Abstract

Respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) is the leading cause of respiratory failure and neonatal mortality, particularly in preterm infants. Despite global advances in neonatal care, RDS remains a significant problem in low-resource settings such as Uganda, where limited evidence exists on clinical profiles, mortality, and associated risk factors. Although these advances have greatly reduced mortality in high-income settings, their limited availability in Uganda contributes to the continued high burden of RDS-related deaths. To determine the clinical–radiological profile, early mortality, and risk factors for mortality among preterm neonates admitted with RDS at Hoima Regional Referral Hospital. A prospective cohort study was conducted among 150 preterm neonates with clinically and radiologically confirmed RDS. Data on sociodemographic, clinical, and obstetric characteristics were collected using structured questionnaires and chest X-rays. Participants were followed for seven days to determine outcomes. Descriptive statistics summarized baseline characteristics, while Poisson regression identified independent predictors of mortality. Of the 150 neonates, 62.7% were male and 70.7% were born before 32 weeks of gestation. Tachypnea (84.7%) and intercostal/subcostal retractions (71.3%) were the most frequent clinical features, while ground-glass patterns were the predominant radiological finding. Twenty-nine neonates died within the first seven days, giving an early mortality rate of 19.3%. Independent predictors of mortality were delayed presentation beyond six hours of life (aRR = 1.72, 95% CI: 1.43–2.07, p < 0.001) and birth weight < 1.5 kg (aRR = 1.12, 95% CI: 1.02–1.22, p = 0.015). RDS contributes substantially to early neonatal mortality in Uganda. Prompt recognition, early referral, and improved neonatal care—particularly for very low birth weight infants—are critical to improving outcomes. Although not directly measured in this study, improving access to antenatal corticosteroids and respiratory support—well-established interventions—remains essential for broader improvement of RDS outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Respiratory distress syndrome (RDS), also known as hyaline membrane disease, is the most common respiratory condition among premature newborns and a leading cause of neonatal mortality worldwide1. It is primarily caused by insufficient pulmonary surfactant production, leading to alveolar collapse, impaired gas exchange, hypoxemia, and respiratory failure2. Clinical manifestations include tachypnea, nasal flaring, grunting, intercostal retractions, and cyanosis, while radiological findings typically reveal diffuse atelectasis, low lung volumes, and a ground-glass appearance3. Despite major advances in neonatal intensive care, RDS continues to contribute substantially to morbidity and mortality, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs)4.

Globally, neonatal mortality remains high, with almost 40% of under-five deaths occurring in the neonatal period5. An estimated 3.9 million of the 10.8 million childhood deaths annually occur within the first 28 days of life, with RDS being a significant contributor6. In high-income countries, the sequential introduction of oxygen therapy, continuous positive airway pressure, surfactant therapy, and advanced ventilation techniques has dramatically reduced RDS-related mortality7. In contrast, LMICs continue to face higher mortality rates due to limited access to these interventions and shortages of trained personnel8. A recent meta-analysis reported pooled pediatric acute respiratory distress syndrome mortality at approximately 24%, with regional variation highlighting the disproportionate burden in low-resource settings9.

Sub-Saharan Africa carries nearly half (43%) of the world’s neonatal deaths10. In this region, RDS is consistently reported as one of the leading causes of respiratory failure and neonatal mortality11. In many African settings, preterm neonates often experience delays in accessing specialized neonatal care due to challenges with referral pathways, transportation, and limited stabilization at peripheral facilities, leading to late presentation to tertiary neonatal units12. For instance, studies in Tanzania and Ethiopia have reported mortality rates exceeding 30% among preterm neonates with RDS, with risk factors including low birth weight, absence of antenatal steroids, and delayed presentation13.

Uganda continues to experience a high neonatal mortality rate of 27 per 1000 live births, a figure that has stagnated over the last two decades despite improvements in child health14. Neonatal deaths contribute to 42% of all under-five mortality, with one in every sixteen children dying before their fifth birthday15. Respiratory distress syndrome is a major cause of these deaths, particularly among preterm neonates. However, there is limited local data on the clinical-radiological profile, mortality rates, and risk factors associated with early mortality in neonates with RDS16. Most available literature originates from outside Uganda, highlighting the urgent need for context-specific evidence to inform neonatal care practices17.

Respiratory distress syndrome affects up to 29% of preterm neonates admitted to neonatal intensive care units (NICUs), with mortality up to three times higher in East Africa compared to global averages18. Despite its high prevalence and burden, Uganda lacks studies describing the clinical features, radiological profile, and predictors of mortality among neonates with RDS19. Without such data, efforts to reduce neonatal mortality in line with the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) target of reducing neonatal deaths to 12 per 1000 live births by 2030 remain hindered20. Understanding the burden and associated factors of RDS in the Ugandan context is therefore critical.

This study was conducted to address the knowledge gap regarding RDS among preterm neonates in Uganda. By characterizing the clinical-radiological profile, quantifying early mortality, and identifying risk factors for death, the findings will provide crucial evidence to guide neonatal care. The study will also contribute to local and global literature on neonatal RDS, help inform policy, improve resource allocation, and ultimately contribute to reducing neonatal mortality in Uganda21.

Methods

Study design and setting

This was a hospital-based prospective cohort study conducted at Hoima Regional Referral Hospital (HRRH), located in Hoima City, western Uganda. HRRH serves as a referral hospital for eight surrounding districts and has a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) where preterm neonates suspected of respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) are admitted and managed. The study was carried out in the Department of Paediatrics and Child Health.

HRRH neonatal unit is a Level II/III newborn care unit equipped with oxygen therapy, pulse oximetry, bubble CPAP, and phototherapy. Surfactant therapy and mechanical ventilation were not available during the study period. Antenatal corticosteroids are recommended in routine obstetric practice, although coverage remains inconsistent.

Chest radiographs were interpreted by both a paediatrician trained in neonatal respiratory disorders and a hospital radiologist. Imaging was performed within the first 6–24 h following admission.

Infants presenting after six hours of life were predominantly out-born, with delays attributed to transportation challenges and late referral from lower-level facilities. A minority of in-born infants experienced delayed admission due to prolonged resuscitation or stabilization in the labour ward. Hoima Regional Referral Hospital has a Level II neonatal unit with oxygen therapy and bubble CPAP. Mechanical ventilation and surfactant therapy were not available during the study period, and none of the infants with RDS received these interventions.

Study population

The study population consisted of all preterm neonates admitted with RDS during the study period. The target population was all preterm neonates with RDS in the HRRH catchment area, while the accessible population was those presenting to HRRH during the study. Only neonates whose parents or guardians provided informed consent were enrolled.

Eligibility criteria

Preterm neonates with clinical and radiological features of acute RDS were included. Those with features suggestive of RDS but later confirmed to have another diagnosis were excluded.

Sample size and sampling

The sample size was determined using Daniel’s formula and data from previous studies. A total of 150 participants were recruited, accounting for potential loss to follow-up. Consecutive sampling was used, enrolling all eligible neonates admitted with RDS until the sample size was achieved.

Data collection procedures

Data were collected using a structured, pretested questionnaire capturing sociodemographic, obstetric, and clinical information. RDS diagnosis followed WHO and American Academy of Pediatrics criteria requiring at least two clinical signs plus characteristic radiographic findings. Infection in pregnancy’ included laboratory-confirmed infections (e.g., UTI), clinical diagnosis of chorioamnionitis, maternal intrapartum fever ≥ 38 °C, or prolonged rupture of membranes greater than 18 h22. Diagnosis required at least two clinical signs—such as tachypnea, grunting, nasal flaring, retractions, or cyanosis—plus one radiological finding. Anthropometric measurements, particularly birth weight, were taken using digital scales. Each neonate was followed for seven days to determine outcome (survival or death). Clinical assessments were conducted at least twice daily by the neonatal team during the seven-day follow-up. Although detailed clinical features were recorded, the study did not prospectively collect all parameters required to compute formal RDS severity scores such as Silverman–Anderson or Downes scores. Therefore, RDS severity classification was not performed.

Quality assurance

The questionnaire was reviewed by pediatric experts to ensure content validity (Content Validity Index ≥ 0.80) and was pretested using the test–retest method on 10 neonates to ensure reliability (≥ 75%). Data collectors were trained, and daily checks were conducted by the principal investigator to ensure completeness and accuracy.

Data management and analysis

Data were entered into Excel and exported to SPSS version 26 for analysis. Descriptive statistics summarized baseline characteristics, and early mortality was calculated as the proportion of neonates who died within seven days. Poisson regression was used to identify independent risk factors, with results presented as adjusted rate ratios (aRR) and 95% confidence intervals. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Variables with p < 0.20 in bivariate analysis were entered into the multivariable Poisson regression model.

Result presentation

Baseline characteristics of the study participants

In this study, we enrolled 150 preterm neonates with respiratory distress syndrome. Majority of these (80.7%), presented with in their first 6 h of life. Close to two thirds (62.7%) were male. Majority (70.7%) were born before 32 weeks of amenorrhea. The details of the baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Clinical-radiological profile of preterm neonates with respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) admitted at HRRH

Of the 150 participants enrolled with respiratory distress syndrome, the commonest clinical features were tachypnea and intercostal/subcostal recession seen in 84.7% and 71.3% of the participants respectively. The details of the clinical characteristics are shown in Table 2. The most common radiological findings were ground glass pattern (65/150), followed by reticulo-nodular opacity (45/150), fine reticulo-nodular infiltrates (30/150), and lastly fine reticular infiltrates seen in 10/150. None of the infants received surfactant or mechanical ventilation, and RDS care at Hoima consisted mainly of oxygen therapy and occasional bubble CPAP. This limited level of care may have influenced outcomes and affects generalizability. The details of the radiology patterns are shown in Fig. 1.

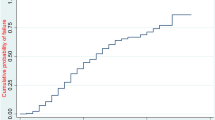

Early mortality among preterm neonates with RDS admitted at HRRH

Of the 150 participants enrolled in the study, 29 passed away with in the first 7 days of life, representing a mortality rate of 19.3%, with a 95% confidence interval of 12.7–26.0%. The details are shown in Fig. 2.

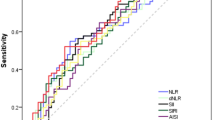

Risk factors for early mortality among preterm neonates with RDS admitted at HRRH

The variables considered for multivariate analysis (P < 0.2) were: age at presentation, prenatal use of steroids, birth weight, mode of delivery and presence of cyanosis. The details of bivariate analysis are shown in Table 3.

In the multivariable analysis, the independent risk factors for early mortality among preterm neonates with RDS were: presentation after six hours of life (aRR = 1.722, CI = 1.433–2.070, P < 0.001) and having a birth weight less than 1.5 kg (aRR = 1.118, CI = 1.022–1.223, P = 0.015). The mortality rate was increased by 72.2% among neonates who presented after six hours compared to those who presented in the first 6 h of life. The mortality rate was increased by 11.8% among neonates who were less than 1.5 kg compared to those who weighed ≥ 1.5 kg at birth. The details are shown in Table 4.

.

Discussion

This study investigated the clinical–radiological profile and risk factors for early mortality among preterm neonates with respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) admitted at Hoima Regional Referral Hospital. The findings show that tachypnea and intercostal/subcostal recession were the most common clinical features, while ground-glass patterns and reticulo-nodular opacities predominated on chest radiographs. These findings are consistent with studies in Iran and Italy that reported tachypnea, retractions, and grunting as common clinical presentations in neonates with RDS23,24. Similarly, radiological profiles such as reticulonodular opacities and ground-glass appearances have been described as pathognomonic features of neonatal RDS25.

The study found a 19.3% early mortality rate, which aligns with pooled estimates of pediatric acute respiratory distress syndrome mortality at 18–24%9,26. Our mortality rate (19.3%) is lower than that reported in Tanzania (31.3%) but comparable to that in China (18.2%)27. The observed mortality in Uganda underscores the persistent gap in neonatal survival outcomes compared to high-income countries, where advances such as surfactant therapy and continuous positive airway pressure have significantly reduced deaths. In high-income settings, early mortality (within the first 7 days) from respiratory distress syndrome is markedly lower, typically ranging from 3 to 5% in the United States, 4–6% in the United Kingdom, and below 5% in most Western European neonatal intensive care units, compared to substantially higher rates reported in low-resource countries such as Uganda7.

Key independent risk factors for early mortality in this study were presentation after six hours of life (p < 0.001) and birth weight below 1.5 kg (p = 0.015), both of which remained statistically significant in the multivariable logistic regression analysis. These findings are in line with evidence from Tanzania and Ethiopia, where low birth weight, delayed presentation, and lack of antenatal steroid use were significant predictors of poor outcomes13,27,28. The biological plausibility is clear: very low birth weight neonates have immature lungs with insufficient surfactant production, increasing their susceptibility to alveolar collapse and hypoxemia2. Delayed presentation may lead to progression of hypoxia and irreversible organ damage before effective interventions are initiated.

The persistence of high RDS-related mortality in Uganda reflects systemic challenges, including limited access to surfactant, advanced respiratory support, and neonatal intensive care29,30. This highlights the urgent need for early recognition, timely referral, and appropriate resource allocation to neonatal services. Strengthening antenatal care, particularly maternal corticosteroid administration, and ensuring availability of neonatal resuscitation and respiratory support technologies are critical to reducing mortality.

Strengthening neonatal care services is essential to reduce RDS-related mortality in Uganda. Early identification and prompt referral of preterm neonates with respiratory distress should be prioritized, with emphasis on timely presentation within the first six hours of life. Availability and accessibility of surfactant therapy, continuous positive airway pressure, and skilled neonatal intensive care must be expanded. In addition, scaling up antenatal corticosteroid use, improving obstetric care, and routine training of healthcare workers in neonatal resuscitation are critical. Policymakers should allocate adequate resources to neonatal units, while future research should focus on context-specific interventions to improve outcomes for very low birth weight infants.

Strengths and limitations

This study is among the first in Uganda to comprehensively describe the clinical–radiological profile and risk factors for early mortality in preterm neonates with RDS, providing locally relevant evidence to guide neonatal care. The prospective cohort design and systematic follow-up for seven days strengthened the reliability of outcome assessment, while the use of both clinical and radiological criteria improved diagnostic accuracy. However, the study was conducted in a single regional referral hospital, which may limit the generalizability of findings to other settings. Additionally, the relatively small sample size constrained the power to detect some associations, and resource limitations, such as restricted access to surfactant therapy and advanced ventilation, may have influenced outcomes.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that respiratory distress syndrome remains a major contributor to early neonatal mortality in Uganda, with nearly one in five preterm neonates dying within the first week of life. Tachypnea and intercostal retractions were the most frequent clinical findings, while ground-glass patterns and reticulo-nodular opacities dominated the radiological profile. Early mortality was strongly associated with delayed presentation beyond six hours of life and very low birth weight (< 1.5 kg). Although these advances have greatly reduced mortality in high-income settings, their limited availability in Uganda contributes to the continued high burden of RDS-related deaths. Strengthening neonatal services is essential if Uganda is to reduce RDS-related deaths and achieve the global target for neonatal survival set under the Sustainable Development Goals.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Christopher, C. & Mallinath, C. Management of respiratory distress syndrome in preterm infants in wales: a full audit cycle of a quality improvement project. Sci. Rep. 10 (1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-60091-6 (2020).

Donald, B., Nabukeera, B., Natukwatsa, D. & Kafunjo, J. Risk factors for neonatal mortality in rural Iganga District, Eastern uganda: a case-control study. East. Afr. Health Res. J. 7 (2), 273–282. https://doi.org/10.24248/eahrj.v7i2.730 (2023).

Franco Poveda, K. G., Holguín Jiménez, M. L., Diaz Sol, N. L. & Ruiz Rey, D. A. Nursing evaluation of neonates with respiratory distress syndrome (RDS). Espirales Rev. Multidiscip Investig. 6 (44). https://doi.org/10.31876/er.v6i44.836 (2023).

Gamhewage, N. C., Jayakodi, H., Samarakoon, J., de Silva, S. & Kumara, L. P. C. S. Respiratory distress in term newborns: can we predict the outcome? Sri Lanka J. Child. Health. 49 (1), 30–34. https://doi.org/10.4038/sljch.v49i1.8895 (2020).

Hegarty, I., Robinson, C. & Heaslip, I. Case 7360: respiratory distress syndrome of the newborn (RDS). Eurorad 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1594/EURORAD/CASE.7360 (2009).

Jobe, A. et al. Injury and inflammation from resuscitation of the preterm infant. Neonatology 94 (3), 190–196 (2008).

Kamath, B. D., Macguire, E. R., McClure, E. M., Goldenberg, R. L. & Jobe, A. H. Neonatal mortality from respiratory distress syndrome: lessons for low-resource countries. Pediatrics 127 (6), 1139–1146. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2010-3212 (2011).

Kamath, B. & Emily, R. Neonatal mortality from respiratory distress syndrome: lessons for low-resource countries. Pediatrics 127 (6), 1139–1146. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2010-3212 (2015).

Kilanowski, J. F. Breadth of the socio-ecological model. J. Agromedicine. 22 (4), 295–297. https://doi.org/10.1080/1059924X.2017.1358971 (2017).

Kumar, R. R. et al. Preterm with respiratory distress. Indian Acad. Pediatr. (IAP) (2022).

Laennec, R. A treatise on the diseases of the chest: in which they are described according to their anatomical characters, and their diagnosis established on a new principle by means of acoustic instruments. Translated by Forbes. Birmingham, AL: Classics of Medicine Library. 1 (1), 1–12 (1979).

Legesse, B. T., Abera, N. M., Alemu, T. G. & Atalell, K. A. Incidence and predictors of mortality among neonates with respiratory distress syndrome admitted at West oromia referral Hospitals, Ethiopia, 2022: a multicentre retrospective follow-up study. PLoS One. 18 (8), e0289050. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0289050 (2023).

Liu, J., Yang, N. & Liu, Y. High-risk factors of respiratory distress syndrome in term neonates: a retrospective case-control study. Balkan Med. J. 31 (1), 64–68. https://doi.org/10.5152/balkanmedj.2014.8733 (2014).

Lloyd, E. L. Respiratory distress syndrome. BMJ 4 (5836), 360. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.4.5836.360-a (1972).

Alauddin, M., Khan, M. A., Amman, A. & Uddin, G. Electrolyte abnormalities in neonates with septicaemia: a hospital-based study. Integr. J. Med. Sci. https://doi.org/10.15342/ijms.2022.634 (2022).

Bernard, G. R. Centennial review. Am. J. Respir Crit. Care Med. 151 (4), 1005–1020. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200504-663OE (1992).

Bhutta, Z. A. & Yusuf, K. Profile and outcome of the respiratory distress syndrome among newborns in karachi: risk factors for mortality. J. Trop. Pediatr. 43 (3), 143–148. https://doi.org/10.1093/tropej/43.3.143 (1997).

Musooko, M. et al. Early neonatal mortality in uganda: findings and implications. Afr. Health Sci. 14 (4), 889–896 (2014).

Simmons, R. Neonatal respiratory distress: current perspectives. Clin. Neonatol. 12 (2), 115–122 (2023).

Wondie, Y. et al. Radiological features of neonatal respiratory distress syndrome in Ethiopian hospitals. Ethiop. J. Health Sci. 33 (2), 143–150 (2023).

Loor Zambrano, H. et al. Radiological patterns in neonatal respiratory distress. Rev. Chil. Pediatr. 93 (1), 44–52 (2022).

American Academy of Pediatrics. Surfactant replacement therapy for preterm and term neonates with respiratory distress. Pediatrics 133 (1), 156–163. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2013-3443 (2014).

Musooko, M. & Orach, C. G. Predictors of neonatal mortality in uganda: a review. Afr. Health Sci. 14 (4), 889–896 (2014).

World Health Organization. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health problems, 10th Revision (ICD-10) (WHO, 2019).

American Academy of Pediatrics. Guidelines for surfactant replacement therapy in preterm infants. Pediatrics 138 (1), e20161691 (2016).

Sweet, D. G. et al. European consensus guidelines on the management of respiratory distress syndrome – 2019 update. Neonatology 115 (4), 432–450. https://doi.org/10.1159/000499361 (2019).

Deorari, A. K., Paul, V. K. & Singh, M. Management of neonatal respiratory distress syndrome in developing countries. Indian J. Pediatr. 79 (4), 478–485 (2012).

Surfactant Research Group. Advances in surfactant therapy: a multicentre trial. Lancet 356 (9231), 1187–1195 (2000).

Kyagulanyi, J. et al. Outcomes of preterm neonates with respiratory distress syndrome at Mulago Hospital, Uganda. Afr. J. Paediatr. Neonatol. 2 (1), 22–29 (2020).

Namusoke, H. et al. Resource setting neonatal intensive care unit: experience from a tertiary hospital in Uganda. BMJ Open. 11 (9), e043989. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-043989 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely thank all study participants for their valuable contributions to this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Abdirahman Hussein Addow, Mohamed Jayte, Geoffrey Ofumbi Oburu, Simon Odoch Jolly Kaharuza, Bappah Alkali, Yasin Ahmed H. Abshir, Hassan Omar Ali, and Walyeldin Elfakey were involved in study design, data collection, statistical analysis, interpretation of findings, drafting, and critical revision of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Ethical clearance for this study was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee of Kampala International University (Ref No: KIU-2025-825). Written informed consent was obtained parents/guardians before enrollment. This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Written consent for participation and publication was secured from every participant’s parent or guardian.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Addow, A.H., Jayte, M., Oburu, G.O. et al. Clinical–radiological profile and risk factors for early mortality in preterm neonates with respiratory distress syndrome in Hoima, Western Uganda. Sci Rep 16, 1944 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31626-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31626-6