Abstract

Plant-based products have emerged as a high-rise need. Thymus linearis, a hilly herb, represents a promising resource of natural bioactive compounds. This work targets multiple impacts of essential oil of T. linearis, examining its chemical variability across different geographical regions, giving a GC-MS-based metabolite profile of T. linearis essential oil, along with tests done in vitro and in silico to see how well it works as an antioxidant (DPPH, ABTS, and metal chelating activity), antidiabetic (α-amylase assay), and antibacterial (disc-diffusion against E. coli and B. subtilis) agent. The essential oil was extracted via hydrodistillation from three locations: Ranikhet (RTL), Almora (ATL), and Lohaghat (LTL). Thymol (61.95% to 73.05%) was dominant in all three locations, with RTL being the maximum. The components like γ-terpinene, p-cymene, and β-(E)-caryophyllene were prominent in T. linearis in varying percentages. Oxygenated monoterpenes dominated the essential oils (RTL: 79.24%, ATL: 77.24%, LTL: 65.28%). RTL showed the best results in the DPPH test and exhibited antibacterial activity producing inhibition zones, even at a lower amount (200 µg/mL) against E. coli and B. subtilis strains that was similar to the standard. LTL demonstrated the best α-amylase assay. In silico molecular docking of thymol, γ-terpinene, and p-cymene was found to strongly attach to target proteins, backing up the lab results. PASS prediction and Lipinski’s rule were also employed to support the present study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

There has been a notable global shift recently, favoring the use of herbal medicines and natural therapeutic agents. This trend emerges from apprehensions regarding the side effects of synthetic medicines, with people seeking more versatile options. Plant-based bioactive compounds, particularly essential oils that are high in phenolics and terpenoids, have become very popular because of their various health benefits. Thymus linearis Benth. commonly known as linear-leaved thyme, is a perennial herb belonging to the family Lamiaceae that flourishes in the hilly, high-altitude regions of Uttarakhand, India1. The plant typically grows as a small shrub, reaching heights of 10–30 cm, with woody stems and a compact, bushy habit. Its leaves are narrow and elongated, measuring about 5–15 mm in length, and they are often covered in fine hair2. Traditionally, it has been acknowledged for its medicinal potential, having been used for its antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant properties, along with aroma healing1,3,4. Its therapeutic efficacy is dependent on its chemical components, such as phenolics, terpenoids, and flavonoids, which is the sole reason for plant-based products to gain utmost attention. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) also considers thymol as (GRAS) “generally recognized as safe” for use as a food flavoring by the European Commission5. The notable chemical polymorphism in the genus Thymus is well-known. Different living and non-living factors cause changes in the plant compounds found in essential oil, as well as their effectiveness6.

A wide range of benefits are reported for T. linearis, such as anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antipyretic, analgesic, antidiabetic, antiproliferative, antimalarial, and antimicrobial activities7,8,9,10. The oils and extracts are very common in the cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, perfumes, and flavor sectors9. Recently, scientific interest in T. linearis has grown, with researchers investigating its chemical makeup (thymol, carvacrol, and γ-terpinene) and potential applications in modern medicine, food preservation, and agriculture. It is hypothesised that various biotic and abiotic factors significantly influence the biosynthesis of phytochemicals leading to varied chemical profile10. Subsequently, this study was designed to seek a better understanding of phytochemical diversity in T. linearis by analyzing its metabolites through GC-MS and assessing their efficacy against different biological assays. Following this, merging molecular docking and PASS prediction methods along with cluster analysis were explored to validate the experimental results. Unraveling the chemodiversity and bioefficacy of T. linearis not only intensifies the molecular complexity present in nature but also paves the way for harnessing the region-based phytochemical signatures in the tracking of next-generation, plant-based natural therapeutics.

As far as we know, this is the first integrative report establishing direct link of regiospecific diversity (a natural tool kit that enhances treatment options) and compared their plant chemicals with multiple biological activities, including computational validation.

Materials and methods

Collection of plant and identification

The plant, T. linearis, was collected in fresh from three locations in Uttarakhand: Soni (Ranikhet, RTL), Kasar (Almora, ATL), and Kolidhek (Lohaghat, LTL), with coordinates and altitudes of approximately 29.6462°N, 79.4323°E (1,869 m); 29.6211°N, 79.6712°E (2116 m); and 29.4160°N, 80.0922°E (1754 m), respectively (Supplementary Fig. S1). The collection was strictly undertaken in full compliance with institutional, national, and international research guidelines. The species is not listed in the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species or under CITES regulations. The herbarium vouchers have been submitted in the herbarium of Regional Ayurveda Research Institute (RARI) located in Almora (Thapla), Uttarakhand. The identification was done by Dr. Deepshikha Arya for which accession numbers were assigned to the respective voucher specimens (Ranikhet, 29967; Almora, 29963; and Lohaghat, 29966).

Extraction of the essential oil

Three distinct locations (RTL, ATL, LTL) were selected for the extraction of essential oils from T. linearis using hydro-distillation with the help of the Clevenger-type apparatus (Winzer) over three hours. A 5000 mL round-bottom flask held the plant material (400 g) and heated at 80–100 °C for 3 h, allowing the essential oil of the plant material to vaporize11. The analysis was conducted in triplicate to ensure the adequacy of oil extraction. Later, anhydrous sodium sulfate was used for drying any excess moisture present in essential oil, followed by storing the oil in dark vials at 4 °C with Teflon-sealed covers, preserving the integrity and quality of the essential oils.

Essential oil analysis

At JNU (Jawaharlal Nehru University) in New Delhi, the AIRF (Advanced Instrumentation Research Facility) used GC (gas chromatography) and GC-MS (gas chromatography-mass spectrometry) to look at the essential oil.

Gas chromatography and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry

Shimadzu’s 2010 GC-FID and GC-MS instruments evaluated essential oils. For the analysis, a capillary column was employed (30 m length × 0.25 mm ID), with a film thickness of 0.25 μm. Nitrogen functioned as the carrier gas, flowing at 46.5 mL/min. The detector was maintained at 290 °C, while the oven and injector at 280 °C. The injection mode employed was split, administering 0.2 µL of unadulterated oil with a fixed split ratio6. The temperatures were fixed for ion source (280 °C), interface (230 °C) and GC-MS (270 °C). Split mode was used a 100-split ratio. Spectra were obtained at 70 eV for 45–650 amu masses. Under consistent experimental conditions, the retention index (RI) was determined using a n-alkane homologous series (C9-C33). The data was compared to mass spectral libraries of NIST (version 4.1) and WILEY (7th edition) followed by comparing the spectra and matching the calculated (RIc) values to the pre-documented data12.

Antioxidant activity

Three methods employed for the calculation of essential oil sample’s potential against two standards (BHT and catechin) are indicated below:

2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl radical scavenging assay (DPPH)

To analyze the potential of samples, a regression equation was plotted following the study by Joshi et al.6. To start, five varying concentrations (10 µg/mL to 50 µg/mL) were used, where lower IC50 values indicated higher DPPH scavenging activity. The solution was made by mixing 5 mL of DPPH (0.2 mM, 0.0197 mg/mL) in methanol with 1 mL of an oil solution in methanol. The sample test tubes were incubated for approximately 30 min, and at 517 nm absorbance was measured vs. blank. The experiment was done in triplicate, with the reaction mixture (DPPH radical solution) excluding the test solution acting as the control. For reference, standards like butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT) and catechin were used.

Inhibition percentage for all the samples was calculated as follows:

where Ac=Absorbance of control (517 nm); As=Absorbance of test sample (517 nm).

To further evaluate the concentration-independent standardized value of antioxidant potential, the antioxidant activity index (AAI) was calculated13.

ABTS radical scavenging assay

The standards, BHT, along with catechin, were used to assess this assay14. To prepare the ABTS·+ radical, equal volumes of 7 mM ABTS and 2.45 mM potassium persulfate were mixed and kept in the dark at ambient conditions for 12–16 h to allow complete reaction. Post-ABTS·+ solution mixing with methanol, absorbance at 734 nm was measured. The same was done for different oil samples (5–25 µg/mL) and conventional antioxidants (BHT and catechin) after incubating them for 6 min. The data was executed in triplicate. Formula for a radical scavenging percentage:

where Ac=Absorbance of control (734 nm); As = Absorbance of test sample (734 nm).

Metal-chelating assay

The oil’s essential components were studied for Fe2+ chelation using a spectrophotometer15. For the study, we mixed 0.1 mL of 2 mM FeCl2·4 H2O, 0.2 mL of 5 mM ferrozine, and 4.7 mL of methanol with varying amounts of essential oils at concentrations of 10 µg/mL and 50 µg/mL. The solution was stirred and kept undisturbed, and at 562 nm, the absorbance was measured after incubating them in the dark for approximately 20 to 30 min. The data was executed in triplicate. BHT served as the standard, and percentage inhibition was computed with the help of the given formula:

where Ac=Absorbance of control (562 nm); As=Absorbance of test sample (562 nm).

Antidiabetic activity

Various concentrations (20–100 µg/mL) of essential oils (RTL, ATL, LTL) along with the standard drug acarbose were evaluated for their α-amylase inhibitory activity. Following the study by Oboh et al. (2015)16, samples of different amounts were added to 0.02 M phosphate buffer (pH 6.0) with 0.5 mg/mL pancreatic α-amylase enzyme (EC 3.2.1.1). Following this, the samples to be tested were introduced to this mixture and pre-incubated for 10 min at a temperature of 60 °C. Subsequently, 500 µg/mL of a 1% starch solution formulated in the identical buffer was introduced to each reaction mixture sample at predetermined intervals. 0.05 mL of dinitro-salicylic acid reagent was added and incubated at 60 °C for 20 min. Later, boiling water was used for incubation of the test tubes for 10 min, followed by cooling them to room temperature. Following the addition of 2 mL of distilled water to the reaction mixture, at 540 nm, the absorbance was recorded. The results were compared to a standard control consisting of buffer rather than sample extract. To ensure reproducibility, experiment was done in triplicate. The findings were computed utilizing the following equation:

where Ac = Absorbance of control (540 nm); As = Absorbance of test sample (540 nm).

Antibacterial activity

The method used for antibacterial activity was disc-diffusion, which involved preparing clean, nutrient-rich agar plates17. Following this, for 1 h, the autoclave was run at 121 °C and a pressure of 15 psi to sterilize the medium. The media (15–20 mL) was added to each petri dish, and the plates were placed in laminar airflow and exposed to UV light for approximately 15 min to allow the medium to solidify. With this, bacterial test organisms—gram-positive Bacillus subtilis (MTCC 441) and gram-negative Escherichia coli (MTCC 64)—were disseminated through an inoculation tube to the test plates. A loop was used to inoculate nutrient agar plates with bacterial strains. Next, sterile Whatman AA filter paper discs (6 mm diameter) were soaked with standard S (200 µg/mL) and essential oils C1 (200 µg/mL), C2 (100 µg/mL), and C3 (50 µg/mL) to create the microbial lawn. These discs were then placed at equal distances from each other in the microbe-inoculated plates. Prior to incubation, it was stabilized at 37 °C in a laminar airflow for approximately one hour for bacteria culture for 24 h. The inhibitory zones (ZOI) were measured. The experiment was conducted three times. Ciprofloxacin was employed as a reference standard for antibacterial activity.

In silico molecular Docking

A computational technique to forecast the intermolecular framework that outputs the appropriate binding between the ligands and protein was employed. AutoDock 4.2.6 was utilized with the existing empirical free energy function. A grid map with 40 x-, y-, and z-points and 1.000 Å spacing was used for all dockings. From the docking search, the conformation having the least energy of docking was picked as the best conformation. The number of torsions was adjusted from 0 to 6. Stable ligand-protein interactions were explored by hydrogen bonding. The complicated conformations of protein and ligand were examined via the PyMOL program and UCSF Chimera with Accelry’s Discovery Studio Visualizer, encompassing hydrogen bonds and bond lengths. For the analysis, thymol, γ-terpinene, and p-cymene were used, and their 3-D structures along with PubChem CIDs which were saved in SDF format and later converted to PDB format. The Protein Data Bank (PDB) provided target proteins’ crystal structures under IDs 7CFZ, 1OSE, 1J1J, and 1PXQ. The components were docked against respective proteins, and binding energy (ΔG) was calculated to measure the affinity of the ligand-protein complex6.

In silico evaluation via PASS tool

PASS predicted the numerical value in this study, verifying the experimental results. The molecular structure for prediction is anticipated in the MOL or SDF file). In PASS analysis, a compound’s possible biological effects are predicted, with each effect assigned a probability of being active (Pa) or inactive (Pi). For a specific molecule, only actions with Pa greater than Pi are considered feasible for a particular drug6.

Lipinski’s rule

To evaluate ligand oral bioavailability and drug-likeness (thymol, γ-terpinene, p-cymene), Lipinski’s rule of five was applied. According to the rule, a molecule possesses the criteria of molecular weight: 500 Da or less, logP: 5 or less, hydrogen bond donors: 5 or less, and hydrogen bond acceptors: 10 or less. Any molecule matching these criteria is considered suitable for further pharmacokinetics and drug discovery studies6.

Statistical analysis

In the present study, SPSS 16.0, along with Origin Pro 2025 (for graphing and analysis) and MS Excel, was used to create all the graphs and perform the statistical analysis (correlation and clustering). The mean ± standard deviation is provided for the data. For the calculation of IC50 values, a linear regression equation was used.

Results and discussion

Percentage yield of essential oil

The extracted essential oil yield, along with the parameters of altitude and rainfall, are represented in Fig. 1. The oil yield varied, with the highest yield recorded in the ATL collection (1.4%±0.1) followed by LTL (1.2% ± 0.1) and RTL (0.8% ± 0.9). The essential oil of RTL showed a dark yellow color, and other sites displayed a yellow color. The essential oil yield was observed to increase with altitude and decrease with rainfall. Previous reports also support the present finding17,18,19, indicating that several climatic parameters such as altitude and rainfall influence the biosynthesis and accumulation of essential oils.

GC/GC-MS profile

Major constituents identified in RTL essential oil

Thirty of the 36 components identified a total percentage of 99.29%. Out of 99.29%, thymol constituted 73.05%, followed by 6.30% of γ-terpinene and 5.44% of p-cymene (Supplementary Fig. S2; Table 1).

Major constituents identified in ATL essential oil

According to the report, the essential oil was composed of 44 components, with 33 of them identified, accounting for 99.29% of the total composition. Thymol was the primary component, comprising 68.72%, followed by γ-terpinene at 6.51% and p-cymene at 5.42% (Supplementary Fig. S3; Table 1).

Major constituents identified in LTL essential oil

Out of the 42 components in total, 33 identified components constituted 96.82% essential oil percentage, with thymol being 61.95%, p-cymene at 9.72%, and γ-terpinene at 8.28% (Supplementary Fig. S4; Table 1).

Based on the class of composition, the essential oils in all three samples exhibited notable variation in their concentration (Fig. 2). Oxygenated monoterpenes were the most abundant, suggesting a stronger potential for medicinal and therapeutic properties, ranging from 67.6% in LTL to 80.93% in RTL. The phytochemicals of this class are well documented for antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and analgesic applications6. This was followed by monoterpene hydrocarbons (16%, ATL to 26.04%, LTL), sesquiterpene hydrocarbons (1.24%, RTL to 2.74%, ATL), and oxygenated hydrocarbons being the least, ranging from 0.49% in ATL to 0.62% in RTL. This suggests that LTL is suitable for aromatherapy and insecticidal properties, while ATL has potential for long-lasting formulations1,20,21.

The findings demonstrate the impact of several living and non-living elements on the chemical make-up of T. linearis essential oil. Thymol was the main ingredient in all three samples, with amounts of 68.72% in ATL, 73.05% in RTL, and 61.94% in LTL, but the levels vary and were observed to be the highest in the plants collected from higher altitudes (r = .861**) (Supplementary Table S1). Additionally, there were also differences in other important components like γ-terpinene and p-cymene, with the LTL region having greater amounts (8.28% and 9.72%) than the ATL (6.30% and 5.42%) and RTL (6.51% and 5.44%) regions. A significant negative correlation (r = − .675*) was noted for γ-terpinene content (Supplementary Table S1). Additionally, variations in β-(E)-caryophyllene, carvacrol, and β-bisabolene suggested the plant’s adaptation to environmental stressors in different regions (showed significant correlations with altitude).

In conclusion, the composition of essential oil is shaped by the synergistic effect of various factors6. The inherent variability of plants, along with specific chemotypes and their responses to various conditions, highlights the opportunities for industries reliant on plant-based essential oils and other products, requiring careful consideration of factors such as growth stages, season of collection, soil type, temperature, area of collection, and processing method. Thymol has been found to be a stable main chemical in this study and in earlier studies of Thymus species1,7,10,11. Therefore, improving one’s knowledge of how these factors interact is crucial for optimizing the quality of essential oil, ensuring its sustainability for future applications.

Antioxidant activity

The antioxidant activity analyzed via three assays (DPPH, ABTS, and metal chelating) suggested RTL to depict the best potency with the lowest and nearly comparable IC50 value with standards used, which underscores our sample plant for future herbal applications with no or fewer side effects. The plant proves to interact with the free radicals to stabilize them by stopping the chain reaction mechanism. The present study’s IC50 value surpasses that of previous studies on Thymus species from other geographical locations1,7,22,23,24.

As seen in Fig. 3, the results are expressed as IC50 ± SD for all three locations, where BHT (the standard) showed the highest antioxidant activity with the least IC50: 10.79 ± 1.08 µg/mL (AAI: 1.83) (strong antioxidant) for DPPH, 16.41 ± 0.08 µg/mL for ABTS, and 18.42 ± 0.07 µg/mL for metal chelating activity. With IC50 values of 13.22 ± 0.08 µg/mL (DPPH) (AAI: 1.49) (strong antioxidant), 18.30 ± 0.05 µg/mL (ABTS), and 20.43 ± 0.06 µg/mL (metal chelating), the RTL sample nearly followed similar potency as BHT. With IC50 values of 21.43 ± 0.06 µg/mL (AAI: 0.92) (moderate antioxidant), 22.53 ± 0.05 µg/mL, and 28.06 ± 0.06 µg/mL for DPPH, ABTS, and metal chelating, respectively, the ATL sample exhibited moderate antioxidant capacity. The LTL sample, which reported the highest IC50 values of 23.79 ± 0.07 µg/mL (DPPH) (0.83) (moderate antioxidant), 30.62 ± 0.06 µg/mL (ABTS), and 33.44 ± 0.06 µg/mL (metal chelating), depicted the lowest potential as a radical scavenger. Some significant negative correlations of antioxidant potential were found with thymol (ABTS IC50; r = − .734*), carvacrol (ABTS IC50; r = − .823*) and β-(E)-caryophyllene (DPPH IC50; r = − .677*) ((Supplementary Table S1). These findings from the study validate RTL as the most powerful of all three examined samples, with high thymol content matching the effectiveness of the synthetic antioxidant, BHT.

Thymol has been the predominant component in all the studies, which acts as a radical scavenger, conferring free radical scavenging capacity. Operating via multifarious mechanisms, the essential oil mostly passes through the hydrogen atom transfer (HAT) and the single electron transfer (SET) pathways in DPPH and ABTS scavenging activity, respectively15,25. Thymol, a phenolic compound, gives a hydrogen atom or a single electron to reactive free radicals (DPPH and ABTS) to stabilize the compounds by the formation of phenoxyl radicals, which get resonance stabilized, further terminating chain propagation26. At the same time, the essential oils show the potential to sequester Fe2+ (transition metal ion) with the help of the hydroxyl group and other polar functional groups. This stops Fe2+ from participating in the Fenton reaction, which is a critical pro-oxidative mechanism that produces highly reactive hydroxyl radicals (•OH) from hydrogen peroxide26. The essential oil of T. linearis efficiently lowers the formation of secondary radicals responsible for oxidative stress.

A joint effort to target radicals and their sources, which works together with the body’s antioxidant abilities, is seen27. Further, RTL shows a nearly similar value of IC50 when compared to the conventional standard used. This highlights its potential as an herbal, multifunctional antioxidant tool for use in nutraceuticals, cosmetic compositions, and pharmaceutical industries.

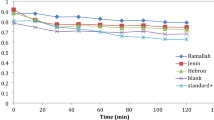

Antidiabetic activity

To analyze the results, concentration-dependent inhibition was seen for various concentrations of the essential oil with the standard. Although none of the samples were as effective as acarbose (standard), they still showcased nearly similar IC50 values ranging from 24.62 ± 0.64 µg/mL to 35.54 ± 0.20 µg/mL (Fig. 4). Moving towards history, α-amylase (found in saliva and pancreatic juices) specifically cleaves complex carbohydrates at the α-1,4-glycosidic bond, which facilitates conversion into simpler forms28. Thymol inhibits the enzyme, and carbohydrates take a longer time to break down and absorb, which helps to control postprandial hyperglycemia. As reported by Sarvanan and Pari (2016), thymol exhibits anti-hyperglycemic and anti-hyperlipidemic effects in C57BL/6J mice with high-fat diet-induced type 2 diabetes29. This is a boon for people with diabetes to control their blood sugar levels stably after meals. So, amylase inhibitors help control diabetes. Several ongoing hunts are searching for natural sources of amylase inhibitors to develop antidiabetic drugs that are safer and more effective with fewer or no side effects30,31.

In T. linearis, acarbose serves as the positive control (standard inhibitor) to validate the experimental setup. LTL was the most effective at stopping the activity (IC50 = 24.62 µg/mL), RTL was the least effective (IC50 = 35.54 µg/mL), and ATL had a moderate effect with an IC50 of 33.31 µg/mL (Fig. 4). The difference in the inhibition action is attributed to the different chemical makeup, as LTL consists of p-cymene (9.72%), γ-terpinene (8.28%), and thymol (61.95%). This suggests that these compounds work together to make enzyme inhibition stronger. Concentration of p-cymene (r = − .989, p < .01) and γ-terpinene (r = − .974, p < .01) correlated negatively with IC50 (Supplementary Table S1). ATL and RTL have a higher percentage of thymol as compared to LTL, but the superior activity of LTL is likely due to balanced synergistic effects of multiple bioactive compounds rather than a single component27.

Antibacterial activity

The results of antibacterial potential depicted from the disc-diffusion method are summarized in Supplementary Fig. S5 and Table 2, where we can see that the essential oils demonstrated very high biological activity with nearly similar values of ZOI as the standard ciprofloxacin. RTL showed a consistent antibacterial effect on both bacterial strains. At a concentration of 200 µg/mL (C1), RTL produced inhibitory zones measuring 37.15 mm for E. coli and 36.08 mm for B. subtilis, which were nearly equivalent to the standard. Furthermore, it stayed active even at lower concentrations, showing its strength and stable effect compared to ATL and LTL. ATL had the strongest effect on B. subtilis (44.93 mm) but had a sharp drop at lower concentrations. LTL worked well against E. coli, but RTL surpassed it, being the best. The essential oil from T. linearis contains a lot of phenolic compounds and terpenes, especially thymol (61.95–73.05%), γ-terpinene, p-cymene, and carvacrol, which are all powerful antibacterial agents that work together through physical and chemical (redox) reactions. This provides reliable indication of bactericidal potential opening avenues for future in-depth studies. The major component, thymol (phenolic hydrophobic), validates its positive correlation (r = .944, p < .01) and is majorly responsible for the bactericidal effect (Supplementary Table S1). On the contrary, the bacterial cell wall contains lipopolysaccharides (gram-negative) and teichoic acid (gram-positive) (Fig. 5). Since thymol has a lipophilic nature, it can penetrate the lipid bilayer of the bacterial cell wall32. It allows the membrane to become more permeable, and the entry of the phytochemicals of the essential oil becomes easier. Thymol is also responsible for biofilm inhibition33. Altogether, this causes important parts of the cell to seep out and eventually die. This is how thymol works as a safe and natural antibacterial drug by destabilizing the membrane. The bactericidal action is not solely due to one component but a synergistic effect of all major and minor components21. This synergism possibly explains why, in some cases, the inhibition zones of the essential oil even surpassed that of the standard, as the combined action of phenolic and terpenoid constituents enhances membrane permeability and oxidative stress. The multifarious mechanisms attribute firstly the lipophilic insertion to break up membranes. Two components of essential oil, thymol and carvacrol, are lipophobic phenols with small molecules that allow them to be inserted into phospholipid bilayers30. These disrupt the packing of fatty acyl chains, cause destabilization of the lipids, change in membrane permeability, ion loss and cell lysis21,34. Secondly, phenolics in essential oil create oxidative stress by disrupting electron transport chain (ETC) in bacterial cells generating reactive oxygen species (ROS)35,36. Subsequently, Fenton reaction generates hydroxyl radicals (•OH) which damage lipids, proteins and DNA, impairing cellular functions37,38. Thirdly, while the present study primarily focuses on antibacterial potential, the phenolics may act as autoinducers to stop this quorum signalling and biofilm formation, which inhibits gene expression and alteration in the regulatory and metabolic pathways, and makes the present study useful in the formation of natural quorum quenchers39.

In silico molecular docking

The docking studies were analyzed in the form of binding energy (ΔG) as depicted in Table 3, where we can see positive interactions of the three major phytoconstituents against four target proteins: NADPH oxidase activator 1 (7CFZ2), porcine α-amylase (1OSE), translin (1J1J), and subtilisin A (1PXQ) (Figs. 6, 7, 8 and 9). Thymol and p-cymene had a strong binding affinity for NADPH oxidase activator 1 (-4.60 kcal/mol and − 5.00 kcal/mol) when it demonstrated antioxidant potential (Table 3). The residue interactions (TYR:6 and PRO:59) involved in making reactive oxygen species (ROS) were also seen, which supports the RTL chemotype to show the strongest antioxidant effect. The strongest effect of thymol (-6.30 kcal/mol) was observed when bound to porcine α-amylase, including interaction with several catalytic site residues (HIS:299, TYR:62, LEU:165, and VAL:163). Equally responsible was p-cymene (-6.20 kcal/mol), exhibiting a balanced effect suggesting slower breakdown of carbohydrates. Thymol is still the main inhibitor, though, because it has a high binding affinity and interacts with residues. Thymol and p-cymene also showed excellent docking with translin (-4.90 kcal/mol and − 5.0 kcal/mol) and subtilisin A (-3.90 kcal/mol and − 4.50 kcal/mol) when it came to antibacterial activity. The interactions were also found to be with hydrophobic and polar residues (VAL:208, ASP:211, and CYS:13). These interactions enhance the ability of phytochemicals to block enzymes by targeting the bacterial membrane. γ-Terpinene was moderate among the three ligands, but its efficacy cannot be overlooked, being a direct co-actor in all the interactions, enhancing the synergistic effect6. Overall, these results show strong alignment between translational relevance and experimental assays, validating that the key bioactive compounds operate through compatible biochemical pathways.

PASS prediction (in silico)

Activity Prediction Spectra for Substances (PASS) predicts an organic drug-like molecule’s broad biological potential. The results predicted the Pa (probably “to be active”) and Pi (probably “to be inactive”) values of the major components (Table 4). It can be inferred from the data that major components are solely responsible for validating the experimental results of the present study. These computational data prove to be an important tool for drug discovery in future applications.

Lipinski’s rule

The three major phytoconstituents of the present study do not violate Lipinski’s rule (Table 5). They meet the criteria, proving the oral bioavailability of the compound for drug discovery in future studies.

Cluster analysis

The cluster revealed a distinct chemical relationship (Fig. 10). Two clusters form, with C1 consisting of essential oil samples from ATL and RTL, joined at a high similarity index of 0.93. This cluster is dominated by oxygenated monoterpenes, primarily thymol (68.72–73.05%). It also contains minor monoterpene hydrocarbons, including γ-terpinene (6.30–6.51%) and p-cymene (5.42–5.44%), along with tiny traces of phenolic monoterpene carvacrol and the sesquiterpene hydrocarbon β-bisabolene. In contrast, Cluster C2 from the Lohaghat (LTL) sample presents a distinct profile, characterized by a relatively lower percentage of oxygenated monoterpenes (thymol, 61.95%) and higher concentrations of monoterpene hydrocarbons, particularly p-cymene (9.72%) and γ-terpinene (8.28%). Carvacrol was not detected, indicating a notable chemotypic variation. Additionally, LTL showed slightly elevated levels of sesquiterpene hydrocarbons like β-(E)-caryophyllene and β-bisabolene. The clustering pattern suggests that environmental factors, particularly altitude and microclimate, significantly affect the biosynthetic pathways of essential oil constituents in T. linearis, leading to region-specific chemotypes.

Conclusion

The present study holds an account of the exploration of phytochemicals in T. linearis across various ecogeographical locations of Uttarakhand. GC-FID and GC-MS profiling revealed thymol as the active ingredient in all three sites, albeit in different concentrations, showcasing its remarkable stability and longevity in high-altitude regions. The monoterpene hydrocarbons including γ-terpinene and p-cymene were found in significant percentages, enhancing the essential oil’s aroma and antimicrobial properties. Oxygenated monoterpenes (borneol, thymol, carvacrol, and linalool) were predominant, comprising 67.6% (LTL) to 80.93% (RTL), thereby underlining their probable efficacy. A thymol isomer, carvacrol with high bioactivity, was abundant in ATL and LTL but was insignificant in RTL, indicating regio-specific biosynthetic variation. The essential oil of RTL describes the best antioxidant and antibacterial effects, attributing it to the high thymol content, while LTL depicted maximum antidiabetic potential. The phytoconstituents were used to generate two clusters, which again support the learning of chemodiversity. Thymol emerged as the principal contributor along with synergistic enhancement of γ-terpinene and p-cymene to support the bioactivities and mechanistic roles. The elevated score of thymol in the in silico study also reconfirms its exceptional potential as an antiseptic and antibacterial for oral health, respiratory issues, food preservation, household cleaning, insect repellent, and traditional medicine. The given research, while providing integrative insights into the metabolite composition and biological potential of T. linearis Benth., some limitations warrant acknowledgement. Only three geographical locations and one seasonal collection were undertaken which may not be a proper representation of the complete phytochemical variation influenced by several biotic and abiotic factors. Although, in vitro and in silico tests demonstrate useful mechanistic findings; however, in future, in vivo and clinical research work for large scale commercialisation of T. linearis is necessary to confirm its efficacy.

Data availability

The data will be made available on request from the corresponding author.

References

Kabdal, T. et al. Seasonal variation in the essential oil composition and biological activities of Thymus linearis Benth. Collected from the Kumaun region of Uttarakhand, India. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 103, 104449. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.BSE.2022.104449 (2022).

Afonso, A. F., Pereira, O. R., Válega, M., Silva, A. M. S. & Cardoso, S. M. Metabolites and biological activities of Thymus zygis, Thymus pulegioides, and Thymus fragrantissimus grown under organic cultivation. Molecules 23, 1514. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules23071514 (2018).

Tohidi, B., Rahimmalek, M. & Trindade, H. Review on essential oil, extracts composition, molecular and phytochemical properties of Thymus species in Iran. Ind. Crops Prod. 134, 89–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2019.02.038 (2019).

Nadeem, H. A. et al. Comparative phytochemical study of methanolic and ethanolic extracts of Thymus linearis and their antibacterial and antioxidant potential. Biomed. Chromatogr. 38, e5808. https://doi.org/10.1002/bmc.5808 (2024).

Marchese, A. et al. Antibacterial and antifungal activities of thymol: A brief review of the literature. Food Chem. 210, 402–414. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.04.111 (2016).

Joshi, M. et al. Influence of altitudinal variation on the chemodiversity and in-vitro antioxidant potential of essential oils of Micromeria biflora (Buch. -Ham. Ex D. Don) Benth. From Uttarakhand. India Biochem Syst. Ecol. 122, 105019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bse.2025.105019 (2025).

Hussain, A. I. et al. Chemical composition and bioactivity studies of the essential oils from two Thymus species from the Pakistani flora. LWT - Food Sci. Technol. 50, 185–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.LWT.2012.06.003 (2013).

Naz, A., Saeed, M., Hussain, M. M. & Ishaq, M. S. Vitro phytochemical and antimicrobial screening of Thymus linearis. Bangladesh J. Pharmacol. 10, 21–26. https://doi.org/10.3329/bjp.v10i1.20639 (2015).

Verma, R. S. et al. Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of the essential oils isolated from the herbage and aqueous distillates of two Thymus species. J. Essent. Oil Bear. Plants. 19, 936–943. https://doi.org/10.1080/0972060X.2014.935071 (2016).

Verma, N. & Shukla, S. Impact of various factors responsible for fluctuation in plant secondary metabolites. J. Appl. Res. Med. Aromat. Plants. 2 (4), 105–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jarmap.2015.09.002 (2015).

Kumar, A. et al. Chemical composition, antimicrobial activity, kinetics and mechanism of action of Himalayan-thyme (Thymus linearis Benth). J. Essent. Oil Res. 32, 64–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/10412905.2019.1662337 (2020).

Adams, R. P. Identification of Essential Oil Components by Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry (2007).

Faustino, H., Gil, N., Baptista, C. & Duarte, A. P. Antioxidant activity of lignin phenolic compounds extracted from kraft and sulphite black liquors. Molecules 15, 9308–9322. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules15129308 (2010).

Moller, A. C. et al. Antioxidant and anti-proliferative activity of essential oil and main components from leaves of Aloysia polystachya harvested in central Chile. Molecules 26, 131. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26010131 (2021).

Shahidi, F. & Zhong, Y. Measurement of antioxidant activity. J. Funct. Foods. 18, 757–781. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jff.2015.01.047 (2015).

Oboh, G. et al. In vitro studies on the antioxidant property and Inhibition of α-amylase, α-glucosidase, and angiotensin I-converting enzyme by polyphenol-rich extracts from cocoa (Theobroma cacao) Bean. Pathol. Res. Int. 49287 https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/549287 (2014).

Joshi, V. et al. GC–MS fingerprinting, nutritional composition, in vitro Pharmacological activities and molecular Docking studies of Piper Chaba from Uttarakhand region. 3 Biotech. 14, 158. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13205-024-03996-7 (2024).

Mahdavi, M., Jouri, M. H., Mahmoudi, J., Rezazadeh, F. & Mahzooni-Kachapi, S. S. Investigating the altitude effect on the quantity and quality of the essential oil in Tanacetum Polycephalum Sch.-Bip. Polycephalum in the Baladeh region of nour. Iran. Chin J. Nat. Med. 11, 553–559. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1875-5364(13)60100-4 (2013).

Fernández-Sestelo, M. & Carrillo, J. M. Environmental effects on yield and composition of essential oil in wild populations of Spike lavender (Lavandula latifolia Medik.). Agriculture.10, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture10120626 (2020).

Rani, A. et al. Chemodiversity and antioxidant potential of the essential oil of fresh leaves of Cinnamomum zeylanicum Blume from Uttarakhand. J. Essent. Oil Bear. Plants. 25, 783–795. https://doi.org/10.1080/0972060X.2022.2128895 (2022).

Kowalczyk, A., Przychodna, M., Sopata, S., Bodalska, A. & Fecka, I. Thymol and thyme essential oil—new insights into selected therapeutic applications. Molecules 25, 4125. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules25184125 (2010).

Chandra, M., Prakash, O., Bachheti, R. K., Kumar, M. & Pant, A. K. Essential oil composition, phenolic constituents, antioxidant and Pharmacological activities of Thymus linearis Benth. Collected from Uttarakhand region of India. J. Essent. Oil-Bear Plants. 19, 277–289. https://doi.org/10.1080/0972060X.2014.935070 (2016).

Aazza, S. et al. Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and anti-hyperglycaemic activities of essential oils from Thymbra capitata, Thymus albicans, Thymus caespititius, Thymus carnosus, Thymus Lotocephalus and Thymus Mastichina from Portugal. Nat. Prod. Commun. 11, 1029–1038 (2016).

Laftouhi, A. et al. Effect of temperature and water stress on the antioxidant and antidiabetic activities of Thymus vulgaris essential oil. Trop. J. Nat. Prod. Res. 8, 5785–5793. https://doi.org/10.26538/tjnpr/v8i1.11 (2024).

Altunayar-Unsalan, C. & Unsalan, O. Molecular structure, antioxidant potential, and Pharmacokinetic properties of plant flavonoid blumeatin and investigating its Inhibition mechanism on Xanthine oxidase for hyperuricemia by molecular modeling. ACS Omega. 9, 13284–13297. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.3c10083 (2023).

Liu, Y. et al. Protective effects of natural antioxidants on inflammatory bowel disease: thymol and its Pharmacological properties. Antioxidants 11, 1947. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox11101947 (2022).

Abbasi, S., Gharaghani, S., Benvidi, A. & Rezaeinasab, M. New insights into the efficiency of thymol synergistic effect with p-cymene in inhibiting advanced glycation end products: a multi-way analysis based on spectroscopic and electrochemical methods in combination with molecular Docking study. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 150, 436–451. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpba.2017.12.042 (2018).

Liu, P. et al. Maltogenic amylase: its structure, molecular modification, and effects on starch and starch-based products. Carbohydr. Polym. 319, 121183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2023.121183 (2023).

Saravanan, S. & Pari, L. Protective effect of thymol on high fat diet induced diabetic nephropathy in C57BL/6J mice. Chem. Biol. Interact. 245, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbi.2015.11.033 (2016).

Zhang, Y. et al. A spatially confined biological heterogeneous cascade nanozyme composite hydrogel combined with nitric oxide gas therapy enhances psoriasis and diabetic wound treatment. Chem. Eng. J. 507, 160629. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2025.160629 (2025).

Su, M. et al. Astragalus improves intestinal barrier function and immunity by acting on intestinal microbiota to treat T2DM: a research review. Front. Immunol. 14, 1243834. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1243834 (2023).

Perez, A. P. et al. The anti-MRSA biofilm activity of Thymus vulgaris essential oil in nanovesicles. Phytomedicine. 57, 339–351 https://doi.org/https://doi.org/. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phymed.2018.12.025 (2019).

Kerekes, E. B. et al. Anti-biofilm effect of selected essential oils and main components on mono- and polymicrobic bacterial cultures. Microorganisms. 7, 345. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms7090345 (2019).

Mukha, I. P. et al. Antimicrobial activity of stable silver nanoparticles of a certain size. Appl. Biochem. Microbiol. 49, 199–206. https://doi.org/10.1134/S0003683813020117 (2013).

Nosaka, Y. & Nosaka, A. Y. Generation and detection of reactive oxygen species in photocatalysis. Chem. Rev. 117, 11302–11336. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00161 (2017).

Seixas, A. F. et al. Bacterial response to oxidative stress and RNA oxidation. Front. Genet. 12, 821535. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2021.821535 (2022).

Shoudho, K. N., Uddin, S., Rumon, M. M. H. & Shakil, M. S. Influence of physicochemical properties of iron oxide nanoparticles on their antibacterial activity. ACS Omega. 9, 33303–33334. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.4c02822 (2024).

McNeilly, O., Mann, R., Hamidian, M. & Gunawan, C. Emerging concern for silver nanoparticle resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii and other bacteria. Front. Microbiol. 12, 652863.https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2021.652863 (2021).

Lima, E. M. F., Winans, S. C. & Pinto, U. M. Quorum sensing interference by phenolic compounds – A matter of bacterial misunderstanding. Heliyon 9, e17657. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e17657 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to Kumaun University, Nainital for providing financial support through KUIFR grant (KU/RDC/IFR/2023-24/1127). M. J. gratefully acknowledges INSPIRE program of DST, New Delhi.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Manisha Joshi: Data curation; Writing - original draft, Methodology, Investigation. Geeta Tewari : Conceptualization, Supervision; Writing - review & editing; Formal analysis. Chitra Pande : Supervision. Girish C. Kharkwal : Formal analysis. Lalit M. Tewari : Resources. Vibha Joshi : Methodology. Manisha Duseja : Resources. Aabha Gangwar : Formal analysis. Vishwajeet Bachhar : Methodology.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Joshi, M., Tewari, G., Pande, C. et al. Metabolite profiling and evaluation of antioxidant, antidiabetic, and antibacterial potential of Thymus linearis Benth. supported by molecular docking and PASS prediction. Sci Rep 16, 2494 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32317-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32317-y