Abstract

The Combined Heat and Power Economic Dispatch (CHPED) problem represents a significant optimization challenge in modern power systems due to its inherent complexity arising from multiple operational constraints. This complexity is further exacerbated when considering the effect of power losses (PLs), valve-point loading effect (VPLE), and prohibited operating zones (POZs). Consequently, an efficient and robust optimization algorithm is essential for obtaining a globally optimal solution while satisfying all constraints. To address these challenges, this work evaluates the effectiveness of the Modified Dung Beetle Optimizer (MDBO) for solving the CHPED problem, considering PLs, VPLE, and POZs. The MDBO enhances the search process and mitigates the limitations of the conventional Dung Beetle Optimizer, particularly stagnation and premature convergence to local optima. The novelty in this paper is proposing a modified version of the traditional DBO (MDBO) by integrating three improvement strategies, including the fitness distance balance (FDB), Chaotic mutation (CM), and adaptive local search approach (ALSA), to solve the CHPED problem. The proposed MDBO has the ability to overcome the shortcomings of traditional DBO, such as its premature convergence and tendency to local optima. The effectiveness of the proposed MDBO has been evaluated on CHPED problems involving 4-unit, 7-unit, 24-unit, and 48-unit systems under various operating conditions. Moreover, MDBO performance has been rigorously assessed using standard benchmark test suites, including CEC-2019. The results demonstrate a significant reduction in operating costs, confirming the superior performance of the MDBO in comparison to existing optimization techniques like Sand Cat Swarm Optimizer (SCSO), African vultures optimization algorithm (AVOA), Sine Cosine Algorithm (SCA), Harris Hawks Optimization (HHO), Grey Wolf Optimizer (GWO), Liver cancer algorithm (LCA), Zebra Optimizer Algorithm (ZOA), and Whale Optimization Algorithm (WOA). Furthermore, the proposed algorithm consistently outperforms alternative methods reported in the literature, offering a more efficient and reliable solution for CHPED optimization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Background and problem context

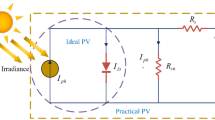

Combined Heat and Power (CHP) systems, also known as cogeneration systems, represent a highly efficient and sustainable energy solution applicable across diverse sectors. By producing electrical and thermal energy, CHP systems significantly enhance overall energy utilization and offer substantial environmental advantages. In the context of the global shift toward cleaner and more efficient energy technologies, CHP systems play a pivotal role in reducing greenhouse gas emissions, enhancing energy reliability, and delivering long-term economic benefits. Depending on the technology and its specific application, CHP systems can achieve efficiency levels ranging from 60% to over 80%.

CHP units are consistent with a wide diversity of fuel sources, involving natural gas, biogas, coal, oil, and renewable energy sources such as biomass and solar thermal energy. Unlike conventional power plants that lose a large part of input energy as heat during electricity generation, CHP systems recover and employ this thermal energy to meet heating demands, thereby pushing total system efficiency to nearly 90% 1,2. Moreover, CHP systems have the prospect to decrease total fuel costs by 10–40% and lower pollutant emissions by 13–18% 3. To completely harness the advantages of CHP systems, it is crucial to address the Combined Heat and Power Economic Dispatch (CHPED) issue, which involves determining the optimum cost-effective schedule for both power and heat generation under various operational constraints 4.

Research gap and motivation

Traditional optimization approaches for solving CHPED include the normal boundary intersection method 5, branch and bound 6, lagrangian approach 7,8, sequential quadratic programming 9, and benders method 10,11. However, these methods often depend heavily on initial conditions, require numerous iterations, and may not consistently converge to the global optimum. Additionally, they can be mathematically complex and computationally intensive.

As a result, heuristic and metaheuristic algorithms have emerged as powerful alternatives for solving CHPED problems. A comprehensive survey of heuristic methods for CHPED is presented in 12. Genetic Algorithm (GA)-based approaches have been widely applied to minimize total generation costs while taking into consideration valve-point-loading effects (VPLEs) and transmission power losses (PLs) 13. Enhanced GA variants featuring improved crossover and mutation strategies 14, as well as the Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II (NSGA-II) 15, have demonstrated effectiveness in handling mixed-variable scheduling tasks and integrating energy storage systems. Particle Swarm Optimizer (PSO) has been extensively employed for CHPED 16, with modifications such as time-varying acceleration coefficients to improve convergence behavior and prevent premature stagnation. VPLEs are often modeled using sinusoidal components added to the cost function. To address uncertainties in demand and renewable energy availability, PSO has been integrated with Monte Carlo simulations 17. Additionally, PSO has been utilized to assess dispatch strategies for reducing fuel consumption in coal-fired CHP plants 18.

Hybrid algorithms have been proposed to solve the CHPED problem. A hybrid PSO–NSGA-II approach simultaneously optimized both cost and emissions while incorporating transmission PLs 19. However, many of these methods have been validated only on small-scale systems (e.g., those comprising 5 to 7 units), limiting their generalizability. The Manta Ray Foraging Optimization (MRFO) has also been implemented to address generation scheduling in systems integrating wind power and VPLEs, achieving cost reductions of up to 8% across both small-scale (5-unit) and large-scale (96-unit) configurations under varying load conditions 20. The Cuckoo Search Optimizer (CSO) has emerged as a viable approach for addressing the CHPED issue 20,21,22,23. Its primary objective is to reduce overall fuel costs while meeting electricity and heat demands, considering constraints such as VPLEs and transmission PLs. In 21, CSO was tested on systems of various sizes, including small (5-unit), medium (24-unit), and large (48-unit) configurations. The 5-unit system was evaluated under three distinct heat and power demand scenarios. Similarly, the study in 22 demonstrated CSO’s effectiveness across six different test networks with 4, 5, 7, 11, 24, and 48 units. The methodology proposed in 23 was applied to five case studies, three involving quadratic cost functions without PLs, and two with non-convex cost functions. Several other metaheuristic approaches have also been employed to solve the CHPED problem, including the grey wolf optimizer (GWO) 24, heap-based optimization 2, group search optimization 25, gravitational search algorithm 26, marine predators algorithm 27, kho-kho optimization 28, a hybrid of weighted vertices-based approach and PSO 29. A mixed integer model was proposed to solve the CHPED for 4 units, 5-units, 24-unit, 48-unit, and 96 unit systems 30. An improved version of artificial rabbits optimization based on fitness distance balance was presented for solving the CHPED of 4-unit, 5-unit, 7-unit, 24-unit, 48-unit, 96-unit, and 192-unit systems 31. The artificial hummingbird algorithm based integrates a linear controlling strategy was developed to solve CHPED for different systems 32. An improved version of AVOA based orthogonal oppositional methodology was proposed to solve the CHPED for 48-unit system33. A hybrid optimizer based on Harris hawk’s optimizer (HHO), and imperialist competitive algorithm (ICA) was employed to solve the CHPED of 48-unit, 84-unit, and 96-unit systems 34.

It is worth mentioning here that metaheuristic optimization algorithms can solve several optimization problems where in a hybrid particle swarm optimizer was presented for optimal coordination of overcurrent relay 35 and it can be also applied for optimal placement of electric vehicle stations in distbution grids 36. A hybrid simulated annealing (SA) with particle swarm optimization (PSO) was utilized to control variable frequency drives37. Artificial intelligence (AI) was proposed for improving the accuracy of objective and physical pressure ratings 38. A fast sparse Bayesian learning algorithm was developed for superresolution and the coherent processing of multi-band radar data 38. In 39, a deep genetic algorithm was suggested for optimizing the channel for signal integrity. In 40, a Bayesian posterior loss function technique and a heuristic frequentist approach technique was proposed for to enhance the human decision making.

DBO a robust optimization algorithm that has been applied to solve different optimization problems 41. However, several modified versions of DBO were proposed to overcome the stagnation of the traditional DBO to local optima, premature convergence and its low performance where in 42, a modified DBO was presented based on Mean Differential Variation and Latin hypercube sampling. A multi-strategy was integrated to DBO based on Levy distribution, two separate cross operators, and Beta distribution to solve path planning problem 43. A t-distribution variation approach was applied to enhance the searching ability of the DBO to solve different optimization problems 44. Three improvement strategies were integrated to DBO to improve its performance including T-distribution mutation, differential evolutionary variation, cooperative search mechanism and cubic chaotic mapping 45. The fractional order calculus methodology was applied with DBO to boost its searching performance in image segmentation 46. At the end of this context, the performance of the DBO should be improved for solving large scale problems. Thus, in this paper, three improvement strategies were integrated into DBO to solve the CHPED problem including the fitness distance balance (FDB), Chaotic mutation (CM), and adaptive local search approach (ALSA).

The key contributions

From the previous review, the main associated gap of the applied methods for solving the CHPED is that some papers solved CHPED without considering VPLEs while some papers solved the CHPED with considering PLs only, and some papers solved the CHPED with considering the POZs only. The aim of the papers is to fill the research gap by solving the CHPED of small, medium and large-scale systems considering VPLEs, PLs, and POZs. In addition to that, a modified optimizer is presented to overcome the shortage of traditional DBO via integration of three improvements including ALSA, CM and FDB. Therefore, the contributions to this study can be depicted as follows:

-

New Modified Dung Beetle Optimizer (MDBO) is proposed to solve the CHPED based on boosting the exploitation and exploration of the conventional DBO using three strategies including ALSA, CM and FDB.

-

MDBO performance has been rigorously assessed using standard benchmark test and CEC-2019 suites to verify its efficiency and robust performance.

-

Solving the CHPED problem, considering PLs, VPLE, and POZs for 4 different test systems and the results obtained were compared with other optimization algorithms including SCSA, AVOA, SCA, HHO, GWO, LCA, ZOA, and WOA.

This article is structured as follows: Section "Problem Formulation" outlines the features of CHP units and formulates the economic dispatch problem using DBO and MDBO, considering VPLEs, PLs, and POZs. Section "Methodology" describes the test systems used for validation, followed by optimization outcomes presented in Section "Numerical Results". A comprehensive evaluation of the suggested approach is provided in Section "Conclusions", and the conclusions are summarized in Sect. 6.

Problem formulation

The objective of the CHPED problem is to achieve the lowest possible overall operational cost by optimally coordinating three categories of generation units: those producing only electricity, those generating solely heat, and CHP units. To evaluate different solutions, a fitness function is constructed, taking into account the amount of heat and power generated by each unit. The aggregate operational cost is then determined by summing the individual expenses associated with each type of generation unit, as outlined below:

where, \({N}_{p}\) refers to the units dedicated solely to electricity generation, \({N}_{u}\) signifies those units that produce only heat, and \({N}_{f}\) indicates the CHP units. The cost terms \({\text{cost }}_{i}^{P}\), \({\text{cost }}_{j}^{H}\), and \({\text{cost }}_{k}^{CHP}\) represent the cost of generation cost of \({i}^{th}\) power-only units, the \({j}^{th}\) heat-only unit, and the \({k}^{th}\) CHP unit. The cost functions for these units are expressed as follows:

-

For power-only units, cost was modeled using coefficients \({A}_{i}, {B}_{i}\), \({Q}_{i}, {T}_{i},\) and \({G}_{i}\), representing the cost parameters for \({i}^{th}\) electricity production units.

-

For heat-only units, cost was modeled using coefficients \({A}_{j}, {B}_{j}\), and \({Q}_{j}\), which account for the heat generation expenses.

-

For CHP units, cost was represented using coefficients \({A}_{k}, {B}_{k}{, Q}_{k}, {T}_{k}, {G}_{k}\), and \({V}_{k}\), which captures the combined cost of electricity and heat production for the \({k}^{th}\) units 47.

Constraints in the CHPED problem

The CHPED problem formulation includes both equality and inequality constraints to ensure energy balance and adherence to operational limits:

Equality constraints

The equality constraints include the power balanced with and without power losses asdescribed in Eqs. (5) and (6), as well as the heat balanced of hsystem as decribed in (7). In addation to that the equality constraints include the capacities of only-power units, heat-only units and the CHP units as depicted in (8), (9), and (10), respectivly. Furthermore, the prohibted zones of the generation units are described in (11).

where; Plosses is power losses, while Pdemand is the power demand.

The inequality constraints

Each power-only unit must operate within its designated generation limits. These constraints ensure that the power output from the \({i}^{th}\) unit stays within the allowable lower and upper bounds.

The heat output from each heat-only unit is restricted by its minimum and maximum generation capabilities.

where \({H}_{j}^{{f}_{Max}}\) and \({H}_{j}^{{f}_{Min}}\) represent the upper and lower restrictions of heat output from the \({j}^{th}\) unit, correspondingly.

The CHP units concurrently generate both heat and power, are also subject to operational limits.

The electrical power generation from the \({k}^{th}\) CHP unit must lie within the bounds \({P}_{j}^{{f}_{\text{Max }}}\) and \({P}_{j}^{{f}_{\text{Min }}}{H}_{k}^{f}\), which denote the lower and upper bounds of the power output capacity for the respective unit, respectively. Likewise, the heat output from the same CHP unit must fall within the limits \({H}_{j}^{{f}_{Min}} {P}_{k}^{f}\) \({H}_{j}^{{f}_{Max}} {P}_{k}^{c}\), which denote the minimum and maximum allowable heat generation from the \({k}^{th}\) CHP unit, respectively.Also, Certain regions within the power generation range are deemed infeasible due to operational constraints or safety considerations; these segments are referred to as POZs. The feasible power output range for the \({i}^{th}\) power-only unit is characterized in accordance with Eq. (16). Here, \({P}_{i}^{n,L}\) and \({P}_{i}^{n,U}\) represent the lower and upper limits of the \({n}^{th}\) POZ for the \({i}^{th}\) power-only unit, respectively, while \({Z}_{i}\) denotes the total count of such POZs associated with the unit.

Methodology

Dung beetle optimization (DBO)

The Dung Beetle Optimization (DBO) algorithm is a biologically inspired based metaheuristic that simulates the unique behaviors of the dung beetles. It incorporates four key activities: Rolling, Spawning, Foraging, and Stealing, which collectively guide the population of virtual dung beetles searching for optimal solutions.

Rollerball Dung Beetle (rolling)

Dung beetles roll dung balls in straight paths while navigating using sunlight. This behavior is modeled in DBO for updating the beetle’s position using Eq. (22) 41:

where: \({x}_{i}(tt)\) is the position of the ith beetle at time \((tt)\). \(\alpha\) determines if the beetle deviates from its original path (random directional factor, randomly set to 1 or -1). \(k\) is a deflection coefficient (between 0 and 0.2). \(b\) is a constant in the range [0, 1]. \(\Delta x\) simulates the beetle’s displacement toward the light source. If the beetle encounters an obstacle, it simulates directional change via a dancing behavior, modifying its position based on Eq. (23).

The angle θ ⊆ [0, π] determines direction adjustment, with no update occurring when θ = 0, π ∕ 2, and π.

Spawning behavior

Dung beetles choose safe zones for laying eggs. DBO models this through adaptive boundaries for local exploration:

where, \(L{b}^{*}\) and \(U{b}^{*}\) is the lower and upper constraints of the spawning region, \(Lb\) and \(Ub\) is the Original lower and upper constraints, \({X}^{*}\) is the current best solution, \(R\) is the decay factor over iterations, while \({T}_{max}\) is the maximum number of iterations.

The position update in spawning is defined by Eq. (22), using random values \(b1\) and \(b2\).

Foraging

Foraging simulates a global search for optimal solutions, influenced by the best global position, modeled as:

where \({X}^{b}\) is the best global position. The position update for foraging by:

where, \({c}_{1}\) is the normally distributed random number, and \({c}_{2}\) : random vector within [0, 1].

Stealing behavior

Some beetles exhibit kleptoparasitic behavior by stealing dung balls from others. This behavior is analogous to the exploitation process in optimization, where certain individuals mimic others to enhance convergence toward promising regions in the search space. In the algorithm, this behavior is modeled using the global best location \({X}^{b}\). The location update for a stealing beetle is given by:

where \(S\) is a constant (0.5), \(g\) is a random variable and \({X}^{*}\) is the best position globally.

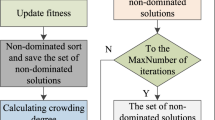

Modified Dung Beetle optimizer (MDBO) algorithm

To enhance the standard DBO’s performance, the proposed MDBO incorporates the following three key improvements:

Fitness distance balance (FDB)

FDB is designed to improve global exploration 48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56. In this approach, the populations positions are updated based on a score vector derived from their objective function and the distance between each population and the best solution. The score vector can be determined based on the normalized distance \(\text{norm}\left({DS}_{i}\right)\) and fitness values \(\text{norm}\left({F}_{i}\right)\) as follows:

where \(\text{D}\) and \(\text{F}\) represent the distance and the fitness vectors.

\(min\) and \(max\) are subscript denote the lower and maximum values, respectively. The score of each population (\({Sr}_{i})\) can be obtained as follows:

where, \({t}_{max}\) represents the maximum number of iterations permitted, while t denotes the iteration count currently being executed.

Chaotic mutation (CM)

Introduces chaos-based variation to prevent premature convergence and helps escape local optima, specifically in later phases of the search. The chaotic mutation (CM) mechanism enhances the exploration capability of the proposed optimizer by assigning new solution positions based on principles from chaos theory 57. Specifically, the logistic chaotic map is employed for this mutation process, as defined in 58,59:

where \(\tau^{\prime }\) refers to the logistic chaotic paramter in which \(\tau^{\prime } \ne \left\{ {0.0, 0.25, 0.75, 0.5, 1.0} \right\}\). \(\tau\) represents random paramter between 0 and 1. \(\mu\) equals to 4.

Adaptive local search approach (ALSA)

The Adaptive Local Search Algorithm (ALSA) is designed to improve the local exploitation capability by updating each agent’s position relative to the current best solution. During the iteration process, the population members are adjusted according to:

where \(rand\) is a random value in the range of [0,1].

This adaptive mechanism ensures that agents remain locally focused on the best-known position while retaining randomness for exploration. Figure 1 illustrates the population update mechanism based on ALSA. A pseudo code the proposed MDBO is depicted in algorithm 1.

The pseudo code of the proposed MDO is presented in Algorithm1.

Numerical results

Validation and analysis of simulation

This section presents and evaluates the performance of the proposed MDBO in solving the CHPED problem for different test systems, including four, seven, twenty-four-unit, and forty-eight configurations. Initially, the MDBO is benchmarked against 23 standard test functions and the CEC-2019 test suite. The description of standard functions is given in 60,61 while the description of CEC-2019 functions is provided in 62,63. Its performance is compared with nine state-of-the-art optimization algorithms, namely: Whale Optimization Algorithm (WOA) 64, Sand Cat Swarm Optimization (SCSO) 65, Zebra Optimization Algorithm (ZOA)66, African Vultures Optimization Algorithm (AVOA) 67, Grey Wolf Optimizer (GWO) 68, Harris Hawks Optimization (HHO)69, Liver Cancer Algorithm (LCA) 70, and Dung Beetle Optimizer (DBO) 41. All simulations were executed using MATLAB 2021b on a Core i7 processor (2.5 GHz, 8 GB RAM). Table 1 summarizes the parameter settings of the comparative optimization algorithms.

Benchmark validation

To validate the effectiveness of MDBO compared to the statistical outcomes of other methods (provided in Table 1), extensive experiments were conducted using two widely accepted benchmark suites. The statistical evaluation includes convergence curves, box plots, and non-parametric significance tests, such as the Wilcoxon rank-sum test and Friedman’s mean rank test.

Statistical analysis

The statistical performance of MDBO and the comparative algorithms is presented in Table 2 for the 23 standard benchmark functions and Table 3 for the CEC-2019 suite. The metrics considered include average, best, and worst, standard deviation and simulation time of the obtained results. Across most test functions, MDBO demonstrated superior performance in terms of average and best values, indicating its effectiveness and robustness. However, the computational time of the proposed MDBO is the highest compared to the original DBO and the other optimization algorithms due to the three integrated modifications.

Convergence analysis

The convergence carve of the comparative optimizers for the standard benchmark functions and CEC-2019 are displayed in Figs. 2 and 3, respectively. According to Fig. 2, the proposed MDBO has stable and fast convergence characteristics compared to the other optimization algorithms for most benchmark functions where there is notable difference especially for F1 to F6, F14, F15, F21, F22, and F23 while the convergence of F5, F6, and F12 the AVOA is the best and for F9, the WOA is the best. Likewise, the convergence of the MDBO is the best compared to other optimization techniques for CEC-2019 functions as depicted in Fig. 3, except the AVOA is the best for CEC06 and ZOA is the best for CEC08, and CEC09 while the GWO is the best for CEC10.

Boxplot analysis

Boxplot is a visual representation of obtained results by the comparative optimizers to test the performance and verify the effectiveness of the proposed optimizer. It is worth mentioning here that the narrowest boxplot means that there is no massive difference between the results obtained. Figure 4 and Fig. 5 shows the boxplot of the comparative optimizers for the classic and CEC-2019 functions, respectively. As depicted in Figs. 4 and 5, the MDBO has the narrowest boxplot for most functions.

Wilcoxon rank-sum test

The Wilcoxon rank-sum test, also known as the Mann–Whitney U test, is applied to statistically verify significant differences in performance. This non-parametric test is suitable for small or non-normally distributed datasets, comparing medians instead of means. The p-values of Wilcoxon test results which obtained from testing both benchmark suites are summarized in Table 4 for standard benchmarks and Table 5 for CEC-2019 suite. Most comparisons show statistically significant improvements by MDBO, supporting its efficacy over existing methods.

Friedman mean rank test

The Friedman mean rank test serves as a non-parametric statistical tool designed to assess the significance of differences among several optimization algorithms by evaluating their average rankings across a set of benchmark functions. Figures 6 and 7 illustrate the Friedman mean rank values obtained from two distinct benchmark suites. The results demonstrate that the proposed MDBO consistently secures the lowest mean rank, reflecting its superior performance relative to contemporary optimization methods. In contrast, the Sine Cosine Algorithm (SCA) exhibits the highest mean rank, indicating the least favorable performance within this comparative framework.

Application of MDBO for different CHPED test systems

This section focuses on applying the proposed MDBO to solve four CHPED test systems: 4-unit, 7-unit, 24-unit, and 48-unit configurations. Table A.1 in Appendix A presents the specifications of the studied systems. The simulation setup (including the number of agents, iterations, and runs) remains consistent across all test systems for a fair comparison, following the parameters listed in Table 1.

Test system-1 (4-unit system)

The first test system consists of four generating units, including a single power-only unit, two CHP units, and one heat-only unit. This configuration is required to satisfy an electrical demand of 200 MW and a thermal demand of 115 MWth. The parameters defining the cost functions are details are taken from 71, while the permissible operating regions for the CHP units are depicted in Figs. 8 and 9.

In this configuration, power losses (Ploss), VPLE, and POZs are not considered. The aim is to minimize the whole operational cost without losses. Simulations were conducted using MDBO and other optimization methods. Table 6 presents the statistical outcomes (best, average, worst) for the 4-unit system, where the best average and optimal response are attained by the MDBO to decrease the entire cost of the system. Indeed, Table 7 provides comparative performance results. Figures 10 and 11 show the convergence trends and boxplot comparisons, where the efficient and stable response was observed by the proposed MDBO.

According to Tables 6 and 7, the lowest operational cost achieved by the MDBO was $9,257.1, outperforming (lower than) other algorithms by varying ratios: SCSO (0.0011%), SCA (0.0248%), HHO (0.0992%), GWO (0.0054%), LCA (0.504%), ZOA (0.0151%), WOA (0.1919%), RGA (0.0667%), ARO (0.00106%), GA2 (2.064%), GA1 (0.1089%), ACSA (2.0641%). It is noted here that some results for this case, the values observed were identical because of the low population size and iteration, but overall, the response of the proposed optimizer is observed to be better than the other state-of-the-art techniques.

Table B.1 in Appendix B shows the optimal scheduling outcomes for this test case. The solutions obtained by MDBO adhered to all operational constraints, with no violations observed.

Test system-2 (7-unit system)

This system is composed of a total of seven generating units, comprising four power-only units, two CHP units, and one heat-only unit. It is tasked with fulfilling a power demand of 600 MW alongside a thermal demand of 150 MWth. This system is analyzed under three distinct operational scenarios:

-

Case 1: CHPED with VPLE,

-

Case 2: CHPED with VPLE and PLs,

-

Case 3: CHPED with VPLE, PLs, and POZs.

The cost function parameters are taken from reference 71, and a comprehensive discussion of the findings from these three cases is provided in the upcoming subsections.

CASE-1: CHPED with VPLE

In this case, only the VPLE was incorporated into the CHPED formulation. Simulations were performed using the MDBO and several comparative optimization algorithms under the same parameter settings. The statistical performance results are reported in Table 8. MDBO achieves the most cost-effective and consistent outcomes.

Figures 12 and 13 illustrate the convergence curves and boxplot responses obtained by various optimizers for minimizing the cost function. These figures demonstrate that the MDBO exhibits faster convergence and lower variability, indicating a more reliable and stable solution trajectory compared to the competing methods.

According to Tables 8 and 9, the MDBO achieved the lowest total generation cost of $10,091.92, outperforming several state-of-the-art optimizers. Specifically, the cost obtained by MDBO was lower than those of DBO by 0.502%, SCSO by 0.247%, AVOA by 0.249%, SCA by 1.204%, HHO by 0.890%, GWO by 0.127%, LLCA and LCA by 0.199%, ZOA by 0.516%, WOA by 0.625%, MRFO by 0.0041%, and ARO by 0.3051%. These results clearly demonstrate MDBO’s superior performance in minimizing total generation cost under the system conditions considered.

Table C.1 in Appendix C presents the optimal CHPED scheduling for the studied 7-unit system, considering the VPLE. The optimal schedule further validates MDBO’s robustness in addressing the nonlinearities and constraints introduced by VPLE, highlighting its potential for practical deployment in complex CHPED problems.

CASE-2: CHPED with VPLE and PL

In the second case of Test System-2, the VPLE and transmission PLs were both considered. This scenario adds complexity by considering real power losses, making it more representative of practical CHPED applications. To ensure a consistent comparison, the same simulation parameters were applied across all algorithms. The statistical results of various optimization techniques, including the proposed MDBO, are presented in Table 10. Among the examined algorithms, MDBO consistently produced the best cost outcomes with faster convergence and a more reliable distribution of results.

Figures 14 and 15 illustrate the convergence behavior and boxplot distributions of the cost function achieved by various optimization algorithms considering VPLEs and PLs constraints. The proposed MDBO demonstrated both efficient and stable performance, achieving the lowest total system cost. As illustrated in these figures, the MDBO algorithm demonstrated a notably faster convergence rate relative to the other methods while simultaneously preserving a high degree of solution consistency, as evidenced by the diminished variability observed over multiple execution runs.

According to Tables 10 and 11, the minimum cost achieved by MDBO was $10,215.61, which was superior to those attained by the other optimizers. The corresponding percentage differences were: DBO (0.504%), SCSO (0.210%), AVOA (0.210%), SCA (1.118%), HHO (0.707%), GWO (0.0805%), LCA (0.167%), ZOA (0.488%), WOA (0.549%), MRFO (0.0037%), ARO (0.2806%).

Table D1 in Appendix D shows the optimal CHPED scheduling for the studied 7-unit system, considering both VPLEs and PLs. The table compares results from various optimization algorithms, highlighting how the proposed MDBO performs in comparison to others. The results under this scenario highlight the robustness and adaptability of MDBO in handling the complex constraints of the CHPED model, effectively addressing both VPLE and PLs simultaneously.

CASE-3: CHPED with VPLE, PLs, and POZs

The third and most complex case incorporates all major nonlinearities, VPLEs, PLs, and POZs, into the CHPED model, resulting in a highly constrained and realistic optimization scenario. The transmission loss coefficients (B-matrix) used are the same as those in Case 2 of Test System 3, as defined in Eq. (21), while the parameters for the POZs are details taken from the reference 71.

The inclusion of POZs introduces non-convex constraints, which can lead traditional optimization algorithms to suffer from premature convergence or entrapment in local optima. This case, therefore, provides a comprehensive benchmark for evaluating the robustness and effectiveness of the MDBO in handling real-world operational complexities. The optimization performance of MDBO was benchmarked against several state-of-the-art algorithms, with statistical comparisons presented in Table 12. MDBO successfully achieved both the lowest average fuel cost and the best optimal solution, demonstrating its superior capability in addressing the challenges posed by this highly constrained CHPED problem.

Figures 16 and 17 illustrate the convergence behavior and boxplot distributions of the cost minimization results obtained by MDBO and other studied benchmark optimizers for the CHPED system incorporating VPLEs, PLs, and POZs. The proposed MDBO demonstrates both efficiency and stability, consistently achieving lower cost values in this highly constrained scenario. As shown in these figures, MDBO exhibits rapid convergence and strong reliability, even in the presence of complex non-linear and non-convex constraints, further validating its robustness and effectiveness in solving real-world CHPED problems.

As shown in Tables 12 and 13, the cost obtained using MDBO was 10,101.28$, outperforming all other techniques with cost differences as follows: DBO (0.445%), SCSO (0.508%), AVOA (0.523%), SCA (1.198%), HHO (0.634%), GWO (0.159%), LCA (1.154%), ZOA (0.581%), WOA (0.784%), HTS (0.0296%), BLPSO (0.00028%), NDE (0.0324%), ARO (0.139%), GSO (0.0007%), and IGA-NCM (0.134%).

Table E1 in Appendix E presents the optimal CHPED scheduling for the studied 7-unit system, considering VPLEs, PLs, and POZs. The table compares the results obtained using several optimization algorithms, including the proposed MDBO, to clarify the performance differences among these algorithms. It is important to note that, across all three cases of Test System 2 (as detailed in Tables C.1, D.1, and E.1), no constraint violations were observed. All system requirements were fully satisfied, confirming the validity of the solutions obtained. This demonstrates the reliability of MDBO in effectively handling complex, multi-constrained CHPED problems, reinforcing its suitability for real-world applications.

Test system-3 (24-unit system)

The third test system consists of a CHPED system comprising 24 generating units, which include 13 power-only units, 6 CHP units, and 5 heat-only units. The system is required to meet 2,350 MW of electrical power and 1,250 MWth of thermal demand. The cost coefficients and operational limits for this system are details taken from reference 71, while the feasibility boundaries of CHP units are depicted in Figs. 18–21. The objective of this test case is to minimize the total operating cost, with cost functions that account for power transmission losses.

The simulations for this large-scale CHPED case were conducted using the input parameters specified in Table 1, applying various optimization algorithms, including the proposed MDBO. This complex test case includes PLs, making it a challenging benchmark for assessing the scalability and robustness of optimization techniques. The statistical results of each optimizer, comprising the average, best, and worst cost values, are summarized in Table 14. As shown, the proposed MDBO achieved the lowest average and optimal cost, demonstrating its superior performance.

Figures 22 and 23 illustrate the convergence trajectories and boxplot representations of the outcomes produced by the different optimization algorithms under study. The proposed MDBO algorithm exhibited not only accelerated convergence but also robust and stable performance, consistently attaining the optimal solution for the CHPED problem.

The results presented in Table 14 underscore the superior performance of the proposed MDBO algorithm, which achieved the lowest and best and average cost values among all evaluated optimizers. This outcome highlights the effectiveness of MDBO in solving large-scale, multivariable CHPED problems with nonlinear constraints. According to Tables 14 and 15, MDBO achieved a total cost of $57,803.47, outperforming all other compared algorithms. The percentage differences in cost relative to MDBO are as follows: DBO (0.747%), SCSO (2.006%), AVOA (1.292%), SCA (8.616%), HHO (2.309%), GWO (0.340%), LLCA (5.198%), ZOA (2.748%), WOA (3.438%), TLBO (0.351%), OTLBO (0.091%), RCGA-IMM (0.453%), ARO (0.104%), MGSO (0.033%), SGWO (0.419%), HBOA (0.329%), SNS (0.161%), OGSO (0.044%), GSA (0.548%), EMA (0.038%), GSO (0.549%), CPSO (3.235%), TVAC-PSO (0.548%), AFDB-ARO (0.0382%), IGA-NCM (0.391%), ACS-DEM (0.163%), IHT (0.259%), NDE (0.0427%), and IGSO (0.423%). These results demonstrate MDBO’s outstanding capability in delivering cost-effective and reliable solutions for complex CHPED systems.

The optimal CHPED schedules, accounting for power losses, were obtained using the various studied optimization algorithms, including the proposed MDBO, and are presented in Table 16. During the solution process for this large-scale CHPED system, no constraint violations were observed, and all operational limits were strictly adhered to. These results confirm the feasibility, accuracy, and robustness of all optimization methods evaluated, particularly the MDBO, which demonstrated high reliability in producing constraint-compliant solutions under complex system conditions.

Test system-4 (48-unit system)

The fourth studied test system consists of 48 generating units, including 26 power-only units, 12 CHP units, and 10 heat-only units. This configuration is required to satisfy an electrical demand of 4700 MW and a thermal demand of 2500 MWth. The parameters defining the cost functions are details are taken from 71. The objective of this test case is to minimize the total operating cost, with cost functions that account for VPLE and POZs. The simulations for this large-scale CHPED case were conducted and listed in Table 17, applying various optimization algorithms, including the proposed MDBO. This complex test case includes VPLE and POZs, making it a challenging benchmark for assessing the scalability and robustness of optimization techniques.

The optimal CHPED schedules, accounting for VPLE and POZs, were obtained using the various studied optimization algorithms, including the proposed MDBO, and are presented in Table 17. During the solution process for this large-scale CHPED system, no constraint violations were observed, and all operational limits were strictly adhered to. These results confirm the feasibility, accuracy, and robustness of all optimization methods evaluated, particularly the MDBO, which demonstrated high reliability in producing constraint-compliant solutions under complex system conditions. Also, the presented results underscore the superior performance of the proposed MDBO algorithm, which achieved the lowest total cost value among all evaluated optimizers. This outcome highlights the effectiveness of MDBO in solving large-scale, multivariable CHPED problems with nonlinear constraints.

-

Finally, according to the results obtained of the standard of the CEC-2019 benchmark functions the MDBO has the best performance compared to SCSA, AVOA, SCA, HHO, GWO, LCA, ZOA, and WOA in terms of the statistical results of Tables 2 and 3. Furthermore, the MDBO has stable and speed convergence characteristics compared to the comparative algorithms as depicted in Figs. 2 and 3.

-

The MDBO is superior optimizer to solve the CHPED in which the minimum operating costs were obtained compared to the other optimization algorithms for the small, the medium and the large test systems. The minimum operation cost by MDBO for the 4-unit system is 9257.1 $. The minimum operation costs for 7-unit test system with VPLE is 10,091.92 $, the minimum cost with VPLE and PLs is 10,094.21 $ and, the minimum cost with VPLE, PLs, and POZs is 10,101.28 $. The minimum cost of 24-Unit System with 57,803.47 $. The minimum cost with 48-unit system is system considering VPLE and POZs is 117,952 $.

Conclusions

This study critically examined the capability of the Modified Dung Beetle Optimizer (MDBO) in addressing the Combined Heat and Power Economic Dispatch (CHPED) problem, incorporating practical operational constraints such as transmission power losses (PLs), valve-point loading effects (VPLEs), and prohibited operating zones (POZs). The MDBO was developed to surmount common shortcomings of traditional metaheuristic algorithms, notably premature convergence and stagnation in the search process. By effectively enhancing the balance between exploration and exploitation phases, the MDBO demonstrated superior optimization performance. Its effectiveness was rigorously tested on four benchmark systems of CHPED problem of varying complexity: a 4-unit, a 7-unit, a 24-unit, and a 48-unit configuration. Extensive comparative analyses were performed against a broad spectrum of contemporary optimization algorithms, including Whale Optimization Algorithm (WOA), Sand Cat Swarm Optimization (SCSO), Zebra Optimization Algorithm (ZOA), African Vultures Optimization Algorithm (AVOA), Grey Wolf Optimizer (GWO), Harris Hawks Optimization (HHO), Liver Cancer Algorithm (LCA), and the original Dung Beetle Optimizer (DBO). The findings revealed that MDBO consistently outperformed these approaches by achieving lower total operational costs, accelerated convergence rates, and entirely feasible solutions across all test cases. Further, the robustness and scalability of MDBO were substantiated through evaluations using benchmark functions from the CEC-2019 suite, affirming its efficacy as a potent and dependable optimization method suitable for both small- and large-scale CHPED applications. In future work, incorporating the demand of electric vehicles and energy storage systems can be included in solving the CHPED problem.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article.

Code availability

The code is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AIS:

-

Artificial immune system

- ARO:

-

Artificial rabbits’ optimization

- BCO:

-

Bee colony optimization

- BLPSO:

-

Biogeography-based learning particle swarm optimization.

- CFDBSDO:

-

Chaotic map-based fitness-distance balance supply–demand optimization algorithm

- CHP:

-

Combined Heat and Power

- CHPED:

-

Combined Heat and Power Economic Dispatch

- DBO:

-

Dung Beetle Optimizer

- EMA:

-

Exchange market algorithm

- GA1:

-

Genetic Algorithm 1

- GA2:

-

Genetic Algorithm 2

- GSA:

-

Gravitational search algorithm

- GSO:

-

Group search optimization

- HTS:

-

Heat transfer search algorithm

- IACSA:

-

Improved ant colony search algorithm

- IGA-NCM:

-

Improved genetic algorithm with novel crossover and mutation operators.

- LCA:

-

Line-up competition algorithm

- MDBO:

-

Modified Dung Beetle Optimizer

- MGSO:

-

Modified group search optimizer

- MRFO:

-

Manta ray foraging optimization algorithm

- NDE:

-

Niching differential evolution algorithm

- OTLBO:

-

Oppositional teaching learning-based optimization

- PLs:

-

Power Losses

- POZs:

-

Prohibited Operating Zones

- RCGA-IMM:

-

Real coded genetic algorithm with improved mühlenbein mutation

- SPSO:

-

Selective particle swarm optimization.

- TLBO:

-

Oppositional teaching learning-based optimization

- TVAC-PSO:

-

Time varying acceleration coefficients particle swarm optimization

- VPLE:

-

Valve-Point-Loading-Effect

References

Liu, C., Shahidehpour, M., Li, Z. & Fotuhi-Firuzabad, M. Component and mode models for the short-term scheduling of combined-cycle units. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 24(2), 976–990 (2009).

Ginidi, A. R., Elsayed, A. M., Shaheen, A. M., Elattar, E. E. & El-Sehiemy, R. A. A novel heap-based optimizer for scheduling of large-scale combined heat and power economic dispatch. IEEE Access 9, 83695–83708 (2021).

Chen, X., Li, K., Xu, B. & Yang, Z. Biogeography-based learning particle swarm optimization for combined heat and power economic dispatch problem. Knowl.-Based Syst. 208, 106463 (2020).

Rigo-Mariani, R. et al. A combined cycle gas turbine model for heat and power dispatch subject to grid constraints. IEEE Transactions on Sustainable Energy 11(1), 448–456 (2019).

Ahmadi, A., Moghimi, H., Nezhad, A. E., Agelidis, V. G. & Sharaf, A. M. Multi-objective economic emission dispatch considering combined heat and power by normal boundary intersection method. Electric Power Systems Research 129, 32–43 (2015).

Rong, A. & Lahdelma, R. An efficient envelope-based Branch and Bound algorithm for non-convex combined heat and power production planning. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 183(1), 412–431 (2007).

Sashirekha, A., Pasupuleti, J., Moin, N. & Tan, C. S. Combined heat and power (CHP) economic dispatch solved using Lagrangian relaxation with surrogate subgradient multiplier updates. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 44(1), 421–430 (2013).

Guo, T., Henwood, M. I. & Van Ooijen, M. An algorithm for combined heat and power economic dispatch. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 11(4), 1778–1784 (1996).

M. G. Chapa and J. V. Galaz, "An economic dispatch algorithm for cogeneration systems," in IEEE Power Engineering Society General Meeting, 2004., 2004, pp. 989–994: IEEE.

Lin, C., Wu, W., Zhang, B. & Sun, Y. Decentralized solution for combined heat and power dispatch through benders decomposition. IEEE Transactions on Sustainable Energy 8(4), 1361–1372 (2017).

Sadeghian, H. & Ardehali, M. A novel approach for optimal economic dispatch scheduling of integrated combined heat and power systems for maximum economic profit and minimum environmental emissions based on Benders decomposition. Energy 102, 10–23 (2016).

Nazari-Heris, M., Mohammadi-Ivatloo, B. & Gharehpetian, G. A comprehensive review of heuristic optimization algorithms for optimal combined heat and power dispatch from economic and environmental perspectives. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 81, 2128–2143 (2018).

Haghrah, A., Nazari-Heris, M. & Mohammadi-Ivatloo, B. Solving combined heat and power economic dispatch problem using real coded genetic algorithm with improved Mühlenbein mutation. Appl. Therm. Eng. 99, 465–475 (2016).

Zou, D., Li, S., Kong, X., Ouyang, H. & Li, Z. Solving the combined heat and power economic dispatch problems by an improved genetic algorithm and a new constraint handling strategy. Appl. Energy 237, 646–670 (2019).

Shang, C., Srinivasan, D. & Reindl, T. Generation and storage scheduling of combined heat and power. Energy 124, 693–705 (2017).

Mohammadi-Ivatloo, B., Moradi-Dalvand, M. & Rabiee, A. Combined heat and power economic dispatch problem solution using particle swarm optimization with time varying acceleration coefficients. Electric Power Systems Research 95, 9–18 (2013).

Y. ali Shaabani, A. R. Seifi, and M. J. Kouhanjani, "Stochastic multi-objective optimization of combined heat and power economic/emission dispatch," Energy, vol. 141, pp. 1892–1904, 2017.

Liu, M., Wang, S. & Yan, J. Operation scheduling of a coal-fired CHP station integrated with power-to-heat devices with detail CHP unit models by particle swarm optimization algorithm. Energy 214, 119022 (2021).

Sundaram, A. Combined heat and power economic emission dispatch using hybrid NSGA II-MOPSO algorithm incorporating an effective constraint handling mechanism. IEEE Access 8, 13748–13768 (2020).

Shaheen, A. M., Ginidi, A. R., El-Sehiemy, R. A. & Elattar, E. E. Optimal economic power and heat dispatch in Cogeneration Systems including wind power. Energy 225, 120263 (2021).

Mehdinejad, M., Mohammadi-Ivatloo, B. & Dadashzadeh-Bonab, R. Energy production cost minimization in a combined heat and power generation systems using cuckoo optimization algorithm. Energ. Effi. 10, 81–96 (2017).

Nguyen, T. T., Nguyen, T. T. & Vo, D. N. An effective cuckoo search algorithm for large-scale combined heat and power economic dispatch problem. Neural Comput. Appl. 30, 3545–3564 (2018).

Nguyen, T. T., Vo, D. N. & Dinh, B. H. Cuckoo search algorithm for combined heat and power economic dispatch. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 81, 204–214 (2016).

Jayakumar, N., Subramanian, S., Ganesan, S. & Elanchezhian, E. Grey wolf optimization for combined heat and power dispatch with cogeneration systems. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 74, 252–264 (2016).

Beigvand, S. D., Abdi, H. & La Scala, M. Combined heat and power economic dispatch problem using gravitational search algorithm. Electric Power Systems Research 133, 160–172 (2016).

Davoodi, E., Zare, K. & Babaei, E. A GSO-based algorithm for combined heat and power dispatch problem with modified scrounger and ranger operators. Appl. Therm. Eng. 120, 36–48 (2017).

Srivastava, A. & Das, D. K. A new Kho-Kho optimization Algorithm: An application to solve combined emission economic dispatch and combined heat and power economic dispatch problem. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 94, 103763 (2020).

Shaheen, A. M. et al. A novel improved marine predators algorithm for combined heat and power economic dispatch problem. Alex. Eng. J. 61(3), 1834–1851 (2022).

Dolatabadi, S., El-Sehiemy, R. A. & GhassemZadeh, S. Scheduling of combined heat and generation outputs in power systems using a new hybrid multi-objective optimization algorithm. Neural Comput. Appl. 32(14), 10741–10757 (2020).

Hasanabadi, R. & Sharifzadeh, H. Solving combined heat and power economic dispatch using a mixed integer model. J. Clean. Prod. 444, 141160 (2024).

Ozkaya, B., Duman, S., Kahraman, H. T. & Guvenc, U. Optimal solution of the combined heat and power economic dispatch problem by adaptive fitness-distance balance based artificial rabbits optimization algorithm. Expert Syst. Appl. 238, 122272 (2024).

Shaheen, A. M., Ginidi, A. R., Alassaf, A. & Alsaleh, I. Developing artificial hummingbird algorithm with linear controlling strategy and diversified territorial foraging tactics for combined heat and power dispatch. Alex. Eng. J. 105, 245–260 (2024).

Rizk-Allah, R. M., Snášel, V. & Hassanien, A. E. Multi-orthogonal-oppositional enhanced African vultures optimization for combined heat and power economic dispatch under uncertainty. Neural Comput. Appl. 37(8), 6097–6123 (2025).

Nazari, A. & Abdi, H. Solving the combined heat and power economic dispatch problem in different scale systems using the imperialist competitive Harris Hawks optimization algorithm. Biomimetics 8(8), 587 (2023).

Habib, K., Wadood, A., Wei, T., Khan, S. & Xing, X. Optimal coordination of directional overcurrent protection relays using hybrid optimizer. Engineering Research Express 6(2), 025330 (2024).

Habib, K., Habib, S., Khan, S., Jafaripournimchahi, A. & Xing, X. A hybrid optimization approach for strategically placing electric vehicle charging stations in a radial distribution IEEE-33 bus system. Engineering Research Express 6(2), 025344 (2024).

Habib, K., Xu, X., Ling, H. & Khan, S. Optimum control and thermal management of varying operating conditions of variable frequency drives. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 252, 127496 (2025).

R. Liu and W. Shen, "Data Acquisition of Exercise and Fitness Pressure Measurement Based on Artificial Intelligence Technology," SLAS Technology, p. 100328, 2025.

Zhang, H. H. et al. Optimization of high-speed channel for signal integrity with deep genetic algorithm. IEEE Trans. Electromagn. Compat. 64(4), 1270–1274 (2022).

K. Feng, H. Hong, K. Tang, and J. Wang, "Statistical tests for replacing human decision makers with algorithms," Management Science, 2025.

Xue, J. & Shen, B. Dung beetle optimizer: A new meta-heuristic algorithm for global optimization. J. Supercomput. 79(7), 7305–7336 (2023).

Ye, M., Zhou, H., Yang, H., Hu, B. & Wang, X. Multi-strategy improved dung beetle optimization algorithm and its applications. Biomimetics 9(5), 291 (2024).

Shen, Q., Zhang, D., Xie, M. & He, Q. Multi-strategy enhanced dung beetle optimizer and its application in three-dimensional UAV path planning. Symmetry 15(7), 1432 (2023).

Zhu, F. et al. Dung beetle optimization algorithm based on quantum computing and multi-strategy fusion for solving engineering problems. Expert Syst. Appl. 236, 121219 (2024).

Hu, W., Zhang, Q. & Ye, S. An enhanced dung beetle optimizer with multiple strategies for robot path planning. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 4655 (2025).

Xia, H., Ke, Y., Liao, R. & Sun, Y. Fractional order calculus enhanced dung beetle optimizer for function global optimization and multilevel threshold medical image segmentation. J. Supercomput. 81(1), 90 (2025).

Abo-Khalil, A. G., Eltamaly, A. M., Alsaud, M. S., Sayed, K. & Alghamdi, A. S. Sensorless control for PMSM using model reference adaptive system. International Transactions on Electrical Energy Systems 31(2), e12733 (2021).

Kahraman, H. T., Aras, S. & Gedikli, E. Fitness-distance balance (FDB): A new selection method for meta-heuristic search algorithms. Knowl.-Based Syst. 190, 105169 (2020).

Aras, S., Gedikli, E. & Kahraman, H. T. A novel stochastic fractal search algorithm with fitness-distance balance for global numerical optimization. Swarm Evol. Comput. 61, 100821 (2021).

Guvenc, U., Duman, S., Kahraman, H. T., Aras, S. & Katı, M. Fitness–Distance Balance based adaptive guided differential evolution algorithm for security-constrained optimal power flow problem incorporating renewable energy sources. Appl. Soft Comput. 108, 107421 (2021).

Bakır, H. Dynamic fitness-distance balance-based artificial rabbits optimization algorithm to solve optimal power flow problem. Expert Syst. Appl. 240, 122460 (2024).

Zheng, K. et al. Hybrid particle swarm optimizer with fitness-distance balance and individual self-exploitation strategies for numerical optimization problems. Inf. Sci. 608, 424–452 (2022).

Tang, Z. et al. Chaotic wind driven optimization with fitness distance balance strategy. International Journal of Computational Intelligence Systems 15(1), 46 (2022).

Ebeed, M. et al. A modified artificial hummingbird algorithm for solving optimal power flow problem in power systems. Energy Rep. 11, 982–1005 (2024).

Ebeed, M. et al. Solving stochastic optimal reactive power dispatch using an Adaptive Beluga Whale optimization considering uncertainties of renewable energy resources and the load growth. Ain Shams Engineering Journal 15(7), 102762 (2024).

Ahmed, D. et al. An enhanced jellyfish search optimizer for stochastic energy management of multi-microgrids with wind turbines, biomass and PV generation systems considering uncertainty. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 15558 (2024).

Kapitaniak, T. Continuous control and synchronization in chaotic systems. Chaos, Solitons Fractals 6, 237–244 (1995).

Noman, A. M. et al. Optimum Fractional Tilt Based Cascaded Frequency Stabilization with MLC Algorithm for Multi-Microgrid Assimilating Electric Vehicles. Fractal and Fractional 8(3), 132 (2024).

Bastawy, M. et al. Optimal day-ahead scheduling in micro-grid with renewable based DGs and smart charging station of EVs using an enhanced manta-ray foraging optimisation. IET Renew. Power Gener. 16(11), 2413–2428 (2022).

Yao, X., Liu, Y. & Lin, G. Evolutionary programming made faster. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 3(2), 82–102 (1999).

Ebeed, M. et al. Optimal energy planning of multi-microgrids at stochastic nature of load demand and renewable energy resources using a modified Capuchin Search Algorithm. Neural Comput. Appl. 35(24), 17645–17670 (2023).

Ahmadi, B., Giraldo, J. S. & Hoogsteen, G. Dynamic hunting leadership optimization: algorithm and applications. Journal of Computational Science 69, 102010 (2023).

J. Brest, M. S. Maučec, and B. Bošković, "The 100-digit challenge: Algorithm jde100," in 2019 IEEE congress on evolutionary computation (CEC), 2019, pp. 19–26: IEEE.

Mirjalili, S. & Lewis, A. The whale optimization algorithm. Adv. Eng. Softw. 95, 51–67 (2016).

Seyyedabbasi, A. & Kiani, F. Sand Cat swarm optimization: A nature-inspired algorithm to solve global optimization problems. Engineering with Computers 39(4), 2627–2651 (2023).

Trojovská, E., Dehghani, M. & Trojovský, P. Zebra optimization algorithm: A new bio-inspired optimization algorithm for solving optimization algorithm. Ieee Access 10, 49445–49473 (2022).

Abdollahzadeh, B., Gharehchopogh, F. S. & Mirjalili, S. African vultures optimization algorithm: A new nature-inspired metaheuristic algorithm for global optimization problems. Comput. Ind. Eng. 158, 107408 (2021).

Mirjalili, S., Mirjalili, S. M. & Lewis, A. Grey wolf optimizer. Adv. Eng. Softw. 69, 46–61 (2014).

Heidari, A. A. et al. Harris hawks optimization: Algorithm and applications. Futur. Gener. Comput. Syst. 97, 849–872 (2019).

Houssein, E. H., Oliva, D., Samee, N. A., Mahmoud, N. F. & Emam, M. M. Liver cancer algorithm: A novel bio-inspired optimizer. Comput. Biol. Med. 165, 107389 (2023).

M. Ebeed et al., "An enhanced weighted mean of vectors optimizer: addressing combined heat and power economic dispatch with system losses and valve point loading effect," Neural Computing and Applications, pp. 1–33, 2025.

M. Sudhakaran and S. M. R. Slochanal, "Integrating genetic algorithms and tabu search for combined heat and power economic dispatch," in TENCON 2003. Conference on Convergent Technologies for Asia-Pacific Region, 2003, vol. 1, pp. 67–71: IEEE.

Song, Y. & Xuan, Q. Combined heat and power economic dispatch using genetic algorithm based penalty function method. Electric machines and power systems 26(4), 363–372 (1998).

Song, Y., Chou, C. & Stonham, T. Combined heat and power economic dispatch by improved ant colony search algorithm. Electric Power Systems Research 52(2), 115–121 (1999).

Shi, B., Yan, L.-X. & Wu, W. Multi-objective optimization for combined heat and power economic dispatch with power transmission loss and emission reduction. Energy 56, 135–143 (2013).

Shaheen, A. M., Ginidi, A. R., El-Sehiemy, R. A. & Ghoneim, S. S. Economic power and heat dispatch in cogeneration energy systems using manta ray foraging optimizer. IEEE Access 8, 208281–208295 (2020).

Duman, S. et al. Improvement of the Fitness-Distance Balance-Based Supply-Demand Optimization Algorithm for Solving the Combined Heat and Power Economic Dispatch Problem. Iranian Journal of Science and Technology, Transactions of Electrical Engineering 47(2), 513–548 (2023).

Basu, M. Bee colony optimization for combined heat and power economic dispatch. Expert Syst. Appl. 38(11), 13527–13531 (2011).

Basu, M. Artificial immune system for combined heat and power economic dispatch. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 43(1), 1–5 (2012).

Basu, M. Combined heat and power economic dispatch by using differential evolution. Electric Power Components and Systems 38(8), 996–1004 (2010).

Ghasemi, M. et al. A novel and effective optimization algorithm for global optimization and its engineering applications: Turbulent Flow of Water-based Optimization (TFWO). Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 92, 103666 (2020).

Liu, D., Hu, Z., Su, Q. & Liu, M. A niching differential evolution algorithm for the large-scale combined heat and power economic dispatch problem. Appl. Soft Comput. 113, 108017 (2021).

Pattanaik, J. K., Basu, M. & Dash, D. P. Heat transfer search algorithm for combined heat and power economic dispatch. Iranian Journal of Science and Technology, Transactions of Electrical Engineering 44, 963–978 (2020).

Basu, M. Group search optimization for combined heat and power economic dispatch. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 78, 138–147 (2016).

Mellal, M. A. & Williams, E. J. Cuckoo optimization algorithm with penalty function for combined heat and power economic dispatch problem. Energy 93, 1711–1718 (2015).

Subbaraj, P., Rengaraj, R. & Salivahanan, S. Enhancement of combined heat and power economic dispatch using self adaptive real-coded genetic algorithm. Appl. Energy 86(6), 915–921 (2009).

Khorram, E. & Jaberipour, M. Harmony search algorithm for solving combined heat and power economic dispatch problems. Energy Convers. Manage. 52(2), 1550–1554 (2011).

Li, Z., Zou, D. & Kong, Z. A harmony search variant and a useful constraint handling method for the dynamic economic emission dispatch problems considering transmission loss. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 84, 18–40 (2019).

Hosseini-Hemati, S., Beigvand, S. D., Abdi, H. & Rastgou, A. Society-based Grey Wolf Optimizer for large scale Combined Heat and Power Economic Dispatch problem considering power losses. Appl. Soft Comput. 117, 108351 (2022).

Yang, Q., Liu, P., Zhang, J. & Dong, N. Combined heat and power economic dispatch using an adaptive cuckoo search with differential evolution mutation. Appl. Energy 307, 118057 (2022).

Shaheen, A. M., Elsayed, A. M., Elattar, E. E., El-Sehiemy, R. A. & Ginidi, A. R. An Intelligent Heap-Based Technique With Enhanced Discriminatory Attribute for Large-Scale Combined Heat and Power Economic Dispatch. IEEE Access 10, 64325–64338 (2022).

Spea, S. Social network search algorithm for combined heat and power economic dispatch. Electric Power Systems Research 221, 109400 (2023).

Basu, M. Combined heat and power economic dispatch using opposition-based group search optimization. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 73, 819–829 (2015).

Hagh, M. T., Teimourzadeh, S., Alipour, M. & Aliasghary, P. Improved group search optimization method for solving CHPED in large scale power systems. Energy Convers. Manage. 80, 446–456 (2014).

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB). The authors did not receive financial support for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests or other interests that might be perceived to influence the results and/or discussion reported in this paper.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rihan, M., Ebeed, M., Khan, N.H. et al. A modified Dung Beetle optimizer for combined heat and power economic dispatch considering power losses, valve-point effects, and operating constraints. Sci Rep 16, 2278 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32060-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32060-4