Abstract

Neutral-atom quantum computing (NAQC) offers distinct advantages such as dynamic qubit reconfigurability, long coherence times, and high gate fidelities, making it a promising platform for scalable quantum computing. Among existing implementations, the Dynamically Field-Programmable Qubit Array (DPQA) architecture has emerged as the most prominent NAQC platform, enabling large-scale, high-fidelity operations through dynamic atom rearrangement and global Rydberg excitation. Despite these strengths, efficiently implementing quantum circuits like the Quantum Fourier Transform (QFT) remains a significant challenge due to atom-movement overheads and connectivity constraints. This paper introduces optimal compilation strategies tailored to QFT circuits on the DPQA architecture, addressing these challenges for both linear and grid-like configurations. By minimizing atom movements, the proposed methods achieve theoretical lower bounds in movement counts while preserving high circuit fidelity. Comparative evaluations against state-of-the-art DPQA compilers demonstrate the superior performance of the proposed methods, which could serve as benchmarks for evaluating the performance of future DPQA compilers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Quantum computing has emerged as a transformative technology capable of solving complex problems in cryptography1, database search2, chemical simulations3, and machine learning4. The rapid advancement of quantum computing research has led to the development of multiple hardware platforms, each with unique strengths and challenges. Among these, superconducting qubits have gained prominence due to their robust control schemes and compatibility with conventional microelectronics5. In the past several years, neutral-atom quantum computing (NAQC) has attracted significant attention for its inherent advantages, including scalability, high qubit connectivity, long coherence times, and superior gate fidelity6,7,8.

In superconducting quantum processors, such as IBM’s heavy-hex architecture, qubits are sparsely arranged to minimize crosstalk. This sparse arrangement, however, requires additional routing steps (mainly through inserting SWAP gates) to facilitate operations between distant qubits. In contrast, NAQC processors, often arranged on a 2D grid, enable two-qubit gates between any two qubits by shuttling them closer. However, longer shuttling distances can increase noise levels. Thus, careful circuit compilation is critical on both platforms to achieve high circuit fidelity.

The Quantum Fourier Transform (QFT) is a foundational component in many quantum algorithms, such as Shor’s factoring algorithm1, phase estimation9, quantum simulation10, amplitude amplification11, and the HHL algorithm for solving systems of linear equations12. Despite its importance, implementing QFT efficiently on current quantum hardware represents a significant challenge. The QFT’s all-to-all interaction pattern requires careful consideration of hardware-specific constraints, particularly in systems with limited qubit connectivity. Due to its core role in quantum computing, QFT optimization has been extensively studied in the literature, see13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20.

In the realm of superconducting quantum processors, Maslov13 proposed a linear-depth transformation for QFT circuits on the linear nearest-neighbor (LNN) architecture, where qubits lie along a single path. Modern superconducting processors often feature more complex connectivity, making it challenging to identify a single Hamiltonian path that visits all qubits. Building on this foundational work, Jin et al.17 introduced efficient mapping techniques tailored to general 2D grid and IBM heavy-hex layouts. Focused on IBM’s heavy-hex architecture, Gao et al.19 proposed specifically optimized linear-depth transformations.

For NAQC processors, costly SWAP gates can be entirely replaced by atom movements (cf.21). While several compilation algorithms have been proposed22,23,24,25, none can guarantee optimal transformations. Moreover, there is currently no benchmarking framework to quantify how close the compiled results are to the theoretical optimum. As a result, existing compiler comparisons have been largely relative rather than absolute. However, designing a general-purpose optimal compiler is fundamentally intractable, since optimal quantum circuit compilation is an NP-hard problem.

In this work, we address these challenges by introducing optimal compilation strategies specifically designed for QFT circuits on the DPQA (Dynamically Field-Programmable Qubit Array) architecture7, which is currently the most prominent NAQC platform. Our contributions are threefold:

-

We propose a Linear Path strategy that achieves the theoretical lower bound in atom-movement count for one-dimensional linear DPQA processors.

-

We extend this approach to two-dimensional (2D) grid-like DPQA processors through a Zigzag Path strategy, which preserves gate parallelism while minimizing movement overhead.

-

We demonstrate that our methods outperform state-of-the-art DPQA compilers, including Enola22 and Atomique23, achieving exponential improvements in movement efficiency and overall circuit fidelity.

Our strategies exploit the unique capabilities of the DPQA architecture, including dynamic qubit reconfigurability and global Rydberg excitation, to optimize circuit execution while minimizing atom movements. In particular, global Rydberg excitation enables the simultaneous application of multiple \(CZ\) gates across the entire array. Our compilation strategies leverage this feature to maximally execute all \(CZ\) gates within each layer in parallel under a single global excitation pulse. Furthermore, we extend our methods to MaxCut QAOA circuits26, demonstrating their versatility for a broad range of quantum algorithms beyond fully connected QFT circuits. By mitigating the inefficiencies associated with atom movement and connectivity constraints, this work advances the realization of practical quantum algorithms on the DPQA architecture.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews NAQC and discusses the challenges of compilation in DPQA. Section 3 revisits QFT circuits and their optimal transformation in the linear superconducting architecture. Section 4 details our proposed method for the DPQA architecture, including strategies for both linear and grid-like processors. Section 5 presents experimental evaluations and comparisons with state-of-the-art algorithms. Finally, Sect. 6 concludes with a summary of our findings and their implications for scalable quantum computing.

Background

In this section, we provide background on quantum computing and NAQC technology and examine the compilation challenges specific to NAQC, especially on the DPQA architecture.

Quantum computing basics

Quantum computing leverages quantum mechanical phenomena such as superposition and entanglement to solve problems that are intractable for classical computers. A quantum circuit, the computational model used in most quantum algorithms, consists of qubits manipulated by single- and multi-qubit gates. These gates form a sequence of unitary operations that evolve the quantum state towards the desired solution. However, the efficiency of quantum circuit execution is heavily influenced by the architecture and physical implementation of qubits. Hardware constraints such as limited qubit connectivity, short coherence times, and low gate fidelity necessitate optimizations tailored to specific platforms.

Neutral-atom quantum computing and the DPQA architecture

Neutral-atom quantum computing (NAQC) has emerged as a promising platform for scalable quantum computation. In this paradigm, neutral atoms—typically rubidium or cesium—serve as qubits, trapped and manipulated using laser and magnetic-field control. Single-qubit operations are realized via Raman laser pulses27,28,29, while two-qubit gates rely on the Rydberg blockade mechanism30,31, where atoms within an interaction radius (\(r_{\textrm{int}}\)) acquire a controlled phase through simultaneous excitation to a Rydberg state. This interaction enables high-fidelity entangling gates such as the controlled-Z (\(CZ\)) gate.

Earlier implementations of neutral-atom processors typically adopted the fixed-array architecture (FAA)27,28, in which atomic positions remain static during computation. These designs feature the ability to perform long-range Rydberg interactions and individually addressable excitation beams to couple distant qubits—requirements that increase optical complexity and limit achievable two-qubit fidelities and scalability. In addition, SWAP gates are often required to route the qubits for two-qubit gates in FAA.

A distinguishing strength of NAQC is its dynamic qubit reconfigurability, enabled by the physically mobile nature of neutral atoms. Using acousto-optic deflectors (AODs) and spatial light modulators (SLMs), atoms can be repositioned dynamically within a two-dimensional grid, enabling arbitrary qubit interactions without SWAP gates. This flexibility introduces a new optimization challenge: minimizing atom-movement time and distance to preserve coherence and fidelity.

The DPQA architecture7,32,33 exemplifies this dynamic paradigm. By integrating coherent atom transport with global Rydberg excitation, DPQA supports high-fidelity entangling gates and reconfigurable connectivity while maintaining scalability. Consequently, DPQA provides an ideal experimental foundation for developing movement-efficient compilation strategies, as explored in this work. In contrast, FAA processors still lag behind DPQA in both two-qubit-gate fidelity and scalability28.

On DPQA processors, qubits are held in two types of traps:

-

Static traps: Generated by SLMs, these traps provide stable qubit positions spaced (e.g., \(2.5 \times r_{\textrm{int}}\)) to minimize crosstalk.

-

Mobile traps: Created by AODs at the intersections of independently controlled rows and columns, each of which can be activated, moved, or deactivated to enable arbitrary rearrangements of atoms within the array.

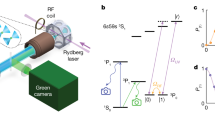

During quantum operations, mobile traps transport atoms to align with the requirements of the circuit, such as executing a \(CZ\) gate. See Fig. 1 for an illustration. To achieve high performance, these movements must be carefully coordinated to minimize total distance and avoid collisions.

Illustration of atom movement and Rydberg excitation in a \(3\times 3\) grid DPQA processor: (a) Atoms are initially positioned at separate grid points (i.e., sites); (b) during the “meet” step, atoms moves so that each interacting pair is co-located at the same grid point; (c) a global Rydberg laser applies \(CZ\) gates simultaneously to all co-located atom pairs; (d) in the “separate” step, atom pairs moves apart, ensuring they occupy different grid points, though not necessarily their initial positions.

Compilation challenges on the DPQA architecture

Quantum circuit compilation for DPQA processors involves converting high-level quantum algorithms into hardware-executable instructions while addressing the platform’s unique characteristics. In superconducting and FAA architectures, qubits are fixed, and connectivity limitations are managed through SWAP gates, which significantly increase circuit depth and reduce fidelity. DPQA eliminates the need for SWAP gates but shifts the focus to optimizing atom movement.

Remark 1

On the DPQA architecture, a SWAP gate can be implemented either

-

by physically moving atoms to exchange their positions or

-

by composing three two-qubit entangling gates, such as

$$\begin{aligned} \textrm{SWAP}(p, q) = \textrm{CNOT}(p, q); \textrm{CNOT}(q, p); \textrm{CNOT}(p, q). \end{aligned}$$

The latter approach, commonly used in superconducting and FAA architectures (also used by Atomique23 in DPQA), incurs significant fidelity loss because each two-qubit operation introduces additional decoherence and control error. In contrast, on the DPQA architecture, physical atom movement is a high-fidelity operation: for instance, Bluvstein et al.7 demonstrated that an atom can traverse a region spanning over 2,000 qubits with less than 0.1% loss in coherence time.

Under practical assumptions (\(f_{\textrm{CZ}} = 0.995\)), a gate-based SWAP would yield a combined fidelity of \(f_{\textrm{CZ}}^3 \approx 0.985\), whereas the equivalent atom movement introduces negligible infidelity. Therefore, on the DPQA architecture, atom movement is considered more efficient because it realizes SWAP functionality with substantially higher fidelity and lower coherence-time overhead than its logical, gate-based counterpart.

Key challenges of compilation on the DPQA architecture include:

-

Minimising movement time and distance: Excessive or poorly optimized movements can lead to decoherence and gate errors.

-

Maintaining gate parallelism: Leveraging the ability to execute gates simultaneously during global Rydberg excitation requires precise scheduling of movements.

Addressing these challenges is essential for realising the full potential of NAQC. By optimizing qubit placement and routing strategies, it is possible to achieve high-fidelity circuit execution while minimizing resource overheads.

Compilation procedures in the DPQA architecture

Consider a quantum circuit \(C\) consisting of single- and two-qubit gates that are native to a DPQA processor M. In NAQC, single-qubit gates are implemented independently using Raman laser pulses and are therefore typically excluded from \(C\) when assessing the cost of atom movement. This simplification allows the problem to focus on the native two-qubit gates, which are typically \(CZ\) gates. These \(CZ\) gates are organized into layers, each of which can, in principle, be executed in parallel through global Rydberg excitation.

Initially, each logical qubit in \(C\) is mapped to a physical atom in the DPQA processor M. For each layer of parallel \(CZ\) gates, any pair of interacting qubits must be co-located at the same site (i.e., grid point) during the gate operation and separated afterward. As illustrated in Fig. 2, the execution of any \(CZ\) gate (or several \(CZ\) gates in parallel) involves the following steps:

-

1.

Meet: Move one or both atoms to the same site from their previous positions.

-

2.

Interact: Apply a global Rydberg laser to interact the qubits at the same position, executing the corresponding \(CZ\) gates in parallel.

-

3.

Separate: After the interaction, move the atoms apart so that they occupy different sites.

The execution of each \(CZ\) involves at least two atom moves: a “meet” step and a “separate” step. These processes can often be parallelized across several or all gates within the same layer. The maximum distance moved during these steps determines the optimal distance required. In the DPQA processor M, this maximal distance is at least d in each step, where d is the unit distance of the processor. Consequently, a circuit with S layers of CZ gates requires at least 2S atom moves, covering a total distance of at least 2Sd.

The meet-interact-separate steps for executing a CZ gate in a DPQA processor. In the restore mode, atoms return to their original positions after interaction, while in the swap mode, their positions are exchanged. Offset movements may be required to prevent collisions when two atoms occupy the same site.

We note that the “separate” step is highly flexible, a flexibility that plays a crucial role in this paper. Specifically, we distinguish between two modes of this step: the “swap” mode exchanges the positions of the two interacting atoms, and the “restore” mode, which returns the two interacting atoms to their original positions. See Fig. 2 for illustrations of these modes. The moves in the meet and separate steps are called big moves in this paper, which involve significant atom movement between different grid point. We also note, for interaction purpose, two atoms may locate at each grid point in the same time. To avoid atom collision, we need move one atom a little bit away from the grid point. This kind of offset movements are also required when we, for example, swap the positions of two atoms (see the right of Fig. 2).

Overview of quantum Fourier transform

QFT is a fundamental component of many important quantum algorithms. Efficiently implementing QFT on quantum hardware is crucial for realizing the potential of these algorithms. However, the all-to-all interaction pattern of QFT poses significant challenges, especially in layouts with limited qubit connectivity. In this section, we review the structure of QFT circuits and discuss the optimal transformation strategies for the linear superconducting architecture, which will serve as a foundation for our proposed methods for the DPQA architecture.

Structure of the quantum Fourier transform

For an n-qubit system, the QFT circuit consists of \(n(n-1)/2\) controlled-phase gates, interleaved with single-qubit Hadamard operations. These gates are arranged in a specific pattern that transforms the input state into its transformed state. Figure 3a illustrates a standard QFT circuit with \(n = 5\) qubits.

(a) Standard QFT-5 circuit, with each \(P\) denoting a controlled-phase gate. (b) Layered partition of QFT-5 (with single-qubit gates removed), showing 7 sequential controlled-phase layers. (c) The optimal transformation of QFT-5 on the linear superconducting architecture, with each mapping annotated to reflect the updated qubit arrangement after applying the necessary SWAP gates. (d) Decomposition of a controlled-phase gate into single-qubit gates and \(CZ\) gates..

For circuit transformation purposes, we focus only on two-qubit gates in this paper. By pushing these gates as far forward as possible, the QFT circuit consists of \(2n-3\) layers of two-qubit gates. Figure 3b illustrates that QFT-5 has \(2n-3=7\) two-qubit gate layers.

Maslov’s optimal transformation for the linear superconducting architecture

The QFT-n circuit, having a complete interaction graph, cannot be directly implemented on linear or other practical superconducting processors. In superconducting processors, this necessitates the use of SWAP gates to iteratively remap qubits until all two-qubit gates act on adjacent physical qubits.

For the linear superconducting architecture, Maslov13 discovered an optimal transformation for the QFT-n circuit (see Fig. 3c). This transformation requires \(2n-3\) layers of SWAP gates, resulting in a transformed circuit with O(n) depth. The transformation warrants close examination.

In Maslov’s approach, we consider each layer of two-qubit gates, along with its accompanying SWAP gates, as a single mapping stage (m-stage for short). Each m-stage is associated with a mapping. Let \(\tau _k\) denote the mapping at the k-th m-stage. Initially, \(\tau _0\) maps logical qubit \(q_i\) to physical qubit \(Q_i\). We next provide a characterization for those SWAPs used in each m-stage.

For m-stages \(0\le k\le n-2\), define

For m-stages \(n-1\le k \le 2n-4\), define \(N_k=N_{2n-4-k}\).

The following lemma characterizes the inserted SWAP gates at each m-stage.

Lemma 1

At m-stage k, the two-qubit gates to be executed are \(CP(r_j,s_j)\) for \(j\in N_k\), where \(r_j\) and \(s_j\) are the logical qubits in the QFT- n circuit that are mapped to physical qubits \(Q_j\) and \(Q_{j+1}\), respectively, under the mapping \(\tau _{k}\). Thus, under the mapping \(\tau _{k}\), these two-qubit gates act on physical qubits \(Q_j\) and \(Q_{j+1}\) for \(j\in N_k\). Moreover, SWAP gates are inserted to exchange the states of physical qubits \(Q_j\) and \(Q_{j+1}\) for \(j\in N_k\).

For convenience, for each \(0\le k\le 2n-4\), we write

and call edges in \(E_k\) the relevant edges in the k-th m-stage.

Through the SWAP operations corresponding to those relevant edges, the initial trivial mapping \(\tau _0\) is transformed into the final mapping \(\tau _{2n-3}\), which maps \(q_0, \ldots ,q_{n-1}\) to \(Q_{n-1},\ldots ,Q_0\). An illustration is given in Fig. 3c.

The following lemma demonstrates that the SWAP gates inserted in consecutive m-stages operate on alternating edges in the linear processor.

Lemma 2

For any odd k and any even \(k'\), \(E_k\cap E_{k'}=\varnothing\). In particular, \(E_k \cap E_{k+1}=\varnothing\) for any \(0\le k\le 2n-5\).

The lemma will play an important role in our design of optimal transformation for general DPQA processors.

While Maslov’s transformation is optimal for the linear superconducting architecture, it relies heavily on SWAP gates to facilitate interactions between non-adjacent qubits. In NAQC, however, SWAP gates can be replaced with atom movements, which offer a more flexible and potentially more efficient alternative. This key difference underscores the need for new compilation strategies tailored to the unique capabilities of NAQC platforms.

In the next section, we explore how these capabilities can be leveraged to develop efficient compilation strategies on the DPQA architecture.

Optimal transformations of QFT circuits on the DPQA architecture

In this section, we present optimal compilation strategies for implementing QFT circuits on the DPQA architecture. We begin by estimating the theoretical lower bound on atom movements required for QFT circuits. Next, we introduce an optimal transformation for linear DPQA processors, which serves as the foundation for our approach. Finally, we extend this transformation to 2D grid-like processors, demonstrating how to maintain efficiency while adapting to practical hardware constraints. By leveraging the unique capabilities of the DPQA architecture, such as dynamic qubit reconfigurability, our methods achieve theoretical lower bounds in movement counts while preserving high circuit fidelity.

Replacing SWAP gates with atom movement

On superconducting and FAA architectures, SWAP gates are commonly used to enable interactions between non-adjacent qubits. However, on the DPQA architecture, SWAP gates can be entirely replaced with atom movements, which are more efficient and do not require additional gate operations (cf. Remark 1). This is made possible by the dynamic reconfigurability of qubits on the DPQA architecture, where atoms can be physically moved to facilitate interactions.

Since the \(CZ\) gate is the native two-qubit gate on the DPQA architecture, we first decompose the controlled-phase gates \(CP(\lambda )\) in the QFT circuit into \(CZ\) gates. Recall the following single-qubit gate identities:

Thus, as shown in Fig. 3d , each controlled-phase gate \(CP(\lambda )\) is decomposed into two \(CZ\) gates. Consequently, the QFT-n circuit, which originally consists of \(2n-3\) layers of controlled-phase gates, is transformed into \(2(2n-3)\) layers of \(CZ\) gates.

Recall from Sect. 2.4 that the execution of a \(CZ\) gate in a DPQA processor involves three steps: 1) moving atoms to the same grid point (the meet step), 2) applying a global Rydberg laser to perform the gate (the interact step), and 3) separating the atoms (the separate step). Each execution of \(CZ\) gates thus requires at least two atom movements: one for the meet step and one for the separate step. Importantly, the “separate” step does not require the interacted atoms to be returned to their original positions. Instead, their positions can be exchanged, as illustrated in Fig. 2. Shortly, we will see that this flexibility allows us to simulate SWAP operations without additional overhead, further optimizing the circuit.

For the QFT-n circuit, which has \(2(2n-3)\) layers of \(CZ\) gates, the theoretical lower bound on the total number of atom moves is \(4(2n-3)\). Atom movements can potentially be fully parallelized across gates within the same layer, minimizing the total distance traveled by the atoms. Achieving this bound requires careful scheduling of atom movements to ensure that all gates in a layer are executed with minimal overhead.

Optimal transformation in a linear DPQA processor

In this subsection, we propose an optimal transformation for QFT circuits on a linear layout of the DPQA architecture, which can be viewed as a \(1 \times n\) grid. Each grid point is represented by its coordinate \(P_i \equiv (i, 0)\), and the unit distance between consecutive grid points is d.

The transformation builds on Maslov’s approach for linear superconducting processors, where SWAP gates are inserted to enable interactions between non-adjacent qubits (see Fig. 3c). In DPQA processors, we replace these SWAP gates with atom movements, which are more efficient. Specifically, for each m-stage (mapping stage) in Maslov’s transformation, the layer of controlled-phase gates is replaced with two identical layers of CZ gates We then perform the following steps for each m-stage:

-

a.

First CZ-layer:

-

Move the atoms involved in the gates to the same grid point (meet step).

-

Apply the gates using a global Rydberg laser (interact step).

-

Move the atoms back to their original positions (separate step in restore mode).

-

-

b.

Second CZ-layer:

-

Move the atoms involved in the gates to the same grid point (meet step).

-

Apply the gates using a global Rydberg laser (interact step).

-

Swap the positions of the atoms (separate step in swap mode).

-

This approach ensures that all \(CZ\) gates are executed with minimal atom movements, achieving the theoretical lower bound of \(4(2n-3)d\). The transformation is optimal because it parallelizes movements within each m-stage and minimizes the total distance traveled by the atoms.

More precisely, for edges \(e_j = (j, j+1)\) with \(j \in E_k\) (as defined in (2)), the atom movements are performed as follows: in Step a, we move all smaller-indexed atoms towards the larger-indexed atoms and move them back; in Step b, we move all smaller-indexed atoms towards the large-indexed atoms and swap their positions.

The movement directions are consistent within each batch of atom movements, and each move covers only a unit distance \(d\). This ensures that the total maximal distance traveled by the atoms is \(4(2n-3)d\), which matches the theoretical lower bound. Therefore, the transformation on the linear DPQA architecture is optimal.

As a consequence, we have the following result:

Theorem 1

Let \(M\) be a linear DPQA processor of \(n\) qubits. The transformation described above for QFT-\(n\) is an optimal transformation on \(M\).

To illustrate the transformation, we revisit the QFT-5 circuit.

Example 1

The QFT-5 circuit consists of 7 m-stages and 14 layers of \(CZ\) gates. Initially, the logical qubits \(q_i\) are mapped to the atoms located at the grid point \(P_i = (i, 0)\) for \(0 \le i \le 4\) in the linear DPQA processor. Figure 4 illustrates the mapping stages and movement sequences for QFT-5.

For example, at m-stage 3, the set of edges \(E_3 = \left\{ {(1,2), (3,4)} \right\}\) indicates that atom movements are performed along these edges. Specifically:

-

In the first layer of \(CZ\) gates (Step a), the atoms at \(P_1\) and \(P_3\) are moved (along the same direction), respectively, to \(P_2\) and \(P_4\), the \(CZ\) gates are applied, and the atoms are returned to their original positions.

-

In the second layer of \(CZ\) gates (Step b), the atoms at \(P_1\) and \(P_3\) are moved (along the same direction), respectively, to \(P_2\) and \(P_4\), the \(CZ\) gates are applied, and their positions are swapped.

The red edges in Fig. 4 highlight the atom movements along the edges \(e \in E_k\) for each m-stage \(k\) (where \(0 \le k \le 6\)), demonstrating how the transformation achieves the theoretical lower bound on movement counts.

Mapping stages (m-stages) and movement sequences for QFT-5 in a linear DPQA processor, where the x-axis represents the mapping stage and the y-axis indicates the atom locations in the linear processor. The red edges at each m-stage \(x\) (for \(0 \le x \le 6\)) highlight atom movements along edges \(e \in E_x\).

Optimal transformation on a grid DPQA processor

While the linear layout of the DPQA architecture achieves minimal movement cost, it requires qubits to be arranged in a one-dimensional array, which becomes impractical for large numbers of qubits. To address this, we propose folding the linear layout into a two-dimensional grid while preserving the efficiency of the linear transformation. This is achieved through a technique called zigzag folding, which maps the linear arrangement of qubits onto a grid in a way that maintains adjacency and enables parallel gate execution.

Definition 1

(Zigzag Folding) Let P be a linear DPQA processor of n qubits \(q_0, q_1, \ldots , q_{n-1}\), and let M be a DPQA processor with grid dimensions \(m_1 \times m_2\). A zigzag folding \(\Phi\) of P into M is an injective mapping that assigns a unique grid point \((x_i, y_i)\) to each qubit \(q_i\) such that:

-

Neighboring Placement: \(\Phi (q_i)\) is a neighbor of \(\Phi (q_{i-1})\) in M, meaning \(|x_i - x_{i-1}| + |y_i - y_{i-1}| = 1\).

-

Alternating Direction: If \(q_i\) is placed horizontally relative to \(q_{i-1}\), then \(q_{i+1}\) (if \(i < n-1\)) is placed vertically relative to \(q_i\), and vice versa.

A zigzag folding ensures that neighboring qubits in the linear arrangement remain adjacent on the grid, enabling efficient gate execution. By Lemma 2, the gate operations and atom movements in each m-stage correspond to either horizontal or vertical edges in the zigzag folding, allowing for parallel execution.

Theorem 2

Let \(\Phi\) be a zigzag folding of a linear DPQA processor of n qubits into a grid DPQA processor M. Then QFT- n has an optimal transformation on M as follows:

-

1.

Initially, map each \(q_i\)to \(\Phi (q_i)\).

-

2.

For each m-stage k, let \(E_k\)be the set of relevant edges as specified in (2).If the edges in \(E_k\)are horizontal (vertical, resp.):

-

For the first layer of CZ gates in the m-stage, move all left (lower, resp.) atoms rightward (upward, resp.), execute the gates using a global Rydberg laser, and then separate the atoms by moving them back.

-

For the second layer of CZ gates in the m-stage, move all left (lower, resp.) atoms rightward (upward, resp.), execute the gates, and then separate the atoms by exchanging their positions.

-

Proof

Without loss of generality, assume that \(q_1\) is placed as the right neighbor of \(q_0\) in the zigzag folding \(\Phi\). By the definition of zigzag folding, the placement of qubits alternates between horizontal and vertical directions. Consequently:

-

For even \(k\), all edges in \(E_k\) are horizontal.

-

For odd \(k\), all edges in \(E_k\) are vertical.

For each m-stage \(k\), the transformation involves four batches of atom movements:

-

Two batches for the first layer of \(CZ\) gates (Step a).

-

Two batches for the second layer of \(CZ\) gates (Step b).

Since all movements within a batch occur in the same direction (either horizontal or vertical), they can be performed in parallel. Furthermore, each movement covers a unit distance \(d\), ensuring that the total distance traveled by the atoms is minimized.

The maximal movement distance for the entire transformation is \(4(2n-3)d\), which matches the theoretical lower bound. This is achieved because:

-

Each of the \(2(2n-3)\) layers of \(CZ\) gates requires two atom movements (one for the meet step and one for the separate step).

-

Each movement covers a unit distance \(d\).

-

Movements are parallelized within each m-stage, ensuring no unnecessary overhead.

Neglecting offset movements, the transformation is optimal in terms of both the big-move count and the total distance traveled. \(\square\)

This transformation achieves the same theoretical lower bound on movement counts as linear processors while adapting to the practical constraints of 2D grid processors.

Consider, for example, the two zigzag embeddings shown in Fig. 5a for a linear processor of five qubits. At m-stage 3, the set of relevant edges \(E_3 = \left\{ {(1,2), (3,4)} \right\}\) defines the required interactions between qubits. In the left zigzag folding, both edges are horizontal, while in the right zigzag folding, both are vertical. This alignment ensures that the atom movements in m-stage 3 can be performed in parallel in both foldings. This parallelization of atom movements within each m-stage ensures that the transformation achieves the theoretical lower bound on movement counts while maintaining high circuit fidelity.

Space-efficient zigzag foldings

While the zigzag folding approach guarantees optimal transformations for QFT circuits on grid processors, it is also important to ensure that the folding is space-efficient. Specifically, we aim to implement QFT-n compactly on a \((w \times w)\)-grid with \(w = O(\sqrt{n})\). In this subsection, we demonstrate how to construct such space-efficient zigzag foldings.

Construction of space-efficient zigzag foldings

(a) Two zigzag foldings of the same five-qubit linear DPQA processor into a \(3 \times 3\) grid layout. At m-stage 3, the relevant edges \(\{(1,2),(3,4)\}\) run horizontally in the left folding and vertically in the right one. In both cases, movements along these edges can occur in parallel, preserving the optimal total big moves. (b) Illustrates \(\Phi _{1}\), while (c) depicts \(\Phi _{2}\). (d) Presents the zigzag path \(\Phi _{5}\) within a \(10 \times 10\) grid, where the red and blue boxes highlight the configurations of \(\Phi _{3}\) and \(\Phi _{1}\), respectively. Similarly, (e) showcases the zigzag path \(\Phi _{6}\) in a \(12 \times 12\) grid, with the red and blue boxes highlighting the configurations of \(\Phi _{4}\) and \(\Phi _{2}\), respectively. The unvisited (or “wasted”) grid points are highlighted.

For each integer w, we construct a zigzag folding \(\Phi _w\) in a \((2w \times 2w)\)-grid. The construction proceeds as follows:

-

For \(w = 1\), the zigzag folding \(\Phi _1\) occupies 4 grid points in a \(2 \times 2\) grid. The path starts at \(P_0 = (0, 0)\), moves up to \(P_1 = (0, 1)\), then right to \(P_2 = (1, 1)\), and finally down to \(P_3 = (1, 0)\). See Fig. 5c for an illustration.

-

For \(w = 2\), the zigzag folding \(\Phi _2\) occupies 12 grid points in a \(4 \times 4\) grid. See Fig. 5c for an illustration, where only two grid points are wasted.

-

For \(w \ge 3\), the zigzag folding \(\Phi _w\) is constructed by extending \(\Phi _{w-2}\) from a \((2w-4) \times (2w-4)\) grid to a \((2w \times 2w)\) grid. The path alternates between horizontal and vertical movements, ensuring that neighboring qubits in the linear arrangement remain adjacent on the grid. See Fig. 5d,e for illustrations of \(\Phi _5\) and \(\Phi _6\), respectively.

We note that the location does not matter and a configuration can be translated or properly rotated in the plane.

Space efficiency analysis

Let \(\phi (m)\) denote the number of empty grid points (i.e., grid points not visited by the path \(\Phi _m\)) in a \((2m \times 2m)\) grid. We observe that:

-

\(\phi (1) = 0\) (all grid points are occupied).

-

\(\phi (2) = 2\) (two grid points are empty).

-

For \(m \ge 1\), \(\phi (m+2) = \phi (m) + 4\).

By induction, it follows that \(\phi (m) \le 2m\). This implies that the number of wasted grid points grows linearly with m, while the total number of grid points grows quadratically. As a result, the space efficiency of the zigzag folding improves as n increases.

Lemma 3

For any n, we can construct a zigzag folding path of n atoms in a \((2m+2) \times (2m+2)\) grid such that the spatial efficiency approaches 1 as n increases, where \(m =O(\sqrt{n})\).

Proof

Let \(m = \lceil \sqrt{n}/2 \rceil\). The zigzag folding \(\Phi _{m+1}\) in a \((2m+2) \times (2m+2)\) grid has at most \(2m+2\) wasted grid points. Since \(4m^2 \ge n\), the total number of grid points is at least n. The space efficiency is given by:

which approaches 1 as n increases. \(\square\)

Practical implications

By compactly folding the linear processor into a grid, we adapt the efficient movement strategies for linear DPQA layouts to a practical two-dimensional layout suitable for the DPQA architecture. This ensures that the transformation remains optimal in terms of movement counts while minimizing the physical space required for qubit placement.

Evaluation and comparison

In this section, we evaluate the performance of our proposed methods (called Linear and Zigzag Paths, respectively) for transforming QFT circuits on the DPQA architecture. We compare our approaches with two state-of-the-art DPQA compilers, viz. Enola22 and Atomique23, focusing on movement counts, cumulative movement distances, and overall fidelity. Our evaluation aims to demonstrate the effectiveness of our methods in minimizing resource overheads while maintaining high-fidelity quantum operations. In addition, we also compare our approaches with DasAtom34, a state-of-the-art NAQC compiler for non-DPQA architectures, to unveil the significant differences among NAQC architectures.

We implement Linear and Zigzag Paths in Python and employ Enola’s CodeGen framework22 to generate gate execution and schedule movements. All experiments were conducted on a system running Ubuntu 22.04, equipped with a 40-core Intel Xeon Gold 5215 processor at 2.50 GHz and 512 GB of RAM.

The compared state-of-the-art compilers

We compare our methods with the following state-of-the-art compilers for NAQC:

-

Enola22: A leading compiler for the DPQA architecture. Enola dynamically reconfigures qubit placements between consecutive Rydberg stages and schedules circuits using the minimal number of global-excitation stages, where all \(CZ\) gates in a stage are executed in parallel. This strategy minimizes the number of Rydberg stages but requires complete atom reconfiguration after each stage, resulting in a large number of atom movements and long cumulative movement distances. [GitHub Repository: https://github.com/UCLA-VAST/Enola]

-

Atomique23: A leading compiler for the DPQA architecture that uses multiple AOD arrays to enable parallel atom movements and enhance movement efficiency. By mapping qubits across arrays and scheduling gate execution to maximize inter-array interactions, Atomique can eliminate many atom transfers. Nevertheless, this approach comes with trade-offs: because qubits that end up in the same array must often interact via SWAP gates, Atomique incurs extra SWAP overhead; additionally, although atom transfers are largely avoided, the increased number of Rydberg stages and resultant decreased parallelism limit its overall fidelity advantage. Our setup for Atomique uses two AOD arrays. [Zenodo record: https://zenodo.org/records/10995324]

-

DasAtom34: A state-of-the-art NAQC compiler in which \(CZ\) gates are scheduled individually using locally addressable Rydberg lasers. DasAtom leverages long-range interactions to dramatically reduce atom movement, achieving significantly improved overall fidelity compared to move- or SWAP-based compilers. However, this performance depends on a hardware architecture that supports high-fidelity long-range coupling and fine-grained laser control—features that are not part of the DPQA architecture. As a result, while DasAtom excels under its target hardware model, its assumptions diverge from DPQA constraints, limiting direct applicability in the DPQA compilation context. Our setup for DasAtom assumes an atom distance of 3 \(\mu\)m and an interaction radius of 6 \(\mu\)m. [GitHub Repository: https://github.com/Huangyunqi/DasAtom]

Key performance metrics

We evaluate these methods based on four critical metrics:

-

(1)

big-move counts: The number of significant positional shifts of qubits during circuit execution. Minimizing this reduces operational overhead and potential errors.

-

(2)

Cumulative Movement Distances: The total distance qubits travel, including both big moves and short offsets executed to resolve placement conflicts (i.e., preventing qubits from occupying the same physical location). Compilation Time: The total end-to-end wall-clock time of the compilation process, including front-end parsing, qubit placement, gate scheduling and routing, and code generation.

-

(3)

Overall Fidelity: Calculated based on errors from two-qubit gate error, global Rydberg excitation error, atom transfer error, and decoherence error, following the fidelity model outlined in22:

$$\begin{aligned} f = \;\underbrace{\left( f_{2}\right) ^{g_{2}}}_{\text {two-qubit gate}} \times \underbrace{ \left( f_{\text {exc}}\right) ^{|Q|S - 2g_{2}}}_{\text {Rydberg excitation}} \;\times \; \underbrace{\left( f_{\text {trans}}\right) ^{N_{\text {trans}}}}_{\text {atom transfer}} \;\times \; \underbrace{\prod _{q \in Q} \left( 1 - \frac{T_q}{T_2}\right) }_{\text {decoherence}}, \end{aligned}$$(3)where:

-

\(f_{2}\) is the two-qubit gate fidelity.

-

\(g_2\) is the number of \(CZ\) gates in the compiled circuit. Atomique may insert SWAP gates and each SWAP gate incurs three CZ gates.

-

Q is the qubit set in the compiled circuit. Atomique may use ancilla qubits.

-

S is the number of Rydberg stages. Atomique may use more stages than the other compilers, which all use a minimal number of stages.

-

\(f_{\text {exc}}\) is the fidelity of an isolated (i.e., not interacting with another qubit) qubit in a Rydberg stage. For DasAtom, \(f_{\text {exc}}=1\) as it employs individually addressable Rydberg lasers.

-

\(f_{\text {trans}}\) measures fidelity losses from atom transfers.

-

\(N_{\text {trans}}\) is the number of atom transfers. Atomique uses no atom transfers.

-

\(T_q\) is the idling time for qubit q.

-

\(T_2\) is the coherence time.

-

Table 1 lists the key parameters adopted in our experiments, which are also assumed in22.

Theoretical Lower Bounds (TLBs) for movement counts serve as a baseline metric for optimal performance and are calculated as \(4(2n-3)\). Note that the “meet-interact-separate” action of the last CZ layer (corresponding to the last SWAP gate in Fig. 3c) does not need to swap the two atoms in practice, which could reduce the TLB by 1.

Evaluations on QFT circuits

We focus on QFT circuits as the primary workload, which exhibit dense connectivity. Later, we extend the analysis to sparser circuits (QAOA MaxCut).

Comparison of different compilation methods for QFT circuits as a function of qubit count \(n\). Theoretical lower bounds (TLBs) for movement count and distance are given by \(4(2n-3)\) and \(4(2n-3)d\), respectively. (a) Big-move counts. (b) Cumulative atom-movement distances. (c) Total circuit fidelity. (d) Total compilation time.

Big-move counts

Figure 6a illustrates the big-move counts for each compiler on QFT circuits of increasing qubit sizes.

-

Linear & Zigzag Paths achieve TLB for big-move counts, demonstrating their effectiveness in minimizing major atom movements.

-

Enola’s compilation strategy results in exponentially higher big-move counts than the other methods, due to its necessity to update atom placement after each Rydberg stage.

-

Atomique uses SWAP gates to reduce atom movements, but its overall big-move counts are higher than Linear and Zigzag Paths when \(n\ge 15\).

-

DasAtom achieves fewer big moves than the TLB by leveraging long-range interactions, which eliminate the need for certain atom movements. This is contingent upon the processor supporting individually addressable Rydberg lasers.

Cumulative movement distances

The Cumulative Movement Distance metric quantifies the total distance travelled by atoms during the execution of QFT circuits. Figure 6b illustrates the cumulative movement distances, measured in grid units, for each method as a function of the number of qubits. Notably, each big move in the TLB covers a unit distance. In our methods, big moves also approximates a unit distance, accounting for offset moves. However, in the compared compilers, a single big move may cover much larger distance. It is worth stressing that DasAtom uses a much smaller unit distance (\(3\mu\)m instead of \(15\mu\)m).

-

Linear & Zigzag Paths maintain minimal cumulative movement distances, closely approximating the TLB. While generally efficient, the Zigzag path shows a slight increase in cumulative movement distance as the qubit count grows, due to the need for additional offsets in the grid layout.

-

Enola exhibits the highest cumulative movement distances among all methods, like big-move counts.

-

Atomique demonstrates efficiency for smaller circuits (less than 10 qubits) but experiences an exponential decrease in performance with increasing qubit count.

-

DasAtom achieves moderate cumulative movement distances and outperforms TLB for QFT circuits with up to approximately 20 qubits.

Compilation time

Figure 6d illustrates the compilation time of different compilers as a function of the qubit number in QFT circuits. The results show that both the Linear and Zigzag Path strategies exhibit excellent scalability, with compilation time increasing smoothly and remaining below \(10\,\textrm{s}\) even for 50-qubit circuits. In contrast, Enola exhibits an exponential growth in runtime, exceeding \(10^{4}\,\textrm{s}\) for large circuits. DasAtom and Atomique achieve moderate performance but still incur noticeably higher compilation overhead compared to our methods. These results demonstrate that the proposed path-based strategies significantly enhance compilation efficiency while maintaining stable performance as the qubit number increases.

Overall fidelity analysis

Figure 6c compares the overall fidelity achieved by each method, where the TLB is calculated based on four atom transfers per \(CZ\) gate.

-

Linear & Zigzag Paths achieve the highest fidelity, as their movement efficiency minimizes errors from atom transfers and decoherence.

-

Enola’s methods show exponentially lower fidelity, reflecting their higher movement counts and distances.

-

Atomique experiences fidelity degradation as circuit size increases, primarily due to its reliance on SWAP gates and ancilla qubits.

-

DasAtom achieves higher overall fidelity than the TLB by leveraging individually addressable Rydberg lasers and long-range interactions. Since it employs local two-qubit operations without requiring global Rydberg excitation, it avoids global Rydberg excitation error. Effectively, this is equivalent to setting \(f_\text {exc}=1\) for DasAtom in Eq. (3).

Quantifying Fidelity Gaps via Eq. (3): Table 2 highlights the stark fidelity gaps in larger QFT circuits. For \(n=30\), Enola’s fidelity is more than \(180\times\) lower than Linear Path, while Atomique’s is over \(10^{18}\times\) lower. At \(n=50\), these gaps widen dramatically to factors of \(10^{15}\) and \(10^{94}\), respectively, emphasizing the critical role of movement minimization in large-scale circuits.

Meanwhile, the table suggests that with individually addressable Rydberg lasers, DasAtom’s fidelity could surpass the TLB by more than \(64\times\) for QFT-30 and \(10^6\times\) for QFT-50. This advantage persists even when excitation error is ignored for the TLB, where DasAtom’s fidelity remains nearly \(10\times\) higher for QFT-30 and over \(200\times\) higher for QFT-50. This improvement stems from DasAtom’s use of long-range interactions and local Rydberg excitation. However, we note that current state-of-the-art NAQC with individually addressed Rydberg lasers faces limitations in two-qubit gate fidelity28.

Finally, the table reveals that Enola and Atomique exhibit different performance behaviours depending on whether \(f_\text {exc}=0.9975\) or \(f_\text {exc}=1\). In the first case, Enola outperforms Atomique by factors of \(10^{16}\times\) for QFT-30 and \(10^{78}\times\) for QFT-50. However, when \(f_\text {exc}=1\), Atomique surpasses Enola by \(18.9\times\) for QFT-30 and \(10^9\times\) for QFT-50, which is consistent with the experimental findings reported in34.

Remark 2

Linear and Zigzag Path strategies, as well as Enola, share the same numbers of two-qubit gates, Rydberg stages, and atom transfers as the theoretical lower bound (TLB). Consequently, the first three terms in Eq. (3) are identical for these compilers, and their overall fidelities are primarily determined by big-move counts and cumulative movement distances. As shown in Fig. 6a,b, and Table 2, Enola incurs exponentially higher big-move counts and movement distances because it performs complete atom reconfiguration between consecutive Rydberg stages. This design minimizes the number of Rydberg stages but results in extensive atom movement.

Atomique, in contrast, employs multiple AOD arrays and SWAP operations to reduce physical atom movements. While this approach effectively lowers the big-move count compared to Enola, it requires substantially more Rydberg stages, meaning that fewer \(CZ\) gates can be executed in parallel during each stage. Although the use of multiple AOD arrays eliminates the need for atom transfers, under the high atom-transfer fidelity assumption (\(f_\text {trans}=99.9\%\)), this advantage has limited influence on the overall circuit fidelity.

Distinct from these DPQA-based compilers, DasAtom targets a different NAQC architecture featuring individually addressable Rydberg lasers and long-range interactions. These hardware capabilities enable it to achieve lower big-move counts than the TLB and comparable cumulative movement distances. However, its performance depends on hardware assumptions that extend beyond the DPQA architecture, and thus its results are not directly comparable to DPQA compilers.

Extension to QAOA circuits

While the QFT circuit is characterized by a fully connected interaction graph, many practical quantum circuits do not require full connectivity. To evaluate the adaptability of our methods, we extend our analysis to MaxCut QAOA circuits26 with reduced connectivity.

Procedure for generating random MaxCut QAOA circuits

Let \(\theta \in [0, 100]\) denote the edge retention percentage, a parameter controlling the density of qubit interactions in randomly generated MaxCut QAOA circuits. To construct a random \(n\)-qubit MaxCut QAOA circuit \(C\) with edge retention percentage \(\theta\), we proceed as follows:

-

1.

Initialization: Define a complete graph \(G = (V, E)\), where \(V = \{0, 1, \dots , n-1\}\) represents the qubits and \(E = \{(i, j) \mid 0 \le i< j < n\}\) is the set of edges connecting all qubit pairs.

-

2.

Edge Sampling: For each edge \((i, j) \in E\), include it in a subset \(E_\theta \subseteq E\) with probability \(\theta \%\). This yields a random subgraph representing the retained interactions. Note that \(E_\theta\) may not contain exactly \(|E| \times \theta \%\) edges, but this value holds in expectation.

-

3.

Insertion of CZ Gates: Initialize an empty circuit \(C\). For each edge \((i, j) \in E_\theta\), insert a \(CZ(i, j)\) gate into \(C\).

This procedure systematically generates random MaxCut QAOA circuits whose \(CZ\)-gate density is determined by the parameter \(\theta\). The randomness in edge selection enables exploration of circuit performance across different levels of connectivity and sparsity.

To compile any such random circuit \(C\), we first consider the n-qubit circuit \(C_{QFT}\), which is a simplified version of the QFT-n circuit (cf. Fig. 3b) obtained by replacing all \(CP\) gates directly with \(CZ\) gates. Our Linear and Zigzag Path strategies can be directly applied to \(C_{QFT}\). To adapt these methods for C, we exploit the fact that the order of \(CZ\) gates in C is unimportant. We arrange the CZ gates of C into layers matching those of \(C_\text {QFT}\), though some \(CZ\) gates potentially missing in certain layers. The compilation of \(C\) then proceeds by simulating the compilation of \(C_\text {QFT}\), but with a modified meet-interact-swap operation. Specifically, for each m-stage k: (1) we apply the meet and interact steps to the CZ gates in \(C_k\) (the subset of CZ gates in C that appear in the k-th m-stage of \(C_\text {QFT}\), denoted by \(C'_k\)); (2) we apply the meet step to the CZ gates present in the \(C'_k\) but not in \(C_k\); and (3) we perform the swap step for all CZ gates in \(C'_k\). This effectively splits each parallel atom “meet” move from the \(C_\text {QFT}\) compilation into two “meet” moves for C, ensuring consistent qubit mapping transitions with QFT-n (cf. Fig. 4).

As summarized in Fig. 7, we evaluate the proposed strategies against Enola on random MaxCut QAOA circuits. Figure 7a shows the total circuit fidelity as a function of the edge-retention percentage \(\theta\). When \(\theta \ge 70\%\), our methods achieve higher total fidelity than Enola, even though Enola also leverages gate commutativity. This advantage arises from the reduced atom movements and simplified routing in our strategies. As shown in Fig. 7b, the Linear and Zigzag Path strategies yield identical big-move counts, resulting in overlapping curves. The cumulative movement distances in Fig. 7c remain nearly constant across varying \(\theta\), whereas Enola shows a roughly linear decrease as the circuit connectivity becomes sparser. Finally, Fig. 7d demonstrates that the compilation time of our methods is almost constant and one to two orders of magnitude faster than Enola, highlighting their superior scalability and efficiency.

Performance of different compilation strategies for random MaxCut QAOA circuits as a function of the edge-retention percentage \(\theta\). For each value of \(\theta\), ten random circuit instances were generated and evaluated; reported values are averaged over these instances. (a) Total circuit fidelity. (b) Big-move counts. The Linear and Zigzag Path strategies yield identical results, and their curves completely overlap. (c) Cumulative atom-movement distances. (d) Compilation time.

Conclusion

This work introduced optimal compilation strategies for QFT circuits on the DPQA architecture–currently the most prominent platform for neutral-atom quantum computing (NAQC). The proposed Linear and Zigzag Path strategies achieve the theoretical lower bounds in atom-movement counts while maintaining high circuit fidelity. Comprehensive evaluations demonstrate that these methods exponentially outperform state-of-the-art DPQA compilers, including Enola and Atomique, in both movement efficiency and total fidelity. This exponential fidelity advantage underscores the crucial role of minimizing atom movements and optimizing qubit routing to preserve coherence and scalability in DPQA processors. In addition, our Path strategies can serve as benchmark compilers for evaluating future DPQA compilation frameworks, providing a concrete reference for assessing movement efficiency and fidelity trade-offs.

While initially designed for structured circuits such as QFT, our Path strategies extend naturally to more general quantum circuits. In particular, they can efficiently handle dense circuits like QAOA and variational quantum algorithms (VQAs), where the execution order of two-qubit \(CZ\) gates is flexible. For these applications, our movement-aware routing approach offers a practical pathway toward high-fidelity execution on the DPQA architecture.

Moreover, comparative evaluations against DasAtom highlight the inherent limitations of the current DPQA architecture. DasAtom’s ability to surpass even theoretical lower bounds indicates that architectural advances—such as individually addressable Rydberg lasers or zoned architectures32—are essential to fully exploit the potential of NAQC. We hope these findings encourage experimental researchers to explore novel architectural designs that complement compiler-level innovations.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during this study are available in the repository on GitHub: https://github.com/gcc-bug/qft_atom. The final processed data used in this study are included in the data directory.

References

Shor, P. W. Algorithms for quantum computation: Discrete logarithms and factoring. Proceedings - Annual IEEE Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science, FOCS. https://doi.org/10.1109/SFCS.1994.365700 (1994).

Grover, L. K. A fast quantum mechanical algorithm for database search. In Proceedings of the Twenty-Eighth Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing, 212–219 (1996).

Peruzzo, A. et al. A variational eigenvalue solver on a photonic quantum processor. Nat. Commun. 5, 1–7 (2014).

Schuld, M., Sinayskiy, I. & Petruccione, F. An introduction to quantum machine learning. Contemp. Phys. 56, 172–185 (2015).

Arute, F. et al. Quantum supremacy using a programmable superconducting processor. Nature 574, 505–510 (2019).

Henriet, L. et al. Quantum computing with neutral atoms. Quantum 4, 327 (2020).

Bluvstein, D. et al. A quantum processor based on coherent transport of entangled atom arrays. Nature 604, 451–456. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04592-6 (2022).

Radnaev, A. G. et al. A universal neutral-atom quantum computer with individual optical addressing and non-destructive readout (2024). arXiv:2408.08288.

Kitaev, A. Y. Quantum measurements and the abelian stabilizer problem (1995). quant-ph/9511026.

Lloyd, S. Universal quantum simulators. Science 273, 1073–1078. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.273.5278.1073 (1996).

Brassard, G., Høyer, P., Mosca, M. & Tapp, A. Quantum Amplitude Amplification and Estimation. https://doi.org/10.1090/conm/305/05215 (2002).

Harrow, A. W., Hassidim, A. & Lloyd, S. Quantum algorithm for linear systems of equations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.103.150502 (2009).

Maslov, D. Linear depth stabilizer and quantum Fourier transformation circuits with no auxiliary qubits in finite-neighbor quantum architectures. Phys. Rev. A 76. https://doi.org/10.1103/physreva.76.052310 (2007).

Takahashi, Y., Kunihiro, N. & Ohta, K. The quantum Fourier transform on a linear nearest neighbor architecture. Quantum Inf. Comput. 7, 383–391 (2007).

Nam, Y., Su, Y. & Maslov, D. Approximate quantum Fourier transform with o (n log (n)) t gates. NPJ Quantum Inf. 6, 26 (2020).

Zhang, C. et al. Time-optimal qubit mapping. In Proceedings of the 26th ACM International Conference on Architectural Support for Programming Languages and Operating Systems, ASPLOS ’21, 360–374, https://doi.org/10.1145/3445814.3446706 (Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 2021).

Jin, Y. et al. Quantum fourier transformation circuits compilation. arXiv:2312.16114.

Park, B. & Ahn, D. Reducing CNOT count in quantum Fourier transform for the linear nearest-neighbor architecture. Sci. Rep. 13 (2023).

Gao, X., Jin, Y., Guo, M., Chen, H. & Zhang, E. Z. Linear depth QFT over IBM heavy-hex architecture. arXiv:2402.09705.

Bäumer, E., Tripathi, V., Seif, A., Lidar, D. & Wang, D. S. Quantum Fourier transform using dynamic circuits. Phys. Rev. Lett. 133, 150602 (2024).

Schmid, L. et al. Computational capabilities and compiler development for neutral atom quantum processors-connecting tool developers and hardware experts. Quantum Sci. Technol. 9, 033001. https://doi.org/10.1088/2058-9565/ad33ac (2024).

Tan, D. B., Lin, W.-H. & Cong, J. Compilation for dynamically field-programmable qubit arrays with efficient and provably near-optimal scheduling. https://doi.org/10.1145/3658617.3697778 (2024). arXiv:2405.15095.

Wang, H. et al. Atomique: A quantum compiler for reconfigurable neutral atom arrays. In 2024 ACM/IEEE 51st Annual International Symposium on Computer Architecture (ISCA), 293–309, https://doi.org/10.1109/ISCA59077.2024.00030 (IEEE Computer Society, Los Alamitos, CA, USA, 2024).

Wang, H. et al. Q-pilot: Field programmable qubit array compilation with flying ancillas. In Proceedings of the 61st ACM/IEEE Design Automation Conference (DAC) (ACM/IEEE, 2024).

Huang, H.-Y., Kueng, R. & Preskill, J. Predicting many properties of a quantum system from very few measurements. Nat. Phys. 16, 1050–1057 (2020).

Farhi, E., Goldstone, J. & Gutmann, S. A quantum approximate optimization algorithm (2014). arXiv:1411.4028.

Beugnon, J. et al. Two-dimensional transport and transfer of a single atomic qubit in optical tweezers. Nat. Phys. 3, 696–699 (2007).

Graham, T. et al. Multi-qubit entanglement and algorithms on a neutral-atom quantum computer. Nature 604, 457–462 (2022).

Levine, H. et al. Dispersive optical systems for scalable raman driving of hyperfine qubits. Phys. Rev. A 105. https://doi.org/10.1103/physreva.105.032618 (2022).

Evered, S. J. et al. High-fidelity parallel entangling gates on a neutral-atom quantum computer. Nature 622, 268–272 (2023).

Levine, H. et al. Parallel implementation of high-fidelity multiqubit gates with neutral atoms. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 170503 (2019).

Bluvstein, D. et al. Logical quantum processor based on reconfigurable atom arrays. Nature 626, 58–65. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06927-3 (2024).

Reichardt, B. W. et al. Logical computation demonstrated with a neutral atom quantum processor (2024). arXiv:2411.11822.

Huang, Y., Gao, D., Ying, S. & Li, S. Dasatom: A divide-and-shuttle atom approach to quantum circuit transformation. IEEE Trans. Comput. Aided Des. Integr. Circuits Syst. 1–1. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCAD.2025.3532818 (2025).

Funding

Work partially supported by the Quantum Science and Technology–National Science and Technology Major Project (2024ZD0300502), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (12471437), and the Beijing Nova Program (20240484652)..

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SL conceived the initial research question and proposed the core ideas. DG developed the methodology, performed the experiments, and drafted the manuscript. YL and SY contributed to discussions and all authors contributed to manuscript revisions.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gao, D., Li, Y., Ying, S. et al. Optimal compilation strategies for QFT circuits in neutral-atom quantum computing. Sci Rep 16, 2719 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32572-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32572-z