Abstract

Selenium (Se), an essential trace element for human health, is acquired primarily through the consumption of Se-enriched foods. Lily (Lilium lancifolium Thunb.) is a traditional Chinese medicinal plant that efficiently assimilates selenite through foliar uptake. This investigation elucidates the phytophysiological responses and molecular regulatory networks underlying selenite metabolism in lilies through comprehensive transcriptomic characterization. The experimental treatments consisted of graded selenite concentrations (0–8.0 mmol/L), revealing 2.0 mmol/L as the optimal concentration for enhancing biomass production and osmoprotectant accumulation. High-throughput RNA sequencing generated 59.38 Gb of clean data, yielding 76,814 functionally annotated unigenes. GO analysis revealed that the unigenes were involved mainly in cell, binding and cellular processes. Through KEGG pathway enrichment analysis, differentially expressed genes were shown to be involved mainly in translation and carbohydrate metabolism predominant pathways. Validation through RT-qPCR confirmed that pivotal enzymatic regulators including sulfite reductase, serine acetyltransferase, sterol methyltransferase, cystathionine beta-lyase, mitochondrial translation, and methionone s-methyltransferase, are important enzyme-encoding genes involved in the metabolic pathway of selenite in lily. Moderate Se exposure upregulated the expression of carbohydrate metabolism pathway genes, including SUS, SPS, and Inv genes, which was correlated with increased growth parameters. In contrast, supraoptimal concentrations induced a reactive oxygen species burst. Moreover, the expression levels of antioxidant genes such as superoxide dismutase, catalase, ascorbate peroxidase, glutathione peroxidase, and glutathione reductase decreased, ultimately leading to Se toxicity in lily plants. These results delineate the regulatory network of Se accumulation and biosynthesis in lily, which helps to elucidate the physiological and molecular mechanisms of lily growth under Se accumulation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As an essential component of 25 functional proteins, selenium (Se) is an important microelement for human and animal survival1,2. The antioxidant capacity of glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px) with Se is 200-fold greater than that with vitamin E3. Se protects the human immune system and plays an important role in resistance to cancer, cardiovascular disease, diabetes and other diseases4. However, Se deficiency can lead to Keshan disease5,6. In recent years, the problem caused by Se deficiency has become increasingly severe worldwide7,8. Previous studies have shown that Chinese residents generally lack Se, with an average daily Se intake of only 43.3 μg, which is far below the World Health Organization’s recommended value of 60 μg/d9. Owing to the inability of the human body to synthesize Se on its own, Se can only be obtained from the external environment10. At present, there are many Se-enriched health care products on the market, but these products are not accepted by the general public due to their high prices. Improving the Se content in agricultural products through agronomic methods is easy to implement and has the advantages of low cost and good effectiveness11,12. Therefore, we aimed to find an agricultural product with increased Se absorption efficiency to supplement Se in the human body.

The absorption, assimilation, and metabolic pathways of Se in nature are very complex. Plants absorb and assimilate exogenous Se through their roots or leaves, converting inorganic Se into more effective and stable organic Se within the plant body13. Inorganic Se is mainly absorbed by plants in the form of selenate (SeO42-) and selenite (SeO32)14. The main forms of organic Se are selenocystine (SeCys2), selenocysteine (SeCys), selenomethionine (SeMet), etc. Compared with inorganic Se, organic Se is safer, more effective, and easier absorb and utilize by the human body15. Owing to the greater bioavailability of Se in plants than in animals, plant Se to some extent determines the Se level in the food chain16. Selenate is more soluble in water and is the most common biologically available Se in soil environments. Plants absorb selenate faster than they absorb selenite, but the conversion efficiency of selenite in plants is greater than that of selenate. In general, selenate is first converted into selenite and then further absorbed and utilized by plants. However, 90% of selenite can be directly converted into organic Se17. Research has shown that the Se enrichment effect of foliar application is 8 times greater than that of soil Se application18. In the late stage of plant growth, the absorption and assimilation of Se by leaves occur faster than those by roots. As the root-to-shoot ratio increases, the soil adsorbs and fixes more Se19. Therefore, we explored the absorption efficiency of Se in plants by foliar spraying of selenite.

China has extremely rich lily germplasm resources, accounting for more than half of the total number of lilies in the world20. Lily is a perennial herbaceous plant composed of aerial parts and underground parts. Lily has medicinal and edible value, and the underground bulbs are used as medicinal and edible parts of lily20. The accumulation of carbohydrates is the most important factor affecting growth of lily bulbs21,22. Se combines with lily polysaccharides to form Se polysaccharides, which not only exhibit pharmacological activities themselves, such as antitumor, antioxidant, immune regulatory, and antifatigue activities, but also regulate the immune and antioxidant activities of Se23,24. Moreover, Se polysaccharides reduce the toxicity of inorganic Se, which improves Se absorption and utilization in the body25,26.

At present, there are few reports on the molecular mechanisms by which Se affects the vegetative growth of plants27,28. The lack of understanding of the physiological functions and mechanisms of Se in plants hinders the utilization of Se-enriched plant resources and the development process of Se-enriched agricultural products. Here, we used six concentrations of selenite to treat lily and compared the growth and nutrient accumulation of lily under the different concentrations of selenite. This study used RNA-seq technology to perform transcriptome analysis of selenite-treated lily. Therefore, this study explored the physiological and molecular mechanisms underlying the effects of selenite on the vegetative growth of lily through comprehensive analysis of physiological indicators and transcriptomics, providing a theoretical basis and technical support for the breeding of Se-rich lily.

Materials and methods

Plant materials and treatments

Lily seedlings were provided by the Institute of Chinese Herbal Medicine, Hubei Academy of Agricultural Science, Enshi city, Hubei Province. The experiment was conducted at an altitude of 1507 m (30°11′12″ N, 109°46′32″ E) at an experimental base. Uniform two-year-old lily seedlings were selected for this experiment. Foliar applications consisted of aqueous sodium selenite solutions (0, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 4.0, and 8.0 mmol/L) administered as 250 mL sprays biweekly for eight weeks. Mature leaves (positions 10–20 from the apex) were harvested for transcriptome analysis and various physiological measurements, with triplicate samples rapidly frozen in liquid nitrogen.

Chlorophyll content detection

Leaf chlorophyll was quantified through 12-h ethanol (95%) extraction of 0.1 g of tissue28. A spectrophotometer was used to colorimetrically calculate the absorbance at 649 nm and 665 nm when the leaves turned white. Chlorophyll content (mg/g FW) = (20.8 × A645 + 8.04 × A663) × V/M. (A: absorbance; V: volume of alcohol; M: weight of leaves)29.

Soluble protein detection

Lily leaves (0.3 g) were ground in phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH 7.8), which contained 0.7% NaH2PO4·2H2O and 1.64% Na2HPO4·12H2O at pH 7.8. The supernatant was collected after centrifugation at 5000 × g at 4 °C for 20 min, and analyzed via a Coomassie brilliant blue G-250 assay.Measure the absorbance at 595 nm wavelength28.Aliquots of 10 μL, 20 μL, 40 μL, 60 μL, 80 μL, and 100 μL of the 1 mg/mL γ-globulin solution were separately diluted to a final volume of 100 μL with ddH2O to prepare the standard curve. ddH2O was used as the reagent blank. In the standard assay, the A595 for 100 μg of γ-globulin is approximately 0.4. Based on the absorbance of the test samples, the protein concentration was calculated from the standard curve.

Soluble sugar detection

Lily leaves (0.3 g) were boiled in 10 mL of 80% ethanol solution for 30 min, and the soluble sugar content was measured using anthrone reagent. 0.5 mL sample and 2 mL anthrone reagent mixed at 4 °C, cooled in a boiling water for 10 min. Measure the absorbance at 620 nm and calculate the content according to the standard curve28.

Measurements of SOD, POD, CAT, and H2O2

Superoxide dismutase (SOD), peroxidase (POD), and catalase (CAT)activities were measured using spectrophotometry kits (Suzhou Ke Ming Biotechnology Co., Ltd.; the catalog numbers are SOD-2-W, POD-2-Y, and CAT-2-W respectively) following the manufacturer’s instructions and using a UV–vis spectrophotometer. The SOD assay reaction mixture (50 mM PBS, 13 mM methionine, 75 μM NBT, 2 μM riboflavin, 0.1 mM EDTA, and an appropriate enzyme solution) was incubated under natural light at 25 ℃ for 15 min, with the control kept in the dark. Measure the absorbance at 560 nm and determine the enzyme amount that inhibits NBT reduction by 50% as one activity unit (U). POD assay reaction system (50 mM PBS,0.2% H2O2, 0.1% guaiacol, 0.1 mL enzyme solution). Measure the absorbance change within 1 min at 470 nm. CAT assay reaction system (50 mM PBS, 15 mM H2O2, 0.1 mL enzyme solution). Measure the absorbance change within 1 min at 240 nm. SOD, POD, and CAT activities are expressed as U/min/g FW on a fresh weight basis. The H2O2 content was quantified with corresponding test kits (Keming, Suzhou, China; the catalog number is H2O2-2-Y) using spectrophotometry. Extract the tissue with acetone and centrifuge to obtain the supernatant. The reaction system consists of 1 mL of supernatant, 0.1 mL of 20% Ti (SO4) 2, and 0.2 mL of NH4OH. After centrifugation, the precipitate is dissolved in 2 M H4SO4. Measure the absorbance at 405 nm and calculate the content using the standard curve method30,31.

Transcriptomic sequencing and analysis

Total RNA was isolated from lily leaves treated with 0, 2.0, or 4.0 mmol/L selenite using TRIzol® reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Libraries were prepared with a NEBNext® Ultra™ Illumina® RNA Library Preparation Kit (NEB, Ipswich, MA, USA). A NovaSeq 6000 sequencer was used to sequence paired-end RNA-seq libraries. The assembled transcripts were searched against the NCBI protein nonredundant (NR), Clusters of Orthologous Groups of proteins (COG), Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) and Gene Ontology (GO) databases. DESeq2 was used to identify DEGs (|log₂FC|≥ 1, FDR ≤ 0.05), with functional enrichment analyzed via clusterProfiler32,33,34,35,36.

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA extracted with RNAplant plus Reagent (Tiangen, China) was reverse transcribed using the iCycler iQ5 detection system (Bio-Rad, USA) used to conduct RT-qPCR using the SYBR Green method37. All primers used in this study are presented in Supplemental Table 1.

Data presentation and statistical analysis

Triplicate biological replicates were analyzed in DPS (Digital Processing Systems, Hicksville, NY, USA)38. We considered a P value < 0.05 as significant and a P value < 0.01 as very significant.

Results

Effects of selenate on lily growth

To investigate the effects of selenite on the growth and development of lilies, lily seedlings were treated with 0, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 4.0, or 8.0 mmol/L selenite. As shown in Fig. 1A, the optimal concentration for promoting lily growth was 2.0 mmol/L selenite. Compared with those of the control group, the biomass, height, number of bulbils, and chlorophyll content of the lilies significantly increased. The biomass of lily seedlings gradually increased under the 0.5 mmol/L and 1.0 mmol/L selenite treatments. The 4.0 mmol/L and 8.0 mmol/L selenite treatments obviously inhibited the growth of lily, and the plants presented symptoms of wilting, leaf chlorosis, and senescence (Fig. 1 A–E). The above results showed that a low concentration (0–2.0 mmol/L) of selenite promoted the vegetative growth of lily, but concentrations above 2.0 mmol/L inhibited growth and even caused poisoning symptoms in the plants. The optimal concentration for promoting the nutritional growth of lily is 2.0 mmol/L selenite.

Effects of selenite on osmotic regulation in lily leaves

To investigate the effects of selenite on osmotic substances in lily leaves, we measured the soluble sugar and soluble protein contents. The results revealed that the soluble sugar and soluble protein contents in the 0–2.0 mmol/L selenite treatment groups were significantly greater than those in the control group (Fig. 2). In particular, in the 2.0 mmol/L selenite treatment group, the soluble sugar and soluble protein contents reached their peak values, which were, increasing by 1.52, 1.43, and 1.15 times greater than those in the control group, respectively (Fig. 2). Under the treatments of 4.0 and 8.0 mmol/L selenite, the soluble sugar and soluble protein contents significantly decreased. In addition, the ratio of soluble sugar and soluble protein content in the aboveground to underground parts also peaked in the 2.0 mmol/L selenite treatment group. In general, the treatment with 2.0 mmol/L selenite significantly improved the accumulation of nutrients in lily leaves (Fig. S1).

Effects of selenite on oxidative damage in lily leaves

When cellular metabolic activity is increased, SOD, POD, and CAT activities increase, whereas the H2O2 content decreases. Therefore, we used SOD, POD, CAT, and H2O2 as indicators to measure the oxidative damage to lily leaves under selenite treatment. Compared with the control group, the 0–2.0 mmol/L selenite treatments significantly increased the activities of SOD, POD, and CAT in lily leaves, whereas the H2O2 content exhibited the opposite trend (Fig. 3A–D). Under the 4.0 and 8.0 mmol/L selenite treatments, the activities of SOD and POD were significantly lower than those in control, while the H2O2 content was significantly greater than that in the control (Fig. 3A–D). These results showed that at concentrations exceeding 2.0 mmol/L of selenite, the higher the concentration was, the greater the degree of oxidative damage to lily leaves indicating dose-dependent oxidative damage. The above results indicated that 2.0 mmol/L selenite not only promoted the vegetative growth of lily but also did not cause oxidative damage to lily leaves. The cultivation and consumption of lily grown in a 2.0 mmol/L selenite solution was explored as a strategy for health improvement.

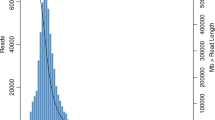

Transcriptome sequencing and annotation

To further reveal the physiological and molecular mechanisms of the lily response to selenite, samples from the 0, 2.0, and 4.0 mmol/L selenite treatment groups were selected as materials for transcriptome analysis. A total of 59.38 Gb of clean data were generated, with the Q30 content exceeding 91.06% and the GC content exceeding 47.59% in each library, indicating that the transcriptomic data were of high quality and could be used for further DEG analysis. A total of 76,814 unigenes were obtained, with an average length of 786.11 bp and an N50 of 1231 bp. A total of 76,814 unigenes were annotated from the six databases, including 37,271 from NR, 30,916 from GO, 17,790 from KEGG, 28,698 from Swiss-Prot, 34,373 from eggNOG, and 26,947 from Pfam (Fig. 4A). In total, 62/238 genes were upregulated/downregulated under the 2.0 mmol/L selenite treatment, and 436/656 DEGs were upregulated/downregulated under the 4.0 mmol/L selenite treatment (Fig. 4B, C).

GO enrichment analysis of differentially expressed genes

On the basis of the GO terms, a total of 30,788 unigenes could be classified into 3 gene ontology (GO) terms, including biological process, molecular function and cellular component. There were 9 biological process, 5 molecular function and 6 cellular process subcategories. In the biological process category, the most abundant terms were “cellular process,” “metabolic process,” and “biological regulation”. In the molecular function category, “binding,” “catalytic activity,” and “transporter activity” were the most highly represented terms. Among the cellular component process category, the most abundant terms were “cell part”, “membrane part”, and “organelle” (Fig. 4D).

KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of DEGs

Enrichment analysis was conducted on the KEGG pathways in five categories: metabolism, genetic information processing, environmental information processing, cellular processes, and organic systems39,40. The results revealed that all the DEGs were successfully assigned to 19 KEGG pathways. KEGG pathway enrichment analysis revealed that the DEGs were significantly enriched in translation; carbohydrate metabolism; folding, sorting and degradation; amino acid metabolism; and energy metabolism (Fig. 4E). The expression analysis of key genes involved in the selenite absorption pathway in lily is worth exploring. By integrating GO and KEGG enrichment analysis, we focused on the carbohydrate metabolism process in cells. The most differentially expressed genes are involved in the metabolic process, carbohydrate, and carbohydrate metabolism pathways. Key metabolic genes in the sucrose and starch metabolic pathways may also have been enriched.

RT-qPCR analysis

To verify the accuracy of the RNA-seq data, we selected 6 highly expressed genes for RT-qPCR analysis, namely, POL, OPN4, RPS, EF1G, FAR, and TAKT. The GAPL gene was used as an internal reference gene (Fig. 5). The results revealed that the expression levels of these genes were highly consistent with the RNA-seq results, indicating that the RNA-seq results are reliable (Fig. S2).

RNA-seq and RT-qPCR analysis of 6 significantly expressed genes, namely, (A) POL, (B) OPN4, (C) RPS, (D) EF1G, (E) FAR, and (F) TAKT. GAPL was used as internal control for qRT-PCR. Three technical replicates were performed. Error bars represent standard deviations and letters significant values at P < 0.05.

The absorption and metabolic pathways of selenite in lily leaves

At present, the mechanism by which selenite is absorbed by plants is not clear. Studies have shown that plants actively absorb selenite through phosphorus transport proteins41,42. The metabolism of selenite in plants is relatively clear. Selenite is converted into organic Se, including SeCys and SeMet, which plants can absorb, including SeCys and SeMet. In order to verify the selenite metabolism pathway in lily leaves, the expression levels of important enzyme-encoding genes which including sulfite reductase (SiR), serine acetyltransferase (SAT), sterol methyltransferase (SMT), cystathionine beta-lyase (CBL), mitochondrial translation (MTR), and methionone s-methyltransferase (MMT) in the pathway were detected in lily leaves sprayed with 2 mmol/L and 4 mmol/L selenite. When lily leaves were treated with 2 mmol/L selenite, the expression levels of the six genes mentioned above significantly increased, indicating that these six genes are involved in the selenite metabolism pathway of lilies (Fig. 6). Interestingly, the expression levels of the SiR and SAT genes were high when SeO32- was converted to SeCys, whereas the expression levels of the CBL and MTR genes were relatively low when SeO32- was converted to SeMet. This result suggests that the process by which lily leaves absorb selenite may involve the plastid, which metabolizes SeO32- through the conversion of γ-glutamylcysteine (γ-GMSeCys) and dimethyl diselenide (DMDSe). Moreover, the expression levels of six genes were generally reduced when lily leaves were treated with 4 mmol/L selenite, indicating that these six genes involved in the metabolism of SeO32- were damaged by high concentrations of selenite (Fig. 6).

The physiological response of lily to selenite and the potential metabolic pathways of selenite

According to the results of the GO enrichment analysis and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis, the most differentially expressed genes are involved in the metabolic process, carbohydrate, and carbohydrate metabolism pathways. We identified the three most important genes in the sucrose and starch metabolism pathways, namely, SUS, SPS, and Inv.

The results revealed that when lily leaves were treated with 2 mmol/L selenite, the expression levels of these three genes were significantly increased, indicating that the conversion of low concentrations of Se into carbon sources promoted the growth and development of lilies (Fig. 7).

As shown in Figs. 1, 3, and 6, when lily leaves were treated with 4 mmol/L selenite, their growth and development were impaired, their Se antioxidant capacity was weakened, and a large amount of reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulated. The ability of genes encoding enzymes involved in the selenite metabolism pathway to metabolize SeO32- was also impaired. Previous studies have shown that moderate Se can increase GSH-Px activity; eliminate excess free radicals; participate in energy metabolism; and promote plant root growth, development, and vitality43. High concentrations of Se cause the accumulation of large amounts of ROS in crops, leading to oxidative stress and subsequent toxicity44,45. Therefore, we measured the expression of the major antioxidant system member genes in organisms, including SOD, CAT, ascorbate peroxidase (APX), glutathione peroxidase (GPX), and glutathione reductase (GR). Low concentrations of selenite promoted the expression of these five genes, whereas high concentrations of selenite reduced their expression levels (Fig. 7). These results indicate that low concentrations of Se prevent plant peroxidation by scavenging excess free radicals, whereas high concentrations of Se increase the production of free radicals and promote peroxidation.

Discussion

An appropriate concentration of Se promotes the growth of lily

Treating lily leaves with 2 mmol/L selenite resulted in increased growth, development, and nutrient accumulation (Figs. 1, 2 and 7). The research results of the past year have found that Se stimulated the growth of L. lancifolium at low level (2.0 mmol/L) but showed an inhibitory effect at high levels (≥ 4.0 mmol/L) which is consistent with our research findings31. In Jiang’s study, the significantly upregulated SUS, bgl B, BAM, and SGA1 genes were involved in soluble sugar accumulation under Se treatment. In our study, the three most important genes in the sucrose and starch metabolism pathways are SUS, SPS, and Inv. Previous studies have shown that treating rice with 0.5–5 mg/kg selenite increases rice yield, proving that the experimental results in the present study have a scientific basis46. Moderate Se treatment also promoted photosynthesis and the synthesis of amino acids and proteins in rice47,48,49. Low-concentration selenite treatment (2.2–4.4 mg/kg) promoted tobacco growth and significantly increased plant height and dry matter weight50. A 9 μM selenate treatment significantly increased the dry weights of potato roots and aboveground parts51. The application of 0.5–1.0 mg/kg SeCys to soil significantly increased the dry weight of Chinese cabbage roots and leaves52. Se concentrations of 10 mg/L and 20 mg/L Nanometre also affect the dry weights of strawberry roots and aboveground parts53. Numerous studies have shown that different forms and concentrations of Se affect the growth and development of plants, although Se is not an essential nutrient for plants.

High concentrations of Se cause toxicity to lily

Se is an important element involved in the oxidative activity of glutathione peroxidase and in plant antioxidant defense processes54. A study revealed that a moderate concentration of Se stimulated the growth and antioxidant capacity of Salvia miltiorrhiza55. The toxicity caused by high concentrations of Se in crops is due to the production of toxic peroxides as oxidants56. When high concentrations of Se cause oxidative stress, a large amount of ROS accumulate in the crops44,45. SOD, POD, and CAT enzymes protect cell membranes from oxidation and damage by removing peroxides and free radicals, thereby maintaining the integrity of the cell membrane structure and function. Research has shown that high concentrations of selenate increase the activities of SOD, POD, and CAT in rice, disrupting photosynthesis in rice leaves57. In this study, the activities of SOD, POD, and CAT increased but then decreased with increasing selenite concentration. However, the content of H2O2 was exactly opposite to the above results (Fig. 3). As a result, the photosynthetic system is disrupted, and the content of photosynthetic pigments decreases accordingly58. The antioxidant capacity of Brassica napus significantly increased when Se was added externally59. Similar studies have shown that Se promotes the expression of genes encoding antioxidant enzymes (AOEs), such as SOD, POD, CAT, GR, and GST-1, in B. napus while reducing the toxicity of Cr60. The application of 0.5–1.0 mg/kg SeCys to soil significantly increased the activities of AOEs (POD, SOD, CAT, APX, and GR) in the roots and leaves of61. The expression levels of the SOD, CAT, APX, GPX, and GR genes in lily leaves were significantly downregulated under the 4 mmol/L selenite treatment (Fig. 7). Previous studies have shown that high concentrations of Se damage the electron transfer rate and mitochondrial respiration rate of plant leaf chloroplasts, causing damage to the chloroplast membrane and ultimately leading to a decrease in the chlorophyll content in the leaves62. In our study, high concentrations of Se reduced the chlorophyll content in lily leaves (Fig. 1E).

Absorption and metabolism of selenite in lily leaves

Early studies implied that Se, mainly as selenate and selenite, is transported in plants via sulfur (S) and phosphate (P) transporters, respectively. Selenate is generally absorbed through sulfate transporters in plants63. In Se-tolerant Arabidopsis, Sultr1, Sultr2, Sultr3, and Sultr4 encode sulfate transporters64. In our study, the RNA-seq results revealed that 6 genes are involved in the metabolic pathway of selenite in lily leaves. Compared with the gene encoding sulfate transporters, the gene encoding phosphate transporters is expressed at a greater level during the absorption and transport of selenite30,65. When lily leaves were treated with 2 mmol/L selenite, the expression of the SiR, SAT, SMT, CBL, MTR, and MMT genes was upregulated. Sulfite reductase expressed in Arabidopsis plastids is responsible for the reduction of selenite66,67. The expression level of the SAT gene increased significantly, which converts Se2- into SeCys. However, the expression levels of MTR and MMT were lower than those of SAT and SMT. Selenite is converted to SeCys in plastids, then to SeMet in the cytosol, and finally is absorbed by plants in the form of organic selenium68,69. We speculate that γ-glutamylcysteine (γ-GMSeCys) and dimethyl diselenide (DMDSe) absorb and metabolize SeO32- and that this process also occurs in plastids. Our results provide valuable information on the molecular regulation of selenite in lily.

Conclusion

This study investigated the effects of different concentrations of selenite on the vegetative growth of lily. The results revealed that the 2.0 mmol/L Se treatment significantly promoted the vegetative growth of lily, whereas the 4.0 and 8.0 mmol/L Se treatments had the opposite effect. Transcriptome analysis revealed that SiR, SAT, SMT, CBL, MTR, and MMT are important enzyme-encoding genes involved in the metabolic pathway of selenite in lily. Moreover, moderate Se treatment promoted the expression of SUS, SPS, and Inv genes involved in carbohydrate metabolism, thereby promoting the growth and development of lily. High-Se treatment generates a large amount of ROS and inhibits the expression of antioxidant genes such as SOD, CAT, APX, GPX, and GR, resulting in oxidative stress in lily. These results elucidate the genes involved in the pathways regulating Se absorption and metabolism in lily leaves, which furthers elucidates the physiological and molecular mechanisms by which Se affects lily growth and development, laying a theoretical foundation for knowing to cultivate lily with Se supplementation.

Data availability

The data presented in the study are deposited in the NGDC Genome Sequence Archive (GSA) database, https://nbdc.cncb.ac.cn/, accession number CRA017526.

References

Benstoem, C. et al. Selenium and Its supplementation in cardiovascular disease: What do we know?. Nutrients 7, 3094–3118 (2015).

Wang, G. et al. Effects of springtime sodium selenate foliar application and NPKS fertilization onselenium concentrations and selenium species in forages across Oregon. Anim. FeedSci. Technol. 276, 114944 (2021).

Taneja, S. S. Re: Difference in association of obesity with prostate cancer risk between US African American and non-hispanic white men in the selenium and vitamin E cancer prevention trial (SELECT). J Urol. 195, 627–628 (2016).

Cai, X. L. et al. Selenium exposure and cancer risk: An updated meta-analysis and meta-regression. Sci Rep 6, 1–18 (2016).

D’Amato, R. et al. Selenium biofortification in rice (Oryza sativa L.) sprouting: Effects on Se yield and nutritional traits with a focus on phenolic acid profile. J Agr Food Chem. 66, 4082–4090 (2018).

Pyrzynska, K. & Sentkowska, A. Selenium in plant foods: Speciation analysis, bioavailability, and factors afecting composition. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 61, 1340–1352 (2021).

Gao, M. et al. Foliar spraying with silicon and selenium reduces cadmium uptake and mitigates cadmium toxicity in rice. Sci Total Environ. 632, 1100–1108 (2018).

Kumar, J., Gupta, D., Kumar, S., Gupta, S. & Singh, N. P. Current knowledge on genetic biofortification in lentil. J Agr Food Chem. 64, 6383–6396 (2016).

Duan, L. L. The physiological functions of selenium and the development of selenium rich health foods. Modern Food. 1, 42–45 (2018).

Peters, K. M., Galinn, S. E. & Tsuji, P. A. Selenium: Dietary sources, human nutritional requirements and intake across populations. Springer. 25, 319–412 (2016).

D’Amato, R., De-Feudis, M., Guiducci, M., Businelli, D. & Zeamays, L. Grain: Increase in nutraceutical and antioxidant properties due to se fortification in low and high water regimes. J Agric Food Chem. 67, 7050–7059 (2019).

José, C. et al. Selenium agronomic biofortification in rice: Improving crop quality against malnutrition. Plant Soil. 2, 323–375 (2020).

Marschall, T. A., Bornhorst, J., Kuehnelt, D. & Schwerdtle, T. Differing cytotoxicity and bioavailability of selenite, methylselenocysteine, selenomethionine, selenosugar 1 and trimethylselenonium ion and their underlying metabolic transformations in human cells. Mol Nutr Food Res. 60, 2622–2632 (2016).

Bitterli, C., Bauelos, G. S. & Schulin, R. Use of transfer factors to characterize uptake of selenium by plants. J Geochem Explor. 107, 206–216 (2010).

Rayman, M. P. Food-chain selenium and human health: Emphasis on intake. Br J Nutr. 100, 254–268 (2008).

Zhang, Y. et al. Modes of selenium occurrence and LCD modeling of selenite desorption/adsorption in soils around the selenium-rich core, Ziyang County. China. Environ Sci Pollut R. 25, 14521–14531 (2018).

Wang, Q. et al. Influence of long-term fertilization on selenium accumulation in soil and uptake by crops. Pedosphere 26, 120–129 (2014).

Ros, G. H., Rotterdam, A. M. D., Bussink, D. W. & Bindraban, P. S. Selenium fertilization strategies for bio-fortification of food: An agro-ecosystem approach. Plant Soil. 404, 99–112 (2016).

Ramkissoon, C. et al. Improving the efficacy of selenium fertilizers for wheat biofortification. Sci Rep. 9, 19520–19528 (2019).

Zhou, J., An, R. & Huang, X. Genus Lilium: A review on traditional uses, phytochemistry and pharmacology. J Ethnopharmacol. 270, 113852 (2021).

Yun, W. et al. Differential effects of paclobutrazol on the bulblet growth of oriental lily cultured in vitro: Growth behavior, carbohydrate metabolism, and antioxidant capacity. J Plant Growth Regul. 38, 359–372 (2018).

Zheng, R. R., Wu, Y. & Xia, Y. P. Chlorocholine chloride and paclobutrazol treatments promote carbohydrate accumulation in bulbs of Lilium Oriental hybrids “Sorbonne”. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 13, 136–144 (2012).

Cheng, L., Wang, Y., He, X. & Wei, X. Preparation, structural characterization and bioactivities of Se-containing polysaccharide: A review. Int J Biol Macromol. 120, 82–92 (2018).

Ding, G. B., Nie, R. H., Lv, L. H., Wei, G. Q. & Zhao, L. Q. Preparation and biological evaluation of a novel selenium-containing exopolysaccharide from Rhizobium sp. N613. Carbohydr Polym. 109, 28–34 (2014).

Cao, J., Liu, X., Cheng, Y., Wang, Y. & Wang, F. Selenium-enriched polysaccharide: An effective and safe selenium source of C57 mice to improve growth performance, regulate selenium deposition, and promote antioxidant capacity. Biol Trace Elem Res. 200, 2247–2258 (2022).

Souza, D. F. et al. Effect of selenium-enriched substrate on the chemical composition, mineral bioavailability, and yield of edible mushrooms. Biol Trace Elem Res. 201, 3077–3087 (2023).

Liu, C. et al. Metabolomicscombined with physiology and transcriptomics reveal key metabolic pathway responses in apple plants exposure to different selenium concentrations. J. Hazardous Mater. 464, 132953 (2024).

Jiang, X. G. et al. Combined transcriptome and metabolome analyses reveal the effects of selenium on the growth and quality of Lilium lancifolium. Front plant sci. 15, 1399152 (2024).

Yang, Y. Y. et al. MdSnRK1.1 interacts with MdGLK1 to regulate abscisic acid-mediated chlorophyll accumulation in apple. Horticul Res. 11, uhad288 (2024).

Romero-Puertas, M. C. Cadmium-induced subcellular accumulation of O2 and H2O2 in pea leaves. Plant Cell Environ. 27, 1122–1134 (2004).

Yang, Y. Y. et al. Apple MdSAT1 encodes a bHLHm1 transcription factor involved in salinity and drought responses. Planta 46, 253 (2021).

Yu, G., Wang, L. G., Han, Y. & He, Q. Y. clusterProfiler: An R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. OMICS 16, 284 (2012).

Dibrova, D. V., Konovalov, K. A., Perekhvatov, V. V., Skulachev, K. V. & Mulkidjanian, A. Y. COGcollator: A web server for analysis of distant relationships between homologous protein families. Biol direct 12(1), 29 (2017).

Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Tanabe, M., Sato, Y. & Morishima, K. KEGG: New perspectives on genomes, pathways, diseases and drugs. Nucleic Acids Res 45(D1), D353–D361 (2017).

Zhao, Y. et al. Protein function prediction with functional and topological knowledge of gene ontology. IEEE Trans Nanobiosci 22(4), 755–762 (2023).

Liu, S. et al. Three differential expression analysis methods for RNA sequencing: Limma, EdgeR, DESeq2. J Visual Exp: JoVE https://doi.org/10.3791/62528 (2021).

Kim, J. H., Lee, S. & Park, E. R. Real-time PCR-based detection of hepatitis E virus in groundwater: Primer performance and method validation. Int J Mol Sci. 26, 7377 (2025).

Yang, Y. Y. et al. Coordinated transcriptomic and metabolomic analyses reveal mechanisms involved in smut disease resistance in Rheum officinale Baill. Gene 964, 149642 (2025).

Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 27–30 (2000).

Kanehisa, M., Sato, Y., Kawashima, M., Furumichi, M. & Tanabe, M. KEGG as a reference resource for gene and protein annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, D457–D462 (2016).

Li, H. F., Mcgrath, S. P. & Zhao, F. J. Selenium uptake, translocation and speciation in wheat supplied with selenate or selenite. New Phytol. 178, 92–102 (2008).

Zhao, X. Q., Mitani, N., Yamaji, N., Shen, R. F. & Ma, J. F. Involvement of silicon influx transporter OsNIP2;1 in selenite uptake in rice. Plant Physiol. 153, 1871–1877 (2010).

Gupta, M. & Gupta, S. An overview of selenium uptake, metabolism, and toxicity in plants. Front Plant Sci. 7, 2074 (2017).

Haitikainen, H., Xue, T. L. & Piironen, V. Selenium as an anti-oxidant and pro-oxidant in ryegrass. Plant Soil. 225, 193–200 (2000).

Xue, T. L., Hartikainen, H. & Piironen, V. Antioxidative and growth-promoting effect of selenium on senescing lettuce. Plant Soil. 237, 55–61 (2001).

Zhang, M. et al. Improving soil selenium availability as a strategy to promote selenium uptake by high-Se rice cultivar. Environ Exp Bot. 163, 45–54 (2019).

Gao, H. H. et al. Separation of selenium species and their sensitive determination in rice samples by ion-pairing reversedphase liquid chromatography with inductively coupled plasma tandem mass spectrometry. J Sep Sci. 41, 432–439 (2018).

Hu, Z. Y. et al. Speciation of selenium in brown rice fertilized with selenite and effects of selenium fertilization on rice proteins. Int J Mol Sci. 19, 1–15 (2018).

Zhang, M. et al. Selenium uptake, dynamic changes in selenium content and its influence on photosynthesis and chlorophyll fluorescence in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Environ Exp Bot. 107, 39–45 (2014).

Han, D. et al. Selenium uptake, speciation and stressed response of Nicotiana tabacum L. Environ Exp Bot. 95, 6–14 (2013).

Shahid, M. A. et al. Selenium impedes cadmium and arsenic toxicity in potato by modulating carbohydrate and nitrogen metabolism. Ecotox Environ Safe. 180, 588–599 (2019).

Dai, H. P., Wei, S. H., Skuza, L. & Jia, G. L. Selenium spiked in soil promoted zinc accumulation of Chinese cabbage and improved its antioxidant system and lipid peroxidation. Ecotox Environ Safe. 180, 179–184 (2019).

Zahedi, S. M., Abdelrahman, M., Hosseini, M. S., Hoveizeh, N. F. & Tran, L. S. P. Alleviation of the effect of salinity on growth and yield of strawberry by foliar spray of selenium nanoparticles. Environ Pollut. 253, 246–258 (2019).

Ahsan, U. et al. Role of selenium in male reproduction: A review. Anim Reprod Sci. 146, 55–62 (2014).

Zhang, Y. et al. Nanoselenium promotes the product quality and plant defense of Salvia miltiorrhiza by inducing tanshinones and salvianolic acids accumulation. Ind. Crops Products. 195, 116436 (2023).

Feng, R. W., Wei, C. Y., Tu, S. X. & Wu, F. Effect of Se in the uptake of essential elements in Pteris vittata L. Plant Soil. 325, 123–132 (2009).

Luo, H. W. et al. Foliar application of sodium selenate induces regulation in yield formation, grain quality characters and 2-acetyl-1-pyrroline biosynthesis in fragrant rice. BMC Plant Biol. 19, 1–12 (2019).

Wang, Y. D., Wang, X. & Wong, Y. S. Proteomics analysis reveals multiple regulatory mechanisms in response to selenium in rice. J Proteomics. 75, 1849–1866 (2012).

Ulhassan, Z. et al. Dual behavior of selenium: Insights into physio-biochemical, anatomical and molecular analyses of four Brassica napus cultivars. Chemosphere 225, 329–341 (2019).

Handa, N. et al. Selenium modulates dynamics of antioxidative defence expression, photosynthetic attributes and secondary metabolites to mitigate chromium toxicity in Brassica juncea L. plants. Environ Exp Bot. 161, 180–192 (2019).

Dai, Z. H. et al. Dynamics of selenium uptake, speciation, and antioxidant response in rice at different panicle initiation stages. Sci Total Environ. 691, 827–834 (2019).

Hasanuzzaman, M., Hossain, M. & Fujita, M. Exogenous selenium pretreatment protects rapeseed seedlings from cadmium induced oxidative stress by upregulating antioxidant defense and methylglyoxal detoxification systems. Biol Trance Elem Res. 149, 248–261 (2012).

Li, W. et al. Emerging LC−MS/MSbased molecular networking strategy facilitates foodomics to assess the function, safety, and quality of foods: Recent trends and future perspectives. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 139, 104114 (2023).

Gigolashvili, T. & Kopriva, S. Transporters in plant sulfur metabolism. Front plant sci. 5, 442 (2014).

Shrift, A. & Ulrich, J. M. Transport of selenate and selenite into astragalus roots. Plant Physiol. 44, 893–896 (1969).

Bork, C., Schwenn, J. D. & Hell, R. Isolation and characterization of a gene for assimilatory sulfite reductase from Arabidopsis thaliana. Gene 212, 147–153 (1998).

White, P. J. Selenium accumulation by plants. Ann. Bot. 117, 217–235 (2016).

White, P. J. & Broadley, M. R. Biofortification of crops with seven mineral elements often lacking in human diets: Iron, zinc, copper, calcium, magnesium, selenium and iodine. New Phytol. 182, 49–84 (2009).

Goncalves, A. C. et al. Physical and phytochemical composition of 23 Portuguese sweet cherries as conditioned by variety (or genotype). Food Chem. 335, 127637 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Special Fund for the Construction of Modern Agricultural Industrial Technology System (CARS-21), Natural Science Foundation of Hubei Province (JCZRLH202500141), the Postdoctor Project of Hubei Province (2024HBBHCXB005), the Youth Science Foundation Project of Hubei Academy of Agricultural Sciences (2024NKYJJ38), the Hubei Key Research Project (2023BBB079), the Central Finance Supported Promotion and Demonstration Project of Forestry Science and Technology (2024TG25), Natural Science Foundation of Hubei Province (2022CFC040), Hubei Provincial Key R&D Program Project (2025BBB011), and the Enshi Technology Research Project (D20220075).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Wu-Xian Zhou, Jinwen You, and Yu-Ying Yang conceived the research; Yu-Qing Duan and Da-Rong Li performed the experiments; Yu-Ying Yang, Xiao-Gang Jiang, Hua Wang, Hai-Hua Liu, and Meide Zhang analyzed most data of the experiments; Yu-Ying Yang and Wu-Xian Zhou wrote the article.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, Y., Duan, Y., Li, D. et al. Transcriptome analysis of differentially expressed genes in lily leaves under selenite application. Sci Rep 16, 2504 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32270-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32270-w