary expert panel, including specialists in sports science and child and adolescent health. The intervention was designed using the SAAFE (Supportive, Active, Autonomous, Fair, Enjoyable) framework40 to address students’ basic psychological needs and self-determination41 (the application of the SAAFE framework was presented in Appendix Table 2). The panel designed four exercise modules tailored to integrate seamlessly with regular school PE frameworks. Pilot tests were conducted between May and July 2024 at the same intervention schools that participated in this study. The PE teachers who subsequently delivered the intervention participated in the pilot testing, and their feedback was incorporated to refine the protocol and enhance feasibility and implementation quality. Before implementation, the PE teachers in the intervention group underwent standardized training to ensure fidelity to the protocol. This training was delivered by professors and experts specializing in functional training for children and physical education. The professors first taught the teachers the standard techniques for each exercise, and then trained them in the class procedures and key considerations according to the SAAFE framework. The control group continued their usual PE classes, which were matched in duration (3 × 40 min per week) to the intervention group.

Measurement and outcomes

All outcome assessments were conducted on-site at the participating schools. Physical fitness assessments and physical examinations were performed in the schools’ sports halls. To ensure consistency across groups and measurement time points, questionnaires were administered under standardized protocols in standard computer rooms, where students completed them collectively under supervision. Assessments were conducted at baseline (pre-test) and 16 weeks of follow-up (post-treatment), including:

Physical examinations: height, weight, body mass index, and postural health

Height, weight, and postural health were measured by trained staff using a standardized procedure. Height and weight were measured while students wore light clothing and stood barefoot, with height recorded to the nearest 0.1 cm and weight to the nearest 0.1 kg. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (kg) divided by height (m) squared (kg/m2). The BMI status was classified as thinness, normal weight, or overweight/obesity (OWOB) according to age- and sex-specific Chinese BMI percentiles42.

Postural health was one of the primary outcomes assessed using two indicators: FHP and uneven shoulders. The degree of FHP was measured with participants in a lateral standing position. The landmarks of the seventh cervical vertebra (C7) and the tragus were identified. A horizontal line was drawn parallel to the ground from C7, and the craniovertebral angle (CVA) was measured. The CVA ≥ 50° was considered normal, while < 50° was classified as FHP43. For uneven shoulders, grid paper was affixed to the wall, and participants stood barefoot with their backs to the paper in their habitual standing position. The bilateral acromion points were marked, and a height difference of > 1 cm between shoulders was defined as uneven shoulders44. Additionally, a postural health multimorbidity index (normal, only FHP, only uneven shoulders, FHP & uneven shoulders) was constructed to analyze the intervention’s effectiveness on postural changes over time.

Physical fitness tests

The assessment of PFI was one of the primary outcomes. Physical fitness was measured by standardized tests organized by the education department at the end of each semester, comprising the following components1:

Cardiorespiratory fitness: Forced vital capacity (ml). Children’s forced vital capacity was assessed via spirometry in a quiet setting. Forced vital capacity is defined as the maximum volume of air (measured in milliliters) a child can expel from his or her lungs after a maximum inhalation. The test was repeated three times on each child, and their best performance from the three tests was recorded.

Muscular strength: Sit-ups (reps/min). Children were instructed to perform a 1-minute sit-up test. The protocol required that children lie in a supine position, with their knees bent and feet flat on a floor mat (secured by the test examiner), and their hands placed on the back of the head, fingers crossed. During the performance, children were also instructed to elevate their trunks until their elbows contacted their thighs and then return to the starting position by lowering their shoulder blades to the mat. Children were asked to perform as many sit-ups as possible during the 1-minute test period. The test examiner counted and recorded the number of sit-ups.

Flexibility: Sit-and-reach (cm). Children were seated with both knees fully extended and feet firmly against a vertical support. Children were asked to reach forward with their hands, along a measuring line, as far as possible. Two trials were given to each child, with the score recorded (measured to the nearest 0.1 cm) on the farthest distance reached in the 2 trials.

Speed: 50-m dash (seconds). To assess the 50-m dash, children were instructed to run in a straight line on a flat, clear surface as fast as possible for 50 m. This test was performed once (as a single maximum sprint) for each child, and the time to the finish line was recorded to the nearest 0.1 s.

Coordination: Rope-skipping (counts/min). Children were instructed to perform a rope-skipping task requiring them to take off and land on both feet. After determining the appropriate rope length for each child, the child was asked to jump continuously for 1 min, with the total number of jumps recorded.

Z-scores were calculated for each component by standardizing individual values against the study population’s age- and sex-specific means and standard deviations, using the formula: Z = (X − µ)/σ, where X is the raw value, µ is the mean, and σ is the standard deviation for each parameter within the participant’s age (1-year intervals) and sex stratum. All Z-scores were normalized to a distribution with mean = 0 and SD = 1 before PFI computation. The PFI was calculated using the following formula45: PFI = Z-score of forced vital capacity + Z-score of sit-and-reach + Z-score of sit-ups − Z-score of 50-m dash + Z-score of rope-skipping.

Physical activity: questionnaires

Physical activity was assessed using the Chinese Physical Activity Questionnaire for Children46, which has been specifically validated for use in Chinese children, showing good test-retest reliability (ICC ranging from 0.63 to 0.93) and significant validity for total physical activity and sedentary behavior (Spearman’s rho = 0.32, P < 0.001) against accelerometer measurements. Participants self-reported the frequency (days per week) and duration (minutes per day) of moderate-intensity and vigorous-intensity physical activity. From these responses, the following indicators were derived: moderate-intensity physical activity (MPA; minutes per day), vigorous-intensity physical activity (VPA; minutes per day), moderate-to-vigorous-intensity physical activity (MVPA; minutes per day), and meeting the MVPA recommendation (≥ 60 min per day).

Adherence to programs

Trained members of the research team conducted weekly, unannounced, in-person observations of the sessions using a standardized fidelity checklist. This checklist assessed key components, including adherence to the session structure and the quality of exercise technique coaching.

Adverse events

Adverse events (AEs) were monitored throughout the study and were defined as any issue persisting for more than 2 days or prompting the participant to seek additional treatment. All AEs were systematically recorded and monitored, and the investigator was notified within 24 h of any serious adverse events. Weekly unannounced audits and standardized checklists were used to ensure accurate documentation of AEs, and supplemental teacher training sessions were provided as needed to address any safety concerns. In this study, no AEs were reported.

Blinding

The PE teachers were aware of the group assignments. However, participants, their families, and outcome assessors and statisticians remained blinded to minimize bias.

Statistical analysis

In accordance with the prespecified protocol, the primary outcome analysis was performed in children with available baseline data on both PFI and posture health. All analyses adhered to the intention-to-treat (ITT) principle. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to verify the normality of the data. Descriptive statistics were reported as mean ± SD and percentages (%) for continuous and dichotomous variables, respectively. Baseline differences between groups were examined using independent-samples t-tests or chi-square tests (χ2) for continuous and dichotomous variables, respectively. Missing data, primarily related to PA surveys, were handled via multiple imputation by chained equations (MICE) under the missing-at-random (MAR) assumption. Missing values for days of MPA, VPA, and daily activity duration were imputed using predictive mean matching (PMM). For continuous outcomes, linear mixed-effects models with a difference-in-differences (DID) framework were fitted. Effect sizes were expressed as Cohen’s d with 95% CI, which was calculated as the difference in treatment effects divided by the pooled SD estimated from the mixed model for repeated measures, where values of Cohen’s d < 0.2, 0.2–0.5, and > 0.5 were interpreted as small, medium, and large, respectively47. For the 50-m dash, a negative Cohen’s d value indicates a decrease in sprint time, which corresponds to an improvement in performance. For binary outcomes, generalized linear mixed models (GLMMs) with a Poisson distribution were fitted, and risk ratios (RRs) with 95% CIs were reported. All models were adjusted for sex, age, parental educational attainment, and extracurricular sports participation to account for potential confounding factors. Subgroup analyses (by sex and BMI status) were conducted after confirming the statistical significance (P < 0.05) of these variables as effect modifiers using these models with interaction terms. Sensitivity analyses included a Per-Protocol (PP) analysis (excluding participants with missing data; results were shown in Appendix Tables 6, 7 and 8). Two-sided P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed using R 4.4.2.

Results

Of 1,286 participants (intervention: n = 601; control: n = 685), their baseline characteristics were well-balanced (Table 1), with age (mean ± SD 10.43 ± 0.31 vs. 10.43 ± 0.34 years; P = 0.713), sex (53.1% vs. 53.3% boys; P = 0.940), BMI (mean ± SD 19.28 ± 3.99 vs. 19.51 ± 4.32; P = 0.285), parental educational attainment (≥ 83% bachelor’s degree; P = 0.502 mothers, P = 0.097 fathers), and extracurricular sports participation (74.4% vs. 77.2%; P = 0.230).

Table 2 summarized the within- and between-group changes in primary outcome indicators over 16 weeks. The functional training intervention significantly improved PFI scores compared to regular PE. These effect sizes indicate clinically meaningful differences (mean difference 0.77 [95% CI: 0.48–1.05], Cohen’s d = 0.28, P < 0.001). The improvement effects varied slightly across different measurement items. A significant intervention effect was observed in sit-ups (mean difference 3.89 [95% CI: 2.88–4.91], Cohen’s d = 0.43, P < 0.001), followed by sit-and-reach (mean difference 1.78 [95% CI: 1.25–2.31], Cohen’s d = 0.33, P < 0.001), rope-skipping (mean difference 4.63 [95% CI: 1.23–8.03], Cohen’s d = 0.17, P < 0.001) and BMI (mean difference − 0.30 [95% CI: -0.44–-0.17], Cohen’s d = -0.07, P < 0.001). However, no significant improvement in forced vital capacity was observed (P = 0.725). At the same time, the control group demonstrated better performance in the 50-m dash compared to the intervention group (mean difference 0.15 [95% CI: 0.03–0.28], Cohen’s d = 0.18, P < 0.001) (Table 2; Fig. 3). Subgroup analyses revealed greater improvements in PFI among girls (mean difference 1.43 [95% CI: 1.01–1.84], Cohen’s d = 0.53, P < 0.001) and normal weight group (mean difference 1.31 [95% CI: 0.92–1.70], Cohen’s d = 0.46, P < 0.001), and no significantly improvement was observed in boys (mean difference − 0.19 [95% CI: -0.20–0.57], Cohen’s d = 0.17, P = 0.348), thinness group (mean difference 0.72 [95% CI: -0.60–2.04], Cohen’s d = 0.49, P = 0.287) and OWOB group (mean difference 0.09 [95% CI: -0.36–0.54], Cohen’s d = 0.12, P = 0.703) (Figs. 3, 4 and 5; Appendix Tables 3 and 5).

Postural assessments demonstrated parallel improvements to those in PFI, with the intervention group showing significantly greater reductions in FHP (difference in proportion: -12.6%, P < 0.001; RR = 0.65, 95% CI: 0.54–0.78, P < 0.001) and prevented the worsening of uneven shoulders observed in controls (difference in proportion: -23.3%, P < 0.001; RR = 0.51, 95% CI: 0.42–0.65, P < 0.001). Subgroup analyses revealed significant reductions in FHP among girls (RR = 0.55; 95% CI: 0.39–0.78; P < 0.001) and the normal weight group (RR = 0.50; 95% CI: 0.35–0.70; P < 0.001) compared with controls. Similarly, girls (RR = 0.41; 95% CI: 0.28–0.61; P < 0.001) and the OWOB group (RR = 0.40; 95% CI: 0.26–0.61; P < 0.001) showed greater improvement in uneven shoulders. In contrast, no statistically significant reduction in both FHP and uneven shoulders was observed in the thinness group (Uneven shoulders: RR = 0.49; 95% CI: 0.18–1.30; P = 0.154; FHP: RR = 0.16; 95% CI: 0.02–1.13; P = 0.067) (Fig. 6 & Appendix Tables 4 and 5).

Multimorbidity of FHP and uneven shoulders showed that, compared to the control group, the intervention group increased the prevalence of normal posture from 40.8% to 57.2% (difference in proportion: +24.4%), whereas the control group showed a decrease. The prevalence of combined abnormalities (FHP and uneven shoulders) decreased significantly in the intervention group from 11.7% to 5.7% (difference proportion: 11.6%), whereas it decreased less in the control group. Within the intervention group, FHP demonstrated a larger reduction (difference in proportion: -10.0%), exceeding improvements observed in FHP with multimorbidity and uneven shoulders (within-group difference in proportion: -6.0%) and in isolated uneven shoulders (within-group difference in proportion: -0.5%) (Fig. 6).

The intervention group demonstrated significantly greater improvements in MVPA (mean difference 34.62 [95% CI: 22.04–47.20], P < 0.001; Cohen’s d = 0.47, P < 0.001), with similar patterns for MPA (mean difference 17.25 [95% CI: 10.79–23.72], Cohen’s d = 0.43, P < 0.05) and VPA (mean difference 17.37 [95% CI: 9.54–25.20], Cohen’s d = 0.39, P < 0.001). The proportion failing to meet 60-minute MVPA standards decreased 22.3% in intervention vs. 7.9% in controls (RR = 0.72, 95% CI 0.61–0.85, P < 0.001). Subgroup analyses revealed significant increases in MVPA among boys (mean difference 53.13 [95% CI: 35.98–70.29], Cohen’s d = 0.66, P < 0.001) and the OWOB group (mean difference 39.40 [95% CI: 19.60–59.20], Cohen’s d = 0.24, P < 0.001). By contrast, no significant increases were observed in girls (mean difference 13.53 [95% CI: -4.75–31.81], Cohen’s d = 0.17, P = 0.147) and the thinness group (mean difference − 1.11 [95% CI: -57.71–55.49], Cohen’s d = 0.20, P = 0.969) (Table 2; Fig. 5 and Appendix Table 5). The results of the sensitive analysis (Appendix Tables 6, 7 and 8) were consistent with the primary ITT analysis.

Baseline to post-intervention Z-score changes in physical fitness indicators. PFI stands for physical fitness indicators; Z_SU stands for Z score of sit-ups; Z_RS stands for Z score of rope-skipping; Z_SR stands for 50-m dash; Z_SAR stands for Z score of sit-and-reach; Z_FVC stands for Z score of forced vital capacity.

Flow of postural change transitions between baseline and follow-up. Note: The Sankey diagram illustrates postural state transitions, with band widths proportional to the percentage of participants in each flow path. FHP stands for forward head posture; US stands for uneven shoulders; FHP&US stands for concurrent forward head posture and uneven shoulders; Normal stands for the absence of detectable forward head posture or uneven shoulders.

Discussion

This school-based functional training intervention achieved significant improvements in PFI and postural health among children following the 16-week program. The intervention was found to have potential advantages for enhancing students’ overall PFI (Cohen’s d = 0.28). Significant improvements with small-to-moderate effect sizes were observed in specific components: sit-ups (Cohen’s d = 0.43), sit-and-reach (Cohen’s d = 0.33), and rope-skipping (Cohen’s d = 0.17). In contrast, no significant effect was observed for forced vital capacity (P = 0.725), and the control group demonstrated better performance in the 50-m dash compared to the intervention group (Cohen’s d = 0.18). Postural health improved significantly, with FHP prevalence reduced by 12.6% (RR = 0.65) and uneven shoulders by 23.3% (RR = 0.51). Subgroup analyses revealed critical sex-specific and BMI status patterns. While girls showed particular improvements in PFI (Cohen’s d = 0.53) and postural health (FHP: RR = 0.55; uneven shoulders: RR = 0.41), boys demonstrated significantly greater increases in MVPA (Cohen’s d = 0.66), all with the between-group difference reaching statistical significance. Normal-weight children benefited consistently in PFI (Cohen’s d = 0.46) and uneven shoulders (RR = 0.53), whereas OWOB children showed better improvement in FHP (RR = 0.40) and MVPA (Cohen’s d = 0.24) but limited PFI improvements. These findings substantiate both the feasibility and effectiveness of functional training as a promising, scalable school-based intervention.

The findings were consistent with existing evidence that school-based MSE effectively enhances children’s PFI55,56, demonstrating MSE benefits for children’s physical fitness, particularly muscular strength, flexibility, and coordination32,48. However, the intervention did not achieve statistically significant improvements in cardiorespiratory fitness, likely because enhancements in cardiorespiratory function primarily depend on specialized aerobic training49. While direct comparisons were limited by the paucity of school-based postural intervention studies, the posture outcomes mirror clinical trial evidence demonstrating that functional training effectively improves postural health in children29,50,51.

The intervention demonstrated greater efficacy in improving uneven shoulders than FHP. One hypothesis for this differential effect was that it might have involved distinct biomechanical mechanisms: while uneven shoulders involve neuromuscular coordination across the dynamic lumbar-pelvic-femoral complex (affecting shoulder, spinal, and even lower limb muscle groups)52,53, FHP primarily engages upper body musculature (including cervical paraspinals and pectoralis major)54. However, this remained speculative as these mechanisms were not directly measured in the present study. Furthermore, the pronounced intervention effect on uneven shoulders was accentuated by a marked increase in the prevalence of uneven shoulders within the control group (from 32.4% at baseline to 49.2% at follow-up). This decline in the control group likely reflected natural, age-related trends during a period of rapid growth, when habitual postures and musculoskeletal imbalances would become more entrenched without targeted intervention, which might have been further exacerbated by increased sedentary time and academic pressures throughout the school term12,14,15,55. Sex-specific analyses revealed maximal benefits in girls. One hypothesis for this finding was that MSE might have helped mitigate known sex-related declines in physical self-efficacy by enhancing perceived competence56. Notably, the OWOB group exhibited significantly greater improvements in postural alignment. This effect might have been explained by the hypothesis that children with higher body mass experienced greater training effects, as the prescribed exercises inherently provide greater relative resistance14,57. Furthermore, the intervention demonstrated moderate-to-strong efficacy, with larger effect sizes observed for postural health than for physical fitness. This pattern might have supported the hypothesis that targeted neuromuscular activation yielded more immediate biomechanical adaptations26,29,32, whereas broader fitness gains may require a longer intervention period. These differential effects highlighted a potential strategy for tailored interventions38,49; for example, future programs could incorporate aerobic elements for children with OWOB to amplify fitness outcomes while leveraging their apparent responsiveness in postural improvement. The observed joint improvements in fitness and posture were consistent with the concept that postural training can enhance movement efficiency and force transmission, thereby potentially boosting fitness test performance58.

Furthermore, participants self-reported increased MVPA levels, consistent with previous findings14,59,60. The functional training program, characterized by its emphasis on integrated, multi-joint movements, might have enhanced fundamental movement skills (e.g., dynamic balance, whole-body coordination)29,30,32. This proposed improvement in motor competence could have reduced the perceived barrier to physical activity, making participation more accessible and enjoyable, which, in turn, might have explained the self-reported increase in MVPA. Moreover, a positive feedback loop was postulated, wherein increased MVPA might have synergistically supported gains in physical fitness and postural health. However, as fundamental movement skills were not directly measured, these mechanisms remain speculative and require validation in future studies.

Strengths and limitations

This study offered several notable strengths: First, it provided the first evidence that school-based interventions can effectively improve both postural health and physical fitness in children, addressing a critical gap in current research. Second, the intervention was seamlessly integrated into the existing PE curriculum with minimal disruption, supporting its feasibility and long-term sustainability. Third, functional training was employed as an MSE intervention, demonstrating its safety for children and its practicality in a school setting.

This study had several limitations. First, the primary outcome of MVPA was assessed via self-reported questionnaires, which were susceptible to recall and social desirability biases. This was particularly concerning in a child population, which may overestimate their physical activity levels; future studies should therefore employ objective measures, such as accelerometers, to obtain more accurate data. Second, the lack of a formal process evaluation means that feasibility aspects, such as ease of implementation from the teachers’ perspective and acceptability among both students and teachers, were not assessed. Including these measures in future research would enhance the understanding of intervention scalability and real-world applicability. Third, the absence of long-term follow-up prevents conclusions regarding the sustainability of the intervention effects. Finally, as the functional training intervention was primarily designed to target uneven shoulders, forward head posture, and physical fitness, its potential benefits on other health outcomes remain to be validated.

Conclusion

This study provided promising evidence supporting the effectiveness of functional training in improving children’s physical fitness and postural health. Further studies should evaluate the long-term sustainability of these effects and the generalizability to diverse populations.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available as publications are planned but are available from the corresponding author (yinghuama@bjmu.edu.cn) on reasonable request.

References

Dong, Y. et al. Trends in physical fitness, growth, and nutritional status of Chinese children and adolescents: A retrospective analysis of 1.5 million students from six successive National surveys between 1985 and 2014. Lancet Child. Adolesc. Health. 3, 871–880 (2019).

Lang, J. J. et al. Top 10 international priorities for physical fitness research and surveillance among children and adolescents: A Twin-Panel Delphi study. Sports Med. 53, 549–564 (2023).

Fühner, T., Kliegl, R., Arntz, F., Kriemler, S. & Granacher, U. An update on secular trends in physical fitness of children and adolescents from 1972 to 2015: A systematic review. Sports Med. 51, 303–320 (2021).

Ortega-Gómez, S., Adelantado-Renau, M., Carbonell-Baeza, A. & Moliner-Urdiales, D. Jiménez-Pavón, D. Role of physical activity and health-related fitness on self-confidence and interpersonal relations in 14-year-old adolescents from secondary school settings: DADOS study. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports. 33, 2068–2078 (2023).

Sember, V. et al. Secular trends in skill-related physical fitness among Slovenian children and adolescents from 1983 to 2014. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports. 33, 2323–2339 (2023).

Nuzzo, J. L. The case for retiring flexibility as a major component of physical fitness. Sports Med. 50, 853–870 (2020).

Raghuveer, G. et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness in youth: an important marker of health: a scientific statement from the American heart association. Circulation 142, e101–e118 (2020).

García-Hermoso, A., Ramírez-Campillo, R. & Izquierdo, M. Is muscular fitness associated with future health benefits in children and adolescents? A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Sports Med. 49, 1079–1094 (2019).

Lang, J. J. et al. Systematic review of the relationship between 20m shuttle run performance and health indicators among children and youth. J. Sci. Med. Sport. 21, 383–397 (2018).

Guan, S. Y. et al. Global burden and risk factors of musculoskeletal disorders among adolescents and young adults in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019. Autoimmun. Rev. 22, 103361 (2023).

Chong, K. H. et al. Pooled analysis of physical activity, sedentary behavior, and sleep among children from 33 countries. JAMA Pediatr. 178, 1199–1207 (2024).

Kasović, M., Štefan, L., Piler, P. & Zvonar, M. Longitudinal associations between sport participation and fat mass with body posture in children: A 5-year follow-up from the Czech ELSPAC study. PLoS One. 17, e0266903 (2022).

Bokaee, F. et al. Comparison of isometric force of the craniocervical flexor and extensor muscles between women with and without forward head posture. Cranio 34, 286–290 (2016).

Molina-Garcia, P. et al. Role of physical fitness and functional movement in the body posture of children with overweight/obesity. Gait Posture. 80, 331–338 (2020).

Maciałczyk-Paprocka, K. et al. Prevalence of incorrect body posture in children and adolescents with overweight and obesity. Eur. J. Pediatr. 176, 563–572 (2017).

Sepehri, S., Sheikhhoseini, R., Piri, H. & Sayyadi, P. The effect of various therapeutic exercises on forward head posture, rounded shoulder, and hyperkyphosis among people with upper crossed syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 25, 105 (2024).

Koseki, T., Kakizaki, F., Hayashi, S., Nishida, N. & Itoh, M. Effect of forward head posture on thoracic shape and respiratory function. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 31, 63–68 (2019).

Wen, L. et al. Sagittal imbalance of the spine is associated with poor sitting posture among primary and secondary school students in china: A cross-sectional study. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 23, 98 (2022).

Piercy, K. L. et al. The physical activity guidelines for Americans. JAMA 320, 2020–2028 (2018).

Shiravi, S., Letafatkar, A., Bertozzi, L., Pillastrini, P. & Khaleghi Tazji, M. Efficacy of abdominal control feedback and scapula stabilization exercises in participants with forward Head, round shoulder postures and neck movement impairment. Sports Health. 11, 272–279 (2019).

van Sluijs, E. M. F. et al. Physical activity behaviours in adolescence: current evidence and opportunities for intervention. Lancet 398, 429–442 (2021).

Pereira, H. V. et al. International consensus on the definition of functional training: modified e-Delphi method. J. Sports Sci. 43, 767–775 (2025).

Crawford, D. A., Drake, N. B., Carper, M. J., DeBlauw, J. & Heinrich, K. M. Are changes in physical work capacity induced by High-Intensity functional training related to changes in associated physiologic measures? Sports (Basel). 6, 26 (2018).

Deng, B. et al. Effects of unilateral and bilateral complex-contrast training on lower limb strength and jump performance in collegiate female volleyball players. PLoS One. 20, e0327237 (2025).

Weston, K. L. et al. Effect of novel, school-based high-intensity interval training (HIT) on cardiometabolic health in adolescents: project FFAB (fun fast activity blasts) - an exploratory controlled before-and-after trial. PLoS One. 11, e0159116 (2016).

Gao, Y., Yang, Y., Xian, C. & Wang, Z. Comparative study of functional training and traditional resistance training on lower-limb strength performance in male adolescent volleyball players: a randomized controlled trial. Front. Physiol. 16, 1629055 (2025).

Xiao, W. et al. Effect of functional training on physical fitness among athletes: A systematic review. Front. Physiol. 12, 738878 (2021).

Wan, K., Dai, Z., Wong, P., Ho, R. S. & Tam, B. T. Comparing the effects of integrative neuromuscular training and traditional physical fitness training on physical performance outcomes in young athletes: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. Open. 11, 15 (2025).

van Dillen, L. R. et al. Effect of motor skill training in functional activities vs strength and flexibility exercise on function in people with chronic low back pain: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. 78, 385–395 (2021).

Yildiz, S., Pinar, S. & Gelen, E. Effects of 8-Week functional vs. Traditional training on athletic performance and functional movement on prepubertal tennis players. J. Strength. Cond Res. 33, 651–661 (2019).

Lu, Y., Wiltshire, H. D., Baker, J. S. & Wang, Q. The effects of running compared with functional High-Intensity interval training on body composition and aerobic fitness in female university students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 18, 11312 (2021).

Wang, X. et al. Effects of high-intensity functional training on physical fitness and sport-specific performance among the athletes: A systematic review with meta-analysis. PLoS One. 18, e0295531 (2023).

Leahy, A. A. et al. Feasibility of a school-based physical activity intervention for adolescents with disability. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 7, 120 (2021).

Leahy, A. A. et al. Review of high-intensity interval training for cognitive and mental health in youth. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 52, 2224 (2020).

Kennedy, S. G. et al. Implementing resistance training in secondary schools: A cluster randomized controlled trial. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 50, 62–72 (2018).

Lubans, D. R. et al. Time-efficient intervention to improve older adolescents’ cardiorespiratory fitness: findings from the ‘burn 2 learn’ cluster randomised controlled trial. Br. J. Sports Med. 55, 751–758 (2021).

Fairclough, S. J. et al. Move well, feel good: feasibility and acceptability of a school-based motor competence intervention to promote positive mental health. PLoS One. 19, e0303033 (2024).

Neil-Sztramko, S. E., Caldwell, H. & Dobbins, M. School-based physical activity programs for promoting physical activity and fitness in children and adolescents aged 6 to 18. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 9, CD007651 (2021).

Schmidt, S. A. J., Lo, S. & Hollestein, L. M. Research techniques made simple: sample size Estimation and power calculation. J. Invest. Dermatol. 138, 1678–1682 (2018).

Lubans, D. R. et al. Framework for the design and delivery of organized physical activity sessions for children and adolescents: rationale and description of the ‘SAAFE’ teaching principles. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 14, 24 (2017).

Deci, E. L. & Ryan, R. M. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior (Plenum, 1985).

National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China. Screening for Overweight and Obesity Among School-Age Children and Adolescents (2018).

Abd El-Azeim, A. S., Mahmoud, A. G., Mohamed, M. T. & El-Khateeb, Y. S. Impact of adding scapular stabilization to postural correctional exercises on symptomatic forward head posture: A randomized controlled trial. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil Med. 58, 757–766 (2022).

Xing, Q., Hong, R., Shen, Y. & Shen, Y. Design and validation of depth camera-based static posture assessment system. iScience 26, 107974 (2023).

Cai, S. et al. Secular trends in physical fitness and cardiovascular risks among Chinese college students: an analysis of five successive National surveys between 2000 and 2019. The Lancet Reg. Health – Western Pacific 58 (2025).

Xi, Y. et al. Validity and reliability of Chinese physical activity questionnaire for children aged 10–17 years. BES 32, 647–658 (2019).

Vandekar, S., Tao, R. & Blume, J. A. Robust. Effect Size Index. Psychometrika 85, 232–246 (2020).

García-Hermoso, A., Alonso-Martinez, A. M., Ramírez-Vélez, R. & Izquierdo, M. Effects of exercise intervention on health-related physical fitness and blood pressure in preschool children: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Sports Med. 50, 187–203 (2020).

Oliveira, A., Monteiro, Â., Jácome, C., Afreixo, V. & Marques, A. Effects of group sports on health-related physical fitness of overweight youth: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports. 27, 604–611 (2017).

Ruivo, R. M., Pezarat-Correia, P. & Carita, A. I. Effects of a resistance and stretching training program on forward head and protracted shoulder posture in adolescents. J. Manipulative Physiol. Ther. 40, 1–10 (2017).

Ruivo, R. M., Carita, A. I. & Pezarat-Correia, P. The effects of training and detraining after an 8 month resistance and stretching training program on forward head and protracted shoulder postures in adolescents: randomised controlled study. Man. Ther. 21, 76–82 (2016).

Peng, Y., Wang, S. R., Qiu, G. X., Zhang, J. G. & Zhuang Q.-Y. Research progress on the etiology and pathogenesis of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Chin. Med. J. (Engl). 133, 483–493 (2020).

Bortz, C. et al. The prevalence of hip pathologies in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. J. Orthop. 31, 29–32 (2022).

Sung, Y. H. & Suboccipital Muscles Forward head Posture, and cervicogenic Dizziness. Med. (Kaunas). 58, 1791 (2022).

Calcaterra, V. et al. Childhood obesity and incorrect body posture: impact on physical activity and the therapeutic role of exercise. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 19, 16728 (2022).

Lubans, D. R., Sheaman, C. & Callister, R. Exercise adherence and intervention effects of two school-based resistance training programs for adolescents. Prev. Med. 50, 56–62 (2010).

Molina-Garcia, P. et al. Effects of exercise on body posture, functional movement, and physical fitness in children with overweight/obesity. J. Strength. Cond Res. 34, 2146–2155 (2020).

Poon, E. T. C., Li, H. Y., Gibala, M. J., Wong, S. H. S. & Ho, R. S. T. High-intensity interval training and cardiorespiratory fitness in adults: an umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports. 34, e14652 (2024).

Graham, M., Azevedo, L., Wright, M. & Innerd, A. L. The effectiveness of fundamental movement skill interventions on moderate to vigorous physical activity levels in 5- to 11-year-old children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 52, 1067–1090 (2022).

Dobbins, M., Husson, H., DeCorby, K. & LaRocca, R. L. School-based physical activity programs for promoting physical activity and fitness in children and adolescents aged 6 to 18. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, CD007651 (2013).

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely appreciate all the children, their families, and school teachers who generously participated in this study. Their time and contributions were invaluable to this research.

Funding

This work was supported by Capital’s Funds for Health Improvement and Research (Grant No. 2024-2G-7107 to Ruilan Zhao).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Dr. Ma had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. R-L. Zhao, He, Hu, Ma, Peng, Zhen, and Li contributed to the study conception and design. Data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation were performed by F. Zhu, G-Y. Zhu, Guan, Liu, Yang, Li, and F-F. Zhao. The manuscript was drafted by F. Zhu, Guan, Liu, Yang, R-L. Zhao, He, Hu, and Ma. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content was conducted by F. Zhu, R-L. Zhao, G-Y. Zhu, Liu, Guan, He, Hu, and Ma. Statistical analysis was carried out by F. Zhu, R-L. Zhao, G-Y. Zhu, Liu, Guan, Song, Li, and F-F. Zhao. Administrative, technical, or material support was provided by R-L. Zhao, Peng, Zhen, He, Hu, and Ma. All authors read and approved the final manuscript for publication.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Shunyi District Center for Disease Control and Prevention (Ethics Approval Number: 2024032802) and Peking University (IRB00001052-24182), and written informed consent was obtained from all participants and their parents before allocation. All procedures performed in the present study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committees and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments, or with comparable ethical standards. This trial was registered at the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (ChiCTR-2500104984, 26/06/2025).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu, F., He, Z., Zhu, G. et al. The effect of school-based functional training for physical fitness and postural health among children: a school-based cluster intervention trial. Sci Rep 16, 1535 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31557-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31557-2