Abstract

Accurate detection of low-frequency variants utilizing next-generation sequencing (NGS) is of paramount importance in both biomedical research and clinical diagnosis. However, its analytical sensitivity is impeded by NGS’s inherently high error rates. An efficient solution employs unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) to tag individual DNA molecules before amplification to mitigate NGS errors. Nevertheless, UMIs are prone to collisions and amplification- or sequencing-induced errors, leading to the inaccurate clustering of UMI-tagged data. Multiple UMI clustering tools have been proposed to address these challenges; however, a systematic evaluation of their impact on low-frequency variant detection remains lacking. Here, we conducted a comprehensive benchmarking of eight UMI clustering tools—AmpUMI, Calib, CD-HIT, Du Novo, Rainbow, Starcode, UMICollapse, and UMI-Tools—utilizing simulated, reference, and sample datasets to evaluate their clustering efficiency, low-frequency variant detection accuracy, and computational performance. UMI utilization and read family counts are largely consistent across tools, while data loss differs markedly among clustering algorithms. The sensitivities of all tools, except AmpUMI, are influenced by both variant allele frequencies (VAFs) and sequencing depths. Conversely, the precisions and F1 scores of most tools—excluding AmpUMI, CD-HIT, and UMICollapse—exhibit a stronger dependence on sequencing depth as VAFs decreased. Furthermore, UMI clustering tools demonstrate a substantial reduction in false-positive (FP) calls across datasets. Concerning computational efficiency, AmpUMI achieves the fastest execution, Rainbow exhibits the lowest memory consumption, and Calib performs robustly in both aspects, particularly on small datasets. Overall, Calib exhibits the most balanced performance and is recommended for UMI clustering in low-frequency variant calling. These findings may provide valuable insights for improving variant detection and advancing the development of UMI clustering algorithms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has dramatically revolutionized biological research and clinical fields by allowing the simultaneous detection of significant genetic variants in multiple samples1,2,3. It is routinely employed to detect DNA sequence variants with an allele frequency of ≥ 5%4. However, the intrinsic error rate of NGS, typically ranging from 0.1 to 1%, substantially impedes the detection of low-frequency variants (< 1%), as authentic variants are often masked by NGS errors originating from library preparation and sequencing, hindering their reliable identification5,6. Concurrently, the demand for highly sensitive detection of low-frequency variants has been rapidly escalating in both research and clinical contexts, as accumulating evidence indicates that low-frequency variants play pivotal roles in cancer biology, including non-invasive cancer diagnostics, cancer therapy guidance, and post-treatment monitoring5,7,8—as well as in a spectrum of biomedical fields such as early diagnosis of diseases by drug-resistance or organ transplant rejection9,10,11, prenatal diagnosis12,13, aging14, and forensic analysis15.

Numerous error suppression strategies leveraging unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) have been developed in recent years to improve the sensitivity and accuracy of NGS in detecting low-frequency variants16,17,18,19,20,21. In these approaches, each original DNA molecule is uniquely tagged with a UMI prior to amplification, enabling precise tracking of individual template molecules throughout the sequencing workflow16,17. The UMI-tagged molecules subsequently undergo PCR amplification and are then subjected to high-throughput sequencing. During data analysis, these approaches require an initial pre-processing step to group reads from the same molecule into a single family by clustering them based on their UMIs. After this clustering, true variants can be distinguished from sequencing errors utilizing an overlap layout consensus approach applied to the reads within each cluster. Accurate clustering markedly enhances the reliability of downstream variant calling and mutation detection16,17. Previous studies have demonstrated that UMI-based strategies enable detection of ultra-low frequency variants, mitigate amplification bias, and improve both the accuracy and quantitative fidelity of downstream variant analyses20,22,23. However, UMIs may collide, whereby distinct molecules inadvertently receive identical tags, leading to the undercounting, loss, or misestimation of variants. Furthermore, UMIs are also susceptible to PCR and sequencing errors, leading to the discovery of false (erroneous) variants and a potential loss of a significant part of the generated data24,25.

A range of computational frameworks for UMI clustering has been developed to address these challenges. Alignment-based tools such as UMI-tools24 and UMICollapse26 perform reference-based alignment followed by UMI clustering utilizing both alignment coordinates and UMI sequence similarity. UMI-Tools applies a network-based clustering strategy that integrates UMI abundance and sequence similarity, effectively mitigating the overestimation of true UMI counts. However, it relies solely on positional partitioning to resolve UMI collisions, which may limit its accuracy24. UMICollapse employs a network-based clustering algorithm adapted from UMI-Tools24 to avoid inaccurately overestimating true UMIs26. However, these alignment-based approaches are typically computationally intensive due to the requirement of aligning to a reference genome. In contrast, alignment-free frameworks, such as Du Novo27, skip the alignment step and cluster reads directly based on UMI sequence similarity, whereas others (e.g., CD-HIT28, Starcode29, Rainbow30, Calib23, and AmpUMI31 perform clustering using the similarity across the entire read sequence, including UMI regions. These approaches offer improved computational efficiency and reduced dependency on reference alignment accuracy. An overview of these computational frameworks is provided in Table 1. Among alignment-free tools, Du Novo groups reads by the similarity of their UMIs to form single-strand families and performs multiple-sequence alignment within each family to generate single-strand consensus sequences32. In contrast to Du Novo, other alignment-free approaches perform clustering based on similarity across the entire read sequences rather than barcode regions, although their underlying algorithmic frameworks differ considerably. CD-HIT employs a greedy incremental algorithm with sequence identity thresholding to facilitate efficient clustering of datasets28. Starcode implements a message passing as the default clustering algorithm to iteratively collapse similar sequences into representative “canonical” sequences29. Rainbow initially clusters reads employing a spaced seed methodology; it then implements a heterozygote-calling-like strategy to subdivide clusters and finally merges sibling leaves in a bottom-up manner along a guided tree30. Calib employs a graph-based clustering paradigm utilizing locality-sensitive hashing and MinHashing, in which edges are defined jointly by both barcode and read sequence similarity23. AmpUMI clusters reads by using a threshold latent variable model, which facilitates the design and interpretation of UMI-based amplicon sequencing studies31. These alignment-free tools bypass the requirement for alignments, thereby enhancing computational efficiency and scalability for large sequencing datasets. However, these clustering tools grounded in distinct algorithmic paradigms, leading to heterogeneous performance in terms of low-frequency variant detection accuracy, UMI clustering efficiency, runtime, and memory consumption.

Several investigations have benchmarked diverse UMI clustering tools developed for error suppression and low-frequency variant detection. However, a systematic evaluation encompassing clustering accuracy, performance of low-frequency variant calling, execution time, and memory utilization across simulated, reference, and sample data remains lacking. For instance, one study compared tools such as CD-HIT, Rainbow, Starcode, Du novo, and UMI-Tools against Calib, utilizing only simulated data and reported that their performance was highly dependent on the parameter choices23. Another study evaluated only two alignment-based UMI clustering tools, UMI-tools and UMICollapse, and excluded alignment-free approaches26. A subsequent report focus on several partially released tools (e.g., Calib, Naïve, Starcode, and UMI-tools) and found that each exhibited specific benefits and inherent drawbacks25. Despite these efforts, a comprehensive benchmarking analysis of UMI clustering tools has yet to be reported. To address this gap, we present a systematic evaluation of eight representative UMI clustering tools encompassing both alignment-based and alignment-free frameworks, including AmpUMI, Calib, CD-HIT, Du Novo, Rainbow, Starcode, UMICollapse, and UMI-tools. The principal features of each tool are summarized in Table 1. We evaluated their performance across multiple sequencing data types—including simulated, reference, and sample data—to systematically assess clustering efficiency, low-frequency variant detection accuracy, runtime, and memory consumption. This comprehensive analysis provides practical insights for accurate low-frequency variant detection and future optimization of UMI clustering algorithm design.

Results

Effects of UMI clustering tools

UMI clustering tools enable the consolidation of reads from the same original molecule into read families based on shared UMI tags. This clustering process is critical for enhancing the precision of downstream variant detection and mutation analysis23. However, inaccurate clustering may introduce spurious variant calls and cause substantial data loss, thereby compromising the detection of ultra-low-frequency variants24,25. To assess these effects, we systematically benchmarked the performance of diverse UMI clustering tools across simulated, reference and sample data. We evaluated eight widely ultilized open-source UMI clustering tools—UMICollapse, UMI-tools, AmpUMI, Calib, CD-HIT, Du Novo, Starcode, and Rainbow—each implementing distinct clustering strategies under default parameters (minimum read family size ≥ 2). The evaluation was performed employing a simulated dataset with a sequencing depth of 20,000X at a VAF of 1%, a reference dataset (N0015), and a sample dataset (M0253). Performance metrics included UMI utilization (the proportion of UMIs retained after clustering) and the total number of read families generated. Both UMI utilization and read family counts varied substantially among the clustering tools (Table 2). AmpUMI, Calib, CD-HIT, Du Novo, and Starcode maintain full UMI utilization (100%), whereas Rainbow exhibits slightly reduced rates (92.62–99.62%). On the other hand, all tools exhibit consistent read family counts except CD-HIT, Rainbow, and UMICollapse (Table 2).

Subsequently, we systematically analyzed the distribution of family size (number of reads in a read family) across six of the eight tools capable of generating cluster information. The results demonstrate that data loss in the datasets N0015 and M0253 were more commonly associated with UMI clustering tools compared to the simulated dataset (Table 2; Fig. 1A). Specifically, in the reference datasets, single-read families (family size = 1) and larger clusters (family size > 3) were predominant, whereas the simulated dataset was dominated by families with sizes exceeding three. Since at least two reads per read family were required to construct a consensus sequence, families comprising fewer than two reads were discarded during processing, thereby contributing to substantial data loss. Finally, SiNVICT (v1.0), a variant caller specifically designed for low-frequency variant calling, was employed to call variants and its performance was evaluated based on true-positive (TP) and false-positive (FP) rates. While clustering tools exert little effect on the number of TPs, their configuration markedly affects the incidence of FPs, as evidenced by substantial inter-tool variability.

Effects of the eight clustering tools. (A) Distribution of family sizes in different UMI clustering tools in the simulated data, standard data (N0015), and sample data (M0253). (B) The sensitivities of the eight clustering tools at various VAF levels and sequencing depths. Note that AmpUMI exhibited markedly inferior performance and has been omitted from the plot for clarity.

Performance of UMI clustering tools varies with VAF and sequencing depth in simulated datasets

UMI-based sequencing strategies typically employ redundant sequencing to generate multiple reads originating from the same DNA molecule, which are subsequently grouped by identical UMIs to form molecular read families. Strand-specific consensus sequences are generated independently for each read family and subsequently compared between complementary strands. This duplex consensus principle enables confident discrimination of true variants from sequencing and PCR artifacts, as complementary errors are statistically unlikely to occur at identical positions across both DNA strands17,33. The performance of UMI clustering tools was systematically evaluated utilizing the simulated datasets spanning a broad range of VAFs (10%, 5%, 1%, 0.5%, 0.25%, 0.1%, 0.05%, and 0.025%) and sequencing depths (1000X, 5000X, 10,000X, 15,000X, 20,000X, and 25,000X) (Fig. 1B). At higher VAFs (≥ 1%), sequencing depth exerts negligible influence on clustering performance and variant detection accuracy. However, as VAFs decrease from 1% to 0.05%, a pronounced decline in sensitivity is observed, particularly under lower sequencing depths, reflecting the increasing challenge of distinguishing true low-frequency variants from background noise. Overall, the sensitivities of all clustering tools—except AmpUMI—are influenced by both the VAFs and the sequencing depths, with lower-frequency variants requiring greater coverage for reliable identification.

Additionally, the precision of each tool across varying VAFs and sequencing depths is presented in Fig. 2. AmpUMI, CD-HIT, and UMICollapse consistently exhibit low precision across all sequencing depths, whereas the precision of others shows considerable variation with decreasing VAFs. Specifically, as the VAFs drop, the precision of all clustering tools—except AmpUMI, CD-HIT, and UMICollapse—becomes more dependent on sequencing depths. Finally, the F1 scores of each tool across varying VAFs and sequencing depths are illustrated in Fig. 3. Consistent with precision trends, AmpUMI, CD-HIT, and UMICollapse maintain low F1 scoresacross all depths, whereas other tools exhibit depth-dependent fluctuations as VAF decreased, indicating concordance between declines in precision and overall detection performance.

Performance of UMI clustering tools in variant calling utilizing a reference dataset

We next systematically evaluated the performance of eight UMI clustering tools for low-frequency variant calling using reference dataset N0015. optimize computational efficiency and memory usage, the analysis was restricted to chromosome 1, which harbors 338 annotated variants. SiNVICT—an established variant caller designed for low-frequency variant calling—was applied to consensus reads generated by each clustering tool, utilizing platform error rate parameters of 0.01, 0.001, and 0.0001, respectively. SiNVICT employs a Poisson distribution to call variants based on expected platform-specific sequencing error rates34. For comparison, SiNVICT was also applied to the original unclustered reads as a baseline. As illustrated in Fig. 4A, when the sequencing error rate decreased from 0.01 to 0.0001, the number of verified or reported variants identified—either with or without UMI clustering—revealed no appreciable variation across error-rate settings. However, the number of FPs identified by UMI clustering tools is lower than in unclustered data, suggesting that UMI-based clustering has substantial potential to suppress false-positive calls. Among the eight clustering tools, Calib exhibits superior performance, achieving a high number of verified variants without a proportional increase in FPs. Conversely, CD-HIT performed suboptimally, yielding the fewest verified variants and the highest number of FPs.

Variant calls using different clustering tools on various datasets at different sequencing error ratios (0.01, 0.001, and 0.0001). The X-axis is presented on a logarithmic scale, representing the number of calls. (A) Reference dataset N0015, which contains 338 known variants. (B) Sample dataset M0253, which contains 37 known variants.

Performance of UMI clustering tools in low-frequency variant calling utilizing sample data

To further evaluate the performance of eight UMI clustering tools in low-frequency variant calling employing empirical sample data, we utilized the M0253 dataset, which contains 37 verified or reported variants with a VAF of approximately 0.5%. Each tool was first employed to perform UMI clustering, followed by variant calling using SiNVICT (v1.0) under sequencing error rates of 0.01, 0.001, and 0.0001, respectively. Results are summarized in Fig. 4B. As the sequencing error rate decreases from 0.01 to 0.0001, most clustering tools—except CD-HIT and Du Novo—identifies a greater number of true variants compared to the unclustered control. Concurrently, their false-positive counts are consistently lower than those obtained without clustering. These findings demonstrate that, apart from CD-HIT and Du Novo, most clustering tools effectively suppress FPs during variant calling (Fig. 4B). Among the eight clustering tools, CD-HIT and UMICollapse detect the highest numbers of TPs but also exhibit the highest and second-highest FP counts, at an error rate of 0.01. In contrast, Calib, UMI-Tools, Du Novo, Starcode, AmpUMI, and Rainbow report four verified or reported variants while maintaining reduced FP levels. At a sequencing error rate of 0.001, UMICollapse producsthe largest number of TPs but also the highest FP rate, whereas CD-HIT yields the fewest verified variants yet exhibits the second-highest FP count. This disparity became even more pronounced at an expected error rate of 0.0001. At the lowest error rate (0.0001), Du Novo, Rainbow, AmpUMI, Starcode, and UMI-Tools successfully recover over 21 verified variants while maintaining moderate FPs. In contrast, Calib identifies 28 verified variants with the fewest FPs, highlighting its superior accuracy and efficiency for low-frequency variant detection.

Computational efficiency

We conducted a systematic benchmarking analysis of eight UMI clustering tools to assess their computational performance in terms of runtime and memory utilization (Table 3). Each tool was executed on three representative datasets: a simulated dataset (10,000X coverage, 10% VAF), a reference dataset, and a sample dataset. The minimum execution times and memory consumption for each dataset are denoted in bold and shaded in light gray in Table 3.

For small-scale datasets (simulated dataset), Calib exhibits the shortest runtime, whereas UMI-tools is the slowest. Calib also demonstrates the lowest memory footprint, while UMICollapse and UMI-tools exhibit the highest memory consumption. For large-scale datasets (reference and sample datasets), AmpUMI, Rainbow, and Starcode exhibit the shortest execution times, whereas CD-HIT is the slowest. Rainbow and Calib demonstrate superior memory efficiency, whereas UMICollapse requires the largest memory consumption. The elevated memory consumption observed in UMICollapse and UMI-tools likely stems from the inclusion of an alignment step during execution. Overall, AmpUMI exhibits robust performance in execution time across all dataset scales. Rainbow exhibits commendable performance in both execution time and memory utilization for both small and large datasets. Calib demonstrates exceptional efficiency in execution time and memory usage, particularly excelling on small datasets. Considering the trade-off between execution time and memory consumption across datasets of varying scales, Calib represents the most balanced and computationally efficient solution.

Discussion

The detection of low-frequency DNA variants (below 1%) has become increasingly critical in biomedical research and clinical diagnostics. However, conventional NGS platforms remain limited by intrinsic error rates, which obscure authentic low-frequency mutations5. A robust error-correction strategy employs UMIs to label and trace individual template molecules17. The UMI-based strategy involves an initial clustering step that groups reads derived from the same template molecule according to their UMIs. However, UMIs may collide and are prone to PCR or sequencing-induced errors, thus leading to the misestimation of variants25. To address these issues, diverse algorithmic frameworks for UMI clustering have been developed, including AmpUMI, Calib, CD-HIT, Du Novo, Rainbow, Starcode, UMI-Tools, and UMICollapse. Some tools that rely on mapping the reads to a reference genome are computationally intensive. In contrast, alignment-free approaches that cluster reads solely based on UMIs or full read sequences may lead to the underrepresentation, loss, or inaccurate quantification of variants. Notably, despite their essential role in low-frequency variant detection, there has been no comprehensive assessment of UMI clustering tools to date.

In this study, we systematically benchmarked eight UMI clustering frameworks—six alignment-free (AmpUMI, Calib, CD-HIT, Du Novo, Rainbow, and Starcode) and two alignment-based (UMI-tools and UMICollapse)—to comprehensively evaluate their computational and analytical performance. We quantitatively compared clustering efficiency, low-frequency variant calling, execution time, and memory consumption across simulated, reference, and sample data. Marked variation in read family size distribution is observed among datasets. Both the reference and sample datasets exhibit a predominance of singleton read families (family size = 1), whereas the simulated dataset contained comparatively fewer singleton families. The elevated proportion of singleton read families in the reference and sample data is likely attributable to sequencing or PCR errors occurred in the UMI sequences27.

All tools except Rainbow demonstrated comparable UMI utilization efficiency. The reduced UMI utilization observed in Rainbow is likely attributed to the -e (exact-matching threshold) parameter in Rainbow’s clustering module, which controls the stringency of UMI matching during the clustering process30. In addition, CD-HIT exhibits suboptimal performance across all three datasets, showing both reduced clustering efficiency and compromised variant detection accuracy. This limitation likely stems from its fixed 90% sequence identity threshold, which can erroneously merge distinct read families and distort consensus construction. Because consensus generation requires at least two reads per family, singleton families inherently preclude consensus formation, leading to marked data loss. UMI-Tools and Starcode exhibit the highest data loss primarily due to the stringent filtering of read families containing fewer than two members during clustering.

Across simulated datasets spanning multiple variant allele frequencies (VAFs) and sequencing depths, AmpUMI exhibits suboptimal clustering and variant detection performance (Figs. 1, 2 and 3; Tables S3–S8). This discrepancy is likely attributable to the simulated dataset generated by UMI-GEN being incompatible with AmpUMI. When evaluated on reference and sample data, we further observed that as the sequencing error rate decreased from 0.01 to 0.0001, analyses performed without UMI clustering yield substantially higher FP variant calls compared with those incorporating clustering (Fig. 4A and B). This likely reflects the ability of UMI clustering to suppress sequencing and PCR-induced errors, thereby improving the accuracy of low-frequency variant detection17. Furthermore, compared with the simulated dataset at 0.5% VAF, the sample dataset demonstrates a pronounced reduction in variant detection sensitivity. This decrease likely results from the exclusion of singleton read families during filtering, potentially leading to the loss of reads containing critical mutation information.

Among the eight UMI clustering tools, CD-HIT exhibits the fewest TPs and a relatively elevated level of FPs across various sequencing error rates. This may be partly explained by CD-HIT’s reliance on a fixed global sequence identity threshold of 90%. Conversely, Calib exhibits superior clustering performance, achieving a consistently higher TP rate while maintaining the lowest FP rate across all sequencing error levels (Fig. 4). This superior performance is likely attributable to Calib’s graph-based framework, which integrates both UMI and read-level sequence similarity during clustering, thereby enhancing molecular family reconstruction accuracy and overall robustness23.The computational runtime and memory utilization are largely influenced by whether a given tool requires reference-based alignment, as this step substantially increases both processing complexity and data handling overhead. The two alignment-based tools, UMI-Tools and UMICollapse, exhibit markedly lower computational efficiency than alignment-free frameworks in both runtime and memory consumption, primarily owing to the additional computational burden introduced by sequence alignment (Table 3). Specifically, in the smallest dataset (a simulated dataset), Calib demonstrates superior performance over all other clustering tools in both execution time and memory consumption (Table 3) since Calib applies locality-sensitive hashing and MinHashing techniques to construct similarity graphs, making it faster and accurate23. Conversely, CD-HIT exhibits relatively prolonged runtime on the simulated dataset, primarily attributable to the iterative nature of its greedy incremental clustering algorithm, which incurs substantial computational overhead28. Moreover, both Rainbow and Calib demonstrate both Rainbow and Calib exhibit consistently high computational efficiency and favorable memory usage across datasets of varying scales. However, Rainbow is less effective in UMI clustering. When considering the integrated metrics of runtime, memory utilization, and clustering accuracy, Calib represents the most computationally efficient and balanced framework among the evaluated tools.

Conclusions

We conducted a comprehensive benchmarking of eight UMI clustering tools across simulated, reference, and sample datasets, evaluating their performance in UMI clustering efficiency, variant calling efficiency, execution time, and memory consumption. Our findings reveal that UMI utilization and read family counts are strongly influenced by the choice of clustering tool, while data loss is also associated with the specific algorithm employed. For all clustering tools except AmpUMI, sensitivity was positively associated with both VAF and sequencing depth, underscoring the necessity of deeper sequencing to ensure reliable detection of ultra-rare variants. Furthermore, precision and F1 metrics for all tools—except AmpUMI, CD-HIT, and UMICollapse—exhibit parallel dependence on both VAF and sequencing depth. All evaluated UMI clustering tools substantially reduced FP counts, highlighting the effectiveness of UMI-based consensus clustering in error suppression. In terms of computational efficiency, alignment-based tools incur substantially higher runtime and memory overhead than alignment-free approaches. Notably, Calib demonstrates consistently superior overall performance when all evaluation matrices are considered simultaneously. Accordingly, Calib is recommended as a robust and efficient tool for UMI clustering in low-frequency variant detection workflows. Collectively, these findings offer critical benchmarks and methodological insights for enhancing low-frequency variant detection and guiding the future development of UMI clustering algorithms.

Materials and methods

Datasets

To conduct a comprehensive evaluation of the UMI clustering tools, we employed both simulated sequencing data and real sequencing data (Table 4). Simulated datasets containing predefined variants serving as truth sets were generated, and two real datasets representing distinct sequencing data types were included for validation. The real datasets comprised a reference dataset (N0015) and a clinical sample dataset (M0253). The details of the datasets are described in Table 4.

Simulated data

We used UMI-Gen35 to generate paired-end reads with UMI tags. UMI-Gen applied multiple real biological samples to estimate the background error rate and base quality scores at each position, and it then introduced real variants into the final reads. UMI-Gen converts the variant probabilities specified in the variant file into variant frequencies. Subsequently, it calculates the minimum initial number of DNA fragments necessary to incorporate true variants, corresponding to the number of reads containing these variants. UMI-Gen takes three main input parameters: a list of control samples with sequencing alignments stored in sequence alignment/map (SAM) or binary alignment/map (BAM) format, a browser extensible data (BED) file with coordinates of the targeted genomic regions, and a reference genome in FASTA format containing BWA index files. Three control BAM files and a BED file listing the selected regions (Table S1), as described in the original study, were used to estimate background error rates and define the targeted sequencing panel. The Genome Reference Consortium Human Build 37 (GRCh37) was applied as the reference genome and downloaded from UCSC Genome Browser (https://hgdownload.soe.ucsc.edu/goldenPath/hg19/bigZips/latest/hg19.fa.gz). A total of 100known variants with VAFs of 10%, 5%, 1%, 0.5%, 0.25%, 0.1%, 0.05%, and 0.025% were randomly introduced into the simulated reads (Table S2). Additionally, for each VAF, multiple sequencing depths (1000X, 5000X, 10000X, 15000X, 20000X, and 25000X) were simulated to assess the performance of clustering tools under various sequencing depths and VAFs. In total, 48 simulated datasets with different sequencing depths and VAF levels were generated. Each simulated paired-end dataset contained a random 12-bp UMI sequence and an average read length of 110 bp. The resulting R1 and R2 FASTQ files included UMI tags attached to the end of the read name (e.g., @read_name_UMI).

Reference data

The reference data N001536 from Chang Xu et al. was obtained from the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) repository under accession number SRX1742693. The N0015 dataset contained high-confidence variants released by the Genome in a Bottle (GIAB, v3.3.2), with a VAF of approximately 5% at a sequencing depth of 4,825X. This dataset was generated by sequencing a mixture of 10% NA12878 DNA and 90% NA24385 DNA on an Illumina NextSeq 500. Due to the large size of this dataset, we restricted our analysis to chromosome 1, encompassing 338 annotated single-nucleotide variants (SNVs), to ensure computational efficiency.

Sample data

Data M025337 in the study of Chang Xu et al. were downloaded from the NCBI SRA repository under accession number SRR6794144. M0253 was prepared by mixing Horizon Dx’s Tru-Q 7 reference standard (verified 1.3%-tier variants) with Tru-Q 0 231 (wild-type) at a ratio of 1:1 to simulate 0.5% variants at a sequencing depth of 4,980X. The Horizon sample was sequenced with the QIAseq Human Actionable Solid Tumor 232 Panel (QIAGEN; cat. no.r DHS-101Z)37.

Data pre-processing

Prior to clustering, simulated data underwent quality control and adapter trimming utilizing FASTP (v0.23.4) to filter out low-quality reads and remove adapter contamination. Simultaneously, UMIs were extracted from the read names and appended to the corresponding read sequences. For the N0015 and M0253 datasets, preprocessing involved adapter trimming with ReadTrimmer (v1.0), quality control employing FASTP (v0.23.4), and UMI extraction from read names followed by integration into the read sequences.

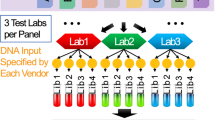

UMI clustering

UMI clustering was conducted employing eight tools, comprising two reference alignment-based tools (UMICollapse and UMI-Tools) and six alignment-free tools (AmpUMI, Calib, CD-HIT, Du·Novo, Starcode, and Rainbow) across simulated, reference and sample datasets to ensure comprehensive performance evaluation. All tools were executed with their default parameter settings to ensure comparability and to avoid biases introduced by manual parameter tuning. Following clustering, the tools produced output files in diverse data formats. Some tools (AmpUMI and UMICollapse) directly generated consensus sequences during clustering, while others (including Calib, CD-HIT, Du Novo, Rainbow, Starcode, and UMI-Tools) produced both cluster information and consensus sequences. To ensure consistency across tools, only cluster information was extracted for subsequent analysis. Additionally, the calib_cons module was employed to generate single-strand consensus sequences (SSCSs), as it enables SSCS construction based on both cluster information and read indices.

Variant calling

Since the output files generated by each UMI clustering tool were in different file formats, they were standardized prior to consensus sequence generation. An in-house Python script was applied to convert the clustering output files into a unified CLUSTER format for downstream processing. The error-correction module Calib (Calib_cons v0.3.7) was executed on each cluster to generate duplex consensus sequences (DCSs)23. The DCS files were then aligned to the Genome Reference Consortium Human Build 37 (GRCh37) with BWA mem2 (v2.2.1). Alignment flags were then filtered using SAMtools (v1.17) to remove unmapped reads, unmapped mates, secondary alignments, and supplementary alignments, retaining only properly mapped read pairs. BWA-MEM2 (v2.2.1) was selected because variant calling results are largely independent of the specific aligner utilized during somatic variant analysis38. Ultimately, variant calling was conducted using SiNVICT (v1.0). For comparison, SiNVICT was also applied directly to the raw reads without UMI clustering or error correction to evaluate the impact of these preprocessing steps34.

Performance evaluation

The performance of each clustering tool on the simulated datasets was evaluated based on the calculation of sensitivity, precision, and F1 score, which collectively measure accuracy in low-frequency variant detection. Sensitivity, precision, and the F1 score were calculated as follows:

Here, a TP was defined as a variant existing in the ground-truth dataset and correctly identified by the analysis pipeline. An FP was referred to a variant absent from the ground-truth dataset but incorrectly identified, whereas a false negative (FN) represented a variant present in the ground-truth dataset but missed by the pipeline.

All computational experiments were performed on a dedicated high-performance server running Ubuntu 22.04, equipped with an Intel Xeon Platinum 8375 C CPU operating at a base clock of 2.90 GHz (32 physical cores), 256 GB of RAM, and 12 TB of local storage. Hyper-Threading was disabled to maintain a one-to-one mapping between physical and virtual cores, ensuring computational reproducibility.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Sequence Read Archive (SRA). The N0015 and M0253 datasets are under accession numbers SRR3493407 and SRX4395159, respectively.

References

Shendure, J. et al. DNA sequencing at 40: past, present and future. Nature 550, 345–353. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature24286 (2017).

Goodwin, S., McPherson, J. D. & McCombie, W. R. Coming of age: ten years of next-generation sequencing technologies. Nat. Rev. Genet. 17, 333–351. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg.2016.49 (2016).

Frampton, G. M. et al. Development and validation of a clinical cancer genomic profiling test based on massively parallel DNA sequencing. Nat. Biotechnol. 31, 1023–1031. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.2696 (2013).

Song, P. et al. Selective multiplexed enrichment for the detection and quantitation of low-fraction DNA variants via low-depth sequencing. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 5, 690–701. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41551-021-00713-0 (2021).

Salk, J. J., Schmitt, M. W. & Loeb, L. A. Enhancing the accuracy of next-generation sequencing for detecting rare and subclonal mutations. Nat. Rev. Genet. 19, 269–285. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg.2017.117 (2018).

Yeom, H. et al. Barcode-free next-generation sequencing error validation for ultra-rare variant detection. Nat. Commun. 10, 977. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-08941-4 (2019).

Menon, V. & Brash, D. E. Next-generation sequencing methodologies to detect low-frequency mutations: catch me if you can. Mutat. Res. Reviews Mutat. Res. 792, 108471. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mrrev.2023.108471 (2023).

Boscolo Bielo, L. et al. Variant allele frequency: a decision-making tool in precision oncology? Trends Cancer. 9, 1058–1068. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trecan.2023.08.011 (2023).

Daum, L. T. et al. Next-generation ion torrent sequencing of drug resistance mutations in Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 50, 3831–3837. https://doi.org/10.1128/jcm.01893-12 (2012).

De Vlaminck, I. et al. Circulating Cell-Free DNA is a Non-Invasive marker of heart transplant rejection. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 33, S84–S84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healun.2014.01.261 (2014).

Li, Y., Nieuwenhuis, L. M., Keating, B. J., Festen, E. A. M. & de Meijer, V. E. The impact of donor and recipient genetic variation on outcomes after solid organ transplantation: A scoping review and future perspectives. 106 1548-1557 https://doi.org/10.1097/tp.0000000000004042 (2022).

Moufarrej, M. N., Bianchi, D. W., Shaw, G. M., Stevenson, D. K. & Quake, S. R. Noninvasive prenatal testing using Circulating DNA and RNA: Advances, Challenges, and possibilities. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Data Sci. 6, 397–418. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-biodatasci-020722-094144 (2023).

Faldynová, L. et al. Non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT): combination of copy number variant and gene analyses using an in-house target enrichment next generation sequencing-Solution for non-centralized NIPT laboratory? Prenat Diagn. 43, 1320–1332. https://doi.org/10.1002/pd.6421 (2023).

Xiang, X. et al. Evaluating the performance of low-frequency variant calling tools for the detection of variants from short-read deep sequencing data. Sci. Rep. 13, 20444. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-47135-3 (2023).

Browne, T. N. & Freeman, M. Next generation sequencing: Forensic applications and policy considerations. 6, e1531, (2024). https://doi.org/10.1002/wfs2.1531

Kinde, I., Wu, J., Papadopoulos, N., Kinzler, K. W. & Vogelstein, B. Detection and quantification of rare mutations with massively parallel sequencing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 108, 9530–9535. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1105422108 (2011).

Schmitt, M. W. et al. Detection of ultra-rare mutations by next-generation sequencing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 109, 14508–14513. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1208715109 (2012).

Ahn, J. et al. Asymmetrical barcode adapter-assisted recovery of duplicate reads and error correction strategy to detect rare mutations in Circulating tumor DNA. Sci. Rep. 7, 46678. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep46678 (2017).

You, X. et al. Detection of genome-wide low-frequency mutations with Paired-End and complementary consensus sequencing (PECC-Seq) revealed end-repair-derived artifacts as residual errors. Arch. Toxicol. 94, 3475–3485. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00204-020-02832-0 (2020).

Newman, A. M. et al. Integrated digital error suppression for improved detection of Circulating tumor DNA. Nat. Biotechnol. 34, 547–555. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.3520 (2016).

Dunwell, T. L. et al. Adaptor template Oligo-Mediated sequencing (ATOM-Seq) is a new ultra-sensitive UMI-based NGS library Preparation technology for use with CfDNA and CfRNA. Sci. Rep. 11, 3138. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-82737-9 (2021).

Alcaide, M. et al. Targeted error-suppressed quantification of Circulating tumor DNA using semi-degenerate barcoded adapters and biotinylated baits. Sci. Rep. 7, 10574. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-10269-2 (2017).

Orabi, B. et al. Alignment-free clustering of UMI tagged DNA molecules. Bioinformatics 35, 1829–1836. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bty888 (2019).

Smith, T., Heger, A. & Sudbery, I. UMI-tools: modeling sequencing errors in unique molecular identifiers to improve quantification accuracy. Genome Res. 27, 491–499. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.209601.116 (2017).

Peng, X. & Dorman, K. S. Accurate Estimation of molecular counts from amplicon sequence data with unique molecular identifiers. Bioinformatics 39 https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btad002 (2023).

Liu, D. Algorithms for efficiently collapsing reads with unique molecular identifiers. PeerJ 7, e8275. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.8275 (2019).

Stoler, N., Arbeithuber, B., Guiblet, W., Makova, K. D. & Nekrutenko, A. Streamlined analysis of duplex sequencing data with du Novo. Genome Biol. 17, 180. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-016-1039-4 (2016).

Fu, L., Niu, B., Zhu, Z., Wu, S. & Li, W. CD-HIT: accelerated for clustering the next-generation sequencing data. Bioinformatics 28, 3150–3152. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bts565 (2012).

Zorita, E., Cuscó, P. & Filion, G. J. Starcode: sequence clustering based on all-pairs search. Bioinformatics 31, 1913–1919. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btv053 (2015).

Chong, Z., Ruan, J. & Wu, C. I. Rainbow: an integrated tool for efficient clustering and assembling RAD-seq reads. Bioinformatics 28, 2732–2737. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bts482 (2012).

Clement, K., Farouni, R., Bauer, D. E. & Pinello, L. AmpUMI: design and analysis of unique molecular identifiers for deep amplicon sequencing. Bioinformatics 34, i202–i210. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bty264 (2018).

Stoler, N. et al. Family reunion via error correction: an efficient analysis of duplex sequencing data. BMC Bioinform. 21, 96. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12859-020-3419-8 (2020).

Kennedy, S. R. et al. Detecting ultralow-frequency mutations by duplex sequencing. Nat. Protoc. 9, 2586–2606. https://doi.org/10.1038/nprot.2014.170 (2014).

Kockan, C. et al. SiNVICT: ultra-sensitive detection of single nucleotide variants and indels in Circulating tumour DNA. Bioinformatics 33, 26–34. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btw536 (2017).

Sater, V. et al. UMI-Gen: A UMI-based read simulator for variant calling evaluation in paired-end sequencing NGS libraries. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 18, 2270–2280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csbj.2020.08.011 (2020).

Xu, C., Nezami Ranjbar, M. R., Wu, Z., DiCarlo, J. & Wang, Y. Detecting very low allele fraction variants using targeted DNA sequencing and a novel molecular barcode-aware variant caller. BMC Genom. 18, 5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-016-3425-4 (2017).

Xu, C. et al. smCounter2: an accurate low-frequency variant caller for targeted sequencing data with unique molecular identifiers. Bioinformatics 35, 1299–1309. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bty790 (2019).

Ewing, A. D. et al. Combining tumor genome simulation with crowdsourcing to benchmark somatic single-nucleotide-variant detection. Nat. Methods. 12, 623–630. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.3407 (2015).

Funding

This study was funded by the Scientific and Technological Research Program of Chongqing Education Committee (KIQN202300627), and the Natural Science Foundation of Chongqing (CSTB2024NSCQ-KJFZMSX0036) received by Dan Pu. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or manuscript preparation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, Dan Pu and Jie Li; Data curation, Jie Li; Formal analysis, Jiagen Li; Investigation, Senbiao Qin; Methodology, Jie Li; Resources, Xinyu Qiu; Software, Jie Li and Ziqi Wang; Supervision, Dan Pu and Kunxian Shu; Validation, Jie Li and Senbiao Qin; Visualization, Kunxian Shu; Writing – review & editing, Dan Pu. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pu, D., Li, J., Li, J. et al. Benchmarking UMI clustering tools for accurate detection of low-frequency variants from deep sequencing. Sci Rep 16, 3204 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33128-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33128-x