Abstract

This paper introduces a high-sensitivity, multimode graphene-based metamaterial (MM) biosensor for refractive index sensing, featuring a periodic array of gold (Au) double-split elliptical resonators (DSERs) on a graphene-coated silicon dioxide (SiO₂) substrate with an Au reflective base layer. The proposed design is analyzed using finite-difference time-domain (FDTD) simulations. The unique double-split elliptical geometry significantly enhances electromagnetic field confinement and enables the excitation of multiple distinct resonance modes, outperforming conventional circular or rectangular resonators that typically support only single- or dual-mode responses. The novelty of this work lies in the integration of a graphene–metal hybrid structure that combines tunable plasmonic properties of graphene with strong localized surface plasmon resonances of DSERs, resulting in multimode operation, improved tunability, and superior sensing performance. The bottom gold layer effectively suppresses transmission and reinforces field confinement within the active region. The sensor operates across 650–1500 nm, supporting five well-separated resonance modes that provide multiple sensing channels, enhancing detection efficiency and spectral flexibility. Optimized structural parameters such as the Au array thickness, SiO₂ layer thickness, and resonator width further improve its performance. The biosensor achieves a maximum sensitivity of 714.28 nm/RIU, a figure of merit (FoM) of 51.02 1/RIU, and a quality factor (QF) of 73.42 for breast cancer cell detection. Moreover, it successfully distinguishes between normal and cancerous cells (basal, breast, and cervical), demonstrating its strong potential for biomedical diagnostics and optical sensing applications. These results position the proposed multimode graphene-based biosensor as a promising platform for next-generation photonic and biomedical sensing technologies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Refractive index (RI) sensing has become a crucial component in biomedical diagnostics, as many physiological and pathological changes in tissues and cells are directly reflected in their optical properties1. Variations in RI can provide valuable insights into cell composition, structure, and health, making RI-based sensors particularly relevant for medical applications. One significant area of concern is cancer, which poses a critical global health challenge due to its nature of uncontrolled cell growth and the difficulties associated with early detection2. The absence of early symptoms often leads to delayed diagnosis and worsens patient outcomes. Therefore, RI sensing offers a promising approach for distinguishing between normal and abnormal cells, thus aiding in earlier and more accurate cancer detection3. Recent advancements in nanomaterials technology have enabled the development of portable, in situ point-of-care sensors, which hold great promise for improving patient outcomes and reducing mortality rates2,3. Particularly notable in cancer diagnosis are label-free biosensors, which are known for their high sensitivity in detecting biomolecules. Researchers have explored various optical sensor platforms, such as photonic crystal fibers3, metamaterials (MMs)4, and surface plasmon resonance (SPR) sensors5, to enhance diagnostic capabilities. Among these, SPR-based biosensors stand out for their ability to enable label-free detection, real-time monitoring, and high sensitivity, positioning them at the forefront of current research6. SPR achieves this by confining light propagation, thereby enhancing the diffraction limit and optimizing biosensor performance. Due to their remarkable tunability, exceptional sensitivity, and high FoM, SPR-based refractive index biosensors offer significant advantages in biomedical applications, making them powerful tools for precise detection and diagnostic processes7. These sensors detect subtle variations in light refraction caused by changes in the optical properties of materials. The integration of advanced materials, particularly two-dimensional (2D) materials such as graphene, MXene, black phosphorus (BP), and graphene oxide, has substantially enhanced biosensor performance8. Among these materials, graphene stands out due to its remarkable properties, including high carrier mobility, tunable conductivity, and strong light-matter interaction, making it an excellent candidate for biosensing applications9. Graphene-based sensors provide an innovative approach for cancer detection by exploiting these properties to identify biomarkers at extremely low concentrations. These sensors can detect early molecular markers of cancer long before clinical symptoms manifest, enabling swift and accurate analysis, which enhances diagnostic accuracy and treatment efficacy10. Furthermore, their biocompatibility makes them suitable for non-invasive testing methods, supporting their use in cancer monitoring. Enhancing this capability, Metal-Insulator-Metal (MIM) structured graphene sensors improve sensitivity by using the insulating layer to precisely control the electric field. This amplification of the sensor’s response to external stimuli allows for earlier detection of biomarkers, making MIM-graphene sensors highly effective tools for early cancer diagnosis11. The remarkable properties of MMs arise from their unique internal structure, which distinguishes them from natural materials. In natural materials, properties are primarily determined by chemical composition and bonding. One of the key factors driving interest in MMs is their significant impact on light transmission12. These materials consist of subwavelength structures arranged in periodic or random patterns, producing unique electromagnetic (EM) properties not found in natural substances, such as negative refractive index, invisibility cloaking, negative permeability, and artificial magnetism13. These distinct properties stem from their structural design rather than their composition, making them particularly suitable for a variety of applications, especially in biosensing14. MM-based sensors capitalize on the specific interactions between engineered MMs and external stimuli, leading to improved sensitivity, faster response times, and notable miniaturization15,16. Advanced sensors can detect subtle changes in environmental conditions, biological markers, or chemical compositions with high precision. The ability to customize EM responses through structural design broadens their potential applications in fields such as biomedical diagnostics, environmental monitoring, and telecommunications17,18. The integration of graphene with MMs has opened new avenues for developing highly sensitive biosensors. This combination leverages graphene’s exceptional electrical, optical, and mechanical properties alongside the unique EM characteristics of MMs, resulting in sensors with enhanced detection capabilities. The synergy between graphene and MMs is driving innovation in the development of ultra-sensitive, compact, and versatile biosensing platforms18,19. Recent research has highlighted the remarkable effectiveness of various sensor architectures in detecting biological and chemical targets with high sensitivity. For example, Lotfi et al.20 developed a biosensor using plasmonic waveguides based on an asymmetric Mach-Zehnder interferometer (MZI) for cancer detection, achieving a sensitivity of 1034 THz/RIU. Emami Nejad et al.21 developed a tunable MM biosensor for cancer detection, achieving a peak sensitivity of 658 nm/RIU. Patel et al.22 introduced a graphene metasurface biosensor, which demonstrated an even higher sensitivity of 431 nm/RIU. Ebadi et al.23 designed an ultra-compact plasmonic filter based on a stub-shaped MIM waveguide, highlighting its potential for use in miniaturized photonic integrated circuits and wavelength-division multiplexing systems. Bensalah et al.24 developed a highly sensitive plasmonic sensor utilizing a MIM waveguide coupled with double hexagonal ring resonators, achieving a maximum sensitivity of 4074 nm/RIU. Lai et al.25 proposed an on-chip optical filter and sensor employing an end-coupled MIM waveguide integrated with a hexagonal resonator and dual parallel blocks, demonstrating a high RI sensitivity of 780 nm/RIU and an exceptional FOM of 3000. Furthermore, Bensalah et al.26 presented another high-sensitivity plasmonic RI sensor incorporating implanted cavities within a MIM waveguide, achieving a maximum sensitivity of 2602.5 nm/RIU. Danaie et al.27 proposed an 8-shaped resonator coupled to MIM waveguides, supporting two resonance modes. Their structure demonstrated a high sensitivity of 1200 nm/RIU for biosensing applications, including the detection of basal cancer cells. Azab et al.28 provided a D-shaped PCF-based RI sensor and experimentally characterized it, achieving a sensitivity of 294.11 nm/RIU within the refractive index range of 1.33 to 1.3538. Li et al.29 proposed a graphene-integrated dielectric–metal hybrid metamaterial LSPR sensor, showing an experimental sensitivity of 271 nm/RIU with enhanced plasmonic resonance strength.

Key design parameters such as sensitivity, QF, FoM, and operational frequency are crucial for enhancing biosensor performance. The development of new materials and innovative structural designs has significantly improved sensitivity, allowed miniaturization, and enabled operation at higher frequencies30,31. Current research is increasingly focused on enhancing the sensitivity of biosensors by integrating MMs with graphene, given their significant potential in biomedical applications. However, achieving a highly sensitive, compact biosensor that maintains a high FoM and QF remains a challenging goal, requiring further innovation and refinement31,32. To address this challenge, we propose a graphene-based MM biosensor utilizing a double-split elliptical resonator (DSER) for refractive index sensing. The proposed design features a periodic structure consisting of a 3 × 3 array of gold metal MM elements. By combining graphene’s superior properties with the unique resonant characteristics of MMs, the design enhances both sensitivity and specificity. Numerical simulations and performance analyses confirm the effectiveness of this approach, paving the way for advanced biosensing applications. The novelty of our work lies in the integration of a periodic array of metallic DSERs on a graphene-coated SiO₂ substrate with an additional gold base layer. The bottom gold layer effectively eliminates transmission and strengthens field confinement within the active region. Unlike previously reported graphene-based MM biosensors that mainly used simple circular, rectangular, or single-split ring resonators, which typically support only one or two resonance modes, our DSER configuration enables multiple distinct resonance modes within the 650–1500 nm reflection range. This multimode behavior significantly enhances detection flexibility and spectral tunability. Furthermore, the narrower resonance bandwidth of our design leads to a higher QF and improved sensing resolution. In contrast to earlier designs that often required complex multilayer stacking or external modulation mechanisms, the proposed hybrid structure achieves high sensitivity through intrinsic electromagnetic coupling between the DSER geometry and the graphene layer. The sensor’s tunability across different chemical potentials, its compact, fabrication-friendly design, and its ability to support non-invasive, label-free detection collectively distinguish it from existing MM biosensors. These advantages highlight the uniqueness of our DSER-based graphene metamaterial and confirm its potential for practical biomedical sensing applications, including cancer cell differentiation. The rest of the paper is organized as follows: Section “Biosensor design and modeling” describes the design and modeling of the biosensor. Section “Optical analysis of the proposed biosensor” presents the numerical analysis conducted to evaluate the critical parameters. Section “Results and discussion” outlines the results and compares them with existing research. Finally, the Conclusion summarizes the main findings and offers concluding remarks.

Biosensor design and modeling

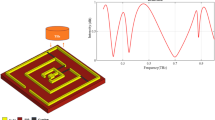

Figure 1 presents the schematic of the proposed biosensor, featuring a 3 × 3 array of MM elements, each incorporating a DSER array. The assembly is positioned above a graphene layer on a SiO₂ substrate. A metallic gold layer is placed on the backside of the substrate, functioning as a reflector. As a result, it prevents the transmission of incident electromagnetic waves and confines the fields within the resonator region. The biosensor has a total footprint of 1800 × 1800 nm². The key structural parameters are as follows: Gold layer thickness (t₁): 100 nm | SiO₂ layer thickness (t2): 500 nm | Graphene monolayer thickness (t3): 0.34 nm | Gold MM array thickness (t4): 100 nm | Width of inner SER (w1): 40 nm | Inner radius of inner SER (r1): 85 nm | Outer radius of inner SER (R1): 125 nm | central angles of inner SER (θ1 = 170°, θ2 = 170°) | Width of outer SER (w₂): 40 nm | Inner radius of outer SER (r2): 185 nm | Outer radius of outer SER (R2): 225 nm | central angles of outer SER (θ3 = 150°, θ4 = 150°) | Sensing layer thickness (t5): 100 nm. The gold DSER arrays play a crucial role in enhancing the confinement of EM waves within the graphene and SiO₂ layers, thus increasing the sensor’s sensitivity. The graphene layer, positioned between the dielectric material and the resonators, significantly enhances absorption and overall sensor efficiency due to its exceptional electrical conductivity. In the proposed DSER biosensor, incident light interacting with the metamaterial array is strongly coupled to the graphene layer and underlying substrate, where graphene’s high conductivity promotes enhanced absorption within the SiO₂ layer. Moreover, the sensing medium, where test samples are placed for detection, is positioned above the gold DSER array.

The optical response of the proposed biosensor was numerically investigated using a three-dimensional finite-difference time-domain (3D-FDTD) method implemented in Lumerical FDTD Solutions. It is worth noting that the present work is based on numerical simulations and theoretical modeling; experimental validation will be an essential next step to confirm the sensor’s performance under real-world biomedical conditions. At this stage, fabrication and measurement facilities are not available to us; however, the simulation results obtained in the FDTD solution module of Lumerical software provide a reliable and widely accepted foundation for predicting device behavior. It is important to note that the proposed design is polarization-sensitive due to its asymmetrical structure. A broadband plane wave source covering wavelengths from 650 to 1500 nm was normally incident (θi = 0°) on the biosensor along the z-axis, with the electric field polarized along the x-axis (TE mode). To ensure accurate simulation results, periodic boundary conditions (PBC) are applied along the x- and y-directions to simulate an infinite array of unit cells. A perfectly matched layer (PML) is used in the z-direction to absorb outgoing waves and prevent reflections, effectively mimicking an open environment. In FDTD simulations, we carefully considered the meshing technique to ensure that the simulation reaches convergence with sufficient precision without unnecessarily prolonging the process. We utilized “Conformal Variant 0” for mesh refinement and “Auto non-uniform” as the mesh type. We have selected a mesh accuracy of 5 for our simulations. The simulation time window was set to 1000 fs to ensure that all transient fields decayed completely, and the simulation background was taken as air (n = 1.00). Moreover, we utilized MATLAB 2019a software to analyze our structure in order to further strengthen the validity of our investigation. Matlab software was used to draw the graph for all parameters. The main goal of this study is to develop a high-performance sensor with enhanced sensitivity, FoM, and QF, which has been accomplished. The chosen configuration ensures strong excitation and effective coupling to surface plasmon modes at both the metal-dielectric and graphene interfaces. For material modeling, the Palik model is used for SiO₂15. Gold is selected for the metallic components due to its excellent plasmonic performance, chemical stability, and compatibility with graphene and biological environments. Its strong SPR in the 600–1500 nm range and oxidation resistance make it ideal for achieving stable, reproducible, and efficient electromagnetic coupling in the proposed biosensor. It is worth noting that the dielectric function of gold was modeled using the Drude model, which accurately represents the intraband (free-electron) response of noble metals in the visible–near-infrared spectral range. The Lorentz–Drude model is primarily required when interaband transitions at shorter wavelengths (< 500 nm) are of interest. As the proposed biosensor operates within 650–1500 nm, the Drude model provides a sufficiently accurate and computationally efficient description of the metal’s optical behavior without requiring additional Lorentzian terms. The permittivity (ε) of gold is defined using the Drude model as follows16:

where ωp represents the bulk plasma frequency, γc denotes the electron collision frequency, and ω is the angular frequency of the incident light. For gold, these parameters are given as ωp = 1.37 × 1016 rad/s and γc = 4.07 × 10¹³ rad/s16. In practical implementations, plasmonic losses and fabrication-induced imperfections can influence the performance of the proposed design. The intrinsic ohmic losses in the metallic components and absorption losses in graphene may slightly broaden the resonance peaks, leading to a reduction in the QF. Nevertheless, gold exhibits relatively low damping compared with other plasmonic metals such as silver (Ag) or copper (Cu) and maintains stable optical behavior under ambient and biological conditions. The strong near-field confinement generated within the double-split elliptical structure helps to mitigate these losses and sustain a high sensitivity.

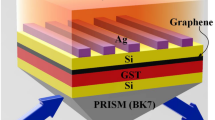

It should be noted that the results presented in this study are based solely on FDTD simulations and thus represent the theoretical design stage. Experimental validation will be considered in future work to verify the simulated optical responses and sensing performance. The proposed design can be fabricated using well-established nanofabrication techniques such as electron-beam lithography (EBL) for pattern definition, followed by metal deposition through thermal or electron-beam evaporation10. Fabrication steps of the proposed biosensor are depicted in Fig. 2. Initially, a thin gold layer is deposited by electron-beam evaporation, followed by the formation of a SiO₂ dielectric layer using physical vapor deposition (PVD). Monolayer graphene, grown via chemical vapor deposition (CVD), is then transferred onto the SiO₂ layer. Subsequently, the top gold DSER array is patterned on the graphene surface through EBL and metal deposition. These fabrication steps are compatible with current laboratory technologies and have been successfully used in similar graphene–metal hybrid plasmonic sensors10. Therefore, the proposed design is not only theoretically effective but also experimentally realizable.

However, several challenges may arise during fabrication, including achieving uniform graphene coverage, precise control of the nanoscale split geometry, and minimizing interfacial defects. Addressing these challenges will be crucial for translating the proposed design into a practical experimental realization. Additionally, fabrication tolerances related to nanoscale variations in the resonator gaps, elliptical dimensions, or layer thicknesses may cause minor shifts in the resonance wavelength. Our numerical analysis indicates that small deviations (within ± 5–10 nm) have a limited effect on sensitivity and FoM, suggesting that the design is reasonably robust. These imperfections can be further minimized using advanced fabrication techniques such as EBL and atomic layer deposition (ALD), which offer nanometer-scale precision and uniformity. To analyze the electromagnetic response of the proposed biosensor, an equivalent circuit model (ECM) is employed as shown in Fig. 1(c). In this ECM, the lower Au layer is modeled as a short-circuit transmission line, with an impedance ZAu of zero. Similarly, the dielectric layer is represented as a transmission line with an impedance of Zd, which corresponds to SiO2. The monolayer graphene positioned on the top dielectric is modeled by impedance Zg. The DSER array on the top layer is represented by impedance Zm, consisting of parallel RLC circuits comprising resistors Rm, inductors Lm, and capacitors Cm. To obtain the R, L, and C component values, a curve fitting technique is utilized, similar to the given method in previous works30. The reflection coefficient Г is calculated as:

where Zin and Z0 are the input impedance of the proposed design and the impedance of free space, approximately 377 Ω, respectively18,30.

Optical analysis of the proposed biosensor

In this section, we present the numerical analysis performed to evaluate critical parameters, such as the conductivity of graphene, metamaterial properties, reflection, and absorption characteristics.

Graphene conductivity

Graphene plays a crucial role in biosensor design due to its exceptional optical, electrical, and surface properties, which enable strong light–matter interaction, high carrier mobility, and tunable plasmonic behavior. Equations (3)–(6) express the conductivity of graphene in terms of its potential, illustrating how the material’s electrical conductivity varies with changes in graphene potential and related factors22.

Where ε₀ is the vacuum permittivity, ω represents the angular frequency, and ℏ denotes Planck’s constant. Additionally, e represents the electron charge, while kB, σS, Г, T, µC, and ∆ correspond to Boltzmann’s constant, monolayer conductivity, scattering rate, ambient temperature, chemical potential, and graphene thickness, respectively. Detailed descriptions of these parameters are provided in22,31. Figure 3 illustrates the real and imaginary components of graphene’s conductivity as a function of wavelength at a temperature of 300 K, with chemical potential (µc) values ranging from 0.3 to 0.6 eV. Variations in µc significantly influence the conductivity of graphene, which, in turn, plays a crucial role in defining the overall design parameters.

Metamaterial analysis

The electromagnetic response of the proposed MM structure is analyzed in terms of its effective permittivity and permeability, which are extracted from the reflection and transmission coefficients (S₁₁ and S₂₁), as described in Eqs. (7)– (11)14. Based on these parameters, the impedance of the sensor is also calculated to evaluate its resonant characteristics.

In this context, k₀ denotes the wavenumber, and d represents the maximum thickness of the dielectric layer. In Eq. (8), the expressions [ln(eink₀d)]″ and [ln(eink₀d)]′ correspond to the imaginary and real parts of the complex logarithm, respectively. The sensor’s permittivity (ε) and permeability (µ) are determined by substituting the refractive index (n) and impedance (z) into Eqs. (10), and (11)14.

Figure 4 presents the real and imaginary parts of permittivity and permeability as functions of wavelength. Notably, both ε and µ exhibit negative real values over specific wavelength ranges, confirming the double-negative nature (DNG) of the structure. These DNG bands correspond to the electric and magnetic resonances generated by the double-split elliptical geometry, validating the presence of strong coupling and multimode resonance behavior within the designed biosensor.

Absorption and reflection analysis

Absorption and reflection are key parameters in evaluating the performance of the proposed MM biosensor. These quantities for different incident angles are calculated using Eqs. (12)– (18). The reflection characteristics of the sensor are derived from Eqs. (12)– (16), where the incident angle (θi) and wave vector (k) are defined as functions of the wavelength and frequency. The transmission and reflection coefficients are first obtained based on the electromagnetic boundary conditions at the interface31.

The graphene polarization tensor,\({\prod _{\mu v}}(\omega ,{\theta _i})\), with µ, v = 0, 1, 2, and \({\prod _{tr}}={\prod _\mu }\mu\), represents the interaction between the incident electromagnetic field and the graphene sheet, governing its surface conductivity. Using this tensor, the surface conductivity of graphene, σ(ω), can be expressed as a function of frequency and relaxation time, as shown in Eq. (13)31:

Once the surface conductivity is known, the reflection coefficient can be determined as a function of the incident angle and wave vector, as shown in Eq. (14)31:

The complex part of the reflection is then analyzed to account for the influence of both real and imaginary components of the conductivity, which directly affect the amplitude and phase of the reflected wave31:

For the case of normal incidence (θi = 0), the reflection of the incoming wave simplifies to Eq. (17) representing the basic reflection–transmission relationship31:

Finally, the overall absorption, A (ω), of the biosensor is calculated using the energy conservation relation as expressed in Eq. (18)31:

Equations (14)– (18) indicate that reflection is strongly dependent on conductivity. The incorporation of graphene significantly enhances field confinement and absorption, thereby improving the biosensor’s performance.

Results and discussions

This section presents a numerical analysis of the optical performance of the proposed design, with a focus on absorption, reflection, and the distributions of electric and magnetic fields. Figure 5 illustrates the absorption and reflection spectra of the design across the wavelength range of 650 nm to 1500 nm. For this analysis, the RI of the sensing layer is assumed to be 1 (n = 1). Within this wavelength range, five distinct resonance modes are identified: Mode 1 occurs at 942.92 nm, Mode 2 at 825.52 nm, Mode 3 at 773.75 nm, Mode 4 at 700.54 nm, and Mode 5 at 680.16 nm. The first resonance mode (Mode 1) demonstrates an absorption efficiency of approximately 90%, with a Full Width at Half Maximum (FWHM) bandwidth of 12.4 nm. The second resonance mode (Mode 2) shows an absorption efficiency of around 87%, accompanied by an FWHM bandwidth of 4.3 nm. The third resonance mode (Mode 3) has an absorption efficiency of about 58%, with an FWHM bandwidth of 1.9 nm. The fourth resonance mode (Mode 4) exhibits an absorption efficiency of approximately 92%, with an FWHM bandwidth of 4.2 nm. Lastly, the fifth resonance mode (Mode 5) shows an absorption efficiency of around 55%, with an FWHM bandwidth of 10.7 nm. Multiple resonance modes in the proposed design arise from the unique electromagnetic coupling of the DSER. The split gaps act as separate capacitive regions supporting localized plasmon oscillations, while the elliptical geometry introduces anisotropy and hybridized modes through near-field coupling. Interaction between the DSER’s localized plasmons and graphene’s tunable surface plasmon polaritons (SPPs) further enhances spectral splitting, resulting in multiple resonances that improve sensing accuracy and enable multi-channel detection. Graphene plays a key role in further enhancing and tuning these resonances. The optical conductivity of graphene, governed by the Kubo formula, is strongly dependent on the chemical potential. As µc increases, interaband transitions dominate, effectively shifting the resonance wavelength and improving confinement due to stronger plasmon–photon coupling at the interface. This tunability allows the sensor to adapt to different surrounding refractive indices without structural modification. Compared with conventional circular or rectangular resonators, the DSER geometry exhibits higher local field intensity because the dual gaps and curved boundaries concentrate the electric field within narrower regions. This strong field confinement directly contributes to the sensor’s high sensitivity, narrow bandwidth, and improved FoM. To assess the performance of the proposed design, the quality factor is calculated. The QF is defined as the ratio of the resonance wavelength (λr) to the bandwidth, expressed by the formula QF = λr/FWHM. The calculated QF values for the five modes are 76.04 for Mode 1, 191.98 for Mode 2, 407.23 for Mode 3, 166.79 for Mode 4, and 63.56 for Mode 5. The key advantage of the proposed design lies in the high QF values of its resonance modes, which result in narrow resonance bandwidths. This characteristic contributes to the high resolution of the sensor. The goal of this study is to develop a sensitive and high-resolution sensor, which is achieved by producing an absorption spectrum with sharply defined resonance modes. Each absorption peak corresponds to a resonant mode within the structure and can be finely tuned by adjusting the geometric parameters of the MM. The clarity and position of these peaks reflect the sensor’s sensitivity and selectivity, making it highly suitable for multi-frequency analysis in biosensing applications.

Figure 6 illustrates the distribution of electric and magnetic fields across different resonance modes of the proposed biosensor. In each of the five modes, the fields are predominantly concentrated within the gap of the SER. This localized field enhancement indicates that these modes are highly sensitive to any changes occurring in that specific region, thereby improving their sensitivity to variations in the RI. In modes 1, 3, 4, and 5, the electric and magnetic fields are more widely distributed across the distance between the DSER. This broader distribution enables these modes to respond to changes occurring in this area, potentially enhancing their sensitivity and FoM. The differences in field distribution among these modes highlight the biosensor’s versatility in detecting a wide range of changes within its structure. Moreover, in modes 2, 3, 4, and 5, the fields extend not only through the gap of the SER but also along the outer wall of the outer SER. This expanded distribution suggests that these modes can interact with changes occurring in both the gap and the outer surface of the SER. Such dual-area interaction can further enhance the sensor’s sensitivity and FoM by leveraging the combined effects from both regions. The enlarged interaction zone improves the biosensor’s ability to detect external alterations, while the varying field distributions underscore its adaptability in recognizing different types of structural modifications.

Optimization of parameters

The optical performance of the proposed biosensor is susceptible to its geometric configuration. In this section, a parametric analysis is conducted to examine the influence of key structural factors. These include the thickness of the SiO₂ layer (t₂), the thickness of the gold MM arrays (t₄), the widths of the inner (w₁) and outer (w₂) SERs, and the chemical potential of graphene (µc).

This analysis evaluates how these parameters affect the biosensor’s optical response. To begin the analysis, the thickness of the SiO₂ layer was varied between 100 nm and 500 nm, while all other parameters were kept constant. The resulting reflection spectra are shown in Fig. 7. As depicted in Fig. 7(a), increasing the SiO₂ layer thickness leads to a redshift in the resonance wavelengths. Within the wavelength range of 650 to 1500 nm, three distinct resonance modes are observed at SiO₂ thicknesses of 100 nm and 200 nm. When the thickness is increased to 300 nm, a fourth resonance mode emerges, and further increases to 400 nm and 500 nm result in the appearance of five resonance modes. Notably, at a SiO₂ thickness of 500 nm, the reflection intensity decreases, and the resonance bandwidth becomes narrower and more symmetric compared to the other thickness values. As shown in Fig. 7(b), the resonance wavelengths of all modes exhibit a nearly linear decrease with increasing t₂, while the sharpness of the resonance dips improves as t₂ increases. Based on these observations, a SiO₂ thickness of 500 nm was selected, as it provides reduced reflection and a narrower, more defined resonance bandwidth.

Next, Fig. 8(a) presents the reflection spectrum of the proposed biosensor for various thicknesses of the gold MM arrays (t₄), showing a redshift in the resonance wavelengths as t₄ increases. It was found that within the wavelength range of 650 to 1500 nm, five resonance modes are present for t₄ values between 100 nm and 300 nm. As illustrated in Fig. 8(b), the resonance wavelengths of all modes decrease almost linearly with increasing t₄. In biosensing applications, sharper and deeper resonance dips are generally preferred, as they contribute to higher detection resolution and accuracy. Therefore, a t₄ value of 100 nm was selected to optimize the sensor’s performance.

A monolayer of graphene is placed above the SiO₂ layer to enhance the sensor’s sensitivity. As shown in Fig. 9, varying the chemical potential of graphene from 0.1 eV to 0.9 eV influences the absorption peaks, with all other design parameters held constant. The highest absorption values are observed at µc = 0.9 eV for all resonance modes, reaching 0.90%, 0.87%, and 0.92% for modes 1, 2, and 4, respectively. Based on these peak values and the narrower resonance bandwidth at µc = 0.9 eV, this chemical potential is selected for optimal biosensor performance.

This section investigates the impact of the widths of the inner (w₁) and outer (w₂) SERs on the biosensor’s performance, as shown in Figs. 10 and 11, respectively. Figure 10 illustrates the effect of varying w₁ on the reflection spectrum and corresponding resonance wavelengths of the proposed biosensor. The width of w₁ is adjusted from 20 nm to 60 nm in 10 nm increments, while all other geometric parameters remain constant. As depicted, increasing w₁ leads to a blue shift in the resonance wavelengths. The lowest reflection for modes 1 and 4 is observed at w₁ = 40 nm, outperforming other values for these specific modes. Although mode 2 at w₁ = 30 nm, mode 3 at w₁ = 50 nm, and mode 5 at w₁ = 20 nm individually show slightly lower reflection values, they also cause an increase in reflection for modes 1 and 4. For optimal sensor performance, design parameters should minimize reflection while maintaining narrow resonance bandwidths. Based on this criterion, w₁ = 40 nm is selected to achieve a balanced and enhanced resonance response.

Figure 11 illustrates how variations in the width of the outer SER (w₂) affect the reflection spectrum and corresponding resonance wavelengths of the proposed biosensor. The parameter w₂ is varied from 20 nm to 60 nm in 10 nm increments, with all other geometric parameters held constant. The lowest reflection for modes 1 and 4 is observed at w₂ = 40 nm, outperforming other values for these specific modes. Although mode 2 at w₂ = 60 nm and modes 3 and 5 at w₂ = 20 nm show slightly lower reflection values individually, they also contribute to increased reflection in the other modes. Based on these results, w₂ = 40 nm is selected as the optimal value, as it minimizes overall reflection while achieving a narrower resonance bandwidth, thereby enhancing the sensor’s performance.

Sensing performance of the proposed biosensor

To evaluate the performance of the proposed biosensor, a test sample with a thickness of 100 nm is applied on top of the design. In the simulations, the RI of the sensing medium is varied to represent different types of cancer cells, including basal, breast, and cervical cancer cells. Figure 12 presents the absorption spectra of the biosensor for each cancer cell type. As shown, increasing the sample’s RI results in a noticeable shift in the resonance wavelengths, demonstrating the sensor’s sensitivity to RI variations. In this study, RI of the analyte was considered constant across the simulation wavelength range (650–1500 nm). This assumption is commonly adopted in optical biosensor modeling because the dispersion of most biological samples within this spectral region is minimal. The use of a fixed RI enables a straightforward evaluation of the sensor’s intrinsic wavelength shift response without the influence of spectral dispersion. However, in realistic scenarios, biological analytes may exhibit weak wavelength-dependent RIs. In future work, the model can be extended by incorporating wavelength-dependent RI values (e.g., using Cauchy or Sellmeier dispersion relations) further to validate the sensor’s performance under more practical conditions.

A critical metric for evaluating biosensor performance is sensitivity (S), defined as the ratio of the resonance wavelength shift (Δλ) to the change in refractive index (Δn), expressed by the equation S = Δλ/Δn17. As shown in Fig. 13, mode 1 exhibits the highest sensitivity for each cancer type: 450 nm/RIU for basal, 714.28 nm/RIU for breast, and 375 nm/RIU for cervical cancer cells. These high sensitivity values demonstrate the biosensor’s potential for medical diagnostic applications. It should be noted that the sensitivity of the proposed biosensor depends mainly on the geometrical parameters of the device. Among them, t₂, t₄, w₁, and w₂ exert the strongest influence on the resonance shift, while variations in µc enable active tuning of sensitivity. The selectivity of the biosensor is achieved through the multimode spectral response, where each biological analyte with a distinct RI produces a characteristic resonance shift. This feature allows reliable discrimination among different cell types or biochemical substances. In addition, the proposed biosensor exhibits good reliability, as simulation results show that small structural variations (± 5–10 nm) lead to negligible changes in the resonance wavelength and sensitivity. The combination of stable gold–graphene interfaces and multimode operation further ensures robust and reproducible sensing performance. Figure 13 also presents bar graphs of the biosensor’s performance metrics. Notably, the highest FoM and QF values, 110.38 1/RIU and 228.81, respectively, are achieved for breast cancer detection in mode 4. It is worth noting that the FoM depends on both sensitivity and the FWHM, and is defined as \(FoM=S/FWHM(1/RIU)\)13,18.

The FoM of the proposed biosensor can be improved by narrowing the resonator gaps, optimizing lattice periodicity, and tuning µc to enhance field confinement and resonance sharpness. Additionally, reducing metallic losses through high-quality gold deposition can further increase the QF, offering practical routes for future optimization. Table 1 provides the RI values for both cancerous and normal cells of each type, as reported in reference8. Additional performance metrics, including sensitivity, FoM, and QF, are summarized in Table 1.

Comparison of the proposed biosensor’s performance

To contextualize our results, we compare the proposed biosensor with other recent designs. Table 2 summarizes the key characteristics of various biosensor structures, including architecture, sensitivity, FoM, QF, and application scope. Our biosensor stands out as a tunable design that supports five distinct resonance modes within the 650–1500 nm wavelength range. These resonance wavelengths can be precisely adjusted by modifying the structural parameters of the resonators, offering enhanced flexibility and performance. The proposed biosensor is highly sensitive to RI variations, making it suitable for various biomedical applications, including cancer detection. Among the sensor configurations listed in Table 2, mode 1 of our proposed design demonstrates exceptional performance, achieving a high sensitivity of 714.28 nm/RIU. It also delivers a notable FoM of 51.02 1/RIU and a QF of 73.42, surpassing most comparable sensors. Mode 2 further highlights the design’s robustness with an impressive QF of 181.40, outperforming many existing alternatives. Additionally, modes 3 and 4 show strong capabilities, with sensitivities of 392.85 nm/RIU and 364.28 nm/RIU, FoMs of 75.55 1/RIU and 110.38 1/RIU, and QFs of 151.38 and 228.81, respectively. Mode 5 also maintains solid performance, with a QF of 103.22.

It’s important to highlight that while the study referenced in31 demonstrates the highest sensitivity, it has low FoM and QF values. Additionally, although the work discussed in2,13 achieves a higher sensitivity than our proposed design in modes 2 to 5, its FoM and QF values are significantly lower than those of our proposed structure. This work not only exhibits high sensitivity but also achieves an impressive FoM of 110.38 RIU⁻¹ for mode 4. This value significantly exceeds those reported in previous studies, which typically show FoM values ranging from 4.1 RIU⁻¹13 to 41.66 RIU⁻¹14, as summarized in Table 2. This remarkable FoM contributes to sharp resonance peaks and enhances spectral selectivity, both of which are essential for reliable RI sensing in biomedical applications. Additionally, our proposed biosensor achieves a QF of 228.81 for mode 4, surpassing the values reported for similar technologies, as presented in Table 2. For example, previously reported biosensors have exhibited QF values ranging from as low as 8.5317 to as high as 99.7514. This highlights the superior resonance characteristics and improved detection precision of our design. The proposed design supports multiple resonance modes; however, our analysis indicates that mode 1 demonstrates the highest sensitivity, along with favorable FoM and QF compared to the other modes. As a result, mode 1 is the most suitable operating point for biomedical applications. The existence of multi-resonance mode also offers flexibility for multi-analyte detection, enhancing the versatility of the sensor. The presence of five distinct absorption peaks provides additional spectral channels for sensing, representing a significant advancement over the single-mode operation common in many conventional plasmonic sensors. This multi-mode response is attributed to the unique geometry of the DSER and its array configuration. Together, these design elements significantly improve the performance of SPR-based biosensing and outperform previously reported sensor architectures.

Conclusion

In this study, a high-sensitivity multimode graphene-based MM biosensor was designed and numerically analyzed for refractive index sensing and biomedical applications. The proposed structure consists of a gold double-split elliptical resonator (DSER) array on a graphene-coated SiO₂ substrate, enabling strong field confinement and supporting multiple resonance modes that significantly enhance sensing performance. The results confirm that the multimode configuration provides improved detection versatility compared to conventional single-mode sensors, achieving a maximum sensitivity of 714.28 nm/RIU, a FoM of 51.02 1/RIU, and a QF of 73.42, outperforming many previously reported plasmonic and graphene-based sensors. These findings indicate that the DSER geometry, in conjunction with graphene’s tunable optical properties, offers a powerful platform for compact, label-free, and non-invasive biosensing. Future work will involve experimental fabrication and validation of the proposed biosensor, as well as incorporating wavelength-dependent analyte refractive indices and realistic material losses to assess its practical performance further. The results demonstrate that the proposed design is a strong candidate for next-generation optical biosensors with applications in biomedical diagnostics, environmental monitoring, and chemical detection.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings in this work are available from the corresponding author upon a reasonable request.

References

Azab, M. Y., Hameed, M. F. O., Nasr, A. M. & Obayya, S. S. A. Highly sensitive metamaterial biosensor for cancer early detection. IEEE Sens. J. 21 (6), 7748–7755 (2021).

Abdi, G. & Bahador, H. High sensitivity and optimum design of LSPR-based sensors by coupled nano-rings for cancer detection. Opt. Lasers Eng. 174, 107975 (2024).

Saadeldin, A. S., Hameed, M. F. O., Elkaramany, E. M. & Obayya, S. S. Highly sensitive Terahertz metamaterial sensor. IEEE Sens. J. 19 (18), 7993–7999 (2019).

Ghodrati, M., Mir, A. & Wen, J. Metamaterials and metasurfaces for sensor and biosensor applications. In Electromagnetic Wave Control Techniques of Metasurfaces and Metamaterials 61–105, (IGI Global, 2024) https://doi.org/10.4018/979-8-3693-2599-5.ch003.

Ghodrati, M., Mir, A. & Farmani, A. Numerical analysis of a surface plasmon resonance-based biosensor using molybdenum disulfide, molybdenum trioxide, and MXene for the diagnosis of diabetes. Diam. Relat. Mater. 132, 109633 (2023).

Liu, X. et al. Dual-band Terahertz toroidal metamaterial biosensor for detection of bovine serum albumin (BSA) with Ultra-high sensitivity. IEEE Sens. Journal 25(12), 21520–21527 (2025).

Bijalwan, A., Singh, B. K. & Rastogi, V. Analysis of a one-dimensional photonic crystal-based sensor for the detection of blood plasma and cancer cells. Optik 226, 165994 (2021).

Ayyanar, N., Raja, G. T., Sharma, M. & Kumar, D. S. Photonic crystal fiber-based refractive index sensor for early detection of cancer. IEEE Sens. J. 18 (17), 7093–7099 (2018).

Darmawan, D. A. B. Y., Tjipta, A. C. S., Agus, S. N. Y. & Sari, Y. M. Y. Design of Terahertz metamaterial biosensors for coronavirus detection. Int. J. Pharmaceut Sci. Rev. Res. 66, 131–139 (2020).

Ako, R. T., Lee, W. S., Bhaskaran, M., Sriram, S. & Ayachumnankul, W. Broadband and wide-angle reflective linear polarization converter for Terahertz waves. APL Photonics, 4(9), 096104. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5116149 (2019).

Ghodrati, M., Mir, A. & Farmani, A. Sensitivity enhancement of the surface plasmon resonance biosensor based on hybrid structure using MXene and MoS2 for refractive index sensing: an angular interrogation approach. Sens. Imaging. 25 (1), 39 (2024).

Ghodrati, M. & Uniyal, A. Exploring metasurface-based biosensor: new frontiers in sensitivity and versatility for biomedical applications. Plasmonics 20 (7), 5589–5608 (2025).

Khodaie, A. & Heidarzadeh, H. Design and analysis of a multi-modal refractive index plasmonic biosensor based on a split ring resonator for the detection of various cancer cells. Opt. Quant. Electron. 56 (9), 1439 (2024).

Ghodrati, M. & Sheikhi, A. Numerical analysis of a High-Sensitivity Graphene-Based SPR biosensor with a split elliptical metamaterial resonator for hemoglobin detection. IEEE Sens. Journal 25(15), 28012–28019 (2025).

Palik, E. D. (ed) Handbook of Optical Constants of Solids Vol. 3 (Academic, 1998).

Ordal, M. A., Bell, R. J., Alexander, R. W. Jr, Long, L. L. & Querry, M. R. Optical properties of fourteen metals in the infrared and Far infrared. W Appl. Opt. 24 (24), 4493–4499 (1985). : Al, Co, Cu, Au, Fe, Pb, Mo, Ni, Pd, Pt, Ag, Ti, V.

Alsalman, O. et al. Design of split ring resonator graphene metasurface sensor for efficient detection of brain tumor. Plasmonics 19 (1), 523–532 (2024).

Deng, R. et al. Theoretical analysis and design of ultrathin broadband optically transparent microwave metamaterial absorbers. Materials 11 (1), 107 (2018).

Vafapour, Z. et al. The potential of refractive index nanobiosensing using a multi-band optically tuned perfect light metamaterial absorber. IEEE Sens. J. 21 (12), 13786–13793 (2021).

Lotfi, F., Sang-Nourpour, N. & Kheradmand, R. All-optical tunable plasmonic biosensor made of graphene and metamaterial. Plasmonics 17 (2), 799–809 (2022).

Nejad, H. E., Mir, A. & Farmani, A. Supersensitive and tunable nano-biosensor for cancer detection. IEEE Sens. J. 19 (13), 4874–4881 (2019).

Patel, S. K. et al. Design of graphene metasurface based sensitive infrared biosensor. Sens. Actuators A: Phys. 301, 111767 (2020).

Ebadi, S. M., Örtegren, J., Bayati, M. S. & Ram, S. B. A multipurpose and highly-compact plasmonic filter based on metal-insulator-metal waveguides. IEEE Photonics J. 12 (3), 1–9 (2020).

Ben Salah, H., Hocini, A. & Bahri, H. Design and analysis of a Mid-Infrared Ultra-High sensitive sensor based on Metal-Insulator-Metal structure and its application for temperature and detection of Glucose. Progress in electromagnetics research M, 112, 81–91. (2022).

Lai, W. et al. Plasmonic filter and sensor based on a subwavelength end-coupled hexagonal resonator. Appl. Opt. 57 (22), 6369–6374 (2018).

Ben Salah, H., Hocini, A., Temmar, M. N. & Khedrouche, D. Design of mid infrared high sensitive metal-insulator-metal plasmonic sensor. Chin. J. Phys. 61, 86–97 (2019).

Danaie, M., Hajshahvaladi, L. & Ghaderpanah, E. A single-mode tunable plasmonic sensor based on an 8-shaped resonator for cancer cell detection. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 13976 (2023).

Azab, M. Y., Hameed, M. F. O., Mahdiraji, G. A., Adikan, F. R. M. & Obayya, S. S. A. Experimental and numerical characterization of a D-shaped PCF refractive index sensor. Opt. Quant. Electron. 54 (12), 846 (2022).

Li, L., Wu, S., Jin, M., Zheng, Y. & Liu, Y. Graphene-enhanced dielectric-metal hybrid structure for high performance LSPR sensing. Opt. Express. 32 (21), 37466–37479 (2024).

Oueslati, A., Hlali, A. & Zairi, H. Modeling of a metamaterial biosensor based on split ring resonators for cancer cells detection. In 2021, 18th International Multi-Conference on Systems, Signals & Devices (SSD). 392–396. (IEEE, 2021).

Patel, S. K. et al. Highly sensitive graphene-based refractive index biosensor using gold metasurface array. IEEE Photonics Technol. Lett. 32 (12), 681–684 (2020).

Khodaie, A., Heidarzadeh, H. & Harzand, F. V. Development of an advanced multimode refractive index plasmonic optical sensor utilizing split ring resonators for brain cancer cell detection. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 433 (2025).

Funding

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M. Gh., A. Sh., : software, data curation, investigation, conceptualization, methodology, writing - review and editing. M. Gh., A. Sh., : validation, data curation, writing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ghodrati, M., Sheikhi, A. Development of a high-sensitivity multimode graphene-based metamaterial biosensor with a double-split elliptical resonator for refractive index sensing and biomedical applications. Sci Rep 16, 2306 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32046-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32046-2