Abstract

We investigate the classification potential of nonlinear Turing patterns by employing convolutional features. Classifying spatial heterogeneity caused by Turing instability, observed in natural phenomena such as animal coat patterns and neural models, remains a challenging problem due to the difficulty in learning the parameters governing such pattern formation. We consider a minimal structure of a convolutional neural network including convolutional layers, activation functions, and pooling layers to classify patterns based on the reaction-diffusion model. To better capture nonlinear variations while alleviating overfitting, we additionally examine deeper convolutional structures and employ data augmentation methods. By extracting crucial features, pattern diagrams are comprehensively generated to illustrate spatial and structural variations. This approach aims to uncover potential applications of machine learning in understanding pattern formation mechanisms. The training data is generated by performing numerical simulations over a relatively large domain to minimize the influence of boundary conditions, followed by partitioning the computed results into smaller regions. The results and performances demonstrate the effectiveness of this approach.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Turing patterns, observed in natural phenomena such as animal coats and fish scales, are generated by reaction-diffusion systems due to their instability. The patterns can take various forms in a two-dimensional space such as spots, stripes, or mixed ones1. Since Alan Turing first introduced the concept of pattern formation through mathematical rules2, these patterns have gained theoretical and practical importance in numerous biological, chemical, and physical systems3,4,5,6,7. Although extensive research has been conducted in various disciplines, including biological processes1, identifying Turing patterns or estimating their parameters from specific image data remains a challenging problem8.

Pattern classification has been one of the most popular applications using a neural network9,10,11,12,13,14,15. Contrary to traditional methods, which rely on handcrafted feature engineering and manual parameter tuning for capturing the full diversity of patterns, recent advances in neural networks offer promising tools for resolving these challenges by automating feature engineering and parameter estimation. To increase efficiency and accuracy of classification, prominent research directions have focused on aspects of data processing, network structures, and computational algorithms16,17,18.

Recently, feature engineering based on a Ginzburg–Landau free energy functional was proposed to improve classification accuracy for distinguishing three categories of patterns using a single-layer neural network19. The proposed feature engineering significantly improved the neural network classifier’s test accuracy, increasing it from \(40\%\) to \(90\%\), and it remains future work to explore unsupervised algorithms with similar features, which have shown promising results in identifying five clusters; small spot, large spot, inverted spot, stripe, and constant phases.

Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) are known as being suited for image processing due to their ability to efficiently capture spatial hierarchies and features in structured data20. Unlike fully connected neural networks, which treat each input feature as independent, CNNs leverage convolutional layers to focus on localized regions of an image, enabling the detection of spatial patterns such as edges, textures, and more complex structures. These characteristics make CNNs particularly effective for analyzing Turing patterns, which inherently exhibit spatial and repetitive structures that are challenging to capture with traditional neural networks8,21,22.

In this paper, we investigate the potential of convolutional maps for classifying Turing patterns generated by reaction-diffusion models. By leveraging CNN architectures, we aim to extract meaningful features from simulation data and evaluate the robustness of the approach across a broader range of patterns beyond the initial three categories. Our method provides a new framework for understanding and classifying spatial heterogeneity using deep learning.

The structure of this paper is as follows. The section “Model description” provides a brief overview of the Lengyel–Epstein model, which describes pattern formation, along with its numerical solution. The process of generating and partitioning data for training is outlined, followed by a review of the nonlinear features from a previous study. Building on this foundation, a model incorporating convolution maps is proposed. The section “Results” presents the results of the proposed method. Finally, the section “Conclusion” concludes the paper with a summary of findings.

Model description

Patterns in Lengyel–Epstein model

The Turing patterns are generated by solving the Lengyel–Epstein model23, defined as follows: For the inhibitor u and the activator v, the model is given by

where \(D_u\) and \(D_v\) are the diffusion coefficients, and \(k_1\) and \(k_2\) are the positive constants. The computational domain is a two-dimensional square \(\Omega\) with periodic boundary conditions. Following the examples of Turing patterns described in1, we choose the nontrivial equilibrium point as \((\bar{u},\bar{v})=(1+k_2^2/25, k_2/5)\). For numerical simulations, we set \(D_u=1\) and \(k_2=11\), with an initial state perturbed by random noise:

where \(\text {rand}(x,y)\) represents a uniform random distribution between \(-1\) and 1. Various Turing patterns can be expected by exploring different parameter values in the \((D_v, k_1)\) space 1.

To briefly explain the method used to obtain the numerical simulation results, the time evolution for the parameter setting \(D_v = 0.05\) and \(k_1 = 1\) is presented over the domain \(\Omega = (0,10) \times (0,10)\), as illustrated in Fig. 1. The color map indicates high values in red, intermediate values in green, and low values in blue. Specifically, a uniform mesh grid with \((N_x, N_y) = (64, 64)\) was used, and the Laplacian operator was discretized using a fast Fourier transform under periodic boundary conditions. For time discretization, the explicit Euler method was employed with a sufficiently small time step \(\Delta t = 1/2^{10}\), and the simulation proceeded up to the final time \(T=512\). Unless stated otherwise, subsequent numerical simulations follow this method with necessary extensions and adjustments.

Since pattern formation analysis primarily relies on steady-state results, sufficiently long-time simulations are required. However, numerically defining the steady state can be computationally expensive. Instead, patterns are classified based on recognizable formations observed visually. Here, we observe that recognizable patterns begin to emerge once the simulation time exceeds approximately \(T=64\).

Figure 2 illustrates the pattern diagram showing the spatial distribution of the activator v simulated by (1) at various points in the \((D_v, k_1)\) parameter space. There is considerable interest in distinguishing between stripes and spots in reaction-diffusion systems, particularly within specific parameter regions. As demonstrated in the figure, the model is capable of generating various pattern types commonly observed in animal skins, including spots, stripes, and inverted spots.

Such reaction-diffusion systems have been widely applied in biological contexts, including the study of skin pigmentation24, morphogenesis25,26, and ecological population dynamics27. The primary goal of this study is to explore how different parameter combinations influence the formation and transition of pattern types, thereby providing deeper insight into the mechanisms underlying biological pattern formation. While the generated patterns are visually distinguishable to the human eye, obtaining these results requires extensive testing and output generation, which inevitably incurs significant computational costs. Therefore, we study a learning model capable of facilitating pattern analysis through efficient parameter selection and applicability to result evaluation of the trained model. Ultimately, the learning process needs to be straightforward and simple, as it requires testing various parameters.

Pattern classification by two nonlinear features

For the training and validation data, simulations are conducted using a sufficiently large computational domain, which is subsequently partitioned to minimize the influence of boundary conditions. As shown in Fig. 3, four groups of distinct patterns are generated using the Lengyel–Epstein model with different parameter combinations \((D_v, k_1)\). We refer to these patterns as small spot, large spot, stripe, and inverted spot, from left to right in the figure. The computational domain is set to \(\Omega =(0,40)\times (0,40)\), and 15 samples are generated by selecting different random initial conditions. Only one representative sample from each group is selectively illustrated. For numerical computation, a spatial grid of \(256 \times 256\) is applied over the entire domain size of (40, 40) until the final time \(T=128\). This domain is partitioned into a \(4 \times 4\) grid, where each subdomain has a physical size of (10, 10). Each subdomain is represented by a numerical grid of \(64 \times 64\) pixels. Consequently, a total of 16 images are extracted from each simulation, resulting in 960 samples generated through repeated simulations with different initial conditions. The relevant dataset is included in the Supplementary File.

Various patterns partitioned into images as small spot, large spot, stripe, and inverted spot, from left to right. The domain is partitioned into a \(4 \times 4\) grid, where each subdomain has a physical size of (10, 10). Each subdomain is represented by a numerical grid of \(64 \times 64\) pixels.

In the previous work19, two nonlinear features are considered, which can be represented as the operators \(F_1(X) = \Vert \nabla X \Vert ^2\) and \(F_2(X) = X - X^3\). Figure 4 shows the results obtained by applying these nonlinear features. The first column represents the final partition of the data corresponding to Fig. 3. The second and third columns show the result of applying \(F_1\) and \(F_2\), respectively. Each figure represents the result of applying min-max scaling to prevent biases that may arise from differences in scale. For comparison with the image, the results of the feature map are represented in a gray color scale. It is confirmed that the two features respectively highlight the interface of the two phases and the bulk region.

To briefly describe the neural network used in19, it is illustrated in Fig. 5. The i-th input image \(X_i\), after being min-max rescaled to the range of \(\pm 1\), is used to compute the corresponding feature maps as:

To compute the discrete gradient of \(F_1\), it is defined in a staggered manner along the x-axis and y-axis, resulting in a reduction of the image size. Consequently, the final size becomes \(63 \times 63\). For consistency in the code implementation, the first row and column of \(F_2\) are also removed to match the same size. After applying min-max scaling to the range of \(\pm 1\) and flattening the data into column vectors, the representations are given by

Next, the output node value of the output layer is computed as

where b is a bias constant and \(W_j\) are weighted matrices of size \(4\times 63^2\). Here, \(u_i\) is a vector in \(\mathbb {R}^4\), and the softmax function \(\phi _\text {soft}\) is applied to obtain the final output \(y_i = \phi _\text {soft}(u_i)\). Finally, the loss function is employed as the cross entropy error.

Figure 6 shows the validation accuracy results comparing how much the application of nonlinear features improves learning performance. In the simple structure, the final accuracy reaches approximately \(46.4\%\), while applying nonlinear features increases it to \(54.5\%\), though the improvement is not substantial. Since the learning outcomes can vary depending on the initial weight selection, the experiment was repeated 10 times. The average accuracies, as obtained, are \(46.4\%\) and \(54.8\%\) for the simple and nonlinear-feature models, respectively, with minimum accuracies of \(45.8\%\) and \(54.2\%\), indicating that significant improvement is difficult to achieve. In contrast to the previous study19, where the classification is limited to three classes, this experiment expands the scope to four classes, which may account for the less dramatic improvements in learning performance observed.

Pattern classification by convolution maps

As shown in Fig. 4, the two features tend to highlight the interface and bulk phase, respectively, indicating their potential usefulness for feature engineering in classification tasks. Nevertheless, as illustrated in Fig. 6, the accuracy performance exhibits certain limitations, which appear to be influenced by variations in the dataset and the complexity introduced by the increased number of patterns.

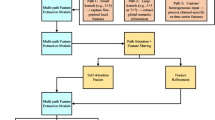

Notably, the nonlinear features share significant similarities with the convolution operations used in CNNs. This observation suggests the possibility of learning multiple convolutional filters to enhance feature extraction. Figure 7 provides a concise overview of the proposed neural network incorporating several convolutional filters. Let us consider K convolutions with discrete kernel sizes of \(3 \times 3\), denoted as \(C_k\) for \(k=1,2,\dots , K\). For the ith input image \(X_i\), the corresponding convolutional feature maps are computed as:

where \(\gamma _k\) is a corresponding bias to \(C_k\). The stride is set to 1, and valid padding is applied, resulting in an output size of \(62 \times 62\). An element-wise ReLU activation is first applied to each feature map \(Z_{i,k}\), introducing nonlinearity by setting negative values to zero. Subsequently, a max-pooling operation with a kernel size of \(2 \times 2\) reduces its spatial dimensions while preserving the most salient features. After these operations, the transformed feature map corresponding to the k-th feature map of the i-th sample can be expressed as

This feature map is then reshaped into a one-dimensional column vector to serve as the input to the subsequent fully connected layer:

Repeating this procedure for all K feature maps generates a collection of feature vectors \({f_{i,1}, f_{i,2}, \dots , f_{i,K}}\). The final output of the fully connected layer is computed as a weighted sum of these feature vectors, along with a bias term b, given by:

where \(W_k\) are weight matrices of size \(4 \times 31^2\) corresponding to the k-th feature vector, and \(u_i \in \mathbb {R}^4\) is the intermediate output vector for the i-th sample. Each element of \(u_i\) represents a raw score for one of the four target classes. To obtain the predicted class probabilities, the softmax function \(\phi _\text {soft}\) is applied to \(u_i\), resulting in:

where \(y_i \in \mathbb {R}^4\) represents the normalized probabilities for the four target classes. Finally, the cross-entropy loss function is used to quantify the divergence between the predicted probabilities \(y_i\) and the true label distribution. It is defined as:

where N is the total number of samples, \(t_{i,j}\) represents the one-hot encoded ground truth label for class j, and \(y_{i,j}\) is the predicted probability for class j. This loss function ensures the model is optimized to maximize the likelihood of the correct class for each sample.

The complexity of patterns and their high similarity motivates the use of architectures that extend beyond a single layer, and increasing the depth of the convolutional layers further enhances the expressive capacity of the network. To describe this structure, consider L convolutional layers. For each layer \(l = 1,\dots ,L\), the convolution kernels \(C^{(l)}_{k,p}\) connect inputs indexed by \(p = 1,\dots ,K_{l-1}\) to outputs indexed by \(k = 1,\dots ,K_l\). At the l-th layer, the convolutional feature maps are computed as

where \(F^{(l-1)}_{i,p}\) denotes the input feature map and \(\gamma ^{(l)}_k\) is the bias. For the first layer, we set \(F^{(0)}_{i,1} = X_i\) and denote the corresponding index as \(K_0 = 1\) for notational consistency. In our setting, all subsequent layers use the same number of output maps, so \(K_l = K\) for all \(l \ge 1\). Analogous to the single-layer case, the output of each convolutional layer undergoes max-pooling and a ReLU activation. The resulting feature maps are given by

This procedure is repeated through all layers, and at the final layer L, the resulting \(K_L\) feature maps are flattened to form the input to the fully connected stage. The remaining steps proceed in the same manner as in the single-layer network. Figure 8 illustrates an example of this multi-layer configuration for \(L = 3\).

Results

The proposed model is trained using the 960 datasets described in Fig. 3, which consist of pattern data generated from random initial conditions at the parameters \((D_v, k_1) = (0.01, 5),\ (0.04, 1),\ (0.03, 5),\ (0.04, 7)\). A stochastic gradient descent method with a mini-batch size of 32 is applied, and training is conducted for 10,000 epochs with a learning rate of 0.004. The data is divided into \(70\%\) for training and \(30\%\) for validation to assess accuracy. To ensure consistent comparisons across different parameter settings, the dataset partitioning remains fixed throughout the analysis. For all subsequent training processes, unless explicitly stated otherwise, the parameters follow the same training configuration.

Accuracy and convolution features

Table 1 summarizes the accuracy calculated on the validation data, while the training accuracy achieves a value of 1 in almost all experiments and is therefore excluded. The accuracy considered in the calculation corresponds to the final result obtained after 10,000 epochs. The reported results include the minimum, average, and maximum values obtained from training with 10 different initial weights. As the number of convolutions increases, notable improvements in accuracy are observed despite minor perturbations in the minimum accuracy values. Specifically, the average accuracy exceeds \(95\%\) from three convolutions onward, and the minimum accuracy surpasses \(98\%\) starting from five convolutions.

In Table 1, the validation accuracy reaches near-perfect levels, approaching \(100\%\), when six convolutional layers are utilized. To better understand the underlying feature extraction process, Fig. 9 illustrates the convolution map results for a selected example. The original image used in this analysis is identical to the one shown in Fig. 4, ensuring consistency in comparison. The convolution results reveal patterns that align closely with the nonlinear features \(F_1\) and \(F_2\) observed earlier. These features effectively capture key distinctions, such as separating the interior and exterior regions, or emphasizing the interface between them. Notably, the interface highlights structural boundaries, such as the division between the left and right regions, clearly illustrating the model’s ability to delineate spatial features in a meaningful way.

Prediction of pattern diagram

Figure 10 shows a diagram illustrating the pattern estimation results obtained from the trained model applied to 400 different parameter sets randomly sampled from the range \((D_v, k_1) \in [0.01, 0.06] \times [1, 11]\).

The dataset is provided in the Supplementary File. In the scatter plot, colors correspond to different patterns as follows: red for small spot, green for large spot, blue for stripe, black for inverted spot, and gray for constant. For comparison, results with varying numbers of convolutions are presented, with the test cases showing the lowest and highest accuracy placed in the first and second rows, respectively. Patterns are regarded as constant if the magnitude of the function v is below \(10^{-4}\). As the number of convolutions increases, the estimated patterns become progressively more well-organized.

To obtain synthetic data generated for estimation, simulations are conducted with randomly selected parameters over the domain \((0,40)\times (0,40)\) on a \(256 \times 256\) grid for a relatively short time, \(T=128\). Since the trained model was developed using a domain size of (10, 10) with a grid resolution of \(64 \times 64\), the given image is uniformly divided into 16 subregions. The pattern in each subregion is estimated using the model, and the overall pattern of the image is determined through a majority voting scheme.

Figure 11 illustrates how the majority voting results are derived for several specific cases. The pair \((D_v, k_1)\) is expressed with three significant figures, and the label list is presented using lexicographical ordering. Here, the labels 0, 1, 2, and 3 correspond to the patterns small spot, large spot, stripe, and inverted spot, respectively. The first row represents a result located in the middle of the bulk region, far from the training data in the phase diagram. In contrast, the second row shows a properly selected result situated at the transition region between two or more patterns. Despite the constraint of a limited observation time of \(T=128\), the model demonstrates a robust ability to classify a substantial portion of the parameter space with high efficacy, underscoring its practical utility. While the majority voting mechanism assigns a specific pattern to each case, the mixed patterns illustrated in the second row provide unique insights into the transition interfaces between patterns.

Selected results partitioned into images for illustrating how the majority voting results are derived for several specific cases. Here, the labels 0, 1, 2, and 3 correspond to the patterns small spot, large spot, stripe, and inverted spot, respectively. The first row shows a single-pattern case; the second highlights a mixed-pattern case near a transition boundary.

Model performance

To illustrate the performance of a representative model, Fig. 12 presents the evolution of accuracy and loss across epochs for the case with six convolutional features. It is selected from those achieving the same validation accuracy for \(K=6\) in Table 1 and Fig. 10, and is designated as the optimal learning model. The training process reaches \(100\%\) accuracy in the early epochs. While the training and validation losses differ in magnitude, both decrease consistently over the course of training.

The notable result in Fig. 10 is the maximum accuracy achieved when \(K=2\). This is particularly significant because, as shown in Table 1, the accuracy already approaches \(97.9\%\). Figure 13 illustrates both the changes in accuracy and the loss over epochs. The accuracy demonstrates strong performance from the early epochs, with both the training and validation accuracies reaching high levels. However, the loss reveals a different trend: while the training loss continues to decrease, the validation loss saturates, indicating a potential overfitting effect during training.

When using two convolutions, the conditions are harsh, so overfitting is not surprising and can be reasonably understood. Figure 14 illustrates the results for the case with four convolutions, focusing on scenarios with minimum accuracy. The associated estimated pattern diagram corresponding to the minimum accuracy case with \(K=4\) can be found in Fig. 10. Similarly, comparable loss levels tend to yield similar performance in the phase diagram, indicating that the quality is more closely tied to the loss than to K or accuracy. In the phase diagram, the boundary regions between red, green, and blue areas appear unstable, indicating potential challenges in accurately defining these interfaces.

In Figs. 13 and 14, we observe that the validation loss saturates even when the accuracy reaches values exceeding \(94\%\), whereas the training loss continues to decrease. This divergence is indicative of overfitting and seems to affect the reliability of the resulting phase diagrams. To quantify this behavior, we report the minimum, mean, and maximum values of the training and validation losses over 10 independent runs for each choice of the number of convolutional features in Tables 2 and 3.

While Tables 2 and 3 alone may not fully reflect the complexity of the data, it is evident that overfitting occurs more readily when the number of convolutional features is smaller. This is a compelling example of the limitations and risks of relying solely on accuracy to evaluate model performance. Empirically, meaningful results are observed when the validation loss drops below \(10^{-3}\). This suggests that, to avoid overfitting, models should be selected not only based on accuracy but also with sufficiently low validation loss. It is also important to consider an adequate number of convolutional maps during model design.

Deeper convolutions and augmentation

In Fig. 12, all validation accuracies for \(K=6\) were equal to 1, so we selected the case whose validation loss lay near the midpoint among the ten trials. To further illustrate the variability across runs, Fig. 15 displays the worst and best cases together with their corresponding training and validation losses. Accuracy does not provide meaningful discrimination in this setting, as all runs attain perfect validation accuracy, as shown in Table 1. Although the loss does not directly determine the structure of the phase diagrams, larger loss values tend to coincide with noticeable differences in their appearance. Although overfitting is difficult to characterize purely through numerical criteria, a discrepancy of roughly an order of magnitude between the training and validation losses is still observed.

Motivated by the observation that even the best case in the previous results exhibits a substantial gap between the training and validation losses, we extend the model by adopting the multi-layer structure described in Fig. 8. As in the previous tests, training is carried out over ten independently perturbed weight initializations. To highlight the degree of improvement most transparently, Fig. 16 displays the worst case among the ten runs. If the worst case shows signs of improvement, it is at least suggestive that the better-performing cases may exhibit similar or greater improvements. As the number of convolutional layers increases, the gap between the training and validation losses becomes noticeably smaller.

Data augmentation can also be incorporated using well-known techniques. We apply a basic approach in which horizontal and vertical flips are randomly performed. Figure 17 shows how the loss evolution changes when augmentation is added to the same experiment presented in Fig. 15. Even with only a single convolutional layer, a dramatic improvement can be observed.

Dataset reconstruction with extended parameter sets

In this section, we construct a dataset different from the one described in the section “Pattern classification by two nonlinear features”. In the previous setting, one parameter is selected for each of the four pattern classes, and numerical simulations are performed using fifteen random initial conditions. Each resulting image is then divided into sixteen subregions, yielding a total of 960 samples. In the new setting, we instead select five parameter sets for each class and generate pattern data from three independent initial conditions for every parameter choice. This again produces 960 samples in total. The parameter sets used for each pattern class are listed below. For the small spot, the parameters are (0.01, 5), (0.012, 3.5), (0.012, 7), (0.01, 6), and (0.01, 8). For the large spot, the parameters are (0.04, 1), (0.03, 1.5), (0.05, 1), (0.045, 1), and (0.055, 1.5). For the stripe, the parameters are (0.03, 5), (0.02, 9), (0.04, 4), (0.025, 7), and (0.035, 4.5). For the inverted spot, the parameters are (0.04, 7), (0.03, 9.2), (0.05, 5.4), (0.035, 8), and (0.043, 6.6). Details of the dataset are available in the Supplementary File.

For all experiments in this section, the number of convolutional features in the model is fixed at \(K=6\). Even with the revised dataset, the validation accuracy remains similarly high. Across ten runs, the lowest accuracy exceeds 98.9%. Consequently, we rely on the loss to assess performance differences. Figure 18 presents the loss evolution for the one-convolution-layer case, with and without applying the augmentation method. In this setting, we again employ only the most basic augmentation, consisting of random horizontal and vertical flips. Here, we select the run that achieves the lowest validation loss in order to evaluate how well this best-performing case is maintained under the revised dataset. Without augmentation, the gap between the training and validation losses becomes even larger, whereas with augmentation, the gap is reduced. However, the degree of improvement differs from what was observed with the previous dataset, as shown in Fig. 17.

In the earlier dataset, increasing the number of convolutional layers proved effective in mitigating overfitting. To further reduce the gap between the training and validation losses under the revised dataset, we therefore increase the number of convolutional layers once again. Figure 19 presents the loss evolution when two and three convolutional layers are applied. As before, we select the run that achieves the lowest validation loss to assess how well the best-performing case is maintained. The results show that the gap becomes smaller as the number of layers increases. However, unlike the behavior observed in Fig. 15, the reduction in the gap is relatively modest.

The more limited improvement observed with deeper convolutional layers, as seen in Fig. 19, may reflect the increased complexity of the revised dataset, which incorporates a broader range of initial conditions and parameter values. To further investigate whether data augmentation can compensate for this added variability, Fig. 20 shows the change in the loss evolution when the augmentation method is applied to the same training setup. With augmentation, the gap between the training and validation losses becomes more clearly reduced. Overall, these results indicate that, under the expanded dataset, both increasing the number of convolutional layers and incorporating suitable augmentation are necessary to achieve improved stability in the training process.

Tables 4 and 5 summarize the lowest and highest values obtained from ten repeated experiments for each configuration of convolutional layers and augmentation under the revised dataset. The results clearly indicate that, as the number of convolutional layers increases and augmentation is applied, the gap between the training and validation losses becomes smaller.

Conclusion

Although the patterns may appear simple to human observation, capturing their underlying spatial heterogeneity and generating plausible pattern diagrams from specific parameter sets posed a significant challenge, requiring a robust approach. We demonstrated the use of convolutional features to classify nonlinear Turing patterns with the Lengyel–Epstein model. Moreover, by applying only convolutional layers without fully connected networks, we highlighted the critical role of convolution maps in achieving robust classification results. Using minimally extracted training data, the trained model effectively generated pattern diagrams, demonstrating that even with a moderate number of convolutions, meaningful results could be achieved. This study enhances our understanding of pattern formation mechanisms and provides a foundation for studying broader complex models and parameter spaces. In addition, we observed that increasing the number of convolutional layers and incorporating augmentation techniques contributed to mitigating overfitting. Furthermore, our findings underscore the limitations of relying solely on accuracy to evaluate model performance, highlighting the necessity of achieving sufficient loss reduction to ensure reliable training outcomes.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

References

Othmer, H. G., Painter, K., Umulis, D. & Xue, C. The intersection of theory and application in elucidating pattern formation in developmental biology. Math. Model. Nat. Phenom. 4, 3–82 (2009).

Turing, A. M. The chemical basis of morphogenesis. Bull. Math. Biol. 52, 153–197 (1990).

Horváth, J., Szalai, I. & De Kepper, P. An experimental design method leading to chemical Turing patterns. Science 324, 772–775 (2009).

Marcon, L. & Sharpe, J. Turing patterns in development: what about the horse part?. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 22, 578–584 (2012).

Kondo, S., Watanabe, M. & Miyazawa, S. Studies of Turing pattern formation in zebrafish skin. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 379, 20200274 (2021).

Vittadello, S. T., Leyshon, T., Schnoerr, D. & Stumpf, M. P. Turing pattern design principles and their robustness. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 379, 20200272 (2021).

Menou, L., Luo, C. & Zwicker, D. Physical interactions in non-ideal fluids promote Turing patterns. J. R. Soc. Interface 20, 20230244 (2023).

Schnörr, D. & Schnörr, C. Learning system parameters from Turing patterns. Mach. Learn. 112, 3151–3190 (2023).

Lippmann, R. P. Pattern classification using neural networks. IEEE Commun. Mag. 27, 47–50 (1989).

Shin, Y. & Ghosh, J. The pi-sigma network: An efficient higher-order neural network for pattern classification and function approximation. In IJCNN-91-Seattle international Joint Conference on Neural Networks, vol. 1, 13–18 (IEEE, 1991).

Ning, Z. et al. Pattern classification for gastrointestinal stromal tumors by integration of radiomics and deep convolutional features. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 23, 1181–1191 (2018).

Kaufmann, K., Lane, H., Liu, X. & Vecchio, K. S. Efficient few-shot machine learning for classification of EBSD patterns. Sci. Rep. 11, 8172 (2021).

Zhu, L. & He, L. Two different approaches for parameter identification in a spatial-temporal rumor propagation model based on Turing patterns. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 107, 106174 (2022).

Eliwa, E. H. I., El Koshiry, A. M., Abd El-Hafeez, T. & Farghaly, H. M. Utilizing convolutional neural networks to classify monkeypox skin lesions. Sci. Rep. 13, 14495 (2023).

Shaberi, H. S. A., Kappassov, A., Matas-Gil, A. & Endres, R. G. Optimal network sizes for most robust Turing patterns. Sci. Rep. 15, 2948 (2025).

Goras, L., Chua, L. O. & Pivka, L. Turing patterns in CNNs: III—Computer simulation results. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I: Fundam. Theory Appl. 42, 627–637 (1995).

Arena, P., Branciforte, M. & Fortuna, L. A CNN-based experimental frame for patterns and autowaves. Int. J. Circuit Theory Appl. 26, 635–650 (1998).

Bucolo, M., Buscarino, A., Corradino, C., Fortuna, L. & Frasca, M. Turing patterns in the simplest MCNN. Nonlinear Theory Appl. IEICE 10, 390–398 (2019).

Oh, S. & Lee, S. Extracting insights of classification for Turing pattern with feature engineering. J. Korean Soc. Ind. Appl. Math. 24, 321–330 (2020).

Rawat, W. & Wang, Z. Deep convolutional neural networks for image classification: A comprehensive review. Neural Comput. 29, 2352–2449 (2017).

Goras, L., Chua, L. O. & Leenaerts, D. Turing patterns in CNNs: I—Once over lightly. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I: Fund. Theory Appl. 42, 602–611 (1995).

Goras, L., Ungureanu, P. & Chua, L. O. On Turing instability in nonhomogeneous reaction–diffusion CNN’s. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Regul. Pap. 64, 2748–2760 (2017).

Lengyel, I. & Epstein, I. R. Modeling of Turing structures in the chlorite-iodide-malonic acid-starch reaction system. Science 251, 650–652 (1991).

Prum, R. O. & Williamson, S. Reaction-diffusion models of within-feather pigmentation patterning. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 269, 781–792 (2002).

Tapaswi, P. & Saha, A. Pattern formation and morphogenesis: A reaction–diffusion model. Bull. Math. Biol. 48, 213–228 (1986).

Harrison, L. G., Wehner, S. & Holloway, D. M. Complex morphogenesis of surfaces: theory and experiment on coupling of reaction–diffusion patterning to growth. Faraday Discus. 120, 277–293 (2002).

Cantrell, R. S. & Cosner, C. Spatial Ecology via Reaction-Diffusion Equations (Wiley, 2004).

Acknowledgements

The first author (J. Shin) was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grants funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No. RS-2023-00214185), and by the Ministry of Education through the Global Learning & Academic Research Institution for Master’s\(\cdot\)PhD Students and Postdocs (LAMP) Program (No. RS-2024-00445180). The corresponding author (S. Lee) was supported by the research fund of the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIP) (No. RS-2024-00342949).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Jaemin Shin, Seunggyu Lee Data Curation: Jaemin Shin, Junyoung Park, Minhwan Ji Formal analysis: Jaemin Shin, Seunggyu Lee Funding acquisition: Jaemin Shin, Seunggyu Lee Investigation: Jaemin Shin, Junyoung Park, Minhwan Ji, Seunggyu Lee Methodology: Jaemin Shin, Seunggyu Lee Project administration: Jaemin Shin, Seunggyu Lee Resources: Jaemin Shin, Seunggyu Lee Software: Jaemin Shin, Junyoung Park, Minhwan Ji Supervision: Jaemin Shin, Seunggyu Lee Validation: Jaemin Shin, Seunggyu Lee Visualization: Jaemin Shin, Seunggyu Lee Writing – original draft: Jaemin Shin, Seunggyu Lee Writing – review & editing: Jaemin Shin, Junyoung Park, Minhwan Ji, Seunggyu Lee

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shin, J., Park, J., Ji, M. et al. Exploring potential of Turing pattern classification through convolution maps. Sci Rep 16, 3008 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32911-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32911-0