Abstract

The control of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) has been an active area of research over the past decade, particularly for operations in complex environments. This paper addresses the finite-time fault-tolerant control problem for UAV subjected to simultaneous actuator faults and wind disturbances. A novel adaptive finite-time disturbance observer-based fault-tolerant control (AFTDO-FTC) scheme is proposed. This scheme integrates a finite-time sliding surface, a nonlinear disturbance observer, and an adaptive controller to achieve accurate tracking of position and attitude. First, a nonlinear disturbance observer is designed to estimate the lumped uncertainty arising from combined faults and wind disturbances. Then, a finite-time sliding surface, formulated using weighted error vectors, is introduced to effectively mitigate the adverse effects of estimation errors from the disturbance observer. Furthermore, adaptive finite-time position and attitude controllers are developed based on the estimates provided by the adaptive disturbance observer. Finally, the effectiveness of the proposed method is verified through comparative simulations and Lyapunov stability analysis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, UAVs have gained widespread popularity in both civil and military applications. Owing to their versatile capabilities and broad applicability, UAVs have been widely adopted across numerous research domains, including tracking control, collision avoidance, aerial manipulation, swarm systems, image processing, and deep learning. The performance of UAVs has been extensively studied and improved in various research contexts1,2,3. However, many UAV accidents have occurred due to errors made by inexperienced operators, environmental disturbances, and failures of onboard components. To prevent secondary accidents and protect high-value research equipment, the development of fault-tolerant control (FTC) systems for robust UAV operation has become increasingly important. A number of multirotor UAVs are designed with actuator redundancy to handle potential faults. Nevertheless, in scenarios where multiple actuators fail during flight, UAVs lacking an FTC mechanism cannot compensate for the motor loss, which may lead to accidents.

Various control algorithms has been investigated to ensure reliable and high-performance flight both before and after the occurrence of a fault. Researchers have explored the development and application of diverse control techniques for UAVs, such as linear and adaptive proportional–integral–derivative (PID) control4, feedback linearization5, backstepping control6, sliding mode control7,8,9, model predictive control10, adaptive control11,12,13, and intelligent control strategies based on fuzzy logic and machine learning. It is thus essential to develop an FTC framework that can be complementarily integrated with existing flight controllers, thereby preserving the advantages of the control methods mentioned above.

When operating at high altitudes, UAVs are subject to adverse effects on attitude control due to factors such as wind gusts and variations in air pressure. Simultaneously, they may also encounter internal issues, such as onboard device failures. These combined challenges complicate the attitude control problem for quadcopters. To address disturbance signals, many researchers have developed compensation systems. In14, a Nussbaum gain was employed to adaptively compensate for sampling errors and actuator failures, thereby effectively mitigating the impact of such failures on flight performance. In15, a nonlinear harmonic disturbance observer and a robust controller were jointly applied to compensate for external disturbances, enabling the system’s attitude angle tracking error under disturbance to converge to an equilibrium point. Furthermore, robust control methods have been integrated with disturbance observer-based control (DOBC) in16 and with nonlinear disturbance observer techniques in17. A time-domain disturbance observer (DOB) was also combined with output feedback control and a sliding mode controller to achieve trajectory tracking control for quadcopter aircraft. These disturbance observers typically exhibit long response times when estimating mismatched disturbances, which in turn increases the overall controller response time.

To address both actuator failures and external disturbances, the authors of18 constructed a novel state observer. By integrating full-loop control with terminal sliding mode control, they designed a finite-time fault-tolerant controller that compensates for fault signals and ensures estimation error converges to zero within a fixed time. In19, a robust adaptive sliding mode Thau observer was proposed to estimate the time-varying amplitude of actuator failure. This observer was incorporated into the fault diagnosis process for each actuator, significantly improving estimation accuracy.

In the design of UAV controllers, finite-time control schemes enable high-precision tracking and rapid convergence performance under external disturbances. For instance, reference20 developed a finite-time fault-tolerant control strategy using an integral terminal sliding mode controller driven by an adaptive fuzzy state observer. In21, adaptive backstepping control was integrated with a fuzzy logic system to accommodate known actuator faults within a finite time horizon. A non-singular fast terminal sliding mode control algorithm was proposed in22 to address trajectory tracking of UAVs subject to multi-source disturbances. Furthermore,21 introduced a fully-connected layer recursive sliding mode fault-tolerant control strategy to achieve system convergence and chattering suppression within a limited time. This approach enhances the adjustment capability for parameter variations induced by external uncertainties and reduces the settling time of the controller. To tackle input saturation, the authors of23 presented a finite-time auxiliary system based on a backstepping control scheme. By incorporating auxiliary compensation signals, this method mitigates the effects of input saturation, thereby improving both the robustness of the UAVs against aggregated disturbances and the response speed of the controller.

To further enhance the capability of UAVs in handling actuator and system faults, several advanced control strategies have been proposed. In24, the authors introduced an adaptive incremental nonlinear dynamic inversion (INDI) control method, which enables high-performance nonlinear control without relying on an accurate system model. Meanwhile, the authors of25,26 developed an adaptive backstepping tracking control strategy capable of effectively compensating for external unknown disturbances while achieving precise attitude tracking. In27, a novel adaptive fuzzy terminal sliding mode control scheme was designed for uncertain nonlinear systems subject to external disturbances and successfully applied to a two-link robotic arm control system. Furthermore, the authors of28,29,30 integrated adaptive control techniques with neural networks to address partial failures and jamming of aircraft actuators. They designed an adaptive neural network-based fault-tolerant controller that ensures stable tracking performance under system parametric uncertainties and actuator faults.

Combined with the above research results, this paper combines the finite time strategy and adaptive control method into the design of the disturbance observer, which not only reduces the estimation error caused by external disturbances, but also shortens the response time of the disturbance observer. The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

-

(1)

This work addresses combined fault conditions, including actuator efficiency loss, sensor biases, and unknown external disturbances, within a unified framework.

-

(2)

The mathematical model of quadrotor UAVs under combined faults is established, and the method for calculating parameters is provided.

-

(3)

A new AFTDO observer is proposed, which can accurately and quickly compensate for actuator faults and external disturbances, enhancing the system’s responsiveness while maintaining robustness.

-

(4)

Designing position and attitude controllers based on AFTDO disturbance observers. The challenges of UAV flight in complex environments are further examined. Compared with traditional control methods, it has more practical significance.

The remaining sections of this paper are as follows. Section “Problem formulation and quadrotor dynamics” describes the combined faults and corresponding assumptions. In Section “Fault-tolerant control scheme”, the nonlinear disturbance observer and the Pose controller is designed based on the paper scheme, along with the proof process. In Section “Simulation”, simulation results are presented using MATLAB/Simulink based on the proposed control scheme. Finally, in Section “Conclusions”, conclusions and future work recommendations are provided.

Problem formulation and quadrotor dynamics

Quadrotor dynamics

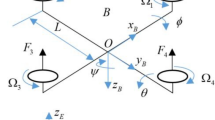

To describe the quadrotor dynamic model, two coordinate systems are introduced, the quadrotor coordinate system and Earth-Centered Inertial coordinate system, which are denoted as \(\left\{ {\varvec{B}} \right\} = \{ O_{b} ,x_{b} ,y_{b} ,z_{b} \}\) and \(\left\{ {\varvec{A}} \right\} = \{ O_{e} ,x_{e} ,y_{e} ,z_{e} \}\), shown in (Fig. 1).

We can know in Fig. 1, motors 1 and 3 rotate counterclockwise; motors 2 and 4 rotate clockwise. Motors are installed at the top diagonal of the quadcopter body, with a distance of \(l\) from the center of mass, The lift \(F_{s} (s = 1,...,4)\) generated by the propeller is opposite to the direction of gravity, The torque \(\tau_{s}\) generated by the four propellers cancels each other out, Fig. 2 illustrates the lift characteristics under fault-free conditions.

Based on the model structure of the quadrotor, the coordinate transformation matrix from the ground coordinate system to the body coordinate system, denoted as \(C_{g}^{b}\):

According to the theorem of momentum and moment of momentum, the system of dynamic differential equations can be obtained:

where \(m\) is the quadrotor’s weight;\(F_{b}^{T} = [0,0, - f_{T} ]^{T}\) is the lift vector in the body coordinate system;\(f_{T}\) denotes the total thrust magnitude of the rotors;\(G_{g} { = [0,0,}mg{]}^{T}\) is the gravity vector in the body coordinate system;\(\xi_{g} = [u,v,w]^{T}\) represents the translation velocity vector in the ground coordinate system;\(\tau_{b}^{T} = [\tau_{\phi } ,\tau_{\theta } ,\tau_{\psi } ]^{T}\) is the control torque vector in the body coordinate system;\(\tau_{\phi } ,\tau_{\theta } ,\tau_{\psi }\) represents the roll, pitch, and yaw control torques, respectively;\(\omega_{b} = [p_{b} ,q_{b} ,r_{b} ]^{T}\) is the angular velocity in the body coordinate system;\(\Gamma_{b}\) is the gyroscopic torque on the quadrotor caused by rotor rotation;\(I_{b}\) is the inertia tensor matrix of the quadrotor. In addition,

where \(I_{x} ,I_{y} ,I_{z}\) represent the roll, pitch, and yaw rotational inertias of the quadrotor, \(\Omega_{r} = \Omega_{1} - \Omega_{2} + \Omega_{3} - \Omega_{4}\) denotes the sum of the rotational speeds of the four motors.\(I_{r}\) is the polar moment of inertia of a single rotor.

The kinematic equations of the quadrotor can be expressed in the following form:

where \(\eta_{b} = [\phi ,\theta ,\psi ]^{T}\) represents the attitude vector;\(Q\) is the transformation matrix relating the rate of change of the attitude angles to the body angular velocities;\(p_{g} = [x_{g} ,y_{g} ,z_{g} ]^{T}\) is the position vector of the UAV. Taking the derivative of \(\eta_{b}\) with respect to time yields:

Based on Eqs. (6) and (8), the differential equation for the Quadrotor attitude angles can be obtained as follows:

where \(\Pi = I_{b} Q\),\(\tilde{\tau }_{b} = \Pi^{ - 1} \tau_{b}\),\(\tau_{b}\) represents the actual control torque of the quadrotor, \(D(\cdot)\) represents the system disturbances acting on the body.

Lemma 1

For a nonlinear system \(\dot{x}(t) = f(x(t))\), if there exists a positive definite Lyapunov function \(V(x)\), its time derivative satisfies the following relation:

where \(A > 0,B > 0,s \in (0,1)\),the system converges to the set \(\left\{ {x|V^{1 - a} (x) \le \frac{B}{A(1 - \gamma )}} \right\},\gamma \in (0,1)\), and converge to \(T \le \frac{{V^{1 - a} (x(t_{0} ))}}{A\gamma (1 - a)}\).

Problem formulation

The quadcopter belongs to a typical underactuated system. When a quadcopter performs flight missions in unknown environments, it is very susceptible to various types of external interference, which can cause plane crashes. When studying the control algorithm of quadcopter unmanned aerial vehicles, the vector of uncertainty in the altitude and attitude modeling is:

The design and analysis of finite-time fault-tolerant control algorithms require the following assumptions.

Assumption 1

Only consider the impact of constant wind on quadcopter drones, without taking into account turbulent wind.

Assumption 2

The flight control chip of quadcopter aircraft has sufficient computing power to meet control requirements.

Assumption 3

Each component of the uncertainty perturbation model \(\ell (x,t)\) is unknown, but there are fixed boundaries.i.e., for \(i = 1 \cdots 4\),

where the bounding function \(\overline{\ell }_{i} (x,t)\) is known.

Assumption 4

Damage to propeller blades or decrease in rotational speed indicates actuator failure. For example, damage to propeller blades can lead to a partial loss of thrust generated by the corresponding rotor5. Therefore, the actuator fault considered is modeled as follows. for \(s = 1 \cdots 4\),

where \(w_{s}\) represents the propeller blade speed,\(w_{s}^{ * }\) is actual speed of the malfunctioning propeller, and \(\alpha_{s} \in \left( {\overline{\alpha },1} \right]\) is an unknown constant and represents the current propeller rotation reduction factor,\(\overline{\alpha }\) indicates the lower line of propeller speed required for quadcopter. For example,\(\overline{\alpha } = 0\) indicates that the propeller is stuck or completely damaged, and \(\alpha_{s} = 1\) indicates that the propeller is in normal operation, and \(0 < \overline{\alpha } < \alpha_{s} < 1\) represents a faulty rotor. Figure 3 illustrates the lift characteristics under actuator fault conditions.

Assumption 5

Further considering bias faults and external disturbances, they are collectively referred to as lumped disturbances along with actuator faults.

where \(\sigma_{i} (t)\) is 0 indicate no bias or 1 indicate bias.\(\left| {d_{i} (t)} \right| \le {\text{D}}_{i}\) indicate bounded external disturbance and \({\text{D}}_{i}\) is a constant.

Remark 1

The disturbances \(d^{ * } (k)\) considered in this article mainly depend on unknown environmental disturbances and do not take into account disturbances from the body components themselves. Over a short sampling period, we define the lumped disturbance as remaining nearly constant or varying within an extremely small range, i.e.\(\Delta d^{ * } (k + i) \approx 0\).

Fault-tolerant control scheme

In this section, a detailed derivation of the nonlinear disturbance observer for the quadrotor will be presented, and a corresponding fault-tolerant control strategy will be proposed to address combined faults.

Design of nonlinear disturbance observer

To enable the observer in this paper to better estimate the effects of combined faults, and following the design approach of the disturbance observer, the following nonlinear disturbance observer is obtained:

where \(r(k_{d} )\) is the disturbance observer state vector,\(\hat{e}_{d}^{ * } (k)\) is the estimator of the first component \(D(\cdot)\) of \(e_{d} (k_{d} )\),\(q(x(k_{d} ),x(k_{d} + 1))\) and \(G(x(k_{d} ),x(k_{d} + 1))\) are the observer function vectors. In order to design of observer, we propose the following scheme.

Theorem 1

Design of the state observer satisfies assumption3. If the observer has accurate estimation, then the chosen function \(q(x(k_{d} ),x(k_{d} + 1))\) and \(G_{ob} = {\text{diag}}\left\{ {l_{1} ,l_{2} ,l_{3} } \right\}\) needs to satisfy the following conditions:

Proof of Theorem 1

To demonstrate the stability of the DNDOB, we define:

The next moment \(e_{ob} (k_{d} )\) can be represented as

According (14), the above error system can be rewritten as

According to Remark 1 and (14), we can obtain \(\Delta e^{ * } (k_{d} + i) = 0\),In addition,\(\left| {1 - l_{i} } \right| < 1\), which implies selecting as \(G(\cdot,\cdot)\) a Schur matrixthe nonlinear disturbance observer can asymptotically track the disturbance of system.

According to Assumption 5 all disturbances as lumped disturbances, the observer primarily estimates the angular velocity \(e_{w}\) of the UAV and the disturbance estimation values \(e_{ob} (k_{d} )\),so:

Construct Lyapunov function as follows:

where P is positive definite symmetric matrix.

Derivative of the above equation can obtain:

Select \({\text{P}}k_{2} = g^{T}\), then:

Select \(k_{2} = \Gamma g^{T}\) can obtain:

According to the finite time stability theorem, if there exists a constant \(c > 0\cdot\gamma \in (0,1)\) such that \(\dot{V} \le - cV^{\gamma }\), the observer can converge in finite time, and the upper limit of convergence time is:

Select \(\alpha 1 = 0.5,\alpha 2 = 0\;\cdot\;sig(e_{w} )^{\alpha 2} = sig(e_{w} )\) then:

According to the finite time stability theorem, the system can converge within a finite time and the upper limit of convergence time is:

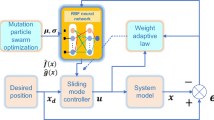

Adaptive finite-time fault-tolerant controller design

Based on the disturbance observer designed in the preceding section, a finite-time fault-tolerant control (FTC) strategy is developed in this section for a quadrotor system subject to combined faults. The overall control structure is illustrated in (Fig. 4). Due to the under-actuated nature of the quadrotor, decoupling computation is essential for coordinating the position and attitude subsystems. In this scheme, both subsystems compare the observed state estimates with the corresponding reference signals, while an Adaptive Finite-Time Fault-Tolerant Controller provides real-time compensation for the resulting tracking deviations.

Attitude controller design

Based on the model established in the Sect. 2, when the system is subject to combined fault disturbances, attitude tracking error is defined as

where Attitude tracking error \(e_{\Theta } = \left[ {e_{\Theta \phi } ,e_{\Theta \theta } ,e_{\Theta \varphi } } \right]^{T}\).

Selected terminal sliding surface was:

where \(\delta_{i} ,\sigma_{i} > 0\) and \(0 < a = \frac{n}{m} < 1\), Since the solution process for the three attitude angles is similar, the pitch angle is used as an example.

The pitch subsystem of the quadcopter is represented as

where \(u_{\theta }\) is the expected control input that needs to be obtained,\(g_{\theta } (x) = I_{y}^{ - 1}\),\(d\) represents external interference and is a component of \(D(\cdot)\).

Pitch angle tracking error was

It immediately follows that:

Select the terminal sliding surface as

Derivative of t he above equation, we can obtain:

The reaching law for the sliding mode surface is selected:

Based on Eq. (29) and the sliding mode surface, the expression for controller \(u_{\theta }\) is obtained as follows:

Theorem 2

Assume that there exists a positive definite and continuous function \(S(x)\), satisfies the inequality \(\dot{s}_{x} + \delta s_{x} + \sigma s_{x}^{a} < 0\), The initial state of system is \(s_{0}\),\(\delta ,\sigma > 0\) and \(0 < a < 1\) Then the state \(S(x)\) will converge to the equilibrium point in a finite time.

Proof of Theorem 2

In order to verify that the unmanned aerial vehicle system can reach a convergence state within a finite time after being affected by actuator efficiency loss and sudden disturbances,When \(t \to 0\), then \(\phi \to \phi_{c} ,\psi \to \psi_{c} ,\varphi \to \varphi_{c}\).

The Lyapunov function is selected as follows:

Substituting Eqs. (34) and (35) into Eq. (33) to get:

Substituting the above expression into Eq. (37) and differentiating yields:

According to Assumption 3, it follows that:

where \(k,\eta ,d\) is a positive real number greater than 0, so can be obtained \(\dot{V}_{1} < 0\). According to the Lyapunov stability criterion, the designed sliding surface will gradually converge to a stable state, indicating that the yaw angle control process in the attitude controller can continue to reach a stable state after being disturbed and faulty, so that the attitude controller can satisfy convergence under global conditions. When \(t \to \infty\), then.

\(e \to 0\).

Therefore, pitch controller ensures pitch system remains asymptotically stable. by appropriately setting parameters, the sliding mode surface can converge to the equilibrium state within finite time, with the convergence time given as

Based on the above analysis, the selected formula (41) can ensure that the subsystem converges quickly to the equilibrium point within a limited time.

Similarly, the tracking errors for the roll and yaw subsystems are given by:

Select the terminal sliding surface as:

The selected reaching law is:

The controller for yaw and roll is designed as:

It follows from the above that: the controller designed in this section ensures that the quadrotor control system ultimately reaches a stable state, and under the Lyapunov stability criterion, it converges asymptotically.

Position controller design

When the system is subject to combined fault disturbances, the position tracking errors in the three directions are defined as follows:

where \(E_{p} = [e_{x} ,e_{y} ,e_{z} ]^{T}\), The actual position \(P = [x,y,z]^{T}\), the desired position \(P_{d} = [x_{d} ,y_{d} ,z_{d} ]^{T}\).

The sliding mode surface for the position subsystem is selected as follows:

The reaching law for the position controller is selected as follows:

Based on the selected sliding mode surface for the system, the input expression for the position control can be obtained as follows:

For the designed controller, the derivative of Eq. (48) can be obtained:

Theorem 3

Consider the augmented system in Eq. (7) and Assumptions 1, 2. and 3. If the finite time convergent position controller is designed as Eq. (48), then the estimated error (47) will converge to the equilibrium point in finite time.

Proof the Theorem 3

The Lyapunov function for the position controller is selected as:

Substituting Eqs. (46) and (48) into the above expression and differentiating yields:

where \(i = x,y,z\), and \(l\) is a positive constant. So we can obtain:

where \(k,\eta ,d\) is a positive real number greater than 0, so can be obtained \(\dot{V}_{2} < 0\).According to the Lyapunov stability criterion, the designed sliding surface will gradually converge to a stable state, indicating that the position controller can meet the required height for flight after being disturbed and faulty, so that the position controller can satisfy convergence under global conditions. When \(t \to 0\), then \(e \to 0\).

According to Theorem 2, the sliding mode surface can converge to the equilibrium point within finite-time, with the convergence time given as:

In summary, the position controller designed in this section ensures that the UAV control system ultimately reaches a stable state and converges asymptotically under the Lyapunov stability criterion.

Simulation

This section presents simulation results to validate the key contributions of this work. First, the fault estimation performance of the proposed AFTDO observer is evaluated. Subsequently, the designed position and attitude controllers are compared with sliding mode control (SMC) and active disturbance rejection control (ADRC) through numerical simulations, highlighting the importance of accounting for combined faults in the controller design.

Prior to the simulation experiments, the system parameters are initialized. Table 1 summarizes the dynamic model parameters of the quadrotor, while Table 2 lists the parameter values used in the fault-tolerant controller.

To evaluate the fault tolerance performance of the proposed algorithm under actuator faults, combined system faults, and external disturbances are simultaneously introduced into the system. As illustrated by the numerical simulation results in (Fig. 5), the disturbance observer developed in this work achieves shorter convergence time and reduced overshoot compared to conventional observers. In scenarios involving both combined faults and unknown disturbances, the proposed method converges to the equilibrium point more rapidly. These results confirm that the proposed strategy offers more effective compensation for aggregated disturbances and exhibits enhanced robustness.

This section evaluates the control performance of the proposed scheme in handling lumped disturbances under a scenario where the complete failure of Motor 1 coincides with a sensor fault at t = 8.5 s. As shown in Fig. 6, following the failure of Motor 1, the altitude of the UAV decreases rapidly. However, within 1 s, the height recovers. This behavior can be attributed to the controller’s detection of the fault in Motor 1, which triggers a compensatory speed increase in Motor 3, as depicted in (Fig. 7). Nevertheless, the thrust from Motor 3 alone is insufficient to fully counteract the disturbance caused by the failure of Motor 1, resulting in a net altitude loss of approximately 0.4 m.

The control performance was further evaluated under a more challenging scenario involving simultaneous partial failure of two motors (Motors 2 and 3) and a sensor fault within the lumped disturbance. In this case, the speeds of Motors 2 and 3 were reduced to 90% of their nominal values. As demonstrated in Fig. 11, the resulting degradation in motor efficiency is clearly observed. Figures 8 and 9 show a distinct descent in UAV altitude, which is primarily attributable to the loss of motor efficiency and the consequent reduction in total lift force. This initial altitude decrease is subsequently compensated by the controller, enabling the trajectory to gradually converge toward the desired value. Quantitative results summarized in Table 3 confirm that the proposed control scheme exhibits superior stability and faster response compared to benchmark methods.

The reduction in propeller speed results in diminished thrust output, preventing the quadrotor from returning to its pre-fault altitude of approximately 5 m. Consequently, the altitude profile exhibits a descending segment, with the vehicle eventually stabilizing at around 4.6 m. As evidenced by the attitude and propeller speed variation curves, the roll angle undergoes a pronounced deviation. This is primarily attributable to the asymmetric thrust distribution among the propellers, which compromises the quadrotor’s lateral stability. Furthermore, speed-induced torque variations generate oscillatory responses in both the pitch and yaw angles.

The attitude error comparison experiments in Figs. 10 and 11 demonstrate that the proposed algorithm achieves faster convergence with significantly suppressed airframe vibration. This improvement results from the controller’s effective compensation for faults and disturbances, which shortens the system response time and confirms its strong fault-tolerant capability.

As shown in Figs. 12 and 13, the amplitude variations in roll and pitch angles are smaller than those obtained using the active disturbance rejection control method. Furthermore, the yaw angle and altitude responses in Figs. 14 and 15 indicate that the proposed control algorithm reduces the descent magnitude of the UAV by 0.2 m. Figure 16 shows that after fault injection, the unaffected motors receive updated control signals, leading to a rapid increase in their rotational speeds. With the intervention of the proposed controller, the quadrotor regains stable operation by t = 13 s.

Conclusions

This paper addresses the finite-time fault-tolerant control problem for quadrotor systems under simultaneous actuator faults and external disturbances. A disturbance observer is designed to estimate the composite uncertainties, followed by the development of a finite-time fault-tolerant controller grounded in finite-time stability theory. Rigorous stability analysis is provided using Lyapunov methods. The proposed controller not only compensates for faults and disturbances effectively but also suppresses system oscillations and guarantees global stability. Simulation results validate that the control scheme ensures global convergence of the quadrotor system, exhibits strong robustness against faults and disturbances, and delivers excellent trajectory tracking performance.

The control strategy presented in this work demonstrates effective performance in handling combined faults and disturbances in simulation environments. Future research will focus on further refinement of the method and its implementation on more complex UAV platforms through hardware-in-the-loop experiments and physical prototypes, thereby enhancing the practical applicability and scalability of the proposed approach.

Data availability

Some or all data, models, or codes that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Nettari, Y. & Labbadi, M. Serkan Kurt, Adaptive robust finite-time tracking control for quadrotor subject to disturbances. Adv. Space Res. 71 (9), 3803–3821 (2023).

Jian, P., Shao, B., Xiong, J. X. & Zhang, Q. Attitude control of quadrotor UAVs based on adaptive sliding mode. Int. J. Control Autom. Syst. 21 (8), 2698–2707 (2023).

Wang, S. Y., Polyakov, A. & Zheng, G. Quadrotor stabilization under time and space constraints using implicit PID controller. J. Franklin Inst. 359 (4), 1505–1530 (2022).

Pounds, P. E. I., Bersak, D. R. & Dollar, A. M. Stability of small-scale UA V helicopters and quadrotors with added payload mass under PID control. Auton. Robot. 33 (1), 129–142 (2012).

Fanni, M. & Khalifa, A. A new 6-DOF quadrotor manipulation system: Design, kinevatics, dynamics, and control. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 22 (3), 1315–1326 (2017).

Hong, M. et al. Fast fixed-time extended state observer-based command filtering backstepping control of free-flying flexible-joint space robots. J. Franklin Inst. 361 (17), 107183–107183 (2024).

M. Saied, H. Shraim, C. Francis, I. Fantoni, and B. Lussier. Actuator fault diagnosis in an octorotor UAV using sliding modes technique: Theory and experimentation. In Proc. Eur. Control Conf. (ECC) pp. 1639–1644. (2015).

Li, B., Gong, W., Yang, Y., Xiao, B. & Ran, D. Appointed fixed time observer-based sliding mode control for a quadrotor UAV under external disturbances. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 58 (1), 290–303 (2021).

Liang, J. C. et al. Adaptive sliding-mode disturbance observer-based finite-time control for unmanned aerial manipulator with prescribed performance. IEEE Trans. Cybernet. 53 (5), 3263–3276 (2023).

Cui, L., Hou, X., Zuo, Z. & Yang, H. An adaptive fast super-twisting disturbance observer-based dual closed-loop attitude control with fixed-time convergence for UAV. J. Franklin Inst. 359 (6), 2514–2540 (2022).

Zhao, G. L., Gao, R. H. & Chen, J. N. Adaptive prescribed performance control of quadrotor with unknown actuator fault. Control Decis. 36 (9), 2103–2112 (2021).

Dai, J. et al. Adaptive control method for morphing trailing-edge wing based on deep supervision network and reinforcement learning. Aerospace Sci. Technol. 153, 109424–109424 (2024).

Campos, M. J. et al. Enhanced robust adaptive flight control for a convertible VTOL UAV[. J. Franklin Inst. 361 (5), 106663 (2024).

Sadiq, M., Hayat, R., Zeb, K., Al-Durra, A. & Ullah, Z. Robust feedback linearization based disturbance observer control of quadrotor UAV. IEEE Access 12, 17966–17981 (2024).

Yang, W. et al. Event-triggered fixed-time fault-tolerant attitude control for the flying-wing UAV using a Nussbaum-type function. Aerospace Sci. Technol. 152, 109336 (2024).

Wei, X. & Guo, L. Composite disturbance-observer-based control and H∞ control for complex continuous models. Int. J. Robust Nonlinear Control IF AC-Affil. J. 20, 106–118 (2010).

Yang, J., Chen, W. H. & Li, S. Non-linear disturbance observer-based robust control for systems with mismatched distur-bances/uncertainties. IET Control Theory Appl. 5, 2053–2062 (2011).

Nguyen, N. P. & Hong, S. K. Fault diagnosis and fault-tolerant control scheme for quadcopter UAVs with a total loss of actuator. Energies 12 (6), 1139 (2019).

Wang, R. et al. Anti-saturation adaptive finite-time neural net-work based fault-tolerant tracking control for a quadrotor UAV with external disturbances. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 115, 106790 (2021).

Wang, F. & Zhang, X. Adaptive finite time control of nonlinear systems under time-varying actuator failures. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybernet. Syst. 49 (9), 1845–1852 (2018).

Zhao, Z. H. et al. Fast nonsingular terminal sliding mode trajectory tracking control of a quadrotor UAV based on extended state observers. Control Decis. 37 (9), 2201–2210 (2022).

Yu, X., Li, P. & Zhang, Y. The design of fixed-time observer and finite-time fault-tolerant control for hypersonic gliding vehicles. IEEE Trans. Industr. Electron. 65 (5), 4135–4144 (2017).

Fu, C. et al. Finite-time trajectory tracking control for a 12-rotor unmanned aerial vehicle with input saturation. ISA Trans. 81, 52–62 (2018).

Smeur, E., Chu, Q. & Croon, G. Adaptive incremental nonlinear dynamic inversion for attitude control of micro air vehicles. J. Guidance, Control, Dyn. Publ. Am. Inst. Aeronaut. Astronaut. Devot. Technol. Dyn. Control 39 (3), 450–461 (2016).

Ng, P. et al. Finite-time adaptive cooperative fault-tolerant control for multi-agent system with hybrid actuator faults. IEEE Syst. J. 16 (3), 3590–3601 (2022).

Zhang, S. et al. Neural networks-based fault tolerant control of a robot via fast terminal sliding mode. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybernet. Syst. 51 (7), 4091–4101 (2021).

Tran, P. V., Santoso, F., Garratt, M., et al. Distributed artificial neural networks-based adaptive strictly negative imaginary formation controller for unmanned aerial vehicles in time-varying environments. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. (99):1 (2020).

Doukhi, O. & Lee, J. D. Neural network-based robust adaptive certainty equivalent controller for quadrotor UAV with unknown disturbances. Int. J. Control Autom. Syst. 17(9), 2365–2374 (2019).

Xu, S. L. & He, B. Robust adaptive fuzzy fault tolerant control of robot manipulators with unknown parameters. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 31 (9), 3081–3092 (2023).

Wei, Y. et al. Fuzzy approximation-based adaptive finite-time tracking control for a quadrotor UAV with actuator faults. Int. J. Fuzzy Syst. 24 (8), 3756–3769 (2022).

Funding

This work was supported by Chengdu Key Research Base for Philosophy and Social Sciences – Research Center for Chengdu Aviation Industry Development and Cultural Construction, grant number CAIACDRCXM2025-42.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, T.L.; methodology, T.L.; software, Y.T.; validation, T.L., and Y.T.; formal analysis, Y.L.; investigation, T.L.; resources, Y.T. and Y.L.; data curation, T.L. and X.F.Y; writing—original draft preparation, T.L.; writing—review and editing, T.L. and X.F.Y; funding acquisition, T.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yan, X., Li, T. & Tian, Y. Adaptive finite-time fault-tolerant control scheme of UAV against combined faults. Sci Rep 16, 2023 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31619-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31619-5