Abstract

This cross-sectional study was conducted among hospital staff during the COVID-19 pandemic to assess the prevalence of dry eye disease (DED) symptoms, associated risk factors, and their impact on quality-of-life (QOL). Data were collected via an internet-based survey at a tertiary care hospital from February to June 2022. Participants completed the Thai version of the Dry Eye-related Quality of Life Score (DEQS-Th) to identify DED symptoms, and measures of general QOL and mental health were evaluated using the EuroQol-5 Dimensions-5 Levels (EQ-5D-5L) and Thymometer questionnaires. Of the 1,250 participants (mean age of 39.9 years; 79% female), the prevalence of DED symptoms was 62.1% (95% CI 59.4–64.7%). The mean DEQS-Th score was significantly higher among those with DED (37.7 ± 14.6) compared to those without (8.0 ± 5.3). Multivariable analysis identified several factors significantly associated with DED symptoms, including female gender (p = 0.005), systemic atopy (p = 0.02), preexisting dry eye (p < 0.001), pinguecula or pterygium (p = 0.047), mobile phone use (p = 0.02), infrequent use of artificial tears (p < 0.001), stress (p < 0.001), and impaired QOL (p < 0.001). In conclusion, DED symptoms were highly prevalent among hospital staff during the pandemic, adversely affecting both QOL and mental health. Significant associated factors encompassed demographic, medical, behavioral, and psychological domains.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

During the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic, most countries implemented public health measures to reduce viral transmission, including self-isolation and social distancing. Consequently, remote modalities for education and work became prevalent. This shift led to increased digital screen exposure and prolonged sedentary behavior, both of which have been associated with various health concerns, such as dry eye disease (DED), digital eye strain, myopia, musculoskeletal disorders, and obesity1,2. The pandemic also caused substantial disruptions to daily life, contributing to elevated levels of psychological stress, anxiety, and sleep disturbance3,4. These factors have been implicated in the exacerbation of dry eye symptoms, particularly during periods of lockdown5.

DED is a multifactorial disorder of the ocular surface, recognized as a prevalent condition worldwide. Reported prevalence rates, based on symptoms and signs, range from 5 to 50%, as described by the 2017 International Dry Eye Workshop6. The pathophysiology of DED is primarily characterized by the disruption of tear film homeostasis, leading to ocular surface inflammation, damage, and accompanying symptoms7. Common symptoms of DED include ocular discomfort, fatigue, grittiness, dryness, redness, foreign body sensation, pain, and visual disturbances. These manifestations frequently interfere with daily tasks such as reading, writing, driving, and computer use.

As a chronic condition, DED has a demonstrable impact on both health-related quality-of-life (QOL) and mental well-being6,8,9,10. In addition, DED imposes a considerable socioeconomic burden, not only through direct healthcare costs but also via indirect costs such as reduced work productivity and increased absenteeism9,11,12. Therefore, DED is regarded as a major public health concern, affecting not only individuals but also society as a whole.

Established risk factors for DED include aging, female sex, Asian ethnicity, meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD), connective tissue diseases, Sjögren’s syndrome, androgen deficiency, and modifiable factors such as digital device use, contact lens wear, hormone replacement therapy, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, and the use of certain systemic medications6. Recent shifts in lifestyle and environmental exposure have contributed to the emergence of additional risk factors for DED, including increased digital screen time, alcohol consumption, mental health disorders, and air pollution. Several studies have identified a significant association between prolonged visual display terminal (VDT) use and DED13,14,15. Survey-based studies conducted between 2016 and 2020 have reported high symptom-based prevalence rates of DED, ranging from 62.6 to 85.8%14,15,16. Interestingly, some investigations have observed an inverse relationship between age and DED prevalence14,15,16. Moreover, accumulating evidence suggests an association between DED and mental health conditions, including psychological stress, anxiety, and neuroticism8,10,17.

Since the COVID-19 pandemic, several studies have reported elevated prevalence rates of DED (ranging from 60 to 77%) across different populations, with particularly high rates observed among younger individuals18,19,20. However, there is limited research specifically investigating the prevalence of DED and its associated impact among hospital personnel, who may be particularly susceptible due to occupational factors. These include tasks requiring sustained concentration, prolonged VDT use, work in enclosed environments, use of face masks, and sleep deprivation, particularly among night-shift workers. As frontline responders during the COVID-19 pandemic, healthcare workers were subjected to heightened levels of psychological stress and anxiety, factors that may have further compromised ocular surface health and overall QOL.

The primary objective of this study was to determine the prevalence of dry eye disease (DED) symptoms among hospital personnel during the COVID-19 pandemic. Secondary objectives included identifying factors associated with DED symptoms and evaluating their impact on health-related QOL and mental health. The findings of this study may raise the awareness of DED risk among hospital staff and support the development of management strategies to mitigate its adverse consequences.

Methods

This study was a cross-sectional, observational internet-based survey conducted from February 2022 to June 2022 at a tertiary center, university hospital in Northern Thailand, which has approximately 5,000 personnel. Approval was granted by the Research and Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University (Study code: OPT-2564–08,527), and the study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki guidelines. The survey was launched online using REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture; Vanderbilt University, Tennessee) version 7.6.5 platform. Web-based informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Participants

The hospital staff members of Chiang Mai University Hospital aged ≥ 18 years or older, who were literate in Thai, were invited to participate in the study. Exclusion criteria included other chronic ocular diseases (e.g., glaucoma, uveitis), ocular infections and inflammation within the past 3 months, previous ocular or refractive surgery within the past 6 months, systemic diseases or disabilities that affect daily activities, and psychological disorders (such as depression, bipolar disorder, or schizophrenia) that had been diagnosed by a healthcare professional or was currently receiving treatment at the time of the survey. The collected data included demographics, underlying ocular and systemic diseases, refractive errors, and the main types of correction. It also included receipt of periocular botulinum toxin injection within the past 6 months, duration and type of VDT use, duration and type of face mask use, sleeping time, and use of artificial tears.

Measurements

Four questionnaires were used in this online survey:

-

1)

Self-Developed Questionnaire: This section was designed to collect general information and physical health details, including demographics (gender, age, and occupation); refractive error and correction methods (glasses, contact lenses, or refractive surgery); history of ocular disease and treatments; underlying systemic conditions; current medication; previous eyelid surgery or history of periocular botulinum toxin injection; VDT usage (screen time and type); sleep duration; mask usage (total daily duration and type); and frequency of artificial tear use.

-

2)

The Thai version of Dry Eye-Related Quality-of-life Score Questionnaire (DEQS-Th):This measurement is based on the original DEQS questionnaire, which aims to capture both dry eye symptoms and health-related QOL, functioning as a diagnostic tool for screening DED21,22. It comprised 15 items which were divided into two subscales: “Ocular symptoms” (6 items); and “Impact on daily life”(9 items). Each item was evaluated for frequency and severity, based on a 5-point scale, ranging from “none of the time” (0) to “all of the time” (4) for frequency, and a 4-point scale, ranging from “no affect” (1) to “high affect” (4) for severity. The DEQS score is calculated using the following formula: (sum of the severity scores of all questions answered) × 25/ (total number of questions answered). The higher scores indicated more severe symptoms and poorer QOL21. The DEQS-Th has been translated and culturally adapted into the Thai language23 and has been assessed for its validity and reliability in non-DED and DED participants. The cut-off score for the DEQS-Th of 18 or more was used for diagnosing DED24, although the cut-off score in the original DEQS is > 1522.

-

3)

The Thai version of the EuroQol-5 Dimensions-5 Levels (EQ-5D-5L) Questionnaire25: This tool was used to assess five dimensions of health-related QOL: mobility; self-care; usual activities; pain/discomfort; and anxiety/depression. Each question consists of five response levels: no problems (1); slight (2); moderate (3); severe (4); and extreme problems (5). The EQ-5D-5L index score was calculated from a five-digit code that specified a particular health state (total score = 1—proportion in each dimension). The Thai value set was used for the analysis. The score ranges from 0 (death) to 1(complete health), and negative values indicate a health state considered worse than death

-

4)

The Thymometer Questionnaire26: This single rating scale questionnaire was used to assess mental health in four dimensions: perceived social support; coping; perceived stress; and depression. Each question consisted of 10 response levels of which 1 was the lowest and 10 was the highest. The final scores of perceived social support and coping were calculated from the inversion of the raw scores. Hence, in all four dimensions, the higher the score the worse mental health.

Statistical analysis

The data extracted from the online platform was subsequently analyzed using SPSS software version 25 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and STATA software version 16.0 (Stata Corp, USA). Categorical data was analyzed as a proportion. Numerical data was analyzed as mean (standard deviation, SD) or median (interquartile range, IQR) based on the distribution of the data. To compare the characteristics, QOL scores, and mental health scores between participants with DED and non-DED, Chi-square, Fisher’s exact, Mann Whitney-U and t-test were used based on the type of variable’s types and the data distribution. A p value under 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Exploratory multivariable logistic regression was used to find the associations between DED symptoms and various parameters.

Covariates that could potentially influence dry eye were predefined based on previous literature, including sex (female), age, systemic atopic diseases, preexisting dry eye, pinguecula or pterygium, allergic conjunctivitis, contact lens use, history of laser vision correction, prior eyelid surgery, history of periocular botulinum toxin injection, and use of artificial tears6,18,27,28. Additional covariates that showed a significant association with DED symptoms in this study were subsequently included into the final multivariable linear regression model. Multicollinearity was checked using variance inflation factors (VIFs). Effect sizes for associations between potential risk factors and the presence of DED symptoms were expressed as odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI). The OR of the EQ-5D-5L index was calculated per 0.1-unit decrease, as a 0.1 decrease represents a moderate decline in QOL and is considered clinically meaningful. Pairwise correlation analyses were used to assess the relationships between DED and health-related QOL, and DED and mental health challenges. The sample size was calculated based on a reported DED prevalence of 49.9%9, requiring a minimum of 1,066 participants to achieve a precision estimate of 0.03. The missing data were handled using complete case analysis.

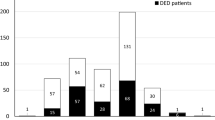

Results

The survey was distributed to all hospital staff members at the Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University (approximately 5,000 individuals), through institutional email and various social media platforms (including Facebook and LINE). A total of 1,730 staff members responded, yielding an initial response rate of 34.6%. After excluding 480 responses due to incomplete data, the final sample comprised 1,250 participants, resulting in a usable response rate of 25%. Among the 1,250 staff members included in the study, the majority were female (987 participants, 79%), with a mean age of 39.92 ± 11.04 years. Most participants were administrative personnel (439, 35%), followed by nurses (344, 27.5%) and research personnel (292, 23.4%). The prevalence of DED symptoms was 62.1% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 59.4–64.7%). Supplementary Fig. 1 shows the prevalence of DED symptoms by occupation. Among all cases, 255 (20.4%) had preexisting dry eyes. Notably, 754 (60.3%) participants had never used artificial tears, while 111 (8.9%) reported daily use. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the median (IQR) device usage per day was 8 (5,10) hours, with mobile phones being the most frequently used device by 746 participants (59.7%). All participants wore face masks daily, with a mean wear time of 9.41 ± 2.99 h per day.

Table 1 shows the characteristics of participants categorized by a diagnosis of DED and non-DED. The parameters of which proportions between DED and non-DED groups were significantly different included female gender (p < 0.001), occupation (p < 0.001), atopic diseases (p < 0.001), dyslipidemia (p = 0.002), preexisting dry eye (p < 0.001), allergic conjunctivitis (p < 0.001), pinguecula or pterygium (p < 0.001), refractive error and types of correction (p < 0.001), total device use time per day (p < 0.001), device use time for work per day (p < 0.001), type of device used (p < 0.001), hours of sleep per night (p = 0.007), hours of mask-wearing per day (p = 0.045), and frequency of artificial tears use (p < 0.001).

The assessment of general QOL by the EQ-5D-5L (Table 2) showed that the participants with DED symptoms had a statistically significantly worse QOL than the non-DED participants. The evaluation of mental health as shown by the Thymometer questionnaire (Table 2) revealed that the perceived social support and coping in participants with DED symptoms were statistically significantly worse than those of the non-DED. Additionally, participants with DED symptoms had statistically significantly greater perceived stress and depression.

Based on the results from Tables 1 and 2, factors showing significant associations to DED symptoms, as well as the EQ-5D-5L and Thymometer subscales were subsequently included in the final multivariable regression model. The VIF ranged 1.11 to 4.98, indicating that multicollinearity was not a concern. The multivariable analysis (Table 3) showed that factors associated with DED symptoms included being female (odds ratio, OR = 1.62; 95% CI = 1.16 to 2.26; p = 0.005), having systemic atopic diseases (OR = 1.64; 95% CI = 1.07 to 2.51; p = 0.02), preexisting dry eye (OR = 3.33; 95% CI = 1.99 to 5.57; p < 0.001), mobile phone use (OR = 1.47; 95% CI = 1.06 to 2.04; p = 0.02), and infrequent use of artificial tears (OR = 1.62; 95% CI = 1.32 to 1.99; p < 0.001). Increased DED symptoms were also associated with higher perceived stress (OR = 1.20; 95% CI = 1.11 to 1.31; p < 0.001). This odds ratio (OR) of 1.20 for perceived stress indicates that each one-point increase in the stress score is associated with a 20% increase in the odds of experiencing DED symptoms. Additionally, Table 3 shows that a 0.1 unit decrease in EQ-5D-5L index scores, reflecting a poorer state of health, is associated with a 110% increase in the odds of experiencing DED symptoms (OR = 2.10; 95% CI = 1.56 to 2.51; p < 0.001).

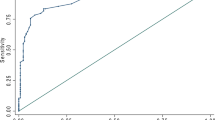

As shown in Table 4, weak negative correlations were observed between EQ-5D-5L and each DEQS-Th subscale, with statistical significance being shown (r = − 0.294 to − 0.350, all p < 0.001). Similarly, each Thymometer dimension showed statistically significant weak positive correlations with the DEQS-Th subscales (r = 0.110 to 0.279, all p < 0.001).

Discussion

This cross-sectional study demonstrates the high prevalence of DED symptoms and their impact on QOL among hospital staff during the COVID-19 pandemic. Several hospital infection control measures, for example, the mandatory use of personal protective equipment (including face masks and gowns), reduced air conditioning leading to elevated indoor temperatures, and frequent use of antiseptics, potentially altering the ocular microbiome, may have contributed to an increased risk of DED. The survey was conducted during the third wave of the pandemic, when antiviral treatments and COVID-19 vaccines were widely available. Most participants were administrative personnel (35.1%) and nurses (27.5%), with a mean age of 39 years. Based on the DEQS-Th criteria, the prevalence of DED symptoms in this cohort was 62%. This rate is comparable to that reported among Palestinian nurses (62%)29 but notably higher than the prevalence reported among physicians and nurses in China (35.8%)30. Variations in reported DED prevalence may be attributable to differences in diagnostic criteria, occupational roles, and the timing of data collection.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the prevalence of DED among paramedical workers in Korea was reported at 42.7%, with an increased risk observed among female workers and those experiencing psychological stress or prolonged computer use17. Similarly, a study among surgical residents (mean age 27.8 years) reported a DED prevalence of 56%, suggesting that working in environments with limited ventilation and tasks requiring high concentration, such as operating rooms, may further elevate DED risk31. These findings underscore the potential influence of environmental factors in hospital settings on ocular surface health.

In this study, covariates for the multivariable model were selected based on both previous literature and significant associations identified in our univariate analyses. Multicollinearity was assessed using variance inflation factors (VIFs) and was not identified as a concern. We found that factors significantly associated with DED symptoms among hospital staff included female gender, systemic atopy, pre-existing dry eye, presence of pinguecula or pterygium, mobile phone use, infrequent use of artificial tears, and mental health challenges such as perceived stress and lower general QOL.

During the pandemic, hospital workers faced tasks demanding sustained concentration and higher cognitive demand, coupled with extensive digital screen use. Although the average screen time among participants was eight hours per day, no significant difference was observed between DED and non-DED groups regarding screen time duration. This contrasts with prior studies demonstrating strong associations between prolonged visual display terminal (VDT) use and DED13,32, where reduced blink rates and incomplete blinking during screen use contribute to increased tear evaporation. This process destabilizes the tear film and leads to hyperosmolarity, both key mechanisms in DED pathophysiology. These findings also diverge from a recent systematic review indicating that extended VDT use (> 4 h/day) increases the prevalence of DED32. This discrepancy of the findings may be potentially due to the differences in study population, the methodology, and the sample size among studies. Additionally, DED among VDT users has been linked to decreased work productivity11.

Notably, mobile phone use emerged as a significant risk factor for DED symptoms in this study. Prior research from Korea identified smartphones as a DED risk factor among pediatric populations33. Smartphones are now integral to daily life, yet their smaller screens and shorter viewing distances may exacerbate ocular fatigue, glare, and irritation. Additionally, blue light exposure from these devices, particularly during evening use, can suppress melatonin production, disrupt circadian rhythms, and impair sleep, all of which are associated with worsening dry eye symptoms34. Poor sleep quality, in turn, has been implicated in exacerbating dry eye35,36, although sleep duration itself was not significantly associated with DED symptoms in this study. Sleep disorders are known to be associated with dysautonomia, which can impair tear production and disrupt tear homeostasis37. A recent study has found that impaired sleep quality, particularly due to sleep fragmentation, is significantly correlated with DED. Both longer sleep latency and shorter sleep duration were shown to worsen DED38. The authors suggested that sleep disruption- especially when related to modern lifestyle factors such as excessive digital device use and mental health issues like depression, anxiety, and stress-significantly increases the risk of developing DED38.

Female gender was also significantly associated with DED, a finding consistent with previous studies reporting higher DED prevalence and severity among women, particularly with advancing age6,39. Hormonal influences on lacrimal and meibomian gland function, goblet cell density, and corneal nerve health are thought to contribute to these sex differences40. Moreover, immune-mediated disease and chronic pain syndrome, more prevalent among women, may also play a role in DED development6.

Additionally, the presence of pinguecula or pterygium was associated with symptoms of DED, supporting the multifactorial nature of DED in the context of ocular surface degeneration7.

While allergic conjunctivitis was not significantly associated with DED symptoms in this study, systemic atopy was. This may be partially explained by the use of antihistamines, which reduce lacrimal gland aqueous production and goblet cell mucin secretion through antagonism of peripheral muscarinic receptors41.

The widespread use of protective face masks during the pandemic, though essential for infection control, has been linked to ocular discomfort and DED, particularly among healthcare workers and individuals with pre-existing DED. Reported rates of mask-associated dry eye range from 7.9 to 70%42,43,44. Potential causative mechanisms include increased airflow towards the ocular surface during exhalation, promoting tear evaporation, and exposure to elevated carbon dioxide levels in exhaled air, which may alter corneal nerve function and promote inflammation45. While prior research suggests the duration of mask-wearing is more impactful than mask type46, our study found no association between both variables and DED symptoms, possibly due to the proficiency of participants with regard to proper mask use.

The pandemic has adversely affected daily life, with particular impact on increased psychological stress and anxiety levels. In this study, DEQS-Th scores showed a significant correlation with general QOL and mental health indicators, including perceived social support, coping strategies, stress, and depression, though correlations were modest. Importantly, we found that even a small decrease in QOL (a 0.1-unit decrease in the EQ-5D-5L index, which typically reflects a clinically meaningful decline in overall health status) is associated with an increase in the odds of experiencing DED symptoms. Psychological stress and impaired general QOL were also independently associated with DED symptoms. These findings align with previous research which linked DED to increased stress and anxiety during the pandemic3,47. The relationship between DED and psychological stress may involve altered pain perception, somatization, and systemic inflammation through cytokine production48. Furthermore, stress may contribute to anxiety and depression, which are known to exacerbate DED symptoms. Stress management interventions may, therefore, play a supportive role in DED management, although longitudinal studies are needed to elucidate these relationships.

This study has several limitations to be addressed. First, all data, including screen time, mask usage, sleep duration, symptoms, diagnoses, and treatments, were self-reported, introducing potential recall bias. Second, participants who should have been excluded, such as those with psychological disorders, may have been inadvertently included in the study due to the anonymous and self-reported nature of the survey, which may affect the accuracy of the analysis.

Third, the diversity of participants in this study may affect the generalizability of our findings make the results may not fully represent health care workers in all setting or roles. Fourth, DED prevalence was assessed solely through symptom questionnaires without confirmation by ocular examinations. As a result, the findings reflect the prevalence of DED symptoms rather than clinically confirmed DED. This approach may overestimate prevalence and miss asymptomatic cases. However, the use of validated symptom questionnaires is common in large-scale studies, especially when clinical examinations are not feasible. In this study, conducting in-person eye exams was particularly challenging due to the COVID-19 pandemic, further justifying reliance on a questionnaire-based survey. Finally, the cross-sectional study design limits the ability to infer causal relationships between associated risk factors and DED symptoms.

In conclusion, DED symptoms were highly prevalent among hospital staff during the COVID-19 pandemic, negatively affecting vision-related QOL and mental health. Significant risk factors included female gender, systemic atopy, existing dry eye, pinguecula or pterygium, mobile phone use, infrequent artificial tear use, psychological stress, and poor QOL. In our study, mask-wearing and total screen time were not linked to DED symptoms. These findings highlight the need for awareness, preventive strategies, and access to proper management to support ocular health as well as work performance in healthcare workers.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- COVID-19:

-

2019 Coronavirus disease

- DED:

-

Dry eye disease

- DEQS-Th:

-

Thai version of dry eye-related quality-of-life score

- EQ-5D-5L:

-

EuroQol-5 dimensions-5 Levels

- QOL:

-

Quality-of-life

- VDT:

-

Visual display terminal

References

Ji, H. et al. Prevalence of dry eye during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 18, e0288523. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0288523 (2023).

Kaur, K. et al. Digital eye strain- a comprehensive review. Ophthalmol Ther 11, 1655–1680. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40123-022-00540-9 (2022).

Chen, Z. et al. Anxiety and depression in dry eye patients during the COVID-19 pandemic: Mental state investigation and influencing factor analysis. Front Public Health 10, 929909. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.929909 (2022).

Qin, G. et al. Effects of insomnia on symptomatic dry eye during COVID-19 in China: An online survey. Medicine (Baltimore) 102, e35877. https://doi.org/10.1097/md.0000000000035877 (2023).

Neti, N., Prabhasawat, P., Chirapapaisan, C. & Ngowyutagon, P. Provocation of dry eye disease symptoms during COVID-19 lockdown. Sci Rep 11, 24434. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-03887-4 (2021).

Stapleton, F. et al. TFOS DEWS II epidemiology report. Ocul Surf 15, 334–365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtos.2017.05.003 (2017).

Craig, J. P. et al. TFOS DEWS II definition and classification report. Ocul Surf 15, 276–283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtos.2017.05.008 (2017).

Na, K. S., Han, K., Park, Y. G., Na, C. & Joo, C. K. Depression, stress, quality of life, and dry eye disease in Korean women: A population-based study. Cornea 34, 733–738. https://doi.org/10.1097/ico.0000000000000464 (2015).

Hossain, P. et al. Patient-reported burden of dry eye disease in the UK: a cross-sectional web-based survey. BMJ Open 11, e039209. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-039209 (2021).

Tananuvat, N., Tansanguan, S., Wongpakaran, N. & Wongpakaran, T. Role of neuroticism and perceived stress on quality of life among patinent with dry eye disease. Sci. Rep. 17, 7027. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-11271-z (2022).

Uchino, M. et al. Dry eye disease and work productivity loss in visual display users: the Osaka study. Am J Ophthalmol 157, 294–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajo.2013.10.014 (2014).

McDonald, M., Patel, D. A., Keith, M. S. & Snedecor, S. J. Economic and humanistic burden of dry eye disease in Europe, North America, and Asia: A systematic literature review. Ocul Surf 14, 144–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtos.2015.11.002 (2016).

Uchino, M. et al. Prevalence of dry eye disease and its risk factors in visual display terminal users: the Osaka study. Am J Ophthalmol 156, 759–766. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajo.2013.05.040 (2013).

Inomata, T. et al. Characteristics and risk factors associated with diagnosed and undiagnosed symptomatic dry eye using a smartphone application. JAMA Ophthalmol 138, 58–68. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2019.4815 (2020).

Kasetsuwan, N. et al. Assessing the risk factors for diagnosed symptomatic dry eye using a smartphone app: Cross-sectional study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 10, e31011. https://doi.org/10.2196/31011 (2022).

Alkabbani, S., Jeyaseelan, L., Rao, A. P., Thakur, S. P. & Warhekar, P. T. The prevalence, severity, and risk factors for dry eye disease in Dubai - a cross sectional study. BMC Ophthalmol 21, 219. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12886-021-01978-4 (2021).

Hyon, J. Y., Yang, H. K. & Han, S. B. Association between dry eye disease and psychological stress among paramedical workers in Korea. Sci Rep 9, 3783. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-40539-0 (2019).

Kunboon, A., Tananuvat, N., Upaphong, P., Wongpakaran, N. & Wongpakaran, T. Prevalence of dry eye disease symptoms, associated factors and impact on quality of life among medical students during the pandemic. Sci Rep 14, 23986. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75345-w (2024).

Cartes, C. et al. Dry eye and visual display terminal-related symptoms among university students during the coronavirus disease pandemic. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 29, 245–251. https://doi.org/10.1080/09286586.2021.1943457 (2022).

Aćimović, L., Stanojlović, S., Kalezić, T. & Dačić Krnjaja, B. Evaluation of dry eye symptoms and risk factors among medical students in Serbia. PLoS ONE 17, e0275624. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0275624 (2022).

Sakane, Y. et al. Development and validation of the dry eye-related quality-of-life score questionnaire. JAMA Ophthalmol 131, 1331–1338. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2013.4503 (2013).

Ishikawa, S., Takeuchi, M. & Kato, N. The combination of strip meniscometry and dry eye-related quality-of-life score is useful for dry eye screening during health checkup: Cross-sectional study. Medicine (Baltimore) 97, e12969. https://doi.org/10.1097/md.0000000000012969 (2018).

Tansanguan, S., Tananuvat, N., Wongpakaran, N., Wongpakaran, T. & Ausayakhun, S. Thai version of the dry eye-related quality-of-life score questionnaire: Preliminary assessment for psychometric properties. BMC Ophthalmol 21, 310. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12886-021-02077-0 (2021).

Tananuvat, N., Tansanguan, S., Wongpakaran, N. & Wongpakaran, T. Reliability, validity, and responsiveness of the Thai version of the dry eye-related quality-of-life score questionnaire. PLoS ONE 17, e0271228. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0271228 (2022).

Pattanaphesaj, J. et al. The EQ-5D-5L valuation study in Thailand. Expert Rev. Pharmacoecon. Outcomes Res. 18, 551–558. https://doi.org/10.1080/14737167.2018.1494574 (2018).

Lohanan, T. et al. Development and validation of a screening instrument for borderline personality disorder (SI-Bord) for use among university students. BMC Psychiatry 20, 479. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-02807-6 (2020).

Qian, L. & Wei, W. Identified risk factors for dry eye syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 17, e0271267. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0271267 (2022).

Zhang, S. Y., Yan, Y. & Fu, Y. Cosmetic blepharoplasty and dry eye disease: a review of the incidence, clinical manifestations, mechanisms and prevention. Int J Ophthalmol 13, 488–492. https://doi.org/10.18240/ijo.2020.03.18 (2020).

Allayed, R., Ayed, A. & Fashafsheh, I. Prevalence and risk factors associated with symptomatic dry eye in nurses in palestine during the COVID-19 pandemic. SAGE Open Nurs. 8, 23779608221127948. https://doi.org/10.1177/23779608221127948 (2022).

Long, Y., Wang, X., Tong, Q., Xia, J. & Shen, Y. Investigation of dry eye symptoms of medical staffs working in hospital during 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak. Medicine (Baltimore) 99, e21699. https://doi.org/10.1097/md.0000000000021699 (2020).

Castellanos-González, J. A. et al. Prevalence of dry eye syndrome in residents of surgical specialties. BMC Ophthalmol 16, 108. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12886-016-0292-3 (2016).

Courtin, R. et al. Prevalence of dry eye disease in visual display terminal workers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 6, e009675. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009675 (2016).

Moon, J. H., Kim, K. W. & Moon, N. J. Smartphone use is a risk factor for pediatric dry eye disease according to region and age: a case control study. BMC Ophthalmol 16, 188. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12886-016-0364-4 (2016).

Haghani, M. et al. Blue light and digital screens revisited: A new look at blue light from the vision quality, circadian rhythm and cognitive functions perspective. J. Biomed. Phys. Eng. 14, 213–228. https://doi.org/10.31661/jbpe.v0i0.2106-1355 (2024).

Ayaki, M. et al. Sleep and mood disorders in women with dry eye disease. Sci. Rep. 6, 35276. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep35276 (2016).

An, Y. & Kim, H. Sleep disorders, mental health, and dry eye disease in South Korea. Sci. Rep. 12, 11046. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-14167-0 (2022).

Lee, Y. B. et al. Sleep deprivation reduces tear secretion and impairs the tear film. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 55, 3525–3531. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.14-13881 (2014).

Jeong, H., Park, S., Kim, H., Jakovljevic, M. & Lee, M. Analysis of sleep quality evaluation factors affecting dry eye syndrome. Int J Gen Med 18, 1845–1854. https://doi.org/10.2147/ijgm.S507631 (2025).

Schaumberg, D. A. et al. Patient reported differences in dry eye disease between men and women: Impact, management, and patient satisfaction. PLoS ONE 8, e76121. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0076121 (2013).

Sullivan, D. A. et al. TFOS DEWS II sex, gender, and hormones report. Ocul Surf 15, 284–333. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtos.2017.04.001 (2017).

Gomes, J. A. P. et al. TFOS DEWS II iatrogenic report. Ocul Surf 15, 511–538. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtos.2017.05.004 (2017).

Fan, Q. et al. Wearing face masks and possibility for dry eye during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sci Rep 12, 6214. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-07724-0 (2022).

Boccardo, L. Self-reported symptoms of mask-associated dry eye: A survey study of 3,605 people. Cont Lens Anterior Eye 45, 101408. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clae.2021.01.003 (2022).

Dag, U., Çaglayan, M., Öncül, H., Vardar, S. & Alaus, M. F. Mask-associated dry eye syndrome in healthcare professionals as a new complication caused by the prolonged use of masks during covid-19 pandemic period. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 30, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/09286586.2022.2053549 (2023).

Burgos-Blasco, B. et al. Face mask use and effects on the ocular surface health: A comprehensive review. Ocul Surf 27, 56–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtos.2022.12.006 (2023).

Erogul, O., Gobeka, H. H., Kasikci, M., Erogul, L. E. & Balci, A. Impacts of protective face masks on ocular surface symptoms among healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ir J Med Sci 192, 521–526. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-022-03059-x (2023).

Wang, X. et al. Subjective dry eye symptoms and associated factors among the national general population in China during the COVID-19 pandemic: A network analysis. J Glob Health 13, 06052. https://doi.org/10.7189/jogh.13.06052 (2023).

Galor, A. et al. TFOS Lifestyle: Impact of lifestyle challenges on the ocular surface. Ocul Surf 28, 262–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtos.2023.04.008 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to all hospital staff who participated in this study by responding to the online survey.

Funding

This work was granted by the Faculty of Medicine Endowment Fund, Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University (Grant no. 070/2565) to NT. The funder had no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis or interpretation of the data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study concept and design: N.T., A.K., P.U., N.W., and T.W. Acquisition of data: N.T., A.K., and P.U. Analysis and interpretation of data: N.T., A.K., P.U., N.W., and T.W. Drafting of the manuscript: N.T. and P.U. Statistical analysis: A.K. and P.U. Critical revision of the manuscript: N.T., P.U., N.W., and T.W. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tananuvat, N., Upaphong, P., Kunboon, A. et al. Prevalence of dry eye disease symptoms and impact on quality-of-life among hospital staff during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sci Rep 16, 2148 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31774-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31774-9