Abstract

Agriculture is a cornerstone of the economies of many countries, and wheat is a staple cereal crop that sustains nearly half of the worldwide population. However, production of wheat is highly vulnerable to biotic stress such as pathogens and pests, as well as adverse environmental conditions. These factors significantly affect yield and quality, posing critical threats to food security and economic resilience. Conventional disease detection methods often involve intense human labor, prolonged procedures, and are predisposed to subjectivity. Therefore, the development of an automated, accurate, and real-time disease monitoring system is imperative for modern precision agriculture. We propose a hybrid deep learning based Multi-Disease Detection Framework for Wheat Diseases (MDDM-WD) for the identification of multiple wheat diseases using UAV imagery. The framework leverages the pre-trained VGG-16 convolutional neural network for deep feature extraction via a transfer learning approach. These features are subsequently classified using Support Vector Machine (SVM), Random Forest (RF), Decision Tree (DT), XGBoost, and Bernoulli Naïve Bayes (BNB) algorithms of machine learning. The model is trained and evaluated on a custom-curated dataset, containing wheat diseases: stripe rust, powdery mildew, scab (Fusarium head blight), and yellow dwarf. Evaluation of experiments demonstrates that the classification performance is enhanced significantly through our hybrid approach, with accuracy ranging from 74 to 97%, precision from 73 to 96%, and recall from 73 to 95.7%. The SVM-based variant of the model achieved the highest performance, yielding 96% precision, 95.7% recall, 96% F1-score, and 97% accuracy. The proposed two-phase fine-tuned system demonstrates its effectiveness and efficiency in detecting multiple wheat diseases. The MDDM-WD model offers a resource-efficient and scalable approach for early disease detection, supporting informed decision-making for farmers, agronomists, and policymakers in advancing sustainable agriculture.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Agriculture is a significant driver of economic growth. It plays a catalytic role in the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in developing countries. The demand for food has increased exponentially with the rapid growth of the population. The attention of researchers, agronomists, and plant geneticists has been drawn toward crop yield maximization and crop disease detection in a timely manner1.

Cereal crops such as wheat, barley, rice, maize, oats, and rye are vital sources of food worldwide. Consequently, researchers are making continuous efforts not only to increase their yield but also to improve seed quality. Efficient methods are being developed for the proactive detection and control of crop diseases. An estimated 20–40% reduction in crop yield is due to the plant pathogens and pests, as reported by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), a specialized agency of the United Nations. Therefore, the factors causing crop diseases must be addressed effectively to ensure food security and sustainable agricultural development2,3. Wheat is a vital cereal crop for food security across the world. Despite advancements in seed quality and disease management technologies, an annual loss of 15–20% in yield and grain quality is caused by wheat diseases4. Timely identification and treatment of wheat diseases is needed to reduce yield losses. Various diseases affect the wheat crop by targeting stems, leaves, roots, and spikes. Manual inspection over large fields is often time-consuming, susceptible to human error, and requires extensive human involvement5. The conventional procedure detects diseases only after significant damage. This emphasizes the importance of more efficient and continuous monitoring approaches6.

Automated detection of wheat disease using artificial intelligence (AI) is explored in many recent studies. Computer-aided decision making enables timely diagnosis with accuracy and reduces both effort and cost. Deep learning models, particularly Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), have shown significant achievement in disease detection and classification7,8,9. Additionally, supervised ML algorithms such as Naive Bayes (NB), DT, SVM, RF, and K-Nearest Neighbor (KNN) have been widely applied for classifying extracted features from wheat crop images10. A key challenge in wheat disease detection using computer vision (CV) and ML is data acquisition and dataset creation, which must include diverse disease classes, alignments, and backgrounds. Publicly available wheat disease datasets are limited, often featuring small-scale collections, such as single-leaf images with uniform backgrounds or controlled conditions, but do not cover all wheat disease classes11,12. Wheat diseases are broadly classified into several categories, namely fungal, bacterial, and insect-related diseases. Most research studies have focused on identifying and classifying wheat rust diseases, such as stripe rust, stem rust, and leaf rust, with artificial neural networks (ANNs) being the most commonly used machine learning algorithm13. Many wheat disease detection studies used private datasets, limiting reproducibility, generalizability, and real-world applicability of trained models, thus hindering research progress. Public datasets are scarce and often suffer from issues like limited disease classes, class imbalance, and controlled, non-diverse imaging conditions11.

Recent research has predominantly targeted wheat rust diseases, neglecting other equally damaging diseases that affect the yield. Therefore, it is necessary to expand the scope to include a wider range of diseases. Feature extraction and classification are performed by utilizing state-of-the-art DL or pre-trained models in many studies; however, few have explored hybrid approaches that combine DL with traditional ML14,15,16,17. Although such methods have been applied to other crops and their use in wheat disease detection remains limited, indicating a clear gap and need for further investigation.

In recent studies, deep learning (DL) approaches have shown significant success for crop disease classification across varied agricultural contexts. Kunduracıoğlu et al.64 evaluated several convolutional neural network (CNN) architectures, including ResNet50, InceptionV4, and EfficientNet, for apple leaf disease detection. Near-perfect accuracy emphasized the potential of deeper networks for fine-grained classification. Authors in study65 explored multiple pre-trained CNN and Vision Transformer models for the identification of grape leaf disease. They achieved exceptional performance across various standard datasets. Authors66 employed variants of the ResNet architecture to classify multiple types of tomato diseases with high precision. Moreover, study67 effectively used the EfficientNet model to detect sugarcane disease, achieving over 93% accuracy on multi-class datasets. All of these studies highlight the efficient performance and adaptability of DL models for plant disease detection across a variety of crops. Furthermore, it motivates the researchers to apply these to complex datasets, such as those we used in our proposed work.

Despite all the advancements, several research gaps persist in wheat disease detection. Many studies relied on private datasets, which limit the reproducibility and further development. Limitations of public datasets, such as a lack of diversity, featuring few disease classes, class imbalance, and images captured in controlled environments, reduce model generalizability. Mostly DL models are optimized end-to-end, without enhancing the feature extraction and classification phases separately. Additionally, hybrid approaches combining ML or DL models have shown promise in other crops but have rarely been applied to wheat. Existing studies focused greatly on binary classification, leaving a wide gap in multi-class classification under real-world conditions. Although transfer learning has been used to improve performance but its application in wheat disease detection is still limited.

This study aims to address existing gaps in wheat disease detection by developing a hybrid DL and ML multi-disease detection framework. We used real-time, UAV-captured, in-field imagery to detect multi-class wheat diseases. The proposed integrated model leverages a DL architecture with a transfer learning approach. we combined it with ML classification algorithm to perform multi-class classification of wheat diseases with improved accuracy and precision. The objective is to design a multi-disease framework to detect wheat diseases at their early stage. It enables farmers to make preventive decisions in order to reduce crop losses and limit the spread of diseases. Key research challenges for the proposed research study include:

-

Curation of a multi-class wheat disease dataset consisting of real-field, multi-leaf images featuring complex backgrounds to improve model generalization.

-

Inclusion of balanced image samples of multiple wheat diseases to ensure broader disease coverage.

-

To develop a hybrid model integrating a pre-trained DL backbone for feature extraction with advanced ML classifiers for disease identification.

-

Applying optimization techniques to improve model accuracy and operational efficiency for practical field deployment.

We contributed by designing a hybrid wheat multi-disease detection model that combines multiple machine learning classifiers with a transfer learning-based pre-trained VGG-16 architecture for feature extraction. We improved early detection accuracy and model efficiency under real-field conditions by utilizing two real-field UAV image datasets and addressing a broader spectrum of wheat diseases.

The remaining structure of this study is as follows: Sect. 2 elaborates on the existing literature related to crop disease detection briefly, Sect. 3 refers to the materials and methodology used in the proposed study, Sect. 4 describes the experimental results, whereas subsequent sections present the thorough discussion of the study, limitations, and the recommended future enhancements of our proposed approach. The last section provides the conclusion of the study.

Related literature

The existing research literature is comprehensively reviewed in this section to identify gaps, prevailing trends, and emerging themes that form the foundation of the present study.

Disease detection using image processing

Continuous efforts are being made by using image processing (IP) to detect diseases that can cause serious damage to the quality and yield of crops. CV tools keep standard IP principles unchanged and improve the accuracy. Information embedded in images is extracted using IP for further manipulation and calculations. Authors in18 performed crop leaves disease detection by utilizing Artificial neural network (ANN), Naïve Bayes (NB), fuzzy logic analysis, classification using orthogonal locally discriminant projection algorithm (OPDPA), minimum path evaluation theory, fractal dimensions, SVM, AdaBoost algorithm, and rule set theory. Authors in19 used segmented images as input to the CNN and performed image segmentation using an HIS and LAB color space-based hybrid algorithm to detect crop diseases. Another approach was presented20 to use IP procedures such as Gray Level Co-occurrence Matrix (GLCM), Local Binary Pattern (LBP), and SVM to detect plant diseases at early stages by using mobile captured images. Sethy et al.21 presented an image segmentation approach to identify rice crop disease using K-means clustering ML techniques by using spatial and color features of the input images. Tian et al.22 presented a study to use feature patterns of tomato leaves, such as S, I from HSI color space, and the a∗, b∗ components from L*a*b* color space, utilizing the K-means clustering algorithm for image segmentation. Researchers in study23 presented an approach by combining canny edge detection, k-means clustering, and k-nearest neighbor to segment corn, potato, and tomato images. Later, GLCM and SVM were used to extract features and classify diseases. Although image processing methods have shown potential for disease detection, but depend on handcrafted features and struggle under varying field conditions. Our study bridges that gap by integrating image processing with deep learning based feature extraction to achieve more reliable crop disease classification.

Machine learning approaches for image classification

Several studies have addressed the various concerns regarding plant disease detection, such as variability of color and texture features, diversity of disease classes, availability of training and test datasets, and use of an appropriate algorithm. Harakannanavar et al.24 proposed a high-precision method for detecting tomato leaf diseases by integrating machine learning with techniques such as image enhancement, segmentation, feature extraction using PCA, DWT, and GLCM of image processing, followed by classification with SVM, CNN, and KNN. Another study was proposed by Nikith et al.25 by performing a comparative analysis of eight different types of soybean leaves, where they used Manhattan distance and Euclidean distance to extract HOG features while using the KNN algorithm. An approach was presented by Javidan et al.27 to classify grape leaves diseases by using gray-level threshold pixel clustering and Canny edge detection for background removal, features such as GLCM, LBP, HOG, Harris corner detection, BRISK, oriented fast and rotated BRIEF (ORB), maximally stable external regions (MSER) were extracted in RGB, HSV and l*a*b color space models by using Otsu algorithm and K-means method. Authors in26 developed a novel tool based on remote sensing and an artificial neural network (ANN) modeling framework configured as a binary classifier for spatial quantification of Potato Virus Y (PVY) using insecticides, and visual assessment of the infectious status of plants. Authors proposed a study27 by implementing ML algorithms such as the Bayes algorithm, SVM, and ANN to differentiate the diseases into binary classification using mobile captured images of a multicropping field. Panigrahi et al.28 used supervised machine learning classifiers, namely Naive Bayes (NB), Decision Tree (DT), K-Nearest Neighbor (KNN), Support Vector Machine (SVM), and Random Forest (RF) to identify maize plant disease. Authors presented a study29 to detect rice crop disease by using ML algorithms such as KNN, Decision Tree, and Naive Bayes using images with a plain uniform background. Authors30 employed Extreme Learning Machine (ELM) with the simplest form of feed-forward neural network that consists of numerous hidden nodes to classify tomato plant diseases. Existing studies indicate that the reliance of ML algorithms on manually extracted features limits their adaptability to complex field conditions. This study addresses this limitation by employing deep feature representations from a fine-tuned VGG16 model integrated with ML classifiers to enhance classification accuracy.

Deep learning for crop disease detection

Advancement in deep learning CNNs enhances the computation and precision in smart agriculture. Authors in31 proposed DenseNet121 to recognize the wheat crop diseases based on the skip connection concept of the ResNet model after making a performance comparison of several DL models on the three different public datasets of wheat crop, named as, Wheat Common Disease Dataset (WDD), the Common Plant Disease Dataset (PDD), and the Wheat Rusts Dataset (WRD). Dey et al.32 used both variants of pre-trained VGG model and AlexNet DL models on the Plant Village dataset to detect diseases with accuracy. Singh et al.33 suggested an approach to identify wheat stripe rust disease from satellite Sentinel-2 images using a deep learning artificial neural network. Authors in34 proposed an approach comprised of EfficientNetV2-B4 with additional dense layers to tackle the challenges of crop variety and complexity of crop disease classification due to the difference in real-time image parameters. Researchers in35 performed early detection of Apple diseases by using a DL-based YOLOV4 algorithm and considered critical factors such as fine-grained multi-scale dissemination, resemblance of color and texture features among diseases, complexity of background, and changes in environmental conditions, etc. Picon et al.36 proposed a study by implementing an adapted Deep Residual Neural Network-based algorithm to detect several plant diseases from mobile captured images in a real-time environment. Despite their accuracy, DL models often fail to generalize under real-world variations. This study fine-tunes VGG-16 to extract domain-specific features and combines them with ML classifiers to enhance robustness and scalability in crop disease detection.

Transfer learning approach for crop disease detection

Many studies have employed transfer learning approach in order to handle the need for large datasets and powerful resources required by DL models. Nigam et al.39 used the Mobile Inverted Bottleneck Convolution (MBConv) architecture as a base model, which worked like EfficientNet architecture variants B0 to B7, to detect three types of wheatRust21 disease. Tang et al.40 proposed an approach by using a pre-trained ResNet-18 architecture to detect wheat stripe rust disease using images captured in diverse fields and weather conditions using smartphones and UAVs. Chen et al.41 presented an enhanced model, INC-VGGN, by replacing the full connection layer of the conventional VGG model with a global pooling layer and two Inception modules, resulting in enhanced performance and feature extraction capacity. Authors in42 used DL pre-trained models such as VGG-16, VGG-19, GoogLeNet, ResNet101, and DenseNet201, for the multiclass disease classification of four different crops by using a transfer learning approach. VGG model variant 16 produced the highest test accuracy among all, according to this study. Although transfer learning has advanced crop disease detection, challenges such as limited crop diversity, feature extraction efficiency, and real-world generalizability still remain. The present study addresses these gaps by curating a dataset of diverse diseases with complex field conditions, leveraging a transfer learning approach to detect diseases with high accuracy and precision.

Hybrid models for crop disease classification

Crop disease detection commonly relies on traditional ML, deep learning, image processing, and transfer learning methods. However, limited research has explored hybrid models that combine DL and ML approaches. Xu et al.43 introduced a hybrid deep learning model, RFE-CNN, combining residual channel attention block (RCAB), feedback block (FB), elliptic metric learning (EML), and CNN to improve the identification of wheat leaf disease. Their approach prioritized accuracy and outperformed existing deep learning methods. An approach to detect and evaluate corn disease severity stage under complicated field parameters was presented by Divyanth et al.44. Three different semantic segmentation models, such as U-Net, DeepLabV3, and SegNet, were deployed for leaf extraction. The study concluded that the integrated UNet and DeepLabV3 + outperformed the others on the basis of performance to detect and estimate the diseases and their severity. Nandhini et al.45 presented a model named Gated-Recurrent Convolutional Neural Network (G-RecConNN) by combining both the CNN and RNN to detect diseases of plantain trees at their early stages. Image features were encoded on the arrival of a new image by using an RNN, but the computational expense of the model increased linearly with the increase in dataset size. Lin et al.46 proposed a study to cope with challenges such as irregular illumination, noise, dew drops on crop leaves, and the quality of the apparatus. They presented a robust algorithm matrix-based convolutional neural network (M-bCNN), that discriminated the domain-specific information and differentiated between categories accurately. Researchers in47 presented an integrated DL Framework (IDLF) using pre-trained EfficientNetB2, MobileNet, Xception, NASNetMobile, InceptionV3, DenseNet121, DenseNet169, DenseNet201, RegNetY080, ResNet50V2, ResNet101V2, ResNetRS50, and ResNetRS101, and Ensemble Learning (EL), which perform multi-class classification of wheat disease, whereas model performance was evaluated by using SVM, Decision tree, and Random Forest. The RegNetY080 with random forest outperformed others. Researchers in48 applied U² Net for segmentation of wheat stripe rust and compared it to other segmentation methods such as GrabCut and Watershed. U² Net significantly improved classification accuracy, reaching up to 96.19%, while other segmentation methods yielded lower accuracy, i.e., 75–88%. Researchers in49 proposed an approach by using fast Fourier convolution blocks and capsule feature encoding to distinguish wheat yellow rust from nitrogen deficiency via Sentinel‑2 time-series data. It achieves 91–92% overall accuracy under natural field conditions, offering strong generalization and computational efficiency compared to baseline CNN models. Authors in50 proposed a hybrid model (CNN‑CGLCM_HSV + SVM) by combining textural descriptors such as gray-level and color-level features with deep features extracted from a pre-trained DenseNet model on the Yellow-Rust‑19 dataset, outperforming models using only texture or deep features alone. Existing studies are limited to specific crops, lack generalization under diverse field conditions, and few focus on multi-disease detection due to high computational complexity. The present study addresses these gaps using a hybrid fine-tuned DL framework for multi-disease detection from complex multi-leaf imagery of wheat crop in real-field conditions.

UAV-Based deep learning for crop disease monitoring

Recent studies highlighted the growing role of UAVs and deep learning technologies in smart agriculture. Patel et al.51 developed a deep learning based computer vision framework to automate basil crop identification with high precision. Chouhan et al.52 highlighted the need for drones in next-generation agriculture for real-time data acquisition, crop observation, and precise resource management. Jamgaonkar et al.53 reported YOLOv5 as the most efficient YOLO architecture for real-time object detection using UAV-based agricultural imaging. Chouhan et al.54 thoroughly analyzed the integration of drones into agricultural systems, addressing the related technological challenges, implementation tactics, and precision-driven farming solutions to boost the economy. Another Study69 achieved 96.5% accuracy by using multimodal data fusion of environmental sensors and UAV imagery to detect wheat leaf disease. Lin et al.70 demonstrated an attention-enhanced UAV imagery analysis framework for rice disease detection with 81.4% accuracy in complex field conditions. Existing UAV-based studies focus on specific crops and generic detection, overlooking multi-disease classification under complex field conditions. This study addresses these gaps using a fine-tuned DL framework for multi-disease wheat detection from UAV imagery. Table 1 shows the comparison of techniques used in recent studies for the detection of wheat diseases.

Proposed methodology

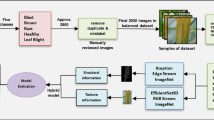

Our proposed MDDM-WD hybrid model detects and identifies wheat multi-diseases using in-field, multi-leaf, real-time, UAV imagery with having diverse background. Our model contains several phases to perform the designated task of wheat multi-disease detection with precision and accuracy. Figure 1 shows the interaction between different phases of our proposed MDDM-WD using a conceptual diagram. This section provides a detailed elaboration of all the phases of our MDDM-WD model.

Experimental setup

All experiments and model training procedures were carried out using Google Colaboratory, a cloud-based platform that provides access to high-performance computing resources. The configuration of the runtime environment is Python 3 and NVIDIA Tesla T4 GPU with dedicated VRAM of 15 GB. The T4 GPU is optimized for deep learning workloads. It supports CUDA-enabled acceleration to facilitate efficient training and inference using TensorFlow and PyTorch libraries. Initial development of the model was performed on a local workstation having Windows 10 Pro, an Intel Core i7-6600U CPU operating at 2.60 GHz (up to 2.81 GHz), and 12.7 GB of RAM. However, all computationally intensive tasks were executed within the cloud-based environment to leverage the benefits of GPU acceleration.

Data fusion

Wheat diseases appear only for a short period during the crop’s growth cycle, which poses challenges for extensive data collection. This limited time frame, combined with weather-related constraints, further restricts opportunities for gathering data. As a result, the amount of publicly available usable data of wheat diseases for analysis is significantly reduced5,52. Most of the existing studies used custom datasets comprised of single-leaf, uniform background image datasets for wheat disease detection using state-of-the-art CNN36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54.

Dataset acquisition

We focused on training and testing our proposed MDDM-WD using wheat crop multi-leaf images of multiple diseased classes captured in a real-time environment with different illumination conditions, complex background details to establish a crop disease identification framework with more precision and efficient performance. We targeted two publicly available crop disease datasets, dataset-1 (Multi-Scene Wheat Disease Dataset (MSWDD2022))55 and dataset-2 (20k + Multi-Class Crop Disease Images dataset)56, based on the diverse nature of images and complex background conditions, to curate a dataset for our proposed hybrid model with multiple disease classes of wheat crop.

Dataset-I description

The MSWDD2022 dataset, utilized in study57, was compiled over two years (2021–2022) from three experimental sites located in Xianyang City, Shaanxi Province, China. The dataset includes images of wheat diseases from over 200 wheat varieties, each exhibiting different levels of disease susceptibility. Images were captured at different times of day (9:00 AM, 1:00 PM, and 5:30 PM) under varying lighting and weather conditions to ensure data diversity. Smartphones and digital cameras were utilized for data collection, while automated focusing and balancing were applied. The dataset of 2,236 complex and real-time images in PNG format, reflecting in-field conditions, was formed. Table 2 shows the composition of the MSWDD2022 dataset al.ong with the number of images in each class of wheat disease.

Dataset-II description

The 20k + Multi-Class Crop Disease Images dataset56 is a collection of various disease images of five major crops: wheat, maize, cotton, sugarcane, and rice. The dataset includes a variety of high-quality images collected from public repositories, web scraping, and manual in the field. It covers images of diseases at different development phases, providing valuable information about crop health. This dataset is publicly available on the Kaggle repository under an open license. This dataset is used for disease detection, precision agriculture, and academic research. We specifically focus on fungal diseases affecting wheat crops in this study. Table 3 describes the details of selected disease classes and the number of images per disease class of the wheat crop available in this dataset.

Wheat multi-disease dataset (WMDD) Preparation

After selecting the relevant disease types and classes of wheat crop, the integration of both the source datasets, i.e., MSWDD2022 and 20k + Multi-Class Crop Disease Images, was carried out. The MSWDD2022 dataset contains images in PNG format, whereas the 20k + Multi-Class Crop Disease Images dataset consists of images in JPEG format. Before proceeding to the preprocessing phase of our proposed MDDM-WD architecture, all images were converted to a uniform PNG format to ensure the consistency of the model. Following the format conversion, both of the source datasets were merged to create a single, unified dataset. The sequence of steps to perform the format conversion and integration of Dataset-I and Dataset-II is shown in Algorithm 1.

Algorithm 1: Steps to prepare the wheat multi-disease dataset (WMDD) for our Multi-Disease Detection Model.

After integration of both of our source datasets, resultant dataset was comprised of 3458 images of 8 disease classes of wheat crop where 753 images of powdery mildew, 641 images of wheat scab, 599 images of yellow dwarf, 680 images of stripe rust, 177 images of leaf blight, 183 images of black rust, 104 images of brown leaf rust and 321 images of healthy class. The obtained dataset contained unbalanced diseased classes. Therefore, based on the balanced class weights, uniqueness, and existing research studies, we selected wheat powdery mildew, wheat scab, wheat yellow dwarf, and wheat stripe rust from the resultant dataset. The distribution of images per disease class of wheat crop in our wheat multi-disease dataset (WMDD) is shown in Table 4.

Image processing

Image processing plays a critical role in crop disease detection and significantly influences the accuracy of classification results. In this study, various image processing techniques were applied to analyze and detect multiple classes of diseases affecting the wheat crop. Image preprocessing is a vital step that prepares raw images for training and inference using convolutional neural networks (CNNs). We applied some key operations of image preprocessing, such as resizing, normalization, rescaling, contrast adjustment, grayscale conversion, and noise filtering, to ensure consistency in image format, size, orientation, and quality.

Image preprocessing

As we used two different datasets, images have different resolutions, illumination or lighting effects are different, shape and size of images may also be different. All the images are in 256 × 256 dimensions and three channels, i.e., red, green, and blue. We resize images into 224 × 224 dimensions by using the cv2. resize () function to make it suitable for a deep learning model. Deep learning models cannot process raw images directly because of the noisy and ambiguous information encapsulated in them. Therefore, raw images are prepared by performing additional preprocessing operations to be used by the DL model effectively. We convert images into an n-dimensional NumPy array. Rescale the images by dividing all the pixel values by 255 to have a normalized image with pixel values ranging from 0 to 1 to standardize the dataset for efficient feature extraction and model training. RGB images are converted into BGR by using the cv2.cvtColor() function.

One hot label encoding

One hot label encoding technique was applied to support multi-class classification of our WMDD images. Label encoding is done by using a one-hot encoder to convert the string labels of disease classes to integers to perform multi-classification. We used LabelEncoder() functions to encode text labels to integers. Then, one hot label encoder encoded y values for the neural network by using the to_categorical() function in Keras.

Image enhancement for improved feature extraction

Images were further refined by enhancing color, edges, and contrast through the Contrast Limited Adaptive Histogram Equalization (CLAHE) technique and Adaptive Thresholding. CLAHE was applied to improve local contrast and highlight disease-affected regions by generating multiple histograms for each image, efficiently handling both RGB (3-channel) and grayscale (1-channel) formats. Initially, all BGR images were converted into grayscale before applying CLAHE to enhance image precision and feature visibility. Figure 2 illustrates how CLAHE improves the visual quality of wheat disease images by enhancing local contrast and revealing finer lesion details. Subsequently, Adaptive Thresholding was used to segment diseased areas by separating the foreground (infected regions) from the background, thus improving boundary sharpness and lesion detection. The visual outcomes of the applied image enhancement techniques are illustrated in Figure 3, where both CLAHE and adaptive thresholding significantly improve the visibility of disease-affected regions compared to the original image.

Dataset splitting and augmentation

Our multi-disease dataset, WMDD, contained images of all diseases in labeled folders collectively. But for feature extraction, the DL model requires two separate datasets of the same disease classes, i.e. train dataset is required for model training, and a test dataset is required for model testing and validation. Therefore, we performed splitting of the dataset in 80:20 ratios to divide of dataset into a train set and test set by using the split-folders function in Python.

DL models produce better results with large datasets and decrease the generalization errors58,59. We performed augmentation on the training dataset to increase the sample size for model training to improve the performance of used DL hybrid model used. We employed image rotation, horizontal flip, and shear range image augmentation techniques to increase the size of the training set and prevent overfitting of our model. We further divided the train dataset into two sets, i.e. train set and the validation set, to perform self-testing of the model before testing it on the test dataset. The validation set was used by the DL model internally while working in training mode, so this cross-validated the performance of our model.

Features extraction using transfer learning

The adoption of deep learning for plant disease detection has shown remarkable success in recent years. A recent systematic review summarized 160 studies applying CNN and transfer learning-based approaches, confirming their superior accuracy and scalability compared to traditional machine learning models63. Therefore, after image preprocessing, enhancement, and augmentation, we chose a deep learning based pre-trained model for feature extraction of images from our WMDD dataset. Deep learning CNN models use differently sized filters to extract features for recognizing or classifying images. Whenever we train these models on a dataset, they apply filters to extract details of image features internally, which requires time and resources. Therefore, instead of training a DL CNN model from scratch, we chose a transfer learning approach for feature extraction of wheat disease images with better accuracy and efficiency. State-of-the-art DL models are pre-trained on a large dataset of images named ImageNet: A Large-Scale Hierarchical Image Database of 1000 classes of image61 or MS COCO dataset62. These pre-trained models use knowledge of the base model of a large image dataset and apply pre-trained weights on the new dataset of images to extract features without training the model again. This has not only saved time and resources but also performed image recognition with better accuracy. Figure 4 shows the transfer learning approach for the extraction of features from the wheat disease dataset.

Used model

DL models, particularly CNNs, require substantial computational resources and training time to learn high-level image representations effectively. Moreover, their performance is highly influenced by the size and diversity of the dataset on which they were trained to extract features.

Features extraction using Pre-Trained VGG-16 model

To overcome these limitations, we employed the pre-trained deep learning model VGG-16, which was trained on the ImageNet dataset, a large-scale hierarchical image database comprising over one million high-resolution images spanning 1,000 classes. Leveraging the learned weights of VGG-16 allowed for efficient and robust feature extraction, as the VGG-16 model is already capable of capturing generic image features such as edges, textures, shapes, and object structures through its convolutional layers.

VGG-16 is a deep CNN; due to its stacked architecture of layers, it is a simple and easy-to-implement DL model with efficient image recognition abilities. Basically, it has 5 blocks of convolutional layers with the smallest possible size of filters, i.e., 3 × 3. Overall, 16 stacked layers are involved in the VGG-16 architecture. The distribution of layers is:

-

1 st block has two convolution layers, block 2 has two convolution layers, and blocks 3, 4, and 5 have 3 convolutional layers each. So collectively, it has 13 convolutional layers.

-

It has 3 fully connected layers, forming its dense or top layers, and all of them have 3 × 3 filters. These smallest-sized filters target every single pixel of images to capture the notion of their adjacent right, left, top, and bottom areas.

-

Every convolutional block is followed by max pooling layers with a 2 × 2 window of filter.

-

The final layer of the VGG-16 architecture is a Softmax layer. So, collectively, 21 layers of VGG architecture have 16 learnable or trainable weighted layers. The top layers of this stacked architecture of layers, i.e., 3 fully connected layers and a Softmax layer, are also known as a block of hidden layers.

Classification or identification of an image in a particular class/category is performed by hidden layers of the model. We selected the VGG-16 model for feature extraction because of its stacked hierarchical deep architecture that makes it efficient and useful for image feature extraction and identification. This architecture, by default, uses 224 × 224 dimensions of images with 3 channels of colors, i.e., red, green, and blue; that’s why we resized our WMDD images to 224 × 224 × 3.

Mathematical formulation for VGG-16 feature extraction is as follows:

Let the input image be \(\:X\:\in\:{R}^{H\times\:W\times\:C}\) where H, W, and C are the height, width, and number of channels, i.e., 3. Convolution operation for the lth layer is defined as:

Where; \(\:{F}_{i,j,k}^{l}\) is the output feature map at position (,) in channel, \(\:{W}^{l}\)is the convolutional filter weights of \(\:k\times\:k\), \(\:{b}_{k}^{l}\:\) is the bias term, \(\:\sigma\:\) is the ReLU activation function, \(\:{C}_{l-1}\)is the input channel to the layer \(\:l\). In our case \(\:\sigma\:=\text{max}\left(0,z\right).\).

Max pooling operation with window size R; we used size(\(\:2\times\:2,\:\:stride=2)\):

The flattened output from the last convolutional/pooling layer is used as a feature vector for disease classification.

During transfer learning initialization and fine-tuning, let \(\:{\theta\:}_{pre}\)be VGG-16 pre-trained weights, we initialize the feature extractor as \(\:{\theta\:}_{init}={\theta\:}_{pre}\) by defining parameter subsets as \(\:{\theta\:}_{frozen}\:\)parameters kept fixed during fine-tuning and \(\:{\theta\:}_{tuned}\) parameters updated during fine-tuning.

We leveraged the pre-trained weights of the VGG-16 model to extract the features from our wheat disease dataset (WMDD). Specifically, the convolutional base of VGG-16 was retained for feature extraction, whereas the top fully connected dense layers, responsible for classification in the original model, were removed. These dense layers were set as non-trainable to preserve the pre-learned weights during training on the WMDD dataset. This ensured that our pre-trained VGG-16 model utilized its learned filters to extract low to mid-level visual features such as edges, textures, and shapes, which were transferred across visual domains. The top hidden layers of VGG-16 are frozen to exempt the task of image classification and use all its layers of the convolutional block for the feature extraction of our own WMDD images, and that too by using a transfer learning approach.

In the fine-tuned VGG-16 model, the initial convolutional layers up to block 4 were frozen to retain the pre-trained weights, thereby preserving the general low-level features. The block 5 of final convolutional layers, along with fully connected layers, were retrained on our WMDD dataset using the Adam optimizer (learning rate = 1e-4) to adapt the model to domain-specific high-level features for crop disease classification. Table 5 shows the architecture of the proposed model after training on our WMDD. Our model had 14,714,688 total parameters, which remained unchanged even after training on WMDD, as it showed zero trainable parameters, due to the use of a transfer learning approach.

Image dimensionality reduction

Image dimensionality plays a critical role in the performance of machine learning models, as it directly impacts computational efficiency, memory usage, and model scalability. Large datasets with high-dimensional images increase the computational cost, risk of overfitting, and memory overload. Image dimensionality reduction techniques are used to address such challenges. These techniques retain the most informative features and eliminate redundant or non-contributory data. The dimensionality of images is reduced with the help of the Principal Component Analysis (PCA) technique. It transformed the original high-dimensional feature space into a low-dimensional subspace. This process reduces noise and redundancy in the data. While it preserves the most significant variance, which is essential for effective classification.

In our study, the dimensionality of deep features extracted from the fine-tuned VGG-16 model was reduced using PCA. It enhanced the computational efficiency and minimized the risk of overfitting by retaining the most discriminative features. The original feature matrix of shape (536, 100,352) was reduced to (536, 100) using n_components = 100. This reduction retained over 90% of the total variance while significantly improving training efficiency and mitigating overfitting. The chosen number of components was empirically determined through experimentation to achieve an optimal trade-off between computational efficiency and classification performance across the employed ML classifiers.

Image classification and disease identification phase

Features of four different disease classes of wheat crop, such as wheat powdery mildew, wheat fusarium head blight (wheat scab), wheat yellow dwarf, and wheat stripe rust, were extracted by using the base model of our MDDM-WD, i.e., pre-trained VGG-16 model. Image classification and identification of a particular disease class are performed on the basis of the extracted features. We integrated state-of-the-art machine learning classifiers with our base VGG-16 model to identify the disease class of an image.

For this purpose, Output in the form of extracted features with reduced dimensionality, generated by the pre-trained VG-16 model using a transfer learning approach, is acquired by the ML classifiers to detect the disease class of a given image. Figure 5 shows the working model of our proposed MDDM-WD upon integration of the DL model and ML algorithms for wheat multi-disease detection.

Random forest (RF)

We used RF to perform classification of wheat disease images into disease classes due to its ability to handle large and complex datasets. Moreover, it can also deal with the overfitting problem and locate significant features efficiently. Prediction of wheat disease classes by using random forest is computed as.

Where Ŷ represents the final prediction of the disease class of the image, T represents the total number of decision trees based on the features of the image, \(\:{\text{f}}_{\text{t}}\left(x\right)\:\)represents the prediction of the disease class made by the \(\:{t}^{th}\) tree on the input image x.

Support Vector Machine (SVM)

We selected SVM to classify wheat images into disease classes because of its computational capabilities to separate image classes after learning an optimal hyperplane in and high-dimensional space. It performed multi-class classification of wheat images using a one vs. rest strategy. It performs classification as:

Where; \(\:{\alpha\:}_{i}\) represents the Lagrange multiplier that enforces class-separation constraints during the training of the image dataset, \(\:{\beta\:}_{i}\) represents disease class labels, K represents the kernel function, b represents bias, and x is the support vector.

SVM aims to find a hyperplane that maximizes the margin while satisfying:

The optimization problem (hard margin):

For non-linear separable cases, the soft margin formula is as follows:

Where C is the penalty variable and \(\:{\epsilon\:}_{i}\:\)are slack variables.

Decision tree (DT)

It was selected to integrate for wheat disease classification because of its simplicity, ease of visualization, and minimal requirement for data preprocessing. It used generic features of images, such as color, shape, and texture, for decision making regarding disease class, and was computed as:

Bernoulli Naïve Bayes (BNB)

The classifier estimates the probability of an image belonging to each class based on the assumption that features are conditionally independent given the class label. The model assigns a class label based on the highest posterior probability, which is computed by using Bayes’ Theorem. Efficient classification in real-time or embedded image recognition systems is performed with high speed and computational simplicity. It is computed as:

Where; \(\:\widehat{y}\) is the final predicted wheat disease class of the image, x denotes the feature vector of the wheat disease images, \(\:P\left(y\right)\) represents the probability of wheat disease class labels, \(\:y=k\) represents the labels of classes.

eXtreme gradient boost (XGBoost)

We selected XGBoost for integration with our base VGG-16 model due to the fact that it works extremely well with reduced features of images using PCA. It rectifies the errors of weak classifiers by using an ensemble learning approach. We employed it as an accurate and efficient classifier with pre-trained VGG-16 over high-level extracted features. It performed classification as:

Where;\({\hat y}\) represents the final prediction of the disease class of the image, \(\:{\text{f}}_{\text{k}}\) denotes the regression tree of a weak learner, such as a decision tree of feature nodes and class labels, F represents the set of all possible wheat disease class feature node trees, and K represents the total count of trees.

Fine-Tuning of hyperparameters

The performance of the proposed MDDM-WD model is highly sensitive to the selection of hyperparameters such as batch size, number of epochs, and learning rate. To ensure optimal model performance, it is essential to identify an effective combination of these parameters. As there is no universally optimal configuration, we systematically monitored the training dynamics, such as accuracy and loss metrics, throughout the training process. Furthermore, a comprehensive grid search was employed to explore a range of hyperparameter values and identify the most suitable configuration for each machine learning algorithm individually.

We performed two-way tuning of the hyperparameters of our proposed MDDM-WD in order to identify the disease class with high accuracy and precision. The integration of DL pre-trained VGG-16 for feature extraction and ML classifiers for classification enabled us to execute tuning of the model in both phases, i.e., feature extraction and disease classification, simultaneously to get optimized output. Algorithm 2 elaborates the sequence of steps of our proposed MDDM-WD model for wheat disease detection.

Algorithm 2: MDDM-WD Real-Time Wheat Crop Multi-Disease Detection Framework.

Model evaluation

A series of experiments was conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of our proposed deep learning-based multi-disease detection model for wheat (MDDM-WD). Multiple statistical metrics were used to assess the performance of our model with the help of the generated results. The hybrid architecture of the MDDM-WD model consists of two major stages: a feature extraction phase and a classification phase. Both of these phases operate sequentially. The efficiency and accuracy of our model are dependent on the successful integration and execution of these two phases. Consequently, the overall performance of the MDDM-WD model is reliant on the accuracy and efficiency of both the feature extraction and classification phases. Therefore, we evaluated the performance of MDDM-WD by:

-

Testing base model performance, which is responsible for feature extraction.

-

Evaluating the performance of ML classifiers for accurate classification of wheat disease images into the correct class.

The performance evaluation of the proposed MDDM-WD model was conducted using standard statistical metrics, including precision, recall, and F1-score. Additionally, the overall correctness of the predicted results of the model was quantified by using an accuracy metric.

Precision

Precision refers to the quality of the final results of predicted disease classes generated by MDDM-WD and is calculated to analyze the performance of our proposed model on the basis of the correct results generated out of the total outputs. The precision of our model is computed as:

Where;

\(\:{TP}_{DiseaseClass}:\) represent the total number of correctly identified disease classes.

\(\:{FP}_{DiseaseClass}:\) represent the total number of incorrectly identified disease classes.

Precision was computed for each class based on the outputs of all machine learning classifiers. It evaluates their accuracy in terms of correctly predicting positive instances. Furthermore, the overall precision for each classification algorithm was also calculated. It assesses the general capability of minimizing false positives across all classes.

Recall

Recall measures the ability of our MDDM-WD model to identify all relevant images of disease classes. The proportion of correctly identified diseased images relative to the total number of actual diseased images is measured. Thus, it evaluates the effectiveness of our model in retrieving all positive cases. Recall is computed as follows:

Where;

\(\:{TP}_{DiseaseClass}:\) represent the total number of correctly identified disease classes.

\(\:{FN}_{DiseaseClass}:\) represent the wrong classification of disease classes.

The results produced by each machine learning classifier were used to compute class-wise recall. It evaluates the performance of all variants of MDDM-WD across individual wheat disease categories. Furthermore, the overall recall was also calculated for each ML classifier when integrated with the base model. It comprehensively evaluates their ability to correctly identify positive instances across all classes.

F1-Measure

Precision and recall often exhibit an inverse relationship. The improvement in one may lead to a reduction in the other. We employed the F1-measure as the harmonic mean of precision and recall to provide a balanced evaluation. It highlighted the significantly lower scenarios of either metric by assigning more weightage to lower values. F1-measure is calculated by using the following formulae:

Accuracy

Accuracy is one of the most commonly used performance metrics in classification tasks. It indicates the fraction of correctly predicted instances to the total number of instances. Therefore, we measured the overall predictive capability of our model by computing accuracy for each ML classifier. Performance estimation for each wheat disease class is assessed by measuring class-wise accuracy. Accuracy is computed using the following formulae:

Where;

\(\:{TP}_{DiseaseClass}:\) represent the total number of correctly identified disease classes.

\(\:{TN}_{DiseaseClass}:\) represent correctly identified images without disease.

\(\:{FP}_{DiseaseClass}:\) represent the total number of incorrectly identified disease classes other than the actual class.

\(\:{FN}_{DiseaseClass}:\) represent the wrong classification of healthy images into the disease class.

Experimental results

The effectiveness of the proposed MDDM-WD model for wheat disease detection using real-time UAV imagery was evaluated by conducting a series of experiments. Classification accuracy, model robustness, and real-time applicability in field conditions were focused on. Our model was implemented using ML and DL libraries to perform specific functionalities essential for the pipeline.

The implementation used TensorFlow and Keras to develop the DL architecture. It allowed efficient GPU-accelerated computations in the cloud-based environment. NumPy was used to manage array-based operations and numerical computations. Whereas the OS library facilitated system-level file handling. Classical ML models and evaluation metrics were implemented using Scikit-learn to aid in performance benchmarking. Image preprocessing and augmentation were done using OpenCV. Analysis of training performance was made by using visualization tools such as Seaborn and Matplotlib. These tools have created curves, confusion matrices, and performance plots.

Wheat multi-disease dataset (WMDD)

Two publicly available datasets: D1: Multi-Scene Wheat Disease Dataset (MSWDD2022)55 and D2: 20k + Multi-Class Crop Disease Images56, were used to perform experiments. The datasets comprise real-time, in-field images with complex and varying background conditions. The complexity of images provided a realistic benchmark for disease classification tasks. D1 comprised 2,236 images of four disease classes of wheat: Powdery Mildew, Wheat Scab, Yellow Dwarf, and Stripe Rust, whereas D2 included over 20,000 crop disease images of five major crops (wheat, cotton, maize, rice, and sugarcane). A subset of 1,296 images representing seven fungal wheat disease classes was extracted from D2. We further shortlisted only four disease classes, overlapping with D1 were selected for the study to maintain dataset balance and consistency. Detail of the WMDD dataset used in this study is shown in Table 6 and are visualized in Fig. 6 to understand the balance of the dataset across classes.

After dataset preparation and preprocessing, the combined WMDD dataset was partitioned using an 80:20 train-test split. Pre-trained VGG-16 as a base model was employed in the DL phase for feature extraction using a transfer learning approach. The extracted high-level image features were put into five ML classifiers in the next classification phase for final prediction.

Performance optimization using hyperparameter tuning

Optimal performance of each variant of our model was obtained by tuning the hyperparameter extensively. Key parameters such as batch size, optimizer, learning rate, number of epochs, and loss function were fine-tuned to obtain an optimal VGG-16 for the feature extractor. Grid Search and Random Search techniques were used to explore optimal hyperparameters of each ML classifier. 5-fold cross-validation was performed. The final selection of hyperparameters was made on the basis of the classification performance obtained during training. Optimal hyperparameters used for the feature extraction and classification phases of our MDDM-WD model are summarized in Table 7.

Performance evaluation of Fine-Tuned VGG-16 with integrated ML classifiers

Performance of integrated random forest

The performance of the proposed MDDM-WD using an RF classifier (MDDM-RF) is presented in Fig. 7. MDDM-RF employed VGG-16 for feature extraction and a Random Forest (RF) classifier for final prediction of disease class. The confusion matrix in Fig. 7(a) illustrates the model’s ability to differentiate between various wheat disease classes. The diagonal elements indicate correct classifications, and the off-diagonal elements represent misclassifications. 146 out of 151 images of wheat powdery mildew were correctly classified. The model correctly identified 122 out of 129 images of wheat yellow dwarf, with misclassification of 5 as powdery mildew and 2 as stripe rust. 120 out of 136 diseased images of wheat stripe rust were classified correctly. Misclassifications included 9 as powdery mildew, 2 as yellow dwarf, and 5 as scab. 111 out of 120 instances of wheat scab disease were accurately predicted.

These results demonstrate that the MDDM-RF model achieves high accuracy across all four disease categories, with minimal confusion among similar disease symptoms. The highest classification accuracy is observed for Wheat Powdery Mildew and Wheat Yellow Dwarf, indicating the robustness of the learned features and the effectiveness of the fine-tuned RF classifier. Overall, the generalization performance of our model in multiclass disease classification of wheat crops is shown in Figure 7(b).

Performance of integrated support vector machine

To assess the effectiveness of the proposed MDDM-WD using an SVM classifier (MDDM-SVM), which integrates a VGG-16 base model with an SVM classifier, both a confusion matrix and class-wise performance metrics were evaluated on the multiclass wheat disease classification task (see Fig. 8). The confusion matrix in Fig. 8(a) provides a detailed view of the predictions across all four wheat disease categories: wheat powdery mildew, wheat yellow dwarf, wheat stripe rust, and wheat scab. Our model demonstrated high classification performance, such as 145 out of 151 correctly classified images of wheat powdery mildew, 124 out of 129 correctly classified images of yellow dwarf, 129 out of 136 correctly classified images of stripe rust, and 115 out of 120 correctly classified images of wheat scab (fusarium head blight). The model achieved an overall classification accuracy of approximately 97%. Most misclassifications were minor, primarily involving diseases with overlapping visual symptoms, which is typical in real-world agricultural disease datasets. Figure 8(b) provides a detailed comparison of Precision, Recall, and F1-Score for each disease class. The capability of MDDM-SVM to achieve a balanced trade-off between sensitivity and specificity is validated by these metrics.

Performance of integrated decision tree

The variant MDDM-DT of our model was obtained by integrating a fine-tuned VGG-16 base model with a decision tree (DT) classifier. The performance of MDDM-DT was evaluated using the confusion matrix presented in Figure 9(a). The MDDM-DT model demonstrated high classification performance. It classified 121 images of wheat powdery mildew, 121 images of yellow dwarf, 112 images of stripe rust, and 90 images of wheat scab, correctly into their respective classes. The confusion matrix revealed that the DT classifier performed moderately well. It achieved high accuracy in distinguishing Wheat Yellow Dwarf. Although a noticeable decline in precision for Wheat Scab and Wheat Powdery Mildew is experienced due to higher misclassification rates. Specifically, Wheat Stripe Rust was often confused with Wheat Powdery Mildew and Wheat Scab. This is most probably due to visual similarities in symptoms such as leaf discoloration and spotting. A detailed comparison of Precision, Recall, and F1-Score for each disease class is shown in Figure 9(b) to further validate the performance of the MDDM-DT model. This performance suggested that while Decision Trees offer interpretability and low computational complexity, their sensitivity to class overlap and data noise may reduce their effectiveness for fine-grained disease classification in WMDD.

Performance of integrated Bernoulli Naïve Bayes

To evaluate the performance of our fine-tuned MDDM-WD by using a Bernoulli Naïve Bayes classifier (MDDM-BNB) for multi-class classification of wheat diseases, the confusion matrix in Figure 10(a) was used to analyze and interpret its behavior. Results demonstrated that wheat powdery mildew in 111 instances, with minor misclassifications to other categories, wheat yellow dwarf in 107 instances, with 12 instances misclassified as powdery mildew, and a small number spread across other classes. wheat stripe rust in 88 cases, but showed higher misclassification rates, especially 22 instances mistaken for powdery mildew. wheat scab with 83 correct predictions and some confusion with stripe rust. These results indicate relatively high classification confidence. Though the confusion between visually similar diseases, such as stripe rust and scab, indicates potential areas for improvement. The performance chart in Figure 10(b) presents class-wise Precision, Recall, and F1-Score values. It offers a detailed breakdown of how well the BNB classifier performed on each disease type. Wheat stripe rust and wheat yellow dwarf lag slightly. F1-scores below 0.70 highlight the susceptibility to confusion of both during classification. The robustness of the Naïve Bayes approach is shown by its consistent performance. However, the relatively lower performance for wheat stripe rust suggested enhancing feature representation. Additional training data may be used for better differentiation. These findings indicated that the BNB model offers a lightweight and interpretable solution. Incorporation of more sophisticated models may further boost performance.

Performance of integrated eXtreme gradient boosting

To further enhance the classification performance of our MDDM-WD, we integrated an XGBOOST classifier and fine-tuned it on the WMDD. The effectiveness of the variant MDDM-XGB across wheat disease categories was evaluated using a confusion matrix, as illustrated in Fig. 11(a). The XGBoost classifier classification rate across all categories, such as 143 instances of wheat powdery mildew, was correctly predicted with only 8 misclassifications in total, such as 3 to yellow dwarf, 4 to stripe rust, and 1 to scab. Wheat scab had 123 correct classifications, with minor confusion, particularly toward powdery mildew, i.e., 5 instances. Wheat stripe rust achieved 125 accurate predictions. Wheat yellow dwarf was correctly classified in 110 cases, with a total of only 10 misclassifications distributed among other classes. The matrix highlights the strength of XGBoost in handling class imbalances and subtle inter-class variations more effectively than simpler probabilistic models. Classification Metric Comparison (CMC) is shown by using a performance chart in Fig. 11(b), which further confirms that each class consistently maintained high values across all key performance metrics.

Performance comparison of MDDM-WD

We compared the overall performance of our multi-disease detection model for wheat crop (MDDM-WD) by measuring precision, recall, F1-score, and accuracy. The performance of all ML classifiers improved notably after fine-tuning (see Fig. 12). SVM achieved the highest accuracy (0.97), precision (0.96), and recall (0.9575), while RF and XGBoost showed moderate gains. DT and NB performed lower due to their sensitivity to complex, high-dimensional features. These differences arise from the algorithms’ characteristics: SVM efficiently handles multi-class separations, ensemble methods like RF and XGBoost improve generalization, whereas DT and NB are prone to underfitting or overfitting. Overall, fine-tuning significantly enhanced classifier performance across most models. We have also performed a performance comparison of our proposed MDDM-WD using SVM, as it outperformed all other combinations of ML classifiers, with the state-of-the-art VGG-16 model using a transfer learning approach for wheat disease classification on our WMDD dataset. Table 8 shows the comparative results of our proposed MDDM-WD with the state-of-the-art VGG-16 DL architecture. Figure 13 illustrates the graphical comparison between our proposed MDDM-WD and the state-of-the-art VGG-16 deep learning model, while Table 9 presents the performance comparison of our model against several existing studies.

An ablation study was conducted to further assess the impact of fine-tuning and PCA using SVM classifiers. Fine-tuned MDDM-WD consistently improved accuracy, with variant MDDM-SVM achieving the highest (97%), while PCA slightly reduced accuracy but enhanced inference speed. The results in Table 10 indicate the performance comparison of fine-tuning, PCA, and optimized classifier selection for robust crop disease classification.

To further assess the generalization capability of the proposed MDDM-WD model, an additional evaluation was conducted on the publicly available Wheat Plant Diseases Dataset (WPDD)68, which consists of high-resolution, multi-leaf, in-field images of 12 disease classes of wheat crop. The competitive performance shown in Table 11 demonstrates the robustness of our MDDM-WD model to variation in disease types and imaging conditions. Minor accuracy drops on the WPDD public dataset indicate domain shifts but still confirm the adaptability of the fine-tuned MDDM-WD. The corresponding training and testing accuracy curve (Fig. 14) reveals effective feature learning and minimal overfitting. These results validate the scalability and reliability of MDDM-WD for real-field wheat disease detection.

The output of predicted disease classes received from our MDDM-WD is shown in Fig. 15, which shows our MDDM-WD detected wheat disease classes with better precision and accuracy.

Discussions

Most of the existing wheat disease detection approaches have primarily focused on rust diseases using predefined deep learning (DL) or machine learning (ML) models. They often relied on custom datasets captured under controlled conditions. Usually, these datasets are not available publicly and are limited to binary classification tasks. In contrast, the proposed MDDM-WD presents a novel, scalable, and practical solution for real-time multi-disease detection of wheat. Our model used in-field UAV imagery characterized by complex backgrounds and multi-leaf structures. We introduced an innovative hybrid framework by integrating DL and ML models. A pre-trained DL model, i.e., VGG-16, was used for extracting robust and generic features of images via transfer learning. Multiple ML classifiers, such as RF, SVM, DT, BNB, and XGBoost, were used on these features for disease classification. It enabled the MDDM-WD to detect multiple wheat disease classes with improved accuracy and generalization.

The key strength of our methodology is its real-time applicability. Two publicly available wheat disease datasets were merged to curate our WMDD dataset. We ensured diversity in environmental conditions and background complexities. The robustness and suitability of our model were strengthened for real-time agricultural settings. The integration of the DL model and ML algorithm has improved performance. Reliance on manual disease identification and expert consultation has also been reduced. A reliable, AI-driven tool for early disease detection not only empowers field operators but also minimizes crop losses. The adaptability of our designed system allows for other types of wheat diseases and cereal crops such as rice, maize, and barley. Key contributions of our presented study are:

AI-Powered support

The model offers an accurate, efficient, and reliable solution for multi-disease detection in wheat. It aids farmers and stakeholders with timely and automated disease diagnostics.

Robust composition of dataset

Curation of the dataset, having real-time, multi-leaf, UAV-based images with complex background details ensured real-world effectiveness of our system. Varying illumination and temporal conditions have further emphasized the reliability.

Feature engineering via transfer learning

The pre-trained VGG-16 model via the transfer learning approach has extracted features effectively. It uses its ImageNet knowledge base to extract high-quality, generic features from wheat disease imagery.

Hybrid DL–ML classification

A two-phase fine-tuned process was used for wheat disease detection. A fine-tuned DL model was used for high-level feature extraction in the first phase. Whereas ML classifiers were integrated with a DL feature extractor for disease prediction in the second phase. This combines the strengths of both paradigms for improved accuracy and robustness.

Real-Time, practical utility

The system supports early detection of wheat diseases and reduces the need for expert intervention. It mitigates the limitations posed by the short crop cycle and delayed symptom visibility.

Conclusion

Agriculture remains a cornerstone of the economy in developing countries. It contributes approximately 22.9–24% of the GDP in Pakistan. The growing global population and increasing food demand require crop yield optimization and disease management. Wheat plays a critical role in ensuring food security among cereal crops. However, it is highly susceptible to diseases that can reduce yields by up to 20%. Traditional disease monitoring methods are time-consuming, subjective, and ineffective for large-scale operations. This underscores the need for intelligent, automated solutions.

This research presented a deep learning-based Multi-Disease Detection Model for Wheat Diseases (MDDM-WD), to detect multiple wheat diseases. The dataset was curated from two publicly available sources having UAV imagery. This study focuses on four visually distinct and underexplored wheat disease classes, i.e. stripe rust, powdery mildew, scab (Fusarium head blight), and yellow dwarf. We employed a transfer learning approach using the VGG-16 model for feature extraction and integrated five supervised machine learning classifiers, such as Random Forest, SVM, Decision Tree, Bernoulli Naïve Bayes, and XGBoost, for disease classification.

Two-phase fine-tuning was performed to optimize both feature representation and classification performance. The integration of SVM with VGG-16 yielded the highest accuracy and efficiency in detecting wheat diseases. The proposed framework demonstrated the potential of combining DL and classical ML methods for robust, scalable, and accurate crop disease detection. It paves the way for smarter agricultural practices and improved food security.

Limitations

The proposed deep learning-based MDDM-WD demonstrated strong performance in the detection of multiple wheat diseases using UAV imagery. But some limitations must be acknowledged:

-

Feature Extraction: VGG-16 was selected for its simplicity and ease of implementation. However, more advanced architectures like ResNet or EfficientNet may yield improved performance. However, a comparative analysis was not conducted in this study.

-

Dataset Constraints: We curated WMDD from two public sources due to the limited availability of balanced, multi-leaf wheat disease datasets. The model may generalize to other wheat diseases. Lack of comprehensive open datasets limits their broader validation.

-

Computational Resources: Deep learning models require substantial computational power and storage. The processing of high-resolution UAV images can lead to delays or interruptions. It happens especially in resource-limited environments.

Future work

The proposed MDDM-WD model successfully performed multi-class classification of wheat diseases. It combined a pre-trained VGG-16 model for feature extraction with machine learning classifiers. However, several future directions exist to enhance its performance, applicability, and scalability:

-

Model Enhancement: Future versions of the model can incorporate more advanced deep learning architectures, such as ResNet, EfficientNet, or Inception, to improve classification accuracy. Additionally, alternative ML classifiers like K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) and fuzzy logic systems can also be explored.

-

Broader Crop and Disease Coverage: The flexibility of the model allows for expansion to include disease detection in other cereal crops. It can also be improved to cover additional wheat diseases beyond those addressed in the current study.

-

Image Type and Sensor Integration: Diverse image types such as hyperspectral imagery, thermal imaging, and chlorophyll fluorescence may be explored to enhance disease detection capabilities.

-

Data Acquisition Strategies: Improved data collection methodologies can be employed, including the use of UAVs, sensors, and multi-temporal imaging during various crop growth stages to capture more diverse and informative datasets.

-

Seed Disease Detection: The framework can be extended to detect seed-borne diseases by modifying preprocessing techniques.

-

Decision Support Module: The model can be augmented with modules to estimate disease severity. It may also recommend preventive or remedial measures. This will strengthen it as a comprehensive decision support system for farmers.

-

Evaluation Under Varying Altitude: In the future, the robustness of the proposed system may be evaluated under varying UAV altitudes. Such variations necessitate additional field-based UAV data acquisition. This will further assess the model’s generalizability and performance in diverse real-world scenarios.

Data availability

The two datasets analyzed during the current study are open-source and publicly available online in the repositories https://github.com/YcZhangSing/Dataset-of-DAE-Mask and https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/jawadali1045/20k-multi-class-crop-disease-images.

References

Aker, J. C. Dial A for agriculture: a review of information and communication technologies for agricultural extension in developing countries. Agric. Econ. 42, 631–647 (2011).

Ahmad, A. & Saraswat, D. El Gamal, A. A survey on using deep learning techniques for plant disease diagnosis and recommendations for development of appropriate tools. Smart Agric. Technol. 3, 100083 (2023).

Oerke, E. C. & Dehne, H. W. Safeguarding production—losses in major crops and the role of crop protection. Crop Prot. 23, 275–285 (2004).

Figueroa, M., Hammond-Kosack, K. E. & Solomon, P. S. A review of wheat diseases—a field perspective. Mol. Plant. Pathol. 19, 1523–1536 (2018).

Mumtaz, R. et al. Integrated digital image processing techniques and deep learning approaches for wheat Stripe rust disease detection and grading. Decis. Anal. J. 8, 100305 (2023).

DeChant, C. et al. Automated identification of Northern leaf blight-infected maize plants from field imagery using deep learning. Phytopathology 107, 1426–1432 (2017).

Neog, P. P. et al. A Brief Overview of Deep Learning based Techniques for the Detection of Wheat Leaf Disease: A Recent Study. Proc. 7th Int. Conf. Intell. Comput. Control Syst. (ICICCS) (2023).

Javaid, M., Haleem, A., Khan, I. H. & Suman, R. Understanding the potential applications of artificial intelligence in agriculture sector. Adv. Agrochem. 2, 15–30 (2023).

Liu, S. Y. Artificial intelligence (AI) in agriculture. IT Prof. 22, 14–15 (2020).

Panigrahi, K. P., Das, H., Sahoo, A. K. & Moharana, S. C. Maize leaf disease detection and classification using machine learning algorithms. Proc. ICCAN 2019, Prog. Comput. Anal. Netw. 33–42 (2020).

Anwar, H. et al. The NWRD dataset: an Open-Source annotated segmentation dataset of diseased wheat crop. Sensors 23, 6942 (2023).

Khan, H. et al. Automated wheat diseases classification framework using advanced machine learning technique. Agriculture 12, 1226 (2022).

Kumar, D. & Kukreja, V. Deep learning in wheat diseases classification: A systematic review. Multimed Tools Appl. 81, 10143–10187 (2022).

Abu, M. et al. Ahmad, M. I. A comprehensive performance analysis of transfer learning optimization in visual field defect classification. Diagnostics 12, 1258 (2022).

Chen, J., Chen, J., Zhang, D., Sun, Y. & Nanehkaran, Y. A. Using deep transfer learning for image-based plant disease identification. Comput. Electron. Agric. 173, 105393 (2020).

Nigam, S. et al. Deep transfer learning model for disease identification in wheat crop. Ecol. Inf. 75, 102068 (2023).

Nikith, B., Keerthan, N., Praneeth, M. & Amrita, T. Leaf disease detection and classification. Procedia Comput. Sci. 218, 291–300 (2023).

Dhingra, G., Kumar, V. & Joshi, H. D. Study of digital image processing techniques for leaf disease detection and classification. Multimed Tools Appl. 77, 19951–20000 (2018).

Nanehkaran, Y., Zhang, D., Chen, J., Tian, Y. & Al-Nabhan, N. Recognition of plant leaf diseases based on computer vision. J. Ambient Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 1–18 (2020).

Oo, Y. M. & Htun, N. C. Plant leaf disease detection and classification using image processing. Int. J. Res. Eng. 5, 516–523 (2018).

Sethy, P. K., Negi, B. & Bhoi, N. Detection of healthy and defected diseased leaf of rice crop using K-means clustering technique. Int. J. Comput. Appl. 157, 24–27 (2017).

Tian, K., Li, J., Zeng, J., Evans, A. & Zhang, L. Segmentation of tomato leaf images based on adaptive clustering number of K-means algorithm. Comput. Electron. Agric. 165, 104962 (2019).

Dayang, P. & Meli, A. S. K. Evaluation of image segmentation algorithms for plant disease detection. Int. J. Image Graph Signal. Process. 13, 14 (2021).

Harakannanavar, S. S., Rudagi, J. M., Puranikmath, V. I., Siddiqua, A. & Pramodhini, R. Plant leaf disease detection using computer vision and machine learning algorithms. Glob. Transitions Proc. 3, 305–310 (2022).

Javidan, S. M., Banakar, A., Vakilian, K. A. & Ampatzidis, Y. Diagnosis of grape leaf diseases using automatic K-means clustering and machine learning. Smart Agric. Technol. 3, 100081 (2023).

Griffel, L. M., Delparte, D., Whitworth, J., Bodily, P. & Hartley, D. Evaluation of artificial neural network performance for classification of potato plants infected with potato virus Y using spectral data on multiple varieties and genotypes. Smart Agric. Technol. 3, 100101 (2023).

Rangarajan, A. K., Purushothaman, R., Prabhakar, M. & Szczepański, C. Crop identification and disease classification using traditional machine learning and deep learning approaches. J. Eng. Res. 11, 1B (2023).

Panigrahi, K. P., Das, H., Sahoo, A. K. & Moharana, S. C. Maize leaf disease detection and classification using machine learning algorithms. In Prog. Comput. Anal. Netw.: Proc. ICCAN 2019 (2020).

Ahmed, K., Shahidi, T. R., Alam, S. M. I. & Momen, S. Rice leaf disease detection using machine learning techniques. In Proc. 2019 Int. Conf. Sustain. Technol. Ind. 4.0 (STI) (2019).

Xian, T. S. & Ngadiran, R. Plant diseases classification using machine learning. In J. Phys.: Conf. Ser. 1962 012024 (2021).

Chang, S. et al. Recognition of wheat rusts in a field environment based on improved densenet. Biosyst Eng. 238, 10–21 (2024).