Abstract

Myeloperoxidase (MPO) is associated with conduction inhomogeneity. We hypothesized that MPO in selectively drained pericardial fluid (PCF), a direct window into the cardiac microenvironment, may improve postoperative atrial fibrillation (POAF) risk prediction beyond existing risk scores. A total of 469 consecutive patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) were enrolled in this study (n = 201 in derivation cohort and n = 268 in validation cohort). The primary outcome was new-onset POAF within the first 7 days postoperatively. MPO concentrations were measured in selectively drained PCF and peripheral blood at baseline, 0 and 6 h postoperatively. We further compared MPO levels between pure pericardial fluid and mixed drainage fluid (via Y-connector). A new prediction model, the pcMPO-AF rule, was developed using multivariable logistic regression and validated internally using bootstrapping and externally in an independent cohort. Approximately 98.0% of patients underwent off-pump CABG. POAF occurred in 31.8% and 35.1% of the derivation and validation cohorts, respectively. Pericardial MPO at 6 h postoperatively emerged as the strongest independent predictor of POAF. MPO concentrations in selectively drained PCF were 25-fold higher than mixed drainage samples and 1,648-fold higher than serum levels (both P < 0.001). The pcMPO-AF rule demonstrated good discrimination, with AUCs of 0.908 in derivation and 0.865 in validation cohorts, outperforming POAF, CHA₂DS₂-VASc, and HATCH scores. MPO in selectively drained PCF is a potent biomarker of POAF. The pcMPO-AF rule integrated PCF biomarkers with clinical factors, providing superior predictive performance by capturing both the vulnerable atrial substrate and acute inflammatory trigger.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Postoperative atrial fibrillation (POAF) is the most common complication after cardiac surgery, with an incidence ranging from 20% to 40% after coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) procedures1,2. It typically peaks between 2 and 4 days after surgery and tends to recur frequently, especially within the first postoperative week3. Although considered a self-limiting condition3, it has been associated with a 5-fold increase in atrial fibrillation (AF) recurrence and a 2-fold increase in mortality and stroke within 30 days4,5. This underscores the urgent need for accurate risk stratification tools to identify high-risk patients who may benefit from targeted preventive strategies.

The pathophysiology of POAF is considered multifactorial, arising from a transient surgical trigger acting upon a pre-existing vulnerable atrial substrate3. Current established clinical risk models, including the POAF, CHA₂DS₂-VASc, and HATCH scores6,7,8, primarily rely on preoperative characteristics such as age and hypertension, which reflect the underlying atrial substrate. Their discriminatory ability is often moderate (area under the curve [AUC], 0.57–0.77) and provides limited consideration of postoperative inflammatory milieu9, now recognized as a key contributor to POAF pathogenesis3.

Mounting evidence suggests that surgery-related local inflammation and oxidative stress, rather than systemic inflammation, are key contributors to POAF3,10. Among inflammatory mediators, myeloperoxidase (MPO) has emerged as a particularly promising candidate. Released by activated neutrophils following cardiac surgery, MPO causes oxidation, nitration, and chlorination of cardiac tissue, creating an intensive pro-oxidative environment that promotes atrial remodeling11. Clinical studies demonstrate that elevated MPO levels predict AF recurrence following catheter ablation12. Experimental evidence from canine atrial incision models13 and our canine CABG studies11 demonstrate that MPO infiltration in atrium correlates with conduction inhomogeneity, reduced levels of connexin 43, shortened atrial effective refractory periods, and increased AF vulnerability, while MPO-deficient mice were protected from AF14.

Pericardial fluid (PCF) represents the optimal sampling source for assessing cardiac inflammatory responses, as it provides direct access to the immediate cardiac microenvironment and is a reservoir of locally synthesized bioactive substances15. This concept is validated by clinical evidence showing that enhanced pericardial drainage reduces POAF rates by 34%16. While a few preliminary single-center studies with small sample sizes, including our own, have explored biomarkers such as interleukin-6 (IL-6) and MPO in mixed pericardial and mediastinal drainage fluid collected via Y-connectors11,17, and mitochondrial DNA from mediastinal drainage fluid18, no study has investigated biomarkers in pure postoperative PCF. This selective sampling approach should more accurately reflect the direct cardiac inflammatory milieu than mixed drainage and aligns with contemporary surgical practice, where separate chest tube placement is preferred over merged drainage systems19,20.

We hypothesized that MPO measured in selectively drained pure PCF would demonstrate superior predictive accuracy compared to existing risk scores by capturing the localized inflammatory intensity central to POAF pathogenesis. Therefore, we conducted this prospective, multicenter study to develop and externally validate the first prediction model based on pure PCF biomarkers, establishing both its clinical performance and superiority over conventional approaches.

Methods

This study’s reporting was prepared following the TRIPOD + AI (Transparent Reporting of a Multivariable Prediction Model for Individual Prognosis or Diagnosis + Artificial Intelligence) checklist21 to ensure thorough reporting.

Study population: development and validation cohorts

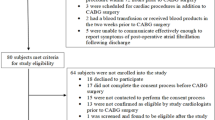

This prospective, multicenter study examined two independent cohorts undergoing CABG. All procedures were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Capital Medical University (approval number: 2023SY120). All patients provided written informed consent for study participation and data use. The derivation cohort consisted of 201 consecutive patients who underwent surgery between January and September 2023. For external validation, a separate cohort of 268 patients undergoing CABG at a second center between January and July 2024 was enrolled. As previously described11, the inclusion criteria required patients to be aged ≥ 18 years and undergoing first-time elective isolated CABG with preoperative sinus rhythm. Exclusion criteria included patients with a history of AF, acute myocardial infarction requiring emergency cardiac surgery, associated intracardiac procedures, an implanted pacemaker or implantable cardioverter defibrillator, active infection, chronic inflammatory disorders, impaired immune system, malignancies, or liver failure. Patients receiving anti-inflammatory therapy or hemodialysis were also excluded.

Perioperative management

All patients withheld aspirin for 5–7 days preoperatively. Preoperative coronary angiography was performed in all patients during this hospitalization. All procedures were performed via median sternotomy. In contrast to previous use of Y-connecter to merge two tubes into one11, two separate chest tubes are now routinely placed postoperatively. One tube was positioned in the anterior pericardial space, and the other was placed either in the anterior mediastinum or in the pleural cavity, depending on intraoperative findings. Each tube was independently connected to a vacuum-assisted drainage system. The pericardium was partially closed in all patients. Postoperatively, all patients received immediate sedation with propofol and dexmedetomidine. Except for those with contraindications, patients received metoprolol starting on the first day after CABG. Amiodarone was not routinely used unless POAF occurred. The surgical procedures abided by the local hospital protocols, and the research protocol did not interfere with the management of study patients.

Evaluation of POAF

The primary endpoint was the occurrence of POAF, defined as new-onset AF sustained for 30 s or more22. Cardiac rhythms were continuously monitored during the first 7 postoperative days using a bedside monitor (M8002A, Philips, Amsterdam, the Netherlands), telemetry (M3290A, Philips), or an electrocardiogram (ECG) patch recorder (EPAJ-PAH-1 A, Shanghai Telecardio, China). ECG patch recorders were employed to ensure that all patients received 7 days of continuous monitoring, reducing the risk of missing POAF episodes, particularly in those who only underwent 2–3 days of bedside 24-hour ECG monitoring in the immediate postoperative period. These wireless recorders, adhered to the upper left chest, were capable of storing up to 14 days of continuous ECG data. An additional 12-lead ECG was obtained to confirm AF episodes when arrhythmia was clinically suspected. The diagnosis of POAF was based on rhythm strips or 12-lead ECGs and confirmed by a blinded cardiologist. All episodes of POAF were reviewed and adjudicated by a centralized committee of cardiac electrophysiologists.

Measurement of myeloperoxidase

Our team previously measured MPO concentrations in mixed drainage fluid at post-op 6 h, 12 h, and 18 h, and found that the post-op 6 h MPO level had the strongest predictive value for POAF (OR, 19.215)11. Furthermore, given that POAF can occur as early as 12 h after surgery, predictive biomarkers should ideally be assessed prior to this time window. Based on these findings, we selected two early postoperative time points—post-op 0 h and post-op 6 h—for sample collection.

PCF and blood samples were collected at 0 and 6 h postoperatively. In addition, pre-anesthesia blood samples were collected. Blood samples were drawn from the arterial sheath. PCF was collected from the pericardial chest tube, which was emptied before each collection and allowed to accumulate for 30 min or less. Samples were centrifuged at 1500 g for 15 min, and serum or supernatant was stored at −80 °C. After collection was completed, all specimens were transported to the central laboratory for batch analysis. MPO concentrations were measured using the Quantikine Human Myeloperoxidase Immunoassay (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Laboratory personnel were blinded to study group designation.

Covariates

Clinical data were collected from the medical records by trained clinicians who were blinded to the purpose of the study using standardized data-collection sheets. Potential variable selection was based on literature search and included preoperative, operative, and postoperative factors (Table 1). Preoperative laboratory values were defined as the most recent measurements before surgery, while postoperative laboratory values referred to those obtained on the first postoperative day. Intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) use was recorded only if it occurred preoperatively or intraoperatively. Data quality was checked regularly for incorrect entries and missing data.

Statistical analysis

Continuous data were reported as mean and standard deviation (SD) or median [interquartile range (IQR) 25th-75th percentile] for normally and non-normally distributed data, respectively. Categorical data were expressed as frequencies or percentages. The χ2, Wilcoxon rank-sum, or t test was used as appropriate to examine baseline differences between those with and without incident POAF. Repeated-measures ANOVA assessed temporal changes in MPO levels, with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Univariate logistic regression identified candidate predictors (P < 0.05), which were then included in a multivariable logistic regression using backward stepwise selection. To simplify and improve the clinical applicability of the prediction model, continuous variables were first evaluated in the univariate analysis, then converted into categorical variables according to the optimal cutoff values determined by receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis using the maximum Youden index. To avoid collinearity and overfitting, only the strongest MPO-related associations with POAF were included in the final multivariable analysis.

Model performance was evaluated in terms of discrimination (AUC), calibration (Hosmer-Lemeshow test, HL), and clinical utility (decision curve analysis, DCA). To minimize overfitting, internal validation was performed using 1,000 bootstrap resamples. A nomogram was constructed using the rms package in R. In constructing the nomogram, we applied the standard scoring algorithm whereby the predictor with the largest absolute regression coefficient (β) is assigned 100 points, and all remaining predictors receive points proportional to their β values.

We also compared the newly developed prediction model with the POAF, CHA₂DS₂-VASc, and HATCH scores — all of which have been validated for predicting POAF in patients undergoing CABG. These risk scores were calculated as published (Table S1). To evaluate the comparative predictive performance, we assessed (1) differences in AUCs, (2) Brier scores, and (3) continuous net reclassification improvement (NRI) and integrated discrimination improvement (IDI) metrics. The DeLong test was applied to compare AUCs using the riskRegression package in R. The same package was also used to compute the Brier score. Continuous NRI and IDI were estimated using the nricens package.

We further compared MPO levels from pure pericardial fluid with that of MPO from mixed pericardial and mediastinal drainage. However, a contemporaneous collection of both sample types was precluded by a shift in standard clinical practice, as pericardial and mediastinal chest tubes are now routinely placed and drained separately. Therefore, to facilitate this comparison, we conducted a secondary analysis leveraging data from our previous prospective cohort study in which mixed drainage fluid was collected via a Y-connector11. The original study prospectively enrolled 137 CABG patients and collected drainage fluid samples from merged pericardial and mediastinal tubes for MPO measurement. Further details have been described previously11. The original study protocols, including patient inclusion criteria, timing of sample collection (post-op 6 h was the common collection timing), MPO assay procedures were reviewed and found to be identical to those of the current multicenter investigation. Data integrity and completeness for the key variables from the prior dataset were re-verified. Ethical approval for the original study included permission for secondary analyses, and no additional patient consent was required. MPO concentrations between the historical mixed-fluid cohort and the current pericardial-fluid cohort were then compared using appropriate statistical tests, such as an independent samples t-test or Mann-Whitney U test, based on the data distribution. Less than 10% of covariate data were missing and were addressed with multiple imputation. Statistical analyses were conducted with R statistical software version 4.4.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) and SPSS version 26.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). A two-tailed P-value was set at 0.05 for statistical significance.

Sample size calculation

For the derivation cohort, we focused on statistical power provided by the proposed prediction model on the basis of the reliability of predictions, rather than on specific predictors. The minimum events per variable to obtain good prediction is commonly set at 10 for logistic regression analysis23. With an anticipated POAF incidence of 28% and an anticipated selection of 5 final factors, the minimum required sample size must be at least 179 to meet the criterion of events per variable ≥ 10.

To estimate the required sample size for the validation cohort, ROC analysis was used to assess the discriminative ability of the established prediction model. Based on an expected incidence of POAF of 28%, a target sensitivity of 0.80, a specificity of 0.80, and a two-sided significance level (α) of 0.05, the calculated minimum sample size required was 245 patients.

Results

Study population: derivation and validation cohorts

A total of 469 patients were included in the study (Figure S1). The derivation cohort (n = 201) and the validation cohort (n = 268) did not differ significantly in terms of demographic characteristics or in perioperative care, including AF prophylaxis and anti-inflammatory strategies (Table 1). The vast majority of patients underwent off-pump CABG, accounting for 98.5% in the derivation cohort and 97.4% in the validation cohort. During the first seven postoperative days, POAF occurred in 31.8% (64/201) of patients in the derivation cohort and in 35.1% (94/268) of patients in the validation cohort. Among all patients who developed POAF, the median time to onset was 44 h postoperatively (IQR, 30–69 h), with the earliest episode occurring at 14 h and the latest at 108 h after surgery. Of the POAF cases, six episodes resolved spontaneously, one was terminated by electrical cardioversion, and the remaining cases were successfully treated with amiodarone.

Pericardial MPO at 6 h postoperatively as the strongest predictor of POAF

The temporal trends of MPO levels in PCF and serum are illustrated in Fig. 1A. A two-way repeated-measures ANOVA demonstrated significant differences in the temporal changes of pericardial and serum MPO levels between POAF and non-POAF groups (both P < 0.001). Patients who developed POAF had significantly higher pericardial MPO levels at 6 h (P < 0.001) and serum MPO levels at baseline (P < 0.001). Among the MPO-related indices (Fig. 1B), pericardial MPO at post-op 6 h (AUC 0.831) and serum MPO at baseline (AUC 0.765) emerged as robust predictors of POAF. The optimal cutoff values were determined from ROC analyses using the maximum Youden index, yielding thresholds of 389,054.9 ng/mL (sensitivity 90.6%, specificity 62.0%) for pericardial MPO at post-op 6 h and 163.7 ng/mL (sensitivity 59.4%, specificity 79.6%) for serum MPO at baseline.

Pericardial and serum MPO levels are elevated in patients with POAF. A. Patients who developed POAF exhibited higher pericardial and serum MPO across the 6-hour time course (Pgroup < 0.001 for both), especially at 6 h postoperatively in pericardial fluid and baseline in blood (Ppost−op 6 h < 0.001, Pbaseline < 0.001, respectively). ***P < 0.001 in comparisons between groups after Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons at each time point. Pbaseline and Ppost−op 6 h values were calculated by Mann-Whitney U test. B. ROC curves for the prediction of POAF. Among the five parameters, the strongest predictors were pericardial MPO at post-op 6 h (AUC = 0.831) and serum MPO at baseline (AUC = 0.795), with optimal cutoff values of 389,054.9 ng/mL (sensitivity 90.6%, specificity 62.0%) and 163.7 ng/mL (sensitivity 59.4%, specificity 79.6%), respectively. Abbreviations: MPO, myeloperoxidase; POAF, postoperative atrial fibrillation; ROC, receiver operating characteristic; AUC, area under the curve.

MPO in PCF may originate either from local intrapericardial production or from the systemic circulation. To explore the primary source, we compared MPO concentrations in PCF and peripheral blood. Our analysis revealed that MPO levels in the PCF were 1,648-fold higher than those in the blood (P < 0.001). These findings suggested that local intrapericardial production is likely the predominant source of MPO in drainage.

To further investigate whether MPO from selectively drained PCF more accurately reflects the local cardiac inflammatory milieu than mixed drainage samples, we conducted a secondary analysis comparing MPO concentrations from the current cohort with those from our previous study that utilized a Y-connector for mixed mediastinal and pericardial drainage11. This cross-study comparison was feasible because both studies employed identical protocols (Table S2): patient inclusion/exclusion criteria, MPO assay procedures, and sampling timing (post-op 6 h). Importantly, both studies excluded patients receiving anti-inflammatory therapy, eliminating the primary pharmacological confounder of MPO levels. Neither study employed prophylactic amiodarone for POAF prevention, and the use of β-blockers did not differ significantly between cohorts. Pericardial MPO at post-op 6 h was 25-fold higher than those in mixed drainage fluid (median, 410,772.1ng/mL [IQR, 238,070.4–876,647.1) vs. 16,503.0ng/mL [IQR, 10,265.3–25,942.5]; P < 0.001) (Figure S2A). This substantial difference remained consistent in subgroup analysis stratified by age and POAF status (Figure S2B and S2C). These findings suggest that the immediate pericardial space maintains a distinct biochemical milieu despite semi-sutured pericardium allowing communication with surrounding thoracic spaces. While cross-study limitations require cautious interpretation, these results provide preliminary evidence favoring pure PCF over mixed drainage for biomarker studies.

Collectively, these findings suggest that pericardial MPO at post-op 6 h represents a potential predictor of POAF, derived predominantly from local inflammation.

Development of pcMPO-AF rule

Candidate predictors and their univariable associations with POAF are presented in Table S3. Seven variables with P < 0.05 were selected as candidates for multivariable logistic regression. The final model, named pericardial MPO (pcMPO)-AF rule, included five predictors: two clinical risk factors, age ≥ 66.5 years (OR 2.53; 95%CI, 1.08–5.94) and left atrial diameter ≥ 56.5 mm (4.40; 95%CI, 1.53–12.63); one surgical factor, IABP use (16.04; 95%CI, 2.04–126.36); MPO-related indices, serum MPO at baseline ≥ 163.7 ng/mL (OR 7.55; 95%CI, 3.11–18.33) and pericardial MPO at post-op 6 h ≥ 389,054.9 ng/mL (OR 21.90; 95%CI, 7.32–65.49) (Table 2). We then calculated C-statistics to evaluate the incremental value of MPO in predicting POAF, beyond clinical and surgical risk factors, and in combination with them (Fig. 2). The model including only clinical risk factors yielded a C-statistic of 0.735. The addition of surgical factor led to a modest improvement (C-statistic 0.760; △C = 0.025; P = 0.074). When serum MPO at baseline was added, the C-statistic increased from 0.734 to 0.805 (△C = 0.071; P = 0.010), whereas the addition of pericardial MPO at post-op 6 h improved from 0.734 to 0.860 (△C = 0.126; P < 0.001). The highest discriminative performance was observed when both serum and pericardial MPO were added to the model, resulting in a C-statistic of 0.904 (△C = 0.170; P < 0.001), suggesting substantial incremental value of MPO in enhancing POAF risk prediction beyond clinical and surgical factors alone.

Incremental Predictive Performance of Models for POAF. The first model includes clinical variables (age and left atrial diameter), with an AUC of 0.701. The second model combines a surgical variable (intra-aortic balloon pump) and clinical variables, increasing the AUC to 0.734. The highest AUC was observed when both serum and pericardial MPO were added to the model, which improved the AUC from 0.734 to 0.904. Abbreviations: AUC, area under the curve; MPO, myeloperoxidase; POAF, postoperative atrial fibrillation.

We further developed a nomogram based on the final model (Fig. 3). Relative weights for each predictor were derived from their β values. The assigned points for all predictors were then summed to obtain a total score, which corresponded to the predicted probability of POAF.

Predictive performance and validation of the model

To assess the discriminatory performance of the pcMPO-AF rule, ROC curve analysis was performed. The model was internally validated using a bootstrapping resampling approach and yielded an AUC of 0.908 (95%CI, 0.868–0.943) in the derivation cohort. In the external validation cohort, the model achieved an AUC of 0.865 (95%CI, 0.816–0.913), also demonstrating excellent discrimination (Fig. 4A and B). Consistent predictive performance across multiple patient subgroups further supports the robustness and generalizability of the model (Table S4).

Model calibration was evaluated using the Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test and calibration plots. The HL test indicated good agreement between predicted and observed outcomes in both the derivation cohort (P = 0.173) and the validation cohort (P = 0.774). Calibration plots further supported the model’s good fit in both cohorts (Fig. 4C and D).

To evaluate clinical applicability, decision curve analysis was performed. The DCA curves demonstrated favorable net benefit across a range of threshold probabilities in both cohorts, supporting the clinical utility of the model for predicting POAF risk (Fig. 4E and F). These findings suggest that the model may serve as a valuable tool for perioperative risk stratification and decision-making in patients undergoing CABG.

Nomogram of the pcMPO-AF rule for POAF risk prediction. The prediction is based on the following logistic model: logit(POAF) = − 4.521 + 3.086× (pericardial MPO at post-op 6 h ≥ 389,054.9) + 2.775 × (IABP use) + 2.022 × (serum MPO at baseline ≥ 163.7) + 1.481 × (left atrial diameter ≥ 56.5) + 0.928 × (age ≥ 66.5), where each predictor is coded as 1 if the criterion is met or 0 otherwise. The nomogram can be used by determining the position of each variable on the corresponding axis, drawing a line to the point axis, and adding points from all variables. Next, a line was drawn from the total point axis to determine POAF probabilities using the bottom line of the nomogram. Abbreviations: MPO, myeloperoxidase; POAF, postoperative atrial fibrillation; IABP, intra-aortic balloon pump.

Validation of the model’s predictive performance for estimating the risk of POAF. The AUCs were 0.908 (A) for the derivation cohort and 0.865 (B) for the external validation cohort. Calibration curves showed good agreement between predicted and observed outcomes in both the derivation (C) and external validation (D) cohorts. Decision curve analysis indicated that the nomogram conferred greater net benefit than the “All or None” strategy across a range of threshold probabilities in both the derivation (E) and external validation (F) cohorts. Abbreviations: POAF, postoperative atrial fibrillation; AUC, area under the curve.

Comparison of the POAF, CHA₂DS₂-VASc, and HATCH scores

Given the comparable demographic characteristics and similar model performance between the derivation and validation cohorts, we combined the two cohorts to facilitate a comparative evaluation of the newly created POAF risk prediction model against other established risk scores. Three current scores were selected for comparison: the POAF, CHA₂DS₂-VASc, and HATCH scores. Compared with these scores, the pcMPO-AF rule demonstrated superior discrimination and better calibration. Furthermore, it significantly improved both the continuous NRI and the IDI, indicating enhanced predictive performance (Table 3). In addition, the incorporation of PCF MPO into each of the three clinical scores (POAF, CHA₂DS₂-VASc, and HATCH) substantially improved their predictive abilities, further supporting the potential predictive value of pericardial MPO for POAF (Table 3).

Online POAF risk prediction calculator

An interactive, user-friendly web-based calculator was developed based on the pcMPO-AF rule to support individualized POAF risk estimation at the bedside. The bedside tool is available at: https://pdmpoaf.shinyapps.io/dynnomapp/.

Discussion

In this prospective, multicenter study, we established for the first time that MPO in selectively drained PCF is a powerful and independent predictor of POAF. While PCF is recognized as a reservoir for inflammatory mediators, its role in the pathogenesis of POAF has remained poorly defined. Only a few studies have explored biomarkers derived from intraoperative PCF24,25, postoperative mediastinal fluid18, or mixed drainage fluid26. Our study, the first to investigate biomarkers in pure postoperative PCF across two independent cohorts, demonstrates that MPO measured at post-op 6 h possesses excellent prognostic utility (AUC 0.831; sensitivity 90.6%). We developed and externally validated the pcMPO-AF rule — a simple, easy-to-remember bedside tool. It is based on two clinical variables (age, left atrial diameter), one surgical factor (IABP use), and two MPO indices reflecting both systemic (serum MPO) and local inflammatory states (pericardial MPO). Compared with established risk scores including the POAF, CHA₂DS₂-VASc, and HATCH scores, our model demonstrated improved discrimination, calibration, and risk reclassification properties.

Although self-terminating, POAF is associated with a 5-fold increase in recurrent AF and increased stroke and cardiovascular mortality3,27. Identifying high-risk patients is therefore clinically important. This enables a personalized approach to secondary prevention, targeting individuals who benefit the most. Current scores, such as the POAF, CHA₂DS₂-VASc, and HATCH scores, demonstrated modest predictive accuracy in our cohort (AUC 0.57–0.63) and previous reports (AUC 0.57–0.77)9. These scores rely largely on clinical risk factors that represent the vulnerable atrial substrate, while potentially underestimating the role of surgery-related inflammatory and oxidative triggers. Although systemic inflammatory markers like C-reactive protein, IL-6, and white blood cell count have been explored28,29, findings remain inconsistent10. Recent evidence suggests that surgery-induced localized inflammation may play a more pivotal role15. PCF is a reservoir of locally synthesized bioactive substances with effects on the modulation of cardiac electrophysiology30. For instance, Nakamura et al. found that intra-operative pericardial instead of plasma brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) levels were associated with POAF in patients undergoing CABG24. Manghelli et al. reported mitochondrial DNA levels from postoperative mediastinal chest tube drainage, but not intraoperative PCF, were associated with POAF18. Our previous work also identified that IL-6 and MPO levels in postoperative mixed drainage fluid were associated with the onset of POAF11,26. The present study is the first to specifically investigate biomarkers in pure postoperative PCF. This decision was based on two considerations: first, the contemporary clinical shift towards separate pericardial and mediastinal drainage makes pure PCF analysis more practical and relevant; second, and more importantly, we hypothesized that pure PCF would more accurately reflect the localized cardiac inflammation central to POAF pathogenesis. Our findings support this hypothesis, revealing that MPO levels in PCF were over 1,600-fold higher than in peripheral blood, suggesting local production as the predominant source. Furthermore, in a secondary analysis comparing our current cohort to a historical cohort using mixed drainage11, MPO concentrations in pure PCF were 25-fold higher. This substantial difference suggests that despite a semi-sutured pericardium, the immediate pericardial space maintains a distinct and intensely inflammatory milieu that is significantly diluted in mixed drainage, thereby supporting the potential advantage of selective sampling. The comparability of this analysis is supported by identical study protocols, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and perioperative care across both studies performed by the same research team.

Among numerous inflammatory mediators in PCF, we chose MPO due to compelling evidence linking it to atrial arrhythmogenesis14. Elevated serum MPO is associated with paroxysmal AF and AF recurrence following catheter ablation12,31. Consistent with our findings, Liu et al. reported an association between MPO in intraoperative PCF and POAF development25. In contrast, Racca et al. found no significant relationship between serum MPO levels on postoperative day 11 and POAF32. The discrepancy between Racca’s results and those of the current studies likely highlights the temporal and compartmental importance of inflammation; acute, localized inflammation in the immediate postoperative period appears more critical than systemic inflammation during the later recovery period. In the present study, we found that pericardial MPO measured at post-op 6 h was the strongest predictor of POAF, superior to that of baseline serum MPO, age, left atrial diameter, and IABP use. Similar findings were identified in our previous preliminary single-center clinical study11, which investigated MPO levels from serum and mixed drainage fluid at baseline and at post-op 6 h, 12 h, and 18 h. That study demonstrated that MPO levels in mixed drainage fluid measured at post-op 6 h, but not serum MPO, were the strongest predictor of POAF. All this evidence suggests that surgery-triggered myocardial inflammation, layered on a preexisting vulnerable atrial substrate (reflected in advanced age and longer left atrial diameter in the present risk model), can exceed the AF threshold and lead to the onset of POAF.

The mechanistic link between MPO and POAF may involve its role in atrial remodeling. MPO is an oxidative enzyme released by activated neutrophils during cardiac surgery15. It creates an intensive pro-oxidative and pro-inflammatory environment within the atrium and PCF, leading to early atrial remodeling11. Ishii et al. found that MPO infiltration in atrium around atriotomy correlated with conduction inhomogeneity13. Rudolph and colleagues, using MPO-deficient mice, demonstrated that MPO is a crucial prerequisite for structural remodeling of atrium, leading to increased vulnerability of AF14. Our canine CABG model observed that increased myocardial and pericardial MPO levels were strongly correlated with increased AF vulnerability, shortened AERP, and attenuated connexin 43 levels, a key gap junction protein involved in electrical coupling17. These pro-arrhythmic changes were reversed by local anti-inflammatory treatment. While current prospective cohort clinical study cannot establish causation, these experimental findings collectively suggest that MPO is not merely a bystander marker but an active contributor to POAF pathogenesis. Definitive proof in humans would require randomized trials of MPO-targeted interventions, which represents a direction for future research.

The pcMPO-AF rule may help identify high-risk patients who may benefit from guideline-recommended prophylaxis such as amiodarone or perhaps anti-inflammatory agents like colchicine27,33. The accessibility of PCF in routine cardiac surgery practice, combined with the non-invasive nature of sampling, makes this a highly translatable approach. In terms of workflow integration, three clinical predictors (age, left atrial diameter, IABP use) in pcMPO-AF rule can be automatically extracted from electronic medical records, minimizing additional burden on clinicians. The remaining two MPO measurements currently require laboratory-based ELISA with approximately 24-hour turnaround time, making the pcMPO-AF rule optimally suited for risk stratification from postoperative day 2 onward. Future bedside MPO assays using colloidal gold immunochromatography technology, which has been successfully applied for rapid point-of-care detection of various cardiac biomarkers34, are currently under development by our team and may enable earlier bedside risk stratification.

Study strengths and limitations

This study has several strengths, including a multicenter design, an independent validation cohort, and a novel focus on a pathogenically relevant biomarker from both serum and pure, localized fluid source which was measured at multiple time points. Clinical data and biospecimens were prospectively collected using standardized procedures by trained personnel, minimizing selection and information bias. Comprehensive pre, intra, and post-operative variables were collected. In addition to bedside monitoring, all participants underwent continuous ECG monitoring using a wireless patch recorder, which reduced the likelihood of missed POAF episodes and enhanced diagnostic accuracy.

Despite these strengths, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, although this represents a multicenter study of selectively drained PCF biomarkers for POAF prediction, the sample size remains relatively small compared to large registry-based studies. Second, our analysis was limited to early postoperative MPO dynamics, based on previous findings identifying optimal predictive value at this interval11. We did not assess later time points, as the earliest onset of POAF in our cohort was 14 h, rendering later measurements less valuable for proactive prediction. Nevertheless, assessment of a more extended time course could offer additional insights. Third, postoperative troponin T (TnT) was not measured in our study. Elevated TnT following cardiac surgery has been associated with serious postoperative complications35, and both MPO and TnT reflect perioperative myocardial injury through different mechanisms—neutrophil-mediated oxidative stress versus direct cardiomyocyte damage. Future studies examining the correlation between MPO and TnT, as well as exploring whether combining MPO with other biomarkers (e.g., IL-6, BNP)17,24, or imaging modalities (e.g., cardiac computed tomography for assessment of epicardial adipose tissue volume or left atrial structural characteristics)36, may further enhance predictive accuracy and mechanistic insight. Fourth, we did not obtain histologic evidence of atrial inflammation, although previous studies have demonstrated MPO activity correlated with the inhomogeneity of atrial conduction (r = 0.774, P < 0.001)13. Fifth, because the model relies on postoperative MPO measurement, it cannot inform preoperative prophylaxis strategies. Finally, as approximately 98.0% of patients in the current study underwent off-pump CABG, the generalizability of our findings to on-pump CABG or other procedures remains uncertain. Future studies are needed to validate these results in broader surgical populations (e.g., valve surgery, on-pump CABG).

Conclusion

This study indicates that MPO from selectively drained PCF measured at post-op 6 h is a powerful and independent predictor of POAF, adding value to established clinical and surgical risk factors. The pcMPO-AF rule, which combines markers of pre-existing atrial substrate with measures of both systemic and localized postoperative inflammation, outperforms current scores in discrimination, calibration, and reclassification. This simple tool could contribute to enhanced perioperative risk stratification and personalized preventive care for patients undergoing CABG. Future studies are needed to assess whether using this model for clinical decision-making can reduce POAF incidence.

Data availability

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this study will be made available by the authors upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- MPO:

-

Myeloperoxidase

- PCF:

-

Pericardial fluid

- POAF:

-

Postoperative atrial fibrillation

- CABG:

-

Coronary artery bypass grafting

- AUC:

-

Area under the curve

- IL-6:

-

Interleukin-6

- IABP:

-

Intra-aortic balloon pump

- DCA:

-

Decision curve analysis

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic

- NRI:

-

Net reclassification improvement

- IDI:

-

Integrated discrimination improvement

References

Gaudino, M., Di Franco, A., Rong, L. Q., Piccini, J. & Mack, M. Postoperative atrial fibrillation: from mechanisms to treatment. Eur. Heart J. 44, 1020–1039. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehad019 (2023).

Perezgrovas-Olaria, R. et al. Differences in postoperative atrial fibrillation incidence and outcomes after cardiac surgery according to assessment method and definition: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 12, e030907. https://doi.org/10.1161/jaha.123.030907 (2023).

Dobrev, D., Aguilar, M., Heijman, J., Guichard, J. B. & Nattel, S. Postoperative atrial fibrillation: mechanisms, manifestations and management. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 16, 417–436. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41569-019-0166-5 (2019).

Caldonazo, T. et al. Atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 165, 94–103e124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtcvs.2021.03.077 (2023).

Almassi, G. H. et al. New-onset postoperative atrial fibrillation impact on 5-year clinical outcomes and costs. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 161, 1803–1810e1803. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtcvs.2019.10.150 (2021).

Mariscalco, G. et al. Bedside tool for predicting the risk of postoperative atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery: the POAF score. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 3, e000752. https://doi.org/10.1161/jaha.113.000752 (2014).

Chua, S. K. et al. Clinical utility of CHADS2 and CHA2DS2-VASc scoring systems for predicting postoperative atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 146, 919–926e911. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtcvs.2013.03.040 (2013).

Emren, V. et al. Usefulness of HATCH score as a predictor of atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass graft. Kardiol Pol. 74, 749–753. https://doi.org/10.5603/KP.a2016.0045 (2016).

Pandey, A. et al. Risk scores for prediction of postoperative atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Cardiol. 209, 232–240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2023.08.161 (2023).

Jacob, K. A. et al. Inflammation in new-onset atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery: a systematic review. Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 44, 402–428. https://doi.org/10.1111/eci.12237 (2014).

Liu, Y. et al. Myeloperoxidase in the pericardial fluid improves the performance of prediction rules for postoperative atrial fibrillation. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 165, 1064–1077e1068. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtcvs.2021.06.027 (2023).

Li, S. B. et al. Myeloperoxidase and risk of recurrence of atrial fibrillation after catheter ablation. J. Investig Med. 61, 722–727. https://doi.org/10.2310/JIM.0b013e3182857fa0 (2013).

Ishii, Y. et al. Inflammation of atrium after cardiac surgery is associated with inhomogeneity of atrial conduction and atrial fibrillation. Circulation 111, 2881–2888. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.104.475194 (2005).

Rudolph, V. et al. Myeloperoxidase acts as a profibrotic mediator of atrial fibrillation. Nat. Med. 16, 470–474. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.2124 (2010).

Liblik, K. et al. The role of pericardial fluid biomarkers in predicting post-operative atrial fibrillation, a comprehensive review of current literature. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 34, 244–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tcm.2023.02.009 (2024).

St-Onge, S. et al. Examining the impact of active clearance of chest drainage catheters on postoperative atrial fibrillation. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 154, 501–508. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtcvs.2017.03.046 (2017).

Liu, Y. et al. Mechanism of IL-6-related spontaneous atrial fibrillation after coronary artery grafting surgery: IL-6 knockout mouse study and human observation. Transl Res. 233, 16–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trsl.2021.01.007 (2021).

Manghelli, J. L. et al. Pericardial mitochondrial DNA levels are associated with atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 111, 1593–1600. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.athoracsur.2020.07.011 (2021).

Le, J., Buth, K. J., Hirsch, G. M. & Légaré, J. F. Does more than a single chest tube for mediastinal drainage affect outcomes after cardiac surgery? Can. J. Surg. 58, 100–106. https://doi.org/10.1503/cjs.006814 (2015).

Lobdell, K. W. & Engelman, D. T. Chest tube management: Past, Present, and future directions for developing Evidence-Based best practices. Innovations (Phila). 18, 41–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/15569845231153623 (2023).

Collins, G. S. et al. TRIPOD + AI statement: updated guidance for reporting clinical prediction models that use regression or machine learning methods. Bmj 385, e078378. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2023-078378 (2024).

Gaudino, M. et al. Posterior left pericardiotomy for the prevention of atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery: an adaptive, single-centre, single-blind, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet 398, 2075–2083. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(21)02490-9 (2021).

Amar, D. et al. A brain natriuretic peptide-based prediction model for atrial fibrillation after thoracic surgery: development and internal validation. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 157, 2493–2499e2491. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtcvs.2019.01.075 (2019).

Nakamura, T. et al. Brain natriuretic peptide concentration in pericardial fluid is independently associated with atrial fibrillation after off-pump coronary artery bypass surgery. Coron. Artery Dis. 18, 253–258. https://doi.org/10.1097/MCA.0b013e328089f1b4 (2007).

Liu, Y., Yang, Y., Yang, X. & Hua, K. Myeloperoxidase levels in pericardial fluid is independently associated with postoperative atrial fibrillation after isolated coronary artery bypass surgery. J. Clin. Med. 11 https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11237018 (2022).

Feng, X. et al. A prediction rule including Interleukin-6 in pericardial drainage improves prediction of New-Onset atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass grafting. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc Anesth. 36, 1975–1984. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.jvca.2021.09.048 (2022).

Van Gelder, I. C. et al. 2024 ESC guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European association for Cardio-Thoracic surgery (EACTS). Eur. Heart J. 45, 3314–3414. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehae176 (2024).

Weymann, A. et al. Haematological indices as predictors of atrial fibrillation following isolated coronary artery bypass grafting, valvular surgery, or combined procedures: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Kardiol Pol. 76, 107–118. https://doi.org/10.5603/KP.a2017.0179 (2018).

Weymann, A. et al. Baseline and postoperative levels of C-reactive protein and interleukins as inflammatory predictors of atrial fibrillation following cardiac surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Kardiol Pol. 76, 440–451. https://doi.org/10.5603/KP.a2017.0242 (2018).

Gaudino, M. et al. Pericardial effusion provoking atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery: JACC review topic of the week. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 79, 2529–2539. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2022.04.029 (2022).

Holzwirth, E. et al. Myeloperoxidase in atrial fibrillation: association with progression, origin and influence of renin-angiotensin system antagonists. Clin. Res. Cardiol. 109, 324–330. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00392-019-01512-z (2020).

Racca, V. et al. Inflammatory cytokines during cardiac rehabilitation after heart surgery and their association to postoperative atrial fibrillation. Sci. Rep. 10, 8618. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-65581-1 (2020).

Nomani, H., Mohammadpour, A. H., Moallem, S. M. H. & Sahebkar, A. Anti-inflammatory drugs in the prevention of post-operative atrial fibrillation: a literature review. Inflammopharmacology 28, 111–129. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10787-019-00653-x (2020).

Rink, S., Kaiser, B., Steiner, M. S., Duerkop, A. & Baeumner, A. J. Highly sensitive Interleukin 6 detection by employing commercially ready liposomes in an LFA format. Anal. Bioanal Chem. 414, 3231–3241. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00216-021-03750-5 (2022).

Duchnowski, P. & Śmigielski, W. Usefulness of myocardial damage biomarkers in predicting cardiogenic shock in patients undergoing heart valve surgery. Kardiol Pol. 82, 423–426. https://doi.org/10.33963/v.phj.99553 (2024).

Brahier, M. S. et al. Machine learning of cardiac anatomy and the risk of New-Onset atrial fibrillation after TAVR. JACC Clin. Electrophysiol. 10, 1873–1884. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacep.2024.04.006 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge all study participants and the clinical support provided by Beijing Anzhen Hospital and Beijing Chaoyang Hospital.

Funding

This study was supported by Beijing Municipal Natural Science Foundation (7252277, Y.L.), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82200351, Y.L.), and the Capital Medical University Innovation Project (XSKY2024147, Y.L.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YSL conceived and designed the study. LL, TWW and TTP analyzed and interpreted the data and wrote the paper with input from all authors. CYG, YS, and HMY were involved in data interpretation and discussion of the results. WZ and TTP helped provide the data. TWW and TTP contributed equally with LL. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Capital Medical University (2023SY120).

Consent for publication

All authors have thoroughly reviewed the manuscript and consent to its publication.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Luo, L., Wang, T., Peng, T. et al. The pcMPO-AF rule for predicting postoperative atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass grafting. Sci Rep 16, 2862 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32318-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32318-x