Abstract

Age-related obesity is a growing healthcare burden. Effectiveness of body weight reducing mediators changes with aging and these alterations may contribute to aging obesity. Our previous results suggested a potential contributions of urocortin 2 (UCN2) to aging obesity and age-related cachexia. Lifestyle interventions, such as caloric restriction or physical activity can improve body weight and body composition. Previous observations suggest that lifestyle interventions may also influence age-associated regulatory changes in energy balance. We aimed to study the effects of a 12-week treadmill training or caloric restriction on the central hypermetabolic responsiveness to UCN2 in middle-aged 6- and 12-month old male Wistar rats. Interventions started at age 3- or 9-months. Following the interventions, acute hypermetabolic/hyperthermic responses were tested upon intracerebroventricular injections of UCN2. Both the training and the caloric restriction lead to weight loss and training led to favorable body composition changes. UCN2-induced hypermetabolism/hyperthermia was diminished by both interventions in both age-groups. The Ucn2 mRNA expression detected by RNAscope in situ hybridization in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus was also decreased by both interventions. UCN2-induced hypermetabolism/hyperthermia in the trained and caloric restricted middle-aged groups resembled those of young adult 3-month rats. Lifestyle interventions appear to delay age-related regulatory alterations of energy balance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Obesity is a growing burden to the healthcare system worldwide. In 2022 16% of the population was obese and about 46% overweight1. Especially middle-aged and aging populations show high prevalence2. Obesity is a major risk factor for diabetes mellitus, fatty liver disease, cardiovascular diseases such as hypertension, myocardial infarction and stroke, cancer, osteoporosis, osteoarthrosis, Alzheimer’s disease, depression, etc., and it decreases the quality of life3. Moreover, there are similarities between obesity and aging, such as higher glucose and insulin levels, decreased reproduction, shortening of telomers in the liver, higher mammalian target for rapamycin (mTOR) acitivity in both conditions4. Additionally, obesity accelerates aging4. Therefore, the prevention of obesity should be very important in the next few decades.

Previous studies indicate that age-related alterations in the central regulation of energy balance involving leptin, neuropeptide Y, melanocortins and corticotropins among other peptide mediators also contribute to the development of aging obesity5,6,7,8,9. The corticotropin family, via activation of its 2 types of receptors, can regulate the activation of the pituitary-adrenal axis, increase the heart rate and the body temperature. It also affects the anxiogenic and depressive behavior10. Anorexigenic, heart rate increasing effects are mediated by type 2 receptors of corticotropin releasing factor (CRF2R)10. A member of the corticotropin family, urocortin 2 (UCN2) is known by its selective binding to the CRF2R. Our previous study demonstrated characteristic age-dependent changes in the effects of UCN2 that may have a role in the development of middle-aged obesity9. Our findings showed that the anorexigenic effects of UCN2 along with the hypothalamic Ucn2 mRNA expression in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus (PVN) decreased in the middle-aged group9.

Lifestyle factors, such as overeating, lack of physical activity and low energy expenditure also have an effect on the development of obesity3. Previous studies showed that physical activity, e.g. treadmill training can influence the release of different mediators. Treadmill training decreased the secretion of leptin11. Moreover, corticotropin releasing factor (CRF) another member of the corticotropin family might have a role in the development of training-induced anorexia12. Other studies reported that caloric restriction (CR) could influence the age-related changes in the anorexigenic and hypermetabolic effects of leptin5. Both physical training and caloric restriction may influence body composition in an advantageous way4,13,14.

There is big body of data demonstrating that CR delays aging and even increases the life span4,15. Some evidence also indicate that treadmill training may improve the mitochondrial content thus delaying aging even if it did not prolong lifespan in rodents16.

Based on previous research, it is known that various peptide mediators play an important role in the regulation of energy balance. It has been also demonstrated that age-related changes in the effects of such peptide mediators promote age-associated obesity5,9. Previously mentioned animal studies showed that long-term caloric restriction and treadmill training might delay aging4,15,16. We hypothesized that lifestyle interventions that reduce obesity such as treadmill training and caloric restriction may improve disadvantageous age-associated alteration in the central regulation of energy balance. They also might have a role on the effects of regulatory peptides, such as UCN2.

Our study is the first to test the effects of transient 12-week interventions of caloric restriction and treadmill training in middle-aged rats on the responsiveness to UCN2 with regard to energy balance.

Results

Effects of lifestyle interventions on food intake, body weight and body composition

In the CR groups daily food intake (FI) was 16 g standard chow per day. This limited FI was significantly lower than that of the ad libitum fed (NF) and treadmill training (TR) groups. In the younger 6-month rats one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test demonstrated these differences (CR6 vs. NF6 and TR6: p < 0.001). Among the older 12-month-old rats a similar statistical difference was shown (one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test, CR12 vs. NF12 and TR12: p < 0.001). Whereas the mean FI of the NF6 and TR6 groups remained similar, in the older age-group, chow consumption of TR12 rats became lower than that of NF12 during the course of the 12-week training (one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test, p = 0.007) (Fig. 1, Supplementary Table 8).

Daily food intake (FI) values of ad libitum fed sedentary (NF), treadmill trained ad libitum fed (TR) and caloric restricted sedentary (CR) middle-aged male Wistar rats during a 12-week intervention or observation period starting at 9-months- and ending at 12-months of age. * indicates a significant difference between the CR12 and the NF12 or TR12 animals, # indicates a significant difference between the TR12 and NF12 groups, shown by repeated-measures ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test. Number of animals per group: CR12 n = 18, NF12 n = 16, TR12 n = 20.

With regard to body weights (BW), the initial mean values did not differ either in the 3-month-old or the 9-month-old groups (Supplementary Table 1.). During the 12-week interventions, both the caloric restriction and the training induced weight loss in the CR6, CR12 and TR12 groups (one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test, p < 0.001) (Supplementary Table 1.).

The 12–week treadmill training significantly decreased the post mortem perirenal fat indicator in the TR12 group compared to that of the NF12 controls (NF12: 1.08 ± 0.07, TR12: 0.69 ± 0.06, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test: p = 0.019). In addition, the training increased the value of the post mortem relative muscle indicator as compared with that of the NF12 group (NF12: 0.51 ± 0.04, TR12: 0.72 ± 0.0.4, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test: p < 0.001). The 12-week caloric restriction (CR12) failed to change the perirenal fat indicator, but increased the relative muscle indicator significantly (NF12: 0.51 ± 0.04, CR12: 0.91 ± 0.02, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test: for retroperitoneal fat p = 0.23, for muscles p < 0.001). By the end of the intervention there was a significant difference between the mean BW values of the TR12 and NF12 groups (NF12: 651.6 ± 31.99 g; TR12 504.2 ± 7.74 g; CR12 411.0 ± 7.48 g, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test: p < 0.001) (Fig. 2).

Relative post mortem body composition indicators of intact ad libitum fed sedentary (NF12), treadmill trained ad libitum fed (TR12) and caloric restricted sedentary (CR12) 12 months old male Wistar rats (n = 5/group). Wet weights of epididymal fat pads, left sided perirenal fat mass and – as muscle indicator – the sum of the wet weights of the tibialis anterior muscle, the m. extensor digitorum longus, the soleus muscle and the m. tibialis anterior were measured. Wet weights of the fat and muscle indicators were divided by the body weight (BW) and multiplied by 100. # indicates body weight difference between groups TR12 or CR12 versus NF12, § indicates difference in body weight between groups CR12 versus TR12 or NF12 shown by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test. * indicates differences between TR12 or CR12 versus NF12 post mortem indicators of perirenal fat and muscle mass.

Neither intervention changed the epididymal fat indicator.

The impact of lifestyle interventions on the thermoregulatory effects of central urocortin 2 injections in the younger middle-aged 6-month old male Wistar rats

Neither the training nor the caloric restriction changed the resting, baseline core temperature or oxygen consumption in the younger middle-aged groups. In the younger middle-aged 6-month old NF6 and in the treadmill-trained group (TR6), centrally applied UCN2 elicited a significant 420 min-long hyperthermic response as compared with the age- and physical activity-matched pyrogen free saline (PFS)-treated controls (repeated-measures ANOVA: NF6: F(1,14) = 52.535, p < 0.001; TR6: F(1,10) = 73.69, p < 0.0001). Similarly, the caloric-restricted younger middle-aged rats (CR6) showed a significant 420 min-long hyperthermic response upon the intracerebroventricular (ICV) injection of UCN2 compared with their PFS-treated controls (F(1,21) = 12.97, p = 0.002) (Fig. 3, Supplementary Table 4). With regard to the UCN2-induced increase in oxygen consumption, the rise was significant in all groups as compared with their respective PFS-injected controls (repeated-measures ANOVA NF6: F(1,18) = 11.675, p = 0.003 for 180 min TR6: F(1,18) = 4.55, p = 0.047 for 160 min, CR6: F(1,14) = 16.92, p = 0.001 for 180 min) (Fig. 3, Supplementary Table 5).

Changes in core temperature (ΔTc) and oxygen consumption (ΔVO2) of 6 months old male Wistar rats of different intervention groups following an intracerebroventricular (ICV) injection of urocortin 2 (UCN2). Dark symbols indicate UCN2-treated, empty symbols indicate results of age-matched controls. (Panels a, b, and c show the results obtained in ad libitum fed sedentary NF6, ad libitum fed treadmill trained TR6 and caloric restricted sedentary CR6 rats, respectively.) Control animals received pyrogen-free saline (PFS). Asterisks indicate significant differences between the UCN2-treated and control animals shown by repeated-measures ANOVA. Number of animals per group: TR6 treated n = 7, TR6 control n = 8, NF6 treated n = 8, NF6 control n = 8, CR6 treated n = 10, CR6 control n = 9.

The UCN2-induced hyperthermia was significantly lower in the trained (TR6) than in the age-matched sedentary (NF6) younger adult group F(1,15) = 42.59, p < 0.0001). The UCN2-induced rise in oxygen consumption was similar in the NF6 and TR6 animals (F(1,12) = 0.741, p = 0.406). The UCN2-induced hyperthermia was significantly lower in the caloric-restricted (CR6) than in the age-matched sedentary (NF6) younger adult group F(1,22) = 21.206, p < 0.001) (Supplementary Table 4). The UCN2-induced rise in oxygen consumption did not differ in the NF6 and CR6 animals (F(1,16) = 66,87, p = 0.084). Neither UCN2-induced hyperthermia (F(1,19) = 1.08, p = 0.311 for 180 min, F(1,19) = 0.049, p = 0.827 for 420 min), nor UCN2-induced hypermetabolism differ (F(1,16) = 0.277, p = 0.606 for 180 min, F(1,16) = 0.110, p = 0.745 for 420 min) in the CR6 and TR6 groups (Supplementary Table 5).

Heat loss, indicated by the changes in tail skin temperature increased moderately by the end of the observation period in the NF6 and CR6 groups (repeated-measures ANOVA: NF6: F(1,15) = 12.053, p = 0.003, CR6: F(1,17) = 9.907, p = 0.006). Tail skin temperature did not increase upon UCN2 administration in the TR6 animals (repeated-measures ANOVA: TR6: F(1,12) = 0.21, p = 0.886)(Supplementary Table 2).

The impact of lifestyle interventions on the thermoregulatory effects of central urocortin 2 injections in the older middle-aged 12-month old male Wistar rats

Neither the training nor the caloric restriction changed the resting, baseline core temperature or oxygen consumption in the older middle-aged groups. All older middle-aged 12-month groups showed significant hyperthermic responses following central administration of UCN2. In the NF12 and the treadmill-trained TR12 rats, centrally applied UCN2 induced a significant 420 min-long hyperthermic response as compared with their age- and physical activity-matched PFS-treated controls (repeated-measures ANOVA: NF12: F(1,10) = 25.807, p < 0.001; TR12: F(1,29) = 15.37, p < 0.001 for 180 min, F(1,25) = 10.47 p = 0.003 for 420 min). Similarly, the caloric-restricted older middle-aged rats (CR12) showed also a significant 420 min-long hyperthermic response upon the ICV injection of UCN2 compared with their PFS-treated controls (F(1,21) = 9.44, p = 0.006 for 180 min, F(1,14) = 46.62, p < 0.001) (Supplementary Table 6). With regard to UCN2-induced hypermetabolism, in the NF12 group the UCN2-induced increase in the VO2 remained higher compared to controls for 420 min (repeated-measures ANOVA: F(1,10) = 7.767, p = 0.019) (Supplementary Table 7). In the TR12 animals VO2 increased during the first 80 min upon the central UCN2 injection (repeated-measures ANOVA: F(1,22) = 4.55, p = 0.044). In the CR12 rats, UCN2 induced a 90-min initial rise in VO2 (repeated-measures ANOVA: F(1,14) = 4.742, p = 0.047), followed by another rise later from 290 min to 360 min (F(1,10) = 8.035, p = 0.018) (Fig. 4, Supplementary Table 7).

Changes in core temperature (ΔTc) and oxygen consumption (ΔVO2) of 12 months old male Wistar rats of different intervention groups following an intracerebroventricular (ICV) injection of urocortin 2 (UCN2). Dark symbols indicate UCN2-treated, empty symbols indicate results of age-matched controls. (Panels a, b, and c show the results obtained in ad libitum fed sedentary NF12, ad libitum fed treadmilltrained TR12 and caloric restricted sedentary CR12 rats, respectively.) Control animals received pyrogen-free saline (PFS). Asterisks indicate significant differences between the UCN2-treated and control animals shown by repeated-measures ANOVA. Number of animals per group: TR12 treated n = 10, TR12 control n = 10, NF12 treated n = 8, NF12 control n = 8, CR12 treated n = 10, CR12 control n = 8.

The UCN2-induced hyperthermia was significantly lower in the trained (TR12) than in the age-matched sedentary (NF12) group (F(1,24) = 22.00, p < 0.0001). The UCN2-induced rise in oxygen consumption was similar in the NF12 and TR12 animals (F(1,17) = 3.94, p = 0.063). The UCN2-induced hyperthermia was significantly lower in the caloric restricted (CR12) than in the age-matched sedentary (NF12) group (F(1,23) = 26.59, p < 0.001). The UCN2-induced rise in oxygen consumption did not differ in the NF12 and CR12 animals (F(1,17) = 1.42, p = 0.254). Neither UCN2-induced hyperthermia (F(1,29) = 2.263, p = 0.143 for 180 min, F(1,22) = 0.0489, p = 0.829 for 420 min), nor UCN2-induced hypermetabolism differ (F(1,13) = 0.609, p = 0.449 for 180 min, F(1,13) = 1.47, p = 0.247 for 300 min) in the CR12 and TR12 groups.

Heat loss, indicated by the rise in tail skin temperature increased moderately by the end of the observation period in the NF12 and CR12 groups (repeated-measures ANOVA: NF12: F(1,14) = 22.0583, p < 0.001, CR12: F(1,13) = 21.0717, p < 0.001). Tail skin temperature did not increase upon UCN2 administration in the TR12 rats (repeated-measures ANOVA: TR12: F(1,14) = 0.33, p = 0.575) (Supplementary Table 3).

The effects of lifestyle interventions on the hypothalamic expression of urocortin 2 mRNA in the paraventricular nucleus of older middle-aged 12-month old male Wistar rats

Both the 12-week training and the 12-week caloric restriction decreased the expression of Ucn2 mRNA significantly in the PVN as compared to the control NF12 group (NF12: 23.0 ± 5.13, TR12: 6.9 ± 2.37, CR12: 8.0 ± 0.89 – independent samples Kruskall-Wallis test for non-parametric data: p = 0.011 for TR12 vs. NF12, p = 0.034 for CR12 vs. NF12). There was no difference between the TR12 and CR12 groups (p = 0.671) (Fig. 5).

Urocortin 2 (Ucn2) mRNA expression in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVN). Panels A-C show representative confocal images in the PVN of 12-month-old rats that were normally fed (NF12), subjected to physical training (TR12) or caloric restriction (CR12). Red signal dots correspond to Ucn2 mRNA transcripts. The blue color represents nuclear counter staining with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Due to the relatively low Ucn2 expression level, higher magnification images of the boxed areas in the bottom panels (A’-C’) illustrate the individual Ucn2 signal puncta more efficiently. Histogram D provides a quantitative comparison of Ucn2 expression in the PVN across experimental groups. * p < 0.05, compared to the NF12 group, according to Tukey’s post hoc test upon one-way analysis of variance (F2, 12=8.98, p = 0.004, n = 5/group). Cartoon E illustrates the neuroanatomical localization of the imaged areas shown in A-C. f: fornix, opt: optic tract. Bars: 50 μm in A-C, 10 μm in A’-C’.

Discussion

In our study we have tested the effects of lifestyle interventions, i.e. 12-week caloric restriction and 12-week treadmill training in middle-aged male Wistar rats. The 12-month-old older middle-aged rats provide an animal model of age-related obesity. We have measured the FI, body weight (BW), body composition indicators of these animals followed by thermoregulatory tests on the acute central effects of UCN2, a member of the central corticotropin family involved in a wide variety of fields from stress- to food intake regulation and thermogenesis17. In addition, we have also tested the Ucn2 mRNA expression in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus to identify the changes in the intrinsic activity of this neuropeptide elicited by our lifestyle interventions. The tests of UCN2-induced thermoregulatory responses were also carried out in younger middle-aged, 6-month-old groups, as well.

The 12-week treadmill training surprisingly decreased food intake to a small extent but statistically significantly in the TR12 group (Fig. 1). It is opposed to the expected increase that we predicted because of the increased energy consumption. Our results are in accord with such human observations that described the smallest daily food intake in individuals engaged in light to low moderate physical activity as compared with both sedentary and very active groups13,18. As underlying mechanisms it was suggested that exercise decreases the concentrations of ghrelin and also decreases blood leptin concentration. Exercise also increases the basal blood insulin level and also the postprandial sensitivity to insulin and leptin. Therefore, the energy intake matches the energy expenditure better13,19,20. However, long-term the energy intake should increase as a compensation. Previous observations also showed an increase in early morning appetite showing great variations among individuals. On the other hand, another study of the literature on physical activity and food intake reported that very intensive physical training decreased the appetite even more strongly than moderate exercise21. In this latter study those participants engaged in very intensive training tended to consume smaller meals20.

Our findings are in accord with the report of Zhang and Bi22 that describes decreased FI and weight loss following voluntary wheel-running in male OLETF rats. Their review describes a short-term increase in CRF12,23 and a training-induced increase in thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH) release in the dorsomedial hypothalamus of Sprague-Dawley rats and male OLETF rats along with a suppression of neuropeptide Y release22,23. All these changes may contribute to a decrease in FI.

Previous research raised the hypothesis that treadmill training may induce stress in rats that involves activation of the CRF neurons of the PVN resulting in the activation of the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenocortical (HPA) axis24,25. Another study described that treadmill training increased the blood level of norepinephrine and consequently affected the production of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH)26. Contrary to these findings, Lalanza and coworkers reported that long-term, 32-week treadmill-training decreased the ACTH level27.

With regard to corticotropins, previously treadmill training has been reported to induce activation of the corticotropin system of the PVN24,25. However, when rats become habituated to chronic, repeated treadmill training, the sensitivity of PVN neurons appear to be adjusted, the serotonin release of the dorsal raphe nucleus rises and the stress-associated depressive-like behavior of the rats improve28. Thus, in the long run, the stress-reducing anxiolytic, beneficial effects of the treadmill training emerge.

In our study the 12-week treadmill training decreased the body weight slowly. By the end of the intervention there was a significant difference between the mean BW values of the TR12 and NF12 groups (Fig. 2). The weight loss was much faster and stronger in the CR12 rats.

With regard to post mortem body composition indicators, the 12-week training reduced the relative perirenal fat and increased the relative muscle indicator value significantly as compared with the NF12 animals. On the other hand, the 12-week CR did not induce any significant change in the relative value of either fat type (epididymal or perirenal), despite those observations that showed a reduction in the body fat following caloric restriction4. The relative value of the muscle indicator increased in the CR12 group as compared with the NF12 (Fig. 2). Thus, we did not expect any reduction in the capacity for heat production in either the TR12 or the CR12 groups.

Our results confirm literature data showing that at least medium length training (lasting for 3 months), increases the energy expenditure and leads to loss of body fat resulting in the increase of lean mass13. However, in our model in middle-aged male Wistar rats the 12-week caloric restriction did not decrease either the fat mass indicator or the relative muscle mass. Our results differ from the findings of the Comprehensive Assessment of the Long-term Effects of Reducing Energy Intake (CALERIE) Study, showing a marked loss of visceral adipose tissue with a modest loss of muscle in young non-obese individuals following long-term mild caloric restriction29.

Centrally applied UCN2 induced a significant increase in the core temperature (Tc) of all groups. These responses were smaller in the NF6 than in the NF12 rats that support our previous observations. Earlier, we have demonstrated a consistent age-related increase in the UCN2-induced hyperthermic/hypermetabolic responses in male Wistar rats from 3- to 18 months of age9. The hyperthermic reactions of trained and caloric-restricted rats were lower than those of the respective NF animals. Although all groups showed some rise in oxygen consumption compared with their corresponding control groups, the hypermetabolic responses of the CR6, TR6, and CR12 and TR12 groups were shorter than those of the corresponding NF groups (Figs. 3 and 4). Only the NF12 rats maintained a significant UCN2-induced hypermetabolism throughout the long observation period (Figs, 3,4).

With regard to the effects of treadmill training, TR6 and TR12 groups showed lasting but moderate UCN2-induced hyperthermia with only a modest increase in oxygen consumption. Our findings suggest that the treadmill training may have rejuvenated the metabolic/thermogenetic reactions of the middle-aged rats. Observations of Garcia-Valles and her coworkers reported, that treadmill training may not have improved the lifespan in rodents, but it could improve the mitochondrial content thus delaying aging16.

As an alternative explanation, exercise-induced increase in uncoupling (via UCP-1) may be suggested in the trained animals. Earlier studies reported controversial results about the treadmill training-induced upregulation of thermogenesis genes such as Prdm16 and UCP1. Certain studies supported the idea of treadmill training increasing the level of Prdm16 and UCP1 expression in white adipose tissue30,31. However, other research groups reported that training could not affect the mRNA level of Ucp132 or just weakly stimulated the brown adipose tissue (BAT) thermogenesis without a rise in the level of UCP133.

With regard to heat loss, we have observed a gradual rise in Ts in the NF and CR groups that reached statistical significance. This moderate increase in the heat loss has not prevented the development of UCN2-induced hyperthermia, however it may have contributed to the development of the plateau phase of the hyperthermic response. Trained rats with the most moderate hyperthermic responses in each age-group did not show any significant rise in Ts.

Considering the effects of caloric restriction, the hyperthermic/hypermetabolic effects of the central UCN2 injection were similar in the caloric-restricted and trained groups. Caloric restriction may also have rejuvenated the metabolic/thermogenetic reactions of the middle-aged rats to UCN2. Numerous previous studies indicated that caloric restriction shows tendencies to delay aging4 even the lifespan of rodents could increase15. On the other hand, it has been suggested that there are similarities between obesity and aging4. Thus, obesity may promote aging, caloric restriction may delay it.

However, experimental data suggest other potential mechanisms as well. Some studies emphasize that caloric restriction decreases the basal metabolic rate and the body temperature34. It also affects the plasma level of various hormones34. The CR-induced decrease of leptin and melanocortins may also suppress core temperature and metabolic rate34. Other observations suggest that uncoupling may be suppressed in the muscles and in the fat tissue due to caloric restriction35. However, our 12-week 30% caloric restriction programme has not influenced resting body temperature or oxygen consumption significantly. The post mortem body composition indicators did not show any sarcopenia either (Fig. 2), that could decrease the heat production capacity of the animals. Nevertheless, the mechanisms through which caloric restriction influences body temperature and metabolic rate still remain controversial, since some studies also reported that CR can induce fat browning in white adipose tissue, and suggest that the thermogenesis increases with these changes36,37.

When assessing the Ucn2 mRNA expression, we have to state a limitation of this study: we were unable to provide data on the dynamics of UCN2 at peptide level. This is on one hand because of the lack of a reliable antibody. On the other hand, the reliable immunohistochemical detection of neuropeptides requires often ICV colchicine pre-treatment. Because of the serious side effects of this procedure would have compromised the outcome of this experiment, we have decided to focus on the changes of Ucn2 expression at mRNA level. Both training and caloric restriction appeared to suppress the Ucn2 mRNA expression in the PVN of the hypothalamus as compared with data of the NF12 group (Fig. 5). These results are in accord with the observed changes in the hyperthermic/hypermetabolic responsiveness to central UCN2. It may raise the possibility that the effects of transient, late-onset lifestyle interventions may influence central regulatory mechanisms.

Conclusions

Both treadmill training and caloric restriction show tendencies in delaying aging in middle-aged rats indicated by the altered hyperthermic/hypermetabolic responsiveness to centrally-applied UCN2. There are similarities with aging and obesity, thus we hypothesized that interventions reducing obesity may improve disadvantageous age-associated alteration in central regulation of energy balance. Based on our results, we can confirm that the consequences of lifestyle interventions such as treadmill training and caloric restriction may delay aging.

Methods

Animals

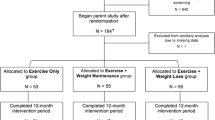

Male Wistar rats were used (6–10 rats/group except for the immunohistochemistry where n = 5/group) from the colony of the Institute for Translational Medicine of the Medical School, University of Pécs, Hungary. We established two age groups, 6-month-old (younger middle-aged) and 12-month-old (older middle-aged) animals for our investigations. Rats were placed individually into (37.5 cm x 21.5 cm x 18 cm) plastic cages, covered with steel grids. The rodents were housed at an ambient temperature of 22–24 °C with a 12 h/12 h dark/light cycle. In our study we formed 3 lifestyle groups, the ad libitum fed NF sedentary, the CR sedentary and the ad libitum fed TR groups. All three groups were fed with a standard laboratory rat chow (11 kJ/g; CRLT/N rodent chow, Szindbád Kft., Gödöllő, Hungary). For the NF and TR groups food and water were available ad libitum. For the CR animals, daily 16 g of rat chow was available representing 70% of the ad libitum food consumption with ad libitum water access5. The rats in the TR group undertook a daily 45-min treadmill training 5 days/week [modified after38. For these training sessions, we used a special treadmill device, which was designed for rats (Harvard Apparatus Panlab, Treadmill Control LE8710). Following a week of gradual habituation to the treadmill device, our training protocol included a 5-min rest followed by a 45-min training at 17.5 m/min speed using a 10% slope each day. The lifestyle interventions in the CR and TR groups started at the age of 3-months or 9-months and lasted for 12 weeks. Our protocols and procedures were approved by the Animal Welfare Committee of the University of Pécs and by the National Scientific Ethical Committee on Animal Experimentation of Hungary. The license was granted by the Government Office of Baranya County (BA02/2000-9/2020). They were also in accordance with the directives of the European Union (86/609/EEC, Directive2010/63/EU) and the rules of the Hungarian Government (40/2013.II.14.) on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes. This study was reported in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines.

Surgical intervention

Following the end of the interventions, at the age of 6- or 12-months, a 22 gauge stainless-steel leading cannula was implanted into the right lateral cerebral ventricle of each Wistar rat for the ICV injections. For the surgeries general anesthesia was performed. We administered a combination of ketamine [78 mg/kg (Calypsol, Richter) and xylazine (13 mg/kg Sedaxylan, Eurovet)] intraperitoneally. To prevent infections, 2 mg Gentamycin was also given to the rats. When the anaesthesia was complete, we fixed the head of the animals into a stereotaxic apparatus. Then, the skin was incised over the skull and the bone was cleaned. For the leading cannula and the miniature fixing screws, altogether three holes were drilled into the bone. The cannula was placed A: −1.0 mm to the bregma, L: 1.5 mm right lateral to the bregma and V: 3.5 mm ventral to the dura39. The guide cannula and the screws were secured on the skull with dental cement. The lumen was closed with a stylet, which could be replaced with an injection cannula during the experiments40.

To check the appropriate location of the guide cannula, ICV injected prostaglandin E2 (Sigma-Aldrich, Budapest, Hungary, P5515, 500 ng/5 µL) was administered to the rats. If there was an at least 1.0 °C rise in the core temperature within an hour, then the appropriate location of the cannula was confirmed. After the end of the experiments, the rats were euthanized by an intraperitoneal overdose injection of urethane (2.8 g/kg, Reanal, Budapest, Hungary)9,40. The injection sites were checked macroscopically post mortem, by coronal sections of the removed and fixed brains. Only those results were included in the statistical analysis where the location of the cannula was appropriate40.

Substances applied

UCN2 (Bachem, Switzerland, Product-No. 4040984) dissolved in PFS or PFS were administered slowly in 5 µL volumes. For the thermoregulatory tests we administered 5 µg UCN2 also in 5 µL volume. In the control group, rats received ICV injections of 5 µL PFS.

Assessment of body weight and food intake

The daily FI and the BW of the rats were measured manually 5 days a week.

Assessment of thermoregulatory functions

Following the end of the interventions, at the age of 6- or 12-months, when the rats recovered from the implantation of the ICV leading cannula, thermoregulatory responsiveness to UCN2 was tested in an indirect calorimeter system (OxyletPro-Physiocage, Harvard Apparatus, MA, USA). The tests were carried out during the daytime period, between 08:00 h and 17:00 h. The partially restrained rats were confined in cylindrical wire-mesh cages in metabolic chambers (size: 20 × 30 × 18.5 cm). Before the experiments the rats were carefully, gradually habituated to the confiners to minimize the restraint stress during the experiments. Oxygen consumption was measured every 10 min, which represents the metabolic rate. The Tc, tail-skin temperature (Ts) and the ambient temperature (Ta) were detected with thermocouples attached to a Benchtop thermometer (Cole-Parmer). The data were recorded on the computer. The heat loss index (HLI) was calculated as follows: (Ts − Ta)/(Tc − Ta). The value of the HLI ranges from 0 to 1. The value 0 indicates maximal vasoconstriction (Ts = Ta), the value of 1 (Ts = Tc) shows maximal vasodilation and heat-loss9,40.

RNAscope in situ hybridization for Ucn2 mRNA

Animals from each 12 months old treatment group were anesthetized intraperitoneally with an overdose of urethane (D = 2.8 g/kg, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) and transcardially perfused with 50 ml of 0.1 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) followed by 250 ml 4% paraformaldehyde in Millonig’s buffer. Brains were dissected and post-fixed. Thirty µm coronal sections were made by a vibratome (Leica Biosystems, Wetzlar, Germany) between the optic chiasm and middle cerebellar peduncle. The success of surgery was verified during sectioning by observing the path of the guide cannula from the cortical surface to the lateral ventricle. Free floating sections were first collected in RNAase free PBS containing 0.01% sodium azide and then transferred to anti-freeze solution for storage at −20°C. Per animal, two coronal sections between bregma − 1.56 mm and − 1.92 mm interspaced by 150 µm were manually selected. These sections bilaterally contained the PVN and were identified based on the rat brain atlas by Paxinos and Watson39. After a modified pretreatment procedure for RNAscope, as we recently published41,42, the staining protocol was applied according to the supplier’s suggestions. The Ucn2 mRNA was visualized by Cyanine 3 (Cy3; 1:3000) with the help of a probe for rat Ucn2 (Cat. No: 829641-C2, Advanced Cell Diagnostics, Newark, CA, USA). The nuclear counterstaining was carried out with 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) and the sections were finally covered with glycerol-PBS (1:1) solution.

In order to confirm the sensitivity of our test, triplex positive (Cat. No: 320891, Advanced Cell Diagnostics, Newark, CA, USA) and negative control (Cat No: 320871, Advanced Cell Diagnostics, Newark, CA, USA) probes were used on randomly selected PVN sections. The positive controls showed well recognizable fluorescence while the negative controls showed no signal (images not shown).

For digitalization of the sections, an Olympus FluoView1000 confocal microscope with 40x (NA: 0.8) objectives was used in analog mode. The excitation and emission of fluorophores were set according to the built-in settings of the FluoView software (Fv10-ASW; Version 0102). With regard to the dyes, blue (DAPI) and red (Cy3) virtual colors were assigned. Four PVN cross-section areas per animal were digitalized. The signal dots indicating the presence of mRNA were manually counted by two independent researchers using the ImageJ software (version 1.52a, NIH). From each animal, four non-edited digital pictures were included, and the average of the counting results (per animal) were used in the statistical analysis. For publication, the Adobe Photoshop software was used for cropping, contrasting and editing the selected representative images.

Determination of post mortem body composition indicators

During the autopsy of those intact animals used for RNAscope measurements also relative post mortem body composition indicators were determined. Wet weights of epididymal fat pads, left sided perirenal fat mass and as a muscle indicator the sum of the wet weights of the tibialis anterior muscle, the m. extensor digitorum longus, the soleus muscle and the m. tibialis anterior were measured and then divided by the body weight of the animals and multiplied by 100.

Statistical analysis

Experimental groups contained 6–10 animals. For immunohistochemistry each group contained 5 rats. The normal distribution of data and the homogeneity of variance was examined and confirmed for all datasets except for data describing the number of Ucn2 mRNA signal puncta. Therefore, this latter dataset was evaluated by the nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test, followed by Bonferroni correction. All results are shown as mean ± SEM. For the statistical analysis, repeated-measures ANOVA and one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test were applied using SPSS for Windows 25.0 software. The significance was set at the level of p < 0.05. With regard to the figures, they were made with the SigmaPlot 11.0 software.

Data availability

The data used to support the findings of this paper are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight Accessed: 19 May 2024.

https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/-/ddn-20210721-2 Accessed 04 Aug 2025.

Blüher, M. Obesity: global epidemiology and pathogenesis. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 15(5), 288–298 (2019).

Le Couteur, D. G., Raubenheimer, D., Solon-Biet, S., de Cabo, R. & Simpson, S. J. Does diet influence aging? Evidence from animal studies. J. Intern. Med. 295, 400–415 (2024).

Pétervári, E. et al. Age versus nutritional state in the development of central leptin resistance. Peptides 56, 59–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.peptides.2014.03.011 (2014).

Eitmann, S. et al. Activity of the hypothalamic neuropeptide Y increases in adult and decreases in old rats. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 22676. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73825-7 (2024).

Füredi, N. et al. Activity of the hypothalamic melanocortin system decreases in Middle-Aged and increases in old rats. J. Gerontol. A. 73 (4), 438–445. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glx213 (2018).

Tenk, J. et al. Age-related changes in central effects of corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) suggest a role for this mediator in aging anorexia and cachexia. Geroscience 39 (1), 61–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11357-017-9962-1 (2017).

Kovács, D. K. et al. Aging changes the efficacy of central urocortin 2 to induce weight loss in rats. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24 (10), 8992. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24108992 (2023).

Fekete, E. M. & Zorrilla, E. P. Physiology, pharmacology, and therapeutic relevance of urocortins in mammals: ancient CRF paralogs. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 28 (1), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yfrne.2006.09.002 (2007).

Jenkins, N. T. et al. Effects of endurance exercise training, metformin, and their combination on adipose tissue leptin and IL-10 secretion in OLETF rats. J. appl. physiol 113(12), 1873–1883 (2012).

Kawaguchi, M., Scott, K. A., Moran, T. H. & Bi, S. Dorsomedial hypothalamic corticotropin-releasing factor mediation of exercise-induced anorexia. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 288 (6), R1800–R1805. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpregu.00805.2004 (2005).

Blundell, J. E., Gibbons, C., Caudwell, P., Finlayson, G. & Hopkins, M. Appetite control and energy balance: impact of exercise. Obes. Reviews: Official J. Int. Association Study Obes. 16 (Suppl 1), 67–76. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12257 (2015).

Vidal, P. & Stanford, K. I. Exercise-Induced adaptations to adipose tissue thermogenesis. Front. Endocrinol. 11, 270. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2020.00270 (2020).

Swindell, W. R. Dietary restriction in rats and mice: a meta-analysis and review of the evidence for genotype-dependent effects on lifespan. Ageing Res. Rev. 11 (2), 254–270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2011.12.006 (2012).

Garcia-Valles, R. et al. Life-long spontaneous exercise does not prolong lifespan but improves health span in mice. Longev. Healthspan. 2 (1), 14. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-2395-2-14 (2013).

Stengel, A. & Taché, Y. CRF and urocortin peptides as modulators of energy balance and feeding behavior during stress. Front. NeuroSci. 8, 52. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2014.00052 (2014).

MAYER, J., MITRA, K. P. & ROY, P., & Relation between caloric intake, body weight, and physical work: studies in an industrial male population in West Bengal. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 4 (2), 169–175. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/4.2.169 (1956).

Douglas, J. A. et al. Acute exercise and appetite-regulating hormones in overweight and obese individuals: a meta-analysis. J. Obes. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/2643625 (2016).

Gómez Escribano, L., Gálvez Casas, A., Escribá Fernández-Marcote, A. R., Tárraga López, P. & Tárraga Marcos, L. Review and analysis of physical exercise at hormonal and brain level, and its influence on appetite. Revisión y análisis Del ejercicio físico a Nivel hormonal, cerebral y Su influencia En El apetito. Clinica e investigacion En arteriosclerosis: Publicacion oficial de La sociedad. Esp. De Arterioscler. 29 (6), 265–274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arteri.2017.04.002 (2017).

Thivel, D. et al. The 24-h energy intake of obese adolescents is spontaneously reduced after intensive exercise: a randomized controlled trial in calorimetric chambers. PloS One. 7 (1), e29840. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0029840 (2012).

Zhang, N. & Bi, S. Effects of physical exercise on food intake and body weight: role of dorsomedial hypothalamic signaling. Physiol. Behav. 192, 59–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2018.03.018 (2018).

Bi, S., Scott, K. A., Hyun, J., Ladenheim, E. E. & Moran, T. H. Running wheel activity prevents hyperphagia and obesity in Otsuka long-evans Tokushima fatty rats: role of hypothalamic signaling. Endocrinology 146 (4), 1676–1685. https://doi.org/10.1210/en.2004-1441 (2005).

Farrell, P. A., Garthwaite, T. L. & Gustafson, A. B. Plasma adrenocorticotropin and cortisol responses to submaximal and exhaustive exercise. J. Appl. Physiol. Respir Environ. Exerc. Physiol. 55, 1441–1444 (1983).

Otsuka, T. et al. Effects of acute treadmill running at different intensities on activities of serotonin and corticotropin-releasing factor neurons and anxiety- and depressive-like behaviors in rats. Behav. Brain Res. 298, 44–51 (2016).

Dishman, R. K., Renner, K. J., White-Welkley, J. E., Burke, K. A. & Bunnell, B. N. Treadmill exercise training augments brain norepinephrine response to familiar and novel stress. Brain Res. Bull. 52 (5), 337–342. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0361-9230(00)00271-9 (2000).

Lalanza, J. F. et al. Long-term moderate treadmill exercise promotes stress-coping strategies in male and female rats. Sci. Rep. 5, 16166 (2015).

Nishii, A., Amemiya, S., Kubota, N., Nishijima, T. & Kita, I. Adaptive changes in the sensitivity of the dorsal Raphe and hypothalamic paraventricular nuclei to acute Exercise, and hippocampal neurogenesis May contribute to the antidepressant effect of regular treadmill running in rats. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 11, 235. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2017.00235 (2017).

Shen, W. et al. Effect of 2-year caloric restriction on organ and tissue size in Nonobese 21- to 50-year-old adults in a randomized clinical trial: the CALERIE study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 114 (4), 1295–1303. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/nqab205 (2021).

Trevellin, E. et al. Exercise training induces mitochondrial biogenesis and glucose uptake in subcutaneous adipose tissue through eNOS-dependent mechanisms. Diabetes 63 (8), 2800–2811. https://doi.org/10.2337/db13-1234 (2014).

Stanford, K. I. et al. A novel role for subcutaneous adipose tissue in exercise-induced improvements in glucose homeostasis. Diabetes 64 (6), 2002–2014. https://doi.org/10.2337/db14-0704 (2015).

Scarpace, P. J., Yenice, S. & Tümer, N. Influence of exercise training and age on uncoupling protein mRNA expression in brown adipose tissue. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 49 (4), 1057–1059. https://doi.org/10.1016/0091-3057(94)90264-x (1994).

De Matteis, R. et al. Exercise as a new physiological stimulus for brown adipose tissue activity. Nutrition, metabolism, and cardiovascular diseases. NMCD 23 (6), 582–590. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.numecd.2012.01.013 (2013).

Speakman, J. R. & Mitchell, S. E. Caloric restriction. Mol. Aspects Med. 32 (3), 159–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mam.2011.07.001 (2011). Epub 2011 Aug 10. PMID: 21840335.

Wang, A. & Speakman, J. R. Potential downsides of calorie restriction. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 21 (7), 427–440. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41574-025-01111-1 (2025).

Fabbiano, S. et al. Caloric restriction leads to Browning of white adipose tissue through type 2 immune signaling. Cell Metabol. 24 (3), 434–446. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2016.07.023 (2016).

Liu, X., Zhang, Z., Song, Y., Xie, H. & Dong, M. An update on brown adipose tissue and obesity intervention: Function, regulation and therapeutic implications. Front. Endocrinol. 13, 1065263. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2022.1065263 (2023).

Kang, C., Chung, E., Diffee, G. & Ji, L. L. Exercise training attenuates aging-associated mitochondrial dysfunction in rat skeletal muscle: role of PGC-1α. Exp. Gerontol. 48 (11), 1343–1350 (2013).

Paxinos, G. & Watson, C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates, 7th ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, ; ISBN 9780123919496. (2013).

Rostás, I. et al. Age-related changes in acute central leptin effects on energy balance are promoted by obesity. Exp. Gerontol. 85, 118–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exger.2016.10.006 (2016).

Ujvári, B. et al. Neurodegeneration in the centrally-projecting Edinger-Westphal nucleus contributes to the non-motor symptoms of parkinson’s disease in the rat. J. Neuroinflamm. 19 (1), 31. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12974-022-02399-w (2022).

Kecskés, A. et al. Characterization of neurons expressing the novel analgesic drug target somatostatin receptor 4 in mouse and human brains. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21 (20), 7788. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21207788 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the expert technical assistance of Ms. M. Koncsecskó-Gáspár, Ms. A. Bóka-Kiss, Ms. A. Jech-Mihálffy, Ms. É. Sós and Ms. I. Orbán.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Research, Development and Innovation Fund of Hungary (K138452 to E.P.); the European Union’s Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF, RRF-2.3.1-21-2022-00011 to M.B.); B.G. was supported by the Thematic Excellence Program 2021 Health Sub-program of the Ministry for Innovation and Technology in Hungary, within the framework of the EGA-16 project of Pécs University (TKP2021-EGA-16); and by the grant NKFI-146117. János Bolyai Research Scholarship of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences (BO/00750/22/5 to V.K.); and Hungarian Research Network (HUN-REN-TKI14016 to V.K.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MB and DKK designed the study, DKK carried out the *in vivo* tests, MB, PE and DKK carried out the statistical analysis. RNAscope methodology and imaging was carried out by BG, VK and GB, evaluation of non-edited digital images, DKK, EP and BG. DKK and MB wrote the original draft, they were responsible for the manuscript preparation and final editing, EP was responsible for funding acquisition. All authors agreed with regard to the interpretation of the data, all authors contributed to the final manuscript and gave approval to the submitted final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kovacs, D.K., Berta, G., Kormos, V. et al. Treadmill training or caloric restriction delays aging-associated increase in urocortin 2-induced hyperthermia in middle-aged male Wistar rats. Sci Rep 16, 2712 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32585-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32585-8