Abstract

Because a high signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) is critical in enhancing the accuracy of subsequent processing, noise reduction remains a pivotal challenge in seismic signal processing, especially for complex noise interference scenarios. To address this, we propose a novel network termed MSARDNet for seismic signal denoising, with its novelty in a multi-level feature processing architecture integrating innovative modules. Specifically, the architecture comprises an encoder module, a ResDC module, and a decoder module. The encoder integrates depthwise separable convolution to efficiently extract local features with reduced parameters and improved computational efficiency. Prior to pooling, an enhanced channel attention mechanism is incorporated to adaptively emphasize critical features and suppress noise based on their importance, further boosting denoising efficacy. The ResDC module combines dilated convolutions for multi-scale receptive field expansion and residual connections for gradient optimization, ensuring feature integrity and facilitating joint extraction of multi-scale features and global context. This design effectively mitigates information loss, preserves useful signals, and enhances SNR by filtering complex noise. Through comparative experiments on synthetic and field data using denoising methods such as U-Net, DnCNN, and DeepDenoiser, MSARDNet achieved signal-to-noise ratio improvements of + 15.94 dB, + 12.03 dB, and + 4.83 dB over these methods, respectively. The results demonstrate that MSARDNet outperforms existing methods in eliminating complex background noise and holds broad application prospects in seismic data processing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Earthquakes directly destroy infrastructure, causing heavy casualties and economic losses, and trigger secondary disasters like landslides and disease outbreaks1,2, making loss mitigation a key research focus. They also offer a critical window to study Earth’s internal structure and dynamics: seismic signal analysis helps unravel subsurface structures3,4,5,6, tectonic movements, and related phenomena7. However, seismic signals are often contaminated during propagation by noise from complex geological conditions (e.g., inhomogeneous formations) and external interference (e.g., human activities), significantly reducing SNR and data quality8,9,10. This hinders subsequent processing11, so effective denoising and SNR enhancement are pivotal for reliable downstream analyses.

Seismic data acquisition suffers from diverse noise, including broadband Gaussian noise (e.g., ambient noise), impulsive transient noise (e.g., equipment vibration), and low-frequency drift noise (e.g., sensor drift)12,13. Their time-frequency aliasing severely degrades signal quality, posing challenges to traditional denoising methods—especially in high-noise environments where signal-noise discrimination is difficult14. Time-frequency filtering methods (e.g., bandpass15,16, median17,18, Wiener19, time-frequency peak filtering20,21,22 leverage time-frequency differences between signals and noise. They perform well when frequency bands are distinct but cause artifacts or detail loss with overlapping bands. Time-frequency transformation methods (wavelet23,24,25, STFT26,27, curvelet28,29, shearlet30,31,32 decompose signals via sparse representation and thresholding. Effective for non-stationary signals, they are sensitive to decomposition scales and thresholds, with improper settings leading to distortion. Modal decomposition techniques (EMD33,34,35, CEEMDAN36, VMD37,38,39 decompose complex signals into simpler components, adapting well to nonlinear/non-stationary data and mitigating low-frequency drift. However, they are sensitive to mode mixing and parameter selection, with improper handling causing distortion. Rank reduction methods (e.g., SVD40, MSSA41 separate signals from noise by extracting matrix principal components via low-rank decomposition. They exhibit significant advantages in multichannel data processing, yet their performance is to some extent dependent on parameter selection (e.g., rank value, window size). Additionally, their adaptability to areas with complex geological conditions is limited.

In recent years, deep learning—based on artificial neural networks—has advanced significantly42, with remarkable progress in seismic signal denoising. End-to-end feature learning enables it to separate complex noise components, introducing a new paradigm. Si et al.43 applied DnCNN to attenuate random seismic noise; using residual learning in deep convolutional networks, it recovers clearer signals but is limited to Gaussian/random noise, performing poorly on non-Gaussian or coherent noise. Zhao et al.44 improved DnCNN to suppress low-frequency noise in desert seismic data (where signals and random noise overlap severely) but still struggles with non-Gaussian noise. Zhu et al.45 developed DeepDenoiser, which constructs nonlinear mappings between noisy and denoised data to eliminate complex noise, yet has limitations in accuracy and generalization. Zhang et al.46 combined DnCNN’s residual learning with U-Net, enhancing generalization (especially for low-frequency bloating noise) but with limited effectiveness across diverse regional seismic data. Saad et al.47 proposed an unsupervised method for single-channel denoising, removing random noise via STFT feature learning and signal mask construction, but it performs inadequately in complex non-Gaussian noise. Wang et al.48 presented RTDenoiser, a real-time method that effectively removes various noises and improves small earthquake detection, though its performance degrades in noise-dominated scenarios. Cui et al.49 proposed a ground-truth-free method for 3D seismic denoising and reconstruction, eliminating the need for paired clean/noisy data. With channel attention to enhance key feature focus, this method shows strong robustness in both synthetic and real seismic data. Yu et al.’s MAE-GAN50 achieves simultaneous super-resolution and denoising of post-stack seismic profiles via multi-scale residual modules, dual attention mechanisms, and an adversarial network, effectively recovering weak signals. Zhu et al.51 applied diffusion models to DAS-VSP data denoising to suppress complex noise, while Cui et al.52 further proposed an unsupervised diffusion framework, showing advantages in weak signal preservation on field data. Saad et al.53 proposed an unsupervised DAS denoising method with CWT guidance and self-attention. It attenuates complex noises without labeled data, overcoming traditional methods’ signal leakage and supervised learning’s label dependence. Liu et al.54 proposed a C-DDPM-based zero-shot method and introduced an adaptive FK-domain condition. It solves label scarcity and balances detail preservation/SNR improvement in multi-noise scenarios. Ding et al.55 proposed HMR-Net (Hybrid Multi-Resolution Network), optimizing multi-scale feature extraction/sampling on U-Net, and it performs well in suppressing complex background noise and recovering weak signals. Qiao et al.56 proposed the Multi-Scale Residual Attention Network (MRANet) for fading noise and step-like signals in DAS-VSP data. The network improves data quality by capturing global structure and preserving local details, but it has limitations in its sensitivity to noise intensity and its ability to handle untrained noise. Li et al.’s57 Swin Transformer boosts cross-region information interaction via local and shifted window self-attention, outperforming wavelet denoising in Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR). However, it has limitations (e.g., small dataset size, undisclosed geological diversity), with its generalization ability yet to be verified. Chen et al.58,59 proposed an unsupervised Kolmogorov-Arnold Network (KAN)-based method, modeling nonlinear mapping via learnable spline basis functions. Compared with traditional Multi-Layer Perceptrons (MLPs), it enhances model interpretability and alleviates deep learning’s “black-box” problem. Sheng et al.60 pre-trained a Transformer via self-supervised Masked Autoencoder (MAE) to learn seismic data’s universal features; this pre-trained encoder serves as a general feature extractor for downstream tasks (including denoising) and exhibits some advantages compared to scratch-trained models (e.g., U-Net) when fine-tuned or with frozen features, showing decent generalization. However, in terms of capturing edge details of low-signal-to-noise seismic data, it still has a slight improvement space compared to small models specifically optimized for such scenarios.

Seismic signal denoising algorithms face two primary challenges:

-

1.

Seismic signals are inherently nonlinear and non-stationary, comprising diverse frequency and time-domain components shaped by propagation paths and subsurface medium interactions. Traditional convolutional methods—limited by small receptive fields—struggle to capture spatiotemporal and multi-scale features, particularly when signal and noise spectra overlap, hindering accurate separation. Furthermore, these methods tend to be computationally inefficient.

-

2.

Natural seismic signals are susceptible to diverse noise sources, including periodic industrial noise, impulsive noise, and irregular background noise. The spatiotemporal variability of such noise complicates its discrimination from target signals. Existing algorithms often fail to robustly extract seismic signal features and cope with complex noise, resulting in suboptimal denoising performance and limited SNR enhancement.

Motivated by the aforementioned challenges, this study aims to address the inability of existing seismic signal denoising methods to effectively mitigate complex noise interference. To this end, we have developed a novel denoising framework termed MSARDNet. It innovatively leverages depthwise separable convolution (DSConv) for a lightweight encoder (balancing local feature extraction and parameter reduction), embeds an enhanced channel attention mechanism into pooling, and designs a ResDC module (integrating residual connections and dilated convolutions to expand multi-scale receptive fields and optimize gradient transfer). This design refines existing seismic denoising methods in model efficiency, noise discrimination, and multi-scale feature integration, serving as a useful technical support for related research. The three key innovations of MSARDNet are specifically implemented as follows:

-

1.

In the encoder, traditional convolutions are replaced with depthwise separable convolutions. Despite involving more modular operations, this design reduces computational load and parameter count while maintaining robust feature extraction capability—enhancing model efficiency and mitigating overfitting risks, which is critical for handling large-scale seismic datasets.

-

2.

An innovatively improved channel attention mechanism is integrated with multi-scale convolutional operations, enabling the model to more precisely focus on effective signals and suppress noise. When combined with pooling operations, this design further optimizes feature preservation and denoising efficacy, thereby facilitating efficient execution of seismic signal denoising tasks.

-

3.

Guided by residual learning, we design the ResDC module by incorporating dilated convolutions. This module overcomes limitations of conventional convolutions in seismic signal processing—such as restricted receptive fields, discontinuous information extraction, and suboptimal denoising performance—by effectively capturing multi-scale contextual information, expanding the receptive field, and minimizing information loss.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: “Method” elaborates on the MSARDNet architecture, including its overall structure and core modules. “Experiments” describes the dataset, preprocessing procedures, and evaluation metrics, followed by an analysis of experimental results. “Field seismic data application” validates the model on field seismic signals and discusses its performance. Finally, “Conclusion” concludes the paper.

Method

Denoising theory

Seismic signal contains both effective signal and noise components, denoising is to realize the separation of the two, and as far as possible to make the denoising results closer to the original seismic information. The seismic signal can be viewed as the sum of the effective signal and the noise, which can be expressed as:

Where \(X\) = {x1, x2, …, xm} is a seismic signal; \(S\)= {s1, s2, …, sm} is an effective signal; \(N\)= {n1, n2, …, nm} is noise.

In this study, we designed a network \({f}_{\theta}(\cdot)\), whose purpose is to directly predict the noise component N in the input signal X. The network \({f}_{\theta}(\cdot)\) processes the seismic signal and outputs predicted noise component. The equations can be expressed as:

Where \(\bar{S}\) is the denoised signal; \(\bar{N}\) is the predicted noise component; \({f}_{\theta}\left(X\right)\) is a network.

In the denoising process, our goal is to make \(\bar{S}\) closely approximate the original valid signal S, so as to ensure effective noise removal and high-fidelity signal recovery.

Architecture of U-Net

U-Net was initially proposed for semantic segmentation, characterized by a symmetric U-shaped encoder-decoder architecture (Fig. 1). Specifically, the encoder extracts features through two consecutive standard convolution operations followed by ReLU activation; downsampling is achieved via max-pooling, which halves the feature map resolution while doubling the channel count. In the decoder, transposed convolution is used for upsampling to gradually restore resolution, and skip connections integrate shallow features from the encoder with deep features from the decoder (via concatenation), thereby enhancing detail preservation. The network concludes with a final convolution layer that maps the processed features to the output, enabling end-to-end input-output mapping for pixel-level prediction.

Architecture of MSARDNet

U-Net’s skip connections effectively integrate multi-level features and preserve details, while its symmetric encoder-decoder structure enables robust training with limited data. However, its reliance on standard convolutions—with restricted receptive fields focused on local features—limits handling of complex multi-scale noise in seismic signals (which exhibit long-range spatial correlations and diverse frequencies). Additionally, shallow encoder features in skip connections often retain substantial noise (e.g., high-frequency random noise) that propagates through concatenation, causing residual noise in denoised outputs.

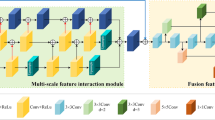

To address seismic denoising under complex noise, we propose MSARDNet (Fig. 2), which retains U-Net’s symmetric encoder-decoder structure and comprises an encoder, ResDC module, and decoder. The encoder uses depthwise separable convolutions for efficient local feature extraction and integrates an enhanced channel attention mechanism (MS-CAM); via dynamic weight allocation, MS-CAM adaptively emphasizes noise characteristics to strengthen extraction of critical signal features. The ResDC module combines residual connections and multi-scale dilated convolutions to explore global features and local details, improving noise separation precision and reducing residual noise. The decoder employs transposed convolutions to reconstruct temporal resolution, merging multi-level features via skip connections to eliminate noise while preserving subtle signal details. Detailed specifications are provided in Table 1.

To verify the rationality of the MSARDNet structure design and clarify its denoising mechanism, we analyzed the feature map visualization results of key modules (see Supplementary Fig. S1 and Fig. S2 online). Figure S1 shows the 64-channel feature maps of the first layer of the encoder, and Fig. 2 further presents the model’s feature evolution process.

Encoder module

Traditional convolutional neural networks extract seismic signal features via standard convolutions. However, due to the extended duration and complex noise patterns of seismic signals, traditional convolutions alone struggle to balance processing speed with effective extraction of multi-scale, dynamically varying features. To address this, our research integrates depthwise separable convolutions and an enhanced channel attention mechanism (MS-CAM) into the encoder (Fig. 3), which comprises four encoding layers. The seismic signal first undergoes two depthwise separable convolutions with ReLU activation for local feature extraction. An MS-CAM then dynamically adjusts channel weights, enabling the network to focus on critical seismic features. Finally, pooling completes downsampling to further compress feature map spatial dimensions.

Assuming one-dimensional input data with C channels, each of size W, zero-padded and with a stride of 1. For standard convolution using F convolutional filters of size 1×K applied to the C×W input data, producing F feature maps of size W. The number of parameters \({P}_{sc}\) and the computational cost \({C}_{sc}\) required for standard convolution are as follows:

Unlike standard convolution, depthwise separable convolution comprises depthwise and pointwise convolutions. Depthwise convolution applies a 1×K filter to each input channel, generating C feature maps of size W. Pointwise convolution then uses F 1 × 1 filters on these maps to produce F feature maps of size W. The parameter count (\({P}_{dc}\)) and computational cost (\({C}_{dc}\)) of standard convolution are as follows:

Here, C denotes input channels, W the width of each channel, F the number of convolutional filters, and K the kernel size. Unlike standard convolution, depthwise separable convolution reduces parameters and computational cost while capturing local features.

To enhance feature representation, this study improves the channel attention mechanism by incorporating multi-scale convolution. This allows convolutional kernels with different receptive fields to capture richer multi-scale information. As shown in Fig. 3c, the input feature X first undergoes four one-dimensional convolutions with different kernel sizes (k = 1, 3, 5, 7), generating multi-scale features: X1 = ReLU(Conv1d1(X)), X2 = ReLU(Conv1d3(X)), X3 = ReLU(Conv1d5(X)), X4 = ReLU(Conv1d7(X)), where Conv1dk denotes a one-dimensional convolution operation with a convolution kernel size of 1xk. Subsequently, these feature maps are spliced in the channel dimension to form a feature map Xconcat that fuses features of different scales; then, a global average pooling operation is performed on Xconcat to obtain a global feature vector, denoted as:

where L is the length of the feature map, and Xconcat(i) is the value at the i-th position in the feature map. Then, g is input into a shared two-layer fully connected network and the weight w is obtained by the activation function, denoted as:

where W1 and W2 are the weights of the fully connected layers, and σ denotes the Sigmoid activation function, and finally Xconcat and w are multiplied together to obtain the output Y.

By adjusting the feature channels, the MS-CAM effectively enhances the ability of the network to extract useful information and refines the feature representation, which makes the network as a whole more suitable for processing complex signals, especially seismic signals with multi-scale features.

ResDC module

Standard convolution’s limited sampling of dilated regions causes discontinuous seismic information extraction and suboptimal denoising. To address this, a Residual Dilated Convolution (ResDC) module is designed, combining dilated convolution and residual connections. Using dilated convolutions with multiple dilation rates, it captures multi-scale signal context (structure in Fig. 4). Dilated convolution adds a dilation rate to standard convolution, expanding the receptive field and capturing multi-scale information but introducing residual noise due to redundancy between adjacent data. Additionally, its reliance on independent subsets for neighboring data leads to insufficient long-range correlation. Thus, prior to each dilated convolution, features are fused with previous ones, and residual connections reduce information loss. The post-convolution feature map is calculated as follows:

In the formula, X is the length of the output feature map, i is the length of the input feature map, p is the number of zeros padded during the convolution process, k is the size of the convolution kernel, d is the dilation rate, and s is the stride.

Subsequently, the convolution results with different dilation rates and the global pooling results are concatenated. The concatenated feature vector is then further processed through a 1 × 1 convolution for additional fusion.

Here, \(\parallel\) denotes concatenation along the channel dimension. Finally, through residual connections, the input signal X is added element-wise to \({X}_{Conv1d}\) to obtain the output Y.

Decoder module

The decoder employs layer-by-layer transposed and standard convolutions to gradually restore feature map dimensions to the original signal size. As shown in Fig. 5’s dashed box, each decoding block—consisting of transposed convolution, standard convolution, and ReLU activation—progressively recovers time resolution. Post-upsampling, it concatenates current output with the encoder’s corresponding feature map for fusion: transposed convolution expands spatial dimensions, while convolution refines features to preserve channel count and structure. A final 1 × 1 convolution maps the feature map to a denoised signal of original dimensions.

In 1-D transposed convolution, upsampling of the feature map is achieved by applying a transposed operation, and the process can be formulated as follows:

The output feature map size H′ of the transposed convolution is calculated using the following formula:

where X is the input feature map, K is the convolution kernel, S is the stride, and P is the padding, H represents the length of the input feature map.

Experiments

All experiments were conducted in Python using PyTorch on a PC with an Intel Core i7-14700KF CPU (4.88 GHz), 32 GB RAM, and an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4080 SUPER GPU. GPU parallel computing accelerated gradient calculations and model training by reducing computational burden, enhancing processing efficiency—valuable for seismic analysis to enable efficient model training and testing.

Dataset and preprocessing

The Stanford Earthquake Dataset (STEAD61—comprising over 1.2 million seismic waveforms and 450,000 events—served as the training dataset. We selected high-quality 100 Hz seismic signals (SNR > 50 dB, P/S-wave annotation weights > 0.8), yielding 24,041 clean signals and 105,800 non-seismic noise samples. Due to unreliable absolute amplitudes (from original signal variations) and to prevent data overflow/accuracy issues, sample data underwent Z-score normalization to accelerate convergence and enhance numerical stability during training, with the formula:

Here, z represents the normalized value, x is the original data, µ is the mean of the data, and σ is the standard deviation of the data.

Evaluation metrics

To quantitatively evaluate the denoising performance of the MSARDNet model, three evaluation metrics—Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR), Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), and correlation coefficient (r)—were employed. These metrics provide an objective assessment of the denoising effect. The calculation methods for these metrics are given by the following formulas:

Here, yi and y represent the original signal, zi and z represent the denoised signal, and N denotes the total number of samples in the seismic signal.

A higher SNR indicates more effective signal information and better denoising performance. RMSE measures the error between output and label signals at each sampling point, with values closer to 0 indicating better results. A correlation coefficient closer to 1 reflects stronger similarity between denoised and true signals, preserving nearly all location information. Together, these three metrics comprehensively evaluate denoising effects from multiple perspectives.

Ablation experiment

The evaluation metrics of the experiments in this section are all calculated based on the validation set used during the training process.

To verify the impact of depthwise separable convolution, the improved channel attention mechanism, and the ResDC module on MSARDNet performance, we conducted ablation experiments with the following configurations: all ablation models were trained using the Adam optimizer to ensure unified optimization conditions; original U-Net (Ablation Model U-Net); model retaining ResDC and MS-CAM (ResDC-MS-CAM); model retaining depthwise separable convolution (EncDep) and MS-CAM (EncDep-MS-CAM); model retaining EncDep and ResDC (EncDep-ResDC); and model retaining all three components (MSARDNet). Results are shown in Table 2.

Table 2 indicates Ablation Model U-Net achieved the lowest average SNR, confirming the significant role of EncDep, ResDC, and MS-CAM in MSARDNet’s denoising performance. Compared to MSARDNet, average SNR decreased by 3.15 dB for EncDep-MS-CAM (lacking ResDC), 2.89 dB for EncDep-ResDC (lacking MS-CAM), and 1.77 dB for ResDC-MS-CAM (lacking EncDep). These results demonstrate that removing any single module significantly degrades network performance.

To verify the efficiency of depthwise separable convolutions(EncDep) in MSARDNet, we designed a single-variable controlled experiment: only the encoder’s convolution type differed (baseline with traditional convolutions, MSARDNet with depthwise separable ones), with other modules, parameters, and experimental conditions unchanged. Experiments showed the baseline had 12.498 M parameters, 237.823 GFLOPs, and 33.91ms per-batch inference time; MSARDNet reduced these to 10.032 M (19.7% less), 190.151 GFLOPs (20% less), and 26.88ms (20.7% efficiency gain). Overall improvement was limited, as depthwise separable convolutions only applied to the encoder (≈ 1/3 of the model). A standalone encoder experiment more intuitively showed advantages: the traditional convolution encoder had 1.563 M parameters, 52.015 GFLOPs, and 7.12ms inference time for 32 samples; the depthwise separable one reduced these to 458 K (70.7% less), 16.543 GFLOPs (68.2% less), and 4.05ms (43.1% efficiency gain).For practical seismic data processing, even a ~ 20% overall efficiency improvement reduces hardware consumption in large-scale data batch inference.

We further optimized key hyperparameters by testing three parameter sets, keeping all variables constant except the target parameter:

-

1.

Learning rate (LR): Critical for convergence. Testing LR = 0.01, 0.001, 0.0001, and 0.00001 (Table 3) showed LR = 0.0001 yielded the best SNR and correlation coefficient (r), with the lowest RMSE. Excessively high LR impaired convergence, while overly low LR slowed training, so LR = 0.0001 was selected.

-

2.

Batch_size: Influential for optimization and speed. Testing powers of 2 (16, 32, 64, 128; Table 4) revealed Batch Size = 32 maximized SNR. Larger sizes reduced accuracy, while very small batches slowed training, so 32 was chosen.

-

3.

Training epochs: Determined by evaluating 100, 200, and 300 epochs (Table 5). Epoch = 200 achieved the highest SNR and r, with the lowest RMSE. Epoch = 100 led to insufficient training, while epoch = 300 caused overfitting, so 200 was selected.

Comparative experiment

One-dimensional seismic data denoising

To compare MSARDNet with three deep learning denoising methods (U-Net, DnCNN, DeepDenoiser), 4,808 test signals were used. Meanwhile, to verify the robustness of the results, we calculated the mean and standard deviation of each performance metric on the test set through five independent repeated experiments, with the relevant results presented in Table 6. This indicates that MSARDNet exhibits the optimal stability in terms of SNR, RMSE, and r metrics. Four randomly selected signals were visualized in Fig. 6 for intuitive evaluation. U-Net, DnCNN, and DeepDenoiser were reconstructed in PyTorch, trained on the dataset in “Dataset and preprocessing”, and all methods were assessed using the same test dataset.

Figure 6. illustrates clear differences in denoising performance among the four methods. In subplot (a), the original signal has distinct peaks and a stable baseline, while the noisy version (SNR = 7.26 dB) is chaotic with high noise. Post-denoising, MSARDNet achieves the highest SNR (23.68 dB, + 18.42 dB), closely matching the original with restored peaks and baseline. U-Net (19.71 dB) removes some noise but yields less smooth waveforms; DnCNN (18.12 dB) and DeepDenoiser (20.35 dB) weaken useful components, resulting in blunted peaks and lower restoration. Subplot (b) shows a noisy signal (SNR = 2.23 dB) with intense interference. MSARDNet outperforms others (24.93 dB vs. U-Net 21.42 dB, DnCNN 18.59 dB, DeepDenoiser 21.86 dB), restoring most features while maintaining low noise. In subplot (c), the noisy signal (SNR = 1.57 dB) is heavily interfered. MSARDNet achieves 18.72 dB, surpassing U-Net (12.53 dB), DnCNN (13.45 dB), and DeepDenoiser (16.44 dB), with waveforms highly similar to the original and intact signal integrity. In subplot (d), despite the noisy signal having an SNR of -2.82 dB and severe noise interference, MSARDNet still demonstrates strong denoising ability with an SNR of 13.67 dB, outperforming U-Net’s 8.75 dB, DnCNN’s 8.41 dB, and DeepDenoiser’s 9.26 dB. MSARDNet can effectively restore the main features of the signal in strong noise, significantly improving signal quality.

To better evaluate denoising models under complex noise, synthetic seismic signals with varying SNRs were used to compare MSARDNet, U-Net, DnCNN, and DeepDenoiser. The experimental results are presented in Fig. 7, which provides a detailed comparison of these methods in terms of signal-to- noise ratio (SNR), root mean square error (RMSE), and correlation coefficient (r).

Figure 7 shows that across all initial SNRs, MSARDNet consistently outperforms others, achieving the highest SNR, lowest RMSE, and r closest to 1. This indicates significant SNR improvement, reduced RMSE, and stronger correlation, demonstrating its ability to suppress background noise and restore signals highly similar to the original.

In contrast, U-Net, DnCNN, and DeepDenoiser are less effective in selective noise suppression, as they struggle to enhance seismic signal features, hindering background noise removal. MSARDNet’s superiority stems from its improved channel attention module, which focuses on key signal information, yielding better denoising results.

Multi-channel seismic profile data denoising

To further enhance the model’s universality for seismic data denoising tasks, this section reconstructs it into a processing framework suitable for 2D multi-channel profile seismic data, and systematically evaluates the model performance using synthetic seismic records. The simulated record used in the experiment is shown in Fig. 8a: Noisy data with a signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of 8.26 dB was generated by adding random Gaussian noise to the synthetic seismic data created through forward modeling using Ricker wavelets (Fig. 8b). At this point, effective signals are masked by strong background noise, and the continuity of reflection events is severely disrupted.

Figures 8c–f show the denoising results of U-Net, DnCNN, DeepDenoiser, and MSARDNet, respectively. Among them, MSARDNet achieves the optimal SNR improvement, increasing by 10.71 dB compared to the original noisy data (with an overall SNR reaching 18.97 dB), which is substantially superior to U-Net (2.59 dB), DnCNN (3.18 dB), and DeepDenoiser (6.59 dB). The results demonstrate that MSARDNet can effectively recover clear reflection events from noise, and its denoising performance is significantly better than that of the comparative models, providing reliable data support for subsequent seismic interpretation and analysis.

Different noise types experiment

To verify the proposed method’s effectiveness across noise environments, we compared how four noise types affect seismic signals and evaluated MSARDNet against U-Net, DnCNN, and DeepDenoiser.

Figure 9a shows that wideband Gaussian noise obscures waveforms and hides details. U-Net removes some noise to reveal a faint signal outline but leaves residual fine noise. DnCNN reduces more noise, improving continuity and recognizability. DeepDenoiser further reduces noise for a smoother curve but retains slight traces. In contrast, MSARDNet nearly eliminates noise, producing smooth fluctuations that accurately restore the signal’s true characteristics, aiding subsequent analysis.

Figure 9b illustrates low-frequency baseline drift noise shifts and distorts the signal baseline. U-Net partially restores the signal but leaves noticeable low-frequency drift, with the baseline not fully normalized and suboptimal stability. DnCNN better corrects the baseline, reducing low-frequency interference. However, DnCNN’s baseline remains unstable in some regions. DeepDenoiser effectively eliminates low-frequency drift, stabilizing the baseline to reveal the signal’s true form. MSARDNet further refines correction: it precisely stabilizes the baseline, yielding a smooth, undistorted curve that maximally restores the original signal, strongly supporting accurate analysis.

Figure 9c shows impulsive noise as random high-amplitude spikes, disrupting signal continuity. U-Net removes some but leaves residual pulses with visible sharp peaks. DnCNN suppresses most pulses to enhance continuity but retains faint traces. DeepDenoiser nearly smooths the signal but risks losing minor details misclassified as noise. In contrast, MSARDNet accurately distinguishes noise from details, fully eliminating pulses while preserving subtle features—ensuring waveform precision and aiding in-depth seismic property studies.

Figure 9d illustrates highly complex non-stationary mixed noise, severely distorting signals and obscuring effective information. U-Net denoising results in blurry signals with incomplete information (noise masking key features). DnCNN and DeepDenoiser improve slightly but suffer significant detail loss and distortion under complex noise. MSARDNet, with strong adaptability, extracts signal features from chaotic noise, removing interference to produce clear, amplitude-accurate waveforms closely matching the true signal. This reliably supports analysis in complex environments, demonstrating notable advantages.

Out-of-distribution experiment

To verify MSARDNet’s out-of-distribution generalization, robustness, a comparative experiment was conducted on the TXED dataset (Chen et al.62)—distinct from STEAD in geography/noise/events, with 321 Texas stations (2017–2023), 21,767 events, and 312,231 1D three-component waveforms (SNR: −11 to 97 dB)—alongside U-Net, DnCNN, and DeepDenoiser. Experimental rigor was ensured by selecting 4,808 1D samples (matching STEAD’s test scale) paired with independent noise (no replacement), applying consistent Z-score normalization, and using STEAD-pre-trained weights (no fine-tuning).

Quantitative results are shown in Table 7. MSARDNet significantly outperformed U-Net, DnCNN, and DeepDenoiser. It achieved a denoised SNR of 21.32 dB (a 15.9 dB gain), surpassing U-Net (12.64 dB), DnCNN (15.28 dB), and DeepDenoiser (17.56 dB). The RMSE was reduced to 0.2286, a substantial decrease from the original 0.4825, representing 31.9%,

21.1%, and 18.7% lower errors than U-Net, DnCNN, and DeepDenoiser, respectively, with the smallest fluctuations across stations. The waveform correlation coefficient (r) reached 0.978, also superior to U-Net (0.893), DnCNN (0.926), and DeepDenoiser (0.937).

Qualitative results are shown in the Fig. 10. In the time domain, MSARDNet effectively suppressed strong noise while retaining key seismic features (P/S-wave onsets, amplitude variation patterns, waveform continuity)—unlike U-Net (significant noise residue), DnCNN (local noise fluctuations), and DeepDenoiser (suboptimal balance between detail preservation and denoising). In the frequency domain, it maximally suppressed wide-band noise, making the characteristic frequency peaks of valid 1D signals clearly distinguishable while fully preserving feature-band energy, outperforming benchmarks that suffered from clutter residue or indistinct peaks.

These results collectively confirm MSARDNet’s superior out-of-distribution generalization, robustness, and cross-station adaptability—holding vital value for practical seismic signal processing tasks involving distribution shifts or diverse station deployments.

Field seismic data application

One-dimensional seismic data denoising

To further verify MSARDNet’s practicality and versatility, we applied it to real seismic event data from the China Earthquake Networks Center (2013–2020, Diting dataset), which includes diverse signals from earthquakes of varying magnitudes, depths, and geological conditions.

We randomly selected 1,056 waveform samples; Table 8 shows MSARDNet improved average SNR from 8.98 dB to 31.58 dB (71.56% enhancement). It outperformed U-Net, DnCNN, and DeepDenoiser by 15.94 dB, 12.03 dB, and 4.83 dB respectively, confirming superior denoising performance.

Furthermore, Fig. 11 shows the original seismic signal has significant fluctuations and chaotic waveforms due to interference. U-Net denoising smooths it somewhat but leaves fluctuations and irregularities, suggesting potential detail loss. DnCNN reduces fluctuations and smoothens the waveform but retains some noise, with room to improve detail preservation. DeepDenoiser suppresses noise well but has irregular fluctuations and lost components in peak-trough transitions, which may affect precise analysis. In contrast, MSARDNet excels in both smoothness and detail preservation, effectively retaining valid features—critical for identifying key attributes like P-wave arrival times and amplitude changes. Visual comparison of denoised waveforms confirms MSARDNet’s advantages: it effectively removes complex background noise while preserving key signal features, with significant practical value for earthquake monitoring and analysis. Additionally, as seen in the enlarged view, the initial vibration direction of the P-wave processed by each denoising model is consistent with that of the original noisy signal, with no polarity reversal. The original signal exhibits severe fluctuations due to noise: U-Net leaves obvious residual fluctuations, DnCNN fails to completely suppress noise, and DeepDenoiser shows irregular fluctuations in the peak-trough transition regions and even suffers from partial signal loss. In contrast, MSARDNet can smooth out noise fluctuations while fully preserving the amplitude variation patterns and phase continuity of the P-wave.

Multi-channel seismic profile data denoising

To comprehensively evaluate the proposed method, this study selected a set of two-dimensional field seismic data for in-depth analysis to further validate the performance of MSARDNet. The dataset comprises 184 seismic traces, each with 500 sampling points (Fig. 12a). Figure 12b–e illustrate the denoising effects of U-Net, DnCNN, DeepDenoiser, and MSARDNet, respectively.

The experimental results demonstrate that MSARDNet significantly outperforms other methods in two-dimensional seismic data denoising: its denoising results (Fig. 12e) not only markedly reduce noise interference compared to the original data (Fig. 12a) but also effectively preserve key seismic waveform features, whereas U-Net (Fig. 12b) reduces noise but still exhibits considerable residuals and less clear waveform features, DnCNN (Fig. 12c) shows better noise reduction in some areas but suffers from residual noise and compromised waveform continuity, and DeepDenoiser (Fig. 12d) improves upon U-Net and DnCNN but still has residual noise in certain regions. Compared to these methods, MSARDNet efficiently separates seismic signals from background noise, minimizing interference while retaining important geological information. Additionally, the noise profile separated by MSARDNet (Fig. 12i) exhibits no strip-like or phase-continuous structural features, indicating that the model does not misclassify valid seismic signals as noise for filtering, in contrast to U-Net (Fig. 12f) and DnCNN (Fig. 12g), whose noise profiles still retain obvious event structures; while DeepDenoiser (Fig. 12h) visually preserves amplitude characteristics relatively well, it leaves a higher amount of residual noise.

Application in phase picking

To verify the practical value of MSARDNet-denoised data in downstream earthquake monitoring, we focused on phase picking (P-wave/S-wave onset phase picking, which serves as the foundation for earthquake location and magnitude calculation) and conducted systematic comparative experiments involving noisy signals, signals denoised by MSARDNet, and two current mainstream phase identification models—PhaseNet and EqTransformer. The experimental data consisted of the 1056 noisy signals and MSARDNet-denoised signals used in “Field seismic data application”. Both tools adopted pre-trained models publicly released by their development teams, with unified hyperparameter settings: the picking threshold was set to 0.3, and the picking time window was limited to ± 0.5 s. Supplementary Fig. S3 intuitively demonstrates the improvement effect of MSARDNet denoising on phase picking accuracy.

We used RMSE (temporal accuracy), Precision (anti-false picking), Recall (anti-missed picking), and F1-score (comprehensive reliability) as core evaluation metrics. Results (Table 9) showed significant improvements in all metrics for both tools after MSARDNet denoising. For P-waves, PhaseNet’s RMSE decreased by 25.8% (0.31→0.23 s) and EqTransformer’s by 34.5% (0.29→0.19 s), with both reaching an F1-score of 0.94. For S-waves (more noise-susceptible), PhaseNet’s RMSE dropped by 26.8% (0.56→0.41 s) and EqTransformer’s by 30.8% (0.52→0.36 s), alongside notable gains in Precision and Recall. The EqTransformer-MSARDNet combination achieved the best performance.

These findings confirm that MSARDNet’s denoising stably enhances phase picking performance for both tools and both P/S-waves, and its signal-quality optimization translates to downstream picking gains—providing critical support for the reliability of earthquake location and magnitude calculation.

Conclusion

The MSARDNet denoising model effectively removes diverse noise (broadband Gaussian, low-frequency baseline drift, impulsive, and non-stationary mixed noise) from seismic signals. Validated across multiple experiments and datasets, it shows strong robustness and denoising capabilities in complex environments—excelling in improving SNR, reducing RMSE, and enhancing correlation coefficients. Its integration of depthwise separable convolutions, an improved channel attention mechanism, and the ResDC module gives it significant advantages in seismic denoising.

In practice, MSARDNet significantly enhances seismic signal quality by preserving valid components and minimizing noise interference, offering broad application prospects and practical value in seismic processing, with strong support for related research and practices. MSARDNet can be flexibly extended to 3D seismic data processing scenarios: upgrading the depthwise separable convolutions and ResDC modules to 3D structures or adopting a 3D patch block processing strategy enables adaptation to the spatial features of 3D data; in addition, the transfer learning mode based on pre-trained weights allows it to quickly adapt to new tasks such as time-series signal denoising through small-sample fine-tuning, reducing the cost of scenario transfer.

Data availability

The Stanford Earthquake Dataset (STEAD) is a publicly available dataset that can be downloaded from the official website of the Stanford Earthquake Dataset. This dataset is a global seismic signal dataset specifically designed for artificial intelligence. The Diting-data set is provided by China Earthquake Networks Center, National Earthquake Data Center. (http://data.earthquake.cn). Other relevant data can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Bayram, H., Dogan, R., Şahin, T., Akdis, C. A. & Ü. A. & Environmental and health hazards by massive earthquakes. Allergy 78, 2081–2084 (2023).

Mavrouli, M., Mavroulis, S., Lekkas, E. & Tsakris, A. The impact of earthquakes on public health: a narrative review of infectious diseases in the post-disaster period aiming to disaster risk reduction. Microorganisms 11, 419 (2023).

Jackson, J., McKenzie, D. & Priestley, K. Relations between earthquake distributions, geological history, tectonics and rheology on the continents. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 379, 20190412 (2021).

Abudeif, A. M. et al. Evaluation of engineering site and subsurface structures using seismic refraction tomography: a case study of abydos site, Sohag governorate, Egypt. Appl. Sci. 13 (4), 2745 (2023).

Mohammed, M. A., Abudeif, A. M. & Abd El-aal, A. K. Engineering geotechnical evaluation of soil for foundation purposes using shallow seismic refraction and MASW in 15th Mayo, Egypt. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 162, 103721 (2020).

Abudeif, A. M. et al. Dynamic geotechnical properties evaluation of a candidate nuclear power plant site (NPP): P-and S-waves seismic refraction technique, North Western Coast, Egypt. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 99, 124–136 (2017).

Abudeif, A. M. Seismotectonic analysis of Hamada oil pool, Libya, using Landsat and seismic data. Arab. J. Geosci. 8 (9), 6811–6834 (2015).

Dittmann, T., Liu, Y., Morton, Y. & Mencin, D. Supervised machine learning of high rate GNSS velocities for earthquake strong motion signals. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth. 127, e2022JB024854 (2022).

Xiong, M., Li, Y. & Ning, W. Random-noise attenuation for seismic data by local parallel radial-Trace TFPF. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 52, 4025–4031 (2014).

Li, F., Sun, F., Liu, N. & Xie, R. Denoising seismic signal via resampling local applicability functions. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 19, 1–5 (2022).

Dong, X. et al. Seismic shot gather denoising by using a supervised-deep-learning method with weak dependence on real noise data: a solution to the lack of real noise data. Surv. Geophys. 43, 1363–1394 (2022).

Feng, Q. & Li, Y. Denoising deep learning network based on singular spectrum analysis—DAS seismic data denoising with multichannel SVDDCNN. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 60, 1–11 (2022).

Dong, X., Li, Y., Zhong, T., Wu, N. & Wang, H. Random and coherent noise suppression in DAS-VSP data by using a supervised deep learning method. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 19, 1–5 (2022).

Ding, M., Zhou, Y. & Chi, Y. Self-attention generative adversarial network interpolating and denoising seismic signals simultaneously. Remote Sens. 16, 305 (2024).

Ma, H. et al. Noise reduction for desert seismic data using spectral kurtosis adaptive bandpass filter. Acta Geophys. 67, 123–131 (2019).

Li, Z., Sun, N., Zeng, T., Zhang, H. & Tian, J. Adaptive Subtraction based on the matching filter with three frequency bands of modeled multiples for removing seismic multiples. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 20, 1–5 (2023).

Duncan, G. & Beresford, G. Median filter behaviour with seismic data1. Geophys. Prospect. 43, 329–345 (1995).

Liu, Y., Liu, C. & Wang, D. A 1D time-varying median filter for seismic random, spike-like noise elimination. Geophysics 74, V17–V24 (2009).

Liu, Q. M. et al. Face super-resolution reconstruction based on self-attention residual network. IEEE Access 8, 4110–4121 (2020).

Lin, H., Li, Y. & Yang, B. Recovery of seismic events by time-frequency peak filtering. in IEEE International Conference on Image Processing V-441-V–444 (IEEE, San Antonio, TX, USA, 2007). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICIP.2007.4379860

Tian, Y., Li, Y. & Baojun Y. Variable-eccentricity hyperbolic-trace TFPF for seismic random noise attenuation. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 52, 6449–6458 (2014).

Wu, N., Li, Y., Ma, H. & Xuechun X. Intermediate-frequency seismic record discrimination by radial trace time–frequency filtering. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 11, 1280–1284 (2014).

Liu, W., Cao, S. & Chen, Y. Seismic time–frequency analysis via empirical wavelet transform. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 13, 28–32 (2016).

Yu, Z., Abma, R., Etgen, J. & Sullivan, C. Attenuation of noise and simultaneous source interference using wavelet denoising. Geophysics 82, V179–V190 (2017).

Yuan, Y., Li, Y. & Zhou, S. Multichannel statistical broadband wavelet deconvolution for improving resolution of seismic signals. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 59, 1772–1783 (2021).

Mousavi, S. M. & Langston, C. A. Adaptive noise estimation and suppression for improving microseismic event detection. J. Appl. Geophys. 132, 116–124 (2016).

Mao, X. A. Concentrated time-frequency method for reservoir detection using adaptive synchrosqueezing transform. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 19, 1–5 (2022).

Herrmann, F. J., Wang, D., Hennenfent, G. & Moghaddam, P. P. Curvelet-based seismic data processing: a multiscale and nonlinear approach. Geophysics 73, A1–A5 (2008).

Górszczyk, A., Malinowski, M. & Bellefleur, G. Enhancing 3D post-stack seismic data acquired in hardrock environment using 2D curvelet transform. Geophys. Prospect. 63, 903–918 (2015).

Kutyniok, G., Lim, W. Q. & Reisenhofer, R. ShearLab 3D: faithful digital shearlet transforms based on compactly supported shearlets. ACM Trans. Math. Softw. 42, 1–42 (2016).

Karbalaali, H., Javaherian, A., Dahlke, S., Reisenhofer, R. & Torabi, S. Seismic channel edge detection using 3D shearlets—a study on synthetic and real channelised 3D seismic data. Geophys. Prospect. 66, 1272–1289 (2018).

Labate, D., Lim, W. Q., Kutyniok, G. & Weiss, G. Sparse multidimensional representation using shearlets. in (eds Papadakis, M., Laine, A. F. & Unser, M. A.) 59140U San Diego, California, USA, (2005). https://doi.org/10.1117/12.613494

Gómez, J. L. & Velis, D. R. A simple method inspired by empirical mode decomposition for denoising seismic data. Geophysics 81, V403–V413 (2016).

Han, J. & Van Der Baan, M. Microseismic and seismic denoising via ensemble empirical mode decomposition and adaptive thresholding. Geophysics 80, KS69–KS80 (2015).

Li, J., Li, Y., Li, Y. & Qian, Z. Downhole microseismic signal denoising via empirical wavelet transform and adaptive thresholding. J. Geophys. Eng. 15, 2469–2480 (2018).

Zhang, S. & Li, Y. Seismic exploration desert noise suppression based on complete ensemble empirical mode decomposition with adaptive noise. J. Appl. Geophys. 180, 104055 (2020).

Dragomiretskiy, K. & Zosso, D. Variational mode decomposition. IEEE Trans. Signal. Process. 62, 531–544 (2014).

Yu, S. & Ma, J. Complex variational mode decomposition for slop-preserving denoising. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 56, 586–597 (2018).

Yao, X., Zhou, Q., Wang, C., Hu, J. & Liu, P. An adaptive seismic signal denoising method based on variational mode decomposition. Measurement 177, 109277 (2021).

Gan, S. et al. Structure-oriented singular value decomposition for random noise attenuation of seismic data. J. Geophys. Eng. 12 (2), 262–272 (2015).

Rekapalli, R. et al. 3D seismic data de-noising and reconstruction using multichannel time slice singular spectrum analysis. J. Appl. Geophys. 140, 145–153 (2017).

LeCun, Y., Bengio, Y. & Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature 521, 436–444 (2015).

Si, X. & Yuan, Y. Random noise Attenuation based on residual learning of deep convolutional neural network. SEG Tech. Program. Expanded Abstracts 1986–1990 ((2018). Society of Exploration Geophysicists, Anaheim, California, 2018). doi:https://doi.org/10.1190/segam2018-2985176.1.

Zhao, Y., Li, Y., Dong, X. & Yang, B. Low-frequency noise suppression method based on improved DnCNN in desert seismic data. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 16, 811–815 (2019).

Zhu, W., Mousavi, S. M. & Beroza, G. C. Seismic signal denoising and decomposition using deep neural networks. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 57, 9476–9488 (2019).

Zhang, R. et al. Low-frequency swell noise suppression based on U-Net. Appl. Geophys. 17, 419–431 (2020).

Saad, O. M. et al. Unsupervised deep learning for single-channel earthquake data denoising and its applications in event detection and fully automatic location. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 60, 1–10 (2022).

Wang, H. & Zhang, J. A deep learning approach for suppressing noise in livestream earthquake data from a large seismic network. Geophys. J. Int. 233, 1546–1559 (2023).

Cui, Y. et al. Ground-truth-free deep learning for 3D seismic denoising and reconstruction with channel attention mechanism. Geophysics 89 (6), V503–V520 (2024).

Yu, W. et al. MAE-GAN: a novel strategy for simultaneous super-resolution reconstruction and denoising of post-stack seismic profile. ArXiv Preprint. arXiv, 240519767 (2024).

Zhu, D. et al. Diffusion model for DAS-VSP data denoising. Sensors 23 (20), 8619 (2023).

Cui, Y., Waheed, U. B. & Chen, Y. K. Unsupervised deep learning for DAS-VSP denoising using attention-based deep image prior. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 63, 1–4 (2025)

Saad, O. M., Ravasi, M. & Alkhalifah, T. Noise Attenuation in distributed acoustic sensing data using a guided unsupervised deep learning network. Geophysics 89, V573–V587 (2024).

Liu, D., Wang, Z., Wang, X. & Chen, W. Zero-shot denoising for DAS-VSP data based on conditional diffusion probabilistic models. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 63, 1–11 (2025).

Ding, L. et al. Hybrid Multi-Resolution network for DAS data denoising. PLoS One. 20 (6), e0325299 (2025).

Qiao, X. et al. A method for data denoising and smoothing based on DAS VSP. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 74, 1–8 (2025).

Li, F. et al. Swin transformer for seismic denoising. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 21, 1–5 (2024).

Liu, Z. et al. KAN: Kolmogorov-Arnold networks. arXiv Preprint arXiv:2404.19756 (2024).

Chen, G. et al. Unsupervised seismic reconstruction via deep learning with one-dimensional signal representation. Comput. Geosci. 200, 105916 (2025).

Sheng, H. et al. Seismic foundation model: a next generation deep-learning model in geophysics. Geophysics 90 (2), IM59–IM79 (2025).

Mousavi, S. M. et al. STanford earthquake dataset (STEAD): a global data set of seismic signals for AI. IEEE Access 7, 179464–179476 (2019).

Chen, Y. et al. TXED: the Texas earthquake dataset for AI. Seismol. Res. Lett. 95 (3), 2013–2022 (2024).

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgement for the data support from " China Earthquake Networks Center, National Earthquake Data Center. (http://data.earthquake.cn)”.

Funding

This research was funded by Science and Technology Innovation Program for Postgraduate students in IDP subsidized by Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant No. ZY20250321), the Open Fund of Hebei Key Laboratory of Seismic Disaster Instrument and Monitoring Technology (Grant No. FZ224106), and the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2024YFC3017003).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.Y. and L.H.; methodology, L.H.; software, L.H., and L.Q.; validation, L.Q., J.C., and W.L.; formal analysis, W.L.; investigation, J.C.; resources, Z.Y.; data curation, L.H.; writing—original draft preparation, L.H.; writing—review and editing, Z.Y. and L.H.; visualization, L.H.; supervision, J.C.; project administration, Z.Y.; funding acquisition, Z.Y. and L.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yao, Z., Hao, L., Qin, L. et al. Efficient seismic data denoising via multi-scale attention network with depthwise separable and residual dilated convolutions. Sci Rep 16, 2818 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32591-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32591-w