Abstract

This study aimed to investigate the association between adherence to plant-based dietary patterns and (i) novel risk factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD), (ii) major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), and (iii) novel anthropometric indices among patients with type 2 diabetes. This cross-sectional study included a randomly selected sample of 490 adults with type 2 diabetes. Dietary intake was assessed using a validated food frequency questionnaire (FFQ), and three plant-based diet indices were calculated: the overall Plant-Based Diet Index (PDI), the healthful PDI (hPDI), and the unhealthful PDI (uPDI). Novel cardiovascular risk factors, including Castelli Risk Index 1 (CRI-1), Castelli Risk Index 2 (CRI-2), lipid accumulation product (LAP), atherogenic index of plasma (AIP), and CHOLINDEX (CI), were evaluated. MACE were defined as the occurrence of myocardial infarction, stroke, hospitalization due to heart failure, angioplasty, or bypass surgery. Novel anthropometric indices assessed included the Body Roundness Index (BRI), Abdominal Volume Index (AVI), and A Body Shape Index (ABSI). Associations between plant-based diet indices and study outcomes were analyzed using multivariable logistic regression models. Higher adherence to uPDI was associated with elevated AVI (OR = 1.64; 95% CI: 1.01–2.65; P = 0.042). Participants in the highest tertile of the hPDI had significantly lower CI (OR = 0.42; 95% CI: 0.23–0.76; P = 0.004) and CRI-2 (OR = 0.43; 95% CI: 0.23–0.76; P = 0.004). Moreover, greater adherence to the PDI was associated with a reduced likelihood of bypass surgery (OR = 0.49; 95% CI: 0.24–0.99; P = 0.044). Greater adherence to hPDI was associated with more favorable CVD risk profiles, whereas higher uPDI was linked to increased AVI. Additionally, higher overall PDI was associated with reduced odds of bypass surgery. These associations require confirmation in prospective studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) has emerged as a significant global public health challenge, with its prevalence rising at an alarming rate1,2. Current projections suggest that by 2050, approximately 750 million people worldwide will be living with T2DM3. In Iran, the prevalence of type 2 diabetes is estimated at approximately 10.8% among adults, underscoring that nearly one in ten individuals is living with this condition4. T2DM affects multiple organ systems, with cardiovascular disease emerging as one of its most important and serious consequences, largely driven by chronic hyperglycemia–related vascular injury5,6,7,8,9. Despite the serious complications associated with type 2 diabetes, it is crucial to identify the factors that influence its onset and management. While hereditary factors contribute to the onset of type 2 diabetes, modifiable elements, particularly diet, physical activity, and overall lifestyle, play a major role not only in the initiation of T2DM but also in the severity and progression of its complications10,11,12.

Among individuals with diabetes, suboptimal dietary patterns and excess body weight significantly amplify the chances of developing CVD13,14. These adverse dietary patterns contribute to the persistence and exacerbation of metabolic disturbances, including dyslipidemia and chronic hyperglycemia, which foster insulin resistance and elevate circulating free fatty acid levels15,16. Consequently, this disturbed metabolic milieu initiates a cascade of damaging processes, such as heightened oxidative stress, augmented production of advanced glycation end-products, and dysregulated cellular signaling pathways17,18. These mechanisms converge to accelerate chronic inflammation, vascular endothelial dysfunction, thrombogenesis, and ultimately, atherosclerotic plaque formation19. Given the central role of these complications, optimizing dietary patterns is a critical and modifiable factor that exerts a profound influence on the management of diabetes and its related complications20,21.

Among various dietary interventions, plant-based diets, characterized by an emphasis on whole, minimally processed plant foods such as vegetables, fruits, whole grains, legumes, nuts, and seeds, have garnered increasing attention for their potential metabolic benefits22. Accumulating evidence indicates that adhering to plant-based dietary patterns can enhance glycemic control, decrease insulin resistance, and lead to significant reductions in both blood glucose and HbA1c levels22,23,24. Building upon these metabolic benefits, these diets are also crucial given the severe and persistent cardiovascular risk faced by T2DM patients25. Previous research in general populations has consistently demonstrated that greater adherence to PDI (Plant-Based Diet Index) is linked to lower levels of cardiovascular risk factors, including body weight, body mass index (BMI), and blood pressure26. Findings from a 2019 prospective cohort study further indicated that higher PDI adherence was associated with a reduced incidence of cardiovascular disease27. However, evidence regarding this association among individuals with diabetes remains limited. A cross-sectional study conducted in 2021 reported an inverse association between PDI adherence and fasting blood glucose, while no significant associations were observed for other cardiometabolic risk factors28. Novel anthropometric indices, including the Body Roundness Index (BRI), A Body Shape Index (ABSI), and an Abdominal Volume Index (AVI), provide a more accurate assessment of body fat distribution and cardiovascular risk than traditional measures; however, their relationship with plant-based diet indices has not been investigated. Given the high burden of cardiovascular complications and the lack of studies examining the associations of plant-based diet indices with novel cardiovascular risk factors, major adverse cardiovascular events, and novel anthropometric indices, this study aims to investigate these relationships.

Method and materials

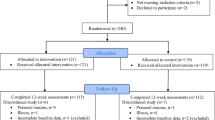

Study design and population

This cross-sectional study was conducted to explore the associations between various plant-based diet indices, including the PDI, the Healthy Plant-Based Diet Index (h-PDI), and the Unhealthy Plant-Based Diet Index (u-PDI), and novel CVD risk factors, major adverse cardiovascular event (MACE), and Novel Anthropometric Indices, among adults living with type 2 diabetes. Participant enrollment took place at the tertiary diabetes and metabolic disorders clinic affiliated with Tehran University of Medical Sciences, spanning the period from May 2021 to September 2022. A total of 490 individuals aged 35 to 80 years with a confirmed diagnosis of type 2 diabetes were randomly selected from patients referred to the clinic. To qualify for the study, participants were required to have lived with type 2 diabetes for at least two years and to fall within the predefined age range. Those undergoing insulin therapy, pregnant or breastfeeding women, individuals on estrogen hormone treatments, and patients with autoimmune diseases, acute renal or gastrointestinal conditions, or hepatic malignancies were excluded. Furthermore, cases with incomplete clinical documentation or with extreme reported daily energy intakes (< 800 kcal or > 4,200 kcal) were not considered for analysis. The study protocol was approved by the Human Ethics Committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences (approval code: IR.TUMS.MEDICINE.REC.1400.369). All procedures were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants before enrollment.

Dietary intake assessment

Dietary assessment was performed using a reliable and extensively validated semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) consisting of 168 items29. An experienced nutritionist conducted in-person interviews to obtain comprehensive dietary histories from each participant, focusing on their usual food consumption over the preceding year. Reported consumption frequencies and portion sizes were converted to average daily intakes, which were subsequently standardized to grams per day. The processed dietary data were analyzed with Nutritionist IV (First Databank Division, Hearst Corporation, San Bruno, CA, USA), a specialized nutrition analysis software modified to reflect Iranian food items, thereby facilitating the accurate determination of participants’ macro- and micronutrient consumption profiles.

Plant-Based diet index calculation

We classified plant-based foods into healthy and unhealthy categories based on established epidemiological evidence linking specific dietary components to chronic conditions such as type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and certain cancers, as well as intermediary outcomes like obesity, hypertension, and inflammation30,31. A total of 16 food groups, including both plant and animal sources, were defined based on their nutritional composition and culinary usage. For each of these groups, we calculated the number of daily servings by summing the intake of whole foods within each category. The overall Plant-Based Diet Index (PDI) was constructed using the scoring system proposed by Martinez-Gonzalez et al.30, while two additional indices, the Healthy Plant-Based Diet Index (hPDI) and the Unhealthy Plant-Based Diet Index (uPDI), were derived based on the framework introduced by Satija et al.31. Healthy plant food groups include whole grains, fruits, vegetables, legumes, nuts, and vegetable oils. Unhealthy plant-based groups encompassed items such as fruit juices, sugar-sweetened beverages, refined grains, and potatoes. Animal-based groups included dairy, eggs, meat (both red and poultry), fish/seafood, animal fats, and other animal-derived products. Quintile cutoffs were calculated for each food group, and scores ranging from 1 to 5 were assigned. For the PDI, plant foods received positive scores: participants in the highest quintile of consumption were assigned a score of 5, while those in the lowest quintile received a score of 1. Animal foods were scored in reverse: higher consumption received lower scores (e.g., 1 for the highest quintile, 5 for the lowest). In the hPDI, higher scores were given for greater intake of healthy plant foods, while higher consumption of unhealthy plant foods and all animal foods received lower scores. Conversely, the uPDI assigned higher scores for greater intake of unhealthy plant foods, with both healthy plant foods and animal foods scored inversely. Final index values were calculated by summing the scores across all 16 dietary groups. Although the theoretical range for each index spanned from 16 (lowest possible adherence) to 80 (highest adherence), observed ranges in our study were 21–74 for PDI, 26–77 for hPDI, and 31–78 for uPDI. It should be noted that an increase in any of these indices reflects a decreased intake of animal-based foods. Alcoholic beverages were excluded from index calculations due to their complex and inconsistent associations with health outcomes.

Biochemical indices assessment

After an overnight fast lasting 12 to 14 h, venous blood samples were obtained and analyzed using standard laboratory techniques to assess levels of triglycerides (TG), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), total cholesterol, and fasting blood glucose (FBS). Blood pressure measurements, including both systolic (SBP) and diastolic (DBP) values, were taken in a seated position by a trained healthcare provider using a validated sphygmomanometer.

Evaluation of novel risk factors for cardiovascular disease

By using LDL-C, HDL-C, and TG and following the formula, the novel risk factors for cardiovascular disease, like CRI-1 (Castelli risk index 1), CRI-2 (Castelli risk index 2), LAP (lipid accumulation product), AIP (Atherogenic index of plasma), and CI (CHOLINDEX), were obtained:

Assessment of major adverse cardiac events (MACE)

Major adverse cardiac events (MACE) serve as a widely accepted composite clinical endpoint in cardiovascular research to assess the efficacy and safety of therapeutic interventions32. While definitions of MACE may differ across studies, a five-component MACE definition was employed in this investigation. This included myocardial infarction, stroke, hospitalization due to heart failure, and revascularization interventions, including angioplasty and bypass surgery. Cardiovascular death, although commonly part of MACE definitions, was excluded from this study due to the absence of such events in the study population33. Data were collected through structured interviews and review of medical records to ensure accuracy and completeness.

Anthropometric indices assessment

Participants’ height was measured without shoes while standing upright, with an accuracy of 0.1 cm. Weight was assessed barefoot and wearing minimal clothing, using a digital scale precise to 0.1 kg. Body mass index (BMI) was computed by dividing the weight in kilograms by the square of the height in meters (kg/m²). Waist circumference was measured at the narrowest area between the lower rib and iliac crest, and hip circumference was recorded at the widest part of the hips, both taken using a non-elastic tape with 0.1 cm precision.

The A Body Shape Index (ABSI), Body Roundness Index (BRI), and Abdominal Volume Index (AVI, all considered novel anthropometric indices, were determined following established methods, utilizing waist circumference (WC, in meters), BMI, and height (in meters), as detailed below:

Physical activity assessment

Physical activity levels were evaluated using the short form of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ), which includes seven items34. This instrument captures the frequency (days per week) and duration (minutes per day) of both moderate and vigorous physical activities, in addition to time spent walking and sitting over the previous seven days. Based on total energy expenditure, physical activity was categorized as low (< 600 MET-min/week), moderate (600–3000 MET-min/week), or high (> 3000 MET-min/week).

Assessment of other variables

A structured questionnaire was used to assess participants’ socioeconomic status, incorporating items related to marital status, educational attainment, employment status, household size, sources of income, type of transportation, home ownership, and other relevant factors. Each item was assigned a specific code, and a composite socioeconomic status score was generated by calculating the mean of these coded responses. The final score was scaled to range from 1 to 10, with higher values indicating higher socioeconomic status. Smoking status was assessed by asking participants whether they were current smokers or non-smokers.

Statistical analysis

To facilitate comparative analyses, all participants were grouped into tertiles according to their PDI, hPDI, and uPDI. Continuous variables describing baseline characteristics are summarized as means ± standard deviations and were examined across tertiles using one-way ANOVA, while categorical variables (expressed as percentages) were assessed with the chi-square test. To evaluate differences in dietary intake, analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was employed, with adjustments made for overall energy intake, except in models where energy intake constituted the main variable of interest. Associations between the plant-based diet indices (PDI, hPDI, and uPDI) and various body shape parameters, emerging cardiovascular risk factors, and major adverse cardiac events were evaluated using binary logistic regression analyses. Thresholds for classification were selected based on established literature: ABSI at 0.08, BRI at 5.20, AVI at 17.30, AIP at 0.11, CRI-1 at ≥ 4, and CRI-2 at ≥ 335,36,37,38,39,40. Analyses were performed using three models: an unadjusted model, Model 1 (adjusted for total energy intake, age, and sex), and Model 2 further adjusted for smoking status, socioeconomic status, history of chronic diseases, adherence to diabetes diets, educational attainment, marital status, physical activity, and supplement use. All statistical procedures were performed with SPSS for Windows, version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), and results with a p-value less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Ethical approval

All procedures involving human participants were conducted in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations, and the study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Human Ethical Committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences (IR.TUMS.MEDICINE.REC.1400.185).

Consent to participate

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their inclusion in this study.

Result

Table 1 presents the baseline characteristics of participants according to tertiles of PDI, hPDI, and uPDI. Individuals in the highest tertile of PDI were more likely to have a higher socioeconomic status compared to those in the lowest tertile. Among participants with the highest hPDI scores, higher marriage rates, greater socioeconomic status, higher educational attainment, increased physical activity levels, lower prevalence of smoking, and lower hip circumference were observed compared to those in the lowest hPDI tertile. Conversely, those in the highest tertile of uPDI tended to be older, predominantly female (p = 0.001), and had a greater likelihood of smoking. Higher scores on the uPDI were positively associated with increased BRI. Conversely, lower uPDI adherence was significantly associated with higher LDL levels. In contrast, higher scores on the hPDI demonstrated a positive correlation with greater measures of CRI-1, CRI-2, CI, HC, and BRI.

Table 2 summarizes the dietary intake profiles of participants across tertiles of PDI, hPDI, and uPDI. Individuals in the highest PDI tertile reported significantly greater consumption of fiber, magnesium, zinc, chromium, calcium, vitamins K and C, whole grains, nuts, legumes, fruits, and vegetables. they also had higher intakes of sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs), fruit juice, and refined grains, whereas participants in the lowest PDI tertile consumed more vitamin D. A comparison across hPDI tertiles revealed that those in the highest group had increased intakes of carbohydrates, fiber, magnesium, chromium, vitamins B9, B12, K, and C, whole grains, legumes, fruits, and vegetables. Conversely, they consumed less refined grains, SSBs, fruit juices, fat, and saturated fatty acids compared with individuals in the lowest hPDI tertile. For uPDI, participants in the highest tertile had significantly greater intakes of fat, saturated and polyunsaturated fatty acids, vitamin B9, vitamin K, nuts, SSBs, fruit juices, and refined grains. In contrast, those in the lowest uPDI tertile reported higher consumption of carbohydrates, fiber, magnesium, calcium, fruits, and vegetables relative to those in the upper tertile.

Table 3 presents ORs and 95% CIs for novel anthropometric indices and novel risk factors across PDI, hPDI, and uPDI tertiles. For body shape indices, an inverse association with BRI was observed when comparing the highest to the lowest tertile of hPDI in the crude model and Model 1; however, this association was no longer significant after full adjustment. Similarly, an inverse association with AVI was detected in Model 1, comparing tertile 3 to tertile 1, but this relationship also disappeared in Model 2. Conversely, Individuals in the highest uPDI tertile had significantly greater odds of elevated AVI in the fully adjusted model (OR = 1.64; 95% CI: 1.01–2.65; P = 0.042). No other significant associations were noted for body shape variables. Regarding novel CVD risk factors, a significant inverse association was found in both the crude model and Model 1 when comparing the highest to the lowest hPDI tertile; this association was not evident after full adjustment. Additionally, participants in the highest hPDI tertile had significantly lower CI (OR = 0.42; 95% CI: 0.42–0.23; P = 0.004) and CRI-2 (OR = 0.43; 95% CI: 0.23–0.76; P = 0.004) values in the fully adjusted model. No significant associations were observed for PDI or uPDI with novel CVD risk factors.

Table 4 presents ORs and 95% CIs for MACE components across PDI, hPDI, and uPDI tertiles. Comparing the highest to the lowest hPDI tertile, a direct association with MACE was observed in the crude and Model 1, which was not significant after full adjustment. Participants in the highest PDI tertile were 51% less likely to undergo bypass in Model 2 (OR = 0.49; 95% CI: 0.24–0.99; P = 0.044); this inverse association was also evident in the crude and Model 1. Additionally, those in the highest uPDI tertile had increased odds of developing CHF in the crude and Model 1, but this association was not maintained after adjustment in Model 2.

Discussion

In this study, higher adherence to uPDI was associated with increased AVI, highlighting a potential link between unhealthy plant-based dietary patterns and adverse body composition. For other novel anthropometric indices, elevated hPDI was initially linked to lower AVI and BRI values in Model 1, though these associations were not maintained after full adjustment for potential confounders. Notably, participants in the highest hPDI tertile demonstrated significantly lower values for CRI-2 and CI, suggesting a favorable impact of healthier plant-based diets on novel CVD risk markers. While a decreased association with LAP was also observed in the crude and Model 1 analyses, this effect was attenuated after further adjustments. Regarding MACE components, individuals in the highest PDI category had a significantly lower likelihood of undergoing bypass surgery. Additionally, a higher hPDI was initially associated with a reduced incidence of MACE, but this relationship was not significant after comprehensive adjustment. Conversely, higher adherence to uPDI was linked to a decreased risk of CHF in unadjusted and partially adjusted models, an association that did not persist in the fully adjusted model.

Despite extensive research on plant-based dietary patterns, there is a notable lack of studies evaluating their associations with novel anthropometric indices, novel CVD risk factors, and MACE, particularly among individuals with T2DM. In a cross-sectional study among diabetic patients, Daneshzad et al. examined PDI, hPDI, and uPDI in relation to common CVD risk factors, reporting no significant associations with hypertension, BMI ≥ 30, or elevated waist circumference28. Similarly, a study of 371 healthy adults found no relationship between adherence to plant-based diets and traditional vascular risk markers such as BMI, total cholesterol, waist circumference, or HDL41. By contrast, findings from Lotfi et al. in individuals with chronic diseases demonstrated that greater adherence to hPDI was linked to lower cholesterol concentrations. Furthermore, higher uPDI scores were significantly associated with elevated levels of certain CVD risk factors, including FBS, cholesterol, and LDL42. A cohort study demonstrated that higher adherence to PDI was associated with a reduced risk of CVD, whereas no significant associations were observed for hPDI or uPDI27. However, a 2021 meta-analysis indicated that both PDI and hPDI were significantly linked to lower CVD risk43. These results are generally consistent with the present findings, which revealed that greater adherence to PDI and hPDI was related to reductions in several novel risk factors and anthropometric indices that can be effective in the development of cardiovascular diseases in individuals with T2DM.

Higher adherence to uPDI was associated with increased AVI, an anthropometric index previously identified as a predictor of CVD44. Individuals in the highest uPDI tertile consumed greater amounts of refined grains and sugar-sweetened beverages, dietary components that have been linked to elevated CVD risk in prior research45,46. However, no significant associations were observed between hPDI or PDI and any of the novel anthropometric indices. This lack of association may be explained by the absence of significant differences in weight, BMI, and waist circumference across the tertiles in our study population, which may have limited the ability to detect meaningful relationships. Greater adherence to the hPDI was associated with lower values of both CRI-2 and CI. Participants in the highest tertile of hPDI also had significantly higher intakes of vitamins B9 and B12, which may contribute to reduced homocysteine levels, a potential mechanism underlying the protective effect against CVD47. Adequate intake of folate (B9) and vitamin B12 is crucial for regulating homocysteine metabolism, as they serve as key cofactors in its conversion to methionine. Elevated homocysteine, resulting from deficiencies in these vitamins, is linked to increased oxidative stress, impaired endothelial function, inflammation, and a higher risk of thrombosis. These processes collectively accelerate atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease progression47,48,49. Moreover, higher intake of these vitamins in the highest tertile may help reduce risk factors associated with cardiovascular disease48. Previous studies have demonstrated a significant association between vegetarian or plant-based diets and reduced risk of cardiovascular disease. However, in our study, we did not observe a significant relationship between plant-based diet indices and Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events, except for an association between PDI and bypass surgery. One possible explanation for this discrepancy is that most prior research has focused on healthy populations, whereas the effects of these diets in individuals with diabetes have not been adequately studied. The presence of a chronic condition such as diabetes may alter or disrupt various biological mechanisms, potentially diminishing the protective effects of plant-based dietary patterns on cardiovascular outcomes in this group. In type 2 diabetes, alterations in the gut microbiome are characterized by a reduction in short-chain fatty acid (SCFA)- producing bacteria, including those that generate acetate, propionate, and butyrate. SCFAs, through actions such as activation of GPR41/GPR43 receptors and induction of interleukin-10 (IL-10) expression, mediate significant anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects50,51,52,53. A decline in these microbial populations can therefore diminish the beneficial impact of dietary fiber on inflammation and oxidative stress54. Furthermore, chronic hyperglycemia in diabetes leads to sustained overproduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS) within the vascular endothelium. While plant-derived polyphenols and flavonoids typically enhance endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) activity and promote nitric oxide (NO)- mediated vasodilation, persistent oxidative stress in diabetes causes NO to rapidly react with ROS, forming peroxynitrite and consequently neutralizing its vasodilatory properties55,56,57,58. These pathophysiological alterations may collectively contribute to the lack of a significant association between plant-based dietary patterns and individual components of MACE observed in our study.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to examine these associations in individuals with type 2 diabetes. Another strength of our study is the incorporation of novel anthropometric indices and novel cardiovascular risk factors. Nonetheless, several limitations should be considered. The cross-sectional design precludes conclusions regarding causality. Additionally, the use of a food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) to assess dietary intake may introduce recall bias. It is also important to note that, as all participants had diabetes, they may have modified their usual dietary behaviors due to disease-related dietary recommendations and restrictions.

Conclusion

Higher adherence to uPDI was linked to increased AVI, while greater hPDI adherence was associated with lower CRI-2 and CI.

Additionally, those with higher PDI had a reduced likelihood of bypass surgery. Prospective studies are needed to confirm these findings.

Data availability

Data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Magliano, D. J. et al. Trends in incidence of total or type 2 diabetes: systematic review. bmj 366 (2019).

Shaw, J. E., Sicree, R. A. & Zimmet, P. Z. Global estimates of the prevalence of diabetes for 2010 and 2030. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 87(1), 4–14 (2010).

Guzman-Vilca, W. C. & Carrillo-Larco, R. M. Number of people with type 2 diabetes mellitus in 2035 and 2050: A modelling study in 188 countries. Curr. Diabetes. Rev. 21 (1), E120124225603 (2025).

Hazar, N. et al. An updated systematic review and Meta-analysis of the prevalence of type 2 diabetes in Iran, 1996–2023. Front. public. Health. 12, p1322072 (2024).

Farmaki, P. et al. Complications of the type 2 diabetes mellitus. Curr. Cardiol. Rev. 16 (4), 249–251 (2020).

Papatheodorou, K. et al. Complications of diabetes. J. Diabetes Res. 2015, 189525 (2015).

Resnick, H. E. & Howard, B. V. Diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Annu. Rev. Med. 53 (1), 245–267 (2002).

Matheus, A. S. M. et al. Impact of diabetes on cardiovascular disease: an update. Int. J. Hypertens. 2013 (1), 653789 (2013).

Collaboration, E. R. F. Diabetes mellitus, fasting blood glucose concentration, and risk of vascular disease: a collaborative meta-analysis of 102 prospective studies. Lancet 375 (9733), 2215–2222 (2010).

Fletcher, B., Gulanick, M. & Lamendola, C. Risk factors for type 2 diabetes mellitus. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 16 (2), 17–23 (2002).

Wild, S. H. & Byrne, C. D. Risk factors for diabetes and coronary heart disease. Bmj 333 (7576), 1009–1011 (2006).

Moosavi, H. et al. Associations of water intake and Intra-Meal fluid consumption with obesity, insulin resistance, and predictors of cardiovascular diseases among Iranian women. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 22303 (2025).

Archundia Herrera, M. C., Subhan, F. B. & Chan, C. B. Dietary patterns and cardiovascular disease risk in people with type 2 diabetes. Curr. Obes. Rep. 6, 405–413 (2017).

Wilson, P. W. & Kannel, W. B. Obesity, diabetes, and risk of cardiovascular disease in the elderly. Am. J. Geriatr. Cardiol. 11 (2), 119–124 (2002).

Athyros, V. G. et al. Diabetes and lipid metabolism. Hormones 17, 61–67 (2018).

Lee, Y. A. et al. Associations between dietary patterns and metabolic syndrome: findings of the Korean National health and nutrition examination survey. Nutrients 15 (12), 2676 (2023).

Creager, M. A. et al. Diabetes and vascular disease: pathophysiology, clinical consequences, and medical therapy: part I. Circulation 108 (12), 1527–1532 (2003).

Rask-Madsen, C. & King, G. L. Vascular complications of diabetes: mechanisms of injury and protective factors. Cell Metabol. 17 (1), 20–33 (2013).

Khoury, J. C. et al. Diabetes mellitus: a risk factor for ischemic stroke in a large biracial population. Stroke 44 (6), 1500–1504 (2013).

El Bilbeisi, A. H., Hosseini, S. & Djafarian, K. Association of dietary patterns with diabetes complications among type 2 diabetes patients in Gaza Strip, palestine: a cross sectional study. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 36, 1–11 (2017).

Maghsoudi, Z. & Azadbakht, L. How dietary patterns could have a role in prevention, progression, or management of diabetes mellitus? Review on the current evidence. J. Res. Med. Sci. Off. J. Isfahan Univ. Med. Sci. 17(7), 694 (2012).

McMacken, M. & Shah, S. A plant-based diet for the prevention and treatment of type 2 diabetes. J. Geriatr. Cardiol. JGC 14(5), 342 (2017).

Jardine, M. A. et al. Perspective: plant-based eating pattern for type 2 diabetes prevention and treatment: efficacy, mechanisms, and practical considerations. Adv. Nutr. 12 (6), 2045–2055 (2021).

Thompson, A. S. et al. A healthful plant-based diet is associated with lower type 2 diabetes risk via improved metabolic state and organ function: A prospective cohort study. Diabetes Metab. 50 (1), 101499 (2024).

Balakumar, P., Maung-U, K. & Jagadeesh, G. Prevalence and prevention of cardiovascular disease and diabetes mellitus. Pharmacol. Res. 113, 600–609 (2016).

Li, Y. et al. Plant-based diets and the incidence of cardiovascular disease. BMJ Nutr. Prev. Health 6(2), 212 (2023).

Kim, H. et al. Plant-based diets are associated with a lower risk of incident cardiovascular disease, cardiovascular disease mortality, and all‐cause mortality in a general population of middle‐aged adults. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 8(16), e012865 (2019).

Daneshzad, E. et al. Associations between plant-based dietary indices and dietary acid load with cardiovascular risk factors among diabetic patients. Int. J. Diabetes Dev. Ctries. 41, 71–83 (2021).

Mirmiran, P. et al. Reliability and relative validity of an FFQ for nutrients in the Tehran lipid and glucose study. Public Health. Nutr. 13 (5), 654–662 (2010).

Martínez-González, M. A. et al. A provegetarian food pattern and reduction in total mortality in the Prevención Con Dieta Mediterránea (PREDIMED) study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 100, 320S–328S (2014).

Satija, A. et al. Plant-based dietary patterns and incidence of type 2 diabetes in US men and women: results from three prospective cohort studies. PLoS Med. 13 (6), e1002039 (2016).

Kip, K. E. et al. The problem with composite end points in cardiovascular studies: the story of major adverse cardiac events and percutaneous coronary intervention. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 51 (7), 701–707 (2008).

Bosco, E. et al. Major adverse cardiovascular event definitions used in observational analysis of administrative databases: a systematic review. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 21 (1), 241 (2021).

Booth, M. Assessment of physical activity: an international perspective. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport. 71 (sup2), 114–120 (2000).

Endukuru, C. K. et al. Cut-off values and clinical efficacy of body roundness index and other novel anthropometric indices in identifying metabolic syndrome and its components among Southern-Indian adults. Diabetol. Int. 13, 188–200 (2022).

Zhang, J. & Yu, X. The association between the body roundness index and the risk of chronic kidney disease in US adults. Front. Med. 11, 1495935 (2024).

Bhardwaj, S. et al. Atherogenic index of plasma, Castelli risk index and atherogenic coefficient-new parameters in assessing cardiovascular risk. Int. J. Pharm. Biol. Sci. 3 (3), 359–364 (2013).

Salcedo-Cifuentes, M. et al. Conventional biomarkers for cardiovascular risks and their correlation with the Castelli risk index-indices and TG/HDL-c. Arch. De Med. (Manizales). 20 (1), 11–22 (2020).

Shen, S. et al. Association between ideal cardiovascular health and the atherogenic index of plasma. Medicine 95 (24), e3866 (2016).

Niroumand, S. et al. Atherogenic index of plasma (AIP): A marker of cardiovascular disease. Med. J. Islamic Repub. Iran. 29, 240 (2015).

Shirzadi, Z. et al. Associations of plant-based dietary patterns with cardiovascular risk factors in women. J. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Res. 14 (1), 1 (2022).

Lotfi, M. et al. Plant-based diets could ameliorate the risk factors of cardiovascular diseases in adults with chronic diseases. Food Sci. Nutr. 11 (3), 1297–1308 (2023).

Quek, J. et al. The association of plant-based diet with cardiovascular disease and mortality: a meta-analysis and systematic review of prospect cohort studies. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 8, 756810 (2021).

Islam, M. T. et al. Anthropometric Indices in Predicting 10-year Cardiovascular Risk among Males and Females Aged 40–74 Years in South and Southeast Asia: Analysis of 12 WHO STEPS Survey Data. The Lancet Regional Health-Southeast Asia, 29 (2024).

Swaminathan, S. et al. Associations of cereal grains intake with cardiovascular disease and mortality across 21 countries in prospective urban and rural epidemiology study: prospective cohort study. Bmj 372 (2021).

Yin, J. et al. Intake of sugar-sweetened and low-calorie sweetened beverages and risk of cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Adv. Nutr. 12 (1), 89–101 (2021).

Liu, Y. et al. Associations of serum folate and vitamin B12 levels with cardiovascular disease mortality among patients with type 2 diabetes. JAMA Netw. open. 5 (1), e2146124–e2146124 (2022).

Huang, J. et al. Intakes of folate, vitamin B6, and vitamin B12 and cardiovascular disease risk: a National population-based cross-sectional study. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 10, 1237103 (2023).

Wu, S. et al. Dietary folate, vitamin B6, and vitamin B12 and risk of cardiovascular diseases among individuals with type 2 diabetes: A case-control study. Ann. Nutr. Metabol. 79(1), 5–15 (2023).

Qin, J. et al. A metagenome-wide association study of gut microbiota in type 2 diabetes. Nature 490 (7418), 55–60 (2012).

Karlsson, F. H. et al. Gut metagenome in European women with normal, impaired and diabetic glucose control. Nature 498 (7452), 99–103 (2013).

Koh, A. et al. From dietary fiber to host physiology: short-chain fatty acids as key bacterial metabolites. Cell 165 (6), 1332–1345 (2016).

Maslowski, K. M. et al. Regulation of inflammatory responses by gut microbiota and chemoattractant receptor GPR43. Nature 461 (7268), 1282–1286 (2009).

Canfora, E. E., Jocken, J. W. & Blaak, E. E. Short-chain fatty acids in control of body weight and insulin sensitivity. Nat. Reviews Endocrinol. 11 (10), 577–591 (2015).

Brownlee, M. Biochemistry and molecular cell biology of diabetic complications. Nature 414 (6865), 813–820 (2001).

Cai, H. & Harrison, D. G. Endothelial dysfunction in cardiovascular diseases: the role of oxidant stress. Circul. Res. 87 (10), 840–844 (2000).

Du, X. L. et al. Hyperglycemia inhibits endothelial nitric oxide synthase activity by posttranslational modification at the Akt site. J. Clin. Investig. 108 (9), 1341–1348 (2001).

Landmesser, U., Hornig, B. & Drexler, H. Endothelial function: a critical determinant in atherosclerosis?. Circulation 109(21_suppl_1), II-27–II−33 (2004).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the support of the Subspecialty Clinic for Diabetes and Metabolic Diseases, affiliated with Tehran University of Medical Sciences, in conducting this study.

Funding

This study was supported by Tehran University of Medical Sciences.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.A. and E.N-E. conceptualized and designed the study. M.H.S. supported the analysis of cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors. M.Z. and M.M.M. conducted the study, and M.H.S. performed the data analysis. M.Z. and M.M.M. interpreted the findings. M.M.M. and M.Z. drafted the manuscript, while M.Z. and L.A. revised the final version. E.N-E. provided critical feedback on data presentation, which substantially enhanced the quality of the manuscript. She also reviewed and edited various sections of the study for scientific accuracy.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mahjourian, M.M., Nasli-Esfahani, E., Zeinalabedini, M. et al. Plant-based diet indices in relation to novel cardiovascular risk factors, major adverse cardiovascular events, and novel anthropometric indices in patients with type 2 diabetes. Sci Rep 16, 3024 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32909-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32909-8