Abstract

Slope stability is a crucial aspect of geotechnical engineering, particularly for landfills where municipal solid waste (MSW) layers are subjected to both static and seismic forces. This study represents the first application of hybrid metaheuristic–neural models to the Barmshour Landfill, introducing an innovative predictive framework capable of guiding real-world design, stability evaluation, and decision-making processes in waste management engineering. Four hybrid models—BBO-MLP, MVO-MLP, VS-MLP, and BSA-MLP—were developed and evaluated using real data from the Barmshour Landfill in Shiraz, Iran. The MVO-MLP model achieved the best performance, with coefficient of determination (R2) values of 0.899 (training) and 0.898 (testing), and corresponding RMSEs of 77.60 and 89.44. The results demonstrate that hybrid metaheuristic–neural models can capture complex slope behaviors more effectively than traditional approaches. The primary advancement of this research lies in its systematic comparison of multiple hybrid algorithms and their demonstration of robustness under variable conditions. Practically, the proposed framework provides engineers with a more reliable and adaptive tool for assessing landfill stability and managing geotechnical risks. These findings highlight the growing potential of intelligent hybrid systems to support safer and more data-driven waste management infrastructure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Municipal Solid Waste refers to all the discarded materials produced by households, commercial and institutional establishments, and other activities within urban limits, which usually include, but are not limited to, food waste, paper, plastics, textiles, metals, and glass. MSW is highly heterogeneous, containing biodegradable and non-biodegradable components and materials that are either recyclable or reusable. Knowledge of MSW composition and properties is crucial to landfill designers who need to plan and design a waste containment system that ensures environmental safety and long-term stability. The most important properties include waste density, moisture content, decomposition potential, and gas generation, as these characteristics significantly affect landfill capacity, leachate management, gas extraction, and long-term settlement. Proper management of MSW is crucial for minimizing environmental impacts, including groundwater contamination and greenhouse gas emissions, ensuring compliance, and addressing sustainability concerns. It is important to note that burying rubbish in a landfill or dump site is the final functional component of MSW management1,2. This is the most commonly used technique for disposing of garbage. One of the main concerns in geoenvironmental engineering is the planning, construction, and maintenance of a safe landfill3,4. Among these issues are landfill slope collapse, excessive settlement, leachate leakage into the environment, improper operation of the leachate collecting system, and employee safety5,6. The general stability of the slopes is a key consideration when building an open dump site. MSW slope instability may have hazardous effects on the surrounding ecosystem and put nearby residents and workers at risk. Zhang et al.7 identified the primary causes of landfill instability by reviewing landfill slope instability data from 22 different counties over the past 40 years. High leachate levels, poor MSW compaction, limited foundation bearing capacity, low shear strength of the liner–MSW interface, and the rapid release and consequent deflagration of landfill gas were among these causes.

Conventional landfill construction methods, in which waste is unloaded and leveled by trucks and construction vehicles with minimal supervision, have several significant disadvantages, especially regarding slope stability. One primary concern is the lack of control over the compaction of waste materials. Without proper monitoring or compaction techniques, waste may settle unevenly, leading to weak or unstable areas that can compromise the landfill’s overall integrity8. Inadequate compaction and poor distribution of waste increase the risk of slope failures, which may result in landslides, particularly if the landfill’s slopes exceed critical angles or contain organic or liquid-rich materials that weaken the structure9. Additionally, the conventional approach often lacks a detailed geotechnical investigation or ongoing monitoring of the landfill’s physical properties. This absence of oversight can lead to long-term instability, affecting the surrounding environment and public safety. The absence of advanced monitoring also hinders the detection of early signs of potential hazards, such as excessive leachate generation or methane emissions, which are critical in preventing further degradation of the landfill and surrounding land.

On the other hand, new technologies in landfill construction, such as advanced compaction techniques, geotechnical monitoring systems, and engineered slopes, offer numerous benefits over traditional methods. One of the primary advantages is the ability to monitor and control waste compaction more precisely10. Techniques such as geosynthetics, compaction aids, and real-time monitoring ensure waste is evenly distributed and compacted to the required densities, significantly enhancing slope stability and reducing the risk of landslides. This is particularly important in sites with challenging geological conditions or high waste volumes. Furthermore, new technologies enable better monitoring of landfill behavior over time. Geotechnical sensors, such as piezometers, inclinometers, and ground-penetrating radar, can detect potential shifts in the waste mass, subsidence, or slope movements before they become critical. This proactive approach enables operators to manage the landfill more effectively and prevent hazardous situations. Enhanced data analytics and machine learning can predict long-term settlement and stability trends, enabling more informed planning for both construction and closure phases. Additionally, advanced materials such as geotextiles and geomembranes help contain leachate and methane, thereby improving both environmental safety and the landfill’s lifespan.

Landfill slope stability has been commonly examined by combining limit-equilibrium-based techniques, numerical methods, and back analysis of failed slopes under static and dynamic loading conditions. Limit equilibrium methods are widely used due to their simplicity and the ability to model failure mechanisms through a factor-of-safety calculation for assumed failure surfaces11. However, they often rely on simplifying assumptions. Numerical techniques, such as the finite element or finite difference methods, can provide much more detail by simulating stress-strain behavior and capturing the complex interactions among landfill waste, liners, and soil. These are particularly useful in assessing stability under seismic or dynamic conditions. On the other hand, a back analysis of failed slopes would allow the exact causes of failure to be ascertained by rebuilding up to the point of failure, thereby improving data on parameters and ensuring the validity of the models. These techniques, when combined, contribute to a comprehensive approach for ensuring structural stability in landfills and slopes2,12. Gunarathne et al.13 categorized landfill failures into two types: uncontrolled/open landfills and engineered/sanitary landfills. Jahanfar14 examined failed open dumps and found that the absence of a cover layer to prevent rainwater penetration and a lack of compaction led to failure predominantly as flow slides in the MSW body. In this regard, the shear behavior of MSW materials is one of the most important issues related to landfill site design, as it directly controls slope stability under both static and seismic loading conditions. In addition, the critical nature of the heterogeneous MSW composition, which modifies regional waste profiles due to climate and operational practices, results in significant variability within the Mohr-Coulomb shear strength parameters: cohesion, c, and the internal friction angle, Φ15. These parameters essentially control the shear resistance of the material and are a basic input for stability analyses. The presence of multiple testing methodologies further adds to the complexity of standardization; thus, a site-specific characterization study becomes imperative for a designer to adopt, by realistically applying back analysis to obtain in-situ shear behavior. This variability is of special significance in seismic assessments because MSW response to dynamic impulses differs significantly from that of conventional soil and may behave differently under earthquake conditions that affect slope stability2,16. These differences have prompted researchers to examine the shear strength behavior of MSW while considering the following variables: age, composition and breakdown, loading rate, confining pressure, stress route, waste temperature, and variations in test technique and equipment. The shear strength behavior of municipal solid waste is complicated by its heterogeneity, which is influenced by waste composition, degradation stage, and operating conditions. MSW usually exhibits shear strength which can be defined by Mohr-Coulomb parameters: cohesion, c, and internal friction angle, Φ17. These parameters are highly variable: Φ typically lies between 20° and 40°, while cohesion may range from 5 to 25 kPa depending on waste density, moisture content, and compaction. Biodegradation alters the mechanical properties of MSW with time, which may result in a loss of shear strength due to settlement and/or changes in material composition18. This non-linear stress-strain behavior, combined with time-dependent characteristics, makes MSW particularly challenging for stability analysis and is often subjected to dynamic loading during earthquakes. This assessment typically requires site-specific testing and back analysis to account for localized conditions, ensuring the appropriate design of landfill slopes. Notably, the shear strength of MSW varies significantly with age due to various physical, chemical, and biological processes, including biodegradation. In younger MSW (less than 5 years old), the material is primarily constituted of fresh, undecomposed waste with higher organic content, leading to relatively higher cohesion due to binding from fibrous materials and moisture18. The internal friction angle exhibits a similar trend—a medium value of around Φ lies between 25° and 30°, depending on its density and particle interlocking. Still, with fast settling and particle decomposition, the mechanical behavior undergoes significant changes. In intermediate-aged MSW (e.g., material in the 5- to 10-year range), active decomposition processes break down organics and reduce cohesion as the binding materials decompose. Friction angles may be somewhat higher, typically around 30°–35°, reflecting a much larger proportion of inorganic fractions, which consist of plastics and inert materials, providing increased resistance to shear. Settlement rates slow but continue to increase significantly, and overall, properties have somewhat stabilized relative to the younger MSW. Lastly, most organic matter has been decomposed in older MSW (over 10 years), and mainly inert materials are left. Cohesion is still very low due to the loss of the organic binding agents. Still, the friction angle is increased, often above 35°, because of long-term densification and compaction effects. Increased stability relates to a decrease in the changes concerning decomposition; therefore, this MSW becomes more predictable in shear strength for engineering purposes.

Slope stability analysis is crucial in geotechnical engineering to ensure the safety and functionality of earth structures, such as landfills, embankments, dams, and slopes. Catastrophic failures, environmental harm, and large financial losses can all result from instability5,19. Material characteristics, geometry, groundwater conditions, and seismic activity are some variables that affect slope stability. Even though they are fundamental, traditional deterministic techniques sometimes struggle to account for uncertainties in these parameters, particularly in complex loading situations such as seismic occurrences20. Previous studies have applied conventional AI/ML models such as support vector machines, decision trees, and standard neural networks to slope stability analysis; however, this work advances the field by integrating metaheuristic–neural network hybrids, which offer improved accuracy and robustness in capturing complex geotechnical behaviors21,22. Kumar et al.23 applied advanced neural network models (DNN, CNN, and RNN) trained on 3D slope stability data from the Mount St. Helens case, demonstrating that DNN achieved the highest predictive accuracy (R2 = 0.999 training; 0.997 testing) for factor of safety estimation under both seismic and non-seismic conditions. Kumar et al.24 employed the generalized Hoek–Brown criterion to develop stability charts for rock slopes (27 m height) under static and seismic conditions, revealing that the factor of safety decreases with increasing dimensionless stress parameters and that failure mode transitions from base to toe with steeper slope angles. Kumar et al.25 applied advanced machine learning models (XGBoost, RF, GBM, and deep learning) to predict the bearing capacity of pre-bored grouted planted nodular piles using 81 Vietnamese case histories, showing that XGBoost achieved the highest accuracy (R2 = 0.91) and can effectively support safe and economical pile design. Tiwari and Das26 demonstrate the use of machine learning and explainable AI techniques to reliably classify soil liquefaction susceptibility from field data, with boosting-based ensemble models achieving high accuracy and SHAP/LIME providing interpretable insights into key geotechnical factors such as groundwater level and peak ground acceleration. Tiwari et al.27 apply ensemble machine learning algorithms, including XGBoost, Bagging, and Random Forest, to predict soil liquefaction susceptibility from unbalanced in-situ test datasets, highlighting key soil and seismic parameters and providing an interpretable GUI for practical geotechnical applications. The prediction of bearing capacity in pile foundations has traditionally relied on empirical methods and geotechnical testing, which often lack precision under varying soil conditions. Recent studies have explored deep learning approaches, demonstrating improved accuracy by leveraging large datasets and complex nonlinear relationships to model pile-soil interactions effectively28.

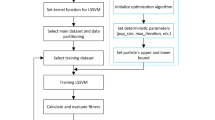

In contrast, reliability-based design for strip footings under inclined loading has historically depended on deterministic methods, often overlooking uncertainties in soil properties and loading conditions. Recent research has advanced this field by employing hybrid Least Squares Support Vector Machine (LSSVM) machine learning models, which integrate optimization techniques to enhance prediction accuracy and account for probabilistic variations in geotechnical design29. In a separate study, fly ash (FA)-based high-strength concrete (HSC) offers environmental benefits and improved performance as a substitute for Portland cement, although its design is complex due to variables such as fly ash percentage, water content, and superplasticizer dosage. This study developed a predictive tool using six AI models, with the Deep Neural Network (DNN) excelling (R2 = 0.89, VAF = 88.3%, RMSE = 0.06, RSR = 0.31), providing reliable compressive strength predictions and promoting sustainable, cost-efficient mix designs30.

Although they need computationally demanding analysis techniques, probabilistic approaches have improved risk quantification. Metaheuristic optimization has become a powerful alternative for addressing complex engineering problems31,32. These algorithms effectively search and exploit the solution space by mimicking natural processes such as biological evolution, swarm intelligence, or physical phenomena33. Metaheuristics are versatile, do not require derivative knowledge, and can efficiently handle nonlinear, multi-modal problems in contrast to conventional optimization techniques34. By adjusting crucial factors, metaheuristics in slope stability analysis can adjust the Factor of Safety (FS) or settlement, resulting in more accurate and effective forecasts under various conditions. Strong tools for investigating global optima in nonlinear, multi-modal FS optimization problems are provided by metaheuristic algorithms such as Biogeography-Based Optimization (BBO), Backtracking Search Optimization Algorithm (BSA), Multi-verse Optimization (MVO), and Vortex Search Algorithm (VS), which improve prediction accuracy. This paper aims to integrate modern metaheuristic optimization techniques to improve the efficiency and dependability of slope stability assessments for the Barmshour Landfill. Four cutting-edge algorithms—Biogeography-Based Optimization (BBO), Backtracking Search Optimization Algorithm (BSA), Multi-verse Optimization (MVO), and Vortex Search (VS)—are implemented using data from the original study in order to estimate the maximum settlement on landfill slopes. Applying these metaheuristic techniques to a real-world geotechnical problem and providing a comparative evaluation of how well they handle intricate, probabilistic scenarios is what makes this study innovative. In addition to addressing the drawbacks of conventional methods, this novel methodology offers a strong foundation for next slope stability research in unpredictable settings.

Methodology

Case study

The Barmshour Landfill, located near Shiraz, Iran, has been the subject of studies examining its environmental impacts and slope stability. The landfill’s design incorporates various engineering measures to address the concerns of static and seismic slope stability. Research has included probabilistic analyses of the landfill’s performance under static conditions and seismic loading. The study emphasizes that an accurate assessment of the shear strength characteristics of MSW is critical for evaluating slope stability in such sites. One significant challenge for the landfill is the heterogeneity of MSW, which complicates the determination of accurate strength parameters. In 2013, a slope failure occurred in a portion of the landfill35. Recently, a designed cell including geosynthetics and a leachate and gas collecting system was added to the landfill.

The view of the Barmshour Landfill (a) top view taken from Falamaki et al.2, (b) 2025.

MSW mechanical properties

The values of E and φ used in the PLAXIS 2D simulations were calibrated based on the reported geomechanical properties from Table 1. These MSW properties are adjusted to reflect the actual in-situ conditions of the Barmshour Landfill, as previously studied by Falamaki et al.2. Indeed, Table 1 classifies the most common MSW material properties according to MSW age, which has been divided into three categories: (i) Young (< 5 years), (ii) Intermediate (5–10 years), and (iii) Old (> 10 years). The following mechanical parameters are included: Young’s Modulus (E), Cohesion Strength (C), Internal Friction Angle (φ), and Poisson’s Ratio. For the > 10-year-old waste, Young’s Modulus increases considerably to 15,000–30,000 kPa, representing increased stiffness compared with the young MSW, which has a modulus of only 1000–5000 kPa. Cohesion strength also increased with age, from 5 to 10 kPa for young waste to 15–25 kPa for old waste, though 20 kPa is generally assumed. Consequently, the internal friction angle varies from 21° to 25° in the case of young waste to 30°–35° in old waste. This suggests that MSW shear resistance increases due to decomposition and compaction. Poisson’s ratio measures the lateral strain within the range of 0.2–0.3 for the old waste, which is lower than the lateral deformation ranging from 0.3 to 0.35 for the young waste. These trends indicate the influence of waste age on material behavior, such as greater stability and higher mechanical strength for older MSW, resulting from physical and chemical transformations over time. The data is paramount for assessing stability in landfills and slope design Table 1). To check the validity of the data, several laboratory soil tests (samples taken from Barmshor landfill), along with images of sample preparation and laboratory procedures, are provided in Figs. A1 and A2 of the supplementary material to give readers the necessary details for reproducibility.

In this study, the dataset for the Barmshour Landfill was split into training and testing sets using a 70:30 ratio, ensuring robust model evaluation. Before splitting, data normalization was performed using min-max scaling to transform values into a [0, 1] range, addressing the varying scales of MSW properties and force-displacement data. This standardization enhances model convergence and performance. A 70:30 split was applied randomly to maintain representativeness, with 70% used to train models such as MVO-MLP and BSAMLP and 30% reserved for unbiased testing to validate predictive accuracy.

During the finite element method (FEM) analysis, the software exhibited numerical instability when cohesion (c) values below 20 kPa (approximately 0.2 kg/cm2) were assigned to the MSW material model. Below this threshold, the solution process failed to converge under the applied loading conditions required to simulate settlement behavior. This limitation is related to the lower bound of shear strength that the solver can accommodate while maintaining equilibrium and avoiding singularities in the stiffness matrix. Consequently, a cohesion value of 20 kPa was adopted as the minimum feasible value for all numerical simulations. To contextualize the magnitude of this cohesion value, it is essential to note that 20 kPa corresponds to approximately 0.2 kg/cm2, which is remarkably small when compared to typical structural materials. For instance, even low-strength concrete exhibits a compressive yield strength (fy) of approximately 210 kg/cm2, while higher-strength concrete can exceed 1000 kg/cm2. Thus, the chosen cohesion value represents an extremely weak bonding condition within the waste mass—several orders of magnitude lower than that of engineered materials—yet sufficient to maintain numerical stability in the FEM solver. This comparison highlights that the adopted cohesion does not artificially stiffen the model or exaggerate shear resistance; rather, it provides a physically reasonable and computationally stable lower bound for the waste material under study. Because the FEM software could not stably process lower cohesion values, it was not possible to conduct a meaningful parametric investigation of the influence of c within this study. Therefore, c = 20 kPa was treated as a constant throughout all analyses. At the same time, other parameters (such as the internal friction angle, unit weight of waste, and geometry) were varied to evaluate their relative influence on deformation and stability. Future work could address this limitation by employing advanced constitutive models or customized numerical implementations capable of handling lower shear-strength thresholds, thereby enabling a more detailed assessment of cohesion variability in heterogeneous MSW materials.

Numerical simulation

The finite element method (FEM) simulations for the Barmshour Landfill stability analysis were conducted using PLAXIS 2D software (Version 8.5), a robust geotechnical tool for modeling complex soil-structure interactions. The model simulates a 2D cross-section of the landfill slope (as depicted in Fig. 2), incorporating the addition of two new MSW layers (each 10 m thick) on top of existing waste, under both static and seismic loading conditions. The domain spans 180 m horizontally and 60 m vertically, with a slope inclination of 1:3 (vertical: horizontal) to replicate the site-specific geometry. The mesh employs a 15-node triangular element type with medium density (approximately 5000 elements, refined to 0.5 m near the crest and interfaces) to achieve convergence while balancing computational efficiency. A sensitivity analysis confirmed that further refinement beyond this density yielded < 1% change in displacement outputs. The constitutive model adopted for MSW layers is the Mohr-Coulomb (MC) criterion, suitable for granular-like waste behavior under undrained conditions, capturing shear strength via cohesion (c), friction angle (φ), and dilation angle (ψ = 0°). This choice aligns with the literature for MSW, where hyperbolic models, such as Hardening Soil, were deemed overly complex for preliminary stability assessments without extensive triaxial data. Underlying soil layers (assumed to be clayey) also utilize MC, with drained parameters derived from site borings. Drainage conditions are modeled as undrained during rapid seismic events (total pore pressure buildup) and partially drained for static loading (permeability k = 10−7 m/s vertically, 10−8 m/s horizontally). Boundary conditions include fixed horizontal displacements at the base and the left/right sides (roller supports), with vertical fixation only at the base to simulate a semi-infinite domain. Material properties for MSW layers, categorized by age (Young: < 5 years; Intermediate: 5–10 years; Old: >10 years), are compiled from literature33,34,35 and validated via laboratory tests on Barmshour samples (detailed in Supplementary Fig. A1). Unit weights (γ) reflect compaction: 12–16 kN/m2 for young waste, increasing with age due to decomposition. Cohesion and friction angles increase with age, enhancing shear resistance, while Poisson’s ratio (ν) decreases, indicating reduced lateral deformability in older waste. Table 2 summarizes these properties, including MC-specific inputs like dilation angle and permeability. Seismic loading applies a pseudo-static acceleration of 0.3 g (site-specific PGA from Iranian seismic zoning), factored into horizontal forces at the crest. Static analysis precedes seismic analysis via a staged construction sequence: excavation, layer placement (labeled 1–16 in Fig. 2), and loading. Safety factors were computed using the φ-c reduction method, targeting a factor of safety (FOS) greater than 1.3 for stability. This setup ensures reproducibility, with input files available upon request. The MC model’s simplicity facilitates the integration of hybrid AI for parameter optimization, as explored in subsequent sections. The study further explores the impact of two new MSW surcharges, each 10 m high, on the landfill’s stability (Fig. 2). PLAXIS 2D excels at modeling such scenarios, offering precise simulation of nonlinear material behavior, stress-strain relationships, and layer interactions. Its advanced constitutive models accurately represent MSW heterogeneity, enabling a detailed understanding of slope stability under dynamic conditions and varying mechanical properties.

The finite element modeling (FEM) of the Barmshour Landfill was conducted using PLAXIS 2D (Version 8.5) to simulate the mechanical behavior of MSW layers under surcharge loading, providing the foundation for our hybrid AI predictive framework. A total of 58 distinct slope configurations were modeled, each reflecting variations in MSW layer properties based on age categories outlined in Table 1 (e.g., Young: < 5 years, E = 1000–5000 kPa, φ = 21–25°; Intermediate: 5–10 years, E = 5000–15000 kPa, φ = 25°–30°; Old: >10 years, E = 15,000–30,000 kPa, φ = 30°–35°). These properties, including Young’s Modulus (E), cohesion (c), friction angle (φ), Poisson’s ratio (ν), and permeability, were calibrated using a combination of empirical data from borehole samples and laboratory tests (Supplementary Fig. A1) and theoretical ranges from literature33,34,35. Each simulation incorporated the Mohr-Coulomb criterion, with a 15-node triangular mesh (medium density, ~ 5000 elements) and undrained drainage conditions to capture pre-failure settlement under new surcharge loads applied to two 10 m MSW layers (Fig. 2). Boundary conditions included fixed horizontal displacements at the base and roller supports on vertical sides, with seismic loading simulated at 0.3 g. The input variables for each of the 58 slopes included layer thickness (10 m), unit weight (12–16 kN/m2), and geomechanical parameters, as listed in Table 1, with surcharge loads incrementally applied to record settlement responses. Settlement data, collected at points A, B, and C (shown in Fig. 2), were recorded after the surcharge application, ensuring that measurements reflected high displacement scenarios just before failure—a critical focus of this study. This process generated a comprehensive database that aggregated settlement outcomes across all configurations. The sampling method systematically varied MSW properties within defined ranges, with field observations used to validate representativeness. For model training and testing, the dataset was split at a fixed 70:30 ratio, with 70% allocated to the training set and 30% to the testing set. This split was applied after min-max normalization to a [0, 1] range, enhancing model convergence. The training set informed the optimization of hybrid AI models (e.g., MVO-MLP, BSAMLP), while the testing set validated performance (e.g., R2 = 0.899, RMSE = 77.60 mm), as detailed later in Figs. 15 and 18. This methodology aligns with our objective of predicting pre-failure settlement, supported by an extensive simulation framework.

Artificial intelligence computation

The goal of combining machine learning methods, such as the Multilayer Perceptron (MLP), with algorithms inspired by nature is to optimize the model’s parameters for the best possible performance on the provided dataset. In machine learning, selecting the appropriate hyperparameters (such as the learning rate, number of neurons, and number of hidden layers in neural networks) significantly influences a model’s performance. Nature-inspired algorithms simulate biological development, swarm behavior, or natural phenomena to solve complex optimization problems. Algorithms inspired by nature effectively search the hyperparameter space to find optimal configurations that reduce errors and increase accuracy. However, issues require further investigation, such as computational demand and sensitivity to algorithmic factors. Nature-inspired algorithms offer a more effective and insightful search method. Biogeography-Based Optimization (BBO), Multiverse Optimizer (MVO), Vortex Search (VS), and Backtracking Search Optimization Algorithm (BSA) are examples of nature-inspired algorithms that help machine learning models, particularly complex ones such as neural networks, avoid being trapped in local minima during training. These algorithms incorporate stochastic features that direct the search process towards better solutions. One of the main advantages of nature-inspired algorithms is their ability to balance exploration (searching through a wide range of feasible responses) and exploitation (fine-tuning the best-recognized solutions). This is particularly helpful for improving machine learning models, as excessive exploration can result in poor generalization, while excessive exploitation can lead to overfitting. To ensure that only the most important characteristics are included in the machine learning model, feature selection can also be performed using techniques inspired by nature. They can also change the weights of neural networks and other machine learning models to enhance model performance. The cutting-edge field of machine learning in artificial intelligence focuses on developing models and techniques that enable computers to learn from data and perform better without explicit programming39. The foundation of machine learning is a system’s ability to recognize patterns, predict outcomes, and extract knowledge from vast and complex datasets. This interdisciplinary area combines concepts from mathematics, statistics, and computer science to develop self-learning algorithms that are responsive to new data. While unsupervised learning seeks patterns in unlabeled data, supervised learning utilizes annotated datasets to train models. Reinforcement learning emphasizes trial-and-error learning for dynamic decision-making. Numerous sectors utilize machine learning, including banking, natural language processing, image and video recognition, medical diagnostics, and predictive analytics.

Multilayer perceptron (MLP)

The prediction of slope behavior in this study was evaluated using a single-layered feedforward neural network from the Matlab ANN Toolbox. The Levenberg-Marquardt method from the Matlab ANN Toolbox was used to train the ANN network. An artificial neural network (ANN) consists of an input layer, a hidden layer with a sigmoid activation function, and an output layer with a linear output function. Using random initialization improved the accuracy. The sigmoid transfer function of the buried layer can be used to handle nonlinear data. The outcome is between 0 and 1 after the input, which spans from plus to negative infinity, has been compressed40. Equation (1) displays the sigmoid’s activation function:

While the input neurons monitored the data as it changed, the output neurons computed the energy consumed. The optimal model structure was obtained by increasing the number of hidden neurons from 1 to 10. 30% or 70% of the entire data set was used to produce training and test data sets. The network determines the most cost-effective weights during training. The model iteration that best fit the data was identified using a cost function method. The training was stopped after the error reduction failed six times to avoid overfitting. McCulloch and Pitts41 were the first to propose the concept of an ANN. Because ANNs may map parameters nonlinearly, researchers have proposed a variety of architectures for different application scenarios. The Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) is the most commonly used form of the artificial neural network due to its high representational capacity, flexible construction, and ability to handle large datasets42. MLPs are often referred to as feedforward neural networks or generic approximators because they are trained using backpropagation43. They can anticipate almost any input-output method thanks to their “neurons,” which serve as processing units. The full MLP structure used in this study is illustrated in Fig. 3a, comprising three distinct layers: an input layer, a hidden layer, and an output layer. Strong neural connections exist between adjacent layers44. For the current study, the optimized MLP structure was found to be 10 × 4 × 1 (Fig. 3a). The prediction performance (output) of the proposed optimized MLP structure and the best validation performance for the proposed MLP (5402.86 at epoch 18) are also illustrated in Fig. 3b and c, repectively.

Development of hybrid metaheuristic algorithms (training MLP)

The hybridization of metaheuristic algorithms for training MLPs enables combining the strengths of multiple optimization techniques to overcome drawbacks, including entrapment in local optima, slow convergence, and high computational costs. Genetic algorithm (GA), Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), and Ant Colony Optimization (ACO) are often hybridized with other methods, such as SA or DE, to exploit their complementary strengths. These hybrids enable better exploration and exploitation of the search space, resulting in improved weight and bias optimization in MLPs. For instance, the fast convergence of PSO can be combined with DE’s robustness against stagnation to ensure that global optima are reached efficiently. By embedding metaheuristics with gradient-based fine-tuning, such as backpropagation, hybrid methods precisely make adjustments after global exploration, thereby combining global search efficiency with local refinement.

Additionally, such algorithms can adaptively adjust learning parameters and scale to complex, high-dimensional data, thereby improving the MLP’s performance in both classification and regression tasks. Their parallelizability further accelerates convergence, making hybrid metaheuristics especially well-suited for large datasets and real-time applications. Thus, hybrid metaheuristics represent a powerful and flexible framework for optimizing MLPs and effectively addressing computational and accuracy-related challenges in diverse machine-learning contexts.

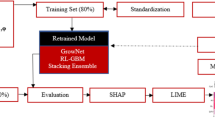

In this sense, since metaheuristic algorithms effectively enhance traditional predictive models, five recently developed algorithms are utilized for MLP. To find the best answer to a specific problem, various search algorithms, including Biogeography-Based Optimization (BBO), Multiverse Optimizer (MVO), Vortex Search (VS), and Backtracking Search Optimization Algorithm (BSA), are investigated. The methods aim to determine the optimal weights and biases for the network using a cost function, given a typical multilayer parity problem. Standard deviations, mean square error, R2, and mean absolute error are the loss functions used to evaluate prediction accuracy. In constructing the hybrid metaheuristic–MLP models (BBO-MLP, MVO-MLP, VS-MLP, and BSA-MLP), a consistent network architecture was employed, consisting of a single hidden layer with six neurons and a Sigmoid activation function. Each model was trained for 1000 iterations to ensure stable convergence. The metaheuristic algorithms controlled the optimization of MLP weights and biases, with population sizes ranging from 50 to 500, depending on the specific algorithm and experiment. For example, the MVO-MLP achieved its best performance at a population size of 350, while other models showed comparable stability at slightly different population settings. Other hyperparameters, such as the learning rate and stopping criteria, were kept constant across models to maintain comparability. These settings were selected based on preliminary tuning and prior experience reported in related studies, providing a balance between computational efficiency and prediction accuracy. The overall methodological framework adopted in this study is summarized in Fig. 4. The workflow begins with the collection and organization of input parameters representing the mechanical behavior of MSW layers, including age, Young’s modulus, cohesion, internal friction angle, and Poisson’s ratio. These parameters were compiled into a structured dataset through field data and simulation results. The prepared data were divided into training and testing subsets and subsequently processed using a hybrid modeling approach. The Artificial Neural Network (ANN) served as the base model, which was optimized through four metaheuristic algorithms—Biogeography-Based Optimization (BBO), Backtracking Search Optimization (BSA), Multi-Verse Optimization (MVO), and Vortex Search (VS)—resulting in four hybrid models (BBO-MLP, BSA-MLP, MVO-MLP, and VSA-MLP). The performance of each model was rigorously assessed using statistical accuracy indicators, including the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), Mean Absolute Error (MAE), coefficient of determination (R2), and Mean Squared Error (MSE). This comprehensive framework ensures a transparent workflow from data preparation to model validation, highlighting the systematic integration of metaheuristic optimization in slope stability prediction.

Biogeography-based optimization (BBO)

Biogeography-based Optimization (BBO)45 is a recently developed evolutionary algorithm inspired by the natural migration and distribution of species across different habitats. In BBO, each habitat is treated as a solution to an optimization problem and has a *habitat suitability index* (HSI) that represents the quality of that solution. The high-HSI habitats share their good features, akin to genes, with low-HSI ones through a migration mechanism. The low HSI habitats are more likely to accept features of immigration, while the high HSI habitats are more likely to exhibit features of emigration. Mutation introduces diversity into the solutions by randomly changing them, preventing early convergence. The balance between migration and mutation enables the algorithm to explore and exploit the search space efficiently. Combined with multilayer perceptrons, BBO can optimize the network’s weights and biases to overcome the well-known drawbacks of traditional gradient-based methods, such as entrapment in local optima and slow convergence. This is due to the migration mechanism, which allows the algorithm to explore the weight space more efficiently and find a better global optimum for the MLP.

Additionally, the mutation operator enhances solution diversity and prevents overfitting, thereby making the model less sensitive to noisy and complex datasets. This hybridization goes further by incorporating backpropagation for fine-tuning after BBO optimization. While BBO focuses on global exploration, backpropagation refines the solution locally by minimizing the gradient of the error. The synergy of BBO with gradient-based learning combines global search with precise local adjustments, making it highly effective for training MLPs. In particular, this combination exhibits excellent performance in applications involving high-dimensional, nonlinear data, for which most conventional training methods have failed. Additionally, due to BBO’s parallelizable structure, computation is accelerated, enabling efficient training of large-scale MLPs. Thus, BBO offers a powerful and flexible methodology that can enhance the overall performance of MLPs across a wide range of machine-learning applications.

Multiverse optimizer (MVO)

The Multiverse Optimizer (MVO), presented by Mirjalili et al.46, is a recently developed metaheuristic algorithm inspired by cosmology, particularly multiverse theory. In the universe of MVO, the candidate solution is a universe, and its quality corresponds to its inflation rate. Higher-quality universes attract resources from lower-quality ones. MVO uses mechanisms such as white holes, black holes, and wormholes to balance exploration and exploitation. White holes enable high-quality universes to share their features, whereas black holes eliminate poor features, while wormholes introduce random changes, thereby boosting diversity and avoiding local optima. MVO, coupled with MLP, optimizes the weights and biases by effectively exploring the weight space and overcoming local minima during training. The randomness in the wormhole provides immunity against overfitting and improves results for nonlinear datasets. Hybridizing MVO with a backpropagation algorithm enables MVO to find a near-optimal setting globally, while backpropagation fine-tunes that solution locally for better accuracy and convergence speed. Optimally performing MVOs serve admirably for a wide range of large-scale, high-dimensional tasks, such as classification and time series prediction. Inherently, MVO’s parallelizability makes it well-suited for resource-intensive application areas. This combination of exploration, exploitation, and fine-graining brings more effective training of multilayer perceptron models.

The multiverse hypothesis posits that multiple Big Bangs have created the universe. The wheel mechanism for transporting universe products and the wormhole (white/black) tunnels connecting two universes are mathematically modeled. A roulette wheel selects the universe with the greatest inflation rate to have a white hole after each repeat, after which the inflation rates of the universes are evaluated. The MVO model may be described mathematically as follows:

Think about the following:

If \(\text{n}\) is the total number of universes (possible solutions) and n is the total number of parameters (variables), then:

If \({\text{r}}_{1}\) consists of an integer from 0 to 1, then \({\text{u}}_{\text{i}}\) is the i-th universe \(\text{NI}\left({\text{u}}_{\text{i}}\right)\)is the i-th universe’s normalized inflation rate, and \({\text{x}}_{\text{i}}^{\text{j}}\) is the i-th world’s j-th parameter.

If one world is connected to the best universe via a wormhole tunnel, the way to get there is as follows:

The lower and upper bounds of the j-th variable are represented by \({\text{lb}}_{\text{j}}\), and the j-th parameter of the best universe by \({\text{x}}_{\text{j}}\). TDR and WEP stand for the worm existence probability and traveling distance rate, respectively, and \({\text{r}}_{2}\), \({\text{r}}_{3}\), and \({\text{r}}_{4}\) are random values between [0, 1]. The WEP and TDR formulae are as follows:

The lowest and highest values are represented by min and max, which are set at 0.2 and 1, respectively; the maximum number of iterations that may be carried out is indicated by L; and the exploitation accuracy over iterations is shown by p, which is set at 6. In this case, l represents the iteration that is now being carried out. The research has a maximum of 500 iterations with 30 universes.

Vortex search (VS)

Based on a single solution, Doğan and Ölmez48 developed Visual Studio. The variable interval (step) size phenomenon, which significantly enhances the efficacy of the search mechanism, distinguishes the VS algorithm. The VS algorithm software considers both weak and strong localities within a neighborhood for the best outcome. Additionally, the algorithm nearly reaches the optimal point when it reacts to the revised solution in an exploitative (strong locality) way to get the best outcome. Therefore, the necessary radius decreases as the number of iterations increases. The VS approach deterministically produces a solution that converges to the global optimization point within the given lower and higher restrictions. The best design for the analog filter group delay and an analog active filter component has been chosen after performance evaluation using the VS technique47. When employing the Vortex Search Optimization (VSO) technique, strong and weak areas substantially impact the effectiveness and usefulness of optimal solutions. Weak and strong locations indicate little and significant modifications to the present response. In contrast, a strong locality is required after the optimization technique effectively converges on the most optimal solution; a weak locality is needed at the start of the search process. The key phases of the VS algorithm search are the radius reduction strategy, candidate solutions, current solution substitution, and primary estimation (VS initialization).

Primary Estimation: The search strategy for the layered vortex pattern is described for the method in question. A two-dimensional nested circle is shown in Fig. 5 to demonstrate the VS approach. Given the initial circumstances, the diameter of the outermost circle serves as the pivot point for the search. Equation 14 may be used to determine the rivet or starting center (,µ − 0.) as follows.

Illustrating the operational search process with the VS’s two-dimensional nested circle model (after Doğan and Ölmez48.

Candidate solutions: According to Eq. 8, following an evaluation of the original answer, neighbor solutions, \({\text{C}}_{\text{i}}\left(\text{X}\right)=\left\{{\text{x}}_{1},{\text{x}}_{2},{\text{x}}_{3},\ldots,{\text{x}}_{\text{k}}\right\},\,\text{k}=1,2,\ldots,\text{n}\) are found using a Gaussian distribution.

where d is the dimension number, i is the count, and n is the number of local optimal points of candidates; ξ and µ are the vectors for a randomly generated variable and the sample mean (selected as the center), respectively. Furthermore, v stands for the covariance matrix that Eq. 16 provides in the way:

where \(\text{I}\) is the identity matrix and s2 is the variance distribution. Equation 10 provides the standard deviation, \({\text{s}}^{2}\), for the initial conditions as follows:

At the beginning step, \({\text{s}}_{0}\) The start radius (r0 for a weak locality) is considered to fully cover the weak proximity in the neighborhood search region.

Current results substitution: When the solution \({\text{X}}^{{\prime}}\in{\text{C}}_{0}\left(\text{X}\right),(\text{i}=0)\) from \({\text{C}}_{0}\left(\text{X}\right)\) where the current circle center \({{\upmu}}_{0}\) fits inside the search space constraints, the current solution is substituted for the closest candidate result in the replacement phase. The candidate solutions are shifted within the designated borders, as shown by Eq. 11, in the following manner if the new solutions are beyond the search space boundaries.

where \(\text{k}\) is an integer between 1 and n, and d is the bound boundary dimension. The acquired ideal solution, X′, indicates the circle’s center in the next iteration. In the second stage of the coeval phase, the active radius of the circle \(({\text{r}}_{1}\)) decreases, and a new set of vectors, \({\text{C}}_{1}\left(\text{X}\right)\) is generated over the new center. In the second step of the selection procedure, the new solution set, \({\text{C}}_{1}\left(\text{X}\right)\), is assessed using \({\text{X}}^{{\prime}}{\text{C}}_{1}\left(\text{X}\right)\). The selected response is kept if it advances to the more difficult ones.

Similarly, the third-step designated center in Fig. 6 is artificially maintained as the new advanced/optimal solution. The phenomenon continues until the completion conditions are fulfilled.

The VS algorithm’s vortex pattern-searching section (after48.

Backtracking search optimization algorithm (BSA)

2013 Civicioglu49 introduced the BSA method for resolving numerical problems. The commencement, selection-I, mutation, crossover, and selection-II stages are represented by these five groups using a uniform distribution function (12); at the first stage, the population is dispersed over the region:

where D and N are the population size and problem dimension, respectively. The uniform distribution function is denoted by G, and the position of the itching person is symbolized by \({\text{P}}_{\text{i},\text{j}}\). Furthermore, the upper and lower problem space limitations are shown by \({\text{up}}_{\text{j}}\).

The following formula, which also determines the search direction, is used to produce historical individuals in the first selection step:

Additionally, the BSA offers the following options for updating the oldP:

where homogeneous real numbers between 0 and 1 stand in for a and b. The characters are then flipped using the permuting() technique as follows:

The following operators are created to perform the mutation:

To determine the population agents’ search orientation, the BSA considers previous data, whereas F controls the amplification of the search direction’s step size.

Model evaluation and presentation

Total ranking systems (TRS) are based on statistical measures such as mean squared error (MSE) and R2. The results of each model were assessed, and the ANN was developed using the prediction network. A range of statistical indicators (BBO-MLP, MVO-MLP, VS-MLP, and BSA-MLP) was used to score the results and assess the effectiveness of each technique.

, \({\text{y}}_{\text{i}}\), \(\widehat{{\text{y}}_{\text{i}}}\),\(\text{and}\,\bar{{\text{y}}_{\text{i}}}\) ̩ which includes the mean, expected, and actual values. The number n denotes the population size. More accuracy is suggested by quantities that are close to 1 but not equal.

The difference between the actual and anticipated numbers is used to calculate the mean square error. The closer the numbers are to zero, the more accurate the model’s forecast. This parameter can be obtained using the function below:

Hyperparameter selection

Hyperparameter selection plays a critical role in the performance and reliability of hybrid metaheuristic–neural network models. In this study, while the majority of hyperparameters for the four hybrid models (BBO-MLP, MVO-MLP, VS-MLP, and BSA-MLP) were selected based on well-established values reported in the literature, the population size was explicitly varied and tuned to observe its influence on model behavior. Population size, representing the number of candidate solutions explored simultaneously by the algorithm, directly impacts the balance between exploration and exploitation in the search space. Smaller population sizes may converge faster but risk premature convergence to suboptimal solutions, potentially missing global optima. Conversely, larger population sizes enhance the algorithm’s ability to explore diverse regions of the solution space, improving the robustness of the model at the expense of computational effort.

In geotechnical applications, such as landfill slope stability assessment, capturing subtle interactions among municipal solid waste layers is essential for reliable predictions. The choice of population size therefore has practical consequences: insufficient exploration could lead to misleading interpretations of slope stability under static or seismic loading, while excessive exploration may increase computational costs without proportional gains. By carefully adjusting the population size within ranges commonly reported in prior optimization studies, we ensured that the models achieved a stable balance between convergence efficiency and solution quality. This approach allows the models to effectively capture the complex, nonlinear behavior of landfill MSW layers while remaining computationally tractable. By transparently reporting all hyperparameter values in tabular form, we provide a clear framework for reproducibility and allow future researchers to further fine-tune these models for specific landfill conditions. Ultimately, thoughtful hyperparameter selection—particularly the tuning of population size—enhances both the predictive power and practical applicability of hybrid metaheuristic–neural systems in geotechnical engineering (Table 2).

Results and discussion

The results of this study demonstrate a comprehensive approach to evaluating the stability of the Barmshour Landfill slope through a combination of finite element modeling (FEM) using PLAXIS 2D and advanced artificial neural network (ANN) optimization techniques. Data from PLAXIS 2D simulations showed that changes in the mechanical properties of municipal solid waste (MSW) layers stratified by age influence the landfill’s stability. Specifically, the impact of internal friction angle and modulus of elasticity on maximum settlement was assessed, highlighting the significant role these parameters play in overall slope deformation. The variation in applied force on the landfill crest with displacement was also examined, revealing a nonlinear relationship and its implications for slope safety under increased loading conditions (Fig. 7). The graphs illustrate the relationship between maximum settlement and two key mechanical parameters—Young’s modulus and internal friction angle—across three distinct MSW layers in the Barmshour Landfill. The layers are categorized by age: Layer 1 (over 10 years old), Layer 2 (5–10 years old), and Layer 3 (less than 5 years old). Each graph illustrates settlement behavior under three scenarios: no surcharge, a 10-meter surcharge, and a 20-meter surcharge, providing a detailed understanding of how surcharging and material properties affect landfill slope stability. A clear inverse relationship is observed for Young’s modulus: as stiffness (Young’s modulus) increases, the maximum settlement decreases for all layers. This behavior is consistent across all surcharge conditions, with older layers (Layer 1) exhibiting higher settlements due to their lower stiffness and more advanced decomposition compared to younger layers.

Similarly, the graphs of internal friction angle show a similar trend: higher friction angles correlate with reduced settlement, reflecting improved shear strength in the MSW layers. The distinction between layers highlights the heterogeneity of MSW, with older, more degraded waste in deeper layers contributing to higher settlements. In contrast, younger layers exhibit greater resistance due to lower levels of decomposition. Surcharging intensifies settlement across all layers, as evidenced by higher displacements under 10-meter and 20-meter surcharges compared to the no-surcharge condition. This demonstrates the critical role of loading in influencing landfill slope behavior. These results highlight the importance of considering material properties and surcharge effects in landfill stability analyses. The data align with PLAXIS 2D simulation findings and underscore its ability to model nonlinear behavior in MSW layers effectively. The analysis provides a basis for improving landfill design and slope stability management by quantifying the impacts of Young’s modulus and internal friction angle.

The results presented in Fig. 7a–f illustrate how the mechanical parameters of MSW, particularly Young’s modulus (E) and internal friction angle (φ), influence the maximum settlement response under varying surcharge loads. As expected, a higher Young’s modulus results in a significant reduction in settlement due to the increased stiffness and reduced compressibility of the aged waste material. Older MSW layers (> 10 years) exhibit smaller settlements than intermediate layers (5–10 years), confirming the time-dependent improvement in waste mechanical properties through biodegradation and densification. Similarly, the internal friction angle shows a nonlinear relationship with settlement behavior. An increase in φ enhances shear resistance, resulting in improved stability and reduced deformation magnitudes. The effect is more pronounced at lower surcharge levels, where frictional resistance dominates the response. However, under higher surcharges (10 m and 20 m), the rate of settlement reduction diminishes, indicating that beyond a certain stress threshold, the waste material reaches a quasi-plastic state. From an engineering perspective, these findings underscore the importance of accurately estimating stiffness and friction parameters for reliable landfill design. The variation across MSW ages underscores the importance of accounting for material heterogeneity in stability analyses, particularly in older landfills, where layer-specific properties can significantly affect performance. Overall, the results offer practical insights into how the mechanical evolution of MSW affects long-term deformation and slope stability.

Figure 8 illustrates the variation of applied force on the landfill crest with displacement at three distinct points (A, B, and C), as detailed in Fig. 2. The graphs compare the performance of six models, each represented by a distinct colored line, to assess their accuracy in predicting force-displacement relationships. At Point A, the force decreases sharply with initial displacement, stabilizing at approximately 0.06 m. Model 1 (blue) and Model 5 (red) exhibit the most significant drop, indicating higher initial stiffness. Models 2, 3, and 4 (green, cyan, and black) exhibit a more gradual decline, suggesting varying material properties or boundary conditions. At Point B, the force-displacement curves display a similar initial decline, but the curves diverge more noticeably beyond 0.2 m displacement. Model 6 (yellow) and Model 5 (red) show a pronounced upward trend, implying a potential increase in resistance or material strengthening at larger deformations. This contrasts with Model 1 (blue), which maintains a relatively flat response, indicating possible limitations in its predictive capability under these conditions. Point C exhibits distinct behavior: all models show a consistent force reduction up to 0.1 m, followed by a plateau. Model 5 (red) again stands out with a steeper initial drop and a subsequent rise, suggesting it may account for nonlinear material behavior or reinforcement effects better than others. The variability among models highlights the influence of different assumptions or input parameters, such as soil properties or loading rates, on the simulated response. Overall, the results suggest that Model 5 consistently captures the complex force-displacement behavior across all points, potentially making it the most reliable for this landfill scenario. However, further analysis, including validation with field data, is recommended to confirm these findings and refine the models. The observed differences underscore the need for tailored modeling approaches based on specific landfill conditions.

The variation of the applied force on the landfill crest with displacement. *Note: the location of points A, B, and C is mentioned in Fig. 2.

Figure 9 shows the performance results for a range of NPOP and acceleration constants (50, 100, 150, 200, 250, 300, 350, 400, 450, and 500). These results indicate that the BBO-MLP algorithm (NPOP =450) (Fig. 6a), the MVO-MLP algorithm (NPOP =350) (Fig. 6b), the VS-MLP algorithm (NPOP =150) (Fig. 6c), and the BS-MLP algorithm (NPOP =500) (Fig. 6d) are the algorithms that most accurately predict the output. The results were gathered from extensive laboratory research and forecasted using the suggested AI models to determine the ultimate carrying capacity. The hybrid MVO-MLP and BBO-MLP models may be regarded as an extraordinary prediction network (with greater accuracy than the traditional ANN model) for predicting strength, even though all of the suggested models produced respectable estimates. The learning approach is appropriate for all prediction models examined, including those with high R2 or low MSE; this must be emphasized. Based on statistical metrics, the BBO-MLP prediction networks also performed better overall (MSE, R2). The results indicate that increasing population size improves convergence rate and reduces MSE, with MVO and BBO outperforming the other algorithms in terms of faster convergence. However, VS and BSA still offer competitive performance, especially with larger populations. Figure 9 presents the convergence behavior of different optimization techniques (BBO, MVO, VS, and BSA) combined with MLP for training, measured by Mean Squared Error (MSE) over iterations. Each plot compares the performance of these methods with varying population sizes (50, 100, 150, 200, 250, 350, 400, and 500) over a maximum of 1000 iterations. BBO-MLP: This plot shows the convergence of BBO combined with MLP. The MSE decreases steadily as the number of iterations increases, with larger populations (e.g., 500) leading to faster convergence and lower MSE. Smaller populations (e.g., 50) converge more slowly and achieve higher MSE values (as shown in Fig. 9a). This plot illustrates the MVO optimization in conjunction with MLP. Like BBO, larger population sizes lead to faster convergence and better results, with the MSE dropping rapidly in the initial iterations and stabilizing as the number of iterations increases. Again, the performance improves as the population size increases (as shown in Fig. 9b). When the VS optimization algorithm is combined with MLP, the MSE drops more slowly than BBO and MVO, indicating a slower convergence rate. However, like the other methods, increasing population size improves performance, resulting in a quicker reduction in MSE over time (as shown in Fig. 9c). In the case of BSA-MLP, the convergence pattern is similar to that of MVO, with larger populations showing a more rapid decline in MSE. While BSA shows a slower initial decrease in error compared to MVO, it ultimately achieves competitive performance with larger populations (as shown in Fig. 9d).

Figures 10, 11, 12 and 13 show the training and test results for the BBO-MLP, MVO-MLP, VS-MLP, and BSA-MLP prediction models. The model’s prediction will be more accurate if the data are more concentrated around the regression line. Regression diagrams for the five optimization methods used in this study—BBO-MLP, MVO-MLP, VS-MLP, and BSA-MLP—are also shown.

The hybrid predictive models, which combined MLPs with nature-inspired optimization algorithms, were assessed using training and test datasets with varying population sizes. Tables 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7 summarize the performance of each hybrid model, including metrics such as mean square error (MSE) and coefficient of determination (R2). In conjunction with MLP, the BBO, MVO, VS, and BSA models are compared. The outcomes of the hybrid network-based BBO-MLP prediction model demonstrate how population size affects the model’s functionality. With the highest overall score of 38, a population size of 450 was the best-performing configuration among those evaluated. This setup achieved the best R2 values (Train = 0.8964, Test = 0.89594) and the lowest MSE for both the training (78.72298) and testing (90.60456) phases, indicating greater predictive accuracy. With a total score of 36, the population size of 500 performed second best, exhibiting outcomes that were just as good but marginally worse than the 450 size.

On the other hand, the design with a population size of 100 earned the lowest overall score, at 4. Its inferior prediction ability was reflected in the lowest R2 scores (Train = 0.8776, Test = 0.8708) and the highest MSE values (Train = 85.13856, Test = 100.286). This outcome highlights the drawbacks of smaller population sizes, which are likely unable to explore the hybrid network adequately to optimize it. With total scores of 34, 26, and 20, respectively, population sizes of 50, 350, and 300 offered the best trade-off between accuracy and computing efficiency. With respectable MSE and R2 values for both the training and testing stages, these setups demonstrated consistent performance across measures.

Interestingly, population size 50 was third overall, showing a decent balance between simplicity and model performance. Although they may require more processing power, larger population sizes—especially those of 450 and 500—improve the model’s convergence and resilience, which enhances its capacity to make accurate predictions. On the other hand, mid-range designs (such as 300) balance computational expense with predictive power, whereas smaller sizes (such as 100) exhibit notable limitations. These results underscore the importance of selecting a suitable population size to optimize the effectiveness of hybrid models, such as BBO-MLP (Table 3).

The findings of the MVO-MLP prediction model highlight the significant impact of population size on performance, as measured by R2 and MSE. The configuration with a population size of 350 achieved the best overall performance with a total score of 40, demonstrating exceptional prediction accuracy. It recorded the lowest MSE values (Train = 77.60, Test = 89.45) and the highest R2 values (Train = 0.90, Test = 0.90). The population size of 300 ranked second with a total score of 34, maintaining strong predictive performance despite slightly higher MSE values (Train = 78.22, Test = 91.52) and marginally lower R2 values (Train = 0.90, Test = 0.89) compared to the 350 configuration. The 250-person population placed third with a total score of 32, demonstrating a good balance between training and testing metrics. In contrast, populations of 50 and 500 performed poorly, both scoring 6, the lowest overall score. The population of 50 had the lowest R2 values (Train = 0.88, Test = 0.87) and the highest MSE values (Train = 85.28, Test = 99.33), indicating limited predictive capability. Similarly, the 500-person population struggled, with low R2 values (Train = 0.88, Test = 0.87) and high MSE values (Train = 84.86, Test = 100.75), reflecting inefficient optimization. Populations of 100, 150, and 450 each scored 18, representing moderate performance, although the 300 and 350 configurations still outperformed them. These results underscore the importance of selecting an optimal population size. Configurations with 350 and 300 individuals demonstrated superior accuracy and reliability, while excessively small or large population sizes, such as 50 and 500, exhibited significant drawbacks. This highlights the need to achieve a balance in optimization to maximize the efficiency and effectiveness of the MVO-MLP model (Table 4).

The findings of the hybrid network-based VS-MLP prediction model demonstrate the significant influence of population size on performance, as reflected in MSE and R2 values. The configuration with a population size of 150 achieved the best overall performance, earning a total score of 36. It exhibited the lowest MSE values (Train = 79.99, Test = 93.45) and the highest R2 values (Train = 0.89, Test = 0.89), making it the most accurate in both training and testing. The 450-person configuration ranked second with a total score of 34, showing comparable accuracy with slightly higher MSE values (Train = 79.69, Test = 95.08) and marginally lower R2 values (Train = 0.89, Test = 0.88). This indicates that, while both setups were robust, the 150-size population slightly outperformed the 450-size configuration in terms of predictive accuracy. The 250-size population secured third place with a total score of 32, striking a good balance between training and testing metrics, with R2 values of 0.89 (Training) and 0.88 (Testing), and MSE values of 79.64 (Training) and 95.80 (Testing). The 350-person setup, with a score of 30, performed well but was outpaced by the top three configurations, suggesting diminishing returns for larger populations beyond 150 and 250. Lower-performing setups included populations of 50 and 100, which scored 4 and 8, respectively. These configurations had the lowest R2 values and the highest MSE values, reflecting poor optimization and limited ability to capture complex data patterns. The results emphasize that intermediate population sizes, particularly 150 and 450, strike the best balance between predictive accuracy and computational efficiency. While larger setups, such as 500, provided reasonable results, they did not outperform mid-range configurations. Conversely, smaller populations, such as 50 and 100, struggled significantly. These findings highlight the importance of selecting an optimal population size to maximize the predictive performance of the VS-MLP model (Table 5).

The outcomes of the hybrid network-based BSA-MLP prediction model demonstrate the impact of population size on performance metrics, including R2 and MSE. The configuration with a population size of 500 achieved the best performance, earning the highest total score of 38. It demonstrated exceptional predictive accuracy and robustness, with the lowest MSE values (Train = 83.69, Test = 91.12) and the highest R2 values (Train = 0.88, Test = 0.89). The population size of 450 ranked second with a total score of 32. Although slightly less accurate than the 500-size setup, it achieved reliable results with MSE values (Train = 84.19, Test = 95.72) and R2 values (Train = 0.88, Test = 0.88), which strike a strong balance between predictive accuracy and computational efficiency. The configurations with population sizes of 100 and 300 tied for third place, each scoring 28. While their performance was comparable, the 100-size setup slightly outperformed the 300-size configuration during testing, with MSE values (Train = 85.20, Test = 94.92) and R2 values (Train = 0.88, Test = 0.89). These setups are viable options for predictive modeling but fall short in accuracy compared to larger populations. Lower-ranking configurations included populations of 50 and 350, which scored 6 and 12, respectively. The 50-size setup exhibited the weakest optimization capacity, with the highest MSE values (Train = 87.34, Test = 110.40) and the lowest R2 values (Train = 0.87, Test = 0.84). Although slightly better, the 350-size configuration struggled compared to mid-range and larger populations. The findings suggest that the BSA-MLP model performs optimally with larger population sizes, particularly 450 and 500, which yield the highest accuracy and reliability. Mid-range sizes, such as 100 and 300, provide decent results and are good alternatives with limited computational resources, whereas smaller configurations, such as 50, are ineffective for accurate predictions (Table 6).

The overall ranking of the five hybrid models reveals distinct performance patterns in managing both deterministic and probabilistic trends in slope stability analysis. The MVO-MLP model, with a population size of 350, achieved the highest overall score (16) by effectively balancing test and training outcomes. Its performance, reflected in both deterministic results (low RMSE) and probabilistic resilience (high R2), demonstrates superior prediction accuracy (Train RMSE = 77.60, Test RMSE = 89.45; Train R2 = 0.90, Test R2 = 0.90). The BBO-MLP model, with a population size of 450, ranked second, with slightly lower predictive accuracy than MVO-MLP (Train RMSE = 78.72, Test RMSE = 90.60; Train R2 = 0.90, Test R2 = 0.90). However, it demonstrated consistent performance across both the training and test stages, indicating its ability to manage parameter fluctuations and uncertainties reliably. The VS-MLP and BSA-MLP models tied for third place, with population sizes of 150 and 500, respectively. The VS-MLP model achieved the lowest testing RMSE (93.45) but displayed slightly weaker resilience in capturing probabilistic patterns, as reflected in its lower R2 values (Train = 0.89, Test = 0.89). In contrast, the BSA-MLP model demonstrated a better balance between RMSE and R2 (Train RMSE = 83.69, Test R2 = 0.89), but its overall ranking suffered due to relatively lower scores in certain parameters (Table 7).

The findings demonstrate the high efficacy of hybrid metaheuristic-neural network models for slope stability analysis, offering greater accuracy and reliability than conventional techniques. These models are especially well-suited for geotechnical applications where uncertainty is common due to their high R2 values, which enable them to incorporate probabilistic patterns. But certain restrictions still exist. Significant computing resources are needed for larger population sizes, such as those in MVO-MLP and BBO-MLP, which might be a deterrent for real-time applications. Variability in outcomes may arise from the hybrid models’ sensitivity to algorithmic settings and initial circumstances. Although these techniques work well for the dataset in question, further research is needed to determine whether they can be applied to larger datasets or more complex situations.

Error analysis

The error analysis in this study focuses on assessing the predictive reliability and stability of the four hybrid models developed for the Barmshour Landfill dataset. Rather than describing error metrics in general terms, this section evaluates how the Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Standard Deviation (Std. D.) reflect the consistency and precision of each model’s predictions.

The Mean Absolute Error (MAE) was calculated as:

where n, \(\widehat{{\text{y}}_{\text{i}}}\), and \({\text{y}}_{\text{i}}\) Stand for population size, actual values, and expected values, respectively; the greater the difference between the two, the higher the MAE. Consequently, accuracy increases as MAE decreases. The accompanying data show that all MAE values for each best-fit model are less than 1, indicating correctness. Here is the standard deviation:

Where the remaining parameters are the same as the top function, and µ is the population mean. This function examines the relationships between the dataset’s mean and each data point. This criterion assesses the models’ correctness by controlling the skewness of the graph. The accuracy of the distribution chart increases with its regularity. This holds for any model, as the accompanying data demonstrates. Figures 14, 15, 16 and 17 illustrate the suggested best-fit error graph for the selected structures: BBO-MLP 350, MVO-MLP 350, VS-MLP 150, and BSA-MLP 500.

The MVO-MLP model again recorded the lowest standard deviation, signifying its robustness and consistency across both training and testing data. Figures 14, 15, 16 and 17 illustrate the residual distributions for the four models, with narrower, more symmetric error distributions corresponding to higher predictive reliability. These results collectively confirm that the proposed hybrid models, particularly MVO-MLP, can accurately and consistently capture nonlinear relationships in MSW mechanical behavior, providing dependable outcomes for slope stability assessment.The error analysis for the MVO-MLP models, as presented in Fig. 15, provides critical insights into the predictive accuracy of the hybrid framework applied to the Barmshour Landfill dataset in Shiraz, Iran. This study leverages the MVO-MLP model, identified as the best performer in the slope stability analysis of municipal solid waste (MSW) layers under static and seismic forces, with two configurations: MVO-MLP 200 (training dataset Np350) and MVO-MLP 350 (testing dataset Np350). The analysis focuses on the discrepancy between predicted outputs and target values, offering study-specific insights into model reliability. For the MVO-MLP 200 training case (Fig. 15a), the target (red) and output (blue) values across 45 samples show a generally close alignment, with notable deviations around samples 5–10 and 35–40. The mean absolute error (MAE) of 59.367 and the mean squared error (MSE) of 6049.74 indicate a reasonable fit; however, peaks in the error plot suggest challenges in capturing extreme MSW behavior under variable loading. The error histogram, with a mean of 0.10139 and standard deviation (STD) of 78.7463, reveals a distribution skewed toward small errors, but with occasional large deviations, reflecting the model’s struggle with highly heterogeneous waste layers at specific points.In the MVO-MLP 350 testing case (Fig. 15b), the analysis spans 18 samples, where a significant outlier at sample 11 (target: 418.404, output: 11) drives a higher MAE of 63.698 and MSE of 8224.5455. This discrepancy highlights the model’s sensitivity to unseen data, particularly where MSW composition or seismic impact varies sharply. The error histogram, with a mean of 12.3463 and a standard deviation of 92.61, shows a broader distribution, indicating greater uncertainty in predictive performance under test conditions. The large error at sample 11 suggests that the model may underpredict high-force scenarios, a critical consideration for landfill stability under extreme events. These findings underscore the MVO-MLP model’s strengths in handling the complex, non-linear behavior of MSW layers, as validated by its R2 values of 0.899 (training) and 0.898 (testing). However, the error spikes, particularly during testing, indicate limitations in generalizing across the Barmshour Landfill’s diverse conditions. This necessitates further refinement, possibly through enhanced data preprocessing or adaptive tuning of metaheuristic parameters, to improve robustness. The analysis offers actionable insights for engineers, highlighting the importance of site-specific validation to mitigate geotechnical design risks.