Abstract

Large language models (LLMs) have demonstrated remarkable capabilities in natural language understanding and reasoning. However, their real-world applicability in high-stakes medical assessments remains underexplored, particularly in non-English contexts. This study aims to evaluate the performance of DeepSeek-R1 and ChatGPT-4o on the Chinese National Medical Licensing Examination (NMLE), a comprehensive benchmark of medical knowledge and clinical reasoning. We evaluated the performance of ChatGPT-4o and DeepSeek-R1 on the Chinese National Medical Licensing Examination (2019–2021) using question-level binary accuracy (correct = 1, incorrect = 0) as the outcome. A generalized linear mixed model (GLMM) with a binomial distribution and logit link was used to examine fixed effects of model type, year, and subject unit, including their interactions, while accounting for random intercepts across questions. Post hoc pairwise comparisons were conducted to assess differences across model–year interactions. DeepSeek-R1 significantly outperformed ChatGPT-4o overall (β = − 1.829, p < 0.001). Temporal analysis revealed a significant decline in ChatGPT-4o’s accuracy from 2019 to 2021 (p < 0.05), whereas DeepSeek-R1 appeared to maintain a more stable performance. Subject-wise, Unit 3 showed the highest accuracy (β = 0.344, p = 0.001) compared to Unit 1. A significant interaction in 2020 (β = − 0.567, p = 0.009) indicated an amplified performance gap between the two models. These results highlight the importance of model selection and domain adaptation. Further investigation is needed to account for potential confounding factors, such as variations in question difficulty or language biases over time, which could also influence these trends. This longitudinal evaluation highlights the potential and limitations of LLMs in medical licensing contexts. While current models demonstrate promising results, further fine-tuning is necessary for clinical applicability. The NMLE offers a robust benchmark for future development of trustworthy AI-assisted medical decision support tools in non-English settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

AI models have brought about significant advancements in healthcare1 , marketing2 and education3. ChatGPT-4o, OpenAI’s conversational AI system, generates text by using deep learning algorithms4,5. It can command a huge quantity of text data, allowing it to effectively capture patterns in language and generate text responses similar to those of humans6,7. Its ability has already be used to explore in professional contexts, including the Chinese national medical.

licensing examinations8,9, pharmacist licensing examination10 and plastic surgery board examination11.

DeepSeek-R1, a specialized model enhanced through large-scale reinforcement learning (RL)12, follows the paradigm of Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF), first introduced by Christiano et al.13 and further developed in large-scale instruction tuning systems such as InstructGPT14. Its demonstrated outstanding performance15 makes it particularly suited for medical licensing evaluations like Chinese NMLE,where nuanced clinical judgment surpasses rote knowledge recall. Applying it to NMLE can enable a more in-depth assessment of medical knowledge and clinical judgment beyond what is traditionally tested, including in-depth reasoning in complex cases.

The Chinese National Medical Licensing Examination (NMLE) is a high-stakes, standardized examination administered by the National Medical Examination Center of China. It serves as a mandatory qualification for physicians seeking clinical practice licenses and comprehensively assesses candidates’ professional competencies. In its latest revision, the NMLE syllabus adopts a competency-based framework that emphasizes clinical relevance, interdisciplinary integration, and alignment with national health priorities. According to official guidelines, the updated examination structure prioritizes practical competence over rote memorization, promotes the integration of basic, clinical, and humanistic medical knowledge, and supports a shift from knowledge-based assessment to capability-oriented evaluation16. The NMLE comprises two major components: a written test and a practical skills assessment. The written test includes approximately 600 multiple-choice questions (MCQs) per year, and is further divided into four units. Unit 1 focuses on foundational medical knowledge, while Units 2–4 assess applied clinical reasoning and diagnostic decision-making.

MCQs in the NMLE are presented in five structured formats: A1 (single-best answer), A2 (case summary-based), A3 (multiple-case-based), A4 (case series-based), and B1 (matching questions)17. This structure challenges examinees not only on factual recall but also on diagnostic judgment and multi-step reasoning, making the NMLE a rigorous benchmark for evaluating large language models in professional medical contexts.

While both DeepSeek-R1 and ChatGPT-4o belong to the family of large language models, they differ markedly in design philosophy and training approach. ChatGPT-4o is a general-purpose model optimized primarily for interactive dialogue and natural language fluency, with training heavily based on Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF)18. Its objective is to align with human intent in open-domain conversations. In contrast, DeepSeek-R1 was explicitly developed to enhance reasoning performance through reinforcement learning19on structured tasks that emphasize deductive and multi-step inference. These architectural and tuning distinctions make them ideal candidates for comparative evaluation on medical licensing exams like the NMLE, where both reasoning depth and communicative clarity are critical.

In recent studies, researchers have evaluated the performance of GPT-3.5, GPT-420, and GPT-4o17 on the NMLE, highlighting the general capabilities of these large-scale models in professional medical testing. However, the emergence of DeepSeek-R1 in early 2025 marks a turning point: as a Chinese-developed, open-source model enhanced through reinforcement learning, DeepSeek-R1 has quickly gained traction in Chinese academic and clinical settings. Despite its growing adoption, no systematic comparison has yet been conducted between DeepSeek-R1 and ChatGPT-4o on the NMLE. Given that the NMLE is administered primarily in Chinese and heavily emphasizes diagnostic reasoning, it remains unclear whether DeepSeek-R1’s language alignment and specialized fine-tuning confer meaningful advantages over general-purpose LLMs. This study aims to fill that gap by providing a comparative evaluation of both models on reasoning-focused clinical tasks from the NMLE.

This study aims to fill that gap by providing a comparative evaluation of both models on reasoning-focused clinical tasks from the NMLE. Based on DeepSeek-R1’s specialized training in reasoning and linguistic alignment with Chinese, we hypothesized that DeepSeek-R1 would significantly outperform ChatGPT-4o in both overall accuracy and appear to present the temporal stability on the Chinese NMLE. We further hypothesized that this performance gap would be most pronounced in complex diagnostic reasoning tasks rather than fact-based recall, and that ChatGPT-4o’s performance would be more sensitive to prompt structure.

Methods

Data sources

We collected official NMLE questions from 2017 to 2021 through institutional archives and publicly available, verified sources. Each annual dataset contained 600 multiple-choice questions (MCQs) covering four major subject areas: internal medicine, surgery, pharmacology, and pediatrics.

To ensure fidelity to the original exam structure, all questions were preserved in their original textual form. Non-textual elements such as images, charts, or radiographic content were excluded to maintain compatibility with text-only model inputs. The entire question sets were converted into a standardized prompt format for uniform processing, but no further modification or filtering was applied.

We explicitly acknowledge that these exam questions are publicly available, which introduces a significant risk of data contamination, as they were likely included in the training corpora of both models. To address this, our study design incorporated a crucial temporal consideration: our evaluation was conducted in March 2025, immediately following the public release of DeepSeek-R1 in February 2025. This narrow time window minimizes the possibility of extensive training or fine-tuning on these specific datasets for DeepSeek-R1, providing a valuable snapshot of its out-of-the-box capabilities.

Conversely, for ChatGPT-4o (with earlier training cutoffs), the risk of prior exposure to the 2017–2021 data is high. Therefore, the performance comparison should be interpreted with this context: DeepSeek-R1’s performance is more likely to reflect reasoning, while ChatGPT-4o’s results may represent a mix of reasoning and knowledge recall (memorization). This contamination risk is further discussed as a limitation of the study.

The evaluation included both general recall-based items and reasoning-intensive clinical scenarios. This design preserved the natural distribution of difficulty and formats, including A1–B1 question types, to reflect the authentic complexity of the NMLE. All materials originated from official national examination authorities or formally verified public repositories.

Additionally, to compare the reasoning differences and performance strengths and weaknesses between the two models, we randomly selected 200 questions for prompt comparison and representative case analysis.

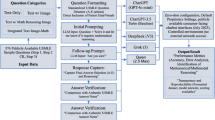

Models and prompting protocol

ChatGPT-4o

OpenAI’s general-purpose GPT-4o model (API version gpt-4o-2025–03) was used without any domain-specific fine-tuning. All outputs were generated via the official ChatGPT-4o web interface (https://chat.openai.com), using the GPT-4o model.

DeepSeek-R1

A reinforcement learning–enhanced model developed by DeepSeek, released in February 2025. Model outputs were obtained through the official platform (https://platform.deepseek.com), using the publicly available R1 version.

Prompting procedure

Both models were prompted using the same standardized instruction:

"As a board-certified medical expert, provide evidence-based answers to these licensing exam questions following current clinical guidelines. If the question involves clinical reasoning, adhere to established medical guidelines. For pharmacology-related questions, apply pharmacological principles. For pediatrics or surgery-related questions, follow appropriate clinical protocols. Provide concise, precise answers."

In the prompt comparison section, we introduced two additional prompt variations to investigate their influence on the models’ performance:we conducted an ablation study on a 200-question subset.

Step-by-step reasoning (Prompt 2):

“You are a licensed physician. Carefully analyze the following licensing exam question step by step. First, identify the key clinical information in the question. Second, explain the reasoning process by applying medical guidelines and principles. Finally, provide the single best answer choice. Ensure your reasoning is explicit before stating the final answer.”

Concise answer-only (Prompt 3):

“Answer the following medical licensing exam question with the single best choice only. Do not provide explanation or reasoning.”

All interactions were conducted via web interfaces only. The baseline interaction took place in March 2025, while interactions for the other two prompts were completed in September 2025. No external plugins, APIs, or toolkits were used. Chain-of-thought prompting was not employed unless explicitly specified.

Error classification

In our in-depth analysis of the performance of DeepSeek-R1 and ChatGPT-4o, we categorized their errors into two types: fact-based recall errors and diagnostic reasoning errors. Below, we discuss each error type and provide representative case analyses to clearly compare the strengths and weaknesses of both models.

Importance of diagnostic reasoning errors

Diagnostic reasoning errors refer to the failure of a model to accurately analyze and reason through the relationships between symptoms, medical history, physical findings, and test results when handling clinical cases, leading to incorrect diagnostic judgments. We chose to classify this type of error separately for the following reasons:

Core to Clinical Decision Making: Diagnostic reasoning is a key element in medical practice. Physicians must make accurate judgments when faced with complex cases. One of the primary goals of AI models is to simulate the reasoning process of doctors; therefore, any errors in diagnostic reasoning directly impact the clinical application value of the model.

Significant Impact of Errors: Diagnostic reasoning errors can lead to incorrect diagnoses, which may in turn result in improper treatment plans and negatively affect patient health. Such errors have a profound impact on clinical practice and patient care.

Key Indicator of Model Evaluation: Diagnostic reasoning errors serve as a direct reflection of how well the model performs in complex medical reasoning tasks. This type of task requires the model to integrate multi-dimensional medical knowledge for analysis, which is a core competency in the application of AI in healthcare.

Independence of fact-based recall errors

Fact-based recall errors occur when a model fails to accurately remember or apply fundamental medical facts, such as disease diagnostic criteria, drug dosages, or common symptoms. The reasons for categorizing this error type separately are as follows:

Foundational Nature of Medical Knowledge: Fact-based recall is the foundation of medical decision-making. Medical knowledge includes many standardized facts, such as diagnostic criteria for diseases, treatment protocols, and drug dosages. Models must accurately grasp these facts; otherwise, even if the reasoning process is correct, the final answer will deviate from the correct conclusion due to incorrect foundational knowledge.

Direct Consequences of Errors: Fact-based recall errors can lead to incorrect basic medical information, such as wrong diagnoses, treatment plans, or drug choices. These errors directly affect clinical decision-making and may pose health risks to patients. Unlike diagnostic reasoning errors, fact-based recall errors are primarily concerned with the accuracy of knowledge recall and do not involve complex reasoning processes. By classifying them separately, we can more precisely assess the model’s ability to remember and apply medical knowledge.

Simplicity and analytical depth of the classification

Classifying errors into diagnostic reasoning errors and fact-based recall errors allows for a simpler and clearer framework. This classification focuses on the model’s reasoning abilities and the accuracy of its foundational knowledge, avoiding unnecessary complexity. It helps to clearly present the model’s strengths and weaknesses. This approach allows for a deeper exploration of the model’s performance in clinical reasoning and basic knowledge application, helping to identify core issues and providing clear directions for future improvements.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using R Studio version 4.5.1 (Posit Software, PBC, 2025).

First, a two-way ANOVA was applied to compare the performance of ChatGPT-4o and DeepSeek-R1 across different years (2017–2021) and medical subjects. P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. To estimate F-statistics and partial eta-squared values, we simulated within-group variation by introducing minor perturbations to the yearly average accuracies. This approach approximated the unit-level variance originally averaged across four subject units (internal medicine, surgery, pharmacology, and pediatrics) per model per year, thereby enabling residual-based effect size estimation and improving interpretability.

In addition, to appropriately account for the binary nature of item-level responses (correct = 1, incorrect = 0), model performance was further analyzed using a generalized linear mixed model (GLMM) with a logit link. The model included fixed effects for model type (ChatGPT-4o vs. DeepSeek-R1), year (2017–2021), unit, as well as the interaction between model type and year. Each question was modeled with a random intercept (1 | question_id) to account for item-level variability.

Post-hoc pairwise comparisons were conducted using the emmeans package in R (v4.5.1), and odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals were reported. Model diagnostics, including posterior predictive checks, binned residuals, and collinearity assessment, were conducted using DHARMa and performance packages. The GLMM analysis was performed to complement the ANOVA results and to rigorously account for item-level binary outcomes.

Results

Appendix Tables 1 and 2 show the accuracy of ChatGPT-4o and Deepseek-R1 on NMLE questions. The data is grouped by unit and year from 2017 to 2021. Deepseek-R1 gets higher accuracy than ChatGPT-4o. Its scores are especially high in 2020 and 2021. In 2017, ChatGPT-4o’s accuracy is lower. For example, Unit 3 is 46.00% and the average is 52.33%. In the same year, Deepseek-R1 gets 90.00% in Unit 1. It keeps high scores in other years too. In 2020, Unit 2 reaches 96.67%. Deepseek-R1 has stable performance in each year. ChatGPT-4o shows more changes in its scores.

The detailed performance data is summarized visually in Fig. 3. (Appendix Tables 1 and 2, which provide detailed unit-by-unit accuracy, are available in the Supplementary Appendix).

A two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted to assess the effects of model (ChatGPT-4o vs. DeepSeek-R1) and year (2017–2021) on answer accuracy.

The results revealed significant main effects of model (F(1,26) = 1653.64, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.98) and year (F(4,26) = 19.05, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.42), as well as a moderate model–year interaction (F(4,26) = 5.77, p = 0.024, η2 = 0.18).

These results confirm that model type plays a dominant role in performance, with DeepSeek-R1 consistently outperforming ChatGPT-4o across all years and subject areas.

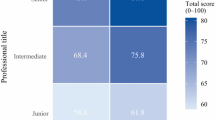

Figure 1 presents the annual performance of ChatGPT-4o across four subject units, highlighting considerable year-to-year variability, especially in Unit 3 during earlier years. Figure 2 shows Deepseek-R1’s performance under the same conditions, where the model consistently maintained high accuracy across all units and years. Figure 3 provides a direct comparison of the average annual accuracy between the two models, clearly illustrating the performance gap, with Deepseek-R1 demonstrating stronger and more stable outcomes over time.

As shown in Fig. 1, ChatGPT-4o’s accuracy varied across clinical units and years, with Units 1 and 3 exhibiting relatively lower proportions of correct answers compared to Units 2 and 4. Notably, Unit 1 showed a visible drop in accuracy from 2017 to 2019, followed by a moderate recovery. The results suggest unit-specific challenges in question answering, highlighting potential differences in content complexity or model limitations in certain domains.

In Fig. 2, Deepseek-R1 achieved consistently high accuracy across all four clinical units and years, with most units showing over 85% correct responses throughout the evaluation period. Compared to ChatGPT-4o (Fig. 1), Deepseek-R1 demonstrated significantly lower error rates, especially in Unit 1 and Unit 3, suggesting improved robustness in domains previously identified as challenging.

Figure 3 summarizes the overall performance comparison between ChatGPT-4o and DeepSeek-R1 from 2017 to 2021. DeepSeek-R1 consistently outperformed ChatGPT-4o across all years, achieving high average accuracy (approaching 95%) with minimal variance. In contrast, ChatGPT-4o’s performance fluctuated around 55–65%, with relatively larger standard deviations. These findings corroborate the trends observed in Figs. 1 and 2, highlighting the superior consistency and generalization capacity of DeepSeek-R1 across multiple clinical domains and years.

Generalized linear mixed model (GLMM) analysis

This table presents fixed-effect estimates from the generalized linear mixed model (GLMM) assessing the impact of model type (ChatGPT-4o vs. DeepSeek-R1), exam year, and subject unit on the probability of correctly answering Chinese NMLE questions. DeepSeek-R1 significantly outperformed ChatGPT-4o overall (β = − 1.829, p < 0.001). Compared to the 2017 baseline, ChatGPT-4o’s performance decreased significantly in 2019–2021 (p < 0.05) (see Table 1 for detailed GLMM results).

Among subject units, Unit 3 showed the most favorable outcome (β = 0.344, p = 0.001). A significant interaction was observed in 2020 (p = 0.009), indicating an amplified performance gap between the two models that year. All estimates are based on log-odds; negative coefficients indicate higher predicted accuracy. Compared to Unit 1 (reference), Unit 3 showed a significantly higher predicted accuracy (β = 0.344, p = 0.001), indicating the best overall performance among subject units.

To assess the robustness of the GLMM specified as correct ~ model * year + unit + (1 | question_id), we conducted a series of diagnostic checks. As shown in Fig. 4, the model fit is statistically valid and interpretable.

Posterior predictive checks indicate that the predicted probability intervals closely align with the observed distribution of correct responses, suggesting the model effectively captures key structural variations. Binned residual plots further confirm a good fit: most binned averages lie within the expected confidence bands, with only slight deviation at higher predicted probabilities.

Residual distributions approximate uniformity, with no evidence of overdispersion or influential outliers. All fixed-effect terms present acceptable multicollinearity levels, with Variance Inflation Factors (VIFs) consistently below the critical threshold of 10. The random intercepts associated with question_id display an approximately normal distribution, validating the assumption of normally distributed random effects.

Together, these diagnostics support the appropriateness of the GLMM specification and lend confidence to subsequent statistical inferences regarding the effects of model type, year, and unit on prediction accuracy.

In the Influential Observation Figure, the blue points represent the model’s predicted results, while the green points represent the actual observed data. The closeness between the green and blue points reflects the accuracy of the model’s predictions. In most cases, DeepSeek-R1 and ChatGPT-4o show a close match between the predicted and actual data, especially in fact-based recall questions. However, there are some data points that exhibit significant deviations, which are identified as outliers. These deviations often occur in multi-step reasoning questions (such as diagnostic reasoning tasks), indicating errors in the model’s reasoning that lead to discrepancies in its predictions.

Odds ratios (ORs) were estimated using a generalized linear mixed model (GLMM) with a logit link, controlling for year and subject effects and including question ID as a random intercept. Values greater than 1 indicate a significantly higher likelihood of incorrect responses from ChatGPT-4o relative to DeepSeek-R1. Across all five years (2017–2021), DeepSeek-R1 consistently and significantly outperformed ChatGPT-4o (all p < 0.0001). The largest performance disparity occurred in 2020 (OR = 11.63), suggesting that ChatGPT-4o was over 11 times more likely to generate an incorrect answer compared to DeepSeek-R1. This finding aligns with observed trends in model stability and reasoning depth and supports the superior diagnostic inference capabilities of reinforcement-tuned models like DeepSeek-R1 (see Table 2 for pairwise odds ratios across years).

As shown in Fig. 5, each point represents the estimated odds ratio for a given year, with vertical lines showing 95% confidence intervals based on a generalized linear mixed model (GLMM) with a logit link. ORs greater than 1 suggest that ChatGPT-4o was more likely to answer incorrectly than DeepSeek-R1. In all five years, the ORs remained significantly above 1, indicating consistent underperformance of ChatGPT-4o relative to DeepSeek-R1. The disparity peaked in 2020 and remained high in 2021, reflecting a widening performance gap.

According to Fig. 6, we can see the predicted probabilities of correct answers for ChatGPT-4o and DeepSeek-R1 across 2017–2021, as estimated by the GLMM. Each black dot corresponds to the model’s mean predicted accuracy for that year, while the purple horizontal bars represent 95% confidence intervals. DeepSeek-R1 consistently shows higher predicted accuracy than ChatGPT-4o in all years.

The largest performance gap appears in 2020, where DeepSeek-R1 reaches its peak predicted probability while ChatGPT-4o remains substantially lower. ChatGPT-4o demonstrates moderate inter—year variability, while DeepSeek-R1 maintains a more stable high performance. The non-overlapping confidence intervals in most years indicate that the performance difference between the two models is statistically significant.

Model reasoning logic comparison

In Fig. 7, we selected a representative diagnostic analysis question to demonstrate the differing reasoning approaches of ChatGPT-4o and DeepSeek-R1 by using Step-by-step reasoning prompt (Prompt 3). This case is a typical "multidisciplinary knowledge integration" question, which involves three core medical disciplines in the NMLE: diagnostics (fundamental supporting discipline), surgical sciences—orthopedics (core clinical discipline), and internal medicine—infectious diseases and rheumatology (supplementary disciplines). The primary objective of this question is to assess the practitioner’s ability to integrate clinical information into an accurate diagnosis, which is one of the essential foundational skills in clinical practice.

Through the comparison of diagnostic reasoning paths between DeepSeek-R1 and ChatGPT-4o, we observe the following:

ChatGPT-4o’s Diagnostic Pathway:

Step 1: Identifying Key Clinical Information: ChatGPT-4o recognizes the patient’s chronic knee pain, low-grade fever, and relevant physical findings (e.g., muscle atrophy, spindle-shaped knee swelling).

Step 2: Considering Multiple Possible Diagnoses: The model considers differential diagnoses such as osteoarthritis, septic arthritis, and chronic osteomyelitis, but lacks detailed reasoning about the absence of bone destruction or hyperplasia, which is important in ruling out osteosarcoma.

Step 3: Reasoning Process: ChatGPT-4o focuses on broad symptom categories like inflammation but doesn’t consider the complexity of the patient’s clinical history and multi-disciplinary nature of the question.

DeepSeek-R1’s Diagnostic Pathway:

Step 1: Detailed Clinical Analysis: DeepSeek-R1 accurately integrates the patient’s symptoms (chronic course, low-grade fever, spindle-shaped knee swelling) with underlying pathophysiology, associating it with chronic inflammatory conditions, such as tuberculosis.

Step 2: Focused Differential Diagnosis: DeepSeek-R1 emphasizes specific findings, like the absence of bone hyperplasia (ruling out osteoarthritis) and notes that the lack of leukocytosis makes septic arthritis less likely.

Step 3: Reasoning Process: The model correctly identifies that the key clinical information suggests knee joint tuberculosis, a diagnosis supported by the combination of chronic disease progression, non-destructive osteopathy on X-ray, and elevated ESR.

Diagnostic analysis: impact of prompts on error types

While Table 3 demonstrates that a performance gap exists, this section provides a diagnostic analysis of why it exists. We conducted an ablation study on a 200-question subset (randomly sampled from 2021) to test how prompt design influences performance and error types. The 2021 dataset was chosen as it presented significant cross-disciplinary complexity.

Table 3 reveals a critical finding: ChatGPT-4o’s performance is highly sensitive to prompt structure. When forced to use "Step-by-step reasoning" (Prompt 2), its accuracy dramatically increased by 24.5% (from 63.5 to 88.0%). In contrast, DeepSeek-R1’s performance, already high, saw only a minor 2.5% gain.

To diagnose the cause of this discrepancy, we analyzed a representative sample of errors from this subset, classifying them according to our methodology (Table 4).

In Table 4, it is evident that the accuracy of DeepSeek-R1 across different prompt types shows minimal variation. Specifically, the accuracy for the Baseline prompt is 93.5%, while Prompt 2 and Prompt 3 result in accuracy rates of 96% and 95.5%, respectively. This suggests that, despite the use of more detailed reasoning or concise answer prompts, the performance of DeepSeek-R1 does not differ significantly across these conditions.

Similarly, ChatGPT-4o shows a similar trend, with Prompt 2 achieving an accuracy of 88%, and Prompt 3 yielding an accuracy of 77.5%. While the detailed reasoning prompt (Prompt 2) slightly improves accuracy, the overall difference remains relatively small.

This qualitative analysis provides the diagnostic explanation for the quantitative gap (Table 3). The sample shows that ChatGPT-4o’s baseline errors (e.g., Q14, Q20a, Q53, Q117a, Q117b) are frequently Diagnostic reasoning errors.

Crucially, these are the exact types of errors that are significantly corrected when the model is forced to use the "Step-by-step reasoning" (Prompt 2) prompt. This strongly suggests that ChatGPT-4o’s primary deficit is not a lack of medical knowledge, but rather a failure to spontaneously apply multi-step diagnostic reasoning to complex cases. It defaults to a “fast thinking” mode, leading to reasoning failures.

DeepSeek-R1, conversely, appears to utilize a more robust reasoning pathway by default, aligning with its design. Its baseline performance already reflects this, which is why Prompt 2 offers only marginal improvement. This analysis, therefore, moves beyond a descriptive “what” (DeepSeek-R1 is better) to a diagnostic “why” (because ChatGPT-4o fails to apply reasoning unless explicitly prompted to do so).

Discussion

The findings show the challenges faced by medical students in preparing for the exam. With the need for better study tools, Given the increasing need for effective study tools, large language models such as DeepSeek-R1 and ChatGPT-4o may assist learners in exam preparation and clinical reasoning development.

Interestingly, Unit 3 exhibited the highest predicted accuracy among all subject units, as indicated by its significantly positive fixed effect in the GLMM analysis (β = 0.344, p = 0.001). Several factors may explain this observation. First, pharmacology questions, which dominate Unit 3, often feature highly structured content with consistent formats and clear diagnostic anchors, making them more amenable to pattern recognition by large language models. Second, pharmacological knowledge tends to be more systematic and mechanistic, allowing models to leverage memorized rules (e.g., drug classes, mechanisms of action, side-effect profiles) rather than relying solely on nuanced clinical reasoning. Third, compared to units involving pediatrics or internal medicine, Unit 3 questions generally require shorter reasoning chains and present fewer distractors, which may reduce ambiguity and cognitive load during model inference. These characteristics align well with the capabilities of instruction-tuned language models like DeepSeek-R1 and may account for its superior performance on pharmacology-related tasks.

In language learning, DeepSeek-R1 is better at finding context-driven errors, while ChatGPT-4o is better at providing useful feedback21. This shows that both models have strengths. DeepSeek-R1 is better at reasoning and clinical decision-making, while ChatGPT-4o is better at providing clear explanations, especially for non-case-related topics.

Despite occasional lower accuracy, ChatGPT-4o may contribute greater pedagogical clarity in certain instructional settings, which could be beneficial in medical education contexts. This trade-off between correctness and communicability merits further analysis. Error analysis revealed that ChatGPT-4o frequently failed in multi-step diagnostic reasoning, particularly in Unit 3 questions involving pharmacological contraindications. DeepSeek-R1, while more accurate, occasionally generated overconfident responses unsupported by clinical evidence. These patterns highlight the importance of error transparency in clinical applications.

In addition to performance evaluation, we observed how both models may serve as educational tools that enhance diagnostic thinking. For complex, case-based examinations like the NMLE, stepwise reasoning and contextual interpretation are essential. Notably, both ChatGPT-4o and DeepSeek-R1 provided not just answers but also accompanying explanations. For example, in pediatric diagnostic questions, such as those involving febrile rash syndromes, both models demonstrated temporal reasoning by linking the timing of fever resolution with the appearance of rash—mirroring the clinical logic used to distinguish between roseola, measles, and other exanthematous illnesses. These explanations allow students to understand not only the correct option but also the rationale behind it, potentially strengthening clinical reasoning skills. This aligns with cognitive apprenticeship theory, where expert-like reasoning is modeled to help learners internalize domain thinking22, and also with the educational principle of “visible thinking,” which emphasizes making mental processes explicit to promote deeper learning23.

Furthermore, these AI tools offer an accessible and cost-free learning alternative for students in under-resourced settings. While many commercial question banks in China lack detailed answer explanations or restrict access behind paywalls models like DeepSeek-R1 are openly available and free to use. This accessibility may be especially valuable for students from rural hospitals or smaller institutions who cannot afford expensive review materials. By offering transparent reasoning and consistent feedback, such models can serve as surrogate mentors in independent learning settings24, contributing to greater educational equity in medical training. While we do not suggest that AI tools replace traditional instruction, their integration can support self-regulated learning and complement conventional study strategies.

In recent years, the shift toward Competency-Based Medical Education (CBME)25,26 has emphasized diagnostic reasoning and clinical decision-making over rote memorization. Our findings resonate with this trend, as both DeepSeek-R1 and ChatGPT-4o exhibit capabilities that align with reasoning-focused assessments in the NMLE. Particularly, the structured explanations generated by these models may serve as formative assessment tools, offering learners immediate feedback on clinical logic and common diagnostic pitfalls. Such model behavior supports not only knowledge reinforcement but also metacognitive reflection, which is central to CBME and effective clinical training27.

Unlike commercial question banks that often provide limited explanations, LLMs like DeepSeek-R1 can simulate expert-like reasoning processes, supporting independent, feedback-driven learning in low-resource environments. Learners can interact with the model by posing follow-up questions on related concepts, prompting the generation of extended explanations that clarify clinical logic, explore alternative diagnoses, or elaborate on pharmacological mechanisms. This interactive capacity transforms static assessment into a dynamic learning experience, fostering deeper conceptual understanding and adaptive reasoning.

In addition to explanation clarity, ChatGPT-4o also demonstrates practical advantages in educational use. Its response speed is generally faster than DeepSeek-R1, which may improve the efficiency of learner interaction during self-study. Especially in high-volume question practice or time-constrained review settings, the ability to receive immediate feedback can enhance user engagement and support iterative learning. While DeepSeek-R1 excels in reasoning accuracy, ChatGPT-4o’s communicative fluency, user responsiveness, and lower latency contribute meaningfully to its usability in formative learning environments. These features make ChatGPT-4o a potentially valuable companion tool for medical students, particularly in early-stage concept reinforcement or real-time Q&A.

Despite their potential, AI models also raise ethical concerns, particularly in clinical education and decision-making settings. One notable issue is hallucination28, where the model produces answers that appear plausible but are factually incorrect. Without appropriate supervision29, such outputs may mislead learners and contribute to false confidence. A deeper concern lies in the absence of human empathy, moral reasoning, and contextual sensitivity that experienced medical educators naturally provide. Although the scalpel itself is a neutral instrument, the guidance imparted to those who use it must reflect ethical care and professional responsibility.

A key finding of this study is that the performance gap can be largely attributed to fundamental architectural differences. DeepSeek-R1 is an architecture explicitly optimized for reasoning, while GPT-4o is a general-purpose, multimodal model designed for broad conversational fluency. Our evaluation was not intended as a symmetric benchmark of pure reasoning engines, but rather as a practical assessment of the performance of currently available public interfaces for medical education.

Crucially, our prompt-based diagnostic analysis (Tables 3 and 4) quantifies the tangible impact of this architectural difference. The 24.5% performance increase for ChatGPT-4o when shifted from a baseline prompt to a step-by-step reasoning prompt is critical. It strongly suggests its “generalist” architecture defaults to a conversational, "fast-thinking" mode, possessing the underlying knowledge (achieving 88% accuracy in step-by-step reasoning) but failing to spontaneously apply complex reasoning until prompted. DeepSeek-R1’s minimal 2.5% gain, in contrast, indicates its "reasoning-optimized" architecture already operates in this structured, multi-step manner by default.

Furthermore, this architectural advantage is likely compounded by linguistic and domain-specific alignment. DeepSeek-R1 is a Chinese-developed model with documented optimization for Chinese-language tasks. This linguistic "home-field" advantage likely provides a substantial benefit in understanding the nuances and terminology of the Chinese NMLE, whereas GPT-4o’s English-centric training may compromise its parsing of these high-stakes, non-primary language scenarios.

We also observed that although ChatGPT-4o’s stability slightly lags behind DeepSeek-R1, its response time is much faster under the same network conditions, primarily due to the time required for token generation during reasoning. A key advantage of DeepSeek-R1, as a reasoning model, lies in its ability to address the “black box” problem of large language models (LLMs)30 by providing detailed reasoning pathways. This feature allows for both the accuracy of answers and the reasoning process to be clearly understood, providing valuable insights for learners. By following the model’s reasoning, we can evaluate its solutions and identify the errors in thinking or knowledge that led to incorrect outcomes31. Even when using the simpler concise prompt, DeepSeek-R1 still performs detailed medical diagnostic reasoning due to its model parameters. However, it is important to note that, like all large language models, DeepSeek-R1 still suffers from hallucinations and randomness. These errors require substantial human intervention for correction.

The findings related to temporal performance—namely, the decline of ChatGPT-4o versus the apparent stability of DeepSeek-R1—should be interpreted with caution. This observation highlights the importance of temporal robustness in model deployment. However, further investigation is needed to account for potential confounding factors. Variations in question difficulty or shifts in language biases and topics from year to year could also influence these performance trends, rather than solely reflecting changes in the models’ core capabilities.

Conclusion

First, the benchmarking results are decisive: DeepSeek-R1 consistently and significantly outperformed ChatGPT-4o on the Chinese NMLE across the 2017–2021 datasets. While DeepSeek-R1 maintained stable, high-level accuracy, ChatGPT-4o’s performance was not only lower but also demonstrated a significant decline, highlighting potential issues with temporal robustness.

Second, regarding educational potential, the findings illustrate both the promise and the current limitations of LLMs. The superior performance of DeepSeek-R1 suggests that models specifically tuned for reasoning and aligned with the target language (Chinese) hold considerable potential as supplementary tools for medical training. However, as noted in our limitations, high accuracy is not synonymous with reliable reasoning or educational utility. The lack of expert human evaluation in this study means that the quality of the models’ justifications and the prevalence of hallucinations remain unverified.

In conclusion, while current models demonstrate promising results, further fine-tuning and—more critically—rigorous, qualitative, human-led assessments are necessary before these tools can be safely integrated into clinical education. This study establishes the NMLE as a robust benchmark for future AI development and underscores the critical need for developing trustworthy AI-assisted medical decision support tools.

Limitations

This study has several limitations, which we plan to address in future research.

First, the exclusive use of multiple-choice questions may not fully capture the models’ reasoning depth and explanatory capabilities. To mitigate this, future studies will incorporate open-ended questions and require models to provide rationale-based justifications, enabling a more nuanced assessment of their cognitive and generative abilities.

Second, while accuracy offers a clear quantitative benchmark, it does not reflect the quality, consistency, or reliability of the underlying reasoning processes. In subsequent work, we will introduce consistency metrics, rationale quality scoring, and multi-trial evaluations to better understand model behavior across varied contexts.

Third, all inputs in the current study were presented in Chinese, which may have introduced a linguistic bias potentially favoring DeepSeek-R1. To enhance cross-lingual generalizability, future experiments will adopt multilingual settings to evaluate robustness across diverse language inputs.

A primary limitation is that this study did not include an evaluation by human experts of the reasoning process, hallucinations, or argument quality. Future research should involve medical education experts to manually annotate the reasoning quality and error types of model outputs, which would provide more comprehensive support for conclusions regarding educational applications.

Moreover, DeepSeek-R1 and ChatGPT-4o differ fundamentally in terms of architecture and tuning objectives, which may inherently influence their task-specific performance. Future work will attempt to account for these differences, possibly through controlled comparisons or architectural ablation studies.

The models’ performance is potentially influenced by yearly variations in the structure and difficulty of the examination questions. For instance, DeepSeek-R1 achieved an extremely high accuracy of 96.67% on Unit 2 in 2020, but its performance dropped to 84% in 2021. This difference could be attributed to changes in question difficulty, as the 2021 questions were more complex and involved cross-disciplinary knowledge integration (such as combining pharmacology and diagnostics). Furthermore, the delay in updating the knowledge base could have contributed to the performance drop, as medical exams often reflect the latest clinical guidelines and practices. If DeepSeek-R1’s training data did not include recent updates, such as new drug guidelines or disease classification changes, it might lead to discrepancies when answering 2021 questions, thereby affecting overall performance.

Due to the increase in prompt types, we were unable to conduct research in parallel across all models within the same timeframe. This might have led to repeated training on the database, potentially influencing the results. To address this, future research will ensure more synchronized testing across different prompts. Furthermore, the prompt design used in this study was not exhaustive. Future studies will continuously refine and optimize prompt designs to achieve higher accuracy in model responses.

Lastly, this study focused only on single-response evaluations. We recognize the importance of analyzing model stability, response diversity, and reasoning consistency over multiple trials, and will incorporate such analyses in our ongoing and future work.

Data availability

The Chinese National Medical Licensing Examination (NMLE) questions used in this study were obtained from open-access repositories and institutional archives. These materials are publicly available and have been used in prior peer-reviewed studies for evaluating language model performance. No proprietary data was involved. Since the current research was conducted entirely via manual interaction with public web interfaces of the models, no custom code was used or generated.

References

Xu, L., Sanders, L., Li, K. & Chow, J. C. Chatbot for health care and oncology applications using artificial intelligence and machine learning: Systematic review. JMIR Cancer. 7(4), e27850 (2021).

Haleem, A., Javaid, M., Qadri, M. A., Singh, R. P. & Suman, R. Artificial intelligence (AI) applications for marketing: A literature-based study. Int. J. Intell. Netw. 3, 119–132 (2022).

Zawacki-Richter, O., Marín, V. I., Bond, M. & Gouverneur, F. Systematic review of research on artificial intelligence applications in higher education–Where are the educators?. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High Educ. 16(1), 1–27 (2019).

Schulman, J., Zoph, B., Kim, C., Hilton, J., Menick, J., Weng, J., et al. ChatGPT-4o: Optimizing language models for dialogue. OpenAI Blog https://openai.com/blog/chatgpt/. 2(4) (2022).

Shen, Y. et al. ChatGPT and other large language models are double-edged swords. Radiology 307(2), e230163 (2023).

Goar, V., Yadav, N. S. & Yadav, P. S. Conversational AI for natural language processing: A review of ChatGPT. Int. J. Recent Innov. Trends Comput. Commun. 11(3s), 109–117 (2023).

Nazir, A. & Wang, Z. A comprehensive survey of ChatGPT: Advancements, applications, prospects, and challenges. Meta-Radiology. 1(2), 100022 (2023).

Wang, X. et al. ChatGPT performs on the Chinese national medical licensing examination. J. Med. Syst. 47(1), 86 (2023).

Zong, H. et al. Performance of ChatGPT on Chinese national medical licensing examinations: a five-year examination evaluation study for physicians, pharmacists and nurses. BMC Med. Educ. 24(1), 143 (2024).

Wang, Y. M., Shen, H. W. & Chen, T. J. Performance of ChatGPT on the pharmacist licensing examination in Taiwan. J. Chin. Med. Assoc. 86(7), 653–658 (2023).

Hsieh, C. H., Hsieh, H. Y. & Lin, H. P. Evaluating the performance of ChatGPT-3.5 and ChatGPT-4 on the Taiwan plastic surgery board examination. Heliyon 10(14), e34851 (2024).

Guo, D., Yang, D., Zhang, H., Song, J., Zhang, R., Xu, R., et al. Deepseek-R1: Incentivizing reasoning capability in LLMs via reinforcement learning. arXiv. 2025;2501.12948.

Christiano, P. F., Leike, J., Brown, T., Martic, M., Legg, S., & Amodei, D. (2017). Deep reinforcement learning from human preferences. In Advances in neural information processing systems, vol. 30.

Ouyang, L. et al. Training language models to follow instructions with human feedback. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 35, 27730–27744 (2022).

Arrieta, A., Ugarte, M., Valle, P., Parejo, J.A., Segura S. o3-mini vs DeepSeek-R1: Which one is safer? arXiv. 2025;2501.18438.

National Medical Examination Center. Common Questions and Answers about the 2024 Edition of the National Medical Licensing Examination Syllabus. Beijing, China: National Medical Examination Center; 2023.Available from: https://www.nmec.org.cn/website/newsinfo/72712 (in Chinese).

Luo, D. et al. Evaluating the performance of GPT-3.5, GPT-4, and GPT-4o in the Chinese national medical licensing examination. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 14119 (2025).

Chen, H. et al. Feedback is all you need: From ChatGPT to autonomous driving. Sci. China Inf. Sci. 66(6), 1–3 (2023).

Parmar, M., & Govindarajulu, Y. Challenges in ensuring ai safety in deepseek-r1 models: The shortcomings of reinforcement learning strategies. arXiv preprint arXiv:2501.17030 (2025).

Fang, C. et al. How does ChatGPT-4 preform on non-English national medical licensing examination? An evaluation in Chinese language. PLOS Dig. Health 2(12), e0000397 (2023).

Mahyoob, M., Al-Garaady, J. DeepSeek vs. ChatGPT-4o: comparative efficacy in reasoning for adults’ second language acquisition analysis. SSRN. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.12345678 (2025).

Roll, I. & Wylie, R. Evolution and revolution in artificial intelligence in education. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Educ. 26(2), 582–599 (2016).

Ritchhart, R., Church, M. & Morrison, K. Making thinking visible: How to promote engagement, understanding, and independence for all learners (John Wiley & Sons, 2011).

Holmes, W., Bialik, M., & Fadel, C. (2019). Artificial intelligence in education promises and implications for teaching and learning. Center for Curriculum Redesign.

Frank, J. R. et al. Competency-based medical education: Theory to practice. Med. Teach. 32(8), 638–645 (2010).

Shah, N., Desai, C., Jorwekar, G., Badyal, D. & Singh, T. Competency-based medical education: An overview and application in pharmacology. Indian J. Pharmacol. 48(Suppl 1), S5 (2016).

Harris, P., Snell, L., Talbot, M., Harden, R. M., International CBME Collaborators. Competency-based medical education: Implications for undergraduate programs. Med. Teach. 32(8), 646–650 (2010).

Huang, L. et al. A survey on hallucination in large language models: Principles, taxonomy, challenges, and open questions. ACM Trans. Inf. Syst. 43(2), 1–55 (2025).

Wang, Y., Li, H., Han, X., Nakov, P., & Baldwin, T. Do-not-answer: Evaluating safeguards in LLMs. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EACL 2024, 896–911 (2024).

Wang, Y., Ma, X., & Chen, W. Augmenting black-box llms with medical textbooks for biomedical question answering (published in findings of EMNLP 2024). arXiv preprint arXiv:2309.02233 (2023).

Moëll, B., Sand Aronsson, F. & Akbar, S. Medical reasoning in LLMs: An in-depth analysis of DeepSeek R1. Front. Artif. Intell. 8, 1616145 (2025).

Funding

This research is funded by the Shanghai Municipal Health Commission (2024WF03), Shanghai Association of Chinese Integrative Medicine(2025-SQ-24),Sichuan Medical Law Research Center and the China Health Law Society (YF25-Q12).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.W.,Z.L., B.Z. Y.C and H.T contribute equal in this study. X.W. conceived the study design, conducted data analysis, and drafted the main manuscript text. Z.L., B.Z. and Y.C. collected and processed the examination data. H.T. contributed to statistical modeling and visualization. S.Z. and K.H. supervised the project, reviewed all analyses, and revised the manuscript critically for intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics, consent to participate, and consent to publish

Not applicable. This study did not involve human subjects or personal data. The exam questions were obtained from publicly accessible repositories and have been previously utilized in peer-reviewed research.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, X., Long, Z., Zhu, B. et al. Evaluation of DeepSeek-R1 and ChatGPT-4o on the Chinese national medical licensing examination: a multi-year comparative study. Sci Rep 16, 2237 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31874-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31874-6