Abstract

With the rapid advancements in intelligent transportation systems Jiang et al. (In: In Proceedings of the 30th ACM international conference on information & knowledge management 4515–4525, 2021), (Feng et al. Digit Commun Networks, 2024), precisely forecasting traffic information has emerged as a significant challenge. Recently, numerous advanced neural networks with complex architectures have been introduced to address this challenge. Nonetheless, the majority of these models handle temporal and spatial features separately before combining them, which overlooks the inherent relationships between these two types of characteristics. This approach of independent feature extraction can result in the loss of valuable information and restricts the model’s capacity to effectively leverage the interdependencies between spatial and temporal features. In order to tackle this challenge, we introduce STIC, a Transformer-based neural network designed to capture crucial information from both spatial and temporal domains. The main innovation of our method lies in utilizing the cross-attention mechanism within Transformers to sequentially capture and adaptively merge spatiotemporal features from historical data. Experiments conducted on four diverse traffic forecasting datasets show that our model outperforms traditional methods by effectively uncovering the underlying spatial and temporal dependencies in traffic data sequences. Our work introduces a new strategy for enhancing the accuracy of traffic flow predictions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Traffic forecasting aims to analyze future traffic conditions in a road network by utilizing historical traffic data. Traffic flow data, characterized as spatio-temporal information, consists of multiple interdependent time series. Accurately forecasting traffic flow with computational efficiency serves as a foundational pillar for advancing intelligent mobility networks.Conventional analytical and modeling techniques face several constraints, making accurate forecasting a complex task. Recently, deep learning-based traffic prediction models have demonstrated significant advancements, largely due to their ability to capture the inherent spatio-temporal correlations within traffic systems.

Notably, Transformer-based models like those presented in 3,4 and spatio-temporal graph neural networks (STGNNs) 5,6 have achieved remarkable success, making them highly popular approaches in this domain. The Transformer-based models leverage the multi-head attention mechanism to efficiently establish spatial and temporal relationships, enabling it to handle lengthy sequences. In the mean time, the STGNNs integrate graph convolution networks with sequential models to capture temporal patterns while addressing non-Euclidean dependencies among variables.

Beyond these approaches, a variety of complex and cutting-edge models have been introduced for predicting traffic flow, such as those featuring efficient attention mechanisms 7,8,9,10,11, learning graph structure models 12,13,14,15,16, graph convolution models 17,18,19,20,21,22, and other methods 23,24,25. However, despite the progress in network architecture, performance gains have plateaued, primarily due to the oversight of the inherent correlations between temporal and spatial features in previous research.

Framework is very important in many researches26,27. Inspired by the Transformer framework 28, particularly the interaction between its encoder and decoder, we employ the cross-attention mechanism to seamlessly combine temporal and spatial features.

Effective data representation plays a vital role in traffic forecasting. A key element of STGNNs is the feature embedding \(E_f\), which is used to map raw inputs into a high-dimensional latent space, capturing spatio-temporal patterns efficiently. However, attention mechanisms alone are not sufficient to retain positional information from time series. Therefore, additional structures like temporal position encoding \(E_{tpe}\) and periodic embeddings \(E_{p}\) are required. Recent advancements have led to the development of models such as GMAN 3, PDFormer 4, STID 29, and STAEformer 30, each incorporating spatial embedding \(E_{S}\) to improve the capture of spatial features. Notably, STID 29 introduces an innovative embedding approach that combines both spatial and temporal periodic embeddings, achieving significant performance gains with a simple Multi-layer Perceptron (MLP). Additionally, STAEformer 30 presents an adaptive embedding layer, which uses adaptive embedding \(E_{a}\) to effectively learn both temporal and spatial patterns.

We propose a novel enhanced periodic embedding \(E_{plus}\) to further improve the effectiveness of feature representation. It comprehensively integrates periodic information, thereby strengthening the representation of periodic patterns in historical data.

The key contributions of this paper can be outlined as follows:

-

We introduce a new model called STICformer that features a cross-attention layer. This layer integrates temporal and spatial and temporal information through the application of cross-attention mechanisms.

-

We introduce a new embedding layer structure, \(E_{plus}\), to further enhance the representation of periodic information in historical data.

The paper is organized as follows: Section 2 provides an overview of related research, fundamental concepts, and the problem definition. Section 3 offers a comprehensive description of the model. Section 4 includes an in-depth assessment of the model’s effectiveness, featuring predictive visualizations and detailed ablation studies across different architectures and key components. Lastly, Section 5 summarizes the findings and concludes the paper.

Related work

Previous studies

In recent years, Transformer-based models have garnered significant attention in the field of traffic flow prediction due to their ability to effectively capture both temporal and spatial dependencies. We proposed TSformer in the conference ICA3PP 31, a Temporal-Spatial Transformer model specifically designed for traffic prediction. TSformer addresses the challenges of modeling spatio-temporal intersections by introducing a novel attention mechanism that integrates spatial and temporal features in a sequential manner, first focusing on temporal features and then on spatial features. This approach effectively captures the intrinsic connections of spatio-temporal information.

However, the sequential order of feature extraction (temporal-first followed by spatial) may impact the prediction performance. Building on this, we extend TSformer and propose an improved method, STICformer (Spatio-Temporal Intrinsic Connections Transformer), which explicitly considers the influence of the extraction order on the results. To address this, we design two dedicated modules, the Temporal-first Cross-Attention Layer and the Spatial-first Cross-Attention Layer, to adaptively model the spatio-temporal dependencies in different orders. Taking into account the impact of the extraction sequence, our approach achieves superior performance in traffic flow prediction.

Spatial–temporal prediction models

Deep learning has made significant advancements in numerous domains, including autonomous driving and speech recognition, and it has also excelled in the prediction of spatio-temporal data. Researchers have created models that capture the inherent spatio-temporal relationships in traffic data by portraying such data as time series across a road network. In this network, roads are interconnected according to their geographical closeness. Traditional RNNs 32,33 and their variations 34 have been widely used to learn sequential patterns. However, these models often treat traffic data from different roads as independent streams, overlooking the hidden relationships between them. To overcome this limitation, researchers have integrated RNNs with GCNs or CNNs to enhance traffic forecasting. For example, some models use GCN outputs as features for GRUs 6,34, while others combine CNNs with GCNs for effective short-term forecasting 14,16. Despite these advancements, such methods often excel at capturing local patterns but struggle with long-term predictions.

Attention mechanism

The Attention Mechanism 28 has become widely adopted across different domains owing to its effectiveness and versatility in identifying dependencies. Its primary concept revolves around dynamically concentrating on the most pertinent features dictated by the input information.

In recent years, researchers have refined this mechanism to tackle the complex problem of traffic forecasting. PDFormer 4 utilizes two graph masking matrices to implement a spatial self-attention layer, which captures dynamic spatial relationships in the data. GMAN 3 employs a decoder-encoder structure, using separate attention layers to process dynamic spatial dependencies and non-linear temporal correlations in the data. STAEformer 30 sequentially captures both temporal and spatial dependencies by concatenating multiple layers of self-attention mechanisms.

We utilize the cross-attention mechanism to capture the inherent temporal-spatial interactions, which allows for improved integration of both temporal and spatial features. Additionally, drawing inspiration from COTattention ?, we incorporate convolutional layers into the temporal-spatial cross-attention block to better capture feature characteristics, thereby enhancing the fusion of temporal and spatial information.

Traffic forecasting

Over the past few decades, traffic forecasting has garnered significant research attention. For example, DCRNN 6 models traffic flow dynamics through a diffusion process and employs a diffusion convolution operation to effectively capture spatial relationships. On the other hand, STGCN 5, which adopts a purely convolutional architecture, decreases the parameter count, resulting in accelerated training times. The AGCRN model 34 addresses the unique traffic patterns observed at each node by assigning distinct parameters, such as biases and weights, to every individual node. This approach allows for a more effective capture of the specific behaviors of each observation point, improving the model’s ability to reflect node-specific characteristics.HI 35 focuses on historical inertia, leveraging the persistence and continuity of past data to enhance future forecasting.

There are also some models that do not rely on graph structures, such as STID 29, which introduces spatial embeddings and temporal periodic embeddings, and STAEformer 30, which builds upon this by incorporating adaptive spatio-temporal embedding layers. Both achieve superior performance with simple network structures. Similarly, our model introduces a cross-attention mechanism to capture complex spatio-temporal dependencies without relying on graph structures.

Methodology

We observe that spatio-temporal features are inherently integrated. For instance, traffic units on a road at a specific time tend to appear at particular observation points, indicating an intrinsic connection between temporal nodes and observation points. To better extract spatio-temporal features as a whole, rather than extracting them independently and then fusing them, we propose the concept of cross-attention spatio-temporal fusion. Meanwhile, to enhance the efficiency of pre-training, we employ feature extraction blocks to capture temporal features effectively.

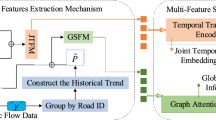

As depicted in Fig. 1, the architecture of our model comprises three essential components: an embedding layer, cross-attention mechanisms, and a fusion regression module.At the outset, the embedding layer maps the input data into a latent space of high dimensionality. Following this, the time-first and space-first cross-attention layers refine the spatio-temporal representations. Finally, the fusion regression module processes the extracted features to produce the final prediction.

Problem definition

The primary goal of traffic prediction is to estimate future traffic conditions in transportation networks using historical data. Specifically, the data \(Y_{t-T+1:t}\) encodes traffic patterns from the preceding \(T\) time intervals. The task is to forecast traffic states for the next \(T'\) time intervals by training a model \(G(\cdot )\) with parameters \(\Phi\), formulated as:

At each time step, the traffic data \(Y_i \in \mathbb {R}^{M \times p}\), where \(M\) represents the count of spatial units and \(p\) denotes the feature size. Here, \(p = 1\), indicating the traffic volume.

Embedding layer

The input data processed by the embedding layer is denoted as \(X \in \mathbb {R}^{T \times N \times D}\), where T represents the number of temporal nodes, N denotes the total number of observation points, and D is the number of dimensions. In our study, the embedding layer is divided into five main components: (1) the feature embedding layer \(E_f\), (2) the adaptive embedding layer \(E_a\), (3) the spatial embedding layer \(E_s\), (4) the periodic embedding layer \(E_p\), and (5) the proposed periodic enhancement embedding layer \(E_{\text {plus}}\).

To preserve the original data’s integrity, we employ a fully connected layer 36 to compute the feature embedding \(E_f \in \mathbb {R}^{T \times N \times d_f}\). This is expressed as:

where \(d_f\) represents the feature embedding’s dimensionality, and \(\text {Dense}(\cdot )\) denotes the fully connected layer.

Following the method proposed in STID 29, we utilize the spatial embedding layer \(E_s \in \mathbb {R}^{T \times N \times d_s}\) to capture spatial information, where \(d_s\) is the dimensionality of the spatial embedding.

The periodic embedding layer, denoted as \(E_p\), captures both weekday and timestamp information from the historical data. This embedding layer is influenced by two key components: \(T_d\), which represents weekday-related data, and \(T_w\), which holds information about the timestamps. These two components have demonstrated their effectiveness in previous works 29,30. Specifically, \(T_d\) is a matrix of size \(N_d \times d_f\), where \(N_d\) represents the total number of distinct timestamps within a single day, which is 288. On the other hand, \(T_w\) is a matrix of size \(N_w \times d_f\), where \(N_w\) corresponds to the number of days in a week, which is 7.

To further capture the periodicity of historical data, we propose a periodic enhancement embedding layer \(E_{\text {plus}} \in \mathbb {R}^{T \times N \times d_p}\). The indices of \(E_{\text {plus}}\) are represented by \(T_D \in \mathbb {R}^{N_p \times d_p}\), where \(N_p\) is defined as:

This design combines the weekday information and daily timestamp information from historical data to extract latent periodic features.

Drawing inspiration from the adaptive embedding strategy presented in STAEformer 30, We define \(E_a \in \mathbb {R}^{T \times N \times d_a}\) as a tensor designed to model the complex relationships within the traffic data. A key feature of \(E_a\) is its adaptability across various traffic time series, allowing it to generalize to different patterns of traffic flow over time and space.

By combining the embeddings mentioned earlier, we construct the spatio-temporal representation for the hidden layer, denoted by \(Z \in \mathbb {R}^{T \times N \times d_h}\), which can be formulated as:

where \(\parallel\) denotes the concatenation operation. This framework is designed to capture periodic behaviors and spatio-temporal patterns by leveraging diverse embedding layers, thereby improving the model’s ability to interpret and process spatio-temporal sequential data.

Temporal/spatial-first cross-attention layer

To capture intricate traffic dynamics, we employ a standard Transformer model across both temporal and spatial dimensions. As shown in Fig. 1, our approach leverages both temporal-first and spatial-first attention modules to integrate spatio-temporal features from historical data. For instance, in the temporal-first cross-attention layer (displayed on the left in Figure 1), The data fed into the system comes directly from the embedding layer, symbolized as \(Z \in \mathbb {R}^{T \times N \times d_h}\). Here, T corresponds to the sequence length (time steps), and N indicates the count of spatial nodes.In the initial processing stage, the temporal self-attention mechanism computes three matrices: the query matrix \(Q\), the key matrix \(K\), and the value matrix \(V\).

where \(W_Q, W_K, W_V \in \mathbb {R}^{d_h \times d_h}\) are trainable parameters. The self-attention weights are computed as:

\(A \in \mathbb {R}^{N \times T \times T}\) captures the temporal dependencies across different nodes. Finally, the output from the temporal self-attention layer is:

As illustrated by the attention visualizations in Fig. 2, we combine the output \(Z_{\text {FB}}\) from feature extraction with the input \(Z\) and apply cross-attention along the spatial axis to capture spatio-temporal relationships.

The query matrix \(Z_{\text {FB}}\) is generated by passing \(Z\) through the feature extraction module, detailed in Section 3.3.

The learning process is formulated as follows:

The index of the cross-attention sub-layer is represented by n.

Finally, the output of the spatio-temporal cross-attention layer is fed through a feedforward propagation and normalization process to obtain the final output of the temporal-first cross-attention layer \(Z_t\):

\(\text {LN}(\cdot )\) denotes the normalization layer, and \(\text {FFN}(\cdot )\) denotes the feedforward regression layer.

The spatial-first cross-attention layer follows the same process as described above, and its output is denoted as \(Z_s\).

For the spatial-first cross-attention layer, the embedded input

is first rearranged along the spatial axis, yielding

so that each spatial node corresponds to a sequence of length \(T\).

The multi-head attention mechanism then performs spatial self-attention as follows:

where \(W_Q, W_K, W_V \in \mathbb {R}^{d_h \times d_h}\) are trainable parameters with the same form as in the temporal-first module. The attention weights along the spatial dimension are computed as:

where \(A' \in \mathbb {R}^{T \times N \times N}\) captures spatial dependencies among nodes for each time step. The output of the spatial self-attention layer is:

Next, consistent with the temporal-first structure, the output from the feature extraction module \(Z_{\text {FB}}\) is integrated through cross-attention along the temporal axis:

Finally, the spatial-first cross-attention layer output is obtained by applying feedforward propagation and normalization:

This supplement explicitly distinguishes the two modules: the temporal-first module first aggregates temporal dependencies and then performs spatial cross-attention, while the spatial-first module first aggregates spatial dependencies and then performs temporal cross-attention.

Temporal-First and Spatial-First Attention Heatmaps for selected PEMS08 nodes and time steps. Left: temporal-first module (rows: nodes, columns: time steps). Right: spatial-first module (rows: time steps, columns: nodes). Darker colors indicate higher attention weights. The visualizations reveal temporal synchronization among nodes and spatial coupling patterns, demonstrating the model’s ability to capture meaningful spatio-temporal dependencies.

Analysis and Innovation Points:

The combined heatmap provides a clear view of how the model captures spatio-temporal dependencies:

-

Temporal-first module highlights temporal correlations and assigns higher attention to key nodes during peak hours and anomalies.

-

Spatial-first module reveals spatial coupling among nodes and the propagation of local traffic anomalies.

-

Together, these modules illustrate our key innovation: efficient modeling of complex spatio-temporal traffic dynamics, improving prediction accuracy and interpretability.

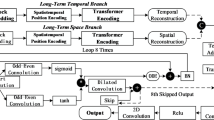

Feature pre-extraction block (FB)

Figure 3 presents the layout of our feature extraction module, which is organized into three main branches: Key Encoding, Value Encoding, and Attention Encoding. The Key Encoding branch applies a \(3 \times 3\) convolutional filter, denoted by \(\text {Conv}_3 \in \mathbb {R}^{3 \times 3}\), followed by a Batch Normalization operation and a ReLU activation function to enhance the feature maps. The Value Encoding branch uses a pointwise convolution filter \(\text {Conv}_1 \in \mathbb {R}^{1 \times 1}\) in tandem with Batch Normalization to extract and standardize key features. The Attention Encoding segment consists of two consecutive \(1 \times 1\) convolutional layers (each \(\text {Conv}_1 \in \mathbb {R}^{1 \times 1}\)), and the output is then normalized via Batch Normalization and activated using a ReLU function, which together capture complex inter-feature dependencies.

The FB module is designed to enhance the quality of feature representations before they are passed into the cross-attention mechanism. Its three branches—Key Encoding, Value Encoding, and Attention Encoding—serve complementary purposes.

First, the Key Encoding branch refines the structural patterns contained in \(K\), enabling the model to highlight node-specific temporal or spatial structures that are important for attention matching. Second, the Value Encoding branch enriches the semantic information in \(V\), allowing the subsequent weighted aggregation to capture more informative spatio-temporal features. Third, the Attention Encoding branch operates on the joint representation \(Y'=\text {Concat}(K_1, Q)\) to learn an adaptive attention distribution that reflects the interaction strength between query and key features.

This design provides a hierarchical enhancement of keys, values, and attention patterns, which strengthens the expressiveness of the cross-attention module. Compared with convolution-based attention mechanisms (e.g.,37), the FB module plays a similar role in enriching local dependencies, but it does so through feature-level encoding rather than explicit convolutional operations. As a result, the FB module improves spatio-temporal feature extraction while maintaining compatibility with the Transformer-based attention structure.

This hierarchical structure enables efficient feature extraction while preserving spatial and temporal dependencies.

Figure 1 presents the process in which the temporal-first cross-attention mechanism operates. First, the input \(Z^{(\text {te})}\) is assigned to the variables \(K\), \(Q\), and \(V\). To initiate the process, the **Key Encoding** is performed on \(K\), producing the key feature matrix \(K_1\). Similarly, the **Value Encoding** transforms \(V\) into the value feature matrix \(V'\), which will be used in subsequent attention calculations:

After these encodings, the next step involves combining \(K_1\) with \(Q\) along the feature axis to form the matrix \(Y'\). The resulting \(Y'\) then undergoes **Attention Encoding**, producing the attention distribution \(\text {Att}\). This attention map is utilized in a dot product with \(V'\), resulting in the weighted feature matrix \(K_2\):

Finally, the two matrices \(K_1\) and \(K_2\) are combined element-wise, yielding the final feature map \(Z_{\text {FB}}\):

Fusion regression layer

To effectively capture the latent correlations between temporal and spatial information in historical data, we again make use of the cross-attention mechanism. The results from both the temporal and spatial attention layers, \(Z_t\) and \(Z_s\), are passed into the fusion regression layer to derive the spatio-temporal feature tensor \(Z_{ts}\):

Finally, to generate the predictions, the output of the cross-attention layer, \(Z_{ts} \in \mathbb {R}^{T \times N \times d_h}\), is fed through the regression layer, with the complete process represented as follows:

The predicted output is denoted as \(\hat{Y} \in \mathbb {R}^{T' \times N \times d_h}\), where \(T'\) is the forecast horizon, and \(d_h\) refers to the output feature dimensions, which are set to 1 in our model implementation. As a result, the regression layer maps the tensor \(Z_{ts}\), which has a size of \(T \times N\), to \(\hat{Y}\), with the dimensions reduced to \(T' \times 1\). The detailed steps of the STIC model are outlined in Algorithm 1. In this context, the input and output of the model are represented by X and Y, respectively. Here, K indicates the number of training epochs, Z is the feature map generated by the embedding layer, while \(Z_{fb1}\) and \(Z_{fb2}\) correspond to the outcomes of self-attention operations conducted along the time and spatial axes. Finally, \(Z_t\) and \(Z_s\) represent the outputs from the temporal and spatial cross-attention modules, respectively.

Experiments

Experimental setup

Datasets & metrics

We conducted experiments on six traffic prediction benchmark datasets, namely METR-LA, PEMS-BAY, PEMS03, PEMS04, PEMS07, and PEMS08. The first two datasets were introduced by DCRNN 6 , and the latter four by STSGCN 8 proposed. The time sampling interval of these six datasets is 5 minutes, thus there are 12 time points per hour. For more details, refer to Table 1

In line with previous studies, we opted to assess the average performance across 12 forecasted time steps for the PEMS03, PEMS04, PEMS07, and PEMS08 datasets. For evaluating the METR-LA and PEMS-BAY datasets, we examined the performance at time horizons of 3, 6, and 12 steps, corresponding to 15, 30, and 60 minutes, respectively. To assess model performance, we evaluate model performance using three widely adopted metrics in traffic prediction tasks: Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), Mean Absolute Error (MAE), and Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE), defined as follows:

where \(a_j\) represents the actual value, \(\hat{a}_j\) is the predicted value, and \(M\) is the total number of samples.

Model implementation

Our model is implemented using the PyTorch framework on a Windows-based server equipped with a GeForce RTX 4070 Ti GPU. For the experimental setup, we use four traffic datasets: PEMS-03, PEMS-04, PEMS-07, and PEMS-08. These datasets are split into training, validation, and test sets in a ratio of 60%, 20%, and 20%, respectively.

The auxiliary embedding dimension, \(d_a\), is set to 84, while the primary feature dimension, \(d\), is configured to 24. The model architecture includes two layers for both the temporal self-attention and temporal-spatial cross-attention modules, and three layers for the spatial self-attention module. Each attention module uses four attention heads. Both the input and forecast sequences represent one-hour time spans, which consist of twelve time steps.

To train the model, we use the Adam optimizer with an initial learning rate of 0.001, which decays during the optimization process.

Baselines

In this study, we compared our proposed approach with several widely recognized baseline models that are commonly used in traffic forecasting. The HI model 35 represents a traditional method. In addition to STGNN-based models like GWNet 16, Cy2Mixer 38, STPGNN 39, DCRNN 6, AGCRN 34, STGCN 5, GTS 15, and MTGNN 14, we also examine STNorm 40, which focuses on decomposing traffic time series. Although Transformer-based time series models like Informer, Pyraformer, FEDformer, and Autoformer are available, these are not specifically designed for short-term traffic forecasting. Therefore, we selected GMAN 3 and PDFormer 4, both Transformer-based models designed for this task. Additionally, we included STID, STAEformer, and Tsformer 31, which avoid using adjacency matrices and instead focus on enhancing embedding layers, with relatively simpler model architectures. As shown in Table 3, our method outperforms most of these models across all six datasets on various evaluation metrics.

Attention weight analysis

To validate how STICformer captures spatio-temporal dependencies, we analyze the statistical properties of attention weights in both temporal-first and spatial-first cross-attention layers using the PEMS08 dataset.

For the temporal-first layer, we compute the average attention weight across all time steps and spatial nodes, finding it to be 0.28 with a maximum value of 0.82. This indicates that, on average, each time step attends moderately to past states, but occasionally focuses strongly on immediate predecessors (e.g., \(t-1\) to t), aligning with the intuition that traffic flow exhibits short-term temporal correlations.

In the spatial-first layer, the average attention weight is 0.31 with a maximum of 0.89. This higher average and peak value suggest that spatial dependencies are more pronounced, with each spatial node attending strongly to its adjacent neighbors (e.g., sensors 105 and 109 on PEMS08). These findings confirm that the cross-attention mechanism effectively adapts to the intrinsic characteristics of traffic data, prioritizing critical temporal and spatial relationships.

Performance evaluation

We evaluate STICformer alongside 14 state-of-the-art baselines, including both traditional and recent deep learning models, on the widely used METR-LA and PEMS-BAY traffic forecasting datasets. These datasets represent urban traffic networks with different scales and sparsity levels, making them ideal for evaluating generalization capability. Table 2 presents the quantitative results across three prediction horizons: 3 (15 minutes), 6 (30 minutes), and 12 (60 minutes), measured by MAE, RMSE, and MAPE. Our proposed STICformer consistently achieves the best performance across all metrics and horizons, demonstrating its superior capability in modeling complex spatio-temporal dependencies. Particularly, STICformer outperforms the second-best model by notable margins, with up to 0.02 lower MAE, 0.07 lower RMSE, and 0.05% lower MAPE on key horizons.

As presented in Table 3, our proposed model, STICformer, outperforms existing methods across various metrics on the four datasets (PEMS03, PEMS04, PEMS07, and PEMS08) achieving state-of-the-art results. Notably, STICformer outperforms its predecessor, TSformer, which uses a sequential order of feature extraction (temporal-first followed by spatial). This indicates that explicitly considering the impact of the extraction order on spatio-temporal dependencies is crucial for improving prediction accuracy.

Furthermore, STICformer achieves competitive or superior results without relying on explicit graph modeling, a common requirement in many STGNNs such as AGCRN, GWNet, and DCRNN. For example, on PEMS07, STICformer achieves an MAE of 19.10, outperforming AGCRN (20.57) and DCRNN (21.16), while maintaining simplicity in its architecture by not requiring predefined graph structures.

Compared to graph-free models like STID and TSformer, STICformer achieves further improvement by addressing the limitations of feature extraction sequence. The incorporation of adaptive cross-attention layers enables STICformer to better integrate temporal and spatial information dynamically, leading to consistent improvements across datasets. On PEMS03, STICformer achieves the lowest RMSE (25.20) and a competitive MAPE (14.34%) underscoring its robustness and generalizability across varying data distributions.

In conclusion, the findings indicate that STICformer significantly improves spatio-temporal modeling by tackling the impact of extraction sequence. When compared to state-of-the-art methods, it demonstrates superior performance in predicting traffic flow. These enhancements validate the design of the two specialized cross-attention layers and highlight the importance of adaptively capturing spatio-temporal dependencies in varying sequences.

Ablation study

To evaluate the effectiveness of each component in TSformer, we conduct an ablation study, which includes four variants of our model:

-

w/o \(E_{\text {plus}}\): Removal of the embedding layer of periodic enhancement.

-

w/o T: Removal of the temporal cross-attention layer.

-

w/o S: Removing the spatial cross-attention layer.

-

w/o C: Removing the cross-attention layer and replacing it with a self-attention layer.

-

w/o TS: Removing both the temporal and spatial cross-attention layers.

-

STICformer: The complete model.

As shown in Table 4, we evaluate the impact of different modules on the model’s performance.

The results of the analysis reveal that removing either the temporal-first or spatial-first cross-attention layer leads to performance degradation, but the extent of the decline is not consistent. Specifically, the removal of the temporal cross-attention layer causes a more significant drop in performance on the PEMS03 dataset, whereas omitting the spatial cross-attention layer has a larger effect on the PEMS08 dataset. This discrepancy can be attributed to the varying distribution of spatio-temporal features across datasets. The model is able to more effectively capture the relationships between these features, which helps it handle non-uniformities in the data. These findings further support the validity of the STIC structural design.

Moreover, to further verify the model’s structural soundness, we replace the cross-attention layers in the model with self-attention layers. The results show a significant performance degradation, indicating that spatio-temporal data indeed have specific interdependencies across different dimensions. The cross-attention mechanism is better suited to capturing these dependencies, enhancing the model’s overall effectiveness.

Visualization of prediction results

In this study, we further validate the rationale of our model by comparing it visually with the high-performance model STID29 on the PEMS08 dataset. We concatenate the model predictions with the actual data in batches to enable a more comprehensive analysis of the model’s predictive performance. As shown in Fig. 4, the STIC model is closer to the true values at most time points, demonstrating higher prediction accuracy compared to STID, which indicates that STIC has a significant advantage in capturing the temporal features of the data. Moreover, the STIC model exhibits less fluctuation in its predictions, remaining smoother than the more volatile predictions from STID, suggesting that it is more robust in terms of data smoothing. This characteristic makes it more suitable for real-world applications where data stability is crucial.

More importantly, despite some prediction errors, the STIC model performs excellently in following the overall trend, especially in regions with large fluctuations, where it can more accurately reflect the change trend of the real data. In contrast, STID is somewhat lacking in trend tracking ability, further validating the superiority of the STIC model in handling temporal data.

In addition to prediction accuracy, we also compare the model complexity and computational efficiency of STICformer with recent graph-based spatio-temporal Transformer models, including STAEformer and STID, on the PEMS08 dataset. Table 5 summarizes the relative comparison in terms of parameter counts and training/inference efficiency. As shown, STICformer maintains a competitive model size while demonstrating faster training and inference speed compared to STAEformer and STID. These results indicate that STICformer achieves improved predictive performance without introducing significant computational overhead, highlighting its practical advantage for real-world traffic forecasting applications where both accuracy and efficiency are important.

Summary and conclusions

Through the integration of a temporal–spatial cross-attention fusion mechanism, we have successfully advanced traffic forecasting. Our study showcases significant improvements in handling intricate spatio-temporal dynamics, addressing the limitations of conventional neural network approaches. The experimental results indicate that our model outperforms existing techniques across four traffic prediction benchmarks, underscoring its superior capability to model complex temporal and spatial interdependencies. This innovative method provides a robust solution to the challenges of traffic prediction, delivering highly satisfactory performance in our experimental evaluations.

Despite these promising results, it is important to acknowledge that benchmark datasets are typically well-curated and preprocessed. In real-world traffic prediction scenarios, data can be affected by unexpected events such as accidents and traffic control, as well as sensor failures and communication noise, which often introduce unknown anomalies and substantial noise. The robustness of the proposed model, including STICformer, under such noisy and unpredictable conditions has not yet been fully examined. In future work, we plan to investigate how to enhance the model’s resilience to unknown disturbances and noise, which we believe is a valuable and meaningful research direction for improving the practicality and reliability of traffic forecasting systems.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to institutional restrictions but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Jiang, R. et al. Dl-traff: Survey and benchmark of deep learning models for urban traffic prediction. In: Proceedings of the 30th ACM International Conference on Information & Knowledge Management 4515–4525 (2021).

Feng, D., Lai, J., Wei, W. & Hao, B. A novel deviation measurement for scheduled intelligent transportation system via comparative spatial-temporal path networks. Digit Commun Netw. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcan.2024.04.002 (2024).

Zheng, C., Fan, X., Wang, C. & Qi, J. Gman: A graph multi-attention network for traffic prediction. In: Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 34, 1234–1241 (2020).

Jiang, J., Han, C., Zhao, W. X., Wang, J (Propagation delay-aware dynamic long-range transformer for traffic flow prediction. In: AAAI, Pdformer, 2023).

Yu, B., Yin, H. & Zhu, Z. Spatio-temporal graph convolutional networks: A deep learning framework for traffic forecasting. In: Proceedings of the 27th International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence 3634–3640 (2018).

Li, Y., Yu, R., Shahabi, C. & Liu, Y. Diffusion convolutional recurrent neural network: Data-driven traffic forecasting. In: International Conference on Learning Representations (2018).

Zhou, T. et al. Fedformer: Frequency enhanced decomposed transformer for long-term series forecasting. In: International Conference on Machine Learning, PMLR 27268–27286 (2022).

Zhou, H. et al. Informer: Beyond efficient transformer for long sequence time-series forecasting. In: Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 35, 11106–11115 (2021).

Liu, S. et al. Pyraformer: Low-complexity pyramidal attention for long-range time series modeling and forecasting. In: International Conference on Learning Representations (2021).

Wu, H., Xu, J., Wang, J. & Long, M. Autoformer: Decomposition transformers with auto-correlation for long-term series forecasting. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst 34, 22419–22430 (2021).

Cirstea, R.-G., Yang, B., Guo, C., Kieu, T. & Pan, S. Towards spatio-temporal aware traffic time series forecasting–full version. arXiv preprint arXiv:2203.15737 (2022).

Zhang, Q., Chang, J., Meng, G., Xiang, S. & Pan, C. Spatio-temporal graph structure learning for traffic forecasting. In: Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 34, 1177–1185 (2020).

Jiang, R. et al. Spatio-temporal meta-graph learning for traffic forecasting. In: Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 37, 8078–8086 (2023).

Wu, Z. et al. Connecting the dots: Multivariate time series forecasting with graph neural networks. In: Proceedings of the 26th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining 753–763 (2020).

Shang, C., Chen, J. & Bi, J. Discrete graph structure learning for forecasting multiple time series. In: International Conference on Learning Representations (2021).

Wu, Z., Pan, S., Long, G., Jiang, J. & Zhang, C. Graph wavenet for deep spatial-temporal graph modeling. In: Proceedings of the 28th International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence 1907–1913 (2019).

Chen, Z., Zhu, B. & Zhou, C. Container cluster placement in edge computing based on reinforcement learning incorporating graph convolutional networks scheme. Digit Commun Netw 11, 60–70 (2025).

Sarhan, M., Layeghy, S., Moustafa, N., Gallagher, M. & Portmann, M. Feature extraction for machine learning-based intrusion detection in IoT networks. Digit Commun Netw 10, 205–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcan.2022.08.012 (2024).

Song, C., Lin, Y., Guo, S. & Wan, H. Spatial-temporal synchronous graph convolutional networks: A new framework for spatial-temporal network data forecasting. In: Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 34, 914–921 (2020).

Wang, X. et al. Traffic flow prediction via spatial temporal graph neural network. In: Proceedings of the Web Conference 2020, 1082–1092 (2020).

Xiao, Y. et al. Afstgcn: Prediction for multivariate time series using an adaptive fused spatial-temporal graph convolutional network. Digit Commun Netw 10, 292–303 (2024).

Dong, C. et al. Evaluating impact of remote-access cyber-attack on lane changes for connected automated vehicles. Digit Commun Netw 10, 1480–1492. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcan.2023.06.004 (2024).

Pan, Z. et al. Autostg: Neural architecture search for predictions of spatio-temporal graph. In: Proceedings of the Web Conference 2021, 1846–1855 (2021).

Lee, H., Jin, S., Chu, H., Lim, H. & Ko, S. Learning to remember patterns: Pattern matching memory networks for traffic forecasting. In: International Conference on Learning Representations (2022).

Cirstea, R.-G., Kieu, T., Guo, C., Yang, B. & Pan, S. J. Enhancenet: Plugin neural networks for enhancing correlated time series forecasting. In: 2021 IEEE 37th International Conference on Data Engineering (ICDE) 1739–1750 (2021).

Meng, Q. et al. Detection of unknown attacks through encrypted traffic: A gaussian prototype-aided variational autoencoder framework. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 20, 10652–10667 (2025).

Meng, Q. et al. When unknown threat meets label noise: A self-correcting framework. IEEE Trans. Dependable Secure Comput. https://doi.org/10.1109/TDSC.2025.3611908 (2024).

Vaswani, A., Shazeer, N., Parmar, N. & et al. Attention is all you need. In Proceedings of 31st Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS) (2017).

Shao, Z., Zhang, Z., Wang, F., Wei, W. & Xu, Y. Spatial-temporal identity: A simple yet effective baseline for multivariate time series forecasting. In Proceedings of the 31st ACM International Conference on Information & Knowledge Management 4454–4458 (2022).

Liu, H. et al. Spatio-temporal adaptive embedding makes vanilla transformer sota for traffic forecasting. In Proceedings of the 32nd ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management (CIKM) (2023).

Chu, Y., Pengliu, J., Fan, J., Ye, H. & Jiang, T. Tsformer: A temporal-spatial transformer model for traffic prediction. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Algorithms and Architectures for Parallel Processing (ICA3PP), LNCS 15251, 309-318 (2025).

Lai, G., Chang, W.-C., Yang, Y. & Liu, H. Modeling long-and short-term temporal patterns with deep neural networks. In: Proceedings of the ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval 95–104 (2018).

Qin, Y. et al. A dual-stage attention-based recurrent neural network for time series prediction. arXiv preprint arXiv:1704.02971 (2017).

Bai, L., Yao, L., Li, C., Wang, X. & Wang, C. Adaptive graph convolutional recurrent network for traffic forecasting. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst 33, 17804–17815 (2020).

Cui, Y., Xie, J. & Zheng, K. Historical inertia: A neglected but powerful baseline for long sequence time-series forecasting. In Proceedings of the 30th ACM International Conference on Information & Knowledge Management 2965–2969 (2021).

Goodfellow, I., Bengio, Y. & Courville, A. Deep learning (MIT Press, Cambridge, 2016).

Xu, J., Wang, H. & Li, M. Cotattention: Convolutional transformer attention for spatio-temporal feature learning. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst 33, 6789–6800 (2022).

Lee M. et al. Enhancing Topological Dependencies in Spatio-Temporal Graphs with Cycle Message Passing Blocks. In Proceedings of the Third Learning on Graphs Conference (LoG), PMLR 269, (2024).

Kong, W., Guo, Z. & Liu, Y. Spatio-temporal pivotal graph neural networks for traffic flow forecasting. In: Proceedings of the Thirty-Eighth AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (2024).

Deng, Z. et al. St-norm: Spatial and temporal normalization for multi-variate time series forecasting. In: Proceedings of the 30th ACM International Conference on Information & Knowledge Management 3004–3009 (2021).

Funding

No funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yuquan Chu: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, data curation, implementation, visualization, writing - original draft. Tingting Fu: methodology, formal analysis, data curation, writing - review editing. Peng Liu: methodology, formal analysis, supervision, writing - review editing. Haksrun Lao: writing - review editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chu, Y., Fu, T., Liu, P. et al. STICformer: spatio-temporal intrinsic connections transformer for traffic flow prediction. Sci Rep 16, 1881 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31594-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31594-x