Abstract

Postoperative pulmonary complications, particularly atelectasis, are common after cardiac surgery and may contribute to impaired gas exchange or acute lung injury (ALI). Neurally Adjusted Ventilatory Assist (NAVA) delivers ventilatory support proportional to the patient’s respiratory drive, offering theoretical advantages over Pressure Support Ventilation (PSV), including improved synchrony, enhanced diaphragmatic efficiency, and reduced risk of ventilator-induced lung injury. However, comparative data on gas exchange, dead space, and regional ventilation during weaning after cardiac surgery remain limited. This prospective crossover study evaluated 12 mechanically ventilated patients with mild ALI following cardiac surgery across three ventilation phases: two PSV phases (PSV1 and PSV2) separated by a phase of NAVA. Intrapulmonary shunt fraction was calculated from measurements obtained via a Swan-Ganz catheter. Physiological dead space fraction (VD/VT) was assessed using three methods: the Bohr–Enghoff equation, end-tidal CO₂-derived alveolar dead space fraction (AVDSf-ET), and a novel time-to-volume converted capnographic approach (VCAP-CALC). Regional ventilation was assessed using electrical impedance tomography (EIT), and neuroventilatory efficiency (NVE) was calculated from diaphragmatic electrical activity (EAdi). Data were analyzed using linear mixed-effects models to account for repeated measures and within-subject variability. VD/VT was significantly lower during NAVA compared with PSV1 and PSV2 when assessed by VCAP-CALC (58.5% vs. 63.8% and 61.3%, respectively; p < 0.001). The PaO₂/FiO₂ ratio and NVE were significantly higher during NAVA (p = 0.01 and p = 0.037, respectively). No significant difference in pulmonary shunt fraction was observed. EIT revealed a modest increase in dorsal end-expiratory lung volume during NAVA, without redistribution of tidal volume or Center of Ventilation. The VCAP-CALC method showed strong agreement with established dead space measures (R2 = 0.77–0.82) and demonstrated high repeatability (mean coefficient of variation 3.5%). NAVA is a safe and feasible ventilatory mode following cardiac surgery, associated with reduced dead space fraction, improved oxygenation and enhanced neuroventilatory efficiency. Given that shunt fraction remained unchanged, the observed improvement in ventilation–perfusion (V/Q) matching reflects a reduction in VD/VT. The potential implications for postoperative recovery and long-term outcomes merit evaluation in larger clinical studies.

ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT03217305. Initial Release 21/06/2017.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cardiac surgical patients are prone to develop postoperative atelectasis, which predispose to postoperative respiratory insufficiency and pneumonia1,2. Contributing factors include the inflammatory response to cardiopulmonary bypass, open chest surgery, ischemia–reperfusion injury, and the postoperative gravitational effects of the heart and mediastinum on adjacent lung segments3,4. Assisted ventilation facilitates weaning by reducing sedation needs and relying on the patient’s neuromuscular effort. Pressure Support Ventilation (PSV) delivers a preset level of support triggered by flow or airway pressure, while Neurally Adjusted Ventilatory Assist (NAVA) uses diaphragmatic electrical activity (EAdi), measured via an esophageal catheter, to provide proportional support based on neural respiratory drive. Compared to PSV, NAVA offers several advantages, including improved synchrony between drive and effort, reduced risk of over-assistance, lower sedation requirements, shorter weaning time, decreased need for post-extubation non-invasive ventilation5, and reduced mortality6,7,8,9. Although beneficial, NAVA is most likely still underutilized in clinical practice. Barriers include limited staff training, increased demands on physician bedside presence, catheter-related issues, challenges in selecting appropriate patients, and the fact that NAVA is a proprietary mode available only on ventilators from a single manufacturer requiring an additional module.

Comparative data on pulmonary shunt and dead space between PSV and NAVA during weaning after cardiac surgery are limited. We hypothesized that NAVA reduces both, as assessed by Swan-Ganz catheterization and time-to-volume converted capnography (VCAP-CALC).

Materials and methods

Study design

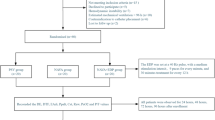

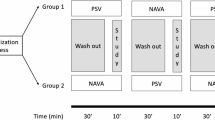

This study was approved by the Regional Ethical Board in Gothenburg (Dnr:581–14) and conducted in accordance with the principles of the Helsinki Declaration. As the study inclusion criteria required prolonged postoperative mechanical ventilation under sedation, informed consent was obtained from the patients’ nearest relatives. The trial design was a prospective interventional within-subject crossover, comprising two PSV phases separated by an intervening NAVA phase. Each phase lasted 60 min, with 30 min for steady state followed by 30 min for data acquisition (Fig. 1). The ClinicalTrials.gov registration (NCT03217305) specified a 20-min acquisition period, which was extended to 30 min before study start. In accordance with EQUATOR guidelines for clinical trial reporting, key elements from the CONSORT 2010 Statement and the CONSORT Extension for Crossover Trials were applied (Supplement Fig. S1). Patients were enrolled between August 2018 and March 2022.

Study flowchart illustrating the data acquisition sequence across three ventilation phases (PSV1, NAVA, PSV2). Each phase comprised a 30-min steady-state equilibration followed by 30-min data acquisition, including three data points and two 2-min EIT recordings. The EAdi signal level was kept consistent throughout the trial, regardless of the ventilation mode. PSV Pressure Support Ventilation, NAVA Neurally Adjusted Ventilatory Assist, EIT Electrical Impedance Tomography.

Participant selection

Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Included patients required invasive mechanical ventilation between postoperative days 3 and 10 following on-pump cardiac surgery. Eligibility criteria included stable ventilator settings in an assisted mode, a functioning NAVA catheter, and a consistent EAdi signal. Postoperative acute lung injury (ALI) was defined as a PaO₂/FiO₂ ratio ≤ 300 mmHg, corresponding to mild Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) according to the Berlin definition10, and consistent with impaired pulmonary gas exchange not primarily attributable to left heart failure, pulmonary congestion, or fluid overload. Patients were excluded in cases of hemodynamic instability (norepinephrine infusion > 0.25 µg/kg/min, any inotropic support, or mixed venous oxygen saturation < 50%), deep sedation, contraindications to Swan-Ganz catheterization, or unreliable catheter readings.

Data acquisition

Hemodynamic and respiratory data were recorded using AcqKnowledge software (BIOPAC Systems, Inc., Goleta, CA, USA) connected via the MP150 interface and an intermediate analog-to-digital converter (Supplementary Fig. S2). Hemodynamic parameters were continuously sampled from the Philips IntelliVue Patient Monitoring System (Koninklijke Philips N.V., Amsterdam, The Netherlands). External events and manually obtained data–including arterial blood gas sampling, cardiac output and pulmonary capillary wedge pressure measurements, and initiation of EIT recordings–were annotated in AcqKnowledge as event markers, enabling precise temporal alignment with the continuously recorded signals (Fig. 1). Respiratory data, including airway flow, respiratory rate, and EAdi, were continuously collected from the Maquet Servo-u ventilator and integrated into AcqKnowledge via the Servo-Tracker interface and a digital-to-analog feed to the MP150 unit. Expired CO₂ was measured using a stand-alone side-stream capnometer (Datex Normocap, Datex Medical) connected directly to the MP150 unit. Because the capnometer operated independently and employed a side-stream sampling system, inherent delays and variable transit times precluded direct hardware temporal alignment. Instead, offline alignment was subsequently performed in AcqKnowledge by identifying the onset of the CO₂ decline at the transition from exhalation to inspiration and the sharp rise in inspiratory flow.

Respiratory settings

Patients were positioned with the head elevated at 20–30° and sedated with either propofol–remifentanil or dexmedetomidine–remifentanil to maintain a Richmond Agitation–Sedation Scale (RASS) score of –3. This sedation level was selected to suppress coughing and spontaneous movements, which could compromise the accuracy of measurements. All patients received supportive invasive mechanical ventilation via either an endotracheal tube (size 7.0 for women and 8.0 for men) or a tracheotomy tube (size 8.0 for all). All patients received active heated humidification (MR850, Fisher & Paykel Healthcare, Auckland, New Zealand), heat and moisture exchanger (HME) filters were not used. The ventilator circuit was standardized for all patients and included the same Y-piece, corrugated circuit connector, and a CO₂ sampling adapter positioned proximal to the airway. PSV was delivered using the Servo-U ventilator (Maquet Critical Care, Solna, Sweden), with settings individually adjusted to achieve the most comfortable breathing pattern at the lowest effective pressure required to maintain normocapnia (PaCO₂ 35–45 mmHg), and a tidal volume (VT) of 6–8 mL·kg⁻1 ideal body weight. An inspiratory trigger sensitivity of -2 cmH₂O, along with titrated levels of PEEP and FiO₂ to maintain PaO₂ > 90 mmHg, were kept constant throughout the study protocol.

The NAVA catheter (EAdi Catheter, Maquet Critical Care, Solna, Sweden) was positioned in the esophagus via the nasogastric route and adjusted to optimize readings of the diaphragm’s electrical activity. The EAdi signal (µV) was titrated to target equal EAdi-max levels between PSV and NAVA at the start of each measurement period. This was accomplished by adjusting the NAVA level (cmH₂O/µV) and the pressure support level (cmH₂O), thereby ensuring equivalent respiratory drive across both ventilatory modes.

EAdi metrics in NAVA ventilation

-

Mean EAdi (EAdiMEAN, µV): Represents the mean electrical activity of the diaphragm across the entire respiratory cycle.

-

Maximum EAdi (EAdiMAX, µV): The peak electrical activity of the diaphragm during inspiration; when multiplied by the NAVA level (cmH₂O/µV), it determines the peak inspiratory pressure delivered by the ventilator.

-

EAdi Area Under the Curve (EAdiAUC, µVs/breath): Reflects the total electrical activity of the diaphragm throughout an entire respiratory cycle, providing an estimate of the overall diaphragmatic drive.

-

Neuroventilatory Efficiency (NVE, mL/EAdiMEAN µV): Represents the relationship between tidal volume and diaphragmatic electrical activity, providing an estimate of how efficiently neural respiratory drive translates into ventilatory output, reflecting the effectiveness of neuroventilatory coupling.

-

Neural Triggering and Cycling: Inspiration begins when the EAdi signal exceeds 0.5 µV, and expiration is initiated when EAdi falls below 70% of its peak value; this threshold is referred to as the cycle-off criterion (Supplementary Fig. S3).

Pulmonary artery catheterization

A Swan-Ganz pulmonary artery catheter (Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, CA, USA) was inserted via the right internal jugular vein. Cardiac output (CO) was measured using bolus thermodilution. Each injection consisted of 10 mL of cold saline (~ 4 °C), drawn from an ice bath and injected smoothly over approximately four seconds, beginning at end-expiration. For each ventilation phase (PSV1, NAVA, PSV2), three data points were collected, including CO, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP), and mixed venous oxygen saturation (mSvO₂) (Fig. 1). The average of the three values was used to represent each phase. Cardiac index (CI) was calculated as CO/Body Surface Area. The shunt fraction (Qs/Qt) was calculated using the Berggren equation11:

Qs/Qt = (CcO₂ – CaO₂) / (CcO₂ – CvO₂)

Where CcO₂ is the pulmonary capillary oxygen content, CaO₂ is the arterial oxygen content, and CvO₂ is the mixed venous oxygen content. Oxygen content was calculated as the sum of hemoglobin-bound oxygen and dissolved oxygen12. Pulmonary capillary oxygen content (CcO₂) was estimated using alveolar oxygen tension (PAO₂), which was derived from the alveolar gas equation13, assuming a respiratory quotient (RQ) of 0.8 and a dry barometric pressure of 713 mmHg. Full hemoglobin saturation was assumed for CcO₂ calculation. Venous oxygen content (CvO₂) was determined based on the mSvO₂ and venous partial pressure of oxygen (PvO₂), obtained from the pulmonary artery catheter.

Calculating the pulmonary dead space fraction

The physiological dead space fraction (VD/VT) was derived using three different methods, with methodological details and derivations provided in the Appendix:

PĒCO₂ (mixed expired CO₂) was derived from V̇CO₂ (metabolic CO₂ production) using the calorimetric version of the alveolar ventilation equation (P̅ECO₂ = V̇CO₂ x 0.863 / VE)16. V̇CO2 was calculated from the RQ (assumed at 0.8) and V̇O2 (V̇CO₂=RQ x V̇O2). V̇O2 was calculated from the arterio-venous oxygen content difference12 (Ca-v O₂).

-

2.

End-tidal alveolar dead space fraction17,18 [AVDSf-ET, (PaCO2—PETCO2)/PaCO2]: The end-tidal CO₂ fraction (PETCO₂) was determined as the average of end-tidal values obtained from three 60-s recordings during each ventilation phase.

-

3.

Time-to-Volume converted Capnography (VCAP-CALC):

A detailed description of this method is provided in the supplementary materials. In brief, time-integrals of respiratory flow was converted into volumes, time-aligned with the capnogram based on the onset of inspiratory flow. Onset of expiration is not visually detectable on the capnogram, hence defined as the point where flow transitioned from inspiration to expiration, as indicated by the dashed line A in Fig. 2. Accurate identification of this transition point is essential for subsequent analyses. Airway dead space was defined as the midpoint of Phase II of the capnogram, corresponding to Fowler’s original equal-area method19. The exact midpoint was determined as the inflection point along the Phase II curve, identified as the location of maximum inclination (i.e., the peak of the first derivative and the zero-crossing of the second derivative), and is shown by dashed line B in Fig. 2. The intersection of the extrapolated linear segments from the mid-portions of Phases II and III of the capnogram, referred to as slope II (SII) and slope III (SIII), defines the alpha angle, as outlined in several studies on the clinical interpretation of capnography waveforms20,21. The x-axis position of this intersection marks the transition from Phase II to Phase III and aligns with Tang et al.’s equal-area line, which defines physiological dead space using the same CO₂ reference as the Enghoff modification22,23. To objectively determine the x-axis position of the alpha angle (denoted xα, Fig. 2), we derived a combined equation based on the intersection of the linear equations describing SII and SIII. The value of xα is given by:

where:

-

f´(xS2): The peak slope of CO₂, i.e., peak first derivative, was identified at the point where the second derivative, f''(xₛ₂), equals zero, marking the transition from positive to negative curvature and corresponding to the inflection point of Phase II.

-

xS2: The x-axis position (time) at which f´(xS2) occurs.

-

f(xS2): The PCO₂ value on the y-axis corresponding to xS2.

-

f´(xS3): The slope of CO₂, i.e., peak first derivative, assessed at the mid-portion of Phase III, where the second derivative, f''(xS3), equals zero, indicating that the inclination is stable and approximately linear.

-

xS3: The x-axis position (time) at which f´(xS3) occurs.

-

f(xS3): The PCO₂ value on the y-axis corresponding to xS3.

Expiratory CO₂ (kPa) time-aligned with airway gas flow over a single breath lasting 3 s. The upper two panels display the first and second derivatives of the CO₂ curve. Dashed line A marks the onset of expiration. Dashed line B indicates the transition from airway dead space exhalation to alveolar volume exhalation. Dashed line C indicates the point at which exhalation shifts from physiological dead space to gas originating from ventilated alveoli. The point labeled Xα represents the intersection of extrapolated straight lines approximating the mid-slope regions of Phase II (SII) and Phase III (SIII) of the capnogram.

Calculating metabolic production of carbon dioxide

The Enghoff modification of the Bohr equation for calculating dead space requires the P̅ECO₂, traditionally obtained from expired gas collected in a Douglas bag24. Modern ventilators measure P̅ECO₂ via volumetric capnography. However, as neither method was available in the present study, three alternative approaches were employed to estimate V̇CO₂. Subsequently, P̅ECO₂ was calculated by applying the rearranged calorimetric version of the alveolar ventilation equation (P̅ECO₂ = V̇CO₂ × 0.863 / VE)16, with further methodological details provided in the Appendix.

Estimates Resting Energy Expenditure (REE, kilocalories per day, kcal/day) based on an individual’s body height, weight, age, and gender. The Siddiqi modification27 further refines this estimate by accounting for prior surgery, trauma, infection, and fever. By applying Weir’s equation28 to the calculated REE and assuming a respiratory quotient of 0.8, V̇CO₂ can be calculated.

-

2.

Arterio-Venous Oxygen Content Difference12 (Ca-v O₂):

V̇CO₂ is estimated by calculating the Ca-v O₂ and converting it to V̇CO₂ using an assumed RQ of 0.8 (V̇CO₂ = RQ x V̇O2).

-

3.

Capnometry-Based (VCAP-CALC): Time-based capnometry was used to derive data analogous to volumetric capnography. Alveolar ventilation was estimated by subtracting physiological dead space from tidal volume, as inferred from capnography waveform analysis. V̇CO₂ was then calculated using the clinically adapted alveolar ventilation equation [V̇CO₂ = (PaCO₂ × VA) / 0.863].

Electrical impedance tomography

Setup and data acquisition

A 16-electrode silicone EIT belt (Ref. 84 20 0-57/58/59, Dräger Medical, Lübeck, Germany) was positioned around the thoracic cage between the 6th and 7th intercostal spaces to avoid diaphragmatic interference. Placement was verified before each measurement. The belt was connected to a Pulmovista® 500 EIT device (Dräger Medical), sampling data at 40 Hz with a 50 beats·min⁻1 filter to attenuate cardiac motion artifacts. For each ventilation phase (PSV1, NAVA, PSV2), two 2-min recordings were acquired (Fig. 1). Data were analyzed using Dräger’s EIT Diag® software, with the PSV1 baseline recording serving as the reference for subsequent analyses.

Image reconstruction and analysis

The ventilated area was divided into equally sized ventral (non-dependent) and dorsal (dependent) ROIs, which were compared across ventilation phases. During baseline recording, tidal tissue impedance variation (∆Z) was calibrated against tidal volume, enabling subsequent calculation of dorsal tidal volume (VT dorsal) and dorsal end-expiratory lung volume change (∆EELVdorsal), expressed in arbitrary units (AU). The Centre of Ventilation (CoV) and Intra-Tidal Variation (ITV) display modes, along with validation metrics for EIT, have been previously described1,29.

Blood gas analysis

Arterial and venous blood samples were analyzed using a Siemens RAPIDPoint® 500 (Siemens Healthcare GmbH, Germany) to determine PaO₂/FiO₂ ratio, dead space fraction, and oxygen content.

Primary and secondary outcomes

Primary outcomes include the comparison of pulmonary shunt fraction and physiological dead space fraction between PSV and NAVA. Secondary outcomes involved assessment of regional lung aeration by EIT (VT dorsal, ∆EELVdorsal, CoV, ITV), PaO₂/FiO₂ ratio, and NVE. Additional secondary analyses compared methods for estimating dead space fraction and V̇CO₂, including time-to-volume converted capnography (VCAP-CALC). Safety and feasibility outcomes were evaluated post-hoc to complement the predefined physiological endpoints.

Data analysis

Sample size calculation

The sample size was determined using a paired t-test to assess within-subject differences in shunt fraction between ventilation modes. The expected mean difference was estimated at 0.05, with a standard deviation of 0.05, based on pilot data. A two-sided significance level (α) of 0.05 and a statistical power of 80% (β = 0.20) were applied. Based on these assumptions, the required sample size was calculated to be 10 pairs.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (version 26, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Patient characteristics and baseline values were summarized as mean ± standard deviation (SD) for normally distributed variables and as median with interquartile range (IQR) for non-normally distributed variables.

Comparisons between ventilation modes (PSV, NAVA, and a subsequent second run of PSV) were conducted using a linear mixed-effects model (LME). This was considered more appropriate than a standard repeated-measures ANOVA because it accounts for individual patient variability (with each patient serving as their own control), handles the non-independence of repeated measures (as each patient undergoes three measurements), and allows for modelling carryover effects (if NAVA influences the second PSV phase). When significance was detected, post hoc pairwise comparisons were performed using t-tests. A two-sided p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variance for LME and paired t-tests were evaluated using the Shapiro–Wilk test and visual inspection of histograms, while Levene’s test was used to assess homogeneity of variance.

To compare different methods of calculating dead space, regression analysis was used to assess the predictive relationship between methods, while Bland–Altman analysis was performed to evaluate agreement.

Coefficient of variation

The precision of the time-to-volume converted capnometry method were evaluated using the coefficient of variation (CV = [SD / Mean] × 100%). To assess technical precision under controlled conditions, we obtained 15 repeated measurements from a single patient, evaluating intra-individual repeatability. Three patients with 15 measurements each were included to capture inter-individual reproducibility. Mean CV was calculated as the average of individual CVs (∑CV / Number of Patients). An average CV below 5% was considered indicative of high precision across repeated trials and individuals.

Results

Patient demographics

Patient characteristics, including respiratory variables and baseline hemodynamics are summarized in Table 1. A CONSORT flow diagram is provided in the supplementary materials (Fig. S1).

Primary outcomes

Dead space fraction was significantly lower during NAVA compared to PSV, as assessed by VCAP-CALC (58.5 vs. 63.8% in PSV1 and 61.3% in PSV2, respectively; p < 0.001, Table 2, Fig. 3). The mean paired difference between PSV1 and NAVA was − 5.0% (95% CI − 6.7 to − 3.3), and between NAVA and PSV2 + 2.5% (95% CI − 0.2 to + 5.1). No significant differences were observed in Bohr-Enghoff dead space or alveolar dead space fraction derived from end-tidal CO₂ (AVDSf-ET). Pulmonary shunt fraction showed no significant differences between ventilation modes (Table 3).

Individual capnometry-based dead space fraction values (VCAP-CALC) across three ventilation phases: First run Pressure Support Ventilation (PSV1), Neurally Adjusted Ventilatory Assist (NAVA), and second run Pressure Support Ventilation (PSV2). Each line represents one patient (n = 12), with values connected to illustrate within-subject changes across mode transitions.

Secondary outcomes

EELVdorsal increased when switching from PSV to NAVA and decreased upon returning to PSV (increase of 23 AU and decrease of 43 AU, respectively; p = 0.026, Table 2). Ten of twelve patients showed an increase in ΔEELVdorsal when switching from PSV1 to NAVA, and eight demonstrated a corresponding decrease when returning to PSV2 (Supplementary Fig. S4). No significant differences were observed in VT dorsal, CoV, or ITV (Supplementary Fig. S5). The PaO₂/FiO₂ ratio was significantly higher during NAVA compared to PSV (279.0 vs. 266.3 in PSV1 and 263.3 in PSV2, respectively; p = 0.01). The mean paired difference between PSV1 and NAVA was + 12.8 mmHg (95% CI + 1.5 to + 23.9), and between NAVA and PSV2 − 15.7 mmHg (95% CI − 26.7 to − 4.7).

NVE was also higher during NAVA (96.3 mL/μV vs. 83.8 mL/μV in PSV1 and 94.7 mL/μV in PSV2, respectively; p = 0.037, Table 2).

Linear regression analysis revealed a strong correlation between the Bohr–Enghoff method, based on Swan-Ganz-derived measurements, and the VCAP-CALC method (R2 = 0.77–0.82 across ventilation phases; p < 0.001, Table 4A, Fig. 4A). Bland–Altman plots demonstrated the average bias between the methods to be –0.098, –0.053, and –0.085 for PSV1, NAVA, and PSV2, respectively (Fig. 4B and supplementary Fig. S6). VCAP-CALC yielded CVs of 2.44, 5.42, and 2.70% respectively, with an average CV of 3.52%.

Panel A: Linear regression analysis plots illustrating the relationship between Bohr-Enghoff dead space (independent variable) and capnometry-based dead space (dependent variable) across ventilation phases. Blue points represent observed data, and the red line indicates the best-fit linear regression. The regression equations (slope and intercept) for each ventilation phase are as follows: PSV1: y = 0.48x + 0.38; NAVA: y = 0.58x + 0.29; PSV2: y = 0.60x + 0.30. These results indicate that for each unit increase in Bohr-Enghoff dead space, the corresponding increase in capnometry-based dead space ranges from 0.48 to 0.60 units, depending on the ventilation phase. Panel B: Bland–Altman plots comparing Bohr-Enghoff (α) vs capnometry-based (ß) dead space fraction (lower panel B), across ventilation phases. The X-axis represents the mean of methods α and ß for each breath, while the Y-axis shows the difference (α-ß), indicating how much method α differs from method ß. The red dashed line denotes the bias (mean difference), representing the average discrepancy between the two methods. The green dashed lines indicate the 95% limits of agreement (± 1.96 standard deviations), which encompass the range within which approximately 95% of the differences are expected to fall. No evidence of proportional bias or heteroscedasticity was observed in any of the plots.

Linear regression analysis demonstrated a weak correlation between methods to calculate V̇CO₂ (Table 4B).

Safety and feasibility

No adverse events related to the NAVA catheter were observed. Three patients were excluded due to insufficient EAdi signal quality.

Discussion

The present study demonstrated significant physiological benefits of NAVA over PSV in post-cardiac surgery patients with mild ALI during the weaning phase. The short-term effects of shifting from PSV to NAVA included a reduction in physiologic dead space fraction, along with increased PaO₂/FiO₂ ratio and NVE, while pulmonary shunt fraction remained unchanged. To our knowledge, this is the first study in post-cardiac surgery ALI patients to evaluate the effects of NAVA on physiological dead space, intra-pulmonary shunt fraction, and neuroventilatory efficiency (NVE).

NAVA differs from conventional assist modes by utilizing diaphragmatic electrical activity (EAdi, in µV) as a surrogate for respiratory drive, rather than relying on flow or pressure triggers. This allows pressure delivery to be synchronized and proportionally adjusted to the EAdi signal during the inspiratory phase. The NAVA mode is previously described in detail8,9,30,31,32. Compared to PSV and other assist modes, NAVA offers several benefits during weaning in patients with ALI, ARDS, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, including improved patient–ventilator synchrony and comfort, reduced dorsal atelectasis through more effective activation of the dorsal diaphragm, and a lower risk of over-assistance and diaphragm atrophy31. Studies have also reported shorter duration of mechanical ventilation in selected ICU patients9, less need for non-invasive ventilation after extubation5 and even lower hospital mortality9.

NAVA vs. PSV: pulmonary shunt

In this study, shifting from PSV to NAVA did not affect shunt fraction. Previous studies have linked NAVA with shorter durations of mechanical ventilation9, possibly through enhanced recruitment of dorsal atelectasis mediated by increased dorsal diaphragm activation. This mechanism is particularly relevant in supine ICU patients, as post-cardiac surgery atelectasis often involves the dorso-basal lung regions1,33. Although recruitment can improve V/Q matching and oxygenation, potentially reducing shunt, the lack of change in our study likely reflects an absence of severe lung injury, given the low baseline shunt fraction of approximately 14% and FiO₂ of 40%. The measurement technique may also have lacked sensitivity, or the improved PaO₂/FiO₂ ratio may rather been due to reduced dead space than shunt. A prior meta-analysis9 concluded that the most pronounced benefits of NAVA are seen in patients with more challenging weaning, unlike our population.

Early post-cardiac surgery, shunt fractions typically range from 14 to 20%7,34. In contrast, in a cohort of non-recruited patients with more severe ALI following cardiac surgery, shunt fractions approached 40% with FiO₂ levels around 70% and were partially reversible with prone positioning35. In this study, transitioning from PSV to NAVA did not change the shunt fraction but increased the PaO₂/FiO₂ ratio, likely reflecting improved V/Q matching. The modest yet reversible rise suggests enhanced gas exchange efficiency during NAVA, which, if sustained, may reduce oxygen or ventilatory requirements in more compromised patients. Improved oxygenation during NAVA has also been reported in a 24-h crossover study after abdominal surgery36.

NAVA vs. PSV: physiological dead space

Physiological dead space, assessed via calculated volumetric capnography (VCAP-CALC), was 5% lower during NAVA compared with PSV in the present study. Although modest, this reduction most likely reflects partial recruitment of dorso-basal atelectasis, supported by an increase in dorsal end-expiratory lung volume (ΔEELVdorsal), indicative of improved dorsal aeration1,33. This recruitment enhanced V/Q matching and contributed to the improved oxygenation observed during NAVA. We speculate that the more homogeneous ventilation pattern associated with NAVA37, although not confirmed in our data (Table 2, Suppl. Fig. 4), reduces anterior alveolar overdistension and lower alveolar pressure on pulmonary capillaries, thereby enhancing capillary perfusion, reducing dead space, and improving the PaO₂/FiO₂ ratio. Such redistribution promoting more uniform lung stress and strain might also help mitigate ventilator-induced lung injury38–a hypothesis that warrants evaluation in future studies incorporating direct measures of these parameters.

The calculated mean differences and confidence intervals further substantiate the clinical relevance of this finding. The approximately 5% absolute reduction in dead space corresponds to an 8–9% relative improvement in ventilatory efficiency. Assuming that anatomical dead space remains constant, this reduction predominantly reflects a decrease in alveolar dead space, an effect of roughly 10%. Although numerically modest, changes of this magnitude are physiologically meaningful. In the landmark study by Nuckton et al., the difference in dead space fraction between survivors and non-survivors of early ARDS was 0.09 (0.54 vs 0.63)39. Thus, the present within-subject improvement during NAVA, supported by the reproducibility of the mean paired differences, reinforces the interpretation of a genuine enhancement in alveolar ventilation and V/Q matching.

Previous studies have reported physiological dead space values during mechanical ventilation shortly after cardiac surgery40,41,42, as well as after extubation34, but not during NAVA ventilation. In a study by Blankman and coworkers40, patients admitted to the cardiothoracic intensive care unit underwent lung recruitment, and at a PEEP level of 10 cmH₂O, the physiological dead space was 0.53 (VCAP), compared to 0.59 (VCAP-CALC) during NAVA in our study, supporting the interpretation of only mild ALI in the present cohort. Furthermore, VD/VT values between 0.30 and 0.45 have been reported during controlled MV in the early postoperative period following cardiac surgery34,42.

Linear regression analysis comparing the calculated Volumetric Capnography (VCAP-CALC) and the Bohr-Enghoff Equation demonstrated a strong correlation. However, the Bohr-Enghoff estimates did not reach statistical significance, likely reflecting methodological limitations, as mixed expired CO₂ (P̅ECO₂) was indirectly derived from oxygen consumption and an assumed respiratory quotient of 0.8 (consistent with values reported after cardiac surgery34). As this approach assumes metabolic steady state and uniform gas exchange, minor deviations could have introduced variability and reduced sensitivity to within-subject changes. In contrast, volumetric capnography defines airway and alveolar dead space from the CO₂ waveform on a breath-by-breath basis, providing a more sensitive and physiologically responsive estimate. Notably, dead space fraction determined by volumetric capnography is regarded as the clinical gold standard43,44 and has been shown to predict mortality in early ARDS independently of oxygenation45. Accordingly, we consider VCAP-CALC the most adequate and reliable method for this analysis.

NAVA vs. PSV: electrical impedance tomography (EIT)

EIT is a well-established method for assessing regional lung aeration and is previously described in detail1. In the present study, EIT-derived variables including dorsal tidal volume, Center of Ventilation, and Intratidal Variation observed no redistribution toward the dependent lung regions during NAVA. This contrasts with previous findings of dorsal redistribution during NAVA in ALI patients treated in neurointensive care46 and general ICU settings37,47. While speculative, this discrepancy may reflect factors including deeper sedation48, milder ALI severity, shorter observation periods, or differences in patient selection. In contrast, ΔEELVdorsal, a reliable marker of dorso-basal aeration and atelectasis1, detected a modest increase during NAVA compared with PSV1, followed by a decrease during PSV2, indicating dorsal recruitment with subsequent derecruitment. Although absolute EELVdorsal changes were small, their directionality was highly consistent: ten of twelve patients increased EELVdorsal from PSV1 to NAVA, and eight decreased when returning to PSV2. The parallel improvement and decline in PaO2/FiO2 ratio reinforce that these shifts represented genuine physiological changes rather than measurement variability, suggesting that NAVA stabilizes and modestly recruits dependent lung regions. From a clinical perspective, the reproducibility and directionality of these within-subject responses are of greater interpretative value than their absolute magnitude, as they demonstrate a coherent and reversible physiological effect.

NAVA vs. PSV: neuroventilatory efficiency (NVE)

In the present study, NVE was calculated as the ratio of tidal volume to the mean EAdi (VT/EAdiMEAN) per breath. This measure is considered to reflect diaphragm efficiency, meaning the coupling of drive (EAdi) to effort, resulting in synchronized diaphragm muscle force. NVE has previously shown best predictive power for extubation success in a general ICU population with diverse causes of respiratory failure49. In a mixed cohort of patients with ALI receiving prolonged mechanical ventilation, NAVA but not PSV improved NVE50. Additionally, monitoring VT/EAdiMEAN during PEEP titration has been used to identify optimal PEEP levels associated with minimal diaphragmatic cost of breathing51. In the present study, NVE was 14% higher during the NAVA period compared with PSV1, supporting the interpretation of improved diaphragmatic efficiency. This enhanced coupling between respiratory drive and muscular effort likely reflect minor dorsal lung recruitment, resulting in an increase in local compliance. Notably, data on the effects of various modes of mechanical ventilation on NVE has not previously been presented following cardiac surgery.

NAVA vs. PSV in tracheotomized patients

In a previous general ICU study, 99 patients with difficult weaning were randomized to receive either PSV or NAVA6. Interestingly, only the tracheotomized subgroup (n = 34) showed benefit from NAVA, including shorter weaning duration and more ventilator-free days at day 28. In our experience, tracheotomized patients require less sedation, potentially enhancing the effectiveness of NAVA. In the present study, only two tracheotomized patients were included, and sedation depth was more pronounced (median RASS –3) compared to RASS –2 reported by Ling and co-workers6. This difference may have influenced the limited physiological differences observed between PSV and NAVA. Unlike PSV, NAVA relies predominantly on diaphragmatic effort, which can be counteracted by too deep sedation48,52. Indeed, the advantage of NAVA has been attributed to reduced sedation requirements, as sedation can be more precisely titrated through continuous monitoring of respiratory drive7.

Metabolic production of carbon dioxide

The comparison between estimates of V̇CO₂ revealed no significant correlations. This likely reflects the distinct physiological processes each method captures: arterio-venous oxygen content difference (Ca-v O2) quantifies total metabolic CO₂ elimination, whereas capnography measures the CO₂ actually exhaled at the airway opening. The adjusted Harris–Benedict estimate diverged from both measured methods, supporting their stronger basis in physiological measurement than theoretical estimation. However, comparisons must be interpreted with caution, as no absolute reference standard for V̇CO₂ was available.

Limitations and strengths

The primary limitation of the study was the brief measurement periods, a common constraint in physiological studies that require time for equilibrium to be achieved. Nevertheless, switching from PSV to NAVA produced statistically significant changes, yielding new physiological and clinical insights. The within-person crossover design provided important advantages, including reduced inter-individual variability and the use of paired statistical analyses, which increased statistical power and allowed for a smaller sample size. However, this design also carries potential drawbacks, such as carry-over effects and the absence of blinding. In addition, the inclusion of patients with only mild ALI may have contributed to the modest differences observed between ventilation modes.

Finally, a limitation was the reliance on calculated rather than directly measured volumetric capnography, although the applied method demonstrated a low coefficient of variation. Specifically, there are several potential limitations related to the temporal alignment of the CO₂ signal from the standalone side-stream capnometer with the ventilator-derived flow signal. The flow signal was sampled at 200 Hz, whereas the CO₂ signal was acquired at 50 Hz, and side-stream sampling inherently smooths the capnogram53. In addition, the calculation of first and second derivatives involves an internal smoothing algorithm. The corrugated connector between the Y-piece and the CO₂ sampling line introduce a minor alignment bias, leading to slight overestimation of dead-space volumes. However, consistent use of the same alignment procedure across all subjects and ventilation phases minimized the potential bias in within-subject comparisons.

Conclusions

NAVA is a safe and feasible ventilatory mode after cardiac surgery. Swan–Ganz catheterization enables calculation of pulmonary shunt and Enghoff’s physiological dead space, aiding weaning decisions. A novel method for converting time-based capnography to volumetric values may be more sensitive but is time-consuming. In this short-term physiological study, NAVA offered modest yet significant benefits over PSV, including reduced dead space fraction, improved lung oxygenation, and enhanced neuroventilatory efficiency. These findings suggest improved V/Q matching, primarily driven by dead space reduction. The potential implications for postoperative recovery and long-term outcomes merit evaluation in larger clinical studies.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to institutional and ethical restrictions related to patient confidentiality. However, de-identified data are stored in a secure, controlled-access repository at Sahlgrenska University Hospital. Access to the data can be granted upon reasonable request from the corresponding author, subject to approval by the relevant institutional data protection authorities.

References

Martinsson, A., Houltz, E., Wallinder, A., Lindgren, S. & Thoren, A. Lung recruitment in the prone position after cardiac surgery: a randomised controlled study. Br. J. Anaesth. 126, 1067–1074 (2021).

Tenling, A., Hachenberg, T., Tyden, H., Wegenius, G. & Hedenstierna, G. Atelectasis and gas exchange after cardiac surgery. Anesthesiology 89, 371–378 (1998).

Matthay, M. A. & Wiener-Kronish, J. P. Respiratory management after cardiac surgery. Chest 95, 424–434 (1989).

Huffmyer, J. L. & Groves, D. S. Pulmonary complications of cardiopulmonary bypass. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Anaesthesiol. 29, 163–175 (2015).

Demoule, A. et al. Neurally adjusted ventilatory assist as an alternative to pressure support ventilation in adults: a French multicentre randomized trial. Intensive Care Med. 42, 1723–1732 (2016).

Liu, L. et al. Neurally adjusted ventilatory assist versus pressure support ventilation in difficult weaning: a randomized trial. Anesthesiology 132, 1482–1493 (2020).

Mandyam, S. et al. Neurally adjusted ventilatory assist versus pressure support ventilation: a comprehensive review. J. Intensive Care Med. 39, 1194–1203 (2024).

Wu, M., Yuan, X., Liu, L. & Yang, Y. Neurally adjusted ventilatory assist vs. conventional mechanical ventilation in adults and children with acute respiratory failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Med. (Lausanne) 9, 814245 (2022).

Yuan, X. et al. Neurally adjusted ventilatory assist as a weaning mode for adults with invasive mechanical ventilation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Care 25, 222 (2021).

Force, A. D. T. et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the Berlin definition. JAMA 307, 2526–2533 (2012).

Berggren, S. M. The oxygen deficit of arterial blood cause by non-ventilating parts of the lung. Acta Physiol. Scand. 4, 92 (1942).

Hüfner, G. Neue Versuche zur Bestimmung der Sauerstoffcapacität des Blutfarbstoffs. Archiv. Pathol. Anatomie Physiol. Klinische Med. 55, 130–176 (1894).

Fenn, W. O., Rahn, H. & Otis, A. B. A theoretical study of the composition of the alveolar air at altitude. Am. J. Physiol. 146, 637–653 (1946).

Bohr, C. Ueber die Lungenathmung. Skand. Archiv. Physiol. 1, 236–268 (1891).

Enghoff, H. Volumen inefficax. Upsala Lakaref Forh 84, 191–218 (1938).

Kagan, I. et al. Validation of carbon dioxide production (VCO(2)) as a tool to calculate resting energy expenditure (REE) in mechanically ventilated critically ill patients: a retrospective observational study. Crit. Care 22, 186 (2018).

Hardman, J. G. & Aitkenhead, A. R. Estimating alveolar dead space from the arterial to end-tidal CO(2) gradient: a modeling analysis. Anesth. Analg. 97, 1846–1851 (2003).

Severinghaus, J. W. & Stupfel, M. Alveolar dead space as an index of distribution of blood flow in pulmonary capillaries. J. Appl. Physiol. 10, 335–348 (1957).

Fowler, W. S. Lung function studies; the respiratory dead space. Am. J. Physiol. 154, 405–416 (1948).

Jaffe, M. B. Using the features of the time and volumetric capnogram for classification and prediction. J. Clin. Monit. Comput. 31, 19–41 (2017).

Herry, C. L., Townsend, D., Green, G. C., Bravi, A. & Seely, A. J. Segmentation and classification of capnograms: application in respiratory variability analysis. Physiol. Meas. 35, 2343–2358 (2014).

Verscheure, S., Massion, P. B., Verschuren, F., Damas, P. & Magder, S. Volumetric capnography: lessons from the past and current clinical applications. Crit. Care 20, 184 (2016).

Tang, Y., Turner, M. J. & Baker, A. B. A new equal area method to calculate and represent physiologic, anatomical, and alveolar dead spaces. Anesthesiology 104, 696–700 (2006).

Douglas, C. G. Proceedings of the physiological society: March 18, 1911. J. Physiol. 42, xvii–xxii (1911).

Harris, J. A. B. F. A Biometric Study of Basal Metabolism in Man (Carnegie institution of Washington, 1919).

Roza, A. M. & Shizgal, H. M. The Harris Benedict equation reevaluated: resting energy requirements and the body cell mass. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 40, 168–182 (1984).

Long, C. L., Schaffel, N., Geiger, J. W., Schiller, W. R. & Blakemore, W. S. Metabolic response to injury and illness: estimation of energy and protein needs from indirect calorimetry and nitrogen balance. JPEN J. Parenter. Enteral. Nutr. 3, 452–456 (1979).

Weir, J. B. New methods for calculating metabolic rate with special reference to protein metabolism. J. Physiol. 109, 1–9 (1949).

Martinsson, A. et al. Inspiratory and end-expiratory effects of lung recruitment in the prone position on dorsal lung aeration - new physiological insights in a secondary analysis of a randomised controlled study in post-cardiac surgery patients. BJA Open 4, 100105 (2022).

Terzi, N. et al. Clinical review: Update on neurally adjusted ventilatory assist – report of a round-table conference. Crit. Care 216, 1–16 (2012).

Umbrello, M., Antonucci, E. & Muttini, S. Neurally adjusted ventilatory assist in acute respiratory failure-a narrative review. J. Clin. Med. 11, 1863 (2022).

Weiyun, T., Linli, S. & Liuzhao, C. Neurally-adjusted ventilatory assist versus pressure support ventilation during noninvasive ventilation. Respir. Care 67, 879–888 (2022).

Martinsson, A. et al. Inspiratory and end-expiratory effects of lung recruitment in the prone position on dorsal lung aeration – new physiological insights in a secondary analysis of a randomised controlled study in post-cardiac surgery patients. BJA Open 4, 100105 (2022).

Tenling, A. H. T., Tyden, H. & Wegenius, G. Atelectasis and gas exchange after cardiac surgery. Anesthesiology 89, 371–378 (1998).

Brussel, T. et al. Mechanical ventilation in the prone position for acute respiratory failure after cardiac surgery. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 7, 541–546 (1993).

Coisel, Y. et al. Neurally adjusted ventilatory assist in critically ill postoperative patients- a crossover randomized study. Anesthesiology 113, 925–935 (2010).

Blankman, P., Hasan, D., van Mourik, M. S. & Gommers, D. Ventilation distribution measured with EIT at varying levels of pressure support and neurally adjusted ventilatory assist in patients with ALI. Intensive Care Med. 39, 1057–1062 (2013).

Chiumello, D. et al. Lung stress and strain during mechanical ventilation for acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 178, 346–355 (2008).

Nuckton, T. J. et al. Pulmonary dead-space fraction as a risk factor for death in the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 346, 1281–1286 (2002).

Blankman, P. et al. Detection of optimal PEEP for equal distribution of tidal volume by volumetric capnography and electrical impedance tomography during decreasing levels of PEEP in post cardiac-surgery patients. Br. J. Anaesth. 116, 862–869 (2016).

Doorduin, J. et al. Assessment of dead-space ventilation in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome: a prospective observational study. Crit. Care 20, 121 (2016).

Petak, F. et al. Dopamine reverses lung function deterioration after cardiopulmonary bypass without affecting gas exchange. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 36, 1047–1055 (2022).

Tusman, G., Sipmann, F. S. & Bohm, S. H. Rationale of dead space measurement by volumetric capnography. Anesth. Analg. 114, 866–874 (2012).

Kremeier, P., Bohm, S. H. & Tusman, G. Clinical use of volumetric capnography in mechanically ventilated patients. J. Clin. Monit. Comput. 34, 7–16 (2020).

Slobod, D., Damia, A., Leali, M., Spinelli, E. & Mauri, T. Pathophysiology and clinical meaning of ventilation-perfusion mismatch in the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Biology (Basel) 12, 67 (2022).

Campoccia Jalde, F. et al. Standardized unloading of respiratory muscles during neurally adjusted ventilatory assist: a randomized crossover pilot study. Anesthesiology 129, 769–777 (2018).

Sun, Q. et al. Effects of neurally adjusted ventilatory assist on air distribution and dead space in patients with acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Crit. Care 21, 126 (2017).

Vaschetto, R. et al. Effects of propofol on patient-ventilator synchrony and interaction during pressure support ventilation and neurally adjusted ventilatory assist. Crit. Care Med. 42, 74–82 (2014).

Liu, L. et al. Neuroventilatory efficiency and extubation readiness in critically ill patients. Crit. Care 16, R143 (2012).

Di Mussi, R. et al. Impact of prolonged assisted ventilation on diaphragmatic efficiency: NAVA versus PSV. Crit. Care 20, 1 (2016).

Passath, C. et al. Physiologic response to changing positive end-expiratory pressure during neurally adjusted ventilatory assist in sedated, critically ill adults. Chest 138, 578–587 (2010).

Cecchini, J., Schmidt, M., Demoule, A. & Similowski, T. Increased diaphragmatic contribution to inspiratory effort during neurally adjusted ventilatory assistance versus pressure support an electromyographic study. Anesthesiology 121, 1028–1036 (2014).

Balogh, A. L. et al. Capnogram slope and ventilation dead space parameters: comparison of mainstream and sidestream techniques. Br. J. Anaesth. 117, 109–117 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We would like to extend our sincerest gratitude to Ola Stenqvist for generously sharing his profound insights into respiratory physiology and his talent for bridging theory with clinical application through thoughtful calculation and interpretation.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Gothenburg. For this project, we received research grants from the Sahlgrenska University Hospital foundations (SU-961030, SU-971601), The Gothenburg Society of medicine (GLS-972306, GLS-999058), and the Swedish Heart–Lung Foundation (HjLfonden 20240788).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.M., J.S and A.T. conceived the study and contributed to its design and methodology. A.M., J.S and A.T. were responsible for data collection and curation. A.M. performed the formal analysis and drafted the original manuscript. A.T., A.W., S.-E.R., J.O., and J.S. contributed to formal analysis and critical review and editing of the manuscript. A.M and J.O. designed and executed the statistical analyses. A.T., J.S., A.W., and S.-E.R. provided supervision throughout the project. A.M., A.T., and J.S. acquired funding. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript and agree to be personally accountable for their contributions and the integrity of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Regional Ethical Board in Gothenburg (Dnr:581-14) and conducted in accordance with the principles of the Helsinki Declaration. As the study inclusion criteria required prolonged postoperative mechanical ventilation under sedation, informed consent to participate was obtained from the patients’ nearest relatives.

Consent for publication

Informed consent for publication of anonymized clinical information and images was obtained from the patients’ nearest relatives. All authors meet ICMJE authorship criteria, have reviewed and approved the final manuscript, and consent to its publication.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Martinsson, A., Lundholm, C., Ricksten, SE. et al. Neurally adjusted ventilatory assist vs pressure support ventilation: short-term effects on shunt and dead space after cardiac surgery. Sci Rep 15, 44234 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33097-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33097-1