Abstract

In this present study, we developed and validated the Binge Scrolling Scale (BSS) to assess excessive scrolling behavior on digital platforms. Following a systematic framework, we conducted the scale development process in nine steps. We first defined the construct based on a comprehensive literature review and generated an initial pool of 20 items, which was refined to 16 items after eliminating redundancy. A 5-point Likert-type scale was adopted, and a pilot study (N = 21) confirmed the clarity and appropriateness of the response options. Content validity was evaluated by 12 experts using a standard method, leading to the exclusion of three items and revision of one item. Cognitive interviews with a pilot sample supported item clarity and interpretability, with 96% inter-coder agreement. We assessed social desirability bias using two items from the Marlowe-Crowne Scale in a sample of 149 participants; low correlations indicated minimal bias. The scale was then administered to three independent samples, for exploratory factor analysis (EFA) (N = 262), confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) (N = 233), and criterion-related validity (N = 222). EFA revealed a three-factor structure—automatic scrolling, negative outcomes, and loss of control—and resulted in a final 12-item version after removing one item with a low loading. CFA confirmed the structure with good model fit. The BSS showed significant positive correlations with other relevant scales, supporting criterion validity. Reliability analyses across all samples indicated high internal consistency (α = 0.83–0.92; ω = 0.82–0.92). These findings suggest that the 12-item BSS is a valid and reliable measure of compulsive binge scrolling.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The widespread adoption of short-form video platforms has reshaped digital media consumption, fostering a unique behavior termed binge-scrolling, which refers to the consecutive viewing of numerous short videos facilitated by features such as infinite scrolling and algorithmic recommendations that sustain user engagement1. While these design elements are intended to enhance user experience, they paradoxically contribute to loss of self-control and lead users to exceed their intended usage time2,3. Supporting this perspective, algorithmic loops and platform-controlled content flow amplify immersion and diminish the ability to disengage, reinforcing habitual use patterns4. Moreover, boredom and exposure to user-generated content (UGC) have been identified as significant factors driving excessive short video application use, as such platforms provide novel stimuli that promote flow experiences and habitual behaviors5,6. These consumption patterns raise considerable concern regarding their psychological implications, as short video overuse negatively affects intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, as well as overall well-being7. Although flow experiences are highly engaging, they indirectly exacerbate these negative outcomes by sustaining prolonged usage3. In a systematic review, social media scrolling has also been linked to decreased life satisfaction, poor self-esteem, and heightened risks of problematic behaviors that are often conceptualized as behavioral addictions8. Similarly, analyses of streaming platform design reveal features such as triggers, variable rewards, and investment mechanisms as drivers of compulsive usage, highlighting a parallel with the problematic usage qualities observed in short video platforms9.

According to Park and Jung1, binge-scrolling involves infinite scrolling based on algorithmic recommendations, promoting continuous, often unintentional use. This perspective aligns with Karunakaran et al.10, who also identified platform affordances—particularly entertainment, accessibility, and short duration—as significant factors sustaining binge-scrolling behavior. Both studies emphasized the role of platform design in prolonging user engagement, though Park and Jung1 uniquely framed these dynamics within the stimulus-organism-response model, highlighting how external stimuli (e.g., algorithmic recommendations, infinite scrolling) influence users’ internal states (e.g., loss of self-control, regret) and coping mechanisms. In contrast, Kendall11 situates binge-scrolling within the socio-cultural context of the COVID-19 pandemic, interpreting it as a partially functional coping strategy for managing boredom and fostering collective social solidarity. While Park and Jung1 and Karunakaran et al.10 adopted a consumer behavior lens, Kendall11 focused on the affective and participatory dimensions of binge-scrolling during lockdown. Binge-scrolling has been likened to binge-watching due to its sequential and prolonged consumption patterns, yet it differs by focusing on shorter, user-generated content and algorithm-driven infinite feeds that promote passive and often unintended engagement1,10.

Problematic Internet use, problematic social media use, binge scrolling, and short-form video addiction conceptually overlap yet represent distinct digital behavior patterns12,13. Problematic Internet use denotes a generalized loss of control over broad Internet activities that impair daily functioning12, whereas problematic social media use focuses specifically on overuse of social platforms driven by socio-motivational mechanisms such as feedback-seeking and fear of missing out14,15. Short-form video addiction is the most specific form, involving compulsive engagement with ultra-short, rapidly delivered videos with strong reward contingencies16. In contrast, binge scrolling should not necessarily be considered an addictive behavior; instead, it represents a design-driven mode of engagement characterized by prolonged, automatic, and often dissociative scrolling within infinite-feed environments1. Unlike short-form video addiction or problematic social media use—both of which involve clinical features such as withdrawal, tolerance, or functional impairment17,18—binge scrolling reflects the interplay between platform affordances (e.g., algorithmic recommendations) and internal processes such as diminished self-control, flow, and reduced reflective awareness10,11. Conceptually, problematic Internet use serves as the broadest umbrella; problematic social media use highlights socio-motivational mechanisms; binge scrolling captures an engagement style shaped by design-psychology interactions; and short-form video addiction represents an algorithmically intensified problematic video-use pattern19.

Binge-scrolling is also similar to concepts frequently used in the literature, such as short video addiction17, TikTok scrolling addiction20, and compulsive social media use21. All of these concepts refer to the broader notion of problematic Internet use. However, binge-scrolling is considered not merely a problematic video-use behavior, but rather a phenomenon resulting from the design of scrolling platforms and internal psychological processes, which may potentially lead to various other forms of problematic Internet use (e.g., social media, short video, and general internet use)1,10. Indeed, previous studies have demonstrated that platform features such as algorithmic personalization, infinite scrolling, and short-form video conciseness can foster excessive scrolling behaviors, which in turn may lead to problematic forms of media consumption22,23.

Theoretical background

Although only a limited number of theories have directly conceptualized binge-scrolling1, a wide range of theoretical frameworks addressing problematic Internet use (e.g., internet, social media, and online gaming) offer a robust foundation for understanding this phenomenon.

Park and Jung1 adapted the stimulus-organism-response (SOR) model24 to conceptualize binge-scrolling as a media consumption pattern. Stimuli refer to platform features such as algorithmic personalization, infinite scrolling, and the brevity of short-form videos, which serve as external triggers for user behavior. The organism component reflects users’ internal cognitive and emotional states, including diminished self-control, low cognitive engagement, and feelings of regret, which mediate their responses to these external triggers. Finally, responses consist of coping behaviors such as continued scrolling or attempts to disengage from the platform, demonstrating how design features and psychological mechanisms interact to sustain prolonged and often unintended media consumption. In this framework, external platform features function as stimuli that influence users’ internal cognitive and emotional states, including diminished self-control, low cognitive engagement, and emotional responses such as regret. These altered internal states subsequently lead to coping behaviors, which may involve continued scrolling or attempts to disengage. Park and Jung’s1 findings highlight how the adapted SOR model demonstrates the interplay between environmental design features and psychological mechanisms, showing how these dynamics sustain user engagement and contribute to unintended, prolonged usage patterns.

The I-PACE model25,26 provides a biopsychosocial framework that has been widely applied to Internet overuse. It posits that such behaviors emerge from the dynamic interplay among person variables (e.g., impulsivity, genetic predispositions, and early life experiences), affect (e.g., transient emotional states such as boredom and anxiety), cognition (e.g., dysfunctional beliefs, attentional biases, and media-related expectancies), and execution (e.g., self-regulation and inhibitory control)25,26. In the context of binge-scrolling, individual vulnerabilities and negative emotional states interact with cognitive expectancies and impaired executive functioning, leading to automatic and sustained engagement with digital content1. Similar to the SOR model adapted by Park and Jung1, the I-PACE framework emphasizes how external triggers (e.g., platform features) and internal psychological mechanisms collectively drive prolonged and often unintended media use. Both models underscore the role of diminished self-control and maladaptive coping strategies in maintaining user engagement within algorithmically designed content environments.

The dual-process theory suggests that self-control is not merely about controlling and adjusting behavior; rather, it involves multiple cognitive processing stages, including inhibitory self-control and initiatory self-control27. In this context, System 1 is characterized by fast, automatic, and impulsive responses, while System 2 involves slow, deliberate, and reflective processes. Liu et al.28 employed the dual-system model to explain problematic short video use as a self-regulatory failure shaped by these two distinct mechanisms of self-control. Inhibitory self-control primarily involves the suppression of inappropriate impulses and functions as a passive process. This form of control is prone to depletion over time, reducing the individual’s capacity to inhibit short video use and reinforcing problematic use. Conversely, initiatory self-control entails planning, goal setting, and implementing strategies for long-term objectives, reflecting an active process. Individuals with strong initiatory control are better able to regulate their engagement with short videos, as this form of self-control mitigates impulsive tendencies and enhances resilience against problematic use patterns. In this framework, inhibitory control mediates the relationship between past and present time focus and short video overuse, while initiatory control mediates the relationship between future time focus and reduced overuse risk.

In summary, while the SOR and I-PACE models emphasize the interaction between external triggers and internal states, the dual-process theory explains Internet overuse through System 1 (impulsive) and System 2 (deliberate) processes, focusing on inhibitory and initiatory self-control mechanisms.

The present study

The widespread use of short-form video platforms has contributed to excessive scrolling behavior29. This behavior has been associated with various negative outcomes, including decreased learning motivation and reduced well-being during academic activities7, as well as declines in sleep quality30. Moreover, problematic short video watching has been significantly linked to heightened anxiety symptoms31 and attention deficits, as over users report lower interest, reduced concentration, increased distractions, and shorter fixation durations compared to healthy users2. Problematic scrolling has also been reported to be correlated with increased ADHD symptoms, indicating its potential negative impact on cognitive functioning18.

These findings demonstrate the multifaceted psychological risks of short video scrolling and show the need for focused assessment tools. Although scales addressing short video addiction16, problematic short-video use18, and short video dependence32 are prevalent in the literature, these instruments primarily measure the symptoms and criteria of addiction as applied to short video overuse, such as withdrawal, tolerance, and loss of control. However, instruments that directly measure binge-scrolling behaviors remain scarce. A summary of the existing scales related to problematic short video use is presented in Table 1. Notably, binge-scrolling should be conceptualized not merely as a problematic behavior itself but as a potential mediating variable contributing to the development of various problematic Internet use behaviors1,10.

The only study that directly used the term ‘binge-scrolling’ is Park and Jung’s1 research. In their study, most of the items used to measure binge-scrolling were adopted from previous problematic Internet and social media use literature and adapted to the context of binge-scrolling. Because no specific measure exists for binge-scrolling, the scale developed by Park and Jung1 was based on prior research conducted by Tian et al.36 and Xi and Hamari37 (but is not limited to these).

Binge-scrolling’s documented associations with negative outcomes, such as reduced attention, heightened anxiety, and diminished well-being, highlight the need for a targeted assessment tool. Despite its relevance, binge-scrolling remains underexplored in empirical research, with limited theoretical frameworks directly conceptualizing this phenomenon. Developing a validated scale specific to binge-scrolling would address this gap, facilitating future research on its antecedents, correlates, and consequences, and informing intervention strategies to mitigate its adverse effects. In this present study, we aimed to develop and validate the Binge Scrolling Scale (BSS) to assess excessive scrolling behavior on digital platforms. Following DeVellis and Thorpe’s38 framework, we conducted the scale development process in nine systematic steps.

Methods

The scale development process in this study followed DeVellis and Thorpe38 framework and was carried out in nine stages. In developing the scale, we first determined clearly what it is we wanted to measure. (1) This initial step was essential for ensuring conceptual clarity and guiding the subsequent stages of development. (2) Next, we generated an item pool based on a comprehensive review of the literature and relevant theoretical frameworks. (3) After establishing the item pool, we determined the most appropriate format for measurement to promote consistency and ease of response. (4) To assess content validity, the initial items were reviewed by field experts. (5) Following this, we conducted cognitive interviewing to explore how participants interpreted and responded to the items, allowing us to identify potential ambiguities or misunderstandings. (6) We also considered the inclusion of validation items to enhance the scale’s psychometric strength. (7) The items were then administered to a development sample to gather empirical data. (8) We evaluated the items using statistical analyses, including Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA), Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA), criterion validity, and reliability analyses, and refined the scale accordingly to ensure its psychometric soundness. (9) Finally, we optimized the scale length by retaining only the most psychometrically sound items. The present research was conducted in accordance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki, ensuring that all procedures adhered to established ethical standards for research involving human participants. Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Social and Human Sciences Research at Fırat University, and the study was financially supported by Fırat University under the project number EF.25.10, which provided institutional backing for the implementation of the research.

Step 1: Determine clearly what it is you want to measure

In the first stage, we clearly defined the construct of binge scrolling, based on a comprehensive review of the literature.

Step 2: Generate an item pool

In developing the items of the scale, we conducted a comprehensive literature review across databases including Web of Science, Embase, PubMed, PsycINFO, and Google Scholar. Specifically, we examined studies related to the excessive and rapid consumption of digital content. Our focus was on research investigating the overuse and compulsive engagement with scrolling, internet use, social media platforms (e.g., Instagram, Facebook), and smartphones. In addition, we reviewed related scales and studies exploring the symptoms associated with such excessive and rapid usage.

Step 3: Determine the format for measurement

Given the widespread use and familiarity of Likert-type frequency scales, we chose to adopt this response format in our study. We asked participants to indicate how often they engage in each behavior using a 5-point scale ranging from “Never” to “Always.” To evaluate the clarity and appropriateness of the response options, we administered the draft version of the scale to a pilot sample of 21 participants (12 females, 9 males; age = 21–58 years, M = 32.44, SD = 10.74) who were reached through convenience sampling from the general population. We specifically asked them to assess the comprehensibility of the response categories through two questions: (1) How clear and understandable do you find the response options (Never – Always)? and (2) Do you find these response options appropriate for evaluating the following behaviors (i.e., scale items)? Participants were asked to rate each question on a scale from 0 to 10, with scores closer to 0 indicating a more negative evaluation and scores closer to 10 indicating a more positive evaluation.

Step 4: Have the initial item pool reviewed by experts: content validity

To evaluate the content validity of the scale, we consulted 12 experts, all of whom hold at least a PhD degree and specialize in cyberpsychology/Internet addictions and psychometrics. In this process, we employed the technique proposed by Lawshe39. The experts assessed whether each item accurately represented the intended constructs and adequately reflected the overall content domain of the scale. Each item was rated using three categories: (i) appropriate/essential, (ii) partially essential & needs revision, and (iii) inappropriate/unnecessary. Based on these ratings, a Content Validity Ratio (CVR) was calculated for each item.

Step 5: Cognitive interviewing

Cognitive interviewing serves as a qualitative technique aimed at exploring how prospective respondents comprehend and interpret survey items, primarily by eliciting their understanding of item content and the cognitive processes involved in formulating their responses38. Following the evaluation of content validity, we employed a convenience sampling method and distributed the application form to accessible participants. The 13-item scale was administered to 12 participants (6 females, 6 males; age = 24–47 years, M = 33.67, SD = 8.01), who were reached through convenience sampling from the general population in Turkey, for cognitive interviewing. For each item, we asked a series of structured questions: (i) participants were asked to restate the item in their own words to assess their interpretation, (ii) to explain what they considered when selecting their response (e.g., what they focused on when choosing the option “Rarely”), (iii) to rate the ease of responding on a scale from 0 (very easy, no difficulty) to 10 (very difficult, great difficulty), and (iv) to evaluate the clarity of the item on a scale from 0 (very clear, immediately understandable) to 10 (not clear at all, difficult to understand even after repeated reading). If an item was rated as unclear, participants were invited to suggest alternative phrasings for improved clarity. As responding to all these questions for each item would have been time-consuming, cognitively demanding, and potentially detrimental to data quality, we applied the full set of cognitive interview questions only to the even-numbered items (i.e., items 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12). We conducted a content analysis of the qualitative data obtained from the interviews. For each item, we systematically coded participants’ responses and reported the findings using an inductive approach. To ensure the reliability of our analysis, two researchers (M.S. and H.S.) independently carried out the coding process, and inter-coder agreement was calculated.

Step 6: Consider inclusion of validation

To assess potential social desirability bias, we included two items from the 13-item Marlowe–Crowne Social Desirability Scale (MC-SDS) Short Form C40 during data collection: MC-SDS 7 (“I’m always willing to admit it when I make a mistake.”) and MC-SDS 9 (“I am always courteous, even to people who are disagreeable.”). Social desirability refers to respondents’ tendency to answer in a manner viewed favorably by others, which may distort the measurement of the intended construct. Participants were recruited using a snowball sampling method. Initially, we distributed the online survey link to 9 accessible participants, who were reached through appropriate sampling from the general population, and then asked them to invite acquaintances from the general population to participate and share the survey link. Using this method, we obtained a total sample of 149 participants (93 females, 56 males; age range = 18–59 years, M = 29.02, SD = 8.25) from different cities in Turkey. We examined the data for normality using skewness and kurtosis statistics, with all values falling within the acceptable range of ± 1, indicating normal distribution. Therefore, we used Pearson correlation analysis to examine the relationships among items. Items showing high correlations with the social desirability items were flagged for further review and potential exclusion unless strong theoretical justification warranted their retention.

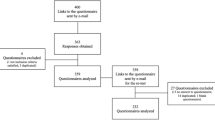

Step 7: Administer items to a development sample

We used a snowball sampling technique to recruit participants through social media. Specifically, the research team initially contacted a core group of 12 individuals via WhatsApp. This group served as the seed for the larger recruitment process by forwarding the survey link to their acquaintances. Additional core groups of 15 and 11 participants were similarly recruited prior to the CFA and criterion-related validity analysis, respectively, and they also contributed to broader recruitment. Ultimately, data from 262 individuals were in the EFA (sample 1), from 233 participants in the CFA (sample 2), and from 222 participants in the criterion-related validity analysis (sample 3); the initial groups of 12, 15, and 11 participants were part of these samples and served as core groups that facilitated broader recruitment. The online survey included an informed consent form at the beginning, in which participants were informed about the purpose of the study and their rights. After reading the form, participants provided their informed consent before proceeding to the main survey. The survey could not be submitted with unanswered items, ensuring complete data. Additionally, we implemented restrictions to allow participation from only one device per individual. Each data collection period lasted approximately two weeks. However, we excluded the data of 2 participants from sample 1 (EFA), 3 participants from sample 2 (CFA), and 6 participants from sample 3 (criterion-related validity) due to inconsistencies such as careless responding (e.g., rating all items as 1 or 5). The data collection process took approximately 10 min per participant for samples 1 and 2, and about 15 min for sample 3. Detailed analyses related to these data are provided in Step 8.

Step 8: Evaluate the items

The construct validity of the Binge Scrolling Scale (BSS) was examined through EFA, CFA, and analyses of criterion-related validity. Its reliability was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha and McDonald’s omega coefficients.

Development sample 1

We conducted an EFA to examine the underlying structure of the BSS. The development sample 1 consists of 262 participants (67% female) aged between 18 and 63 years (M = 29.45, SD = 8.75). Among the participants, 46.90% hold a bachelor’s degree. The most common daily scrolling duration is 1–2 h (40.80%), while 8.40% scroll for 5 h or more. Instagram was the most frequently used platform for scrolling (66.00%), and Pinterest was the least used (1.10%). Scrolling occurred most often before bedtime (31.70%). Only 1.10% have sought professional support due to excessive social media or digital game use. Exploratory factor analyses were conducted using Mplus 8.11. Because the BSS’ items were measured on a 5-point ordered Likert format, they were treated as categorical indicators and analyzed with the weighted least squares with mean- and variance-adjusted chi-square (WLSMV) estimator using a probit link and GEOMIN oblique rotation based on a polychoric correlation matrix. Multiple factor solutions were examined, and model evaluation relied on χ² (chi-square), df (degrees of freedom), RMSEA (Root Mean Square Error of Approximation) with a 90% confidence interval, CFI (Comparative Fit Index), TLI (Tucker–Lewis Index), SRMR (Standardized Root Mean Square Residual), and eigenvalues. Additionally, an open-ended question was included in Development Sample 1 to allow participants to report any issues related to the clarity, relevance, or comprehensibility of the BSS.

Development sample 2

We tested the factor structure identified through EFA in an independent sample using CFA without applying any modifications. The development sample 2 consists of 233 participants (60.90% female) aged between 18 and 67 years (M = 28.01, SD = 9.38). Among the participants, 44.20% hold a bachelor’s degree. The most common daily scrolling duration is 1–2 h (38.60%), while 9.90% scroll for 5 h or more. Instagram was the most frequently used platform for scrolling (59.20%), and Pinterest was the least used (0.90%). Scrolling occurs most often during free time without a specific schedule (32.60%). None of the participants had sought professional support due to excessive social media or digital game use. For the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), we tested the factor structure identified via EFA in a separate sample. Because the items were rated on a 5-point ordered Likert scale, we treated them as ordered categorical indicators and used the WLSMV estimator with a probit link, without specifying any residual error covariances. A second-order CFA was specified in which three first-order factors—F1 (BS7, BS8, BS9, BS11), F2 (BS5, BS6, BS10, BS12), and F3 (BS1, BS2, BS3, BS4)—loaded onto a higher-order Binge Scrolling factor. Model fit was evaluated using χ², df, RMSEA with a 90% confidence interval, CFI, TLI, and SRMR.

Development sample 3

As part of the criterion-related validity analysis, we collected data from 222 participants (93 women, 56 men; age = 18–59 years, Mage = 29.02, SD = 8.25). Alongside the BSS, we administered the Social Media Disorder Scale (SMDS) and the Young Internet Addiction Test – Short Form (YIAT-SF). The SMDS, originally developed by van den Eijnden et al.41 and adapted into Turkish by Savci et al.42, is a unidimensional Likert-type scale consisting of nine items. Higher scores indicate greater problematic social media use. The Turkish version showed significant associations with related psychological constructs, supporting its criterion validity42. The YIAT-SF, originally developed by Pawlikowski et al.43 and later adapted into Turkish by Kutlu et al.44 is a unidimensional Likert-type scale designed to assess problematic internet use. Higher scores indicate greater levels of internet-related difficulties. The unidimensional structure of the scale has been supported through exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses. Criterion validity has been demonstrated through significant associations with related psychological constructs44. Our aim was to examine whether the BSS correlated with related constructs as theoretically expected. Before conducting the analysis, we examined the distribution of the data. Skewness and kurtosis values for all variables ranged between − 1 and + 1, indicating normal distribution. Therefore, we used the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient to assess the relationships between the BSS and these external measures.

Reliability

The reliability of the BSS was examined across the three independent samples. Internal consistency was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha (α) and McDonald’s omega (ω) in the EFA sample, the CFA sample, and the criterion-related validity sample.

Step 9: optimize scale length

In this step, we finalized the BSS. Based on the results of validity and reliability analyses, we decided on the final form of the scale. During this process, we considered whether each item contributed meaningfully to the construct, whether the overall structure aligned with the theoretical framework, and whether the scale was appropriately concise. A brief summary of the nine steps is presented in Table 2.

Results

Step 1: Determine clearly what it is you want to measure

We provided a detailed theoretical definition of the concept of binge-scrolling in the Introduction section. To avoid redundancy, the definition is not repeated here.

Step 2: Generate an item pool

Based on the findings of this comprehensive literature review and relevant theoretical frameworks, we developed an initial pool of items intended to capture the key aspects of scrolling. This preliminary item pool consisted of 20 items designed to reflect the various dimensions identified in the reviewed studies, scales, and theoretical explanations. During the item evaluation process, four items were found to convey the same meaning as other items and were therefore excluded due to repetition. As a result, the initial item pool was refined to 16 distinct items, which served as the foundation for subsequent scale development and validation processes. Subsequent analyses were conducted on these 16 items.

Step 3: Determine the format for measurement

The vast majority of participants indicated that the response options were both clear and appropriate, as well as suitable for assessing the targeted behaviors. None of the participants gave scores below eight. Specifically, for the question regarding the clarity of the response options [Q1: How clear and understandable do you find the response options (Never – Always)? ], 81% of participants assigned a score of 10, 14% gave a 9, and 5% gave an 8. For the question assessing the appropriateness of the response options for evaluating the scale items [Do you find these response options appropriate for evaluating the following behaviors (i.e., scale items)? ], 71% of participants gave a score of 10, 14% gave a 9, and 14% gave an 8. These results suggest that the response format was perceived very positively overall.

Step 4: Have the initial item pool reviewed by experts

Based on the CVR (Content Validity Ratio) analysis, Items 1, 7, and 13 were excluded from the item pool due to insufficient content validity as determined by expert evaluations. Item 16 was identified as borderline and was subsequently revised. The remaining items demonstrated adequate content validity and were retained in the scale. As a result of the elimination of three items, all subsequent analyses were conducted on the remaining 13 items. The CVR values for the 16-item pool are presented in Table 3.

Step 5: Cognitive interviewing

As shown in Table 4, we found that all items reflected the intended construct and prompted participants to consider the targeted concept while responding. Participants reported that the items were clear and easy to answer. Additionally, the agreement rate between the two independent coders was 96%, demonstrating a high level of inter-rater reliability. None of the participants suggested alternative items.

Step 6: consider inclusion of validation

To account for potential social desirability bias, we used two items from the 13-item Short Form C of the Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale (MC-SDS40. Correlations between Item 7 of the MC-SDS and the BSS items ranged from –0.16 to 0.27, while correlations between Item 9 and the BSS items ranged from –0.12 to 0.22. These findings indicate that the BSS items have generally low correlations with social desirability items, suggesting that the two sets of items tap into distinct constructs with minimal overlap.

Step 7: Administer items to a development sample

We administered the BSS sequentially across three independent samples for EFA, CFA, and criterion validity. Additionally, in the EFA sample, we included an open-ended question for participants to report any difficulties with the BSS. However, no participant reported any issues.

Step 8: Evaluate the items

Exploratory factor analyses (EFA)

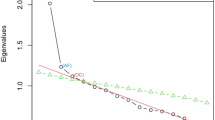

We conducted an EFA on the 13-item binge scrolling structure. In the initial analysis including all 13 items, eigenvalues of the sample correlation matrix suggested up to three substantive factors (λ₁ = 7.13, λ₂ = 1.53, λ₃ = 1.03, λ₄ = 0.78). The 1-, 2-, and 3-factor models all converged. The 1-factor solution showed poor fit, χ²(65) = 656.51, RMSEA = 0.19 (90% CI [0.17, 0.20]), CFI = 0.90, TLI = 0.88, and SRMR = 0.12. Allowing two factors substantially improved the fit, χ²(53) = 178.76, RMSEA = 0.10 (90% CI [0.08, 0.11]), CFI = 0.98, TLI = 0.97, SRMR = 0.04, except for RMSEA. The 3-factor solution provided a further improvement and reached an acceptable level of global fit on all fit indices, χ²(42) = 69.79, RMSEA = 0.05 (90% CI [0.03, 0.07]), CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.99, SRMR = 0.03, with substantial interfactor correlations (r = .56–0.75) and a clear simple structure for most items. However, Item BS13 (“I try to be alone so I can scroll”) showed no meaningful loading on any factor (all loadings < |0.10|) and had an estimated residual variance close to 1.00, indicating that it did not contribute to the latent structure.

For the same 13-item Binge Scrolling structure, models specifying four and five factors showed estimation problems. The 4-factor EFA did not converge within the maximum number of iterations, and the 5-factor solution produced a non-identified rotated solution (standard errors could not be computed, the condition number was extremely small, and several parameters, including residual variances, were implausible). Although the nominal fit indices for the 5-factor solution were excellent (e.g., χ²(23) = 21.75, p = .54; RMSEA = 0.00; CFI/TLI = 1.00; SRMR = 0.01), these identification problems indicate that the 4- and 5-factor models were not trustworthy and therefore were not interpreted.

Given the weak performance of item BS13 in the initial EFA, we removed this item and repeated the analyses with the remaining 12 items. The eigenvalues again supported a multifactor structure (λ₁ = 7.13, λ₂ = 1.53, λ₃ = 0.79). As before, the 1-factor model fit the data poorly, χ²(54) = 626.52, RMSEA = 0.20 (90% CI [0.19, 0.22]), CFI = 0.90, TLI = 0.88, SRMR = 0.12. The 2-factor solution showed a marked improvement (but poor fit based on RMSEA), χ²(43) = 173.34, RMSEA = 0.11 (90% CI [0.09, 0.13]), CFI = 0.98, TLI = 0.97, SRMR = 0.04. The 3-factor model provided the best balance of fit and parsimony and excellent fit for all fit indices, χ²(33) = 59.87, RMSEA = 0.056 (90% CI [0.03, 0.08]), CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.99, SRMR = 0.02, with high primary loadings and conceptually coherent factors, and substantial but interpretable factor correlations (r = .57–0.75). A 4-factor solution also converged and yielded slightly better global indices (χ²(24) = 48.46, RMSEA = 0.06, CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.99, SRMR = 0.02), but showed estimation issues (e.g., a negative residual variance for one item and a weak, poorly defined fourth factor), and therefore was not retained. The 5-factor model again failed to converge (number of iterations exceeded) despite the removal of BS13.

Taken together, using WLSMV with categorical indicators, the pattern of eigenvalues, fit indices, convergence behavior, and interpretability all indicated that the 3-factor solution without Item BS13 provided the most appropriate representation of the data. Consequently, we dropped BS13 from the scale and adopted the 3-factor, 12-item model as the final structure for subsequent analyses.

Based on these results, the number of factors was limited to three, and the analysis was repeated accordingly. This final three-factor solution, which included no items with cross-loadings, is presented in Table 5.

Confirmatory factor analyses (CFA)

We tested the (12-item version’s) factor structure identified via EFA in a separate sample using CFA. Items were treated as ordered categorical indicators and estimated with the WLSMV estimator (probit link), and no residual error covariances were included in the model. A second-order CFA was specified in which three first-order factors—automatic scrolling (BS7, BS8, BS9, BS11), negative outcomes (BS5, BS6, BS10, BS12), and loss of control (BS1, BS2, BS3, BS4)—loaded onto a higher-order Binge Scrolling factor (BS). This model showed acceptable global fit, χ²(51) = 166.17, RMSEA = 0.098 (90% CI [0.08, 0.12]), CFI = 0.98, TLI = 0.97, SRMR = 0.04. Standardized loadings of the items on their respective first-order factors were high (λ = 0.66–0.91), and the first-order factors loaded strongly on the higher-order factor (λ = 0.73–0.95), indicating that automatic scrolling, negative outcomes, and loss of control reflect a common underlying binge scrolling construct while retaining distinct but related dimensions.

Convergent validity

We evaluated the criterion validity of the BSS using the SMDS and the YIAT-SF. Correlation analyses indicated that the BSS was positively and significantly associated with both the SMDS (r = .49, p < .001) and the YIAT-SF (r = .58, p < .001).

Reliability

We examined the reliability of the BSS across three independent samples. In the EFA sample, the internal consistency was high, with a Cronbach’s alpha (α) of 0.92 and a McDonald’s omega (ω) of 0.92. In the CFA sample, Cronbach’s alpha (α) was 0.92 and McDonald’s omega (ω) was 0.91. In the criterion-related validity sample, Cronbach’s alpha (α) was 0.83 and McDonald’s omega (ω) was 0.82.

Step 9: optimize scale length

In this step, we did not attempt to shorten the BSS by removing items. Based on the results of all validity and reliability analyses, we determined that the 12-item, three-factor structure represents the optimal configuration for capturing the construct of binge scrolling. This structure appears theoretically coherent and is of optimal length.

Discussion

The current study focused on developing a valid and reliable instrument to measure automatic scrolling (habitual, repetitive scrolling without a clear purpose, often occurring in solitary contexts), the negative outcomes of scrolling (adverse emotional and physical consequences such as guilt, discomfort, or depression), and loss of control over scrolling (difficulties in resisting or regulating scrolling, along with intrusive thoughts about it), following the nine-step scale development process outlined by DeVellis and Thorpe38.

DeVellis and Thorpe38 emphasize that concept definition from the respondent’s perspective is crucial in scale development. Through cognitive interviewing and independent coding of participant responses, we observed a high inter-rater agreement (96%), supporting that the BSS adequately reflects the targeted construct. In addition, social desirability bias has been considered a crucial limitation in studies on problematic short video use23,30,32. To address this limitation, potential social desirability bias was measured by including validation items according to DeVellis and Thorpe’s38 framework. We found a low correlation between the BSS items and the validation items, suggesting that these items contribute to the validity of the BSS.

As a result of our analysis, we identified a three-factor solution—automatic scrolling, negative outcomes, and loss of control—which was replicated through EFA and CFA. The validity of this three-factor structure is also supported by research on behavioral addiction. Subdimensions of the BSS have been included in various studies10 as antecedents of problematic short video use. The automatic scrolling factor reflects scrolling continuously without a specific purpose. The design of short video platforms already allows for a low-effort, high-reward user experience. Once users become immersed in short-form video viewing, they often enter a passive, automated, and prolonged scrolling cycle. They consume more content and spend more time than they intended45, and loneliness can further increase consumption46,47. Consistent with previous research, loneliness was included in the automatic scrolling factor in the EFA.

The BSS also captures loss of control over use, which is a symptom that paves the way for behavioral addictions48 experiencing guilt49, depression50,51, stress52, and decreased sleep quality46 were identified as negative outcomes of excessive scrolling. In conclusion, evidence from studies examining the problematic aspects of scrolling behavior supports the validity of the construct consisting of automatic scrolling, loss of control, and negative outcomes.

The interaction among automatic scrolling, negative outcomes, and loss of control in digital media use reflects a complex landscape in which distinct yet interrelated processes operate simultaneously. Emerging empirical findings suggest that habitual, cue-driven digital engagement and failures in self-regulatory control may function as theoretically separate but interconnected phenomena53. Recent studies indicate that automatic and habitual behaviors typically arise from fast, impulse-driven action tendencies, whereas loss of control reflects possible disruptions in deliberate inhibitory mechanisms54. This distinction is essential for explaining different functional forms of compulsive digital media use, as demonstrated by Aitken et al.55. Habitual scrolling behaviors are generally associated with an automatism dimension, characterized by repetitive engagement without conscious intent, whereas the loss-of-control dimension—marked by urges, difficulty disengaging, and exceeding intended use thresholds—has been consistently identified in problematic smartphone and social media interactions56.

After establishing a psychometrically robust structure for the BSS by following the recommended steps for developing a valid measurement tool38, evidence for construct validity was provided through relationships with social media disorder, daily scrolling duration, professional support-seeking, time of scrolling, and problematic internet use. Specifically, and consistent with previous research, the BSS was significantly and positively associated with both levels of problematic social media use57 and problematic internet use18,58. In addition, supporting our findings, studies examining the behavioral factors of binge-scrolling have suggested that long daily viewing times, especially at night, and excessive video consumption are key indicators of problematic technology use59. Considering the possibility that the algorithmic design of short video platforms that allow infinite scrolling may stimulate problematic technology use60, the BSS may serve as an instrument that appropriately captures problematic usage.

Strengths

The hedonic nature of short-form video platforms triggers excessive video consumption. The rapid rise of short-form video platforms has raised concerns about problematic technology use16. In an area of high risk for problematic technology use, the BSS provides a strong indication of the extent of excessive scrolling behavior, which has been claimed to play an important role in the development of problematic technology use. Some studies on scrolling examine the impact of social, emotional, and personal factors on excessive use10,52,61. While understanding the influence of emotional and personal factors is undoubtedly essential, determining the level of excessive use is also a priority. The theoretically consistent BSS, with its three-factor structure and appropriate length of 12 items, can comprehensively assess binge-scrolling behavior. Furthermore, the reliability of the BSS was demonstrated in three independent samples (EFA sample, CFA sample, and criterion-related validity sample) with a high level of internal consistency. Therefore, the BSS may fill a gap in problematic media use research by examining the psychological and physical impacts of excessive use itself.

This study identified user experiences before, during, and after scrolling through short videos using a BSS developed with a robust theoretical background. Understanding how and through which mechanisms this online interaction occurs can help identify new and adaptable ways to make engagement with digital media more effective. Users who are aware of the emotional and cognitive effects that follow excessive use may develop the intention to reduce their short video consumption1. This study contributes to the growing body of research exploring the physical, emotional, and cognitive impacts of increased digital media use.

Limitations and future research

While acknowledging the strengths of the BSS, several limitations must be considered. The main idea of the BSS is based on robust models (e.g., SOR, I-PACE, The Dual Systems Theory). Furthermore, the steps suggested by DeVellis and Thorpe38 were meticulously implemented during the scale development process. However, the cross-sectional nature of the current study means that the results cannot be generalized broadly. All data were collected in Turkey through convenience and snowball sampling methods, which support internal consistency but limits cultural diversity across samples. This restricted variability may constrain generalizability of the findings and should be acknowledged as a key limitation. Furthermore, because validity and reliability analyses of the BSS were conducted with a non-clinical sample, future research should examine its psychometric performance in samples experiencing problematic short-video consumption. The BSS is a self-report measure, and its criterion validity was also tested with self-report instruments. While collecting such data is often unavoidable in testing psychometric instruments, self-reported data may not provide completely objective results. We attempted to minimize the risk of social desirability bias, but self-report measures remain susceptible to this limitation. Nevertheless, self-report measures are frequently used in social media research and are essential for assessing self-perceptions of psychological and behavioral change in online environments62. Future research could reduce the limitations of self-report data by using the BSS in conjunction with observational and qualitative studies. Data for the BSS were obtained using a convenience sampling method; thus, employing a random sampling method in future studies could increase its measurement power and broaden its scope of application.

The fact that the variables of problematic social media use42 and internet addiction43, which were tested in the criterion validity analyses, have a significant statistical relationship with the BSS cannot be accepted as definitive evidence of causal relationships between the variables. At the same time, associations between the BSS and established measures of problematic Internet and social media use raise the question of whether binge-scrolling reflects a unique construct or a subtype of broader digital overuse. Although these relationships indicate conceptual overlap, recent evidence suggests that technology-related problems often form a cluster of related but distinct behaviors rather than a single unified syndrome25,26. From this perspective, binge-scrolling can be interpreted as a specific engagement style driven by platform design features—such as infinite feeds and rapid content turnover—rather than as a generalized pathology.

Data availability

Data will be available on request from the corresponding author.

References

Park, J. & Jung, Y. Unveiling the dynamics of binge-scrolling: A comprehensive analysis of short-form video consumption using a Stimulus-Organism-Response model. Telematics Inform. 95, 102200 (2024).

Chen, Y., Li, M., Guo, F. & Wang, X. The effect of short-form video addiction on users’ attention. Behav. Inform. Technol. 42, 2893–2910 (2023).

Yang, Z., Griffiths, M. D., Yan, Z. & Xu, W. Can watching online videos be addictive? A qualitative exploration of online video watching among Chinese young adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 18, 7247 (2021).

Liao, M. Analysis of the causes, psychological mechanisms, and coping strategies of short video addiction in China. Front. Psychol. 15, (2024).

Lu, L., Liu, M., Ge, B., Bai, Z. & Liu, Z. Adolescent addiction to short video applications in the mobile internet era. Front. Psychol. 13, (2022).

Zhang, Y., Bu, R. & Li, X. Social exclusion and short video addiction: the mediating role of boredom and Self-Control. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 17, 2195–2203 (2024).

Ye, J. H., Wu, Y. T., Wu, Y. F., Chen, M. Y. & Ye, J. N. Effects of short video addiction on the motivation and Well-Being of Chinese vocational college students. Front. Public. Health 10, (2022).

Conte, G. et al. Scrolling through adolescence: a systematic review of the impact of TikTok on adolescent mental health. Eur. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry. 34, 1511–1527 (2025).

Flayelle, M., Sigre-Leirós, V., Ferrecchia, L., Gainsbury, S. M. & Billieux, J. How does on-demand streaming technology promote binge-watching? An exploration and classification of streaming platform design features. Psychol. Popular Media. https://doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000579 (2025).

Karunakaran, R., Ram, R. G. & S, A. M. K. Antecedents of Binge-Scrolling Short-form Videos. In: 2022 International Conference on Innovations in Science and Technology for Sustainable Development (ICISTSD) 134–138 (IEEE, 2022). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICISTSD55159.2022.10010460

Kendall, T. From Binge-Watching to Binge-Scrolling. Film Q. 75, 41–46 (2021).

Meerkerk, G. J., Van Den Eijnden, R. J. J. M., Vermulst, A. A. & Garretsen, H. F. L. The compulsive internet use scale (CIUS): some psychometric properties. CyberPsychology Behav. 12, 1–6 (2009).

Volpe, U. et al. COVID-19-Related social isolation predispose to problematic internet and online video gaming use in Italy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 19, 1539 (2022).

Villanti, A. C. et al. Social media use and access to digital technology in US young adults in 2016. J. Med. Internet Res. 19, e196 (2017).

Wölfling, K., Müller, K. W., Dreier, M. & Beutel, M. E. Internet addiction and internet gaming disorder. in The Oxford Handbook of Digital Technologies and Mental Health (eds Potenza, M. N., Faust, K. A. & Faust, D.) 467–476 (Oxford University Press, 2020) https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190218058.013.39.

Ye, J. et al. Short video addiction scale for middle school students: development and initial validation. Sci. Rep. 15, 9903 (2025).

Ding, J., Hu, Z., Zuo, Y. & Xv, Y. The relationships between short video addiction, subjective well-being, social support, personality, and core self-evaluation: a latent profile analysis. BMC Public. Health. 24, 3459 (2024).

Xu, C. et al. The separation of adult ADHD inattention and Hyperactivity-Impulsivity symptoms and their association with problematic Short-Video use: A structural equation modeling analysis. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 18, 461–474 (2025).

Montag, C., Wegmann, E., Sariyska, R., Demetrovics, Z. & Brand, M. How to overcome taxonomical problems in the study of internet use disorders and what to do with smartphone addiction? J. Behav. Addict. 9, 908–914 (2021).

Manzoor, R., Sajjad, M., Shams, S. & Sarfraz, S. TikTok scrolling addiction and academic procrastination in young adults. Pakistan J. Humanit. Social Sci. 3290–3295. https://doi.org/10.52131/pjhss.2024.v12i4.2592 (2024).

Apaolaza, V., Hartmann, P., D’Souza, C., Gilsanz, A. & Mindfulness Compulsive mobile social media Use, and derived stress: the mediating roles of Self-Esteem and social anxiety. Cyberpsychol Behav. Soc. Netw. 22, 388–396 (2019).

Qin, Y., Omar, B. & Musetti, A. The addiction behavior of short-form video app tiktok: the information quality and system quality perspective. Front. Psychol. 13, (2022).

Xie, Z., Han, J., Liu, J. & Guan, W. Short-Form video addiction of students with hearing impairments: the roles of Demographics, parental psychological Control, and psychological reactance. J. Autism Dev. Disord. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-025-06832-w (2025). doi:10.1007/s10803-025-06832-w.

Albert, M. R. A measure of arousal seeking tendency. Environ. Behav. 5, 315–333 (1973).

Brand, M., Young, K. S., Laier, C., Wölfling, K. & Potenza, M. N. Integrating psychological and Neurobiological considerations regarding the development and maintenance of specific Internet-use disorders: an interaction of Person-Affect-Cognition-Execution (I-PACE) model. Neurosci. Biobehav Rev. 71, 252–266 (2016).

Brand, M. et al. The interaction of Person-Affect-Cognition-Execution (I-PACE) model for addictive behaviors: Update, generalization to addictive behaviors beyond internet-use disorders, and specification of the process character of addictive behaviors. Neurosci. Biobehav Rev. 104, 1–10 (2019).

de Boer, B. J., van Hooft, E. A. J. & Bakker, A. B. Stop and start control: A distinction within Self–Control. Eur. J. Pers. 25, 349–362 (2011).

Liu, Y., Huang, Y., Wen, L., Chen, P. & Zhang, S. Temporal focus, dual-system self-control, and college students’ short-video addiction: a variable-centered and person-centered approach. Front Psychol 16, (2025).

Zhang, Q., Wang, Y. & Ariffin, S. K. Keep scrolling: an investigation of short video users’ continuous watching behavior. Inf. Manag. 61, 104014 (2024).

Jiang, L. & Yoo, Y. Adolescents’ short-form video addiction and sleep quality: the mediating role of social anxiety. BMC Psychol. 12, 369 (2024).

Li, S., Zhao, T., Feng, N., Chen, R. & Cui, L. Why we cannot stop watching: tension and subjective anxious affect as central emotional predictors of Short-Form video addiction. Int. J. Ment Health Addict. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-025-01486-2 (2025).

Jiang, A. et al. Assessing Short-Video dependence for e-Mental health: development and validation study of the Short-Video dependence scale. J. Med. Internet Res. 27, e66341 (2025).

Galanis, P., Katsiroumpa, A., Moisoglou, I. & Konstantakopoulou, O. The TikTok Addiction Scale: Development and validation. Preprint at https://doi.org/ (2024). https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-4762742/v1

Wang, X. & Shang, Q. How do social and parasocial relationships on TikTok impact the well-being of university students? The roles of algorithm awareness and compulsive use. Acta Psychol. (Amst). 248, 104369 (2024).

Türk, N. & Yıldırım, O. Psychometric properties of Turkish versions of the short video flow scale and short video addiction scale. Bağımlılık Dergisi. 25, 384–397 (2024).

Tian, X., Bi, X. & Chen, H. How short-form video features influence addiction behavior? Empirical research from the opponent process theory perspective. Inform. Technol. People. 36, 387–408 (2023).

Xi, N. & Hamari, J. Does gamification satisfy needs? A study on the relationship between gamification features and intrinsic need satisfaction. Int. J. Inf. Manage. 46, 210–221 (2019).

DeVellis, R. F. T. C. T. Scale Development: Theory and Applications (5th Edition)Sage publications,. (2022).

Lawshe, C. H. A quantitative approach to content validity. Pers. Psychol. 28, 563–575 (1975).

Reynolds, W. M. Development of reliable and valid short forms of the marlowe-crowne social desirability scale. J. Clin. Psychol. 38, 119–125 (1982).

van den Eijnden, R. J. J. M., Lemmens, J. S. & Valkenburg, P. M. The social media disorder scale. Comput. Hum. Behav. 61, 478–487 (2016).

Savci, M., Ercengiz, M. & Aysan, F. Turkish adaptation of the social media disorder scale. Archives Neuropsychiatry. 55, 246–253 (2018).

Pawlikowski, M., Altstötter-Gleich, C. & Brand, M. Validation and psychometric properties of a short version of young’s internet addiction test. Comput. Hum. Behav. 29, 1212–1223 (2013).

Kutlu, M., Savci, M., Demir, Y. & Aysan, F. Turkish adaptation of young’s internet addiction Test-Short form: a reliability and validity study on university students and adolescents. Anatol. J. Psychiatry. 17, 69 (2016).

Nong, W. et al. The relationship between short video Flow, Addiction, Serendipity, and achievement motivation among Chinese vocational school students: the Post-Epidemic era context. Healthcare 11, 462 (2023).

Zhao, Z. & Kou, Y. Effect of short video addiction on the sleep quality of college students: chain intermediary effects of physical activity and procrastination behavior. Front. Psychol. 14, (2024).

Yue, H., Yang, G., Bao, H., Bao, X. & Zhang, X. Linking negative cognitive bias to short-form video addiction: the mediating roles of social support and loneliness. Psychol. Sch. 61, 4026–4040 (2024).

Virós-Martín, C., Montaña-Blasco, M. & Jiménez-Morales, M. Can’t stop scrolling! Adolescents’ patterns of TikTok use and digital well-being self-perception. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 11, 1444 (2024).

de Segovia Vicente, D., Van Gaeveren, K., Murphy, S. L. & Vanden Abeele, M. M. P. Does mindless scrolling hamper well-being? Combining ESM and log-data to examine the link between mindless scrolling, goal conflict, guilt, and daily well-being. J. Computer-Mediated Commun. 29, (2023).

Liu, Y., Shi, Y., Zhang, L. & Hou, L. Rumination mediates the relationships between social anxiety and depression with problematic smartphone use in Chinese youth: A longitudinal approach. Int. J. Ment Health Addict. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-024-01318-9 (2024).

Qu, D. et al. The longitudinal relationships between short video addiction and depressive symptoms: A cross-lagged panel network analysis. Comput. Hum. Behav. 152, 108059 (2024).

Muhammad Mudasir, A. Scrolling towards stress: the negative influence of mobile reels on hypertensive health. J. Community Med. Health Solutions. 6, 048–049 (2025).

Yu, L., Chen, Y., Zhang, S., Dai, B. & Liao, S. Excessive use of personal social media at work: antecedents and outcomes from dual-system and person-environment fit perspectives. Internet Res. 33, 1202–1227 (2023).

Koban, K., Stevic, A. & Matthes, J. A Tale of two concepts: differential Temporal predictions of habitual and compulsive social media use concerning connection overload and sleep quality. J. Comput. Mediated Commun. 28, (2023).

Aitken, A. et al. Naturalistic fNIRS assessment reveals decline in executive function and altered prefrontal activation following social media use in college students. Sci. Rep. 15, 36960 (2025).

Vannucci, A., Simpson, E. G., Gagnon, S. & Ohannessian, C. M. Social media use and risky behaviors in adolescents: A meta-analysis. J. Adolesc. 79, 258–274 (2020).

Meinhardt, L. M. et al. Scrolling in the Deep: Analysing Contextual Influences on Intervention Effectiveness during Infinite Scrolling on Social Media. In: CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (2025).

Chemnad, K., Aziz, M., Belhaouari, S. B. & Ali, R. The interplay between social media use and problematic internet usage: four behavioral patterns. Heliyon 9, e15745 (2023).

Wang, J. Y. et al. Can’t Stop Scrolling: Understanding the Online Behavioral Factors and Trends of Short-Video Addiction. Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media 19, 2000–2016 (2025).

The European Commission (EC). Commission Opens Formal Proceedings against Meta under the Digital Services Act Related to the Protection of Minors on Facebook and Instagram. (2024).

Marek, J. The impatient gaze: on the phenomenon of scrolling in the age of boredom. Semiotica 107–135 (2023). (2023).

Stuart, J. & Scott, R. The measure of online disinhibition (MOD): assessing perceptions of reductions in restraint in the online environment. Comput. Hum. Behav. 114, 106534 (2021).

Funding

This study is funded by Firat University under project number EF.25.10. Dr. Savci is receiving financial support from the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Turkey (TÜBİTAK) for internet-based interventions related to Internet Gaming Disorder, although this support is not directly related to the present study. Dr. Elhai notes that he receives royalties for several books published on posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD); occasionally serves as a paid, expert witness on PTSD legal cases; and has recently received research grant funding from the U.S. National Institutes of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors made equal contributions to the conception, design, analysis, and writing of this study.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Ethical approval was obtained from the ethics committee of the first author’s university.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Savci, M., Savci, H., Ugur, E. et al. The binge scrolling scale measures excessive scrolling through a validated three-factor structure. Sci Rep 16, 2160 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31861-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31861-x