Abstract

This study evaluates China’s Carbon Neutrality Capacity (CNC) from 2011 to 2022, focusing on carbon reduction capacity and carbon removal capacity, within the framework of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Using an improved entropy-weighted TOPSIS method, CNC is assessed in alignment with key SDGs, including SDG 7, SDG 12, SDG 13, SDG 9, and SDG 15. The study analyzes regional disparities and spatiotemporal evolution of CNC using methods such as the Dagum Gini coefficient, Markov chain analysis, kernel density estimation, and spatial econometric models. The results show steady improvement in China’s CNC, with faster growth in carbon removal capacity, driven by ecological restoration and carbon capture technologies. However, significant regional disparities remain, with the Northern, Eastern, and Southern Coastal Regions leading, while the Northwest and the Middle Reaches of the Yellow River lag behind. Spatial analysis reveals a concentration of high-CNC regions and limited improvement in low-CNC regions. Markov chain analysis uncovers a “lock-in effect” in low-CNC areas and a “club effect” in high-CNC areas. Spatial spillover effects show negative impacts within 100–600 km and positive impacts beyond 700 km, driven by resource competition and technology diffusion. Based on these findings, the study proposes policy recommendations, such as promoting regional equity, accelerating low-carbon innovation, and enhancing cross-regional cooperation, all aligned with the SDGs, offering practical guidance for achieving carbon neutrality in China and other developing countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Global climate change has become one of the most pressing environmental challenges facing the world today. According to data from the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change global temperatures are rising at a rate exceeding 1.5 °C, posing a severe threat to ecosystems, public health, and the sustainable development of the global economy1. As the world’s largest developing country and the largest emitter of greenhouse gases, China plays a crucial role and bears significant responsibility in global climate governance. In 2020, the Chinese government set the strategic goals of achieving carbon peaking by 2030 and carbon neutrality by 20602. This commitment not only demonstrates China’s determination to actively participate in global climate action but also reflects its strategic decisions to promote economic transformation and green development. However, in the context of regional development imbalances, how to effectively achieve this ambitious carbon neutrality goal, particularly how to assess and optimize the carbon neutrality potential and pathways across different regions, has become a critical issue for academics and policymakers. To achieve carbon neutrality, the Chinese government has introduced a series of policy documents to promote green and low-carbon technological innovation, energy structure transformation, and industrial upgrading. For example, the “14th Five-Year Carbon Neutrality Strategy” and the “Interim Regulations on the Management of Carbon Emission Trading” propose specific measures such as promoting the green energy transition and advancing the carbon emission trading mechanism3,4. However, China is a vast country with significant economic development disparities. The energy consumption structure, industrial structure, resource endowment, and technological innovation capabilities differ markedly across regions, which presents varying levels of challenges to the achievement of the carbon neutrality goal. How to assess the carbon neutrality capability (CNC) of different regions, especially in the context of regional differences and their dynamic evolution, has become an important issue in the field of carbon neutrality research.

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) proposed by the United Nations in 2015 provide a common framework for global development, aiming to address global challenges such as poverty, environmental degradation, and inequality, thus leading the world toward a more inclusive and sustainable future. Among the 17 core goals of the SDGs, Goal 13, “Climate Action,” and Goal 7, “Affordable and Clean Energy,” are closely related to carbon neutrality and provide direction for global emission reduction and energy transformation1,5,6. The climate action goal calls for urgent measures to combat climate change, reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and enhance climate resilience, while the clean energy goal emphasizes the widespread adoption of renewable energy, improving energy efficiency, and promoting the green transformation of global energy systems7,8. Particularly, these goals emphasize the need to design flexible policies based on regional circumstances to achieve global emission reduction objectives. In resource-constrained and unevenly developed contexts, how to integrate the carbon neutrality goal with the development needs of different regions and achieve regional emission reduction targets has become an important topic in current academic research. This is closely aligned with SDG 9, which emphasizes building resilient infrastructure and promoting sustainable industrialization, and SDG 15, which focuses on protecting ecosystems and promoting sustainable land management. The role of carbon neutrality in reducing environmental degradation and fostering sustainable growth underscores the need for region-specific strategies that contribute to both SDG 12, which advocates for sustainable consumption and production, and SDG 13, reinforcing the broader climate action agenda.

Currently, research on carbon neutrality frameworks mainly focuses on the macro level. Many studies explore global pathways to carbon neutrality, emission reduction policy design, and carbon emissions in various countries and regions. For example, Eckl et al. (2025) studied the technological pathways and policy mechanisms for achieving carbon neutrality globally, highlighting the importance of global cooperation and transnational carbon markets8; Haftendorn et al. (2012) explored the impact of carbon markets on achieving emission reduction targets, analyzing the relationship between carbon pricing and policy effects9. These studies contribute to achieving SDG 7 by emphasizing energy transition and sustainable energy solutions. However, carbon neutrality is not only a technical issue but also a regional development and policy coordination issue. Pearce et al. (2015) emphasized the global perspective of carbon reduction targets and regional differences, noting that even with a unified global goal, the socio-economic structure, energy consumption patterns, and technological development levels of different regions will result in different carbon neutrality pathways10. This highlights the importance of SDG 9 and SDG 12, which underscore the need for sustainable industrialization and the adoption of cleaner, more efficient technologies. Therefore, designing flexible carbon neutrality policies tailored to the unique contexts of each region has become key, aligning with SDG 13 and SDG 15, which stress the importance of localized climate action and environmental sustainability efforts.

In China, as regional economic differences become more pronounced, the pathways for achieving carbon neutrality also exhibit distinct characteristics. Some studies have begun to focus on the regional disparities in China’s carbon neutrality and have employed spatial economics models, entropy weight TOPSIS methods, and other analytical tools to assess the CNC of different regions. For example, Jin et al. (2025) used spatial economics models to analyze the spatial differences in carbon emissions across provinces in China and proposed region-specific carbon neutrality policy recommendations11. Guo et al. (2024) used the entropy weight TOPSIS method to assess the CNC of different regions, finding that the carbon neutrality potential in eastern China is significantly higher than in the western regions12. These findings are directly relevant to SDG 7, as they highlight the energy disparities between regions and the need for more equitable energy access. As a result, existing research has not yet fully addressed how to systematically analyze the dynamic changes and interactive effects of CNC in the context of regional disparities, which is crucial for achieving SDG 9 and SDG 15, emphasizing innovation and sustainable infrastructure to address regional imbalances in carbon neutrality efforts.

While the existing literature provides preliminary frameworks for assessing China’s carbon neutrality capabilities, there are several shortcomings. First, many studies primarily focus on regional difference analysis, lacking a comprehensive consideration of the interactions among multiple factors such as energy, industry, technology, and society, which are essential for achieving SDG 7, SDG 9, SDG 12, and SDG 13. Second, most studies have not explored the dynamic changes in carbon neutrality capabilities in depth, ignoring the interaction between time and space factors. This gap hinders progress towards SDG 15 by not fully considering the evolving relationship between regional carbon neutrality and ecosystem restoration efforts. Moreover, the methods used to assess CNC often focus on static analysis and fail to effectively integrate temporal and spatial dynamics to reveal the evolving patterns of carbon neutrality capabilities across regions.

To fill existing gaps, this paper proposes a comprehensive, multidimensional framework for assessing CNC, aiming to systematically analyze regional differences in CNC and their temporal-spatial evolution characteristics. This approach is designed in alignment with SDGs, particularly SDG 7, SDG 12, SDG 13, SDG 9, and SDG 15. By focusing on regional disparities in CNC, the study highlights how improving carbon neutrality can contribute to achieving these SDGs. It first constructs a CNC evaluation framework based on the improved entropy-weighted TOPSIS method, covering multiple dimensions such as energy, industry, and technology to quantify CNC across different regions, which directly supports SDG 7 and SDG 9 by addressing energy efficiency, renewable energy adoption, and infrastructure innovation. The study then employs the Gini coefficient and its decomposition method to quantify and analyze the sources of regional CNC disparities, revealing the root causes of uneven development. Finally, dynamic models like spatial kernel density estimation, spatial Markov chain models, convergence models, and spatial spillover effect models are used to explore the temporal-spatial evolution of CNC, regional interaction effects, and spatial spillover effects, contributing to SDG 13 and SDG 15 by emphasizing climate action, the diffusion of low-carbon technologies, and ecosystem restoration efforts.

The innovations of this paper lie in the following aspects: it constructs a thorough CNC evaluation index system that integrates carbon reduction and carbon removal capabilities, covering diverse dimensions like energy, industry, and technology, offering new perspectives and methodological support for regional CNC analysis, which further advances SDG 7, SDG 12, SDG 13, SDG 9, and SDG 15 by encouraging sustainable consumption and production patterns. By combining the improved entropy-weighted TOPSIS method with the Gini coefficient and its decomposition, the paper explores regional CNC disparities in China, uncovering the deep-rooted causes of regional development imbalances, which are essential for achieving SDG 10 and SDG 9. Moreover, it utilizes dynamic models to systematically analyze CNC’s temporal-spatial evolution and regional interactions, filling gaps in dynamic analysis and spatial spillover effects in the literature, which is crucial for progressing toward SDG 13 and SDG 15. Lastly, based on theoretical insights, the paper proposes flexible and region-specific carbon neutrality policy recommendations, providing actionable guidance for both China and other developing nations working toward carbon neutrality, thus contributing to global sustainability efforts in line with the SDGs.

The remainder of this research is organized as follows: Sect. 2 introduces methods for measuring CNC, including variable selection, regional difference analysis, Spatiotemporal evolution model, and Methods for calculating spatial convergence and spatial spillover. Section 3 provides a detailed analysis of measurement results, regional differences, and spatial convergence. Section 4 summarizes findings, offers implications and discusses limitations for this study. To visually present the research framework, a flowchart of empirical steps has been created and is displayed in Fig. 1.

Research design

Study area

This study focuses on analyzing the spatial and temporal differences in Carbon Neutrality Capacity (CNC) across 30 provinces in China, examining the challenges and opportunities faced by different provinces in achieving carbon neutrality. China’s provinces exhibit significant differences in terms of economic development, energy structure, and resource endowments. Coastal regions are generally more economically developed, with stronger technological infrastructure and resource advantages, while inland and western regions face greater carbon reduction challenges, particularly in terms of industrial structure and energy transformation. For instance, Jiangxi Province, which is a typical inland region, has moderate CNC levels but faces challenges such as a single industrial structure and dependence on high-carbon energy sources13. These regional disparities highlight the varying opportunities and challenges in the low-carbon transition process across provinces, providing a multidimensional analytical perspective for this study. Through the analysis of different provinces, this study provides theoretical support for China’s carbon neutrality policies and offers valuable insights and references for other developing countries in formulating region-specific carbon reduction policies.

Construction of the CNC measurement indicator system

In the process of achieving carbon neutrality, scientifically evaluating CNC is an essential tool for measuring the progress of different regions toward carbon peaking and carbon neutrality. CNC refers to a region’s comprehensive ability to achieve carbon neutrality by reducing carbon emissions (carbon reduction capacity) and increasing carbon absorption (carbon removal capacity), involving coordinated efforts across multiple sectors. Based on the concept of CNC, this study constructs an evaluation index system centered on carbon reduction capacity and carbon removal capacity, encompassing four dimensions: production, living, ecological removal, and technological removal. This system provides a comprehensive assessment of the regional differences and potential in CNC.

The two dimensions of CNC evaluation system—carbon reduction capacity and carbon removal capacity—are closely aligned with SDGs, providing theoretical support for achieving these goals. Carbon reduction capacity corresponds to SDG 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy), SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production), and SDG 13 (Climate Action), as it is directly related to improving energy efficiency, promoting the use of clean energy, and transitioning to low-carbon production and consumption patterns, which effectively reduce carbon emissions and drive global climate action. Carbon removal capacity, on the other hand, aligns with SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure) and SDG 15 (Life on Land). The former emphasizes technological innovation, especially in the application of carbon capture, utilization, and CCUS technologies, while the latter focuses on natural ecosystems, particularly the role of forests and soils in carbon sequestration. Together, these two dimensions—carbon reduction and carbon removal—form CNC, reflecting the dual goals of reducing carbon emissions and enhancing carbon absorption. Carbon reduction capacity reduces emissions by optimizing energy structures and production models, while carbon removal capacity increases carbon sequestration through natural and technological means, thus comprehensively advancing carbon neutrality goals. Therefore, these two dimensions not only complement each other in enhancing CNC but also provide a scientific evaluation framework and practical guidance for achieving the SDGs.

Many existing studies primarily focus on carbon reduction technologies, emission reduction policy design, and static analyses of carbon emissions across different regions. For instance, some studies emphasize global or national carbon reduction pathways and policy mechanisms, exploring how emission reduction technologies and policies can facilitate the achievement of global carbon reduction targets14,15. While these studies provide valuable frameworks for global carbon reduction goals, they predominantly concentrate on static analyses of carbon reduction technologies or policies, often overlooking the spatiotemporal evolution of regional CNC. Furthermore, many of these studies emphasize carbon reduction but tend to give less attention to the equally important dimension of carbon removal capacity. In contrast, this study innovatively expands upon the traditional carbon reduction capacity framework by incorporating carbon removal capacity and applying dynamic models to explore the spatiotemporal evolution of CNC and regional interaction effects. While some studies, such as those by CHEN et al. (2023) and Zhao et al. (2024)16,17, also assess regional CNC disparities using spatial econometric models and the entropy-weighted TOPSIS method, they are largely confined to static analysis and do not sufficiently address both carbon reduction and carbon removal dimensions. In contrast, this study enriches the CNC analysis framework by introducing dynamic methods, such as spatial kernel density estimation and spatial Markov chain models, which not only reflect the current state of CNC across regions but also reveal how CNC evolves over time and space, with a particular focus on regional interaction effects. This approach provides a more comprehensive understanding of CNC and addresses the gap in existing research that predominantly focuses on either carbon reduction technologies or a single dimension of analysis.

Carbon reduction capacity primarily evaluates the ability to reduce carbon emissions in production and living sectors. In the production sector, indicators such as carbon sources from industrial carbon emission intensity, and industrial energy structure reflect the main characteristics of carbon emissions in industry, as well as their reduction potential. In the living sector, indicators such as the number of public transport vehicles per 10,000 people, per capita electricity consumption, and per capita natural gas supply highlight energy consumption and the transformation toward low-carbon behavior in daily life. These indicators comprehensively capture the critical aspects of carbon reduction in production and living sectors.

Carbon removal capacity is evaluated through ecological removal and technological removal, reflecting the potential of carbon absorption and removal in a region18. For ecological removal, indicators such as the proportion of afforestation area, the proportion of soil erosion control area, and the green coverage rate of built-up areas measure the carbon sequestration capabilities of natural ecosystems and their role in absorbing atmospheric carbon dioxide. For technological removal, indicators such as the number of patent applications for carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS), and the number and licensing rate of technology patents authorized by universities measure the contribution of technological innovation to carbon removal. These indicators highlight both the capacity of natural systems to absorb carbon and the role of technology in driving carbon removal efforts.

In summary, this index system is centered on CNC, constructing a scientific and comprehensive evaluation framework across four dimensions: production, living, ecological removal, and technological removal, with specific indicators listed in Table 1.

Research models

Improved entropy-weight TOPSIS model

The traditional entropy-weight method may result in excessively high weights for certain indicators due to their high degree of dispersion, thereby affecting the accuracy of the evaluation results. To address this issue, this study introduces the basic principles of the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP), constructing a judgment matrix by comparing the coefficients of variation of the indicators and calculating entropy values, and then assigning weights. Compared to the traditional entropy-weight method, the improved method effectively avoids the over-influence of high-dispersion indicators on weight assignment, making the distribution of weights more reasonable and precise. Additionally, the introduction of AHP ensures that the weight adjustment aligns more closely with practical conditions, enhancing the stability and scientific rigor of the model. This improvement makes the method more reliable in analyzing multi-dimensional, complex data and enables a more accurate reflection of regional CNC.

Indicator normalization processing

China’s CNC evaluation index system involves various types of detailed indicators with different units, dimensions, and magnitudes, which can affect the results of comprehensive evaluation and weighting. Therefore, it is necessary to perform dimensionless processing on the indicators. Considering that the entropy-weight method used later requires indicator values to be greater than zero, this study adopts the extreme value method to normalize the data, ensuring that the processed values fall within the range of [0,1]. The specific formula is as follows:

Calculate the coefficient of variation for the entropy-weight method

The entropy-weight method assigns specific weights to indicators based on the amount of information each indicator provides. According to the traditional entropy-weight method, the first step is to calculate the coefficient of variation. The specific calculation method is as follows:

First, calculate the characteristic proportion pij of the i-th evaluated object under the j-th indicator. The formula is as follows:

Where m represents the number of samples.

Second, Calculate the entropy value ej of the j-th indicator. The formula is as follows:

Where \(\:{I}_{ij}=\text{l}\text{n}\frac{1}{{p}_{ij}}\) represents the amount of information, \(\:{I}_{j}={\sum\:}_{i=1}^{m}\:{p}_{ij}\text{l}\text{n}\frac{1}{{p}_{ij}}\) represents the total amount of information, and \(\:{e}_{j}\) represents the entropy value.

Third, calculate the coefficient of variation gj for the j-th indicator. The formula is as follows:

Calculate the mapped values in the improved entropy-weight method

The improved entropy-weight method follows the basic principles of AHP. First, the coefficient of variation from the traditional entropy-weight method is compared, and the results are mapped to the 1–9 scale of AHP. A pairwise comparison matrix based on entropy weights is then constructed. By normalizing the matrix according to the basic AHP procedure, the weights can be obtained. The specific steps are as follows:

First, calculate the maximum coefficient of variation ratio D. The formula is as follows:

Second, calculate the mapping ratio R for the 1–9 scale and determine the mapped values of the scale. The formula is as follows:

Where a is the adjustment coefficient. If D ≤ 9, then a is the integer closest to D; ; if D > 9, then a is set to 9. According to the 1–9 scale in AHP, the mapped values required for the improved entropy-weight method can be calculated. The formula is as follows:

Third, construct the judgment matrix and calculate the weights.

The ratio of the coefficients of variation between each pair of indicators is calculated using the following formula:

The RI value closest to r is used to construct the judgment matrix. Then, according to the basic principles of the AHP method, hierarchical ranking and consistency checks are performed to obtain the final weights.

Evaluate using the TOPSIS

The Technique for Order of Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS) is a widely used objective comprehensive evaluation method that highlights the principle of distinctiveness among alternatives and the principle of free competition. It can complement methods such as the entropy-weight method by combining their strengths.

First, construct a weighted normalized matrix based on the weights determined by the entropy-weight method. The formula is as follows:

Second, calculate the optimal solution and the worst solution. For positive indicators, the optimal solution and the worst solution are as follows:

For negative indicators, the optimal solution and the worst solution are as follows:

Third, calculate the distance between each indicator and the optimal solution as well as the worst solution. The formula is as follows:

Where i = 1,2…m.

Fourth, calculate the relative closeness. The formula is as follows:

The relative closeness ci reflects the degree of closeness between the evaluated object and the optimal solution, which represents the final score.

Dagum Gini coefficient and its decomposition

The Dagum Gini coefficient and its decomposition method are used to analyze the regional differences in China’s CNC. This method can precisely reveal the disparities both between and within spatial regions. According to the research methodology of Ryu et al.19, the Dagum Gini coefficient not only measures the overall degree of disparity but, through its decomposition, provides a deeper understanding of the various factors contributing to these differences, including intra-group disparities and inter-group disparities. This approach offers an effective tool for exploring the spatial distribution characteristics and trends of CNC in a scientific and detailed manner, which is of great significance for formulating more precise and effective regional development strategies. The formula for the Dagum Gini coefficient and its decomposition is as follows:

Where G represents the overall Gini coefficient of CNC, \(\:{y}_{ij}\) represents the CNC of province j in region i, k is the number of regions, n is the number of provinces, \(\:\mu\:\) represents the mean CNC of each region, \(\:{G}_{ii}\)represents the Gini coefficient within region i, \(\:{G}_{im}\)represents the Gini coefficient between regions i and m, \(\:{D}_{im}\) represents the relative impact of CNC overlap between regions i and m, \(\:{d}_{im}\) represents the CNC difference between regions i and m, and \(\:{p}_{im}\) represents the mathematical expectation of the sum of positive sample values \(\:{y}_{mr}-{y}_{ij}\)>0 in regions i and m.

Kernel density estimation

This study adopts a combination of traditional kernel density estimation and spatial kernel density estimation methods to analyze the dynamic evolution of China’s CNC. The formula for traditional kernel density estimation is as follows:

Traditional kernel density estimation intuitively reflects the overall distribution pattern and dynamic changes of CNC but fails to account for spatial correlations20. To address this limitation, spatial kernel density estimation is introduced to analyze the spatial dependence of CNC among regions. Spatial static kernel density reveals the effects of spatial lag, while spatial dynamic kernel density focuses on the impact of CNC on future local development. This provides a scientific basis for analyzing regional disparities and optimizing policies.

Spatial kernel density estimation builds upon traditional kernel density estimation by incorporating temporal and spatial factors. Using probability density estimation, it presents the distribution characteristics of random variables under spatiotemporal conditions through a continuous density curve. The formula is as follows:

Where \(\:f(x,y)\)represents the joint kernel density function of x and y, and \(\:g(y\mid\:x)\) represents the dynamic distribution of x conditional on y. Spatial kernel density estimation can be divided into three dimensions: spatial static kernel density estimation and spatial dynamic kernel density estimation. It reveals the spatial distribution characteristics and evolutionary patterns of CNC in China. Specifically, spatial static kernel density estimation focuses on the mutual influence of CNC between cities under spatial lag conditions, while spatial dynamic kernel density estimation analyzes the impact of CNC levels in other cities in year t on the CNC levels in the local city in year t + 3.

Markov chain

The traditional Markov chain method is used to reveal the temporal evolution characteristics of CNC levels across different time periods in China. CNC is classified into four types using the quartile method, and a 4 × 4 state transition matrix is constructed to represent the transitions of different types of CNC over various periods. The formula is as follows:

Where \(\:{p}_{ij}\) represents the probability of CNC transitioning from i-type in period t to j-type in period t + 3; \(\:{n}_{ij}\) represents the number of transitions from i-type in period t to j-type in period t + 3; \(\:{n}_{i}\) represents the total number of occurrences of i-type during the sample period, as shown in Table 2.

The spatial Markov chain method is used to measure the spatial evolution characteristics of CNC in China. Lee et al.21extended the traditional Markov chain transition matrix, enabling a more comprehensive analysis of the geographic dimensions in transition dynamics. Considering the potential spatial spillover effects of CNC, the lag levels are classified based on the CNC levels of neighboring regions, as shown in Table 3.

Convergence model

The β convergence model is used to determine whether economic variables will eventually converge to a steady state and is widely applied in economic research22. Based on whether the steady-state levels are the same, β convergence is divided into two types: absolute β convergence and conditional β convergence. First, the absolute β convergence model is constructed as follows:

Where \(\:{A}_{jt}\) represents a series of influencing factors. The influencing factors are represented as follows: a1 (industrial structure) is measured by the ratio of the tertiary industry to the secondary industry; a2 (urbanization level) is represented by the proportion of urban population to the total population; a3 (economic development level) is expressed as per capita GDP using the year 2000 as the base year; a4 (degree of openness) is defined as the ratio of total imports and exports of goods to GDP; and a5 (R&D intensity) is measured by the ratio of internal R&D expenditures to GDP. Additionally, the degree of government intervention is represented by the ratio of local government general public budget expenditures to GDP.

Spatial spillover effect model

Based on tests such as the LM test and Hausman test, construct a Spatial Durbin Model (SDM) to explore whether the above-mentioned influencing factors have significant spatial spillover effects on China’s CNC, with the formula as follows:

Where \(\:{w}_{ij}\) is the spatial weight matrix. Referring to the study by Lappalainen et al.23, the economic geography spatial weight matrix is constructed using the gravity model. p is the spatial autoregressive coefficient. Meanwhile, a distance-based spatial weight matrix is constructed for robustness testing. Additionally, related scholars generally believe that as the geographic distance between provinces increases, spatial correlation gradually weakens, which limits the spatial spillover effects of factors due to regional boundaries. Based on this, referring to the method by Song J. L. et al.24, a distance-based spatial weight matrix is constructed, and a stepwise regression analysis with a 100 km step size is used for the study.

The economic geography spatial weight matrix constructed using the gravity model is as follows:

Where \(\:{d}_{ij}\) is the geographical distance between provinces i and j; \(\bar{Q}_{i}\) and \(\bar{Q}_{j}\) represent the GDPs of provinces i and j, respectively.

The distance-based spatial weight matrix is as follows:

Data sources

This study conducts an empirical analysis using panel data from 30 provinces in China from 2011 to 2022. Due to data availability, the sample does not include Tibet, Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan. The data used in this study are sourced from the CEIC database, the National Bureau of Statistics, the China Statistical Yearbook, and the China Energy Statistical Yearbook. Data for control variables are obtained from the Wind database, the National Bureau of Statistics, and the China Statistical Yearbook. For detailed descriptions of each variable, refer to Table 4.

Empirical analysis

Analysis of CNC measurement results

Figure 2 illustrates the trends in China’s CNC indices, consisting of carbon reduction capacity and carbon removal capacity, from 2011 to 2022. Both subsystems show a consistent upward trend, reflecting significant progress in improving CNC, in line with SDG 13. The carbon reduction capacity demonstrates steady growth overall, with a brief fluctuation in the mid-period, followed by a rapid recovery and sustained increase. This indicates that China’s efforts in implementing carbon reduction policies, promoting renewable energy utilization, and optimizing industrial structures have achieved remarkable results, aligning with SDG 7 and SDG 12. This finding aligns with previous studies, which have shown the positive effects of carbon reduction policies on emission reduction efforts, but our analysis further highlights the importance of carbon removal initiatives in complementing these efforts, contributing to SDG 15. In comparison, the carbon removal capacity exhibits a more rapid growth trajectory, particularly accelerating in the later period, reflecting significant improvements in carbon sink initiatives, such as afforestation and carbon capture technologies, thus contributing to SDG 15. However, the growth rate of carbon removal capacity has slowed slightly in the recent period, indicating the need for further enhancement. Overall, carbon reduction capacity has remained higher than carbon removal capacity throughout the study period, but the gap between the two subsystems has gradually narrowed. Notably, the contribution of carbon removal capacity has increased significantly in recent years, demonstrating a more balanced approach to enhancing CNC, aligning with SDG 9. In summary, China’s CNC has steadily improved over the study period. Moving forward, strengthening the growth potential of carbon removal capacity will be essential to fully achieve the country’s carbon neutrality goals, which directly supports SDG 13 and SDG 7.

Figure 3 shows the trends of the carbon reduction capacity and carbon removal capacity, the two subsystems of China’s CNC, across eight regions from 2011 to 2022. The development of CNC exhibits significant regional differences, with varying contributions from the two subsystems. Coastal regions, such as the Northern Coastal and Eastern Coastal Regions, lead in CNC development, supported by their economic and technological advantages, with both subsystem indices showing steady growth. In particular, the Northern Coastal Region has seen a notable increase in carbon removal capacity in recent years, surpassing carbon reduction capacity after 2020, reflecting progress in carbon sink development. The Southern Coastal Region displays relatively balanced development of the two subsystems, with noticeable improvements in carbon removal capacity in recent years. In contrast, inland regions, such as the Northwest and Southwest Regions, have lower overall CNC levels but show steady growth in both subsystems, with carbon removal capacity becoming increasingly significant. The Middle Reaches of the Yellow River stands out, with rapid growth in both subsystems, where carbon removal capacity surpassed carbon reduction capacity after 2021, pointing to the success of ecological restoration and afforestation initiatives. Meanwhile, the Northeast Region lags behind, with limited growth in carbon removal capacity and a considerable gap between the two subsystems.

Figure 4 illustrates the trends in CNC across eight regions of China from 2011 to 2022, revealing significant differences in CNC levels, growth rates, and development patterns. Coastal regions maintain a leading position in CNC development, supported by strong economic foundations, technological innovation, and comprehensive policy measures. The Northern Coastal Region stands out with rapid CNC growth, particularly after 2018, reaching the highest level nationwide by 2022, which may be associated with the extensive implementation of carbon reduction technologies and large-scale carbon sink projects, aligning economic growth with carbon neutrality goals. The Eastern Coastal Region has demonstrated stable CNC growth since 2016, although recent progress has slowed, suggesting constraints in further carbon reduction potential and the need for technological breakthroughs. Similarly, the Southern Coastal Region has exhibited balanced growth in both carbon reduction and carbon removal capacities, with noticeable acceleration in CNC development after 2020, possibly linked to advancements in carbon sink initiatives. In contrast, inland regions are characterized by an ecologically driven development model, with notable regional differences. The Middle Reaches of the Yellow River has achieved exceptional CNC growth since 2018, possibly driven by ecological restoration and afforestation projects, establishing itself as a model for integrating ecological governance with CNC enhancement. The Middle Reaches of the Yangtze River also shows stable and balanced CNC growth, reflecting a coordinated approach to economic development and environmental protection. The Southwest Region has made steady progress by utilizing its abundant ecological resources to strengthen natural carbon sinks, showing a positive but moderate growth trajectory. However, the Northeast and Northwest Regions lag significantly behind. The Northeast Region, constrained by a slow industrial restructuring process and insufficient investment in low-carbon technologies, has experienced limited CNC improvement, while the Northwest Region, despite recent progress, remains hindered by weak economic foundations and environmental fragility, leading to the lowest CNC levels nationwide. At the national level, CNC has consistently improved since 2011, with growth accelerating significantly after 2016, likely influenced by the leadership of coastal regions and the ecological restoration efforts of inland regions.

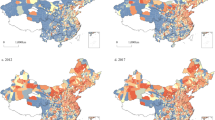

Figure 5 illustrates the spatial distribution and trends of CNC in China from 2011 to 2022, highlighting significant regional disparities and the evolving spatial patterns of CNC development. In 2011, CNC levels were generally low across most regions, with only coastal provinces like Shandong, Jiangsu, and Guangdong showing moderate levels, while western regions, including Xinjiang, Qinghai, and Tibet, remained at the lowest levels. This early imbalance in CNC development, concentrated in economically developed coastal regions, reflects SDG 10. By 2013 and 2015, CNC levels in coastal areas continued to rise, with provinces like Zhejiang and Jiangsu consolidating their advantages. Some inland regions, such as the Middle Reaches of the Yellow River and the Southwest Region, showed improvement, likely driven by ecological restoration and carbon sink projects, contributing to SDG 13 and SDG 15. However, growth in the Northwest and Northeast regions remained limited, and regional disparities persisted. In 2017, CNC levels in central regions like Henan, Hunan, and Anhui improved significantly, expanding the range of moderate CNC levels, although the spatial gap between coastal and inland areas remained, linked to the uneven distribution of economic and technological resources, relevant to SDG 9. By 2019, inland regions such as Shaanxi, Henan, and Sichuan saw substantial CNC growth, driven by enhanced ecological governance and carbon sink capacities, aligned with SDG 12 and SDG 15. Coastal regions, particularly the Northern Coastal Region, maintained leadership with high CNC levels. By 2022, CNC distribution became more balanced, with high CNC levels spreading from coastal to inland areas like Shaanxi, Henan, and Chongqing, narrowing the gap. However, western provinces like Xinjiang, Qinghai, and Tibet remained at lower CNC levels, highlighting persistent regional disparities and the need for further technological innovation and policy support, connected to SDG 9.

Spatial trends of CNC changes in selected years. The map was produced using ArcMap 10.4 software. The base map is the standard map (survey number GS(2016)1569) obtained from the Ministry of Natural Resources of China’s Standard Map Service website. URL: http://bzdt.ch.mnr.gov.cn/browse.html?picId=4028b0625501ad13015501ad2bfc0009.

Robustness test

To evaluate the robustness of the improved entropy-weighted TOPSIS model, this study recalculates China’s CNC using the traditional entropy-weight method, entropy-weighted TOPSIS method, and TOPSIS method. The correlation coefficients between the alternative methods and the original results are presented in Table 5. The results show that the correlation between the alternative methods and the improved entropy-weighted TOPSIS model is significant, with all correlations passing the 1% significance level test, indicating that the improved model performs well in terms of robustness.

Furthermore, this study selects several indicators from the CNC index system, such as Industrial Energy Intensity (x3), Proportion of Afforestation Area (x11), and Number of University-Authorized Technology Patents and Licensing Rate (x15), to analyze the correlation between the calculation results and these indicators. The results reveal that x3 is not significantly correlated with the traditional entropy-weight method results; x11 shows a significantly negative correlation with the entropy-weighted TOPSIS results, which contradicts real-world logic; however, x3, x11, and x15 are more reasonably represented in the improved entropy-weighted TOPSIS model, suggesting that the model can better address the relationships between these indicators.

Through the above analysis, it can be concluded that the improved entropy-weighted TOPSIS model demonstrates higher stability and accuracy compared to traditional methods, providing a more comprehensive reflection of the complexity involved in CNC evaluation.

Analysis of regional differences in CNC

Figure 6 illustrates the trends in the overall Gini coefficient for regional CNC in China from 2011 to 2022, reflecting a significant widening of regional disparities over the study period. From 2011 to 2013, the Gini coefficient showed a downward trend, indicating a reduction in regional inequality, which is closely related to the relatively balanced national policies on investment and resource allocation during this period. However, starting in 2014, the Gini coefficient began to rise steadily, reflecting an expansion of regional disparities. Coastal regions, relying on their economic and technological advantages, experienced rapid CNC development, while inland regions lagged behind. After 2017, regional disparities further intensified, with coastal regions consolidating their leadership and the gap between coastal and inland regions widening further. By 2021, the Gini coefficient reached its highest level, but a slight decline in 2022 suggests that targeted policies, such as ecological restoration and carbon sink projects in less-developed regions, have begun to take effect. Overall, the trends from 2011 to 2022 indicate a sustained increase in regional CNC disparities, although the slight decline in 2022 demonstrates that strengthening technological support and reallocating resources can effectively promote balanced CNC development, contributing to the achievement of China’s carbon neutrality goals.

Figure 7 illustrates the decomposition of the Gini coefficient for regional CNC in China from 2011 to 2022, highlighting the primary sources of disparities and the trends in contribution rates. The results suggest that regional disparities in CNC are primarily driven by between-group disparities (Gb), which consistently account for the largest share of overall inequality throughout the study period, contributing between 48% and 66%. This dominance appears to reflect the structural differences between regional groups, such as coastal and inland areas, as the main source of CNC disparities. While Gb shows a generally declining trend from 2011 to 2019, indicating a narrowing of intergroup disparities, it stabilizes and slightly increases after 2019, suggesting a slowdown in convergence or a resurgence of inequality between groups. In contrast, within-group disparities (Gw) remain consistently low and stable, with contribution rates generally below 10%, indicating that intra-group differences, such as disparities among provinces within the same region, have had minimal impact on overall inequality. Meanwhile, the hyper-variability component (Gt), which represents overlapping or cross-regional disparities, shows a gradual upward trend, with its contribution rate rising steadily from approximately 25% in 2011 to over 38% by 2019, before slightly declining in the final years of the study period. This trend highlights the growing complexity of cross-regional interactions, such as economic interdependencies, technological spillovers, and ecological linkages, as an increasingly significant factor in CNC disparities. In summary, regional CNC disparities are predominantly driven by between-group differences, while within-group differences appear to play a negligible role. However, the rising influence of hyper-variability underscores the need to address cross-regional dynamics in policy design.

To assess the robustness of the Gini coefficient, this study employs robustness analysis by examining whether the Gini coefficient remains stable through methods such as excluding municipalities directly under the central government, dividing the data into different time periods, and removing extreme values. The results are presented in Table 6. After excluding municipalities directly under the central government, dividing by time periods, and removing extreme values, the overall Gini coefficient shows a consistent upward trend, which aligns with the findings from previous research. Furthermore, in the decomposition of the Gini coefficient, the between-group Gini coefficient is the largest, indicating that the primary source of regional differences in CNC is the between-group disparity, which is also consistent with earlier research results. Therefore, the Dagum Gini coefficient calculation in this study is robust.

Table 7 presents the within-group Gini coefficients for eight regions in China from 2011 to 2022, showing intra-regional disparities in CNC. The Northeast Region consistently shows low Gini coefficients, indicating minimal disparities, though slight increases in recent years suggest emerging inequality. The Eastern Coastal Region exhibits a declining trend in Gini coefficients, which may reflect the effects of coordinated policies and shared technological advantages in promoting greater internal balance. In contrast, the Northern Coastal Region displays a significant upward trend, with Gini coefficients peaking in 2021, likely due to uneven industrial upgrades and the adoption of carbon reduction technologies. The Southern Coastal Region shows moderate disparities, with Gini coefficients increasing after 2018, which could be associated with uneven progress in carbon sink and reduction projects. The Northwest Region consistently has high Gini coefficients, with further increases after 2017, suggesting persistent disparities driven by ecological and resource constraints. Similarly, the Southwest Region exhibits high and fluctuating disparities, with notable increases in 2021 and 2022, indicating uneven progress in utilizing natural carbon sinks. The Middle Reaches of the Yangtze River demonstrates low and declining Gini coefficients, reflecting strong internal uniformity possibly driven by cooperative policies and similar industrial structures. In contrast, the Middle Reaches of the Yellow River has the highest and most volatile Gini coefficients, with significant increases after 2015, likely reflecting disparities driven by uneven resource allocation, ecological restoration efforts, and economic structures. Overall, coastal regions such as the Eastern Coastal Region show improving internal homogeneity, while inland regions like the Northwest and the Middle Reaches of the Yellow River face persistent disparities. This suggests the need for targeted policies to reduce intra-regional inequality and promote balanced CNC development.

Table 8 presents the Gini coefficients between different regions in China from 2011 to 2022, highlighting regional disparities in CNC. The results indicate that the gap between the Northern Coastal Region and the Northwest Region and the Middle Reaches of the Yellow River is the largest and continues to widen, suggesting the Northern Coastal Region’s leading position in CNC development, likely influenced by its economic and technological advantages. The gap between the Southern Coastal Region and the aforementioned inland regions is also expanding, which may be linked to significant progress in carbon sink and emission reduction projects. The disparities between the Eastern Coastal Region and inland regions remain relatively stable but still significant. Disparities among coastal regions are relatively small, particularly between the Northern Coastal Region and the Eastern and Southern Coastal Regions, indicating more balanced CNC development within coastal areas. Meanwhile, the gap between the Northeast Region and coastal regions is gradually widening, especially with the Northern and Southern Coastal Regions, although the gap with the Eastern Coastal Region has slightly decreased. Disparities among inland regions remain significant, particularly between the Northwest Region and the Middle Reaches of the Yellow River, which can be attributed to uneven resource allocation and policy support.

Spatiotemporal evolution and Spatial spillover effects of CNC

Dynamic evolution analysis

Traditional kernel density estimation

Fig.8 presents the traditional kernel density estimation results of CNC for the nation and eight geographic regions, showing the dynamic evolution of CNC levels and significant regional disparities. At the national level, the kernel density central line shows an overall leftward shift with a relatively small displacement, indicating slow nationwide improvement and persistent regional differences. In the coastal regions, the eastern coastal region shows a transition from a bimodal distribution to a pattern with one higher peak on the right and a lower peak on the left, suggesting steady improvement in CNC levels. The southern coastal region demonstrates a rightward shift in the kernel density central line and a more concentrated distribution, indicating narrowing internal disparities. The northern coastal region displays a progression in its main peak from low and wide to high and narrow, suggesting increased concentration of CNC distribution and overall progress. In contrast, the northeastern region transitions from no initial fluctuations to a sharply bimodal distribution with symmetrical peaks, indicating significant polarization and regional disparities. In inland regions, the middle reaches of the Yellow River shows a leftward shift in the kernel density central line, with peaks fluctuating between "high-peak, slight decline, and slight increase," indicating limited improvement. The middle reaches of the Yangtze River evolves from a bimodal distribution to a flatter curve with slight upward movement, indicating narrowing internal disparities. The northwest region shows a dynamic pattern of "initial rightward shift followed by leftward shift" in the kernel density central line, indicating early improvement but later stagnation. The southwest region shows a consistent rightward shift in the kernel density central line, reflecting steady CNC progress. In summary, coastal regions demonstrate faster improvement and more concentrated CNC distributions, while inland regions show slower progress with more pronounced fluctuations, highlighting significant imbalances in regional CNC development.

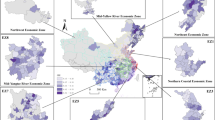

Spatial kernel density estimation

Fig.9 uses static kernel density estimation to analyze the spatial correlation of CNC between provinces and their neighboring provinces, with the x-axis representing the CNC level of neighboring provinces and the y-axis representing the CNC level of the province itself. The density contours are predominantly parallel to the y-axis and concentrated above the 45° diagonal line, suggesting that while the CNC levels of neighboring provinces may have some influence on a province’s CNC level, this influence appears to be relatively weak, and the spatial correlation is not significant. Furthermore, the CNC levels of provinces are generally higher than those of their neighbors, indicating the regional development advantage of certain high-CNC provinces, which are likely supported by stronger economic foundations, technological capacity, and policy support. However, the parallel alignment of density contours with the y-axis suggests that the improvement in a province’s CNC level is primarily driven by internal factors rather than positive spillover effects from neighboring provinces. This pattern indicates the limitations of high-CNC regions in diffusing low-carbon technologies and policies to surrounding areas and highlights the spatial imbalance in CNC development. High-CNC provinces tend to exhibit a degree of “isolation” due to their advanced capabilities, while low-CNC provinces face developmental challenges due to insufficient technological collaboration and policy support. Therefore, it seems necessary to strengthen regional cooperation, optimize resource allocation, and enhance policy spillover mechanisms to facilitate the diffusion of technologies and policies from high-CNC to low-CNC regions, helping narrow regional disparities and promote balanced low-carbon development nationwide.

Figure 10 illustrates the dynamic impact of neighboring provinces’ CNC levels in year t on the CNC distribution of a given province in year t + 3 under a three-year spatial lag condition, covering the national scale and eight geographic regions. Overall, the kernel density curves are predominantly parallel to the y-axis, suggesting weak spatial spillover effects from neighboring provinces on CNC development in focal provinces. The improvement in CNC levels appears to be mainly driven by internal factors. In regions like the northern coastal, southern coastal, southwest, and middle reaches of the Yellow River, density peaks are above the 45° diagonal line, indicating positive spillover effects from neighboring provinces and generally higher CNC levels. However, in areas such as the northwest, middle reaches of the Yangtze River, and parts of the eastern coastal and northeastern regions, density peaks are below the diagonal line, suggesting weak or negative spillover effects and slower CNC development. Coastal regions show faster CNC improvement and stronger independence, while inland regions, particularly the northwest and middle reaches of the Yangtze River, face slower progress, influenced by negative spillover effects from neighbors. These findings highlight significant regional disparities and suggest the need for increased policy support and technology diffusion in low-CNC regions.

Markov chain analysis

The traditional markov chain method was employed to analyze the temporal dynamic changes of China’s CNC from 2011 to 2022. The analysis period was divided into three phases: 2011–2016, 2017–2022, and the entire 2011–2022 period. Based on the comprehensive scores observed during the period, the study categorizes the regions into four states: low type (I), low-medium type (II), medium-high type (III), and high type (IV). Using these classifications, the third-order Markov transition probability matrix for each time period was further calculated, with the results presented in Table 9.

Based on the results of the traditional Markov chain analysis, this study examines the transfer trends and spatiotemporal evolution patterns of China’s CNC across three time periods: 2011–2022, 2011–2016, and 2017–2022. In the overall time period of 2011–2022, regions with low CNC exhibit a strong lock-in effect, with a high self-transition rate of 0.524, indicating that these regions face significant challenges in improving CNC in the short term. Conversely, regions with high CNC (State IV) demonstrate a strong self-reinforcing effect, with a self-transition rate of 0.925, showing stability and dominance. Additionally, during the period of 2011–2016, the self-transition rate for low CNC regions remains high, signifying the difficulty these areas face in improving due to weak economic foundations or outdated technology, while regions with high CNC continue to maintain stability, and some medium-level CNC regions (State II) experience upward mobility. By 2017–2022, some low CNC regions begin to show an upward transition, particularly from State I to State II, reflecting the gradual effects of policy support and economic development. High CNC regions, however, continue to maintain strong stability, demonstrating the “club effect,” where these regions’ CNC continues to enhance in the process of sustained development. This highlights the importance of addressing SDG 7 through increased technological advancements and investment in clean energy infrastructure in lower-CNC regions. Furthermore, it emphasizes the need for promoting responsible consumption and production as outlined in SDG 12, particularly in medium- and low-CNC regions. Additionally, the gradual transition of low-CNC regions reflects the role of SDG 13 policies in driving improvements through systemic policy support. Finally, the policy interventions required to bridge the regional gaps should align with SDG 9 by fostering technological innovation and sustainable industrial growth, while also addressing SDG 15 by enhancing ecological restoration and land management in these regions. Overall, there are significant disparities in CNC across regions, with low CNC areas still facing considerable challenges in improvement. Policy interventions should focus on technological innovation, resource allocation, and policy support to facilitate leapfrog development in regions with lower CNC.

Based on the results from Table 10, which presents the spatial markov chain analysis, the spatial dynamics and transition patterns of CNC across different regions in China demonstrate significant regional disparities and spatial lag effects. The analysis reveals varying transition modes across regions with different spatial lag types, highlighting the spatial agglomeration effects and lagging phenomena in CNC transitions.

Firstly, regions in the low spatial lag type (State I) predominantly exhibit low CNC, with a high self-transition probability. The transition probability from State I to State I is 0.864, suggesting strong stability in CNC within these regions, with limited progress toward higher levels of carbon neutrality in the short term. The transition probabilities to higher states (States II, III, IV) are low, at 0.242, 0.067, and 0.004, respectively, indicating significant challenges in advancing these regions and difficulty in closing the CNC gap, which may reflect the pronounced lag effect and spatial agglomeration phenomenon.

Secondly, regions in the medium-low spatial lag type (State II) exhibit more diverse transition patterns, suggesting dynamic changes in CNC. The self-transition probability from State II to State II is 0.512, indicating some stability, but there is a notable risk of downward transition. The probability of transitioning from State II to State I is 0.242, indicating that some regions may experience a decline in CNC due to insufficient policies, technology, or resources. The transition probabilities from State II to higher states (States III and IV) are low, at 0.393 and 0.036, suggesting limited potential for upward movement in these regions.

For regions in the medium-high spatial lag type (State III), the CNC transition patterns are more complex, showing a certain degree of stability. The self-transition probability from State III to State III is 0.465, indicating moderate stability. However, there is a noticeable risk of downward transition, with the probabilities of transitioning from State III to State II (0.245) and State I (0.071), suggesting that some regions may face a decline in CNC due to regional economic pressures, policy implementation challenges, or other factors. Despite this, there is some potential for upward movement, with a 0.220 probability of transitioning from State III to State IV, suggesting that some regions may make progress toward higher levels of CNC, driven by innovation and policy support.

Finally, regions in the high spatial lag type (State IV) show high CNC, with a strong tendency to maintain their current state. The self-transition probability from State IV to State IV is 0.827, indicating high stability in CNC. The probabilities of transitioning from State IV to lower states (States III, II, I) are low, at 0.111, 0.053, and 0.009, respectively, suggesting that these regions are unlikely to experience significant setbacks. However, although the transition probabilities to lower states are low, some fluctuations may occur, particularly in response to external economic or policy adjustments.

Overall, the spatial Markov Chain analysis reveals significant differences in the CNC transition processes across regions. Low CNC regions face substantial challenges in upward mobility, while high CNC regions show high stability, likely reflecting the impact of spatial lag effects. To effectively improve CNC in regional areas, especially in low and medium-low CNC regions, enhanced policy support, technological innovation, and better resource allocation are necessary to facilitate leapfrog development, contributing to SDG 7 and SDG 12. For high CNC regions, sustained innovation and cross-regional cooperation should be emphasized to maintain their advantages and foster collaborative development, aligned with SDG 9 and SDG 13. Moreover, improving the sustainability and ecological resilience of regions with low CNC, through ecological restoration and environmental management initiatives, can support SDG 15.

Convergence analysis

Table 11 reports the spatial convergence measurement results of China’s CNC during the sample period, showing significant absolute β-convergence and absolute club convergence at both the national level and across eight geographic regions. This suggests that CNC levels tend to move towards a common steady state in the long term, aligning with SDG 13 by emphasizing the need for uniform progress toward carbon neutrality. However, without considering control variables, the differences in CNC convergence rates across regions remain notable: Northwest Region (16.731%) > Northeast Region (11.521%) > Eastern Coastal Region (12.489%) > Southwest Region (7.872%) > Nationwide (7.179%) > Middle Reaches of the Yangtze River (394.839%) > Southern Coastal Region (2.981%) > Middle Reaches of the Yellow River (0.227%). The Northwest Region shows the fastest convergence rate, with a half-life convergence period of only 4.143 years. This performance may be attributed to its accelerated development of renewable energy resources, such as wind and solar energy, in line with SDG 7, as well as strong policy support. Furthermore, the region’s relatively low starting point may have enabled it to leverage its “latecomer advantage.” The Eastern and Northeastern regions show robust convergence. The Eastern Coastal Region maintains stable progress due to its economic and technological advantages, while the Northeastern Region shows rapid catch-up, reflecting its active efforts in decarbonizing traditional industries, thus contributing to SDG 13. In contrast, the Middle Reaches of the Yellow River shows the slowest convergence rate at only 0.227%, with a half-life convergence period as long as 305.671 years. This indicates deep-seated challenges in its low-carbon transition, such as a mono-structured economy, weak local governance capacity, and an overreliance on high-carbon industries, which are directly linked to SDG 12.

When control variables—such as economic development level, urbanization rate, R&D intensity, and industrial structure—are taken into account, the CNC convergence rates improve significantly, and the ranking of regions changes: Northeast Region (70.58%) > Eastern Coastal Region (22.753%) > Southwest Region (17.897%) > Nationwide (7.465%) > Northwest Region (15.656%) > Middle Reaches of the Yangtze River (15.963%) > Southern Coastal Region (13.391%) > Middle Reaches of the Yellow River (10.647%). The Northeast Region is particularly notable, with its convergence rate rising from 11.521% to 70.58% and its half-life convergence period shortening to 0.982 years. This highlights the critical role of control variables, especially economic development, urbanization, and R&D intensity, in driving its low-carbon transition, directly supporting SDG 9. In recent years, the Northeastern Region has actively pursued decarbonization of traditional industries, optimization of its energy structure (e.g., transitioning from coal to renewable energy), and increased R&D investments, addressing its historical disadvantages in low-carbon development. The Eastern Coastal Region’s convergence rate increased from 12.489% to 22.753%, indicating its sustained investment in technological innovation and industrial optimization, which contributes to SDG 9. Similarly, the Southwest Region’s convergence rate rose from 7.872% to 17.897%, demonstrating the significant impact of policy support and low-carbon technology adoption on its energy development and economic transformation, aligning with SDG 12. However, despite an increase in the Middle Reaches of the Yellow River’s convergence rate to 10.647%, its half-life convergence period remains relatively long at 6.51 years, suggesting its insufficient development momentum and lagging transition progress. This may be linked to its mono-industrial structure, heavy dependence on high-carbon industries, and low efficiency in resource allocation, which needs to be addressed in line with SDG 15.

Spatial spillover effect analysis

In the analysis presented in Table 12, Wij1, Wij600, and Wij700 represent distinct spatial weight matrices. Specifically, Wij1 is an economic geography-based spatial weight matrix that reflects the economic interactions and geographical proximity between regions; Wij600 is an inverse geographic weight matrix based on a 600 km range, representing medium-distance spatial interactions; and Wij700 is an inverse geographic weight matrix based on an 800 km range, capturing long-distance spatial spillover effects. These matrices are utilized to analyze how various influencing factors impact CNC through both direct effects and spatial spillover effects at different spatial scales. The results reveal significant regional heterogeneity and spatial distance dependence in CNC’s spillover effects.

For the direct effects, industrial structure (a1) and urbanization level (a2) show no significant impact on CNC across all models, indicating that standalone improvements in industrial upgrading or urbanization levels are insufficient to directly enhance local CNC. Economic development (a3) demonstrates a significantly negative direct effect in all models, reflecting the persistent reliance of economic growth on carbon-intensive activities, which inhibits CNC improvement. Openness (a4) also shows insignificant direct effects, with small coefficients across all models, suggesting that increased trade and economic openness currently have limited direct influence on CNC enhancement. Additionally, R&D intensity (a5) exhibits a significantly negative direct effect on CNC, suggesting that current R&D investments are insufficiently focused on low-carbon technologies. Government intervention (a6) shows negative direct effects on CNC at shorter spatial ranges (Wij1 and Wij600), which may be attributed to inefficiencies caused by excessive government intervention in resource allocation.

Regarding spatial spillover effects, industrial structure (W*a1) demonstrates a significant negative spillover effect (-0.213) under the economic geography weight matrix, suggesting that an increase in the tertiary-to-secondary industry ratio in neighboring regions may generate competitive pressures on local CNC. Urbanization level (W*a2) exhibits negative spillover effects at shorter distances but becomes significantly positive (10.046) at longer distances (Wij700), implying that while urbanization in nearby regions may intensify resource competition and environmental stress, it can promote CNC improvements in distant regions through mechanisms like technology diffusion and synergistic development. Economic development (W*a3) exhibits significantly negative spillover effects at medium and long distances, highlighting the detrimental impacts of carbon leakage and pollution transfer on neighboring regions. For openness (W*a4), its spillover effects are insignificant under wij1 and wij600, but significantly negative (-1.116) under wij700. This suggests that, at greater spatial distances, openness might contribute to carbon-intensive activities being shifted to other regions, thereby hindering CNC improvements in these areas. The spatial spillover effects of R&D intensity (W*a5) are insignificant across all models, reflecting weak interregional technological collaboration. Conversely, government intervention (W*a6) shows a significantly positive spillover effect (3.326) at longer distances, indicating that cross-regional policy coordination and resource support effectively enhance CNC in neighboring areas.

Using a stepwise geographical threshold of 100 km, different inverse distance spatial weight matrices were applied to calculate the spatial spillover effects of CNC, as shown in Fig. 11. The figure illustrates the spatial spillover effects of CNC under varying geographical thresholds, reflecting regional influence and its dependence on spatial distance. For geographical thresholds between 100 and 600 km, the spillover effect coefficients are negative, with 95% confidence intervals frequently crossing zero, indicating that negative spillover effects at shorter distances are notable but statistically unstable. These negative effects could stem from resource competition, heightened environmental pressures, or carbon leakage, which are directly related to SDG 12. Specifically, geographical proximity between neighboring regions may result in intensified competition for resources, such as clean energy, technological equipment, or carbon reduction funding, aligning with SDG 7. Furthermore, the absence of policy coordination at shorter distances might lead to carbon-intensive activities shifting to adjacent regions (carbon leakage), which could exacerbate regional imbalances and limit CNC improvement in neighboring areas. This scenario directly ties to SDG 13 by emphasizing the need for coordinated efforts in climate mitigation across regions. Additionally, the negative effects at shorter distances may suggest a “competitive effect,” where a region’s efforts to improve its CNC might reduce the resources available to its neighbors, limiting the positive spillovers of technology or policy support, which could be enhanced by fostering collaboration as promoted under SDG 9.

When the geographical threshold reaches 700 km, the spillover effects shift from negative to positive, with coefficients rapidly increasing and confidence intervals no longer crossing zero, indicating that the positive spillover effects at longer distances are statistically significant. This shift may reflect the emergence of beneficial effects such as technological diffusion, policy coordination, and cross-regional cooperation, directly supporting SDG 9. At longer distances, resource competition tends to decrease, and collaboration and synergies could become more dominant, fostering low-carbon technology diffusion, which aligns with SDG 7. For instance, innovations in low-carbon technologies can spread across greater distances, enabling other regions to adopt these technologies, contributing to SDG 13. Similarly, cross-regional policy coordination might enhance CNC levels in neighboring areas by sharing best practices or providing financial support. Additionally, economic ties and industrial cooperation over longer distances could facilitate knowledge spillovers and experience sharing, contributing to overall CNC improvement on a broader scale, further supporting SDG 15. Beyond 700 km, the spillover effects stabilize, with coefficients remaining at relatively high levels, indicating that the spatial diffusion effects have reached saturation. This suggests that technological and policy spillovers are effectively absorbed within a certain range, with marginal impacts diminishing beyond this point.

Discussion

This study provides a comprehensive analysis of China’s Carbon Neutrality Capacity (CNC) from 2011 to 2022, focusing on regional disparities, spatiotemporal dynamics, and spatial spillover effects. The findings of this study align with several key aspects of existing literature. Consistent with the studies of Xiao et al.25and Zhou et al. (2024)25, the coastal regions, including the Northern, Eastern, and Southern Coastal regions, continue to outperform inland areas in CNC development. This advantage is primarily due to the economic advantages, technological infrastructure, and greater access to resources in coastal regions, which enable effective implementation of low-carbon strategies such as the adoption of renewable energy and industrial upgrades. These factors are crucial for achieving SDG 7, SDG 12, and SDG 13. Our results confirm the widening gap in CNC between coastal and inland regions, reflecting the technological and resource constraints faced by inland areas, as highlighted by Du et al. (2025)26. The growing disparity underscores the critical role of technological diffusion and policy support in narrowing these gaps, which is key to achieving SDG 9 and SDG 10. Addressing these disparities requires targeted interventions, including resource redistribution and innovation-driven policies, particularly in underdeveloped regions.

However, this study also provides new insights that extend beyond prior research. For example, the finding that short-distance (100–600 km) spatial spillover effects are negative, contrasting with previous studies that emphasized positive spillovers at longer distances27, adds a new dimension to the discourse on spatial interactions. The negative spillover effects suggest that geographical proximity can exacerbate resource competition and carbon leakage, rather than fostering cooperation. This finding emphasizes the importance of policy coordination to avoid inefficiencies driven by competition, supporting the observations of Acemoglu et al. (2014) regarding local carbon leakage28. Beyond 700 km, the spatial spillover effects turn positive, further highlighting the importance of cross-regional cooperation in enhancing CNC. This aligns with the findings of Xin et al. (2023)29, which stress the role of technological diffusion and policy coordination in advancing sustainable development.

On the macro level, CNC is central to achieving SDG 7, SDG 12, and SDG 13, as it supports the transition to low-carbon economies30. However, significant regional disparities exist, driven by differences in resources, technology, and policy support, which complicate efforts to meet global sustainability goals. Addressing these imbalances is essential for achieving SDG 9 and SDG 10, requiring targeted regional cooperation and technology diffusion31. On the micro level, regions with higher CNC attract more low-carbon investments, fostering innovation and competitiveness in a sustainability-driven market. Conversely, regions with lower CNC, especially those facing the “lock-in effect,” struggle to implement sustainable practices without substantial policy intervention32,33. This underscores the importance of aligning business strategies with regional low-carbon policies and investing in green technologies to drive both economic growth and environmental sustainability. Overall, CNC serves as a vital driver for balanced, long-term low-carbon transitions at both regional and enterprise levels, supporting a more sustainable future.

The unique contribution of this study lies in its integration of spatial and temporal analyses of CNC, including the exploration of spatial spillover effects and the innovative examination of the “lock-in” and “club” effects in CNC development. These insights provide critical guidance for policymakers seeking to understand the dynamics of regional carbon neutrality and to identify strategic interventions to promote a more balanced and sustainable low-carbon transition across China.

Conclusions, implications and limitations

Conclusions